Contents lists available atScienceDirect

International Journal of Information Management

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i j i n f o m g tThe intellectual development of the technology acceptance model:

A co-citation analysis

Chun Hua Hsiao

a,b,∗, Chyan Yang

a,1aInstitute of Business and Management, National Chiao Tung University, No. 118, Sec. 1, Chung-Hsiao West Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan bDepartment of Marketing, Kainan University, No. 1 Kainan Road, Luzhu Shiang, Taoyuan 33857, Taiwan

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Available online 16 August 2010

Keywords:

Technology acceptance model Co-citation

e-Commerce Hedonic

a b s t r a c t

The goal of this paper is to present a visual mapping of intellectual structure in two-dimensions and to identify the subfields of the technology acceptance model through co-citation analysis. All the citation documents are included in the ISI Web of Knowledge database between 1989 and 2006. By using a sequence of statistical analyses including factor analysis, multidimensional scaling, and cluster analysis, we identified three main trends: task-related systems, e-commerce systems, and hedonic systems. The findings yielded managerial implications for both academic and practical issues.

© 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The investments in information systems (IS) for today’s organi-zations have expanded dramatically, accounting for about 50% of new capital investment (Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003). Despite the considerable investments in IS, about 74% of IS and software engineering projects are delayed, exceed budget, and fail to meet the functional expectations (Schepers & Wetzels, 2007). Therefore, identifying influential factors on technology acceptance across different settings have been an important and focal interest in IS for both researchers and practitioners.

Among numerous theories, the technology acceptance model (TAM) was considered to be the most influential and valid model for describing an individual’s acceptance of information systems (Davis, 1989; Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989). Two specific behavioral beliefs – perceived ease of use (PE) and perceived use-fulness (PU) – determine an individual’s behavioral intention to use (BI) a technology. Derived from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) which posits that human behav-ioral intention is affected by attitude and subjective norm, TAM is specialized for the use of information systems.

In the early stages, information systems were designed to improve task performance and efficiency. Those job-related infor-mation systems can be categorized as autoinfor-mation software (e.g., spreadsheet, text-editor), office systems (e.g., word processor,

∗ Corresponding author at: Department of Marketing, Kainan University, No. 1 Kainan Road, Luzhu Shiang, Taoyuan 33857, Taiwan. Tel.: +886 3 33412500; fax: +886 3 2705737.

E-mail addresses:maehsiao@gmail.com(C.H. Hsiao),professor.yang@gmail.com

(C. Yang).

1Tel.: +886 2 2349 4924; fax: +886 2 2349 4926.

spreadsheet, database programs), system developments (e.g., pro-gramming tools, software maintenance tools), and communication systems (e.g., e-mail, voice mail, mobile phone, face-to-face meet-ing) (Legris, Ingham, & Collerette, 2003; Lim, Lee, & Nam, 2007). The rapidly increasing tendency of Internet usage and worldwide commerce has led researchers to work on the general topic of e-commerce (Gefen, Karahanna, & Straub, 2003b; Heinze & Hu, 2006; Lin, 2006; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Major theoretical and empiri-cal studies have attempted to identify influential factors such as trust and other innovation factors in attracting web users and in consuming products via websites (Venkatraman & MacInnis, 1985; Yiu, Grant, & Edgar, 2007). Therefore, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PE) may not fully explain the Internet users’ motives, asDavis (1989)argued that research studies on any new IT acceptance need to address how other variables affect PU, PE, and the end users’ acceptance.

The popularity of TAM research studies can be found from journal citations in the ISI Web of Knowledge database whereby Davis’s (1989)article received 424 journal citations by the begin-ning of 2000, 698 journal citations by 2003, and currently nearly 2000 journal citations. Even though literature reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted to test the convergence of TAM relationships across difference settings and provide an objec-tive statement in TAM (King & He, 2006; Schepers & Wetzels, 2007), previous researches have not yet answered the following addressed questions: what intellectual subfields have emerged from TAM research? In which reference disciplines are these sub-fields grounded? To what extent do these subsub-fields represent active areas of current research? Additionally, what are the emerging research areas in TAM?

To answer the above questions, bibliometrics, a mathematical and statistical analysis, was used to detect the homogeneous areas

0268-4012/$ – see front matter © 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.07.003

in research networks and to assess the movement and interactions within and between fields (Small, 1973; Sugimoto, Pratt, & Hauser, 2008; White & Griffith, 1981; Zitt & Bassecoulard, 1996). One of the best-known structuring methods of bibliometrics is co-citation analysis (Borgman, 1989).

A co-citation analysis was used to interpret the similarity of content between two documents by counting the number of doc-uments which have been cited in a pair (Garfield, 1979; Small, 1973). Its premise is that bibliographic references of a scientific paper are often considered to be important in the development of research and signal their influences, so they can serve as the theo-retical and empirical foundations of the study (Ramos-Rodriguez & Ruiz-Navarro, 2004). Therefore, it is possible to identify networks of authors or documents belonging to the same discipline or field by analyzing the references. More elaborately, frequently cited docu-ments are likely to have a greater influence on the discipline than those less cited (Culnan, 1986). If two documents are frequently jointly cited, then they are likely to share similar or related concepts (White & Griffith, 1981). By counting and analyzing the frequency of two documents or authors cited in the same work, we can iden-tify groups of closely related documents which address the same research questions (Price & De Solla, 1965; Small, 1973).

The goals of this paper are in line with the co-citation method: (1) identify the subfields within TAM; (2) analyze the relational links between the subfields; (3) graphically map the intellectual structure in a two-dimensional space; and (4) recognize the main trends within TAM. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to apply bibliometric techniques in the field of TAM. Therefore, the major contribution of this paper is to provide an intellectual structure and trends within the field of TAM from an objective and quantitative perspective.

2. Literature review

In order to document the current subfields and the emergence of new research areas in TAM, this section reviews both the general TAM literature and literature on co-citation analysis.

2.1. Technology acceptance model

Information technology (IT) offers a great opportunity to improve job performance; however, the benefits gained from it often depend on the users’ willingness to accept and use these avail-able systems. Various theories have been presented to investigate factors affecting an individual’s acceptance toward a new infor-mation system. Among those studies, the technology acceptance model (TAM) has received considerable attention in the informa-tion systems (IS) field and has been tested and extended by many researchers who specialize in IS usage (Mathieson, Peacock, & Chin, 2001). It was developed from the social psychology Theory of Rea-soned Action (TRA) which posited that human behavioral intention is affected by attitude and subjective norm (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The original TAM did not include sub-jective norm. However,Venkatesh and Davis (2000)found that it influences both perceived usefulness and intention after conduct-ing four longitudinal field studies, so they included the subjective norm into TAM2.

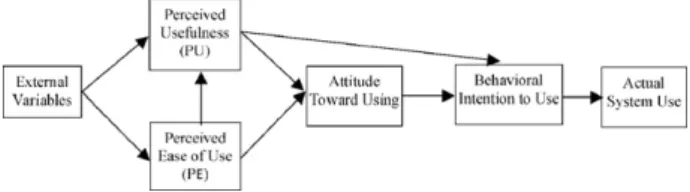

The technology acceptance model (TAM) explains user accep-tance of a technology based on user perceptions (Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989). The mediating roles of perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PE) are examined in the relationship between external variables and the intention of system usage. While PU is defined as “the degree to which a person believes that using a par-ticular system would enhance his or her job performance,” PE is defined as “the degree to which using the technology will be free

Fig. 1. Original technology acceptance model (Davis et al., 1989).

of effort” (Davis, 1986, 1989). Both PU and PE influence the indi-vidual’s attitude toward using an information system. Attitude and PU, in turn, predict the individual’s behavioral intention to use it. Among these beliefs, PE is hypothesized as a predictor of PU (see Fig. 1).

IS research has long focused on how and why individuals adopt new information technologies. Since the mid-eighties, IS researchers have concentrated their efforts in developing and test-ing models that could help to predict system use (Chau, 1996; Cheney, Mann, & Amoroso, 1986). Among which, TAM has been widely recognized as a robust, powerful, and economical model for predicting the acceptance of information technology. However, after conducting a review of 22 articles according to some crite-ria from six MIS leading journals between 1980 and 2001,Legris et al. (2003) presented that either TAM or TAM2 explains only 40% of system use. This indicates that there are other significant factors affecting PU, PE, and user intention of new technology. Nev-ertheless, results from two recent meta-analysis studies still show that TAM is a valid and robust model with wide application under various conditions such as user types, usage types, or types of infor-mation systems (King & He, 2006; Schepers & Wetzels, 2007).

Recently, TAM research studies have turned into an important issue – moderating effects, because by including moderators, the limited explanatory power of TAM can be enhanced and the incon-sistent relationships among studies can be solved (Sun & Zhang, 2006; Venkatesh et al., 2003). For example,King and He (2006) conducted a meta-analysis examining the moderating effects of user types and usage types. The results show that Internet usage was different from other types of usage such as task applications, general use (such as e-mail and telecommunication), and office applications.Schepers and Wetzels (2007)discussed three types of moderators: individual-related factors (types of respondents), technology-related factors (types of technology), and contingent factors (culture). Their results confirmed the roles of all moder-ators especially with the significant influence of subjective norm on perceived usefulness and behavioral intention to use. There-fore, other moderation variables, such as age, experience, personal innovativeness, or computer self-efficacy, are suggested for further investigation.

2.2. Co-citation analysis

In this study we intend to identify the subfields characterized by the intellectual nature of specialties and the main trends within TAM. Co-citation analysis can provide an objective and quantitative means to meet our goals. There are different levels of co-citation analysis: document co-citation analysis, author co-citation analy-sis (ACA), and journal co-citation analyanaly-sis.Small (1973)introduced document co-citation analysis by evaluating the network created when documents are linked according to their joint citations by subsequent documents. Author co-citation analysis, by contrast, uses authors instead of documents to produce maps of promi-nent authors within a selected field by means of computational and graphic display techniques (White, 1990; White & Griffith, 1981).McCain (1991a, 1991b)introduced journal co-citation anal-ysis, which treats representative journals of each field as the units

of analysis. These studies focused primarily on the journal–journal relationship to evaluate the importation and exportation of cita-tions between all given pairs of journals (Sugimoto et al., 2008). The current study adopts document co-citation, because articles from research journals have gone through a critical review of fellow researchers, and this can enhance the reliability of results ( Ramos-Rodriguez & Ruiz-Navarro, 2004).

Small (1973)presented the document co-citation method and defined it as a measure of the relationship degree between papers as perceived by the population of citing authors. It is under the assumption that bibliographic citations are an acceptable proxy for the actual influence of various information sources on a research project (Culnan, 1986). Citations were more potent con-cept symbols than words because a high citation rate reflected peer recognition (Small, 2003). Since the highly cited documents, or “concept symbols,” represent the key concepts, methods, or ideas shared by the citing documents in a field, then the co-citation patterns can be used to map out in great detail the relation-ships between these key ideas (Small, 1973).Franklin and Johnston (1988)suggested that co-citation could identify coherent research problem areas by classifying and grouping current scientific papers through their common referencing to clusters of highly cited and highly co-cited works. Accordingly, numerous studies have demon-strated that the co-citation method is a valid approach to explore the intellectual structure of a scientific discipline (Acedo, Barroso, & Galan, 2006; McCain, 1999; Nerur, Rasheed, & Natarajan, 2007; Ramos-Rodriguez & Ruiz-Navarro, 2004; Small, 1973; White & Griffith, 1981; White & McCain, 1998).

Co-citation could be used to establish a cluster or “core” of ear-lier literature for a specialty structure of science (Small, 1973). The pattern of linkages among key documents establishes a struc-ture of map for the specialty in a field. Co-citation patterns change when new papers continually appeared in the clusters due to their increasing citation or co-citation and old papers dropped out. Through studying these changing structures, the co-citation method provided a mean to monitor the development of scientific fields and to assess the degree of interrelationship among spe-cialties (Small, 1973). Thus, changes in co-citation patterns over time may be used to document the scientific trend within a field (Sullivan, Koester, White, & Kern, 1980).

3. Methodology

In this section, we introduced the co-citation method and sta-tistical analyses to delineate the intellectual structure of TAM. After retrieving the co-citation matrix with document co-citation method, a sequence of statistical analyses was performed. First, we adopted factor analysis to extract the key conceptual specialties in TAM. Then, followed by cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling (MDS), an intellectual mapping of TAM based on citation patterns was developed.

3.1. Co-citation method

The co-citation method is based on a frequency count that two documents or authors are cited in pairs in the same work (Small, 1973). Its goal is to identify groups of closely related documents which can be considered as the same ‘research front’ (Price & De Solla, 1965). Using the method of document co-citation analysis, we started from a set of source documents that make up the core of the discipline or base literature, from which the co-citation matrix is obtained. Therefore, there are two sets constituting a co-citation cluster within our model: (1) a set of source documents which rep-resent highly cited and co-cited referenced works, and (2) a set of citing documents which cite those source documents. Identifying

the source documents is a critical stage, for the set of source doc-uments must be as large as possible to cover all the development within the theory (Acedo et al., 2006). Once the source documents are selected, we can form a set of citing documents which cite those source documents. From the analysis of another larger set of cit-ing documents, we can collect more perceptions into the theory’s trends, dissemination, and related issues.

3.1.1. Selection of source documents

To obtain a collection of representative research papers related to TAM, we retrieved our data from the ISI Web of Knowledge database for the following reasons: (1) it is the world’s leading cita-tion database and enjoys a great reputacita-tion; (2) its citacita-tion database is abundant in covering more than 10,000 high impact journals; (3) it is highly regarded and receives great popularity from researchers; (4) it provides a systematic and objective means to trace related information efficiently. In addition, many researches on co-citation analysis also retrieved their core documents from the ISI database (Acedo et al., 2006; McCain, 1990; Nerur et al., 2007; Small, 1973; White & Griffith, 1981).

We retrieved the set of all documents with the key word “tech-nology acceptance model” or “TAM” in ISI for the year 2008. This procedure resulted in a list of 518 documents. In order to ensure that only influential articles with a significant impact are selected, we selected only those documents with 30 or more citations. The threshold of 30 citations has been used by other research stud-ies (Acedo et al., 2006; Culnan, 1986). As a result, an initial 66 papers constituted the set of source documents, but only one doc-ument published after 2005. This was a drawback of the citation frequency threshold. It favors older documents over new ones because the latter are unlikely to reach the threshold due to pub-lication lags. Therefore, we decided to add documents published after 2005 by lowering the threshold to 20 citations. The different threshold strategy is adopted by other bibliometric studies (Acedo et al., 2006; Culnan, 1986; Rowlands, 1999). We then included six more documents, resulting in five documents published in 2005 and one in 2006. In sum, 72 articles made up the set of source documents.

3.1.2. Retrieval of co-citation matrix

After the retrieving of source documents, the next stage was to perform a co-citation matrix based on the above 72 most cited doc-uments. From ISI, we retrieved a total of 7133 articles (the master set of citing documents) that cited the above 72 source documents. Next, each of the 72 documents was paired with every other doc-ument within this set and the co-cited frequency of each pair was computed. These counts then formed a 72× 72 square co-citation matrix in which the main diagonal is simply considered as missing data, because there is no point in counting the co-citation frequency of a document with itself (McCain, 1990; Ramos-Rodriguez & Ruiz-Navarro, 2004). This co-citation matrix was then transformed into Pearson’s correlation matrix for the following statistical analyses.

There is considerable debate over Pearson’s correlation matrix. The major critique of Pearson’s r is from the study ofAhlgren, Jarneving, and Rousseau (AJ & R) (2003)in which Pearson’s r was used as a measure of similarity between authors, but it failed two tests in stability of measurement. However,White (2003)rebutted their results by starting with a single set of authors, obtaining a correlation for each pair by using the data from the study of AJ & R. Despite r’s fluctuations, results of clusters and maps based on Pear-son’s r showed no difference between the combined and separate groups. Moreover, the results were also very similar to those based on a cosine similarity measure and a chi square dissimilarity mea-sure.White (2003)then concluded that r performs well enough for the purposes of ACA.

3.2. Factor analysis

Factor analysis allows us to study the quality of data reduc-tion in more dimensions with precise numbers, and it is commonly used in co-citation analysis (Leydesdorff & Vaughan, 2006; Nerur et al., 2007; White & McCain, 1998). With an orthogonal (Vari-max) rotation of the extracted factors, factor analysis produces the uncorrelated factors. Most documents have high loadings on only one factor. In document citation analysis, a factor is interpreted or defined by those documents with high loadings greater than±0.7. Thus, each factor reveals the underlying subject matter. The amount of variance explained by a factor may represent its contribution to the conceptual foundation of the field (McCain, 1990).

Documents in specialized areas tend to cite some researchers’ concepts and be co-cited by others within the field (McCain, 1990). Therefore, those documents are prone to load on the same factor. Each subfield corresponding to the extracted factor represents an

intellectual specialty that is defined by authors who load highly on that subfield/factor (Nerur et al., 2007).

3.3. Hierarchical cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling The goal of cluster analysis is to develop subgroups so that objects within a particular subgroup are more alike than those in a different subgroup. In co-citation analysis, cluster analysis is used to group documents on the basis of shared attributes, so they can provide insights into the intellectual organization of a given field (McCain, 1990).

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) is a data reduction procedure to generate a map which shows the relative positions of the papers or authors. The mapping principle is that the more similar two papers are, the closer the two papers will be located in the map (Leydesdorff & Vaughan, 2006). MDS uses the stress measure and R2(proportion of variance) as indicators of how good the fit is. In Table 1

Set of source documents.

No. Author (year) Source No. Author (year) Source

1 Davis (1989) MIS Quarterly 37 Davis and Venkatesh (1996) International Journal of Human–Computer Studies 2 Taylor and Todd (1995b) Information Systems Research 38 Van der Heijden (2004) MIS Quarterly

3 Venkatesh and Davis (2000) Management Science 39 Chau and Hu (2002) Information & Management 4 Venkatesh et al. (2003) MIS Quarterly 40 Plouffe et al. (2001) Information Systems Research 5 Venkatesh (2000) Information Systems Research 41 Doll, Hendrickson, and Deng

(1998)

Decision Sciences

6 Gefen et al. (2003a) MIS Quarterly 42 Wixom and Todd (2005) Information Systems Research 7 Venkatesh and Davis (1996) Decision Sciences 43 Bhattacherjee (2001a) Decision Sciences

8 Venkatesh and Morris (2000) MIS Quarterly 44 Grandon and Pearson (2004) Information & Management 9 Gefen and Straub (1997) MIS Quarterly 45 Gefen et al. (2003b) IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management 10 Szajna (1996) Management Science 46 Van der Heijden (2003) Information & Management 11 Igbaria et al. (1997) MIS Quarterly 47 Briggs, De Vreede, and

Nunamaker (2003)

Journal of Management Information Systems 12 Taylor and Todd (1995a) MIS Quarterly 48 Hsu and Lu (2004) Information & Management 13 Moon and Kim (2001) Information & Management 49 Bagozzi, Davis, and Warshaw

(1992)

Human Relations 14 Agarwal and Prasad (1999) Decision Sciences 50 Al-Gahtani and King (1999) Behaviour & Information

Technology

15 Koufaris (2002) Information Systems Research 51 Hong et al. (2001) Journal of Management Information Systems 16 Straub, Limayem, and Karahanna

(1995)

Management Science 52 Hackbarth, Grover, and Yi (2003)

Information & Management 17 Hu, Chau, Sheng, and Tam (1999) Journal of Management

Information Systems

53 Vijayasarathy (2004) Information & Management 18 Venkatesh (1999) MIS Quarterly 54 Gefen and Keil (1998) Data Base For Advances in

Information Systems 19 Legris et al. (2003) Information & Management 55 Pavlou and Fygenson (2006) MIS Quarterly

20 Bhattacherjee (2001b) MIS Quarterly 56 Bruner and Kumar (2005) Journal of Business Research 21 Lederer, Maupin, Sena, and Zhuang

(2000)

Decision Sciences 57 Morris and Dillon (1997) IEEE Software 22 Chin and Todd (1995) MIS Quarterly 58 Yi and Hwang (2003) International Journal of

Human–Computer Studies 23 Devaraj et al. (2002) Information Systems Research 59 Sussman and Siegal (2003) Information Systems Research 24 Jackson, Chow, and Leitch (1997) Decision Sciences 60 Riemenschneider, Harrison,

and Mykytyn (2003)

Information & Management 25 Karahanna and Straub (1999) Information & Management 61 Luarn and Lin (2005) Computers in Human Behavior 26 Dishaw and Strong (1999) Information & Management 62 Shih (2004) Information & Management 27 Pavlou (2003) International Journal of

Electronic Commerce

63 Amoako-Gyampah and Salam (2004)

Information & Management 28 Chen et al. (2002) Information & Management 64 Nysveen et al. (2005) Journal of Management

Information Systems 29 Igbaria and Iivari (1995) Omega-International Journal

of Management Science

65 Ong et al. (2004) Information & Management 30 Agarwal and Venkatesh (2002) Information Systems Research 66 Featherman and Pavlou (2003) International Journal of

Human–Computer Studies 31 Straub, Keil, and Brenner (1997) Information & Management 67 Carter and Belanger (2005) Information Systems Journal 32 Venkatesh and Brown (2001) MIS Quarterly 68 Shang et al. (2005) Information & Management 33 Chau and Hu (2001) Decision Sciences 69 Saade and Bahli (2005) Information & Management 34 Lucas and Spitler (1999) Decision Sciences 70 Lee et al. (2005) Information & Management 35 Lin and Lu (2000) International Journal of

Information Management

71 Yu et al. (2005) Information & Management 36 Wu and Wang (2005) Information & Management 72 Lai and Li (2005) Information & Management

Table 2

Factors, conceptual theme, source documents.

Factor Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

Conceptual theme Theory development of TAM e-Commerce Multi-purposes of TAM

Major source documents Lucas and Spitler (1999) Pavlou and Fygenson (2006) Shang et al. (2005)

Davis and Venkatesh (1996) Wixom and Todd (2005) Yu et al. (2005) Igbaria et al. (1997) Gefen et al. (2003b) Nysveen et al. (2005)

Jackson et al. (1997) Pavlou (2003) Lai and Li (2005)

Taylor and Todd (1995b) Devaraj et al. (2002) Vijayasarathy (2004) Agarwal and Prasad (1999) Agarwal and Venkatesh (2002) Shih (2004)

Szajna (1996) Van der Heijden (2004) Bruner and Kumar (2005)

Straub et al. (1997) Featherman and Pavlou (2003) Hsu and Lu (2004) Igbaria and Iivari (1995) Bhattacherjee (2001a) Van der Heijden (2003) Hu et al. (1999) Carter and Belanger (2005) Saade and Bahli (2005)

Gefen and Keil (1998) Koufaris (2002) Wu and Wang (2005)

Karahanna and Straub (1999) Sussman and Siegal (2003) Lin and Lu (2000) Venkatesh (1999) Bhattacherjee (2001b) Luarn and Lin (2005) Doll et al. (1998) Venkatesh and Brown (2001)

Eigen values 44.57 10.12 6.62

Percent of variance explained 59.12 14.06 9.19 Total variance explained: 82.40%.

Only 14 out of 52 documents with higher loading in factor 1 were reported.

general, the more dimensions in the solution, the lower the stress and the higher the R2. However, co-citation analysis has primarily

focused on the two-dimensional solution for the benefit of visual-izing the conceptual distance between various intellectual strands of research without losing its explanatory power (McCain, 1990).

4. Results

4.1. Results of the co-citation analysis

There are 72 articles in the set of our source documents as seen inTable 1. Deriving from the set of source documents, a 72× 72 co-citation matrix was formed, among which the rows and columns are the source documents and the figures in the cells represent the frequency of co-citations obtaining from each pair of documents. Based on this co-citation matrix, we estimated Pearson’s correla-tion matrix as an input for the subsequent statistical analyses.

We used Person’s r as a measure of similarity rather than the raw co-citation frequency for three reasons (Acedo et al., 2006; Ramos-Rodriguez & Ruiz-Navarro, 2004). First, it serves as mea-sure of the degree of similarity which may indicate the likeness or close relationship across all documents. Second, it overcomes dif-ferences of scale when the cited frequencies between two similar documents show extreme discrepancy (Kerlinger, 1973; White & McCain, 1998). Finally, its standardized scale can avoid the scale effect.

The Pearson’s correlation matrix then served as an input for sub-sequent statistical analyses (e.g., factor analysis, multidimensional scaling (MDS), and cluster analysis) (Rowlands, 1999; White, 2003; White & Griffith, 1981). Multidimensional scaling or factor anal-ysis allows us to project the n-dimensional data in a space into lower dimensionality. These statistical analyses are depicted in the following sections.

4.2. Factor analysis

Based on the correlation matrix, we conducted factor analysis with a Varimax rotation to extract the key conceptual themes in the TAM field.Table 2shows that three factors are extracted with 82.40% of the explained variance. Factor 1, constituting nearly two-thirds of our source documents, represents the theory development of TAM. It contains most of the early representative works in the-ory development of TAM research, including thethe-ory introduction (Davis, 1989), validation (Igbaria, Zinatelli, Cragg, & Cavaye, 1997; Taylor & Todd, 1995b), extension (e.g., TAM2 (Venkatesh & Davis,

2000)), and critical review (Legris et al., 2003). At the initial stage of TAM development, researchers had made any efforts to enhance the applicability and predicting power of TAM by incorporating addi-tional variables (e.g., self-efficacy, subjective norm, motivation and involvement) and other theories (TRA, TPB, IDT, etc.).

Factor 2 represents the view of e-commerce with documents dating from 2001 to 2006. Approximately 20% of our source docu-ments were constituted by factor 2. The flourish of e-commerce has attracted lots of researchers to work on this topic with the applica-tion of TAM. Corresponding variables such as trust or perceived risk have been acknowledged to be the most important variable in this emerging e-commerce research among TAM (Gefen, Karahanna, & Straub, 2003a; Stewart, Pavlou, & Ward, 2002). In the same way, trust-related variables are also incorporated into other intention-based models (e.g., TPB and TRA) (Devaraj, Fan, & Kohli, 2002; Pavlou, 2003).

Factor 3 was named as a multi-purpose group, among which var-ious electronic devices are used. It contains about 18% of our source documents, most of which were published in 2005. The purposes for using those electronic devices vary from web-navigating, com-munication (Nysveen, Pedersen, & Thorbjornsen, 2005), payment (Shang, Chen, & Shen, 2005; Wu & Wang, 2005), gaming (Hsu & Lu, 2004), and online learning (Lin & Lu, 2000; Saade & Bahli, 2005). The most critical element appearing in factor 3 is the concept of perceived ‘enjoyment’ or ‘fun.’

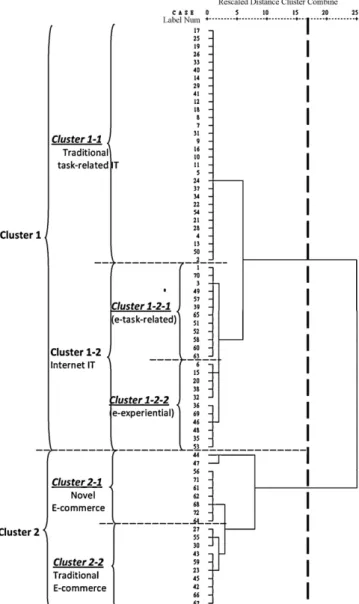

4.3. Hierarchical cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling In order to graphically delimit the groups and subgroups of TAM, a hierarchical cluster analysis with Ward’s method and multidi-mensional scaling (MDS) were carried out. All documents were analyzed into Dendrogram and MDS was seen in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively (except documents 44 and 47 due to the fact that the factor loading was less than 0.5). The stress value (0.189, lower than an acceptable value 0.2) and R2(0.92 for two-dimensions) showed

an outstanding fit for the data (McCain, 1990). As a result, two large groups emerged from left to right on the horizontal axis. Group 1 with most documents from factor 1, and group 2 with documents from factors 2 and 3. Each group was then divided by two subgroups to thoroughly investigate within the specialties of TAM.

The horizontal axis in Fig. 3 represented the chronological development of TAM including theory introduction, validation, and extension (from left to right along the x-axis). On the other hand, the vertical axis indicated the extensions or applications of TAM from tradition (below the x-axis) to novelty (above the

Fig. 2. Hierarchical cluster analysis.

x-axis). Group 1 showed the fundamental works of TAM, compris-ing some early representative works of TAM (e.g.,Davis, 1989; Venkatesh & Davis, 1996, 2000; Venkatesh et al., 2003). Within group 1, most documents were identified as task-related informa-tion systems. For more detailed informainforma-tion, we divided group 1 into two subgroups: traditional ‘task-related’ information systems and ‘Internet-related’ information systems. Traditional task-related subgroup represents offline IS, including office automation (e.g., spreadsheet and word processing) and software development (e.g., accounting and financial management systems) (e.g.,Agarwal & Prasad, 1999; Moon & Kim, 2001; Venkatesh & Brown, 2001). The other ‘Internet-related’ group can be separated into two sub-groups. The Internet task-related subgroup involves tasks related to online learning, digital library, and organization learning (e.g., Hong, Thong, Wong, & Tam, 2001; Lee, Cheung, & Chen, 2005; Ong, Lai, & Wang, 2004). The Internet ‘experiential’ (or ‘hedonic’) sub-group, includes online gaming, online surfing, online shopping, and even online learning while perusing enjoyment at the same time (e.g.,Lin & Lu, 2000; Saade & Bahli, 2005; Van der Heijden, 2004).

Group 2 was comprised of e-commerce documents which can also be divided into two subgroups. The larger one located below the axis was called ‘traditional’ e-commerce, and the small one called the ‘novel’ e-commerce. In the traditional e-commerce sub-group, trust-related variables (trust, perceive risk, and credulity) were found to be essential and incorporated into TAM (e.g.,Gefen et al., 2003b; Pavlou, 2003). The other emerging subgroup was ‘novel’ e-commerce. It was entitled as the following because all documents were published in 2005, and also because some new devices such as interactive televisions, PDAs, or mobile phones were applied to e-commerce (e.g.,Bruner & Kumar, 2005; Nysveen et al., 2005; Yu, Ha, Choi, & Rho, 2005).

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary

By using document co-citation analysis, the current paper intends to provide intellectual development of TAM and identify its dissemination and main trends. Seventy-two of the most frequently cited papers in the field of TAM were collected and analyzed. Synthesized from factor analysis, cluster analysis, and multidimen-sional scaling, three main trends in the applied context of TAM were

identified: (1) task-related systems; (2) e-commerce systems; and (3) hedonic systems.

First, in the early theory development stage, TAM was mostly applied to task-related (or productivity-oriented) information sys-tems including both offline and online IS. While the offline (or traditional) task-related IS was involved in office automation sys-tems, the online task-related IS was more connected to knowledge or learning based systems via the Internet.

The second stream of research focus was e-commerce. The high Internet penetration has facilitated e-commerce development and caused interest of researchers in the application of TAM. Therefore, substantial amounts of TAM research have been focused on the general topic of e-commerce.

Last, the third and recent trend of TAM – hedonic systems – emerged. The concept of ‘hedonic,’ similar to the concept of ‘experiential,’ denotes pleasure or happiness (Novak, Hoffman, & Duhachek, 2003).Van der Heijden (2004)classified some types of information systems as hedonic and productivity information sys-tems. The ‘hedonic’ IS was usually connected to home and leisure activities, focusing on the fun or novel aspect of information sys-tems, such as fashion or amusement websites, instant messenger services, online games, online shopping, or mobile services. The accompanied devices which are suitable for enjoying the above purposes are interactive televisions, PDAs, or mobile phones. 5.2. Discussion

Three main trends of TAM were obtained from this study and were discussed as follows. The first emerging trend of TAM is task-related or utilitarian information systems, including job-task-related systems, e-learning, and management information systems. Since the purpose and functions of task-related IS are to enhance users’ task performance while concurrently encouraging efficiency, we can expect that it will continue to play a dominant role within TAM. In the task-related IS such as training programs or e-learning sys-tems, perceived usefulness and self-efficacy are considered to have stronger positive effects on usage than perceived ease of use (Hong et al., 2001; Igbaria et al., 1997; Igbaria & Iivari, 1995; Karahanna & Straub, 1999; Ong et al., 2004). One possible explanation is that individuals are likely to accept a new technology if they recognize that it can help them to build computer efficacy and improve their work performance. In TAM2 and other research, subjective norm was suggested to be included in TAM (Legris et al., 2003; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Venkatesh & Morris, 2000). Other variables such as organizational factors or management support also have a direct influence on both ease of use and perceived usefulness, and indirect effects on usage (Igbaria et al., 1997; Igbaria & Iivari, 1995).

The second trend in TAM research is e-commerce. Even though e-retailing could serve as an alternative to traditional brick-and-mortar shopping channels by overcoming time and spatial barriers, by providing an abundance of product information, and by pro-cessing orders faster (Devaraj et al., 2002; Vijayasarathy, 2004), the critical issue is how to identify, attract, and retain customers since online shoppers are typically regarded as less loyal (Jarvenpaa & Todd, 1997; Stewart et al., 2002). Nevertheless, trust appears to be the most important factor in the context of e-commerce for it is the key to many relationships (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Previous research also indicated that online shoppers’ purchase behaviors were influenced by their assessments of the website for such web-based stores using Internet technology for communications and transactions (e.g.,Agarwal & Venkatesh, 2002; Gefen et al., 2003b; Koufaris, 2002; Van der Heijden, 2003). Thus, except for trust build-ing, a vendor’s website requires some attractive mechanisms and ease of use to entice customers to visit the website.

Finally, the third and recent trend of TAM – hedonic systems – emerged. In this trend, intrinsic motivational factors such as

perceived playfulness or ease of use have a more powerful effect than perceived usefulness has on building positive attitude toward IS (Moon & Kim, 2001; Van der Heijden, 2004). Different from utilitarian IS, the concept of hedonic systems focuses on the fun-aspect of using information systems, and often involves seeking multiple sensory channels through fancy websites, interactive tele-visions, PDAs, and especially mobile phones (Bruner & Kumar, 2005; Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Hsu & Lu, 2004; Van der Heijden, 2004; Yu et al., 2005). The popularity of mobile phones have captured the attention of researchers to test the applicability of TAM on mobile phones for various purposes from m-commerce (mobile commerce) such as shopping or banking to entertainment service (Luarn & Lin, 2005; Nysveen et al., 2005; Wu & Wang, 2005). Within the hedonic trend, interactive websites and visual attractiveness are important characteristics in empowering peo-ple to truly enjoy engaging in activities such as online games, web surfing, or simply browsing and shopping (e.g., Hsu & Lu, 2004; Lin & Lu, 2000; Nysveen et al., 2005; Saade & Bahli, 2005; Shang et al., 2005; Van der Heijden, 2004). Moreover, since vir-tual stores are regarded as an innovative business model compared to traditional brick-and-mortar retail stores, innovation related theories (e.g., Innovation Diffusion Theory (IDT), Perceived Charac-teristics of Innovating (PCI)) were also suggested to be incorporated into TAM (Chen, Gillenson, & Sherrell, 2002; Plouffe, Hulland, & Vandenbosch, 2001).

These trends are not mutually exclusive. Some documents may be involved with more than one factor. These documents are perceived to be useful in more than one specialty, revealing a cross-boundaries phenomenon (White, 1990). For example, the study ofVan der Heijden (2004)loaded on both factor 2 (e-commerce) and factor 3 (multi-purpose) with factor loadings of 0.43 and 0.76, respectively. It shows that online consumers are not solely utilitar-ian, emphasizing on efficient online shopping, but they also enjoyed the process of surfing and shopping online. This joyful perception often makes them to revisit the e-vendor’s website, and probably leads to additional shopping (Koufaris, 2002). In the same way, some task-related activities such as online learning are also con-nected to the hedonic nature (Lee et al., 2005; Saade & Bahli, 2005; Yi & Hwang, 2003). Therefore, the hedonic nature of an informa-tion system is an important boundary condiinforma-tion to the validity of the technology (Van der Heijden, 2004).

5.3. Limitations

There are some limitations which should be addressed. First, the co-citation method is flawed with a publication lag even though it claims to be a quantitative and objective statistical approach, because it is difficult for new papers to accumulate enough citations to enter the set of source documents. Even though we have reduced the threshold after 2005, some influential documents might not be included in our initial core set. Second, all citations are treated alike without considering the ranking or influence of source documents which implies some artificial limitations of the study (Acedo et al., 2006; Hicks, 1988; Nerur et al., 2007; Zitt & Bassecoulard, 1996). Finally, not all journals are included in the ISI Web of Knowledge database. For example, some of the major accounting journals are not included, such as Advances in Management Accounting, the Jour-nal of Management Accounting Research, Accounting and Business Research, etc. Likewise, some TAM papers are published in jour-nals which are not included in the ISI database, such as Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, Journal of Elec-tronic Commerce Research, or ElecElec-tronic Commerce Research. Even though our source documents are published in leading IS journals, future research might consider including some influential docu-ments from journals not included in ISI.

5.4. Conclusions

TAM has come to be one of the most widely used models for describing an individual’s acceptance of information systems. Though many studies including literature review and meta-analysis have tested the applicability and the convergence of TAM relationships across various contexts, TAM in our sense has never been used in co-citation analysis to study its intellectual struc-ture and identify current main trends.This study differs from other review studies in that it attempts to develop an intellectual map-ping of TAM based on co-citation analysis. We accomplished this study by identifying three main trends of TAM: task-related infor-mation systems, e-commerce inforinfor-mation systems, and hedonic information systems. In our great expectation, this study may serve as a benchmark for future research to investigate changes in the TAM field and to record the emergence of new research areas by incorporating more newly published papers over time.

Acknowledgements

Part of the work of the co-author Chyan Yang is sponsored by the NSC 96-2416-H-009-009-MY3.

References

Acedo, F. J., Barroso, C., & Galan, J. L. (2006). The resource-based theory: Dissemina-tion and main trends. Strategic Management Journal, 27(7), 621–636. Agarwal, R., & Prasad, J. (1999). Are individual differences germane to the acceptance

of new information technologies? Decision Sciences, 30(2), 361–391. Agarwal, R., & Venkatesh, V. (2002). Assessing a firm’s web presence: A

heuris-tic evaluation procedure for the measurement of usability. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 168–186.

Ahlgren, P., Jarneving, B., & Rousseau, R. (2003). Requirements for a cocitation simi-larity measure, with special reference to Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 54, 550–560.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Al-Gahtani, S. S., & King, M. (1999). Attitudes, satisfaction and usage: Factors con-tributing to each in the acceptance of information technology. Behaviour & Information Technology, 18(4), 277–297.

Amoako-Gyampah, K., & Salam, A. F. (2004). An extension of the technology acceptance model in an ERP implementation environment. Information & Man-agement, 41(6), 731–745.

Bagozzi, R. P., Davis, F. D., & Warshaw, P. R. (1992). Development and test of a theory of technological learning and usage. Human Relations, 45(7), 659–687. Bhattacherjee, A. (2001a). An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic

commerce service continuance. Decision Support Systems, 32(2), 201–214. Bhattacherjee, A. (2001b). Understanding information systems continuance: An

expectation-confirmation model. MIS Quarterly, 25(3), 351–370.

Borgman, C. L. (1989). Bibliometrics and scholarly communication: Editor’s intro-duction. Communication Research, 16(5), 583–599.

Briggs, R. O., De Vreede, G. J., & Nunamaker, J. F. (2003). Collaboration engineering with ThinkLets to pursue sustained success with group support systems. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 31–64.

Bruner, G. C., & Kumar, A. (2005). Explaining consumer acceptance of handheld internet devices. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 553–558.

Carter, L., & Belanger, F. (2005). The utilization of e-government services: Citizen trust, innovation and acceptance factors. Information Systems Journal, 15(1), 5–25.

Chau, P. Y. K. (1996). An empirical assessment of a modified technology acceptance model. Journal of Management Information Systems, 13(2), 185–204.

Chau, P. Y. K., & Hu, P. J. H. (2001). Information technology acceptance by individ-ual professionals: A model comparison approach. Decision Sciences, 32(4), 699– 719.

Chau, P. Y. K., & Hu, P. J. H. (2002). Investigating healthcare professionals’ decisions to accept telemedicine technology: An empirical test of competing theories. Information & Management, 39(4), 297–311.

Chen, L. D., Gillenson, M. L., & Sherrell, D. L. (2002). Enticing online consumers: An extended technology acceptance perspective. Information & Management, 39(8), 705–719.

Cheney, P. H., Mann, R. I., & Amoroso, D. L. (1986). Organizational factors affecting the success of end-user computing. Journal of Management Information Systems, 3(1), 65–80.

Chin, W. W., & Todd, P. A. (1995). On the use, usefulness, and ease of use of struc-turl equation modeling in MIS reeearch: A note of caution. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), 237–246.

Culnan, M. J. (1986). The intellectual development of management information sys-tems, 1972–1982: A co-citation analysis. Management Science, 156–172.

Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. Doctoral dissertation, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance

of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Davis, F. D., & Venkatesh, V. (1996). A critical assessment of potential measurement biases in the technology acceptance model: Three experiments. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 45(1), 19–45.

Davis, F., Bagozzi, R., & Warshaw, P. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. Devaraj, S., Fan, M., & Kohli, R. (2002). Antecedents of B2C channel satisfaction and preference: Validating e-commerce metrics. Information Systems Research, 13(3), 316–333.

Dishaw, M. T., & Strong, D. M. (1999). Extending the technology acceptance model with task-technology fit constructs. Information & Management, 36(1), 9–21. Doll, W. J., Hendrickson, A., & Deng, X. D. (1998). Using Davis’s perceived usefulness

and ease-of-use instruments for decision making: A confirmatory and multi-group invariance analysis. Decision Sciences, 29(4), 839–869.

Featherman, M. S., & Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 59(4), 451–474.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. MA: Addison-Wesley Reading.

Franklin, J. J., & Johnston, R. (1988). Co-citation bibliometric modeling as a tool for S&T policy and R&D management: Issues, applications, and developments. Handbook of Quantitative Studies of Science and Technology, 325–389. Garfield, E. (1979). Mapping the structure of science. Citation Indexing: Its Theory and

Applications in Science, Technology, and Humanities, 98–147.

Gefen, D., & Keil, M. (1998). The impact of developer responsiveness on perceptions of usefulness and ease of use: An extension of the technology acceptance model. ACM SIGMIS Database, 29(2), 35–49.

Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (1997). Gender differences in the perception and use of e-mail: An extension to the technology acceptance model. MIS Quarterly, 21(4), 389–400.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003a). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003b). Inexperience and experience with online stores: The importance of TAM and trust. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 50(3), 307–321.

Grandon, E. E., & Pearson, J. M. (2004). Electronic commerce adoption: An empirical study of small and medium US businesses. Information & Management, 42(1), 197–216.

Hackbarth, G., Grover, V., & Yi, M. Y. (2003). Computer playfulness and anxiety: Positive and negative mediators of the system experience effect on perceived ease of use. Information & Management, 40(3), 221–232.

Heinze, N., & Hu, Q. (2006). The evolution of corporate web presence: A longitu-dinal study of large American companies. International Journal of Information Management, 26(4), 313–325.

Hicks, D. (1988). Limitations and more limitations of co-citation analy-sis/bibliometric modelling: A reply to Franklin. Social Studies of Science, 18(2), 375–384.

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consump-tion: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140.

Hong, W. Y., Thong, J. Y. L., Wong, W. M., & Tam, K. Y. (2001). Determinants of user acceptance of digital libraries: An empirical examination of individual differ-ences and system characteristics. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(3), 97–124.

Hsu, C. L., & Lu, H. P. (2004). Why do people play on-line games? An extended TAM with social influences and flow experience. Information & Management, 41(7), 853–868.

Hu, P. J., Chau, P. Y. K., Sheng, O. R. L., & Tam, K. Y. (1999). Examining the technol-ogy acceptance model using physician acceptance of telemedicine technoltechnol-ogy. Journal of Management Information Systems, 16(2), 91–112.

Igbaria, M., & Iivari, J. (1995). Effects of self-efficacy on computer usage. Omega-International Journal of Management Science, 23(6), 587–605.

Igbaria, M., Zinatelli, N., Cragg, P., & Cavaye, A. L. M. (1997). Personal computing acceptance factors in small firms: A structural equation model. MIS Quarterly, 21(3), 279–305.

Jackson, C. M., Chow, S., & Leitch, R. A. (1997). Toward an understanding of the behavioral intention to use an information system. Decision Sciences, 28(2), 357–389.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Todd, P. A. (1997). Is there a future for retailing on the Internet? In Electronic marketing and the consumer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. (pp. 139–154).

Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (1999). The psychological origins of perceived useful-ness and ease-of-use. Information & Management, 35(4), 237–250.

Kerlinger, F. (1973). Foundations of behavioral research (2nd ed.). NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

King, W. R., & He, J. (2006). A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 43(6), 740–755.

Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 205–223.

Lai, V., & Li, H. (2005). Technology acceptance model for internet banking: An invari-ance analysis. Information & Management, 42(2), 373–386.

Lederer, A. L., Maupin, D. J., Sena, M. P., & Zhuang, Y. L. (2000). The technology acceptance model and the World Wide Web. Decision Support Systems, 29(3), 269–282.

Lee, M. K. O., Cheung, C. M. K., & Chen, Z. (2005). Acceptance of Internet-based learning medium: The role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Information & Management, 42(8), 1095–1104.

Legris, P., Ingham, J., & Collerette, P. (2003). Why do people use information tech-nology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 40(3), 191–204.

Leydesdorff, L., & Vaughan, L. (2006). Co-occurrence matrices and their applications in information science: Extending ACA to the web environment. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(12), 1616–1628. Lim, H., Lee, S. G., & Nam, K. (2007). Validating e-learning factors affecting training

effectiveness. International Journal of Information Management, 27(1), 22–35. Lin, A. (2006). The acceptance and use of a business-to-business information system.

International Journal of Information Management, 26(5), 386–400.

Lin, J. C. C., & Lu, H. P. (2000). Towards an understanding of the behavioural inten-tion to use a web site. Internainten-tional Journal of Informainten-tion Management, 20(3), 197–208.

Luarn, P., & Lin, H. H. (2005). Toward an understanding of the behavioral intention to use mobile banking. Computers in Human Behavior, 21(6), 873–891. Lucas, H. C., & Spitler, V. K. (1999). Technology use and performance: A field study

of broker workstations. Decision Sciences, 30, 291–312.

Mathieson, K., Peacock, E., & Chin, W. W. (2001). Extending the technology accep-tance model: The influence of perceived user resources. ACM SIGMIS Database, 32(3), 86–112.

McCain, K. W. (1990). Mapping authors in intellectual space: A technical overview. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 41(6), 433–443. McCain, K. W. (1991a). Mapping economics through the journal literature: An

experiment in journal cocitation analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(4), 290–296.

McCain, K. W. (1991b). Core journal networks and cocitation maps: New bibliometric tools for serials research and management. The Library Quarterly, 61(3), 311–336. McCain, K. W. (1999). Cocited author mapping as a valid representation of intel-lectual structure. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 37(3), 111–122.

Moon, J. W., & Kim, Y. G. (2001). Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web context. Information & Management, 38(4), 217–230.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Morris, M. G., & Dillon, A. (1997). How user perceptions influence software use. IEEE Software, 14(4), 58–65.

Nerur, S. P., Rasheed, A. A., & Natarajan, V. (2007). The intellectual structure of the strategic management field: An author co-citation analysis. Strategic Manage-ment Journal, 29(3), 319–336.

Novak, T. P., Hoffman, D. L., & Duhachek, A. (2003). The influence of goal-directed and experiential activities on online flow experiences. Journal of Consumer Psy-chology, 3–16.

Nysveen, H., Pedersen, P. E., & Thorbjornsen, H. (2005). Intentions to use mobile services: Antecedents and cross-service comparisons. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(3), 330–346.

Ong, C. S., Lai, J. Y., & Wang, Y. S. (2004). Factors affecting engineers’ acceptance of asynchronous e-learning systems in high-tech companies. Information & Man-agement, 41(6), 795–804.

Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 7(3), 101–134.

Pavlou, P. A., & Fygenson, M. (2006). Understanding and predicting electronic com-merce adoption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. MIS Quarterly, 30(1), 115–143.

Plouffe, C. R., Hulland, J. S., & Vandenbosch, M. (2001). Research report: Richness versus parsimony in modeling technology adoption decisions-understanding merchant adoption of a smart card-based payment system. Information Systems Research, 12(2), 208–222.

Price, D. J., & De Solla, D. E. (1965). Networks of scientific papers. Science, 149(3683), 510–515.

Ramos-Rodriguez, A. R., & Ruiz-Navarro, J. (2004). Changes in the intellectual structure of strategic management research: A bibliometric study of the Strate-gic Management Journal, 1980–2000. StrateStrate-gic Management Journal, 25(10), 981–1004.

Riemenschneider, C. K., Harrison, D. A., & Mykytyn, P. P. (2003). Understanding IT adoption decisions in small business: Integrating current theories. Information & Management, 40(4), 269–285.

Rowlands, I. (1999). Patterns of author cocitation in information policy: Evidence of social, collaborative and cognitive structure. Scientometrics, 44(3), 533–546. Saade, R., & Bahli, B. (2005). The impact of cognitive absorption on perceived

use-fulness and perceived ease of use in on-line learning: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 42(2), 317–327. Schepers, J., & Wetzels, M. (2007). A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance

model: Investigating subjective norm and moderation effects. Information & Management, 44(1), 90–103.

Shang, R. A., Chen, Y. C., & Shen, L. (2005). Extrinsic versus intrinsic motivations for consumers to shop on-line. Information & Management, 42(3), 401–413. Shih, H. P. (2004). An empirical study on predicting user acceptance of e-shopping

on the web. Information & Management, 41(3), 351–368.

Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the rela-tionship between two documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 24(4), 265–269.

Small, H. (2003). Paradigms, citations, and maps of science: A personal history. Jour-nal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(5), 394– 399.

Stewart, D. W., Pavlou, P., & Ward, S. (2002). Media influences on marketing com-munications. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 353–396. Straub, D., Keil, M., & Brenner, W. (1997). Testing the technology acceptance model

across cultures: A three country study. Information & Management, 33(1), 1–11. Straub, D., Limayem, M., & Karahanna, E. (1995). Measuring system usage –

Impli-cations for IS theory testing. Management Science, 41(8), 1328–1342. Sugimoto, C., Pratt, J., & Hauser, K. (2008). Using field co-citation analysis to assess

reciprocal and shared impact of LIS/MIS fields. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 59(9), 1441–1453.

Sullivan, D., Koester, D., White, D. H., & Kern, R. (1980). Understanding rapid the-oretical change in particle physics: A month-by-month co-citation analysis. Scientometrics, 2(4), 309–319.

Sun, H., & Zhang, P. (2006). The role of moderating factors in user technology accep-tance. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 64(2), 53–78. Sussman, S. W., & Siegal, W. S. (2003). Informational influence in organizations:

An integrated approach to knowledge adoption. Information Systems Research, 14(1), 47–65.

Szajna, B. (1996). Empirical evaluation of the revised technology acceptance model. Management Science, 42(1), 85–92.

Taylor, S., & Todd, P. (1995). Assessing IT usage: The role of prior experience. MIS Quarterly, 19(4), 561–570.

Taylor, S., & Todd, P. A. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6, 144–176.

Van der Heijden, H. (2003). Factors influencing the usage of websites: The case of a generic portal in The Netherlands. Information & Management, 40(6), 541–549. Van der Heijden, H. (2004). User acceptance of hedonic information systems. MIS

Quarterly, 28(4), 695–704.

Venkatesh, V. (1999). Creation of favorable user perceptions: Exploring the role of intrinsic motivation. MIS Quarterly, 23(2), 239–260.

Venkatesh, V. (2000). Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Infor-mation Systems Research, 11(4), 342–365.

Venkatesh, V., & Brown, S. A. (2001). A longitudinal investigation of personal comput-ers in homes: Adoption determinants and emerging challenges. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 71–102.

Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (1996). A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: Development and test. Decision Sciences, 27(3), 451–481.

Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204.

Venkatesh, V., & Morris, M. G. (2000). Why don’t men ever stop to ask for direc-tions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 115–139.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425– 478.

Venkatraman, M. P., & MacInnis, D. J. (1985). The epistemic and sensory exploratory behaviors of hedonic and cognitive consumers. Advances in Consumer Research, 12(1), 102–107.

Vijayasarathy, L. R. (2004). Predicting consumer intentions to use on-line shop-ping: The case for an augmented technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 41(6), 747–762.

White, H. D. (1990). Author co-citation analysis: Overview and defense. Scholarly Communication and Bibliometrics, 84–106.

White, H. D. (2003). Author cocitation analysis and Pearson’s r. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 54(13), 1250–1259.

White, H. D., & Griffith, C. (1981). Author cocitation: A literature measure of intel-lectual structure. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 32(3), 163–171.

White, H. D., & McCain, K. W. (1998). Visualizing a discipline: An author co-citation analysis of information science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 49(4), 327–355.

Wixom, B. H., & Todd, P. A. (2005). A theoretical integration of user satisfaction and technology acceptance. Information Systems Research, 16(1), 85–102. Wu, J. H., & Wang, S. C. (2005). What drives mobile commerce? An empirical

evalu-ation of the revised technology acceptance model. Informevalu-ation & Management, 42(5), 719–729.

Yi, M. Y., & Hwang, Y. J. (2003). Predicting the use of web-based information systems: Self-efficacy, enjoyment, learning goal orientation, and the technol-ogy acceptance model. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 59(4), 431–449.

Yiu, C. S., Grant, K., & Edgar, D. (2007). Factors affecting the adoption of internet banking in Hong Kong – Implications for the banking sector. International Journal of Information Management, 27(5), 336–351.

Yu, J., Ha, I., Choi, M., & Rho, J. (2005). Extending the TAM for a t-commerce. Infor-mation & Management, 42(7), 965–976.

Zitt, M., & Bassecoulard, E. (1996). Reassessment of co-citation methods for sci-ence indicators: Effect of methods improving recall rates. Scientometrics, 37(2), 223–244.