ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Surgeon Volume is Predictive of 5-Year Survival in Patients

with Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Resection:

A Population-Based Study

Herng-Ching Lin&Chia-Chin Lin

Received: 23 June 2009 / Accepted: 10 August 2009 / Published online: 3 September 2009 # 2009 The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Abstract

Background and Aim No study has examined associations between physician volume or hospital volume and survival in patients with liver malignancies in the hepatitis B virus-endemic areas such as Taiwan. This study was to examine the effect of hospital and surgeon volume on 5-year survival and to determine whether hospital or surgeon volume is the stronger predictor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection in Taiwan.

Methods Using the 1997–1999 Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database and the 1997–2004 Cause of Death Data File, we identified 2,799 patients who underwent hepatic resection and 1,836 deaths during the 5-year follow-up period. The Cox proportional hazard regressions were performed to adjust for patient demographics, comorbidity, physician, and hospital characteristics when assessing the association of hospital and surgeon volume with 5-year survival.

Results When we examined the effect of physician and hospital volumes separately, both physician and hospital volumes significantly predicted 5-year survival after adjusting for characteristics of patient, surgeon, and hospital. However, after we adjusted for characteristics of physician and hospital, only physician volume remained a significant predictor of the 5-year survival.

Conclusions Physician volume is a stronger predictor of 5-year survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving hepatic resection.

Keywords Hepatocellular carcinoma . Survival . Hospital volume . Physician volume . Taiwan

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common cancer in Taiwan in terms of both incidence and mortality. HCC has been the second leading cause of cancer death in

Taiwan.1The high-risk group for HCC in Taiwan includes

patients chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) and liver cirrhosis or a family history of HCC, HBV, or HCV chronic infections, which

are the two major etiologies for HCC in Taiwan.2The last

three decades has seen remarkable advances in hepatic

surgery.3 Hepatic surgeries are now a safe and effective

therapy and one of the curative therapies for liver cancer.4,5

One of the most important issues of surgical oncology is to identify prognostic factors that influence the length of survival for cancer patients. Associations between hospital or physician volume and patient outcomes have been established for many surgical and other invasive proce-dures, with lower mortality among patients treated at hospitals or by physicians with higher procedural

vol-umes.6–8 Improved overall long-term survival in patients

with HCC has resulted in an increased number of liver resection being performed with an increasingly aggressive

surgical approach.9 However, no study has examined

H.-C. Lin

School of Health Care Administration, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

C.-C. Lin (*)

School of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei Medical University-Wan Fang Hospital, 250 Wu-Hsing Street,

Taipei 110, Taiwan e-mail: clin@tmu.edu.tw

associations between physician volume or hospital volume and survival in patients with liver malignancies in the HBV-endemic areas such as Taiwan. Most of the hepatic resections for malignancies are performed on an elective, rather than emergent, basis. If centers with superior patient outcomes could be identified, these procedures could be regionalized as a means of providing the most efficacious

and cost-effective care.10 Identification of factors

contrib-uting to better survival will help clinicians or policy makers to develop effective strategies to improve the quality care of HCC and survival.

A rapid rise in mortality from HCC has been observed in Taiwan since 1991 in patients aged greater than 20 years. Important efforts have been made to improve the survival rates of patients with HCC. However, despite scientific advances and the implementation of measures for early HCC detection in patients at risk, patient survival has not

improved during the last three decades.11 The 5-year

survival for asymptomatic small HCC is approximately

50% after surgical resection.12 To determine whether

surgeon and hospital volumes are independent predictors of 5-year survival after resection of HCC, we examined the association of both volume elements with 5-year survival in a national sample in Taiwan. We also investigated whether physician or hospital volume was more strongly associated with 5-year survival.

Materials and Methods Database

Two databases were used in this study. First, the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), published by the Taiwan National Health Research Institute, was used to obtain hospitalization data. The NHIRD is possibly one of the largest and most comprehensive databases; it covers 96% of the Taiwanese population of some 23 million. The NHIRD included medical claims for inpatient expenditures by admissions, details of inpatient orders, and registry for contracted medical facilities, board-certified specialists, medical personnel, and beneficiaries. One principal diagnosis

and procedure based on the ‘International Classification

of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)’ code and up to four secondary diagnoses and procedures using ICD-9-CM codes are listed for each patient.

Second, the mortality date was obtained from the

Cause of Death Data File published by Taiwan’s

Department of Health (DOH) covering the years 1997– 2004. The Cause of Death file provides data on marital status, the date of birth and death, place of legal

residence, underlying cause of death (ICD-9-CM code), and employment status. The data are believed to be very accurate and complete because of mandatory registration of all births and deaths in Taiwan. The NHIRD was linked to the Cause of Death Data File with the assistance of Taiwan’s DOH.

Study Subjects

All hospitalized patients from the NHIRD covering the period 1997–1999 by a principal diagnosis of malignant neoplasm of liver and intrahepatic bile ducts (ICD-9-CM codes 155.XX) were selected as our study sample (n= 34,158). We limited the cases to those who underwent a liver lobectomy (ICD-9-CM procedure code 50.3) or partial hepatectomy (ICD-9-CM procedure code 50.22), and 3,159 cases were left. In addition, those patients who were also diagnosed with secondary and unspecified malignant

neoplasm (ICD-9-CM codes 196.XX–199.XX), malignant

neoplasm of intrahepatic bile ducts (ICD-9-CM code 155.1), or malignant neoplasm of liver, not specified as primary or secondary (ICD-9-CM code 155.2), were all excluded from the study sample. Ultimately, we were left with a sample of 2,799 eligible subjects with primary liver malignancy and underwent hepatectomies during the period of the study.

Five-year follow-up were subsequently undertaken in order to determine whether any of the sampled patients were dead within a 5-year period after hepatic resections. All cause mortality was used except those who died of

accidents (ICD-9-CM codes E800–E869, E880–E928, and

E950–E999). In total, 1,836 deaths were identified, regard-less of time of occurrence, during the 5-year follow-up period.

Surgeon and Hospital Hepatectomy Volume Groups Since unique physician and hospital identifiers are available within the NHIRD for each medical claim submitted, this enabled us to identify the same physician, or the same hospital, carrying out one or more hepatectomies during our 3-year study period. Surgeons and hospitals were sorted, in ascending order of their total volume of liver cancer resections, with the cutoff points (high, medium, and low) being determined by the volume that most closely sorted the sample patients into three groups, which were roughly equivalent in size. The sample of 2,799 patients was

divided into three surgeon volume groups: ≤19 cases

(hereafter referred to as low volume), 20–95 cases

(medium volume), and ≥96 cases (high volume), while

the three hospital volume groups were ≤87 cases (low

volume), 88–298 cases (medium volume), and ≥299 cases (high volume).

Key Variables of Interest

The key dependent variable of interest was“5-year survival,”

with“patient” as the unit of analysis, and the key independent

variables were the “hepatectomy volume groups” for both

surgeons and hospitals.

The characteristics of surgeon, hospital, and patient were taken into account in our study. Surgeon characteristics included the surgeon’s age (as a surrogate for practice experience) and gender; hospital characteristics included hospital ownership, hospital level, teaching status, and geographical location, with the hospital ownership variable

being recorded as one of three types,“public,” “private

not-for-profit” and “private not-for-profit” hospitals. Within the hospital level variable, each hospital was classified as a medical center (with a minimum of 500 beds), a regional hospital (minimum 250 beds), or a district hospital (minimum 20 beds); hospital level can therefore be used as a proxy for both hospital size and clinical service capabilities.

Patient characteristics comprised of age, gender, sever-ity of illness, and type of operation. Age was not linearly associated with survival and was categorized into four groups (<50, 50–64, 65–74, and >74). Since no illness severity index is currently available in Taiwan, we used a modified Charlson’s index, the Deyo–Charlson index, to adjust for the patients’ clinical comorbidities; the Deyo– Charlson index has been used as a means of adjusting for the higher mortality risks associated with comorbidities and has been widely used since then for risk adjustment in administrative claims datasets. Higher scores on Charlson’s index indicate more illness severity. The “type of operation” comprised of partial hepatectomy and liver lobectomy.

Statistical Analysis

The SAS statistical package (SAS System for Windows, Version 8.2) was used to perform the statistical analysis of the data in this study. The distribution of characteristics of surgeon, hospital, and patient according to surgeon and

hospital hepatectomy volume groups were examined byχ2

or ANOVA test. Five-year cumulative survival estimates and survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan– Meier method and compared by means of the log-rank test by surgeon and hospital volume. Survival time was computed from the date of hepatectomy to the date of death within the 5-year follow-up period. In order to account for possible clustering effects within each surgeon or hospital panel, we used stratified Cox regression models to evaluate the contributions of surgeon and hospital volume to 5-year survival while adjusting for the character-istics of surgeon, hospital, and patient. Hazard ratios and

95% confidence intervals are presented. A two-sided p value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 describes the distribution of the characteristics of

surgeons and patients by surgeon hepatectomy volume group. Hepatectomies were performed by 286 surgeons between January 1997 and December 1999, at a mean volume per surgeon of 9.8 operations. Of the total of 2,799 patients, 996 (35.6%) had undergone liver lobectomy, and the other 1,803 (64.4%) had partial hepatectomy. The surgeons in the high-volume group were more likely to be older (p<0.001). Patients in the low-volume group, on average, had higher Charlson Comorbidity Index Score than their counterparts in other groups (p<0.001).

Table 2 presents the characteristics of hospital and

patients, classified by three hospital hepatectomy volume group. Hepatectomies were carried out by 90 hospitals between 1997 and 1999, at a mean volume of 31.2 resections per hospital. The vast majority of the hospitals (92.2%) fell into the low-volume group; these hospitals were generally located in the northern part of Taiwan. All hospitals in the medium- and high-volume groups are medical centers and teaching hospitals. Patients treated by surgeons in low-volume group were more likely to undergo liver lobectomies (p<0.001).

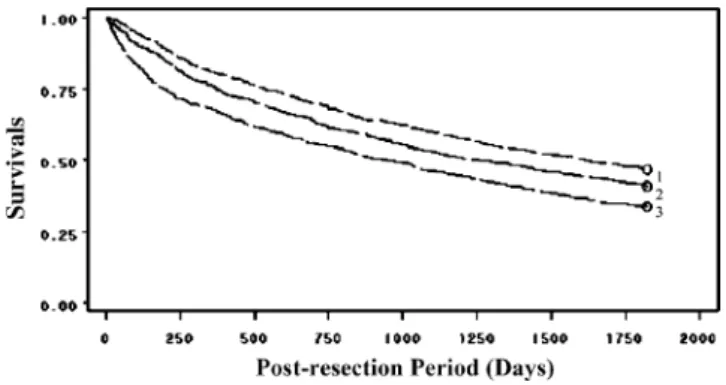

Figures1and2illustrate the unadjusted 5-year survival

of patients by surgeon and hospital volume. The log-rank tests show that patients treated by high-volume surgeons or hospitals had significantly greater 5-year survival (both p<0.001).

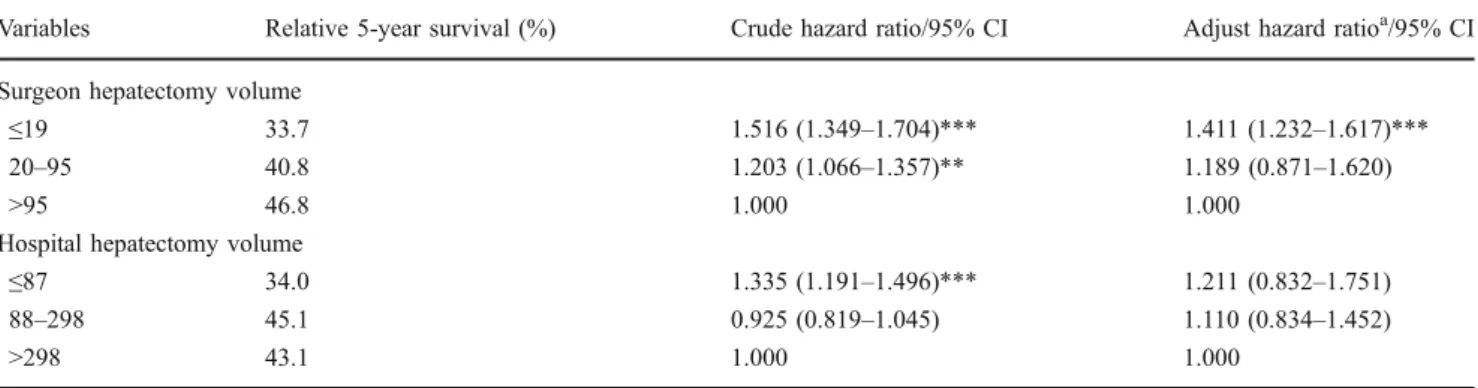

Table 3 provides the 5-year survival rate, crude hazard

ratios and adjusted hazard ratios by hospital and surgeon volume group. Five-year survival rate increased with increasing surgeon volume group; it was 33.7%, 40.8%, and 46.8% for sampled patients in low-, medium-, and high-volume groups, respectively, while the 5-year survival rate was 34.0%, 45.1%, and 43.1% for sampled patients in low-, medium-, and high-volume hospital groups, respec-tively. Cox proportional hazard regressions show that patients treated by low-volume surgeons had a 51.6% higher risk of death than those treated by high-volume surgeons (p<0.001). Similarly, the risk of death for patients receiving resections in low-volume hospitals was 1.335 times as high as the risk of their counterparts in high-volume hospitals (p<0.001).

After adjusting for characteristics of patient, surgeon, and hospital and clustering effects of surgeon or hospital, the relationships between 5-year survival and surgeon volume group remains; the stratified Cox regression models

show that adjusted risk of death for patients operated by low-volume surgeons was 41.1% higher than those by high-volume surgeons (p<0.001). However, hospital case vol-ume alone is not a significant predictor of 5-year survival for hepatectomies.

Discussion

The volume–outcome relationship has been rarely explored in liver cancer. Although few studies have examined the relationship between volume and outcomes of hepatic resection for HCC in the USA, these studies examined only in-hospital mortality and examined effects of hospital volume only. These studies did not examine effects of

hospital and physician volume simultaneously.10,13,14 This

is the first study using population-based data to investigate whether physician or hospital volume was more strongly associated with long-term survival of hepatic resection for HCC.

A number of studies have correlated perioperative outcome to hospital volume or physician volume for some certain types of surgical procedures, including cardiac,

vascular, and general surgeries.15–18 These volume

–out-come relationships serve as the basis for the argument that high-risk procedures should be regionalized to centers of

excellence.10,19–21 However, it is relatively unknown

whether long-term survival after hepatic resections may be altered by such regionalization. These data in this current study further support regionalization of high-risk Table 1 Surgeon and Patient Characteristics in Taiwan, by Surgeon Liver Cancer Resection Volume Groups, 1997–1999

Variable Surgeon liver cancer resection volume groups p value

Low (1–19) Medium (20–95) High (>95)

Number Percent Mean SD Number Percent Mean SD Number Percent Mean SD Surgeon characteristics (n=286)

Total number of surgeons 263 18 5

Liver cancer resection volume 3.5 3.8 49.3 23.5 247.0 132.5 –

Age 40.8 7.6 42.7 7.0 43.6 4.1 – Gender Male 258 98.1 18 100.0 5 100.0 0.805 Female 5 1.9 – – – – Physician age <40 141 53.6 8 44.4 1 20.0 0.3424 41–50 96 36.5 8 44.4 4 80.0 >51 26 9.9 2 11.2 – – Patient characteristics (n=2,799)

Total number of patients 910 887 1,002

Patient age <50 249 27.4 255 28.8 305 30.4 0.0066 50–64 304 33.4 316 35.6 369 36.8 65–74 264 29.0 263 29.7 259 25.9 >74 93 10.2 53 6.0 69 6.9 Patient gender Male 681 74.8 695 78.3 817 81.5 0.0018 Female 229 25.2 192 21.7 185 18.5

Charlson Comorbidity Index score

3 457 50.2 434 48.9 58 54.7 <0.001 4 279 30.7 336 37.9 360 35.9 5 or more 174 19.1 117 13.2 94 9.4 Surgery type Lobectomy 363 39.9 291 32.8 342 34.1 0.0036 Partial hepatectomy 547 60.1 596 67.2 660 65.9

T able 2 Hospital and Patient Characteristics in T aiwan, by Hospital Liver Cancer Operation V olume Groups, 1997 –1999 V ariable Hospital Liver Cancer Resection V olume Groups p value Low (1 –87) Medium (88 –298) High (>298) Number Percent Mean SD Number Percent Mean SD Number Percent Mean SD Hospital characteristics (n = 90) T otal number of hospitals 83 5 2 Liver cancer operation volume 1 1.4 18.3 173.8 75.7 495.5 1 1 1.0 Hospital level Medical center 7 8.4 5 100.0 2 100.0 <0.001 Regional hospital 46 55.4 –– – – District hospital 30 36.1 –– – – Hospital ownership Public 23 27.7 4 80.0 1 50.0 0.1336 Private (not-for -profit) 36 43.4 1 20.0 1 50.0 Private (for -profit) 24 28.9 –– – – Hospital location Northern 34 41.0 1 20.0 2 100.0 0.5404 Central 21 25.3 1 20.0 –– Southern 25 30.1 3 60.0 –– Eastern 3 3.6 –– – – T eaching status Y es 7 5 90.4 5 100 2 100.0 0.69096 No 8 9.6 –– – – Patient characteristics (n = 2,799) T otal number of patients 939 869 991 Age <50 264 28.1 240 27.6 305 30.8 0.0013 50 –64 335 35.7 276 31.8 378 38.1 65 –74 261 27.8 273 31.4 252 25.4 >74 79 8.4 80 9.2 56 5.7 Gender Male 722 76.9 707 81.4 764 77.1 0.0345 Female 217 23.1 162 18.6 227 22.9 Charlson Comorbidity Index score 3 426 45.4 487 56.1 526 53.1 <0.001 4 341 36.3 268 30.8 366 36.9 5 o r more 172 18.3 1 1 4 13.1 99 10.0

procedures, such as hepatectomy for HCC, in Taiwan. In the current study, we confirmed a relationship of long-term survival with hospital volume for liver resections using a large national database in Taiwan. If centers with superior patient outcomes, i.e., long-term survival, could be identified, the procedure of resection of HCC could be regionalized as a means of providing the most cost-effective care with optimal quality.

In this study, when we examined the effect of physician volume and hospital volume separately, both physician volume and hospital volume significantly associated with 5-year survival. However, after we adjusted for characteristics of physician and hospital, only physician volume remained a significant predictor to the 5-year survival. In those very few studies, which sought to identify the simultaneous contribution of hospital and physician volume to outcomes, they have generated similar results, i.e., physician volume is more significant than hospital volume on the relationship

between volume and mortality. Halm et al.22 conducted

Figure 2 Liver cancer resection survival rates for patients hospital-ized in Taiwan, by hospital volume, 1997–1999.Asterisk Hospital volume was defined as the number of liver cancer surgeries between the years 1997 and 1999 as follows: 1 high, 2 medium, and 3 low. Figure 1 Liver cancer resection survival rates for patients hospital-ized in Taiwan, by surgeon volume, 1997–1999. Asterisk Surgeon volume was defined as the number of liver cancer surgeries between the years 1997 and 1999 as follows: 1 high, 2 medium, and 3 low.

T able 2 (continued) V ariable Hospital Liver Cancer Resection V olume Groups p value Low (1 –87) Medium (88 –298) High (>298) Number Percent Mean SD Number Percent Mean SD Number Percent Mean SD Sur gery type Lobectomy 413 44.0 288 33.1 295 29.8 <0.001 Partial hepatectomy 526 56.0 581 66.9 696 70.2

a systematic review on volume–outcome relationship in health care and concluded that the surgeon seemed to be a more important determinant of outcomes than hospital volume in the case of coronary artery bypass surgeries, carotid endartectomy, surgery for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, and surgery for colorectal cancer.

Similarly, Hu et al.23 found that hospital volume is not

significantly associated with outcomes after adjusting for physician volume in male patients who underwent radical

prostatectomy. Moreover, Hannan et al.24 found that

physician volume is more significant than hospital volume on the relationship between volume and mortality for coronary artery bypass surgeries, resection of abdominal aortic aneurysms, partial gastrectomies, and colectomies. Therefore, it appears that physician volume could be the mechanism that underlines the relationship between hospital volume and survival rates. More research efforts are needed to continue to clarify the impact of both hospital and surgeon volume on mortality rates simulta-neously as well as the impact of the interaction of these two volume measures on mortality rates.

As documented in the literature, our results support the notion that high volume is often associated with better outcomes. Two major hypotheses have been

proposed to explain these relationships.22,25–28 First,

“practice makes perfect,” i.e., physicians and hospitals develop more effective skills if they treat more patients.

Second is “selective referral”, i.e., physicians and

hospitals achieving better outcomes receive more refer-rals and thus accrue larger volumes. However, the relative contribution of physician versus hospital volume still remains unknown because there have been very few studies that examined both types of volume measures

simultaneously.22

Although a compelling volume–outcome relationship was supported in our study, several limitations existed in this study. First, this study was adjusted for patient co-morbidities; nevertheless, the National Database lacked data on the severity of HCC, e.g., on MELD or Child scores, to account for differences in the severity of HCC among patients. Moreover, other variables that possibly affect patients’ long-term survival rates were not comprehensively collected in the data-base, and therefore, we were not able to incorporate these possible confounding variables in the analyses. Lastly, this study used a cross-sectional design. We were not able to reveal the consequential relationship between volume and outcomes. Further longitudinal studies may be needed to explore whether hospitals or physicians with better outcomes would consequently acquire greater volume of patients.

In conclusion, this is the first population-based study examining associations between both physician volume and hospital volume and long-term survival in patients with liver malignancies in the HBV-endemic areas, Taiwan. We have demonstrated that higher volumes are associated with better long-term survival rates. More-over, physician volume is more significant than hospital volume in predicting 5-year survival rates in HCC patients. If physicians or centers with superior patient outcomes could be identified, these procedures could be regionalized as a means of providing the most effica-cious and cost-effective care. Furthermore, it is impor-tant to find out why some providers have subsimpor-tantially better outcomes than others, and the government should make systematic efforts to transfer this capability to all providers in order to improve the care and treatment outcome for all HCC patients.

Table 3 Relative 5-Year Survival and Hazard Ratios by Surgeon and Hospital Liver Cancer Resection Volume Groups

Variables Relative 5-year survival (%) Crude hazard ratio/95% CI Adjust hazard ratioa/95% CI Surgeon hepatectomy volume

≤19 33.7 1.516 (1.349–1.704)*** 1.411 (1.232–1.617)***

20–95 40.8 1.203 (1.066–1.357)** 1.189 (0.871–1.620)

>95 46.8 1.000 1.000

Hospital hepatectomy volume

≤87 34.0 1.335 (1.191–1.496)*** 1.211 (0.832–1.751)

88–298 45.1 0.925 (0.819–1.045) 1.110 (0.834–1.452)

>298 43.1 1.000 1.000

Total sample No.=2,799 ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001

a

Odds ratios are adjusted for patient’s age, gender, type of operation, the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and surgeon’s age and gender and hospital characteristics including hospital ownership, hospital level, teaching status and geographical location and clustering effect of surgeon or hospital (by stratified Cox regression model)

References

1. Department of Health. Taiwan, ROC. Statistics of causes of death, Vol. I. http://www.doh.gov.tw/EN2006/DM/DM2_p01.aspx?class_ no=390&now_fod_list_no=9256&level_no=2&doc_no=51991. Accessed August 12, 2008.

2. Chen CJ, Yu MW, Liaw YF. Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997;12(9–10):S294–S308.

3. Fong Y, Gonen M, Rubin D, Radzyner M, Brennan MF. Long-term survival is superior after resection for cancer in high-volume centers. Ann Surg 2005;242(4):540–547.

4. Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Fortner JG, Brennan MF. Pancreatic or liver resection for malignancy is safe and effective for the elderly. Ann Surg 1995;222(4):426–437.

5. Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 1999;230(3):309–321.

6. Luft HS, Garnick DW, Mark DH, McPhee SJ. Hospital Volume, Physician Volume, and Patient Outcomes. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administrative Press, 1990.

7. Dudley RA, Johansen KL, Brand R, Rennie DJ, Milstein A. Selective referral to high-volume hospitals: estimating potentially avoidable deaths. JAMA 2000;283(9):1159–1166.

8. Gandjour A, Bannenberg A, Lauterbach KW. Threshold volumes associated with higher survival in health care: a systematic review. Med Care 2003;41(10):1129–1141.

9. Choti MA, Bowman HM, Pitt HA, Sosa JA, Sitzmann JV, Cameron JL, Gordon TA. Should hepatic resections be performed at high-volume referral centers? J Gastrointest Surg 1998;2(1):11–20. 10. Glasgow RE, Showstack JA, Katz PP, Corvera CU, Warren RS,

Mulvihill SJ. The relationship between hospital volume and outcomes of hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg 1999;134(1):30–35.

11. Blum HE. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2005;19(1):129–145.

12. Lee CS, Sheu JC, Wang M, Hsu HC. Long-term outcome after surgery for asymptomatic small hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 1996;83(3):330–333.

13. Dimick JB, Cowan JA, Knol JA, Upchurch GR. Hepatic resection in the United States: indications, outcomes, and hospital proce-dural volumes from a nationally representative database. Arch Surg 2003;138(2):185–191.

14. Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA, Lipsett PA. Postoperative complication rates after hepatic resection in Maryland hospitals. Arch Surg 2003;138(1):41–46.

15. Hannan EL, Kilburn H, Bernard H, O’Donnell JF, Lukacik G, Shields EP. Coronary artery bypass surgery: the relationship between inhospital mortality rate and surgical volume after

controlling for clinical risk factors. Med Care 1991;29(11):1094– 1107.

16. Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, Hur K, Hossain M, Soybel D, Kizer KW, Aust JB, Bell RH, Chong V, Demakis J, Fabri PJ, Gibbs JO, Grover F, Hammermeister K, McDonald G, Passaro E, Phillips L, Scamman F, Spencer J, Stremple JF. Relation of surgical volume to outcome in eight common operations: results from the VA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg 1999;230(3):414–432.

17. Steinberg EP, Tielsch JM, Schein OD, Javitt JC, Sharkey P, Cassard SD, Legro MW, Diener-West M, Bass EB, Damiano AM, et al. National study of cataract surgery outcomes. Variation in 4-month postoperative outcomes as reflected in multiple outcome measures. Ophthalmology 1994;101(6):1131– 1141.

18. Lavernia CJ. Hemiarthroplasty in hip fracture care: effects of surgical volume on short-term outcome. J Arthroplasty 1998;13 (7):774–778.

19. Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med 1979;301(25):1364–1369.

20. Gordon TA, Burleyson GP, Tielsch JM, Cameron JL. The effects of regionalization on cost and outcome for one general high-risk surgical procedure. Ann Surg 1995;221(1):43–49.

21. Wen HC, Tang CH, Lin HC, Tsai CS, Chen CS, Li CY. Association between surgeon and hospital volume in coronary artery bypass graft surgery outcomes: a population-based study. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81(3):835–842.

22. Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med 2002;137(6):511–520.

23. Hu JC, Gold KF, Pashos CL, Mehta SS, Litwin MS. Role of surgeon volume in radical prostatectomy outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2003;21(3):401–405.

24. Hannan EL, O’Donnell JF, Kilburn H, Bernard HR, Yazici A. Investigation of the relationship between volume and mortality for surgical procedures performed in New York State hospitals. JAMA 1989;262(4):503–510.

25. Luft HS. The relation between surgical volume and mortality: an exploration of causal factors and alternative models. Med Care 1980;18(9):940–959.

26. Luft HS, Hunt SS, Maerki SC. The volume–outcome relationship: practice-makes-perfect or selective-referral patterns? Health Serv Res 1987;22(2):157–182.

27. Flood AB, Scott WR, Ewy W. Does practice make perfect? Part I: the relation between hospital volume and outcomes for selected diagnostic categories. Med Care 1984;22(2):98– 114.

28. Flood AB, Scott WR, Ewy W. Does practice make perfect? Part II: the relation between volume and outcomes and other hospital characteristics. Med Care 1984;22(2):115–125.