+

(,1 1/,1(

2

Citation: 3 NTU L. Rev. 47 2008

Content downloaded/printed from

HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org)

Sat Nov 20 03:53:20 2010

-- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance

of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license

agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License

-- The search text of this PDF is generated from

Article

The Constraint of Government Procurement

Law in Dealing with Misuse of Dominant

Power in Government Procurement Market:

An Organic Cooperative Relation between the

Law and the Competition Legislation

Enlightened by a Dispute Settlement Case in

Taiwan

Chang-Fa Lo"

CONTENTS

I. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ... 49 II. THE BID CHALLENGE PROCEDURE UNDER GPL ... 50 III. THE BACKGROUND OF THE CASE AND THE ALLEGATION BY THE

COM PLAINANT ... 53

IV. THE DECISION OF THE CRBGP ... 55 V. DYNAMIC LINE DRAWN BY THE DECISION BETWEEN THE Two

LAWS AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF COOPERATIVE RELATIONSHIP

BETWEEN THE Two AGENCIES ... 60 A . The Line ... 60

B. The Nature of the Line Being Dynamic ... 61

48 National Taiwan University Law Review [Vol. 3: 1

C. Cooperation between the Two Laws and between the

Enforcement Agencies of these Two Legislations ... 62

VI. CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 64 R EFERENCES ... 65

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 49

Market

I. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION

One of the purposes of government procurement rules in different countries is to ensure that there will be appropriate competition within their respective government procurement markets. Through proper competition, the procuring agencies are supposedly able to secure products or services with better quality and with lower or more reasonable prices. Thus, in some jurisdictions, government procurement matters are governed by competition law due to the fact that ensuring competition is of essence in government procurement matters.

A typical example is that of Germany, which integrates government

procurement rules into its competition law in 1999. As explained in an article, "German procurement law has traditionally been part of administrative law and not competition law, and therefore focused on budgetary issues, without guaranteeing individual rights and legal remedies for applicants and bidders .... In order to fulfill the requirements set by several European Directives aimed at the opening of public procurement for Community-wide competition, the rules on government procurement have been amended and incorporated into the GWB,"' the competition law of Germany. Articles 97 through 129 of GWB are the provisions dealing with government procurement matters.

However, Taiwan adopted different approach in this regard. In Taiwan, there is a separate legislation for government procurement matters independent from its competition law, i.e. the Fair Trade Law (FTL).3

Prior to the enactment of its government procurement legislation, the Fair Trade Law was actively applied by the Fair Trade Commission, which is the authority in charge of competition law enforcement, to deal with bid-rigging by suppliers or potential suppliers and to deal with discrimination by procuring entities through setting overly strict or unfair specifications or qualifications. In 1998, the Government Procurement Law (GPL) of Taiwan was enacted to deal with bid-rigging and discriminations, among other things.

Although it is clear that the GPL is applicable to activities affecting the competitions in government procurement market, there are still problems arising from the application of the GPL in anticompetitive activities.

1. Joachim Rudo, The 1999 Amendments to the German Act Against Restraints of Competition. Available at http://www.antitrust.de/. Last visited on July 3, 2006.

2. "GWB" stands for "Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschrinkungen," which is the German Act against Restraints of Competition.

3. The text of the Fair Trade Law is available at http://www.ftc.gov.tw/. Last visited on May

National Taiwan University Law Review

The paper is to use a bid challenge case under the GPL to illustrate the constraint of the GPL in dealing with some anti-competitive practices and the need to establish a closer cooperative relation between the enforcement agencies under the GPL and under the FTL in dealing with such constraint.

II. THE BID CHALLENGE PROCEDURE UNDER GPL

Although the GPL was enacted in 1998, it was not enforced until 1999 for the purpose of providing one year transition period to allow government agencies and suppliers to adjust themselves. There were the two-fold backgrounds of the enactment of the Law. Domestically, the GPL was enacted to correct the then prevalent irregularities involved in the government procurement activities. Internationally, the enactment of the GPL was to fulfil the commitments of the Government of Taiwan made during its accession negotiations to join the World Trade Organization (WTO).4 The commitments include the enactment of the Government Procurement Law to streamline the government procurement process based on the Government Procurement Agreement.5 Thus, the GPL basically follows the rules of the Agreement in setting up three types of tendering procedures, namely the open tendering procedure, the selective tendering procedures and the limited tendering procedures. Under paragraph 2 of Article XX of the Agreement, each Party of the Agreement shall provide non-discriminatory, timely, transparent and effective procedures enabling suppliers to challenge alleged breaches of the Agreement arising in the context of procurements in which they have, or have had, an interest.6

Because of the provision of Article XX in the Agreement, the GPL thus includes Chapter VI "Dispute Settlement," which provides in Article 74 that: "For any dispute between an entity and a supplier arising out of the invitation to tender, the evaluation of tender, or the award of contract, a protest or complaint may be filed in accordance with this Chapter." There are two steps for the supplier or potential supplier to have their

4. Although, the Government Procurement Agreement is prulilateral agreement (meaning that WTO Members are not obligated to become a signatory to the Agreement), Taiwan was expected to join the Agreement by some WTO Members. As a result, Taiwan agreed to enact its Government Procurement Law to reflect the procurement rules prescribed under the Agreement. The legal text of Government Procurement Agreement and a brief introduction of the Agreement is available at the WTO website at http://www.wto.org/english/tratope/gproce/gpgpae.htm. Last visited on July 2, 2006.

5. See paragraphs 164-166 of the Working Party Report for the WTO accession of Taiwan, available at the website of the Bureau of Foreign Trade, Ministry of Economic Affairs at http://cwto.trade.gov.tw/kmi.asp?xdurl=kmif.asp&cat--CAT313. Last visited on May 7, 2008.

6. The text of the Government Procurement Agreement is available at http://www.wto.org/ englishtdocse/legal-e/legal_e.htm. Last visited on May 7, 2008.

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 51

Market

grievance heard and settled, namely, protest and complaint. Article 75 has provisions to allow the private parties to lodge a protest with the procuring entity and Article 76 governs complaints that are to be made with the especially established complaint reviewed organization.7

Article 75 states:

"A supplier may ... file a protest in writing with an entity if the supplier deems that the entity is in breach of laws or regulations or of a treaty or an agreement to which this nation is a party... so as to impair the supplier's rights or interest in a procurement." "The entity inviting tenders shall make proper disposition and notify the protesting supplier in writing of such disposition within 15 days from the date following the date of receipt of the

protest ..."

Article 76 further provides that:

"Where the value of procurement reaches the threshold for publication [i.e. NTD1,000,000], a supplier may file a written complaint with the Complaint Review Board for Government Procurement ["CRBGP" or "Complaint Review Board"] as established by the responsible entity [i.e. Public Construction Commission], or the municipal or the county (city) governments, depending upon whether the procurement is conducted at the level of central government or local government, within fifteen days from the date following the date of receipt of the disposition if the supplier objects to the disposition, or from the expiry of the period specified in paragraph 2 of the preceding Article if the entity fails to dispose the case within the period ..."

The complaint system under the GPL has played very important role in ensuring the observance of the Law by procuring entities. This can be partly reflected by the number of cases handled by the CRBGP for the past years ever since the putting into practice of the Law.

7. The text of the law is available at http://www.pcc.gov.tw/cht/index.php?. Last visited on May 7, 2008.

National Taiwan University Law Review

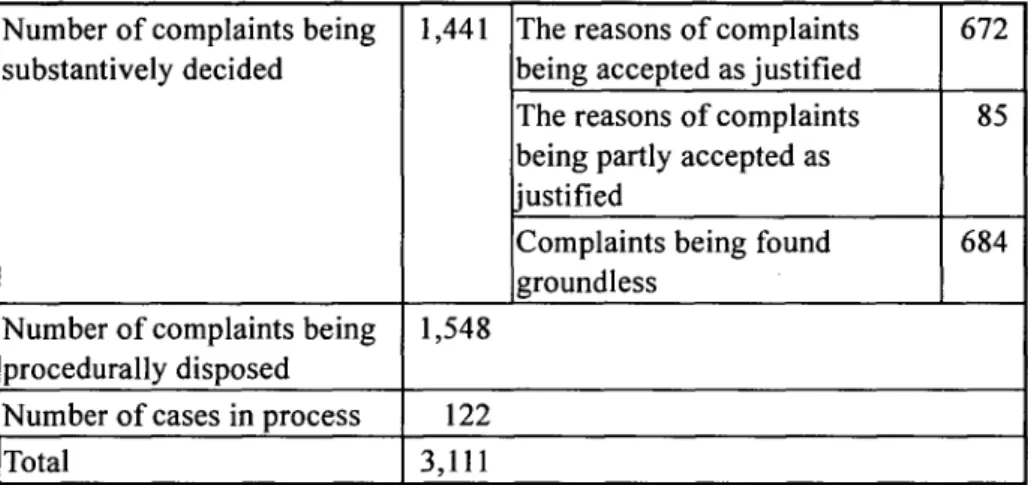

Table 1 Number of Complaints between May 27, 1999 and December 31, 20058

Number of complaints received 3,111

jNumber of complaints substantively 2,989

decided or procedurally disposed

Number of cases in process 122

Table 2 Results of the Complaint between May 27, 1999 and December 31,

2005

9Number of complaints being 1,441 The reasons of complaints 672

substantively decided being accepted as justified

The reasons of complaints 85

being partly accepted as justified

Complaints being found 684

groundless Number of complaints being 1,548

procedurally disposed

Number of cases in process 122

Total 3,111

From the above tables, it is clearly that for the cases being substantively decided by the CRBGP, about half of the complaints by the suppliers are considered to be with good reasons justifying their complaints. If we include those complaints with their reasons being partly justified, the percentage for the suppliers wining the complaint cases was way above half of the total complaints being substantively decided by the CRBGP. The total number of complaints has shown the active intervention of the procurement procedures by the Complaint Review Board. And the high percentage for the complaining parties wining the cases has also shown that the dispute settlement system has played a vital role in ensuring the enforcement of the GPL and the integrity of the Law.

Notwithstanding the strength of the complaint procedure, there is structural problem of the complaint system. One of the structural

8. The statistics are cited from Public Construction Commission, Public Construction Annual

Report 2006, available at http://www.arteck.com.tw/2006/index.html. Last visited on July 10,

2006. Note that the number of complaint includes not only the complaints under Article 75, but also complaints against the notifications by procuring entities for the purpose of prohibiting the suppliers from participating government procurements for one or three years, depending upon the causes of prohibition being breaches of contract or being breaches of law. See Articles 101 to 103 of the GPL.

9. Id.

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 53

Market

problems is in the relations between the procuring entities and CRBGP on the one hand and the Fair Trade Commission on the other, as well as the relations between these two legislations. The case explained in this paper is about the appropriateness and competency of procuring entities and the CRBGP to deal with anti-competitive activities. The paper does not suggest that for this particular case, the alleged misuse of monopolistic power by the winner of this particular government project was in fact a violation of the Fair Trade Law or the GPL. However, this case is an appropriate example to illustrate the structural limit of the GPL in dealing anti-competitive business practices. The case has drawn the line between the enforcement of the competition law by the competition authority, i.e. the Fair Trade Commission, in securing the orderly competition in the market, and the implementation of the GPL by the CRBGP in ensuring the observance of the government procurement rules.

III. THE BACKGROUND OF THE CASE AND THE ALLEGATION BY THE COMPLAINANT

This case is about a procurement project 0 of "Natural Gas for the

Use of Power Generation at Da-Tan Power Plant."'" The procuring entity was Taiwan Power Company (Taipower),12 which decided to procure natural gas supply for its Da-Tan Power Plant for power generation purpose. In addition to the complainant,' 3 Chinese Petroleum Corp. (CPC) was also the competitor in the procurement process. Taipower decided to award the contract to CPC for the reason that CPC offered lowest prices for the supply of natural gas. The complainant considered that Taipower should reject the bidding from CPC, because, as alleged by the complainant, CPC had misused its market power to set its price at overly low level to win this big project. The legal basis alleged by the complainant is paragraphs 1 and 2 of Article 50 of the GPL, which provides that:

"In case that any of the following circumstances occurs to a tenderer, an entity shall not open the tender of such tenderer when such circumstance is found before tender opening, nor shall

10. The nature and contents of the Da-Tan Power Plant project is available at http:/Iwww.

moea.gov.tw/-meco/icd/majoroperation/images/state-run.pdf. Last visited on May 7, 2008. 11. Case number with the CRBGP for the case is Su No. 92410. It was decided by the Board in 2003. The author of this paper helped to draft the decision. Thus the main reasoning was proposed by the author.

12. Taipower is a state-own enterprise. Under Article 3 of the GPL, procurements conducted by state-owned enterprises are also governed by this law.

13. Transliteration of the complainant's name being Preparatory Office for Lian-he-zi-neng-xin-ye Co., Ltd.

National Taiwan University Law Review

award the contract to such tenderer when such circumstance is found after tender opening: 1. the tendering does not comply with the requirements of the tender documentation; 2. the content of the tender is inconsistent with the requirements of the tender documentation; 3. the tenderer borrows or assumes any other's name or certificate to tender, or tenderwith forged documents or documents with unauthorized alteration; 4. the tenderer forges

documents or alters documents without authorization in

tendering; 5. the contents of the tender documents submitted by different tenderers show a substantial and unusual connection; 6. the tenderer is prohibited from participating in tendering or being awarded of any contract pursuant to paragraphl of Article 103 hereof; or 7. the tenderer is engaged in any other activities in breach of laws or regulations which impair the fairness of the procurement."

"When any of the circumstances referred to in the preceding paragraph occurs to the winning tenderer before the award of contract but is found after award or signing of the contract, the entity shall revoke the award, terminate or rescind the contract, and may claim for damages against such tenderer except where the revocation of the award or the termination or rescission of the contract is against public interests, and is approved by the superior entity."

The complainant argued that Taipower shall not open the tender of CPC, because CPC had violated subparagraph 7 of paragraph 1 of Article 50 by breaching the Fair Trade Law and thus having impaired the fairness of the procurement. According to the complainant, CPC had already increased three times of the price for natural gas for industrial and household uses as well as for all other users of natural gas in 2003. The most recent increase was made even within ten days after the awarding of the contract by Taipower to CPC. Contrary to its practice of increasing the prices during the period, CPC submitted very low prices for the purpose of wining the project. This has shown that the submission of low prices by CPC to Taipower to win the contract was to exclude other competitors to enter the market. CPC also charged high prices from other users of natural gas for the purpose of subsidizing the possible losses arising from overly low prices submitted by CPC. CPC being a monopolistic supplier of natural gas in domestic market and misusing its market position to unfairly engage in competition had violated subparagraph 4 of Article 10 of the Fair Trade Law, which provides that "[n]o monopolistic enterprise may engage in any of the following activities: ... 4. other activities of misusing market position." Since Taipower being the procuring entity [Vol. 3: 1

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 55

Market

together with CPC are state-own enterprises under the governance of Ministry of Economic Affairs, also since Taipower had been the largest buyer of natural gas supplied by CPC, it is not possible for Taipower not to have knowledge that CPC had been misusing its market power by setting very low prices to secure the contract. The complainant further alleged that Taipower should apply subparagraph 7 of paragraph 1 of Article 50 to refuse awarding the contract to CPC. Even after the award, according to the complainant, Taipower must apply paragraph 2 of Article 50 to withdraw awarding the contract to CPC.

IV. THE DECISION OF THE CRBGP

The Complaint Review Board did not accept the argument of the complainant. It firstly clarified the meaning of "laws and regulations" in Article 50 of the GPL and states the following:

"Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 only specifies that before or after opening the tenders, if it finds that there is a tenderer engaging in any activities in breach of laws or regulations which impairs the fairness of the procurement, the procuring agency shall not open the tenders or not award the project to such tenderer. There is no explicit indication about what kind of laws or regulations it is referring to. Thus, it is legally acceptable that as long as the breach of laws or regulations will affect the fairness of procurement, such laws or regulations should be the kind within the scope of this provision. Therefore, if there is a breach of the Fair Trade Law and if such breach does affect the fairness of procurement, there is no reason not to include such situation in the provision. However, the term 'breach' used here shall mean the situation where the procuring agency is able to make judgment based on the tendering documents submitted by the tenderer, or based on the documents possessed by the procuring agency, or based on the available documents that can be obtained by the procuring entity through conducting a general verification. Suppose there is a need to go through a very detailed investigation and very sophisticated legal and economic analyses, the Law does not expect the procuring entity to make such finding and judgment during the tendering process, unless there has been a decision about the illegality of relevant activities by competent authority readily available for the procuring entity to make its decision."

National Taiwan University Law Review

supplementary in their respective functions. If there is a violation of the Fair Trade Law by a supplier and if the violation would create such unfairness on a particular government procurement project, the GPL will be able to intervene. However, the Decision also set up certain procedural thresholds or criteria to qualify the application of GPL in dealing with alleged anti-competitive practice in violation of the Fair Trade Law. Under the Decision, there are three situations where the GPL will be applied in this regard, namely, that the tendering documents is sufficient to make judgment on whether there is a breach of the Fair Trade Law, that the documents already possessed by the procuring agency is sufficient to make such judgment, and that the procuring agency is able to verify in a generally way so as to obtain information confirming the breach of the Fair Trade Law. Although there is no explicit basis in the GPL to set forth such thresholds or criteria for the procuring entity to make such judgment, it is set based on the nature of the procurement activities and the nature of a violation of the Fair Trade Law. The Decision thus further explained the nature of a violation of the Fair Trade Law:

"Generally, whether there is a violation of the Fair Trade Law, including whether a company is a monopoly and whether such company has misused its monopolistic position to conduct predatory pricing activities, is a matter that needs to be decided by the Fair Trade Commission and the courts in accordance with the materials and evidences collected through investigations under the powers vested to them. For instance, according to Article 27, the Fair Trade Commission may require relevant parties and interested parties to come to the Commission to make statements or to answer questions. It may also require relevant agencies, organizations, enterprises or individuals to submit accounting books, documents or other relevant materials or things produced as evidence. If the requested parties refuse to accept investigation, to come to answer questions or to make statement, or to submit accounting books, documents or materials, the Fair Trade Commission may impose administrative fines in a consecutive way. The courts also have powers vested by law to investigate. The evidences and materials collected and investigated by the court must include the definition and structure of the relevant market, the competitive situation and positions of relevant firms in the market, the implication of prices in relevant market, among other things. If it involves cases concerning Article 10 (Monopoly), the Fair Trade Commission will normally have to take much longer time to collect evidence and to make analysis and judgment to decide the market impact of an act and

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 57

Market

to decide whether Article 10 has been breached. Contrary to the situation of the Fair Trade Commission and the courts, the procuring agency does not have such power to collect necessary information and conduct investigation necessary to decide whether there is a violation of Article 10. Neither does it have the expertise to engage in a very specialized legal and economic analysis. Also, the procuring entity needs to make decision before opening the tenders or awarding the project. There is no sufficient time for it to make such complicated decision."

The Decision compared the differences between the position of the procuring entity and that of the Fair Trade Commission and the courts about their respective powers, resources, and expertises. In essence, a finding on an activity being in violation of the Fair Trade Law involved prolonged and sophisticated investigation analyses. There is a high demand for legal authorities, manpower and expertises to conduct meaningful and effective investigation as well as analyses. As a matter of law and practice, the procuring entity would never have such authorities, manpower and expertises to conduct such investigation and analyses. Neither does a procuring entity has such time to conduct such investigation and analyses if it is going to have an efficient procurement. Therefore, the Decision further explained the appropriateness of setting the criteria for the procuring entity to make their determination.

"Since there involves investigations conducted by law enforcement agency and sophisticated legal and economic analysis as well as findings under Article 10 of the Fair Trade Law, the Government Procurement Law cannot expect the procuring entity to engage in investigation, analysis and findings with the level similar to those by the Fair Trade Commission. It would be more appropriate to see whether from the documents submitted by the tenderers, from the materials possessed by the procuring agency, or from information that may become available through general verification, the procuring agency is in a position to decide the illegality of the violation. The Complaint Review Board should review the decision of procuring agency based upon the same standard. Under this standard, an issue needs to be further decided is whether the procuring entity was able to find the tenderer had breached the Fair Trade Law purely based on the tendering materials submitted by the tenderers (especially CPC), on the materials possessed by the procuring entity, or on the results of a general verification by the procuring entity."

National Taiwan University Law Review

The Decision reiterated the criteria for the procuring entity to apply the Fair Trade Law and to find a breach of that law, i.e. whether from the documents submitted by the tenderers, from the materials possessed by the procuring agency, or from information that may become available through general verification, the procuring agency is in a position to decide the illegality of the violation. Since the Complaint Review Board is to determine whether the procuring activities are in full conformity with the GPL, thus when the Board review the determination of Taipower, it should also follow the same criteria. Based on this premise, the Decision defined the complaint being to challenge the pricing practice of CPC and explained the criteria of finding a predatory pricing activity being in violation of Article 10 of the Fair Trade Law.

"In this case, although the complainant alleged that CPC violated subparagraph 4 of Article 10 (tenderer being engaged in any other activities in breach of laws or regulations which impair the fairness of the procurement), it was in fact alleging the CPC had engaged in illegal price decision. Therefore, the real issue to be decided is whether CPC has engaged in a predatory pricing activity. When deciding whether there is a predatory pricing activity under Article 10, a review must be made on the costs of the investigated firm, the net profits under such price and the effect on its competitors under such price. Some are of the view that the review of the costs needs to be focused on whether the price is lower than marginal costs to see whether there is predatory nature. Some people consider that it is more appropriate to use average variable costs to replace marginal costs. In any event, when determining whether CPC had committed predatory pricing, there must be analyses on marginal costs or average variable costs for the purpose of deciding the nature of the price. In this case, it is very doubtful that the procuring entity was able to make such analyses on marginal costs or average variable costs during the procuring process based on materials submitted by the tenderers or possessed by the procuring agency or based on the materials that can be obtained through general verification. ... Furthermore, one of the important indicators of predatory pricing is to see the net profits of the firm under such price. If the price only produces very limited effect on the ability of the investigated firm to make profit and the capability of making profits has not been reduced in an apparent manner as a result of such price reduction; to the contrary, if the result of the price is that increased profits are able to offset the losses arising from the reduced profits, the pricing

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 59

Market

policy can generally be considered as normal competition, not a predatory pricing activity. In this case, even if the import costs, the current prices of natural gas, and the bidding prices of CPC alleged by the complainant were correct, it is still very doubtful whether the procuring entity was able to know or to make analysis the decrease of profit-making ability of CPC based upon such tendering prices. In other words, it is not possible for the procuring entity to find that the bidding prices of CPC had been lower than its marginal costs or average variable costs or had apparently impaired the profit-making ability purely based on the bidding materials submitted by tenderers, on the materials possessed by the procuring entity, or on the result that could be obtained through general verification by the procuring entity."

The Decision avoided a finding of CPC being a monopolistic enterprise under the Fair Trade Law, but focusing on the requirements of pricing policy. There are different views about the meaning of predatory pricing conducted by an enterprise having monopolistic or dominant market position. Some consider that it would be more appropriate to use marginal costs as a benchmark to see whether a price is with predatory nature. Some others consider being more appropriate to use average variable costs as the benchmark. There is no consensus about the proper definition of predatory pricing.'4 Of course, there are additional views on this. The Decision did not take a position on this, but only to indicate that no matter what view was most appropriate from the standpoint of competition policy, the procuring entity was not in a position to conduct analyses on the cost aspects during the procuring process. The Decision also indicated the impracticality of expecting the procuring entity to decide whether there was such effect on the ability of supplier to make profits arising from low prices. In other words, the Complaint Review Board was in no position to find the procuring entity (Taipower) being violating the law by not applying the GPL and it concluded that:

"Since there is no evidence to show that the procuring entity should find that CPC was in violation of the provision concerning misuse of monopolistic position under Article 10, subparagraph 4 during the procuring process or at the time when the project was awarded to CPC, the allegations of complainant about CPC's misuse of monopolistic market power through low prices to seize the project for the purpose of maintaining the monopolistic

14. Paul Stephen Dempsey, Predation, Competition & Antitrust Law: Turbulence in the

National Taiwan University Law Review

position in domestic liquefied natural gas market and about the violation of Article 10 of the Fair Trade Law as well as it having met the requirements of Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 are all groundless."

V. DYNAMIC LINE DRAWN BY THE DECISION BETWEEN THE Two LAWS AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF COOPERATIVE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE TWO AGENCIES

A. The Line

There is a clear line drawn by the Complaint Review Board on the application of the Fair Trade Law through the application of the GPL. On the one hand, the Decision of the Board admitted that if there is a violation of the Fair Trade Law that would cause unfairness of the procurement process, such violation should also be covered by Article 50 of the GPL. In other words, it is not appropriate for any one to assert that the GPL and the Fair Trade Law are two different legislations and have their respective jurisdictions and thus they do not intervene in each other's field. As a matter of law, these two laws supplement each other.

There are different purposes of having the GPL. As indicated in Article 1 of this law, the government procurement system is designed to have fair and open procurement procedures, to promote the efficiency and effectiveness of government procurement operation, and to ensure the quality of procurement. In essence, the requirement of fair and open procedures is to ensure competition of suppliers in the government

procurement market. The efficiency, effectiveness and quality

requirements are more of the expectation of ensuring the best interests of the government agencies being secured. Thus, one of the purposes of the GPL is to guarantee that there will be proper competition in the government procurement market. This coincides with the purpose of the Fair Trade Law, the main purpose of which is to promote competition in the market. In a way, the GPL serves as a supplementary legislation to the Fair Trade Law.

In turn, the Fair Trade Law also supplements the application of GPL and the fulfillment of the legislation goal of the GPL. Article 50 is a very good example to show such relations. Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 has linked the GPL with other legislations so as to ensure that the whole process of a government procurement will not be trampled and the fairness will not be jeopardized by any supplier who participates the tendering procedure. The relation between the GPL and the Fair Trade Law in this regard has been confirmed by the Decision of the Complaint Review Board.

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 61

Market

However, more importantly, the Decision set up procedural criteria to limit the application of Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 due to the nature of the government procedure and due to the constraint of the procuring entities. The essence in the Decision is not to expect procuring entity to engage in prolonged investigation. This is to ensure that the efficiency of procurement expected under Article 1 of the GPL will not be sacrificed because of a complaint alleging a supplier being in violation of the Fair Trade Law. After all, the procuring entity is not a government authority in charge of competition policy and being responsible for the fair competition in the government procurement market. Any expectation on the procuring entity to conduct detailed investigation about an alleged violation of the competition legislation would be overly high.

This does not mean that the procuring entity would not have any obligation to determine a breach of the Fair Trade Law by the suppler. The Decision set forth a three-plunged standard to allow and to instruct the procuring entity to make finding about whether there is a violation of the Fair Trade Law by a supplier, namely, whether the procuring agency is able to make judgment based on the tendering documents submitted by the tenderer, or based on the documents possessed by the procuring agency, or based on the available documents that can be obtained by the procuring entity through conducting a general verification.

B. The Nature of the Line Being Dynamic

This three-plunged standard is procedural requirements. The line drawn by the Decision is to instruct the procuring entities to make substantive finding under certain circumstances. The standard is dynamic in nature. Based upon the move of different players, the line could have different functions.

The first variation is the tenderers. The tenderers can submit sufficient information to enable the procuring entity to make judgment on whether a breach of the Fair Trade Law has been in place. However, since a finding of a violation of the competition law would involve detailed and sophisticated legal and economic analyses, as explained above, it is should be very rare for the procuring entity to secure sufficient information from the tenderers for the purpose of making such finding.

The second and third variations are whether the procuring entity has possessed the necessary documents and whether the procuring entity is able to conduct a general verification to obtain necessary document enabling it to make such finding. Although it should not be very often for the procuring entity to, adventitiously, possess the necessary document or information, it should be very practical for the procuring entity to seek for information or documents from the competent authority of the

National Taiwan University Law Review

competition law for the purpose of making a finding on the issues. In other words, the standard does give the procuring entity the necessary position and opportunity to secure supporting documents from the Fair Trade Commission. Thus there involve two variations here. The first one is whether the procuring entity would be enthusiastic enough to seek for supporting information or documents from the Fair Trade Commission. And the second one is whether the Fair Trade Commission would be willing to provide help to the procuring entity in discharging it obligation.

C. Cooperation between the Two Laws and between the Enforcement Agencies of these Two Legislations

Apparently, government procurement market is a market that needs to be subject to competition rules. This has been indirectly instructed by the Decision, which manifestly stated that violation by a supplier of the Fair Trade Law is also a violation of Article 50 of the GPL and thus the procuring entity should be in a legal position and should have such obligation to refuse awarding the contract to such supplier. However, when it turned to practical consideration, the Decision cannot but admit that the procuring entity should not be expected to engage in a very detailed and prolonged investigation on and analyses about the possible violation of the Fair Trade Law. If it is always the case that the procuring entity would never be able to make finding about a violation of the Fair Trade Law by a tenderer, then Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 would be of no value. Thus the Decision set forth some criteria for the procuring entity to acquire a position to make such finding.

Since the fulfillment of the requirements are basically depending upon the moves of different players in the whole process, certain rules set forth for the purpose of making effective of the cooperation would be necessary. In the view of this paper, cooperation between the Fair Trade Commission on the one hand and the procuring entity and the Complaint Review Board on the other should be of essence in making effective application of Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 of the GPL.15

As a matter of fact, before making this particular Decision, the CRBGP had issued a letter through the Public Construction Commission to the Fair Trade Commission to ask for its assistance in deciding the application of Article 10 of the Fair Trade Law. However, the Fair Trade Commission failed to provide necessary assistance on the finding on the

15. When the GPL was enacted, the Fair Trade Commission and the Public Construction

Commission concluded an agreement about the application of the GPL and FTL regarding their overlapping areas. However, the contents and nature of the agreement were mainly about the division of labor between the two agencies. It did not touch upon the possible cooperative aspect so as to help the enforcement of their respective duties under the laws.

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 63

Market

part of Fair Trade Law.'6 This has shown the passive attitude on the enforcement of other legislations by other agencies having connections with competition policy. Because of the position, the Fair Trade Commission has forgone a very important prospect of establishing a cooperative connection with the entities in charge of procuring matters.

The paper is of the view that an organic relation can be established for two purposes, namely, to help the enforcement of Article 50 of the GPL by procuring entity and the Complaint Review Board and to carry through the competition policy embodied in the legislations outside the Fair Trade Law.

The relation being considered as organic is because it requires positive moves and positive reactions in order to make it work. There must be the following features included in such organic relation between the two legislations, and as a result, between these two sets of agencies.

First, it is needed for the Fair Trade Commission to formulate a set of guidelines to declare to other government agencies that when other government agencies enforce their respective laws and regulation and when there is competition policy involved, there is such channel for these agencies to look for expert views on the interpretation of the laws and regulations from the perspective of competition authority and even to request assistance in investigating the relevant activities. Since there are so many legislations involving competition policy and since not many government agencies are with such expertise in making appropriate finding about the relevant activities and the application of competition related laws, the only effective way of ensuring the carrying out of competition policy in a proper manner is to have more positive intervention of the law enforcement and law application activities of other government agencies by the FTL and the Fair Trade Commission. A set of such guidelines would help procuring entities and the Complaint Review Board to positively consider referring the issues to the Fair Trade Commission for expert views and helps.

Second, from the perspective of the procurement system, there is also a need to establish a closer connection between Article 50 of the GPL and the FTL. Although it has been declared by the above Decision that Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 of the GPL should cover the violations of the Fair Trade Law, if there is no further move to enhance the application, this particular provision will eventually become ineffectual. The authority in charge of the GPL, i.e. the Public Construction Commission, is in a good position to issue a working procedure to streamline the application of Article 50. The contents are basically to clarify the coverage of the "laws and regulations" and specify that they include the Fair Trade Law.

National Taiwan University Law Review

This is to confirm the views expressed in the above Decision and to make it a general rule for the application of the procuring entities. The contents are also to include the situations where the procuring entities would be able to make its decisions and where they have to request assistances from the Fair Trade Commission. Basically, the three-plunged criteria set forth in the above Decision could be the basis of formulating the different situations.

VI. CONCLUDING REMARKS

As stated in the outset of the paper, one of the purposes of the GPL is to ensure proper competition in the government procurement market. One way of ensuring the proper competition in the government procurement market is through the application of Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 of the GPL. However, there involves practical difficulties for procuring entities and the Complaint Review Board to apply this particular provision.

The above mentioned Decision as pointed out such difficulties. It also established procedural criteria for procuring entities to apply this provision. The criteria are of great value in helping clarifying the relations between the GPL and the FTL and of practical use in instructing the future application of the provision.

However, if there is no further cooperative arrangement established between the two legislations and between the enforcement agencies under these two legislations, the application of Article 50, paragraph 1, subparagraph 7 of the GPL by procuring entities in relations to breach of competition law would not be very likely.

The paper tries to point out the difficulties and to formulate a framework for the purpose of establishing an organic relation between the two sets of legislations and two sets of government agencies with the hope that there will be proper competition principles brought into the government procurement market through the application of this particular provision in the GPL.

The Constraint of Government Procurement Law in Dealing

2008] with Misuse of Dominant Power in Government Procurement 65

Market

REFERENCES

Dempsey, Paul Stephen (2002), Predation, Competition & Antitrust Law:

Turbulence in the Airline Industry, 67 J. AIR L. & COM. 685

(Summer 2002).

Public Construction Commission, Public Construction Annual Report

2006, available at http://www.arteck.com. tw/2006/index.html.

Rudo, Joachim, The 1999 Amendments to the German Act Against

Restraints of Competition, available at http://www.antitrust.de/.

Working Party Report for the WTO accession of Taiwan, available at http://cwto.trade.gov.tw/kmi.asp?xdurl=kmif. asp&cat=CAT313. http://www.ftc.gov.tw/. http://www.wto.org/english/tratop e/gproce/gpgpa-e.htm. http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal e/legal_e.htm. http://www.pcc.gov.tw/cht/index.php. http://www.moea.gov.tw/-meco/icd/majoroperation/images/state-run.pdf.