411?

All rights reservedPlasma Selenium Levels and Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma among Men

with Chronic Hepatitis Virus Infection

Ming-Whei Y u ,u Ing-Sheng Horng,2 Kuang-Hung Hsu,3 Yi-Ching Chiang,2 Yun-Fan Uaw,4 and Chien-Jen Chen2

Both experimental and epidemiologic studies have linked a low dietary intake of selenium with an increased risk of cancer. The authors examined the association between plasma selenium levels and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) among chronic carriers of hepatitis B and/or C virus in a cohort of 7,342 men in Taiwan who were recruited by personal interview and blood draw during 1988-1992. After these men were followed up for an average of 5.3 years, selenium levels in the stored plasma were measured by using hydride atomic absorption spectrometry for 69 incident HCC cases who were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and/or antibodies against hepatitis C virus (mostly HBsAg positive) and 139 matched, healthy controls who were HBsAg positive. Mean selenium levels were significantly lower in the HCC cases than in the HBsAg-positive controls (p = 0.01). Adjusted odds ratios of HCC for subjects in increasing quintiles of plasma selenium were 1.00, 0.52, 0.32, 0.19, and 0.62, respectively. The inverse association between plasma selenium levels and HCC was most striking among cigarette smokers and among subjects with low plasma levels of retinol or various carotenoids. There was no clear evidence for an interaction between selenium and a-tocopherol in relation to HCC risk. Am J Epidemiol 1999; 150:367-74.

carcinoma; carcinoma, hepatocellular; carotenoids; hepatitis B; hepatitis C; selenium; smoking; vitamin A

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a highly malig-nant neoplasm with an extremely poor prognosis. Although chronic hepatitis B virus infection is the major cause of at least 80 percent of HCC throughout the world, only a minority of the carriers of this infec-tion are expected to develop HCC during their life-times (1, 2). In addition to chronic infection with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, aflatoxin exposure, alcohol drinking, and cigarette smoking have been reviewed extensively for their associations with HCC (2-11). However, very little attention has been paid to the role of dietary factors besides aflatoxins in human hepatocarcinogenesis (7, 10, 11).

Selenium is a component of the enzyme glutathione peroxidase, which plays an important role in the

Received for publication April 30,1998, and accepted for publica-tion January 21, 1999.

Abbreviations: anti-HCV, antibodies against hepatitis C virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. 1 School of Public Health, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

2 Graduate Institute of Epidemiology, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

3 Laboratory for Environmental Toxicology and Epidemiology, Department of Health Care Management, Chang-Gung University, Taipei, Taiwan.

*Uver Research Unit, Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang-Gung University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Reprint requests to Dr. Ming-Whei Yu, Graduate Institute of Epidemiology, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, No. 1 Jen-Ai Road Section 1, Taipei 100, Taiwan.

body's antioxidant defense against the deleterious effects of free radicals (12, 13). There is convincing evidence that free-radical-mediated DNA damage is a significant factor in the etiology of cancer (13). The majority of animal studies related to selenium and can-cer have reported a protective effect of selenium, including inhibition of carcinogen-induced hepatocar-cinogenesis (14-20). Geographic correlation studies of humans have demonstrated that cancer mortality rates are higher in regions with low levels of selenium in forage crops and in serum than in regions with high levels of selenium (21, 22). Prospective studies carried out among populations with a low or moderate sele-nium intake have found an inverse association between selenium levels in the blood or toenails and cancer at all sites combined and at specific sites, especially the lung and stomach (23-26). Several authors have sug-gested that the increased cancer risk in relation to low selenium status is more pronounced in men than in women (24-26). However, prospective studies of sele-nium and cancer in populations with a high selesele-nium intake have yielded inconsistent results (27-31). None of these studies has focused specifically on HCC.

Taiwan is a hyperendemic area of hepatitis B virus infection, with a chronic carrier rate of as high as 15-20 percent (1-3). The prevalence of antibodies against hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) in the general population of Taiwan is less than 2 percent (2, 3). 367

Approximately 80 percent of the HCC that occurs in this high-risk area is attributable to chronic infection with hepatitis B and/or C virus (2, 3). Chronic infec-tion by viruses results in chronic phagocytic activity, which is one of the major endogenous sources con-tributing to most of the free radicals produced by cells (13). We investigated the associations of blood levels of retinol and various carotenoids with HCC by using a nested case-control study design, and the results sug-gest that high levels of these micronutnents may be associated with a decreased risk of HCC in relation to chronic hepatitis B virus infection, cigarette smoking, and/or alcohol drinking (10, 11). The present study was based on a long-term prospective study and was undertaken to assess the importance of selenium status in hepatocarcinogenesis among men with chronic hepatitis B and/or C virus infections. Since the func-tions of selenium and other antioxidant micronutrients, such as retinol, various carotenoids, and a-tocopherol, overlap (13), it is conceivable that the relation between selenium status and HCC is influenced by the status of other antioxidants. Our study also addressed this pos-sible interactive effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Study subjects

The characteristics and method of cancer follow-up for the complete cohort or part of the cohort in this study have been described previously (4, 5, 9, 11, 32). Between August 1988 and June 1992, a cohort of men aged 30-65 years, 4,841 asymptomatic hepatitis B sur-face antigen (HBsAg) carriers and 2,501 noncarriers, was recruited from the Government Employee Central Clinics and the Liver Unit of Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan. At recruitment, each study participant was interviewed in person to obtain infor-mation on demographic characteristics, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, frequency of consumption of various food items, and personal and family histo-ries of major diseases. Fasting blood samples were col-lected from all study participants. Aliquots of plasma, serum, and buffy coat separated from blood samples were stored at -70°C until subsequent analyses. This study was approved by the Department of Health, Executive Yuan.

All HBsAg carriers were scheduled to undergo both an a-fetoprotein measurement and an ultrasonography examination every 6—12 months. Abdominal ultra-sonography was performed by experienced gastroen-terologists. Any subject who had an ultrasonographic image that was compatible with HCC and/or an ele-vated a-fetoprotein level (>20 ng/ml) was referred for further confirmatory diagnosis. After each follow-up

examination, approximately 70 percent of the surviv-ing HBsAg carriers continued to return for examina-tion. HBsAg noncarriers and HBsAg carriers who did not participate in the follow-up examinations were fol-lowed up by interviewing them by telephone and by linking data with the computer files of national cancer and death registry systems. When a case of HCC was identified, permission was sought from the hospital where the subject was diagnosed with cancer to obtain the medical charts and pathology reports. A final diag-nosis of HCC was based on 1) positive findings from pathologic or cytologic examinations and/or 2) an ele-vated a-fetoprotein level (>400 ng/ml) combined with at least one positive image from angiography, sonog-raphy, and/or computed tomography.

During an average of 5.3 years of follow-up, 73 inci-dent cases of HCC were ascertained. Fifty-three were identified by means of periodic follow-up examina-tions and 20 through secondary sources of information including death records and reports from the national cancer registry system. Excluded from analysis were 4 cases with insufficient plasma samples for selenium assay, which left a total of 69 HCC cases in this study. Almost all HCC cases were HBsAg carriers; the 2 HBsAg-negative cases were positive for anti-HCV. Of the 67 HBsAg-positive HCC cases, 7 had insufficient serum samples for anti-HCV assay, and 5 were also anti-HCV positive.

HBsAg-positive controls were chosen at random from cohort members who remained unaffected with HCC throughout the follow-up period. They were matched with HCC cases on the basis of age (±5 years), recruitment clinic, and date of questionnaire interview and blood collection (within 3 months). HBsAg-negative controls were also chosen from the same cohort according to this matching process to evaluate the effect of chronic hepatitis B virus infec-tion on plasma selenium levels.

Laboratory analyses

Serum HBsAg was tested by radioimmunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Illinois). A sec-ond-generation enzyme immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories) was used to detect anti-HCV. Plasma lev-els of retinol, a-tocopherol, and various carotenoids were determined by high-performance liquid chro-matography (33). The between-run coefficients of vari-ation were <5.0 percent for retinol and a-tocopherol, 5-6 percent for a-carotene and P-carotene, and 9-10 percent for lycopene.

Selenium levels were measured in plasma samples by flow injection hydride atomic absorption spectrom-etry using a modification of the method described by Negretti de Bratter et al. (34). A Perkin-Elmer 3100

atomic absorption spectrometer equipped with a Perkin-Elmer FIAS-400 System was used (Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Norwalk, Connecticut). The cali-bration curve was built up by using standard reference material of human serum (Nyegaard, Oslo, Norway). For acid digestion, a 0.2 ml plasma aliquot or a 0.2 ml aliquot of the working standard solution was treated with 1 ml of a mixture of concentrated acid (HNO3:HC1O4 = 4:1). The sample was digested on an electric oven for 2 hours at 160°C. When it cooled, the digested sample was adjusted to a final volume of 3 ml by using 7N HC1 and antifoam reagent and was reduced from Se (VI) to Se (TV). After hydride was generated by using a sodium borohydride method, the selenium content was determined.

The results from the analysis of standard reference materials matched the certified values. Spiking tests showed that the recovery was 94-109 percent for the method of selenium assay used. The method's coeffi-cient of variation between days was 10 percent, and the detection limit was 5.0 (ig/liter. Duplicate speci-mens were assayed for each study subject, and the average of the two was used to indicate the selenium levels. Each analytical batch contained plasma sam-ples from HCC patients and matched controls (includ-ing HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative controls). No systematic changes in the selenium levels of the reference sera were observed throughout the period of laboratory analysis. Laboratory personnel were kept blind to disease status.

Statistical methods

The chi-square test was used to examine differences in the distributions of categorical variables between groups. Statistical adjustment of the selenium value in plasma was performed by using the residual method (35). The significance of differences in the adjusted selenium values by categories was assessed by using the t test or the F test, as appropriate. Selenium values were categorized as quintiles or tertiles on the basis of the distribution among all controls. Conditional logistic regression models were used to derive the matched crude and multivariate-adjusted odds ratios associated with HCC. In the stratified data analyses of the interac-tions of selenium with cigarette smoking and other micronutrients, unconditional logistic regression analy-sis was performed to estimate the odds ratios. Tests for trend in the odds ratios across tertiles of selenium lev-els were computed on the basis of likelihood ratio tests, with scores of 1-3 assigned to increasing tertiles of plasma selenium. We also used likelihood ratio tests to determine the statistical significance of the interactions between selenium and other factors with respect to HCC risk. These tests compared a "main effects, no

interaction" model with a fully parameterized model containing all possible interaction terms for the vari-ables of interest. All p values were calculated from two-tailed tests of statistical significance.

RESULTS

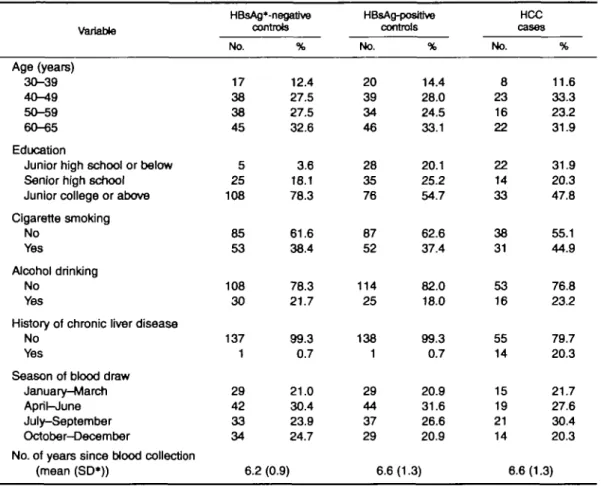

The distributions of the groups studied, by selected baseline characteristics, are presented in table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in the distributions of age, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, season of blood draw, and number of years since blood collection. Seventy-eight percent of the HBsAg-negative controls had an educational level of junior college or above, in contrast to approximately 50 percent of the subjects in the other two groups. The proportion of men who had a history of chronic liver disease was significantly higher among HCC cases than among the two control groups.

Among controls, there were no statistically signifi-cant Pearson's correlation coefficients for plasma sele-nium with plasma retinol (r = -0.04), oc-tocopherol (r = -0.02), a-carotene (r = -0.03), P-carotene (r = -0.04), and lycopene (r = -0.03). Furthermore, no statistically significant association with plasma selenium was found for age, educational level, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, season of blood draw, or number of years since blood collection. However, selenium levels declined slightly with age and were lower in smokers and drinkers. Because age, smoking, and alcohol abuse were associated with low selenium status in previous reports (23, 31, 36-38), selenium values adjusted for these three factors were used when we compared the mean or median levels of selenium between groups. The adjusted mean and median values of plasma sele-nium for the groups studied are shown in table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in plasma selenium levels between positive and HBsAg-negative controls. HCC cases had significantly lower mean plasma levels of selenium than did HBsAg-positive controls (p = 0.01). When HCC cases were categorized by the year of follow-up in which they were diagnosed, there was no trend toward lower plasma levels in cases occurring early.

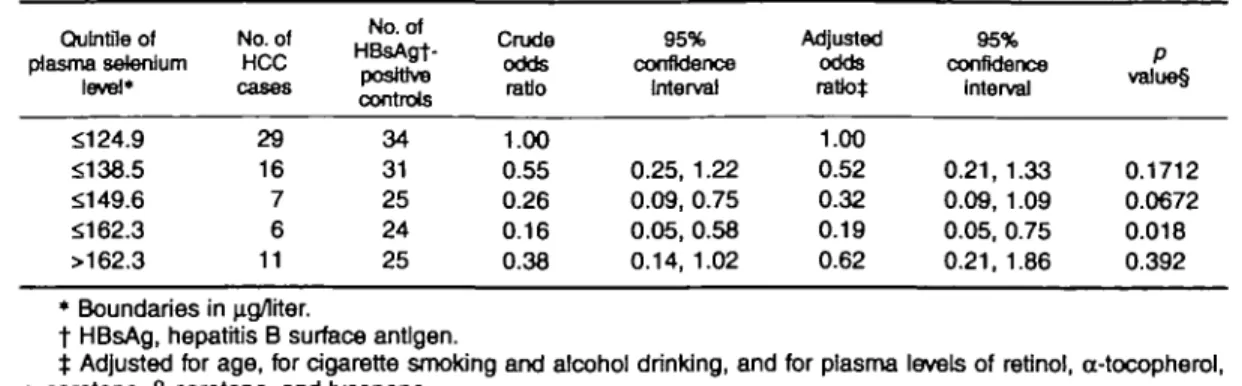

The odds ratios associated with HCC, by quintiles of plasma selenium among men with chronic hepatitis virus infection, are shown in table 3. All HCC cases but only HBsAg-positive controls were included in the analyses. In the multivariate analysis of the association between plasma selenium levels and HCC, we adjusted for age, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and plasma levels of other micronutrients. The multivari-ate-adjusted odds ratios of HCC for increasing quin-tiles of plasma selenium were 1.00, 0.52, 0.32, 0.19, and 0.62, respectively. A similar pattern was observed

TABLE 1. Baseline characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases and matched healthy controls, Taipei, Taiwan, 1988-1992

Variable HBsAg'-negative controls HBsAg-posffive controls HCC cases Age (years) 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-65 Education

Junior high school or below Senior high school Junior college or above Cigarette smoking No Yes Alcohol drinking No Yes

History of chronic liver disease No

Yes

Season of blood draw January-March April-June July-September October-December

No. of years since blood collection (mean (SD*)) No. 17 38 38 45 5 25 108 85 53 108 30 137 1 29 42 33 34 6.2 % 12.4 27.5 27.5 32.6 3.6 18.1 78.3 61.6 38.4 78.3 21.7 99.3 0.7 21.0 30.4 23.9 24.7 (0.9) No. 20 39 34 46 28 35 76 87 52 114 25 138 1 29 44 37 29 6.6 % 14.4 28.0 24.5 33.1 20.1 25.2 54.7 62.6 37.4 82.0 18.0 99.3 0.7 20.9 31.6 26.6 20.9 (1.3) No. 8 23 16 22 22 14 33 38 31 53 16 55 14 15 19 21 14 6.6 % 11.6 33.3 23.2 31.9 31.9 20.3 47.8 55.1 44.9 76.8 23.2 79.7 20.3 21.7 27.6 30.4 20.3 (1.3) 1 HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; SD, standard deviation.

after excluding subjects with a history of chronic liver disease; the odds ratios of HCC for increasing quintiles of plasma selenium were 1.00, 0.74, 0.60, 0.24, and 0.41, respectively (data not shown).

As shown in table 4, HCC cases were subdivided into two groups according to the median of the time

between blood draw and cancer diagnosis. The odds ratio, by quintile of plasma selenium level, was esti-mated for each of the two groups of cases and matched controls. Within 2.8 years of blood draw, there was no significant association between plasma selenium and HCC, but a significant inverse association was found TABLE 2. Plasma selenium levels In hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-negative controls,

HBsAg-posrtlve controls, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases at recruitment,! Taipei, Taiwan, 1988-1992

Group HBsAg-negative controls HBsAg-posttive controls HCC cases

No. of years of follow-up§ <1.4 1.4-2.7 2.8-4.0 >4.0 No. of subjects 138 139 69 18 16 17 18 Median 144.7 143.3 129.9 130.4 130.2 128.3 136.5

Plasma selenium level Mean(SD$) 150.2(35.2) 144.9 (37.6) 131.6* (30.9) 133.4(31.4) 124.6 (26.0) 127.5(27.5) 139.9 (37.3) (up/iter) Range 86.5-396.5 75.6-368.3 53.8-225.2 80.2-205.4 65.7-167.4 53.8-162.8 68.3-225.2 * p = 0.01 compared with HBsAg-posWve controls.

t Selenium levels were adjusted for age and for cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking. t SD, standard deviation.

TABLE 3. Odds ratios of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) associated with plasma selenium levels among men with chronic hepatitis virus infection, Taipei, Taiwan, 1988-1992

Qu In tile of plasma selenium level* No. of HCC No. of HBsAgt-poslttve controls Crude odds ratio 95% confidence Interval Adjusted odds ratio* 95% confidence Interval P value§ $124.9 $138.5 $149.6 $162.3 >162.3 29 16 7 6 11 34 31 25 24 25 1.00 0.55 0.26 0.16 0.38 0.25, 1.22 0.09, 0.75 0.05, 0.58 0.14, 1.02 1.00 0.52 0.32 0.19 0.62 0.21, 1.33 0.09, 1.09 0.05, 0.75 0.21, 1.86 0.1712 0.0672 0.018 0.392 * Boundaries in u.g/lrter.

t HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

t Adjusted for age, for cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking, and for plasma levels of retjnol, cc-tocopherol,

a-carotene, fj-carotene, and lycopene.

§ Tests for significance of adjusted odds ratios.

TABLE 4. Odds ratios of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with plasma selenium levels, by time between blood draw and diagnosis, among men with chronic hepatitis virus Infection, Taipei, Taiwan, 1988-1992

QuIntJIe of plasma selenium

level*

Time between Hood draw and diagnosis (years)

< 2 8 22.8 Odds ratio 95% confidence Interval Odds ratio 95% confidence Interval $124.9 $138.5 $149.6 $162.3 >162.3 1.00 0.72 0.56 0.70 0.23 0.25,2.11 0.15,2.02 0.16, 3.14 0.04, 1.18 1.00 0.39 0.04 0.02 0.29 0.12,1.27 0.003, 0.64 0.001, 0.25 0.06, 1.35 • Boundaries in jig/lrter.

when statistical evaluation was restricted to the 35 cases diagnosed more than 2.8 years after the blood samples were collected.

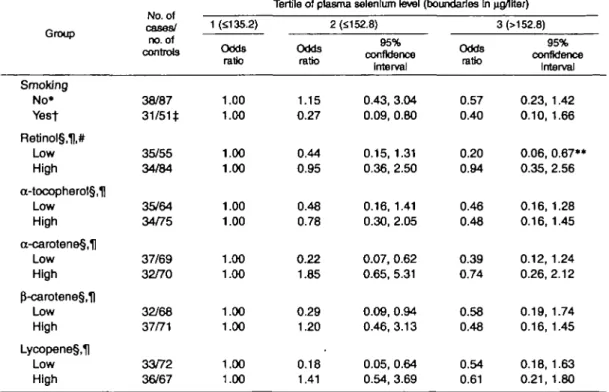

The multivariate-adjusted odds ratios of HCC associ-ated with plasma selenium among men with chronic hepatitis virus infection, by category of cigarette smok-ing and plasma levels of retinol, a-tocopherol, and var-ious carotenoids, are presented in table 5. A statistically significant inverse association was found between sele-nium and HCC among cigarette smokers and among subjects with low plasma levels of retinol or various carotenoids. A U-shaped relation between selenium and HCC was observed among smokers and among sub-jects with low plasma carotenoids. However, the HCC risk decreased monotonically with increasing levels of selenium in the low-retinol group (test for trend, p = 0.006). In any of the other groups, none of the odds ratios for tertiles of plasma selenium levels was tically significantly different from unity. While a statis-tically significant modification of the selenium effect by retinol levels was found (test for interaction, p < 0.005), there were no statistically significant interac-tions between selenium and other factors.

DISCUSSION

Experimental studies indicate that selenium has anti-carcinogenic properties. Mechanisms that may be involved in the protective effect of selenium include a reduction in the mutagenicity of carcinogens, inhibi-tion of cell proliferainhibi-tion, and protecinhibi-tion against oxida-tive damage via selenium-dependent glutathione per-oxidase (12-14, 39-42). Selenium is also known to affect immune function (43). In our study, we used a prospectively collected marker of selenium exposure and observed a statistically significant inverse associa-tion between plasma selenium levels and HCC among men with chronic hepatitis virus infection (mostly chronic hepatitis B virus carriers). This association cannot be explained on the basis of measured con-founders.

A fraction of HCC patients may develop cancer after the onset of various chronic liver diseases (2, 32). Lower plasma selenium levels in HCC cases may result from hepatic dysfunction, which may influence dietary intake, metabolism, and/or distribution of selenium; thus, lower levels of selenium among cases compared with controls may be a consequence rather than a cause of the disease. In support of this hypothesis is the obser-vation that blood selenium levels have been shown to decrease in patients who have various clinical, chronic liver diseases largely caused by alcohol abuse, in which case selenium deficiency has been attributed to inade-quate selenium intake (36-38). However, most of the HCC patients in this study were asymptomatic chronic carriers of hepatitis B and/or C virus who had no his-tory of chronic liver disease at recruitment. No statisti-cally significant difference in the plasma selenium lev-els was observed between HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative controls. Exclusion of study subjects who had a history of chronic liver disease produced no substantial change in the pattern of the inverse relation between selenium and HCC.

TABLE 5. Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) associated with plasma selenium levels, by category of cigarette smoking and plasma levels of other micronutrlents, among men with chronic hepatitis virus Infection, Taipei, Taiwan, 1988-1992

Group Smoking No* Yest Retinol§,H,# Low High a-tocopherol§,| Low High a-carotene§,H Low High p"-carotene§,1) Low High Lycopene§,H Low High cases/ no. of controls 38/87 31/51* 35/55 34/84 35/64 34/75 37/69 32/70 32/68 37/71 33/72 36/67 1 (5135.2) Odds ratio 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00

Tertile of plasma selenium level

Odds ratio 1.15 0.27 0.44 0.95 0.48 0.78 0.22 1.85 0.29 1.20 0.18 1.41 2 (£152.8) 95% confidence Interval 0.43, 3.04 0.09, 0.80 0.15, 1.31 0.36, 2.50 0.16, 1.41 0.30, 2.05 0.07, 0.62 0.65, 5.31 0.09, 0.94 0.46, 3.13 0.05, 0.64 0.54, 3.69 (boundaries In waiter) 3(>152.8) Odds ratio 0.57 0.40 0.20 0.94 0.46 0.48 0.39 0.74 0.58 0.48 0.54 0.61 95% confidence Interval 0.23, 1.42 0.10, 1.66 0.06, 0.67** 0.35, 2.56 0.16, 1.28 0.16,1.45 0.12, 1.24 0.26,2.12 0.19, 1.74 0.16, 1.45 0.18, 1.63 0.21, 1.80 * The model included terms for age and alcohol drinking.

t The model included terms for age, alcohol drinking, and pack-years of smoking.

t For one hepatitis B surface antigen-positive control, no data were available on the number of cigarettes

smoked per day.

§ The high and low levels of carotenoid were categorized according to the median value for all controls. For retinol and a-tocopherol, the cutoff values for low and high were based on the median values for HCC cases, because a small number of the cancer patients had plasma levels of these nutrients that were high-er than the median for controls.

H The model included terms for age, alcohol drinking, and cigarette smoking. # Test for interaction between selenium and retinol was significant.

• • Test for trend was significant.

It also seems unlikely that the inverse association between plasma selenium and HCC can be explained by bias due to the effect of preclinical cancer, as we did not observe a significant association of selenium levels with time to diagnosis among HCC cases. In addition, the inverse association between selenium and HCC became stronger after we excluded the case-control matched sets in which the cases were diag-nosed within 2.8 years of blood collection. However, 2.8 years of follow-up may be a relatively short period in which to assess the effect of preclinical can-cer on plasma selenium levels. Analysis of the effect of preclinical cancer was based on the cutoff value of 2.8 years, the median of the time between blood draw and cancer diagnosis among cases, because of the limited follow-up period (only 5.3 years on average) and the small number of cases. A longer follow-up period will be needed to address this issue more definitively.

Although the results from several prospective stud-ies agree with the hypothesis that a low selenium intake raises the risk of cancer, evidence of a dose-response relation between selenium levels in blood or toenails and cancer has been inconsistent (23-29). The discrepancies among these studies may result from the differences in sample sizes, the control of possible confounders, the ranges of selenium levels, the cancer sites studied, and/or the distributions of other nutri-tional factors or of exposures to environmental car-cinogens between study populations. Selenium is an essential trace element, but it is toxic at high doses (13). In the present investigation, the median level of plasma selenium in controls was approximately 140 (a.g/liter, which suggests that dietary selenium intake is not low in this study population. However, we observed an approximately sevenfold variation in plasma selenium levels among study subjects. Our data indicated no linear trend across quintiles of

sele-nium levels for the risk of developing HCC. The low-est risk for HCC was found among subjects in the middle quintiles of plasma selenium. Because of the small number of HCC cases in this study, future stud-ies should clarify whether the U-shaped relation between selenium and HCC is real or whether it resulted from sampling variation or chance.

Cigarette smoking has been associated with a moder-ately excess risk of HCC in populations with a high or low incidence of this disease (3, 6-11). However, the biologic mechanism by which cigarette smoking acts in the pathogenesis of HCC has not yet been evaluated comprehensively (8-11, 32). Tobacco smoke contains a variety of carcinogens with initiator and/or promoter properties (44). It also induces oxidative stress, which is important in the pathogenesis of a wide range of degenerative diseases, including cancer and coronary heart disease (13). In this study, we observed that the inverse association with selenium levels occurred largely among cigarette smokers, but the limited sam-ple size made it difficult to demonstrate a statistically significant interactive effect of selenium and smoking on the development of HCC. As smoking was associ-ated with low selenium status (23, 31), the inverse asso-ciation between selenium and HCC among cigarette smokers might therefore have been confounded by the intensity of exposure to cigarette smoke. However, the significant inverse association among cigarette smok-ers psmok-ersisted even after close control of the intensity of smoking by using pack-years. There was no such asso-ciation among nonsmokers.

There are limited data showing the effect of sele-nium on cancer risk among persons whose smoking habits differ. In probably the only prospective study carried out to assess the potential interaction of sele-nium with smoking in relation to lung cancer, the inverse association with selenium tended to be more prominent among heavy smokers than among light smokers and ex-smokers; however, no significant association between selenium and lung cancer risk was observed for any subgroup (23). Results from previous prospective studies of selenium and cancer generally have been consistent with an inverse association that is more pronounced in men than in women (24-26). Since the prevalence of cigarette smoking is much higher among men than women, and a large proportion of cancers in men are smoking related, it is reasonable to speculate that the gender-specific effect of selenium observed in earlier studies might at least partly reflect the difference in smoking history between the sexes.

With regard to the risk of cancer at all sites com-bined and of lung cancer, it has been suggested that an interaction exists between the effects of selenium and other antioxidant micronutrients, including vitamins

A, C, and E and P-carotene (23, 25, 27). Our previous nested case-control studies have demonstrated that low blood levels of retinol and various carotenoids are associated with an increased susceptibility to HCC (10, 11). In the present study, the inverse association between selenium and HCC was particularly notable for subjects who had low plasma levels of retinol or various carotenoids. We observed a significant modifi-cation of the selenium effect by retinol level. Evidence also suggested an interaction between selenium and various carotenoids, although tests for such interac-tions were not statistically significant. However, no clear evidence was found for an interaction of a-tocopherol and selenium with HCC risk. A chemopre-vention trial conducted in a region of China with extremely high rates of esophageal and stomach cancer reported a 13 percent reduction in cancer mortality as a result of supplementation with a combination of vi-tamin E, p-carotene, and selenium (45). The efficacy of combining selenium with other nutrients to prevent HCC in chronic carriers of hepatitis B and/or C virus merits further study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC 85-233l-B-002-264 and NSC 87-2314-B-002-291) and the National Health Research Institutes, Department of Health, Executive Yuan (DOH86-HR-627 and DOH87-(DOH86-HR-627) of the Republic of China.

REFERENCES

1. Beasley RP. Hepatitis B virus: the major etiology of hepato-cellular carcinoma. Cancer 1988;61:1942-56.

2. Yu MW, Chen CJ. Hepatitis B and C viruses in the develop-ment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol

1994;17:71-91.

3. Yu MW, You SL, Chang AS, et al. Association between hepati-tis C virus antibodies and hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer Res 1991;51:5621-5.

4. Chen CJ, Yu MW, Liaw YF, et al. Chronic hepatitis B carriers with null genotypes of glutathione S-transferase Ml and Tl polymorphisms who are exposed to aflatoxin are at increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Hum Genet 1996;59: 128-34.

5. Yu MW, Lien JP, Chiu YH, et al. Effect of aflatoxin metabo-lism and DNA adduct formation on hepatocellular carcinoma among chronic hepatitis B carriers in Taiwan. J Hepatol 1997; 27:320-30.

6. Yu MC, Tong MJ, Govindarajan S, et al. Nonviral risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in a low-risk population, the non-Asians of Los Angeles County, California. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991;83:1820-6.

7. Chen CJ, Yu MW, Wang CJ, et al. Multiple risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study of 13,737 male adults in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1993;8(suppl):s83-7.

8. Yu MW, Chen CJ, Luo JC, et al. Correlations of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and cigarette smoking with elevated expression of neu oncoprotein in the development of hepato-cellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 1994;54:5106-10.

9. Yu MW, Gladek-Yarborough A, Chiamprasert S, et al. Cytochrome P450 2E1 and glutathione S-transferase M1 poly-morphisms and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1266-73.

10. Yu MW, Hsieh HH, Pan WH, et al. Vegetable consumption, serum retinol level, and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 1995;55:1301-5.

11. Yu MW, Chiu YH, Chiang YC, et al. Plasma carotenoids, glu-tathione S-transferase Ml and Tl genetic polymorphisms, and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: independent and interactive effects. Am J Epidemiol 1999; 149:621-9.

12. Rotruck JT, Pope AL, Ganther HE, et al. Selenium: biochemi-cal role as a component of glutathione peroxidase. Science 1973;179:588-90.

13. Frei B, ed. Natural antioxidants in human health and disease. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1994.

14. Leboeuf RA, Laishes BA, Hoekstra WG. Effects of dietary selenium concentration on the development of enzyme-altered liver foci and hepatocellular carcinoma induced by diethylni-trosamine or A^-acetylaminofluorene in rats. Cancer Res 1985;45:5489-95.

15. Daoud AH, Griffin AC. Effect of retinoic acid, butylated hydroxytoluene, selenium, and sorbic acid on azo-dye hepato-carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett 1980;9:299-304.

16. Griffin AC. Role of selenium in the chemoprevention of can-cer. Adv Cancer Res 1979;29:419-42.

17. Reddy BS, Rivenson A, El-Bayoumy K, et al. Chemo-prevention of colon cancer by organoselenium compounds and impact of high- or low-fat diets. J Natl Cancer List 1997; 89:506-12.

18. Thompson HJ, Becci PJ. Selenium inhibition of iV-methyl-A'-nitrosourea-induced mammary carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst 1980;65:1299-301.

19. Ip C, Ip MM. Chemoprevention of mammary tumorigenesis by a combined regimen of selenium and vitamin A. Carcinogenesis 1981;2:915-18.

20. Milner JA. Effect of selenium on virally induced and trans-plantable tumor models. Federation Proc 1985;44:2568-72. 21. Clark LC, Cantor KP, Allaway WH. Selenium in forage crops

and cancer mortality in U.S. counties. Arch Environ Health 1991;46:37^2.

22. Shamberger RJ, Tytko SA, Willis CE. Antioxidants and can-cer VI. selenium and age-adjusted human cancan-cer mortality. Arch Environ Health 1976;31:231-5.

23. Van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van't Veer P, et al. A prospective cohort study on selenium status and the risk of lung cancer. Cancer Res 1993;53:4860-5.

24. Kok FJ, de Bruijn AM, Hofman A, et al. Is serum selenium a risk factor for cancer in men only? Am J Epidemiol 1987,125:12-16.

25. Knekt P, Aromaa A, Maatela J, et al. Serum selenium and sub-sequent risk of cancer among Finnish men and women. J Natl Cancer Inst 1990;82:864-8.

26. Van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van't Veer P, et al. A prospective cohort study on toenail selenium levels and risk of gastrointestinal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:224-9. 27. Willett WC, Polk BF, Morris JS, et al. Prediagnostic serum

selenium and risk of cancer. Lancet 1983;2:130-4.

28. Helzlsouer KJ, Alberg AJ, Norkus EP, et al. Prospective study of serum micronutrients and ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996;88:32-7.

29. Nomura A, Heilbrun LK, Morris JS, et al. Serum selenium and the risk of cancer, by specific sites: case-control analysis of prospective data. J Natl Cancer Inst 1987;79:103-8.

30. Coates RJ, Weiss NS, Dating JR, et al. Serum levels of sele-nium and retinol and the subsequent risk of cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1988;128:515-23.

31. Garland M, Morris JS, Stampfer MJ, et al. Prospective study of toenail selenium levels and cancer among women. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:497-505.

32. Yu MW, Hsu FC, Sheen IS, et al. Prospective study of hepato-cellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in asymptomatic chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:1039-^47. 33. Miller KW, Yang CS. An isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography method for the simultaneous analysis of plasma retinol, a-tocopherol, and various carotenoids. Anal Biochem 1985;145:21-6.

34. Negretti de Bratter VE, Bratter P, Tomiak A. An automated microtechnique for selenium determination in human body flu-ids by flow injection hydride atomic absorption spectrometry (FI-HAAS). J Trace Elem Electrolytes Health Dis 1990; 4:41-8.

35. Willett W, Stampfer MJ. Total energy intake: implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol 1986;124:17-27. 36. Thuluvath PJ, Triger DR. Selenium in chronic liver disease. J

Hepatol 1992; 14:176-82.

37. Dworkin B, Rosenthal WS, Jankowski RH, et al. Low blood selenium levels in alcoholics with and without advanced liver disease. Correlation with clinical and nutritional status. Dig Dis Sci 1985;30:838-44.

38. Tanner AR, Bantock I, Hinks L, et al. Depressed selenium and vitamin E levels in an alcoholic population. Possible relation-ship to hepatic injury through increased lipid peroxidation. Dig Dis Sci 1986;31:1307-12.

39. Arciszewska LK, Martin SE, Milner JA. The antimutagenic effect of selenium on 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and metabolites in the Ames salmonella microsome system. Biol Trace Elem Res 1982;4:259-67.

40. Jacobs MM, Matney TS, Griffin AC. Inhibitory effects of sele-nium on the mutagenicity of 2-acetylaminofluorene (AAF) and AAF derivatives. Cancer Lett 1977;2:319-22.

41. Leboeuf RA, Laishes BA, Hoekstra WG. Effects of selenium on cell proliferation in rat liver and mammalian cells as indi-cated by cytokinetic and biochemical analysis. Cancer Res

1985;45:5496-504.

42. Spyrou G, Bjomstedt M, Skog S, et al. Selenite and selenate inhibit human lymphocyte growth via different mechanisms. Cancer Res 1996;56:4407-12.

43. Turner RJ, Finch JM. Selenium and the immune response. Proc Nutr Soc 1991;50:275-85.

44. Hoffmann D, Hecht SS. Advances in tobacco carcinogenesis. In: Cooper CS, Grover PL, eds. Chemical carcinogenesis and mutagenesis I. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 1990: 63-102.

45. Blot WJ, Li JY, Taylor PR, et al. Nutrition intervention trials in Linxian, China: supplementation with specific vitamin/mineral combinations, cancer incidence, and disease-specific mortality in the general population. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:1483-92.