human relations 2014, Vol. 67(8) 947 –978 © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0018726713508797 hum.sagepub.com humanrelations

Modeling team knowledge sharing

and team flexibility: The role of

within-team competition

Hongwei He

University of Strathclyde, UKYehuda Baruch

University of Southampton, UKChieh-Peng Lin

National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan

Abstract

This study examines the role of within-team competition (i.e. team hypercompetition and team development competition) in a team process. We developed and tested a model that associates team collectivism as the antecedent of within-team competition, and knowledge sharing and team flexibility as the outcomes. The model was empirically tested with data from 141 knowledge-intensive teams. The empirical findings showed that team collectivism had a positive relationship with team development competition and a negative relationship with team hypercompetition. Regarding the outcomes, team development competition and team hypercompetition had an indirect relationship with knowledge sharing and team flexibility through team empowerment. We offer a number of original contributions to the team effectiveness literature, especially by showing that team hypercompetition and team development competition have different impacts on team knowledge sharing and team flexibility.

Keywords

knowledge sharing, team collectivism, team empowerment, team flexibility, within-team competition

Corresponding author:

Chieh-Peng Lin, National Chiao Tung University, 10044, Taiwan. Email: jacques@mail.nctu.edu.tw

Teamwork forms a crucial element of work processes (Mathieu et al., 2008; Mitchell et al., 2011; Nielsen and Daniels, 2012; Van Knippenberg et al., 2011). One important within-team interaction that may influence team effectiveness is within-team competi-tion (Tjosvold et al., 2003a), which has generated widespread debate, proposing two contrasting views (Fletcher et al., 2008). One view is that competition helps achieve col-lective outcomes because it encourages people to do their best (e.g. Crawford and LePine, 2012). Another view is that competition is unhealthy, because it discourages people from working together and from helping each other, hence undermining the collective perfor-mance (e.g. Zhang et al., 2011).

This debate largely centers on one assumption about competition – that it is driven only by an aim to maximize personal benefit. This assumption could be problematic, at least for people working within the same team, with a collective goal (Chen et al., 2006; Tjosvold et al., 2004). The theory of personal competitive orientations supports two dis-tinctive types of orientations: hypercompetition (i.e. competing to achieve personal gains and status with little concern for the means and possible harms to others) and develop-ment competition (i.e. competing for team functioning and developdevelop-ment without a pri-mary focus on winning against other team members) (Ryckman et al., 1994, 1996). Similarly, at the team level, within-team competition (i.e. the collective competitive ori-entations of the team members) may be comprised of two dimensions: team hypercom-petition and team development comhypercom-petition. Such a distinction is particularly relevant for teams, because people working on the same team can compete with each other to maximize their personal potential in a constructive way and simultaneously enhance each other’s individual performance and/or team collective performance (e.g. Tjosvold et al., 2003b).

According to the theory of competitive orientation, although much research views competition as mainly counterproductive, such a simplistic view overlooks the fact that not all forms of competition are maladaptive (Collier et al., 2010). People can learn, through the socialization process, to fit into a work group in which they compete with, rather than against, others to accomplish their collective goals (Collier et al., 2010; Sampson, 1988; Wilson, 1993). With the cultivation of development competition among team members, they are able to remain more psychologically healthy by following team rules during their competition with each other and focus on the benefit of the entire team (Ryckman et al., 1997).

Team hypercompetition is characterized by team members’ need to outperform other members on the same team with little concern for the collective benefit. As a result, hypercompetition often causes direct confrontations, as well as indirect hostility, in a zero-sum game in which individuals strive to create personal advantages and disregard the needs of members of the same team. Team development competition, however, reflects a perspective of competition as facilitating team growth. That is, team develop-ment competition stresses a fair contest among team members without hostility, jealousy or anger, and with a superior common goal of team-level achievements and growth as a whole. Development competition primarily focuses on collective growth and teamwork mastery (Ryckman et al., 1996), which offers an opportunity for learning, self-improve-ment and self-discovery (Collier et al., 2010; Ryckman and Hamel, 1992; Ryckman et al., 1996, 1997).

We focused on two outcomes of within-team competition – knowledge sharing and team flexibility – for several reasons. First, an effective team normally requires knowl-edge sharing among team members (Foss et al., 2010; Kirkman et al., 2004; Mathieu et al., 2008). Knowledge sharing refers to ‘sharing task-relevant ideas, information, and suggestions with each other’ (Srivastava et al., 2006: 1241). Within-team knowledge sharing represents the effectiveness of the management of a team (Furst et al., 1999) and influences organizational performance and competitive advantage (Kirkman et al., 2002). Knowledge is a critical asset for organizations (Nonaka, 1994; Staples and Webster, 2008). One important dynamic capability firms need to have to achieve a com-petitive advantage is the ability to boost knowledge sharing among their employees, especially with regard to team tasks (Teece et al., 1997). Yet, knowledge sharing cannot be arbitrarily forced. Team members may have reasons or motivations for hoarding their knowledge and thereby treat it as an important personal asset. Therefore, motivating team members to share their knowledge is a salient, but challenging, issue (Staples and Webster, 2008). Second, effective knowledge sharing requires the synergistic collabora-tion of team members working toward a common goal (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995). For the reasons described above, knowledge sharing involves some level of motivation (Gagné, 2009; Quigley et al., 2007). Within-team competition has the potential motiva-tional power to encourage or discourage team members to share their knowledge (Hansen et al., 2005; Tjosvold et al., 2003a) and it represents a team environment that may affect knowledge sharing within the team (Zarraga and Bonache, 2003).

Second, an effective team requires high levels of team flexibility (Li et al., 2010; Townsend et al., 1998). Team flexibility refers to team adaptation (or ability) by making any adjustments necessary to continue effective responses to changing situations (Li et al., 2010; McComb et al., 2007). Team flexibility is associated with a number of ben-efits, including increased productivity, competitive advantages and enhanced problem-solving competency (Li et al., 2007; Manuj and Mentzer, 2008; Molleman and Slomp, 1999). Team flexibility also helps teams to cope with turbulent and volatile competitive threats effectively and to take advantage of those threats as opportunities (Johnson et al., 2001; Liu and Yetton, 2010). The extant literature has acknowledged the significance of team flexibility across various industries; however, it seldom explains how it is influ-enced by critical team competitive dynamism (Li et al., 2010), such as within-team competition.

Therefore, it is important to examine both hypercompetition and development compe-tition at the team level with regard to their impact on both knowledge sharing and team flexibility, because the functional relationships between these constructs at different lev-els of analysis (e.g. individual vs team levlev-els) can lead to different results (Chan, 1998). This study’s focus on these two different types of competition can complement previous studies about cooperation, which has been widely accepted as a purely positive team-work orientation.

Drawing on the theory of team empowerment, which is derived from self-determina-tion theory (Srivastava et al., 2006), we argue that team empowerment mediates the effect of within-team competition on team knowledge sharing and team flexibility, largely due to the fact that within-team competition may encourage or inhibit intrinsic task motiva-tions (e.g. team empowerment), depending on its orientation of team-development

competition or hypercompetition. Previous studies have emphasized that empowerment is a driver of flexibility (Wellins et al., 1994) and knowledge creation (Yahya and Goh, 2002). For that reason, without a thorough examination of empowerment and its impact on team flexibility and knowledge sharing as key outcomes, our understanding of this construct will remain limited, and organizational initiatives directed at building success-ful teamwork will remain unjustifiable and based on blind faith.

Self-determination theory argues that individuals are motivated to act (e.g. sharing knowledge) based on their inherent growth tendencies and their innate psychological needs (e.g. autonomy, competence and self-development) (Deci and Ryan, 2002). Team empowerment theory posits that when a team is more empowered, team members are more motivated to share their knowledge and enhance the team’s ability to adapt to changing environments and challenging tasks (Srivastava et al., 2006). Testing the medi-ation effect of team empowerment is critical, as (1) team empowerment is motivmedi-ational, so are within-team competition and knowledge sharing; (2) prior research has indeed found that team empowerment affects team knowledge sharing (Srivastava et al., 2006); and (3) team empowerment represents an important intrinsic motivation that stems from within-team competition (Proenca, 2007). Moreover, we add team collectivism as an antecedent of within-team competition and team empowerment. Doing so (1) allows us to control for the effect of team collectivism on team empowerment (Gundlach et al., 2006), while testing the relationship between within-team competition and empower-ment; (2) enables us to confirm that team competition is distinct from its closely associ-ated construct (i.e. team collectivism); and (3) offers a theoretical explanation of team empowerment.

This study offers a number of original theoretical contributions to the existing litera-ture. First, it operationalizes the concept of within-team competition into two-dimen-sional factors and integrates them into a framework explaining the effect of within-team competition on team knowledge sharing and team flexibility. Second, it examines the mediating role of team empowerment in the relationship between within-team competi-tion and team processes, which confirms the motivacompeti-tional power and empowering nature of within-team competition (mainly team development competition). Third, it proposes and empirically tests the effects of team collectivism on within-team competition and team empowerment.

Conceptual background and hypothesis development

Within-team competition

A number of trends in the literature of interpersonal competition and team competition suggest that within-team competition should not be considered unidimensional. First, the extant literature offers mixed results about the relationship between competition and performance/outcomes. Some studies suggest that competition facilitates motivation and performance (Abuhamdeh and Csikszentmihalyi, 2009; Stanne et al., 1999; Tauer and Harackiewicz, 2004), while others demonstrate that competition has a negative effect on group cohesiveness, effectiveness and friendships (Johnson et al., 1981; Tjosvold et al., 2003a). Some research finds that competitive team structure enhances

task speed, but not accuracy, in the experimental context (Beersma et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2006). A few studies indicate that constructive competition does exist and contrib-utes to task effectiveness, social support, strong positive relationships, enjoyment of team experience, desire to participate within a team and confidence in working collabo-ratively with competitors in the future (Fülöp, 2009; Janssen et al., 1999; Tjosvold et al., 2003a). Similarly, the literature on ‘constructive controversy’ suggests that because team members in such a competitive environment are more likely to exchange diverse viewpoints and raise serious issues, team conflict could lead to positive out-comes, such as team performance (Bhatnagar and Tjosvold, 2012), better managerial decision making (Tjosvold et al., 1986), and risk taking and innovation (Tjosvold and Yu, 2007). In addition, research has found that constructively managing team members’ emotions (e.g. anger and annoyance) could lead to positive team outcomes (Tjosvold and Su, 2007). However, meta-analytic evidence (De Dreu and Weingart, 2003) shows that task conflict typically hinders team performance.

Second, at the personal and interpersonal levels, some theorists have proposed vari-ous types of competition that differ in terms of the motivations for competing, the ways in which team members manage competition in their relationships with their opponents, the intensity of the competition, and their emotions during the competition (e.g. Ryckman et al., 1994, 1996). Ryckman et al. (1996) argued that individuals can possess two types of competition: hypercompetition (which could be psychologically harmful) and per-sonal development competition (potentially psychologically healthy). Hypercompetition refers to ‘an indiscriminate need by individuals to compete and win (and to avoid losing) at any cost as a means of maintaining or enhancing feelings of self-worth, with an atten-dant orientation of manipulation, aggressiveness, exploitation, and denigration of others’ (Ryckman et al., 1996: 374–375). Personal development competition is an attitude ‘in which the primary focus is not on the outcome (i.e. winning), but more on enjoyment and mastery of the task’ (Ryckman et al., 1996: 375).

Prior research has examined the impact of interpersonal competition on interpersonal relationships, as well as how interpersonal competition affects intrinsic motivation and performance (Reeve and Deci, 1996; Tauer and Harackiewicz, 2004; Vansteenkiste and Deci, 2003). Different interpersonal competitive attitudes have significant implications for personal performance and interpersonal relationships (Ryckman et al., 1994, 1996, 1997). Competition in the workplace also affects individual employees’ attitudes, stress and performance (Brown et al., 1998). What has been lacking in the literature is twofold. First, there is a scarcity of research on the impact of within-team competition on team knowledge sharing and team flexibility (Hansen et al., 2005; Örtenblad, 2004; Tjosvold et al., 2003a; Van Den Broek et al., 2008). As noted previously, they are important per-formance indicators of effective teams. Second, there is a lack of research on the impact of different types of competition. Nevertheless, a few studies have examined the effects of a team competitive reward structure (Beersma et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2006) and these studies offer some promising initial evidence of the relevance of within-team com-petition to team dynamics, which may have implications for knowledge sharing and team flexibility.

Based on the above reasoning, we propose that within-team competition includes both team hypercompetition (Ryckman et al., 1997) and team development competition

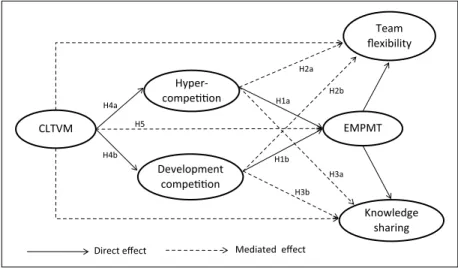

(Ryckman et al., 1996; Tjosvold et al., 2003a). The two types of competition can coexist within a team. For example, a team’s competition can take place among members com-peting for the benefits of both personal gain and team performance; team performance does not necessarily undermine personal gain. However, a team’s competition can be dominated by a prevailing purpose of maximizing personal goals, with only little con-cern for the team’s benefits. Furthermore, we expect that team hypercompetition nega-tively relates to (via team empowerment) within-team knowledge sharing and team flexibility. On the antecedent side, we propose that team collectivism affects within-team competition and empowerment. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model and associated hypotheses this study aims to test. We elaborate on these relationships in the following sections.

Knowledge sharing and team flexibility

Knowledge is an important attribute for successful and effective teams (Foss et al., 2010; Haas and Hansen, 2007; Payne et al., 2009; Srivastava et al., 2006). Knowledge sharing within organizations has been widely examined regarding its motivational factors, such as extrinsic motivations of incentives and expected rewards (Lin, 2007; Quigley et al., 2007), intrinsic motivations of empowerment (Srivastava et al., 2006), coordination mechanisms (Tsai, 2002) and knowledge networks (Hansen, 2002). Although prior stud-ies on knowledge sharing have examined team-level factors (e.g. transactive memory system) (Brandon and Hollingshead, 2004), the dependent variables tend to be either knowledge-seeking behaviors (Hansen et al., 2005) or external knowledge sharing (Cummings, 2004), as opposed to knowledge sharing among team members.

In addition to knowledge sharing, another important team outcome is team flexibility, which refers to team ability (or adaptation) in response to environmental changes to

CLTVM Hyper-compe on Team flexibility Knowledge sharing

Direct effect Mediated effect

EMPMT Development compe on H1a H2a H3a H4a H5 H1b H2b H3b H4b

Figure 1. Conceptual model and hypotheses

ensure survival in the face of uncertainty (Li et al., 2010; McComb et al., 2007). Team flexibility is important because it helps to achieve a number of organizational benefits, such as increased productivity, competitive advantages, profits and market shares (Li et al., 2010; Townsend et al., 1998). It is essential to assess team flexibility as a key team outcome, because within-team competition could have implications (positive or nega-tive) for a team’s capabilities to respond and react flexibly to externally imposed pres-sures (Li et al., 2010).

Within-team competition and team empowerment

Psychological empowerment refers to increased intrinsic task motivation manifested in a set of cognitions reflecting individuals’ orientation to their work roles, such as meaning (i.e. the belief that their work is important), competence (i.e. the perceived ability to perform their tasks), impact (i.e. the degree to which employees feel their work affects the performance of their team) and self-determination (i.e. perceived autonomy at work) (Avolio et al., 2004; Conger and Kanungo, 1988; Spreitzer, 1995a). At the team level, team empowerment is defined as increased task motivation and orientation that result from team members’ collective, self-determined, positive assessments of their organiza-tional tasks (Kirkman and Rosen, 1999).

Team hypercompetition and team development competition have differential effects on team empowerment as, under different competitions, team members are motivated to achieve different ends. Under hypercompetition, individual members are driven to achieve their own personal goals as the first priority, even at the cost of team-related goals. Consequently, team members are more likely to feel that it is dif-ficult to make a meaningful impact on the team or its associated tasks, as their efforts may be undermined by other team members. In addition, hypercompetitive situations can engender negative interpersonal affect (e.g. hatred and aggression) and, thus, have a negative effect on within-team interactions, such as sharing knowledge (Kelly and Barsade, 2001; Sy et al., 2005). Similarly, when a team is hypercompetitive, team members tend to individuate (or isolate) themselves from other team members (Ruscher and Fiske, 1990; Ruscher et al., 1991), which, in turn, undermines the con-ditions necessary for team empowerment, such as a supportive work environment, trust (Kirkman and Rosen, 1999) and subjective well-being (Biron and Bamberger, 2010). Therefore, we hypothesize that team hypercompetition will negatively relate to team empowerment.

Conversely, team development competition stresses the benevolent comparison of achievements among team members and a common goal of team-level accomplishments. First, team development competition is helpful for team empowerment because it intrin-sically motivates team members and enables them to respond to unpredictable demands for change without sacrificing team benefit. Second, under team development competi-tion, team members feel a strong sense of a common goal (Algesheimer et al., 2011; Bosch-Sijtsema et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2006; Mehta et al., 2009; Tjosvold et al., 2004), which, in turn, enhances their intention of positively influencing the team. Prior research shows that interpersonal competition could enhance intrinsic motivation (Abuhamdeh and Csikszentmihalyi, 2009; Tauer and Harackiewicz, 2004). Thus:

Hypothesis 1a: Team hypercompetition negatively relates to team empowerment. Hypothesis 1b: Team development competition positively relates to team empowerment.

Within-team competition, team empowerment and team flexibility

Empowerment has been found to be an important mediator between different types of team climates (e.g. team-member exchange) and team outcomes (e.g. performance, com-mitment) (Aryee and Chen, 2006; Liden et al., 2000; Meyerson and Kline, 2008). Similarly, we expect that the relationship between within-team competition and team flexibility is mediated by team empowerment.

Team flexibility represents a team’s ability to respond to environmental changes and to ensure survival in the face of uncertainty (Li et al., 2010; McComb et al., 2007). Team flexibility facilitates a number of organizational benefits, such as increased team produc-tivity and competitive advantage. Empowerment is effective in fostering team members and enables them to react to environmental changes with flexibility and agility (Kirkman et al., 2004). Empowered teams have the authority to decide what actions to take in order to deal effectively with challenges in a timely manner (Mathieu et al., 2006). In addition, empowered team members feel liberated to better execute job processes, freer to organ-ize their work, and more able to implement different performance strategies and coordi-nate their job activities to meet performance goals. This leads to improved team flexibility (Kirkman et al., 2004). Therefore, those who perceive stronger empowerment within their teams are more cognitively flexible and better at solving problems (Biron and Bamberger, 2010; Swafford et al., 2006). Collectively, when teams are empowered, pro-active behaviors such as flexibility, resilience and persistence occur (Chen et al., 2007). Previous research of empowerment posits that empowerment in workplaces mediates the relationship between the social structural context (e.g. within-team competition) (Russell and Fiske, 2008) and team flexibility (Li et al., 2010; Spreitzer, 1995b). As explained previously (see Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b), team competitions influ-ence team empowerment, which, in turn, has a positive relationship with team flexibility. We expect that team empowerment mediates the relationships between team competi-tions and team flexibility. We do not expect these indirect relacompeti-tionships to be partial mediations, as there are no obvious additional reasons, aside from team empowerment, regarding the ways in which within-team competition influences team flexibility. Thus:

Hypothesis 2a: Team empowerment mediates the negative relationship between team hypercompetition and team flexibility.

Hypothesis 2b: Team empowerment mediates the positive relationship between team development competition and team flexibility.

Within-team competition, team empowerment and knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing prevents the cognitive resources available within a team from being underutilized (Srivastava et al., 2006). Previous studies have proposed empowerment as a critical predictor of team knowledge sharing (e.g. Srivastava et al., 2006). Given that

within-team competition leads to team empowerment, which, in turn, leads to knowledge sharing, we propose that team empowerment acts as a mediator in the path from team competition to team knowledge sharing.

In addition to the indirect effect of within-team competition on knowledge sharing via team empowerment, within-team competition may have a direct relationship with knowl-edge sharing. One major motive for knowlknowl-edge sharing is concern for the team’s develop-ment. Under team development competition with a common collective goal, team members are more likely to engage in knowledge sharing, regardless of whether or not they feel empowered. On the other hand, a major barrier for knowledge sharing is the desire to pro-tect personal knowledge resources (Hansen et al., 2005). Under team hypercompetition, team members are more likely to place their self-interest as the top priority and withhold their knowledge resources. Hence, team development competition tends to encourage knowledge sharing, while team hypercompetition tends to inhibit knowledge sharing.

Hypothesis 3a: Team empowerment partially mediates the negative relationship between team hypercompetition and team knowledge sharing.

Hypothesis 3b: Team empowerment partially mediates the positive relationship between team development competition and team knowledge sharing.

It is important to note that organizational behavior researchers suggest that employ-ees’ sense of empowerment is motivated by organizational characteristics (e.g. com-petition) and it has positive effects on work outcomes (Choi, 2010), such as knowledge sharing and flexibility (Baruch, 1998). Similarly, previous studies indicate that the perception of empowerment is influenced by interpersonal and contextual factors (e.g. development competition among team members), but not vice versa (Tuuli and Rowlinson, 2010).

Team collectivism

Unlike competitive orientation at the personal level, within-team competition (i.e. col-lective competitive orientation in the team work environment) is more malleable than fixed. People may be very hypercompetitive in their daily lives, but they may also adopt a more developmental competitive orientation for the benefit of their team. Similarly, people may adopt a very developmental competitive orientation for the benefit of their personal development. In their team work environment, on the other hand, they could compete for their own benefit instead of the collective benefit of the team. Therefore, within-team competition may be driven by a team collectivist culture that affects compe-tition in work teams (Gardner et al., 2009; Gundlach et al., 2006).

Within-team collectivism refers to the degree to which a team values loyalty, respon-sibility and cohesiveness in the team family (Brewer and Venaik, 2011; Robert and Wasti, 2002). The extant literature indicates that collectivism helps to explain the degree of team orientation to which the members stress teamwork in performing team activities and in making collective decisions (Salas et al., 2005, 2007; Thakkar et al., 2011). Research shows that team collectivism positively relates to effective team functioning

(Dierdorff et al., 2011). Collectivism is associated with a high degree of acceptance of group norms, a strong concern for the well-being of the group, a strong orientation toward group goals and a tendency toward positive social interaction (e.g. within-team competition) in group contexts (Dierdorff et al., 2011; Triandis et al., 1988). A team is likely to be permeated by a collectivist culture when the demands and interests of the team take priority over the desires and needs of the individuals on the team (Triandis and Gelfand, 1998), which is suggestive of a positive influence on team development com-petition and a negative effect on team hypercomcom-petition. Team development comcom-petition can be more easily achieved within a collectivist environment because collectivists look out for the well-being of the entire team, even at the expense of personal interests (Leung and Bond, 1984). Recent research has related collectivism to constructive competition (e.g. Fülöp, 2009).

Team collectivism could have a direct impact on team empowerment (Kirkman and Shapiro, 2001) and subsequently affect knowledge sharing and team flexibility (Gundlach et al., 2006). Given that empowerment represents increased task motivation resulting from team members’ collective assessments of their team’s tasks (Kirkman et al., 2004), teams with a stronger collectivistic culture are more likely to have higher collective psy-chological empowerment. Collectivism favors interdependence with one’s team, sup-porting a tight social framework in which members expect others on their team to look after their interests and protect them when they are in trouble (Sigler and Pearson, 2000). The social support component of collectivism increases psychological empowerment through positive reinforcement of employee actions that assist the team in meeting its goals (Sigler and Pearson, 2000). Thus, even after controlling for the effects of within-team competition, within-team collectivism can still have a significant positive relationship with team empowerment. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4a: Team collectivism negatively relates to within-team hypercompetition. Hypothesis 4b: Team collectivism positively relates to within-team development competition.

Hypothesis 5a: Within-team hypercompetition partially mediates the relationship between team collectivism and team empowerment.

Hypothesis 5b: Within-team development competition partially mediates the relation-ship between team collectivism and team empowerment.

Hypothesis 5c: Team collectivism positively relates to team empowerment.

Methods

Sample and data collection

We conducted a survey of professionals working in hybrid-virtual teams (mainly in the areas of research and development [R&D], management information systems [MIS], human resources management [HRM], marketing and production) of IT firms in Taiwan. Hybrid-virtual teams, compared with pure virtual teams, are teams that rely on both technology-supported virtual channels and face-to-face contacts (Dixon and Panteli, 2010; Fiol and O’Connor, 2005). Virtual platforms of team management are becoming

increasingly pervasive in many intra-organizational and inter-organizational forms (Kirkman et al., 2004; O’Leary and Cummings, 2007; O’Leary and Mortensen, 2010). We selected IT firms due to the ubiquity of virtual teams of professional knowledge workers within IT firms.

Based on prior studies on virtual teams (Kirkman and Mathieu, 2005; Maznevski and Chudoba, 2000), we define a knowledge-intensive virtual team as a virtual relationship of knowledge workers that is mostly conducted over webs of communication technolo-gies and guided by a common purpose of fulfilling certain knowledge-intensive tasks and functions. The typical knowledge-intensive virtual teams surveyed in this study are relevant to test our proposed model, because such teams often have a high potential con-flict of interest among individual knowledge workers and between individual knowledge workers and the team (Alvesson, 2000), making within-team competition a salient issue for knowledge-intensive teams. In addition, both empowerment and knowledge sharing have been considered crucial mechanisms for effective knowledge-intensive tasks (Alvesson, 2000).

A total of 24 large IT firms in two well-known science parks in Taipei and Hsinchu agreed to participate in this study. The firms provided a diverse sample of virtual teams that rely heavily on e-mail, chat tools, online conferencing, instant messaging and other online systems to accomplish their teamwork. We surveyed five members from each team, including four team members and the team leader (or team supervisor). When a leader supervised more than one team, we only surveyed one of his or her teams to avoid confusion. The team leaders randomly distributed four questionnaires (sealed in enve-lopes) to their subordinates, who returned the completed questionnaire directly to onsite research assistants. Of the 775 questionnaires distributed to the members of 155 teams (with an average team size of 12.26 members per team), 680 usable questionnaires from 141 teams were returned, for a questionnaire response rate of 87.74 percent. This high response rate (Baruch and Holtom, 2008) was achieved partially due to a gift voucher incentive. A gift voucher of NT$100 (about US$3.35) was provided to every survey respondent. Regarding the representativeness of our sample with regard to the total pop-ulation, our average team sample represents 41 percent of the total population of all the teams, which could have a potential impact on the accuracy of model estimation results. Nesterkin and Ganster (forthcoming) suggested that such a potential impact could be judged based on the response rate, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (1), and effect size. With an average ICC (1) of our variables being 0.19, and based on their simulation results (see Nesterkin and Ganster, forthcoming: 11), our observed effect sizes could have been underestimated by about 40 percent.

Measures

We measured the constructs in this study using five-point Likert scales ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Most measures were drawn and modified from the existing literature to fit the research context. A number of steps were employed in finalizing the measurement items, which were first refined by three management pro-fessors working in the field. The refined scale items were then translated into Chinese (Brislin, 1970). At this point, we conducted several informal focus groups with executive

MBA students to repeatedly discuss and examine the items’ face validity and representa-tiveness of the two dimensions of within-team competition. Finally, we conducted three pilot studies to assess the quality of our measures and improve item readability and clar-ity. Some items were reworded or removed following exploratory factor analysis of the three pilot studies (subjects were professionals in the IT industry taking evening college classes; n = 59, 73 and 65). Team members, including team leaders – who are also team members – completed all of the measures. This is because the team supervisors are also team members (not external to the teams).

Within-team competition. We developed a seven-item team hypercompetition scale based on the information obtained during an informal focus group with managers (executive MBA students) and by referring to the research outlined above, particularly the personal level constructs of personal hypercompetition (Ryckman et al., 1994), between-partner competitive goals (Wong et al., 2005) and psychological competitive climates (Brown et al., 1998; Fletcher et al., 2008). Items considered inappropriate were reworded by our focus group or removed from our questionnaire after the three pilot tests, using exploratory factor analysis. A sample item is: ‘Our team members have a “win–lose” relationship.’

Based on the same approach, we constructed a four-item team development competi-tion scale, based on the personal development competicompeti-tion scale (Ryckman et al., 1996) and interpersonal constructive competition (Tjosvold et al., 2003a). We referred to two primary attributes of constructive competition: procedure fairness and the low impor-tance of winning (Tjosvold et al., 2003a) and the imporimpor-tance of achieving a collective goal (Tjosvold et al., 2004). A sample item is: ‘Our team members compete with each other with strong sportsmanship.’ The scale of within-team competition was verified via a series of pilot tests among executive MBA students. In an analysis of the main sample, the internal reliability (based on Cronbach’s alpha score) of team hypercompetition was 0.87, and that of team development competition was 0.92. Appendix A lists the measure-ments items for within-team competition.

Team empowerment. We measured team empowerment with nine items from a shortened version of the team empowerment scale from Kirkman et al.’s (2004) empowerment scale, reaching an equivalent internal reliability (based on Cronbach’s alpha score) of 0.93. All items loaded to one global dimension of empowerment. We removed two items due to low item-to-total correlations.

Knowledge sharing. We measured knowledge sharing with a four-item scale based on Lin (2010). In this study, for instance, an original item, ‘I share my job experience with my online coworkers,’ was modified to ‘Our team members share job experiences with one another.’ The internal reliability (based on Cronbach’s alpha score) of this construct was 0.94.

Team flexibility. We measured team flexibility using four items modified from Ryu et al.’s (2007) measure to fit the team context. The original scale was developed by Heide and John (1992) to measure manufacturer–supplier relationship flexibility as a dimension of relationship norms. Ryu et al. (2007) added one additional item to the original three items. Because team flexibility (in our study) deals with the within-team relational

norms, we modified the items slightly for this study. For example, an original item, ‘Both our company and this supplier expect to be able to make any adjustments necessary to cope with changing circumstances,’ was modified to ‘Our team members are able to make any adjustments necessary to cope with changing circumstances.’ We checked the face validity of the modified items with pertinent professors and executive MBA student focus groups. The internal reliability (based on Cronbach’s alpha score) was 0.94. Team collectivism. We measured team collectivism with seven items slightly reworded from the organizational collectivism scale developed by Robert and Wasti (2002). For example, an original item, ‘Once someone is hired, the organization takes care of that person’s overall welfare,’ was reworded slightly to ‘Once someone is hired, the team takes care of that person’s overall welfare.’ To ensure that we measured collectivism at the team level, we clearly instructed the respondents to refer to their work teams when answering pertinent questions. The internal reliability (based on Cronbach’s alpha score) was 0.91.

The quality of survey data mainly depends on (1) the nature of the questions asked and (2) the intention and characteristics of the sample subjects (Fetters et al., 1984). Our data collec-tion pertinently meets these two criteria. First, our measurement items were drawn and modi-fied from previous studies, and then refined and validated by focus groups and three pilot studies. Second, during the survey, we obtained strong support from our sample firms, whose personnel departments carefully helped distribute the anonymous questionnaires to team leaders who expressed willingness to volunteer, and then traced the status of the returned questionnaires. Moreover, a gift voucher was provided to every participant to motivate their discreet responses. These procedural measures helped to reduce the potential bias of careless or non-purposeful responding. As a result, we had to remove only eight observations that were deemed to be careless or non-purposeful responses. We also checked whether partici-pants were members of interdependent teams with a shared objective. First, only enduring teams with clear, shared objectives and tasks were selected. Second, only team members who contributed to the core functions of the teams were invited to participate in the survey. Measurement properties. We performed a number of tests to confirm the validity of the measures of within-team competition for the main study at the individual respond-ent level. First, we tested the validity of the scales for within-team competition. Because we obtained only one large sample, we randomly split the sample into halves. We used the first half of the sample (n = 349) to conduct confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), using maximum likelihood estimation (AMOS 18). The proposed two-factor model (team hypercompetition versus team development competition) achieved a good fit: χ2 = 116.782 (43), χ2/d.f. = 2.714, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.961, con-firmatory fit index (CFI) = 0.961 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.070. All factor loadings were significant and above a 0.50 threshold, with an average variance extracted (AVE) score for team hypercompetition of 0.51 and an AVE score of 0.55 for team development competition. The square roots of both AVE scores were higher than the correlation between the two factors (r = -0.41) (For-nell and Larcker, 1981). In contrast, a one-factor model (combining two factors into one factor) had an extremely poor fit: χ2 = 462.946 (44), χ2/d.f. = 10.521, IFI = 0.779, CFI = 0.777 and RMSEA = 0.165.

Second, we used the full sample to test the CFA model for all the measures. The model achieved an adequate fit: χ2 = 1762.594 (480), χ2/d.f. = 3.672, IFI = 0.911, CFI = 0.910 and RMSEA = 0.062. All factor loadings were significant and above a 0.50 threshold, with adequate AVE scores: team hypercompetition (0.55), team development competi-tion (0.51), team collectivism (0.53), team empowerment (0.53), team knowledge shar-ing (0.74) and team flexibility (0.69). The square roots of all AVE scores were higher than the correlations of all the possible pairs involving any focal variables. Thus, discri-minant validities were supported. This, in turn, largely supports the absence of severe common method bias. To provide further evidence to the CFA, we then conducted a multi-group CFA using both the first and second halves of the sample, which showed no significant differences in the model fit between the two samples (p > 0.10). To further test the common method bias, we first ran a one-factor model (a CFA version of Harman’s single factor test) that loads all indicators to a common factor. This model was extremely poor: χ2 = 7428.055 (495), χ2/d.f. = 15.006, IFI = 0.515, CFI = 0.517 and RMSEA = 0.142. We then conducted a series of model comparisons, comparing the proposed six-factor CFA model with a series of five-six-factor CFA models that combined our focal vari-ables (either team hypercompetition or team development competition) with one of the remaining variables. Appendix B presents the model comparisons, which show that the proposed model is superior to all of the other competing measurement models.

Results

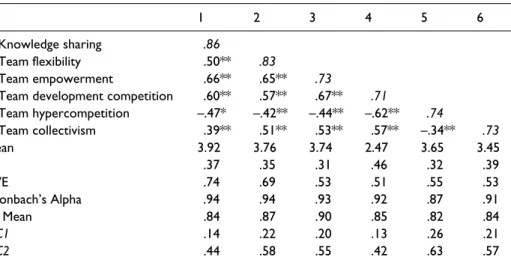

We checked the inter-rater agreement coefficients (rwg: James et al., 1984) before aggre-gating individual measures into team-level aggregate measures. The coefficients of rwg

(mean) for each construct were 0.82 or larger (see Table 1), which were all higher than the

cutoff value of 0.70, confirming a strong inter-rater agreement (James et al., 1984). In addition, we calculated both ICC (1) and ICC (2) (see Table 1). ICC (1) measures the inter-rater reliability, representing the amount of variance in any one individual’s response that can be explained by group membership. All ICC (1) values exceeded the accepted cutoff value of 0.12 (De Jong and Elfring, 2010; Glick, 1985), ranging from 0.13 to 0.26. ICC (1) should be used as the primary base for deciding appropriateness of aggregating perceptual variables into group-level data (James, 1982). ICC (2) measures the reliability of group means and is highly subject to the number of respondents per team; therefore, its value should not be assessed alone (De Jong and Elfring, 2010; James, 1982). Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, including rwg, ICC (1) and ICC (2), at the team level.

To test the proposed model at the team level, we applied the partial aggregation approach of structural equation modeling, as it better suits small samples (Bentler and Chou, 1987). At the team level, the sample size was n = 141, but there were over 35 original observed items. Partial aggregation approach enhances the model fit without weeding out any items and meets the criterion of the sample size requirement at the team level (Bentler and Chou, 1987; Little et al., 2002). We ran a CFA with the team level data and the CFA model achieved an acceptable fit: χ2 = 230.479 (120), χ2/d.f. = 1.921, IFI = 0.957, CFI = 0.957 and RMSEA = 0.081. The AVE scores of all latent vari-ables were above the 0.50 threshold. All AVEs were higher than the squared correlations of any two focal variables, which supports the discriminant validity test (Fornell and

Larcker, 1981). We also tested the common method bias at the team level, following the same procedure as that used at the individual level. One factor CFA model was extremely poor: χ2 = 1272.986 (135), χ2/d.f. = 9.430, IFI = 0.559, CFI = 0.556 and RMSEA = 0.245. Appendix B (see the lower part of the table) also presents the model comparison results at the team-level analyses. The proposed six-factor structure was clearly superior to all of the other models.

We employed structural equation modeling to test our model (see Figure 1). Initially, we added a number of team control variables (i.e. team ratios in gender, age, education and expatriate members), with none being a significant predictor, and removed them for the sake of model parsimony. The model achieved an adequate fit: χ2 = 283.787 (121), χ2/d.f. = 2.345, IFI = 0.936, CFI = 0.936 and RMSEA = 0.098. Table 2 also presents the model fit comparison between the proposed model and a couple of competing models, the explanation for which can be found in the notes for Table 2.

Hypotheses testing

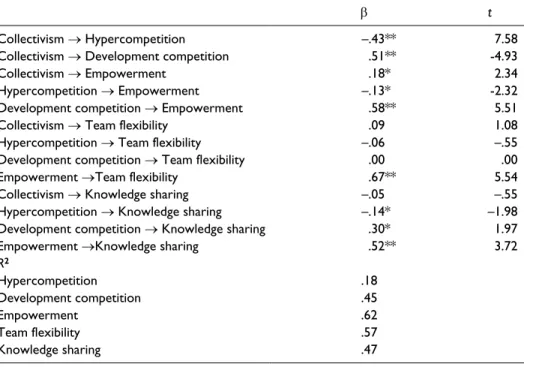

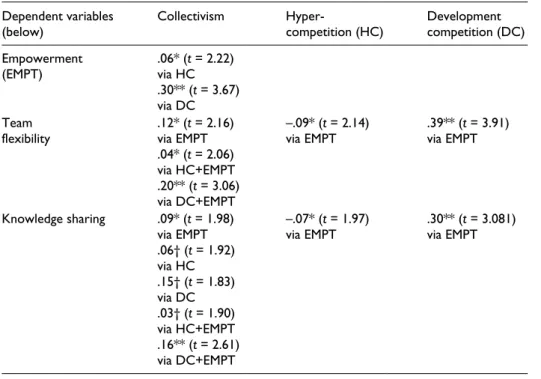

Table 3 presents the estimation results for the proposed model. We calculated the size and significance of the indirect effects based on Sobel tests (Baron and Kenny, 1986; MacKinnon et al., 2007). Table 4 presents indirect effects. Figure 2 presents a visual model with the significant direct and total significant indirect effects.

Effects of within-team competition. Hypothesis 1a states that team empowerment is nega-tively influenced by team hypercompetition. Hypothesis 1b states that team empower-ment is positively influenced by team developempower-ment competition. Both hypotheses are supported (β = -0.13, p < 0.05 and β = 0.58, p < 0.01, respectively; see Table 3).

Table 1. Team level descriptive statistics.

1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Knowledge sharing .86

2. Team flexibility .50** .83

3. Team empowerment .66** .65** .73

4. Team development competition .60** .57** .67** .71

5. Team hypercompetition –.47* –.42** –.44** –.62** .74 6. Team collectivism .39** .51** .53** .57** –.34** .73 Mean 3.92 3.76 3.74 2.47 3.65 3.45 SD .37 .35 .31 .46 .32 .39 AVE .74 .69 .53 .51 .55 .53 Cronbach’s Alpha .94 .94 .93 .92 .87 .91 rwg Mean .84 .87 .90 .85 .82 .84 ICC1 .14 .22 .20 .13 .26 .21 ICC2 .44 .58 .55 .42 .63 .57

AVE = Average variance extracted. Diagonal represents square roots of AVE scores. *p < .05

Table 3. Results of structural models.

β t

Collectivism → Hypercompetition –.43** 7.58

Collectivism → Development competition .51** -4.93

Collectivism → Empowerment .18* 2.34

Hypercompetition → Empowerment –.13* -2.32

Development competition → Empowerment .58** 5.51

Collectivism → Team flexibility .09 1.08

Hypercompetition → Team flexibility –.06 –.55

Development competition → Team flexibility .00 .00

Empowerment →Team flexibility .67** 5.54

Collectivism → Knowledge sharing –.05 –.55

Hypercompetition → Knowledge sharing –.14* –1.98

Development competition → Knowledge sharing .30* 1.97

Empowerment →Knowledge sharing .52** 3.72

R2 Hypercompetition .18 Development competition .45 Empowerment .62 Team flexibility .57 Knowledge sharing .47 †p < .10 *p < .05 **p < .01 Two-tailed test

Hypothesis 2a states that team empowerment mediates the effects of team hypercom-petition. Hypothesis 2b states that team empowerment mediates the effect of team devel-opment competition on team flexibility. Both hypercompetition and develdevel-opment competition are significantly related to team empowerment (see Table 3, β = -0.13, p < 0.05 and β = 0.58, p < 0.01, respectively). In addition, team empowerment is positively

Table 2. Structure model fit comparison.

χ2 d.f. χ2/d.f. IFI CFI RMSEA Comparison note

Proposed model 283.787 121 2.345 .936 .936 .098 Base model

Competing model 1 292.323 123 2.377 .935 .934 .099 Δχ2=8.536/2d.f., p = .014

Competing model 2 329.251 123 2.677 .920 .919 .109 Δχ2=45.464/2d.f., p < .000

Note:

‘Competing model 1’ is a model that assumes only indirect effect of within-team competition on knowledge sharing via team empowerment without direct effects.

‘Competing model 2’ is a model that assumes only direct effect of within-team competition on knowledge sharing without indirect effects via team empowerment.

related to team flexibility (β = 0.67, p < 0.01). Indirect effect tests (see Table 4) show that both Hypotheses 2a and 2b are supported (β = -0.09, p < 0.05 and β = 0.39, p < 0.01, respectively). However, when team empowerment is controlled for in the full model (see Table 3), neither hypercompetition nor development competition significantly relates to team flexibility (β = -0.06, NS and β = 0.00, NS, respectively), which suggests a full mediation relationship among within-team competition, team empowerment and team flexibility.

Hypotheses 3a and 3b state that team empowerment mediates the effects of (a) team hypercompetition and (b) team development competition, respectively, on knowledge sharing. Hypotheses 3a and 3b are supported (β = -0.07, p < 0.05 and β = 0.30, p < 0.01, respectively; see Table 4). In addition, both team hypercompetition and team develop-ment competition have direct effects on knowledge sharing (β = -0.14, p < 0.05 and β = 0.30, p < 0.05, respectively; see Table 3), suggesting that team empowerment partially mediates the effects of within-team competition on knowledge sharing.

Effects of collectivism. Hypotheses 4a and 4b state that team collectivism (a) negatively affects team hypercompetition and (b) positively influences team development competi-tion, respectively. Hypothesis 4a and Hypothesis 4b are supported (β = -0.43, p < 0.01

Table 4. Significant indirect effects. Dependent variables

(below) Collectivism Hyper-competition (HC) Developmentcompetition (DC)

Empowerment

(EMPT) .06* (t = 2.22)via HC

.30** (t = 3.67) via DC Team

flexibility .12* (t = 2.16)via EMPT

.04* (t = 2.06) via HC+EMPT .20** (t = 3.06) via DC+EMPT

–.09* (t = 2.14)

via EMPT .39** (t = 3.91)via EMPT

Knowledge sharing .09* (t = 1.98) via EMPT .06† (t = 1.92) via HC .15† (t = 1.83) via DC .03† (t = 1.90) via HC+EMPT .16** (t = 2.61) via DC+EMPT –.07* (t = 1.97)

via EMPT .30** (t = 3.081)via EMPT

†p < .10 *p < .05 **p < .01 Two-tailed test

CLTVM Hyper-compe on Team flexibility Knowledge sharing

Direct effect Full media on

EMPMT Development compe on -.13* (-.09) -.14* (-.07) -.43** .18* (.36) .58** (.39) .30* (.30) .51** .67** .52** (.36) (.49) Par al media on Figure 2. Model with path coefficients.

Note: Only significant effects are shown. In-bracket shows the total significant indirect effects. Detailed coefficient estimations of the indirect paths are available in Table 4. CLTVM = Collectivism; EMPMT = Team Empowerment.

and β = 0.51, p < 0.01, respectively; see Table 3). In addition, Table 4 shows that team collectivism has significant indirect effects on team empowerment via both team hyper-competition (β = 0.06, p < 0.05) and team development hyper-competition (β = 0.30, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypotheses 5a and 5b are supported.

Hypothesis 5c states that team collectivism positively relates to team empowerment. Hypothesis 5c is supported (β = 0.18, p < 0.05). Finally, team collectivism also has sig-nificant indirect effects on both team flexibility and team knowledge sharing (see Table 4 for detailed paths), which suggests that team empowerment mediates the effects of team collectivism on both team flexibility and team knowledge sharing.

Discussion

Previous research offers a limited understanding of the effect of within-team competition on team flexibility and knowledge sharing. We proposed that within-team competition comprises two distinct dimensions: team hypercompetition and team development com-petition. In addition, we modeled the effects of within-team competition on team flexi-bility and team knowledge sharing by stressing the pivotal mediating role of team empowerment. We also integrated team collectivism as an antecedent of within-team competition. This study offers a number of original contributions to the literature.

First, this research contributes to the debate on the impact of within-team competition on team processes. Prior research studies offer competing views regarding the desirabil-ity of within-team competition (Fletcher et al., 2008), with one view suggesting that it motivates team members to work harder (Crawford and LePine, 2012) and a contrasting view believing that it discourages members from working together and undermines the

collective performance (Zhang et al., 2011). To address these seemingly irreconcilable opinions, this research extends the theoretical lens of within-team competition to under-stand knowledge sharing and team flexibility. Prior research at the interpersonal level suggests that competition can be both hypercompetitive and self-developmental (Ryckman et al., 1994, 1996). Our study extends this interpersonal competition typology to the team level and proposes within-team competition as a synonymous, two-dimen-sional construct. Doing so contributes to the explanation of the mixed results of the effects of within-team competition in the extant literature. Similar to the effects of com-petitive orientation at the personal level, team level comcom-petitive orientations play similar positive and negative roles in team effectiveness, in that team hypercompetition tends to be detrimental to the team, while team development competition tends to contribute to team effectiveness.

Second, drawing on the theory of team empowerment (Srivastava et al., 2006), we support a motivational-empowering (ME) power of within-team competition on team processes. This ME power of competition suggests that team empowerment acts as a mediation mechanism between within-team competition and team knowledge sharing and team flexibility. However, our research found that after controlling for the effect of team empowerment, within-team competition still has a significant relationship with team knowledge sharing. This finding suggests that team empowerment is not the only mechanism for within-team competition to affect knowledge sharing. This is not surpris-ing, as team development competition aligns the self-interest with the common team interest, thus encouraging knowledge sharing; team hypercompetition, however, inhibits knowledge sharing so that team members might protect their own interests though pre-serving knowledge resources. On the other hand, team empowerment was found to medi-ate fully the relationship between within-team competition and team flexibility, which suggests that the strength of the ME power of within-team competition differs, depend-ing on the specific team processes or outcomes.

Third, we offer an integrated framework of various factors (e.g. team collectivism, within-team competition and team empowerment) and their impact on knowledge shar-ing and team flexibility. The theoretical framework of this research places within-team competition as the pivotal factor of team dynamics. While previous studies have indi-cated that organizational members may hoard knowledge, the mechanisms (e.g. within-team competition) that prevent them from doing so have not been elucidated (Hansen et al., 2005). Although prior research suggests the existence of an important relationship between collectivism and empowerment (e.g. Downing et al., 2003; Kirkman and Shapiro, 2001), few studies examine their relationship at the team level or identify the mechanism. Our research supports the concept that team collectivism positively relates to team empowerment, partly due to its impact on within-team competition. In sum-mary, our research confirms, for the first time, the empowering role of team collectiv-ism in team processes and supports the concept that within-team competition helps explain this empowering effect. Due to the partial nature of the mediation role of within-team competition in the relationship between within-team collectivism and within-team empower-ment, future research should aim to identify other mechanisms of the empowering effect of team collectivism.

Managerial implications

Our findings add to managerial knowledge by unveiling the role and relevance of within-team competition in facilitating within-team knowledge sharing and within-team flexibility. This study conceptualizes two essential elements of competition and clarifies the mechanisms through which competition may be effectively used or reduced. Knowledge about the influential processes of within-team competition becomes critical as management increasingly counts on teamwork to achieve organizational goals, despite the fact that motivating teamwork is never simple (Srivastava et al., 2006). Managers who wish to make good use of a reward structure for within-team competition should be able to iden-tify the difference between development competition and hypercompetition. For example, cut-throat competition may unexpectedly emerge if managers unintentionally push hypercompetition without knowing about the existence of development competition, which actually plays a major role in improving knowledge sharing and team flexibility. Employers, managers and team leaders should recognize the role and relevance that team competition plays in the teamwork process. Such realization may be reflected in better team empowerment, as well as increased team knowledge sharing and team flexibility. In particular, we advocate making a clear distinction between team hypercompetition and team development competition; the latter provides positive team processes, while the former results in a negative impact. Therefore, management should not simplify the concept of team competition too much. Management may have to accommodate both the positive and negative effects of competition when overseeing the different competitions that may occur among team members. We argue that it is a challenge to reach team devel-opment competition, while the outcomes justify the efforts of a team. Factors enabling positive outcomes can be enhanced by generating and encouraging a collectivistic team culture, as our results show that team collectivism relates to team development competi-tion positively and team hypercompeticompeti-tion negatively, which, in turn, influences team empowerment and outcomes positively and negatively, respectively. We argue that man-aging team competition is especially important for knowledge workers (Alvesson, 2000), such as professors working in research-intensive universities and institutes, consultants working on team projects and various knowledge workers working in IT firms (as dem-onstrated by our sample). Collectivism is a spirit that can be substantially enhanced if team members are given the opportunities to strengthen such spirit through team activi-ties, such as participation in decision making, pursuit of common goals and sharing teamwork responsibility. Meanwhile, managers can plan social events for their teams in an informal setting, such as lunch on a set day of each week or a pleasant outing every few months. While praising individuals’ experience, special skills or quality of work, managers should keep reminding their subordinates that everyone is expected to embrace a ‘one-for-all, all-for-one’ spirit within the team.

Our empirical results indicate that empowerment is a critical checkpoint for manage-ment when evaluating the impact of competition on team knowledge sharing and team flexibility. We point out a move from empowering individuals (Thomas and Velthouse, 1990) to empowering entire teams. Given that competition is inevitable in a team, the status of empowerment may be an important signal for management to relieve the potential negative effect of harmful competition in a timely manner. To improve the performance of

teams, management needs to take the concept of empowerment seriously and find ways to encourage positive competition within teams. Firms should empower teams in their decision making and allow teams to be flexible and self-managed.

Limitations and future research

First, we acknowledge that the study is limited in terms of generalizability, as it took place in one country (Taiwan) in a particular culture (the Far East). Future research should examine further antecedents beyond within-team competition. It may be important to compare key success factors of teamwork across Asian and western countries by using the framework of this study. Second, future research can examine how firm-level variables (e.g. a firm’s culture, market strategies, outsourcing strategies, resource allocation and alliances) influence team-level development competition and hypercompetition. Third, this research draws upon the literature on team competition and its relevant theories to predict some team processes. Yet, there is a parallel literature on team interdependency that could be related to team competition. For example, task interdependence is defined as the degree to which completing tasks requires the interaction of team members (Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007). Similarly, outcome interdependence is defined as the degree to which individuals perceive that their goals are interdependent with each other (Ghobadi and D’Ambra, 2013). These two streams of research could be integrated in a way that leads team interdependence to team competition. Future research can explore how to integrate these two constructs to build a more comprehensive and integrative model.

Fourth, this study used a sample of hybrid virtual teams. In our sample, teams are rela-tively homogeneous in terms of their degrees of virtuality. However, it might not always be the case; it would be particularly interesting to examine how team virtuality would affect team dynamism along with within-team competition (Kirkman and Mathieu, 2005; Staples and Webster, 2008). Fifth, the data collected to test our theoretical model are cross-sectional by nature. Therefore, caution needs to be taken in claiming the causal relationships. Although this research and some prior research have supported significant relationships among the variables in question, there is a lack of definitive data on the causal direction of these relationships. To establish the causal relationships more firmly, future research should adopt an experimental or longitudinal research design. In a longi-tudinal design, for example, future research can measure within-team competition and its dependent variables at different time waves, in the follower order: within-team competi-tion (wave 1), team empowerment (wave 2) and team knowledge sharing and team flex-ibility (wave 3). In an experimental design, different interventions can be randomly assigned to different teams to induce different types of within-team competition. Such interventions may involve introducing different team policies on how team members can compete with one another and/or confederates (if ethically appropriate) to create differ-ent within-team competitions for differdiffer-ent teams. Measures of team processes and out-comes can then be captured at different stages after the intervention. Sixth, this study is limited by the use of a common source method, in that we measured all variables with a single survey instrument. Future research would benefit from applying multiple sources and/or a longitudinal design to collect the data. Finally, the results of this study need to be interpreted in terms of the potential impact of the nonresponse rate of the

team members. As noted in the Methods section, our average team sample represents 41 percent of the total population of all teams, which could make our observed effect sizes underestimated by 40 percent (see Nesterkin and Ganster, forthcoming: 11). Despite these limitations, this research makes valuable contributions to the literature by opera-tionalizing the concept of within-team competition into two-dimensional factors and integrating them into a framework that explains how they relate to important team pro-cesses (i.e. team empowerment, team knowledge sharing and team flexibility).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to convey their deepest gratitude and thanks to the three anonymous reviewers and the associate editor (Professor Terry Beehr) for their most constructive review comments and suggestions during the review process.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

Abuhamdeh S and Csikszentmihalyi M (2009) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the competitive context: An examination of person–situation interactions. Journal of Personality 77(5): 1615–1635.

Algesheimer R, Dholakia UM and Gurău C (2011) Virtual team performance in a highly competi-tive environment. Group & Organization Management 36(2): 161–190.

Alvesson M (2000) Social identity and the problem of loyalty in knowledge-intensive companies. Journal of Management Studies 37(8): 1101–1124.

Aryee S and Chen Z (2006) Leader-member exchange in a Chinese context: Antecedents, the mediating role of psychological empowerment and outcomes. Journal of Business Research 59(7): 793–801.

Avolio BJ, Weichun Z, Koh W and Bhatia P (2004) Transformational leadership and organiza-tional commitment: mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25(8): 951–968.

Baron RM and Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psycho-logical research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51(6): 1173–1182.

Baruch Y (1998) Empowerment models in organizations. Career Development International 3(2): 82–87.

Baruch Y and Holtom B (2008) Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations 61(8): 1139–1160.

Beersma B, Hollenbeck JR, Humphrey SE, Moon H, Conlon DE and Ilgen DR (2003) Cooperation, competition, and team performance: Toward a contingency approach. Academy of Management Journal 46(5): 572–590.

Bentler PM and Chou CP (1987) Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research 16(1): 78–117.

Bhatnagar D and Tjosvold D (2012) Leader values for constructive controversy and team effec-tiveness in India. International Journal of Human Resource Management 23(1): 109–125. Biron M and Bamberger P (2010) The impact of structural empowerment on individual well-being

and performance: Taking agent preferences, self-efficacy and operational constraints into account. Human Relations 63(2): 163–191.

Boland RJ and Tenkasi RV (1995) Perspective making and perspective taking in communities of knowing. Organization Science 6(4): 350–372.

Bosch-Sijtsema PM, Fruchter R, Vartiainen M and Ruohomäki V (2011) A framework to analyze knowledge work in distributed teams. Group & Organization Management 36(3): 275–307. Brandon DP and Hollingshead A (2004) Transactive memory systems in organizations: Matching

tasks, expertise, and people. Organization Science 15(6): 633–644.

Brewer P and Venaik S (2011) Individualism-collectivism in Hofstede and GLOBE. Journal of International Business Studies 42(3): 436–445.

Brislin RW (1970) Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1(3): 185–216.

Brown SP, Cron WL and Slocum JW Jr (1998) Effects of trait competitiveness and perceived intraorganizational competition on salesperson goal setting and performance. Journal of Marketing 62(4): 88–98.

Chan D (1998) Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. Journal of Applied Psychology 83(2): 234–246.

Chen G, Kirkman BL, Kanfer R, Allen D and Rosen B (2007) A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology 92(2): 331–346. Chen G, Tjosvold D and Liu C (2006) Cooperative goals, leader people and productivity values:

Their contribution to top management teams in China. Journal of Management Studies 43(5): 1177–1200.

Choi G-Y (2010) The influence of organizational characteristics and psychological empower-ment on secondary traumatic stress of social workers working with family violence or sexual assault survivors. National Symposium on Doctoral Research in Social Work. 22nd, Ohio State University. College of Social Work.

Collier S, Ryckman RM, Thornton B and Gold JA (2010) Com-petitive personality attitudes and forgiveness of others. Journal of Psychology 144(6): 535–543.

Conger JA and Kanungo RN (1988) The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Academy Of Management Review 13(3): 471–482.

Crawford E and LePine J (2012) A configural theory of team processes: Accounting for the struc-ture of taskwork and teamwork. Academy of Management Review 38(1): 32–48.

Cummings JN (2004) Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organi-zation. Management Science 50(3): 352–364.

De Dreu CKW and Weingart LR (2003) Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 88(4): 741–749. Deci E and Ryan R (eds) (2002) Handbook of Self-determination Research. Rochester, NY:

University of Rochester Press.

De Jong BA and Elfring T (2010) How does trust affect the performance of ongoing teams? The mediating role of reflexivity, monitoring, and effort. Academy of Management Journal 53(3): 535–549.

Dierdorff EC, Bell ST and Belohlav JA (2011) The power of ‘we’: Effects of psychological col-lectivism on team performance over time. Journal of Applied Psychology 96(2): 247–262. Dixon KR and Panteli N (2010) From virtual teams to virtuality in teams. Human Relations 63(8):

1177–1197.

Downing CE, Gallaugher JM and Segars AH (2003) Information technology choices in dissimi-lar cultures: Enhancing empowerment. Journal of Global Information Management 11(1): 20–39.

Fetters W, Stowe P and Owings J (1984) High school and beyond, a national longitudinal study for the 1980s: Quality of responses of high school students to questionnaire items (NCES 84–216). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.