Cross-Strait Economic Relations:

China's Leverage and Taiwan's

Vulnerability*

C

HEN-

Y UANT

U NGEconomic relations between Taiwan and China have developed very rapidly due to strong business motivations in both societies. Taiwan's gov-ernment worries that Beijing might exploit China's economic leverage by using economic sanctions to achieve political goals if asymmetric interde-pendence in China's favor emerges across the Strait.

This paper seeks to answer two categories of questions: first, how large is China's actual and potential economic leverage over Taiwan in terms of imposing economic sanctions, and what conditions or factors would contribute to China's decision to exploit this economic leverage? Second, how vulnerable is Taiwan to any such imposition of economic sanctions, and what conditions or factors would contribute to the success or failure of these sanctions?

This paper concludes that China has no economic leverage over Tai-wan in terms of imposing economic sanctions and that TaiTai-wan's vulnera-bility to such a scenario is almost nonexistent.

KEYWORDS: economic leverage; economic sanctions; vulnerability;

cross-Strait economic relations.

CHEN-YUANTUNG(童振源) is an assistant research fellow at the Institute of International Re-lations, National Chengchi University, and adjunct associate researc h fellow at the Cross-Strait Interflow Prospect Foundation (兩岸交流遠景基金會) in Ta iwan. He rec eived his Ph.D . in international affairs from the Sc hool of A dvanced International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University, in 2002. Dr. Tung c an be reac hed at <ctung@jhu.edu>. *The author would like to expre ss his gratitude to D r. David M. Lampton at SAIS and two

anonymous re view ers for the ir helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript. ©Institute of International Relations, N ational Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan (ROC).

* * *

Driven by strong business motivations in both societies, economic re-lations between Taiwan and China have developed very rapidly. According to Taiwan's statistics, by the end of 2002 China was the biggest recipient of Taiwan's outward foreign direct investment (FDI) with an accumulated total reaching US$25.5 billion, 48.3 percent of Taiwan's total FDI. Never-theless, Perng Fai-Nan (彭淮南), governor of Taiwan's Central Bank, es-timated that by the end of 2002 the real figure of Taiwan's cumulative investment in China was about US$66.8 billion.1

According to Taiwan's official estimate, two-way trade across the Taiwan Strait in 2002 totaled US$41 billion, with Taiwan enjoying a US$25 billion trade surplus— mak-ing China Taiwan's third largest tradmak-ing partner and largest export market.

Taiwan's government feels ill at ease having such a close economic relationship with its powerful political rival, in part because the island fears that the flood of investment and trade from Taiwan will make the island economically dependent on China, undermining Taiwan's de facto political independence. In fact, Taiwan's fear has been triggered and reinforced by the fact that Beijing explicitly considers cross-Strait economic relations to be an important source of political leverage against Taiwan. Beijing con-ducts cross-Strait economic exchange with two political strategies in mind: "yi min bi guan" (以民逼官, exploiting the public to pressure the officials) and "yi shang wei zheng" (以商圍政, exploiting the businesspeople to en-circle the government). Taipei worries that, if asymmetric interdependence in China's favor emerges across the Strait, Beijing might exploit China's economic leverage through the use of economic sanctions in order to achieve political goals.2

In theory, there are two instruments of economic leverage that China

1Lin Ming-cheng, "Perng Fai-Nan: Investment in Mainland Reaches US$66.8 Billion," Zhongguo shibao (China Times) (Taipei), January 17, 2003.

2Kong-Lien K ao, Liang'an jingmao x iankuang yu zhanwang (Cross-Strait e conomic rela-tions: The current situa tion and future prospects) (Taipei: Mainland Affairs Council, 1994), 8; and Charng K ao, Dalu jinggai yu liang'an jingmao guanxi (Mainland economic reforms and cross-Strait economic relations) (Taipei: Wunan, 1994), 130-31.

could use to achieve policy objectives toward Taiwan: economic sanctions (through disruption of economic benefits derived from trade and financial ties) and economic inducement (through provision of economic benefits from trade and financial ties). China's current policy is not an explicit strategy of offering economic inducements to Taiwan. China has not at-tempted to link the provision of economic benefits to Taiwan (such as preferential treatment of Taiwan's businesses) and China's political de-mands. Beijing has never stated that China will provide economic benefits to Taiwan only if Taiwan makes political concessions to China. Therefore, based on Taiwan's primary concerns and China's current policy approach, this paper focuses on any economic leverage China might gain through the imposition of economic sanctions against Taiwan.

This paper seeks to answer two categories of questions: first, how large is China's actual and potential economic leverage over Taiwan in terms of imposing economic sanctions, and what conditions or factors would contribute to China's decision to exploit this economic leverage? Second, how vulnerable is Taiwan to any such imposition of economic sanctions, and what conditions or factors would contribute to the success or failure of these sanctions?

This paper defines economic sanctions as the threat or act by a state or coalition of states (the sender) to disrupt customary economic exchange with another state (the target) in order to punish the target, force change in the target's policies, or demonstrate to a domestic or international audience the sender's position on the target's policies. Economic sanctions do not include economic warfare, economic inducements, or trade wars.3

Moreover, both China's economic leverage and Taiwan's vulnerabil-ity will be examined through a two-stage test: the initiation and outcome of economic sanctions. This test will have four scenarios. First, if conditions

3"Economic w arfare" seeks to weaken an adversary's aggregate ec onomic potential in order to weaken its military capabilities, either in a peacetime arms race or in an ongoing w ar. "Economic inducements" involve c ommercial concessions, technology transfers, and other economic carrots that are extended by a sender in exchange for political compliance on the part of a target. "Economic inducements" are also called "positive sanctions." "Trade wars" are disputes over economic policy and behavior instead of political or security goals.

across the Taiwan Strait are favorable for China to impose economic sanc-tions and for Taiwan to make concessions, then China has leverage over Taiwan and Taiwan is vulnerable to China's leverage. Second, if conditions are unfavorable for China to impose economic sanctions and for Taiwan to make concessions, then China has no leverage over Taiwan and Taiwan is not vulnerable to China's leverage. Third, if conditions are favorable for China to impose economic sanctions but unfavorable for Taiwan to make concessions, China has only symbolic leverage over Taiwan and Taiwan has symbolic vulnerability to China's leverage. Fourth, if conditions are unfavorable for China to impose economic sanctions but favorable for Taiwan to make concessions, China has only quasi-leverage over Taiwan and Taiwan has quasi-vulnerability to China's leverage.

In three steps, this paper analyzes the two questions posed above. First, this paper explores the essence of cross-Strait economic relations in terms of the global division of labor and global interdependence.

Second, this paper explores the implications of prior research on economic sanctions. It evaluates theories on both the initiation and the outcome of economic sanctions by analyzing the Hufbauer-Schott-Elliot (HSE) approach, the domestic politics/symbolic approach, the signaling/ deterrence approach, and the conflict expectations model. The theories of economic sanctions generalize what conditions or factors would contribute to the sender's decision to exploit economic leverage through the imposi-tion of economic sancimposi-tions against the target and what condiimposi-tions or factors would contribute to the success or failure of these sanctions.

Third, this paper examines important variables in theories of eco-nomic sanctions through two case studies, the 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 Taiwan Strait tensions.4

These theories generalize the behavior pattern

4The 1995-1996 tensions were triggered by a combination of President Le e Teng-hui's visit to his alma mater, Cornell U niversity, and the speech Lee made a t Cornell University during the trip. In addition, w hen interviewed by Deutsche Welle Radio on July 9, 1999, Preside nt Lee Teng-hui said that since 1991, when the Republic of China Constitution was amended, cross-Strait re lations became "state-to-state," or at least "a special sta te-to-state relation-ship." These tw o incidents were taken by Beijing as deliberate attempts to strengthen both domestic and international acceptance of Taiw an as a sovereign nation.

of both the sender and the target during economic sanctions, but do not necessarily explain the specific case of interaction between Taiwan and China. Therefore, this paper further analyzes the significant variables derived from the theories through the two case studies.

The 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 Taiwan Strait incidents created sig-nificant strain between Taiwan and China. Beijing attempted both to coerce Taipei to return to the previous status quo by accepting the "one-China principle" and to deter Taipei from declaring (or marching toward) Taiwan independence. The People's Republic of China (PRC) threatened the use of force against Taiwan through moderate military mobilization and an expansion in the scope of the intended military exercises near Taiwan from July 1995 to March 1996 and from July to September 1999.

Beijing has actually proven reluctant and generally ineffective, how-ever, in exploiting its economic leverage through economic sanctions against Taiwan, even during the 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 cross-Strait tensions. During the 1995-1996 missile crisis, Beijing made significant ef-forts to reassure Taiwan's businesspeople that their investments in China were safe. Beijing also demonstrated restraint in the aftermath of then Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui's (李 登 輝) "special state-to-state rela-tionship" comment of July 9, 1999. After the victory of Chen Shui-bian (陳 水 扁, a one-time pro-independence opposition leader) in Taiwan's March 2000 presidential race, however, Beijing overtly warned some Tai-wan business figures5

that their interests in China would be affected if they supported Taiwan independence.6 Despite these caveats, China has yet to follow up on these threats with concrete sanctions.

Given Beijing's high motivation to persuade Taipei to reaffirm the

5It wa s reported that Beijing would punish Yin Qi (殷琪, president of the Continental En-gineering Corpora tion), Stan Shih (施振榮, chairman of the Acer Group), Chang Yung-fa (張榮發, chairman of the Evergreen Group), a nd Shi Wen-long (施文龍, chairman of the Chi M ei G roup) because of their support for Chen Shui-bian. See Bin-zhong Song, "China Warns Taiwan Businesspeople Who Support Taiwan Independence," Zhongguo shibao, April 9, 2000.

6"O n the Current Development of Cross-Strait Economic Relations: Questions Answered by the Leader of the CCP Central Office for Taiw an Affairs and the State Council Taiwan Affairs Office," Renmin ribao (People 's Daily), A pril 10, 2000, 1.

"one-China principle" and deter Taipei from marching toward Taiwan in-dependence, another question to be answered is why China exercised such great restraint in not imposing economic sanctions against Taiwan in these instances.

Furthermore, this study explores Taiwan's vulnerability to China's economic sanctions by analyzing the island's vulnerability to military threats during both the 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 tensions. This analysis is conducted with the understanding that both military threats and eco-nomic sanctions could be used to signal Beijing's resolve to use force against Taiwan and thus to extract political concessions from Taipei. In ad-dition, both military threats and economic sanctions will impose economic pain on Taiwan. The similar logic for both military threats and economic sanctions is that, all other things being equal, the more value-deprivation to which the target is subject, the more likely is political disintegration within— and thus concessions be drawn from— the target.

Cross-Strait and

Global Economic Interdependence

The cross-Strait economic division of labor is only part of broader global commodity chains (GCCs) and global production networks (GPNs). The production of a single commodity in the globalization of production often spans many countries, with each nation performing tasks in which it has a cost advantage. Globalization today thus entails the detailed dis-aggregation of stages of production across national boundaries under the organizational structure of densely networked enterprises.7

Thus, any im-pact on cross-Strait economic relations would have interrelated and

wide-7Gary Gereffi, Miguel Korzeniewicz, and Roberto P. K orzeniewicz, "Introduction: G lobal Commodity Chains," in Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, ed. Gary Gereffi and Miguel Korzeniewicz (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1994), 1-2; and Gary G ere ffi, "Commod-ity Chains and Regional D ivisions of La bor in East A sia," in The Four Asian Tigers:

Eco-nomic Development and the G lobal Political Economy, ed. Eun Mee Kim (San D iego, Calif.:

reaching global effects.

Within the framework of the global division of labor and global inter-dependence, this paper emphasizes four links in discussing cross-Strait economic interdependence: investment-trade, internal-external,

bilateral-global, and production-consumption.

1. The investment-trade link: Most cross-Strait trade is driven by Tai-wan's investment in China. Taiwan-invested enterprises (TIEs) play a very important role in importing intermediate and capital goods from Taiwan and exporting finished goods to developed countries, in particular to the United States and Japan. In the mid-1990s, about one-third to two-thirds of Taiwan's exports to China were driven by TIEs. In addition, Chinese exports produced by TIEs were estimated to make up between 14 and 18 percent of China's total exports. Furthermore, around one-fifth of Chinese exports to the United States were produced by TIEs.8

Therefore, any impact on the production of TIEs would have signifi-cant repercussions for cross-Strait trade. On the other hand, any disruption of trade between Taiwan and China would also have a strong impact on the production activities of TIEs. In turn, this impact on the production ac-tivities of TIEs will further influence Chinese exports and other economic activities.

2. The internal-external link: Because about 36 to 38 percent of Taiwan entrepreneurs have broad partnerships with local Chinese enter-prises, local governments, and foreign enterenter-prises, any internal sanctions on the TIEs would provoke protest from both internal and external eco-nomic actors.9

In addition, because many Taiwan entrepreneurs invested

8Chen-yuan Tung, "China's Economic Le verage and Ta iwan's Security Concerns w ith Re-spect to Cross-Strait Economic Relations" (Ph.D. dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, 2002), 42-46, 66-67; and Chen-yuan Tung, "Trilateral Economic Relations among Taiwan, China, and the United States," Asian Affairs: An American Review 25, no. 4 (Winte r 1999): 229-35.

9Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA, Taiwan), Zhizaoye duiwai touzi shikuang diaocha baogao (Survey report on outward investme nt of the manufacturing industry) (Taipei:

MO EA , 1997), 77; and MOEA, Zhizaoye duiwai touzi shikuang diaocha baogao (Survey report on outward investment of the manufacturing industry) (Taipei: MOEA, 2000), 220, 223, 226.

in China by having their subsidiaries register and raise funds in third areas (such as Hong Kong, Singapore, the United States, and elsewhere), Chi-nese internal sanctions on TIEs would trigger a series of external disputes between China and these countries.10

Moreover, because TIEs contribute significantly to China's exports, China's imposition of import (internal) sanctions on Taiwan's goods would interrupt the production of the TIEs and thus result in a reduction of China's (external) exports, and vice versa. For example, according to a 1999 study by the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research (中華經濟研究院), the correlation multiplier between Taiwan's exports to China and China's exports produced by TIEs was 20 percent in 1997; that is, if Taiwan's ex-ports to China were disrupted by one dollar, China's exex-ports produced by TIEs would decline by five dollars.11

3. The bilateral-global link: Since Taiwan's provision of intermediate and capital goods for TIEs and the production by TIEs is only part of larger GCCs, any disruption of cross-Strait trade or production by TIEs would trigger a snowball effect on these GCCs. For example, Taiwan's imports of key electronics components and systems software from Japan and the United States would significantly decrease if the activities of the electron-ics industry across the Taiwan Strait were disrupted. Furthermore, Singa-pore and Hong Kong would lose tremendous business opportunities to pro-vide support services for the GCCs involving both Taiwan and China.

In addition, any bilateral disruption of cross-Strait economic ac-tivities would have a heavy impact on the Asia-Pacific region due to robust regional economic interdependence among Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, the United States, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. In 1998, the average trade dependence (share of intra-regional trade to total trade) for these seven countries was as high as 44 percent. Moreover, the other five coun-tries also have immense stakes in both Taiwan and China in terms of

in-10Tung, "China's Economic Leverage," 23-27, 40-41.

11Wen-long Lian et al., Liang'an chuko liandong guanxi zhi yanjiu (A study on the correla-tions for cross-Strait exports) (Taipei: Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Re search, 1999), 122.

vestment. By the end of 1998, the United States, Japan, Hong Kong, Sin-gapore, British Central America, and South Korea cumulatively invested US$23.9 billion, or 73.1 percent of total FDI in Taiwan. As of 1999, Hong Kong, the United States, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, the Virgin Islands, and South Korea were the top seven foreign investors in China, comprising US$262.2 billion, or 85.3 percent of the cumulative FDI in China.12

4. The production-consumption link: Most Taiwan products made in Taiwan's domestic facilities or by TIEs are exported to developed coun-tries. Any disruption of GPNs would have an immediate impact on global consumption. For instance, since 1997 Taiwanese firms have ranked as the third largest producers of information products in the world, if the output of both domestic and overseas factories is taken into account. Furthermore, in 2000 Taiwanese firms were the largest producers of more than fourteen information products in the world, most with more than 50 percent of world market share. Therefore, any disruption of cross-Strait economic activities (including both trade and production of TIEs) would seriously harm both consumers of electronics products around the world and global economic development.

Theories on the Initiation of Economic Sanctions

This paper examines three approaches to the initiation of economic sanctions. The domestic politics/symbolic approach focuses on the domes-tic polidomes-tics of sender countries. On the one hand, the pressure from both the public and global/domestic interest groups who stand to gain either pecuni-ary or nonpecunipecuni-ary benefits from sanctions would impel the sender govern-ment to impose economic sanctions against the target. In particular, eco-nomic sanctions provide the sender a visible and less expensive alternative to either military intervention or doing nothing. On the other hand, both the public and global/domestic interest groups who would suffer either

ary or nonpecuniary losses from sanctions would oppose the sender's sanc-tions. Therefore, the dynamic balance of these two opposing forces would determine whether the sender will impose sanctions on the target.13

Moreover, it is very plausible that a sender government facing polit-ical and economic instability is less likely to impose economic sanctions with high costs against the target, because the negative effects of sanctions would exacerbate the domestic instability of the sender. This argument, in particular, finds support from Chinese military experiences from 1949 to 1992.14

In general, the domestic politics/symbolic approach emphasizes that the decision, form, and severity of sanctions applied would depend primari-ly on five factors: (1) the relative gains or losses of various interest groups and the public; (2) the relative influence of interest groups and the public within the sender state; (3) the ability of policymakers to act independently of pressure from both the public and interest groups; (4) the amount of in-formation possessed by individuals and groups within the sender country regarding the objectionable policy of the target country; and (5) the condi-tions of political and economic stability in the sender.15

The signaling/deterrence approach argues that sanctions can be an

ef-13As argued in Tung, "China 's Economic Leverage," 135-47, based on the follow ing litera-ture: David Leyton-Brow n, "Lessons and Policy Considerations about Economic Sanc-tions," in The Utility of International Econom ic Sanctions, ed. D avid Leyton-Brown (New York: St. M artin's Press, 1987), 305-6; William H. Ka empfer and A nton D . Lowenberg, "The Problems and Promise of Sanctions," in Economic Sanctions: Panacea or Peac

e-building in a Post-Cold War World? ed. Da vid Cortright and George A. Lopez (Boulder,

Colo.: Westview Press, 1995), 63-64; and William H . Kaempfe r and Anton D. Lowenberg, "A Public Choice Analysis of the Political Economy of International Sanctions," in

Sanc-tions as Economic Statecraft: Theory and Practice, ed. Steve Chan and A. Cooper Drury

(Ne w York: St. Martin's Press, 2000), 159-81.

14Alasta ir Iain Johnston, "China's Militarized Interstate D ispute Be havior 1949-1992: A First Cut at the Data," The China Quarterly, no. 153 (March 1998): 18-20; and J. David Singer, "Statistical Regularitie s in Chinese and Other Foreign Policy: A Basis for Prediction?" (Paper presented at the conference on "China in the 21st Century," sponsored by the Demo-cratic Progressive Party, National Taiwan University, Taipei, November 6-7, 1999), avail-able online at <http://www.future-china.org/csipf/activity/19991106/mt9911_05e .htm> (accessed on November 20, 2000).

15These five factors are laid out in Tung, "China's Economic Le verage," 135-49, based on the following litera ture: Kaempfer and Lowenberg, "A Public Choice Analysis of the Political Economy of Inte rnational Sanctions," 159-81; K aempfer and Lowenberg, "The Problems

fective signaling and deterrence tool because states conduct foreign policy in a world of imperfect information. As a result, states frequently engage in signaling techniques in order to demonstrate credibility. Economic sanc-tions, therefore, could be a type of signal and deterrence to distinguish credible threats of future action (such as military action) from cheap talk. When threatening to use military force, the sender will incur greater costs to signal its resolve. Statistical tests provide strong support for this ar-gument.1 6

The conflict expectations model of economic sanctions developed by Daniel Drezner makes two assumptions: (1) states act as rational, unitary utility-maximizers, and (2) national preferences are partially motivated by conflict expectations. Accordingly, the model makes two specific pre-dictions about the pattern of sanction attempts. First, no sanction should generate greater costs for the sender than the target. Second, conflict ex-pectations should be positively correlated with the costs to the sender, but negatively correlated with the costs to the target. In general, the sender will prefer imposition of economic sanctions against the target if the target's costs are sufficiently greater than its own costs, and there is some expecta-tion of future conflict. Both arguments have been supported by strong sta-tistical evidence.17

Regarding the implications for cross-Strait economic relations, one necessary condition for China to impose sanctions against Taiwan is that China's costs be lower than Taiwan's. Second, China might use economic leverage to threaten Taiwan or signal its resolve so long as China enjoys an advantage in their interdependent economic relationship. Third, the

dy-and Promise of Sanctions," 63-64; dy-and Richard N. H aass, "Introduction," in Economic

Sanctions and American D iplomacy, ed. Richard N. Haa ss (New York: Council on Foreign

Relations, 1998), 3.

16David Ba ldw in, Ec onomic Statecraft (Prince ton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1985), 24; Robert A. Pape, "Why Economic Sanctions D o Not Work," International Security 22, no. 2 (Fall 1997): 98-106; Daniel W. Drezner, The Sanctions Paradox: Economic Statecraft

and International Relations (New York: Cambridge U niversity Press, 1999), 15-17,

120-21; and Valerie L. Schwebach, "Sanctions as Signals: A Line in the Sand or a Lack of Re-solve?" in Chan and Drury, Sanctions as Economic Statecraft, 187-211.

namic balance between the public and global/domestic interest groups, and between various conditions of political and economic stability, will in the end determine whether China will impose sanctions against Taiwan. Chi-nese leaders need to reconcile both the domestic and international impera-tives of a two-level game simultaneously.

As a result, with respect to China's leverage, four variables are signifi-cant in determining whether China will impose sanctions against Taiwan: first, the opportunity costs of economic sanctions; second, the signaling ef-fects of economic sanctions; third, China's domestic economic and political stability; and fourth, the Chinese public and interest groups in China.

This research does not examine the influence of the public on China's decision-making process largely because only extremely limited public opinion polls are available in China on cross-Strait issues, but also because of the following four considerations. First, according to the literature on economic sanctions, pre-1980s evidence generally rejects the hypothesis that economic sanctions are imposed in reaction to public opinion.18

Second, there has been no statistical evidence to validate that hy-pothesis for the years since the 1980s, although anecdotal evidence shows that public opinion might have influenced U.S. decision-making on eco-nomic sanctions.19

Nevertheless, it is unclear whether the United States was the primary sender because it was mainly influenced by the public or because it was the economic power.2 0

Third, China is not a democratic regime and the Chinese government still basically controls mass media. Therefore, the Chinese government

18Richard J. Ellings, Embargoes and World Power: Lessons from American Foreign Policy (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1985), 113-55; and A. Cooper Drury, "How and Whom the U.S. President Sanctions: A Time-series Cross-section A nalysis of U .S. Sanction Deci-sions and Characteristics," in Chan and Drury, Sanctions as Economic Statecraft, 17-36. 19Kimberly Ann Elliott and G ary Clyde Hufbauer, "Same Song, Same Refrain? Economic

Sanctions in the 1990s," AEA Pape rs and Proceedings, M ay 1999, 403-8; and Kaempfer and Lowenberg, "A Public Choice Analysis of the Political Economy of International Sanc-tions," 158-86.

20Gary Clyde H ufbaue r, "Trade a s a Weapon" (Paper for the Fred J. Hansen Institute for World Peace , San D iego State University, World Peace Week, April 12-18, 1999), avail-able online at <http://w ww.iie.com/TESTMONY/gch9.htm> (accessed July 25, 2000), 4-5 of 4-5.

does not need to respond directly to, and can to some degree manipulate, public opinion. In fact, Beijing has succeeded in minimizing or even sup-pressing the surge of nationalism in many of the most sensitive sovereignty disputes— including the Diaoyutai (釣魚台, or Senkaku Islands) dispute, the South China Sea islands dispute, the U.S. bombing of the Chinese em-bassy in Belgrade, and the Taiwan issue.21

As a result, in 2000 nationalism (public opinion) was not a significant factor in Chinese decisions on for-eign policy.

Fourth, the public could either urge or discourage sanctions against Taiwan. This depends on whether the public will be injured by or benefit from the sanctions in terms of pecuniary or nonpecuniary losses or gains. During these two Taiwan Strait incidents, people in China's coastal areas— who have enormous interests in cross-Strait economic exchange and the achievement of economic development— generally opposed the escalation of cross-Strait tensions and supported the peaceful resolution of bilateral disputes.2 2

Therefore, this research does not address the variety of public opinion in China during the Taiwan Strait tensions, since such an addition would not change the paper's basic conclusions.

The hypotheses on the initiation of China's sanctions against Taiwan are as follows:

1. The gap in costs between Taiwan and China (the potential power of economic leverage from asymmetric economic interdepend-ence) was insufficiently favorable for Beijing to initiate economic sanctions against Taipei.

2. China had grave domestic concerns and could not afford to impose economic sanctions against Taiwan due to economic, social, and political instability, and because of opposition from interest groups

21Tung, "China's Economic Leverage," 207-33.

22Personal interviews with various senior scholars and officials in Shanghai (上海) and Xiamen (廈門) from June to July, 2001.

(such as southeast coastal leaders and Taiwan businesspeople) who would be associated with such sanctions.

3. Chinese leaders believed that military threats directed at Taiwan were more effective signals and methods of deterrence than actual economic sanctions would have been.

Theories on the Outcome of Economic Sanctions

This paper examines four approaches that account for the outcome of economic sanctions. Drawn from economic sanction case studies, the HSE approach has been developed by Gary Hufbauer, Jeffery Schott, and Kim-berly Elliot, who have been collecting the most comprehensive and broadly used database of economic sanction cases (a total of 115 cases).23

First of all, one should note that economic sanctions are generally ineffective and the rate of success in terms of target compliance has been declining over time, particular from 1975 to 1990. The success rate of economic sanctions based on the HSE database, excluding economic war-fare and trade disputes, is as low as 4.6 percent (5 of 109 cases) to 10.4 percent (12 of 115 cases).2 4

Based on the HSE database and other studies, the HSE approach suggests that sanctions are most effective under the following conditions: modest sender goals, a weak and unstable target, high costs to the target, low costs to the sender, a friendly relationship between the sender and the target, a high trade concentration for the target with the sender, quick and harsh unilateral sanctions, no assistance to the target by third countries, and, finally, sanctions that are primarily financial rather than

trade-23Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, and K imberly Ann Elliot, Economic Sanctions Rec onsidered: History and Current Polic y, second edition (Washington, D.C.: Institute

for International Economics, 1990).

24Finding in Tung, "China's Economic Leverage," 123-33, based on the following literature: Pape, "Why Economic Sanctions Do N ot Work," 100-3; and Kim Richard Nossa l, "Liberal Democratic Regimes, International Sanctions, and Global Governance," in Globalization

and Global Governance, ed. Raimo Va yrynen (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield,

oriented.2 5

Although the HSE database is criticized for sample bias since it includes trade disputes and economic warfare, most of the above vari-ables have been further confirmed by the other three approaches mentioned in this section.

The domestic politics/symbolic approach focuses on the domestic political economy of the target country. It analyzes three factors that work against the effectiveness of economic sanctions: (1) few cases with damaging sanctions; (2) the rally-around-the-flag effect reinforced by nationalism; and (3) manipulated redistribution effects of sanctions in the target. Furthermore, one could plausibly argue that if the sender suffers domestically from economic and political instability, the target will less likely concede because the sender will have more concerns about the costs of sanctions.

First, sanctions are often imposed half-heartedly by the sender gov-ernment out of a need to satiate domestic political pressure from the public and interest groups to do something in response to the target's disputed be-havior. Hence, sanctions are symbols; their effectiveness is of secondary concern. In addition, the costs of sanctions will hurt some interest groups and even the public at large, who will oppose severe measures. Thus, it is not surprising that the sanctions actually adopted often appear ineffectual and the target country may face insufficient coercive pressure to consider acquiescing.26

Second, economic sanctions might be seen by the target as a humili-ating affront and thus trigger a rally-around-the-flag effect. Pervasive nationalism and a lack of discrimination between the "guilty" and the "in-nocent" will significantly reinforce the rally-around-the-flag effect. The sender might become a common enemy for the people of the target nation.

25Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliot, Econom ic Sanctions Reconsidered, 49-115; George A. Lopez and David Cortright, "Economic Sanctions in Contemporary Global Relations," in Cort-right and Lopez, Econom ic Sanctions, 9; K imberly A nn Elliot, "Factors Affecting the Suc-cess of Sanctions," ibid., 53; and Joseph J. Collins and G abrielle D. Bowdoin, Beyond

Unilateral Economic Sanctions (Washington, D .C.: Center for Strategic and International

Studies, 1999), 15-16.

26Kaempfer and Lowenberg, "A Public Choice Analysis of the Political Economy of Inter-na tioInter-nal Sanctions," 159-61.

The resistance of domestic groups and the public to economic sanctions becomes synonymous with patriotism, while dissent would trigger accusa-tions of disloyalty or treason. These effects would facilitate political inte-gration in the target and cause the sanctions to fail.27

Third, target governments may prefer to be sanctioned because they can distribute to their supporters economic rent that stems from the trade restrictions and thus weaken their domestic opponents. While in the long run sanctions hurt the traoriented sectors of the target economy by de-priving them of income, in the short run a sender's embargo strengthens the target's import-substitution sectors by providing them rent-seeking op-portunities in the target. In addition, the target government may redirect external pressure onto isolated or repressed social groups while insulating and protecting itself. As a result, sanctions may end up strengthening the target government, and hence its ability to resist the coercive attempts of the sender government.28

By contrast, this approach cites two factors as contributing to the ef-fectiveness of sanctions: (1) the fifth-column effect and (2) political and economic instability in the target. The fifth-column effect is seen when some particular groups in the target country who have been hurt by the sanctions petition their government to comply with the sender's demands. The more the sanction directly hurts the target's central government, the greater is the chance to influence its policy. In addition, core support groups of the target regime negatively affected by sanctions will put pressure on their government.29 As a matter of fact, China's political strate-gies toward Taiwan— yi min bi guan and yi shang wei zheng— are based on

27Tung, "China's Economic Leverage," 165-68; Johan Galtung, "On the Effects of Interna-tional Economic Sanctions," World Politics 19 (1967): 388-99; a nd Zachary Se lden,

Eco-nomic Sanctions as Instrum ents of American Foreign Policy (Westport, Conn.: Praeger,

1999), 4-5, 20-23.

28Pape, "Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work," 107; and Paul D. Taylor, "Cla usewitz on Economic Sanctions: The Case of Iraq," Strategic Review 23, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 50-56. 29Jonathan Kirshner, "The Microfoundations of Economic Sanctions," Security Studies 6, no. 3 (Spring 1997): 32-64; D avid Cortright and George A . Lopez, The Sanctions Decade:

Assessing UN Strategies in the 1990s (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 2000), 20-22; and

expectations of a fifth-column effect. Furthermore, a target government faced with domestic political and economic instability will tend to concede to the sender's demands.3 0

Complicating the situation is the fact that economic sanctions can generate both the rally-around-the-flag effect and the fifth-column effect at the same time. In order to bring about alterations to an objectionable policy, the fifth-column effect must overwhelm the rally-around-the-flag effect. In other words, sanctions must reduce the political effectiveness of pro-regime groups more than they reduce the effectiveness of opposition groups. In particular, financial sanctions tend to reinforce the fifth-column effect while minimizing the rally-around-the-flag effect. By contrast, trade sanctions cannot be aimed accurately at any particular group, and are thus more likely to trigger a rally-around-the-flag effect.

There are several statistical tests of financial sanctions and political instability in the target country, but none on the rally-around-the-flag effect, nationalism, and the fifth-column effect. Overall, the argument that financial sanctions are more effective is based on moderate statistical evidence, while the argument that a target with unstable political and eco-nomic conditions tends to make concessions to the sender has strong sta-tistical support.31

There is not sufficient statistical evidence, however, to confirm that democracy in a target country is a necessary or sufficient condition for the success of sanctions. In general, a democratic regime may provide more space for both the public and interest groups to influence the target govern-ment. An authoritarian regime, however, also needs to respond to pressure from interest groups or members of the regime itself— such as factions or competing leaders, bureaucratic sectors, local leaders, core business

30Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliot, Ec onomic Sanctions Reconsidered, 97-98; and Drezner, The Sanctions Paradox, 114, 122.

31Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliot, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, 102-11; Drezner, The Sanctions Paradox, 121-25, 131-47; San Ling Lam, "Economic Sanc tions and the Success

of Foreign Policy Goals," Japan and the World Economy 2 (1990): 239-47; and Kimberly Ann Elliott a nd Peter P. Uimonen, "The Effectiveness of Economic Sanctions with Appli-cation to the Case of Iraq," ibid. 5 (1993): 403-9.

groups, or sometimes even the public. Furthermore, there are times when a target with a functioning electoral system will quite successfully resist international efforts to sanction it. Indeed, Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliot report at least eleven cases where sanctions against liberal democracies failed.32

The signaling approach argues that sanctions could be useful as a sig-nal for more coercive measures. In this regard, sanctions are only useful as a signal of resolve; economic sanctions alone cannot work. The casual ar-gument in this school of thought is that what appears to be the success of sanctions is actually the product of an implicit military threat. This ap-proach makes two predictions about the pattern of outcomes of sanctions. First, the sender's costs should be positively correlated with the size of the concession. Second, a threat of force, or a difference in aggregate power, should be positively correlated with the size of the concession.33

However, statistics provide no support for the signaling approach. The statistical evidence available categorically rejects the argument that high sender costs can effectively signal resolve and thus lead to a successful outcome. High sender costs are found to be negatively correlated with the success of sanctions. In addition, neither military power nor military threats affect the outcome of attempted sanctions. Therefore, from the per-spective of the outcome, economic sanctions are not a signal of military threats.34

The conflict expectations model makes two major predictions. First, the greater is the gap that exists between the costs of the sender and those of the target, the greater is the target's concessions. An increase in the

32Tung, "China's Economic Leverage," 175-80; Nossal, "Liberal Democratic Regimes," 134-48; and Pape, "Why Economic Sanctions Do N ot Work," 98-106.

33Daniel W. Drezner, "The Complex Causation of Sanction Outcomes," in Chan and Drury, Sanctions as Ec onomic Statecraft, 215-16; Pape, "Why Economic Sanctions Do N ot

Work," 98-106; and Drezner, The Sanctions Paradox, 113, 122.

34Lam, "Economic Sanctions and the Suc cess of Foreign Policy Goals," 244-46; T. Clifton Morgan and Valerie L. Schw ebach, "Fools Suffer Gladly: The Use of Ec onomic Sanctions in International Crises," International Studies Quarterly 41 (1997): 38-47; Elliott and Uimonen, "The Effectiveness of Economic Sanctions," 403-9; Drezner, The Sanctions

sender's costs makes economic sanctions less viable and less profitable. By contrast, an increase in the target's costs makes economic sanctions more viable and more profitable. Second, if the sender and the target are adver-saries, the target will be more reluctant to acquiesce under the pressure of economic sanctions because of relative gains and concern about its rep-utation. As the target and sender anticipate few political conflicts in the future, the magnitude of the target's concessions will increase. For eco-nomic sanctions to produce significant concessions, the absence of conflict expectations is a necessary condition. If the target-sender relationship is adversarial, there must be a large gap in costs for sanctions to generate even moderate concessions. The statistical results provide solid empirical sup-port for this model.35

Regarding the implications for cross-Strait economic relations, in theory China's sanctions against Taiwan generally tend to be ineffective. The probability of success for Chinese economic sanctions is only 4.6 to 10.4 percent. In addition, because of severe bilateral hostility, the neces-sary condition for China's successful sanctions with Taiwan's moderate concessions is that China enjoy a large gap in costs in its favor.

The following conditions will contribute to the effectiveness of eco-nomic sanctions: (1) China enjoys a significant gap in costs of ecoeco-nomic sanctions on Taiwan; (2) China's sanctions trigger a fifth-column effect; (3) China imposes financial sanctions against Taiwan instead of trade sanc-tions, but financial flows now favor Taiwan's leverage; (4) Taiwan is un-stable; and (5) China imposes sanctions against Taiwan quickly, with maxi-mum harshness and without significant international assistance to Taiwan. By contrast, the following conditions will contribute to the ineffec-tiveness of China's sanctions: (1) China's sanctions trigger nationalism and a rally-around-the-flag effect in Taiwan; (2) China suffers from domestic instability; (3) Taiwan's government can manipulate the effects of

re-35Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliot, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, 102-3; Lam, "Economic Sanctions a nd the Success of Foreign Policy Goals," 239-47; Elliott and Uimonen, "The Effectiveness of Economic Sanctions," 403-9; Morgan and Schw ebach, "Fools Suffer Gladly," 43-45; Makio Miyagawa, Do Economic Sanctions Work? (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992), 61-88; and Drezner, The Sanctions Paradox, 122-24, 131-247.

distribution of sanctions to favor the ruling coalition; and (4) Taiwan's decision-makers have strong concerns about relative gains and reputation in the cross-Strait conflict.

Of the above nine variables, it is impossible to predict the following: (1) the domestic situation for both Taiwan and China; (2) whether Beijing could impose sanctions against Taiwan quickly, with maximum harshness; and (3) whether the Taiwanese government could manipulate redistribution effects of sanctions to favor the ruling coalition if Beijing were to impose economic sanctions against Taiwan. However, these three variables are not the most important variables to influence the effectiveness of eco-nomic sanctions. They are secondary to the following four variables: (1) the gap in costs of sanctions between Beijing and Taipei (including the reaction of the international community toward China's sanctions); (2) rally-around-the-flag effects; (3) fifth-column effects; and (4) the percep-tions of decision-makers in Taiwan on cross-Strait conflicts. As a result, this paper focuses on these four variables in order to assess Taiwan's vulnerability with respect to cross-Strait economic relations.

The hypotheses on the outcome of China's possible sanctions against Taiwan are as follows:

1. As China's military threats increase, Taiwan will experience rising nationalism, a strong "rally-around-the-flag" effect, and a moder-ate fifth-column effect among Taiwan's public, elites, and interest groups.

2. Taiwan's decision-makers emphasize relative gains and reputation (credibility) in the cross-Strait conflict.

The Effectiveness of Signaling and Deterrence

Beijing had four common goals in the 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 incidents: (1) to signal its disapproval of Taiwan's policy; (2) to coerce Tai-wan's leaders to re-adopt the "one-China principle" or give up further

in-dependence activities (i.e., Taiwan's flexible diplomacy); (3) to deter Tai-wan leaders from formally declaring independence; and (4) to discourage the Taiwan electorate from voting for candidates who favored independ-ence (i.e., Lee Teng-hui, Peng Ming-min [彭明敏], and Chen Shui-bian). In addition, Beijing also tried to encourage the United Stated to adopt a more public and determined stance against Taiwan independence in the 1995-1996 crisis.36

These strategies of coercion and deterrence exploited Taiwan's fear of war through military brinkmanship in order to signal Beijing's resolve to halt the momentum toward Taiwan independence. Even though China's official newspaper contended that the political essence of Lee Teng-hui's "state-to-state relations" was the same as Taiwanese independence, Beijing never seriously considered the use of force in the 1995-1996 or 1999-2000 incidents, nor were any serious preparations made for war.

Through its limited deployments of forces to the Strait region during these incidents, China signaled that it did not intend actually to attack Taiwan—China referred to its buildup as "deterrence" against Taiwan in-dependence. China did not deploy the material means to realize an actual invasion. In addition, even Chinese analysts believed that U.S. and Tai-wanese leaders knew from intelligence gathered by U.S. satellite recon-naissance that Chinese intentions were limited to influencing both Tai-wanese leaders and public psychology.3 7

Furthermore, in February 1996 the U.S. embassy in Beijing was in-formed that no attack on Taiwan was planned. In February and March, Li Zhaoxing (李肇星), China's vice foreign minister (and later ambassador to the United States), and Liu Huaqiu (劉華秋), director of the State Council Foreign Affairs Office (國務院外事辦公室), held a series of intensive meetings with officials from the U.S. State Department, the Department of Defense, and the National Security Council. During these meetings, the

36Tung, "China's Economic Leverage," 234-42.

37John W. G arver, Face Off: China, the United States, and Taiwan's Democratization (Seat-tle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 104.

PRC officials gave strong assurances about the limits in time, scale, and location of its military exercises and missile tests. They gave the U.S. gov-ernment explicit assurance that the People's Liberation Army (PLA) would not attack Taiwan and urged the United States to stay out of the cross-Strait quarrel.38

Even the chance for accidental "incidents" to occur was mini-mized. The PLA's Front Line Command strictly ordered the participants not to allow any "unwanted situation to emerge."39

Beijing's assurances truly reflected its intention not to use force be-cause these assurances were made prior to heated missile test exercises in early March 1996 and before the United States deterred China by sending two aircraft carrier groups to the waters near the Taiwan Strait. As a senior scholar in American studies in Shanghai stressed, "The 1995-1996 military exercises were mainly to coerce, bully, and deter Taiwan from declaring independence. China never intended to use force."40

Many prominent Chinese scholars and official have conveyed the same ideas.41

Regarding the effectiveness of signaling and deterrence, Beijing never actually compared military threats with economic sanctions in these two incidents. A senior official of the State Council Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO, 國務院台灣事務辦公室) said: "In 1995-1996, no one mentioned economic sanctions. If Taiwan declares independence, China will direct-ly attack Taiwan. There is no need for economic sanctions."42

A senior scholar in Taiwan studies in Beijing elaborated on the situation: "In 1995-1996, nobody proposed imposing economic sanctions against Taiwan

38Allen S. Whiting, "China's Use of Force, 1950-96, and Taiwan," International Security 26, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 123; Robert S. Ross, "The 1995-96 Taiwan Strait Confrontation: Coer-cion, Credibility, and the Use of Force," ibid. 25, no. 2 (Fall 2000): 108; and Suisheng Zhao, "Military Coercion and Peaceful Offe nce: Beijing's Strategy of National Reunification with Taiwan," Pacific Affairs 72, no. 4 (1999): 511.

39You Ji, "Changing Leadership Consensus: The Domestic Context of War G ames," in Across the Taiwan Strait: Mainland China, Taiwan, and the 1995-1996 Crisis, ed. Suisheng

Zhao (N ew York: Routledge, 1999), 90. 40Personal interview, Shanghai, July 2, 2001.

41Personal interview s w ith various senior scholars and officials in Beijing and Shanghai from June to August, 2001.

because sanctions would hurt TIEs, the Taiwanese people, and China itself, rather than Taiwan independence supporters."4 3

The primary concern for Beijing might be the comparative costs be-tween military threats and economic sanctions incurred by China itself. In the two incidents, military threats did hurt TIEs and the Taiwanese people, not the Taiwan authorities. Economic sanctions might have had the same, albeit more serious, effect. The apparent difference between military threats and economic sanctions is that military threats might be less costly to China than economic sanctions. The costs of sanctions to China itself would have been a loss of 1-3 percent of GDP (as analyzed below), while the costs of military threats to China itself were almost insignificant in the two incidents. This might be the reason why Beijing adopted military threats instead of economic sanctions against Taiwan in the two incidents.

Assessment of the Costs of Sanctions

For China, because of the investment-trade link and the internal-external link in cross-Strait economic relations, there is no essential dif-ference between an embargo against Taiwan, a boycott of Taiwan-made goods, or a freezing or expropriation of Taiwan's investment in China. Since most cross-Strait trade has been driven by Taiwan's investment in China, any impact on the production of TIEs would have significant reper-cussions for cross-Strait trade. Any disruption of trade between Taiwan and China would also have a strong impact on the production activities of TIEs. Therefore, it is unrealistic to distinguish different elements of eco-nomic sanctions in this case. Although a total disruption of cross-Strait trade and investment would represent a worst-case scenario, such an event is possible due to the chain of connections between cross-Strait trade and investment.

China's direct costs in terms of GDP would have been no less than the

potential costs to Taiwan if China had disrupted cross-Strait economic re-lations in 1995 or 1999. The loss due to trade sanctions in terms of GDP for the target or sender is equal to the product of the sanction multiplier— the ratio of the percentage change in GDP to the percentage change in trade— and the size of the initial deprivation experienced by the target or sender nation. Taiwan's trade with China was US$22.5 billion in 1995 and US$25.8 billion in 1999. With a multiplier between 0.14 and 0.35,44

China's economic sanctions would have reduced the welfare of both Tai-wan and China by between US$3.2 billion and US$7.9 billion in 1995, and by between US$3.6 billion and US$9 billion in 1999. In addition, as-suming the value-added by TIEs is 26 percent of output,4 5

the value-added by TIEs would have been about US$8.7 billion in 1995 and US$18.3 billion in 1999. With investment losses added in, the rough direct costs of eco-nomic sanctions for China would have been between US$11 billion and US$15.7 billion in 1995, and between US$21.9 billion and US$27.3 billion in 1999. Both China and Taiwan would have suffered around 1-3 percent of GDP losses with China's economic sanctions46

(see table 1).

This could be an important reason for China not to have imposed sanctions against Taiwan in 1995 or 1999. In particular, the literature on economic sanctions shows that misperception and miscalculation of deci-sion-makers plays a very limited role in decisions to impose sanctions.47

Therefore, China would tend to impose sanctions against Taiwan only when Beijing realizes— after a cautious and thorough calculation of costs to both Taiwan and itself— that sanctions would hurt Taiwan more than China, or the costs of sanctions to China are obviously smaller than those to Taiwan.

44Tung, "China's Economic Leverage," 115-23.

45In 1999, the value of gross industrial output for enterprises funded by Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan was RMB 899.4 billion and the value-added provided by these enterprises was RMB 233 billion, rendering the ratio of value-added to output 26 percent.

46Tung, "China's Economic Leverage," 247-50.

47Of the 114 cases in the H SE database, the only case with greater costs to the sender is Canada's sanctions aga inst Japan in 1974. Canada imposed a c ost of 0.04 percent of Canada's G NP, but a cost of only 0.01 percent of Japa n's GNP.

However, Chinese scholars and officials never conducted a compre-hensive assessment of direct costs of sanctions against Taiwan because in the 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 incidents Beijing never intended to impose sanctions against Taiwan. The majority of Chinese officials and scholars thought that Taiwan would suffer more than China if Beijing imposed eco-nomic sanctions against Taipei. Nevertheless, Beijing did not impose sanc-tions against Taipei (such as blacklisting TIEs) in the 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 incidents.

All evidence leads to the conclusion that, in addition to the relative costs, Chinese leaders attached great importance to the absolute costs of economic sanctions. They worried that economic sanctions would bring a tremendous backlash against China's economic development.48

For in-stance, a senior Chinese official of the Ministry of Foreign Trade and

Eco-48Personal interviews with various senior scholars and officials in Be ijing and Shanghai from June to August, 2001.

Table 1

Direct Costs of China's Economic Sanctions, 1995 and 1999

Unit: US$ billion

Trade losses Investment losses Total losse s GDP Losses/GDP 1995 1999

Taiwan China Taiwan China

3.2-7.9 0 3.2-7.9 257.4 1.2%-3.1% 3.2-7.9 7.8 11-15.7 704.6 1.7%-2.4% 3.6-9 0 3.6-9 295.9 1.2%-3.1% 3.6-9 18.3 21.9-27.3 989.3 2.2%-2.8%

Note : Investment losses refer to direct losses of economic welfare due to Taiwan's

invest-ment in China . Taiwan does not directly incur losses from Taiwane se investinvest-ment in China, yet TIEs do. Nevertheless, the above figures underestimate Taiwan's losses due to China's sanctions against Taiwan. For example, TIEs drive Taiwan's exports to China, re mit rev-enues from China to Taiwan, and expand the scale and specialization of Taiwan's industries. In addition, the above figures also underestimate China's losses, which are focused exclu-sively on the value-added provided by TIEs. For example, TIEs have substantially contrib-uted to China's production tec hniques, management skills, and efficiency gained from re-source allocation and competition.

nomic Cooperation (MOFTEC, 對外貿易經濟合作部) asserted that some scholars and officials in Beijing proposed the disruption of economic ex-change between Taiwan and China in order to punish Taiwan for Lee Teng-hui's state-to-state statement. He also added that Chinese leaders never-theless rejected the idea because the disruption would have seriously hurt China's economic development.4 9

In addition, China has become a critical link in the global commodity chains and a partner in broad international interdependence. Chinese leaders have deep interests in the global economy and a strong sense of vulnerability to global economic shocks. China's imposition of economic sanctions against Taiwan would have disastrous results. As stressed by Andrew S. Grove, chairman of Intel, "It is the computing equivalent of mutually assured destruction [if bilateral economic exchange were dis-rupted under the context of globalization]. You can't hurt the other party without hurting yourself."50

If international economic interdependence and the reaction of third parties, particularly the United States, were calculated into the equation, Chinese perceptions of the relative costs of economic sanctions against Taiwan in the 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 incidents would be reversed. China would suffer enormously, much more than Taiwan.51

Facing Current Problems in China

The challenges (or crises) of the economic, social, environmental, and political situation were acute by 2000. The top Chinese leaders were constantly concerned about both the stability of the country and the pres-ervation of their power. It was not simply a question of how to improve people's living standards and thus the CCP's legitimacy, but a question of

49Comments made at a seminar at the Institute of International Relations, N ational Chengc hi University, Taipei, November 4, 2003.

50Mark Landler, "These Days 'Made in Taiwa n' Often M eans 'Made in China'," New York Tim es, May 29, 2001, A1.

how to avoid major economic, social, environmental, and political crises in China and thus save the country from possible chaos.5 2

For instance, in March 2002 Premier Zhu Rongji (朱鎔基) said in a press conference that if the Chinese government had not adopted its proactive fiscal and prudent monetary policy between 1998 and 2002, "China's economy would proba-bly have collapsed."53

At this point, any domestic or external instability, or a significant slowdown in economic growth, could have led China into chaos.

A senior economist at the State Council Development Research Center (國務院發展研究中心) explained:

The mainland has been e mphasizing the maintenance of stability since the mid-1990s due to staggering e mployment pressure caused by both the reforms of state-owned enterprises and migrants from rural areas. Socia l sta bility can be maintained only through economic development. Mainland China currently is facing immense economic difficulties, however, inc luding financial system reform and non-performing loans, the unemployment problem, income and regional inequality, public finance reform, and industrial development and up-grading. To solve the first four problems, the mainland needs to sustain rapid economic development. For instance, during the Asian financial crisis, the rea-son the mainland implemented active fiscal policy was to solve social contra-dictions, not because leaders preferred high economic growth rates.54

These challenges and fears faced by Chinese leaders must be ad-dressed through: rapid, efficient, and sustainable economic growth, which requires absolute domestic and external stability; sufficient economic, so-cial, and even political reforms; adequate environmental protection; and an international economic and political environment conducive to these domestic priorities. China needs a peaceful and stable international en-vironment in order to develop its economy for at least several decades. In addition, China needs to cooperate with the international community in order to conduct foreign trade and acquire foreign capital and advanced technology.55

52Ibid., 294-365.

53"Comparison— Xinhua Reports on Premier Zhu Rongji New s Conference" (in Chinese), Beijing Xinhua Domestic Service , March 15, 2002, in FBIS-CHI-2002-0315.

54Personal interview, Beijing, July 31, 2001.

With regard to the Taiwan issue, Chinese leaders have similar con-cerns and agendas. As discussed above, the primary concern that led Bei-jing not to impose sanctions against Taiwan as a signal might have been the high costs of economic sanctions. In addition, Beijing's emphasis on the absolute costs of imposing economic sanctions on Taiwan also reflected China's priority of economic development. A senior scholar of interna-tional relations in Beijing explained, "The mainland cannot afford the costs of China's economic sanctions against Taiwan because society would be-come unstable and politics would be thrown into turmoil. For the main-land, cross-Strait economic interests involve the mainland's overall eco-nomic and social stability, as well as the stability of the political regime. The current regime's survival is at stake. The mainland regime dare not take this high of a risk."56

Many Chinese scholars unambiguously argued that Beijing attached great importance to economic development and would not like to sacrifice China's economic development in order to im-pose economic sanctions on Taiwan.57

Interest Groups in China

Over the past twenty years, interest groups have increasingly played an important role in China's decision-making process.58

This paper evalu-ates the influence of interest groups on Chinese decisions not to impose economic sanctions on Taiwan. Here we focus on two groups in particular — TIEs and Chinese localities59

— who have significant interests in cross-Strait economic exchanges.

In order to emphasize the importance of TIEs, President Jiang Zemin

56Personal interview, Beijing, July 19, 2001.

57Personal interviews with various senior scholars in Beijing, Shangha i, and Xiamen from June to July, 2001.

58Suz anne Ogden, Inklings of D emocracy in China (Cambridge, Mass.: H arvard University Asia Center, 2002), 258-317.

59Localities refer to administrative units at the sub-national level, such as provinces, munici-palities, or counties.

(江澤民) visited Kunshan (昆山, a small town outside of Shanghai where many TIEs are located) three times between 1998 and 2001. Jiang even told local leaders in 2001 that mainland China's Taiwan policy should be determined in consultation with TIEs in Kunshan.60

As a result, Chinese call the Taiwan-Invested Enterprises Association (TIEA, 台資企業協會) in Kunshan the fifth local leadership— after the Party, the government, the people's congress, and the people's political consultative conference.6 1

As a leader of the TIEA in Beijing emphasized, "None of the requests by the TIEA has been rejected by Chinese authorities so far. Chinese authorities help TIEs solve as many problems as they can."62

Although the prior statements might overstate their influence on Chinese policymaking, TIEAs and similar associations have been effec-tive in lobbying Beijing for the protection and advancement of their inter-ests in China. As shown below, the lobbying by the Taiwan Electrical and Electronic Manufacturers' Association (TEEMA, 台灣區電機電子工業同 業公會) for their version of the "Implementation Rules for the PRC Law on Protecting Investment by Taiwan Compatriots" (hereafter the "Imple-mentation Rules") in late 1999 clearly elucidates TIEs' political influence. When China was drafting the "Implementation Rules," officials of the TAO, the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS, 海峽兩岸關係協會), and the MOFTEC paid numerous visits to major TIEAs for three years to get their input.63

Before the Implementation Rules were finalized, the TEEMA visited pertinent Chinese officials in August 1999. Since the mid-1990s, Taiwan's investment has focused on elec-tronics and electrical appliances, and the TEEMA represented many

im-60Kunshan officia ls told TIEs about Jiang's excerpt. Author's conversation with a TIE manager in K unshan, July 5, 2001.

61A former Chinese senior official involved with Ta iwan, author's note of a confe rence in Shanghai, July 17, 2002.

62Author's interview with Guo-yuan Chen, secretary-general of the Taiwan-Invested Enter-prises Association in Beijing, July 18, 2001.

63Chuo-zhong Wang, "TIEAs Create Opportunitie s," Zhongguo shibao, August 12, 1996; and Deming Yang, "Comments on the 'Implementation Rules for the PRC Law on Protect-ing Investment by Taiwan Compatriots'," Xiandai Taiwan yanjiou (Contemporary Taiwan Studies), 2000, no. 2:73.

portant TIEs in lobbying the Chinese government. The TEEMA lobbied for their suggestions on the Implementation Rules with Chinese officials article by article.

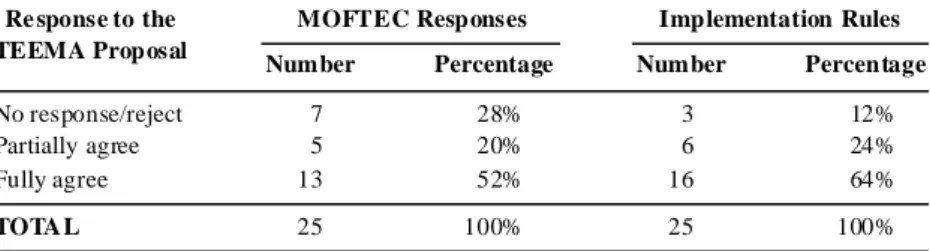

Table 2 is a comparison of the TEEMA proposal of the Implementa-tion Rules, the MOFTEC responses to the TEEMA proposal, and the final Implementation Rules promulgated by the Chinese government four months later. In the original Chinese draft Rules there were thirty-one ar-ticles in total, while the TEEMA lobbied for twenty-five arar-ticles based on their version. At the time of the TEEMA visit to Beijing, the MOFTEC either did not respond immediately to or outright rejected 28 percent of the TEEMA's proposed articles, partially agreed to 20 percent, and fully agreed to 52 percent. In comparison, in the Implementation Rules, the Chinese government rejected only 12 percent of the TEEMA's proposed articles, partially agreed to 24 percent, and fully agreed to 64 percent. That is, the MOFTEC partially or fully agreed to 72 percent of the TEEMA's proposed articles, while the Chinese government partially or fully accepted 88 per-cent of the Implementation Rules. Even after three years of consultation with the TIEAs, the Chinese government generally accepted the majority

Table 2

Comparison of the TEEMA Proposal, MOFTEC Responses, and the Imple-mentation Rules Re sponse to the TEEMA Proposal No response/reject Partially agree Fully agree TOTA L

MOFTEC Responses Implementation Rules Number Percentage Number Percentage

7 5 13 28% 20% 52% 3 6 16 12% 24% 64% 25 100% 25 100%

Sources: Taiwan Electrical and Electronic Manufacturers' Association, "'Taishang touzi

baohufa shishi tiaoli' ji 'sheli Taishang fating' zhi yanjiou jianyi" (Proposal for "the imple-mentation rules for the PRC law on protecting investment by Taiwan compatriots" and "es-tablishing special courts for TIEs") (Taipei: Taiwan Electrical and Electronic Manufac turers' Association, 1999), 23 pages; and "Detailed Implementation Rules for the PRC Law on the Prote ction of Investment by Taiwan Compatriots" (in Chinese), Beijing Xinhua Domestic Service, De cember 12, 1999, in FBIS-CHI-2000-01.

of input from the TEEMA. This shows how influential the TEEMA is in relation to the Chinese government.

During the 1995-1996 and 1999-2000 incidents, Chinese leaders never articulated any threat to impose economic sanctions on Taiwan. To the contrary, Beijing feared that the PRC military threats might have a seri-ous impact on Taiwanese investment in China. At the same time, the Chi-nese government faced tremendous and constant pressure from TIEAs who were both very anxious about cross-Strait instability and resentful of China's military threats against Taiwan. Subsequently, Taiwan's invest-ment in China was greatly reduced, at least temporarily, and TIEA leaders threatened to withdraw their capital from China if Beijing continued its military threats against Taipei. Moreover, some TIEA leaders even threat-ened to return to Taiwan and fight against China if China dared attack Taiwan.6 4

As a result, China— including the Chinese president, premier, minis-ters, TAO officials, ARATS officials, and state media— both made every effort to reassure the TIEs that their interests would be protected under all circumstances and prohibited protests against Taiwan independence after Chen Shui-bian was elected president. In addition, Beijing provided more favorable treatment and legal protection for TIEs, including promulgating the Implementation Rules in late 1999. Moreover, Beijing repeatedly reas-sured TIEs that there would be no war between Taiwan and China.65

Of course, TIE pressure did not alter China's decision to launch mili-tary exercises in late 1995 and early 1996. However, the above assurance that there would be no war undermined Beijing's strategy of deterrence and coercion against Taiwan during these incidents: how could Beijing firmly reassure TIEs that there would be no war, on the one hand, and resolutely

64Personal interviews with: Chi Su, former chairman of Taipei's Mainland Affairs Counc il, May 21, 2001; with Yun-yuan Liaw, director of the Department of Economic and Trade Service, Straits Exchange Foundation, May 22, 2001; and with Huai-jia Luo, executive di-rector of the Industrial Policy Cente r, Taiwan Electrical and Electronic M anufacturers' As-sociation, May 23, 2001. See also Tse -Ka ng Leng, "Dynamics of Taiwan-M ainland China Economic Relations," Asian Survey 38, no. 5 (Ma y 1998): 504-5.