Abstract—Mining generalized association rules with fuzzy

taxonomic structures has been recognized as a important extension of generalized associations mining problem. To date most work on this problem, however, required the taxonomies to be static, ignoring the fact that the taxonomies of items cannot necessarily be kept unchanged. For instance, some items may be reclassified from one hierarchy tree to another for more suitable classification, abandoned from the taxonomies if they will no longer be produced, or added into the taxonomies as new items. Additionally, the membership degrees expressing the fuzzy classification may also need to be adjusted. Under these circumstances, effectively updating the discovered generalized association rules is a crucial task. In this paper, we examine this problem and propose two novel algorithms, called FDiff_ET and FDiff_ET2, to update the discovered frequent generalized itemsets.

I. INTRODUCTION

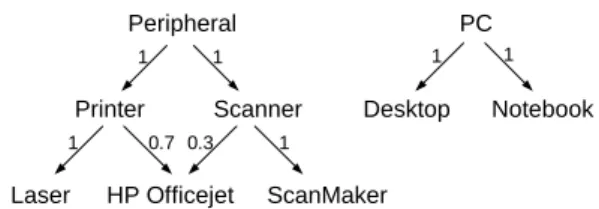

ince Srikant and Agrawal in 1995 [13] introduced the problem of mining generalized association rules from transaction database with taxonomy information, lots of subsequent researches on algorithmic improvement or model extension have been conducted. One of the prosperous avenues on extending generalized association mining is to consider fuzzy taxonomy [19], in which the child-node can partially belong to its parent-node with a certain degree in (0, 1). For example, consider the fuzzy taxonomy in Fig. 1, wherein HP Officejet is regarded as being both Printer and Scanner, but to different membership degrees.

Laser HP Officejet ScanMaker Printer Scanner Peripheral PC Desktop Notebook 1 1 1 1 1 1 0.7 0.3

Fig. 1. An example of fuzzy taxonomy T.

To our best knowledge, all work to date on generalized association rules with fuzzy taxonomies assumes that the taxonomic structure is static, not considering the situation that the taxonomy may change as time passes; some items will be

W.Y. Lin is with the National University of Kaohsiung, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan (corresponding author to provide phone: +886-7-5919517; fax: +886-7-5919514; e-mail: wylin@nuk.edu.tw).

M.C. Tseng is with the Refining Business Division, CPC Corporation, Taiwan (e-mail: clark.tseng@msa.hinet.net).

J.H. Su is with the National Cheng Kung University, Tainan City, Taiwan (e-mail: bb0820@ms22.hinet.net)

shifted from one classification to another, some trees of the taxonomies will be merged together or be split into smaller trees if the items on the trees cannot meet the demands in a new classification, items will be abandoned if those items do not be produced any more, and newborn items are added. Under these circumstances, how to update the discovered generalized association rules effectively becomes a critical task. Our previous work [16, 17] has studied this problem of updating generalized association rules but the taxonomy structure is crisp. In this paper, we extend our work to deal with the issue that the taxonomy is fuzzy. Two algorithms, FDiff_ET and FDiff_ET2, modified from our previously proposed algorithms Diff_ET and Diff_ET2 [16], are proposed.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. A review of related work is given in Section 2. The problem of updating previously discovered generalized association rules when the fuzzy taxonomic structure is evolved is formalized in Section 3. In Section 4, we elaborate on the proposed two algorithms and give an example to illustrate the ideas. Finally, our conclusions are stated in Section 5.

II. RELATEDWORK

The problem of mining association rules in presence of taxonomy information was first addressed in [6] and [13], independently. In [13], the problem was referred to mining generalized association rules, aiming to find associations among items at any crossing levels of the taxonomies under the minimum support and minimum confidence constraints. In [6] the problem of concern was somewhat different in that they generalized the uniform minimum support constraint to a level-wise assignment, i.e., items at the same level received the same minimum support. The objective is to develop mining associations level-by-level in a fixed hierarchy. That is, only associations among items on the same level are examined progressively from the top level to the bottom. Since then, several algorithmic improvements [8, 14] or problem extensions [4, 15] have been proposed.

The problem of mining generalized association rules with fuzzy taxonomic structures was first proposed by Wei and Chen [19]. Later in [2] they proposed an extension of the Apriori algorithm to accomplish this mining task. Various extensions of their work have been made recently, including the concept of introducing generalized weights to distinguish the importance of items in the taxonomy [9, 12], quantitative attributes [7, 18], multiple minimum supports [10], attribute

Updating Generalized Association Rules with Evolving Fuzzy

Taxonomies

Wen-Yang Lin, Ming-Cheng Tseng, and Ja-Hwung Su

generalization [1, 11].

Compared with the substantial amount of research on mining generalized association rules there is a lack of effort devoted to the problem of mining generalized associations with taxonomy evolution. In [16, 17], we have considered this problem and some of its extensions, and have proposed efficient Apriori-like algorithms.

III. PROBLEMSTATEMENT

A. Mining generalized association rules with fuzzy taxonomies

Let I{i1, i2, …, im} be a set of items and DB = {t1, t2, …, tn}

be a set of transactions, where each transaction tiTID, A

has a unique identifier TID and a set of items A (AI). We assume that the fuzzy taxonomy of items, T, is available and is denoted as a directed acyclic graph on IJ, where J = {j1, j2, …, jp} represents the set of generalized items derived from

I. An edge in T denotes an is-a relationship, that is, if there is

an edge from j to i, we call j a parent (generalization) of i and

i a child of j. For example, in Fig. 1 I = {Laser, HP Officejet,

ScanMaker, Desktop, Notebook} and J = {Scanner, Printer, PC, Peripheral}.

In a crisp taxonomy, we assume that the child item belonging to its ancestor has a membership degree with 1. But in a fuzzy taxonomy, the membership degree of an item may relate to all nodes of the taxonomy. For any two nodes x and y in the taxonomy, the membership degree xy of an item y

belonging to its ancestor node x can be calculated as follows [19]: xy= y x l : ( l e on le) (1)

where l: xy is one of the paths of accessing x from y, e on l is one of the edges on path l, andleis the membership degree on

the edge e on l. Operatorsand depend on the problem of concern. For illustrative purposes, max stands forand min for. Furthermore,xxis set to 1, indicating that any item is

fully belonging to itself.

Next, consider calculating the support of items under a fuzzy taxonomy. If a is an item in a certain transaction tDB, and x is an item in certain itemset X, then the membership degree xa with which a belongs to x can be obtained

according to (1). Finally, the support sup(X) = count(X)/|DB|, where count(X) denotes the accumulated degree that every transaction supports X in DB, calculated as follows:

( ) min(max ) xa DB t x X a t DB t tX X count

(2)Example 1 Consider Fig. 1. The membership degree

PeripheralLasermin {(Printer, Laser),(Peripheral, Printer)}min {1, 1}1. Similarly,PeripheralOfficejetmax {min {(Printer, officejet), (Peripheral, Printer)}, min {(Scanner, officejet),(Peripheral, Scanner)}

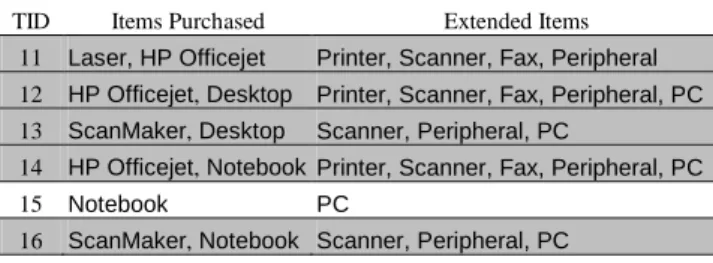

max {min {0.7, 1}, min {0.3, 1}} = 0.7. Now consider the transaction database in Table 1. Let X = {Peripheral, PC}. The degree that the first transaction supports X is min {max {PeripheralLaser, PeripheralHP Officejet}, max {PCLaser, PCHP Officejet} = min {max {1, 0.7}, max {0, 0}} = 0.

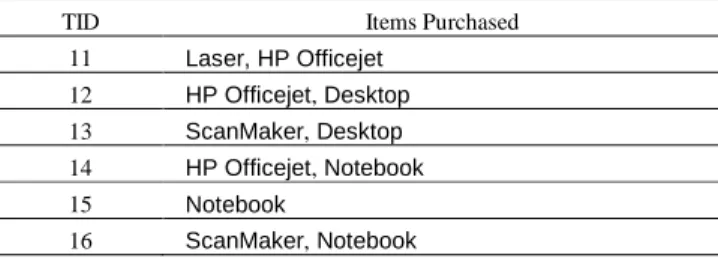

TABLE 1. ATRANSACTION DATABASE(DB).

TID Items Purchased

11 Laser, HP Officejet 12 HP Officejet, Desktop 13 ScanMaker, Desktop 14 HP Officejet, Notebook 15 Notebook 16 ScanMaker, Notebook

Given a user-specified minimum support ms and a minimum confidence mc, the problem of mining generalized association rules is to discover all generalized association rules whose support and confidence levels are larger than the specified thresholds. This problem is usually reduced to the problem of finding all frequent itemsets for a given minimum support.

After an initial discovery of all the generalized association rules in DB, let L be the set of all generalized frequent itemsets with respect to ms. As time passes, some update activities may occur to the taxonomies due to various reasons [5]. Let T’ denote the updated taxonomies. The problem of updating discovered generalized association rules in DB is to find the set of frequent itemsets L’with respect to the refined taxonomies T’.

B. Types of taxonomy updates

Our previous work [16] has identified four basic types of item updates that will cause taxonomy evolution, item

insertion, item deletion, item rename, and item reclassification. The essence of frequent itemsets update for

each type of taxonomy evolutions is further clarified in what follows. New type of taxonomy update specific to the fuzzy taxonomic structure is introduced as well. Note that hereafter the term “item”refers to a primitive or a generalized item. Type 1: Item insertion. The strategies to handle this type of update operation are different, depending on whether the inserted item is primitive or generalized.

When the new inserted item is primitive, we cannot process this item until there is an incremental database update, because the new item does not appear in the original set of frequent itemsets. On the other hand, if the new item represents a generalization, then the insertion itself also has no effect on the discovered associations until the new generalization incurs some item reclassification.

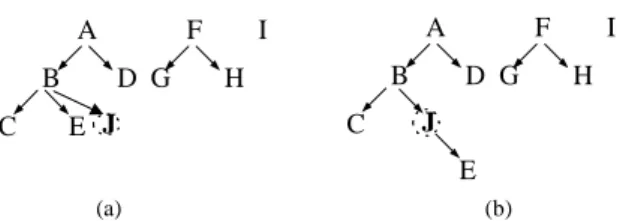

Fig. 2 shows an example of this type of taxonomy evolution, where a new item “J”is inserted as a primitive item or a generalized item. Note that in Fig. 2b item “E”is reclassified to the generalization represented by “J”.

A G C I D B F H E J A G C I D B F H J E (a) (b)

Fig. 2. An example of taxonomy evolution caused by item insertion. The inserted item “J” is:(a)primitive;(b)generalized.

Type 2: Item deletion. This case is similar to the insertion case. Nothing has to be done with the deletion of a primitive item if there is no transaction update to the original database. Notably the removal of a generalization may lead to items reclassification. Fig. 3 shows an example of this type of taxonomy evolution.

Type 3: Item rename. When items are renamed, we do not have to process the database. Instead, we just replace the frequent itemsets with new names and so the association rules.

A G C I D B F H A G C I D B F H E E (a) (b)

Fig. 3. An example of taxonomy evolution caused by item deletion: (a) The primitive item “E”isdeleted;(b)Thegeneralized item “B”isdeleted,and

items“C”and “E” arereclassified to “A”.

Type 4: Item reclassification. Among the four types of taxonomy updates this is the most profound operation. Once an item, primitive or generalized, is reclassified into another category, all of its ancestor (generalized items) in the old and the new taxonomies are affected. In other words, the supports of these affected generalized items have to be updated and so do the frequent itemsets containing any one of the affected generalized items. For example, in Fig. 4, the two shifted items E and G will change the support counts of generalized items A, B, and F, and also affect the support counts of itemsets containing A, B, or F. A G C I D B F H E A E C I G B F H D

Fig. 4. An example of taxonomy evolution caused by item reclassification. Intuitively, these four basic types of operations work on a fuzzy taxonomic structure as well. But an additional operation has to be included to accomplish the situation of membership adjustment.

Type 5: Membership adjustment. This operation refers to adjusting the membership degree of an item in the taxonomy. For example, one may change in Fig. 1 the degrees that HP

Officjet belongs to Printer and Scanner to 0.8 and 0.2, respectively. Unlike item reclassification, adjusting the membership of an item x has no effect on the support counting of x itself no matter x is primitive or generalized. It instead would change the support counting of the ancestors of x.

In this paper, we assume that there is no transaction update to the original database. That is, the transaction database is unchanged before and after the evolution of taxonomic structure.

IV. THE PROPOSED METHODS

Let ED denote the extended version of DB by adding in taxonomies T the ancestors of each primitive item to each transaction, while ED’denotes the extension of DB by adding generalized items in the updated taxonomies T’. A straightforward method to find updated generalized frequent itemsets would be to run the algorithm proposed by Chen and Wei [2] for finding generalized frequent itemsets on the updated extended transactions ED’. This simple way, however, ignores the fact that many discovered frequent itemsets would not be affected by the taxonomy evolution. If we can identify the unaffected itemsets, then we can avoid unnecessary computations in counting their supports. In view of this, we adapt the Apriori-like maintenance framework we used in [17]. Each pass of mining the frequent k-itemsets involves the following main steps:

1) Generate candidate k-itemsets Ckfrom the discovered set

of frequent (k-1)-itemsets L’k.

2) Differentiate in Ckthe affected itemsets (C ) from thek

unaffected ones (

C

k). 3) Incorporate Lk, C , andk k

C to determine whether a candidate itemset is frequent or not in the resulting database ED’.

4) Scan DB with T’, i.e., ED’, to count the support of itemsets that are undetermined in Step 3.

Below, we elaborate on each of the kernel steps, i.e., Steps 2 and 3.

A. Differentiation of affected and unaffected itemsets

Definition 1 An item (primitive or extended) is called an

affected item if its support would be changed with respect to

the taxonomy evolution; otherwise, it is called an unaffected

item.

Consider an item xT T’and the three independent subsets T T’, T’T and T T’. There are three different cases in differentiating whether x is an affected item or not. The case that x is a renamed item is neglected for which can be simply regarded as an unaffected item.

Case 1. xT T’. That is, x is an obsolete item. Then the support of x in the updated database should be counted as 0 and so x is an affected item.

Case 2. xT’T. That is, x denotes a new item. If x is a primitive item, it doest not appear in the database and so can be regarded as an unaffected item. Otherwise, x should be

regarded as an affected item since its count shall change from zero to nonzero.

Case 3. xT T’. This case also depends on whether x is a primitive or generalized item. Obviously, if x is a primitive item, there is no change on its support and so x is an unaffected item. On the other hand, if x is a generalized item, its count may change or not, depending on whether any of its descendants is involved in any evolution operation of item reclassification or membership adjustment. Recall that in (2) the support counting of an itemset is primarily determined by calculating the membership degree in (1). Thus we can derive a simple rule for determining a generalized item as affected or not, as clarified in the following lemma.

Let Q(x) and Q’(x) denote in T and T, respectively, the set of primitive descendants of x, each along with their membership degrees with respect to x. More specifically, Q(x) {(y1,xy1), (y2,xy2), …, (yn,xyn)} and Q’(x){(y’1,xy’1),

(y’2,xy’2), …, (y’m, xy’m)}, where {y1, y2,…, yn} and {y’1, y’2, …, y’m} are the descendants of x in T and T’, respectively.

Lemma 1 Consider a generalized item xT T’. If Q(x) Q’(x), then countED(x) countED’(x), where Q(x)Q’(x) means mn; y1y’1, …, yny’n; and xy1xy’1, …, xyn

xy’n.

Proof: Consider a transaction t in DB. If t supports x with

respect to ED, there exists at least one item being primitive descendant of x in T, say d1, d2, …, diand {d1, d2, …, di}{y1, y2,…, yn}. Likewise, if t supports x with respect to ED’, then

there must exist at least one item being primitive descendant of x in T’, say {d’1, d’2, …, d’j} and {d’1, d’2, …, d’j}{y’1, y’2,…, y’m}. Since mn and y1y’1, …, yny’n, it follows

that ij and d1d’1, …, did’i. Further,xd1xd’1, …,xdi

xd’i. According to (2), the degree that t supports x in ED is

equal to that in ED’. The lemma then follows.

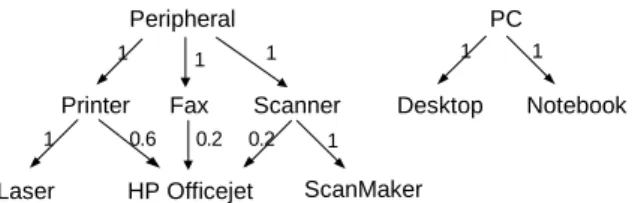

Example 2 Suppose that the taxonomy in Fig. 1 is refined to that in Fig. 5, with the inclusion of a new subcategory of peripheral, Fax, as well as the adjusting of membership degrees of HP Officejet. Clearly, Fax is an affected item (Case 2). Now consider the generalized items satisfy Case 3, i.e., Printer, Scanner, Peripheral, and PC. PC is unaffected since it possesses the same set of primitive descendants, each of which retains the same membership degree. However, Printer, Scanner, and Peripheral are affected items. Although each of them has the same set of primitive descendants, at least one of its primitive descendants changes the membership degree.

Fig. 5. A refined fuzzy taxonomy of T in Fig. 1.

Definition 2 For a candidate itemset A, we say A is an

affected itemset if it contains at least one affected item.

Definition 3 A transaction is called an affected transaction if it contains at least one of the affected items with respect to a taxonomy evolution.

B. Inference of Frequent and Infrequent Itemsets

Now that we have clarified how to differentiate the unaffected and affected itemsets, we will show how to utilize this information to determine in advance whether or not an itemset is frequent before scanning the updated extended database ED’. We observe that there are four different cases.

1) If A is an unaffected itemset and is frequent in ED, then it is also frequent in ED’.

2) If A is an unaffected itemset and is infrequent in ED, then it is also infrequent in ED’.

3) If A is an affected itemset and is frequent in ED, then it may be frequent or infrequent in ED’.

4) If A is an affected itemset and is infrequent in ED, then it may be frequent or infrequent in ED’.

Note that only cases 3 and 4 need further database scan to determine the support count of A. Table 2 summarizes the above discussion.

TABLE 2. FOUR CASES FOR INFERRING WHETHER A CANDIDATE ITEMSET IS FREQUENT OR NOT.

T T’ L ED’ Action Case

frequent no 1 unaffected infrequent no 2 ? scan ED’ 3 affected ? scan ED’ 4 C. Algorithm FDiff_ET

Based on the aforementioned concepts, the proposed FDiff_ET algorithm is described in Fig. 6.

First, let candidate 1-itemsets C1be the set of items in the new item taxonomies T’. Next derive the membership degree among all items in C1represented as a matrix and identify affected items for dividing candidate itemsets. Then load the original frequent 1-itemsets L1and divide C1into two subsets:

1

C and C .1 1

C consists of unaffected 1-itemsets in L1, and

1

C contains affected 1-itemsets, where C is for Cases 1 and1

2, and C is for Cases 3 and 4. According to Case 2, all1

itemsets inC that is not in L is infrequent and so are pruned.1

Then compute the support counts of each 1-itemset in C1

over only transactions that contain affected items in ED’. After this, we create new frequent 1-itemsets Lby1

combiningC and those itemsets being frequent in1 C . The1

next cycle is that we generate candidates 2-itemsets C2from

1

Land repeat the same procedure until no frequent k-itemsetsLkare created.

Laser HP Officejet ScanMaker Printer Scanner Peripheral PC Desktop Notebook 1 1 1 1 1 1 0.6 Fax 1 0.2 0.2

Input: (1) DB: the original database; (2) ms: the minimum support; (3) T: the

old fuzzy taxonomy; (4) T’: the new fuzzy taxonomy; (5) L: the set of old frequent itemsets.

Output: L’: the set of new frequent itemsets.

Steps:

1. C1be set of all items in T’excluding new primitive items;

2. Create MD; /* the table of membership degree using (1) */

3. C1+= iden_AItem(MD, MD’, T, T’); /*Identify all affected items. */

4. k1;

5. repeat

6. if k > 1 then

7. Ckapriori-gen(L’k1);

8. delete any candidate in Ck that consists of an item and its

ancestor; 9. endif

10. load original set of frequent k-itemsets Lk;

11. divide Ckinto two subsets:C , andk C ;k

12. for each AC dok

13. if ALkthen supED’(A)supED(A); /* Cases 1*/

14. else delete A fromC ; /* Case 2 */k

15. scan ED’to count countED’(A) according to (2) for each itemset A in

k

C ; /* Cases 3 & 4 */

16. L’kC U{A | Ak Ckand supED’(A)ms}; k++;

17. until L’k1

18. L’UkL’k;

Fig. 6. Algorithm FDiff_ET.

D. Algorithm FDiff_ET2

The second algorithm FDiff_ET2 follows the same idea of Diff_ET2. Instead of scanning ED’as a whole for cases 3 and 4, FDiff_ET2 adopts a stratify paradigm, first scanning the affected transactions both in ED and ED’identified according to Definition 3, hopefully saving the cost for scanning the rest of ED’. This idea is further clarified in the following lemma.

Lemma 2 If an affected itemset AL and count’(A) – count(A)0, then A L’, whereand ’denote the sets of transactions in ED and ED’, respectively, affected by taxonomy update.

Proof: If AL, then countED(A)|ED| ms. Note that |ED’|

|ED||ED| || |’| due to || |’|. Hence, countED’(A)

countED(A) + (count’(A) –count(A))|ED| ms | ED’|

ms. Thus, A L’.

Thus in case 4, we scan the affected transactions in ED and

ED’to count the appearances of A. If the support count of A in

ED’s affected transactions is greater than that in ED’, then we have to scan the rest of ED’to decide whether A is frequent or not.

Example 3 Consider the transaction database in Table 1 again. The corresponding extended transaction database ED by inserting generalized items in taxonomies T and the updated extended transaction ED’by inserting generalized items in taxonomies T’are shown in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively, where those shaded transactions denote the affected part.

TABLE 3. THE EXTENDED TRANSACTION DATABASEED.

TID Items Purchased Extended Items 11 Laser, HP Officejet Printer, Scanner, Peripheral 12 HP Officejet, Desktop Printer, Scanner, Peripheral, PC 13 ScanMaker, Desktop Scanner, Peripheral, PC 14 HP Officejet, Notebook Printer, Scanner, Peripheral, PC

15 Notebook PC

16 ScanMaker, Notebook Scanner, Peripheral, PC

TABLE 4. THE UPDATED EXTENDED TRANSACTION DATABASEED’. TID Items Purchased Extended Items

11 Laser, HP Officejet Printer, Scanner, Fax, Peripheral 12 HP Officejet, Desktop Printer, Scanner, Fax, Peripheral, PC 13 ScanMaker, Desktop Scanner, Peripheral, PC

14 HP Officejet, Notebook Printer, Scanner, Fax, Peripheral, PC

15 Notebook PC

16 ScanMaker, Notebook Scanner, Peripheral, PC

V. CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we have investigated the problem of updating generalized association rules with evolving fuzzy taxonomies. We have elaborated on the design of two algorithms, FDiff_ET and FDiff_ET2, for updating previously discovered generalized frequent itemsets, yet the implementation and performance study of the proposed two algorithms will be accomplished in the future.

Although our work in this study has advanced the research in generalize associations mining, there are many unexplored issues deserved further investigation. For example, the study can be extended to a more general model that incorporates multiple minimum supports, weights of items, quantitative database, and even more complicated fuzzy ontological structure such as that exploiting both classification and component relationships. Another important direction is on embedding the frequent pattern maintenance scheme into an online data mining platform.

REFERENCES

[1] R.A. Angryk and F.E. Petry, “Mining multi-level associations with fuzzy hierarchies,”Proc. 14th IEEE Int. Conf. on Fuzzy Systems, pp. 785–790, 2005.

[2] G. Chen and Q. Wei, “Fuzzy association rules and the extended mining algorithms,”Information Sciences, vol. 147, no. 1-4, pp. 201–228, 2002.

[3] J.M. DeGraaf, W.A. Kosters, and J.J.W. Witteman, “Interesting fuzzy association rules in quantitative databases,” Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, vol. 2168, 2001.

[4] M.A. Domingues and S.O. Rezende, “Using taxonomies to facilitate the analysis of the association rules,”Proc. 2nd Int. Workshop on

Knowledge Discovery and Ontologies, pp. 59–66, 2005.

[5] J.Han and Y.Fu,“Dynamic generation and refinement of concept hierarchies for knowledge discovery in databases,” Proc. AAAI’94 Workshop on Knowledge Discovery in Databases, pp. 157–168, 1994. [6] J.Han and Y.Fu,“Discovery ofmultiple-level association rules from largedatabases,”Proc. 21st Int. Conf. Very Large Data Bases, pp.

[7] T.P. Hong, K.Y. Ling, S.L. Wang, “Fuzzy data mining for interesting generalized association rules,”Fuzzy Sets and Systems, vol. 138, pp.

255–269, 2003.

[8] Y.F. Huang and C.M. Wu, “Mining generalized association rules using pruning techniques,”Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Data Mining, pp. 227–234, 2002.

[9] M. Kaya and R. Alhajj, “Effective mining of fuzzy multi-cross-level weighted association rules,”Proc. 16th Int. Symp. on Foundations of

Intelligent Systems, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 4203, pp.

399–408, 2006.

[10] Y.C. Lee, T.P. Hong, and T.C. Wang,“Multi-level fuzzy mining with multiple minimum supports," Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 34, pp. 459–468, 2008

[11] F.E. Petry and L. Zhao, “Data mining by attribute generalization with fuzzy hierarchies in fuzzy databases,”Fuzzy Sets and Systems, vol. 165, no. 15, pp. 2206–2223, 2009.

[12] B. Shen, M. Yao, and Y. Bo, “Mining weighted generalized fuzzy association rules with fuzzy taxonomies,” Proc. Int. Conf.

Computational Intelligence and Security, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 3801, pp. 704–712, 2005.

[13] R.Srikantand R.Agrawal,“Mining generalized association rules”,

Proc. 21st Int. Conf. Very Large Data Bases, pp. 407–419, 1995.

[14] K. Sriphaew and T. Theeramunkong, “Fast algorithms for mining generalized frequent patterns of generalized association rules,”IEICE

Transaction on Information and Systems, vol. 87, no. 3, pp. 761–770 2004.

[15] M.C. Tseng and W.Y. Lin, “Efficient mining of generalized association rules with non-uniform minimum support,”Data and Knowledge

Engineering, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 41–64, 2007.

[16] M.C. Tseng, W.Y. Lin, and R. Jeng, “Updating generalized association rules with evolving taxonomies,”Applied Intelligence, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 306–320, 2008.

[17] M.C. Tseng, W.Y. Lin, and R. Jeng, “Incremental maintenance of generalized association rules under taxonomy evolution,”Journal of

Information Science, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 174–195, 2008.

[18] S. Wang, K.F.L. Chung, and H. Shen,“Fuzzy taxonomy, quantitative database and mining generalized association rules,”Intelligent Data Analysis, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 207–217, 2005.

[19] Q. Wei and G. Chen, “Mining generalized association rules with fuzzy taxonomic structures,”Proc. 18th Int. Conf. North American Fuzzy