Risk Factors for Prostate Carcinoma in Taiwan

A Case–Control Study in a Chinese Population

John F. C. Sung,Ph.D.1,2 Ruey S. Lin,M.D.,Dr.P.H.3 Yeong-Shiau Pu,M.D.,Ph.D.4 Yi-Chun Chen,M.S.1 Hong C. Chang,M.D.4 Ming-Kuen Lai,M.D.4

1Institute of Environmental Health, National

Tai-wan University, Taipei, TaiTai-wan.

2Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. 3Institute of Epidemiology, National Taiwan

Uni-versity, Taipei, Taiwan.

4Department of Urology, College of Medicine,

Na-tional Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Presented in part at Prevention 99, Washington, DC, March 19 –20, 1999.

Supported by grant NSC1996-2331-002-248 from the National Science Council, Executive Yuan, Taipei ROC.

Address for reprints: John F.C. Sung, Ph.D., M.P.H., Professor, National Taiwan University Col-lege of Public Health, 1 Jen Ai Road Section 1, Taipei 100, Taiwan.

Received December 9, 1998; revision received March 8, 1999; accepted March 8, 1999.

BACKGROUND.Although prostate carcinoma remains a rare disease among Chinese men, its incidence is on the rise. The authors conducted a hospital-based case– control study to identify risk factors for prostate carcinoma in northern Taiwan.

METHODS.Patients at a selected veterans hospital or 2 military hospitals who were newly diagnosed with prostate carcinoma between August 1995 and July 1996 were included as cases (n5 90). Controls (n 5 180) were comprised noncancer patients who were treated in emergency rooms and departments other than those of urology and cardiology at the same hospitals; controls were matched to cases by age (65 years) and admission date (64 months). Subjects were interviewed in person to elicit information regarding sociodemographic characteristics, life-style, diet, height, and weight.

RESULTS. Cases and controls were similar in terms of age and the majority of sociodemographic characteristics. However, cases tended to have received more education and were less likely to have blue-collar jobs than controls. The con-sumption of pork was moderately higher for cases than for controls, although this difference was not statistically significant. Cases were more likely than controls to engage in exercise (odds ratio [OR]5 2.16; 95% confidence interval [CI] 5 1.18– 3.96) and to have a body mass index^ 24.75 kg/m2

at ages 40 – 45 years (OR5 2.00; 95%CI5 1.05–3.82). In addition, cases were less likely to cook vegetables with pork lard (OR5 0.47; 95%CI 5 0.24–0.91).

CONCLUSIONS. The higher frequency of exercise and lower use of pork lard for cooking among cases reported in the current study suggest that cases tended to have relatively affluent life-styles compared with controls. Because less affluent families are likely to consume more vegetables than meat, these preliminary findings indicate that vegetable intake appears to have a protective effect. Cancer 1999;86:484 –91. © 1999 American Cancer Society.

KEYWORDS: case-control study, Chinese, diet, prostate carcinoma, Taiwan.

T

he incidence of prostate carcinoma has increased steadily in the past decades to become the most frequently diagnosed cancer for men in the United States and in some other Western countries.1–3With an estimated 184,500 new cases and 39,200 deaths attributed to this cancer in 1998, it also has become the second leading cause of cancer-related death among men in the United States.1World wide, a

low rate of prostate carcinoma occurs among Asians.4This disease

accounted for only 2.2% of all cancer deaths in Taiwan4versus 14%

among American men1in 1995. Nevertheless, the mortality rates in

Taiwan have tripled within the past decade.4

High risk groups for prostate carcinoma have not been identified beyond age and racial segmentations. The incidence of the disease varies remarkably not only between ethnic groups but also within the same groups. For example, prostate carcinoma is the second most

frequently diagnosed malignancy among Chinese males in the United States, which represents an age-adjusted incidence'8 times higher than that among Chinese males in Taiwan.5–7 The disease is the most

frequently diagnosed form of cancer among African-Americans, whereas it is one of the least common forms among men in sub-Sahara Africa.5,6Thus,

fac-tors other than race appear to influence the incidence of prostate carcinoma in various ethnic populations.

The definitive etiology of this disease has not been established clearly, and there is no clear primary pre-vention strategy for it. Potential risk factors for the disease include environmental and life-style factors, such as diet, vitamin E, hormone levels, sexually trans-mitted diseases, viral infections, physical activity, chemical exposure, heredity, and sociodemographic status.8 –18 Studies suggest that dietary fat promotes

prostate tumorigenesis,9,10whereas long term vitamin

E supplementation reduces substantially the inci-dence of prostate carcinoma and mortality in male smokers.17

Although many etiologic studies on prostate car-cinoma have been reported, few epidemiologic inves-tigations have been conducted in low incidence pop-ulations, such as Asians.18 –20 To identify risk factors

among a low incidence population, we conducted a hospital-based case-control study in Taiwan. Dietary, life-style (including physical activity), and body weight were included as potential risk factors for prostate carcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The medical records of patients who were admitted between August 1995 and July 1996 to the urology departments of the largest veterans hospital and 2 military hospitals in the Taipei area were reviewed to identify newly diagnosed and histology confirmed prostate carcinoma cases. There were approximately 3000 beds in these hospitals, which serve as referral centers for primarily veterans and military men.

Controls were selected from patients who were hospitalized at the same hospitals at the same time for the treatment of unrelated diseases, including emer-gency care (32.1%), osteopathic department (23.5%), and eye care (11.7%), etc. An investigator reviewed the medical records of potential control subjects before recruitment. Patients in the departments of urology and cardiology and those with other malignancies, hormonal disorders, benign prostate diseases, lower urinary tract diseases, or cardiovascular diseases were excluded for controls but not for cases. Two controls were matched to each case by age (65 years), treat-ment hospital, and date of admission (64 months).

Data Collection

With the consent of the subjects, trained interviewers conducted personal interviews of all study cases and controls during hospitalization. The questionnaires covered sociodemographic characteristics, including age at diagnosis, ethnicity, education received, marital status, religion, occupation and income, chemical ex-posure, tobacco and alcohol use, diet, physical activ-ity, height, weight, medical history, the use of hor-mones, and family history of the disease. Patients who were very ill were not interviewed.

Dietary intake history prior to diagnosis was as-sessed by means of food frequency measures in the questionnaire. The questionnaire covered the most frequently consumed food groups, including meat, fish, shell fish, eggs, milk and other dairy products, vegetables, fruit, type of cooking oil or lard, and soy-bean products. Food consumption was reported as weekly or monthly frequency.

Physical activity also was determined by means of the frequency questionnaire technique. The inter-viewer asked a subject to recall the frequency of weekly exercise, the type and duration of each exer-cise, and the number of years of regular exercise. Exercise was classified as sedentary, light, moderate, or vigorous (in the patient’s opinion) with respect to the activity levels of the general population at similar ages. Other physical activities that were assessed in-cluded work or hobbies that required physical exer-tion, such as carpentry, gardening, or yard work, and other domestic chores.

Data Analysis

We first used frequency distributions to review the distributions of responses to the survey instrument. Because of the limited sample size, most potential risk factors eventually were divided into two levels and were dichotomized for odds ratio (OR) calculation.

To calculate the association between diet and prostate carcinoma risk, we measured the intake of each food item separately as well as the combined food intake frequencies. For data analysis, food items were classified according to common characteristics, resulting in categories such as pork, fish, chicken, beef, eggs, vegetables, fruit, and instant noodles. Data on each subject’s body weight at ages 20 –25 years and 40 – 45 years, 1 year before the diagnosis for cases, 1 year before the interview for controls, and the life-time heaviest weight were collected and converted into the body mass index (BMI; weight in kg divided by the square of height in meters). The BMI at ages 40 – 45 years was used in the data analysis to estimate the association of BMI with prostate carcinoma.

Informa-tion on exercise, the period 5–10 years prior to hospi-talization was used to represent physical activity.

The strength of associations between prostate car-cinoma and the variables was measured in terms of the OR and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using the conditional logistic regression model.21Significant

or potential risk factors identified with univariate con-ditional logistic regression were used as covariates in multivariate analyses with the use of SAS software (version 6.09 for Windows; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).21Hierarchic modeling was used to determine the

best predictor of risk factors for prostate carcinoma. However, education (%9 years vs. .9 years) was forced in the multivariable conditional logistic regres-sion as a factor to correct for socioeconomic status.

RESULTS

From the three study hospitals, 97 cases and 196 con-trols were identified, and interviews were completed for 90 cases (92.8%) and 180 controls (91.8%) during their hospitalization. The majority of cases were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the study groups. About half of the subjects were age$70 years, and 40% were veterans. There were no significant differences between cases and controls in any of these variables.

The results shown in Table 2 represent selected, dichotomized distributions of potential risk factors. The smoking rate was slightly higher ('6%) in cases than in controls. Only small percentages of cases

TABLE 1

Sociodemographic and Economic Characteristics of Cases and Controls

Characteristic Cases (n5 90) Controls (n5 180) P value No. % No. % Age (yrs) 50–59 4 4.4 7 3.9 — 60–69 34 37.8 68 37.8 — 70–79 44 48.9 82 45.6 — $80 8 8.9 23 12.8 0.60 Ethnicity South Mine 30 33.3 57 31.7 — Hakka 3 3.3 9 5.0 — Mainland 57 63.3 114 63.3 0.74 Education (yrs) #9 46 51.1 108 60.0 — .9 43 47.8 70 38.9 — Unknown 1 1.1 2 1.1 0.16 Spouse’s education #9, years 66 73.4 136 75.6 — .9 20 22.2 26 14.4 — Unknown 4 4.4 18 10.0 0.26 Married Yes 77 85.6 144 80.0 0.92 No 13 14.4 36 20.0 — Religion Buddhism/Taoism 50 55.5 99 55.0 — None 26 28.9 64 35.6 — Christian/Catholic 10 11.1 14 7.8 — Other/unknown 4 4.4 3 1.7 0.74 Occupation Veteran 37 41.1 69 38.3 — White collar 21 23.3 29 16.1 — Blue collar 31 34.4 82 45.6 — Unknown 1 1.2 0 0 0.27 Family income Low/moderate 80 88.9 169 93.9 — Higher 10 11.1 10 5.5 — Unknown 0 0 1 0.6 0.46

TABLE 2

Comparisons of Selected Risk Factors between Cases and Controls

Characteristic

Cases (n5 90) Controls (n5 180)

Crude odds ratio (95% CI) No. % No. % Domestic work Yes 17 18.9 21 11.7 1.84 (0.88–3.54) No 70 77.8 159 88.3 1.0 Unknown 3 3.3 0 — — Smoking Yes 41 45.6 72 40.0 1.28 (0.77–1.48) No 48 53.3 108 60.0 1.0 Unknown 1 1.1 0 — — Coffee Yes 4 4.4 7 3.9 1.15 (0.33–4.03) No 86 95.6 173 96.1 1.0 Alcohol Yes 72 80.0 151 83.9 0.77 (0.40–1.48) No 18 20.0 29 16.1 1.0 Tea Yes 34 37.8 64 35.6 1.1 (0.65–1.86) No 56 62.2 116 64.4 1.0 Milk Yes 29 32.2 58 32.2 1.0 No 61 67.8 122 67.8 1.0 Soybean milk Yes 12 13.3 25 13.9 0.95 (0.45–2.00) No 78 86.7 155 86.1 1.0 Unknown 1 1.1 2 1.1 — Pork Yes 52 57.8 86 47.8 1.50 (0.9–2.5) No 37 41.1 92 51.1 1.0 Unknown 1 1.1 2 1.1 — Fish.1 3 week Yes 67 74.4 131 72.8 1.09 (0.61–1.96) No 22 24.4 47 26.1 1.0 Unknown 1 1.1 2 1.1 — Chicken.1 3 week Yes 75 83.3 130 72.2 1.73 (0.9–3.31) No 15 16.7 45 25.0 1.0 Unknown 0 0 5 2.8 Beef.1 3 week Yes 19 21.1 29 16.1 1.36 (0.74–2.60) No 71 78.9 148 82.2 1.0 Unknown 0 0 3 1.7 Eggs.1/week Yes 75 83.3 157 87.2 0.70 (0.34–1.43) No 15 16.7 22 12.2 1.0 Unknown 0 0 1 0.6 Fruit 2–7/week Yes 74 82.2 144 80.0 1.16 (0.57–2.35) No 16 17.8 36 20.0 1.0 Unknown 0 0 1 0.6

Cooking with lard

Yes 22 24.4 77 42.7 0.43 (0.24–0.76) No 67 74.4 101 56.1 1.0 Unknown 1 1.1 2 1.1 Instant noodles Yes 27 30.0 79 43.9 0.56 (0.33–0.96) No 62 70.0 101 56.1 1.0

BMI (age 40–45 yrs)a

%24.75 72 80.0 114 63.3 2.32 (1.72–4.21) .24.75b 18 20.0 66 36.7 1.0 Exerciseb Yes 42 46.7 54 30.0 1.98 (1.17–3.34) No 48 53.3 122 67.8 1.0 Unknown 0 — 4 2.2 —

95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

aBody mass index (kg/m2). bFive to 10 years before the diagnosis.

(4.4%) and controls (3.9%) drank coffee, but large per-centages of cases and controls (80% vs. 84%) drank alcohol on social occasions. However, the data analy-ses showed no significant associations of prostate car-cinoma with the above-mentioned variables, with smoking, or with consumption of tea, milk, or soybean milk. Cases tended to consume more pork, fish, chicken, and beef than controls, but these differences were only moderate and were not statistically signifi-cant.

Table 2 also shows significant negative associa-tions of risk for prostate carcinoma with the use of pork lard for cooking, the consumption of instant noo-dles, and BMI at age 40 – 45 years and a significant positive association with exercise. Cases were less likely to consume vegetables stir-fried with pork fat (24.4% vs. 42.7%) or to eat instant noodles (30.0% vs. 43.9%). However, cases were more likely to engage in regular exercise 5–10 years prior to the current hospi-talization (46.7% vs. 30.0%). Cases had lower BMI lev-els than controls: 80.0% of cases and 63.3% of controls had a BMI% 24.75 kg/m2at ages 40 – 45 years.

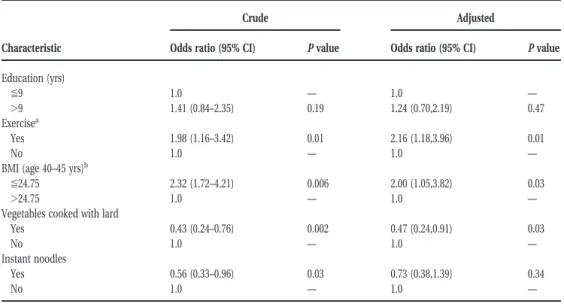

Table 3 shows that, after multivariable adjustment in a conditional logistic regression model, risk factors that remained significant for prostate carcinoma were active exercise (OR5 2.16; 95% CI 5 1.18–3.96) and a lower BMI (OR5 2.00; 95% CI 5 1.05–3.82) (Table 3). The use of pork fat for cooking vegetables conferred a significant negative association (OR5 0.47; 95% CI 5

0.24 – 0.91), whereas the consumption of instant noo-dles did not.

DISCUSSION

Cancer registry and population mortality data indicate that men in Taiwan have a very low incidence of prostate carcinoma.5,7 However, the changing,

age-adjusted incidences of the disease in this population— from 2.3 per 105men in 1985 to 7.2 per 105in 1995,

with mortality rates of 1.3 per 105 and 3.2 per 105,

respectively—reflect an increasing risk for men in Tai-wan.4,7,22 Potential factors contributing to the

in-creased incidence are those associated with socioeco-nomic development, including changes in life-styles, better diagnostic methods, and, in particular, increas-ing life expectancy. Prostate carcinoma occurs more frequently in those ages$70. Life expectancy for men in Taiwan in 1995 was 72.0 years, an increase of 19.0 years over the life expectancy of 53.0 years in 1945.4

More than half of our study cases were age$70 years at the time of diagnosis, a phenomenon consistent with other populations.1–3Several risk factors were not

assessed in this study: The effects of exposure to chemical and prescription hormones could not be analyzed because of insufficient exposure numbers; heredity influences could not be assessed because no family clusters were identified; and the influence of vasectomy could not be addressed because of the rarity of this procedure in Taiwan.

TABLE 3

Crude and Adjusted Odds Ratios for Patients with Prostate Carcinoma by Education, Exercise, Body Mass Index, Use Lard for Cooking, and Instant Noodle Consumption

Characteristic

Crude Adjusted

Odds ratio (95% CI) P value Odds ratio (95% CI) P value

Education (yrs) %9 1.0 — 1.0 — .9 1.41 (0.84–2.35) 0.19 1.24 (0.70,2.19) 0.47 Exercisea Yes 1.98 (1.16–3.42) 0.01 2.16 (1.18,3.96) 0.01 No 1.0 — 1.0 —

BMI (age 40–45 yrs)b

%24.75 2.32 (1.72–4.21) 0.006 2.00 (1.05,3.82) 0.03

.24.75 1.0 — 1.0 —

Vegetables cooked with lard

Yes 0.43 (0.24–0.76) 0.002 0.47 (0.24,0.91) 0.03

No 1.0 — 1.0 —

Instant noodles

Yes 0.56 (0.33–0.96) 0.03 0.73 (0.38,1.39) 0.34

No 1.0 — 1.0 —

95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

aFive to 10 years before diagnosis. bBody mass index (kg/m2).

Of the potential dietary risk factors for prostate carcinoma, fat intake has received the greatest atten-tion.9 –16,17–19,23 The low incidence of cancer among

Seventh-Day Adventist men, who consume less fat than the general population, suggests an increased risk with increased fat intake.24 However, results of

studies have been mixed. Economic development has been dramatic in Pacific Asian nations, including Tai-wan, in the last three decades, and this development has brought life-style changes. For example, the per capita daily intake of energy from fat in Taiwan was 63.5 grams in 1970 and 133.1 grams in 1990,25which is

equivalent to 32% per capita daily calorie consump-tion. This could explain in part the increased inci-dence of the disease in Taiwan. The findings of Gio-vannucci et al.10strongly suggested that dietary fat (in

particular, the fatty acid,a-linoleic acid, in red meat) increases the risk of prostate tumorigenesis by two- to three-fold. This association is particularly significant for men ages$70. Whittemore et al.11demonstrated

similar findings in a case-control study that included African-American, European-American, and Asian-American men. They found a significant association of prostate carcinoma risk with total saturated fat intake for all ethnic groups. In a study of prostate carcinoma among Asian-Americans, the risk increased indepen-dently as both the years of residence in North America and the fat intake increased; the odds ratio of in-creased fat intake for prostate carcinoma among Chi-nese-Americans, compared with controls with normal prostate specific antigen levels, was 4.5. It is possible that an increase in fat consumption among the Tai-wanese population may explain the increased inci-dence of the disease.

In contrast to the findings of Giovannucci et al.10

and Whittemore et al.,11 the current study seems to

demonstrate a moderate insignificant association be-tween patients with prostate carcinoma and the con-sumption of pork. The patients with prostate carci-noma in this study, however, were less likely than controls to use pork lard for cooking stir-fried vegeta-bles. For two reasons, this negative association may not conflict with the high fat diet hypothesis reported in many previous studies in Western countries: First, beef is not a major source of meat in Taiwan, because chicken, fish, and pork are consumed more widely. Second, cooking (stir-frying) with pork lard is a com-mon, traditional practice among families of lower so-cioeconomic status in Taiwan. Prior to Taiwan’s eco-nomic development, meat was consumed primarily during festival holidays rather than on a daily basis. Animal lard was used for stir-fry to compensate for the lack of meat in many families’ diets. Thus, it is likely that families that used pork lard for cooking also were

likely to consume less meat and more vegetables, which could explain the protective effect of pork lard found in this study. Another piece of supporting evi-dence that controls were less affluent than cases was that patients with prostate carcinoma exercised more than controls but were less likely to participate in domestic chores than controls. Controls also were more likely to consume instant noodles than cases, and this may be a surrogate measure of an association between a lack of affluence and a greater intake of carbohydrates and vegetables.

Giovannucci et al.26 also related dietary calcium

intake to an increased risk of prostate carcinoma and related fructose intake to a protective effect. Soy beans are rich in calcium. However, contradictory to their findings, the consumption of both soy bean milk and fruit was not different between cases and controls in the current study.

Snowdon et al.27 found in a cohort study that

overweight men were 2.5 times more likely than nor-mal weight men to develop prostate carcinoma. Our case-control study showed opposite results: Cases were two times as likely as controls to have a BMI of ,24.75 kg/m2than controls at ages 40 – 45 years. The

discrepancy in BMI between cases and controls be-came less apparent at later ages, indicating a possible association between gaining weight and the risk of prostate carcinoma. Among cases, the mean differ-ence between the weight at age 20 –25 years and the heaviest life-time weight was 6.6 kg, whereas that for controls was 4.6 kg.

In an earlier study conducted in Hawaii, Le Mar-chand et al.28compared life-time occupational

phys-ical activity between cases and controls and found a dose dependent, negative association among various ethnic groups. The current study, however, showed a contradictory result, in that men who engaged in ex-ercises were at a greater risk for the disease. In Taiwan, the elderly of affluent families are more likely than those of less affluent families to engage in exercise. Thus, it is likely that the association between exercise and prostate carcinoma in our study reflects a gener-ally more affluent life-style among cases, which may imply greater consumption of meat.

Heinonen et al.,17 in a recent study, found that

long term supplementation with vitamin E was asso-ciated substantially with incidence of prostate carci-noma and mortality in male smokers. Vitamin supple-mentation is not a common practice in the study subjects, and we were unable to measure its influence on prostate carcinoma risk.

Several limitations of this study must be consid-ered. First, the limitations inherent with such case-control studies are multiple comparisons with small

numbers of cases and controls and recall and report-ing bias. In our study, potential areas of recall bias included diet, weight, and exercise: Recall may have been affected by the subjects’ illness, particularly for those with advanced stage disease. We attempted to minimize this type of recall bias by not including very ill individuals. Second, studies in Western countries have revealed a bias from health-conscious adherents to low-fat diets and physical fitness, particularly among controls. It is likely that this bias did not affect strongly the responses in our study, because most of the study population would have been more con-cerned with sustenance during their younger years and with enjoyment of meals in later life rather than with the association of nutrition on health. It also is possible that our failure to find a significant associa-tion between meat consumpassocia-tion and prostate carci-noma risk was due to the small sample size rather than the absence of a real association. A third limitation was that, because most of the study subjects were selected from veterans administration or military medical centers, veterans represented .40% of the study subjects. Therefore, the results may not be gen-eralized to the general population in terms of occupa-tion, especially because these veterans had served in the military through harsh eras, including the World War II, the Chinese Civil Wars, and a period of relative economic hardship prior to the industrial develop-ment of Taiwan. The sociodemographic status and life-style of the veterans also make this study unique. Their diet, which consisted primarily of carbohydrates and vegetables, remained constant for 20 – 40 years until their retirement from the military. In fact, this type of diet was common before the 1980s for most people in Taiwan. Finally, the dietary questionnaire did not appear to be comprehensive enough and looked at general food groups rather than computing total nutrient intake. Thus, this study is unable to measure the risk association with total intake of nu-trients.

Previous studies10,11,29 have indicated that diet, especially fat, is the most important environmental risk factor contributing to variations in prostate carci-noma incidence among ethnic groups. Chinese in both Taiwan and the United States are from mainland China or are descended from Chinese immigrants. They may be homogeneous genetically, but the inci-dence of prostate carcinoma in Chinese in Taiwan is far below that of Chinese in America. Dietary fat, which comprises a higher proportion of the caloric intake in American than in Taiwanese meals, may be responsible for this difference. We speculate that the incidence of prostate carcinoma for men in Taiwan

will continue to increase as life-styles continue to change due to Taiwan’s economic development.

In conclusion, the observed negative association between the risk for prostate carcinoma and the use of pork fat for cooking vegetables, domestic manual la-bor, and instant noodle consumption may suggest that controls may have consumed more vegetables and less meat than cases. In other words, the risk for prostate carcinoma may be associated negatively with the intake of vegetables. Although these conclusions can be only tentative, data from relatively low inci-dence populations are of special interest.

REFERENCES

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures—1998. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 1998.

2. Kosary CL, Ries LAG, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Harras A, Ed-wards BK, editors. SEER cancer statistic review, 1973–1992: tables and graphs. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Insti-tute; 1995 NIH Pub. No. 96-2789.

3. Black RJ, Bray F, Ferlay J, Parkin DM. Cancer incidence and mortality in the European union: cancer registry data and estimates of national incidence for 1990. Eur J Cancer 1997; 33:1075–107.

4. Department of Health, Taiwan. Health and vital statistics, Republic of China, 1995. Taipei, Taiwan: Department of Health, 1995.

5. Haas GP, Sakr WA. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. CA

Cancer J Clin 1997;47:273– 87.

6. Parker SL, Davis KJ, Wingo PA, Ries LAG, Heath CW. Cancer statistics by race and ethnicity. CA Cancer J Clin 1998;48:31– 48.

7. Department of Health, Taiwan. Cancer registry annual re-ports, Republic of China, 1995. Taipei, Taiwan: Department of Health, 1998.

8. Ross RK, Schottenfeld D. Prostate cancer. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, Jr., editors. Cancer epidemiology and pre-vention, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996: 1180 –206.

9. Pienta KJ, Esper PS. Is dietary fat a risk factor for prostate cancer [editorial]? J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:1538 – 40. 10. Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio

A, Chute CC, et al. A prospective study of dietary fat and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:1571–9. 11. Whittemore AS, Kolonel LN, Wu AH, John EM, Gallagher RP,

Howe GR, et al. Prostate cancer relation to diet, physical activity, and body size in blacks, whites, and Asians in the United States and Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:652– 61.

12. Le Marchand L, Kolonel LN, Wilkens LR, Hirohata T, Meyers BC. Animal fat consumption and prostate cancer: a prospec-tive study in Hawaii. Epidemiology 1994;5:276 – 82. 13. Veierød MB, Laake P, Thelle DS. Dietary fat intake and risk

of prostate cancer: a prospective study of 25,708 Norwegian men. Int J Cancer 1997;73:634 – 8.

14. Willett WC. Specific fatty acids and risks of breast and pros-tate cancer: dietary intake. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66(Suppl): 1557– 63.

15. Zhou JR, Blackburn GL. Bridging animal and human studies: what are the missing segments in dietary fat and prostate cancer? Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66(Suppl):1572– 80.

16. Dwyer JT. Human studies on the effects of fatty acids on cancer: summary, gaps, and future research. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66(Suppl):1581– 6.

17. Heinonen OP, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Taylor PR, Huttunen JK, Hartman AM, et al. Prostate cancer and supplementation witha-tocopherol and b-carotene: incidence and mortality in a controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:440 – 6. 18. Kolonel LN, Yoshizawa CN, Hankin JH. Diet and prostate

cancer: a case-control study in Hawaii. Am J Epidemiol 1988;127:999 –1012.

19. Severson RK, Nomura AMY, Grove JS, Stemmermann GN. A prospective study of demographics, diet, and prostate can-cer among men of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii. Cancan-cer Res 1989;49:1857– 60.

20. Hsing AW, Devesa SS, Jin F, Gao YT. Rising incidence of prostate cancer in Shanghai, China [letter]. Cancer

Epide-miol Biomarkers Prev 1998;7:83– 4.

21. SAS Institute, Inc. SAS user’s guide: statistics. version 6.09. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc., 1990.

22. Chang CK, Yu HJ, Chan KW, Lai MK. Secular trend and age-period-cohort analysis of prostate cancer mortality in Taiwan. J Urol 1997;158:1845– 8.

23. Pienta KJ, Esper PS. Risk factors for prostate cancer. Ann

Internal Med 1993;118:793– 803.

24. Mills PK, Beeson WL, Phillips RL, Fraser GE. Cohort study of diet, lifestyle, and prostate cancer in Adventist men. Cancer 1989;64:598 – 604.

25. Council for Economic Planning and Development. Taiwan statistical data book, 1992. Taipei: Council for Economic Planning and Development, 1992:279.

26. Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Wolk A, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Calcium and fructose intake in relation to risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Res 1998;58:442–7.

27. Snowdon DA, Phillips PC, Choi W. Diet, obesity, and risk of fatal prostate cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1984;120:244 – 50.

28. Le Marchand L, Kolonel LN, Yoshizana CN. Lifetime occu-pational physical activity and prostate cancer risk. Am J

Epidemiol 1991;133:101–11.

29. Rose DP, Boyar AP, Wynder EL. International comparison of mortality rates for cancer of the breast, ovary, prostate, and colon, and per capita food consumption. Cancer 1986;58: 2363–71.