Chinese inpatients’ subjective experiences of the helping process as

viewed through examination of a nurses’ focused, structured therapy

group

Fei-Hsiu Hsiao

RN, PhDAssistant Professor, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

Shu-Mei Lin

RN, DipNNursing Manager, Acute Psychiatric Unit, Taipei City Psychiatric Centre, Taipei, Taiwan

Hsiao-Yuan Liao

RN, DipNSenior Psychiatric Nurse, Acute Psychiatric Unit, Taipei City Psychiatric Centre, Taipei, Taiwan

Mei-Chih Lai

RN, DipNPsychiatric Nurse, Acute Psychiatric Unit, Taipei City Psychiatric Centre, Taipei, Taiwan

Submitted for publication: 25 February 2004 Accepted for publication: 20 May 2004

Correspondence: Fei-Hsiu Hsiao Assistant Professor College of Nursing Taipei Medical University No. 250, Wu-Hsing Street Taipei 110

Taiwan

Telephone: 886 2 27361661 (ext. 6313) E-mail: hsiaofei@tmu.edu.tw

H S I A O F - H , L I N S - M , L I A O H - Y & L A I M - C ( 2 0 0 4 )

H S I A O F - H , L I N S - M , L I A O H - Y & L A I M - C ( 2 0 0 4 ) Journal of Clinical Nursing

13, 886–894

Chinese inpatients’ subjective experiences of the helping process as viewed through examination of a nurses’ focused, structured therapy group

Aims and objectives. This study examined Chinese inpatients’ views on what aspects of a nurses’ focused, structured therapy group worked to help their psychological and interpersonal problems and what traditional Chinese cultural values influenced their viewpoints.

Methods. Nine Chinese inpatients with mental illness participated in the four-session nurses’ focused, structured therapy group. After they completed the last session of therapy, they were invited to participate in a structured interview and a semi-struc-tured interview regarding their perceptions of the change mechanisms in nurses’ focused, structured group therapy. The semi-structured interviews were recorded and transcribed to be further analysed according to the principal of content analysis. Results. The results indicate that (i) all patients believed that a nurses’ focused, structured group psychotherapy enhanced their interpersonal learning and improved the quality of their lives, (ii) traditional Chinese cultural values – those emphasizing the importance of maintaining harmonious interpersonal relationships – influenced the Chinese inpatients’ expression of negative emotions in the group and their motivation on interpersonal learning.

Conclusion. In conclusion, we found that transcultural modification for applying Western group psychotherapy in Chinese culture was needed. The modification included establishing a ‘pseudo-kin’ or ‘own people’ relationship among group members and the therapists, organizing warm-up exercises and structured activities, applying projective methods and focusing on the issues of interpersonal relationships and interpersonal problems.

Relevance to clinical practice. The small sample size of the present study raises questions regarding how representative the views of the sample are with respect to the

majority of Chinese inpatients. Nevertheless, this preliminary study revealed a cultural aspect in nursing training that requires significant consideration in order to work effectively with Chinese patients.

Key words: Chinese culture, group therapy, mental illness, nursing

Introduction

A focused, structured therapy group which provides struc-tured activities and support is considered an effective therapy for severely psychotic inpatients (Strassberg et al., 1975; May, 1976; Yalom, 1983). The viewpoint of inpatients on the value of group psychotherapy has been the focus of research to develop effective strategies which meet inpatients’ needs in therapy group. Yalom’s (1975) conceptualization of the treatment mechanism of group psychotherapy into 12 therapeutic factors was used to study the curative process. Yalom’s 12 therapeutic factors include altruism, cohesive-ness, universality, interpersonal learning (input), interper-sonal learning (output), guidance, catharsis, identification, family re-enactment, self-understanding, instillation of hope and existential factors. Over the past three decades, many studies have been conducted on North American and European populations regarding what aspects of the curative process in group psychotherapy that inpatients perceive to be efficacious (Maxmen, 1973; Butler & Fuhriman, 1980; Schaffer & Dreyer, 1982; Marcovitz & Smith, 1983; Leszcz et al., 1985; Kahn et al., 1986; Kapur et al., 1988; Colijn et al., 1991). These studies indicated that, although patients rated differently, they had similar perceptions of the import-ant therapeutic factors, including cohesion, hope, catharsis, existential factors, self-understanding, altruism, universality, advice, interpersonal learning-output and vicarious learning. The study by Leszcz et al. (1985) found that inpatients reported they learned more about their relationships with others and their interpersonal problems through the group’s interaction. This finding supports Yalom’s (1983) suggestion that inpatient therapy group improves interpersonal relation-ships and interpersonal learning because hospitalized patients usually experience interpersonal problems. Inpatient therapy group realizes two essential benefits: (i) patients are provided with an opportunity to learn social skills to deal with interpersonal problems; and (ii) patients interact more with other patients during their hospitalization, thus helping to decrease their sense of isolation and loneliness.

Psychotic patients placed less value on the higher-level talking group than the alternative group, which involved art imagery, movement and other modalities not requiring much

verbal interaction (Leszcz et al., 1985). Because they experi-enced threatening situations, some patients withdrew from participating in the group. Strassberg et al. (1975) argued that forced self-disclosure through verbal expression might be stressful and harmful for psychotic patients. It has been a challenge to develop inpatient groups that are productive without over-stimulating the patients (Spielaman, 1975; Houlihan, 1977; Gunn, 1978). Yalom (1983) organized a focused, structured therapy group which was highly struc-tured and less intensely interactive. This type of group can meet the needs of more regressed, psychotic and lower-functioning patients through structured activity. In his experience, patients found this type of group to be most effective. Consistent with this finding, Kaplan (1988) also documented that severely disturbed patients responded better in a focused, structured psychotherapy groups than in an unstructured psychotherapy group. Remocker and Storch (1992) pointed out that, in addition to severely psychotic patients, a focused, structured group psychotherapy was applicable to patients with different levels of functioning because they could learn about themselves and could become more skilled at interacting with other people through enjoyable structured activities.

For the Chinese, Confucianism plays a vital role in determining the appropriateness of interpersonal relation-ships (Hwang, 2000). This classification of interpersonal relationships influences the extent to which Chinese people’s emotions and personal matters will be revealed. A ‘pseudo-kin’ or ‘own people’ relationship helps the establishment of good rapport between Chinese patients and the therapist (Tseng et al., 1995). Cheung and Sun (2001) found that such relationships could help to develop universality and self-disclosure in self-help groups.

Over the past three decades, many studies have been conducted primarily on the North American and European population regarding what aspects of the curative process in group therapy, inpatients perceive to be efficacious. How-ever, very few studies exist of inpatients’ experiences of the change mechanisms in inpatient psychotherapy groups con-ducted at acute psychiatric units in Chinese societies. This study aimed to examine Chinese inpatients’ perceptions of helpful therapeutic factors and their impressions of what

aspects of a nurses’ focused, structured therapy group worked to help their psychological and interpersonal problems.

Methods

The study was designed using a descriptive study. The study includes a structured interview concerning which therapeutic factors are perceived to be helpful by Chinese inpatients, followed by a semi-structured interview regarding their interpretations of the change mechanisms in lower-level group therapy. The quantitative data provide a picture of how much Chinese inpatients value therapeutic factors. The qualitative method offers to elicit more fully the complexity of their experiences of the change mechanisms in inpatient psychotherapy groups within an acute psychiatric unit. Therefore, a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches contributes to a deeper and broader understand-ing of Chinese inpatients’ perceptions of change mechanisms. The study was conducted in a 33-bed acute psychiatric unit in a public psychiatric hospital.

Subjects

Nine patients who were not severely agitated were invited to participate in the nurses’ focused, structured therapy group. Six of nine patients were female. The average age of the patients was 36 years with a range of 19–51 years (mean ¼ 36.89, SD ¼ 10.80). Six patients’ problems were diagnosed as schizophrenia, while two patients’ problems were diagnosed as bipolar disorder and affective disorder. Two of the nine patients were more regressed, psychotic, and less verbally communicative. Only one was a college graduate, while the rest were graduates of junior or senior high schools. The majority of subjects (six of eight) were unemployed.

The contents of the nurses’ focused, structured group psychotherapy

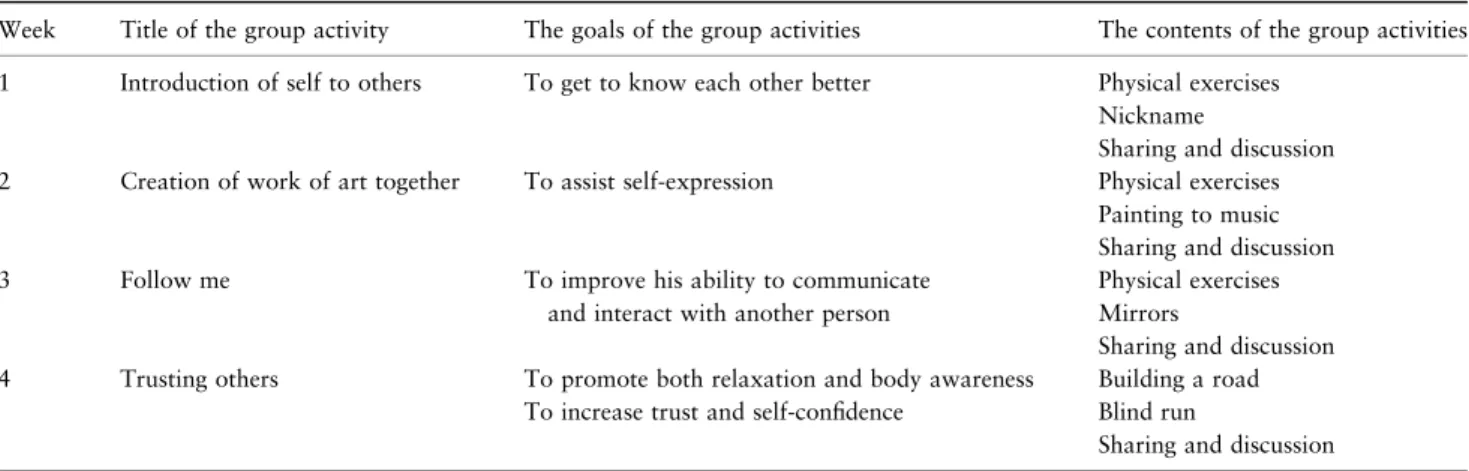

For the present study, the nurses’ focused, structured group psychotherapy consisted of four sessions of structured group activities, with each session lasting for 50 minutes weekly. The main aims of the group activities were to enhance the patients’ self-awareness and self-expression, their interaction with other group members, and their interpersonal learning. The themes of the four sessions are ‘Introduction of self to others,’ ‘Creation of work of art together,’ ‘Follow me,’ and ‘Trusting others.’ The group activities – including ‘Nick-name,’ ‘Painting to music,’ ‘Mirrors,’ ‘Building a road,’ and ‘Blind run’ – were selected from the book Action Speaks Louder by Remocker and Storch (1992). The structure of each group session was based on Yalom’s (1983) format, including orientation and preparation of patients, warm-up exercises, structured activities, and review and evaluation of the session. The objectives and contents of each session are listed in Table 1.

Instruments

The Chinese version of Yalom’s therapeutic factor question-naire was translated by the psychiatric and psychological expertise of the Chinese Association of Group Psychotherapy. It took one year to accomplish the translation. However, there was no test for the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Yalom’s therapeutic factor questionnaire. Twenty-four items derived from the 60-item original version were selected by the psychiatric and psychological expertise based on their views of the most representable and comprehensible items for psychotic and low-level functioning inpatients who were currently influenced by disturbed symptoms. The

Table 1 The contents of the group psychotherapy for the present study

Week Title of the group activity The goals of the group activities The contents of the group activities

1 Introduction of self to others To get to know each other better Physical exercises

Nickname

Sharing and discussion

2 Creation of work of art together To assist self-expression Physical exercises

Painting to music Sharing and discussion

3 Follow me To improve his ability to communicate

and interact with another person

Physical exercises Mirrors

Sharing and discussion

4 Trusting others To promote both relaxation and body awareness

To increase trust and self-confidence

Building a road Blind run

24-item Chinese version of Yalom’s therapeutic factor questionnaire, which consists of two items for each category of the 12 therapeutic factors, was used to collect the data regarding whether or not patients perceived the therapeutic factors of the lower-level group therapy to be helpful.

Open-end questions were used in an interview guide (Table 2) to detail the information about why the patients valued certain therapeutic factors as the most and least helpful and to explore what other aspects of the group worked to help their psychological and interpersonal prob-lems.

Data collection

Permission for the study required the approval of the unit manager and the patients’ primary medical practitioners before approaching the patients. The researcher explained the purpose of the study to the patients, and then they were invited to be participants. They were informed by the researcher that they could withdraw from their participation in the study at any time and they could choose not to respond to the interview questions if they did not want to. In addition, they were also informed of the procedures to be adopted to ensure confidentiality of the data they provided. The proce-dures included: (i) data were identified by code without any participant’s name, address and other identifying details; (ii) only the researcher could access the data in order to analyse and interpret findings; and (iii) hard copies of information were kept confidentially by the researcher in the present study. They were asked to give their consent before the interview began.

The researcher (the first author) asked each patient for his or her available time to conduct the interview when the last session of group therapy was completed. During the inter-views, the subjects were first asked to rank each item of the 24-item Chinese version of Yalom’s therapeutic factor questionnaire. A semi-structured interview was then carried

out. A semi-structured interview was orally performed in Mandarin and was conducted by the principal researcher, an outsider to the therapeutic team. The Mandarin-speaking principal researcher has 10 years of experience in conducting interviews with Chinese patients in Mandarin and of trans-lating Chinese transcriptions into English. To ensure data quality, the translation of the transcription conducted by the principal researcher was given to another bilingual researcher for review to ensure its correctness.

Data analysis

A rank ordering of 12 therapeutic factors was obtain through the rated mean score on 4-point Likert scales (Kahn et al., 1986). Each item of the questionnaire was typed on a 3 · 5 cm card. The subjects were asked to rank each item by placing each card into four piles labelled: the most helpful (scored as 4), helpful (3), less helpful (2) and least helpful (1). The rank of the 12 therapeutic factors was obtained by counting the mean rank of each factor rated by nine patients. The higher rank indicated the more important therapeutic factor in the group therapy. SPSS/PC package was used to analyse the quantitative data using descriptive statistics (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The interview data were separated into three files: tran-script file, personal file and analytical file. The trantran-script file consists of the information given by the patients in inter-views. The personal file describes the researcher’s reflection on the interview, including the informants’ behaviours and the researcher’s description of the process in the interview. The analytical file includes the information about the issues and concepts emerging from the interview. Content analysis was carried out to examine the qualitative data analysis for common domains and themes (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Four of the authors (FHH, SML, HYL, MCL) independently reviewed verbatim transcripts to develop a coding scheme. Thirty per cent of interview materials were coded according

Table 2 Interview guide

You have responded your view of how much you value these factors on the questionnaire. I will be asking you question about why you value this/these therapeutic factors as the most and least helpful and about what other factors you think make the group work effectively. The information you provide helps us to provide a better group therapy for other people who experience distress.

1 You have valued this/these therapeutic factors as the most helpful. Can you tell me about why you perceive it/them as most helpful? 2 I have noted that you have valued this/these therapeutic factors as the least helpful. Can you tell me what leads you to perceive these

therapeutic factors as the least helpful factors?

3 Now I need you to recall your experiences of participating all sessions of group therapy. What do you think is the most impressive and interesting event occurring in the group? For example, which group activity you think is most interesting one, or what was talked in the group you remember most? Can you tell me why you think them as the most impressive and interesting event?

4 In the last I need you to tell me what nurses can do to improve group treatment? For example, how to make group activity more fun, how to make people to feel comfortable to express themselves?

to the definitions of Yalom’s 12 therapeutic factors. The patients’ stories were also examined for any emergent structure (general classes of information and subclasses). Each class and subclass (e.g. interpersonal learning: social interactions and social skills) was defined as concretely as possible so that it could be reliably communicated to independent scorers. All the categories emerging from the coding procedure were organized into a coding scheme. Reliability for (i) detecting codable material and (ii) applying the derived coding scheme was checked using an independent scorer using randomly selected passages from the total pool of materials. Disagreements were used to refine the coding scheme and the definitions of classes and subclasses. Post-refinement, the coding scheme reliability was checked with a third independent rater as before. All transcripts were then coded and categorized to identify major domains and thematic contents. Four researchers discussed all emerging issues until agreement was reached.

Findings and discussions

The quantitative data: a rank ordering of 12 therapeutic factors rated by Chinese inpatients

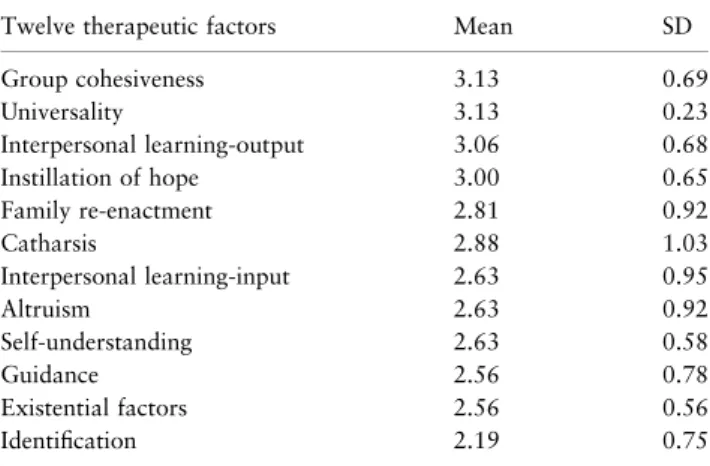

Table 3 summarizes the mean and standard deviations of the rated 12 therapeutic factors. The results were based on eight subjects because one subject could not comprehend the meaning of the questionnaire due to the influence of his psychotic symptoms. According to the ranked ordering of the 12 therapeutic factors, the four most helpful factors valued by inpatients were group cohesiveness, universality, interpersonal learning-output and instillation of hope, while identification was considered as the least helpful therapeutic factor.

The most helpful factor valued by the patients was group cohesiveness. Similarly, cohesion was particularly valued by Western inpatients in other studies (Maxmen, 1973; Butler & Fuhriman, 1980; Kapur et al., 1988). Nevertheless, while catharsis was not highly valued by Chinese patients in this study; the previous studies (Schaffer & Dreyer, 1982; Marcovitz & Smith, 1983; Leszcz et al., 1985; Colijn et al., 1991) indicated that catharsis was highly prized by Western inpatients.

The qualitative data: the inpatients’ subjective experiences of the helping process in therapy group

In a semi-structured interview, all patients reported that they benefited from participating in the nurses’ focused, structured group psychotherapy. The analysis yielded three domains that included 10 themes (Table 4). The three domains were: (i) interpersonal learning, (ii) catharsis and (iii) installation of hope. These domains represent the three main therapeutic factors identified by Yalom (1975). The themes illustrate how these therapeutic factors worked to help Chinese inpatients’ psychological and interpersonal problems.

Domain 1: interpersonal learning

The experience of interpersonal learning was the most common issue shared among subjects. This domain included five themes: (i) enhancing the patients’ social interactions, (ii) improving the patients’ social skills, (iii) the impact of traditional Chinese cultural values on interpersonal learning,

Table 3 Mean values and standard deviations (SD) for ratings of 12 therapeutic factors valued by eight inpatients

Twelve therapeutic factors Mean SD

Group cohesiveness 3.13 0.69 Universality 3.13 0.23 Interpersonal learning-output 3.06 0.68 Instillation of hope 3.00 0.65 Family re-enactment 2.81 0.92 Catharsis 2.88 1.03 Interpersonal learning-input 2.63 0.95 Altruism 2.63 0.92 Self-understanding 2.63 0.58 Guidance 2.56 0.78 Existential factors 2.56 0.56 Identification 2.19 0.75

Table 4 Domains and themes identified from interviews Domain 1: interpersonal learning

Enhancing the patients’ social interactions Improving the patients’ social skills

The impacts of traditional Chinese cultural values on interpersonal learning

The development of cohesion enhancing interpersonal learning Interpersonal learning and projective method enhancing

self-understanding Domain 2: catharsis

Projective methods helping to express distress

The impact of traditional Chinese cultural values on expression of negative emotions

The development of family cohesion enhancing to express negative emotions

Domain 3: installation of hope Increasing the positive view of self Establishing the positive meaning of the life

(iv) the development of cohesion enhancing interpersonal learning and (v) interpersonal learning and projective method enhancing self-understanding.

Enhancing the patients’ social interactions

The present study illustrated that a focused, structured ther-apy group in an acute psychiatric unit could contribute to decrease inpatients’ sense of isolation, to increase their awareness of interpersonal environments and to establish the patients’ positive experiences of group psychotherapy. Some examples are described below:

I often stay at home alone and seldom have an opportunity to approach others except being a volunteer. It is very hard for me to make the first move. Through participating in the group, I can get to know other people….

The group provides me with an opportunity to approach others. Otherwise, I am usually alone, listening to music alone, doing my own thing alone. In the group, I get to know and understand other people like Ping.

Improving the patients’ social skills

The exchange of feedback and observation of group mem-bers’ behaviors were reported by the inpatients to be helpful for improving their social skills. Here are transcript examples of the findings:

We learned from people when interacting with others in the group. When we did not speak considerably, people got upset. People’s negative responses to our behaviour could help us to do better. Through this, we learned how to get along well with others and, subsequently, we could change our negative ‘custom.’

Lin is a soft person while I become agitated easily. When people talked about my weakness, I felt angry and then I would fight back. Nevertheless, when they said sorry to me, I felt sorry too and I realized that I also made mistakes. Through this, I tried to change my agitated temper.

The impact of traditional Chinese cultural values on interpersonal learning

Chinese society’s orientation towards interpersonal relations might lead Chinese patients to be more interested in interpersonal relations and interpersonal learning. In the book entitled Culture and Self: Asian and Western Per-spectives (Marsella et al., 1985), Hsu identified the differ-ence between the Asian concept of ren and the Western concept of personality. Hsu pointed out that the Chinese concept of ren (personage) emphasizes an individual embedded in a social network. This is in contrast to the individual self of Western culture emphasizing an

individ-ual’s autonomy. The Chinese self could be perceived as the relational self because Chinese people pay great attention to the existence of others (Hwang, 2000). The result indicated that traditional Chinese culture that places great import-ance on harmonious interpersonal relationships influenced the patients to value highly help in learning to socialize. One patient said that:

Through participating in the group, I can get to know many people. There is a Chinese saying that ‘if three of us are walking together, at least one of the other two is good enough to be my teacher.’ I can learn many things through knowing many people. When I get to know other people better, they can become my confidant. What I learn in the group can be applied in daily life at home….

The development of cohesion enhancing interpersonal learning

The results showed that the cohesion of the nurses’ focused, structured group enhanced the emergence of interpersonal learning. All nine patients thought that the atmosphere of the nurses’ focused, structured group was genuine, harmonious, fun and cooperative. This atmosphere helped to foster the development of social cohesion in the group. This is because the nurses’ group is fun and less threatening to the harmo-nious relationship in the group. Some examples are described below:

People on the outside are tricky while people here are genuine. I feel good to be with them in the group.

How do you feel when your brothers and sisters blame you? Here in the group no one attacks on you and everyone in the group pays attention to what you are talking about.

In the group we know each other and have a great fun. It is happy for us to play together. Everyone in the group is cooperative.

Interpersonal learning and projective method enhancing self-understanding

The previous studies (Fuhriman & Butler, 1983; Leszcz et al., 1985) attributed inpatients’ low value of self-understanding to the time limitation on self-exploration. Nevertheless, in the present study, the patients reported that through presenting and sharing their drawing products in the group, they could get a better understanding of themselves and other people without feeling threatened. The results found that interpersonal learning was associ-ated with the development of self-understanding. One patient reported that she learned how group members thought of her and then she discovered her unknown self from the group members’ feedback:

Other people said to me that I was an optimistic and romantic person. I think that I am an optimistic person but not a romantic person. They thought that I was romantic because I liked things red in color, which is a bright color. But for me, the color red makes me feel peaceful. I do not know what to say. Rather, I just like red which makes me feel good. People observe others carefully. They can find some part of me that I am not aware of.

Domain 2: catharsis

Catharsis demonstrated that the group activities relieved the patients’ psychological distress. This domain included three themes: (i) projective methods helping to express distress, (ii) the impact of traditional Chinese cultural values on expression of negative emotions, and (iii) the develop-ment of family cohesion enhancing to express negative emotions.

Projective methods helping to express distress

Five patients reported that the projective methods, such as drawing and painting, could contribute to a greater expression of their deepest thoughts, negative emotions, and insights. This result is consistent with the results of the studies conducted in Western societies (Case & Dalley, 1992; Waller, 1993; Brooke, 1995; Tate & Longo, 2002). The example below described that through drawing a patient expressed her suffering from her traditional Chinese woman’s role in taking care of her family without meeting her own needs:

When I was drawing, I could let my inside feelings out. I drew skipping music notes, mountain, sun, water, fishes swimming in water, a house, a hill, and smoke from the house where someone was cooking…. What I drew was reflected to what I thought when I listened to music. I felt carefree when I listened to music.

The Researcher asked: Can you not feel carefree in your life? The patient answered: I have a family. I cannot be carefree and cannot do what I want to do. I have my children to take care of. I have not felt carefree for a long time.

The impact of traditional Chinese cultural values on expression of negative emotions

The results indicated that Chinese values emphasizing har-mony might influence patients not to express their negative emotions. Devan (2001) also found that Chinese people’s cultural fears of expressing their psychological distress in public influenced them to experience a catharsis of their distress within a group. He stated that compared with British/ American groups, Chinese group members had more

difficulty in disclosing themselves in groups. In the present study, one patient reported that:

They all said that I was an active person and I was open. I thought that to get along with people maintaining harmony was the most important thing. People might get upset if I said something that they were not happy with.

The development of family cohesion enhancing to express negative emotions

The results showed that Confucianism’s classification of interpersonal relationships consistently influence the extent to which Chinese people’s personal and family matters would be revealed. Three patients described that a ‘pseudo-kin’ or ‘own people’ relationship helps to establish good rapport between group members and the therapist. Such relationships could help to develop self-disclosure in groups. The result suggested that developing ‘family’ cohesion was a prerequisite for Chinese patients to feel comfortable to express their distress. Some examples are described below:

I regarded them as my family. Yu was like elder sister. I talked about the things held in my mind. Our happiness and sadness were shared in the group.

…Yu is like my sister taking care of me. I always stay next to her in the group.

The Chinese cultural value’s emphasis on maintaining harmonious relationships and the Chinese classification of levels of relationships were found to influence Chinese inpatients to express their negative emotions and reveal themselves to others in the group. This finding may reflect Yang’s (1987) argument. He stated that Chinese people’s classifications of different levels of intimacy in social relationships determine to what extent emotions will be revealed. Yang illustrates that social relations in Chinese society are divided into three levels of closeness or intimacy. The closest level refers to relations with family and close friends; at this level emotions can be revealed based on unconditional trust. The next most distant level involves relations with distant family and friends; emotions in these relationships are infrequently and carefully expressed. The least close level involves relations with strangers where inner feelings are not revealed. The present study and the previous studies (Tseng et al., 1995; Cheung & Sun, 2001) suggest that the creation of a ‘pseudo-kin’ relationship and the development of ‘family’ cohesion in the group could help enhance the occurrence of catharsis in group therapy among Chinese patients.

Domain 3: installation of hope

Installation of hope illustrated that the group activities helped the patients to have a positive view on self and the world. The results of the present study and the previous studies (Yalom, 1983; Leszcz et al., 1985; Kahn, 1986) suggest that an instillation of hope was needed to provide encouragement for inpatients because they often experienced demoralization, worthlessness, and hopelessness. This domain included two themes: (i) increasing the positive view of self and (ii) establishing the positive meaning of life.

Increasing the positive view of self

The patients’ sense of self-confidence was built up through uncovering their abilities to be with strangers, to complete drawings, and to remember things. For example, one patient reported that:

Once the nurse prepared 25 things and asked us to remember them. You know I could remember 21 things. I was the best among the group. I felt proud of myself. My capacity to remember things has not deteriorated even though my intellect may have deteriorated since getting older.

Establishing the positive meaning of the life

The present study indicates that structured group activities contribute to the patients’ positive view of their lives, and the outcomes of enabling empowerment. For example, one patient reported that:

Each group activity is always novel. These two nurses organize novel and interesting activities for us. It is fun to participate in every group activity. The activities help our psychiatric patients to be away from the disturbances in our minds. Participating in the group activities makes us feel that life is still beautiful, preventing us from hurting ourselves. Life is fulfilled with novelty due to participating in the group. In addition, it makes me feel that there is a good side of life. Though it is just a small activity its effect is remarkable. Speaking this reminds me of a song: ‘life is like a basketful of flowers.’ Participating in the group installs power into my life.

Conclusions

The small sample size of the present study raises questions about how representative the views of the sample are with respect to the majority of Chinese inpatients. Nevertheless, this preliminary study contributes to providing information about transcultural modification for applying Western group psychotherapy in Chinese culture. According to the results of the present study, the modification may include establishing a ‘pseudo-kin’ or ‘own people’ relationship among group

members and the therapists, organizing structured activities, applying projective methods, and focusing on the issues of interpersonal relationships and interpersonal problems. Fur-ther studies need to (i) include a bigger sample and Chinese patients from China, Hong Kong and overseas Chinese, (ii) include different types of groups, and (iii) examine Chinese patients’ and Western patients’ interpretations of change mechanisms for cross-cultural comparison.

Contributions

Study design: FHH; data analysis: FHH, SML, HYL, MCL; manuscript preparation: FHH, SML, HYL, MCL.

References

Brooke S.L. (1995) Art therapy: an approach to working with sexual abuse survivors. Art in Psychotherapy 22, 447–466.

Butler T. & Fuhriman A. (1980) Patient perspective on curative process. A comparison of day treatment and out-patient psy-chotherapy groups. Small Group Behavior 11, 371–388. Case C. & Dalley T. (1992) The Handbook of Art Therapy.

Tavi-stock, London.

Cheung S.K. & Sun S.Y.K. (2001) Helping processes in mind a mutual aid organization for persons with emotion disturbance. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 51, 295–308. Colijn S., Hoencamp E., Snijders H.J.A. Van Der Spek M.W.A. &

Duienoorden H.J. (1991) A comparison of curative factors in different types of group psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 41, 365–378.

Devan G.S. (2001) Reader’s forum: culture and the practice of group psychotherapy in Singapore. International Journal of Group Psy-chotherapy 51, 571–577.

Fuhriman A. & Butler T. (1983) Curative factors in group therapy: a review of the recent literature. Small Group Behavior 14, 131– 142.

Gunn R.C. (1978) A use of videotape with inpatient groups. Journal of Clinical Nursing 28, 365–370.

Houlihan J.P. (1977) Contribution of an intake group to psychi-atric inpatient milieu therapy. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27, 215–223.

Hwang K.K. (2000) Chinese relationalism: theoretical construction and methodological considerations. Journal for The Theory of Social Behavior 30, 155–178.

Kahn E.M. (1986) Inpatient group psychotherapy: which type of group is best? Group 10, 27–33.

Kahn E.M., Webster P.B. & Storck M.J. (1986) Curative factors in two types of inpatient psychotherapy groups. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 36, 579–585.

Kaplan K.L. (1988) Directive Group Therapy. Slack Inc., Thorofare, NJ.

Kapur R., Miller K. & Mitchell G. (1988) Therapeutic factors within in-patient and out-patient psychotherapy groups: implications for therapeutic techniques. British Journal of Psychiatry 152, 229–233.

Leszcz M., Yalom I.D. & Norden M. (1985) The value of inpatient psychotherapy: patients’ perceptions. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 35, 411–433.

Marcovitz R.J. & Smith J.E. (1983) Patients’ perceptions of curative factors in short-term group psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 33, 21–39.

Marsella A.J., DeVos G. & Hsu L.K. (eds) (1985) Culture and Self: Asian and Western Perspectives. Tavistook, New York.

Maxmen J.S. (1973) Group psychotherapy as viewed by hospitalized patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 28, 404–408.

May P. (1976) When, what and why? Psychopharmacotherapy and other treatments in schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry 17, 683–693.

Miles M.B. & Huberman A.M. (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Remocker A.J. & Storch E.T. (1992) Action Speaks Louder: A Handbook of Structured Group Techniques. Churchill Living-stone, New York.

Schaffer J.B. & Dreyer S.F. (1982) Staff and inpatient perceptions of change mechanisms in group psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 139, 127–128.

Spielaman R. (1975) A new application of closed group psycho-therapy in a public psychiatric hospital. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 9, 193–199.

Strassberg D.S., Roback H.B., Anchor K.N. & Abramowitz S.I. (1975) Self-disclosure in group therapy with schizophrenics. Archives of General Psychiatry 32, 1259–1261.

Tate F.B. & Longo D.A. (2002) Art therapy enhancing psychosocial nursing. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 40, 40–47.

Tseng W.S., Lu Q.Y. & Yin P.Y. (1995) Psychotherapy for the Chinese: cultural considerations. In Chinese Societies and Mental Health (Lin T.Y., Tseng W.S. & Yeh E.K. eds). Oxford Uni-versality Press, New York, pp. 281–294.

Waller D. (1993) Group Interactive Art Therapy: Its Use in Training and Treatment. Routledge Kegan Paul, Boston, MA.

Yalom I.D. (1975) The Theory and Practice of Group Psychother-apy. Basic Books, New York.

Yalom I.D. (1983) Inpatient Group Psychotherapy. Basic Books, New York.

Yang K.S. (1987) The Chinese People in Change, Vol. 3 in the series, collected works on the Chinese people. Kuei Kuan Book Co, Taipei (in Chinese).