A CASE STUDY OF HOW A LARGE MULTILEVEL EFL WRITING CLASS EXPERIENCES AND PERCEIVES MULTIPLE INTERACTION ACTIVITIES

by

Hsien-Chuan Lin

B.A., Tamkang University, 1985

M.A., University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, 1990

A Dissertation

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree

Department of Curriculum and Instruction in the Graduate School

Southern Illinois University Carbondale December 2009

Copyright by Hsien-Chuan Lin, 2009 All Rights Reserved

DISSERTATION APPROVAL

A CASE STUDY OF HOW A LARGE MULTILEVEL EFL WRITING CLASS EXPERIENCES AND PERCEIVES MULTIPLE INTERACTION ACTIVITIES

By Hsien-Chuan Lin

A Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

in the field of Curriculum and Instruction

Approved by: Dr. Lynn C. Smith, Chair

Dr. D. John McIntyre Dr. Marla H. Mallette Dr. Tamara L. Yakaboski

Dr. Laura J. Halliday

Graduate School

Southern Illinois University Carbondale August 10, 2009

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF

Hsien-Chuan Lin, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Curriculum and Instruction, presented on August 10, 2009, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

TITLE: A CASE STUDY OF HOW A LARGE MULTILEVEL EFL WRITING CLASS EXPERIENCES AND PERCEIVES MUTIPLE INTERACTION ACTIVITIES

MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Lynn C. Smith

The purpose of this study was to examine students’ experiences and perceptions of

multiple interaction activities (self-directed, peer, and teacher feedback) implemented in a

large multilevel EFL writing class in one private technological university in the southern

part of Taiwan. Large size writing classes, quite common in private institutions of higher

education in Taiwan, cannot be effectively operated to meet individual students’ needs in

improving their writing performance. Low achievers have difficulties in keeping up with

competent writers in learning writing skills while advanced students complain of their

learning too little from the class.

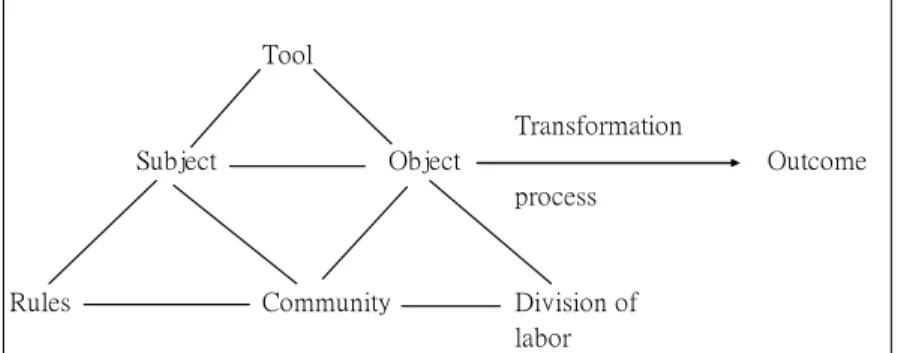

This research, based on the activity system model proposed by Engestrom (1987),

was a case study in which interviewing student participants, observing classroom activities,

audiotaping peer response sessions, and examining students’ drafts and feedback sheets

were the methods to collect data. The qualitative software, ATLAS.ti, was employed to

analyze interview and peer response data according to the code lists developed for this

purpose. A rubric was developed to examine the changes students made after having

incorporated the three types of feedback into their drafts.

Major findings indicated that intermediate and low achievers, though making more

efforts in conducting self-directed feedback, felt unsatisfied with this activity while high

achievers, investing less energy and time, gave more positive opinions to this activity.

However, intermediate and low achievers gave a higher percentage of satisfaction to peer

response activities than high achievers because the former could obtain more constructive

peer feedback than the latter. In addition, all students were in favor of modified teacher

feedback but gave negative opinions to traditional teacher feedback. On the whole,

intermediate and low achievers, based on their preference, ranked teacher feedback the

most important, then peer feedback and finally self-directed feedback whereas high

achievers placed teacher feedback first, self-directed feedback second, and peer feedback

last.

Student writers’ responses to each type of feedback were closely related to the

amount of constructive comments they received. The more helpful suggestions they

obtained, the more positive opinions they gave to a certain type of feedback. In the end of

the study, recommendations were made for curriculum designers, classroom practitioners,

and further studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Lynn Smith, my advisor, for the

help, encouragement, and guidance throughout my doctoral program and all stages of my

dissertation. Her encouragement empowered me to overcome all challenges presented in

the process of completion of my dissertation. Her suggestions were indispensable for me

to improve this dissertation. I would like to show my appreciation to all my committee

members. In the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, special thanks go to Dr. John

McIntyre for his valuable comments on my dissertation and his initiating me into the

world of Lev Vygotsky, Jerome S. Bruner, Ralph W. Tyler, David Ausubel, Benjamin

Bloom, Arthur W. Combs, and so on. If there had not been an opportunity of contact with

these great minds, my dissertation would have lacked the solid theoretical foundation to

support its arguments. I wish to express my special thanks to Dr. Marla Mallette for her

help with refining the research questions of my dissertation and her valuable comments.

Many thanks go to Dr. Tamara Yakaboski in the Department of Educational

Administration and Higher Education for her assistance in delimiting the boundary of my

dissertation, improving the research design, and ushering me into the world of qualitative

research. I would like to thank Dr. Laura Halliday in the Department of Linguisticsfor her

insightful comments on my dissertation and her introducing me into how to teach ESL

iv

composition. Her generosity in lending me her new books related to the field of ESL

composition will forever be the most unforgettable event in my memory.

A special word of thanks goes to all the staff at Morris Library for their outstanding

services. Through the interlibrary service, I was able to get journal articles and books for

my dissertation. Appreciation is extended to Dr. Christina Voss in the Department of

English for her insightful comments and proofreading my writing. Her wit and her sense

of humor are the oasis in the dry process of completing the dissertation.

The researcher would like to express his sincere gratitude to all student participants

and their instructor, Yu-Chi Yang, who made this study possible. In the Department of

Foreign Languages, special thanks go to Chen-ling Wang, Li-ying Lin, Li-hui Lee, Jane-wei

Hu, and other faculty members for their help. Much appreciation is extended to Dr. I-Fan

Chang, President of Fooyin University, for his offering me the opportunity of advanced

studies and financial aid for the first two years. Special thanks go to Professor Lien-Hsiang

Lin for his persistent encouraging me to enter the doctoral program and his writing letters of

recommendation for me.

A special word of thanks goes to my wife, son, and daughter for their support and

encouragement. Without my wife’s shouldering all responsibilities of educating two children

v

PAGE

ABSTRACT...i

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... iii

LIST OF TABLES...xi

LIST OF FIGURES ... xiii

CHAPTERS CHAPTER 1 – Introduction...….1

Content...1

The Researcher’s Motivation...4

The Background of Large Writing Classes...6

Some Major Problems in Large EFL Writing Classes...8

Purpose of the Study ...9

Research Questions...12

Significance of the Study ...12

Delimitations and Limitations...14

Definitions of the Terms Used in the Study...18

Organization of the Study ...19

CHAPTER 2 –Literature Review ...21

Higher Education System in Taiwan ...21

Rationale Justifications for Peer Response ...25

Process Writing Theory...26

vi

Interaction and Second Language Acquisition ...36

Cultural-Historical Activity Theory...39

The Evaluation of Peer Response Implemented in ESL/EFL Writing Classrooms ...47

Some Principles for Effective Peer Interaction...49

The Debate over the Effects of Teacher Feedback ...51

The Problem of Appropriating Student Text ...53

Issues about Writer Autonomy ...57

Previous Empirical Studies of Peer Response ...61

Instruction (Training) for Peer Response ...62

Cultural Impact on Peer Response ...66

Comparative Studies on Self-Directed, Peer, and Teacher Feedback ...69

Types of Peer Interaction ...72

Cultural-Historical Activity Theory...75

Summary of Chapter Two...78

CHAPTER 3 – Methodology...80

The Researcher’s Justification ...81

Participants and Setting...84

Research Design...86

Restatement of the Purpose and Research Questions ...87

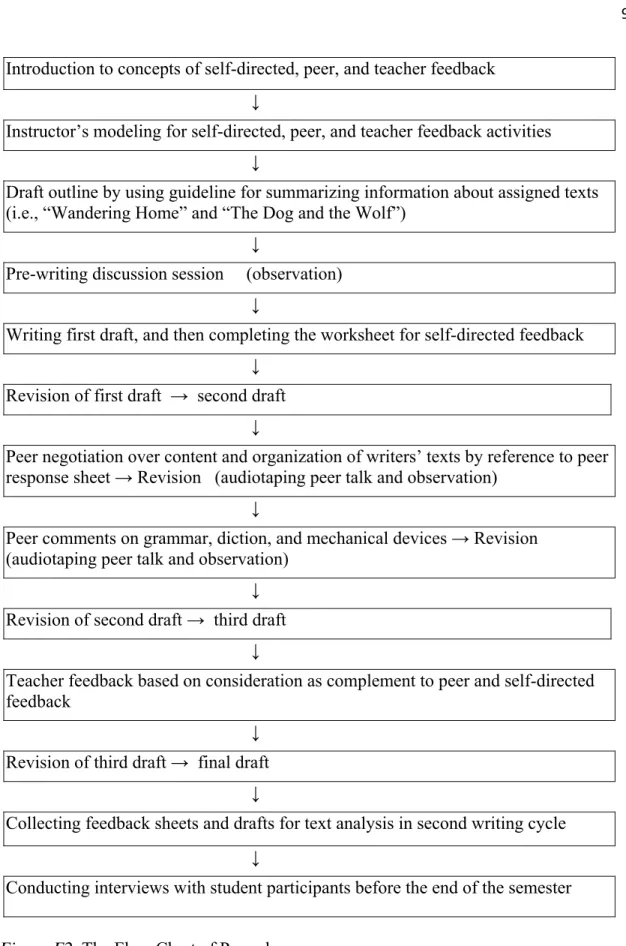

vii Sampling Method...91 Instruments...92 Procedures...95 Data Analysis ...98 Verification of Interpretation ...103 Ethical Considerations ...104 Subjectivity Statement ...105

Summary of Chapter Three...108

CHAPTER 4 – Presentation and Analysis of Data...110

Students’ Responses to Pre-Writing Discussion...110

Journal of Classroom Activities Related to Pre-Writing Discussion ...111

Students’ Perceptions of Pre-Writing Discussion as Shown in Interviews...113

Conclusion ...118

Students’ Perceptions of Self-Directed Feedback...118

Students’ Opinions about Self-Directed Feedback in Interviews...119

General Response to Self-Directed Feedback...119

Students’ Concerns about Self-Directed Feedback...127

Students’ Suggestions for Improving Self-Directed Feedback ...133

viii

the Worksheets ...140

Conclusion ...146

Student Writers’ Opinions about Peer Feedback ...147

Peer Response Sessions ...148

Survey on Peer Response Activity ...166

Student Participants’ Opinions about Peer Response Activity in Interviews ...172

Peer Comments Incorporated into Revision ...186

Conclusion ...197

Students’ Responses to Teacher Feedback ...199

Student’s Responses to Teacher Feedback as Shown in Interviews...199

Participants’ Perceptions of TTF and MTF ...199

Students’ Concerns about MTF ...207

Strategies to Deal with the Lack of Clarity of the Teacher’s Comments ...212

Student Writers’ Incorporating Teacher Feedback into Revision ...216

Conclusion ...227

Students’ Views about Self-Directed, Peer, and Teacher Feedback...229

Students’ General Perceptions of Three Types of Feedback...229 Students’ Opinions about the Necessity and Preference of

ix

A Review of Students’ Revised Drafts...246

Conclusion ...247

Summary of Chapter Four ...249

CHAPTER 5 – Summary, Discussion, and Recommendations ...253

Summary of the Study ...253

Discussion ...259

Pre-Writing Discussion...260

Self-Directed Feedback...261

Peer Feedback ...266

Teacher Feedback ...273

Participants’ Responses to Three Types of Feedback as a Series of Writing Activities ...277

Recommendations...279

Curriculum Designers ...279

Classroom Practitioners ...280

Researchers ...283

Contributions of the Study ...285

REFERENCES ...288

APPENDICES ...307

Appendix A – Schedule for Multiple Interaction Activities...308

Appendix B – Students’ Level of Language Proficiency ...313

x

Appendix E – Peer Feedback Sheet ...316

Appendix F – Teacher Feedback Sheet ...318

Appendix G – Feedback Revision Sheet ...319

Appendix H – Observation Protocol...320

Appendix I – Interview Protocol for Students ...321

Appendix J – Research Questions and Data Collecting Methods...322

Appendix K – Code List for Student Interview in Multiple Interaction Activities ...323

Appendix L– Code List for Peer Response Sessions ...329

Appendix M – Evaluation Criteria for the Feedback Effect on Students’ Revised Drafts...330

Appendix N – Wandering Home...332

Appendix O – The Dog and the Wolf ...334

Appendix P – Reprint Permission from Dr. Engestrom ...336

xi

TABLE PAGE

Table 1 Number of Higher Education Institutions and Students in Taiwan ...2 Table 2 Students’ Responses to Pre-Writing Discussion in Interviews ...117 Table 3 Student Participants’ Perceptions of Self-Directed Feedback in

Interviews ...126 Table 4 Students’ Concerns about Self-Directed Feedback in Interviews ...132

Table 5 Students’ Suggestions for Improving Self-Directed Feedback Activity ... ...139 Table 6 Students’ Perceptions of Self-Directed Feedback as Shown on the

Worksheets ...144 Table 7 Students’ Performance of Self-Directed Feedback as Shown on the

Worksheets ...145 Table 8 Characteristics of Peer Response Sessions...166

Table 9 A Survey of Students’ Perceptions of Peer Response Activity...172 Table 10 Student Participants’ Opinions about Peer Response Activity in

Interviews ...184 Table 11 Student Writers’ Incorporating Peers’ Comments into the Revised

Drafts ...195 Table 12 Students’ Perceptions of Modified Teacher Feedback and Traditional

One ...206 Table 13 Student Writers’ Concerns about the Modified Teacher Feedback ...211

xii

Table 15 Student Writers’ Incorporating Teacher Feedback into Final Drafts ...226 Table 16 Students’ General Perceptions of SF, PF, and TF ...235 Table 17 Student Participants’ Preference for Feedback Type ...243 Table 18 Relationship between Preference of Feedback Type and Language

xiii

FIGURE PAGE

Figure F1 Engestrom’s extended Activity System Model...40 Figure F2 The Flow Chart of Procedures ...97

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

This study was designed to explore the experiences and perceptions of students after the implementation of a combination of self-directed, peer, and teacher feedback in a large multilevel English as a Foreign Language (EFL) writing class in a private

university in the southern part of Taiwan. The activity system model developed by Engestrom (1987) was used as the theoretical framework to describe the multiple interaction activities in an EFL writing class. This model, based on Vygotsky’s (1978, 1986) concepts of artifact-mediated and object-oriented actions and of internalization/ externalization, had been developed by Vygotsky’s students and followers to explore the mutual influence among seven elements—subject, rules, community, tools, object, division of labor, and outcome—in human activity, especially useful to understand the concepts such as action, activity, and operation. A detailed description of the activity system model is provided in Chapter Two. This introductory chapter consists of (1) the context under which this study is conducted, including the researcher’s motivation, the background of large writing classes in private education institutions, and some major problems in large EFL writing classes, (2) purpose of the study, (3) research questions, (4) significance of the study, (5) delimitations and limitations, (6) definitions of terms used in this research, and (7) organization of the study.

Context

Taiwan is a resource-poor island-state with limited land for living, agriculture, and industrial and business development. The only way for economic development is to

cultivate highly qualified manpower (brain power) for societal and business needs through higher education. With the revocation of martial law in 1987, the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan was no longer a government organization that had higher education under its total control (Mok, 2002). Instead, MOE now plays the roles of facilitator and coordinator by devolving powers to national and private higher education institutions in four aspects: personnel management, academic freedom, finance, and curriculum (Mok, 2002). As a result of this new educational policy, a rapid expansion in the number of universities and colleges developed from 105 in 1987 to 162 in 2009. Of the 162 universities and colleges, 109 are private schools. Of all students in higher education, more than 75% are enrolled in the private sector, as shown in Table 1 (Department of Statistics, MOE, 2009).

Table 1

Number of Higher Education Institutions and Students in Taiwan

School year Institution number Student number

_____________________ ______________________________ University Junior Total University Junior Total and college college and college college

1986 28 77 105 184,729 244,482 429,211 Private 13 56 69 115,478 190,946 306,424 (%) (71.4%) 2008 147 15 162 1,006,102 117,653 1,123,755 Private 97 12 109 739,320 105,499 844,819 (%) (75.2%)

Source: The website of Department of Statistics, MOE in Taiwan 2009

According to Lee (2004), the Taiwan government spent about 19.70% of the total budget on educational expenditure in 2002. The educational budget for higher institutions accounted for 34.97% of the educational expenditure. In addition to democratization, there are other reasons for the opening of new private institutions. First, the state has

difficulty financing all higher education sectors with more social demands, individual needs, and manpower development plans for higher education provision. The use of private resources is one strategy the state uses to cope with the lack of public resources (Wang, 2003). Therefore, a shift from elitism to mass higher education is one tendency of higher education policy. Next, the expansion of the private sector in higher education can relieve the stress experienced by secondary school leavers and their families (Wang, 2003). Taiwan has been deeply influenced by Confucianism that “puts a premium on education” (Wang, 2003, p. 272). Education, especially higher education, is not only a means of social movement (advancement) but also a way for self-realization (success). In the age of elite education, high school students must go through a highly competitive joint entrance examination to be admitted to a limited number of universities. Therefore, the call for mass higher education from society is predictable. Finally, the growing

impact of globalization affects the educational policy in Taiwan. In order to make Taiwan more competitive in regional and international trade markets, the government needs to change its governance philosophy. Therefore, the policies of decentralization,

privatization, and marketization have been adopted in higher education provision (Mok, 2002). The policy of using private resources to deal with social and individual demands has led to the opening of new private institutions in Taiwan. The prosperity of private institutions is not all rosy. The low quality of private education is one of growing public concerns in the process of shifting from an elite to a mass system (Wang, 2003). The major reason for low education quality in the private sector is the lack of educational resources. In general, the gaps in the educational resources between the public and the private sectors are major factors to sway the quality of education produced. The public

sector has advantages in items such as the ratio of the number of students to teachers, the unit cost per student, library volumes, number of academic staff with a Ph. D., campus and accommodation areas, and cheaper tuitions when compared with the private sector (Wang, 2003). The advantages of educational resources in the public sector attract students with higher academic performance to enroll into different fields of study. As a contrast, students going to private institutions are not as proficient as those studying in public institutions in terms of academic performance, attitude toward and motivation of learning, and self-image.

The Researcher’s Motivation

In order to be competitive in international trade markets, not to be isolated from international society, and to let students have opportunities to pursue individual dignity, values, and learning needs, the Taiwan government believes that higher education is an important way to achieve these goals. In higher education, learning English is especially essential for the purpose of international communication, business, and understanding. Learning English as a foreign language has become very popular with many Asian countries in the past three decades. Taiwan is no exception to this global phenomenon. Many colleges focus their attention and enthusiasm on the development of the students’ English proficiency, due to the gradually forming global village or just out of the motivation, viewing English as an instrument for specific purposes (e.g., international trade, tourism, advanced studies in English-speaking countries, information and technology advancement for careers). Some scholars in Taiwan have been involved in doing research in the aspects of reading (e.g., Huang, 1998; Kung, 2008; Su, 2008; Wei,

1999), listening (e.g., Chang & Read, 2006, 2007; Chien, 1998; Shang, 2005, 2008), speaking (e.g., Hsu & Chiu, 2008; Sun, 2008; Yang, 2007), writing (e.g., Cheng, 2008; Lee & Krashen, 2002; Liu & You, 2008; Min, 2005, 2006; Tseng, 2004), and translation (e.g., Cai, 2007). Of all these five basic language skills, writing instruction, especially in large multilevel classes, is a field still worthy of a deep and detailed investigation.

It is understood that research in the pedagogy of English composition shows fruitful achievement in English-speaking countries. Is it feasible to transplant all the research results on learning and teaching strategies to Taiwan? Writing in the first language (L1) is different from that in an ESL (English as a Second Language) /EFL language not only because of the varied syntactical expressions but also because of the cultural influence on language and thought (Silva, 1993). The ways of one’s thinking and perception of the world are potentially influenced by the language one uses (e.g., culture and language influence each other, a view of Moderate Whorfianism, Chandler, 1995). How to adapt applicable composition theories and practices to Taiwan's learning environment is a job worthy of study, and this is especially true for the case of the private higher education sector.

A writing class with 30 students is already regarded as a large class (Hess, 2001) in the United States; nevertheless, a writing class with 45 or more undergraduates is not an unusual case in most of the private colleges in Taiwan. Could it be that the classroom activities that work in English-speaking colleges are also feasible in those classes of Taiwan? Should a process-oriented or a product-oriented approach be the guideline in a large multilevel EFL writing class? How to provide teacher response to 45 students’ papers in a time-saving, but at the same time feedback-comprehensible way, is a

challenge to EFL writing instructors. Some ESL researchers even suggest that error correction contributes nothing significant to improving students’ writing ability (Lee, 2003; Truscott, 2004) and, therefore, instructors need not go to great lengths to grade students’ papers. Can this be equally applied to the case of teacher feedback on EFL students’ writing?

In addition, what kind of role does cultural, social, economic, and political

background knowledge play in the process of writing in English? For the low-level EFL students, is guided writing preferable to free writing, or should equal attention be paid to both of them in a writing class? How do students’ attitudes, motivation, goals, and language proficiency influence their perceptions and experiences of writing activities? In short, the aim of the present study is to examine the perceptions and experiences of EFL students about the multiple interaction activities carried out in a large multilevel writing class in which students had differing attitudes toward writing, motivations to write, goals for writing, language proficiencies, personal and world knowledge, and personality traits.

The Background of Large Writing Classes

There are several reasons why large writing classes are common in most private colleges of Taiwan. First, budgets are not large enough for private institutions of higher education to build more classrooms on campus or to hire more teachers to reduce class size. The government does not place a high priority on educational resources and funds in the annual national budget because of shifting priorities or a “crowding out effect” (Lu, 2002). Expenditures on environmental protection, national defense, and social welfare are “crowding out” higher education funding. This “crowding out effect,” together with slow

economic growth, difficulty in raising funds, and the rising number of universities, is draining the government’s existing educational resources (Lu, 2002). The government does not give subsidies equally to the public and the private sectors. The national universities and colleges receive about one-third of the total expenditure each year from the state (Mok, 2002) while the private ones obtain only a much smaller proportion of the subsidy. The principle for subsidy distribution to private institutions of higher education is based on the results of assessment of school administration operation, faculty

publication of academic research, curriculum and instruction, and the degree of

internationalization (student and professor exchange programs, cooperation with other international universities, attendance at international conferences, etc.). In general, the government adopts the policy that private sectors in higher education should self-manage their own finances by devolving to them the rights to increase tuition fees between 5% and 5.5% each year (Mok, 2002), to invest monies of their University Funds to earn more interest for operations (Lee, 2004), to recruit adult students for life-long learning

programs, and to raise funds through different channels.

Another reason for the existence of large writing classes is that teachers cannot persuade school authorities to adopt smaller classes for English composition because policy decision-makers decide to lower the cost by increasing student numbers in writing classes after taking the school’s tight budget into consideration, or because they do not have language learning background knowledge, or because there is not enough campus space to build new classrooms in the crowded urban city areas.

Some Major Problems in Large EFL Writing Classes

The major issue of a large EFL writing class lies in the quality and quantity of classroom interaction between the instructor and the students as well as between student and student. One typical case of teacher-student interaction is that low-achieving students have little opportunity to improve their writing abilities and tend to be weaker in class because they do not get much help from their teacher’s instruction and interaction which corresponds to the vicious cycle of the “Matthew Effects” where the poor get poorer and the rich get richer (Merton, 1968, as cited in Stanovich, 1986). Moreover, higher

achievers become bored because the class, in their opinion, is designed for intermediate students. Hence, they feel they do not learn anything challenging.

Another disadvantage of a large multilevel class is that the students get little teacher feedback because the instructor does not have enough time to allot to each student. The instructor has a hard time monitoring all the students and checking their work because of the constraints of time. Also the issue of evaluating writing is very labor intensive for an instructor compared to grading a multiple choice exam, for example. Other shortcomings of a large-sized class are related to classroom management. It is hard for the instructor to manage so many students in the classroom in terms of learning and individual behavior. It can easily get noisy, and it is difficult to keep classroom discipline effectively in a large class. In addition, it is also hard to develop a good rapport between the teacher and the students. If a teacher does not know the students by being able to call their names and understand their learning situations, it is difficult for the students to develop a close bond and view the teacher as a significant other in the learning process. This situation may lead to a decrease in students’ motivation to learn. One common problem in a large class,

according to Nunan & Lamb (1996), is that a teacher is unable to deal well with “the two-zone problem”—those students who sit in the front of the class may have the academic advantage of teacher-student interaction while those in the back cannot see or hear instructional activities clearly, and tend to be demotivated (pp. 147-148).

The interaction between student and student also discloses the disadvantageous features of a large class. First, shy students feel hesitant to interact with others in a large class due to too many strangers making them uncomfortable. Second, pair or group activities are hard to conduct because the teacher is unable to keep a close eye on each pair or group; therefore, the learning style tends to be individualized. Finally, most students who have been under the influence of “teacher talk” (Nunan & Lamb, 1996, pp. 61-67) for many years are used to being receivers of knowledge, not active participants in classroom activities. In addition, to be modest and avoid self-assertion is one of the characteristics seen in the cultural teachings of most Asian countries (Hall, 1976). This cultural influence contributes to the ineffectiveness of communication in a large Taiwanese class.

Purpose of the Study

This study aimed to explore the experiences and perceptions of students after the implementation of a series of self-directed, peer, and teacher feedback activities in a large multilevel EFL writing class in a private university in the southern part of Taiwan. The theoretical framework of this study was based on the activity system model (Engestrom, 1987) to describe the responses of the participants to the multiple interaction activities. The instructor, with the help of the researcher, provided the students with guidelines and

worksheets for these three types of feedback activities, coupled with information about all related rationales for the activities and modeling how to become involved in the actions and operations. The researcher intended to examine the responses of the participants to self-directed, peer, and modified teacher feedback and the potential pedagogical implications that could be drawn from their experiences and perceptions of multiple interaction activities to shed light on composition instruction for large multilevel EFL writing classes in other private higher education institutions.

The studies conducted by other researchers on self-directed, peer, and teacher feedback show quite diverse findings. Some studies show positive evaluation for the implementation of peer interaction, self-directed, and teacher feedback while others offer criticism. Most studies were conducted with small numbers of participants, homogeneous groups, or random grouping. No research was dedicated to examining the experiences and perceptions of the participants in multiple interaction activities in a large multilevel EFL writing class. Compared to the smaller class sizes in previous research, could the implementation of peer response be as beneficial to students in a large writing class with students so differing at the levels of language proficiency, motivation, and background knowledge? After the peer interaction activities, what kind of teacher feedback could supplement what peer response could not provide for the writers’ revisions? Could self-directed feedback benefit students in the development of written competence and gradually help students become independent writers?

The participants in this study included 43 English-major students with different levels of language proficiency, attitudes toward writing, and motivation. The researcher adopted heterogeneous grouping (eight students per group in a pre-writing session and

four students per group in a peer response session, rather than peer review dyads) based on students’ writing ability and friendship. There were several reasons for adopting peer response groups instead of peer review dyads: first, peer response groups can provide writers with more comments from diverse angles on their essays than peer review dyads (Brannon & Knoblauch, 1984; Spear, 1984). Second, the relationship in a peer response group is horizontal (equal status among group members); a peer review dyad, on the other hand, is hierarchical (tutor and tutee) (Damon, 1984; Sharan, 1984; Slavin, 1980, cited in Mendonca & Johnson, 1994). Third, larger groups are more suitable for

brainstorming because of “the increased range of abilities, knowledge, experience, and skills available,” and they are easier for the teacher to manage in a classroom (Liu & Hansen, 2002, p. 62). Finally, peer review dyads are impractical for implementation given classroom space constraint and classroom management issues.

The multiple interaction activities consisted of (1) students’ outlining the main ideas

of the text by following guidelines and checking lists before coming to the class for the pre-writing session, (2) group members’ discussing how to generate ideas and

organization for the draft in the pre-writing session, (3) a self-directed feedback activity implemented after the first draft, (4) peer review and negotiation on peers’ second drafts in peer response sessions, and (5) teacher feedback on the third draft. In general, the guideline (Appendix B) and feedback sheets (Appendices C, D, and E) served to raise the writers’ awareness of the writing process in the hope of helping them to eventually be self-regulated writers. In short, the purpose of this study was to examine if the use of peer interaction, coupled with self-directed feedback and teacher feedback, would help

Research Questions

In view of the preceding research purpose, five research questions were addressed in this study:

1. How do EFL students react to pre-writing discussion sessions on generating ideas and organization?

2. What are EFL students’ perceptions of self-directed feedback in the process of revision?

3. What do student writers think of written and oral feedback from peers in peer response sessions? How do they deal with peer comments in their subsequent revisions?

4. How do EFL students respond to the teacher feedback on their revised drafts?

5. What do EFL students think of these three types of feedback (self-directed, peer, and teacher)?

Significance of the Study

A fairly large body of literature exists on peer review in the field of ESL/EFL writing since the process-oriented approach was introduced from L1 composition pedagogy to the L2 setting in the late 1980s (Berg, 1999b). However, within that

literature, there is a surprising lack of information about the experiences and perceptions of the students related to peer response in a large multilevel EFL writing class. Most studies were conducted in small classes, focusing on the effects of training for revision and writing quality (Berg, 1999b; Min, 2005, 2006), on comparing the effects of peer and

teacher feedback (Miao, Bedger, & Zhen, 2006; Zhang, 1995), on cultural impact on peer response group interaction (Carson & Nelson, 1994, 1996; Ramanathan & Atkinson, 1999), on student interaction and negotiation in peer response sessions (Nelson & Murphy, 1992; Villamil & De Guerrero, 1996), on reader stances during peer response (Lockhart & Ng, 1995), and on the influence of teacher feedback on student revision (Ellis, 2009; Ferris, 1997, 2006; Sheen, 2007; Sugita, 2006). This study attempted to supplement the findings of those earlier studies. The processes for performing the feedback activities were similar to the empirical studies discussed in Chapter Two (literature review) in that the focal points were on the training of students, the teacher’s modeling how to interact with peers in a constructive way, the provision for guidelines and feedback sheets, and the need for multiple feedback on multiple drafts and revisions. It differed from previous studies, however, in exploring the experiences and perceptions of the participants, the ways students were placed into groups, how cultural influence worked on the interaction among peers (Do EFL students [e.g., in Taiwan] with shared values, customs, and beliefs perform peer response activities differently from ESL students [e.g., in the United States] with diverse cultural backgrounds?), and how the process-oriented approach to writing was conducted by means of self-directed feedback, peer comments, and teacher feedback together, not simply by any one of them (Jacobs, Curtis, Braine, & Huang, 1998).

It was hoped that answering the above research questions, in accordance with the experiences and perceptions of diverse participants, would contribute to the holistic understanding of whether a combination of three types of feedback in process-oriented writing would be feasible in a large multilevel EFL writing class, and consequently

inform instructional practice and further studies to lessen the disadvantages of large writing classes in private institutions of higher education in Taiwan.

Delimitations and Limitations

Two delimitations can be found in this research. First, this study confined itself to a large multilevel EFL writing class in a private university in the southern part of Taiwan. Second, this study was limited to twenty-four student informants to investigate their experiences and perceptions of the multiple interaction activities in a large writing class, rather than, as some empirical studies had done, to probe the causes of the improved quality and the revision types of writing texts.

Seven particular limitations may have impacted this study: First, the findings of this research, based on the experiences and perceptions of 24 student participants in a private university, may not be generalized to other writers in other contexts due to the limited number of participants, the length of study period, the writers’ multilevel language proficiencies, and the individual differences in motivation, attitude, goal, and personal experiences and knowledge. Second, due to the human and subjective nature of

qualitative research, the findings and data may be subject to other interpretations. Third, since the students’ language proficiencies, knowledge and beliefs, goals, and motivation varied, it was possible for the advanced and average students to gain benefits from multiple interaction activities, but difficult for the lower achievers to improve their attitudes toward writing, motivation to learn, and personal goals in only one semester (18 weeks). The implementation of multiple interaction activities made certain lower

self-perception had been developed in a longitudinal process, not in a few months, but for several years. The direct consequence of the Matthew Effects created a negative self-image in the writers’ minds, just as Arthur W. Combs argued, "[m]ost important changes in the self-concept probably occur only as a consequence of many experiences repeated over long periods of time” (1978, p. 25).

Fourth, a few advanced students became impatient about the implementation of peer response activities due to the fact that students in private institutions of higher education are charged higher tuition and miscellaneous fees when compared with those students in the public sector (Liu, Chou, & Liu, 2006). The advanced students regarded peer interaction as an activity to teach lower achievers without learning anything

significant themselves from the instructor. This cost-benefit consideration from students influenced the effectiveness of the multiple interaction activities in some groups.

Fifth, cultural influence made some students reserved with regard to their comments on peers’ writings in peer response activities. In Beyond Culture (1976), Edward T. Hall categorized cultures into high-context and low-context. The high-context culture,

common in the eastern cultures, values the groups over the individuals. A strong sense of tradition makes the shared values change little over time. To be modest and avoid self-assertion is one of the characteristics to be seen in these cultural teachings. In a high-context culture, many things are left unsaid, letting the culture explain. As a sharp

contrast, the low-context culture, common in the United States, places an emphasis on the value of the individuals. A low-context culture explains things further because of diverse backgrounds and drastic cultural change from one generation to the next. After having understood these cultural differences, one should not be surprised to find that most

students in Taiwan tend to be reticent as well as self-censoring writers as a result of socialization. For example, in the activity of peer response, a partner may have some reservations in giving feedback on a peer’s writing for the sake of saving face. According to the Politeness Theory proposed by Brown & Levinson (1987), “face” refers to a person’s public self-image. Positive face is the desire for appreciation and approval by others. Examples of face-threatening acts include criticism, insults, and a language that shows a lack of respect for other people. As a contrast, negative face is the desire not to be imposed on by others. Examples of face-threatening acts include inappropriate requests, questions, and interruptions (they are generally taken as intrusive rather than cooperative). Any intrusive speech acts are viewed as encroaching upon the

“territoriality” of the conversational partners in a high-context culture (Murata, 1994, p. 398). When interacting, a writer needs to balance the concern for a peer’s face with the desire to protect her/his own. To avoid self-assertion is one rule of thumb in interpersonal relationship. This face-saving concern led the interaction among the peers to be labeled as about-task or off-task, instead of on-task (de Guerrero & Villamil, 1994).

Sixth, the variance among student participants within the three subgroups (high, intermediate, and low achievers) in the matter of language proficiency, cognitive and affective domain, efficacy expectation, and background knowledge makes it impossible to reach clear-cut and precise conclusions from their responses to different writing activities. For example, Mico, a low achiever in writing performance, is a thoughtful student with strong efficacy expectation after having gone through the two cycles of writing assignments. By contrast, Alison, a high achiever in writing tasks, is impatient with all peer response activities, taking them as a “too time-consuming” learning process.

Sandra, an intermediate writer, expresses certain viewpoints that are quite different from her peers. In short, the findings obtained from data sets are mixed with differing degrees of perceptions and opinions. The results presented, as is so often the case, are only possibilities or tendencies.

The last limitation is related to the translation of the dialogues from peer response sessions and interviews with informants. To get the full and subtle expressions of the

students, all oral activities were conducted in Chinese. The researcher encountered some difficulties in the process of translating the transcriptions from Chinese into English. First, in the Chinese versions, the symbols of conversation analysis used in the dialogues of peer response sessions became dislocated and decreased in English versions due to syntactic and logic differences in these two languages. Second, for some expressions in Chinese, no counterparts could be found in English, for example, “a frog in the well,” “building a cart behind the closed doors,” and “bustle around like a headless fly.” As a result, some similar expressions in English were used to make the data comprehensible to readers. Third, some interjections in Chinese had no equivalent words in English, for example, “ai” for a sigh, “yi” for surprise, “en” to express doubt or make a promise, and therefore were rendered as typical English interjections. For the above-mentioned reasons, the researcher makes no claim that the translations of the interviews and peer dialogues are completely faithful, graceful, and expressive as the counterparts in Chinese.

Definitions of the Terms Used in the Study The terms used in this study were defined as follows:

Activity: Activity is “a collective, systematic formation that has a complex mediation structure” (The Activity System, 2003). In the afore-mentioned EFL writing class, the learning activities included interaction among peers and the teacher by using guidelines and feedback sheets, following the agreed-upon class rules, shouldering one’s share of a task, and playing different roles on various occasions to engage in a process-oriented approach to the writing tasks.

Multiple Interaction Activities: Activities included are self-directed, peer, and teacher feedback. Training students and modeling how to conduct these feedback processes were provided before these activities were implemented. In addition, pre-writing discussion and debriefing were carried out as parts of the classroom activities.

Self-Directed Feedback: With the guidance of a self-directed feedback worksheet, the writer revised his/her first draft to make it clearer and more readable. The purpose of the self-directed feedback activity was to hold student writers accountable as authors for their own written texts and to raise their awareness of where to place their selective attention about the aspects of writing. This activity aimed to help students to cultivate personal autonomy and assume responsibility in the learning of writing to eventually acquire self-efficacy and become autonomous writers.

Peer Feedback: Similar to peer evaluation, peer review, and peer editing, peer feedback was considered to consist of the following activities: pre-writing discussion, reading each other’s texts, providing oral and written feedback through a face-to-face negotiation over the intended and perceived meanings, and seeking for an alternative text. Moreover, the

students assumed the roles of writers, readers, partners, and tutors to recreate their written texts in a cooperative way.

Teacher Feedback: The feedback provided by the teacher in the present study was different from the traditional one. In a traditional teacher feedback activity, a teacher, in accordance with personal experience and belief about an ideal text, gives as many comments and corrections as possible at one time to make the student text complete, cohesive, and coherent. In this study, to avoid the appropriation of student text, the teacher wrote no more than three or four major concerns (Connors & Glenn, 1995; Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005; Straub; 2000) about textual changes. It was necessary to tell the student writers that even a final draft could be revised to increase its clarity, completeness, concreteness, and coherence. The motivation of the teacher not to provide students with all possible comments was out of the respect for the students’ rights as the owners of the texts and as writers to be.

Organization of the Study

This study was to explore the experiences and perceptions of students after the implementation of multiple interaction activities in a large multilevel EFL writing class in a private university in the southern part of Taiwan. Chapter Two presents the related rationales of peer response (the process writing theory, social-historical theory,

collaborative theory, perspectives on interaction from the field of second language acquisition, and cultural-historical activity theory), the pros and cons of peer response, some principles for effective peer response, the debate over the effects of teacher feedback, the concept of writer autonomy, and some previous empirical studies related

to peer response. Chapter Three introduces the qualitative methodology of a case study approach, including participants and setting, instruments, and procedures, data analysis, verification of interpretation, ethical considerations, and subjectivity statement. Chapter Four presents the results and addresses the research questions. Finally, in Chapter Five, major findings of the study are concluded, and pedagogical implications and

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter comprises eight parts. The first section is related to the higher education system in Taiwan. The second section concentrates on the rationale justifications for peer response. The third section focuses on the evaluation of peer response implemented in the ESL/EFL writing classrooms. The fourth section discusses some principles for effective peer response. The fifth section is concerned about teacher feedback and the debate over appropriation. The sixth section concentrates on issues related to writer autonomy, and on how students can benefit from self-directed learning. The seventh section reviews the previous empirical studies of peer response in ESL/EFL environments. Finally, the eighth section summarizes points of this chapter.

Higher Education System in Taiwan

The most significant change in the history of higher education in Taiwan was the revocation of martial law in 1987, giving rise to a rapid expansion of the number of institutions and students in the private sector (Mok, 2002). There were 105 universities and colleges (36 public and 69 private) in 1987 with 429,211 enrolled students in total in higher education (306,424 in the private sector and 122,787 in the public institutions). In March 2008, the Taiwanese system of higher education encompassed 164 degree granting institutions. Among them were 55 public universities and colleges and 109 private ones. There were 1,326,029 students enrolled in the institutions of higher education. The number of students in the public institutions were 412,035; in private schools, 913,994. The number of faculty members in the public schools were 19,215; in the private ones,

31,913 (Department of Statistics, 2008). In other words, the number of schools in the private sector has increased from 69 to 109, and the enrolled students have increased from 306,424 to 913,994 in the past 21 years. The increasing ratio is 1.58 times in the number of institutions, and 2.79 times in the number of students respectively. Based on the numbers of faculty members and of students in the public and private institutions in 2008, the ratio of the number of students to teachers can be calculated to be 21.44 in the public sector, and 28.64 in the private sector.

The current higher education system consists of comprehensive universities/ colleges and professional universities/colleges. The functions of the comprehensive institutions include teaching, research, and service (intramural, social, and communal), with an emphasis on research and teaching. As a contrast, the functions of professional institutions focus on vocational and technological education, research, and the

cooperation with business and manufacturing sectors to develop new skills, procedures, and products. Each of these two lines of education has its own educational goals, curriculum, instruction, and student guidance (Lee, 2004).

According to the 2007 Taiwan Yearbook (Government Information Office, 2007), the Taiwan government spent 19.38% of its national budget on education in the 2006 fiscal year. Total educational expenditures for that year were US$ 21 billion, or about 5.76% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Of the total 5.76% GDP, 1.87% was distributed to higher education. The public institutions received 0.77% (US$ 2.8 billion) and the private sector 1.10% (US$ 4.0 billion) educational subvention (Educational statistical indicators, MOE, 2007). In other words, 109 private universities and colleges shared about US$ 4 billion subsidy from the state according to the results of institutional

and academic assessment done by The Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan, an organization sponsored by the Ministry of Education. The educational subsidy the private sector secured from the state was lower than what the public institutions received per student if the numbers of the private and public institutions were taken into consideration.

In addition, most public universities and colleges have been long established and have accumulated many educational resources while about 40% of the private

universities and colleges were opened after 1987 and have not had much chance to increase their educational resources. The rapid expansion of institutions in higher education dilutes the educational resources and consequently lowers the quality of education, especially in the private sector. To make the matter more complicated, the drastic downturn in the birth rate every year will soon make some schools in higher education unable to sustain or continue operating because of a lack of students. According to the Ministry of Interior Affairs of Taiwan, the number of new babies in 1991 was 308,569, then decreased to 292,724 in 2000, and finally declined to 192,887 in 2006. That is to say, during the past 15 years, the number change is minus 115,682; this change of the birth rate is a negative 37.49% (Chen, 2007). For most private institutions in tertiary education, tuition and miscellaneous fees are the major source of revenue for school operation. Their students are charged higher tuition and fees. For example, the range of tuition and fees in the public sector was from NT$ 41,580 (US$ 1,386) to NT$ 58,980 (US$ 1,966) in 2005. As a contrast, students were charged from NT$ 75,820 (US$ 2527) to NT$ 110,460 (US$ 3,682) in the private schools (Ministry of Education, 2006). In other words, students in the private tertiary education sector have to pay about 1.8

times more than students in the public schools. Generally speaking, students go to private colleges because their grades obtained in the joint entrance examination are not good enough for them to go to the public universities.

The rapid expansion of private institutions in higher education is not only the result of the government’s policy to use private sources to establish more universities and colleges to cultivate highly qualified manpower for economic development, but also the reflection of social needs of common citizens. Most parents in Taiwan perceive higher education as a major path for future career development and personal advancement. Before 1987, high school graduates needed to pass a highly competitive national examination called the Joint University Entrance Examination to be admitted to higher education sectors. With the establishment of more institutions of higher education, students have more choices during a multiple-channel entrance admission process by either completing a recommendation/an exam procedure or applying to the programs and universities they select. Generally, students with outstanding academic performance in schools or winners of competition like International Math Olympics are recommended to enter university without taking the entrance examination.

In response to the impact of the rapid expansion of institutions on higher education provision and the trend of globalization, the Taiwan government revised the University Law in 1994 to give universities and colleges more freedom and flexibility in matters such as university autonomy (personnel management), academic self-determination, authority to enroll students and develop their own curriculum, and more financial autonomy. In other words, the revised University Law “launched an accelerated process of educational liberalization and deregulation” (Yang, 2001, p. 9).

In summary, with too many private universities and colleges established, the dilution of governmental educational resources, the decline in the birth rate, and the downturn of economical growth, the private institutions of higher education in Taiwan will face many challenges soon. They need to make difficult choices among the following situations to survive and develop: to recruit more students with lower academic

performance to maintain school operation, to merge with other schools, to recruit more international students if possible, to get more governmental subsidy (the least feasible solution), to transform their educational objective by increasing some attractive life-long learning programs for adults and retired people, to downsize the school, and/or to

promote their school’s competitiveness and prestige by improving teaching, research, and service quality.

Rationale Justifications for Peer Response

This section consists of five subsections. Each subsection will dwell on one theory that underpins the theoretical framework of peer response. First, the process-writing theory influences the implementation of peer response by emphasizing meaning over form, process over product, and multiple revisions over finished texts in the process of writing. Second, the social-historical theory provides peer response with the concepts of scaffolding and collaboration among peers, as well as the sequence of language

development. Third, the collaborative learning theory argues that knowledge is constructed by learners through active participation in the activities in a learning community in a two-way communication. Fourth, some studies in the field of second language acquisition provide insights on the importance of group work in the acquisition

of second language, especially the ideas of comprehensible input, intake, and output through peer interaction. The last rationale for peer response is the cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT), which can be used to describe the elements of peer response from the perspectives of motivation, goal, and operation as well as the dynamic reciprocal transformation of each element.

Process Writing Theory

The first theoretical foundation of peer response is derived from the process writing theory. In general, the process-oriented writing theory emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the L1 writing setting as a response to traditional product-oriented writing and then was adopted in L2 writing as a pedagogical practice. Process approach writing highlights the importance of the process of writing; students are encouraged to engage in “brainstorming activities, outlining, drafting (focusing on meaning), rewriting (focusing on organization and meaning), and editing (focusing on style and grammar)” (Liu & Hansen, 2002, p. 3). As a contrast, product approach writing emphasizes the importance of form and the finished text by imitating model essays. Certain factors contributed to the rise of the process approach writing in the composition classrooms. First and foremost, process writing rose in the early 1960s along with the New Education Movement (Connors & Glenn, 1992), which was deeply influenced by Jerome Bruner’s ideas on learning, especially the discovery learning theory. For Bruner, learning was a process of discovering meaning, not simply taking in the ready-made knowledge. It was not enough to teach students facts and techniques; instead, education should engage students in the

process of discovering the how and why of something as it was. He illustrated this point clearly in Toward a Theory of Instruction by saying that

To instruct someone…is not a matter of getting him to commit results to mind. Rather, it is to teach him to participate in the process that makes possible the establishment of knowledge. We teach a subject not to produce little living libraries on that subject, but rather to get a student to think mathematically for himself, to consider matters as an historian does, to take part in the process of knowledge getting. Knowledge is a process, not a product. (1966, p. 72) Active participation in a collaborative process with personal past/current knowledge and experience to construct knowledge constitutes what is essential for learning. In a process-oriented writing task, peer response, viewed as one of the important instructional methods, supports the writing activity by students’ engagement in constructing texts through

negotiation of meanings, multiple feedback from multiple audiences, and multiple revision and editing.

Next, some researchers dedicated themselves to advocating the process approach to writing in the early 1970s. Janet Emig (1971) argued that in the writing classroom, reflexive (personal) writing, initiated by students, should be used more often than extensive (formal) writing, sponsored by the teacher. Reflexive writing concerns the writers’ feelings and experiences, and prompts more planning, drafting, and revising. In contrast, extensive writing focuses on information to be conveyed to a reader, usually the teacher as the target audience. The influence of Emig’s study lies in its conception of composition as a process and its suggestion that the composing process should be taught and studied. Peter Elbow is another important figure who supports the practice of process

writing. In Writing without Teacher (1973), Elbow proposed an alternative to the

traditional writing approach. Instead of generating thoughts first, mapping an outline next, and starting writing finally as dictated in the traditional approach to composing an essay, he suggested that writing (free writing) in the early draft should be a process to let

thinking flow with little concern about grammatical accuracy, diction, sentence structure, or a thesis since too much attention paid to mechanical matters can stifle thought. Only in the late draft should a writer pay attention to revising and editing diction, grammatical items, sentence structure, and rhetoric. For Elbow, writing is a process of cultivating personal voice. To promote the development of personal voice, writers are advised to work with peers instead of with teachers. The teacher-student relationship is not on an equal status (teachers as evaluators of students’ works), while peer-peer relationship is equal with regard to the roles they play in the peer interaction. Writers can be students as well as teachers and readers as well as reviewers. Even though some researchers criticize his idea of writing without a prior plan since this practice may miss some important points that logically should have been considered in a well-constructed essay (Coomber, 1975), and his idea of free writing as having the tendency to reject skills instruction and the naïve expectation that frequent practice makes good writers (Fox & Suhor, 1986), Elbow’s conception of writing exerts a great influence on the later-on development of peer response in the aspects of multiple drafts and multiple revisions based on multiple feedback from peers, awareness of the presence of audience, and the necessity of an objective attitude in peer exchange of opinions.

Finally, Rohman and Wlecke developed and modified prewriting as a theory of invention and teaching at Michigan State University in the early 1960s (Connors & Glenn,

1992). They argued that prewriting, the initial and important stage of writing, is the stage of discovery in the writing process. Writing should put more weight on invention and the composing process than on creating a finished essay. For Rohman, writing is a process that “shows continuous change in time like growth in organic nature” and “good thinking can produce good writing” and therefore “students must learn the structure of thinking that leads to writing” (1965, pp. 106-107). Pre-writing is one of the elements in the Stage-Model theory—prewriting, writing, and rewriting—that constitutes one strand of the process writing theory. Peer response substantiates the process-writing theory by focusing on brainstorming and multiple revisions.

Social-Historical Theory

The social-historical theory provides a second theoretical foundation for the

implementation of peer response in the ESL/EFL writing class. The major contribution of the social-cultural theory to substantiate the rationale of peer response comes from

Vygotsky’s concept of zone of proximal development (ZPD) and concept of language development. In Mind in Society (1978), Vygotsky defined the concept of ZPD by saying that

it is the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers. (p. 86)

There are two salient points in this concept: guidance and collaboration. In other words, Vygotsky points out the essence of the social interaction between teacher and student as

well as student and student in a school setting. In both types of interactions, teacher and student can serve in the role of guide and collaborator for other students in the learning community.

In the teacher-student interaction, the teacher serves as guide, facilitator, and coach, or sometimes as co-author with students. Generally speaking, the role of the teacher is to provide scaffolding, and not to directly instruct. The student has to construct his/her own meaning and make his/her own textual decisions.

In the ESL/EFL writing class, what a teacher provides to students should not be a kind of “banking system” (Freire’s term, 1998)—the teacher as the dispenser of

knowledge and the students as passive recipients. Instead, the students should actively participate in the process of learning to construct knowledge of writing from their past experiences. The principle for this kind of interaction is that a teacher “give[s] more help when the learners get into difficulty, but offer less help as they gain in proficiency” (Wood & Wood, 1996, p. 7).

As for the peer/peer interaction, a student can serve as a tutor or a collaborator. This type of interaction is especially helpful in a large multilevel class with heterogeneous-ability students. In some countries, teaching students in a small class is only a dream, impossible to make true. The school's financial budget cannot afford to have more teachers to fill teaching positions. Under this circumstance, requiring a writing teacher to give students detailed feedback is to demand an almost Herculean task. Even if the effort and energy put into the job of feedback are worthwhile, no teacher can handle the amount of paper correction of three classes with fifty students, respectively, each week.

The benefits of peer tutoring and peer collaboration, according to Forman and Cazden (1986), are that, among the students who interact at a cooperative level, a great deal of mutual support, encouragement, correction, and guidance is exchanged. In addition, collaborative problem solving seems to offer some of the same experiences for students that peer tutoring provides: (1) the need to give verbal instructions to peers, (2) the impetus for self-reflection encouraged by a visible audience, and (3) the need to respond to peer questions and challenges (p. 183). But the most important value of peer interaction is that the student takes an active role in schools where the teacher-student interactions are limited and rigid because the roles are irreversible. With their peers, students can reverse interactional roles with the same intellectual content, giving

directions as well as following them, and asking questions as well as answering them (p. 184).

The concept of language development is another contribution of Vygotsky to support the rationale of peer response. The sequence of language development progresses from social speech through egocentric speech to inner speech and finally to written speech (1986). The gist of social speech states that language development is gradually obtained through the communication between learners and more capable peers or adults. The function of social speech is to convey intended meanings to the other party. After mastery of social speech, a learner will be able to develop egocentric speech, or self-talk. Self-talk is the transitory stage for a learner to transform (internalize) social speech into inner speech. In short, “[i]nner speech is speech for oneself; external speech is speech for others” (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 225). For most ESL/EFL learners, social interaction is one way to acquire social speech with interlanguage. Social interaction embodies the verve of

peer response activities—negotiating meanings by clarifying the problem, asking and answering questions, confirming, and repairing. It is through the effort of operation and repetition that peers can “create and maintain a shared perspective of the task (i.e., intersubjectivity) and to construct scaffolded help, which enables them to complete their tasks” (DiCamilla & Anton, 1997, p. 609).

In Thought and Language (1986), Vygotsky acutely points out the several

differences between speech and writing. First of all, writing is different from speech in both structure and function. “It is speech in thought and image only, lacking the musical, expressive, intonational qualities of oral speech. In learning to write, the child must disengage himself from the sensory aspect of speech and replace words by images of words” (p.181). It is the abstract quality that prevents learners from mastering the sign system easily. Next, in writing, unlike in speech, there is no actual addressee presented. Thirdly, speech provides interlocutors with motivation for conversation. “In conversation, every sentence is prompted by a motive. Desire or need leads to request, question to answer, bewilderment to explanation” (Vygotsky, 1986, p.181), whereas writing lacks immediate needs and is more abstract. Fourthly, writing is a task that requires a conscious effort of writers to use higher cognitive skills (analysis, synthesis, and evaluation) to transform thought into words (visual speech). Finally, written speech, with no help of body language, intonation, and gesture as in oral speech, must fully present the content of writing in order to be intelligible to readers. The conclusions Vygotsky draws from this comparison are (1) that oral speech is “spontaneous, involuntary, and nonconscious” whereas written speech is “abstract, voluntary, and conscious,” and (2) that instruction in writing starts before the readiness of writers. “It must build on barely emerging, immature