An Analysis of the China-India Relations from

the Perspective of Indo-Pacific Security

Ming-shih Shen

Associate Professor and Director, Graduate Institute of Strategic Studies, National Defense UniversityAbstract

The issue of China-India borders, which can be traced to the military clashes in 1962, continues as the root of discord between the two giants in Asia. China and India both take the disputed pieces of territory as core interests. They are inimical to each other on this issue and are emphatic of their strong will not to budge an inch. Given their relentless effort to strengthen military infrastructure and force deployment along the borders, once a demonstration of power erupts into clashes, it will surely impact Indo-Pacific regional security, which will force neighboring countries into a quandary. Despite the diplomatic effort that has been made to ease the tension, skepticism towards each other remains. Thus, the picture has not changed significantly—any triggering events sustained by historical grievance and geostrategic concern may bring about armed clashes. Only when New Delhi is capable of having the Indian voice heard through the region via its foreign policy and economic activities checking China’s expansive acts, can international society recognize India as a key pillar of security in Indo-Pacific and South Asia.

Keywords: China-India Relations, Indo-Pacific Security, Ladakh Border Conflict,

Doka La incidents, Belt and Road Initiative

I. Forewords

Clashes have occurred between Chinese and Indian garrison forces across the borders near Ladakh of late followed by five rounds of talks among commanders at the corps level.1Although both sides have agreed to break the military contact, there

are few reassuring signs that the PLA will observe the agreement. Tensions flared again on August 31 after India moved troops into the hilltops on its side of the border at Pangong Tso Lake to stop a push by Chinese forces to claim more ground. The PLA instead has reinforced infrastructure of their garrisons. This is an indicator of the PLA’s resolve to have a sustained deployment in the neighborhood of Ladakh, which is a strategic decision to aggravate the bilateral relations by persistent goading. This also implies that, as long as the border dispute is not settled, military clashes may reoccur at any moment. Prime Minister Modi and Defense Minister Rajnath Singh, in an attempt to cope with the crisis, are known to have successively visited India’s border troops. They also sought to upgrade the Indian force strength and weapon systems along the borders. The political moves reflect a constant burden on the Modi government, for a failure to diffuse the crises on the borders quickly will become an acute threat against Modi’s credit as a nationalist leader.

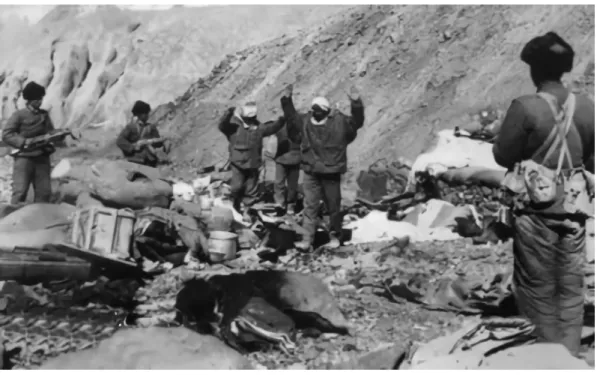

Figure 1. Indian’s Army Patrol in Sub-sector North along the Line of Actual Control with China

Source: Anath Krishnan, “Behind New Incidents, Change Dynamic along India-China Border,”

The Hindu, May 20, 2020,

<https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/news-analysis-behind-new-incidents-a-changed-dynamic-along-india-china-border/article31627397.ece>.

wide gap in perceptions,” Hindustan Times, July 24, 2020, <https://www.hindustantimes.com/ india-news/india-china-statements-on-border-talks-reflect-a-wide-gap-in-perceptions/story-vOE6w Dn9mk4zv7BvkqjGHM.html>.

The issue of China-India borders, which can be traced to the military clashes in 1962, continues as the root of discord between the two giants in Asia. Although history has witnessed several rounds of talks carried out by working teams representing the two sides, no concluding settlements have been made to date. The issue has been stalling mainly over sovereignty, the hardly forsaken prerogative over the sophisticated geographies. A modus vivendi may be in place to tone down the dispute: both India and China observe the actual control line, which is taken as the premise for steady negotiation as time passes. Unfortunately, the two sides take the disputed pieces of territory as core interests. They are inimical to each other on this issue and are emphatic of their strong will not to budge an inch. Given their relentless effort to strengthen military infrastructure and force deployment along the borders, once the demonstration of power erupts into clashes, it will impact Indo-Pacific regional security and neighboring countries may be forced into a quandary.

It will suffice to say that diplomatic means and negotiation effort are a necessity to wade through the potential difficulties in the dispute. Somehow, China-India relations and their foreign policy towards each other have proved not susceptible to regime transitions or certain rousing moments over issues of sovereignty. Nevertheless, with the changes in the strategic environment nowadays, the China-India border tension may more likely erupt into physical clashes and military operations that will deliver regional impact and move far beyond 1962.

In other words, given and despite the various institutional means—official and non-official—in place to accommodate the mismatch of strategic interests on the two sides, Beijing and New Delhi are constantly dictated by domestic politics and historical vengeance. This has not only forced policymakers concerned to take the opposing policymakers as an imaginary enemy that might exploit opportunities whenever possible, but also has contributed to commonly held scholarly viewpoints based on realism. It has been contended widely that, with the growing Chinese economy, China surely is going to seek a military presence in the Indian Ocean, which will make India uncomfortable. As it is, the vast majority of scholars on the Indian side take a cautious note toward the Chinese activities on the Indian Ocean. They tend to foresee Beijing as seeking to contain India, challenging this part of the sphere of influence held by New Delhi.

That said, despite the diplomatic effort to ease the tension that has been made, skepticism towards each other remains. Thus, the picture has not changed significantly —any triggering events sustained by historical grievance and geostrategic concern may bring about armed clashes. With the new wave of security alliances among the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia against a rising China having been weighed in, the development of China-India relations cannot be dismissed lightly, and that is the justification of this report.

II. Review of China-India Relations

Immediately after the PRC seized control of Mainland China, India was the first non-socialist state to establish a diplomatic link with Beijing. To the extent that the two governments developed a harmonious tie, mutual visits took place at the premier level between Jawaharlal Nehru and Zhou Enlai.2The year 1959, however, marked a switch of that policy attitude. Beijing sent troops into Tibet in the name of counterinsurgency, thereby uprooting the autonomous status of the Tibetan governance and taking direct control of the region. Politically, Beijing reproached, and is still reproaching, India for interfering in Chinese internal affairs. Distortion of China-India relations has existed since then.

The clashes on the border in 1962 ended with the PLA seizing Aksai Chin after two phases of battle where Beijing took the upper hand in the military engagements. Pressured by logistical support in the mountain areas and countered by the U.S., Britain, and the Soviet Union standing behind India, Beijing called a unilateral ceasefire with a retreat of its troops 20 km and a return of POWs, as well as captured weaponry. Since the actual control line between India and China was resumed and reenacted, India has had Arunachal Pradesh under its sovereign rein. Nevertheless, the psychological legacy left by the war in 1962 seems persistent, which partially explains the tension along the borders even nowadays.

Shri Ram Shama, India-China Relations (1947-1971) (New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House, 1999), pp. 32-33.

Figure 2. China-India War in 1962

Source:Jianglin Li, “‘Suppressing Rebellion in Tibet’ and the China-India Border War,” December 5, 2017, War on Tibet, <http://historicaldocs.blogspot.com/2017/12/suppressing-rebellion-in-tibet-and.html>.

This suspicion might have been relatively allayed since Deng Xiaoping came to power, when China was keen to launch its open-door policy, seeking smoother relations with its neighbors. The end of the Cold War also set a milestone. New Delhi was aware of the need to rethink its relations with the former Soviet bloc and to reconstruct its chilly relations with Beijing. A symbolic icebreaker visit was initiated by Indian Premier Rajiv Gandhi in 1988, when diplomatic tensions began to thaw.3Nevertheless, that was certainly not the case for the Indian military. Perhaps due to lessons gained in 1962, rarely has the defense establishment relaxed their caution about China’s intention. This is especially true when the comprehensive strength on the Chinese side is seen as growing. With its combat preparedness on the rise, the Indian concern about China speaks volumes.

Dilip Bobb, “Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s Visit to China Marks a New Beginning in Bilateral Relations,” India Today, January 15, 1989, <https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/cover-story/ story/19890115-prime-minister-rajiv-gandhi-visit-to-china-marks-a-new-beginning-in-bilateral-relations-815628-1989-01-15>.

In June 2003, Premier Atal Bihari Vajpayee made his state trip to Beijing, who returned the favor by indirectly recognizing Sikkim as an Indian state. A working team was set up, aimed at negotiation over the border dispute. China-India relations were even more stabilized after Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visited India in January 2005, when the two sides held strategic dialogue and inked a China-India joint statement. The two states declared a benchmark to “build a strategic and cooperative partnership for peace and prosperity.” The Agreement between the Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question also laid the foundation for stable progress of the difficult bilateral relations ahead.

Figure 3. Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping

Source: Pia Krishnankutty & Srijan Shukla, “1954 Panchsheel pact to Galwan Valley ‘violence’ — India-China relations in last 7 decades,” The Print, June 16, 2020, <https://theprint. in/diplomacy/1954-panchsheel-pact-to-galwan-valley-violence-india-china-relations-in-last-7-decades/442810/>.

After 2014, when Modi came to power, there has been an increase of news reports concerning border incidents as well as provocative remarks. Here, nationalism has to be factored into Modi’s unfriendly attitude towards Beijing and his eventual decisions to reinforce the deployments on the border. In July 2016, Beijing publicly objected

to India’s attempts to join the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). Beijing’s opposition surely soured the relations with the Modi Government. This was followed by Beijing’s interference into visa issuance to visit China for high-ranking Indian officers garrisoning on the border. India subsequently suspended the visa re-issuance to journalists with the Xinhua News Agency dispatched to India. In 2017, clashes escalated with the two sides quickening the force mobilization near the Doka La Pass along the middle part of the China-India border. The crisis was eventually resolved on the grounds that the policymakers on both sides were prudent enough to de-escalate the unexpected tension. Bilateral relations stabilized in 2018 after Premier Modi and Xi Jinping had an unofficial talk in Wuhan. No joint statement was issued. Nevertheless, the two sides made it clear to their neighbors that both were ready to negotiate over the disputed borders and maintain peace and stability in the areas concerned so that there would be durable China-India relations in the wake of the Doka La incidents.4 Strategic analysts have now voiced their doubt over the publicized intention reiterated after the Wuhan talk. As a matter of fact, India’s increasing military links to the U.S. and its security cooperation in the domain of the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, the off-and-on military skirmishes between India and Pakistan, recent tussles near Ladakh, and India’s boycotts against Chinese-made products of communication technology and cellphone software have to be factored into the strategic calculation that can be illustrated as follows.

Ankit Panda, “What’s Driving the India-China Standoff at Doklam?” The Diplomat, July 18, 2017, <https://thediplomat.com/2017/07/whats-driving-the-india-china-standoff-at-doklam/>.

Figure 4. Doka La Standoff Crisis Was Eventually Resolved on the Ground That the Policymakers on Both Sides Were Prudent Enough to De-Escalate

the Unexpected Tension

Source: Paramendra Bhagat, “Doka La Standoff: China Proved Its Point On Tibet,” August 28, 2017, Barackface, <http://democracyforum.blogspot.com/2017/08/doka-la-standoff-china-proved-its-point.html>.

III. Factor Analysis of China-India Relations

1. China-India Border Dispute

The issue of territory on the borderlines has been the focal point of the talks for several years. The talks did ensure a stable bilateral relationship, despite no significant breakthroughs. Important milestones include three agreements and one memo that set the signposts for political settlement of the border dispute. Also symbolic is the lift of the Nathula Pass between Mainland China and Sikkim to ease the trade activities on the border. It may be sensible for the two sides to show their willingness to speed up the process of negotiation against the context of China’s rise. To Beijing, a speedy

settlement of the final pieces of land in dispute with a neighboring state will contribute to anticipated China-India cooperation in all dimensions. New Delhi, on the other hand, seems to have no confidence until it expands its border troops to counter the threatening deployments on the Chinese side. Further build-ups of military airports, as well as forward command posts and more purchases of quality fighters, turn out to be the policy preference of the Indian government. To New Delhi, settlement of the disputed border means alleviation of the military threat from the north. India then will not only have more room to cope with Pakistan’s armed conflicts with its limited defense budget, but also will have more opportunities to elevate its comprehensive national strength by effectively developing domestic economies and administering basic infrastructures.

Generally speaking, although both India and China are reiterating their firm will to solve the disputed border as soon as possible, sophisticated situations at home and abroad have forced them to realize that it is impossible to solve the thorny issue in a day. The issue is in essence an intransigent one, because any promise is vulnerable to the vicissitude of the overall diplomatic environments and domestic politics on each side. They are indeed the key to China-India relations.

With Beijing’s resolve for military preparedness and with Chinese nationalism shooting high, the issue may turn even thornier. Perhaps one thing is for sure. We do not anticipate that Beijing will unconditionally forsake territorial sovereignty, or loosen its grip on the land in hand, despite the heavy burdens from sustaining its military deployments along the China-India border.

Figure 5. The Disputed Border between India and China

Source: “India-China Border Standoff Raises Military Tensions,” DW, June 2, 2020, <https:// www.dw.com/en/india-china-border-standoff-raises-military-tensions/a-53661453>.

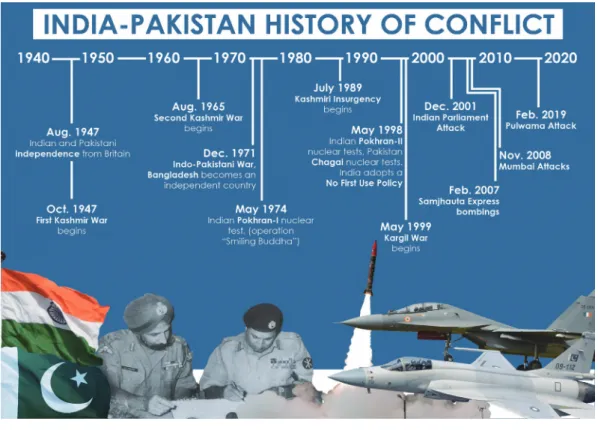

2. Indian-Pakistan Discords

During the Cold War, there existed in South Asia two pillars in confrontation— Beijing, Washington D.C., and Islamabad on the one side and New Delhi and Moscow on the other side. The situation changed after Washington became aware of the threats from China’s rise. By publicizing the “Pivot to Asia Pacific” strategy, the U.S. sought a containment policy against China, which had to be substantiated by courting India and rebuilding relations with Pakistan. The point worthy of note is that, although Pakistan actively took part in the U.S. plan to uproot the Taliban, relations between Beijing and Islamabad remain stable.

In India’s overall strategic plan, Pakistan is taken as a potential threat from the west, and China as one from the north. India is under tremendous threat if Beijing is developing the string-of-pearls strategy or the maritime silk-road blueprint through which the PLAN takes Gwadar Port, Pakistan, as the midway to launch its power projection at full capacity. That said, the closer China-Pakistan relations are, the more daunting pressure and a sense of insecurity India, who is deeply concerned about a potential two-pronged attack, will feel. It is somewhat ironic, on the other hand, to

point out that India finds it easier to improve diplomatic relations with China than with Pakistan. In this light, easier access from New Delhi to Islamabad may be via Beijing. In India’s calculation, better China-India relations may have Pakistan see the future China-Pakistan cooperation with a pinch of salt. When Beijing is not taken for granted by Islamabad, New Delhi acquires better chances to focus its attention to resolving the issue over Kashmir.5

The two sides have marked differences to settle both in terms of military confrontation and political standing on Kashmir. It is a relief to see the two sides proceed slowly towards cooperation, but there is still a long way to go when it comes to normalization of the links and effective breakthroughs.

Figure 6. India-Pakistan History of Conflict

Source: Abby Pokraka, “History of Conflict in India and Pakistan,” November 26, 2019, Center

for Arm Control and Non Proliferation,

<https://armscontrolcenter.org/history-of-conflict-in-india-and-pakistan/>.

Ayesha Tanzeem, “Tensions Between India, Pakistan Undermining Regional Alliances,” Voice

<https://www.voanews.com/east-asia-pacific/tensions-between-3. Strategic Interests of Main Powers

In spite of India claiming to be the biggest power in South Asia, the policy attitude on issues of regional security is inevitably under the influence of the main powers outside South Asia. This is most manifest in India’s arms and diplomacy, an indication of the Soviet legacy as the result of military assistance and economic aid from the Soviet Union. The effort made by India and Pakistan to test nuclear weapons in 1998 brought about U.S. sanctions. Nevertheless, when the strategic situation changed into an emphasis on global anti-terrorism in the wake of the 9/11 attack and the U.S. needed Indian and Pakistani support, the previous sanctions against them were lifted. President George W. Bush for instance inked a ten-year agreement to begin U.S.-Indian military cooperation, which was substantiated by granting a nuclear contract for civilian use and by building deeper contact between the Indian and U.S. forces.

The U.S. trend to seek Indian support was furthered by President Barrack Obama, who entered India into the U.S. rebalancing strategic plan. From the so-called “Look East Policy” to the “Act East Policy”, India was encouraged to take physical part in the regional affairs in East Asia, serving a linking role to bridge South Asia and Southeast Asia. Obama’s Rebalancing strategy has now been extended into the Indo-Pacific strategy by President Trump, who recommends the view that Japan, Australia, and India ally with the U.S. and each other to check China’s Belt and Road Initiative as a means to sustain the U.S. leadership in the international field. Trump’s announcement, conceptualized as a quadrilateral framework, may not be a wishful thinking, given the rosy picture of advancements in the Indian economies, political status, and military capabilities.6 Bilateral cooperation with India currently performed includes Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam.

Among various cooperation means, the most effective measures to counter China’s rise may be preparedness upgrades and arms exports. One of the striking examples is the U.S. permission to sell India the catapult system on aircraft carriers in an agreement to cooperate on defense/technology. The agreement was signed by U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis when he visited India in September 2018. India is

looking forward to the U.S. assistance to resist the Chinese threat. Perhaps quite predictably, India remains prudent. It leaves considerable maneuvering room to the question whether India will be devoted to the role the U.S. wishes it to play as a powerful check against China in the overall Indo-Pacific strategy.

Figure 7. U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj and Indian Defense Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in New Delhi in September, 2018 Source: Pradip R. Sagar, “US high-powered delegation to visit India in January,” The Week,

December 20, 2018, <https://www.theweek.in/news/india/2018/12/20/US-high-powered-delegation-to-visit-India-in-January.html>.

4. Competition over Trade, Economics, and Resources

China stared its reforms and open-door policy in the early 1980s. In contrast, India started to follow the Chinese model for economic development as late as the early 1990s. Yet, there had been no significant competition at the beginning stage because the two sides have different political systems and economic/trade infrastructures. Saurabh Todi, “India Gets Serious About the Pacific Can India walk the talk on the Indo-Pacific?” The Diplomat, December 18, 2019, <https://thediplomat.com/2019/12/india-gets-serious-about-the-indo-pacific/>.

Nevertheless, with the rapid rise of foreign trade and Beijing’s keen effort of global investment, as well as resource exploitations, tough competition between the two giant economies over resources came into being when they sought to take the lead in the manufacturing sector in the world market. The two countries are boastful of a sizeable population—India has a population of 1.35 billion whereas China has 1.4 billion. Nevertheless, China’s GDP (gross domestic product) is five times higher than India’s. The objective of the U.S. trade war against China is straightforward. President Trump hopes to evacuate all the U.S. manufacturing sectors from Mainland China. To achieve this, Trump is helping those American assembly lines to move into India and elsewhere. It is anticipated that the competitive relations for foreign investment between India and China will be intensified. India possesses quality software design, a choice service sector, and high-tech talents in the overall industry value chain of the world. In addition, it is basically an English-speaking country. All these are India’s advantages to compete with China in economic activities. Aside from the diplomatic tension and disputed borders mentioned above, the current conditions for trade exchange and economic interdependence are filled with paradoxes, and they look sour. The Covid-19 pandemic has added further weight to the anti-Chinese voice, and it is expected that trade embargoes and business competition will have an appreciable rise. It is hard to find the exact link between cause and effect, however, superficially, market competition and trade embargoes seem to be the result of deteriorating relations between India and China. Nevertheless, the strategic layout for future resources and business competition will have a feedback effect, intentionally or unintentionally, on the China-India relations.

Figure 8. Indians Hold Funerals for Soldiers Killed at China Border, Burn Portraits of Xi

Source: “Indians hold funerals for soldiers killed at China border, burn portraits of Xi,” Gulf

Today, June 18, 2020,

<https://www.gulftoday.ae/news/2020/06/18/indians-hold-funerals-for-soldiers-killed-at-china-border-burn-portraits-of-xi>.

IV. Impact Analysis of China-India Relations on the Indo-Pacific Region

India used to be noted for its closer relations with Soviet Union and a non-align-ment foreign-policy approach to China and the U.S. with a view to a dynamic balance of power in the international stage during the Cold War. Ever since Beijing’s dramatic effort of expanding its military preparedness and the high-profile Belt and Road Initia-tive set into motion, however, India feels its breathing space is under serious threat in terms of the intransigent issues of territorial borders with China and freedom of movement on the Indian Ocean. That said, it would be a wonder if India and China still have their strategic interest conventionally intact. Both are sure to see the other as the strategic rival. Frequent protests against each other are expected for now and for the foreseeable future. India’s concern is based upon the understanding that, if the Chinese troops consolidate their expansion and Beijing dictates the international order, China will become assertive in dealing with the border issues. It may be likely that China will take the chance and regain Arunachal Pradesh. Taken together, it makes sense for India to change the conventional non-alignment tone, seeking to win support from the external powers and neighboring states. At least, India ought not to placeitself on a losing ground in the ongoing confrontation with China.

More to the point in this analysis is that the value of India lies in the U.S. strategic layout in recent decades. There have been quite fruitful outcomes from the US-Indian military cooperation, especially after the publication of the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy. In arms transfer, the U.S. sales to India include cargo aircraft, maritime patrol aircraft, and attack helicopters. India currently is seeking a U.S. agreement to have hi-tech transfer so that it can redevelop its own defense industry. In 2019, President Trump visited India, where he received a warm welcome. This was followed by the announcement that Indian troops were invited to join the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC). India in turn relaxed its suspicion and invited Australia to join the annual Exercise Malabar. The part Australia played in the exercise means a lot. It indicates that, in addition to the participating members, such as the U.S. and Japan, the quadrilateral security-alliance framework consisting of the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia is emerging and becoming stable. In contrast, the atmosphere of China-India relations after the Wuhan meeting in 2018 seems to have gone sour. Indian civic sectors recently started campaigns for embargoes against Chinese goods and Chinese-designed APPs. Premier Modi is reported to have shut down his personal homepage on Weibo. We still need to observe closer whether India is determined to stand behind the U.S., and the impact of the quadrilateral framework on the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy.

Figure 9. India, U.S., and Japan in Malabar Naval Exercise 2019

Source: “Sdang ka Malabar Naval Exercise hapyrdi ka India, US wa Japan,” Wyrta, September 27, 2019, <https://wyrta.com/sdang-ka-malabar-naval-exercise-hapyrdi-ka-india-us-wa-japan/>.

Predictably, as to the question of how India integrates itself into the quadrilateral security framework with a view to deeper cooperation with states in the Indo-Pacific region, the calculating factors here refer to the U.S.-China trade war, the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic, and Beijing’s assertiveness in its foreign relations with other countries. Some constructive elements that may soft-pedal the deteriorating tendency caused by the tensions include cooperative dimensions of the China-India relations. These refer to some joint activities looking for an overall trade cooperation and some small-scale anti-terrorist drills on the China-India border. Internationally, India is a member state within the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), a talk shop masterminded by China. India is also a member state of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, where it has been upgraded from an observer state to an official one that is qualified to join security talks and anti-terrorist exercises—with Beijing behind the scene. Both India and China also are key members of the BRIC countries. In other words, there are several institutional channels and regime-type access points to facilitate communication between India and China. These all constitute a brake on crisis escalation into possible military clashes despite seething quarrels over the borders and mismatches of strategic interests.

The findings of this observation are as follows. China-India relations could be kept stable in a longer term, because, aside from the intransigent issue over the territory, the main cause of overall military clashes remains under control. The issue here is that, as long as either side of the troops refuses to retreat to the Actual Control Line, there will be a reason for tensions to flare up again. From the international perspective, when India does not voice its traditional non-alignment policy, but instead reinforces its security relations within the quadrilateral framework—the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia—this means that India will be involved in the issues in the East China Sea, Taiwan Strait, and South China Sea. Given the above areas all involve Beijing, India will be in an even more confrontational and conflictual position against China, a tendency that Beijing will try its best to avoid. Ironically enough, India may be the easiest one, among the four players, to be dissuaded from the security-related quadrilateral framework. It is highly likely that the suggested quadrilateral framework seeking security reassurance turns into a talk shop, if India is happy with the instant treats offered by Beijing and walks away.

V. Conclusions

A few concluding notes are in order here.

First, the locus of all of the Indo-Pacific region lies in the dynamic of U.S.-China relations. As long as Washington continues with its policy to counter China, the quadrilateral security framework consisting of the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia will increase in shape as a checking mechanism to assertive behavior and expansive activities on the Chinese side.

Second, seeking an immediate settlement of the border disputes with Beijing seems not to be the priority in the eye of New Delhi from the traditional views of Indian national interests. There are, in contrast, foreseeable benefits in prospect for the two Asian giants if the two sides can be engaged in the status quo, keeping those clashes in the background. With the rising strategic confrontation between Beijing and Washington and with the thriving cooperation between Washington and New Delhi, however, uncertainties emerge. That said, strategic interests gained from China-India relations and those from the quadrilateral security framework, where India is forced into the center, will be sensitively conditioned by the trends of the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy.

Third, the crux here to notice is that the Chinese expansive act on military preparedness and the potential clashes between Beijing and Washington as the result of this wave of the trade war will force India to join the U.S. if New Deli does not want to look weaker in future clashes over the China-India borderlines. A lesson that was not lost to history in 1962 is that one of the reasons that Beijing decided to back down rather than exploiting its victory was the U.S. promise to give India military assistance. With this, it may be not too much farfetched for us to argue that the Beijing will be reserved on the decision to fight a war with India in the context of closer U.S.-Indian relations and the quadrilateral security framework with the U.S. as the backseat driver. Also with these backdrops, Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative is stepping into a trough, seriously caught by an economic recession inside Mainland China, as well as being deeply trapped by participating countries heavy debts. Therefore, it is time for India not only to welcome assistance from the U.S., Japan, and Australia but also reconsider its constructive role in Indo-Pacific region. Only when New Delhi is capable of having the Indian voice heard through the region via its foreign policy and economic activities checking the Chinese expansive acts, can international society recognize India as key pillar of security in Indo-Pacific and South Asia.