Framing Information Systems: An Institutional Perspective

on CRM System Implementation

The type of the submission: complete research Total words: 4999

ABSTRACT

This paper aims to inquire how organisational institutions can impose constraints on the sense-making process of information systems in organisations. A CRM project is analysed from the perspective of technology frames analysis and institution theory. The findings demonstrate that technological frames are social phenomena shared by individuals; and the institutional analyses are proved to be helpful in terms of understanding how the social cognition (technological frames) is structured. The study also shows that the social rules produced cognitive inertia that prevented the company from adopting new ideas and technology that differ from the organisational status quo.

Keywords: technological frames, organisational institutions, IS implementation, CRM; institution theory.

1. INTRODUCTION

It is recognised that users’ cognitive assessments are critical to understanding information systems (IS) use in organisations (McLoughlin and Harris, 1997). Prior researchers argue the knowledge, assumptions and expectations individuals have about an IS will affect their attitudes and use of the system significantly (Karahanna et al., 2006). It is noted that individuals’ cognitions are dynamic and conditioned by the surrounding contextual factors such as organisational structures and culture (Karahanna et al., 2006). Powell and

DiMaggio (1991) emphasize the focus should be on the properties of supra-individuals and the analysis should be more on cognitive and cultural aspects of social entities than on the aggregations or direct consequences of individuals’ attributes or motives. The importance of contextual factors has been well studied in the IS domain, but many focus either on the contextual factors per se or on the influence of the contextual factors on the implementation process (Davidson and Chiasson, 2005) and fewer focus on their effects on individuals’ cognition.

This paper aims to investigate how organisational institutions can impose constraints on the sense-making process of IS in organisations. This study draws on technological frames analysis and institution theory. The former aims to understand individuals’ assumptions and perceptions of IS in their local organisational context; while the later explains how institutions can shape individuals’ views of IS. A case study was conducted to study a customer relationship management (CRM) system implementation in a leading consumer electronics retailer. The findings show individuals’ understanding of IS can be heavily constrained by formal and informal institutions; the shared understanding of the system subsequently lead to the system disuse.

2. THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

Technological frames

Technological frames analysis was developed to address users’ cognitive assessments of technology and its use (Orlikowski and Gash, 1994). Users interact with the technology in accordance with the meanings the technology has for them (Kaplan and Tripsas, 2008). The term ‘frames’ is conceptualised as lenses through which people reduce the complexity of their environment to concentrate on particular elements and make context-specific interpretations, decisions and actions (Goffman, 1974). Technological frames are “a set of assumptions, meanings, knowledge, and expectations that people use to understand the nature

and role of technology in organisations. This includes not only the nature and role of the technology itself, but also the specific conditions, applications, and consequences of that technology in particular contexts” (Orlikowski and Gash, 1991, p.3).

Frames are unique to individuals, but those who share the same interests and are in the same stakeholder group are likely to have similar frames and therefore act in the same way towards a technology (Orlikowski and Gash, 1994). This is known as congruence of frames that can be achieved through interactions and negotiations between different stakeholder groups. It is hence argued frames are dynamic in nature and are time and context-dependent (Davis and Hufnagel, 2007). However, the framework does not explicitly deal with the emerging process of frames. It takes frames as they are and overlooks the fact that frames are affected by the ‘dominant frame’ of an organisation (McGovern and Hicks, 2004). The concept of organisational institutions may be of use in examining how particular technology interpretations are constructed within a broader context (e.g. dominant thinking in an organisation) and the regulative structure of an organisation.

Institutions

Institutions guide and regulate individuals’ actions, establish baseline conditions for interactions and guarantee a certain degree of predictability of human behaviour in a particular situation (Nelson and Sampat, 2001). They facilitate individuals’ decision-making processes, and reduce the uncertainties involved in human interactions (North, 1990).

There are two types of institutions: formal and informal. Formal institutions resemble regulative institutions which involve the capacity to establish rules, mechanisms for surveillance and sanctions for promoting certain types of behaviour and restricting others (Scott, 2001). Informal institutions are also termed as ‘cognitive institutions’ that define the way in which the world is and should be and involve the creation of shared schema or conceptions and are (Barley and Tolbert, 1997; Scott, 2001). This view of informal

institutions indeed resembles the concept of frames mentioned above. Both cognitive institutions and frames analysis have theoretical roots in socio-cognitive research and both argue that cognition provides symbolic frames through which the meanings of things are formed (Scott, 2001). Frames analysis pays more attention to individuals’ cognitive states that facilitate individuals’ sense making about technologies. Collective frames may be developed under a broader organisational cognitive state or cognitive institution.

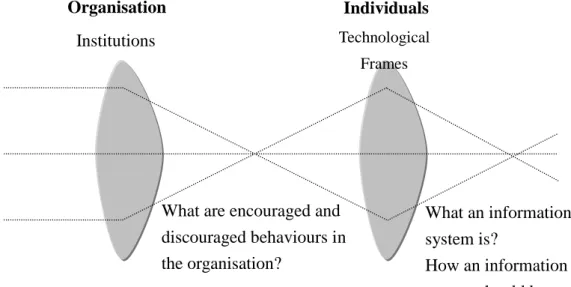

Figure 1 illustrates both institutions and frames are proposed as filters influencing individuals’ cognitive assessment and interpretation of business and technology respectively. Organisational institutions are widely accepted and enforced rules that regulate employees’

behaviour and facilitate their decision-making process within organisations. Because institutions shape individuals’ interactions by encouraging actions that are productive and disapproving of actions that are economically costly (Nelson and Sampat, 2001), employees know what they are prohibited from doing under what conditions.

Both institutions and frames are socially constructed. Like organisational institutions, frames can be seen as templates for problem solving and as filters for filtering contextual

Organisation

Institutions Technological

Frames

What are encouraged and discouraged behaviours in the organisation? What an information system is? How an information system should be Figure 1. Institutions and Technological Frames

information that may be imprecise and conservative (Markus and Zajonc, 1985). However, organisational institutions are produced and reproduced through ongoing interactions among members of a social group (e.g., stakeholders, managers, employees) (Barley and Tolbert, 1997) and the emphasis of organisational institutions is on a community level rather than on individual level. In contrast, frames originate at individual level and are developed on the organisational environment they are embedded. Users’ acceptance or rejection of technologies is heavily influenced by the perception of the technology in the environment (Standing et al., 2009). In this sense, a technology is framed by users within their organisational institutional environment.

3. RESEARCH APPROACH AND METHOD

A case study method was deployed for this study in order to understand key individuals’ technological frames of a new IS, a CRM System, in the organisation, and how institutional rules affected the formation of the understanding of the system. An interpretative approach was employed for data analysis because the approach entails ontological assumptions and views that the understanding of the meanings and social institutions that emerge from a process of continuous negotiation among social actors (Walsham, 2006). This position is particularly important to this study as both frames and institutions are regarded as socially constructed templates for social interactions.

Data collection

The fieldwork for the research reported was carried out during 2004 and 2005. Semi-structured interviews with key personnel involved in the CRM project were the main data sources. In-depth interviews were conducted with two CRM users and one CRM project leader in the case company and some less structured interviews were taken with one IT consultant and two executives of the CRM vendor, a committee member of the government

grant program, an external CRM consultant who involved in the whole CRM developing process, and 5 customers.

The interview contents included the project process, interviewees’ understanding of the project initiative, the actions taken, strategies used to implement the CRM system, the CRM system functions, and how the system was perceived and used in the company. Secondary data was also collected including the company’s annual reports between 1997 and 2005, press articles, company newsletters and industry reports of the consumer electronics sector.

Data analysis

The data analysis was carried out in two steps. The first step was to identify the key institutions that impacted on the formation of the technological frames of the CRM system in the company. The key institutions were then sub-divided into formal and informal institutions. The former include an incentive system and a resource allocation policy and the later can be observed in the company’s business strategies. Then we examine how the system was framed in the context of these institutions. The nature of the technology and technology in use were the two elements of the technological frames found important to individuals’ interpretation of the technology.

Research site: MRetailer

MRetailer started up as a household-appliance manufacturer, moving in the past decade into the consumer electronics retail sector. At the time of the study, MRetailer was a leading consumer electronics retailer in Taiwan employing nearly 4000 workers and with more than two million customers registered as members. However, competition in the consumer electronics market in Taiwan was tough and MRetailer faced a number of challenges. Competition resulted from low entry barriers made the consumer electronics market being saturated and the shorter life cycles of consumer electronic products induced high market

uncertainty. To maintain its leading position MRetailer had to control and even reduce its costs through strong relationships and bargaining power with its suppliers, and at the same time work to improve its inventory management through more accurate forecasting of customer demand. MRetailer decided to adopt a CRM system for becoming a more customer-oriented company. MRetailer secured a government grant to finance the new system and the Chief Executive of MRetailer invited an independent CRM consultant to take a part in the project initiative. The system development was outsourced but the system was tailored and fully integrated into the existing IS infrastructure within the company. In spite of initial expectations, many existing practices in MRetailer remained more or less the same after the CRM system was introduced. Instead of becoming more customer-centric with the help of the CRM system, MRetailer continued to use mass marketing and product-centric promotion as its primary strategy for pursuing customers and to boost sales revenues. It was understood that no other form of target marketing strategy was deployed and the CRM initiative seemed to gradually fade into the background.

4. ANALYSES AND FINDINGS

Formal institutions

Formal institutions that dominate MRetailer’s business practice and values are its incentive system and resource allocation policy (Table 1). They were formed on the basis of its business mission of “being champion in the retail market” and on its vision of “becoming a world class retailer like the Wal-Mart of Asia”. MRetailer viewed incentive systems as means for managerial intervention in employees’ performance and it required the “attainment of company goals” from employees. The annual sales target was the basis of the meritocracy program that sets business targets for all departments and all employees. Accordingly, the performances of the Membership Service department and of its staff were evaluated by the number of customers subscribing to the membership scheme and the growth rate in

memberships. Although it recognised the importance of other measures such as customer satisfaction and loyalty, when evaluating the performance of the Membership Service Department they are not taken into account because it is difficult to quantify them. The biannual staff appraisal programme is in place to ensure good performance and the outcome of an appraisal is used to determine the staff’s employment contract. Staff whose performance is in the bottom 5 per cent of the entire company will be laid off and their position will be filled by new recruits. MRetailer believed that such a policy would encourage employees to be more productive.

The incentive system also affects the way in which the company evaluates new business ideas. In general, new business ideas and strategies were welcomed by the management, but employees had to demonstrate how much and how soon new ideas and strategies could improve the company’s market share. The CEO required the outcomes of every new idea and strategy should be observed in 6 months. This meant that in respect of the CRM system, the return on investment should be realised within six months after its initiation. A key user of the CRM system in the Membership Service Department said:

The key is not only to make this (CRM) system bloom, but also to bloom in a short period of time.

Another formal institution significantly impact on how the CRM system was perceived was the resource allocation policy. Resources and the annual budget allocated for marketing were decided a priori and they were not changed according to the strategies of the current year. With a limited budget, employees had to prioritise those marketing campaigns that would help increase the sales. Hence sales revenues became the dominant indicator of all marketing campaigns and departments’ performance

Revenues and profits are quite different in nature. However, sales revenues are the only measure of the department’s performance. Those who fail to meet the required sales targets will be asked to leave (Membership Service manager).

Table 1: Institutions and Frames of CRM in Mretailer

Institutions Framing the CRM Results after CRM initiative

Formal institutions

The incentive system formulates a business target for each department and this is used as the basis to measure individuals’ performances. Those who underperformed would be laid off. Business targets emphasised quantitative indices such as sales, number of stores and number of subscribers.

Organisational resources and efforts were mainly used to support marketing activities that can generate market share and maximise sales quickly.

Mass marketing got most of the organisational resources and targeted marketing had little organisational support.

Informal institutions

In MRetailer, the major strategies were fierce price promotions, aggressive channel-expansion and the membership programme. These strategies were used to construct a strong channel to increase its power when bargaining with suppliers and gain a cost-leadership position in the market.

Competition in the retail market was via economies of scale and cost-leadership.

Speed of growth in market share was the most important thing for competition and sales revenue count for everything. It is an outcome-oriented organisation culture.

Customer loyalty was difficult to obtain.

One to one marketing is expensive and the spirit of CRM does not align with the organisational culture which emphasises plundering rather than permeating strategies.

The effectiveness of CRM takes a longer time to realise than that of mass marketing.

CRM can only bring incremental growth in revenues.

Target marketing cannot generate the same amount of revenue as mass marketing does.

CRM is used for customer relationship maintenance not for sales generation. Market penetration of CRM is too slow.

CRM campaigns were not part of routines but were exceptional activities and no more CRM campaigns were held after 2005. Data analysis from the CRM system was not the routine job but an addition to the routine job of Membership Service Department. Only two persons used the CRM system and they were not dedicated to the job.

No evaluation and tracking of the use and performance of CRM campaigns was done.

Target marketing supported by CRM was not appreciated for the employees.

Management did not care about the analysis results from CRM system.

Informal institutions

Informal institutions refer to the norms and cognitions that guide people’s behaviours and decision-making and they are embedded in MRetailer’s business strategies and practice.

Because of the saturated nature of market, the only way for a company to expand its market share was to use plundering rather than permeating strategies (Cited from the speech of MRetailer’s CEO). With the aim of expanding its market share at speed and becoming the market leader MRetailer used strategies such as aggressive channel-expansion, fierce price promotions and a membership programme.

Aggressive channel-expansion. During the past decade, most companies in the consumer electronics industry in Taiwan attempted to create a strong channel by store extension, and this was true to MRetailer. The strategy of aggressive channel-expansion aims to achieve ‘economies of scale’ to increase its bargaining power with suppliers and meanwhile build brand awareness through the high density of stores in commercial locations. A retail industry analyst commented on the rapid store expansion of MRetailer:

When running a retail business, scale or the number of stores is very important. … [MRetailer] can enjoy lower operational costs and strong brand awareness once they reach economies of scale.

The management also recognised channel-expansion as a good way for company growth:

We are a fast growing company. The quickest way to stimulate growth is through opening new stores because where there are stores there are the customers.

Fierce price promotions. In order to increase sales revenues, MRetailer focuses on price competitiveness. The routine sales and promotional items were decided by the Purchasing department at the headquarters on the basis of the best deals secured with the suppliers. With regard to short product life cycle, the store managers’ responsibility was to promote these items and sell them quickly to reduce the inventory risk. MRetailer regularly engages in price wars by undercutting competitors’ prices and offering heavily discounted products; and

this strategy has proved to be effective as MRetailers’ sales usually accelerated within a short space of time.

We found an obvious decrease in our sales during the non-promotion period. (Director of CRM software Development)

Membership programme. The membership programme was used to ensure MRetailer’s leading position in the market. MRetailer provided economic incentives to encourage customers to join its membership programme and MRetailer used “the total number of members” as an indicator of the company’s performance. Between 2002 and 2003, members grew at a rate of over 40% each month, and members’ purchases contributed to over 90% of the company’s total revenues.

Business strategies reflect the value system within MRetailer. Being a household appliance manufacturer in the past might have had some influence on the company’s perception of the way in which to manage its competition; i.e., economies of scale and cost leadership were good ways to compete in the global market. Such perceptions subsequently became the implicit rules and norms of the company that drove its business strategies. These strategies paid off as MRetailer became the market leader in terms of sales revenues. This achievement reinforced the company’s perception that store expansion was a means to grow at the fastest possible pace and the transaction-based approach (a more product-centric way) with competitive price was a must to boost sales. Achievements in the growth of sales became dominant norms which not only had a profound influence on management decision making but also guided employees’ behaviours. Although it was clear to the management that the sales revenues were not equal to the profit, sales maximisation somehow was synonymous with profit maximisation at the MRetailer. Finally, there seemed to be a shared belief among the employees that it was difficult to maintain customer loyalty and measure their satisfaction. This could be due in part to the fact that the market is competitive and

customers could easily find a substitute product elsewhere at a more competitive price. For example, consider this manager’s comment:

It’s difficult to obtain customer loyalty. Even with the offering of coupons, customers won’t stay loyal.

The domains of the technology frames

The nature of technology

Nature of technology refers to individuals’ experience, views, opinions and expectations of the CRM system. The CRM system was introduced to the employees as a tool for one-to-one direct marketing. One-to-one-to-one marketing differs significantly from the mass marketing approach that has historically been used by the company. The employees viewed the CRM system and the marketing campaign organised around the system as expensive and contributing little to business and to their performance in the short term.

MRetailer considered that the speed of its market share expansion was critical to its survival and the predatory business strategy based on such belief (e.g., fierce price-promotions, rapid channel-expansion, and aggressive member recruiting to seize market share from its competitors) had paid off and helped the company to win the leading position in the market. The predatory strategy hence received the public endorsement of senior management. In this sense, some viewed that moving towards a targeted marketing approach was inappropriate as the approach was understood to emphasise incremental market penetration and to focus on some small specifics rather than on undifferentiated groups of customers.

The high staff turnover in the company (e.g., it laid off 5% of staff every year) caused gaps in the understanding of value and role of the CRM system in the company. One consequence of this was that there was little appreciation of the CRM system among management. One manager commented:

Those newly succeeding supervisors do not understand the first half story of CRM implementation. They don’t understand or are not familiar with the system and they might

say, “Since I can go this far without this technology, why should I bother to learn it now?” Therefore they might stick to their old patterns of decision-making. …

Technology in use

Technology in use refers to individuals’ views of how their work can be supported or changed by the technology. An incentive to use the system would be the value that the new system adds to their work and performance (Karsten and Laine, 2007).

The CRM system was seen as means of maintaining customer relationships in the long term and therefore as unable to help generate sales quickly in a short period of time. Managers expected that with the CRM approach they would generate less sales revenue compared to the mass marketing approach and did not support the system.

CRM is a niche marketing strategy. It takes time to see the outcomes [via CRM]. […] If the company wants to compete efficiently, there is no doubt mass marketing is better than CRM The sales revenues that came from CRM campaigns were much less than those of from mass marketing campaigns at MRetailer because of the number of customers targeted. That is, the CRM campaigns did not generate as much revenue and as quickly as mass marketing campaigns did.

How can it be possible to generate tens of billions dollars (NTD) by directly communicating with individual customers?!

Not only did the senior management have their concerns about the CRM system but also the staff in the Marketing department. Because all marketing activities share the limited marketing budget and the marketing staff were concerned that CRM campaigns would absorb most resources and leave very little for other marketing campaigns. Hence, the staff were inclined to use words such as ‘expensive’ and ‘costly’ to describe the system and the associated marketing approach.

As the company decided to adopt CRM, we were worried. We all knew one-to-one marketing is costly and especially our annual marketing budget is more or less the same every year which does not change according to the sales target of the year or the sales of the previous year (Membership Service Manager).

Without observing any clear contribution to MRetailer’s revenues, the CRM system was perceived as a strategy that the company could afford not to employ. Subsequently there was

little support from the management for using the CRM system. Since the product-centred and transactional-based marketing strategy had served MRetailer well thus far, the management did not see the need to use the CRM in pursuit of a customer-centric strategy.

The responsibilities for planning CRM marketing campaigns and using the system to carry out data mining were assigned to the Membership Service department rather than to the Marketing department. The CRM marketing campaigns hence were not perceived as routine but as ‘special marketing activities’ in the company. This reinforced the existing “less positive” frames of the CRM and further marginalised the system and its marketing approach. As the Membership Service department’s performance was evaluated on the basis of the total number of members on the membership scheme and the annual growth in membership, staff in the department perceived that using the CRM system increased their workload and did not contribute to their performance. Lack support from management, analysis generated by the CRM system was not appreciated and consequently it was difficult to observe the usefulness of the CRM system.

CRM requires the top management support. To have the support means to receive the recognition from the management and to have their consistent support. If the top management views the CRM system simply as a computer system and saying that ‘I don’t understand computers,’ then it (CRM practice) won’t work. […] I don’t think they (top management) recognize the importance of CRM […] Success of CRM requires continuous resources devoted and practices. The company could have used the CRM properly for bigger marketing campaigns, but it has never done so. What the Membership Service department has done so far were all small projects and petty sales that only produced insignificant outcomes. (Membership Service Manager)

5. DISCUSSION

Orlikowski and Gash (1994) noticed that a company’s incentive system can influence the way in which a system is perceived and used in the organisation, and this study has shown an extreme case where the failure of the CRM system in MRetailer is rooted in the company’s incentive system. The incentive system, which is performance driven and measured by sales

revenues and growth in membership recruitment was inconsistent with the essence of the CRM practice. The system hence was framed negatively in the company. Changes made in formal institutions may give people scope for ceremonial use of CRM in the short term, but to encourage people to embrace the CRM value and use it in their routine activities a shift from transactional thinking to relationship thinking is required in the long term. This case shows that making changes to the existing practice may not always be possible in a short period of time and it requires some major reengineering in its value and culture systems. Questions hence arise: Should technology adoption companies simply invest in a system that can support and reinforce the current practice if changes are not possible?

Incongruence is believed to lead to inconsistency in technology use (Orlikowski and Gash, 1994). This study nevertheless shows that frame incongruence is not a critical issue but frame congruence is. There was congruence in the understanding of the CRM system among employees, but the shared frame was guided by the company’s external and internal business discourse: aggressive, fast market expansion and growth in sale revenues. The company’s recruitment policy in place was firing and hiring to reinforce the company discourse. People rejected the CRM approach quickly since they could not see how CRM methods contributed to their performance in a short period of time. Technological frames are inflexible and early interpretations are especially influential and difficult to change once they are formed (Orlikowski and Gash, 1994). It is important to plan the way in which a system is introduced to a company. The CRM system was introduced into MRetailer as a tool for one-to-one marketing but this concept was immediately rejected by the employees and the frames of the system in the company were hard to change. A misfit between task and CRM was resulted by such frames because CRM was considered as a bad strategy for gaining market share in MRetailer. The dominant business discourse also had significant impacts on the senior management’s attitudes towards the system because it is more important for the senior

management to maintain their status quo than to have a new approach. Besides, because a new technology may not fit the predominant collective frames and usually excelled on a new and different set of performance comparing to the existing one, the new technology is often ignored and may perceived as inferior to current solutions (Kaplan and Tripsas, 2008). Given the current marketing strategy continued to yield good results, the management did not see the need for change, especially a change that did not seem to bring any ‘short term’ benefits. Lack of institutional endorsement from the senior management, employees in MRetailer could not appreciate the value of CRM and not appropriate the system for sales and marketing. Effective communication and appropriate amount of training about the technology are ways can help align and reduce discrepancies among elements of frames (Raman et al., 2006). Only when both the management and staff involvement in the implementation process and buy in with the CRM technology, the benefits of CRM can be realized (Raman et al., 2006).

6. CONCLUSION

This study has demonstrated that although technological frames are individually held, they are also social phenomena shared by individuals (Orlikowski and Gash, 1994). Institutional analyses which are concerned with shared and taken-for-granted social rules are proved to be helpful in terms of understanding how the social cognition (technological frames) is structured. The study has also shown that the shared frames created through the dominant social rules can replace technological frames held by individuals to become the dominant frames in a company. It is shown that the social rules produced cognitive inertia that prevented the company from adopting the new ideas and technology that differed from the organisational status quo.

The study contributes to the current literature in three areas. First, it shows the possibility of using institutional theories to study the contexts in which technological frames

are formed. The theories show how organisational institutions, such as incentive systems and cognitive structures, can significantly influence or even dominate how people view and use the system. The institution perspective may help explain the congruence of technological frames in an organisation by pointing out that it is not the result of the shared interests or background but of the dominance of some organisational institutions. Identifying these key institutions may help explain why even with careful system design and expected benefits, an IS may still not be used by the adopting organisations. Second, the study shows that frame incongruence may not necessary be a critical issue (Karsten and Laine, 2007) leading to implementation failure; however frame congruence (e.g., technology in use) can be an issue when most people in an organisation frame the technology in one dimension. This issue has not yet been addressed in the literature thus far and it is worthy of further investigation.

REFERENCE

[1] S.R. Barley, P.S. Tolbert, Institutionalization and structuration: Studying the links between action and institution, Organisation Studies 18(1), 1997, pp. 93-117.

[2] M. Biehl, Success factors for implementing global information systems. Communication of the ACM 50(1), 2007, pp.52-58.

[3] W.E. Bijker, Of bicycles, bakelites, and bulbs: Toward a theory of sociotechnical change, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1995.

[4] E. Davidson, M. Chiasson, Contextual influences on technology use mediation: a comparative analysis of electronic medical record systems, European Journal of Information Systems 14(1), 2005, pp. 6-18.

[5] C.J. Davis, E.M. Hufnagel, Through the eyes of experts: a socio-cognitive perspective on the automation of fingerprint work, MIS Quarterly 31(4), 2007, pp. 681-703.

[6] E.L. Deci, R.M. Ryan, The general causality orientations scale: self-determination in personality, Journal of Research in Personality 19, 1985, pp. 109-134.

[7] E. Goffman, Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience, Harper & Row, New York, 1974.

[8] S. Kaplan, M. Tripsas, Thinking about technology: applying a cognitive lens to technical change, Research Policy 37(5), 2008, pp. 790-805.

[9] H. Karsten, A. Laine, User Interpretation of future information system use: A snapshot with technological frames, International Journal of Medical Informatics 76(Supplement), 2007, pp.136-40.

[10] E. Karahanna, R. Garwal, C. Angst, Reconceptualizing compatibility beliefs in technology acceptance research. MIS Quarterly, 30(4), 2006, pp. 781-804.

[11] R. Kling, R. Lamb, IT and organizational change in digital economies: A sociotechnical approach. In E. Brynjolfsson, B. Kahin (Eds.) Understanding the Digital Economy: Data, Tools and Research. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2000, pp. 295-324.

[12] R. Lamb, R. Kling, Reconceptualizing users as social actors in information systems research, MIS Quarterly 27(2), 2003, pp. 197-235

[13] H. Markus, R.B. Zajonc, The Cognitive Perspective in Social Psychology, in The Handbook of Social Psychology Volume 1, G. Lindzey, E. Aronson (Eds.), Random House, New York, 1985, pp. 137-230.

[14] T. McGovern, C. Hicks, How political processes shaped the IT adopted by a small make-to-order company: a case study in the insulated wire and cable industry, Information & Management 42(1), 2004, pp. 243-257.

[15] I. Mcloughlin, M. Harris, Understanding innovation, organizational change and technology, in I. Mcloughlin, M. Harris (Eds.), Organization Change and Technology, International Thomson Business Press, London, 1997.

[16] R. Nelson, B. Sampat, Making sense of institutions as a factor shaping economic performance, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 44(1), 2001, pp. 31-54. [17] D.C. North, Transaction costs, institutions, and economic performance, International

Centre for Economic Growth, San Francisco, 1990.

[18] W.J. Orlikowski, D.C. Gash, Changing frames: Understanding technological changes in organisations, Centre for Information Systems Research, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 1991. [19] W.J. Orlikowski, D.C. Gash, Technological frames: Making sense of information

technology in organisations, ACM Transactions on Information Systems 12(2), 1994, pp. 174-206.

[20] W.J. Orlikowksi, S. Iacono, Research commentary: Desperately seeking the "it" in IT research—a call to theorizing the IT artifact. Information Systems Research, 12(2), 2000, pp.121-34.

[21] T.F. Pinch, W.E. Bijker, The Social Construction of Facts and Artifacts: Or How the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each Other. in W.

E. Bijker, T. Hughes, T. Pinch (Eds.) The Social Construction of Technological Systems. Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press, 1987, pp. 17-49.

[22] W.W. Powell and P.J. DiMaggio. The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1991.

[23] P. Raman, C.M. Wittmann, N.A. Rauseo, Leveraging CRM for sales: the role of organizational capabilities in successful CRM implementation, The Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26(1), 2006, pp. 39-53.

[24] W.R. Scott, Institution and organisation, Sage, Thousand Oaks, 2001.

[25] C. Standing, I. Sims, P. Love, IT non-conformity in institutional environments: E-marketplace adoption in the government sector, Information & Management, 46(2), 2009, pp. 138-149.

[26] M. Tyre, W.J. Orlikowski Windows of Opportunity: Creating Occasions for Technological Adaptation in Organisations. Organization Science 5(1), 1994, pp.98-118.

[27] G. Walsham, Doing interpretive research, European Journal of Information Systems 15(3), 2006, pp. 320-333.

[28] D. Zahay, A. Griffin, Customer learning processes, strategy selection, and performance in business-to-business service firms, Decision Sciences 35(2), 2004, pp. 169-203.