‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

國立政治大學亞太研究英語碩士學位學程

International Master’s Program in Asia-Pacific Studies

College of Social Sciences

National Chengchi University

碩士論文

Master’s Thesis

1989 年中國與捷克斯洛伐克抗議活動中

媒體角色之比較分析

A Comparative Analysis of Media Role in 1989 Protests

in China and Czechoslovakia

Student: Jan Miessler

Advisor: Leonard Chu

中華民國 103 年 1 月

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

1989 年中國與捷克斯洛伐克抗議活動中

媒體角色之比較分析

A Comparative Analysis of Media Role in 1989 Protests

in China and Czechoslovakia

研究生: 梅斯勒

Student: Jan Miessler

指導教授:

朱立

Advisor: Prof. Leonard Chu

國立政治大學

亞太研究英語碩士學位學程

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to International Master’s Program in Asia-Pacific Studies

National Chengchi University

In partial fulfillment of the Requirement

For the degree of Master in China Studies

中華民國 103 年 1 月

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

Acknowledgements

I have many debts of gratitude to my thesis supervisor, Professor Leonard Chu from the College of Communication, National Chengchi University, for his extraordinary kindness, generous support, remarkable patience and, most of all, his numerous helpful suggestions that allowed me to improve several generations of this thesis' drafts. It has been a transforming process during which I have learned more than I am aware now. I would also like to express many thanks to my thesis committee members, Professor Chin-Hwa Chang from the Graduate Institute of Journalism at the National Taiwan University and Professor I Yuan from the Institute of International Relations at the National Chengchi University for their important suggestions and critical comments during my thesis proposal defense and during the thesis defense. I am also grateful for the support of Republic of China's Ministry of Education that provided me with a scholarship to study in Taiwan, to the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Prague that selected me for the scholarship, and to the professors of all my IMAS classes that helped me to understand China and the world from many new perspectives. Also, I would like to thank Gabriela Alejandra De Leon Oliva for her support, patience, and for everything else.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

Abstract

The thesis focuses on a Communist regime's control over the media institutions,

the attitudes of the journalists towards the protests, and the media discourses

before, during and after the protests in China and Czechoslovakia in 1989. It

presents and debates key factors that influenced domestic media coverage of

China’s Tiananmen protests and Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution by

comparing and discussing their impact on the outcomes of the protests.

The analysis suggests that the media and journalists played somewhat

contradictory or ambivalent but important roles during the protest events. The

main factors influencing those roles were proximity of the given media

organization to the centre of regime's political power, the proliferation of

Western-style media professionalism, and differences in the Chinese and Czech

political culture in the end of 1980s. The fact that in both countries, the

journalists of the official media were able at least temporarily to break free from

the regime's control mechanisms serves as an argument against the hypothesis

of political parallelism that is still prevalent in the comparative research on

media systems and points out the importance of focusing on the relationship

between political power and media during regime transformation.

Keywords

1989 - China - Czechoslovakia - regime change - mass media - role of

journalists - People's Daily - World Economic Herald - Rude Pravo - Svobodne

Slovo - comparative analysis - political parallelism - media discourse

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

摘 要

這篇論文比較了中國與捷克斯洛伐克的媒體在 1989 年的抗議事件中所扮

演的角色,政權對媒體機構的控制、記者對事件的態度,以及媒體在事發

之前、當中與之後對事件本身的揭露,探討影響媒體對中國北京民主運動、

捷克斯洛伐克絲絨革命的報導範圍之關鍵因素,並比較其對於抗議結果的

影響。分析指出,媒體與記者在抗議事件中扮演了模糊但重要的角色,而

影響此角色定位的關鍵因素大致在於媒體與政權的核心政治權力關係親

近、西方式媒體專業專業思想的日益擴展,以及 1980 年代末中國與捷克的

不同政治文化。事實上,兩個國家中官方媒體記者至少能暫時打破政權的

機制,成了對立於目前仍舊普遍的、對媒體系統之比較研究的政治平行觀

點的論述,指出政權轉變過程中政治與媒體關係之重要性。

關鍵詞

1989 - 中國 - 捷克斯洛伐克 - 改朝換代 - 媒體 - 記者的角色 - 人民日

報 - 世界經濟導報 - Rude Pravo - Svobodne Slovo - 比較分析 - 政治並行

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction ... 1II. Regimes in Crisis: China and Czechoslovakia in 1989 ... 13

II.1 China and Deng’s Reforms ... 13

II.2 Czechoslovakia’s Normalization ... 18

II.3 Transitology and Factors Contributing to the Protests ... 26

A Economic Problems ... 31

B Leadership ... 36

C Students and Intellectuals ... 48

D Political Culture ... 58

II.4 Situation of China and Czechoslovakia in 1989: A Comparison ... 63

III. Media and Journalists within and beyond the Communist Media System ... 74

III.1 Media Control Mechanisms ... 79

III.2 The Press and the Protests ... 90

III.3 Chinese and Czech Journalists Crossing the Line ... 94

A People’s Daily... 96

B World Economic Herald... 103

C Rude Pravo ... 111

D Svobodne Slovo ... 116

III.4 Chinese and Czech Journalists: A Comparison ... 118

IV. Media Discourses and the Protests ... 123

IV.1 Analyzing the Communist Discourse and its Shifts ... 125

IV.2 Communist Discourse in Chinese and Czechoslovak Press ... 130

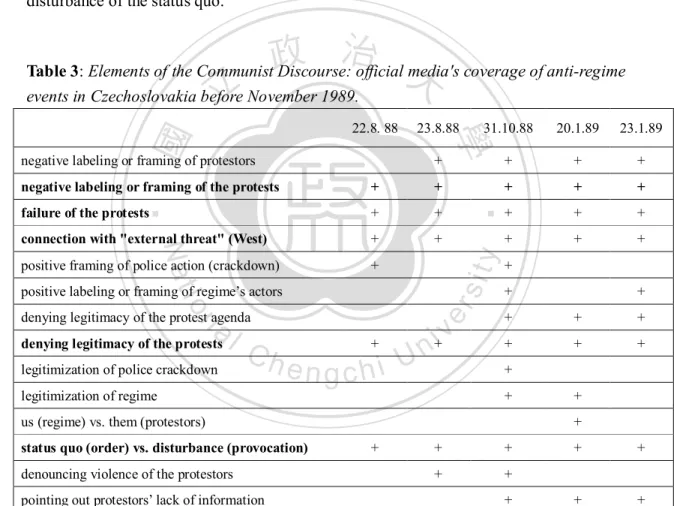

A Czechoslovakia's Discourse: Stability before November 17, 1989 ... 135

B Chinese Discourse: Towards Plurality and Back Again ... 152

C Svobodne Slovo: Negation of the Communist Discourse ... 178

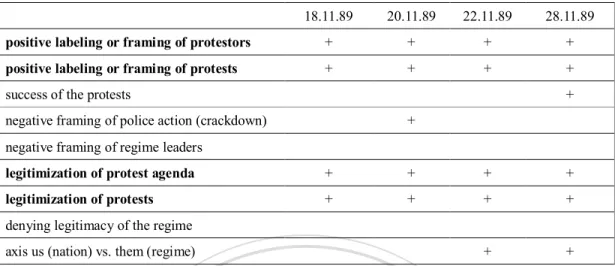

D Rude Pravo: Collapse of the Communist Discourse ... 190

IV.3 Discursive Trajectories in China and Czechoslovakia: A Comparison ... 203

V. Conclusions and Discussion ... 208

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

List of Tables

Description Page number

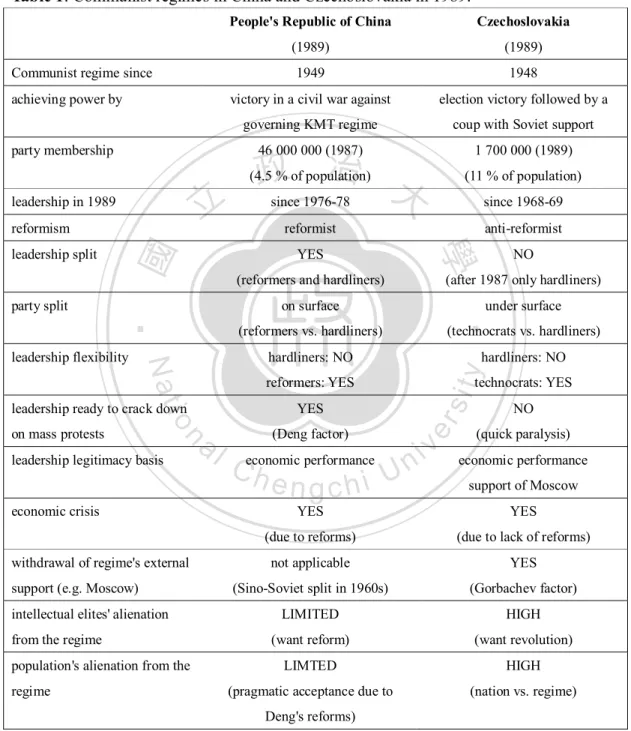

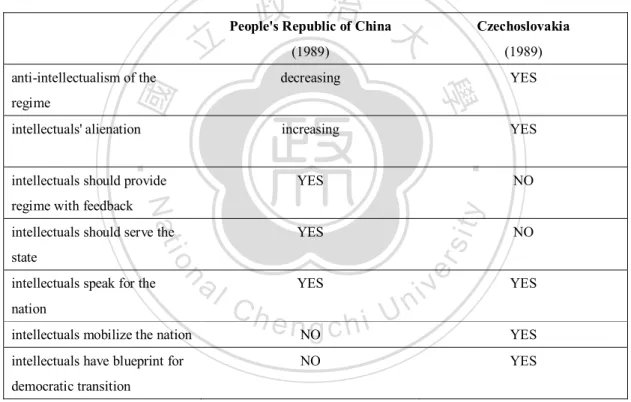

1. Communist regimes in China and Czechoslovakia in 1989 64

2. The role of intellectuals: China and Czechoslovakia in 1989 70

3. Elements of the Communist Discourse: official media's 151

coverage of anti-regime events in Czechoslovakia before November 1989

4. Discourse of the Chinese mass media during Beijing protests 177

5. Inversion of the Communist Discourse in Svobodne Slovo 189

6. Velvet Discourse in Svobodne Slovo 189

7. Collapse of the Communist Discourse in Rude Pravo 201

8. Collapse of the Communist Discourse in Rude Pravo: inversion 202

and neutralization of its core elements in face of opposition's victory

Appendices

1. Chronology of Tiananmen Events, April - June 1989 231

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

I. Introduction

This thesis compares Chinese and Czech official print media during the protests of 1989 in People’s Republic of China and in Czechoslovakia. The thesis has its focus on regimes’ control over the media institutions, the role of journalists in the protests and on the media discourses before, during and after the protests. The analysis presents and debates key factors that influenced domestic media coverage of China’s Tianamen Square protests and Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, which both happened in the year of 1989,by comparing their impact on the outcomes of the protests.

The findings should provide valuable feedback for existing accounts on media role in the democratization process and on the role of journalists as pro-democracy actors. In fact, the findings suggest that although media and journalists indeed played significant roles, these roles might not always be interpreted as beneficial for the democratization in general or for the outcome of pro-democratic protests in China and Czechoslovakia in particular.

The two selected cases - Tiananmen Square protests and Velvet Revolution - allow us to analyze conditions under which the journalists, who originally operated within the regime-controlled Communist media systems, decided to disregard media control mechanisms when many of them came to a conclusion – as Marx and Engels would have probably said – that they have nothing to lose but their chains.

The comparison of the two cases should point out their similarities and differences and help to evaluate relative importance of media and journalists among various other explanatory factors for the failure of democratization in the case of Beijing protests and its success in the case of Velvet Revolution. Basically, there are theories of transitions to democracy on one hand and accounts on the role of the media in the democratization process on the other hand, and they both focus on different factors in order to explain the same results.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

In the end, as O’Neil observes,1 although the mainstream accounts on transitions from Communism to democracy usually maintain that media performance was an important factor in the regime transition, these accounts fail to elaborate the nature of this importance. On the other hand, accounts that primarily focus on media performance during the protests usually do not link their "media factor" with the general transition theories. Thus we can follow Goldman’s claim that media "played a pivotal role" in the Tiananmen Square protests2 and similar claims about the role of the media in Czechoslovakia,3 but we need to place the accounts about the media in a more general framework of transitologist literature.

As the evidence suggests, the ways in which the media were controlled in China and Czechoslovakia were basically the same. Only official institutions were allowed to publish a newspaper, both countries had special party-state organs responsible for keeping the media in line and there was a system implicitly encouraging self-censorship. Under normal circumstances, journalists were very careful regarding what to publish and well aware of their position within the system and the mechanism of media control worked to the party-state satisfaction while there was no crisis.

However, a closer look reveals that some media organizations were actually at least partially "shielded" from the party-state control mechanisms. Moreover, while the party central organs – People’s Daily in China and Rude Pravo [Red Justice] in Czechoslovakia – were led by high party officials and their journalists had to be party members, some of them wanted to serve their party - and their readers - by covering events as they were: in words of

1

P. O’Neil, Communicating Democracy: The Media and Political Transitions. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998, p. 3.

2 M. Goldman, "The Role of the Press in Post-Mao Political Struggles," in Lee Chinchuan, Ed. China’s Media, Media’s China. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1994, p. 28.

3

M. Smid. (2013.) "Ceska media a jejich role v procesu politicke zmeny roku 1989." [Czech Media and their Role in the Process of Political Change in 1989."] [Online] Louc.cz Available: http://www.louc.cz/pril01/listopad.pdf [2013-10-15]

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

China's leading muckraking journalist at the time, Liu Binyan, this was for them "a higher kind of loyalty".4 And there were also other media organizations and other journalists who would rather prefer professional (in the Western sense of journalistic professionalism) over party criteria for the evaluation of their reporting and who would prefer political reform if not an outright change of the regime. Therefore, in addition to party organs, it is important to also examine such "shielded" media which were also involved in shifting the discourse away from the official line, e.g. media such as World Economic Herald in China or Svobodne Slovo [Free Word] in Czechoslovakia. Finally, it is necessary to look in closer detail on how and to which extent this "shielding" worked.

The interesting thing which the thesis will illustrate is that initially, the outcome of the protests seemed more promising in China than in Czechoslovakia, and the discourse in the official media also reflected that. In China, the reformist World Economic Herald was writing about such things as neo-authoritarianism and press freedom before the protests took place, and even the regime's mouthpiece People's Daily dared to publish penetrating investigative reports. In Czechoslovakia, Svobodne Slovo could shift the discourse only after the protests took place, since there were no powerful reformists in the Party or in the government to protect them, while the regime's mouthpiece Rude Pravo maintained the hard line as long as it could.

In order to understand the role of the key "discourse-shifting" media better, it is important to compare them with the official party dailies. The bigger picture is again somewhat surprising, given the widely popular theories of the Communist press5 or the final

4

Liu Binyang, A Higher Kind of Loyalty: A Memoir by China's Foremost Journalist. Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

5

e.g. F.S. Siebert, T. Peterson and W. Schramm, Four Theories of the Press. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1956. Also see K. Jakubowicz, "Media as Agents of Change," in Glasnost and After. Media and Change in Central and Eastern Europe. D. Paletz, K. Jakubovicz and Novosel, Eds. Creskill: Hampton Press, 1995, pp. 19-48.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

results of the protests. For example: while it is true that People’s Daily published the notorious April 26, 1989 editorial, based on Deng Xiaoping’s speech and condemning the protests with very harsh words, it is also true that its journalists joined the protests and for some time provided sympathetic coverage (which lasted until their resistance was quelled and their editors replaced). In Czechoslovakia, on the other hand, the Communist Party’s organ played its assigned role and initially downplayed the protests. Only after the demonstrations became too widespread and the reporting by other media too fearless, the Rude Pravo’s discourse collapsed; later, its journalists themselves voted to replace their party-appointed chief editor with his deputy (who later kicked out the most compromised hard-line staff and privatized the daily for himself).

The central argument of this thesis regarding the similarities and differences between the cases is following: In both China and Czechoslovakia, the journalists wanted to cover the protests, but the media control mechanisms prevented them from doing so during earlier occasions. There had been a conflict between journalistic professionalism and the party line, and until the 1989 protests, the party line always prevailed. But while in Czechoslovakia the media joined the protests very quickly, in China they were much slower and instead of directly mobilizing the population for the support of the protests (as Svobodne Slovo did in Czechoslovakia), they provided only sympathetic coverage instead of the so called "call to action".

Another finding of the thesis is that this overcoming of the control mechanisms (in both China and Czechoslovakia) on the part of the journalists was possible only due to a paralysis of the party decision-making mechanism. However, the nature of this paralysis was very different. In China, the paralysis was caused by a conflict between hardliners and reformers, e.g. elites vs. elites, and after the resolution in favor of the hardliners, a crackdown followed. In Czechoslovakia, the paralysis was caused by the hardline leadership realizing the scope of the massive defection of party cells once the protests were on their way. The leaders felt

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

isolated and decided not to shoot. Their passivity caused their regime to collapse.

Further, as the evidence presented in the thesis shows, while in China the protesting people (and journalists) wanted basically to improve the system by the means of talks with the regime, in Czechoslovakia they wanted to replace the system by forcing the regime to leave completely.

As for the explanations of the events, the initial part of this thesis notes that most of the accounts focus either on the structure of the situation and on the rational motivation of the actors, or on cultural context. The authors often mention various factors (or their combinations) responsible for the different outcomes in Czechoslovakia and China, such as party legitimacy, party divisions, economic situation, social modernization, leadership qualities of party and protest leaders, role of intellectuals, opposition strategies, looming cultural crisis etc. An alternative, culture-based explanations imply that while the Velvet Revolution has been essentially based on Czech nationalism and the conflict ran between the [Czech] nation and [Communist] state, the Tiananmen has been decidedly an elitist affair with many signs of divide between the protesters [aspiring elites criticizing the incumbent elites] and the rest of the Chinese population [passive, not expected to get involved]. While the Czech nationalism behind the Velvet Revolution united all strata of the population and mobilized them into the conflict against the regime which, from the nationalist point of view, has been imposed from the outside and therefore lacked the legitimacy, the Chinese elitism – best illustrated by the "new authoritarianism" debate – had inhibiting effects on the protests and effectively prevented a possible popular mobilization against the regime.

Almost twenty years ago, the pioneer Chinese media scholar Chin-Chuan Lee observed that "hindsight has provided us with a finer vantage point to reflect on the media changes that have resurged after the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989. Commentators have paid inadequate attention to the media impact of global developments on China, just as their role in helping undo the Soviet empire and autocratic regimes in Eastern Europe as well as easing

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

democratic transitions elsewhere (including Taiwan) has largely been overlooked".6 Although several important works appeared since then, Lee's statement still seems to be true. This thesis is therefore an attempt to provide a new impulse to the debate and to bridge a gap created by parochialism of individual disciplines. The media in China and Czechoslovakia during the 1989 protests have not yet been compared; comparative accounts on Eastern Europe's transitions and China's 1989 non-transition to democracy are also very rare; the mainstream transitology does not pay much attention to media and accounts on media's role in 1989 events do not pay much attention to transitology.

Due to the time, space and language barriers, the thesis limits itself on using mostly published secondary sources in English and Czech languages. This is partly compensated by the fact that the existing literature in English about Chinese media and about Tiananmen Square events of 1989 is rather extensive, and translations of key documents and media texts are also available in English. On the other hand, the literature about Velvet Revolution and Czechoslovakia's media is very limited, especially in English. The samples of the Czech media texts have been translated by the author of this thesis.

In summary, the primary aim of the thesis is to provide an analysis of framework of the media control in the context of political situation of China and Czechoslovakia in the late 1980s and of the role of the Chinese and Czech journalists from the official media in the protests, focusing on the questions (1) what factors led the journalist to step beyond that framework in order to cover the protests? and (2) what was their role in the success or failure of those protests? The secondary aim is to illustrate and support this analysis by exploring key instances of the media discourse.

In order to provide an overview of key factors behind the media performance during the student protests in Czechoslovakia and China, the thesis first explains the logic of comparing

6

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

these two cases and provides context of the two events, based on the key accounts explaining regime change in Czechoslovakia and regime survival in China in 1989. Then the thesis will focus on the role of media, as they were reflecting the reality and also influencing it by their reflections, and especially on the underlying antagonism between the logic of media control on one hand and journalist professionalism on the other hand. In the next part, the thesis will analyze the mechanisms of the China’s and Czechoslovakia’s systems of media control which were designed to prevent reflections of inconvenient topics and perspectives, but which failed in the key moments and allowed sympathetic (or at least neutral) coverage of the protests. In order to illustrate the struggle on the pages of the press, the determination of the Chinese leadership to deal with the protest with force and the collapse of Czechoslovak leadership facing the protests, several key instances of media discourses will be analyzed. Finally, the findings will be discussed in order to suggest a more general explanation for the functioning of media control mechanisms and for the role of journalists in anti-regime pro-democratic protests.

The choice of China and Czechoslovakia in 1989 for comparison has several reasons: both countries shared similarities in the structure of their Communist political systems, but their Stalinist or Maoist eras were long past. Both experienced economic problems before the protests that took place in 1989. These protests, taking place in the same year, not only profoundly challenged the regime, but were also remarkable for the important role of dissatisfied students and intellectuals at their helm. There are also similarities in the ways the regimes had controlled their presses: in both countries, the media were generally regarded as mouthpieces of their parent political organizations and the desired goal was to create an appearance of "united front" where all the media speak with one official voice. However, in both countries, due to varying degrees of proximity or distance from the centre of power, the regime’s grip of the mass media had not been as monolithic as before, and during the protests, the official voice lost both its monopoly and its former coherence.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

There are also important differences, among them the population, the social structure and the level of development of the two countries. In 1989, China’s population was already over one billion (most of them ethnically Han), compared with Czechoslovakia’s mere 15 millions (divided between 10 millions of Czechs and 5 millions of Slovaks). Despite significant progress, the illiteracy and semi-illiteracy in China was still around 16 percent according to 1990 census, down from 22 percent in 1982,7 compared with fully literate population of Czechoslovakia, and 0.2 percent of university students in Chinese population in 1989 also do not compare favorably with Czechoslovakia's 7.2 percent share of university graduates in the population. Despite its rapid urbanization especially in the coastal areas, China was still a rural country while Czechoslovakia was a leading industrial country already in the early 20th century with only about 10 percent of the population in agriculture as of the late 1980s. The GDP per capita was 400 USD per year in China and 3800 USD per year in Czechoslovakia. Finally, China's land area was about 9.6 millions square kilometers and Czechoslovakia's only 128 thousands. In other words, while Czechoslovakia in 1989 was a middle-sized developed European country, China in the same year was Asia's biggest, but poor and still only developing country.

Even more important differences can be seen when we compare the countries' political leadership. In China, many of the ruling leaders were still the members of founding generation of the People's Republic who established the regime after the victorious civil war. On the other hand, the regime in Czechoslovakia had always been a Soviet satellite. The well-known 1968 invasion of Warsaw Pact troops terminated not only the reformist Prague Spring with its peculiar form of "socialism with a human face", but also widespread legitimacy of the Communism as a political system, even among most of the remaining Party

7

Han Xiaoxing, "Democratic Transition in China: A Comparative Examination of a Deified Idea," in Chinese Democracy and the Crisis of 1989: Chinese and American Reflections. R. V. DesForges et al., Eds. New York: State University of New York Press, 1993, p. 224.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

members. This was more serious than the damage inflicted by Mao's Cultural Revolution in China's "lost decade" of 1966-76. It was Deng Xiaoping's political rehabilitation and launch of reforms that had restored the Party's legitimacy.

Most importantly, the protests had different results. the Chinese reforms in the 1980s were bold and the media were less controlled, but the protracted protests on the Tiananmen Square and elsewhere were ultimately crushed. It was only in the reform-shy and tightly controlled Czechoslovakia where the protests succeeded, with the regime collapsing surprisingly quickly. Why then, despite all these differences, compare these two cases?

The answer is precisely because of the particular mix of similarities and differences. The structure of the political systems in China and Czechoslovakia was very similar and so were the ways how the regimes maintained the "united front" appearance in the mass media. When the protests took place, journalists in both countries were facing the same dilemmas: should they follow the official line and be hostile towards the protests? Should they cover the protests with professional neutrality? Should they become a voice of the protests, or even personally join the protestors? In other words: the intensity of the conflict between the regime and its opponents, the journalists' position very close to the centre of the conflict, and their often close links with both the regime and its opponents placed them in a situation in which they had to take sides. They had an opportunity to abandon the party line, and the structure of this opportunity was the same in both China and Czechoslovakia due to the similar mechanisms of media control. The Chinese and Czech journalists behaved differently, and in the end, the protests resulted differently. It is legitimate to explore and compare the ways in which the journalists and the media might have influenced the outcomes of both events.

Comparing media during the 1989 protests in China and Czechoslovakia has also theoretical relevance. In the previous decade, comparative analysis of media systems returned to media scholars’ research agenda, with Hallin’s and Mancini’s influential

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

Comparing Media Systems8 replacing the Cold War classic Four Theories of the Press by Siebert et al.9 as the main point of reference. However, as Hallin and Mancini now acknowledge10 and other researchers generally agree,11 the framework of their comparative study serves rather as a starting point for a further debate than as a definite statement. In contrast to the "four theories" paradigm with its authoritarian (Third World), libertarian (West), Soviet (Communist countries) and social responsibility (e.g. desirable in the West) media system models based on underlying philosophical principles of a given regime, Hallin and Mancini based their media systems typology on selected empirical evidence from Western Europe plus USA and Canada. Their framework consisting of polarized pluralist, democratic corporatist, and liberal models is therefore rather narrow and attempts to accommodate other countries within the framework usually run into difficulties. Also, despite the hypothesis of Hallin and Mancini that the observed countries might converge, their book pays little attention to a possibility of quick and profound transformation of a media system (e.g. during a regime change) or to a possibility of divergence of two media systems that would previously belong to the same model.

The problem is that in the late 1980s and in 1990s, when the political changes in the Communist countries were taking place, the comparative media research had been rather

8

D. C. Hallin and Mancini, Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

9 Siebert et al. 1956. 10

D. C. Hallin and Mancini, Eds., Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012

11

K. Voltmer, "How Far Can Media Systems Travel? Applying Hallin and Mancini’s Comparative Framework Outside the Western World," in Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World, D. C. Hallinand Mancini, Eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 224-245, or A. W. Wyka, "In Search of the East Central European Media Model – The Italianization Mode? A Comparative Perspective on the East Central European and South European Media System." in Comparing Media Systems in Central Europe: Between Commercialization and Politicization. Dobek-Ostrowska, B., Glowacki, M. Wroclaw: University of Wroclaw Press, 2008, pp. 55-69.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

neglected with the overall focus of the researchers on media globalization. Despite occasional attempts to de-Westernize the media theory and sometimes even to include Communist media systems,12 the language barrier on the part of the Western researchers and the gap in knowledge of the Western media research discourse on the part of their Eastern colleagues prevented emergence of larger body of comparative media research, especially one focusing on Eastern Europe. Although there are studies of what was going on with the media after 1989 in Czechoslovakia or generally in Eastern Europe13 and in China,14 there are no comparisons between the "successful" media democratization cases of Eastern Europe and the "unsuccessful" Chinese case. Moreover, there are no studies focusing on the comparison of the turning points when the Communist regimes’ control over the media failed, the journalists took over their media organizations and started to support the protests. Theoretical accounts on comparing systems of media control are also hard to find: the chapters of Blumler et al. Comparatively Speaking15focus on other issues, as does

12 J. Curran and M. J. Park, Eds. De-Westernizing Media Studies. London: Routledge, 2000. J. Downing, Internationalizing Media Theory: Transition, Power, Culture. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1996. P. Gross, Entangled Evolutions: Media and Democratization in Eastern Europe. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2002. R. Gunther and A. Mughan, Democracy and the Market: A Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. M. E. Price, B. Rozumilowicz and G. S. Verhulst, Eds. Media Reform: Democratizing Media, Democratizing the State. New York: Routledge, 2002. C. Sparks and A. Reading, Communism, Capitalism, and the Mass Media. London: Sage, 1998. S. Splichal, Media Beyond Socialism. Theory and Practice in Central Europe. Boulder: Westview Press, 1994.etc.

13 D. Paletz, K. Jakubowicz and Novosel, Eds. Glasnost and After. Media and Change in Central and Eastern Europe. Cresskill: Hampton Press, 1995. K. Voltmer, Ed., Mass Media and Political Communication in New Democracies. London: Routledge, 2006.

14

He Qinglian, The Fog of Censorship: Media Control in China. New York: Human Rights in China, 2008. Zhao Yuezhi, Media, Market, and Democracy in China: Between the Party Line and the Bottom Line. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998.Zhao Yuezhi, Communication in China: Political Economy, Power and Conflict. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. Zhao Yuezhi, "Understanding China’s Media System in a World Historical Context," in Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World, D.C. Hallin and Mancini, Eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 143-173.

15

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

Livingstone.16At the same time, accounts dealing with success or failure of democratic transitions avoid mentioning the media among the key factors. This is the case with the classical study by Linz and Stepan Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation17as well with other authors who analyzed Tiananmen protests18 or Czechoslovakia’s transition19 This might be, as Doorenspleet suggests, a legacy of a general bias towards context-free and often simplifying generalizations.20

As this thesis suggests, the roles of the media and of the journalists can be ambiguous. That might be the reason why the media are being left out of the transitology’s most successful explanations. Contrary to such accounts, this thesis argues that although the media’s role in the success or failure of a democratic transition might be ambiguous, the cases of China and Czechoslovakia in 1989 clearly show that media and journalists were far from being irrelevant.

Space and Time. Newbury Park: Sage, 1992.

16

S. Livingstone, "On the Challenges of Cross-National Comparative Media Research." European Journal of Communication, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 477–500, Dec 2003.

17

J. Linz and A. Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1996.

18

R. Baum, Burying Mao. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994. C. Calhoun, Neither Gods nor Emperors. Students and the Struggle for Democracy in China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. 19 G. Ekiert, The State against Society: Political Crises and Their Aftermath in East Central Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996. S. Saxonberg, The Fall: A Comparative Study of the End of Communism in Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary and Poland. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 2001. 20 R. Doorenspleet, Democratic Transitions: Exploring the Structural Sources of the Fourth Wave. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2005.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

II. Regimes in Crisis: China and Czechoslovakia in 1989

In order to provide context for the analysis of the media and journalists during China's unsuccessful and Czechoslovakia's successful transition, this chapter will first provide basic narratives of the events in China and Czechoslovakia and then will present an overview of relevant accounts dealing with political transitions, i.e. transitology, focusing on key issues that are usually identified as the main contributing factors to emergence and success of transitions: the economic crisis as a general background for popular discontent with the regime; the regimes' leadership, its divisions and flexibility; and the regime's opponents, e.g. students and intellectuals, and their tactics. These areas will be complemented by reviewing selected accounts on political culture in China and Czechoslovakia before and during the protests.

II.1 China and Deng’s Reforms

After many initial setbacks, the Chinese Communist Party under Mao Zedong's leadership survived both Chiang Kai-shek's annihilation campaigns and Japan's invasion to China, won a civil war against Kuomintang and established People's Republic of China in 1949. Thanks to its initial success in uniting the country and stabilizing the economy, it enjoyed substantial popularity. However, some of the campaigns initiated by Mao, most notably the Great Leap Forward in the 1950s and the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s undermined popular support for the regime and alienated many social strata, most notably the intellectuals. After Mao’s death and the end of the Cultural Revolution, the Party had lost a lot of its former legitimacy. Mao's chosen successor Hua Guofeng got rid of the vastly unpopular Gang of Four of which the most prominent member was Mao's widow Jiang Qing, but he did not get rid of Maoism. However, he proved to be only a transitory figure and soon lost his position to the three times purged but once again ascending Deng Xiaoping. Quickly after

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

consolidating his position, Deng got rid of both extreme Maoism and of Hua.

In the leadership, Party members elevated to their posts during the Cultural Revolution were gradually sidelined by people loyal to the new "paramount leader." Many disgraced officials were rehabilitated and some of them returned to high posts. At the same time, Deng created incentives for the less dynamic "older comrades" to retire, being himself the most significant exception to his own rule. Still, the Party remained in the hands of party elders, often octogenarians, while the "young" leaders Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang were behaving submissively to them.21

Intellectuals initially supported Deng as a figure who could open up space for more free expression while Deng needed them for his modernization of China. However, as the program of Four Modernizations illustrated, the focus had been on economic reforms and not on democratization – the so called "fifth modernization," demanded by dissidents since the Beijing Wall events in 1979. Instead of democratization, careful and gradual economic reforms of the early 1980s were supposed to be complemented by a "socialist spirit."22

However, this socialist spirit did not prevent intellectuals such as Wang Ruoshui of People's Daily or Ru Xin from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences from turning Marx against the supposedly Marxist-Leninist regime and launching a debate about alienation and socialist humanism.23 After hardliners convinced Deng that this was not acceptable, a campaign against "spiritual pollution" was launched. Leading intellectuals engaged in the debate were attacked - and sacked - for their "abstract humanism", "abstract concepts of democracy" and producing "such talk [that] cannot help people gain a correct understanding."24 But after the reformers Hu and Zhao made Deng shift back to their side,

21 Baum 1994, 134 22 ibid., 148 23 ibid., 153 24

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

the campaign halted.

Part of the counterattack that Hu and Zhao orchestrated against their opponents was Hu's instruction to People's Daily editorial department to prepare a series of commentaries supporting economic reform.25 They were aware that the economic performance became vital for the regime to stay in power, as the people grew cynical about the role of the Party. A full-fledged return to some kind of Maoism based on charismatic leadership was out of question since Mao and most of the first generation of the great CCP leaders were dead, but the conservative leftwing hardliners could still manage to derail Deng’s, Hu's and Zhao's reforms. In the end, the reformers usually prevailed with Deng being the decisive actor tipping the balance in their favor, but only after periods of short-lived campaigns orchestrated by hardliners trying to push China in the opposite direction.

However, Deng's, Hu's and Zhao's reforms created new problems, which their opponents were quick to point out. Thus, after China's urban areas experienced economic boom in the mid-1980s, the hardliners could - and did - make a point about cadres' growing crime and corruption which actually echoed popular opinion.26 As a result, and also due to emerging problems with dropping living standards in the second half of the 1980s, public confidence in Deng and his reforms started to decrease.27 Still, despite occasional campaigns such as the one that followed student protests in 1986-87 and caused Hu Yaobang's fall, the reforms were being pushed trough if not by disgraced Hu, then by his even bolder colleague Zhao who replaced him in the post of general secretary.

In the end of the 1980s, situation seemed far from being stable. The economic reforms were not accompanied by political reforms, because these would go against CCP's monopoly

25

Baum 1994, 164 26

ibid., 172

27 M. Meisner, The Deng Xiaoping Era: An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994. New York: Hill and Wang, 1996, p. 353.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

on political power. At the same time, the side-effects of the reforms created social pressure that could not be confined within the non-reformed political structure. Finally, as China gradually opened windows to the Western "fresh air", ideas about an alternative political structures were blown inside. Once again, intellectuals were ready to debate how a desirable political regime in China should look like, the students were ready to protest against appalling conditions in their dormitories and against many other issues, and general population was nervous about course of the economic reforms that were undermining their previously stable and predictable livelihoods. The leaders could not derive their legitimacy neither from their non-existing charisma, nor from the economic prosperity that seemed to work only for certain people with certain guanxi but not for the majority of others. Almost everyone was dissatisfied.

On April 15, 1989, Hu Yaobang died after suffering a heart attack during a politburo meeting. Using his death as an excuse for protests that were actually already being planned, the students staged a sit-in at Tiananmen Square on the night before Hu's memorial service at the Great Hall of the People, despite official ban. On April 24, they declared boycott of their classes and started organizing an independent national student federation. The demonstrations turned into a fundamental challenge to the regime - partly because, as Lieberthal observed,28 the regime treated them as such - and their agenda expanded from a mere criticism of appalling dorm conditions, official corruption and inflation towards calls for press freedom and greater democracy. After a neutral or even favorable coverage of pro-reform media, a watershed came in a form of April 26 editorial in People’s Daily, based on a speech of Deng Xiaoping to the inner circle of other top Chinese leaders and harshly condemning the protests29 (for more details about the article, see chapter IV.2, section A, of

28

K. Lieberthal, Governing China: From Revolution to Reform. New York: W. W. Norton, 1995, p. 140. 29 Lieberthal 1995. Also see Zhao Ziyang, Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang. New York: Simon and Shuster, 2009.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

the thesis).The demonstrations spread to other cities and were joined by number of workers, small entrepreneurs and even by some Party members. Interestingly, as Lieberthal recalls, "on May 4, the huge crowds cheered when a contingent from the CCP Central Committee Propaganda Department marched into square holding aloft a banner proclaiming that henceforth they would publish only the truth."30 Journalists from other official media also joined the protests. Still, despite explicit support and requests for participation by members of other social strata, the students initially guarded their leading role in the protests to such an extent that they often blocked non-students from joining out of fear of regime-orchestrated infiltration.

Zhao Ziyang has been initially one of the targets of the students' criticism because his sons had been allegedly involved in corruption. On the other hand, he had been associated with promoters of democracy, although more recently, his supporters started to discuss the idea of "neo-authoritarianism" in order to boost Zhao's position as Deng's apparent successor. On May 3, Zhao's surprisingly sympathetic response to the students' demands was broadcasted on the national evening news. This boosted his popularity among the protestors, but undermined further his position in the Party leadership where, at the time, the hardliners who were unsympathetic to the students had the upper hand.31 Zhao remained in charge until mid-May Gorbachev's visit, but immediately after the Soviet leader departed, he had been stripped of his power by Deng and his fellow retired octogenarians in spite official Party rules that did not allow deposing the Party secretary in such an ad-hoc way.32

The Gorbachev visit actually became an embarrassment for the whole Party leadership. The hunger strike that the students staged at Tiananmen attracted international media attention and prevented the authorities to stage a crackdown. When the troops tried to move

30 Lieberthal 1995, 141 31 see Zhao 2009 32 Lieberthal 1995, 141-142

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

into the city on May 19, after Gorbachev's departure, they were blocked by the capital's entire urban population that became sympathetic to the protesters.33 The army had to withdraw, but on the night from June 3 to June 4, fresh units were brought to the capital with orders to seize the Tiananmen using any means necessary. This time, the student protest ended in a bloodbath and persecution of its participants; the prospects of democratic transition vanished.

II.2 Czechoslovakia’s Normalization

Parallel with the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, independent Czechoslovakia had been re-established by the pre-war political establishment. However, the right-wing parties that collaborated with the German occupation were banned and the parties were united into a National Front. The Czechoslovakia's Communist Party won the 1946 election by a large margin thanks to its superior tactics and its reputation as a bold enemy of the Nazis, but in 1948, it stages a Soviet-backed coup and transformed the country into a one-party state, closely following the Soviet model.

However, the centralization of the economy and political decision making proved to have their limits and twenty years after the coup, in early 1968, the Party was divided between reformers and hardliners. After more than ten years in office, the neo-Stalinist president and Party secretary Antonin Novotny became increasingly isolated and in March 1968, he was forced to resign and leave political life. The reformers, who were gaining momentum, replaced him by more flexible Alexander Dubcek as a Party secretary and started to implement economic and political reforms. Quickly, Dubcek became a popular public figure, representing Czechoslovakia’s new "socialism with a human face" and a reformist push towards economic and political liberalization.

The reforms were popular especially among intellectuals who "mobilized all the creative

33

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

forces to a degree unknown since 1948, and forced Dubcek to follow the proposed reforms to their logical conclusion."34 However, there were two important problems. First, although Dubcek’s leadership had been formally in charge, the dynamics of the Prague Spring quickly outpaced the Communist Party’s reform schedule, so that the party lost its grip and often struggled to keep pace with increasingly profound changes in society that were happening without official sanctions. Second, the logical conclusions of the reforms would be a liberalized political system and a market economy, e.g. a complete reversal of the previous twenty years of hard-line policies following the example of the Stalinist Soviet Union.

Despite its domestic popularity, this new kind of socialism clearly deviated from the official ideological canon defined by Moscow. The conservative leadership of Leonid Brezhnev repeatedly warned Dubcek and his colleagues that the reforms in Czechoslovakia were not acceptable. Reformists in turn claimed that their reforms were Czechoslovakia’s specific contribution to the theory and practice of Socialism, nothing they had done went against country’s membership in the Warsaw Pact, and that their allegiance to Communism had remained strong. At the same time, however, the Soviet Ambassador to Prague Chervonenko, the KGB and the hardliners within the Communist Party were informing Moscow about alleged chaos and revisionism supervised by confused and powerless Dubcek. To the suspicious Soviet leadership, their version sounded more convincing. As happened in the past in Hungary, Poland and East Germany, the Soviets were ready and willing to prevent "political chaos" and bring their satellites back to the path of "socialist democracy" using their tanks. Still, the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia on August 21, 1968 came as a surprise not only to ordinary citizens, but also to the reformist leadership.

Although the possible results of Czechoslovakia’s reforms might have proved problematic or even contradictory in the long term, their abrupt reversal after the invasion

34 J. F. Bradley, Czechoslovakia's Velvet Revolution : A Political Analysis. New York: Eastern European Monographs, 1992, p. xviii.

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

demoralized the society. "The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 ended the optimum chance for a fundamental reform of a socialist regime and started the long process of the decay of Communism that was to culminate in the Velvet Revolution just over two decades later. It dashed the hopes of a substantial section of the population, whose active involvement in public affairs had reflected a revitalization of their beliefs in both socialism and democracy."35

The so called "normalization" meant a restoration of pre-1968 realities, negating and abolishing most of the gains of the Prague Spring. Moreover, there were widespread purges – "the largest purges of Communist Party membership in the history of Eastern Europe," as Linz and Stepan describe it.36 Dubcek and his group of reformist politicians failed to depart from their official posts with grace and were removed in a humiliating way. About half a million of Party members resigned, were expelled or "deleted" (out of the original total of 1.5 million Party members in a country with population of about 15 millions). Purges took place in all major institutions, including universities and media, which were placed under tight control.37 "There were 1,500 journalists dismissed from Radio Prague alone and Rude Pravo fired 45 of its 80 editorial staff; 900 university professors lost their jobs and 1,200 researchers had to find work outside the Academy of Sciences; 117 writers were banned and 344 artists forbidden to exert their profession; 14,000 full-time party officials also lost their jobs, while 140,000 Czechs and Slovaks were forced to emigrate."38

This obviously caused resentment among the purged. The intellectuals felt that their country turned into a "cultural desert" and the general population that failed to depart to the West opted for "inner emigration" into private realm. Compared with Hungary after 1956,

35 B. Wheaton and Z. Kavan, The Velvet Revolution: Czechoslovakia, 1989-1991. Boulder: Westview Press, 1992, p. 3.

36

Linz and Stepan 1996, 318 37 Wheaton and Kavan 1992, 7 38

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

Czechoslovakia’s regime remained intolerant and forced everyone to participate in public acts of compliance, which became empty rituals but nevertheless served as a tool of maintaining status quo. As one of the banned authors Vaclav Havel described in his essay The Power of the Powerless (written in 1978),39 this ritualized compliance with a regime that lacked popular legitimacy resulted in an "as-if game": people were acting "as-if" they believed in the official propaganda and in exchange, they did not have to behave in the way the ideology prescribed.40 Moreover, the regime provided them, at least initially, with adequate material standard. Czechoslovakia's "normalization" thus became a version of Hungary’s post-1956 "goulash Communism", e.g. modest level of consumerism provided by the regime in exchange for the compliancy of the ruled.

However, this short-term solution of the Soviet-imposed regime’s lack of legitimacy proved self-defeating in the long term. It led to a moral corruption, widespread stealing, pilfering, exploitation of patronage and avoiding hard work by the general population. The large-scale corruption among the Communist elite provided a justification for a small-scale corruption among ordinary people, but at the same time, this all obviously undermined regime’s economic sustainability. In the end, the increasingly poor and inefficient planned economy was unable to provide enough consumer goods and the exchange of public compliance with normalization for a reasonable standard of living became unsustainable.41

Still, during the 1970s and most of the 1980s, the "goulash socialism" bargain worked, the opposition against the regime had been quite isolated and its critique of the regime on moral grounds unappealing. A broad coalition of regime critics, including expelled reform Communists, Social Democrats, liberals and conservative Catholics emerged in 1977 around Charter 77, a document questioning regime’s human rights record, but it remained a domain

39

V. Havel, The Power of the Powerless. London: Hutchinson, 1985 [1978]. 40 Wheaton and Kavan 1992, 10

41

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

of dissident intellectuals from Prague and Brno.42 However, in the 1980s, the young generation proved less apathetic and demoralized and more willing to question regime’s numerous weaknesses. The regime itself became less repressive and less willing to control the youth, and while it became increasingly difficult to deliver the regime's part of the "goulash" deal, from the increasingly available Western media it became increasingly obvious that the West was offering a better deal to its own citizens. Instead of getting used to the "normalization", the young people became alienated.

Moreover, the international situation changed as well and undermined another aspect of the imposed regime’s legitimacy. New Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev abandoned the Brezhnev doctrine of military interventions in satellite countries in case of their "deviation" from Socialism, and pushed forward perestroika, glasnost and "new thinking." Actually, these were the same things that prompted his predecessor Leonid Brezhnev to launch the military intervention to Czechoslovakia in 1968 and to terminate Dubcek’s reforms. Now, after implementing their own version of Prague Spring reforms, Soviets could no longer claim their invasion to be completely legitimate. At the same time, the Czechoslovakia’s hard-line leaders had the same problem: adoption of Soviet reforms in their country would prove that Dubcek was right after all. In the end, the question of legitimacy proved for the regime more important than searching for solutions of the economic difficulties.43

Gorbachev originally wanted to maintain Soviet influence in the Eastern Europe, but at the same time he wanted to limit Soviet subsidies to the client regimes. In mid-1988, the Soviet position shifted towards allowing or even supporting major changes in Poland and Hungary. Czechoslovakia’s regime was nevertheless reluctant to launch any substantial reforms and its praise for perestroika and glasnost had not been translated into concrete political and economic changes. Although Soviet pressure in 1987 resulted in replacement of

42 ibid., 12 43

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

the aging hard-line architect of normalization Gustav Husak by equally hard-line, but less capable Milos Jakes on the post of Party Secretary (Husak retained only the more formal post of Czechoslovakia's president), at the same time, the group of technocrats around Lubomir Strougal had lost their position. Strougal had been a hard-liner also, but one who became supportive of reforms. The most pro-reform leader thus became the quite cautious Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia’s federation Ladislav Adamec, who could not do much being surrounded by entrenched hard-liners.

The Soviets would have probably wished for a less hard-line leadership, but they were preoccupied with improving their relations with the West and cared much less than twenty years ago for its inflexible satellite regime. Their apparent reluctance to get involved in their satellites allowed Czechoslovakia’s hard-liners to ignore Soviet reforms, but it also reduced fears of Soviet tanks among the increasingly dissatisfied population. "The illegitimate government, unwilling to act upon Gorbachev’s advice and unable to cope with the gradual evaporation of fear prompted by the example of dissident and countercultural activity and the effect of a distant perestroika, would find itself with a diminishing ability to use force to preserve itself and a declining capacity to deal with economic difficulties."44

In the end of the 1980s, political upheaval in some Eastern European countries (especially Poland with its Solidarity movement, but also Hungary with its negotiations between the regime and the opposition), economic difficulties, growth of public criticism and a rise of young generation that lacked direct experience with the regime’s oppression all contributed to emergence of open anti-regime protests. In Czechoslovakia, first substantial protest appeared in 1988. Violent repression of these protests had not only antagonizing effect on the population, but also failed to prevent new participants joining these protests. Although the active dissident supported and sometimes participated on these protests, the

44

‧

國

立

政 治 大

學

‧

N

a

tio

na

l C

h engchi U

ni

ve

rs

it

y

most of the participants were young people without prior record of opposing the regime.45 The first big protest in Czechoslovakia took place on August 21, 1988, the twentieth anniversary of Warsaw Pact invasion. About 10 thousand people gathered in the Prague’s centre, speakers denounced the invasion, demanded democratic elections, abolition of censorship, rehabilitation of victims of politic persecution, and in the end, the protest was dispersed by police, but cheered by passer-byes.46 The second protest took place on October 28, 1988, the seventieth anniversary of Czechoslovakia’s independence on Austria-Hungary after the World War I, with participation of about 5 thousands, brutal police crackdown and arrests. The third protest on December 10, 1988, a fortieth anniversary of Universal Declaration of Human Rights, had been allowed in order not to antagonize French president Francois Mitterrand on his state visit to Prague. However, the appearance of dissidents alarmed the regime which quickly returned to its previous hard-line approach.

In 1989, the protests followed the same pattern: in January, several thousands of people gathered in Prague despite official warnings to commemorate Jan Palach, who in 1969 protested against the invasion and subsequent normalization by setting himself on fire. Police responded with indiscriminate force and detained leading dissidents including Vaclav Havel (sentenced to nine moths in jail), who were sometimes not involved in the protests. This in turn led to a wave of international condemnation and to a petition with demanding democratization of the regime, signed by about 40 thousand people as of September 1989. Other protests took place on May 1, August 28, October 28 and finally on November 17, 1989.

The protest on November 17 differed from the previous events as it was an officially sanctioned event organized by Prague's student organization to commemorate Jan Opletal, a Czech student leader murdered by German Nazi occupants fifty years ago, on November 17,

45 ibid., 25 46