Short code: PCN

Title: Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences ISSN: 1323-1316

Created by: nikichen Word version: 11.0

Email proofs to: d10040 @mail.cmuh.org.tw

Copyright: © 2013 The Authors. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2013 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

Volume: (Issue: if known)

Cover year: 2013 (Cover month: if known) Article no.: 12125

Article type: article (Regular Article)

Figures: 1; Tables: 3; Equations: 0; References: 26; Words: 2502; First Page: 000; Last Page: 000 Short title running head: Depression and acute coronary syndrome

Authors running head: Y - N . L in et al.

*Correspondence: Chia-Hung Kao, MD, Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Science and School of Medicine, College of Medicine, China Medical University, No. 2, Yuh-Der Road, Taichung 404, Taiwan. Email: d10040 @mail.cmuh.org.tw

Received 25 March 2013; revised 18 September 2013; accepted 21 September 2013.

Regular Article

Increased subsequent risk of acute coronary syndrome for

patients with depressive disorder: A nationwide

population-based retrospective cohort study

Yen-Nien Lin, MD,1 Cheng-Li Lin, MSc,2,3 Yen-Jung Chang, PhD,2,3 Chiao-Ling Peng, MSc,2,3 Fung-Chang Sung, PhD,2,3

Kuan-Cheng Chang, MD1 and Chia-Hung Kao, MD4,5*

1Division of CardiologyDivision of Cardiology, Department of Internal MedicineDepartment of Internal Medicine, 3Management Office for Health DataManagement Office for Health Data, 5Department ofDepartment of

Nuclear Medicine

Nuclear Medicine, PET CenterPET Center, China Medical University HospitalChina Medical University Hospital, 2Institute of Environmental HealthInstitute of Environmental Health, College College

of Public Health

of Public Health, 4Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical ScienceGraduate Institute of Clinical Medical Science and School of MedicineSchool of Medicine, College of MedicineCollege of Medicine,

China Medical University

China Medical University, TaichungTaichung, TaiwanTaiwan

Aim: The purpose of this study was to explore the possible association between subsequent acute coronary syndrome ( ACS ) risk and depressive disorder.

Methods: We used data from the N ational H ealth I nsurance system of T aiwan to address the research topic. The exposure cohort contained 10871 patients with new diagnoses of depressive disorders. Each patient was randomly frequency-matched for sex and age with four participants from the general population who did not have any ACS history before the index date (control group). Cox’s proportion hazard regression analyses were conducted to estimate the relation between depressive disorders and subsequent ACS risk.

Results: Among patients with depressive disorders, the overall risk for developing subsequent ACS was significantly higher than that of the control group (adjusted hazard ratio [ aHR ]: 1.88, 95% confidence interval: 1.63– 2.17). Further analysis revealed that the higher risk was observed in patients who were male, were of older age, or whose diagnosis was combined with other comorbidities.

Conclusions: The findings from this population-based retrospective cohort study suggest that depressive disorder is associated with an increased subsequent ACS risk.

Key words:

Key words: acute coronary syndrome, depressive disorder, population-based cohort study.

Depressive disorder is a psychiatric illness that afflicts a significant portion of the population in all countries, and is more common among Taiwanese people than what has been previously suggested.1,2 Numerous epidemiological studies have indicated that high

comorbidity exists between depression and coronary heart disease (CHD).3 The overall

relative risk for CHD among patients with depression was 1.64 in a meta-analysis, including

11 cohort studies.4 Following myocardial infarction, the emergence of clinical depression

indicated that depression is bidirectionally associated with a complicated pathophysiological

mechanism connected with ischemic CHD.5–7 Although depression may be associated with

CHD, previous findings of such association have been limited to small population studies, meta-analysis, and mechanism discussions. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is an acute life-threatening condition of CHD. According to the most comprehensive resource, the incidence

rates of ACS (per 100 000) is 208 in the USA8 and around 100 in Taiwan in 2008.9,10 Lower

BMI, reduced protein/fat in the diet, and variation in comorbidities in Eastern countries may result in this difference in incidence. Despite this difference, cardiovascular disease is the first leading cause of death in the USA and the second leading cause of death in Taiwan. Few studies have specifically examined the risk of ACS frequency among people with a depression diagnosis in the general population. Therefore, the objective of this national population-based study was to examine the risk of subsequent ACS among patients with depression in Taiwan within the following years.

Methods Data sources

This study used the reimbursement data of the universal National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan, which has registered all medical claims and has provided affordable healthcare for all the island’s residents in Taiwan since 1996. This insurance program provides health care to 99% of over 23 million residents in Taiwan and is contracted with 97% of the hospitals and clinics.11 The claims database includes comprehensive

information by the National Health Research Institute (NHRI). This subset data include claims data randomly sampled for 1 million insured people from the nationwide population-based database released by the NHRI until 2009. The details of this database have been

published previously.12,13 The diagnoses were coded using the ICD-9-CM. These datasets

were linked with scrambled identification to strengthen data security to protect people’s privacy. We confirm that all data was de-identified and analyzed anonymously. Disease diagnoses were made by qualified cardiologists and psychiatrists in Taiwan. These diagnoses are clearly listed at the medical reimbursement and claims and the medical reimbursement and discharge notes are scrutinized by strict peer review. Several Taiwan studies have

demonstrated the high accuracy and validity of the diagnoses in NHIRD.14–17 In addition, this

study was also approved by the Ethics Review Board at China Medical University (CMU-REC-101-012).

Study subjects and outcome measures

This study comprises of a study cohort and a comparison cohort. The study cohort contained all patients with depressive disorder aged 18 years or older. Patients with newly diagnosed depressive disorder in the period of 2000–2002 from both ambulatory care and inpatient care were included as the exposure cohort (ICD-9-CM codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4 and 311). The index date for the depressive disorder patients was the date of their first outpatient visit. Subjects with a history of acute coronary syndrome diagnosed (ICD-9-CM 410–411.1) before the index date or with missing information on age or sex were excluded. For the comparison cohort, we used a systematic random sampling method and selected four insured people without depressive disorder in the same period with frequency matched on age, sex and the year of index date. The follow-up person-years were estimated for each subject from the index date to the data of the subjects who were diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome, or who withdrew from the insurance system before the end of 2009.

Statistical analysis

The distributions of categorical sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities comprising sex, age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, stroke, cancer, and peripheral arterial occlusive diseases (PAOD) were compared between the depressive disorder cohort and the non-depressive disorder cohort, and the differences were examined

using the χ2-test. The follow-up person-years, was performing for incidence density and rate

ratio calculation examined by Poisson regression. Cox’s proportional hazard regressions were used to estimate the risk of developing ACS associated with ACS, adjusting for variables that

confidence interval (CI) were assessed in the model. All analyses were performed by SAS

(version 9.2 for Windows; SAS, Cary, NC, USA). We used a two-tailed P-value lower than

0.05 with the statistically adopted significance level. Results

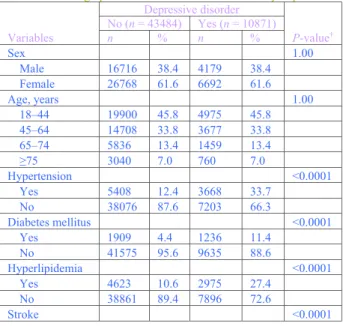

For the period 2000 to 2009, we identified 10 871 patients with depressive disorder as the exposure group and 43 484 subjects without depressive disorder as the control group. Among our subjects, 61.6% of them were women and 79.6% were younger than 65 years old (Table 1).

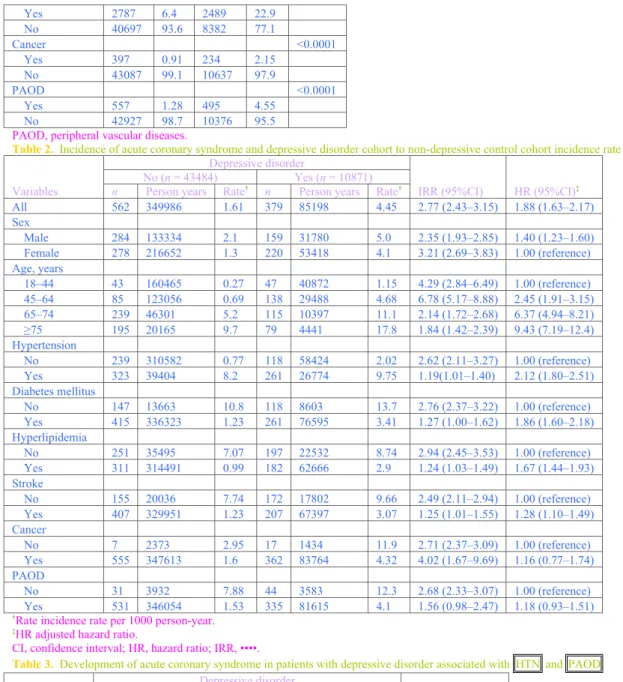

Compared with the non-depressive disorder cohort, patients were significantly more prevalent with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, stroke and peripheral vascular diseases. The overall incidence rate of ACS was 177% higher in the study cohort than in the comparison cohort (1.61 vs 4.45 per 1000 person-years incidence) with an adjusted HR of 1.88 (95%CI = 1.63–2.17) (Table 2). Sex-specific analysis shows the study cohort to comparison cohort rate ratio was higher for men than women, and there were 40% higher risks for men. Patients aged 45–64 years had the highest incidence (6.78 per 1000

person-years, 95%CI = 5.17–8.88) and risk of ACS increases with age. Additionally, Table 2 shows

the incidence of ACS measured by comorbidities status consistently lower in the comparison

cohort and higher risks of ACS estimated in the non-comorbidity group (Table 3).

A Kaplan–Meier graph of cumulative ACS incidence curve for depressive disorder patients and the comparison cohort is shown in Figure 1. The log–rank test indicates that patients with depressive disorder had significantly higher ACS survival rates (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Based on our research, this is the first nationwide population-based study to investigate specifically the risk of ACS among patients with depression. During a 10-year follow-up, 379 (4.45%) and 562 (1.61%) ACS episodes among depressed patients and non-depressed subjects, respectively, were documented. For adults older than 18 years, a diagnosis of depression was associated independently with a nearly 2.77-fold increased risk of ACS during 10 years of follow-up, after adjusting for comorbid medical disorders and sociodemographic characteristics. Women are at higher risk than men (HR 2.33 vs 3.21). The association persisted in further analyses stratified according to age, especially within the ages of 45–64 years (HR 6.78). Finally, as compared with the non-depressed cohort, a higher risk of ACS occurrence was observed among depressed patients without comorbid medical diseases except for cancer (HR 4.02). Depression may cause ACS through independent mechanisms other than common cardiovascular risk factors.

The results of our study are consistent with those of previous studies that have identified depression as a risk factor for CHD.4,18 In a meta-analysis, including 11 cohort studies,

depression was used to predict the development of CHD in initially healthy people with a

relative risk of 1.64. There might be a dose–response relation between depression and CHD.4

More recently, another meta-analysis of 28 studies with a total of 80 000 depressed patients

was conducted.18 This previous study discovered that patients with depression are associated

with a wide range of cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, and stroke (relative risk (RR) [95%CI] = 1.46 [1.37–1.55]). Although no previous studies have focused on ACS per se but on the association between depression and a more general condition, (i.e., CHD), our study added depression to the list of psychological conditions that have been associated with increased risk of ACS.

Previous studies have determined that frequency of depression in older adults was lower

compared to younger adults.19 However, risks of ACS and CHD were positively proportional

to increasing age. Patients with depression were observed to develop ACS and CHD during the period of 43–78 years of age.4,18 This wide age distribution can be attributed to the

variability of study designs. Our study enrolled a population over the age of 18 and the results suggested that ACS risk is higher within the age range of 45–64; regarding the younger group, the age-range was within 18–44 years. This finding correlates with relevant literature that identifies depression as psychological condition that promotes atherosclerosis.20

Bidirectional associations between depression and cardiovascular diseases have been extensively documented. The mechanisms by which cardiac risk is intensified in people with

depression remains to be elucidated; however, preliminary evidence suggests several

potential mechanisms.6,21–25 First, neuroendocrine and neurohumoral changes in depressed

people may lead to dysfunction of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. Second, patients with mood disorders tend to have autonomic and cardiovascular dysregulation, including an increased sympathetic drive, withdrawal of parasympathetic tone, cardiac rate and rhythm disturbances, and an altered baroreceptor reflex function. Their heart rate increases while the heart rate variability decreases, suggesting a possible link to ACS.22 Third, mental stress-induced ischemia is

related to significantly increased rates of later cardiac events.23 Negative emotional states can

activate pro-inflammatory cytokines, heighten platelet activation, and alter hemodynamic reactivity that contributes to the genesis of coronary atherosclerosis and triggers ACS.24

Fourth, patients with depression might engage in behavioral changes, including fatigue and physical inactivity, leading to further risk of CHD or ACS. Finally, antidepressants, especially tricyclics but not selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, might contribute to increased risk of myocardial infarction.6,25

This study has several limitations that merit attention. First, the data used in this study were retrieved from the NHIRD database and lacked specific social and personal information and drug histories. Therefore, we could not evaluate all other possible impacts, including smoking, body mass index, dietary habits, physical exercise, medication interaction, patients’ drug compliance, and treatment response. Second, we also could not obtain information about individual severity of depression. People with depression who never sought medical attention were overlooked. In addition, approximately one-quarter of myocardial infarctions are ‘silent’ and might also be overlooked in the claims. Third, although the full regression models were specified after adjusting for certain concurrent illnesses, the patients with depression could have been less healthy and could have had higher rates of comorbid medical problems that could affect their risk for ACS. Finally, the evidence derived from a cohort study is generally of lower methodological quality than that obtained from randomized trials, because a cohort study design is subject to many biases related to adjusting for confounders. Despite our meticulous study design involving adequate control of confounding factors, a key limitation was that bias could still remain because of possible unmeasured or unknown confounders. Nevertheless, apart from these potential problems, the data on depression and ACS diagnosis were highly reliable.

In clinical practice, both psychiatrists and cardiologists should respect the link between depression and ACS. For patients with depression, previous studies have suggested that β-blockers and antidepressants, other than tricyclics, should be added in prescriptions for

primary and secondary ACS prevention.6,22 In addition, there should be universal screening

and cardiovascular referral. Among patients with ACS-developed depression symptoms, initiation of depression therapy may improve the response to treatment for both depression and cardiovascular disease. However, depression screening, referrals, and treatment among patients with ACS are still controversial because of a lack of supportive randomized control trials or systematic evidence-based reviews.26

Conclusions

In conclusion, this national population-based retrospective cohort study proved a significant association between depression and subsequent ACS risk in Taiwan, especially in middle-aged patients with comorbid medical diseases. This finding is compatible with previous meta-analyses. Further study is required to extend this positive link to clinical purposes, thereby establishing treatment in prevention and evaluating the benefits of post-ACS depression screening and treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by study grants (DMR-102-014 and DMR-102-023) from our hospital, and from the Clinical Trial and Research Center of the Taiwanese Department of Health (DOH102-TD-B-111-004), as well as from Taiwan’s Department of Health Cancer Research Center for Excellence (DOH102-TD-C-111-005).

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial interest invested in this work, either collectively or individually.

References

1. Ustün TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJ. Global burden of

depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br. J. Psychiatry2004; 184: 386–392.

2. Chong MY, Tsang HY, Chen CS et al.Community study of depression in old age in

Taiwan: Prevalence, life events and socio-demographic correlates. Br. J. Psychiatry2001; 178: 29–35.

3. Halaris A. Comorbidity between depression and cardiovascular disease. Int. Angiol.2009;

28: 92–99.

4. Rugulies R. Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease. A review and

meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med.2002; 23: 51–61.

5. Lippi G, Montagnana M, Favaloro EJ, Franchini M. Mental depression and cardiovascular

disease: A multifaceted, bidirectional association. Semin. Thromb. Hemost.2009; 35: 325–

336.

6. Paz-Filho G, Licinio J, Wong ML. Pathophysiological basis of cardiovascular disease and

depression: A chicken-and-egg dilemma. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr.2010; 32: 181–191.

7. Plante GE. Depression and cardiovascular disease: A reciprocal relationship. Metabolism

2005; 54: 45–48.

8. Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med.2010; 362: 2155–

2165.

9. The comprehensive claims records of inpatient in the national health insurance database. Department of Health, Taiwan. 1996–2009. [Cited ••••.] Available from

http://www.bhp.doh.gov.tw/BHPNet/Web/Index/Index.aspx

10. Hsieh TH, Wang JD, Tsai LM. Improving in-hospital mortality in elderly patients after

acute coronary syndrome – a nationwide analysis of 97,220 patients in Taiwan during 2004– 2008. Int. J. Cardiol.2012; 155: 149–154.

11. Cheng TM. Taiwan’s national health insurance system: High value for the dollar. In:

Okma KGH, Crivelli L (eds). Six Countries, Six Reform Models: The Healthcare Reform,

Experience of Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan. World Scientific, Hackensack, NJ, 2009; 171–204.

12. Lai SW, Muo CH, Liao KF, Sung FC, Chen PC. Risk of acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes and risk reduction on anti-diabetic drugs: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am. J. Gastroenterol.2011; 106: 1697–1704.

13. Liang JA, Sun LM, Yeh JJ et al.Malignancies associated with systemic lupus

erythematosus in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Rheumatol. Int.2012; 32: 773–778.

14. Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, Lee CH, Lai ML. Validation of the National Health

Insurance Research Database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf.2011; 20: 236–242.

15. Chen YK, Hung TJ, Lin CC et al.Increased risk of acute coronary syndrome after spinal cord injury: A nationwide 10-year follow-up cohort study. Int. J. Cardiol.2013; ••••: ••••–

16. Chou IC, Lin HC, Lin CC, Sung FC, Kao CH. Tourette syndrome and risk of depression: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr.2013; 34: 181–185.

17. Liang JA, Sun LM, Muo CH, Sung FC, Chang SN, Kao CH. The analysis of depression

and subsequent cancer risk in Taiwan. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.2011; 20: 473–

475.

18. Van der Kooy K, vanHout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A.

Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: Systematic review and meta analysis.

Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry2007; 22: 613–626.

19. Blazer DG 2nd, Hybels CF. Origins of depression in later life. Psychol. Med.2005; 35:

1241–1252.

20. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, Saab PG, Kubzansky L. The epidemiology,

pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: The emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.2005; 45: 637–651.

21. Grippo AJ, Johnson AK. Stress, depression and cardiovascular dysregulation: A review of

neurobiological mechanisms and the integration of research from preclinical disease models.

Stress2009; 12: 1–21.

22. Taylor CB. Depression, heart rate related variables and cardiovascular disease. Int. J.

Psychophysiol.2010; 78: 80–88.

23. Jiang W, Babyak M, Krantz DS et al.Mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia and

cardiac events. JAMA1996; 275: 1651–1656.

24. Strike PC, Magid K, Whitehead DL, Brydon L, Bhattacharyya MR, Steptoe A.

Pathophysiological processes underlying emotional triggering of acute cardiac events. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A.2006; 103: 4322–4327.

25. Penttinen J, Valonen P. Use of psychotropic drugs and risk of myocardial infarction: A

case-control study in Finnish farmers. Int. J. Epidemiol.1996; 25: 760–762.

26. Davidson KW, Korin MR. Depression and cardiovascular disease: Selected findings,

controversies, and clinical implications from 2009. Cleve. Clin. J. Med.2010; 77 (Suppl. 3):

S20–S26.

Figure 1. Cummulative incidence of acute coronary syndrome in patients with and without depressive disorder. ••••, non-depressive

disorder; ••••, depressive disorder.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and co-morbidity in patients with and without depressive disorder

Variables Depressive disorder P-value† No (n = 43484) Yes (n = 10871) n % n % Sex 1.00 Male 16716 38.4 4179 38.4 Female 26768 61.6 6692 61.6 Age, years 1.00 18–44 19900 45.8 4975 45.8 45–64 14708 33.8 3677 33.8 65–74 5836 13.4 1459 13.4 ≥75 3040 7.0 760 7.0 Hypertension <0.0001 Yes 5408 12.4 3668 33.7 No 38076 87.6 7203 66.3 Diabetes mellitus <0.0001 Yes 1909 4.4 1236 11.4 No 41575 95.6 9635 88.6 Hyperlipidemia <0.0001 Yes 4623 10.6 2975 27.4 No 38861 89.4 7896 72.6 Stroke <0.0001

Yes 2787 6.4 2489 22.9 No 40697 93.6 8382 77.1 Cancer <0.0001 Yes 397 0.91 234 2.15 No 43087 99.1 10637 97.9 PAOD <0.0001 Yes 557 1.28 495 4.55 No 42927 98.7 10376 95.5

PAOD, peripheral vascular diseases.

Table 2. Incidence of acute coronary syndrome and depressive disorder cohort to non-depressive control cohort incidence rate ratio

Variables

Depressive disorder

IRR (95%CI) HR (95%CI)‡ No (n = 43484) Yes (n = 10871)

n Person years Rate† n Person years Rate†

All 562 349986 1.61 379 85198 4.45 2.77 (2.43–3.15) 1.88 (1.63–2.17) Sex Male 284 133334 2.1 159 31780 5.0 2.35 (1.93–2.85) 1.40 (1.23–1.60) Female 278 216652 1.3 220 53418 4.1 3.21 (2.69–3.83) 1.00 (reference) Age, years 18–44 43 160465 0.27 47 40872 1.15 4.29 (2.84–6.49) 1.00 (reference) 45–64 85 123056 0.69 138 29488 4.68 6.78 (5.17–8.88) 2.45 (1.91–3.15) 65–74 239 46301 5.2 115 10397 11.1 2.14 (1.72–2.68) 6.37 (4.94–8.21) ≥75 195 20165 9.7 79 4441 17.8 1.84 (1.42–2.39) 9.43 (7.19–12.4) Hypertension No 239 310582 0.77 118 58424 2.02 2.62 (2.11–3.27) 1.00 (reference) Yes 323 39404 8.2 261 26774 9.75 1.19(1.01–1.40) 2.12 (1.80–2.51) Diabetes mellitus No 147 13663 10.8 118 8603 13.7 2.76 (2.37–3.22) 1.00 (reference) Yes 415 336323 1.23 261 76595 3.41 1.27 (1.00–1.62) 1.86 (1.60–2.18) Hyperlipidemia No 251 35495 7.07 197 22532 8.74 2.94 (2.45–3.53) 1.00 (reference) Yes 311 314491 0.99 182 62666 2.9 1.24 (1.03–1.49) 1.67 (1.44–1.93) Stroke No 155 20036 7.74 172 17802 9.66 2.49 (2.11–2.94) 1.00 (reference) Yes 407 329951 1.23 207 67397 3.07 1.25 (1.01–1.55) 1.28 (1.10–1.49) Cancer No 7 2373 2.95 17 1434 11.9 2.71 (2.37–3.09) 1.00 (reference) Yes 555 347613 1.6 362 83764 4.32 4.02 (1.67–9.69) 1.16 (0.77–1.74) PAOD No 31 3932 7.88 44 3583 12.3 2.68 (2.33–3.07) 1.00 (reference) Yes 531 346054 1.53 335 81615 4.1 1.56 (0.98–2.47) 1.18 (0.93–1.51)

†Rate incidence rate per 1000 person-year. ‡HR adjusted hazard ratio.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IRR, ••••.

Table 3. Development of acute coronary syndrome in patients with depressive disorder associated with HTN and PAOD

Comorbidity

Depressive disorder

HR (95%CI)‡ No (n = 25048) Yes (n = 6262)

HTN PAOD n Person years Rate† n Person years Rate†

No No 237 309042 0.77 113 57668 1.96 1.00 (reference)

Yes No 318 38571 8.24 249 26096 9.54 2.41 (2.06–2.82)

No Yes 2 1540 1.30 5 756 6.61 1.54 (0.82–2.89)

Yes Yes 5 833 6.00 12 678 17.71 3.02 (2.28–4.02)

†Incidence rate per 1000 person years.

Multivariable analysis including age, sex, and comorbidity retrospective cohort study. CI, confidence interval; HTN, hypertension; PAOD, peripheral vascular diseases.