中華心理衛生學刊

第十六卷(2003) 第四期 頁83-107

研

究

論

文

作者: Chia-Ying Weng: Assistant professor, Department of Psychology, National Chung-Cheng University, E-mail: psycyw@ccu.edu.tw

Development and Psychometric Properties of

the Self-Evaluation Profile Inventory for

Chinese Chronically Disabled Patients

Chia-Ying Weng, Wen-Chung Wang, Yin-Chang Wu

The purpose of this study is to develop an inventory that measures important domains of self-esteem for Chinese chronically disabled patients. Through in-depth interviews, this study identifies eight major domains that constitute self-esteem of Chinese chronically disabled patients, which can be further grouped into the individual-oriented and social-oriented dimensions. A self-evaluation profile inventory was developed to measure these eight domains. The draft version of the 70-item inventory was administered to 52 chronic patients and 147 normal adults. Through item discrimination, internal consistency, and factor analyses, 39 items were kept. Four factors were identified under the individual-oriented dimension, which were Life Meaning, Health Status, Career Outlook, and Competence. Another four factors were identified under the social-oriented dimension, which were Social Status, Family Support, Ability to Repay, and Family Responsibility. This 39-item final version was administrated to 82 chronically disable patients and 84 normal adults. Results showed that the inventory has good psychometric properties: α is .94 for the whole inventory, and ranges from .73 to .85 for the eight sub-scales. The correlations with the Rosenberg's Self Esteem scale are .82 for the whole inventory, and range from .33 to .73 for the eight sub-scales. Culture differences in the formulation of self-esteem between western and Chinese societies are discussed.

Introduction

Modern medical sciences and technology have led to the prolonging of human life and reducing of fatal illness. To live with a physical disability becomes a salient interpersonal and intrapersonal issue. Chronically disabled patients experience moderate to severe restrictions in their physical functions and a consequent degraded performance in work, family, and other societal situations (Devins, Beanlands, Mandin, & Paul, 1997; Leake, Friend, & Wadhwa, 1999; Malcarne, Hansdottir, Greenbergs, Clements, & Weisman, 1999). The threat to their lives and unpredictability of the causes can make the symptoms so stressful that it devalues the patients' self-evaluation and makes their lives miserable. However, with a good stress coping and a successful life readjustment, self-devaluation could be well controlled. Psychosocial factors are related to the quality of readjustment. Among them, the maintenance of self-esteem is one of the most important factors (Jahanshahi, 1991; Leake, Friend, & Wadhwa, 1999; Skevinton, 1993). The higher the self-esteem, the less the patient feels depressed. Therefore, the intervention for patients with chronically disabled diseases should aim at maintaining or reestablishing self-esteem (Druley & Townsend, 1998; Ireys, Gross, Werthamer-Larsson, & Kolodner, 1994; Li & Moore, 1998; Skevington, 1993).

Dated back to William James (1890), self-esteem has been a central theme in the psychology of cognition, emotion, and motivation, especially in the areas such as motivation for adjustment and readjustment and coping with stressful stimuli (Harter, 1989, 1990; Taylor & Aspinwall, 1993). Self-esteem contains an evaluative aspect where individuals evaluate worthiness of themselves according to ability, ideal standards, and value judgement (Coopersmith, 1967; Harter, 1982; Rosenberg, 1965, 1986) and a feeling aspect where individuals feel they deserve to be loved and respected (Mruk, 1995; Tafarodi & Swann, 1995; Tafarodi & Vu, 1997). Individuals with high self-esteem accept both their good and bad characteristics so that they feel good about themselves as a whole. Maintaining and promoting self-esteem is a pervasive human need and motivation (Allport, 1965; Banaji & Prentice, 1994;

Rogers, 1959). Although consensus on the constructs of self-esteem exists, there are diverse views on its operational definitions and the mechanisms related to the mental entity. These diverse views come from different perspectives on self-esteem: Should self-esteem be treated as a unidimensional global self-evaluation, or as a self-evaluation profile with multiple domains?

1. Global Self-evaluation versus Self-evaluation Profile with Multiple Domains

Morris Rosenberg is the most representative researcher who advocated the unidimensional view. He developed the self-esteem scale to measure global self-evaluation (Rosenberg, 1965). On the other hand, Coopersmith (1967) proposed a multidimensional self-evaluation approach by imposing self-evaluative questions on life domains such as school, family, peers, self, and general social activities. These two perspectives share the common perspective that self-esteem comes from individuals ' self-evaluation, but they differ on the contents. Rosenberg considered self-esteem as a complex synthesis of self-evaluation across situations. Coopersmith, in contrast, considered global self-esteem as a sum of multiple domains of self-esteem where each domain had its own evaluation procedure. Individuals may have high self-esteem in one domain but low self-esteem in another. Each perspective has its own standing point. However, from practical points of view, it is difficult for health professionals to improve or maintain patients' self-esteem when only global self-self-esteem is assessed. To make intervention more efficient, the components that constitute patients' global self-esteem have to be identified, from where specific intervention can be carried out. In other words, if the multiple domains of self-esteem are assessed, the psychopathological mechanism of the chronic decrease in self-esteem can be better clarified so as to make intervention more concrete and efficient.

Rosenberg did not deny the existence of multiple dimensions in self-esteem; rather, he treated them as input to the "black box", global self-esteem. The question is: Can we open the black box and unravel the contents? Many studies showed that summation of multidimensional self-evaluation could predict global self-esteem very well (Harter, 1985, 1990; Hoge & McCarthy, 1984; Marsh, 1986; Weng, 1999).

Many multidimensional self-esteem inventories have been developed mainly for children or adolescents, such as the Self-Description Questionnaire (Marsh, Smith, & Barnes, 1983) and Five-scale Test of Self-esteem for Children (Pope, McHale, & Craighead, 1988). In this study, we focused on the self-esteem of adult patients with chronically disabled diseases. Hence, multidimensional self-esteem inventories for adults were needed to assess those components that caused low self-esteem in the patients. Harter (1982, 1983, 1986, 1990, 1993) conduced a series of studies to develop multidimensional self-esteem inventories for various age levels. Among them, an inventory called the Adult Self-perception Profile (ASP; Messer & Harter, 1986) is the most commonly used. The ASP, developed mainly for normal adults, contains ten subscales: Sociability, Job performance, Nurture, Athletic ability, Adequate provider, Morality, Household Management, Intimate Relationship, Intelligence, and Sense of Humor. The profile, though covering wide enough domains and providing rich diagnostic information about self-evaluation, cannot be directly employed to the present study because: (a) It was developed for normal adults rather than for disabled patients so that it might not be suitable for patients facing catastrophic change in life; and (b) it might not apply to Chinese society due to large cultural differences between western and eastern societies.

2. Normal Population versus Chronically disabled Patients

Chronic illness is a lived experience, involving permanent deviation from the normal and loss or dysfunction (Cameron & Gregor, 1987). When the onset of a disease is sudden and acute, the patients lose their job and household abilities very quickly. Most of them worry about their future and unaccomplished career plans so much as to devalue themselves (Gregory, Way, Hutchinson, Barrett, & Parfrey, 1998). On the bright side, the distress provides them an opportunity to shape life patterns and to inspect their life meanings. Some of them might be able to reborn from the distress, and reconfirm the meanings/values of themselves and human lives (Tayor & Aspinwall, 1993). Because career concerns and life meaning awareness are phenomena somewhat unique to disabled patients, it is questionable whether standard

instruments for normal populations such as the ASP can capture the important features for chronically disabled patients (Price, 1996).

3. Culture Difference

Western cultures are relatively independent-self oriented, whereas eastern cultures are interdependent-self oriented (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). It is highlighted in western cultures to be independent, and to discover and express one's unique attributes. Therefore inventories developed within western cultures, such as the ASP, measure mainly intrapersonal aspects. The ASP contains many individual-oriented domains, such as personal proficiency and achievement, but less family, social, and spiritual domains. Although it does contain intimate relationship and taking care of others (e.g., nurture and adequate provider), the main concern is the "proficiency" to handle these interpersonal relationships, rather than the characteristics of the interpersonal relationships per se. These individual-oriented domains do not involve others' expectation and evaluation, one's importance and status in the affiliation groups, and one's roles in the social networks.

Unlike the "self" in western cultures, the self in eastern cultures includes a sense of interdependency and a sense of one's status as a participant in a large social unit. This view of self is not considered separate and autonomous, rather, it is within the contextual fabric of individual's social relationships, roles, and duties that the interdependent self most securely gains a sense of meaning. A normative imperative of these cultures is to maintain this interdependence among individuals. Experiencing interdependence entails seeing oneself as part of an encompassing social relationship and recognize that one's behavior is determined, contingent on, and to a large extent organized by what the actor perceives to be the thoughts, feeling, and actions of others in the relationship. Individuals who are raised in such cultures come to desire a sense of belonging. Many researchers have supported this argument, for example, Ho, Chen, and Chiu (1991), Hwang (1987) and Solomon (1971) have stressed the prominence and importance of interpersonal relationships within daily social lives in Chinese

societies. Based on the interaction between person and environment, Yang (1995) pointed out that the major difference between western and eastern cultures is individual orientation in the former whereas social orientation in the latter. To understand Chinese mind and behavior, social orientation should be more emphasized than individual orientation. Western cultures emphasize independent self and self-actualization, whereas eastern cultures focus on interdependent-self and group-actualization. Within the social-oriented cultures, personal values that are evaluated through others' judgment are more appropriate than through self-judgment. Besides, the criteria of judgment are usually the role regulation within social relationship.

In brief, the assessments of self-esteem for Chinese should cover different social relational contexts and their respective social roles and duties, in addition to the individual/personal domains. Social and family domains may be important for Chinese self-esteem, which are not included in the instruments developed for Western cultures such as the ASP, which covers only individual-oriented rather than social-oriented domains. Direct translation from western inventories is thus inappropriate for Chinese societies. We need a self-esteem inventory that is developed within the indigenous Chinese cultures.

To resolve the problems raised by cultural differences and the differences between normal and patient populations, and to develop a multidimensional self-esteem inventory for Chinese chronically disabled patients, ten Chinese disabled patients were interviewed in depth to explore the contents and domains of their self-evaluation. Eight major domains that accounted for global self-esteem were identified. A self-evaluation profile containing eight scales was developed accordingly. It was pretested to 52 chronic patients and 147 normal adults. Item analysis was carried out to select and revise the items. The final version was administered to 82 chronic patients and 84 normal adults. In the following, the in-depth interviews are briefly addressed. The psychometric properties of the inventory are reported. The differences in components of self-esteem between western and eastern societies and between normal populations and chronically disabled patients are discussed.

STUDY 1: THE IN-DEPTH INTERVIEW

In the following, we describe how the participants were sampled, how the interview procedures were carried out, how the qualitative data were analyzed, and how the conclusions were drawn.

Method

1. Participants

Ten Chinese disabled patients (6 men and 4 women) with spinal cord injury or end-stage renal diseases or systemic lupus Erythematosus were interviewed. They were 20 to 55 years old (M = 36.37, SD = 8.74), mentally competent, and not experiencing an acute illness episode or significant decline in health status.

2. Procedure

The participants were interviewed three times, each for about one to two hours. They were asked to talk freely about themselves in their native languages, Mandarin or Taiwanese. Various counseling skills, such as empathy, reflection, restatement, or clarification, were applied to locate the themes of self-evaluation.

3. Data Analysis

Taped interviews were transcribed verbatim by the research assistants and were double checked by the interviewer. Two raters, the first author of the present paper and a senior clinical psychologist, independently coded and interpreted the transcripts. First of all, the two raters independently analyzed the transcripts of the three interviewees. The data were translated into concepts. New concepts were obtained through further investigation and contrast analysis of the meaningful units in the transcripts. In the mean time, similar concepts were integrated to

develop frameworks. These frameworks developed by the two independent raters were than compared. The differences were discussed until consensus was reached so that the common framework was formed. Subsequent data analysis was carried out with the framework. The agreement in the categorization between raters was .87. The difference in the categorization was discussed to further reach consensus. Finally, eight domains, which were conceptualized into two clusters: individual-oriented and social-oriented clusters, were reached. These eight domains as well as their concentrations were reviewed by outside content-experts, including two senior clinical psychologists, a physician, and a social psychology professor. The first three experts had experiences in the treatment of chronically disabled patients in primary care for more than eight years. The experts were asked, based on their clinical expertise and professional knowledge, to judge whether these eight domains corresponded to the phenomena that they had observed in clinical practices, that is, whether these eight domains covered important aspects of self-esteem of Chinese chronically disabled patients.

Results

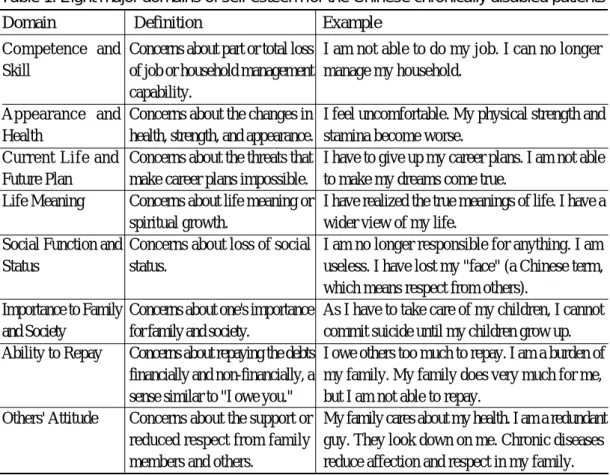

Through content analysis, the primitive self-evaluation concepts of the Chinese chronically disabled patients were classified as eight domains, which were further classified conceptually into two major dimensions. The individual-oriented dimension which involved personal characteristics rather than others' judgments, contained four domains of self-evaluation, such as Competence and Skill, Appearance and Health, Current Life and Future Plan, and Life Meaning. In contrast, the social-oriented dimension contained another four self-evaluation domains that are related to personal characteristics within social contexts, such as Social Function and Status, Importance to Family and Society, Ability to Repay, and Others' Attitude. The following summarize the definitions of the eight domains and some narrative data. The definitions and several examples of the eight domains can be found in Table 1. Detailed protocols are not shown here because of space constraint, but available on request.

1. Individual-Oriented Dimension

Competence and Skill. Due to damages to physical functions, the patients lost their capability to work or manage housework. For example, some patients said "I am not able to help planting tobacco so that I am a useless person.", or "So far, I still can do my job well".

Appearance and Health. The patients concerned very much about their changes of appearances, body shapes and health, because of the diseases and physical disability. For instance, "I feel very uncomfortable.", "I feel very upset because anyone can tell that I am a patient.", or "My physical strength is still good."

Current Life and Future Plan. The patients' stable lives were threatened by the disease. Competence and

Skill

Appearance and Health

Current Life and Future Plan Life Meaning Social Function and Status

Importance to Family and Society

Ability to Repay

Others' Attitude

Table 1. Eight major domains of self-esteem for the Chinese chronically disabled patients

Domain Definition Example Concerns about part or total loss

of job or household management capability.

Concerns about the changes in health, strength, and appearance. Concerns about the threats that make career plans impossible. Concerns about life meaning or spiritual growth.

Concerns about loss of social status.

Concerns about one's importance for family and society.

Concerns about repaying the debts financially and non-financially, a sense similar to "I owe you." Concerns about the support or reduced respect from family members and others.

I am not able to do my job. I can no longer manage my household.

I feel uncomfortable. My physical strength and stamina become worse.

I have to give up my career plans. I am not able to make my dreams come true.

I have realized the true meanings of life. I have a wider view of my life.

I am no longer responsible for anything. I am useless. I have lost my "face" (a Chinese term, which means respect from others).

As I have to take care of my children, I cannot commit suicide until my children grow up. I owe others too much to repay. I am a burden of my family. My family does very much for me, but I am not able to repay.

My family cares about my health. I am a redundant guy. They look down on me. Chronic diseases reduce affection and respect in my family.

Their daily activities were restricted. The original career plans could no longer be maintained or continued. Goals could no longer be achieved would then affect patients' self-evaluations were affected by the unattainable goals. For instance, "My daily activities are restricted.", or "I am forced to give up many things that I planned to do."

Life Meaning. The patients reconsidered live meanings while suffering in the pain. Some patients might consider lives as meaningless, whereas others might achieve spiritual or mental growth, which included deeper understanding and wider wisdom. For instance, "I would rather die than suffer this pain.", or "My life is more valuable than ever."

2. Social-Oriented Dimension

Social Function and Status. The patients' social functions or social statuses were reduced or lost, and would therefore affect their self-evaluations. For example, "I am no longer the president of the company; I become a useless person.", or "I am still assigned with very important missions in the company."

Importance to Family and Society. In the interpersonal network, responsibility to family and society is a very important domain in the self-evaluation for the patients. For instance, "I was a super sales before, but now I has been transferred to the interior department and become a nobody.", or "I am very important to my kids. They need me so much. I can't die by now. I have to raise my kids until they are grown-ups."

Ability to Repay. Being a patient, he/she needed more assistance and care from others and had less ability to repay. This unbalanced situation threatened subjective and objective acceptance by groups and affected self-esteem. For instance, "I am useless but becoming my family's burden.", "I owe a lot of people and am unable to repay.", or "I am a rice-worm of the society."

Others' Attitude. The ways how the patients were treated, accepted and recognized would affect their self-evaluations. For instance, "My family ignore me or mock me.", "Nobody respects me.", or "I am still respected by others.'

The individual-oriented domains for self-evaluation appear to be rather universal and cross-cultural. Disabled patients, in either western or eastern societies, are very concerned with the meaning of their distress and their loss of competence, health, and future. On the contrary, the social-oriented dimension is the distinguishing feature of eastern societies but less emphasized in western societies.

STUDY 2: Development of the Self-Evaluation Profile Inventory

Based on the findings of the in-depth interviews about the eight domains and clinical experiences, the first author of this study developed the Self-Evaluation Profile Inventory (SPI), which contained seventy 6-point Likert-type items. The SPI was reviewed and revised by the same four content experts as in the domains review. It was pre-tested, item analyzed, and factor analyzed. For concurrent validity, we used Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (RSE, Rosenberg, 1965) as the criterion. It has been shown that the sum score over the multidimensional domains of the self-evaluation can predict the overall self-esteem very well (Harter, 1985, 1990; Hoge & McCarthy, 1984; Marsh, 1986; Weng, 1999). After reviewing relevant literature, Crocker and Wolfe (2001) and Heine, Lehman, Markus and Kitayama (1999) pointed out that the measurements of overall self-esteem are not affected by culture differences.

Method

1. Participants

At the pre-test stage, the inventory was administered individually to 52 ordinary chronic patients form the Family Medicine Department (the patient group) by the interviewers. The contrast group consisted of 147 normal adults who participated in physical examination in the hospitals and college students. Group administration was used to collect the data. In the patient group, genders were approximately equally distributed (27 males and 25 females), whereas there were more females in the contrast group (61 males and 86 females). The patients aged

from 40 to 55 dominated the age distribution in the patient group. For the normal adults in the contrast group, those who aged from 25 to 40 dominated the age distribution. Most college students were 18 to 22 years old.

The formal patient sample consisted of 82 chronically disabled patients 39 men and 43 women; average ages =43.3, SD=11.6, range = 17~79), which were collected from the several hemodialysis centers by the interviewers. The formal contrast group consisted of 84 normal adults (42 men and 42 women; average ages = 42.9, SD=11.8, range = 21~71), which were collected from community colleges by group administration.

2. Item Analysis

Item analysis was carried out for the pretest data. The pretest sample (consisting ordinary chronic patients and normal adults) was split into two extreme groups, upper 25% and lower 25%, according to the raw scores. Item discrimination analysis was conducted. If these two groups did not perform differently on an item, it was declared as not showing discrimination power and thus would be excluded from the inventory. However, some poor-discriminating items were kept because they were suspected to show sufficient power in discriminating chronically disabled patients from normal adults. The formal sample of 82 chronically disabled patients was also split into two extreme groups and item discrimination analysis was carried out. After comprehensive item analysis, 13 items in total were excluded from the inventory.

Results

1. Factor Analysis

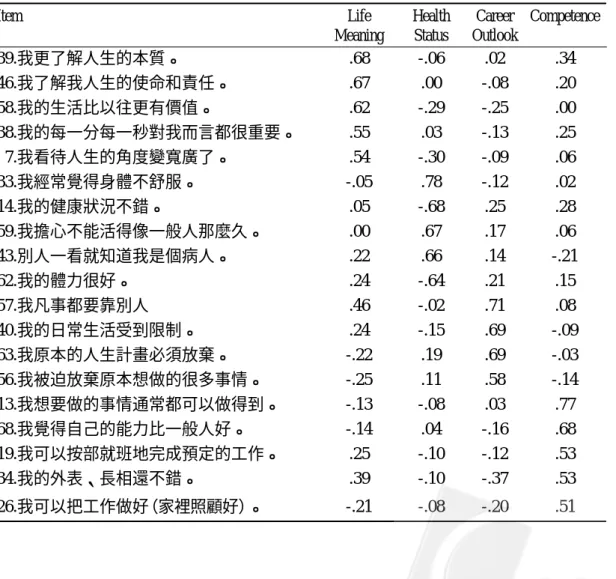

Two exploratory factor analyses on the data of the 82 chronically disabled patients were conducted to check the construct validity of the inventory. The items in the individual-oriented dimensions and those in the social-oriented dimension were factor analyzed separately with principle axis factoring extraction. The scree plot as well as the eigenvalue over 1 showed that four factors were appropriate in both dimensions. Oblimin rotation was used on the four resulting

factors. Items with factor loading less than 0.5 or with high loadings on more than one factor were excluded. Finally, 39 items, as shown in Appendix A, were kept to form the final version. After a preliminary item analysis, 39 out of 70 items were kept to form the final version. Tables 2 and 3 list the factor structures of the two dimensions. In the individual-oriented dimension, four factors were found and named as (a) Life Meaning, (b) Health Status, (c) Career Outlook, and (d) Competence. The variance explained was 49.9%. Basically, these four factors were consistent with those found from the clinical interview: Life Meaning, Appearance and Health, Current Life and Future Plan, and Competence and Skill.

Table 2. Factor structure of the individual-oriented dimension

Item Life Health Career Competence Meaning Status Outlook

39.我更了解人生的本質。 .68 -.06 .02 .34 46.我了解我人生的使命和責任。 .67 .00 -.08 .20 58.我的生活比以往更有價值。 .62 -.29 -.25 .00 38.我的每一分每一秒對我而言都很重要。 .55 .03 -.13 .25 7.我看待人生的角度變寬廣了。 .54 -.30 -.09 .06 33.我經常覺得身體不舒服。 -.05 .78 -.12 .02 14.我的健康狀況不錯。 .05 -.68 .25 .28 59.我擔心不能活得像一般人那麼久。 .00 .67 .17 .06 43.別人一看就知道我是個病人。 .22 .66 .14 -.21 62.我的體力很好。 .24 -.64 .21 .15 57.我凡事都要靠別人 .46 -.02 .71 .08 40.我的日常生活受到限制。 .24 -.15 .69 -.09 63.我原本的人生計畫必須放棄。 -.22 .19 .69 -.03 56.我被迫放棄原本想做的很多事情。 -.25 .11 .58 -.14 13.我想要做的事情通常都可以做得到。 -.13 -.08 .03 .77 68.我覺得自己的能力比一般人好。 -.14 .04 -.16 .68 19.我可以按部就班地完成預定的工作。 .25 -.10 -.12 .53 34.我的外表、長相還不錯。 .39 -.10 -.37 .53 26.我可以把工作做好(家裡照顧好)。 -.21 -.08 -.20 .51

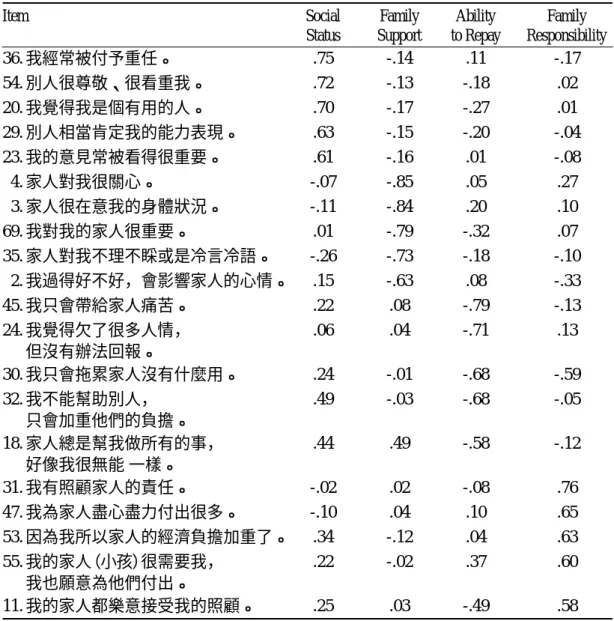

Table 3. Factor structure of the social-oriented dimension

Item Social Family Ability Family Status Support to Repay Responsibility

36.我經常被付予重任。 .75 -.14 .11 -.17 54.別人很尊敬、很看重我。 .72 -.13 -.18 .02 20.我覺得我是個有用的人。 .70 -.17 -.27 .01 29.別人相當肯定我的能力表現。 .63 -.15 -.20 -.04 23.我的意見常被看得很重要。 .61 -.16 .01 -.08 4.家人對我很關心。 -.07 -.85 .05 .27 3.家人很在意我的身體狀況。 -.11 -.84 .20 .10 69.我對我的家人很重要。 .01 -.79 -.32 .07 35.家人對我不理不睬或是冷言冷語。 -.26 -.73 -.18 -.10 2.我過得好不好,會影響家人的心情。 .15 -.63 .08 -.33 45.我只會帶給家人痛苦。 .22 .08 -.79 -.13 24.我覺得欠了很多人情, .06 .04 -.71 .13 但沒有辦法回報。 30.我只會拖累家人沒有什麼用。 .24 -.01 -.68 -.59 32.我不能幫助別人, .49 -.03 -.68 -.05 只會加重他們的負擔。 18.家人總是幫我做所有的事, .44 .49 -.58 -.12 好像我很無能 一樣。 31.我有照顧家人的責任。 -.02 .02 -.08 .76 47.我為家人盡心盡力付出很多。 -.10 .04 .10 .65 53.因為我所以家人的經濟負擔加重了。 .34 -.12 .04 .63 55.我的家人(小孩)很需要我, .22 -.02 .37 .60 我也願意為他們付出。 11.我的家人都樂意接受我的照顧。 .25 .03 -.49 .58

In the social-oriented dimension, four factors were also found and named as (a) Social Status, (b) Family Support, (c) Ability to Repay, and (d) Family Responsibility. The variance explained was 52.1%. The first and third factors corresponded to the original domains in the clinical interview. However, Family Support and Family Responsibility were somewhat different from those fond in the interview: Others' Attitude and Importance to Family and Society. As

family is closer to individuals than society, family is more essential to the construction of self-esteem than society. In brief, the factor analyses confirmed the structures of the eight domains in the self-evaluations for Chinese chronically disabled patients.

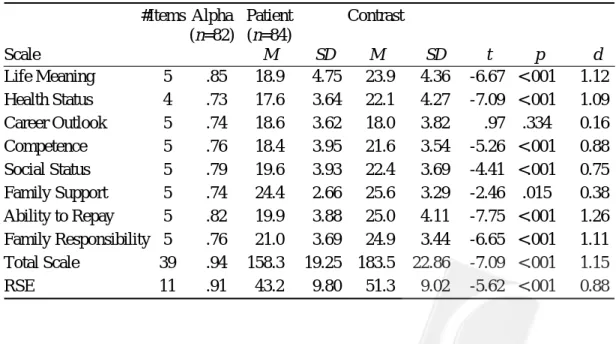

2. Reliability and Validity

Table 4 shows the numbers of items and the alpha coefficients for the eight scales, the total scale (containing all the 39 items), and the RSE. The alpha coefficients were between .73 and .85 for the eight scales, .94 for the total scale, and .91 for the RSE. In general, all these scales had satisfactory internal consistency. Table 4 also lists the means and the standard deviations for the patient and contrast groups on these scales. The t-tests show that the patient group expressed statistically significantly lower self-esteem on all the scales at the .05 level, except on Career Outlook. According to Cohen's standardized mean difference d (Cohen, 1969), the effect sizes for the two groups on Career Outlook and Family Support were 0.16 and 0.38, respectively, which were rather mild. Those for the other six scales ranged from 0.75 and 1.26, indicating large effects.

Table 4. Reliability, mean, standard deviation, t-test, and Cohen's d for the two groups on the scales

#Items Alpha Patient Contrast (n=82) (n=84) Scale M SD M SD t p d Life Meaning 5 .85 18.9 4.75 23.9 4.36 -6.67 <.001 1.12 Health Status 4 .73 17.6 3.64 22.1 4.27 -7.09 <.001 1.09 Career Outlook 5 .74 18.6 3.62 18.0 3.82 .97 .334 0.16 Competence 5 .76 18.4 3.95 21.6 3.54 -5.26 <.001 0.88 Social Status 5 .79 19.6 3.93 22.4 3.69 -4.41 <.001 0.75 Family Support 5 .74 24.4 2.66 25.6 3.29 -2.46 .015 0.38 Ability to Repay 5 .82 19.9 3.88 25.0 4.11 -7.75 <.001 1.26 Family Responsibility 5 .76 21.0 3.69 24.9 3.44 -6.65 <.001 1.11 Total Scale 39 .94 158.3 19.25 183.5 22.86 -7.09 <.001 1.15 RSE 11 .91 43.2 9.80 51.3 9.02 -5.62 <.001 0.88

It should be noted that the major purpose of the inventory was to identify those components that constitute self-esteem of chronically disabled patients, rather than discriminating patients from normal persons. The t-tests reveals group differences between patients and normal adults. No solid rationales exist to predict which group will be higher on which subscale. The patient and contrast groups did not differ on Career Outlook. The exact reason of this result was unknown but we provide a possible explanation here. The economic status in Taiwan at the time when the participants were surveyed began to depress and the unemployment rate began to rise. The unemployment rate for those who entered in community colleges from which the normal adult sample was drawn was especially severe. This might explain why the normal adults did not score higher than the patients. On the other hand, the patients scored slightly lower on Family Support than the normal adults. This might be because the patient gradually adapted to the diseases or "There are no filial sons standing in front of beds for a long disease(久病床前無孝

子)" so that the intense Family Support gradually vanished. These explanations, of course, need

further investigations.

Table 5 reports the correlations among the eight scales, the total scale, and the RSE. The correlations among the eight scales ranged from .12 to .77, indicating that the eight scales were measuring distinct but positively correlated attributes. All of the eight scales were moderately correlated to the total scale and the RSE. This was expected because the eight domains not only constitute parts of overall self-esteem but also tap some unique aspects of self-esteem.

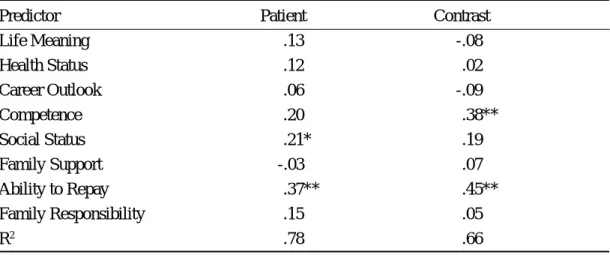

Table 6 lists the regression coefficients and the coefficients of determination (R2) where

the RSE was regressed on the eight scales for both groups, respectively. The eight domains accounted for 78% of the variance in the RSE for the patient group, somewhat larger than that for the contrast group, 66%. The large proportion revealed that the eight domains captured very well the components of global self-esteem for the patients. Among the eight domains, Ability to Repay (concerning the repaying the financial and non-financial debts) was the most important predictor for both groups. Ability to Repay is a key concept of interdependency self of Chinese culture. The second important predictors were Social Status (concerning the loss of

Table 5. Correlations between the eight scales, the total scale, and the RSE S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 Total RSE S1 .51* .12 .51* .55* .49* .43* .55* .74* .48* S2 .33* .58* .44* .22* .67* .50* .78* .62* S3 .32* .23* .23* .45* .31* .50* .35* S4 .77* .33* .54* .54* .80* .71* S5 .42* .50* .56* .77* .67* S6 .31* .50* .57* .33* S7 .63* .80* .73* S8 .79* .60* Total .82*

Note. S1: Life Meaning; S2: Health Status; S3: Career Outlook; S4: Competence; S5: Social Status; S6: Family Support; S7: Ability to Repay; S8: Family responsibility; *p <.01.

Table 6. Standardized regression coefficients for the patient and contrast groups

Predictor Patient Contrast

Life Meaning .13 -.08 Health Status .12 .02 Career Outlook .06 -.09 Competence .20 .38** Social Status .21* .19 Family Support -.03 .07 Ability to Repay .37** .45** Family Responsibility .15 .05 R2 .78 .66 *p < .05; **p < .01.

social status) for the patient group and Competence for the contrast group, respectively. For the normal populations, Competence was very important to self-esteem. Because those chronically disabled patients who had already lost job/household competence became sensitive to others' evaluation (Leary, Tambor, Terdal, & Downs, 1995), Social Status was more influential than Competence upon their self-esteem.

As previously stated, the major purpose of this study was to develop an inventory that measures important domains of self-esteem of chronically disabled patients, rather than a simple overall domain, in order to gain a deeper understanding of patients' self-evaluation and to make clinical treatments more efficient. Each of the eight domains taped an important aspect of patients' self-esteem and was deemed to be important for clinical applications, as concluded in Study 1. Although only two domains were statistically significant in predicting the RSE, it did not mean that the other six domains were useless in predicting the RSE or in clinical applications. It should be explained as: Given these two significant domains, no additional information in predicting the RSE was obtained by adding the other six domains. The other six domains were not statistically significant, not because they were not correlated with the RSE, but because they were correlated with the two domains (see Table 5). Multiple regression analysis was used mainly to compare the differences in the magnitudes of R2 and dominant

domains between the patient and contrast groups.

Rothbaum, Weisz, and Snyder (1982) proposed a primary/secondary control model to depict coping processes. In the primary control process, individuals try to adjust environments to fit their needs or expectations. If the environments could not be changed satisfactorily, they have to adjust themselves to the environments, which are referred to as the secondary control process. In addition to the primary and secondary control processes, Weise, McCabe, and Dennig (1994) proposed a relinquished control process to depict giving up or no attempt to control. Adopting the primary or secondary control process, chronically disabled patients could adjust their physical and psychological conditions to maintain or improve self-esteem. If the relinquished control process functions, self-esteem may get worse.

The Coping Style Inventory (revised by Chang, Huang, & Lin, 1988), containing 22 items for the primary control, 15 items for the secondary control, and 14 items for the relinquished control, was administered to the 82 chronically disabled patients of the present study. The correlations between the total score of the self-evaluation profile inventory and the primary control, the secondary control, and the relinquished control, were .29, .25, and -.37, respectively. All of them were significant at the .05 level. As expected, the primary and secondary controls were positively correlated while the relinquished control was negatively correlated to self-esteem.

Conclusion and Discussion

Eight major domains that contribute to self-esteem for Chinese chronically disabled patients are identified through in-depth interviews. These eight domains, clustering into individual-oriented and social-individual-oriented dimensions. An implication of the identification of the eight domains and the two dimensions is that psychological rehabilitation for each domain or dimension becomes more concrete and direct. Another implication is its theoretical values revealing the differences in self-esteem between western and eastern societies and between normal populations and chronically disabled patients. The social-oriented domains are less emphasized in western societies. Ability to Repay is the most important component for both Chinese chronically disabled patients and normal adults. On the other hand, Social Status contributes to self-esteem more for patients than for normal adults.

The RSE, although not affected by culture differences (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001; Heine et al., 1999), measures only overall self-esteem and thus is lack of detailed clinical differentiation. It is unable to provide information of the major domains that might reduce the self-esteem of chronically disabled patients. The present study developed a multidimensional self-evaluation inventory which measures and provides profile information about the patients' self-evaluation. Through reviewing the profile information about the eight domains, clinicians are able to

develop appropriate treatments and thus to raise or maintain patients' self-esteem more efficiently.

Among western multidimensional self-evaluation inventories for Adult, the Adult Self-perception Profile (Messer & Harter, 1986) is the most representative. There are several differences between the eight domains found in this study and those in the Adult Self-perception Profile. The ASP contains many individual-oriented domains, such as personal proficiency and achievement, but less family, social, and spiritual domains. In this study, different components of self-esteem for those indigenous chronically disabled patients are found. Not only intrapersonal proficiency, but also social relationships and spiritual aspects are included. Chinese value themselves based on both their own proficiency and contributions to significant others, and interpersonal dignity given by others. This is evident from the results that Ability to Repay and Social status rather than the individual-oriented domains are the most important two components of self-esteem. In contrast, for western societies that emphasize independence, Competence (concerning the loss of job or household management capability) might be more important than Ability to Repay in the formulation of self-esteem.

Family Support and Family Responsibility are two other important domains within the social-oriented dimension. For example, several participant patients mentioned that when they suddenly became physically dysfunctional, their family members soon came together to take care of them and to share the nursing and housing works. Family's concerns, supports, and positive regards made them feel worthy and dignified, which was very useful in recovering their injured self-esteem. Family responsibility, especially in taking care of children, is another important factor in sustaining patients' self-value. To accomplish this responsibility, patients try hard to maintain their health status and job or household capability. It should be noted that family members should not protect patients too much so as to deprive their self-function. For instance, several patients stated that their family members worried and protected them too much, and prevented them from doing routine activities, which made them feel devalued.

by Taylor and Aspinwall (1993), patients in western cultures also have this spiritual domain in their self-concepts. The formulation of Chinese patient's life meaning making is as follows. When patients are informed about their diseases, the first reaction they usually have is "why me?" After a period of struggling, they start to think over their life histories and come to realize the true meanings of life. This spiritual appreciation helps them reconstruct their self-esteem. Future studies may be conducted to investigate psychometric properties of the present inventory, or to develop other self-esteem inventories for Chinese normal populations and patient populations.

The Self-evaluation Profile Inventory is designed to measure the eight domains, one scale per domain. Although the lengths of the scales are small, the reliabilities are satisfactory. Although the inventory is made primarily for chronically disabled patients, it might apply to patients with other acute diseases. More empirical reliability and validity evidences about this inventory for other populations need to be collected. To make the assessment of self-esteem more effective for various groups, item banks for multiple domains are needed. From the banks, different test booklets can be assembled according to subjects' age, socio-economic backgrounds, types of diseases, or severity of disability. To develop such item banks, not only domains of self-esteem across groups should be identified but also psychometric prosperities be further investigated. We devote ourselves to these research works within Chinese societies.

References

Allport, G. W. (1965). Pattern and Growth in Personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Banaji, M. R., & Prentice, D. A. (1994). The self in social contexts. Annual Review of Psychology, 45, 297-332.

Cameron, K., & Gregor, F. (1987). Chronic illness and compliance. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 12, 671-676.

Chang, C., Huang, M.-H., & Lin, H.-C. (1988). Preliminary study on stressor and coping of mastectomy patients. Journal of National Public Health Association, 8, 109-124. Cohen, J. (1969). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (1st Ed.). Hillsdale, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco: Freeman.

Crocker, J., & Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review, 108(3), 593-623.

Devins, G. M., Beanlands, H., Mandin, H., & Paul, L. C. (1997). Psychosocial impact of illness intrusiveness moderated by self-concept and age in end-stage renal disease. Health Psychology, 16, 529-538.

Druley, J. A., & Townsend, A. L. (1998). Self-esteem as a mediator between spousal support and depressive symptoms: A comparison of healthy individuals and individuals coping with arthritis. Health Psychology, 17, 255-261.

Gregory, D. M., Way, C. Y., Hutchinson, T. A., Barrett, B. J., & Parfrey, P. S. (1998). Patients' perceptions of their experiences with ESRD and hemodialysis treatment. Qualitative Health Research, 8, 764-784.

Harter, S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87-97. Harter, S. (1983). Developmental perspectives on the self-system. In E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development (Vol. 4, pp. 275-386). New York: John Wiley.

Harter, S. (1985). The Self-Perception Profile for Children (Manual). Denver, Co: University of Denver.

Harter, S. (1986). Processes underlying the construction, maintenance, and enhancement of the self-concept in children. In J. Suls & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 3, pp. 137-181). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Harter, S. (1989). Causes, correlates and the functional role of global self- worth: A life-span perspective. In J. Kolligan & R. Sternberg (Eds.), Perceptions of competence and

incompetence across the life span (pp. 43- 70). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Harter, S. (1990). Adolescent self and identity development. In S. S. Feldman & Elliot G.R. (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 352-387). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harter, S. (1993). Causes and consequences of low self-esteem in children and adolescents. In R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Self-esteem: The puzzle of low self-regard (pp. 87-116). New York: Plenum.

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard. Psychological Review, 106, 766-794.

Ho, D.Y. F., Chen, S. J., & Chiu, C. Y. (1991). Relational orientation: In search of a methodology for Chinese social psychology. In K. S. Yang & K. K. Hwang (Eds.), Chinese psychology and behavior (pp.49-66). Taipei, Taiwan: Guiguan Book. (In Chinese)

Hoge, D. R., & McCarthy, J. D. (1984). Influence of Individual and group identity salience in the global self-esteem of youth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 403-414. Hwang, K. K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of

Sociology, 92, 944-974.

Ireys, H. T. , Gross, S. S., Werthamer-Larsson, L. A., & Kolodner, K. B. (1994). Self-esteem of young adults with chronic health conditions: Appraising the effects of perceived impact. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 15, 409-415.

Jahanshani, M. (1991). Psychosocial factors and depression in torticollis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 35, 493-507.

James, W. (1890). Principles of psychology. New York: Holt.

Leake, R., Friend, R., & Wadhwa, N. (1999). Improving adjustment to chronic illness through strategic self-presentation: an experimental study on a renal dialysis unit. Health Psychology, 18, 54-62.

Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 68, 518-530.

Li, L., & Moore, D. (1998). Acceptance of disability and its correlates. Journal of Social Psychology, 138, 13-25.

Malcarne, V. L., Hansdottir, I., Greenbergs, H. L., Clements, P. J., & Weisman, M. H. (1999). Appearance self-esteem in systemic sclerosis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23, 197-208. Markus, H., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion,

and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253.

Marsh, H. W. (1986). Global self-esteem: Its relation to specific facets of self-concept and their importance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1224-1236.

Marsh, H. W., Smith, I. D., & Barnes, J. (1983) Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Self-Description Questionnaire: Student-teacher agreement on multidimensional ratings of student self-concept. American Education Research Journal, 20, 333-357.

Messer, B., & Harter, S. (1986). The Adult Self-perception Profile (Manual). Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Mruk, C. (1995). Self-esteem: Research, theory, and practice. New York: Springer.

Pope, A. W., McHale, S. M., & Craighead, W. E. (1988). Self-esteem enhancement with children and adolescents. New York: Pergamon press.

Price, B. (1996). Illness careers: The chronic illness experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24, 275-279.

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships, as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Eds.), Psychology: A study of science (Vol. 3, pp. 184-256). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1986). Conceiving the self. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J. R., & Snyder, S. S. (1982). Changing the world and changing the self: A two-process model of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 5-37.

Skevington, S. M. (1993). Depression and causal attributions in the early stages of a chronic painful disease: A longitudinal study of early synovitis. Psychology and Health, 8, 51-64. Solomon, R. H. (1971). Mao's Revolution and the Chinese political culture. Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press.

Tafarodi, R. W., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (1995). Self-liking and self-competence as dimensions of global self-esteem: Initial validation of a measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65, 322-342. Tafarodi, R. W., & Vu, C. (1997). Two-dimensional self-esteem and reactions to success and

failure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 626-635.

Taylor, S. E., & Aspinwall, L. G. (1993). Coping with chronic illness. In L. Goldberger & S. Berznitz (Eds.), Handbook of Stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects (2nd Ed., pp. 511-531). New York: Free Press.

Weisz, J. R., McCabe, M. A., & Dennig, M. D. (1994). Primary and secondary control among children undergoing medical procedures: Adjustment as a function of coping style. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 324-332.

Weng, C.-Y. (1999). The change of evaluative self-concept in chronically disabled patients at early sick stage. Research in Applied Psychology, 3, 129-161.

Yang, K. S. (1995). Chinese social orientation: An integrative analysis. In E. S. Tseng, T. Y. Lin, & Y. K. Yeh (Eds.), Chinese societies and mental health (pp.19-39). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

1 我的體力很好。 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 我過得好不好會影響家人的心情。 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 家人很在意我的身體狀況。 1 2 3 4 5 6 4 家人對我很關心。 1 2 3 4 5 6 5 我看待人生的角度變寬闊了。 1 2 3 4 5 6 6 我更了解人生的本質。 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 我的每一分每一秒時間對我都很重要。 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 我經常覺得身體不舒服。 1 2 3 4 5 6 9 我想要做的事情通常都可以做得到。 1 2 3 4 5 6 10 我的健康狀況不錯。 1 2 3 4 5 6 11 家人總是幫我做所有的事,好像我很無能一樣。 1 2 3 4 5 6 12 我覺得我是個有用的人。 1 2 3 4 5 6 13 我的意見常被看得很重要。 1 2 3 4 5 6 14 我可以把工作做好。 1 2 3 4 5 6 15 別人相當肯定我的能力表現。 1 2 3 4 5 6 16 我只會拖累家人,沒有什麼用。 1 2 3 4 5 6 17 我不能幫助別人,只會加重他們的負擔。 1 2 3 4 5 6 18 家人對我不理不睬或是冷言冷語。 1 2 3 4 5 6 19 我經常被付予重任。 1 2 3 4 5 6 20 我覺得欠了很多人情,但沒有辦法回報。 1 2 3 4 5 6 21 別人一看就知道我是個病人。 1 2 3 4 5 6 22 我只會帶給家人痛苦。 1 2 3 4 5 6 23 我瞭解我人生的任務和責任。 1 2 3 4 5 6 24 我為家人盡心盡力付出很多。 1 2 3 4 5 6 25 我的家人都樂意接受我的照顧。 1 2 3 4 5 6 26 我有照顧家人的責任。 1 2 3 4 5 6 27 我的日常活動受到限制。 1 2 3 4 5 6 28 我可以按部就班地完成預定的計劃。 1 2 3 4 5 6 29 因為我,所以家人的經濟負擔加重了。 1 2 3 4 5 6 30 別人很尊敬、很看重我。 1 2 3 4 5 6 31 我的家人(或小孩)很需要我,我也願意為他們付出。 1 2 3 4 5 6 32 我被迫放棄原本想做的很多事情。 1 2 3 4 5 6 33 我凡事都要靠別人。 1 2 3 4 5 6 34 我的生活比以往更有價值。 1 2 3 4 5 6 35 我的外表、長相還不錯。 1 2 3 4 5 6 36 我原本的人生計劃必須放棄。 1 2 3 4 5 6 37 我怕別人看到我的樣子,這讓我很不自在。 1 2 3 4 5 6 38 我覺得自己的能力比一般人好。 1 2 3 4 5 6 39 我對我的家人很重要。 1 2 3 4 5 6

Note. Life Meaning: 5, 6, 7, 23, 34; Health Status: 1, 8, 10, 21; Career Outlook: 27, 32, 33, 36, 37; Competence: 9, 14, 28, 35, 38; Social Status: 12, 13, 15,19, 30; Family Support: 2, 3, 4, 18,

Appendix A. The Self-Evaluation Profile Inventory

Item Content 非 不 稍 稍 符 非

常 符 微 微 合 常

不 合 不 符 符

符 符 合 合