Two thirds of patients with acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) develop diarrhea at some time during the course of their illness.1-3

Diarrhea itself is a cause of major morbidity and may contribute to the death of these patients. Infectious etiologies account for 30% to 80% of the diarrhea in patients with AIDS and the chance of finding an infectious agent depends on patient char-acteristics and extent of evaluation.4-9As with other

clinical syndromes in AIDS, the approach to the patient with diarrhea is oriented toward diagnosing treatable causes and avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures. In clinical practice a stepwise diagnostic approach is often recommended in which less inva-sive investigations are used first (stool analysis), and more invasive tests (endoscopy with biopsy) are

reserved for patients in whom a pathogen is not identified by stool examinations or those who fail to respond to treatment of symptoms.10-15However, it

is not clear whether endoscopy with other associat-ed studies will influence the survival of these patients. Therefore, this study was designed to determine how often an identifiable pathogen can be recognized by endoscopy in AIDS patients in whom stool analysis has been negative, and the impact that specific therapy might have on the outcome for these patients.11,15

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A 9-bed AIDS unit was established on June 24, 1994, at our university hospital. It has since become the largest referral center for the management of complications asso-ciated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infec-tion in Taiwan. As of December 31, 1997, there were 390 admissions for 210 HIV-infected patients, the great major-ity being patients with advanced HIV infection, for the management of HIV-related complications. Before mid-April 1997, patients were treated with two non-nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (zidovudine, dideoxycyti-dine, or didanosine). Protease inhibitors (indinavir, riton-avir, hard-gel saquinavir) were not available until mid-April 1997. Since then, protease inhibitors were freely provided to all HIV-infected patients at any stage of infec-tion. For those patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts less than 200/mm3or previous episodes of pneumocystosis,

patients with diarrhea and negative stool studies

Shu-Chen Wei, MD, Chien-Ching Hung, MD, Mao-Yuan Chen, MD, Cheng-Yi Wang, MD, PhD, Che-Yen Chuang, MD, PhD, Jau-Min Wong, MD, PhD

Taipei, Taiwan

Background: Diarrhea is a frequent gastrointestinal symptom in patients with acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and is a major source of morbidity and mortality. A stepwise diag-nostic approach is often recommended to search for treatable causes. However, whether the step-wise diagnostic approach is adequate for planning treatment and whether specific treatment for infectious etiologies will affect the survival of patients with AIDS remain unknown.

Methods: From March 1996 to September 1997, endoscopy was performed in AIDS patients with diarrhea, the etiology of which was not identified by noninvasive methods. Specific treatment was given according to the identified etiologies and symptomatic treatment was given for those with-out definite diagnosis. The clinical symptoms, signs, and duration of follow-up were recorded and survival patterns were analyzed.

Results: Etiologic diagnoses were made in 26 of 40 patients (65%) who underwent endoscopic studies. Amebic colitis and cytomegalovirus colitis were the 2 leading causes of prolonged diar-rhea in patients with AIDS. Thirty-five patients (87.5%) recovered after treatment. The difference in survival time after diarrhea between patients whose symptoms resolved after treatment and those who continued to have diarrhea was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Conclusions: Endoscopic studies were helpful for the diagnosis of prolonged diarrhea in AIDS patients who had negative stool studies and did not respond to 2 weeks of empiric treatment. Specific treatment according to the results of endoscopy may improve survival in these patients. (Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:427-32.)

Received June 1, 1999. For revision October 7, 1999. Accepted October 26, 1999.

From the Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

Supported by the grant from the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Reprint requests: Jau-Min Wong, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, 7 Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan, R.O.C. Copyright © 2000 by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 0016-5107/2000/$12.00 + 0 37/1/104048

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was given for primary or secondary prophylaxis. Rifabutin and newer macrolides were not routinely given for primary prophylaxis against Mycobacterium avium complex disease, and ganciclovir was not given for cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease. Inclusion criteria

From March 1, 1996, to September 30, 1997, AIDS patients who had diarrhea had stool studies repeated 3 times at first. The studies included staining (wet mount, gram stain and modified acid fast stain) and cultures (cul-tures for Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia species and Clostridium difficile). One stool spec-imen was obtained routinely from each patient for deter-mination of C difficile toxin A by immunoassay. Diarrhea was defined as the presence of at least 3 liquid bowel movements per day. The patients whose stool examina-tions were nondiagnostic and those who did not respond to 2 weeks of antidiarrheal medications (albumin tannate, loperamide) were included in this study. Endoscopy was performed to search for the possible etiologies.

Endoscopy

For colonoscopy, patients were prepared with oral mag-nesium citrate solution and bisacodyl. Meperidine and hyoscine butylbromide were given before the procedure. The examiner and assistant wore masks, eyeglasses and gowns. The endoscope was disinfected using a standard procedure. Multiple biopsies from the gut lesions were obtained. Biopsies were obtained randomly if no lesions were visualized. The specimens were submitted for cultures of viruses, fungi and mycobacteria, and histopathologic studies. For the latter, stains used included hematoxylin-eosin, Gomori-methenamine silver, Ziehl-Neelson, and modified acid fast stain. Immunohistochemical staining for CMV was routinely performed whether or not intranuclear or intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies were present. EGD was performed if the colonoscopy did not define the etiolo-gy for diarrhea. The rules for obtaining biopsies and manip-ulation of the specimens were the same as those for

colon-oscopy. For random biopsies sites sampled were the gastric body, antrum and proximal duodenum. Oral lidocaine for local anesthesia, intramuscular injection of meperidine and hyoscine butylbromide were given before EGD.

Treatment

Specific therapy was administered when an etiology was identified. Amebic colitis was treated with orally administered metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 10 days, followed by iodoquinone 650 mg 3 times per day for 21 days. CMV colitis was diagnosed only when there were changes of colitis by endoscopy and the inclusion body identified by histopathologic study. CMV colitis was treat-ed with intravenous ganciclovir 5 mg/kg twice per day for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by 5 mg/kg once per day as mainte-nance therapy. For tuberculous colitis, 4-drug combined antituberculous therapy (isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide) was continued for 2 months, followed by 7 months of 3-drug combined therapy (isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol). Amphotericin B was adminis-tered at a daily dose of 0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg for those patients with invasive fungal colitis, followed by itraconazole (400 mg/d) or fluconazole (400 mg/d).

Follow-up and statistical analysis

Duration of time required for recovery was recorded as from the date of the colonoscopy to that of resolution of diarrhea. After discharge, patients were regularly fol-lowed in our outpatient department by two of the investi-gators (C-C.H., M-Y.C.). The duration of survival of our patients was censored at the date of last follow-up or the date of death. The postendoscopy follow-up period was defined as from the date of colonoscopy to the date of last Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the 40

HIV-infected patients with diarrhea and negative stool studies

Clinical characteristics Number

Gender (M/F) 37/3

Age (yr, mean) (range) 36 (21-64) Routes of transmission

Homosexual 13

Heterosexual 23

Bisexual 4

Intravenous drug use 5

Duration of anti-HIV (+) to diarrhea (mo)* 31.9 ± 33.4 (0-132) Duration of postendoscopy follow-up (mo)* 9.0 ± 6.4 (1-24) Serum albumin (g/dL)* 3.2 ± 0.7 (1.7-4.5) CD4 (/µL)* 75 ± 143 (1-794) Recovery from diarrhea after treatment 35/40 Recurrence of diarrhea 13/35

*Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (range).

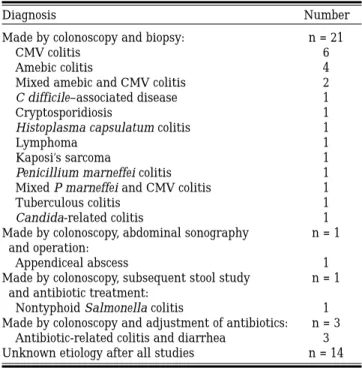

Table 2. Final diagnoses in 40 HIV-infected patients with diarrhea and negative stool studies

Diagnosis Number

Made by colonoscopy and biopsy: n = 21

CMV colitis 6

Amebic colitis 4

Mixed amebic and CMV colitis 2

C difficile–associated disease 1

Cryptosporidiosis 1

Histoplasma capsulatum colitis 1

Lymphoma 1

Kaposi’s sarcoma 1

Penicillium marneffei colitis 1 Mixed P marneffei and CMV colitis 1

Tuberculous colitis 1

Candida-related colitis 1 Made by colonoscopy, abdominal sonography n = 1

and operation:

Appendiceal abscess 1

Made by colonoscopy, subsequent stool study n = 1 and antibiotic treatment:

Nontyphoid Salmonella colitis 1 Made by colonoscopy and adjustment of antibiotics: n = 3

Antibiotic-related colitis and diarrhea 3 Unknown etiology after all studies n = 14

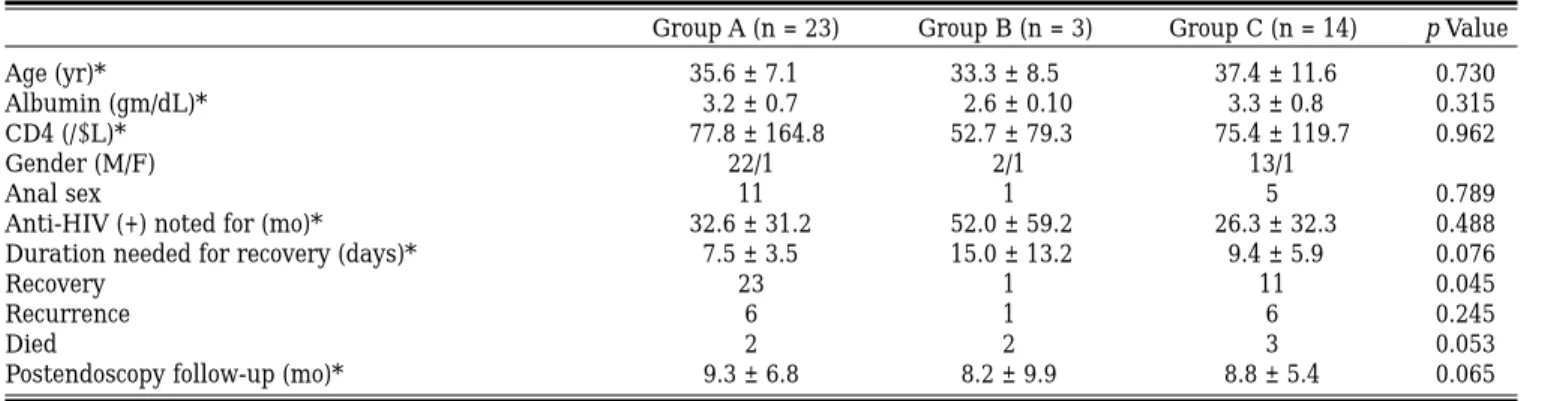

follow-up or the date on which the patient died. To analyze the benefits of treatment, the patients were divided into 3 groups. Group A included patients with a definitive diag-nosis in whom appropriate treatment could be adminis-tered. Group B included patients with a definitive diagno-sis in whom treatment was less than fully effective. Group C included patients without a definitive diagnosis who received only treatment for control of symptoms. Student t test and ANOVA were used for the comparison of contin-uous variables. Fisher exact test was used for comparing the categorical variables. Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier methods were used for the survival analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 40 patients were enrolled (Table 1). Six had been treated with 2 non-nucleoside reverse tran-scriptase inhibitors and 1 protease inhibitor for a median duration of 8 weeks (range 3 to 20 weeks) before endoscopy. Seven patients died during the fol-low-up period, 5 of respiratory failure and 2 of multi-ple organ failure. The final diagnosis and method of diagnosis are summarized in Table 2. Among the 14 patients with chronic diarrhea of unknown etiology, 9 had nonspecific colitis and 5 had no abnormal find-ings at colonoscopy. Randomly obtained biopsies from the patients with no colonoscopic findings did not provide more information for diagnosis. EGD was performed in 18 patients without diagnostic lesions at colonoscopy. Only the patient with lymphoma had gastric and duodenal lesions, which were confirmed by histopathologic study. The others had no positive finding or gastritis at EGD. Randomly obtained biop-sies did not provide diagnostic information.

Of the 22 patients who had diagnostic colono-scopic findings, the distribution of the lesions at colonoscopy was also recorded and analyzed. Ten patients had colonoscopic lesions only proximal to the splenic flexure, 3 had lesions only distal to the splenic flexure, and 9 had lesions in both the proxi-mal and distal colon. Two of 4 patients had amebic colitis only in the proximal colon; 2 of 6 had CMV colitis only in the proximal colon.

Thirty-five of the 40 patients (87.5%) recovered after treatment. Of the 5 patients who did not recov-er aftrecov-er treatment, 1 had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of stomach and intestine, and 1 had disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Both underwent chemotherapy without benefit and died 5 and 30 months later, respectively, of respiratory failure. Two others had nonspecific colitis and 1 had normal endoscopic find-ings. These 3 patients had intermittent diarrhea during the entire follow-up period. One died of sep-tic shock 4 months later, another died of respiratory failure 11⁄2months later, and the other was followed

regularly at our clinic for 7 months.

Thirteen of 35 patients (37.1%) had recurrences of diarrhea during the follow-up. Six of them recov-ered spontaneously within 2 weeks of treatment to control symptoms. Another 7 patients (3 CMV coli-tis, 2 amebic colicoli-tis, 1 Salmonella infection and 1 col-itis without definite diagnosis) had 9 episodes of recurrent diarrhea necessitating repeated endo-scopic studies. Of the 9 episodes, 2 were due to C

difficile–associated disease, 4 to CMV colitis, 1 to

CMV colitis with cryptosporidiosis, and 2 remained undiagnosed. Most of the patients recovered again, except 1 patient with CMV colitis and 1 with CMV and Cryptosporidium infection. They had intermit-tent diarrhea and were still followed regularly with antidiarrheal treatment as needed.

Because CMV and amebic colitis were the two most common causes of diarrhea, we tried to identi-fy the characteristics associated with CMV or ame-bic colitis. In comparing the patients with CMV col-itis and non-CMV colcol-itis, there was no statistically significant difference in age, gender, serum albumin level, CD4 counts, sexual practice, the number of patients recovering from diarrhea, duration of time needed for recovery, recurrence rate after treatment, mortality rate, or duration of follow-up. But patients with CMV colitis appeared to be diagnosed with HIV later than those without CMV colitis (15.3 ± 19.4 vs. 37.4 ± 35.5 months, p = 0.033). There was Table 3. Comparison between dead and surviving patients

Dead (n = 7) Surviving (n = 33) p Value

Age (yr)* 34.0 ± 5.6 36.5 ± 9.4 0.676

Albumin (g/dL)* 2.7 ± 0.4 3.3 ± 0.7 0.022

CD4 (/µL)* 26.6 ± 52.0 85.4 ± 154.3 0.277 Anti-HIV (+) noted for (mo)* 42.9 ± 36.6 29.5 ± 32.8 0.192

Gender (M/F) 7/0 30/3 0.552

Anal sexual practice 3 20 0.326

Recovery 3 32 0.002

Duration needed for recovery (days)* 9.6 ± 9.4 8.5 ± 4.7 0.577

Recurrence 2 11 0.592

Follow-up period (mo)* 4.7 ± 6.9 10.0 ± 6.0 0.013 *Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

also no significant difference with respect to these characteristics between patients with and without amebic colitis. But the patients with amebic colitis were diagnosed with HIV infection earlier than those without amebic colitis (56.7 ± 26.8 vs. 27.5 ± 32.9 months, p = 0.015). Amebic colitis occurred more frequently in patients who had had anal sex (p = 0.003).

Lower serum albumin values and failure of recov-ery after treatment were associated with a worse prognosis (Table 3). Comparisons between the 3 patient subgroups are shown in Table 4. Group A included patients with diarrhea due to ameba, CMV, Clostridium, Histoplasma, Penicillium,

Myco-bacteria, Salmonella, and Candida infection, as well

as antibiotic-related colitis, and appendiceal abscess. Group B included the patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphoma, and cryptosporidiosis. The 14 patients with diarrhea of uncertain etiology belonged to group C. Only recovery rate showed a statistically signifi-cant difference among these 3 groups (Fisher exact test). Further analysis by independent t test showed that the difference came from group A and group C (p = 0.046). Using Cox’s proportional hazard model, we estimated the hazard ratios of recovery for death with adjustment of anti-HIV (+) duration. The hazard ratios were 0.059 (16.95–1) with 95% confidence

inter-val as [0.0085, 0.4082] (2.45–1, 117.6–1). The survival

difference between the patients who recovered from diarrhea after treatment and those who did not was statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

To make the correct diagnosis in AIDS patients with diarrhea, a combination of investigations and a stepwise diagnostic approach are often recommend-ed, starting with less invasive investigations while reserving more invasive tests for those without an identified etiology.10-15However, the benefits of such

a strategy have not been established. According to our study results, colonoscopy could help to make the etiologic diagnosis in 65% (26 of 40) of AIDS

patients with diarrhea and negative stool studies. EGD, instead, was not of assistance in making the etiologic diagnosis in these patients. After diagnosis and treatment, diarrhea resolved in 87.5% of patients. Although 37.1% (13 of 35) developed recur-rences, only 20% (7 of 35) needed additional endo-scopic studies to further identify the cause of the recurrence and 84.6% (11 of 13) of them recovered again after treatment.

The etiology of diarrhea in 35% (14 of 40) of the patients remained unidentified after our stepwise studies. This rate was comparable to that of previ-ous studies (30% to 40%) after all diagnostic efforts.11 Randomly obtained biopsies from the

endoscopically normal area did not aid in the diag-nosis. In our study, the major causes of chronic diar-rhea in AIDS patients undiagnosed by stool studies or unrelieved after 2 weeks of treatment to control the symptoms were CMV and amebic colitis. Both were treated successfully with specific treatment. Other unusual causes of chronic diarrhea, such as intestinal histoplasmosis and penicilliosis, could not be identified until colonoscopy with histopathology and microbiology studies were performed.

Gay bowel syndrome was initially described in sex-ually active homosexual men who were at increased risk for infection with a variety of enteropathogens, including Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter,

Giardia, and ameba.16-18In our study, 6 of 40 patients

(15%) had amebic colitis, which appeared to be asso-ciated with longer duration of anti-HIV antibody pos-itivity and anal sexual practice.

Invasive fungal colitis is rarely described in patients with HIV infection in areas that are endemic for both HIV infection and fungal infection, such as histoplasmosis in the Midwest of the United States19 and penicilliosis marneffei in Southeast

Asia.20Through endoscopy, we were able to diagnose

3 cases of invasive fungal colitis due to these 2 endemic fungi.21All 3 patients with invasive fungal

colitis might have acquired the infection during travel to Southeast Asia and Mainland China. It is likely that invasive fungal colitis is underdiagnosed because not all patients with diarrhea undergo endoscopy.

In considering sigmoidoscopy versus colonoscopy for AIDS patients with diarrhea, colonoscopy seemed to be a better choice based on our study because 45.5% (10 of 22) of patients would have remained undiagnosed if sigmoidoscopy alone had been performed. This might be due to the fact that most of the patients who entered our study had already been screened by stool cultures and routine studies, and that distal colon lesions had already been excluded even though they could be more easi-Figure 1. The survival analysis of patients who recovered

ly diagnosed with stool studies. In accordance with the most common causes of diarrhea in our patients, ameba and CMV were both frequently seen in prox-imal colon or both the most proxprox-imal and most dis-tal ends of colon.22,23

Although the onset of diarrhea in AIDS patients may be a sign of worsening of immune function,12

Smith et al. reported that specific therapy could lead to symptomatic improvement.18 However, there has

been no report as yet to indicate whether the specif-ic treatment will affect survival in AIDS patients. Previous studies had reported that patients with advanced AIDS and “pathogen negative” diarrhea seemed to have a slightly better prognosis than those for whom a cause was detected.24,25In our study, no

statistical difference was detected between these two groups (group A and group C) in terms of the dura-tion of recovery, the postendoscopy follow-up period, or the mortality rate. But a statistically significant difference (p = 0.046) was detected with regard to the rate of recovery. As 2 of the 3 patients in group B had malignant GI tract tumors, their prognosis was the worst among the 3 groups. Similar experience has been reported.11Therefore, specific treatment for the

colitis group of patients is beneficial. In considering the effect of treatment on survival status, we used the Cox proportional hazard model to estimate the hazard ratio of recovery for mortality with the adjustment of positive anti-HIV test period. The haz-ard ratio was 0.059, which meant that the mortality rate was 16.95 times greater for the nonrecovery group than the recovery group. Kaplan-Meier analy-sis also showed that the survival between the recov-ery group and the nonrecovrecov-ery group was signifi-cantly different (p = 0.0004). Our results showed that specific treatment for AIDS patients with diarrhea improved the recovery rate, duration of recovery, and prolonged the survival time.

REFERENCES

1. Smallwood RA. AIDS and the gastroenterologist. J Gastroen-terol Hepatol 1990:5(Suppl 1):45-61.

2. Gazzard B, Blanshard C. Diarrhea in AIDS and other immunodeficiency states. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 1993;7:387-419.

3. Chui DW, Owen RL. AIDS and the gut. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1991;9:291-303.

4. Laughon BE, Druckman DA, Vernon A, Quinn TC, Polk BF, Modlin JF, et al. Prevalence of enteric pathogens in homosex-ual men with and without acquired immunodeficiency syn-drome. Gastroenterology 1988;94:984-93.

5. Smith PD, Lane HC, Gill VJ, Manischewitz JF, Quinnan GV, Fauci AS, et al. Intestinal infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: etiology and response to thera-py. Ann Intern Med 1988;108:328-33.

6. Rene E, Marche C, Regnier B, Saimot AG, Vilde JL, Perrone C, et al. Intestinal infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:773-80. 7. Connolly GM, Shanson D, Hawkins DA, Webster JN, Gazzard

BG. Non-cryptosporidial diarrhea in human immunodefic-iency virus (HIV)-infected patients. Gut 1989;35:195-200. 8. Kotler DP, Franscisco A, Clayton F, Scholes JV, Orenstein JM.

Small intestinal injury and parasitic diseases in AIDS. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:444-9.

9. Orenstein JM, Chiang J, Steinberg W, Smith PD, Rotterdam H, Kotler DP. Intestinal microsporidiosis as a cause of diar-rhea in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient: a report of 20 cases. Hum Pathol 1990;21:475-81.

10. Blanshard C, Francis N, Gazzard BG. Investigation of chron-ic diarrhea in acquired immunodefchron-iciency syndrome: a prospective study of 155 patients. Gut 1996;39:824-32. 11. Dancygier H. AIDS and gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy

1992;24:169-75.

12. Crotty B, Smallwood RA. Investigating diarrhea in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Gastroenterology 1996;110:296-310.

13. Johnson JF. To scope or not to scope: the role of endoscopy in the evaluation of AIDS-related diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;11:261-2.

14. Johnson JF, Sonnenberg A. Efficient management of diarrhea in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med 1990;112:942-8.

15. Gerberding JL. Diagnosis and management of HIV-infected patients with diarrhea. J Antimicrob Chemother 1989;23 (Suppl A):83-7.

Table 4. Comparisons between subgroups A, B and C

Group A (n = 23) Group B (n = 3) Group C (n = 14) p Value

Age (yr)* 35.6 ± 7.1 33.3 ± 8.5 37.4 ± 11.6 0.730

Albumin (gm/dL)* 3.2 ± 0.7 2.6 ± 0.10 3.3 ± 0.8 0.315

CD4 (/µL)* 77.8 ± 164.8 52.7 ± 79.3 75.4 ± 119.7 0.962

Gender (M/F) 22/1 2/1 13/1

Anal sex 11 1 5 0.789

Anti-HIV (+) noted for (mo)* 32.6 ± 31.2 52.0 ± 59.2 26.3 ± 32.3 0.488 Duration needed for recovery (days)* 7.5 ± 3.5 15.0 ± 13.2 9.4 ± 5.9 0.076

Recovery 23 1 11 0.045

Recurrence 6 1 6 0.245

Died 2 2 3 0.053

Postendoscopy follow-up (mo)* 9.3 ± 6.8 8.2 ± 9.9 8.8 ± 5.4 0.065 Group A included patients with definitive diagnosis in whom appropriate treatment could be administered. Group B included patients with definitive diagnosis but for whom treatment was not fully effective. Group C included patients without definitive diagno-sis who received only treatment to control symptoms.

16. Antony MA, Brandt LJ, Klein RS, Berstein LH. Infectious diarrhea in patients with AIDS. Dig Dis Sci 1988;33:1141-6. 17. Schmerin MJ, Gelston A, Jones TC. Amebiasis: an increasing

problem among homosexuals in New York City. JAMA 1977; 238:1386-7.

18. Sohn N, Robilotti JG. The gay bowel syndrome: a review of colonic and rectal conditions in 200 male homosexuals. Am J Gastroenterol 1977;67:478-84.

19. Clarkston WK, Bonacini M, Peterson I. Colitis due to

Histo-plasma capsulatum in the acquired immunodeficiency

syn-drome. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:913-6.

20. Sirisanthana T. Infection due to Penicillium marneffei. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1997;26:701-4.

21. Ko CI, Hung CC, Chen MY, Hsueh PR, Hsiao CH, Wong JM. Endoscopic diagnosis of intestinal penicilliosis marneffei:

report of three cases and review of the literature. Gastro-intest Endosc 1999;50:111-4.

22. Dieterich DT, Rahmin M. Cytomegalovirus colitis in AIDS: presentation in 44 patients and a review of the literature. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1991;4(Suppl 1):S29-35. 23. Murray JG, Evans SJ, Jeffery PB, Halvorsen RA Jr.

Cytomegalovirus colitis in AIDS: CT features. Am J Roentgenol 1995;165:67-71.

24. Wilcox CM, Schwartz DA, Costonis G, Thompson SE. Chronic unexplained diarrhea in human immunodeficiency virus infection: determination of the best diagnostic approach. Gastroenterology 1996;110:30-7.

25. Blanshard C, Gazzard BG. Natural history and prognosis of diarrhea of unknown cause in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Gut 1995;36:283-6.

Submission of FINAL manuscript on diskette

Gastointestinal Endoscopy strongly encourages the submission of final manuscripts on disk. Although files created with WordPerfect are preferred, please send your final manuscript in any electronic format. On your disk, please indicate computer system (e.g., IBM, MacIntosh) and word processing software used (e.g., WordPerfect 6.1).