從跨國領導課程探索中國教育領袖的

儒家倫理及價值取向

彭新強

王婷

摘 要

研究目的 鑑於過往探討中國教育領導之儒家倫理和價值取向的實證研究 十分貧乏,本研究藉著有關的理念架構,研究一組中國教育領袖的 個人及其機構的價值取向。本研究旨在檢視當代中國教育機構是否 仍然注重儒家倫理的價值觀,以及評估教育領導及其機構在日常管 理工作中,在「等級關係」、「集體主義」、「人文主義」和「自 我修養」等價值的注重程度。 研究設計/方法/取徑 本研究制定了一套具有 53 項價值陳述的機構價值量表(IVI) 的標準工具,以評估教育領袖在日常的管理環境下的價值取向。而 研究之對象為 67 位參加了在中國浙江省舉行的澳洲跨國領導碩士課 程中的教育領袖。 彭新強(通訊作者),香港中文大學教育行政與政策學系教授 電子郵件:nskpang@cuhk.edu.hk 王婷,澳洲坎培拉大學國際教育領導及發展學系教授 電子郵件:ting.wang@canberra.edu.au 投稿日期:2016 年 5 月 29 日;修正日期:2016 年 7 月 28 日;接受日期:2017 年 1 月 11 日研究發現或結論 主要研究結果顯示,與營運教育機構相比,教育領袖在個人層 面上更推崇集體主義、人文主義和自我修養這三個方面。而有趣的 是,等級關係是機構所擁護的最重要的價值,卻同時是最不受個人 所青睞的價值。 研究原創性/價值性 透過探索現有儒家倫理和領導實踐中之價值,本研究揭示了在 中國文化背景下教育領導在促進生產、效能和績效方面的職能; 以及 推動了教育領導與效能研究領域的發展。 關鍵字: 領導培訓、領導策略、儒家思想、價值取向、跨國課程、 倫理與價值、中國文化

INVESTIGATING CHINESE EDUCATIONAL

LEADERS’ CONFUCIAN ETHICS AND VALUE

ORIENTATIONS IN A TRANSNATIONAL

LEADERSHIP PROGRAM

Nicholas Sun-Keung Pang Ting Wang

ABSTRACT

PurposeScant empirical research has explored the perceived practices of Confucian ethics and values in educational management and leadership in China. Based on a conceptual framework, this study compared the personal values of a group of Chinese educational leaders and those espoused by their working institutions. This study aimed to determine whether the Confucian ethics and values of hierarchical relationships, collectivism, humanism, and self- cultivation continue to be emphasized in contemporary Chinese educational institutions.

Design/methodology/approach

A standardized instrument, the Institutional Values Inventory, with 53 value statements, was used to assess educational leaders’ value orientations in their respective institutions. The subjects of the study were a group of 67 Chinese educational leaders enrolled in an Australian transnational leadership program in Zhejiang Province, China.

Nicholas Sun-Keung Pang (corresponding author), Professor, Department of Educational Administration and Policy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. E-mail: nskpang@cuhk.edu.hk

Ting Wang, Professor, Department of International Education, Leadership and Development, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia.

E-mail: ting.wang@canberra.edu.au

Findings

The major findings show that the educational leaders had a higher regard for collectivism, humanism, and self-cultivation than their institutions in how an education institution should be operated. Interestingly, hierarchical relationship was the most important institutionally espoused value which also constituted the least favored value held by the individual educational leaders.

Originality/value

This study sheds light on leadership roles in enhancing productivity, effectiveness, and performance, and contributes to the field of educational leadership and effectiveness research through exploring the existence of Confucian ethics and values in leadership practices, especially in Chinese cultural contexts.

Keywords: leadership preparation, leadership strategy,

Confucianism, value orientation, transnational program, ethics and values, Chinese culture

Introduction

Globalization refers to a complicated set of economic, political, and cultural factors that is transforming the lives of people all around the world, whether in the developed or developing countries. The process of globalization is seen as blurring national boundaries, shifting solidarities within and between nation-states, and deeply affecting the constitution of national and other interest group identities (Morrow & Torres, 2000). As a result of expanding world trade, nations and individuals experience greater economic and political interdependence (Wells, Carnochan, Slayton, Allen, & Vasudeva, 1998). Globalization is driving a revolution in the organization of work, the production of goods and services, relations among nations, and local cultures (Pang, 2006).

In this increasingly competitive global economy and environment, nation- states have to adjust themselves to become more efficient, productive, and flexible. To enhance a nation’s productivity and competitiveness in the global situation, education has been restructured using the two major strategies, decentralization and creation of a ‘market’ in education (Lingard, 2000; Mok & Welch, 2003). Specifically, decentralization and corporate managerialism have been utilized by most governments to increase labor flexibility and create more autonomous educational institutions while catering for the demand for more choices and diversities in education (Blackmore, 2000).

The Impacts of Globalization on Education

Increasing evidence suggests that globalization has brought a significant paradigm shift in educational management, administration, and governance in many countries (AACSB International, 2011). Mulford (2002) observes that there has been a shift from the traditional values of wisdom, trust, empathy, compassion, grace, and honesty in managing education to the values of contracts, markets, choice, and competition in educational administration. Nowadays education administrators tend to put more emphasis on instrumental skills of efficiency, accountability and planning than skills of collaboration and reciprocity.

A variety of significant social, cultural, economic, and political forces are also linked to the global development of higher education. Schugurensky (2003) identified the globalization of the economy, the ‘commodification’ of knowledge, and the retrenchment of the welfare state as three important forces, among others, for the changes in higher education. Globalization leads to the

emergence of a knowledge economy, in which the importance of information technology and knowledge management is coming to outweigh that of capital and labor. Globalization also leads to the intensification of transnational flows of information, commodities, and capital around the globe. That renders both production and dissemination of knowledge increasingly commodified. More and more welfare states have adopted a neoliberal ideology geared to promoting economic international competitiveness. All these forces are implicit in a restructuring of higher education systems worldwide (Peters, Marshall, & Fitzsimons, 2000).

The impacts of these forces on the change to higher education are manifest in the drastic restructuring of higher education systems, in which values such as accountability, competitiveness, devolution, value for money, cost effectiveness, corporate management, quality assurance, performance indicators, and privatization are emphasized (Mok & Lee, 2002; Ngok & Kwong, 2003). Though nations vary widely in their social, political, cultural and economic characteristics, what is striking is the similarity and convergence in the unprecedented scope and depth of restructuring taking place. In general, most of these changes are expressions of a greater influence by the market and the government over the university system. At the core of these changes is a redefinition of the relationships among the various entities, university, the state, and the market (Schugurensky, 2003).

Likewise, many nations around the world are undertaking wide-ranging reforms of curriculum, instruction, and assessment in their school education systems to prepare students for increasingly complex demands of life and work and to develop the ability to compete effectively in a knowledge-based economy (Pang & Wang, 2016). Though different states may adopt different strategies in school reforms, strategies similar to those apparent in restructuring higher education, namely decentralization, marketization and choice appear to be the major approaches (Pang, 2006). Decentralization is cast in the role of a reform that increases productivity in education and thus contributes significantly to improving the quality of a nation’s human resources. Many approaches have been adopted to achieve decentralization of school education, such as zero-based budgeting, school consultative committees and school-based management (Advisory Committee on School- based Management, 2000). When there is a market mechanism in the education system, schools are responsive and accountable. The right choice, then, is to devolve the system to schools. When the functions of market and

school-based management in schools are at full strength, it is believed that the quality of education will be assured. The prevailing performance discourse in education claims school improvement can be achieved through transparent accountability procedures. Accountability has become a core concept under educational reforms in the age of neoliberal governance, which emphasizes devolution, performativity, productivity, efficiency, and effectiveness (Pang, 2016; Ranson, 2003; Wang, 2016; Webb, 2006).

Under the impacts of globalization, educators are confronted with sets of conflicting values and dilemmas in the choice of traditional values and modern values brought by globalization. They are facing the challenges of choosing the appropriate values and ethics in determining their thinking and actions in the highly competitive world. Educators in various Chinese societies are no exception. They need to cope with the challenges when their societies are open to globalization and their traditional cultures and values meet with new ideologies brought along with globalization.

Leadership in Chinese Culture and Traditions

The concept of culture has become increasingly important in the discourse of educational leadership and management. Many writers have argued for a comparative cross-cultural perspective where the influence of societal culture upon educational administration is researched and compared across societies and cultures. Wider exposure to non-Western knowledge and practices, in Western and non-western education systems, can add richness to our understandings through alternative ways of thinking and working. Researchers suggest that a culturally and contextually sensitive approach to the study of educational leadership is needed (Hallinger & Kantamara, 2000; Walker, Hu, & Qian, 2012).

An array of scholars has investigated Chinese culture and leadership traditions. Chinese culture, like other great cultures of the world, is rich in history and content. Huang (1988) argued that Chinese culture and values have remained consistent throughout much of its history. Many scholars (e.g., Chen, 1995; Seagrave, 1995; Wong, 2001) suggest that there are certain historical-social influences on the development of management and leadership practice in China, such as Taoism, Confucianism and the strategic thinking of Sun Tzu. Of these, Confucianism became a structure of ethical precepts for the management of society based upon the achievement of social harmony and

more detail below. It can be seen that Chinese cultural, historical and social contexts have had a greater impact upon leadership traditions in China. Respect for hierarchy, maintaining harmony, conflict avoidance, collectivism, ‘face’, social networks, moral leadership, and conformity are key influential values.

Leadership is acknowledged as a value-laden concept (Gronn, 2001; Sergiovanni, 2001), regarded as culturally complex and context dependent with leadership traditions and conceptions influenced by different elements of culture and forces (Wang, 2011). Bush and Qiang (2000) have argued that the diversity and complexity of Chinese culture, which is currently a mixture of traditional, socialist, enterprise, and patriarchal cultures, is reflected in the Chinese education system. The impact of cultural values is captured in what Gordon (2002) refers to as deep leadership structures. Deep structures are the non-tangible, less readily identifiable values that lurk unseen everywhere in peoples’ cognition and within organizations. Thus, these four major elements of contemporary Chinese culture shape educational leadership, which is overwhelmingly male, with a balance between hierarchy and collectivism. Given the historical construction of deep structures, they are hardy and resistant to change or challenge. While they are capable of adjustment, if it does happen, it tends to be slow to take hold (Wang, 2011). The traditional conceptions of leadership in China are mostly associated with a directive, hierarchical and authoritarian headship, together with an emphasis on moral leadership, self-cultivation, and artistry in leading. Although the emergence of enterprise culture and market socialism seems to be slowly changing the nature of Chinese contemporary culture and social values, such cultural change is unlikely to be radical and transformational, given the cumulative and enduring nature of the indigenous culture. Consequently, an incremental cultural change is expected in Chinese education in the long run. There arises a need to understand the influences of Confucian values and ethics on contemporary leadership in the changing contexts.

Confucian Values and Ethics in Chinese Leadership

Confucianism, established more than 2000 years ago in Ancient China, has been a vast, interconnected system of philosophies, rituals, habits and practices that still informs the lives of millions of people today in Chinese societies (J. H. Berthrong & E. M. Berthrong, 2000). It is a philosophical system of ethics, values and moral precepts to provide the foundation for a

stable and orderly society and the guidance for ways of life for most Chinese people (Erdener, 1997). In Chinese history, there has been a long tradition of using Confucianism as the principle of governmental and educational systems to justify the sovereign’s power and to keep their political and economic privileges (Lee, 1997). Confucianism still has profound influences on all aspects of human life in art, education, morality, religion, family life, science, philosophy, government, management and the economy (Bell, 2008).

Confucianism as a philosophy and ideology is predominantly humanist, collectivist and hierarchical in nature. This is reflected in its profound interest in human affairs and relations. These moral and political value systems are essential philosophical factors of self-cultivation, family-regulation, social harmony, and political doctrine (Lee, 1997; Stambach, 2014). Confucius aimed to teach about the wisdom of the former sages towards reforming society with a humanistic ideology. Confucius’ moral principles are largely in two directions: Building the ideal life of individuals, and achieving the ideal social order (Lee, 1997, p. 141). To achieve these principles, Confucius conceived benevolence or humanity (in Chinese, ren 仁 ) as the major paradigm of goodness, with sub-paradigms like righteousness (in Chinese, yi 義), rites (li 禮), wisdom (ji 智), loyalty (chung 忠), filial piety (hsiao 孝), trust (shin 信).

In prescribing human relations, the virtues of ren-yi-li stand out. The enterprise of Confucian ethics has been built on the ren-yi-li normative values. This represents the overarching moral framework which defines and sustains morally and socially acceptable behaviors and attitudes. Ren refers to humaneness or a capacity to act with utmost benevolence and love. The practice of ren helps to constitute a web of desirable norms for personal and social behavior (Ip, 1996; Li, 2008). The concept of yi means moral rightness and appropriateness and is prescribed as a moral norm for conduct and decisions. With regard to li, this represents the etiquettes, norms and mores and protocols in both daily and institutional life (Ip, 1996). Widely accepted in the Chinese culture, the ren-yi-li normative structure has provided an elaborative set of norms and moral directives governing and dictating conducts and attitudes in different aspects of individual’s personal life and interpersonal relationships.

Confucius also aimed to reform society with an advocacy of collectivism. Confucius’ collectivism is vividly displayed in its emphasis on collective values and interests rather than individual values and interests. The family as

the archetype of the collectivity occupies the core position within Confucian ethics and values. With two thousand years of evolution, the emphasis of collectivism in the Chinese culture goes far beyond the familial collectivism, extending to institutional and national relationships (Ip, 1996).

In addition to humanism and collectivism, Confucianism also provokes a fundamental core belief in the hierarchical ordering of personal relationships (Erdener, 1997). On a broader scale, there were five basic human relationships as conceived by Confucianism—the mutual relationship of the Five Codes of Ethics or Five Relationships. The five relationships: Emperor-officials; father- son; brother-brother; husband-wife and between friends, with the exception of the last one, all exhibited a strong superordinate-subordinate relationship (Ip, 1996). This acceptance of unequal relationships in society reflects the underlying model of relationships found in the traditional Chinese family between father and son, in business enterprise between employer and employee and in the government between senior and junior officials. All these underscore the fundamental importance of personal relationships in the Confucian cultures and societies.

In order to build the ideal life of the individual and achieve the ideal social order, Confucius asserts that education makes it possible for an individual to live the good life in the community and state. Accordingly, moral cultivation is a core educational goal (Lee, 1997; Gardner, 2014). What follows is the basic teaching of how man should relate himself to the social groupings and society that surround him. Within the Confucian moral edifice, the closest text from which one can obtain a notion of civility of the person is

the Great Learning (大學). In Confucius’ words, those who wished to bring

order to their states would first regulate their families; those who wished to regulate their families would first cultivate their personal lives; those who wished to cultivate their personal lives would first rectify their minds; those who wished to rectify their minds would first make their wills sincere (Ip, 1996; Littlejohn, 2011). Achieving the goal of self-moral cultivation is the single most fundamental human endeavor of a person’s life and only by achieving this goal will the person be able to regulate the family, govern the state, and rule the world (修身、齊家、治國、平天下).

Based on a review of the literature, the researchers conclude that the core traditional values and ethics underpinning Chinese educational leadership are hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism, and self-cultivation. Therefore, they developed a theoretical framework in this study for assessing

the extent to which these traditional values are espoused by educational leaders in different contexts. The meanings of four scales of Confucian ethics and values in the context of educational institutions in China are briefly defined as below.

Hierarchical relationship refers to the hierarchical and organizational structures in an institution built to facilitate and enhance the achievement of goals.

Collectivism refers to the strategies in managing an institution that facilitate the development of a collective culture.

Humanism refers to the ways in which administrators build a reciprocal understanding among people and work to enhance respect for employees.

Self-cultivation refers to the value system that leads to the development of individuals’ full potentials and their ethical spirits and moral standards.

Research Methodology

Research Aims

When values are at the heart of educational management and administration, they are the central elements of educational leadership. When values are the forces that bind an institution together, values appear to be a measurable, testable and verifiable construct of educational leadership. There is a scarcity of empirical research that has explored perceived practices of Confucian ethics and values in educational management and leadership in China (Lee & Pang, 2011). Based on a conceptual framework of Confucian ethics and values developed for this study, the present research examined a group of Chinese educational leaders’ personal values and values that are espoused by their working institutions in daily management and administration. This study attempts to understand the relationships between leaders’ personal values in theory and institutions’ espoused values in practice. It aims to investigate the value orientations of educational leaders in different sectors, and to examine whether Confucian ethics and values of hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism, and self-cultivation continue to be emphasized in contemporary Chinese educational institutions.

Research Instrument

A standardized instrument, the Institutional Values Inventory (IVI), was developed to assess educational leaders’ value orientations in their respective institutions. The development of the original measures was made following an extensive literature review and with a particular focus on administrative values and ethics within institutions. Eight subscales of institutional values were hypothesized as indicators of Confucian ethics and values of hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism, and self-cultivation. The practice of formality and bureaucratic control are indicators of Confucian ethics and values of hierarchical relationship among people within educational organizations; participation, collaboration and collegiality are indicators of Confucian values of collectivism; goals orientation, communication and consensus are indicators of Confucian values of humanism; and professional orientation and employee autonomy are indicators of Confucian values of self- cultivation.

Participants

The participants of the study were a group of 67 Chinese educational leaders who were enrolled in an Australian transnational leadership program in Zhejiang Province, China, in 2011. The backgrounds of the participants were diverse in terms of work experience, age, rank and position. Most of them held leading positions in their institutions, including principals and senior teachers in primary and secondary schools, directors and unit heads in the local education system, professors, lecturers and administrators in the higher education sector. This Master in Educational Leadership program commenced in 2001 and has graduated over 400 students. It was delivered in a co-teaching and bilingual flexible mode in three intensive teaching brackets of six core subjects over twelve months. Australian academics undertook responsibility for the development and intensive delivery of the course and for marking/moderating assessment with the assistance of local co-teachers. Chinese academics were also utilized as translators of course materials, tutors in the classes, providers of support for students to complete assignments after the intensive phase. Course materials were primarily of Western origin and translated into Chinese, but some materials were drawn from Chinese sources and relevant cross-cultural studies. Teaching approaches were culturally sensitive, dialogue-based, participatory, and linked to constructivist theories of learning. This program has had considerable, positive impact on

educational leadership development in the region and received positive feedback consistently from external reviews.

The Intercultural Dialogue (ICD) Framework for Transnational Teaching and Learning has been utilized in this transnational leadership program to challenge students to critically examine Western education and leadership ideas in the Chinese context and develop high level critical thinking skills and intercultural competencies. The intercultural dialogue framework comprises five key components: Understanding of learners and contexts, culturally sensitive pedagogy, contextualized curriculum, context-specific assessment, and supportive learning environment (Wang, 2016).

Data Collection and Analysis

A questionnaire, the Institutional Values Inventory (IVI), with 53 values statements, was developed for the study. The participants were asked to rate the value statements on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 ‘Very Dissimilar’ to 6 ‘Very Similar.’ The IVI was designed to assess the administrative practices and managerial values that were espoused by the participants and the institutions, and the degree to which the two groups shared these values. The values in this study are defined as ‘taken-for-granted beliefs about the proper functioning of a school.’ They may mean ‘the ways we do things here,’ ‘what ought to be,’ and ‘the ways by which a school should be operated.’

Participants were asked to rate the value statements twice, first on the similarity between their own values and the value statements and then on the similarity between the institutions’ espoused values in daily managerial practices and the value statements. Rating the value statements on the similarity between their own values and the value statements gave rise to the dimension of leaders’ personal values (LPVs). Rating the value statements on the similarity between the institutions’ espoused values in daily managerial practices and the value statements showed the dimension of institutions’ espoused values (IEVs). The differences between the LPVs and IEVs would then become a measure of the divergence in values between participants and the institutions in terms of the eight subscales of institutional values and orientations.

Principal Component Analyses

The IVI was found to be valid and reliable instrument. Literature was the primary source of inspiration for the content areas covered by the value

statements. Principal component analysis (PCA) with oblique rotations was the method used to select the appropriate value statements (the institution’s espoused values—IEVs) for forming the major scales of Confucian ethics and values. Only the IEVs statements and ratings were used in the Principal component analyses, because IEVs statements would be more objective and measurable, while the leaders’ personal values (LPVs) statements would be more subjectively and personally biased. Four Principal component analyses, each requesting a single order factor, were done to confirm the existence of the hypothesized scales of the IVI, including hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism and self-cultivation. The results of the four PCA analyses are showed in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4, which indicate the construct validity of the instrument, IVI, and the related value statements and subscales forming the four major scales of Confucian ethics and values.

Table 1

Factor Loadings of Principal Component Analysis with Oblique Rotation for the Scale, Hierarchical Relationship, of Institutions’ Espoused Values (IEVs)

Component

Item No. 1 2

64. Employees should be regularly checked to prevent them from wrong doing. 0.812 0.010

73. Rules stating when employees should arrive and depart should be strictly enforced. 0.741 0.061

91. Leaders should check and supervise subordinates’ work. 0.724 0.040 63. A well-established system of super-ordination and subordination should be developed 0.666 0.062 55. Quality education is a management problem that should be solved by tight controls. 0.652 0.182

90. Little action should be taken until decisions are approved by senior authority. 0.268 0.856

54. Employees should seek permission from higher up before action. 0.262 0.616

72. A good employee should be one who conforms to accepted standards in the institution. 0.197 0.611

81. The same procedure for like situations should be followed at all times. 0.284 0.526

Eigenvalue 3.700 1.187

% of Variance Explained 41.12 13.192

Note. (1) Principal component analysis and oblique rotation were used in the factor extraction. (2) Salient variables are those with factor loadings greater than 0.3 in absolute value.

(3) Based on the meanings of the grouped items, Component 1 is named ‘Formality’ and Component 2 as ‘Bureaucratic Control’.

(4) The item-to-subject ratio for the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale, Hierarchical Relationship, is 1:7.44 (9:67).

Table 2

Factor Loadings of Principal Component Analysis with Oblique Rotation for the Scale, Collectivism, of Institutions’ Espoused Values (IEVs)

Component

Item No. 1 2

57. Employees and leaders should provide constructive feedback to each other regularly. 0.938 0.146 66. Active employee participation at staff meetings should be encouraged. 0.872 0.093 65. Every employee should have a share in the planning for the future direction. 0.815 0.006

56. Employees should have participation in decision making. 0.692 0.087

93. Employees should always meet together to share their knowledge and experiences. 0.594 0.180

84. Employees should meet on a regular basis to learn together. 0.562 0.226

104. The institution should protect employees from the problems of limited time and excessive paperwork. 0.147 0.830

100. Employees of different ranking should be treated equally. 0.035 0.829

74.

Both employees and the leader should be partners, rather than super-ordinates and sub-ordinates, who work together.

0.126 0.763

75. All employees should be involved in deliberating on institution’s goals. 0.223 0.614

Eigenvalue 4.744 1.453

% of Variance Explained 47.44 14.53

Note. (1) Principal component analysis and oblique rotation were used in the factor extraction. (2) Salient variables are those with factor loadings greater than 0.3 in absolute value.

(3) Based on the meanings of the grouped items, Component 1 is named ‘Participation and Collaboration’ and Component 2 as ‘Collegiality’.

(4) The item-to-subject ratio of the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale, Collectivism, is 1: 6.70 (10: 67).

Case-to-Variable Ratio

As factor analysis and multivariate analysis of variance were employed in subsequent data analyses, the cases to variables ratios in the hypothesized scales should reach a certain level to achieve reliable results. Different techniques in statistical analysis require different cases to variables ratios as a minimum pre-requisite and different experienced quantitative researchers suggest different ratios as the satisfactory levels. Tabachnick and Fidell (1989, p. 603) suggested a ratio of at least five cases for each observed variable as the acceptable level for factor analysis of a scale. Cattell (1978) recommended that a ratio of at least 4:1 was desirable for factor analysis. Tables 1, 2, 3, and

4 show that the obtained cases to variables ratios of the hypothesized scales ranged from 5.15 to 7.44. The minimum criteria for the statistical analyses had, therefore, been achieved.

Table 3

Factor Loadings of Principal Component Analysis with Oblique Rotation for the Scale, Humanism, of Institutions’ Espoused Values (IEVs)

Component

Item No. 1 2

67. Contributions by employees should be rewarded. 0.864 0.215 70. Employees should be encouraged to work hard and be reinforced for doing so. 0.797 0.001 71. Excellent performance by employees should be recognized. 0.769 0.063

58.

When an important decision has been made without consulting opinions of teachers, the leader should always explain the reasons behind.

0.727 0.045

62. The leader should keep an open-door policy to facilitate employees coming to him/her for problem

solving. 0.663

0.271

61. Both employees and leaders should have an agreement on the institution’s goals, purposes and

mission. 0.619

0.069

88. Different plans and policies made by departments should work towards the institution’s goals. 0.535 0.034

103.

A work plan which gives an overview of the institution’s goals should be written down in the

administrative handbook for easy reference. 0.126

0.798

97. Leaders should coordinate all the work to ensure that they all work towards the institution’s goals. 0.160 0.771

79. At the beginning of the year, the institution’s general goals should be explained to the new employees.

0.085 0.680

76. Leaders should make themselves visible and approachable around the institution. 0.224 0.659

80. A new measure should not be implemented, unless most employees agree with it. 0.156 0.652

94. Employees should be kept well informed on matters of importance to them. 0.193 0.614

Eigenvalue 5.218 1.872

% of Variance Explained 40.14 14.40

Note. (1) Principal component analysis and oblique rotation were used in the factor extraction. (2) Salient variables are those with factor loadings greater than 0.3 in absolute value.

(3) Based on the meanings of the grouped items, Component 1 is named ‘Communication and Consensus’ and Component 2 as ‘Goal Orientation’.

(4) The item-to-subject ratio of the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale, Humanism, is 1: 5.15 (13:67).

Table 4

Factor Loadings of Principal Component Analysis with Oblique Rotation for the scale, Self-cultivation, of institutions’ espoused values (IEVs)

Component

Item No. 1 2

105.

Leaders should encourage employees to evaluate their own performance and set goals for their own

growth. .782 .138

86. Employees should be encouraged to develop themselves professionally. .714 .126 69.

The organizational structure should give

considerable autonomy to the departments within the institution.

.672 .140 101. Employees should be responsible for their own quality of work. .585 .159

68. Employees should be allowed to work within their own professional abilities. .550 .098 59. Employees should be a highly trained and dedicated group of professionals. .497 .193 78. Employees should be allowed to work independently without supervision. .173 .897 102. Employees should have the rights to work in a free environment. .008 .845 96. Leaders should allow employees to engage in a variety of practices freely. .252 .769 106. Employees should have the rights to engage in a variety of practices in the institution. .110 .705

Eigenvalue 3.761 1.693

% of Variance Explained 37.61 16.93

Note. (1) Principal component analysis and oblique rotation were used in the factor extraction. (2) Salient variables are those with factor loadings greater than 0.3 in absolute value.

(3) Based on the meanings of the grouped items, Component 1 is named ‘Professional Orientation’ and Component 2 as ‘Employee Autonomy’.

(4) The item-to-subject ratio of the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale, Self-cultivation, is 1: 6.70 (10:67).

Framework for Confucian Ethics and Values in Educational Management

Based on a proposed framework for Confucian ethics and values in educational management as described in previous sections and the Institutional Values Inventory (IVI), attempts were made to determine if the four Confucian ethics and values existed in terms of hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism and self-cultivation. In the high-order factor analysis, an indicator (subscales of the IVI) with greater factor loading would contribute to a composite more than an indicator with smaller factor loading. The overall structures of the high-order factors show that the contents of the primary factors contributed and subsumed respectively to the overall

meanings of the composites that they loaded onto. The meanings of the Confucian ethics and values in the Chinese context are defined as below.

Hierarchical relationship refers to the hierarchical and organizational structures built to facilitate and enhance the achievement of institutional goals. The institution is perceived to have a well-established system of superordinate-subordinate relationships. The institution emphasizes the disciplined compliance to directives from superiors that are necessary for implementing the various tasks and functions of the institution. The indicators for hierarchical relationship in an institution are formality and bureaucratic control.

Collectivism refers to the strategies for managing an institution that facilitate the development of a collective culture. The indicators for collectivism are participation, collaboration, and collegiality. They are the crucial strategies for creating strong collective cultures in institutions. The institution that has strong collectivism is perceived to have a high spirit of cooperation between employees and administrators. The sharing of leadership and decision-making is emphasized.

Humanism refers to the ways in which educational administrators have been adopting strategies to build a reciprocal understanding among people and to enhance respect for employees. Through these means, educational administrators intend to bind employees to the goals, visions and philosophy of the institution. A second-order factor indicates that goal orientation, communication, and consensus are the important ways to drive employees to the institution’s core values and to create coherence of efforts by a humanistic approach.

Self-cultivation refers to the value system that leads to the development of individuals’ full potentials and their ethical spirits and moral standards. A second-order factor indicates that employee autonomy and professionalism are the basic principles of cultural norms that allow people to rectify their minds, make their wills sincere, and cultivate their personal lives in the workplace. These are also the effective strategies for those who aim to achieve the goal of self-moral cultivation.

Findings and Discussions

Demographic Backgrounds of the Educational Leaders

The demographic characteristics of participants in this study are outlined in Table 5. Through convenience sampling, a total of 67 participants, who

served in leadership positions in various institutions and enrolled in the transnational program of educational leadership, were invited to complete the survey. A total of 30 out of 67 participants were male, and 37 were female. Of the 67 participants, nearly 68.6% of them (n 45) were under the age of 35 years old. Most participants (n 57) worked in three major sectors of educational administration, policy and leadership. There were 25 participants from the school sector, 21 from the education bureau, and 11 from the higher education institutions. Among the 25 participants from the school sector, seven were school principals, three were vice-principals, eight were senior teachers in the administrative positions, and seven were junior teachers. Of the 21 participants from the education bureau, one was a director of a local bureau, two were division heads, while 18 of them were section heads. Of the 11 participants from the higher education institutions, two were associate professors, while nine were lectures. There were about 14.9% of the participants (n 10) from institutions other than schools, bureaus and higher education institutions. Most participants had been serving their institutions about 9.2 years and serving in their present positions for 5.6 years. In sum, the demographic information shows that most participants served at leadership positions in various institutions in terms of education administration, policy and development, and they were at the stage of leadership development and enhancement via participation in the transnational educational leadership program.

Educational Leaders’ Administrative Practices across Institutions

The descriptive statistics and the reliability coefficients of the eight subscales of administrative practices within institutions are shown in Table 6. The final version of the IVI consisted of 42 value statements concerning how an institution should be operated in eight confirmed first-order scales: Formality ( .79), Bureaucratic Control ( .66), Participation and Collaboration ( .87), Collegiality ( .80), Goal Orientation ( .82), Communication and Consensus ( .86), Professional Orientation ( .73) and Employee Autonomy ( .85), with the scale reliability coefficients (Alphas) enclosed within brackets. The results show that the subscales have good reliabilities in general, except for bureaucratic control, to assess the administrative practices across different educational institutions, say, schools, education bureaus, and higher education institutions. The findings from the survey show that the practices of communication, getting consensus, and

enhancing professional orientation among employees were generally emphasized, while the practices of formality and bureaucratic control were also highly stressed. While the administrative practices of participation, collaboration, goal orientation were moderately stressed, enhancing collegiality and employee autonomy were the least emphasized.

Table 5

Summary of Demographic Characteristics of Educational Leaders

Demographic

Items Category Respondents

N % 1. Sex Male Female Missing Values 30 37 0 44.8 55.2 0 2. Age 25-30 years 31-35 years 36-40 years 41-45 years 46-50 years Above 50 years Missing Values 25 21 7 8 6 0 0 37.3 31.3 10.4 11.9 9.0 0 0 3. Working institutions School Sector Education Bureau Higher Education Sector Others Missing Values 25 21 11 10 0 37.3 31.3 16.4 14.9 0 4. Working Position 4.1 School Sector Principal Vice principal Senior Teacher Junior Teacher 7 3 8 7 10.4 3.9 11.9 10.4 4.2 Education Bureau Director Division Head Section Head 1 2 18 1.5 3.0 26.9

4.3 Higher Education Sector

Professor Associate Professor Lecturer 0 2 9 0 3.0 13.4 5.Serving years in the

present institution M 9.20; SD 6.63; N 66 (Missing Value n 1) 6.Serving years in the

present position M 5.59; SD 4.48; N 66 (Missing Value n 1) Note. Total no. of educational leaders in the sampleis 67.

Table 6

Summary of Reliability Coefficients (), Means and Standard Deviations of the Subscale of

the Institutions’ Espoused Values (IEVs)

Subscale No. of Items M SD N

Formality 5 0.79 4.59 0.83 67

Bureaucratic Control 4 0.66 4.54 0.80 67

Participation and Collaboration 6 0.87 4.46 0.86 67

Collegiality 4 0.80 4.11 1.06 67

Goal Orientation 6 0.82 4.47 0.85 67

Communication and Consensus 7 0.86 4.62 0.79 67 Professional Orientation 6 0.73 4.68 0.69 67

Employee Autonomy 4 0.85 3.98 1.08 67

Total no. of items 42

Table 7 shows the correlation coefficients among the eight subscales of administrative practices in these institutions. The results show that the practices of formality and bureaucratic control are significantly and positively associated, while the practices of bureaucratic control would be negatively associated with the practices of participation, collaboration, collegiality, and enhancing employee autonomy in the workplace. It implies that leaders should be cautious about the use of bureaucratic control in the workplace, which would create hindrance to positive relationships between leaders and employees. Further findings from the significant and positive correlations among other subscales show that the practices of participation, collaboration, collegiality, goal orientation, enhancing communication and consensus, driving to professional orientation and enhancing employee autonomy should be more emphasized, because these practices would have a positive reinforcement to each other in enhancing positive cultures within these institutions.

Educational Leaders’ Emphases on Confucian Ethics and Values

Based on a proposed framework for Confucian ethics and values in educational institutions and the Institutional Values Inventory (IVI), attempts were made to determine if the four major scales of Confucian ethics and values empirically existed (i.e., Hierarchical Relationship, Collectivism, Humanism, and Self-cultivation), and to examine to what extent they were emphasized in the daily administrative practices of these institutions. With

Table 7

Summary of Correlations of the Subscale of Institutions’ Espoused Values (IEVs)

FormalityBureaucratic Control Participation and Collaboration Collegiality Goal Orientation Communication and Consensus Professional Orientation Employee Autonomy Formality 1 Bureaucratic Control .495 ** 1 Participation and Collaboration .044 .266 * 1 Collegiality .197 .383** .518** 1 Goal Orientation .051 .239 .528** .780** 1 Communication and Consensus .152 .150 .826** .409** .513** 1 Professional Orientation .237 .149 .765** .456** .639** .810** 1 Employee Autonomy .212 .357** .400** .713** .736** .310* .395** 1 Note. * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Listwise N 67

empirical data collected from 67 participants in a transnational program of educational leadership in Zhejiang Province, the validity of the framework and reliabilities of the subscales were established. Then further analyses were done in this study to explore the relationships amongst the four major

Confucian ethics and values scales that existed in the institutions under study.

After having developed the eight subscales of administrative practice to ensure their reliability and validity, LISREL confirmatory factor analytic modeling techniques using the PRELIS 2 and LISREL 8 computer programs (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993) were utilized to analyze the data and to test whether the two subscales of respective major scale would form a coherent latent construct. A hypothetical model of latent construct with the two indicator variables (X1 to X2) loaded on only one latent factor (1) was

proposed and tested for each of the four major scales of Confucian ethics and values in administration and leadership. The confirmed high order factors with the estimated factor scores regressions were then used to compute the composite scores of the major scales from the two indicator variables. With such composite scores, further analyses were attempted to answer the research questions.

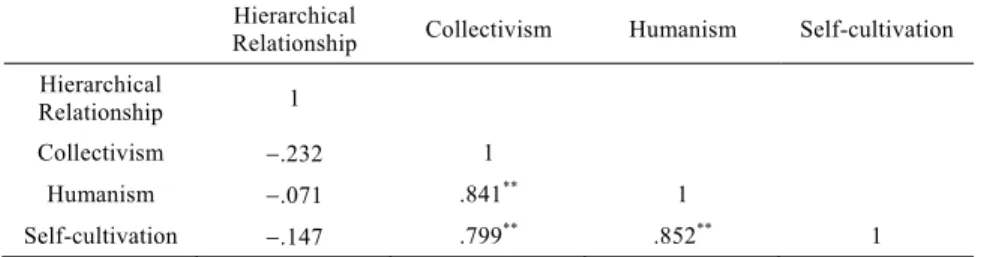

Table 8 shows the correlation coefficients among the four major scales of Confucian ethics and values in the daily managerial and administrative practices in these institutions. The results show that the emphases on collectivism, humanism, and self-cultivation of the employees by educational leaders were significantly and positively associated. However, the emphasis on hierarchical relationship within these institutions has no significant correlations with the emphases on collectivism, humanism and self-cultivation. It implies that while leaders’ stress on hierarchical relationship within an institution may have no direct association with their emphases on collectivism, humanism and self-cultivation, at least such practices are not mutually exclusive or negatively related.

Table 8

Summary of Correlations of the Scales of Institutions’ Espoused Values (IEVs)

Hierarchical

Relationship Collectivism Humanism Self-cultivation Hierarchical

Relationship 1

Collectivism .232 1

Humanism .071 .841** 1

Self-cultivation .147 .799** .852** 1

Note. * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Listwise N 67

Educational Leaders’ Value Orientations in Zhejiang Province, China

The study explored the value orientations of a group of educational leaders in China and examined whether Confucian ethics and values of hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism and self-cultivation continue to be emphasized in educational leadership and management in the contemporary Chinese context. The four major scales of Confucian ethics and values were assessed in terms of eight subscales of value orientations that were espoused by the institutions in daily managerial practices (Institutions’ Espoused Values, IEVs) and that were held and stressed by participants in their personal beliefs and values (Leaders’ Personal Values, LPVs). Assessments were also made by examining the value differences between IEVs and LPVs, which gave the values of Values Divergence (VD). Participants from three different sectors (schools, education bureaus, and

higher education institutions) were invited to give responses to the IVI. The results of the assessments gave three profiles for all the participants: The IEV profile, LPV profile and VD profile. The results of the quantitative assessments are shown in the following two figures.

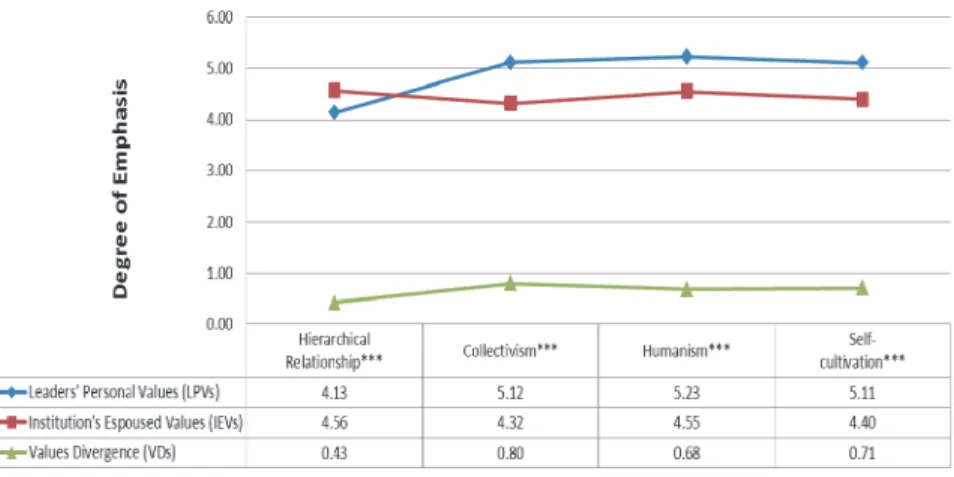

Figure 1 reveals the value orientations of this group of educational leaders in terms of their personal values (LPVs), values espoused by their institutions (IEVs) and the values divergence (VD). It should be noted that three scales of LPVs consistently rated higher than those of IEVs, except in the scale of hierarchical relationship. This finding suggests that participants had greater preferences than their institutions for collectivism (Participation and Collaboration, Collegiality), humanism (Goal Orientation, Communication and Consensus), and self-cultivation (Professional Orientation and Employee Autonomy). They appeared to have lower preferences for Formality and Bureaucratic Control and wished to downplay traditional Confucian values of hierarchical relationship in their institutions.

The findings also show that participants had a higher regard for collectivism, humanism, and self-cultivation than their institutions in terms of the ways an education institution should be operated. Interestingly, hierarchical relationship was the most important institution espoused value which was also the least favored value held by individuals. In a similar vein, collectivism which was highly valued by individuals received lowest attention from institutions. This may result from a confrontation between the existing bureaucratic culture and the emerging democratic culture and participation in Chinese educational institutions, with the former favoring political and systemic interests, and the latter stressing the interests and desires of people working in and for institutions. Yet, it remains to be explored whether these Confucian values are in line or in conflict with modern values of competition, efficiency and accountability.

Figure 1. Values orientation of 67 educational leaders in the master program of educational

leadership in Zhejiang Province, China

( indicates significant difference at 0.001 level in T-tests between LPVs and IEVs)

The profile of value divergence indicates the gaps between leaders’ personal values and institutional espoused values. The bigger the gaps, the greater were the divergences in these values. The smaller the gaps, the greater were the extent to which these values were shared between leaders and the institutions. The value divergences in collectivism, humanism and self- cultivation were greater in extent than hierarchical relationship. It is interesting to note that the value divergence in hierarchical relationship was the smallest, which was the least favored by individuals and most preferred by institutions among the four Confucian ethics. A possible explanation is that personal value of hierarchical relationship continues to be accepted and compatible to the value espoused by the institutions. The rapidly changing contexts and fluidity of cultural values under the impacts of globalization may explain such narrowing gap in Chinese educational institutions.

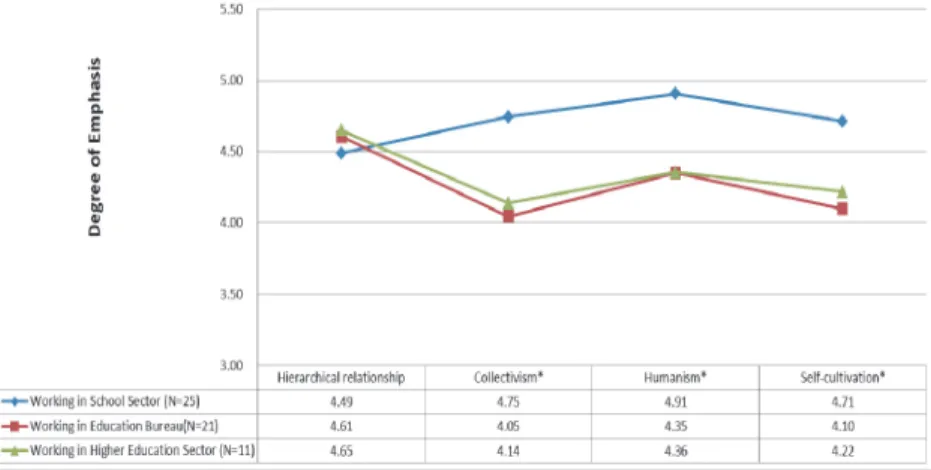

Figure 2 reveals the profiles of institutions’ espoused values across schools, education bureaus, and higher education institutions. A consistent pattern across three sectors with institutions’ particular preference for hierarchical relationship was detected. This can be explained by the cumulative and enduring nature of the Confucianism which provokes a fundamental core belief in the hierarchical ordering of personal relationships. It is interesting to note that higher education institutions and education bureaus espoused similar institutional values in terms of a high regard for

hierarchical relations, a relatively low emphasis on collectivism and self- cultivation. Unlike their counterparts in higher education sector and education bureaus, school leaders reported very different institutional espoused values in their schools. A consistent and much higher regard for humanism, collectivism and self-cultivation was found in schools, with hierarchical relationship considered as the least preferred institutional value.

The different cultures of the three sectors and the nature of their work may explain such differences. School leaders were generally educational practitioners and site-based leaders who were practically oriented. Compared with system officials and higher education administrators, they tended to pay more attention to operational issues related to learning, teaching, and site- based leadership. They also seemed to have considerable autonomy in running the schools within a broadly prescribed framework. They generally operated in a less bureaucratic culture than the other two groups in this study.

Figure 2. Institution’s espoused values (IEVs) by working institutions in Zhejiang Province,

China

( indicates significant difference at 0.05 level in ANOVA tests among the three profiles)

Conclusion

Globalization has brought a fundamental paradigm shift in educational administration and leadership in many countries across the world. In the times of changes, educational leaders are confronted with sets of conflicting values and dilemmas in the choice between traditional values and modern values

brought about by globalized forces. Educational leaders in China are no exception to this. Their assumptions are challenged when they operate in a globalizing context. They need to mediate various forces when their traditional cultures and values meet with new ideologies and values. In their leadership practices, the traditional Confucian ethics and values of hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism, and self-cultivation in educational administration and management may be competing with those so- called modern values of market, choice, competition, efficiency, flexibility, productivity and accountability in the age of knowledge economy and neoliberal governance (Pang, 2016; Ranson, 2003; Schugurensky, 2003; Webb, 2006). It is speculated that international competition and further opening of the market and education sectors will be intensified, and a confrontation between Confucianism and new ideologies, ethics and values brought by globalization will become more prominent in China.

Leadership is culturally complex, context dependent and acknowledged as a value-laden concept (Gronn, 2001; Sergiovanni, 2001; Wang, 2011). The findings of this study indicate that although the emergence of the new ideologies seems to be slowly changing the nature of Chinese contemporary culture and social values, such cultural change is unlikely to be radical due to the cumulative and enduring nature of the Chinese traditional culture. Confucianism plays a role in providing a structure of ethical precepts for the management of society based upon the achievement of social harmony and social order. The Confucian ethics and values of hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism, and self-cultivation continue to have an influence over leadership practices in contemporary Chinese educational institutions. Therefore, an incremental rather than transformational cultural change is expected in Chinese education and leadership practices in the long run.

The findings shed light on leadership strategies in contemporary Chinese educational institutions. The core values of collectivism work directly on people's consciousness influencing how they think about what they do. The values of collectivism affect at least two aspects of thought: The individual’s definitions of the task and commitment to the task (Angelides & Ainscow, 2000). The educational institution’s organizational culture would provide answers to employees about the meanings of the work and creates cohesive efforts from employees (Angus, 1996; Schein, 2010). While the values of humanism in institutions define the general thrust and nature of life for employees, the values of self-cultivation allows a great deal of motivation and

freedom to employees. Thus, the combination of humanism around the core values of the institution and of self-cultivation around autonomy and discretion for employees to pursue the institution’s aims may well be a key reason for their success (Pang, 2003; Law, 2011). However, not every employee in the workplace likes hierarchical relationship at all, because it binds people through hierarchical referral and supervision, rules and procedures, plans and schedules, adding positions and vertical information systems (Hoy, Blazovsky, & Newland, 1983; Gardner, 2014). Nevertheless, most organizations are created bureaucracies and hierarchical relationship within organizations has at least minimum functions. The removal and total avoidance of hierarchical relationship in institutions seems to be impossible and impractical (Pang, 1996, 2003, 2010). Therefore, a strong implication is that educational leaders should put more emphasis on collectivism, humanism and self-cultivation rather than on hierarchical relationship. The factor models of Confucian ethics and values reveal that if Chinese educational leaders are to use collectivism, humanism and self-cultivation to bind employees together, the important strategies include: (1) enhancing communication, consensus, participation and collaboration; (2) strengthening goal orientation and collegiality; and (3) promoting professional orientation and teacher autonomy. The findings also shed light on leadership roles in enhancing productivity, effectiveness, and performance. This study contributes to the field of educational leadership and effectiveness research through exploring the existence of Confucian ethics and values in leadership practices, especially in the Chinese cultural contexts. Leadership makes significant and measurable contribution, directly or indirectly, to the effectiveness of employees. The practices of the four Confucian ethics and values not only allow leaders to bind employees together within the workplace, but also enhance workplace performance, productivity and effectiveness by means of leadership influence (Gamage & Pang, 2003). The effective use of hierarchical relationship allows leaders to establish the organizational structures and social networks that interplay to facilitate and enhance outcomes. Collectivism enables leaders to emphasize the influence of organizational culture on the meaning people associated with their work and willingness to change. Humanism allows leaders to convey and sustain the institution’s purposes and goals that represent an important domain of indirect influence on outcomes. Self- cultivation allows the reinforcement of the leadership influence on employees who need space for self-determination, growth and discretion.

The research findings in this study provide implications for leadership preparation and practice in the new era. The findings support some researchers’ recommendation that new globally-derived, research based findings as well as indigenously crafted knowledge about teaching and learning and leading school represents legitimate subjects for learning among prospective and practicing school leaders (Walker & Hallinger, 2007; Walker, Hallinger, & Qian, 2007). We would argue that an awareness of indigenous cultural values in an increasingly globalized context and a contextual and cultural sensitivity will guide the immediate way forward for educational leadership development in China and other non-Anglo-American contexts.

This study has developed a theoretical framework of Confucian ethics and values that hold employees together in the workplaces. To date and to the knowledge of the researchers, there is relatively little empirical and quantitative research into the roles of Confucian ethics and values in educational leadership in the Confucius heritage cultures. Limited analyses and critiques of the subject have been published and we are still in the early stage of understanding the effects of Confucianism on educational leadership in organizations. Despite its potential contributions to the existing literature, final comments on the limitations of the study and suggestions for future research are provided.

Firstly, this study explored the value orientations of a group of educational leaders in Zhejiang Province in China. The findings indicate that the Confucian ethics and values of hierarchical relationship, collectivism, humanism and self-cultivation continue to be emphasized in educational leadership and management in the contemporary Chinese context. This study was exploratory since it was based on the survey responses from a small sample of 67 participants in a transnational leadership program. The researchers tentatively indicated sectoral differences between groups with no intention of generalizing the findings to the wider population. Further research is suggested to examine the value orientations of large samples of educational leaders in other regions of China.

Secondly, a comment is made concerning the weaknesses arising from the research instruments in this study, the Institution Values Inventory (IVI). It should be noted that testing of theoretical frameworks and development of instruments are, in principle, an ever-continuing process. Further testing and development work including a larger sample of educational leaders with different backgrounds should be conducted in the future research, for example,

including diverse demographic variables, a greater diversity of school leaders, more senior leaders from the educational bureaus, a larger sample of senior academic leaders from higher education institutions.

Thirdly, although advanced statistical programs were used in this study, researchers must carefully examine the statistical results and be aware of limitations. Statistical techniques are only tools, no matter how sophisticated they are, the final interpretation of the data and implications of findings should rely on the judgments of researchers, school administrators, educational leaders, policy-makers and general readers.

Lastly, the major aims of this study were to explore the existence of Confucian ethics and values in leadership practices in contemporary Chinese educational institutions. It has been argued in this study that the impacts of globalization have incurred a paradigm shift in educational administration and leadership in many countries, including China. The traditional Confucian ethics and values in leadership may be competing with the so-called new values. However, this study did not seek to examine whether Confucian ethics and values were in line or in conflict with modern values of competition, efficiency and accountability, and this could be the next research agenda.

References

AACSB International. (2011). Globalization of management education: Changing

international structures, adaptive strategies, and the impact on institutions.

Bingley, England: Emerald Group.

Advisory Committee on School-based Management. (2000). Transforming schools into

dynamic and accountable professional learning communities: School-based management consultation document. Hong Kong, China: Author.

Angelides, P., & Ainscow, M. (2000). Making sense of the role of culture in school improvement. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 11(2), 145-163. Angus, L. (1996). Cultural dynamics and organizational analysis: Leadership,

administration and the management of meaning in schools. In K. Leithwood, J. Chapman, D. Corson, P. Hallinger, & A. Hart (Eds.), International handbook of

educational leadership and administration (pp. 967-996). Dordrecht, the

Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

Bell, D. A. (Ed.) (2008). Confucian political ethics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Berthrong, J. H., & Berthrong, E. M. (2000). Confucianism: A short introduction. London, England: Oneworld.

Blackmore, J. (2000). Globalization: A useful concept for feminists rethinking theory and strategies in education. In N. C. Burbules & C. A. Torres (Eds.),

Globalization and education: Critical perspectives (pp. 133-155). London,

England: Routledge.

Bush, T., & Qiang, H. (2000). Leadership and culture in Chinese education. Asia

Pacific Journal of Education, 20(2), 58-67.

Cattell, R. B. (1978). The scientific use of factor analysis in behavioral and life

sciences. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Chen, M. (1995). Asian management systems. London, England: Routledge.

Erdener, C. B. (1997). Confucianism and business ethical decisions in China. Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong Baptist University Press.

Gamage, D. T., & Pang, N. S. K. (2003). Leadership and management in education:

Developing essential skills and competencies. Hong Kong, China: The Chinese

University Press.

Gardner, D. K. (2014). Confucianism: A very short introduction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, R. D. (2002). Conceptualising leadership with respect to its historical- contexual antecedents to power. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(2), 151-167. Gronn, P. (2001). Crossing the great divides: Problems of cultural diffusion for

leadership in education. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 4(4), 401-414.

Hallinger, P., & Kantamara, P. (2000). Leading at the confluence of tradition and globalization: The challenge of change in Thai schools. Asia Pacific Journal of

Education, 20(2), 46-57.

Hoy, W. K., Blazovsky, R., & Newland, W. (1983). Bureaucracy and alienation: A comparative analysis. Journal of Educational Administration, 21(2), 109-120. Huang, R. (1988). China: A macro history. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Ip, P. K. (1996). Confucian familial collectivism and the underdevelopment of the civic person. In L. N. K. Lo & S. W. Man (Eds.), Research and endeavors in

moral and civic education (pp. 39-58). Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong Institute

of Educational Research and the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). SPSS LISREL 7 and PRELIS. Chicago, IL: SPSS.

Law, S. (2011). Humanism: A very short introduction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Lee, J. K. (1997). A study of the development of contemporary Korean higher

education (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Texas at Austin, Austin,

Texas.

Lee, J. C. K., & Pang, N. S. K. (2011). Educational leadership in China: Contexts and issues. Frontiers of Education in China, 6(3), 331-341.

Li, C. (2008). The Confucian concept of Jen and the feminist ethics of care: A Comparative Study. In D. A. Bell (Ed.), Confucian political ethics (pp. 175-198). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lingard, B. (2000). It is and it isn’t: Vernacular globalization, educational policy, and restructuring. In N. C. Burbules & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Globalization and

education: Critical perspectives (pp. 79-108). London, England: Routledge.

Littlejohn, R. L. (2011). Confucianism: An introduction. New York, NY: I. B. Tauris. Mok, J. K. H., & Lee, H. H. (2002). A reflection on quality assurance in Hong Kong’s

higher education. In J. K. H. Mok & D. K. K. Chan (Eds.), Globalization and

education: The quest for quality education in Hong Kong (pp. 213-240). Hong

Kong, China: Hong Kong University Press.

Mok, J. K. H., & Welch, A. (2003). Globalization, structural adjustment and educational reform. In J. K. H. Mok & A. Welch (Eds.), Globalization and

educational restructuring in the Asia Pacific region (pp. 1-31). New York, NY:

Palgrave Macmillan.

Morrow, R. A., & Torres, C. A. (2000). The state, globalization and education policy. In N. C. Burbules & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Globalization and education: Critical

perspectives (pp. 27-56). London, England: Routledge.

Mulford, B. (2002). The global challenge: A matter of balance. Educational

Management & Administration, 30(2), 123-138.

Ngok, K. L., & Kwong, J. (2003). Globalization and educational restructuring in China. In J. K. H. Mok & A. Welch (Eds.), Globalization and educational restructuring