資本稅及環境政策之政治經濟分析 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 謝辭 首先感謝指導教授賴育邦博士。老師平時詼諧幽默,但對研究具有犀利見解, 每次和老師討論後都覺得輕舟已過萬重山,讓我在研究進度碰壁時,總是帶著愧 疚的心情前往老師研究室,再懷著雀躍的心情離開。 感謝口試委員吳文傑教授、何怡澄教授、張文俊教授及蘇建榮教授,在百忙 中抽空審閱論文,斧正疏漏令論文更臻完整,並給予我未來生涯規劃更多鼓勵。 感謝揚仁和勢璋在同學過程中互相打氣,並猶如浮木般提供我救命的幫助,讓我 能順利闖過每個關卡。感謝允許我在公餘進修的財政部 曾政務次長銘宗及六年 以來提攜容忍的各位長官,也感謝一路以來提供許多支援的同事,沒有您們的支. 治 政 持與寬容,我就無法完成這個夢想。感謝娘家與夫家給我最多的空間和關懷,家 大 立 裡的傻貓們和小狗天使仔仔總是帶給我最輕鬆滿足的悠閒時光,讓我能心無旁鶩 ‧ 國. 學. 繼續鴕鳥般過著單純的學生生活。最後當然要謝謝朱輔導長每每在我呼喚時現身 救援,給我力量也帶給我最多笑聲,這場奇幻冒險是你帶領我完成的。謹將此論. ‧. 文獻給你們和在天上的爸爸。. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi U. v ni. 鄭竹君 2013 年 7 月.

(3) 摘要 忽略政治干預將導致政策設計失當。本篇論文試圖強調在政策制定過程當中 政治力量扭曲之重要性。我們發展 3 個包含不同政治經濟學議題的模型,例如利 益團體與談判,以闡明其對資本稅或環境政策之影響。更明確來說,第 2 章我們 說明當存在遊說行為時,嚴格的查緝政策(提高查緝率或罰則)可能導致汙染排放 量增加,而使社會福利惡化,而當污染廠商擁有相對高的政治影響力時尤然。第 3 章我們發現,若廠商可透過遊說行為影響租稅政策,不論是單一國家放寬對國 際租稅規劃之法令限制,或全球共同合作打擊租稅天堂,均無法保證福利改善。. 政 治 大 汙染與不同交易機制對於汙染結果之影響。本篇論文主要發現為強調政治因素在 立 第 4 章則發現,國際排汙權交易制度並不一定能降低全球汙染量。我們強調跨國. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 政策制定最終結果中扮演重要角色。. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(4) Abstract Neglecting political intervention would lead to inadequate designs of policies. In this dissertation we attempt to emphasize the importance of the distortion from political power in a policy making process. We develop three frameworks that incorporate different political economics issues such as interest groups and bargaining in order to shed light on the their influence upon the outcomes of a capital tax or environmental policy. More specifically, in Chapter II we demonstrate that in the presence of lobbying, a stricter enforcement policy (an increase in the probability of. 政 治 大 reduce social welfare, in particular when the polluting firms have a relatively large 立 detection or the penalty) can bring about a larger amount of pollution emissions and. political influence. In Chapter III we find that, if the firm can influence tax policies. ‧ 國. 學. through lobbying, neither unilateral relaxation of the regulation of international tax. ‧. planning nor global cooperation to depress the utilization of tax havens can guarantee. sit. y. Nat. welfare enhancement. In Chapter IV, it is shown that international emissions trading. io. er. may not necessarily result in less global pollution. We highlight the roles played by the transboundary pollution and different trading schemes in the emission outcomes.. al. n. v i n C h contribute to the The main findings of this dissertation literature by highlighting the engchi U important role of political factors in the final results of policy making..

(5) Contents ___________________________________________________________ Chapter I :. Introduction. Chapter II :. Does a stricter enforcement policy protect the environment?. 1. A political economy perspective 2.1. Introduction 2.2. The model 2.3. The political equilibrium. 4 4 7 10. 2.4. The effects of enforcement policy 2.5. Concluding remarks Appendix Chapter III :. 15 21 22. 政 治 大. A political economy of tax havens 3.1. Introduction 3.2. The model 3.3. Political equilibrium 3.4. Effects of International Tax Planning. 24 24 26 31 32. 3.5. Welfare implications 3.6. Worker’s lobbying 3.7 Conclusion Appendix. 33 38 39 40. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. Reference. v. International emission trading with permit bargaining and. Ch. partial transboundary pollution 4.1. Introduction 4.2. The model 4.3. Total emissions and. Chapter V :. sit er. io. al. y. Nat Chapter IV :. engchi. i n U. 43 43 45. the nature of transboundary pollution 4.4. Efficiency and bargaining power neutral 4.5. Nonlinear damage function of emissions 4.6 Concluding remarks Appendix. 50 53 54 57 58. Conclusions. 61 64.

(6) Chapter I Introduction The issue of how political activities shape the final policies outcomes has been receiving increasing attention in both the economics and political science literature. For example, Lyon and Maxwell (2003) and Heyes and Maxwell (2004) show that beneficial environmental policies can have perverse effects in a political economic setting. Lai (2010) show that in the presence of capital market integration and interest group lobbying, decentralized policymaking can be more efficient than centralized. 政 治 大 distortion from political power 立 in a policy making process. Specifically, we develop. policymaking. In this dissertation we attempt to emphasize the importance of the. ‧ 國. 學. three frameworks that incorporate different political economics issues such as interest groups and bargaining in order to shed light on the their influence upon the outcomes. ‧. of a capital tax or environmental policy.. sit. y. Nat. In Chapter II, we extend the imperfect compliance model of Sandmo (2002) by. n. al. er. io. introducing interest groups. The firms in a polluting sector have incentives to. i n U. v. under-report their net emissions. A random inspection and penalties are available to. Ch. engchi. deter non-compliance. Two groups, namely, the shareholders of the polluting firms and environmentalists, engage in lobbying. Each lobbying group offers political contributions to the policymaker in order to influence the setting of the emission tax rate. In this setting, we show that a stricter enforcement policy can reduce social welfare. In the case where the polluting firms have a relatively large political influence, the equilibrium emission tax rate is lower than the tax rate that maximizes social welfare. In this case, tightening the enforcement policy reduces the emission tax as indicated above, and causes the emission tax rate to deviate further away from 1.

(7) the optimal level. In Chapter III, we construct a standard tax competition model incorporating tax havens and interest groups. There are a large number of (non-haven) countries that compete for mobile capital by setting their capital taxes. There are two types of capital, mobile and immobile. Each country levies a uniform tax on the two types of capital. The tax revenues are distributed to poor residents (pensioners). In addition to the non-haven countries, there also exist some jurisdictions that are referred to as tax havens that levy no tax and provide firms with opportunities to reduce tax burdens on. 政 治 大 to organize themselves into a lobbying group, and they offer political contributions to 立 mobile capital through international tax planning. The owners of capital are assumed. their policymaker in order to influence the capital tax rate.. ‧ 國. 學. Within this framework, we examine how the international tax planning activity. ‧. affects the capital tax rates, and the social welfare of the non-haven countries. A major. sit. y. Nat. finding is that a non-haven country’s social welfare can decrease with the extent of. io. er. international tax planning, in particular when the policymaker attaches a large weight to political contributions. It is argued that international tax planning activity provides. al. n. v i n C h to meet the optimal a desirable differential tax treatment taxation rule, requiring engchi U. different tax rates imposed on the mobile capital and the immobile capital, and thus enhances efficiency. However, in addition to the efficiency consideration, there arises a political effect when consider the lobby activity of interest groups. This political effect drives the already sub-optimally low tax rate further below the efficient level, and thus leads to a lower level of social welfare. If the political effect outweighs the enhancement in welfare due to differential tax treatment, then a larger extent of tax planning reduces the social welfare. Another finding is that the international cooperation on reducing the tax planning activity can reduce the non-haven countries’ welfare. The intuition lies in that the cooperation on reducing international tax 2.

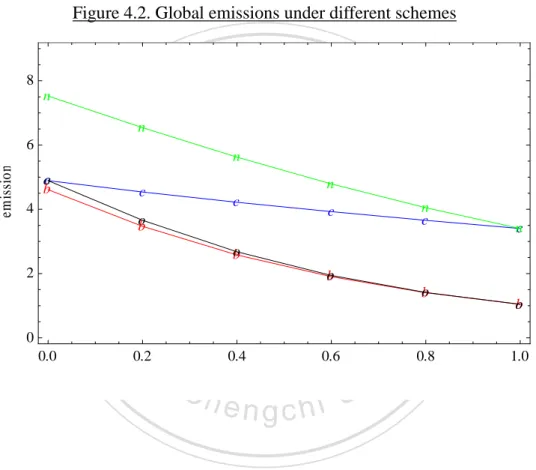

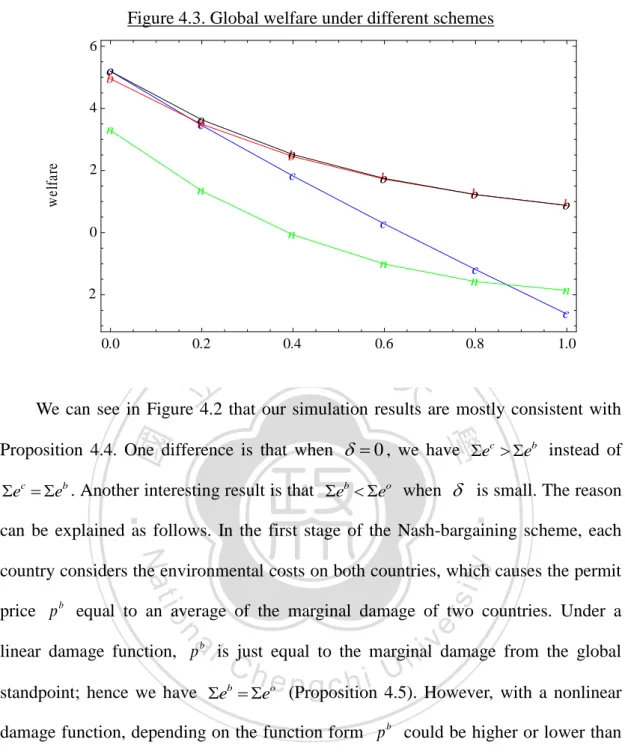

(8) planning activity can cause the sub-optimally low tax rate to deviate further below the efficient level, and thus reduce all non-haven countries’ social welfare. In Chapter IV, we establish an international emissions trading (IET) model, by which we deal with the issue of the pollution spillover effect and different permit trading schemes. In the first scheme, namely the non-cooperative trading scheme, countries choose the tradable allowances independently to maximize their welfare. The second scheme is the Nash-bargaining trading scheme, in which countries negotiate for the permit allowances via a Nash-bargaining process.. 政 治 大 efficient than the non-cooperative trading scheme, since the former endogenizes the 立. Our analysis shows that generally the Nash-bargaining trading scheme is more. environmental damage on the other country. Hence, member states with more. ‧ 國. 學. political influence in the IET group might choose their preferred trading designs on. ‧. purpose and in turn affect the effectiveness of IET model. The aggregate welfare after. sit. y. Nat. adopting an IET model might even worse than that without trade. Another interesting. io. er. finding is that a lower pollution spillover effect results in a higher after-trade aggregate emissions. It is because when countries determine the tradable emission. al. n. v i n allowances, some portion of theC allowances are expected h e n g c h i U to be sold and then pollute in. the neighboring country. This portion will then harm the welfare of the host country according to the spillover effect of pollution. When the international pollution spillover effect is larger, the country anticipates more environmental costs from a raise in permit allowances so that it will prefer a lower amount of allowance. This increases the equilibrium permit price and therefore reduces total emissions. Moreover, we rank the magnitudes of global emissions under different trading schemes and find that the results are related to the spillover effect of transboundary pollution. Finally, the main results of each chapter are summarized in Chapter V.. 3.

(9) Chapter II Does a stricter enforcement policy protect the environment? A political economy perspective 2.1 Introduction Enforcement policy is important in designing a regulatory regime and has been widely studied (Heyes, 2000). Neglecting enforcement policy or assuming full compliance would lead to inadequate designs of policies. In his seminal paper, Becker (1968) indicates that an increase in the expected penalties can enhance compliance with a law. 政 治 大. or regulation. However, by incorporating self-reporting and applying this to. 立. environmental regulation, Harford (1978, 1987) finds that, under certain conditions,. ‧ 國. 學. actual emissions and outputs are independent of the enforcement policy (also see Sandmo (2002)), and thus the enforcement policy has no real effect. This result is. ‧. based on the assumption that polluters are unable to influence the stringency of. y. Nat. io. sit. environmental regulation. As indicated by Weck-Hannemann (2008), the interference. n. al. er. of special interest groups appears inevitable in the process of formulating. i n U. v. environmental policy. Thus, it seems necessary to incorporate lobbying into the model. Ch. engchi. when an enforcement policy is evaluated.. If interest groups can influence the stringency of environmental regulation, then a natural question arises: Does the enforcement policy alter polluters’ decisions on pollution abatement or not? If the answer is affirmative, then what is the relationship between the enforcement policy and the actual pollution emissions? What is the enforcement policy that can maximize the social welfare in the presence of lobbying? We aim to address these questions. To this end, we construct an imperfect compliance model close to that of Sandmo (2002). The firms in a polluting sector have incentives to under-report their net 4.

(10) emissions. A random inspection and penalties are available to deter non-compliance. What deviates from the model of Sandmo (2002) is that we take the influence of lobbying groups into consideration. Two groups, namely, the shareholders of the polluting firms and environmentalists, engage in lobbying. Each lobbying group offers political contributions to the policymaker in order to influence the setting of the emission tax rate. The enforcement policy is assumed to be determined by other divisions of the government,1 e.g., bureaucrats, and to not be subject to the influence of lobbies. This. 政 治 大 enforcement policy on the stringency of pollution regulation. Our results can provide 立. setting enables us to investigate the effects of an exogenous change in the. policy guidance to a benevolent politician, say, a President, who faces a congress. ‧ 國. 學. plagued by interest groups. Supposing the tax rate is mainly determined by the. ‧. congress, and that the only instrument available to the benevolent politician is the. io. er. the question we wish to address.2. sit. y. Nat. enforcement regime, what then should he do to maximize the social welfare? This is. Within this setting, we find that, in the presence of lobbying, the actual net. al. n. v i n Ch emissions do change with the enforcement policy. A somewhat surprising result is that engchi U. a stricter enforcement policy (an increase in the probability of detection or the penalty) can bring about a larger amount of pollution emissions, in particular when the polluting firms have a relatively large political influence. This finding is different from the conventional wisdom or the result in Harford (1978, 1987) and Sandmo (2002). The intuition underlying this result is that a stricter enforcement policy 1. In reality, auditing policy and environmental tax rates are often governed by different authorities. For example, in the United States, audit targets are set by the Environmental Protection Agency in its annual performance plan, while the environmental tax rates are periodically adjusted by the Congress. 2 We acknowledge that enforcement can be subject to the influence of interest groups in some cases. There is much empirical evidence in support of have this result. For example, enforcement can depend on factors such as unemployment rates (Deily and Gray, 1991), or a firm’s prior environmental record (Innes and Sam, 2008). However, endogenizing both the emission tax rate and the enforcement policy leads to a pure positive model, which is unable to address our major question. 5.

(11) increases the polluting firms’ expected financial burden, and thus they will exert greater political pressure to reduce the emission tax rate, leading to more pollution emissions. Moreover, we also show that a stricter enforcement policy can reduce social welfare. In the case where the polluting firms have a relatively large political influence, the equilibrium emission tax rate is lower than the tax rate that maximizes social welfare. In this case, tightening the enforcement policy reduces the emission tax as indicated above, and causes the emission tax rate to deviate further away from. 政 治 大 possibility that policymaking will be misguided due to overlooking the political effect 立 the optimal level. The contribution of this present chapter is that it demonstrates the. of enforcement policy.. ‧ 國. 學. Several recent studies show that enforcement policies do affect actual emissions. ‧. (Macho-Stadler and Pérez-Castrillo, 2006; Macho-Stadler, 2008; Shiota, 2008), but all. sit. y. Nat. of them ignore the political effect arising from lobbying. A number of papers have. io. er. investigated the effects of institutional changes on the stringency of environmental regulation in the settings with lobbying, including Fredriksson (1997, 1999), Bommer. al. n. v i n C het al. (2003), among and Schulze (1999), and Damania others. These papers assume engchi U the full compliance of polluting firms, and ignore the role played by enforcement policy, which is our major concern. Another strand of the related literature, including Greenberg (1984), Harrington (1988), Kambhu (1989), Andreoni (1991), Nowell and Shogren (1994), Heyes (1996, 2002), and Raymond (2004), argues that setting penalties below the maximal level can improve environmental quality. Although this present chapter obtains a similar result, it departs from the above studies in two ways. First, some of them adopt dynamic frameworks that contain multiple periods, whereas our setting is essentially a static model. This shows that the perverse outcome arising from a seemingly 6.

(12) beneficial enforcement policy occurs not only in a complicated dynamic framework, but that it can also take place in a simple static model with lobbying. Secondly, none of these studies takes the facet of political economy into consideration. In addition, Lyon and Maxwell (2003) and Heyes and Maxwell (2004) also show that beneficial environmental policies can have perverse effects in a political economic setting. They make this point in connection with public voluntary programs and ecolabeling programs, respectively. This present chapter differs from theirs by focusing on enforcement policy.. 政 治 大 polluting sector’s production and declaration decisions in the benchmark case. In 立. The remainder of this chapter proceeds as follows. In Section 2.2, we discuss the. Section 2.3 we investigate the political equilibrium environmental policy. We explore. ‧ 國. 學. the various effects of stricter enforcement policies in Section 2.4. The concluding. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.2 The model. ‧. remarks are presented in Section 2.5.. We establish a model similar to that of Sandmo (2002). A small open economy. al. n. v i n C his a price taker inUthe world market. Firms in the contains a polluting industry, which engchi. polluting industry are identical,3 and we normalize the number of the firms in the industry as unity. Each firm employs a variable input x and a fixed input to produce output. Without loss of generality, we assume that the owners of firms possess the fixed input. The use of x generates pollutants. By appropriately choosing the unit of pollutant, each unit of x used generates one unit of pollutant. The objective function of a representative firm (without considering the 3. This assumption is mainly for simplification. It is assumed that heterogeneous firms does not qualitatively alter the results, provided that owners of firms cooperate in lobbying, which is a usual assumption made by the common-agency model. If they cannot cooperate, then firms with cost advantages may lobby for a stringent policy to expel opponents. See, e.g., Michaelis (1994) on this issue. 7.

(13) enforcement policy) or the rent of the fixed input is given by:. f ( x) cx A(a) t ( x a) ,. (2.1). where f (x) is the production function,4 with the properties f 0 and f 0 . The world and domestic price of the output is equal to unity, and c is the purchase price of x , which is exogenously determined.. The variable a stands for the. abatement amount of pollution emissions, and A(a) is the abatement cost function, with the properties A 0 and A 0 . The net pollution emissions, which are denoted by e, equal x a . The government imposes a tax on the net emissions at the rate t . The firms in the. 政 治 大 polluting industry are required 立. to self-report their net. emissions.5 The amount of the reported emissions of a representative firm is y. The. ‧ 國. 學. government employs a system of random detections to monitor the firms’ pollution. ‧. emissions. We assume that once the inspection is carried out, the government will. y. Nat. discover the true amount of emissions.. er. io. sit. The probability that an inspection is carried out is , which is greater than zero and less than unity.6 The emission tax is imposed on each firm’s reported amount of. al. n. v i n C ish discovered (i.e., U emissions. If a firm’s tax evasion y < e), a penalty is placed upon engchi. the evaded emissions according to the function (e y ) , which has the properties that (0) 0 , (e y) 0 and (e y) 0 for y < e. Each firm chooses x, a, and y to maximize its expected profits: max E 0 (1 ) 1 ,. (2.1’). x ,a , y. where E denotes the expectation operator. Moreover,. 4. We omit the fixed input in the expression of the production function. Self-reporting is a frequently used environmental enforcement policy. According to Russell (1990), the state environmental agencies in the US required 84% of water pollution sources to self-report. 6 The assumption that is strictly positive is to guarantee an interior solution for y. As shown in (2.4) below, as approaches zero, an interior solution for y requires an infinitely large marginal penalty, which seems infeasible in practice. 8 5.

(14) 0 f ( x) cx A(a) te (e y ) , which is the profit if the evader is caught, and. 1 f ( x) cx A(a) ty , which is the profit if the evader is not caught. By inserting 0 and 1 into (1’), we can rewrite the firm’s expected profit function as follows: E f x cx A a t e 1 y e y .. (2.1”). The first-order conditions for the firm’s profit maximization are: f c (t ) 0 ,. 立. A (t ) 0 ,. 政 治 大. (2.3). ‧ 國. 學. 1 t .. (2.2). (2.4). Equation (2.2) states that in equilibrium each polluting firm produces to the point. ‧. where the marginal revenue is equal to the sum of the marginal production cost, and. y. Nat. io. sit. the expected tax payment and penalty. Equation (2.3) indicates that in equilibrium. n. al. er. each firm equalizes the abatement cost with the expected tax and penalty, and (2.4) is. i n U. v. the firm’s tax arbitrage condition for choosing the optimal declared amount y .7. Ch. engchi. Combining (2.2) with (2.4) gives: f c t .. (2.5). In addition, combining (2.3) with (2.4) gives: A t 0 .. (2.3’). We note that the probability of inspection, , does not enter into (2.3’) and (2.5), which implies that both the production decision (represented by (2.5)) and the pollution abatement decision (characterized by (2.3’)) do not depend upon .. By following Sandmo (2002), we implicitly impose an additional condition (0) (1 )t (e) to guarantee an interior solution for y. 9. 7.

(15) Another implication of the above results is that the extent of the firm’s tax evasion is decided separately from the production and pollution abatement decisions. Such a separability property can also be found in other literature, e.g., Harford (1978, 1987) and Sandmo (2002).8 To proceed further with the analysis, we need to know the effects of the policy variables. The comparative-static results can be found in Appendix 2.2. As expected, an increase in t reduces the demand for the dirty input, and increases the level of the pollution abatement. Thus, the true net emissions decrease with t. In addition, a higher. 政 治 大 an increase in t has a larger adverse impact on y than on e, it stimulates the level of 立. t increases the firm’s production costs, thereby leading it to declare a smaller y. Since. under-reporting, which is measured by e y . Finally, and most notably, a stricter. ‧ 國. 學. audit policy has no effect on the true net emissions because of the separability. ‧. property; it only gives rise to a larger y. We summarize the above results as follows:. sit. y. Nat. io. er. Lemma 2.1: (i) An increase in the emission tax rate reduces both the actual net emissions (e), and the declared amount of net emissions (y); it also increases the. al. n. v i n C(ii)h a higher detectionU probability results in a larger amount of net emissions evaded; engchi declared amount of net emissions, but does not alter the true amount.. 2.3 The political equilibrium In this section, we introduce the influence of lobbying groups, and derive the political equilibrium policy. The economy contains three types of residents: owners of the polluting. 8. firms. (shareholders),. ordinary. consumers,. and. consumers. with. The separability property stems from some particular assumptions made by Sandmo (2002). There are many other ways (perhaps more sensible) of setting up a model, in which a higher detection possibility does affect the true amount of the pollution emissions. See Heyes (2000) for the related literature. 10.

(16) environmental concerns (environmentalists). Residents of the same type are homogeneous. The numbers of the population of shareholders, ordinary consumers and environmentalists are n f , nc and n g (where the subscript g refers to “greens”), respectively. We assume that the shareholders and the environmentalists organize themselves into respective lobbying groups. Each lobbying group offers political contributions to the policymaker to influence the formation of the emission tax rate. We assume that the ordinary consumers constitute a large part of the total population and are thus too. 政 治 大. numerous to overcome the free-rider problem and organize themselves into lobbying. 立. groups.. ‧ 國. 學. Before discussing the determination of the emission tax, it will prove convenient in what follows to define the welfare of each group. Firstly, the aggregate welfare of. ‧. the shareholders is given by:. (2.6). sit. y. Nat. W f E f S ,. n. al. er. io. where E is defined by (2.1’), and S denotes the total amount of the transfer. i n U. v. payment from the government, which is equal to S t[e (1 ) y] (e y). The. Ch. engchi. parameter f (0,1) stands for the fraction of the transfer payment received by the shareholders, which is exogenously determined. Secondly, the aggregate welfare of the environmentalists is:. Wg ng y g g S D(e) ,. (2.7). where y g is their exogenous income, g (0,1) denotes the fraction of the transfer payment received by the environmentalists, and D(e) stands for the aggregate disutility from net pollution emissions, with the properties D 0 and D 0 . Finally, the aggregate welfare of the ordinary consumers is given by: 11.

(17) Wc nc yc c S ,. (2.8). where y c is an individual consumer’s exogenous income, and c 1 f g denotes the fraction of the transfer payment received by the ordinary consumers. The timing of events is as follows. First, each lobbying group offers a contribution schedule, m, to the policymaker. The contribution schedule m is contingent upon the policy chosen by the policymaker. Then the policymaker determines the emission tax rate and collects political contributions. Finally, given the environmental tax rate, each firm in the polluting sector decides the net pollution. 政 治 大 We also assume that the 立enforcement policy is determined by other agents in the. emissions, and the reported amount of the emissions.. ‧ 國. 學. political process, say, bureaucrats, and that paying to affect the detection probability and penalty is considered to be bribery and illegal; or equivalently, we assume that the. ‧. lobbyists cannot influence the enforcement policy, and thus the lobbying groups treat. sit. y. Nat. the enforcement policies as exogenously given throughout this chapter. As indicated. n. al. er. io. in the Introduction, this setting enables us to accomplish a second-best analysis.. i n U. v. Following Grossman and Helpman (1994), the policymaker is assumed to. Ch. engchi. maximize a weighted sum of political contributions and social welfare, which is equal to:. f m f g mg W ,. (2.9). where the parameter j 0, j { f , g} is the weight the policymaker attaches to the contributions provided by group j. The social welfare function, denoted by W, is defined as the sum of all residents’ welfare, which is equal to:. W W f Wc Wg f ( x) cx A(a) nc yc ng y g D(e) .. (2.10). For ease of exposition, we assume that the two lobbying groups’ contribution 12.

(18) schedules are globally truthful; that is, each group’s contribution schedule everywhere reflects its true welfare.9 This assumption is not essential to our results. Without this assumption, all results that follow remain the same. With the global-truthfulness assumption, we can obtain the equilibrium emission tax rate by solving the following problem:. max G f W f gWg W .. (2.11). t. The first-order condition for the policymaker’s optimization is given by:. W W W G f f g g 0. t t t t. (2.12). 政 治 大. Under the global-truthfulness assumption, lobbying group j rewards the. 立. policymaker for every change in the action by exactly the amount of the change in its. ‧ 國. 學. welfare, that is, W j t m j t . Let us define W j t as group j’s (marginal). ‧. political pressure. Differentiating W f with respect to t gives rise to the shareholders’. y. sit. io. e f t ( f 1)[e (1 ) y ]. t t . n. al. er. W f. Nat. political pressure as follows:. i n U. (2.13). v. The above equation shows that an increase in t unambiguously reduces the welfare of. Ch. engchi. the shareholders, because they have to bear the full tax burden. Thus, they will lobby for a lower emission tax rate. The environmentalists’ political pressure is given by: Wg. e ( g t D) g [ e (1 ) y ]. t t . (2.14). This equation shows that the effect of t on the environmentalists’ welfare is ambiguous, because an increase in t reduces the net emissions and thus has an uncertain effect on the tax revenues. However, as we demonstrate below, this effect is 9. Bernheim and Whinston (1986) argue that the truthful Nash equilibrium may be focal among the set of Nash equilibria, because a truthful schedule is a best response to any strategy of the opponent, even if it is not the only best response. 13.

(19) positive in the equilibrium, indicating that the environmentalists will lobby for a higher emission tax rate in the equilibrium. Inserting (2.13) and (2.14) into (2.12) and rearranging gives the equilibrium emission tax, which is denoted by t* , as follows:. t* . f A [ˆ f ] e (1 ) y 1 g , D 1 ˆ ( A f )(1 ˆ). (2.15). where ˆ f f g g is the weighted average of the two groups’ political weight. Since the sign of ˆ f on the right-hand side of (2.15) is ambiguous, t* can be either. 政 治 大. greater or less than the marginal damage D .. 立. We first note that in the case where the policymaker is benevolent, which can be. ‧ 國. 學. characterized by setting both f and g equal to zero, the tax rate that maximizes. (2.16). io. al. er. Thus, we have the following result:. sit. y. Nat. t o D .. ‧. social welfare, which is denoted by t o , is equal to the Pigouvian tax,10 i.e.,. n. v i n Lemma 2.2: In the absence of C lobbying, the emissionUtax rate that maximizes social hengchi welfare is equal to the Pigouvian tax.. The intuition underlying this result is as follows. As indicated above, the separability property implies that the presence of private information does not distort the firms’ decisions on the real variables. Moreover, it is well known that in the case of full information, the most efficient emission tax is the Pigouvian tax. Since the. 10. Nevertheless, Cremer and Gahvari (2002) claim that the optimal emission tax in the situation with asymmetric information will not be equal to the Pigouvian tax, if there are additional monitoring and enforcement costs. Bontems and Bourgeon (2005) also conclude that the second-best result may not be implemented with a Pigouvian tax when there are distortions in the rest of the economy. 14.

(20) decision rule on the net emissions is the same in both the full and asymmetric information cases, the two cases give rise to the same tax rate that maximizes social welfare. Comparing the equilibrium tax rate, t* , with the efficient tax rate, t o , shows how the lobbyists distort the emission tax. Let us consider the case where only the shareholders lobby, which can be characterized by setting f 0 and g 0 . As indicated by (2.13), the shareholders exert downward political pressure on t, and thus (2.15) shows that the shareholders’ lobbying results in t * t o .. 政 治 大. On the other hand, if the environmentalists are the only active lobbying group,. 立. which can be characterized by setting f 0 and g 0 , then we obtain that. ‧ 國. 學. t * t o . By inserting (2.15) into (2.14), we obtain that Wg t 0 , indicating that in. ‧. equilibrium an increase in t enhances the environmentalists’ welfare, and thus the. sit. y. Nat. green lobbying leads to an excessively high tax rate.. io. al. n. the efficient tax t o :. er. The following proposition summarizes all the possible results between t* and. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Proposition 2.1: (i) If f ˆ and g ˆ , then t * t o , (ii) if f ˆ and g ˆ , then t * t o , and (iii) in other cases, the relationship between t* and t o is ambiguous. Proof: See Appendix 2.2. 2.4. The effects of enforcement policy A number of earlier studies and Section 2.2 of this present chapter have demonstrated that the enforcement policy has nothing to do with the true amount of net emissions. Such a result, however, does not necessarily hold with lobbying. In this section, we 15.

(21) explore the effects of the enforcement policy on the emission tax and social welfare.. 2.4.1 Audit policy The effect of the audit policy on the true net emissions is given by: de e e t * . d t 0. . (2.17). ?. Equation (2.17) shows that the effect of a change in , the probability of detection, consists of the direct effect and the indirect effect. According to the comparative-static. 政 治 大. results in Lemma 2.1, the direct effect equals zero, and only the indirect effect remains.. 立. The indirect effect stems from the influence of the lobbyist. To determine this. ‧ 國. 學. effect, we differentiate (2.15) with respect to , and obtain:. ‧. * ˆ) f A (1 ) t e y ( f t * . ˆ ( A f )(1 ). Nat. sit. y. (2.18). io. er. The denominator of (2.18) is positive, but the numerator is ambiguous, depending on the sign of f ˆ . If f ˆ , meaning that the shareholders have a relatively large. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. political influence, then t * decreases with . By contrast, if f ˆ , then t * increases with . The intuition underlying these results is as follows. As indicated in (2.13), a higher increases each firm’s expected tax payment, and thus the polluters have a stronger incentive to lobby for a lower tax rate. Meanwhile, (2.14) reveals that the environmentalists’ upward political pressure increases with . An increase in leads the environmentalists to receive a larger amount of transfers, and thus they exert a greater upward pressure on t. In the case where the shareholders are dominant, their larger downward pressure leads to a lower tax rate. If the environmentalists are dominant, then the opposite occurs. 16.

(22) Lemma 2.3: In the case where the shareholders have a relatively large political influence, such that f ˆ f f g g , the equilibrium emission tax rate decreases with . In the case where the environmentalists have a relatively large political influence, such that f ˆ , the equilibrium emission tax rate increases with .. By combining the above results with the fact that e t 0 , we can pin down. 政 治 大. the sign of (2.17). The effect of on e can be either positive or negative, depending. 立. on the relative political influence of the lobbies. This result indicates that the audit. ‧ 國. 學. policy does have an impact on e, although it works in an indirect way. A more interesting implication of this result is that an increase in the probability. ‧. of detection can enlarge the true amount of pollution emissions, in particular when the. y. Nat. sit. polluters have a relatively large political influence. As indicated in Lemma 2.3, when. n. al. er. io. the shareholders are dominant, an increase in leads to a lower emission tax rate,. i n U. v. and thus a larger amount of net emissions. This result is different from the. Ch. engchi. conventional wisdom and the finding in Harford (1978, 1987) and Sandmo (2002). This also indicates the possibility that policymaking will be misguided due to overlooking the political effect. Since the audit policy has the real effect, it also affects social welfare. It is hardly surprising that the welfare effect of the audit policy is ambiguous. Here we focus on some polar cases to obtain definite results. We first consider the case where only the shareholders lobby. In this case, as indicated in Proposition 2.2, t is lower than t o . In addition, Lemma 2.3 has shown that t decreases with in this case. The negative relationship between t and implies that an increase in causes the 17.

(23) emission tax rate to deviate further from the optimal level. by assuming the social welfare function to be convex, the above analysis reveals that tightening the audit policy reduces social welfare. As a result, in this case the second-best audit policy that accommodates the influence of lobbying is the minimum value of . We then turn to the case where only the environmentalists lobby. We have learned two facts in this situation: (i) t is higher than t o , and (ii) t increases with . Combining these two facts reveals that an increase in causes t to rise. further above t o , thereby leading to a lower level of social welfare. Accordingly, in this case the second-best audit policy also requires that the minimum level of be set.. 立. 政 治 大. An increase in , however, can enhance social welfare in more general cases.. ‧ 國. 學. For example, it is possible that t is greater than t o , and that it decreases with .11. ‧. In this case, an increase in reduces t , which narrows the gap between t and. sit. y. Nat. t o , and thus enhances efficiency.. io. er. The following proposition summarizes what we have found above:. al. n. v i n Cinhthe detection probability Proposition 2.2: (i) An increase either raises or reduces engchi U. the equilibrium emission tax rate, depending on the relative political influence of the lobbies; (ii) the welfare effect of tightening the audit policy is ambiguous, which implies that an increase in can reduce social welfare.. 2.4.2 Penalties We adopt the penalty function in a general functional form in the previous sections. In order to examine the effect of a shift in the penalty function, we specify the penalty 11. From (15) and Lemma 3, we know that this case may occur if. than ˆ . 18. f ˆ. and. g. is much larger.

(24) function as follows:. (e y ) (e y )2 ,. (2.19). where 0 denotes the shift parameter of the penalty function. The effect of a shift in the penalty function on the net pollution emissions is: de e e t * . d t 0. . (2.20). ?. As in the case of the audit policy, the effect of a change in consists of the direct effect and the indirect effect. The direct effect is equal to zero because of the separability property. The indirect effect depends on the sign of t * , which is given by:. 12. 立 . 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. e y f A [ f ˆ] (1 ) t . ( A f )(1 ˆ) *. (2.21). ‧. Equation (2.21) has the same sign as ˆ f . If the political weight of the. sit. y. Nat. shareholders is so large that f ˆ , then an increase in reduces t* . By contrast,. n. al. to that explaining the effect of. er. io. if f ˆ , then t* increases with . The intuition underlying these results is similar. v i n C hon t , and so we doUnot repeat it here. engchi *. Since e t is negative, (2.20) has the opposite sign to (2.21). Thus, if f ˆ , then the net pollution emissions increase with , implying that a stiffer penalty increases pollution emissions. This result again shows that disregarding the political effect may lead the environmental policy to generate unintentional outcomes. On the other hand, if f ˆ , then the net pollution emissions decrease with . In this case, raising the penalty achieves the intended goal. We then move on to the welfare implication of a change in . Apparently, the 12. The derivation of (2.21) is presented in Appendix 2.3. 19.

(25) welfare effect of a change in the penalty is ambiguous, and again we focus on some polar cases. In the case where only the shareholders lobby, t* is lower than t o , and it decreases with . These two facts together imply that an increase in reduces social welfare. In the case where only the environmentalists lobby, t* is set at an excessively high level, and an increase in raises t* . These relationships also suggest that social welfare decreases with . Nevertheless, a stiffer penalty can be welfare-enhancing in other more general cases.. 政 治 大 equilibrium emission tax rate, depending on the relative political influence of the 立. Proposition 2.3: (i) An increase in the penalty either raises or reduces the. interest groups; (ii) the welfare effect of a stiffer penalty is ambiguous, which implies. ‧ 國. 學. that an increase in can reduce social welfare.. ‧ sit. y. Nat. 2.4.3 Discussion. io. er. The above analysis highlights the possible perverse effects arising from a tightening of the enforcement policy. This finding is in line with that of Kambhu (1989) and. n. al. Heyes (2002).. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Kambhu (1989) investigates the effect of imperfect regulatory enforcement on the compliance of polluters, when the polluters can take action to evade penalties for non-compliance. He shows that a marginal increase in the penalty may cause compliance to fall, because a stiffer penalty increases the polluters’ incentive to intensify their challenge to enforcement. Heyes (2002) constructs a two-stage model of regulatory enforcement. An inspection in the first stage gives rise to a noisy signal of the inspected firm’s true amount of pollution. Only if the signal exceeds the “trigger” will the inspected firm be audited. Heyes (2002) finds that a tighter trigger may cause the performance of 20.

(26) serious violators to decline, and lead to more pollution emissions. The intuition behind this result is that a tighter trigger enlarges the gap between the trigger and the true level of emissions, and thus reduces the marginal benefit of abatement. Although our finding is similar in spirit to the conclusions of these two papers and others, this present chapter takes the political aspect into consideration, which has been overlooked in the above literature. Moreover, these papers are positive models, but we provide some normative implications in addition to positive issues.. 政 治 大 In this chapter, we investigate how the influence of lobbying shapes environmental 立. 2.5. Concluding remarks. policy in the presence of imperfect compliance. We also examine the effects of. ‧ 國. 學. enforcement policy on the stringency of environmental policy. Our major finding is. ‧. that tightening the enforcement policy can increase pollution emissions and reduce. sit. y. Nat. social welfare. This result is quite different from the finding in Becker (1968), who. io. er. claims that the optimal fine should be set at the maximal level.. In order to obtain tractable results, we construct a simple setting. Nevertheless,. al. n. v i n C hincluding the monitoring doing so overlooks several issues, costs, and the interaction engchi U. between the intertemporal self-reporting decision and the detection probability. Further extension could give rise to important and interesting insights.. 21.

(27) Appendix Appendix 2.1: The comparative-static results of Lemma 2.1: By differentiating (2.5) and (2.3’) with respect to t and , respectively, and after some rearrangements, we have the following results:. a 1 0 , t A . x 1 0, t f . y 1 1 1 0, t f A . e 1 1 0, t f A. (e y) (1 ) 0, t . e 0, e y t 0. . 立. y t 0, 治 政 大. ‧ 國. 學. Appendix 2.2: Proof of Proposition 2.1:. ‧. From (2.15) we have the following relationship:. y. Nat. f A [ˆ f ] e (1 ) y t De De . 1 ˆ ( A f )(1 ˆ). io. n. al. i n U. The above equation implies the results in Proposition 2.2.. Ch. engchi. sit. g ˆ. er. *. v. Appendix 2.3: Derivation of (2.21): We express the penalty function in the specific form of ( e y ) 2 . The firm’s expected profit becomes: E f ( x) cx A(a) t[x (1 ) y a] (e y ) 2 .. The first-order conditions for profit maximization are: f c t 2 e y 0 ,. A t 2 e y 0 , 22.

(28) 1 t 2 e y . Hence, the comparative-static results are as follows:. a 1 0 , t A . x 1 0, t f . y 2 ( f A ) ( 1 )f A 0, t 2 f A . e 1 1 0, t f A (e y) (1 ) 0, t 2 e 0, . y e y 0, . e y e y 0. . 治 政 大 (2.21). Then totally differentiating (2.15) with respect to gives 立 ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 23. i n U. v.

(29) Chapter III A political economy of tax havens 3.1 Introduction International tax avoidance through tax havens has become the focus of much attention and debate. The term “harmful tax havens” usually refers to jurisdictions that impose no or low taxation, along with other features, including non-transparency, ring-fencing of mobile activities, and so on (Nicodème, 2009). Although several. 政 治 大 Michael Smart argues that tax havens can enhance high-tax countries’ social welfare, 立. countries have campaigned against tax heavens,13 a recent paper by Qing Hong and. which is quite contrast with the conventional view.. ‧ 國. 學. The analysis of Hong and Smart (2010) is based on the assumption that the. ‧. policymakers are benevolent. However, it is well known that special interest groups. sit. y. Nat. play a significant role in the process of policy making (Hillman, 1982, 1989; Poterba,. io. er. 1998; Grossman and Helpman, 2002). Then a natural question arises: will the welfare enhancing property of tax heavens still be sustained in the presence of lobbying? We. al. n. v i n C hthe influence of interest aim to address this question. Since groups seems inevitable in engchi U policymaking, our answer contains policy implications.. We construct a standard tax competition model incorporating tax havens and interest groups. There are a large number of (non-haven) countries that compete for mobile capital by setting their capital taxes. There are two types of capital, mobile and immobile. Each country levies a uniform tax on the two types of capital. The tax revenues are distributed to poor residents (pensioners). In addition to the non-haven countries, there also exist some jurisdictions that are referred to as tax havens. The tax havens levy no tax, and they simply provide firms located in the non-haven countries 13. The OECD have advocated to campaign against tax havens since 1998 (OECD, 1998, 2000). 24.

(30) with opportunities to reduce tax burdens on mobile capital through international tax planning. The owners of capital are assumed to organize themselves into a lobbying group, and they offer political contributions to their policymaker in order to influence the capital tax rate. Within this framework, we examine how the international tax planning activity affects the capital tax rates, and the social welfare of the non-haven countries. A major finding of this present chapter is that a non-haven country’s social welfare can decrease with the extent of international tax planning, in particular when the. 政 治 大 (2010), which claim that. policymaker attaches a large weight to political contributions. This is contrast with the result of Hong and Smart. 立. a unilateral increase in. international tax planning unambiguously enhances the non-haven country’s welfare.. ‧ 國. 學. The intuition underlying this result is as the follows. The optimal taxation rule. ‧. requires different tax rates imposed on the mobile capital and the immobile capital. As. sit. y. Nat. argued by Hong and Smart (2010), such a differential tax treatment is generally. io. er. prohibited by some practical reasons. International tax planning activity provides a desirable differential tax treatment, and thus enhances efficiency. This is the intuition. al. n. v i n Hong C and Smart (2010). U h e n g c h i In addition. of the main result in. to the efficiency. consideration, there arises a political effect in this present chapter. As demonstrated below, an increase in the tax planning activity can induce the capitalists to exert a greater political pressure to reduce the capital tax rate. This political effect drives the already sub-optimally low tax rate further below the efficient level, and thus leads to a lower level of social welfare. If the political effect outweighs the enhancement in welfare due to differential tax treatment, then a larger extent of tax planning reduces the social welfare. Another finding is regarding the effects of international cooperation on reducing the international tax planning activity. The previous literature has pointed out that 25.

(31) such an international cooperation is beneficial to the non-haven countries (e.g., Haufler and Runkel 2009; Slemrod and Wilson 2009). However, we demonstrate that, in the presence of lobbying, the cooperation on reducing the international tax planning activity can reduce the non-haven countries’ welfare. The reason for this result is based on two findings. First, the equilibrium capital tax rate is lower than the level that maximizes a non-haven country's social welfare. Secondly, a coordinated reduction in the international tax planning activity can lead to a lower tax rate. Combining these two outcomes shows that the cooperation on reducing international. 政 治 大 the efficient level, and thus reduce all non-haven countries’ social welfare. 立. tax planning activity can cause the sub-optimally low tax rate to deviate further below. The remainder of this chapter proceeds as follows. Section 3.2 describes the. ‧ 國. 學. basic tax competition model with tax havens. Section 3.3 introduces the capitalists’. ‧. lobbying and obtains the political equilibrium capital tax rate. Section 3.4 and 3.5. sit. y. Nat. examine, in the presence of political power, how international planning affects the. io. workers' lobbying. The last section concludes.. n. al. 3.2 The Model. Ch. engchi. er. equilibrium capital tax rate and social welfare. Section 3.6 discusses the role of. i n U. v. Our basic model builds on the works of Zodrow and Mieszkowski (1986) and Haulfer and Runkel (2009). We consider a large number of identical (non-haven) countries. Each country contains three types of residents: capitalists, workers, and pensioners. All residents are immobile across countries and the residents of the same type are identical. We normalize the number of the pensioners to unity, and let n k and nl be the numbers of capitalists and workers, respectively. Each capitalist possesses h units of immobile capital, k n , and one unit of internationally mobile capital, k m . Each worker is endowed with one unit of labor, 26.

(32) and inelastically supplies labor to firms. Finally, pensioners, defined as those who are endowed with nothing, receive transfer payments from the government. Suppose that each country contains a firm, which is a price taker in the international market. The firm hires the immobile capital, mobile capital, and labor to produce an output. The two types of capital are perfectly substitutes in producing the output. In addition to the non-haven countries, there also exist several countries or jurisdictions levying no taxation on capital,14 which we refer to as tax havens. The. 政 治 大 specifically, a firm can set up a financial subsidiary in a tax haven. The subsidiary 立 existence of the tax havens enables the firms to exert international tax planning. More. does not produce output;15 it only makes an intra-company loan (usually merely. ‧ 國. 學. paperwork) to its parent company, whose country permits the deduction of interest. ‧. payment for this loan. As shown below, the firm is able to reduce overall tax burdens. sit. y. Nat. by using the internal debt financing.. io. er. In reality, these intra-loan strategies are often constrained by a number of factors, including transaction costs, the agency problems, long-term natures of tax codes, or. al. n. v i n C h Most of these factors the numbers of available tax havens. are beyond the control of engchi U. the firms.16 To characterize the tax planning in the simplest way, we follow the specification of Hong and Smart (2010) by assuming that the a firm’s internal debt to its subsidiary is bounded by an exogenous proportion, [0,1) . Also by following Hong and Smart (2010), we assume that the firms will issue the debt up to the upper bound. Accordingly, the profit function of the firm is written as: 14. Allowing tax havens to impose a positive tax rate on capital income does not alter the following results. 15 According to the empirical evidence, tax havens are usually very small jurisdictions (Hines and Rice, 1994; Dharmapala and Hines, 2009). Without loss of generality, we neglect productive activities in tax havens. 16 See Desai et al. (2004) and Hong and Smart (2010) for more discussions. 27.

(33) f (k ) k n (r n t ) k m [r m (1 )t ] nl w ,. (3.1). where k is the total capital employed, which is equal to k n k m . The production function. f (k ) has the standard properties. f (k ) 0 and. 17 The f (k ) 0 .. variables r n and r m are the net return to immobile capital and mobile capital, respectively. The government imposes a source-based tax at rate of t on each unit of capital. The capital tax rate is restricted to be non-negative. We note that the international tax planning lowers the effective tax rate on the mobile capital to (1 )t . The wage rate is denoted by w .. 政 治 大. The firm chooses k n and k m to maximize (3.1). The first-order conditions for profit maximization are:. 立. r m f ' (k ) t (1 ) .. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. r n f ' (k ) t ,. (3.2) (3.3). io. er. than the immobile capital’s.. sit. y. Nat. Since the mobile capital encounters a lower effective tax rate, its net return is higher. In addition, the wage rate is adjusted to the point where it is optimal for the firm. al. n. v i n C h (3.2) and (3.3)Uinto (3.1) gives the aggregate to employ all labor supply. Inserting engchi wage income as follows:. nl w(k ) f (k ) k f (k ) .. (3.4). Since there are a large number of identical countries, an individual country regards the net rate of return of the mobile capital as given. Therefore, it follows from (3.3):. 17. k 1 (1 ) 0 , f t. (3.5). k 1 t 0. f . (3.6). For notational simplicity, the fixed labor input is omitted in the production function. 28.

(34) Equation (3.5) says that the firm’s capital demand decreases with t. We note that the adverse effect of t on the capital demand decreases with . It is because with a larger. , the increase in the user cost of mobile capital due to an increase in t is lower. Hence, the reduction in the firm's capital demand is smaller with a higher level of tax planning. Equation (3.6) indicates that a rise in international tax planning lowers the user costs of mobile capital, and therefore increases the capital demanded. Although an individual country’s policy cannot change the net return on the mobile capital, it affects the net return on the immobile capital, r n . The effect of t on. 政 治 大. r n is given by n. dr dt. 立. (3.7). ‧ 國. 學. Equation (3.7) shows that the effect of t on r n depends on the level of tax planning; the larger , the larger adverse effect of t on r n will be. From (3.2), the amount of. ‧. capital employed and the tax rate jointly determine r n . The capital outflow due to an. sit. y. Nat. increase in t raises the marginal product of capital, which in turn mitigates the adverse. n. al. outflow, leading to a greater negative impact on r n .. Ch. engchi. er. io. impact of t on r n . However, with a larger , an increase in t causes less capital. i n U. v. A representative capitalist’s preferences are given by: uk h rn rm.. A representative worker’s preferences are described by:. ul w f (k ) k f (k ) nl . Finally, the utility function of a representative pensioner is given by (recall that the number of the pensioners is normalized to unity): u p t[(1 )k n k h ] .. The social welfare function W is defined as a weighted utilitarian function: W W k W l (1 )W p ,. (3.8) 29.

(35) where W k , W l and W p denote the aggregate welfare of capitalists, workers, and pensioners, respectively. The government attaches a weight, 1 ( 0) , to the pensioners’ welfare. For the redistribution concern, the capital tax revenues are distributed to the pensioners in a form of lump-sum transfers. Each type of residents’ aggregate welfare is given as follows: W k n k u k n k (hr n r m ) , W l nl ul nl w ,. W p u p t[(1 )k n k h ] ,. It would be helpful for the future use to derive the effects of t and on the welfare of each type of residents:. 立. ‧ 國. 學. W k n k h , t. 政 治 大. W k n k ht , . (3.9a) (3.9b). ‧ sit. W p 1 n k (1 h) (1 ) 2 t, t f . n. Ch. engchi. W p 1 (1 ) t nk t . f . (3.9d). er. io. W l n k (1 h)t , . al. (3.9c). y. Nat. W l n k (1 h)(1 ) , t. i n U. v. (3.9e) (3.9f). As long as tax planning is possible (i.e., 0) , a reduction in t is benefit to the capitalists. A lower t also enhances the workers’ welfare, because a lower tax rate attracts capital inflow, which in turn enlarges the wage rate. An increase in has a similar effect on the workers’ welfare as a reduction in the tax rate. We also notice the adverse effect of on the capitalists’ welfare. Although a higher increases the net return to mobile capital, it also attracts capital inflows, which reduce the returns to both immobile and mobile capital. Equation (3.9b) reveals that the latter effect outweighs the former one, so that an increase in makes the capitalists worse off. 30.

(36) Finally, both the effects of tax rate and tax planning on the welfare of the pensioners are ambiguous.. 3.3 Political Equilibrium The capitalists are assumed to organize themselves into a lobbying group, and offer political contributions to the policymaker to influence the capital tax rate. For the time being, we assume that the workers are inactive in lobbying. We introduce the workers’ lobbying in Section 3.6.. 政 治 大 offer contribution schedules to their policymaker, each taking as given the schedule of 立. The timing of events is as follows. First, the lobbying groups simultaneously. all other lobbies in other countries. The contribution schedule is contingent upon the. ‧ 國. 學. capital tax rate chosen. Then, the policymakers simultaneously set their capital tax. ‧. rates and collect political contributions. At last, given the capital tax rates, the firms. sit. y. Nat. decide the demand for capital and labor.. io. er. Following Grossman and Helpman (1994), the objective function of the policymaker is assumed as the weighted average of political contribution received and. n. al. Ch. social welfare, which is given by. m W k. engchi. i n U. v. where m is the amount of political contributions, and 0 denotes the weight the policymaker attaches to the political contributions. For ease of exposition, we assume that the lobbying groups’ contribution schedules are globally truthful; that is, each lobby’s contribution schedule everywhere reflects its true welfare. 18 Under the global-truthfulness assumption, the equilibrium tax rate can be characterized by solving the following equation:. 18. The global-truthfulness assumption is not essential for our analysis. The results remain the same without this assumption. 31.

(37) max G W k W (1 )W k W l (1 )W p .. (3.10). t. From (3.8), we obtain the equilibrium capital tax rate, denoted by t e , as follows: n k f t [(1 h) h ] . (1 )(1 ) 2 e. (3.11). We need the capital tax rate that maximizes social welfare, which is denoted by t , to serve as a benchmark. Our setting enables us to obtain t by simply. substituting 0 into (3.11). It follows that if 0 , then t 0 , indicating that when the government has no redistribution concern, the optimal capital tax rate of a small open economy should be equal to zero (Gordon, 1986; Bucovetsky and Wilson,. 政 治 大. 1991). However, the government’s redistribution concern ( 0 ) will lead the. 立. optimal capital tax rate to be positive. Moreover, we can verify that if 0 , then. ‧ 國. 學. t e t . Equation (3.9a) shows that the capitalists’ welfare decreases with t, and thus. they have an incentive to lobby for a lower tax rate, leading to t e t .. ‧ y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. Lemma 3.1. The capitalists’ lobbying gives rise to a suboptimal low capital tax rate.. 3.4 Effects of International Tax Planning. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. According to (3.11), the equilibrium tax rate depends on international tax planning . A change in alters the marginal impact of the tax rate on the lobby’s welfare, which in turn affects the lobby’s pressure on t . Such a political effect of seems being ignored in the literature, whereas it is our main focus. As shown in Section 3.5, overlooking the political effect of . can cause misguidance in. policymaking. Differentiating (3.11) with respect to gives the effect of on t e as follows:. 32.

(38) t e n k f ( 2h h h ) , (1 )(1 )3. (3.12). Immediately, we have the following result:. Proposition 3.1. An increase in international tax planning reduces (increases) the equilibrium capital tax if t ( t ), where t (1 ) 2h h(1 ) .. As increases, the redistribution concern induces the policymaker to raise t. On the other hand, according to (3.9a), a larger aggravates the adverse impact of. 政 治 大. the tax on the capitalists’ welfare, leading them to exert a greater political pressure to. 立. is sufficiently large, then the political effect outweighs the. 學. ‧ 國. reduce t. If . redistribution effect, so that the tax rate decreases with . Otherwise, the tax rate will increase with .. ‧ y. Nat. n. al. er. io. 3.5.1. A unilateral increase in international tax planning. sit. 3.5 Welfare implications. i n U. v. An interesting result in Hong and Smart (2010) is that international tax planning. Ch. engchi. unambiguously improves the welfare of high-tax countries. The intuition underlying their result is as follows. Practical reasons generally restrict the implementation of the optimal tax rule, which requires differential tax rates on the different types of capital. However, international tax planning provides a desirable differential tax treatment, and thus enhances efficiency. In what follows, we demonstrate that such efficiency improvement due to tax planning does not necessarily occur in the presence of lobbying. To elaborate on this notion, we totally differentiate (3.8), the social welfare function: 33.

(39) dW W dt W . d t d . (3.13). Rearranging (3.13) gives the effect of international tax planning on social welfare as follows:19 k2 2 2 dW n h f h (1 h) . d (1 )(1 )3. (3.14). Let us first consider a special case where the international tax planning is prohibited initially. In this case, (3.14) reduces to dW n k 2 h f (1 h) 2 0. d (1 )3. (3.15). 政 治 大. Hence, we have the following proposition.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Proposition 3.2. Suppose that international tax planning is prohibited initially. A unilateral increase in international tax planning in a high-tax country improves its. ‧. social welfare, regardless the magnitude of .. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. As indicated in (3.9a), the marginal adverse effect of t on the capitalists’ welfare. i n U. v. depends on . If the initial equals zero, then the capitalists’ welfare is. Ch. engchi. independent of t, and thus they will not lobby. In this case, like in Hong and Smart (2010), an increase in enables the high-tax country to implement a differential tax treatment on the two kinds of capital, and thus enhances efficiency. However, if the initial international tax planning is not equal to zero, then an increase in is not necessarily efficiency-enhancing, as shown in the following proposition.. Proposition 3.3. If the initial level of international tax planning is positive, then a 19. See Appendix 3.1 for the derivation of (3.14). 34.

(40) unilateral increase in international tax planning in a high-tax country may either increase or reduce its social welfare. In particular, social welfare will be reduced (improved) if u ( u ) where u (1 h) / h . Proof: See Appendix 3.2.. With a positive , the political effect emerges. As indicated in (3.9a), a larger. leads the capitalists to exert a stronger downward pressure on the tax rate. Combining this result with Lemma 3.1, that shows that the equilibrium tax rate has. 政 治 大 below t , and reduces social 立welfare.. been set below the efficient level, indicates that the political effect drives t e further . ‧ 國. 學. In sum, when the initial tax planning is positive, an increase in brings about two effects: one is a welfare-enhancing effect due to enforcing differential tax. ‧. treatment, and the other is a welfare-reducing effect arising from lobbying. If is. sit. y. Nat. sufficiently large, then the latter effect will outweigh the former one, so that social. n. al. er. io. welfare decreases with .. Ch. engchi. 3.5.2. Global reduction of tax planning. i n U. v. Thus far we have discussed the effect of a unilateral change in tax planning in an individual high-tax country. In this subsection, we turn to investigate the effect of the international cooperation on reducing the tax planning. We characterize this scenario by assuming that all countries cooperatively reduce the tax planning by the same magnitude. In order to distinguish the notation from the previous analysis, we denote. ˆ as the global agreement on tax planning. Since ˆ changes simultaneously across countries, the global agreement does not reallocate capital, i.e., k / ˆ 0 . By using this fact, we further obtain that the following results: W k / ˆ n k t , W l / ˆ 0 , 35.

(41) and W p / ˆ n k t . Accordingly, the effect of ˆ on each country’s welfare is expressed as:. 20. k2 2 2 2 dW n f h (1 ) 2h (1 h) (1 h)(1 ) . dˆ (1 )(1 )3. (3.16). We first consider the case where the government is benevolent, which can be characterized by setting 0 , and we have the following proposition:. Proposition 3.4. When the government is benevolent, i.e., 0 , a global cooperation to reduce international tax planning activities (a lower ˆ ) improves the welfare of all high-tax countries.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. The intuition of Proposition 3.4 is quite straightforward. Without the political. ‧. effect, a global cooperation to reduce tax planning acts as nothing but to transfer the. sit. y. Nat. income from the capitalists to the pensioners.21 Since the governments attach a higher. io. er. weight to the welfare of the pensioners, the international cooperation certainly improves social welfare in all high-tax countries. Proposition 3.4 is close to the result. al. n. v i n in Slemrod and Wilson (2009), C who demonstrate that U h e n g c h i the elimination of all tax havens increases high-tax countries’ welfare.. The presence of lobbying, however, can reverse the effect of the global cooperation on reducing the tax planning, which is shown in the following proposition.. Proposition 3.5. In the case where 0 and under the condition (1 h) 1 , there exists an interval of , g , g . If g , g , then a global cooperation to 20 21. See Appendix 3.3 for the derivation of (3.16). We can see this from W k / ˆ n k t and W p / ˆ n k t . 36.

(42) depress international tax planning (a reduction in ˆ ) reduces the welfare of all high-tax countries. Proof: See Appendix 3.4.. Proposition 3.5 suggests that the existence of political effect can cause the global cooperation to be undesirable. To see this, we divide the effect of a reduction in ˆ on welfare into two parts: the direct effect ( W ˆ ) and the indirect effect ( W t dt ˆ ):. dW W W dt . dˆ ˆ t dˆ. (3.17). 治 政 As mentioned previously, the direct effect is negative, 大 meaning that a reduction in ˆ 立 . . ?. is welfare-enhancing, because it transfers the income from the capitalists to the. ‧ 國. 學. pensioners.. W. is positive. Moreover, according to Proposition 3.1, the term. Nat. t. dt. can. ˆ. y. the term. ‧. As to the indirect effect, since the lobbying leads to a sub-optimally low tax rate,. dt. ˆ. is. er. io. sit. be either positive or negative, depending on the value of . In the case where. positive, the indirect effect is also positive; i.e., a reduction in tax planning will reduce. al. n. v i n C h effect dominates the social welfare. When the indirect the direct effect, the global engchi U. cooperation on reducing tax planning will reduce all high-tax countries’ welfare. The intuition is that a reduction in ˆ drives the equilibrium tax further below that the tax rate that maximizes social welfare, and thus reduces the social welfare in all high-tax countries. On the other hand, in the case where. dt. dˆ. is negative, both direct and indirect. effects are negative. In other words, the political effect will increase the welfare-improving of the global cooperation.. 37.

(43) 3.6 Worker’s lobbying In this section we extend the basic model to consider that both the capitalists and the workers engage into lobbying. Let represent the weight that the policymaker attaches to the workers’ political contributions. Then the equilibrium tax rate is the solution for the following equation: max J (1 )W k W l (1 B)W p ,. (3.18). t. where ( ) /(1 ) and B ( ) /(1 ) . We first consider the case that the policymaker attaches the same weight to the. 政 治 大 in (3.11)立 to see that the equilibrium tax rate will be zero, and it is. two groups’ contributions ( ). If , then B 0 ; we can replace ( , ) by (0,0). ‧ 國. 學. independent of the level of international tax planning.. If , (3.18) reduces to J W k W l (1 B)W p , where B 0 . This. ‧. equation is very similar to (3.10) with 0 . Therefore, it is easy to see that in this. sit. y. Nat. case, the direction of the effect of on social welfare (unilateral or global) is the. n. al. er. io. same as the previous case where 0 and the workers do not lobby.22. i n U. v. A more complicated case is that the policymaker attaches different weights to the. Ch. engchi. two groups’ political contributions ( ). Although various possibilities emerge, the main results derived in Section 3.4 and 3.5 can still hold, at least in quality. The basic intuition is as follows. The two lobbying groups prefer a lower capital tax rate. When a higher strengthens the capitalists’ downward pressure, it also reduces the workers’ downward pressure.23 Since causes opposite effects on the two groups' lobbying effort, the net political effect depends on the difference between the two groups’ weights (i.e., | | ). Specifically, the previous results will be sustained,. 22. Note that since we restrict te to be nonnegative, we have ruled out the β<θ=δ case. This can be seen from (9a) and (9c) that when rises, the adverse welfare effect of capital tax on the capitalists increases, and the effect on the workers decreases. 38 23.

數據

相關文件

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>

For pedagogical purposes, let us start consideration from a simple one-dimensional (1D) system, where electrons are confined to a chain parallel to the x axis. As it is well known

The observed small neutrino masses strongly suggest the presence of super heavy Majorana neutrinos N. Out-of-thermal equilibrium processes may be easily realized around the

incapable to extract any quantities from QCD, nor to tackle the most interesting physics, namely, the spontaneously chiral symmetry breaking and the color confinement..

(1) Determine a hypersurface on which matching condition is given.. (2) Determine a

• Formation of massive primordial stars as origin of objects in the early universe. • Supernova explosions might be visible to the most

The difference resulted from the co- existence of two kinds of words in Buddhist scriptures a foreign words in which di- syllabic words are dominant, and most of them are the

(Another example of close harmony is the four-bar unaccompanied vocal introduction to “Paperback Writer”, a somewhat later Beatles song.) Overall, Lennon’s and McCartney’s