0095-1137/09/$08.00⫹0 doi:10.1128/JCM.00853-09

Copyright © 2009, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved.

Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Colonization by Methicillin-Resistant

Staphylococcus aureus among Adults in Community Settings in Taiwan

䌤

Jann-Tay Wang,

1Chun-Hsing Liao,

2Chi-Tai Fang,

1Wei-Chu Chie,

3Mei-Shu Lai,

3Tsai-Ling Lauderdale,

4Wen-Sen Lee,

5Jeng-Hua Huang,

6and Shan-Chwen Chang

1,7*

Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei 100, Taiwan

1; Department of Internal Medicine,

Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, Taipei County 220, Taiwan

2; Graduate Institute of Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health,

3and Graduate Institute of Clinical Pharmacy, College of Medicine,

7National Taiwan University, Taipei 100, Taiwan;

Division of Clinical Research, National Health Research Institute, Zhunan 350, Taiwan

4; Department of

Internal Medicine, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei 100, Taiwan

5; and Department of Internal Medicine,

Taipei Cathay General Hospital, Taipei 100, Taiwan

6Received 28 April 2009/Returned for modification 13 June 2009/Accepted 15 July 2009

In order to determine the prevalence of methicillin (meticillin)-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

colonization among adults in community settings in Taiwan and identify its risk factors, we conducted the

present study. For a 3-month period, we enrolled all adults who attended mandatory health examinations at

three medical centers and signed the informed consent. Nasal swabs were taken for the isolation of

S. aureus.

For each MRSA isolate, we performed multilocus sequence typing, identification of the staphylococcal cassette

chromosome

mec, tests for the presence of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin gene, and tests for drug

suscep-tibilities. Risk factors for MRSA colonization were determined. The results indicated that the MRSA

coloni-zation rate among adults in the community settings in Taiwan was 3.8% (119/3,098). Most MRSA isolates

belonged to sequence type 59 (84.0%). Independent risk factors for MRSA colonization included the presence

of household members less than 7 years old (

P < 0.0001) and the use of antibiotics within the past year (P ⴝ

0.0031). Smoking appeared to be protective against MRSA colonization (

P < 0.0001).

Before the late 1990s, nearly all methicillin

(meticillin)-re-sistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections occurred in

patients with specific risk factors who were in health care

facilities (31). However, the emergence of MRSA infections

among previously healthy persons in community settings

(with-out exposure to health care facilities) was noted thereafter (6,

31). Therefore, MRSA infections are now classified as

health care-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) infections and

community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) infections (38).

Strains responsible for CA-MRSA infections differ from

those for HA-MRSA infections in several phenotypic and

ge-netic features (1, 28). CA-MRSA strains carry type IV or V

staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) elements,

are usually Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) producing, and

are not multidrug resistant; HA-MRSA strains carry type I, II,

or III SCCmec elements, are usually not PVL producing, and

are multidrug resistant (15, 22, 28).

Initially, CA-MRSA infections were mostly reported in

young children (36). However, as CA-MRSA infections

be-came more common, infections were reported among people

of all ages and contributed to the increase of

community-associated S. aureus infections with significance (25, 29, 36).

MRSA colonization is an important risk factor for subsequent

MRSA infection (30), so several studies in the United States

have characterized the MRSA colonization rate in a

commu-nity setting (13, 16). These studies demonstrated that the nasal

colonization rates among healthy children increased from

0.8% in 2001 to 9.2% in 2004 (13). The colonization rate was

0.84% among people participating in the 2001 to 2002 National

Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (16).

In Taiwan, MRSA strains of sequence type 59 (ST59),

de-termined by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and carrying

type IV or V SCCmec elements, were recently found to be the

major strains of CA-MRSA (5, 7, 27). Other studies

demon-strated that these CA-MRSA strains were responsible for the

rapid increase in the number of CA-MRSA infections among

children and adults in Taiwan (7, 37). The MRSA colonization

rates among Taiwanese children increased from 1.5% from

2001 to 2002 to 7.2% from 2005 to 2006 (18, 19). However, the

MRSA colonization rate among adults in community settings

in Taiwan is unclear. This study was conducted to determine

the prevalence and risk factors for the colonization of MRSA

among adults in community settings in Taiwan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population. From 1 October 2007 to 31 December 2007, all adults (ages, ⬎18 years) who attended mandatory health examinations (as a part of the workplace health promotion program) at three medical centers located in north-ern Taiwan and signed the informed consent were enrolled in this study. Three well-trained study assistants took a nasal swab from each enrolled person. The swabs were sent to the central laboratory located at National Taiwan University Hospital (a major teaching hospital in Taiwan with a total capacity of 2,200 beds) and were cultured within 6 h. When an enrolled person was found to be a MRSA carrier, his or her household members were invited to participate in the study. After the informed consent was signed, nasal swabs from these household mem-bers were also taken and sent to be cultured. This study has been approved by the institute review boards of the three medical centers.

Bacterial culture and identification of MRSA. Each swab was plated onto a sheep blood agar plate. All plates were incubated at 35°C ambient air for 48 h. Isolates suspected of being S. aureus from sheep blood agar were first checked by

* Corresponding author. Mailing address: Department of Internal

Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, No. 7 Chung-Shan

South Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan. Phone: 886-2-23123456, ext. 5401.

Fax: 886-2-23958721. E-mail: changsc@ntu.edu.tw.

䌤

Published ahead of print on 22 July 2009.

catalase and Gram stain if deemed necessary, and all S. aureus isolates were confirmed by coagulase latex agglutination. S. aureus isolates were spotted onto ChromAgar MRSA to check for methicillin resistance. All isolates were pre-served.

Drug susceptibility tests. The MICs of all MRSA isolates were determined for gentamicin, clindamycin, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, minocycline, rifampin (ri-fampicin), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and vancomycin using the agar dilu-tion method proposed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (10). In brief, a Steers’ replicator was used to apply 104CFU of bacteria onto Mueller-Hinton agar containing serial twofold dilutions of each antimicrobial agent (256 to 0.03 mg/liter). The agar plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 h before reading. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antimicro-bial agents completely inhibiting the growth of bacteria. S. aureus ATCC 25923 was used as the internal control in each run of the test. The breakpoints used to determine susceptibility were as defined by the CLSI (11).

Molecular typing and detection of the PVL gene. Chromosomal DNA was prepared as described previously (17). The presence of the PVL gene lukF-lukS was determined by PCR with the use of a primer as described elsewhere (26). Typing of the SCCmec elements (I to V) and the mecA gene was performed by methods described by Ito et al. (22, 23). MLST was performed as described by Enright et al. (14).

Data collection. A standardized questionnaire was used to collect information on the risk factors for CA-MRSA colonization. The data collected were age; sex; educational degree; marital status; whether the subject was living in a dormitory or not; the number of household members; the presence of any household member who was a health care worker; the presence of any household member who was less than 7 years old; the presence of any household member who was bedridden; the presence of chronic diseases; smoking habits; hospitalizations within the previous year; a history of caring for inpatients within the past year; outpatient clinic visits within the past year; the use of antibiotics within the previous year; tattoos, acupuncture treatments, parenteral drug use, and/or di-alysis treatments within the previous year; a history of skin and soft-tissue infection within the previous year; whether the subject takes a shower every day; a history of visiting public places (e.g., hot-spring baths, swimming pools, sauna baths, gymnasiums, and dancing saloons) within the previous year; and economic status.

Statistics. Continuous variables were given as means⫾ standard deviations and compared using Student’s t test. The categorical variables were compared with a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test if the expected values were below 5. The prevalence of MRSA colonization was determined. To analyze the risk factors for carrying MRSA, we used polytomous logistic regression to compare people with MRSA to those without S. aureus and people with MRSA to those with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA). All parameters were initially tested by univariate analysis; those with a P value of⬍0.05 and those being biologically meaningful were used for the multivariate analysis. However, pa-rameters with colinearity, tested by correlation matrices, were not simultaneously considered in the final model. In the multivariate analysis, stepwise model com-parison was used to determine the best model. Statistical analyses were per-formed using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All tests were two-tailed, and a P value of⬍0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

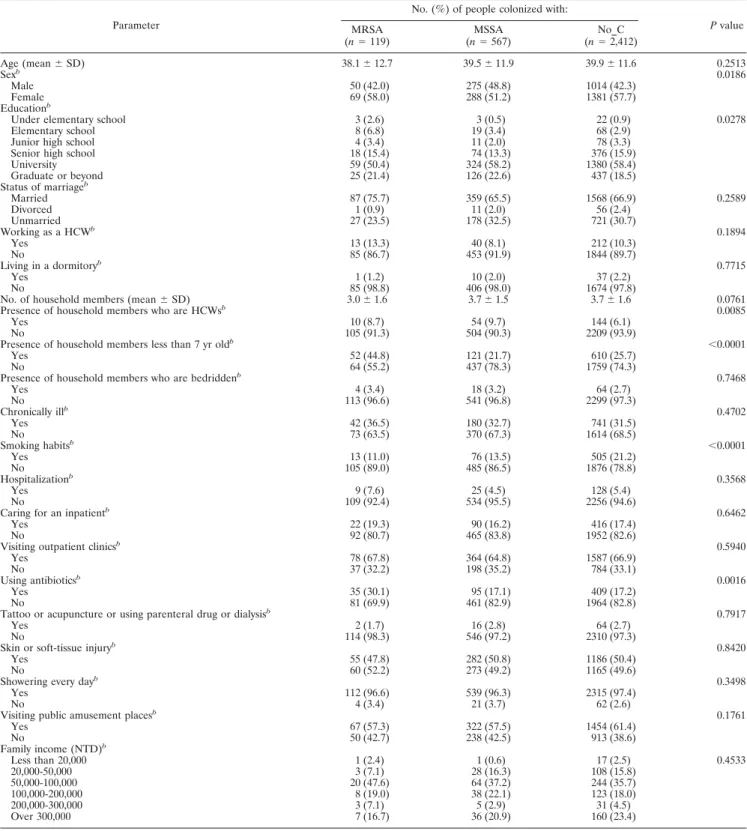

During the 3-month study period, there were 3,098 people

enrolled. Among them, 686 people were found to carry S.

aureus. A total of 119 of these 686 people carried MRSA and

567 had MSSA. The comparisons of demographics and other

parameters of the enrolled people are shown in Table 1. There

were statistically significant differences between these three

groups in the parameters of sex, educational degree, the

pres-ence of any household member who was a health care worker,

the presence of any household member less than 7 years old,

smoking habits, and the use of antibiotics within the past year.

Based on a post-hoc analysis, we found that people with

MRSA (i) tended to have less education than those with MSSA

or without S. aureus colonization (P

⫽ 0.0875 and 0.0650,

respectively), (ii) were more likely to have household members

who were less than 7 years old than the other two groups (both

P

⬍ 0.0001), (iii) were less likely to be smokers than those

without S. aureus colonization (P

⫽ 0.0077), and (iv) were

more likely to have used antibiotics during the past year than

the two other groups (P

⫽ 0.0012 and 0.0004, respectively).

Among the 119 MRSA isolates from the 119 people

(hence-forth the “index people”), 100 were classified as ST59, 11 as

ST508, 5 as ST89, 2 as ST239, and 1 as ST6. Of the 100 isolates

of ST59, 65 carried the type IV SCCmec element (ST59-IV)

and 35 carried the type V SCCmec element (ST59-V). Of the

65 ST59-IV MRSA isolates, only 10 (15.4%) were positive for

the PVL gene. All 35 of the ST59-V isolates were positive for

the PVL gene. All isolates of ST6 and ST508 carried the type

IV SCCmec element, all isolates of ST89 carried the type II

SCCmec element, and both isolates of ST239 carried the type

III SCCmec element (Table 2). All isolates, except two of

ST508, that belonged to ST6, ST89, ST239, and ST508 were

negative for the PVL gene. The overall prevalence of MRSA

was 3.8% (119/3,098; 95% confidence interval, 3.1% to 4.5%).

However, when those isolates carrying type IV and V SCCmec

elements were taken into consideration as CA-MRSA strains,

the prevalence of CA-MRSA carriage among healthy adults in

Taiwan was found to be 3.6% (112/3,098; 95% confidence

interval, 2.9% to 4.3%).

We also screened household members of 70 of the 119 index

people. In total, there were 242 household members screened.

Among these 242 people, 64 people (47 adults and 17 children)

from 39 families carried MRSA. Of these 64 MRSA isolates,

47 were classified as ST59, 11 as ST508, 2 as ST30, 2 as ST89,

1 as ST182, and 1 as ST342. Of the 47 isolates of ST59, 31

carried the type IV SCCmec element and the other 16 carried

the type V SCCmec element. Of the 31 ST59-IV MRSA

iso-lates from household members, 11 (35.5%) were positive for

the PVL gene. All 16 ST59-V isolates from household

mem-bers were positive for the PVL gene. All isolates of ST30,

ST182, ST342, and ST508 carried the type IV SCCmec

ele-ment, and both isolates of ST89 carried the type II SCCmec

element (Table 2). Of the 11 ST508-IV MRSA isolates from

household members, one (9.1%) was positive for the PVL

gene. All isolates of ST30 and ST182 were positive for the PVL

gene. None of the ST89 and ST342 isolates was positive for the

PVL gene.

A comparison of genotypes of the MRSA isolates from

household members and their associated index people

indi-cated that there were 16 (41.0%) families in which the MRSA

isolates from all household members and index people

be-longed to the same genotypes (same results from MLST

typ-ing, same SCCmec element, and identical presence/absence of

the PVL gene). There were six (15.4%) families in which

MRSA isolates from some (but not all) household members

were of the same genotypes as those of the index people. There

were five (12.8%) families in which MRSA isolates from

household members were of the same MLST type and the

same types of SCCmec elements as those of the index people

but different in the presence/absence of the PVL gene. There

were four (10.3%) families in which MRSA isolates from

household members were of the same MLST type as those of

the index people but different in the types of SCCmec elements

(despite the presence/absence of the PVL gene). And there

were eight (20.5%) families in which MRSA isolates from

household members differed from those of the index people in

MLST type.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of people with MRSA, MSSA, and no S. aureus colonization (n

⫽ 3,098)

aParameter

No. (%) of people colonized with:

P value MRSA (n⫽ 119) (nMSSA⫽ 567) (nNo_C⫽ 2,412) Age (mean⫾ SD) 38.1⫾ 12.7 39.5⫾ 11.9 39.9⫾ 11.6 0.2513 Sexb 0.0186 Male 50 (42.0) 275 (48.8) 1014 (42.3) Female 69 (58.0) 288 (51.2) 1381 (57.7) Educationb

Under elementary school 3 (2.6) 3 (0.5) 22 (0.9) 0.0278

Elementary school 8 (6.8) 19 (3.4) 68 (2.9)

Junior high school 4 (3.4) 11 (2.0) 78 (3.3)

Senior high school 18 (15.4) 74 (13.3) 376 (15.9)

University 59 (50.4) 324 (58.2) 1380 (58.4) Graduate or beyond 25 (21.4) 126 (22.6) 437 (18.5) Status of marriageb Married 87 (75.7) 359 (65.5) 1568 (66.9) 0.2589 Divorced 1 (0.9) 11 (2.0) 56 (2.4) Unmarried 27 (23.5) 178 (32.5) 721 (30.7) Working as a HCWb 0.1894 Yes 13 (13.3) 40 (8.1) 212 (10.3) No 85 (86.7) 453 (91.9) 1844 (89.7) Living in a dormitoryb 0.7715 Yes 1 (1.2) 10 (2.0) 37 (2.2) No 85 (98.8) 406 (98.0) 1674 (97.8)

No. of household members (mean⫾ SD) 3.0⫾ 1.6 3.7⫾ 1.5 3.7⫾ 1.6 0.0761

Presence of household members who are HCWsb 0.0085

Yes 10 (8.7) 54 (9.7) 144 (6.1)

No 105 (91.3) 504 (90.3) 2209 (93.9)

Presence of household members less than 7 yr oldb ⬍0.0001

Yes 52 (44.8) 121 (21.7) 610 (25.7)

No 64 (55.2) 437 (78.3) 1759 (74.3)

Presence of household members who are bedriddenb 0.7468

Yes 4 (3.4) 18 (3.2) 64 (2.7) No 113 (96.6) 541 (96.8) 2299 (97.3) Chronically illb 0.4702 Yes 42 (36.5) 180 (32.7) 741 (31.5) No 73 (63.5) 370 (67.3) 1614 (68.5) Smoking habitsb ⬍0.0001 Yes 13 (11.0) 76 (13.5) 505 (21.2) No 105 (89.0) 485 (86.5) 1876 (78.8) Hospitalizationb 0.3568 Yes 9 (7.6) 25 (4.5) 128 (5.4) No 109 (92.4) 534 (95.5) 2256 (94.6)

Caring for an inpatientb 0.6462

Yes 22 (19.3) 90 (16.2) 416 (17.4)

No 92 (80.7) 465 (83.8) 1952 (82.6)

Visiting outpatient clinicsb 0.5940

Yes 78 (67.8) 364 (64.8) 1587 (66.9)

No 37 (32.2) 198 (35.2) 784 (33.1)

Using antibioticsb 0.0016

Yes 35 (30.1) 95 (17.1) 409 (17.2)

No 81 (69.9) 461 (82.9) 1964 (82.8)

Tattoo or acupuncture or using parenteral drug or dialysisb 0.7917

Yes 2 (1.7) 16 (2.8) 64 (2.7)

No 114 (98.3) 546 (97.2) 2310 (97.3)

Skin or soft-tissue injuryb 0.8420

Yes 55 (47.8) 282 (50.8) 1186 (50.4)

No 60 (52.2) 273 (49.2) 1165 (49.6)

Showering every dayb 0.3498

Yes 112 (96.6) 539 (96.3) 2315 (97.4)

No 4 (3.4) 21 (3.7) 62 (2.6)

Visiting public amusement placesb 0.1761

Yes 67 (57.3) 322 (57.5) 1454 (61.4) No 50 (42.7) 238 (42.5) 913 (38.6) Family income (NTD)b Less than 20,000 1 (2.4) 1 (0.6) 17 (2.5) 0.4533 20,000-50,000 3 (7.1) 28 (16.3) 108 (15.8) 50,000-100,000 20 (47.6) 64 (37.2) 244 (35.7) 100,000-200,000 8 (19.0) 38 (22.1) 123 (18.0) 200,000-300,000 3 (7.1) 5 (2.9) 31 (4.5) Over 300,000 7 (16.7) 36 (20.9) 160 (23.4)

aNo_C, no S. aureus colonization; SD, standard deviation; M, male; F, female; HCWs, health care workers; NTD, new Taiwan dollar.

bThere are missing data for some parameters, including the sex category (21 people), education (63), working as a HCW (95), living in a dormitory (885),

presence of household members who are HCWs (72), presence of household members under 7 years old (55), presence of household members who are bedridden (59), chronically ill (78), smoking habits (38), hospitalization (37), caring for inpatients (61), visiting outpatient clinics (50), using antibiotics (53), tattoo or acupuncture or using parenteral drug or dialysis (48), skin or soft-tissue injury (77), showering every day (47), visiting public amusement places (54), and family income (2,201).

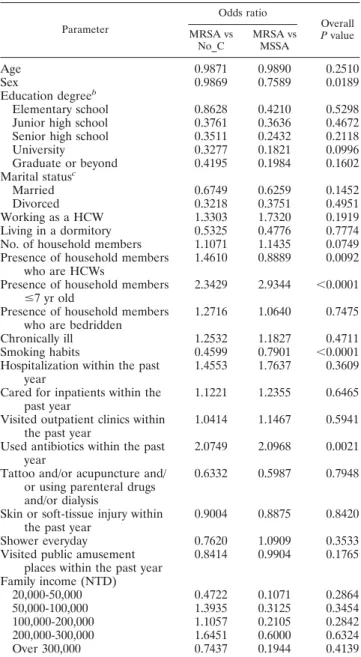

We used polytomous logistic regression to identify risk

fac-tors for MRSA colonization by comparing people with MRSA

to those with MSSA and people with MRSA to those without

carriage of S. aureus. Univariate analysis indicated that the

female gender, the presence of health care workers in the

household, the presence of household members less than 7

years old, being a nonsmoker, and the use of antibiotics during

the past year were risk factors for MRSA colonization (Table

3). Using a multivariate analysis, the presence of household

members less than 7 years old, being a nonsmoker, and the use

of antibiotics during the past year were independent risk

fac-tors for MRSA colonization compared to those without

car-riage of S. aureus. However, the presence of household members

less than 7 years old and the use of antibiotics during the past year

were the only two independent risk factors for MRSA

coloniza-tion compared to those for carriage of MSSA (Table 4).

Table 5 shows the drug susceptibilities of all 183 MRSA

isolates (from the index people and their families) stratified by

MLST types. The overall susceptibilities were 25.1% for

clin-damycin, 16.9% for erythromycin, 99.5% for

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 78.1% for gentamicin, 99.5% for

minocy-cline, 98.9% for ciprofloxacin, 100% for rifampin, and 100%

for vancomycin.

DISCUSSION

Several reports from the United States indicated that

com-munity-associated S. aureus infections have increased rapidly

in recent years and that MRSA (not MSSA) accounts for most

of this increase (24, 29). Studies from Taiwan have

demon-strated similar findings among children and adults (7, 37).

Therefore, it is increasingly important to characterize the

MRSA colonization pool among people in communities. The

prevalence of MRSA colonization among children in

commu-nities has been extensively studied in Taiwan and the United

States (5, 13, 18, 19, 21, 32–34), but there are only a few studies

of MRSA colonization among adults in communities (16, 39).

Our study showed that the MRSA colonization rate among

adults in community settings in Taiwan who attended

manda-tory health examinations as a part of workplace health

promo-tion was 3.8% (95% confidence interval, 3.1% to 4.5%).

A previous population-based study showed that the MRSA

colonization rate among people attending the 2001 to 2002

NHANES was 0.84% (16). A study in The Netherlands from

1999 to 2000 indicated that the MRSA colonization rate

among the general Dutch population was 0.03% (39). The

MRSA colonization rate in this study was about 5- to 10-fold

higher than reported in these prior studies. There may be

several reasons for this difference. First, the colonization by

MRSA among adults in communities may be more prevalent in

Taiwan than in the United States and The Netherlands.

Sec-ond, our study was conducted 5 to 7 years after those studies,

so the difference may be due to an overall increase of MRSA

TABLE 2. MLST types and SCCmec elements in the 183 MRSA

isolates (119 index people and 64 household members)

MLST type

No. of isolates for indicated type of SCCmec element

Index people Household members

II III IV V Subtotal II III IV V Subtotal

ST6

0

0

1

0

1

0

ST30

0

0

0

2

0

2

ST59

0

0

65

35

100

0

0

31

16

47

ST89

5

0

0

0

5

2

0

0

0

2

ST182

0

0

0

1

0

1

ST239

0

2

0

0

2

0

ST342

0

0

0

1

0

1

ST508

0

0

11

0

11

0

0

11

0

11

Total

5

2

77

35

119

2

0

46

16

64

TABLE 3. Risk factors for people colonized with MRSA compared

to those colonized with MSSA and those not colonized with

S. aureus by univariate analysis using polytomous

logistic regression

a Parameter Odds ratio Overall P value MRSA vs No_C MRSA vs MSSAAge

0.9871

0.9890

0.2510

Sex

0.9869

0.7589

0.0189

Education degree

bElementary school

0.8628

0.4210

0.5298

Junior high school

0.3761

0.3636

0.4672

Senior high school

0.3511

0.2432

0.2118

University

0.3277

0.1821

0.0996

Graduate or beyond

0.4195

0.1984

0.1602

Marital status

cMarried

0.6749

0.6259

0.1452

Divorced

0.3218

0.3751

0.4951

Working as a HCW

1.3303

1.7320

0.1919

Living in a dormitory

0.5325

0.4776

0.7774

No. of household members

1.1071

1.1435

0.0749

Presence of household members

who are HCWs

1.4610

0.8889

0.0092

Presence of household members

ⱕ7 yr old

2.3429

2.9344

⬍0.0001

Presence of household members

who are bedridden

1.2716

1.0640

0.7475

Chronically ill

1.2532

1.1827

0.4711

Smoking habits

0.4599

0.7901

⬍0.0001

Hospitalization within the past

year

1.4553

1.7637

0.3609

Cared for inpatients within the

past year

1.1221

1.2355

0.6465

Visited outpatient clinics within

the past year

1.0414

1.1467

0.5941

Used antibiotics within the past

year

2.0749

2.0968

0.0021

Tattoo and/or acupuncture and/

or using parenteral drugs

and/or dialysis

0.6332

0.5987

0.7948

Skin or soft-tissue injury within

the past year

0.9004

0.8875

0.8420

Shower everyday

0.7620

1.0909

0.3533

Visited public amusement

places within the past year

0.8414

0.9904

0.1765

Family income (NTD)

20,000-50,000

0.4722

0.1071

0.2864

50,000-100,000

1.3935

0.3125

0.3454

100,000-200,000

1.1057

0.2105

0.2842

200,000-300,000

1.6451

0.6000

0.6324

Over 300,000

0.7437

0.1944

0.4139

aNo_C, no S. aureus colonization; HCWs, health care workers; NTD, new

Taiwan dollar.

bUsing the under-elementary-school category result as the baseline. cUsing the unmarried category result as the baseline.

during this time. Several previous studies have demonstrated

that the MRSA colonization rate of people in communities has

increased over time (5, 13). However, we also understand that

only adults who attended mandatory health examinations as a

part of a workplace health promotion program were enrolled

in our study and thus may not be representative of the adult

populations in communities. Since these attendees are

presum-ably healthier than average, our results may be biased by the

healthy worker effect (2).

Our molecular analysis indicated that most of the MRSA

isolates (112/119) from the index people carried the type IV or

type V SCCmec element, as is typical for CA-MRSA strains

(15, 22, 23, 28). Therefore, the colonization rate of CA-MRSA

strains was 3.6% in this study. In this study, ST59 isolates were

the most common MLST type of isolates. Previous studies

from Taiwan have found that ST59 MRSA isolates were the

most common MLST type of MRSA causing CA-MRSA

in-fections in different geographic areas all over Taiwan (8).

Stud-ies concerning the MRSA colonization in Taiwanese children

also found ST59 is the predominant type among MRSA

iso-lates from child carriers in communities all over Taiwan (7, 18).

Our study adds additional information about the MRSA

car-rier rate and bacterial typing in adults in community settings in

Taiwan. However, ST59 MRSA isolates were rarely found in

other Asian countries according to the findings from a recent

large-scale study (9).

Our molecular analysis that compared MRSA isolates from

the index people and their associated households identified

numerous instances where the genotypes were different. This

strongly suggests that, in addition to household transmission

(20), the spread of MRSA in community settings occurred via

some other routes, such as sport contact, the use of saunas,

exposure to a colonized animal, and so on (3, 4, 12, 40).

We used polytomous logistic regression to identify risk

fac-tors for MRSA colonization by comparing people with MRSA

colonization to those with MSSA colonization and people with

MRSA colonization to those without carriage of S. aureus at

the same time. This allowed us to avoid problems associated

with multiple intergroup comparisons. Studies that reported

the determinants of MRSA colonization in community settings

remained limited (16). Our multivariate analysis indicated that

the presence of household members less than 7 years old, being

a nonsmoker, and the use of antibiotics within the past year

were the independent risk factors for MRSA colonization

com-pared to those without S. aureus colonization. The presence of

household members less than 7 years old and the use of

anti-biotics within the past year were the only two independent risk

factors for MRSA colonization compared to those for MSSA

colonization.

A previous study showed that the MRSA colonization rate

of children in community settings in Taiwan was 7.2% from

2005 to 2006 (18), much higher than the adult colonization rate

(3.8%) in the present study. In addition, among our 17

pedi-atric household members who had MRSA, 12 carried MRSA

of the same genotype as the associated index person. The

hypothesis that transmission from children to their parents

through close household contact might play an important role

in MRSA colonization among adults is worthy of further study.

We also found that the use of antibiotics was associated with

the presence of MRSA. This was expected, because antibiotics

provide selective pressure and thus facilitated the colonization

of drug-resistant pathogens such as MRSA.

TABLE 4. Risk factors for MRSA colonization compared to MSSA colonization and no S. aureus colonization by multivariate analysis using

polytomous logistic regression

Risk factor

MRSA vs No_Ca MRSA vs MSSA

P value of overall model Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) P value of coefficient Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) P value of coefficient

Presence of household members

aged under 7

2.2387 (1.5255–3.2853)

⬍0.0001

2.9110 (1.9048–4.4488)

⬍0.0001

⬍0.0001

Smoking habits

0.4419 (0.2383–0.8195)

0.0096

0.9582 (0.4946–1.8563)

0.8994

⬍0.0001

Using antibiotics within the past year

2.0530 (1.3544–3.1118)

0.0007

2.0322 (1.2826–3.2198)

0.0025

0.0031

aNo_C, no S. aureus colonization.

TABLE 5. Drug susceptibilities of the 183 MRSA isolates with stratification by MLST type

MLST type (no. of isolates)

% Susceptibility for indicated druga

CM ERM TXT GM MIN CIP RIF VAN

ST6 (1)

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

ST30 (2)

50

50

100

100

100

100

100

100

ST59 (147)

14.3

11.6

99.3

74.1

99.3

100

100

100

ST89 (7)

0

0

100

100

100

85.7

100

100

ST182 (1)

100

0

100

100

100

100

100

100

ST239 (2)

50

0

100

50

100

50

100

100

ST342 (1)

100

0

100

100

100

100

100

100

ST508 (22)

90.9

54.5

100

95.4

100

100

100

100

Overall (183)

25.1

16.9

99.5

78.1

99.5

98.9

100

100

aCM, clindamycin; ERM, erythromycin; TXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; GM, gentamicin; MIN, minocycline; CIP, ciprofloxacin; RIF, rifampin; VAN,

Surprisingly, in a comparison of people with MRSA and

those without S. aureus colonization, we found that smoking

was a protective factor against MRSA colonization. However,

a comparison of people with MRSA and those with MSSA

found that smoking was not such a factor. In reanalyzing our

data, we found that smoking was also an independent

protec-tive factor against MSSA and S. aureus (pooling MRSA and

MSSA together) colonization compared to those without S.

aureus colonization (odds ratio, 0.4612 and 0.4570,

respec-tively; 95% confidence interval, 0.3480 to 0.6111 and 0.3520 to

0.5940, respectively; P

⬍ 0.0001 and 0.0001, respectively).

Therefore, it seems that smoking is a protective factor against

S. aureus, not only specifically against MRSA, colonization. To

our best knowledge, only a review article described the similar

findings based on the results from a Ph.D. thesis (35). Our

study therefore provides the important evidence that smoking

might be a protective factor against the nasal colonization of S.

aureus. It might be that smoking creates a microenvironment in

the nose that protects against the growth of S. aureus. Clearly,

the effect of smoking on S. aureus colonization requires further

study.

The results of our drug susceptibility tests showed that more

than 95% of the isolates were susceptible to

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and ciprofloxacin; that all

iso-lates were susceptible to rifampin and vancomycin; and that

most isolates were resistant to clindamycin and erythromycin.

These results differ from those reported from the United

States, where the rate of susceptibility to clindamycin of

MRSA isolates causing CA-MRSA infection was as high as

95% (29). This may be due to the predominance of different

strains in these different geographic regions.

In conclusion, the present study showed that the rate is

3.8%. Most (94.1%) of these MRSA isolates in the present

study had typical characteristics of CA-MRSA. Our study also

identifies that the presence of household members less than 7

years old as well as the use of antibiotics within the past year

were the independent risk factors for MRSA colonization, and

smoking appeared to be a protective factor against MRSA

colonization. These findings could be helpful for controlling

the spread of MRSA in community settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study has been supported by the Center for Disease Control,

Taiwan (E9638).

REFERENCES

1. Baba, T., F. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Yuzawa, K. Aoki, A. Oguchi, Y. Nagai, N. Iwama, K. Asano, T. Naimi, H. Kuroda, L. Cui, K. Yamamoto, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819–1827.

2. Baillargeon, J. 2001. Characteristics of the healthy worker effect. Occup. Med. (London) 16:359–366.

3. Benjamin, H. J., V. Nikore, and J. Takagishi. 2007. Practical management: community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA): the latest sports epidemic. Clin. J. Sport Med. 17:393–397. 4. Boucher, H. W., and G. R. Corey. 2008. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46(Suppl. 5):S344–S349.

5. Boyle-Vavra, S., B. Ereshefsky, C.-C. Wang, and R. S. Daum. 2005. Success-ful multiresistant community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus lineage from Taipei, Taiwan, that carries either the novel

staphylo-coccal chromosome cassette mec (SCCmec) type VTor SCCmec type IV. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4719–4730.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Four pediatric deaths from community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—Min-nesota and North Dakota, 1997–1999. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 48:707–710.

7. Chen, C. J., L. H. Su, C. H. Chiu, L. Y. Lin, K. S. Wong, Y. Y. Chen, and Y. C. Huang. 2007. Clinical features and molecular characteristics of invasive community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in Taiwanese children. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 59:287–293.

8. Chen, F. J., T. L. Lauderdale, I. W. Huang, H. J. Lo, J. F. Lai, H. Y. Wang, Y. R. Shiau, P. C. Chen, T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2005. Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus in Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1761–1763.

9. Chongtrakool, P., T. Ito, X. X. Ma, Y. Kondo, S. Trakulsomboon, C. Tien-sasitorn, M. Jamklang, T. Chavalit, J. H. Song, and K. Hiramatsu. 2006. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in 11 Asian countries: a proposal for a new nomenclature for SCCmec elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1001–1012.

10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A7. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 18th informational supplement. M100-S18. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 12. Coronado, F., J. A. Nicholas, B. J. Wallace, D. J. Kohlerschmidt, K. Musser,

D. J. Schoonmaker-Bopp, S. M. Zimmerman, A. R. Boller, D. B. Jernigan, and M. A. Kacica. 2007. Community-associated methicillin-resistant

Staph-ylococcus aureus skin infections in a religious community. Epidemiol. Infect.

135:492–501.

13. Creech, C. B., D. S. Kernodle, A. Alsentzer, C. Wilson, and K. M. Edwards. 2005. Increasing rates of nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococ-cus aureus in healthy children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 24:617–621.

14. Enright, M. C., N. P. Day, C. E. Davies, S. J. Peacock, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008– 1015.

15. Gillet, Y., B. Issartel, P. Vanhems, J. C. Fournet, G. Lina, M. Bes, F. Vandenesch, Y. Pie´mont, N. Brousse, D. Floret, and J. Etienne. 2002. Asso-ciation between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotizing pneumonia in young im-munocompetent patients. Lancet 359:753–759.

16. Graham, P. L., III, S. X. Lin, and E. L. Larson. 2006. A U.S. population-based survey of Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Ann. Intern. Med. 144: 318–325.

17. Hiramatsu, K., H. Kihara, and T. Yokota. 1992. Analysis of borderline-resistant strains of methicillin-borderline-resistant Staphylococcus aureus using polymer-ase chain reaction. Microbiol. Immunol. 36:445–453.

18. Huang, Y. C., K. P. Hwang, P. Y. Chen, C. J. Chen, and T. Y. Lin. 2007. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization among Taiwanese children in 2005 and 2006. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3992– 3995.

19. Huang, Y. C., L. H. Su, C. J. Chen, and T. Y. Lin. 2005. Nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in school children without iden-tifiable risk factors in northern Taiwan. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 24:276–278. 20. Huijsdens, X. W., M. G. van Santen-Verheuvel, E. Spalburg, M. E. Heck, G. N. Pluister, B. A. Eijkelkamp, A. J. de Neeling, and W. J. Wannet. 2006. Multiple cases of familial transmission of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2994–2996. 21. Hussain, F. M., S. Boyle-Vavra, C. D. Bethel, and R. S. Daum. 2001.

Com-munity-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in healthy children attending an outpatient pediatric clinic. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:763–767.

22. Ito, T., Y. Katayama, K. Asada, N. Mori, K. Tsutsumimoto, C. Tiensasitorn, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Structural comparison of the three types of staph-ylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in me-thicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45: 1323–1336.

23. Ito, T., X. X. Ma, F. Takeuchi, K. Okuma, H. Yuzawa, and K. Hiramatsu. 2004. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob. Agents Che-mother. 48:2637–2651.

24. Kaplan, S. L., K. G. Hulten, B. E. Gonzalez, W. A. Hammerman, L. Lam-berth, and J. Versalovic. 2005. Three-year surveillance of community-ac-quired Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40: 1785–1791.

25. Klevens, R. M., M. A. Morrison, J. Nadle, S. Petit, K. Gershman, S. Ray, L. H. Harrison, R. Lynfield, G. Dumyati, J. M. Townes, A. S. Craig, E. R. Zell, G. E. Fosheim, L. K. McDougal, R. B. Carey, S. K. Fridkin, and Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators. 2007. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 298:1763–1771.

26. Lina, G., Y. Piemont, F. Godail-Gamot, M. Bes, M. O. Peter, V. Gauduchon, F. Vandenesch, and J. Etienne. 1999. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leu-kocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:1128–1132.

Siu. 2005. Risk factors and molecular analysis of community methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:132–139. 28. Ma, X. X., T. Ito, C. Tiensasitorn, M. Jamklang, P. Chongtrakool, S.

Boyle-Vavra, R. S. Daum, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Novel type of staph-ylococcal cassette chromosome mec identified in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Che-mother. 46:1147–1152.

29. Moran, G. J., A. Krishnadasan, R. J. Gorwitz, G. E. Fosheim, L. K. McDou-gal, R. B. Carey, D. A. Talan, and EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group. 2006. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:666–674.

30. Muto, C. A., J. A. Jernigan, B. E. Ostrowsky, H. M. Richet, W. R. Jarvis, J. M. Boyce, and B. M. Farr. 2003. SHEA guideline for preventing nosoco-mial transmission of multidrug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus and

Enterococcus. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 24:362–386.

31. Naimi, T. S., K. H. LeDell, K. Como-Sabetti, S. M. Borchardt, D. J. Boxrud, J. Etienne, S. K. Johnson, F. Vandenesch, S. Fridkin, C. O’Boyle, R. N. Danila, and R. Lynfield. 2003. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. JAMA 290: 2976–2984.

32. Nakamura, M. M., K. L. Rohling, M. Shashaty, H. Lu, Y. W. Tang, and K. M. Edwards. 2002. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus nasal carriage in the community pediatric population. Pediatr. Infect.

Dis. J. 21:917–922.

33. Shopsin, B., B. Mathema, J. Martinez, E. Ha, M. L. Campo, A. Fierman, K. Krasinski, J. Kornblum, P. Alcabes, M. Waddington, M. Riehman, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 2000. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-suscep-tible Staphylococcus aureus in the community. J. Infect. Dis. 182:359–362. 34. Suggs, A. H., M. C. Maranan, S. Boyle-Vavra, and R. S. Daum. 1999.

Methicillin-resistant and borderline methicillin-resistant asymptomatic

Staphylococcus aureus colonization in children without identified risk factors.

Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:410–414.

35. van Belkum, A., D. C. Melles, J. Nouwen, W. B. van Leeuwen, W. van Wamel, M. C. Vos, H. F. Wertheim, and H. A. Verbrugh. 2009. Co-evolutionary aspects of human colonization and infection by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 9:32–47.

36. Vandenesch, F., T. Naimi, M. C. Enright, G. Lina, G. R. Nimmo, H. Heffer-nan, N. Liassine, M. Bes, T. Greenland, M. E. Reverdy, and J. Etienne. 2003. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:978–984.

37. Wang, J. L., S. Y. Chen, J. T. Wang, G. H. M. Wu, W. C. Chiang, P. R. Hsueh, Y. C. Chen, and S. C. Chang. 2008. Comparison of both clinical features and mortality risk associated with bacteremia due to community-acquired me-thicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:799–806.

38. Weber, J. T. 2005. Community-associated methicillin-resistant

Staphylococ-cus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:S269–S272.

39. Wertheim, H. F., M. C. Vos, H. A. Boelens, A. Voss, C. M. Vandenbro-ucke-Grauls, M. H. Meester, J. A. Kluytmans, P. H. van Keulen, and H. A. Verbrugh. 2004. Low prevalence of methicillin-resistant

Staphylo-coccus aureus (MRSA) at hospital admission in the Netherlands: the

value of search and destroy and restrictive antibiotic use. J. Hosp. Infect. 56:321–325.

40. Wulf, M. W., M. Sorum, A. van Nes, R. Skov, W. J. Melchers, C. H. Klaassen, and A. Voss. 2008. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant

Staphy-lococcus aureus among veterinarians: an international study. Clin.