Title: Beneficial impact of multidisciplinary team care management on the

survival in different stages of oral cavity cancer patients: results of a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan

Authors

Wen-Chen Tsai, DrPHa,*, Pei-Tseng Kung, ScDb,*, Shih-Ting Wang, MHA b,

Kuang-Hua Kuang-Huang, PhD b, Shih-An Liu, MD, PhD c,d Affiliation /Institute

a Department of Health Services Administration, China Medical University, Taichung,

Taiwan. b Department of Healthcare Administration, Asia University, Taichung,

Taiwan. c Department of Otolaryngology, Taichung Veterans General Hospital,

Taichung, Taiwan. d Faculty of Medicine, School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming

University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Corresponding author: Shih-An Liu.

Address: 1650, Taiwan Boulevard, Sect.4, Taichung 40705, Taiwan, R.O.C. Department of Otolaryngology, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Tel.: +886-4-23592525 ext 5401 Fax: +886-4-23596868

E-mail: saliu@vghtc.gov.tw

* These authors (W.C. Tsai, P.T. Kung) contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to

Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this study was to investigate the association between

multidisciplinary team (MDT) care management and survival of oral cavity cancer patients using a nationwide database in Taiwan.

Materials and Methods: A nationwide cohort study was conducted between 2005

and 2008. The follow-up end point was 2010. Claims data of oral cavity cancer patients were retrieved from the Taiwan Cancer Registry Database. Secondary data were obtained from the Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Among 19,766 newly diagnosed oral cavity cancer patients, we identified 16,991 patients who underwent treatment between 2004 and 2008 for further analyses.

Results: Overall survival was compared between patients who received MDT care

management (n=3324) and those who did not (n=13367). Hazard ratios (HR) of death in patients with MDT care managment were also analyzed. Patients with MDT care management had a lower risk of death when compared with that of patients without MDT care management (HR: 0.94, 95% Confidence intervals (CI): 0.89 to 1.00; P = 0.032). The effect of MDT care managment on survival was stronger for male patients than for female patients (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89 to 1.00; P = 0.040 versus HR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.75 to 1.27 P = 0.866). In addition, the effect of MDT care management

was strong among patients with a Charlson Comorbidity Index between 4 and 6, in those without coexisting catastrophic illness/injury, and in patients with stage IV diseases.

Conclusion: MDT care was associated with a better survival among patients with oral

cavity cancer. Survival rates in oral cavity cancer patients with MDT management appeared to be marginally better than those of patients without MDT management.

Keywords: Oral cavity cancer; Multidisciplinary team; Nationwide database;

Survival analysis; Propensity score; Beneficial impact

Highlights:

Many studies have suggested that multidisciplinary team (MDT) care reduced healthcare costs and improved the quality of life of cancer patients. But few studies have addressed the impact of MDT on the survival of oral

cavity cancer patients.

Survival rates in oral cavity cancer patients with MDT management appeared to be marginally better than those of patients without.

Abbreviations

MDT: multidisciplinary team; NHIRD: National Health Insurance Research Database; HR: Hazard ratios; CI: confidence interval; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; ICD-9: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; TCRD: Taiwan Cancer Registry Database; NTD: New Taiwan Dollars

Introduction

The incidence of oral cancer varies widely throughout the world. Oral cancer is reported to be the sixth most common cancer globally [1]. In developing countries, oral cancer is the third most common malignancy after cancer of the cervix and stomach [2]. In Taiwan, oral cancer has been among the top 10 causes of death from cancer since 1991. According to statistical data from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of the Executive Yuan, the annual death toll for oral cancer in males has increased rapidly in Taiwan [3]. Although better combinations of locoregional therapeutic modalities, such as surgical extirpation after neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus postoperative radiotherapy or target therapy plus radiotherapy, have improved patients’ quality of life after treatment, the overall 5-year survival has not improved much over the past few decades [4].

Multidisciplinary team (MDT) care improves upon conventional managements for oral cavity cancer by integrating surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, psychologists, dietitians, speech therapists, and nursing staff to improve the quality of life of cancer patients [5,6]. In a randomized controlled trial, structured multidisciplinary intervention helped sustain or even improve quality of life in advanced cancer patients receiving cancer therapy [7]. In Australia, multidisciplinary care reduced mortality and healthcare costs, and improved the quality of life in

women with early-stage breast cancer [8]. In a review article, the best approach was found to involve the application of a multidisciplinary diagnostic and treatment philosophy in which optimum treatment plans that alleviate or avoid adverse treatment effects could be assured [9]. The National Health Insurance Administration of Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan implemented “MDT care management for cancer patients” in April 2003 to improve the quality of cancer diagnosis and management [5]. In Taiwan, medical centers that do not have a MDT for cancer management are not able to receive accreditation. In terms of oral cavity cancer, a MDT must include a head and neck surgeon, radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, pathologist, and radiologist. Routine combined conference is also necessary to discuss the management of newly diagnosed oral cavity cancer patients. In addition, hospitals can receive additional imbursement from the National Health Insurance Administration with proper documentation of such patients who are managed via a MDT. To date, few studies have addressed the impact of MDT on the survival of oral cavity cancer patients. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the association between MDT and survival of oral cavity cancer patients included in a nationwide database in Taiwan. We also examined the various effects of MDT care management on patients with oral cavity cancer.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University (IRB number: CMUH102-REC3-076). In this nationwide retrospective longitudinal cohort study, we retrieved claims data of all patients diagnosed with oral cavity cancer from the Taiwan Cancer Registry Database, which is a subset of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). The NHIRD includes detailed health care information of more than 23 million enrollees, representing 99.6% of Taiwan’s entire population. The accuracy of diagnosis of major diseases in the NHIRD, such as ischemic stroke and acute coronary syndrome, has been validated in previous studies [10,11].

Selection of participants

We identified all patients diagnosed with oral cavity cancer from 2005 to 2008 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] codes: 140, 141, 143-146, 149) as the parent group. Monitoring was continued until 2010. The accuracy of diagnosis of oral cavity cancer was confirmed by both ICD-9 Codes and inclusion in the Taiwan Cancer Registry Database (TCRD) published by the Health Promotion Administration. Those who died within 1 month of confirmed diagnosis,

had histology other than squamous cell carcinoma, or did not receive any treatment (such as, surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy) were excluded.

Description of Variables

As hospitals can receive additional imbursement from the National Health Insurance Administration with proper documentation of patients managed via a MDT, we retrieved the abovementioned data from the NHIRD and defined this group as patients with MDT care management. Basic demographic data included gender and age at confirmation of diagnosis. Coexisting catastrophic illness/injury before diagnosis of oral cavity cancer was also documented. The number of services provided by primary hospitals was divided into high-volume and low-volume categories based on the median. Hospital ownership was separated into public and private. Tumor staging provided the “Taiwan Cancer Registry Long Form” was done in accordance to the guidelines of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (6th edition) [12]. The extent of comorbidity was classified using four levels according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) adapted by Deyo [13]. Propensity score was calculated using logistic regression as proposed by Rosenbaum and Rubin [14] to estimate the probabilities of selecting a patient to receive MDT care management given the background variables, including age, gender, coexisting catastrophic

illness/injury, level of hospital, tumor stage, CCI, and others. Then further analysis was conducted using estimated propensity scores as continuous adjustment variables in a logistic regression model [15].

Main Outcome Measurements

Follow-up duration was defined as the interval between the day of confirmed diagnosis of oral cavity cancer and the day of death or follow-up endpoint. Death was identified as withdrawal of the patient from the National Health Insurance program. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics for general data presentation. Comparisons of nominal or ordinal variables between patients with MDT care management and those without MDT care management were analyzed by chi-square test, whereas continuous variables were examined by Student’s t test. In addition, Kaplan-Meier survival curves of MDT participants/ non-participants were plotted based on tumor stage to investigate the influences of MDT care management on the survival of oral cavity cancer patients. Furthermore, a modified Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze the hazard ratio of death of patients receiving MDT care management after adjusting for age, sex, and other variables. All statistical analyses were performed

using SAS software, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and a P value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

We first identified 19,766 potentially eligible oral cavity cancer patients diagnosed for the first time and registered in the TCRD. There were 2,362 patients (11.9%) who died within 1 month of confirmed diagnosis or did not receive any kind of treatment during the follow-up period. In addition, 679 patients (3.4%) who had histology other than squamous cell carcinoma of oral cavity and 34 patients (0.2%) with incomplete data were also excluded from the final analysis. Therefore, a total of 16,991 patients were enrolled in the study. Secondary data were obtained from the NHIRD.

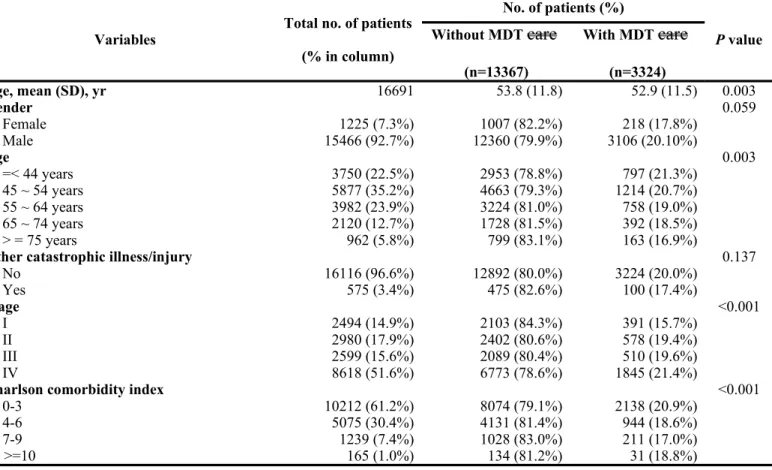

The average age at diagnosis was 53.6 + 11.8 years and males accounted for the majority of patients (n=15,466, 92.7%). The average follow-up period was 32.2 months (+ 19.6 months). There were 3,324 patients (19.9%) with MDT care management and 13,367 patients (80.1%) without MDT care management. Five hundred and seventy-five patients (3.4%) had coexisting catastrophic illness/injury other than oral cavity cancer and most of the studied population had CCI less than or equal to 3 (n=10,212, 61.2%) at the time of diagnosis. The majority of patients underwent treatment at a medical center (n=12,951, 77.6%) while most of the rest

were treated at a regional hospital (n=3,677, 22.0%). More than half of the studied population (51.6%, n=8,618) presented with stage IV disease, whereas 14.9% (n=2,494) had stage I, 17.9% (n=2,980) had stage II, and 15.6% (n=2,599) had stage III disease.

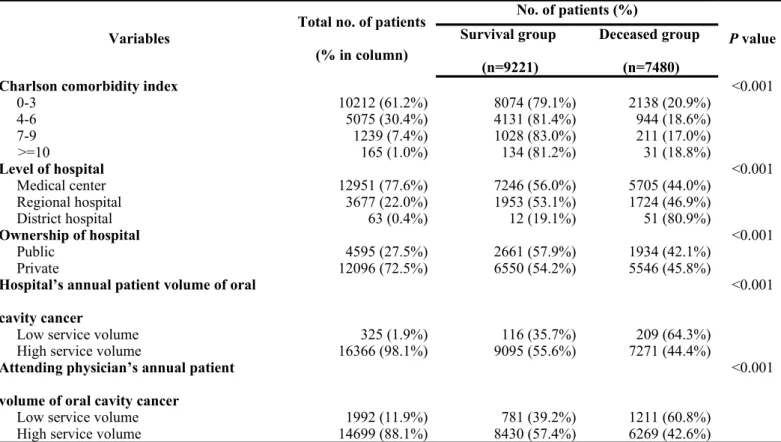

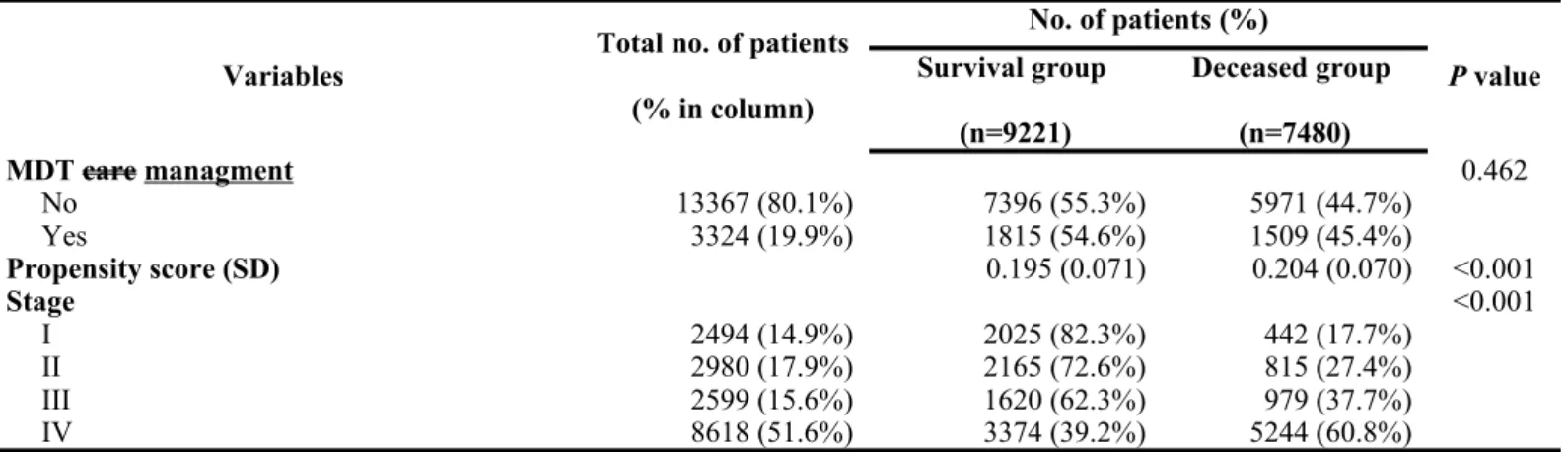

When stratifying the patients based on whether they did or did not receive MDT care management, there were no significant differences between the two groups in gender ratio, coexisting catastrophic illness/injury, and the treating hospital’s annual volume of oral cavity cancer patients. However, there was a higher proportion of younger patients receiving MDT care management when compared with that of older patients. In addition, there was a higher tendency for patients with a lower CCI score to be selected for MDT care management when compared with patients with a higher CCI score. There were also significant differences between the two groups in level of hospital, ownership of hospital, and tumor stage. Detailed data are presented in Table 1.

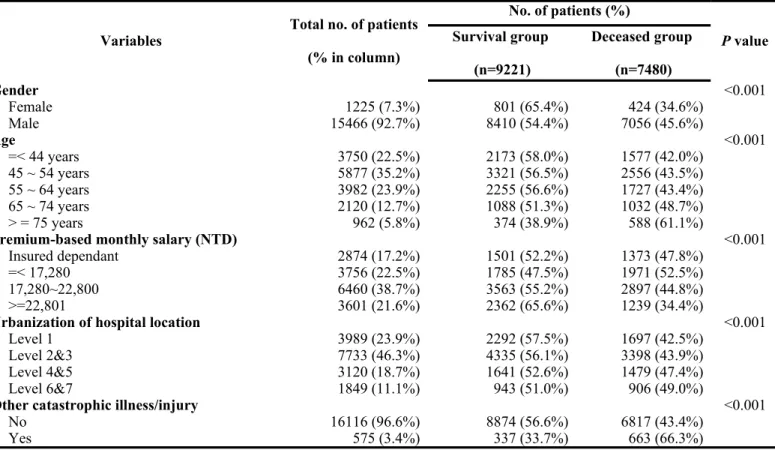

When stratifying patients according to the survival status, female patients tended to have a higher survival when compared with that of male patients. In addition, the survival status declined as the age increased. Patients with higher premium-based monthly salary had a higher survival rate. There were also significant differences between the two groups in the level of urbanization of hospital location, CCI,

coexisting catastrophic illness/injury, level of hospital, ownership of hospital, treating hospital’s annual volume of oral cavity cancer patients, attending physician’s annual volume of oral cavity cancer patients, and tumor stage. Detailed data are shown in Table 2.

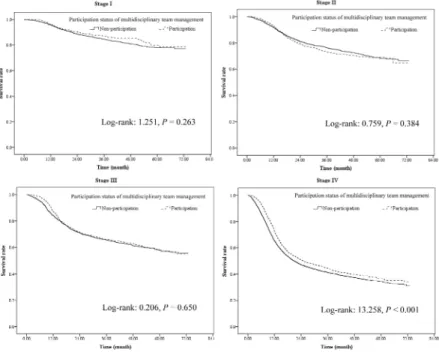

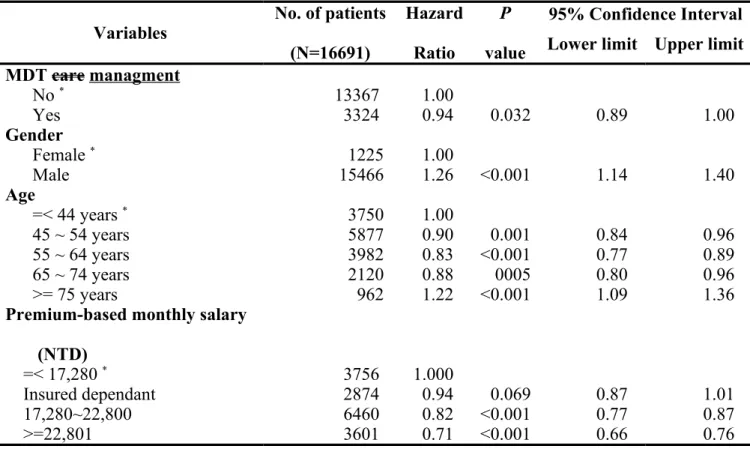

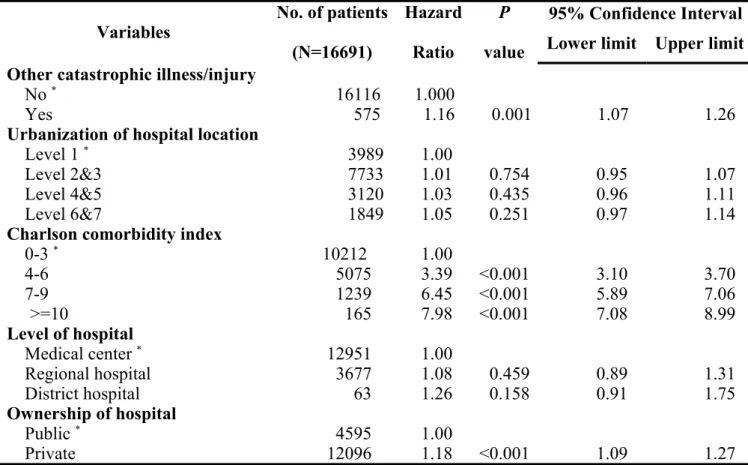

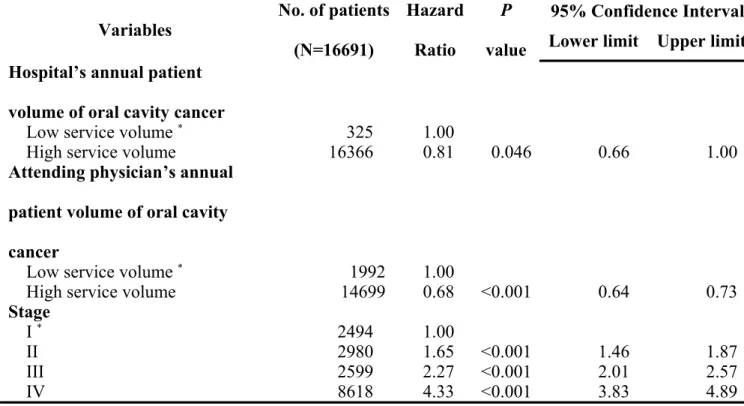

After controlling for other variables by logistic regression model, level of urbanization of hospital location and level of hospital had no influence on the survival. However, patients with MDT care management had better survival when compared with that of patients without MDT care management (Hazard ratio (HR): 0.94, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.89 ~ 1.00, P = 0.032). In addition, male patients had worse survival than female patients (HR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.14 ~ 1.40, P < 0.001). Furthermore, age, premium-based monthly salary, coexisting catastrophic illness/injury, CCI, ownership of hospital, treating hospital’s annual volume of oral cavity cancer patients, attending physician’s annual volume of oral cavity cancer patients, and tumor stage were all independent factors associated with improved survival of oral cavity cancer patients. Detail data are shown in Table 3 and the survival curves of the participants/non-participants according to the tumor stage are shown in Figure 1.

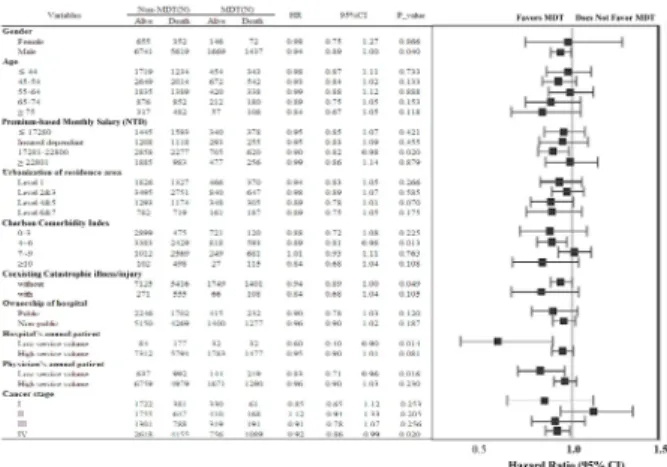

A modified Cox proportional hazard model was used to investigate the differences in the impact of survival on various subgroups. The male patients with

MDT care management subgroup was found to have a reduced risk of death (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89 to 1.00), CCI of 4~6 (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.81 to 0.98), no coexisting catastrophic illness/injury (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89 to 1.00), treating hospital’s low annual patient volume (HR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.40 to 0.90), attending physician’s low annual patient volume (HR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.70 to 0.96), and stage IV disease (HR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.86 to 0.99). Detailed data are presented in Figure 2.

Discussion

Our previous study found the hazard ratio of death was lower for oral cavity cancer patients with MDT care management when compared with that of patients without MDT care management.5 However, in the NHIRD there are no data on tumor

stage, which is an important confounding factor for tumor survival. In the present study, we cross-linked the participants with TCRD to obtain more information including tumor stage and histology type. After stratifying the participants according to tumor stage, oral cavity patients with MDT care management still had better survival when compared with those without MDT care management. It is not surprising that the treatment protocol for cancer can be optimized with the collaboration of surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists. A previous study found that nutritional factors had a significant influence on the survival of

patients with oral cancer. In addition, there was a remarkable and close relationship between host nutritional status and immunity. Early intervention with nutritional support in patients receiving cancer therapy might reduce side effects and ensure optimal therapeutic outcomes [16]. Our previous study on the effects of socio-demographic factors in oral cancer patients demonstrated that marital status and religious belief were significantly correlated with improved survival of oral cancer patients. Social support can eliminate stress-induced immuno-suppression. Moreover, higher perceived social support and active seeking of social support have been associated with increased natural killer cell activity which is widely recognized as having the capability to destroy cancer cells [3]. With the collaboration of psychologists, speech therapists, and nursing staffs, cancer patients can benefit from stronger social support. This increased social support might account for the improved survival of oral cavity cancer patients.

The role of gender in the survival of oral cavity cancer remains controversial [3,5,16,17]. Although the current study found female patients had a better survival when compared with that of male patients, the result could have been confounded by different patient/disease characteristics and dissimilar treatment protocols [17]. Previous studies indicated that local recurrence and distant metastasis rates in younger patients were higher when compared with those of older patients [18,19]. This might

explain why younger patients had worse survival when compared with that of older patients in our study. Premium-based monthly salary represents the income of patients. Low premium-based monthly salary was related to poor prognosis of oral cavity cancer in our study. This phenomenon was common in previous population studies in different countries [20,21]. Taken together, these findings suggest that even in a country with universal healthcare, socioeconomic disparities may have a significant impact on survival and healthcare authorities should pay more attention to such results [21].

A possible reason why hospital’s and attending physician’s high annual patient volume were related to better survival of oral cavity cancer might be due to the fact that high-volume service generally indicates that the hospital’s team has considerable experience treating oral cavity cancer. An experienced team possesses greater skills and performs the therapeutic protocol better, which leads to better treatment results [22]. A previous study indicated that patients with breast cancer treated by high-volume surgeons underwent proportionally more combination therapies when compared with those treated by low-volume surgeons [23]. This implies that high-volume surgeons tend to treat patients via MDT care management and low-high-volume surgeons were less likely to cooperate with oncologists or attend multi-disciplinary conferences. Coexisting catastrophic illness/injury, high CCI, and advanced tumor

stage all implied greater disease severity. It is readily apparent in the present study that these variables were associated with poor prognosis.

In terms of the beneficial impact of MDT care management on patient survival, male gender, premium-based monthly salary between 17,281 and 22,800 New Taiwan Dollars (NTD), CCI between 4 and 6, no coexisting catastrophic illness/injury, low service volume of the treating hospital and physician, and stage IV diseases contributed to favorable outcomes. As few previous studies have examined the survival benefits of MDT care management, it is somewhat difficult to explain or compare the aforementioned findings. However, it is reasonable to expect that patients with moderate comorbidities would benefit from MDT care management. Conversely, patients with severe comorbidities and coexisting catastrophic illness/injury may not benefit from integrated management. Low service volume of the treating hospital and physician implies that less experienced staff and the treatment outcomes of patients might be improved through discussion among team members. A previous study found that the survival of stage IV head and neck cancer patients was improved after MDT care management. Non-MDT care management included the possibility of less precise staging, insufficient related health education, and loss to follow-up, due to the lack of integrated management [24]. The results of this study also indicated that the use of multimodality therapy protocols in MDT was

significantly related to management of patients. This might explain why stage IV oral cavity cancer patients with MDT care management had better treatment outcomes in the current study.

There were several limitations in this study. First, it was not possible to definitively establish a causal relationship between MDT care management and survival of oral cavity cancer in this observational study. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to eliminate selection bias and other confounding factors. Second, this population-based study included data retrieved from the Taiwan’s NHIRD. Lifestyle information, which might correlate with survival, is not included in this database and thus was not included in final analysis model. Third, coding error does occur in an administrative database. To minimize this bias, every effort was made to correlate data by cross-linking with other databases as appropriate. Furthermore, MDT management in current study only mean t all the medical/surgical specialties are represented, not that the patient s also had access to nutrition/social work or palliative care . Finally, Taiwan’s NHIRD does not contain data pertaining to the cause of death. As a consequence, we could estimate overall survival, but not disease-free survival.

In conclusion, MDT care was associated with a better survival among patients with oral cavity cancer. O ral cavity cancer patients with MDT management appeared

to have slightly better survival rates compared with those of patients without MDT management. The beneficial effect of MDT care management on survival was stronger for male patients, among patients with a CCI between 4 and 6, in those without coexisting catastrophic illness/injury, and in patients with stage IV diseases.

Acknowledgements: The study was supported by grants from the National Science

Council, Taiwan, Republic of China (NSC101-2410-H-468-001), and China Medical University and Asia University (CMU100-ASIA-10), Taichung, Taiwan, Republic of China. The National Health Research Institutes provided access to the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). This study was based on data from the NHIRD provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and managed by the NHIRD, Taiwan. The manuscript was completed by the authors themselves without any paid writing assistance.

Role of the Sponsors: The National Science Council, China Medical University and

Asia University had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to

References

[1] Shah JP, Gil Z. Current concepts in management of oral cancer – Surgery. Oral Oncol 2009;45:394–401.

[2] Hsing CY, Wong YK, Wang CP, Wang CC, Jiang RS, Chen FJ, et al. Comparison between free flap and pectoralis major pedicled flap for reconstruction in oral cavity cancer patients – a quality of life analysis. Oral Oncol 2011;47:522–7. [3] Wong YK, Tsai WC, Lin JC, Poon CK, Chao SY, Hsiao YL, et al.

Socio-demographic factors in the prognosis of oral cancer patients. Oral Oncol 2006;42:893–906.

[4] Liu SA, Wong YK, Wang CP, Wang CC, Jiang RS, Ho HC, et al. Surgical site infection after preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Head Neck 2011;33:954–8.

[5] Wang YH, Kung PT, Tsai WC, Tai CJ, Liu SA, Tsai MH. Effects of multidisciplinary care on the survival of patients with oral cavity cancer in Taiwan. Oral Oncol 2012;48:803–10.

[6] Hughes C, Homer J, Bradley P, Nutting C, Ness A, Persson M, et al. An evaluation of current services available for people diagnosed with head and neck cancer in the UK (2009-2010). Clin Oncol 2012;24:e187–92.

[7] Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, Frost MH, Bostwick JM, Atherton PJ, et al. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured

multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:635–42.

[8] Zorbas H, Barraclough B, Rainbird K, Luxford K, Redman S. Multidisciplinary care for women with early breast cancer in the Australian context: what does it mean? Med J Aust 2003;179:528–31.

[9] Licitra L, Bossi P, Locati LD. A multidisciplinary approach to squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck: what is new? Curr Opin Oncol 2006;18:253–7. [10] Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, Lee CH, Lai ML. Validation of the National Health

Insurance Research Database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:236–42.

[11] Wu CY, Chan FK, Wu MS, Kuo KN, Wang CB, Tsao CR, et al. Histamine2-receptor antagonists are an alternative to proton pump inhibitor in patients receiving clopidogrel. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1165–71.

[12] Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG, Morrow M, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed. Chicago, IL: Springer; 2002.

[13] Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–9. [14] Rosenbaum PR, Rubin D. Reducing bias in observational studies using

subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc 1984;79:516–24. [15] Chatterjee S, Chen H, Johnson ML, Aparasu RR. Risk of falls and fractures in

older adults using atypical antipsychotic agents: a propensity score-adjusted, retrospective cohort study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2012;10:83–94.

[16] Liu SA, Tsai WC, Wong YK, Lin JC, Poon CK, Chao SY, et al. Nutritional factors and survival of oral cancer patients. Head Neck 2006;28:998-1007.

[17] Roberts JC, Li G, Reitzel LR, Wei Q, Sturgis EM. No evidence of sex-related survival disparities among head and neck cancer patients receiving similar multidisciplinary care: a matched-pair analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:5019-27.

[18] Garavello W, Spreafico R, Gaini RM. Oral tongue cancer in young patients: a matched analysis. Oral Oncol 2007;43:894-7.

[19] Liao CT, Wang HM, Hsieh LL, Chang JT, Ng SH, Hsueh C, et al. Higher distant failure in young age tongue cancer patients. Oral Oncol 2006;42:718-25.

[20] Andersen ZJ, Lassen CF, Clemmensen IH. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the mouth, pharynx and larynx in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1950-61.

[21] McDonald JT, Johnson-Obaseki S, Hwang E, Connell C, Corsten M. The relationship between survival and socio-economic status for head and neck cancer in Canada. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;43:2.

[22] Lee CC, Ho HC, Chou P. Multivariate analyses to assess the effect of surgeon volume on survival rate in oral cancer: a nationwide population-based study in

Taiwan. Oral Oncol 2010;46:271-5.

[23] Stefoski Mikeljevic J, Haward RA, Johnston C, Sainsbury R, Forman D. Surgeon workload and survival from breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2003;89:487-91.

[24] Friedland PL, Bozic B, Dewar J, Kuan R, Meyer C, Phillips M. Impact of multidisciplinary team management in head and neck cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2011;104:1246-8.

Figure 1 Overall survival curves of multidisciplinary team care management participants/ non-participants based on tumor stage

Figure 2 Multivariate stratified analyses of the association between multidisciplinary team (MDT) care managment and survival of oral cavity cancer patients

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of oral cavity cancer patients with or without multidisciplinary team care managment

Variables Total no. of patients (% in column) No. of patients (%) P value Without MDT care (n=13367) With MDT care (n=3324) Age, mean (SD), yr 16691 53.8 (11.8) 52.9 (11.5) 0.003 Gender 0.059 Female 1225 (7.3%) 1007 (82.2%) 218 (17.8%) Male 15466 (92.7%) 12360 (79.9%) 3106 (20.10%) Age 0.003 =< 44 years 3750 (22.5%) 2953 (78.8%) 797 (21.3%) 45 ~ 54 years 5877 (35.2%) 4663 (79.3%) 1214 (20.7%) 55 ~ 64 years 3982 (23.9%) 3224 (81.0%) 758 (19.0%) 65 ~ 74 years 2120 (12.7%) 1728 (81.5%) 392 (18.5%) > = 75 years 962 (5.8%) 799 (83.1%) 163 (16.9%)

Other catastrophic illness/injury 0.137

No 16116 (96.6%) 12892 (80.0%) 3224 (20.0%) Yes 575 (3.4%) 475 (82.6%) 100 (17.4%) Stage <0.001 I 2494 (14.9%) 2103 (84.3%) 391 (15.7%) II 2980 (17.9%) 2402 (80.6%) 578 (19.4%) III 2599 (15.6%) 2089 (80.4%) 510 (19.6%) IV 8618 (51.6%) 6773 (78.6%) 1845 (21.4%)

Charlson comorbidity index <0.001

0-3 10212 (61.2%) 8074 (79.1%) 2138 (20.9%)

4-6 5075 (30.4%) 4131 (81.4%) 944 (18.6%)

7-9 1239 (7.4%) 1028 (83.0%) 211 (17.0%)

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of oral cavity cancer patients with or without multidisciplinary team care managment (cont’)

Variables Total no. of patients (% in column) No. of patients (%) P value Without MDT care (n=13367) With MDT care (n=3324) Level of hospital <0.001 Medical center 12951 (77.6%) 10784 (83.3%) 2167 (16.7%) Regional hospital 3677 (22.0%) 2527 (68.7%) 1150 (31.3%) District hospital 63 (0.4%) 56 (88.9%) 7 (11.1%) Ownership of hospital <0.001 Public 4595 (27.5%) 3948 (85.9%) 647 (14.1%) Private 12096 (72.5%) 9419 (77.9%) 2677 (22.1%)

Hospital’s annual patient volumes of oral cavity cancer

0.975

Low service volume 325 (1.9%) 261 (80.3%) 64 (19.7%)

High service volume 16366 (98.1%) 13106 (80.1%) 3260 (19.9%)

Propensity score

Mean (SD) 0.23 (0.08) 0.19 (0.07) <0.001

Median (IQR) 0.20 (0.16~0.31) 0.18 (0.15~0.21) <0.001

Follow up period (month)

Mean (SD) 32.0 (19.7) 32.8 (19.4) 0.044

Median (IQR) 30.1 (13.5~47.0) 31.2 (14.5~46.6) 0.018

Abbreviations: MDT, multidisciplinary team; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of oral cavity cancer patients based on survival status

Variables Total no. of patients (% in column) No. of patients (%) P value Survival group (n=9221) Deceased group (n=7480) Gender <0.001 Female 1225 (7.3%) 801 (65.4%) 424 (34.6%) Male 15466 (92.7%) 8410 (54.4%) 7056 (45.6%) Age <0.001 =< 44 years 3750 (22.5%) 2173 (58.0%) 1577 (42.0%) 45 ~ 54 years 5877 (35.2%) 3321 (56.5%) 2556 (43.5%) 55 ~ 64 years 3982 (23.9%) 2255 (56.6%) 1727 (43.4%) 65 ~ 74 years 2120 (12.7%) 1088 (51.3%) 1032 (48.7%) > = 75 years 962 (5.8%) 374 (38.9%) 588 (61.1%)

Premium-based monthly salary (NTD) <0.001

Insured dependant 2874 (17.2%) 1501 (52.2%) 1373 (47.8%)

=< 17,280 3756 (22.5%) 1785 (47.5%) 1971 (52.5%)

17,280~22,800 6460 (38.7%) 3563 (55.2%) 2897 (44.8%)

>=22,801 3601 (21.6%) 2362 (65.6%) 1239 (34.4%)

Urbanization of hospital location <0.001

Level 1 3989 (23.9%) 2292 (57.5%) 1697 (42.5%)

Level 2&3 7733 (46.3%) 4335 (56.1%) 3398 (43.9%)

Level 4&5 3120 (18.7%) 1641 (52.6%) 1479 (47.4%)

Level 6&7 1849 (11.1%) 943 (51.0%) 906 (49.0%)

Other catastrophic illness/injury <0.001

No 16116 (96.6%) 8874 (56.6%) 6817 (43.4%)

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of oral cavity cancer patients based on survival status (cont’)

Variables Total no. of patients (% in column) No. of patients (%) P value Survival group (n=9221) Deceased group (n=7480)

Charlson comorbidity index <0.001

0-3 10212 (61.2%) 8074 (79.1%) 2138 (20.9%) 4-6 5075 (30.4%) 4131 (81.4%) 944 (18.6%) 7-9 1239 (7.4%) 1028 (83.0%) 211 (17.0%) >=10 165 (1.0%) 134 (81.2%) 31 (18.8%) Level of hospital <0.001 Medical center 12951 (77.6%) 7246 (56.0%) 5705 (44.0%) Regional hospital 3677 (22.0%) 1953 (53.1%) 1724 (46.9%) District hospital 63 (0.4%) 12 (19.1%) 51 (80.9%) Ownership of hospital <0.001 Public 4595 (27.5%) 2661 (57.9%) 1934 (42.1%) Private 12096 (72.5%) 6550 (54.2%) 5546 (45.8%)

Hospital’s annual patient volume of oral cavity cancer

<0.001

Low service volume 325 (1.9%) 116 (35.7%) 209 (64.3%)

High service volume 16366 (98.1%) 9095 (55.6%) 7271 (44.4%)

Attending physician’s annual patient volume of oral cavity cancer

<0.001

Low service volume 1992 (11.9%) 781 (39.2%) 1211 (60.8%)

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of oral cavity cancer patients based on survival status (cont’)

Variables Total no. of patients (% in column) No. of patients (%) P value Survival group (n=9221) Deceased group (n=7480) MDT care managment 0.462 No 13367 (80.1%) 7396 (55.3%) 5971 (44.7%) Yes 3324 (19.9%) 1815 (54.6%) 1509 (45.4%) Propensity score (SD) 0.195 (0.071) 0.204 (0.070) <0.001 Stage <0.001 I 2494 (14.9%) 2025 (82.3%) 442 (17.7%) II 2980 (17.9%) 2165 (72.6%) 815 (27.4%) III 2599 (15.6%) 1620 (62.3%) 979 (37.7%) IV 8618 (51.6%) 3374 (39.2%) 5244 (60.8%)

Table 3. Factors associated with survival in oral cavity cancer patients

Variables No. of patients

(N=16691) Hazard Ratio P value 95% Confidence Interval Lower limit Upper limit MDT care managment No * 13367 1.00 Yes 3324 0.94 0.032 0.89 1.00 Gender Female * 1225 1.00 Male 15466 1.26 <0.001 1.14 1.40 Age =< 44 years * 3750 1.00 45 ~ 54 years 5877 0.90 0.001 0.84 0.96 55 ~ 64 years 3982 0.83 <0.001 0.77 0.89 65 ~ 74 years 2120 0.88 0005 0.80 0.96 >= 75 years 962 1.22 <0.001 1.09 1.36

Premium-based monthly salary (NTD)

=< 17,280 * 3756 1.000

Insured dependant 2874 0.94 0.069 0.87 1.01

17,280~22,800 6460 0.82 <0.001 0.77 0.87

Table 3. Factors associated with survival in oral cavity cancer patients (cont’)

Variables No. of patients

(N=16691) Hazard Ratio P value 95% Confidence Interval Lower limit Upper limit Other catastrophic illness/injury

No * 16116 1.000

Yes 575 1.16 0.001 1.07 1.26

Urbanization of hospital location

Level 1 * 3989 1.00

Level 2&3 7733 1.01 0.754 0.95 1.07

Level 4&5 3120 1.03 0.435 0.96 1.11

Level 6&7 1849 1.05 0.251 0.97 1.14

Charlson comorbidity index

0-3 * 10212 1.00 4-6 5075 3.39 <0.001 3.10 3.70 7-9 1239 6.45 <0.001 5.89 7.06 >=10 165 7.98 <0.001 7.08 8.99 Level of hospital Medical center * 12951 1.00 Regional hospital 3677 1.08 0.459 0.89 1.31 District hospital 63 1.26 0.158 0.91 1.75 Ownership of hospital Public * 4595 1.00 Private 12096 1.18 <0.001 1.09 1.27

Table 3. Factors associated with survival in oral cavity cancer patients (cont’)

Variables No. of patients

(N=16691) Hazard Ratio P value 95% Confidence Interval Lower limit Upper limit Hospital’s annual patient

volume of oral cavity cancer

Low service volume * 325 1.00

High service volume 16366 0.81 0.046 0.66 1.00

Attending physician’s annual patient volume of oral cavity cancer

Low service volume * 1992 1.00

High service volume 14699 0.68 <0.001 0.64 0.73

Stage I * 2494 1.00 II 2980 1.65 <0.001 1.46 1.87 III 2599 2.27 <0.001 2.01 2.57 IV 8618 4.33 <0.001 3.83 4.89 * Reference group