Robust adaptive sliding mode control using fuzzy

modelling for

a class of uncertain MIMO nonlinear

systems

W.-S.Lin and C.-S.Chen

Abstract: A practical design that combines a fuzzy adaptation technique with sliding mode

control to enhance robustness and sliding performance in a class of uncertain MIMO nonlinear systems is proposed. Using an online adaptation scheme, a fuzzy sliding mode controller is used to approximate the equivalent control in the neighbourhood of the sliding manifold. The hitting control is appended to ensure that the fuzzy sliding mode control can achieve a stable closed-loop system for the trajectory-tracking control of a plant with unknown nonlinear dynamics. The proposed design simultaneously guarantees the stability of the adaptation of the fuzzy rules and obtains suitable equivalent control when the nominal mathematical model is unknown in advance. It also provides the designers with flexibility to design and implement the fuzzy rule base without domain experts and without a mathematical model. The robust adaptive scheme is applied to a two-link robotic manipulator and shown to be able to guarantee that the output tracking error will ultimately converge to a residual set.

1 Introduction

Conventional control theory is well suited to applications where the control efforts can be generated based on an analytical model [l, 21. Sliding mode control (SMC), based on the theory of variable structure systems (VSS), has been widely applied to robust control of nonlinear systems [3-81. Sliding mode control performs well in trajectory tracking of some nonlinear systems. It employs a discon- tinuous control law to drive the state trajectory toward a specified sliding surface and maintain its motion along the sliding surface in the state space. Hung et al. [7] have made a comprehensive survey of VSS theory. The dynamic performance of an SMC system has been confirmed as an effectively robust control approach with respect to system uncertainties and unknown disturbance when the system trajectories belong to predetermined sliding surfaces [9], However, SMC suffers from some difficulties. First, there are many physical systems with highly coupled nonlinear and uncertain dynamics for which it is generally difficult or even impossible to obtain accurate mathema- tical models. Secondly, to operate effectively in the sliding surface, SMC requires instantaneous change of the control input without sacrificing the robustness against the model uncertainties and external disturbances. The discontinuity in the control action becomes the cause of chattering, which is undesirable in most applications [7]. In practical implementations, the chattering may cause an unnecessa-

(0 IEE, 2002

IEE Pvoceedings online no. 20020236 DOZ: IO. 1049/ip-cta:20020236

Paper first received 19th July 2001 and in revised form 18th January 2002 The authors are with the Department of Electrical Engineering, National Taiwan University, No. I , Sec. 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China

LEE Proc.-Control Theory Appl., Vol. 149, No. 3, May 2002

rily large control signal as the system uncertainties are large and may damage system components such as actua- tors. Thus, the chattering has to be eliminated or alleviated

as much as possible. Finally, it is usually difficult to directly extend the SMC design into a multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) system, especially when the coupling among the subsystems is unknown.

The latest studies consider adding computationally intel- ligent methods to the SMC by automatically tuning the control parameters [ 101. In particular, integrating fuzzy set theory and SMC into fuzzy controller design has produced a superior performance [l l-171. Fuzzy logic control (FLC) is a model-free approach, which is synthesised by a collection of fuzzy IF-THEN rules to decide control action [18, 191. FLC has succeeded in many control applications that conventional control theories have had difficulties with. For complex or ill-defined systems that are not ,amenable to conventional control techniques, FLC provides an alternative approach for both collecting human knowledge and expertise, and dealing with nonlinearities. However, FLC lacks a formal synthesis technique and all fuzzy rules have to be supplied by human experts. To

overcome these drawbacks, the fuzzy sliding mode control (FSMC) technique, which is an integration of variable structure control and FLC, provides a simple way to design FLC systematically. This approach retains the positive property of SMC but alleviates the chattering, and the fuzzy control rules can be determined system- atically by the reaching condition of SMC. The main advantage of FSMC is that the control method achieves asymptotic stability of the closed-loop system. Thus, FSMC uses fuzzy control to construct the system dynamic model or the control while the fuzzy control rules and variables are obtained directly from the sliding surface equation.

Although FSMC has achieved many practical successes in many fields, several fundamental problems still exist in

the control of complex systems. In particular, the integra- tion of fuzzy set theory and SMC into fuzzy controller design, as well as the stability and robustness properties of such a system, are vigorous areas in fuzzy control research. The linguistic expression of fuzzy control makes it very difficult to simultaneously guarantee the stability and robustness of the fuzzy control system if the nominal mathematical model is unknown in advance. Furthermore, the huge amount of fuzzy rules needed for a high-order system always makes the analysis complex. In most of these studies, fuzzy controllers are designed with respect to a phase plane determined by error and change of error according to the state and change of state, which is usually inappropriate. Therefore, various tuning algorithms are usually employed to improve the performance of fuzzy sliding mode controllers. The main contribution of this paper is the implementation of this advanced adaptive SMC control strategy into the framework of fuzzy models. This paper will address the problem of controlling an unknown MIMO nonlinear affined system. The goal is to develop an adaptive MIMO fuzzy sliding mode controller to overcome the interaction among the subsystems by a decoupling neural network and to facilitate robust proper- ties by fine-tuning the consequent membership functions. First, a sliding mode controller for robust tracking control of multivariable nonlinear systems is developed by assum- ing that imposed uncertainties are bounded and satisfy matching conditions. The fuzzy logic control is then designed on the basis of the SMC law. An FSMC is used to approximate the equivalent control in the neighbourhood of the sliding manifold with online fuzzy self-tuning parameters subject to parameter variations in the control object. Secondly, the hitting control is appended to ensure that the proposed FSMC can result in a closed-loop system that is stable for the trajectory-tracking control of a plant with unknown nonlinear dynamics. As a result, we simul- taneously guarantee the global stability of the closed-loop system and obtain a suitable equivalent control when the nominal mathematical model is unknown in advance. In path tracking systems, considerable attention is paid to the control of uncertain dynamical nonlinear systems that are subject to certain internal parameter variations and external disturbances. This scheme also provides the designers with flexibility to design and implement the fuzzy rule base without domain experts and without mathematical model.

2 Problem formulation and sliding mode control

Consider a MIMO nonlinear system whose equations of motion can be governed by

y(') = f ( x )

+

G(x)u+

d(x, t ) (1) where y =b l , .

. . , y J T and y(")=by'),

..

, ,y$>)lT denote the output vector and its derivative, respectively, Y = [ r l ,. . .

, rt17] with ri = n is defined as the system relative degree, u = [uI , ..

. , uJT is the input, x = [xl , x2,is the state

. . .

, xn] = k l , ..

. ,,$-'), y 2 , . . . ,y,,,"' ( rvector, G(X> = k l ( X ) , ' . ' 3 gm(x)~>

.h(x>

and gi(x> = [gli(x), . ..

> g n i i ( ~ > ~ ~ with gii > 0,i = 1 , .

. .

, m , are unknown functions, and d(x, t)=[dl(x, t), .

. .

, d,,(x, t)lT is the disturbance with the proper- ties of standard smoothness and it is assumed to have an upper bound D = diag[D;], that is,I

&(x, t )I

5 D j ,i = 1, . .

.

, nz.If we let yc/ = [ y c / l , y d 2 ,

. .

. , yrc,77] represent the known desired trajectories, the intention is to determine a control-T

Ax)

= cfi(x>,. . .

>J?,(41?

194

ler for the composite nonlinear system described by (1) so that the tracking error represented by

4 = [ e , , . .

.

, em]with e, = [e,, E,, .

.

. , e , ] = b d , - y , , j d L - j l , .. .

,arbitrarily small residual tracking error set. Further, we define a set of sliding surfaces in the error space passing through the origin to represent a sliding manifold as fo1lows: (2) T ( , , - I ) T & l ) - p 1 ) ] T I , i = 1,.

. .

, m, will be attenuated to an T s = [SI, s2, . . . , s,,]and A; =

[ a j l ,

. .

. , ail.,IT E R" be such that all roots of the polynomialare in the open left half-plane, i = 1,. . . , m.

The process of sliding inode control can be divided into the reaching phase with s,

#

0 and the sliding phase with s, = 0 , i = 1 , .. .

, m. If the sliding mode exists on s, = 0, then from the theory of variable structure systems and sliding mode control [20], the motion of the system is governed by linear differential equations (3) whose beha- viour IS dictated by the sliding manifold design. Since (4)guarantees (3) to satisfy the Hurwitz stability criterion, the origin in the subspace s, is asymptotically stable with a

finite convergence time for each x, from s [21]. Thus, maintaining the system states on the sliding manifold s for all t > 0 is equivalent to the tracking problem y = y d , i.e. it

is required that the system errors converge to zero. Then, the system has invariance properties against external disturbances and parameter uncertainties.

If the system state is outside the sliding manifold s, the controller must be designed such that it can force the system states to approach the sliding manifold and then move along the sliding manifold to the origin. By choosing the Lyapunov function candidate VI =i(sTs,),

i = 1,.

. .

, nz, an equivalent control is given first such that each state Lyapunov-like condition holds for system stabi- lity [4]or in sum

Inequality (5) constrains the trajectories to point towards the sliding surface si(t) such that the distance to the sliding surface decreases along all system trajectories as illustrated in Fig. 1, and is referred to as the reaching condition [3]. To meet the reaching condition, a hitting control term i i h

must be added to guarantee the reaching condition (5) in the presence of parameter and disturbance uncertainties. That is, the states of the system are driven from any initial state to the eventual sliding surface on which sliding mode control takes place.

It is obvious that to obtain the sliding mode control law, the control strategy consists of two design goals: first, to

Fig. 1 Illtistrution of the sliding condition

force the system toward a desired dynamics; and secondly, to maintain the system on that differential geometry. Motivated by the principle of SMC, the equivalent control

ii,,

is estimated by using an adaptive mechanism thatforces the system state to slide on the sliding manifold and the hitting control iilz that drives the states toward the sliding manifold. Thus the control law can be represented as

u =

G,,

+

=,

G

+

G - ' u ~ , (7) where he, and iih> respectively, are yielded through fuzzy and nonfuzzy design modes.3 Design of the fuzzy sliding mode controller

One of the essential elements in designing a sliding mode controller is the model of the dynamical system to be controlled. In many situations, accurate mathematical models of the system are not available or are difficult to formulate, or are incomplete because the plant has a

complicated design. It is obvious that the difficulty for MIMO systems control is how to overcome the coupling effects among each degree of freedom. To solve these difficulties, we need a tractable model for the controller. An appropriate decoupling network is incorporated into this tractable model to control the MIMO systems to compensate for the dynamic coupling between each degree of freedom. We developed a new control approach for controlling MIMO systems by combining the fuzzy approximator of the system with its MIMO sliding mode control, resulting in a decoupled fuzzy sliding mode controller. That is, the fuzzy logic system theory is applied to design the sliding mode controller for system (1).

The design objective is to choose a sliding manifold s satisfying the Hurwitz stability criterion and the related discontinuous control law such that the error state attains a

sliding mode. If we design a controller that satisfies the reaching condition ( 5 ) , then the system state will approach the sliding surface from any initial state within a finite time and move along the sliding surface to the origin. This implies that the system dynamics are governed only by the sliding surface and will track the reference trajectory asymptotically. Therefore the control problem is to obtain the optimal control input U * that guarantees the reaching

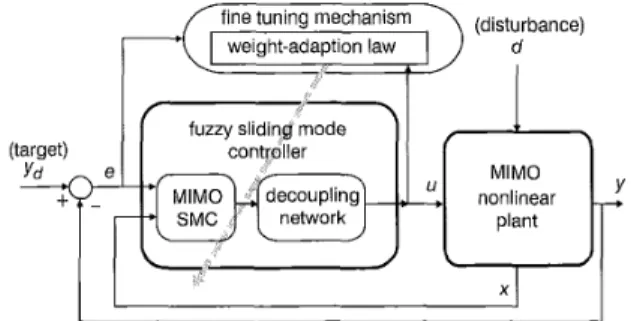

condition ( 5 ) . The ideas behind the controller are as follows. The proposed adaptive fuzzy sliding mode controller is composed of three parts: an MIMO SMC, a fine-tuning mechanism on the consequent membership functions of the multilayer fuzzy system, and a decoupling network. Fig. 2 shows the configuration of the MIMO sliding mode controller and the interconnected compensat- ing network of the adaptive fuzzy control system. The multilayer fuzzy system and the decoupling network are

IEE Proc -Control Theor)) A p p l , Vol 140, No 3, Moy 2002

fine tuning mechanism (disturbance)

I

weight-adaption law1

d'

fuzzy slidind mode'

I

MIMO nonlinear plant (target) controller X Y

Fig. 2 Configiiration ojthe aduptive fuzzy sliding mode control system

nominal designs based on an online approximation of the unknown nonlinear functions of the plant. The fine-tuning mechanism is designed to encounter the equivalent uncer- tainty resulting from the plant uncertainty, the function approximation error, or the external disturbances.

Consider the nonlinear system (1) and let the sliding surface be defined as in (3). Let u! be the output of the system's ith MIMO SMC. Then, for the system given in ( l ) , the ith sliding surface is si. Hence, this MIMO SMC also has m sliding surfaces to form a sliding manifold so that the system exhibits desirable behaviour when its trajectories are confined in the sliding surfaces. If the control law is designed such that the sliding mode exists on s i = O , i = 1 , .

. .

, m, the system error dynamics are dictated by the linear dynamic equations ( 3 ) . Since (3)satisfies the Hurwitz stability criterion from (4), maintain- ing system states on sliding surfaces for all t > 0 is equivalent to requiring that the system errors converge to zero. Thus, the tracking control problem can be formulated by keeping the tracking error 2(t) = [el,

. . .

, e,JT on the sliding manifold defined as follows:= &) - f ( x ) - C(X)U - d(x, t )

Theorenz 1: If the functions f , G and d of the nonlinear

MIMO systems ( I ) are known and do not take the inter- connections among the subsystems into consideration, then the control law uo can be chosen as follows:

p- 1

- f (x) - d(x, t ) +y$'

+

K sgn(s)(9) where P = diag[gii], K = diag[Ki] is m x m positive define diagonal gain matrix with Ki > 0, sgn(s) [sgn(sl) sgn(s2)

. . .

sgn(sm)lT and sgn(sJ is defined as 1 S j > O sgn(si) =l

0 si = 0 (10) -1 S j 1 0 and K sgn(s) = [Kl sgn(sl),. . .

, Km ~ g n ( s , ~ > l ' (1 1)Thus, the reaching condition (5) can be easily verified.

Pro$ If the functions J; G and d are known and

G =

P

= diag[gij] is a diagonal matrix, the optimal sliding mode control law can be represented aswhere

vi

> 0, and (c) is the state trajectory to hit the sliding surface no matter where the initial state is. Therefore the optimal control is I 11 avey-j' - ~ ; ( x ) - d,(x, t ) +y$:' u* = g ?["'

j = I1

+

hi sgn(s,) .vi

where 1, if si#

0 0, if si = 0 h i ={

This optimal sliding mode control input u? guarantees the reaching condition of (5). This completes the proof.

Since the control of nonlinear MIMO systems uses the sliding mode control directly but does not take the inter- connections among subsystems into consideration, the interconnection compensating network is needed. Thus, the proposed sliding mode controller has a neural part to release the interaction among the subsystems. The output of the controller is combined with uo and its modification by a decoupling network

u(t) = U O ( t )

+

MuO(t) (12)To derive a stable weight adaptation in the control matrix, the matrix M be chosen as

M = -(In1

+

(13)where I , denotes a m x m identity matrix and

1 :

gm1 gm2 :. . .

'.

0 1The nonsingularity supervisor is introduced to monitor the situation of rankLC) < m. If C is found to be singular, it

is perturbed as C + [dll]mxm to obtain full rank, where is an m x m matrix with small value component [a,]. Then the weight matrix M in (12) is guaranteed to

exist.

Using (9), (12)-(14) and the matrix inversion

( A +BCD)-' =A-l -

A-'B(DA-'B

+

C - y D A - ' [22],the formulation of MIMO SMC resolves into u = G-' r2-I i= 1 2i a e(r2-i)

1

- f ( x ) - d(x, t )+$'

+ K sgn(s)where G = C

+i!

By plugging u into (8), we will haveS = -Ksgn(s). Thus, the reaching condition (5) can be easily verified.

H?wever, f and G are unknown, only their estimations7

and G can be used to construct u. Moreover, to account for

the system uncertainties and disturbance, each

Ki

is chosen to be large enough to satisfy the reaching condition. It can be seen from (15) that the control input u is discontinuousacross s(t), which leads to unwanted chattering. An adap- tive fuzzy controller is proposed to eliminate the chattering and to achieve practical applicability of the proposed sliding control design.

4 Description of the adaptive fuzzy system

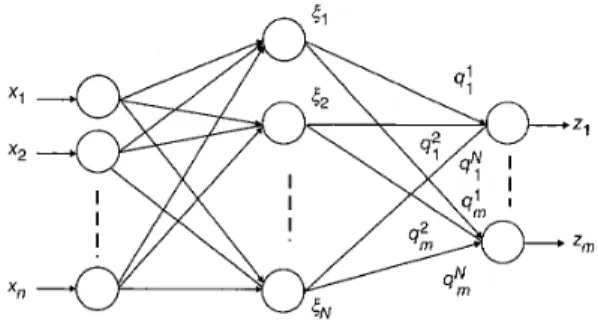

Various fuzzy models and their control have been success- fully applied in many fields [2 1, 23-26]. The basic config- uration of the fuzzy logic system comprises four principal components: fuzzifier, fuzzy rule base, fuzzy inference engine and defuzzifier [18]. The fuzzy control rules are the principal factor in determining the performance of a fuzzy controller. The fuzzy system can uniformly approx- imate nonlinear continuous functions to arbitrary accuracy [27, 281. Thus we will introduce fuzzy systems, which are expressed as a series expansion of fuzzy basis functions, to model the uncertainties G(x) andflx) by tuning the para- meters of the corresponding fuzzy systems. The configura- tion of the fuzzy system with adjustable rule credit assignment is shown in Fig. 3 [29].

The fuzzy logic system performs a mapping from U

c

R" to V c R m . Let U = U 1 x' . .

x U,, and V = V l x .. '

x V, where U,<C R , k = 1 , 2 , .. .

, n and V,c

R , i = I , 2 , . ..

, m. AIEE Proc-Control Theory Appl., Vol. 149, No. 3, May 2002

r

Dicigramnmtic representation of firzzy systems with adjustable

Fig. 3

rule credit assigninent

multivariable system can be controlled by the following

N

linguistic rules:

I?('):

IF xI is A{ and. . .

and x, is Af,THEN zl is B[1 and

.

..

and z,, is B:,, (16) where 1 = 1,. . .

, N, xli, k = 1, 2 , ..

, , n, are the input vari- ables to the fuzzy system, z , , I = 1, 2, . ..

, m, are the outputvariables of fuzzy system, and the antecedent fuzzy sets A i in

uk

and the consequent fuzzy sets Bf inv,

are linguistic terms characterised by the fuzzy membership functionsp A ~ ( x n ) and pB!(z,). The fuzzy logic system with centre- average defuzzifier, product inference and singleton fuzzi- fier is defined as [I81

N

c

PYX> ' 4:c

d ( x >z,(x) = /=IN (17)

I= I

where p''(x) =

ni=l

p,&) is the matching degree of the lth rule, and 41 is the centre of the consequent membership function of the lth rule. If 41 is chosen as the design parameter, the adaptive fuzzy system can be viewed as the type of neural network shown in Fig. 4 [30]. Therefore, (17) can be rewritten aswhere q5 =

@:,

. . .

, 4YlT is a parameter vector, $(x) =.

, ,tN)

is a regressor, and where the fuzzy basis function is defined as [ 181z,(4

=dm.4

(18) nn

/-lAi(x.k) k= I (19)t/

=/'=I

5

(ii

k = l P&J)5 Learning algorithm and performance analysis

We now show how to derive an adaptive law to adjust the controller parameters such that the estimated equivalent control

a,,

can optimally approximate the equivalent control of the FSMC, given the unknown functions f andG. We construct the hitting control to guarantee the

system's stability by the Lyapunov theory so that the ultimately bounded tracking is accomplished.

We define the control u =

&,

+

u,, where the auxiliary input isIEE Proc.-Control Theory Appl., K j l . 149. No. 3, May 2002

and where D = diag[Dj],

7

= diag[qi], i = 1 , ..

.

,

m and the hitting control is u,, = G- uh.We define the parameters 0: € R N and w $ € R N of the best function approximation as

r 7

r 1

where Q , and Q Z w q are constraint sets for

Bi

and w q ,i, j = 1,

. . .

, m, is defined as Q, = {Oi:

1

I

5 MO ,,,,, ,,,} and specified by the designer. The fuzzy logic systems &xI

Oi)and &(x

I

wii) areQ>",, = { w i j :

I

Wi/l F M W ,,,,J

where Mo,,,w,,, andM,"

,,,, w,,l areJ(xl

e;)

=e:

.

</(X) = @x).

e i

( 2 1)where < f ( x ) and Cg(x) are vectors of fuzzy bases, Oi and wii are the corresponding parameters of the fuzzy logic systems. Thus (8) can be rewritten as

where 8, = 8, - OF, = w,, - w;, denotes the parameter

estimation errprs, and the minimum approximation errors are &=fix

I

e*)

- f i x ) ,CG

= G(xI

w*)

- G(x) withOur design objective is to specify the control and adaptive

- 6 =

[e,,

. .

.fM,

w

= [ W I I ,. . .

, w1,,,,

W ~ I , . . . , wIIII~,1.I

n

zm

' n

Fig. 4 Basic structure of an adaptib.e,ftizzy system

laws for 8; and wii such that the reaching condition (5) is guaranteed.

Theorem 2: Consider a nonlinear plant (1) with a controller (7). The tracking error allows us to use the following adaptive law and hitting control as

8 . I = -s.y.<. i l j (24)

where i, j = 1,

. . . ,

m. After straightforward manipulation, the time derivative of V, is obtained asPro05 Consider the Lyapunov candidate

= srii 5 0.

v =

V , + V , + " ' + V m (27) whereBy the fact

8 i =

fli,

kii=

wij and (23), we obtain the derivative of Vaswhere

-

If we choose the adaptive law as 8i=-siyi@,

6, = - ~ ~ [ ~ ~ ~ < ~ f i ~ ~ , ~ and each

Ki

is chosen sufficiently large thatI

sjKi.

D i

.

sgn(s;)I

>I

sid;(t)I ,

thenJIZ

5

5 sii;i+

s; l & j j - (29)j = I

where we use the fact that ulZi has the same sign as si. To complete the FSMC design, it is necessary to show that the hitting control is enough to force the state trajec- tory toward the sliding surface as well as to establish asymptotic convergence of the tracking error. Consider the Lyapunov function candidate

1

v.

'

!

2 ' 32 (30)Taking the derivative of (30) and using (7) and (S), one has

(3 1)

To ensure that (31) is less than zero, the hitting control should be selected as

I ~Imax U

I

h e q jI

+

1~2:)

I

I

j=lI

J

This means that the inequality R.=s+ki < 0 is obtained and the hitting control actually achieves a stable FSMC system. This completes the proof.

From the above discussion, we use an FSMC to estimate the equivalent control of the SMC system. In addition, the requirement of the system stability is also proved and ensured by the hitting control. However, the hitting control part described previously is a high gain bang-bang control. It is usually proportional to the bounds ofJ; and go in (26) and is discontinuous across si so that heavy chattering arises. In addition, a very large control force may be generated and may activate high-frequency unmodelled dynamics [4]. These drawbacks have been considered in

[20], where the boundary layer concept was utilised as a compact measure of the equality of the uncertainty esti- mate. In fact, as si is large, the upper bounds ofJ; and gii are appropriate choices, but for small si these bounds may be unsuitable. This implies that bound on si can be directly considered when minimising the hitting control.

From empirical knowledge of the design of sliding mode controllers, the equivalent control is used when the state trajectory is near si=O. While the hitting control is appended in the case of si#O [20], a large hitting control will force the state trajectories to approach the sliding surface si=O rapidly, but at the same time, tend to excite chattering. Thus, when the state trajectories are far from the sliding surface, that is, when the value of

I

siI

is large, the hitting control should be correspondingly increased and vice versa. Furthermore, in the region1

si1

5 sf with s! > 0,it can be treated as the boundary layer of the conventional sliding mode control [4]. Thus, to maintain the attractive- ness of the boundary layer, we minimise the hitting control in (26) by a fuzzy function in practical implementation [3 11. The equivalent control and the hitting control are on the consequent membership functions of the fuzzy system. The consequent membership functions of the fuzzy control

rules are well defined to satisfy the stability of the control system. Therefore, a fuzzy rule base is of the form

If si is ZO Then zii is zii = Gel,, (32) If s, is NZ Then zi, is ui =

2

,

;

+

Girl

(33) where ZO and NZ denote zero and nonzero fuzzy sets, respectively, and the input variable si is given in (3). The modified control law of the fuzzy controller for (7) is/-lzo(si)

.

ceqi+

/-lNZ(~i)[Gec,i+

i,iiI~ Z o ( s i )

+

/ - L d s i )Z l j =

= Geqi

+

PNz(si)G/,i (34) where pzo(si) and pNZ(si) are the membership functions of fuzzy sets ZO and NZ, respectively. The membership functions of fLizzy sets ZO and NZ are selected to overlap and be symmetric to satisfy ,UZ&~)+

p ~ ~ ( s i ) = 1.If we choose the triangle membership functions as shown in Fig. 5 for the fuzzy sets ZO and NZ of si, the control law zii will be continuously adjusted by the use of the fuzzy logic depending on a ‘ZO’ layer s!. When holding the condition IsiI>s!, it can be seen that the control law is the same as the proposed FSMC. However, the amount of hitting control in region 1s;

I

< s! is domi- nated by the grade of the membership function of NZ, that is, the hitting control could be attenuated by the grade of NZ.6 Simulation results

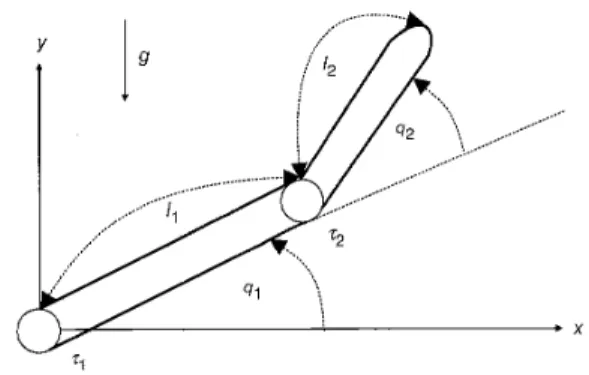

Here, we demonstrate the proposed FSMC by the tracking control of a two-link robotic manipulator with two degrees of freedom in the rotational angles described by angles ql

and q 2 , as shown in Fig. 6. The aim is to produce some torque signals that create a sliding motion in the phase plane for each link. The dynamic equations describing the motion of the robotic system are derived by the Lagrange scale function L(q, q ) [32], and are defined to be

L(q,

4)

= T ( q ,4)

- U(Y34)

(35) where T(q, q ) and U(q,4 )

are the total kinetic and potential energy. respectively, q = [ql q2]? The Lagrange equation has the formwhere z = [ z l z 2 I T c R 2 is the vector of the externally applied torques along the directions of their corresponding generalised coordinates q. Suppose the robotic system suffers from time-varying parametric uncertainties, un- modelled friction forces, and exogenous disturbances.

L‘

I

NZ

I

NZ-S! 0 S !

Fig. 6 Moclel of n two-link rohotic nicinipulutor

After some manipulation, the dynamic equations are of the following form [33]:

m l

+

m2)ry+

nz2r;+

2m2rlr2c2+

J l m 2 4+

nz2rlr2c2 m2r;+

m2r11a2c2 m2r;+

J21

(37) or in matrix form

M ( q ) i l + C(q,

4)

+

N q , g) = z+

d ( q ,4,

0

(38) where M( ) E R 2 x 2 denotes the moment of inertia,C(q, q ) E R is a vector of Coriolis and centrifugal force,

h(q, g ) E R 2 is a vector of gravitational forces with g = 9.8 m/s2 is the gravity constant and d(q, q, t ) E R2 is disturbance. In (37), the nominal parameters m l , m 2 , J I , J 2 , r1 = 0.511, and r2 = 0.5l2 are the mass, the moment of inertia, the half-length of links 1 and 2, and the shorthand notations are c2 E cos(q2), s2 sin(q2), c12

=

cos(gl+ q 2 ) , etc. The combined effects of friction and the external torque disturbance are4 .

d, = 2.0 sin(ql)

+

2.5 sin(q2)+

0.5 sin(t) d, = 5.0 sin(ql)+

4.0 sin(&)+

0.4 sin(t) In the control experiments described below, the kinematics and inertial parameters of the arm are chosen as ~ I = 2 . 0 4 i n , 12= 1.66m, J l = J 2 = 4 . S kg.m, m , =0.6Okg, m2 = 7.02 kg, respectively. The trajectories to be followed are described by two decoupled linear systems from (3), the desired coefficients are specified to be a,, = 2, aZ2 = 1,i = I , 2. The robot is given by the following target joint rotations:

qdl = ( 2 . 5 ~ / 1 2 ) . sint q L [ 2 = ( 3 . 7 5 ~ / 1 2 ) ’ cost

with the initial states 41(0) = 1 .S rad, q2(0) = - 1.2 rad,

ql(0) = 0 rad/s and q2(0) = 0 rad/s.

In (24)-(26), the design parameters are given by y , = 0.1, [j,=O.Ol, K,= 1, ql=O.O1, D,=S and i, j = 1, 2 . The

membership functions of states q l , q 2 , q 1 and Q2 (repre-

sented by generic variable n,) for the qualitative statements

( N = S4 = 625 regular rule partitions) are defined as { N B , NS, ZE, PB, P S } where NB: exp(-0.S(x,+0.4)2), NS: exp(-O.S(x,

+

0.2)2j, PB: exp(-O.S(x, - 0.4)2), PS: exp(-O.S(x, - 0.2) ) and ZE: exp(-O.Sxf). In (32) and(33), the membership functions of s, for the fuzzy sets ZO and NZ are given in a triangle function, as shown in

has the property that, for all s,, yz&,)+ When holding the condition Is,

I

>

s,' with can be seen that the control law is the same as the proposed FSMC. However, the amount of hitting control in region Is,I

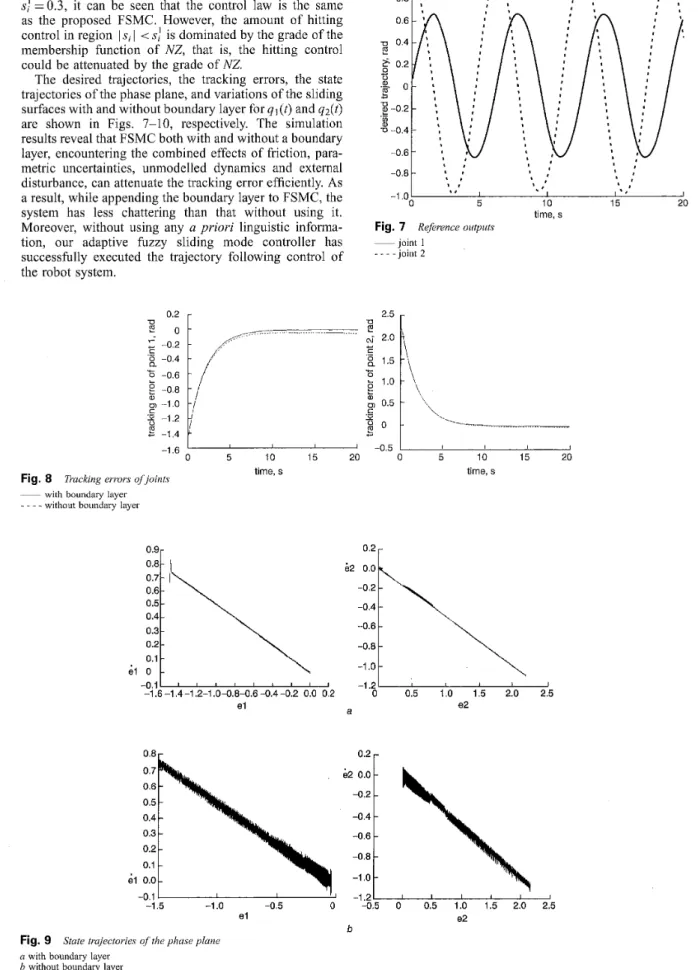

< sl is dominated by the grade of the membership function of NZ, that is, the hitting control could be attenuated by the grade of NZ.The desired trajectories, the tracking errors, the state trajectories of the phase plane, and variations of the sliding surfaces with and without boundary layer for q l ( t ) and q Z ( t ) are shown in Figs. 7-10, respectively. The simulation results reveal that FSMC both with and without a boundary layer, encountering the combined effects of friction, para- metric uncertainties, unmodelled dynamics and external disturbance, can attenuate the tracking error efficiently. As a result, while appending the boundary layer to FSMC, the system has less chattering than that without using it. Moreover, without using any a priori linguistic informa-

tion, our adaptive fuzzy sliding mode controller has successfully executed the trajectory following control of the robot system.

~~ 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 e1 0.0- 0.2

P

o

r I -0.2 0 -0.4 0 -0.6$

-0.8 -1.0 -1.22

-1.4 ._ Q "- L c e2 0.0 -0.6 -0.8-

--

--

- __ .-... 1 .o 0.8 0.6 u 0.4 s6

0.2.$

0 I c 73 g -0.2 3 .- U -0.4 -0.6 I ' ' I I ' ' , , '.'

1 , I ', -0.8 I, , , I , s ,,

-1 .o I 0 5 10 15 20 time, sFig. 7 Re?rence oiitputs

~ joint 1

_ _ - -

joint 2 2.5-

'

I I I I I 0 5 10 15 20 0 5 10 15 20 time, s time, s -1.6 IFig. 8 Trucking errors 0jjoint.s

~ with boundary layer

_.._ without boundary layer

0.9 0.6 0.5 -0.4 e1 0 0.1

\

-0.11 ''

' I ' ' ' ' 1 -1.6-1.4-1.2-1.0-0.8-0.6-0.4-0.2 0.0 0.2 el a -1I

:

:

:

b

-1.2 .o 0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 e2 0.2 r 0.8 r0.20 0.15 0.10 0.05 Sl 0 0.05 -1.10 -1.15 -0.20 1 I I I I -

-

- - P --

0.15,- 0 10 0 05 SI 0 -0 05 -1 10 -1 15 -0 20 --0.25[ 4 I I I 0 5 10 15 20 time, s Fig. 10a with boundary layer h without boundary layer

Vnriations of the sliding snrfaces

7

ConclusionsAn adaptive fuzzy controller based sliding mode control has been proposed for the robust trajectory tracking of MIMO control systems with unknown nonlinear dynamics. The core of this structure does not require knowledge of the system dynamics and parameters to compute the equivalent control, and an adaptive fuzzy system is devel- oped to further compensate the system uncertainty and ltnowledge incompleteness. This design obtains robustness in the sense that the self-tuning mechanism can automati- cally adapt the fuzzy controller by using a learning algo- rithm and the global asymptotic stability of the algorithm is established via the Lyapunov stability criterion. When matching with the model occurs, the overall control system becomes equivalent to a stable dynamic system. The simulation presented in the two-link robotic manip- ulator control indicates that the proposed approach is capable of achieving a good chatter-free trajectory follow- ing performance without the knowledge of the plant para- meters. In conclusion, the proposed FSMC is superior to its predecessors. The design can achieve the goal of compo- site nonlinear multivariable control and also guarantee that the output tracking error can ultimately converge to a

residual set.

8 Acknowledgment

The financial support for this research from the National Science Council of Taiwan, Republic of China under grant NSCS9-22 12-E002-093 is gratefully acknowledged.

9 References 1

2

ISIDORI, A.: ‘Nonlinear control systems: an introduction’ (Springer- Verlag, New York, 1989)

SINGH, S.N.: ‘Decoupling of invertible nonlinear systems with state feedback and precompensation’, IEEE Trans. Autom. Control, 1980, 25,

EDWARDS, C., and SPURGEON, S.K.: ‘Sliding mode control: theory and applications’ (Taylor and Francis, London, UK, 1998)

SLOTINE, J.J.E., and LI, W.: ‘Applied nonlinear control’ (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs. New Jersey, 1991)

( 6 ) , pp. 1237-1239 3

4

IEE Proc.-Control Theory Appl.. Vol. 14% No. 3, M a j 2002

2.5 2 . 0 / 0.5 s2 -0.5 O L -2.5 2.0

1

-0.5 I , I 1 1 0 5 10 15 20 time, s b5 UTKIN, VI.: ‘Sliding mode in control and optimization’ (Springer- Verlag, New York, 1992)

6 ZLNOBER, A.S.I.: ‘Variable structure and Lyapunov control’ (Springer- Verlarr. New York. 1994)

7

8

HUNG, J.Y., GAO, W., and HUNG, J.C.: ‘Variable structure control: a survey’, IEEE Puns. Ind. Electron., 1993, 40, (I), pp. 2-22

YOUNG, K D . , UTKIN, VI,, and OZGUNER, U.: ‘A control engineer’s guide to sliding mode control’, IEEE E m s . Control $xt. Techno/. ,

1999, 7, (31, pp. 328-342

9 KIM, S.W.; and LEE, J.J.: ‘Design of a fuzzy controller with fuzzy sliding surface’, Fuzzy Sets Sysf., 19Y5, 71, (3), pp. 359-367 10 KAYNAK, O., ERBATUR, K., and ERTUGRUL, M.: ‘The fusion of

computationally intelligent methodologics and sliding-mode control - a survey’, IEEE Truns. Inti. Electron., 2001, 48, (I), pp. 4-17

I I BERSTECHER, R.G., PALM, R.P., and UNBEHAUEN, H.D.: ‘An adaptive fuzzy sliding-mode controller’, IEEE Puns. Ind. Electron.,

2001, 48, (l), pp. 18-31

12 HA, Q.P., NGUYEN, Q.H., REY, D.C., and DURRANT-WHYTE, H.F.: ‘Fuzzy sliding-modc controllers with applications’, IEEE Enns. l i d .

Electron., 2001, 48, ( I ) , pp. 3 8 4 6

13 PALM, R.: ‘Sliding mode fuzzy control’. First IEEE Conference on Fuzzy systems, San Diego, USA, 1992, pp. 519-526

14 PALM, R.: ‘Robust control by fuzzy sliding mode’, Automaticti, 1994, 30. . (9). \ . . ’ . DD. 1429--1437

15 YOO, B.: ‘Adaptive fuzzy sliding inode control of nonlinear system’, 16 CIHOI, S.B., and KIM, J.S.: ‘A fuzzy-slidiiig mode controller for robust

IEEE Puns. Ftfzzy SYS~., 1998, 6 , (2), pp. 315-321

tracking of robotic manipulators’, &/echu&zics, 1997, 7, (2), pp, 199-- 216

17 LU, Y.S., and CHEN, J.S.: ‘A self-organizing fuzzy sliding-mode controllcr design for a class of nonlinear servo systems’, IEEE Puns. Ind. Electron., 1994, 41, (5), pp. 492-502

18 WANG, L.X.: ’A course in fuzzy systems and control’ (Prenticc-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1997)

19 LEE, C.C.: ‘Fuzzy logic in control systems: fuzzy logic controller - Part I’, IEEE Puns. Syst. Mun Cybern., 1990, 20, (2), pp. 404-418

20 UTKIN, VI,: ‘Variable structure systems with sliding modes’, IEEE Pans. Atitom. Control, 1977, 22, (2), pp. 212-222

21 UTKIN, V;, GULDNER, J., and SHI, J.: ‘Sliding mode control in electromechanical systems’ (Taylor and Francis, London, UK, 1999) 22 HORN, R.A., and JOHNSON, C.R.: ‘Matrix analysis’ (Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, 1985)

23 SUGENO, M., and KANG, G.T.: ‘Fuzzy modeling and control of inultiplayer incinerator’, Fuzzy Sets SJU~., 1986, 18, (3), pp. 329- 346

24 SUGENO, M., and KANG, G.T.: ‘Fuzzy identification of fuzzy model’, 25 TAKAGI, T., and SUGENO, M.: ‘Fuzzy identification of svsteins and its

Fuzzy Sets Sy.sr., 1988, 28, (l), pp. 15-33

application to modeling and control’, ?EEE nUns. Sysf. hfan Cyberx.,

1985, 15, (I), pp. 116-132

26 TANAICA, K., and SUGENO, M.: ‘Stability analysis and design of fuzzy control systems’, Fnzzy Sets Syst., 1992, 45, (2), pp. 135-156 27 WANG, L.X.: ‘Stable adaptive fuzzy control of nonlinear systems’,

B E E k n s . FUZZJ) Syst., 1993, 1 , (2), pp. 146-155

28 CASTRO, J.L.: ‘Fuzzy logic controllers are universal approximators’,

IEEE Ttuns. S’wf. Man Cybern., 1995, 25, (4), pp. 629-635