©2010 Taipei Medical University

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

1. Introduction

Gingival recession is defined as a shift of the gingival

margin to a position apical to the level of the

cemento-enamel junction.

1Recession may be related to

inappro-priate tooth brushing or due to inflammatory destruction

of the periodontium. Root hypersensitivity, esthetic

pro-blem, and abrasion may accompany gingival recession

and spur patients to seek treatment. The main goal of

treatment is to augment the width and height of the

attached gingiva and create a harmonious soft tissue

appearance, as well as to obtain complete root coverage.

Various methodologies have been used to treat gingival

recession in the last decade, including many

mucogin-gival graft techniques,

2–6or combined with guided tissue

regeneration (GTR) procedures.

7The use of subepithelial connective tissue grafts (CTGs)

and coronally positioned flaps (CPFs) for root coverage

was developed by Langer and Langer,

8who reported

an increase of 2–6 mm of root coverage over 4 years. A

study selected paired defects and assessed the

poten-tial for root coverage with free gingival grafts (FGGs)

Background/Purpose: The objective of this meta-analysis was to assess and compare theeffectiveness of connective tissue graft (CTG) and guided tissue regeneration (GTR) in treating patients with gingival recessions of Miller‘s classification grades I and II.

Methods: Nineteen clinical studies that met prestated inclusion criteria were screened

from 250 initial articles for the systematic analysis of the clinical efficacies of CTG and GTR according to four clinical variables: recession depth reduction; clinical attachment gain; keratinized tissue gain; and probing depth reduction. The heterogeneity and weighted mean difference were calculated using a statistical package for meta-analysis.

Results: In the follow-up period shorter than 12 months, CTG resulted in more keratinized

tissue than GTR (p < 0.05). In the follow-up period of 12 months or longer, CTG resulted in significantly greater reduction in recession depth, more keratinized tissue gain, and less probing depth reduction than GTR (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: With regard to recession depth reduction and keratinized tissue gain in the

treatment of Miller’s class I or II gingival recession, CTG was statistically significantly more effective than GTR.

Received: Sep 15, 2009 Revised: Jan 6, 2010 Accepted: Feb 4, 2010

KEY WORDS: connective tissue graft; gingival recession; guided tissue regeneration; Miller’s classification; root coverage

Systematic Review of the Clinical Performance of

Connective Tissue Graft and Guided Tissue

Regeneration in the Treatment of Gingival Recessions

of Miller’s Classification Grades I and II

Hui-Yuan Ko

1

, Hsein-Kun Lu

1,2

*

1

Periodontal Clinics, Department of Dentistry, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

2College of Oral Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

*Corresponding author. College of Oral Medicine, Taipei Medical University, and Periodontal Clinics, Department of Dentistry, Taipei Medical University Hospital, 250 Wu-Hsing Street, Taipei 11042, Taiwan.

averaged 43% for FGGs and 80% for CTGs. Another

study also indicated that CTGs had an 85% success rate,

which was better than the 53% success rate with FGGs.

10Polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) was first used by

Tinti and Vincenzi to cover roots.

7In the early days,

non-bioabsorbable membranes such as Millipore filters

(Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and ePTFE were used in

the GTR technique; due to the inability to degrade, the

clinical applications were limited.

11The space-making

concept is used with bioresorbable membranes adjunct

to CPFs to avoid the need for a second surgical procedure

to remove non-resorbable membrane. Bioabsorbable

membranes are widely used nowadays, and include

such materials as collagen, polyglycolic acid, polylactic

acid, and polymers of the above-mentioned materials.

12A study comparing the use of ePTFE and polyglycolic

acid membranes for root coverage found no

statisti-cally significant differences in the mean root coverage

between these two materials.

13Comparisons of the use of GTR and CTG combined

with CPF to achieve complete root coverage are

con-troversial. Factors that can influence outcomes of CTG

and GTR when treating root coverage include the

pre-treatment recession depth, the type of surgical modality

used, histological features of the dentogingival

junc-tion after root coverage, root condijunc-tioning, type of GTR

material chosen, and other confounding factors, such

as smoking and bias caused by commercial interests.

Since different studies are carried out using

differ-ent populations, differdiffer-ent designs, and a wide range

of specific factors for each study, it was suggested that

combining them may produce an evaluation that has

broader ability to be generalized than any single study

by itself.

14The objective of this systematic review was

to assess the effectiveness of CTG and GTR in treating

patients with gingival recessions and to compare the

efficacy of CTG with GTR for root coverage. The study

procedures in our review process followed the PICO

format [which stands for patient (or disease),

interven-tion (a drug or test), comparison (another drug, placebo

or test), and outcome].

152. Material and Methods

2.1. Search strategy

The search was conducted using the Ovid MEDLINE

database, from 1950 to and including March 2009. No

hand searching was conducted. The search used the

following descriptors: gingival recession/therapy,

gin-gival recession/surgery, tooth root/surgery, guided

tis-sue regeneration, or connective tistis-sue/transplantation.

Afterwards, the operator “and” was used at the end of

the process to narrow the search and select articles that

contained all of the PICO terms.

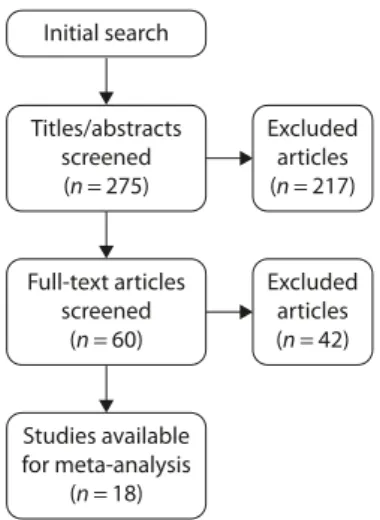

Initial search Titles/abstracts screened (n=275) Full-text articles screened (n=60) Studies available for meta-analysis (n=18) Excluded articles (n=217) Excluded articles (n=42)

references

To be eligible for inclusion in this review, studies had to

be human clinical trials conducted on patients with a

diagnosis of gingival recession of Miller’s classification

grade I or II, used CTG or GTR as the treatment

modali-ties for gingival recession, and have a follow-up period

of at least 6 months. All reviewed articles were confined

to journals published in English only. Exclusion criteria

for the root coverage procedures were studies that

in-cluded furcation-involved teeth, or that had subjects

who smoked, or that had follow-up periods shorter than

6 months, or the treated recessions were other than

Miller’s classification grade I or II.

2.3. Screening procedure

Titles and abstracts were initially screened for possible

inclusion by viewing them according to the following

criteria: they had to be human trials; they had to use

GTR or CTG for gingival recession treatment; and they

had to include clinical outcomes. Reports that clearly

did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded;

other-wise, the articles were included for a secondary review.

The full text of possibly relevant studies was then

sec-ondarily screened according to the inclusion criteria. Any

disagreement in the selection process was resolved by

discussion between two reviewers. The screening

proc-ess is illustrated in Figure 1, and the characteristics of

the 18 included studies are reported in Table 1.

13,16–32There were only three articles included for 12-month

follow-up for each CTG and GTR subgroup. Forty-two

articles were excluded; they are listed in Table 2 with

the reason for exclusion.

7,11,33–72The outcome measures

assessed were recession depth reduction, clinical

attach-ment gain, keratinized tissue gain, and probing depth

reduction.

T able 1 Charac te ristics of included ar ticles Ref e renc e Y ear Study description* Def e c ts P a rticipants In te rv entions Duration C o ntr ol Test Aichelmann-Reidy et al 16 2001 C o ntr

olled clinical trial

, split-mouth M iller ’s class I or II 22 ADM allog raf t C T G 6 mo Bor ghetti et al 17 1999 RC T, c omparativ e study , split-mouth M iller ’s class I 14 GTR with Guidor C T G 6 mo M a tri x barrier C aff esse et al 18 2000 RC T, c omparativ e study M iller ’s class I or II 36 C T

G (with citric acid f

or C T G 6 mo No pocket > 4 mm root demineralization) It o et al 19 2000 C omparativ e study M iller ’s class I or II 6 FGG GTR with ePTFE 6/12 mo P ocket depth ≥ 4 mm Jepsen et al 20 1998 RC T, c omparativ e study , split-mouth M iller ’s class I or II 15 GTR with ePTFE C T G 12 mo Lins et al 21 2003 RC T, split-mouth M iller ’s class I or II 10 CRF GTR with ePTFE + 6 mo P ocket depth ≥ 2 mm CRF M a tarasso et al 22 1998 RC T, c omparativ e study M iller ’s class I or II 20

GTR with PLA membrane

+ GTR + CRF 12 mo

double papilla flap

Müller et al 23 2001 C omparativ e study M iller ’s class I or II 22 GTR with PLA C T G 6/12 mo No vaes et al 24 2001 RC T, c omparativ e study , split-mouth M iller ’s class I or II 9 ADM allog raf t C T G + CPF 3/6 mo P aolant onio 25 2002 RC T, c omparativ e study , split-mouth M iller ’s class I or II 45

GTR with PLA membrane

C T G 12 mo CPR T Roc cuzz o et al 13 1996 RC T, c omparativ e study , split-mouth M iller ’s I or II 12 GTR with ePTFE GTR with Guidor 6 mo P ocket depth ≥ 4 mm Romag na-Genon 26 2001 RC T, c omparativ e study , split-mouth M iller ’s class I or II 21 GTR with c ollagen C T G 3/6 mo P ocket depth ≥ 3 mm membrane Ta tak is & T rombelli 27 2000 RC T, c omparativ e study M iller ’s class I or II 12 GTR with Guidor C T G 6 mo M a tri x barrier Tö züm & Dini 28 2003 Clinical trial M iller ’s class II 14 C T G 8 mo T rombelli et al 29 1998 C ase r epor t M iller ’s class I or II 6 GTR with Guidor 6 mo M a tri x barrier T rombelli et al 30 1998 Clinical trial , split-mouth M iller ’s class I or II 12 GTR with Resolut C T G 6 mo membrane W ang et al 31 2001 RC T, c omparativ e study , split-mouth M iller ’s class I or II 16 GTR with c ollagen C T G 6 mo P ocket depth ≥ 3 mm membrane Zahedi et al 32 1998 Clinical trial M iller ’s class I 15 GTR with c ollagen 2 yr *A cc o rding t o O vid MEDLINE. RC T = randomiz ed c o ntr

olled trial; ADM

=

ac

ellular dermal matri

x ; GTR = guided tissue r egeneration; C T G = c onnec tiv e tissue g raf t; FGG = fr ee g ing ival g raf t; ePTFE = e x tended polyt etrafluor oeth ylene; CRF = c o ronally r

epositioned flap; PLA

= polylac tic acid; CPR T = c ombined periodontal r egenerativ e tr eatment; CPF = c o

ronally positioned flap

2.4. Quantitative data synthesis

The analysis was conducted using COMPREHENSIVE

META-ANALYSIS version 1 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ,

USA, 1999). A weighted treatment effect was calculated

using Cochran’s test for heterogeneity, and the results

expressed as weighted mean differences with 95%

confidence interval. Intergroup discrepancies of

treat-ment outcomes were accessed by analysis of variance

(ANOVA). Statistical significance was accepted for p

val-ues

< 0.05. Although some intragroup variances reached

statistical significance, random-effect models do not

“adjust for”, “account for”, or “explain” heterogeneity.

Thus, fixed effects were used to interpret the estimates

in this study.

3. Results

The studies included in the meta-analysis were divided

into two aspects for data analysis according to the

fol-lowing period: in one group of studies, patients were

observed for

< 12 months; in the other group, patients

were followed-up for 12 months or longer.

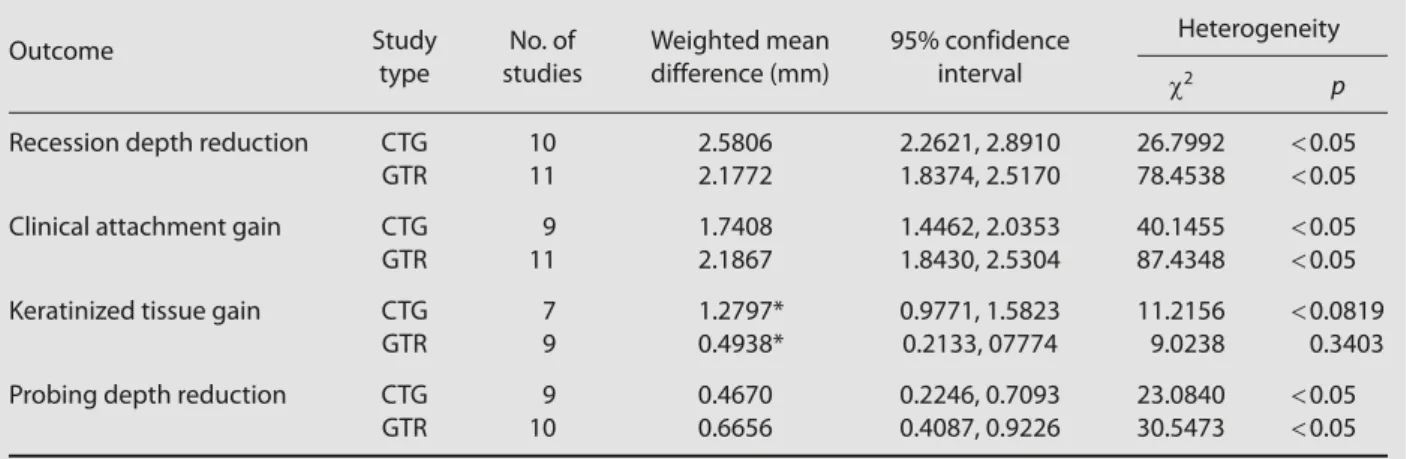

The weighted mean differences for CTG and GTR

between the baseline and post-treatment results, and

χ

2for heterogeneity of the outcomes of various

param-eters

< 12 months are presented in Table 3. The CTG

group showed significantly greater gain in keratinized

tissue compared to the GTR group when the follow-up

period of the included studies was

< 12 months (p < 0.05;

Figure 2).

13,16–19,21,24,27,29–31Table 2 List of full-text articles excluded

Reason for exclusion Study

Minimum of 6 months of follow-up Al-Zahrani et al (2004),33 Christgau et al (1995),34 Harris (1992),35 Harris (2001),36

data not presented Harris (2003)37

Smokers included Amarante et al (2000),38 Boltchi et al (2000),39 Cetiner et al (2003),40 Harris (1997),41

Harris (2000),42 Harris (2002),43 Harris (2002),44 Hirsch et al (2001),45 Jepsen et al

(2000),46 Leknes et al (2005),47 Müller et al (1998),48 Müller et al (1999),49

Silvestri et al (2003),50 Trombelli et al (2005)51

Treatment on recession other than Borghetti & Louise (1994),52 Harris (1997),53 Harris (1998),54 Harris (2002),55 Lee et al

Miller’s classification grade I or II (2002),56 Müller et al (2000),57 Pini Prato et al (1992),58 Pini Prato et al (1996),59

Tinti et al (1992),11 Trombelli et al (1994),60 Trombelli et al (1995),61 Waterman (1997),62

Weigel et al (1995),63 Wennström & Zucchelli (1996)64

CTG techniques other than Tözüm et al (2005),65 Dembowska & Drozdzik (2007)66

coronally positioned flap

Statistics unavailable Bouchard et al (1994),67 Ricci et al (1996),68 Rosetti et al (2000),69 Tinti & Vincenzi (1994),7

Trombelli et al (1995),70 Wang & Al-Shammari (2002),71 Zucchelli et al (2003)72 CTG = connective tissue graft.

Table 3 Comparison of connective tissue graft (CTG) and guided tissue regeneration (GTR) in studies with follow-up periods

< 12 months

Outcome Study No. of Weighted mean 95% confidence Heterogeneity type studies difference (mm) interval χ2 p

Recession depth reduction CTG 10 2.5806 2.2621, 2.8910 26.7992 < 0.05

GTR 11 2.1772 1.8374, 2.5170 78.4538 < 0.05 Clinical attachment gain CTG 9 1.7408 1.4462, 2.0353 40.1455 < 0.05

GTR 11 2.1867 1.8430, 2.5304 87.4348 < 0.05 Keratinized tissue gain CTG 7 1.2797* 0.9771, 1.5823 11.2156 < 0.0819

GTR 9 0.4938* 0.2133, 07774 9.0238 0.3403 Probing depth reduction CTG 9 0.4670 0.2246, 0.7093 23.0840 < 0.05

GTR 10 0.6656 0.4087, 0.9226 30.5473 < 0.05

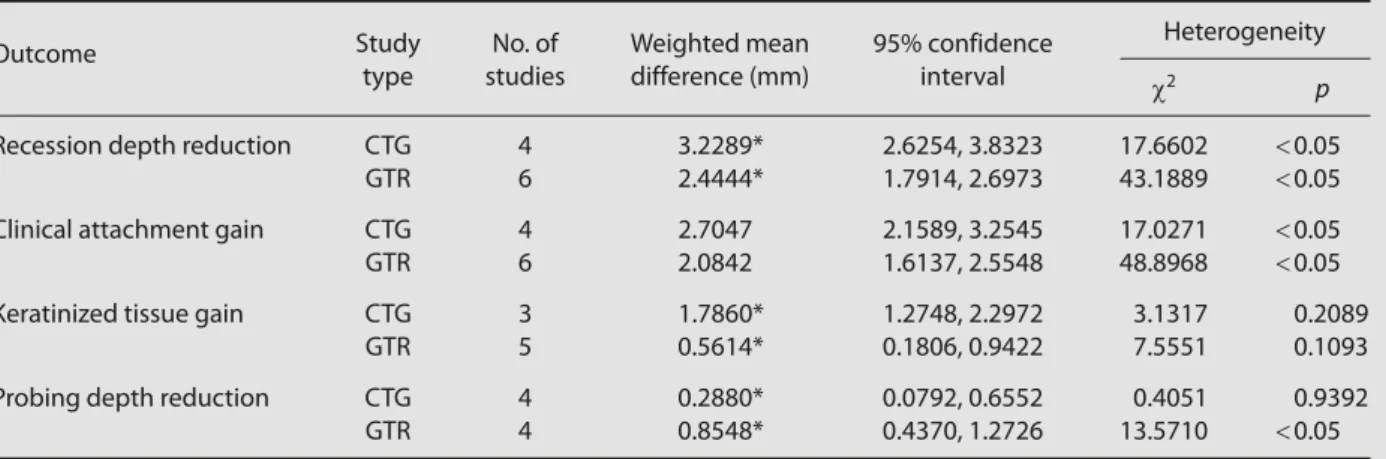

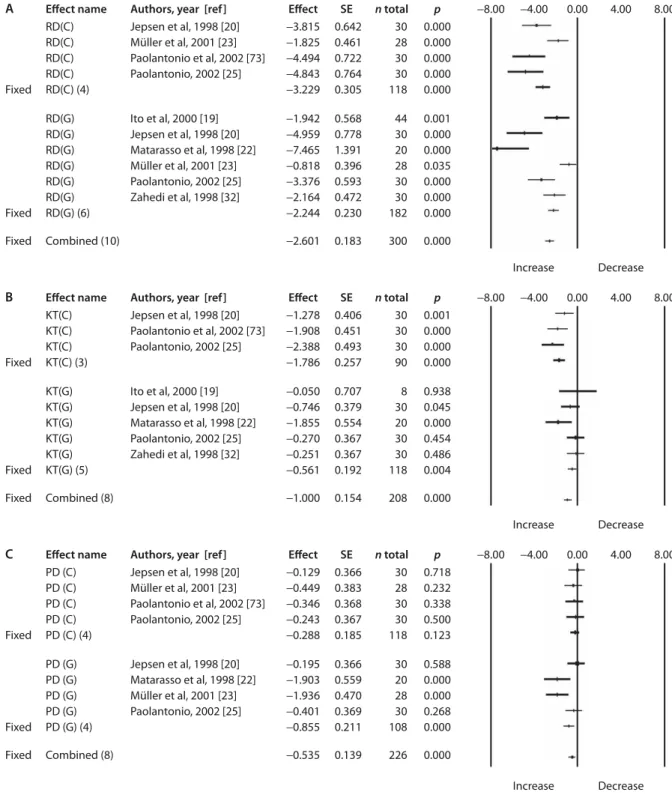

Table 4 delineates the significant weighted mean

differences in the categories of recession depth

reduc-tion (Figure 3A),

19,20,22,23,25,32,73keratinized tissue gain

(Figure 3B),

19,20,22,25,32,73and probing depth reduction

(Figure 3C)

20,22,23,25,73when comparing the results of

studies with CTG and GTR procedures followed-up for

≥ 12 months.

4. Discussion

In a systematic review that assessed the literature on a

variety of soft tissue augmentation procedures directed

at root coverage, the reviewers concluded that there

was greater gain in root coverage with CTG than with

GTR.

74In the study of Al-Hamdan et al, conventional

mucogingival surgery also resulted in statistically better

root coverage than did GTR.

75The results of this

analy-sis are in accordance with the above studies, i.e., that

CTG results in significantly greater reduction in recession

depth compared to GTR in studies followed-up for

≥ 12

months. However, comparing the intergroup results in

the present study, there was no significant difference

between the CTG and GTR groups in studies

followed-up for

< 12 months, although the CTG data implied a

slightly larger weighted mean difference in recession

Table 4 Comparison of connective tissue graft (CTG) and guided tissue regeneration (GTR) in studies with follow-up periods ≥

12 months

Outcome Study No. of Weighted mean 95% confidence Heterogeneity type studies difference (mm) interval χ2 p

Recession depth reduction CTG 4 3.2289* 2.6254, 3.8323 17.6602 < 0.05

GTR 6 2.4444* 1.7914, 2.6973 43.1889 < 0.05 Clinical attachment gain CTG 4 2.7047 2.1589, 3.2545 17.0271 < 0.05

GTR 6 2.0842 1.6137, 2.5548 48.8968 < 0.05 Keratinized tissue gain CTG 3 1.7860* 1.2748, 2.2972 3.1317 0.2089

GTR 5 0.5614* 0.1806, 0.9422 7.5551 0.1093 Probing depth reduction CTG 4 0.2880* 0.0792, 0.6552 0.4051 0.9392

GTR 4 0.8548* 0.4370, 1.2726 13.5710 < 0.05 *p < 0.05 between groups. Effect name Fixed Fixed Fixed KT(C) KT(C) KT(C) KT(C) KT(C) KT(C) KT(C) KT(C) (7) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) (9) Borghetti et al, 1999 [17] Ito et al, 2000 [19] Lins et al, 2003 [21] Roccuzzo et al, 1996 (GTRn) [13] Roccuzzo et al, 1996 (GTRr) [13] Tatakis & Trombelli, 2000 [27] Trombelli et al, 1998 [29] Trombelli et al, 1998 [30] Wang et al, 2001 [31]

Combined (16)

Authors, year [ref]

Aichelmann-Reidy et al, 2001 [16] Borghetti et al, 1999 [17] Caffesse et al, 2000 [18] Novaes et al, 2001 [24] Tatakis & Trombelli, 2000 [27] Trombelli et al, 1998 [30] Wang et al, 2001 [31] Effect −1.391 −1.784 −1.890 −1.018 −0.480 −2.041 −0.827 −1.280 −0.478 −0.123 −1.505 0.000 −0.460 −0.074 −0.300 −1.158 −0.561 −0.494 SE 0.339 0.457 0.421 0.391 0.415 0.520 0.370 0.154 n total 44 28 34 30 24 24 32 216 p −8.00 −4.00 0.00 4.00 8.00 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.008 0.236 0.000 0.023 0.000 −0.861 0.384 0.708 0.520 0.408 0.415 0.408 0.429 0.447 0.361 0.144 28 8 20 24 24 24 22 24 32 206 0.105 Increase Decrease 422 0.204 0.848 0.002 1.000 0.256 0.853 0.473 0.008 0.114 0.001 0.000

Figure 2 Comparative results of fixed effects for connective tissue graft (C) and guided tissue regeneration (G) for keratinized

tissue gain (KT) in studies with follow-up period < 12 months. SE = standard error; GTRn = guided tissue regeneration with non-resorbable membrane; GTRr = guided tissue regeneration with resorbable membrane.

depth reduction. We propose that creeping attachment

may be an important event in making the difference

with regard to the time frame of the relevant studies of

root coverage. According to a longitudinal study, 72.7%

of sites treated by CTG exhibited creeping attachment,

with an average increase of 0.55 mm of coverage.

Creep-ing attachment was highest at 12 months.

56At the

present time, there is no evidence that the method of

GTR using a membrane technique for root coverage

promotes creeping attachment 1 year after treatment.

The data in our analysis show limited but greater

gain in keratinized tissue width with CTG than with GTR

in both follow-up periods. This difference was also

evi-dent in the meta-analysis of some systematic studies

that favored CTG in terms of gains in keratinized tissue.

74CTG generally involves the grafting of connective tissue

Fixed RD(C) RD(C) RD(C) RD(C) RD(C) (4) Jepsen et al, 1998 [20] Müller et al, 2001 [23] Paolantonio et al, 2002 [73] Paolantonio, 2002 [25] −3.815 −1.825 −4.494 −4.843 −3.229 0.642 0.461 0.722 0.764 0.305 30 28 30 30 118 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 Fixed RD(G) RD(G) RD(G) RD(G) RD(G) RD(G) RD(G) (6) Fixed Combined (10) −2.601 0.183 300 0.000 Ito et al, 2000 [19] Jepsen et al, 1998 [20] Matarasso et al, 1998 [22] Müller et al, 2001 [23] Paolantonio, 2002 [25] Zahedi et al, 1998 [32] −1.942 −4.959 −7.465 −0.818 −3.376 −2.164 −2.244 0.568 0.778 1.391 0.396 0.593 0.472 0.230 44 30 20 28 30 30 182 0.001 0.000 0.000 0.035 0.000 0.000 0.000 Increase Decrease Fixed KT(C) KT(C) KT(C) KT(C) (3) Jepsen et al, 1998 [20] Paolantonio et al, 2002 [73] Paolantonio, 2002 [25] −1.278 −1.908 −2.388 −1.786 0.406 0.451 0.493 0.257 −8.00 −4.00 30 30 30 90 0.001 0.000 0.000 0.000 Fixed KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) KT(G) (5) Fixed Combined (8) −1.000 0.154 208 0.000 Ito et al, 2000 [19] Jepsen et al, 1998 [20] Matarasso et al, 1998 [22] Paolantonio, 2002 [25] Zahedi et al, 1998 [32] −0.050 −0.746 −1.855 −0.270 −0.251 −0.561 0.707 0.379 0.554 0.367 0.367 0.192 8 30 20 30 30 118 0.938 0.045 0.000 0.454 0.486 0.004 0.00 4.00 8.00 Increase Decrease Effect name Authors, year [ref] Effect SE n total pFixed PD (C) PD (C) PD (C) PD (C) PD (C) (4) Jepsen et al, 1998 [20] Müller et al, 2001 [23] Paolantonio et al, 2002 [73] Paolantonio, 2002 [25] −0.129 −0.449 −0.346 −0.243 −0.288 0.366 0.383 0.368 0.367 0.185 −8.00 −4.00 30 28 30 30 118 0.718 0.232 0.338 0.500 0.123 Fixed PD (G) PD (G) PD (G) PD (G) PD (G) (4) Fixed Combined (8) −0.535 0.139 226 0.000 Jepsen et al, 1998 [20] Matarasso et al, 1998 [22] Müller et al, 2001 [23] Paolantonio, 2002 [25] −0.195 −1.903 −1.936 −0.401 −0.855 0.366 0.559 0.470 0.369 0.211 30 20 28 30 108 0.588 0.000 0.000 0.268 0.000 0.00 4.00 8.00 Increase Decrease Effect name Authors, year [ref] Effect SE n total p

B

C

Figure 3 Forest plots presenting the fixed effects of connective tissue graft (C) and guided tissue regeneration (G) in: (A)

reduction of recession depth (RD); (B) keratinized tissue gain (KT); and (C) pocket depth reduction (PD) in studies with follow-up period ≥ 12 months. SE = standard error.

harvested from keratinized oral mucosa. Karring et al

proved that the clinical and structural features of

kerati-nized tissues are genetically controlled by the underlying

connective tissue rather than functionally determined

by mechanical factors.

76,77At least in part, the grafting

of CTGs may play a role in regulating the keratinization

of new oral epithelium at the recipient site.

A meta-analysis of GTR-based root coverage showed

that both conventional mucogingival surgery and GTR

can produce similar clinical attachment gains.

75No

dif-ferences were found in another study comparing gain

in attachment for GTR, FGGs, CTGs, and CPFs.

78Our

meta-analysis found that there was no significant weighted

mean difference between CTG and GTR in clinical

attach-ment gain.

Clinically, little information is available regarding the

nature of the histological interface between CTGs and

root surfaces. Most case reports present a long

junc-tional epithelium, true regeneration of the periodontal

unit, or unpredictable root resorption at the graft-root

surface interface.

79On the other hand, there are also

few histological reports derived from randomized

con-trolled trials of GTR-based root coverage. GTR-based

root coverage using collagen membranes in mongrel

dogs showed a statistically significant increase in new

attachment and newly formed connective tissue

com-pared to CPFs at 16 weeks.

80However, in one clinical

study with recession defects of four teeth treated with

GTR using polylactic acid, the root coverage obtained

was a long junctional epithelial attachment in three

defects. The results of that study showed no

regenera-tion in any of the four defects.

81In a split-mouth study

that focused on the biologic success of GTR and CTG

procedures for root coverage, no differences in terms

of biologic rehabilitation (including coverage height,

bone, cementum and connective tissue attachment

re-generation, length of the epithelium, resorption, and

ankylosis) between the recessions treated with ePTFE

membranes and those treated with CTG were found.

82Obviously, the final decision point that makes the

dif-ference in the interface between the root and grafting

materials for root coverage depends on the skill and

concept of the surgeon, the various methodologies, the

prerequisite for root conditioning, and even the

individ-ual variability of subjects who undergo the surgery.

In the present study, there was no difference in

the weighted mean comparison of recession depth

re-duction for both follow-up periods between GTR with

non-resorbable membranes and GTR with resorbable

membranes. The biocharacter of the membrane

mate-rials does not seem to cause any difference in the holding

of the recession margin of the gingiva and keratinized

tissue gain, but does cause a difference in clinical

attach-ment gain and probing depth reduction. We surmise

that in the majority of cases, the studies in both GTRn

and GTRr groups were conducted on single root teeth

with Miller’s classification grade I or II recession, and

which were deeply submerged beneath thick

mucope-riosteal flaps. The convex topographical characteristics

of root morphology, unlike the root trunk over

multi-ple root teeth, can ensure commulti-plete adaptation of the

membrane on root surfaces in both procedures.

835. Conclusion

When considering recession depth reduction and

kerat-inized tissue gain in treating gingival recessions of Miller’s

classification grade I or II, our systematic review

indi-cated that CTG was statistically significantly more

ef-fective than GTR with follow-up periods longer than

12 months.

References

1. Wennström JL. Mucogingival therapy. Ann Periodontol 1996;1: 671–701.

2. Caffesse RG, Guinard EA. Treatment of localized gingival recessions. Part IV. Results after three years. J Periodontol 1980;51:167–70. 3. Holbrook T, Ochsenbein C. Complete coverage of the denuded

root surface with a one-stage gingival graft. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1983;3:8–27.

4. Nelson SW. The subpedicle connective tissue graft. A bilaminar reconstructive procedure for the coverage of denuded root surfaces. J Periodontol 1987;58:95–102.

5. Allen EP, Miller PD Jr. Coronal positioning of existing gingiva: short term results in the treatment of shallow marginal tissue recession. J Periodontol 1989;60:316–9.

6. Harris RJ. The connective tissue with partial thickness double pedicle graft: the results of 100 consecutively-treated defects. J Periodontol 1994;65:448–61.

7. Tinti C, Vincenzi GP. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene titanium-reinforced membranes for regeneration of mucogingival reces-sion defects. A 12-case report. J Periodontol 1994;65:1088–94. 8. Langer B, Langer L. Subepithelial connective tissue graft technique

for root coverage. J Periodontol 1985;56:715–20.

9. Jahnke PV, Sandifer JB, Gher ME, Gray JL, Richardson AC. Thick free gingival and connective tissue autografts for root coverage. J Periodontol 1993;64:315–22.

10. Paolantonio M, di Murro C, Cattabriga A, Cattabriga M. Subpedicle connective tissue graft versus free gingival graft in the coverage of exposed root surfaces. A 5-year clinical study. J Clin Periodontol 1997;24:51–6.

11. Tinti C, Vincenzi G, Cortellini P, Pini Prato G, Clauser C. Guided tissue regeneration in the treatment of human facial recession. A 12-case report. J Periodontol 1992;63:554–60.

12. Hardwick RST, Sanchez R, Whitley N, Ambruster J. Membrane Design Criteria for Guided Bone Regeneration of the Alveolar Ridge. Chicago: Quintessence, 1994:101–36.

13. Roccuzzo M, Lungo M, Corrente G, Gandolfo S. Comparative study of a bioresorbable and a non-resorbable membrane in the treatment of human buccal gingival recessions. J Periodontol 1996;67:7–14.

14. Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR. An illustrated guide to the methods of meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract 2001;7:135–48. 15. Needleman IG. A guide to systematic reviews. J Clin Periodontol

2002;29(Suppl 3):6–9; discussion 37–8.

16. Aichelmann-Reidy ME, Yukna RA, Evans GH, Nasr HF, Mayer ET. Clinical evaluation of acellular allograft dermis for the treatment of human gingival recession. J Periodontol 2001;72:998–1005.

clinical study of a bioabsorbable membrane and subepithelial connective tissue graft in the treatment of human gingival recession. J Periodontol 1999;70:123–30.

18. Caffesse RG, De LaRosa M, Garza M, Munne-Travers A, Mondragon JC, Weltman R. Citric acid demineralization and subepithelial connective tissue grafts. J Periodontol 2000;71:568–72.

19. Ito K, Oshio K, Shiomi N, Murai S. A preliminary comparative study of the guided tissue regeneration and free gingival graft procedures for adjacent facial root coverage. Quintessence Int 2000;31:319–26.

20. Jepsen K, Heinz B, Halben JH, Jepsen S. Treatment of gingival recession with titanium reinforced barrier membranes versus connective tissue grafts. J Periodontol 1998;69:383–91.

21. Lins LH, de Lima AF, Sallum AW. Root coverage: comparison of coronally positioned flap with and without titanium-reinforced barrier membrane. J Periodontol 2003;74:168–74.

22. Matarasso S, Cafiero C, Coraggio F, Vaia E, de Paoli S. Guided tissue regeneration versus coronally repositioned flap in the treatment of recession with double papillae. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1998;18:444–53.

23. Müller HP, Stahl M, Eger T. Failure of root coverage of shallow gin-gival recessions employing GTR and a bioresorbable membrane. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2001;21:171–81.

24. Novaes AB Jr, Grisi DC, Molina GO, Souza SL, Taba M Jr, Grisi MF. Comparative 6-month clinical study of a subepithelial connective tissue graft and acellular dermal matrix graft for the treatment of gingival recession. J Periodontol 2001;72:1477–84.

25. Paolantonio M. Treatment of gingival recessions by combined periodontal regenerative technique, guided tissue regeneration, and subpedicle connective tissue graft. A comparative clinical study. J Periodontol 2002;73:53–62.

26. Romagna-Genon C. Comparative clinical study of guided tissue regeneration with a bioabsorbable bilayer collagen membrane and subepithelial connective tissue graft. J Periodontol 2001;72: 1258–64.

27. Tatakis DN, Trombelli L. Gingival recession treatment: guided tissue regeneration with bioabsorbable membrane versus connective tissue graft. J Periodontol 2000;71:299–307.

28. Tözüm TF, Dini FM. Treatment of adjacent gingival recessions with subepithelial connective tissue grafts and the modified tunnel technique. Quintessence Int 2003;34:7–13.

29. Trombelli L, Scabbia A, Tatakis DN, Checchi L, Calura G. Resorbable barrier and envelope flap surgery in the treatment of human gingival recession defects. Case reports. J Clin Periodontol 1998; 25:24–9.

30. Trombelli L, Scabbia A, Tatakis DN, Calura G. Subpedicle connective tissue graft versus guided tissue regeneration with bioabsorbable membrane in the treatment of human gingival recession defects. J Periodontol 1998;69:1271–7.

31. Wang HL, Bunyaratavej P, Labadie M, Shyr Y, MacNeil RL. Comparison of 2 clinical techniques for treatment of gingival recession. J Periodontol 2001;72:1301–11.

32. Zahedi S, Bozon C, Brunel G. A 2-year clinical evaluation of a diphenylphosphorylazide-cross-linked collagen membrane for the treatment of buccal gingival recession. J Periodontol 1998; 69:975–81.

33. Al-Zahrani MS, Bissada NF, Ficara AJ, Cole B. Effect of connective tissue graft orientation on root coverage and gingival augmen-tation. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2004;24:65–9. 34. Christgau M, Schmalz G, Reich E, Wenzel A. Clinical and

radio-graphical split-mouth-study on resorbable versus non-resorbable GTR-membranes. J Clin Periodontol 1995;22:306–15.

35. Harris RJ. The connective tissue and partial thickness double pedicle graft: a predictable method of obtaining root coverage. J Periodontol 1992;63:477–86.

36. Harris RJ. Clinical evaluation of 3 techniques to augment ke-ratinized tissue without root coverage. J Periodontol 2001;72: 932–8.

tive cases treated with subepithelial connective tissue grafts. J Periodontol 2003;74:703–8.

38. Amarante ES, Leknes KN, Skavland J, Lie T. Coronally positioned flap procedures with or without a bioabsorbable membrane in the treatment of human gingival recession. J Periodontol 2000; 71:989–98.

39. Boltchi FE, Allen EP, Hallmon WW. The use of a bioabsorbable barrier for regenerative management of marginal tissue reces-sion. I. Report of 100 consecutively treated teeth. J Periodontol 2000;71:1641–53.

40. Cetiner D, Parlar A, Balos K, Alpar R. Comparative clinical study of connective tissue graft and two types of bioabsorbable barriers in the treatment of localized gingival recessions. J Periodontol 2003;74:1196–205.

41. Harris RJ. A comparison of two techniques for obtaining a con-nective tissue graft from the palate. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1997;17:260–71.

42. Harris RJ. A comparative study of root coverage obtained with an acellular dermal matrix versus a connective tissue graft: results of 107 recession defects in 50 consecutively treated patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2000;20:51–9.

43. Harris RJ. Root coverage with connective tissue grafts: an evalua-tion of short- and long-term results. J Periodontol 2002;73:1054–9. 44. Harris RJ. Connective tissue grafts combined with either double

pedicle grafts or coronally positioned pedicle grafts: results of 266 consecutively treated defects in 200 patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2002;22:463–71.

45. Hirsch A, Attal U, Chai E, Goultschin J, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. Root coverage and pocket reduction as combined surgical procedures. J Periodontol 2001;72:1572–9.

46. Jepsen S, Heinz B, Kermanie MA, Jepsen K. Evaluation of a new bioabsorbable barrier for recession therapy: a feasibility study. J Periodontol 2000;71:1433–40.

47. Leknes KN, Amarante ES, Price DE, Boe OE, Skavland RJ, Lie T. Coronally positioned flap procedures with or without a biode-gradable membrane in the treatment of human gingival recession. A 6-year follow-up study. J Clin Periodontol 2005;32:518–29. 48. Müller HP, Eger T, Schorb A. Gingival dimensions after root

cov-erage with free connective tissue grafts. J Clin Periodontol 1998; 25:424–30.

49. Müller HP, Stahl M, Eger T. Root coverage employing an envelope technique or guided tissue regeneration with a bioabsorbable membrane. J Periodontol 1999;70:743–51.

50. Silvestri M, Sartori S, Rasperini G, Ricci G, Rota C, Cattaneo V. Comparison of infrabony defects treated with enamel matrix derivative versus guided tissue regeneration with a nonresorb-able membrane. J Clin Periodontol 2003;30:386–93.

51. Trombelli L, Minenna L, Farina R, Scabbia A. Guided tissue regen-eration in human gingival recessions. A 10-year follow-up study. J Clin Periodontol 2005;32:16–20.

52. Borghetti A, Louise F. Controlled clinical evaluation of the sub-pedicle connective tissue graft for the coverage of gingival recession. J Periodontol 1994;65:1107–12.

53. Harris RJ. A comparative study of root coverage obtained with guided tissue regeneration utilizing a bioabsorbable membrane versus the connective tissue with partial-thickness double pedicle graft. J Periodontol 1997;68:779–90.

54. Harris RJ. A comparison of 2 root coverage techniques: guided tissue regeneration with a bioabsorbable matrix style membrane versus a connective tissue graft combined with a coronally posi-tioned pedicle graft without vertical incisions. Results of a series of consecutive cases. J Periodontol 1998;69:1426–34.

55. Harris RJ. GTR for root coverage: a long-term follow-up. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2002;22:55–61.

56. Lee YM, Kim JY, Seol YJ, Lee YK, Ku Y, Rhyu IC, Han SB, et al. A 3-year longitudinal evaluation of subpedicle free connective tissue graft for gingival recession coverage. J Periodontol 2002; 73:1412–8.

57. Müller HP, Stahl M, Eger T. Dynamics of mucosal dimensions after root coverage with a bioresorbable membrane. J Clin Periodontol 2000;27:1–8.

58. Pini Prato G, Tinti C, Vincenzi G, Magnani C, Cortellini P, Clauser C. Guided tissue regeneration versus mucogingival surgery in the treatment of human buccal gingival recession. J Periodontol 1992;63:919–28.

59. Pini Prato G, Clauser C, Cortellini P, Tinti C, Vincenzi G, Pagliaro U. Guided tissue regeneration versus mucogingival surgery in the treatment of human buccal recessions. A 4-year follow-up study. J Periodontol 1996;67:1216–23.

60. Trombelli L, Schincaglia G, Checchi L, Calura G. Combined guided tissue regeneration, root conditioning, and fibrin-fibronectin system application in the treatment of gingival recession. A 15-case report. J Periodontol 1994;65:796–803.

61. Trombelli L, Schincaglia GP, Zangari F, Griselli A, Scabbia A, Calura G. Effects of tetracycline HCl conditioning and fibrin-fibronectin system application in the treatment of buccal gingival recession with guided tissue regeneration. J Periodontol 1995; 66:313–20.

62. Waterman CA. Guided tissue regeneration using a bioabsorbable membrane in the treatment of human buccal recession. A re-entry study. J Periodontol 1997;68:982–9.

63. Weigel C, Bragger U, Hammerle CH, Mombelli A, Lang NP. Maintenance of new attachment 1 and 4 years following guided tissue regeneration (GTR). J Clin Periodontol 1995;22:661–9. 64. Wennström JL, Zucchelli G. Increased gingival dimensions.

A significant factor for successful outcome of root coverage procedures? A 2-year prospective clinical study. J Clin Periodontol 1996;23:770–7.

65. Tözüm TF, Keceli HG, Guncu GN, Hatipoglu H, Sengun D. Treatment of gingival recession: comparison of two techniques of subepi-thelial connective tissue graft. J Periodontol 2005;76:1842–8. 66. Dembowska E, Drozdzik A. Subepithelial connective tissue graft

in the treatment of multiple gingival recession. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;104:e1–7.

67. Bouchard P, Etienne D, Ouhayoun JP, Nilveus R. Subepithelial connective tissue grafts in the treatment of gingival recessions. A comparative study of 2 procedures. J Periodontol 1994;65: 929–36.

68. Ricci G, Silvestri M, Tinti C, Rasperini G. A clinical/statistical com-parison between the subpedicle connective tissue graft method and the guided tissue regeneration technique in root coverage. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1996;16:538–45.

69. Rosetti EP, Marcantonio RA, Rossa C Jr, Chaves ES, Goissis G, Marcantonio E Jr. Treatment of gingival recession: comparative study between subepithelial connective tissue graft and guided tissue regeneration. J Periodontol 2000;71:1441–7.

70. Trombelli L, Schincaglia GP, Scapoli C, Calura G. Healing response of human buccal gingival recessions treated with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene membranes. A retrospective report. J Periodontol 1995;66:14–22.

71. Wang HL, Al-Shammari KF. Guided tissue regeneration-based root coverage utilizing collagen membranes: technique and case reports. Quintessence Int 2002;33:715–21.

72. Zucchelli G, Amore C, Sforzal NM, Montebugnoli L, De Sanctis M. Bilaminar techniques for the treatment of recession-type defects. A comparative clinical study. J Clin Periodontol 2003;30:862–70. 73. Paolantonio M, Dolci M, Esposito P, D’Archivio D, Lisanti L, Di

Luccio A, Perinetti G. Subpedicle acellular dermal matrix graft and autogenous connective tissue graft in the treatment of gin-gival recessions: a comparative 1-year clinical study. J Periodontol 2002;73:1299–307.

74. Oates TW, Robinson M, Gunsolley JC. Surgical therapies for the treatment of gingival recession. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol 2003;8:303–20.

75. Al-Hamdan K, Eber R, Sarment D, Kowalski C, Wang HL. Guided tis-sue regeneration-based root coverage: meta-analysis. J Periodontol 2003;74:1520–33.

76. Karring T, Loe H. The three-dimensional concept of the epithelium-connective tissue boundary of gingiva. Acta Odontol Scand 1970; 28:917–33.

77. Karring T, Lang NP, Loe H. The role of gingival connective tissue in determining epithelial differentiation. J Periodontal Res 1975; 10:1–11.

78. Roccuzzo M, Bunino M, Needleman I, Sanz M. Periodontal plastic surgery for treatment of localized gingival recessions: a system-atic review. J Clin Periodontol 2002;29 Suppl 3:178–96.

79. Carnio J, Camargo PM, Kenney EB. Root resorption associated with a subepithelial connective tissue graft for root coverage: clinical and histologic report of a case. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2003;23:391–8.

80. Lee EJ, Meraw SJ, Oh TJ, Giannobile WV, Wang HL. Comparative histologic analysis of coronally advanced flap with and without collagen membrane for root coverage. J Periodontol 2002;73: 779–88.

81. Harris RJ. Histologic evaluation of root coverage obtained with GTR in humans: a case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2001;21:240–51.

82. Weng D, Hurzeler MB, Quinones CR, Pechstadt B, Mota L, Caffesse RG. Healing patterns in recession defects treated with ePTFE membranes and with free connective tissue grafts. A histologic and histometric study in the beagle dog. J Clin Periodontol 1998; 25:238–45.

83. Lu HK. Topographical characteristics of root trunk length related to guided tissue regeneration. J Periodontol 1992;63:215–9.