Vol. 32, 51-83, August 2013

The Linguistic Features and Socio-Psychological

Effects of English Mixing in Advertising in Taiwan:

Copywriters’ Interviews

Jia-Ling HsuDepartment of Foreign Languages and Literatures National Taiwan University

Abstract

This study investigates how the following three underlying factors contribute to copywriters’ development of Chinese-English code-mixed advertising discourse in Taiwan: (1) the socio-psychological effects of English mixing in advertising; (2) the criteria that determine the linguistic forms copywriters employ in mixing English; (3) the importance of intelligibility to consumers when English is used in advertising copy. The corpus of data of this study was drawn from seventeen hours of taped interviews conducted with nine copywriters from prestigious local and internationally based advertising agencies. Qualitative analysis was used to examine the data. According to the copywriters interviewed, the two most prominent features conveyed by the use of English in advertising copy are internationalism and appeal to the younger generation, accompanied by features such as premium quality, authenticity, and a metropolitan orientation. In advertising products featuring internationalism, copywriters use English narration or dialogues in commercials to develop the storyline and use English to state brand names and product names. However, to ensure the intelligibility of the English text to the targeted audience, the informative part of the ads is disseminated in the form of Chinese subtitles, supers, and voice-overs. In marketing products appealing to the younger audience, intrasentential lexical mixing copy and English slogans containing simple English vocabulary are employed to create a sense of trendiness and fun in the advertised products.

Keywords: linguistic features, socio-psychological effects,

English mixing in advertising in Taiwan, copywriters' interviews, internationalism

Introduction

English, as a global language, “has come to be widely used for the specific purposes of advertising to reach international target groups in various countries” (Planken, Van Meurs, & Radlinska, 2010, p. 225). As Martin (2002, p. 382) notes, in world advertising, there is “the indisputable preference across cultures for English as a pair-language.” English mixing, as a worldwide development in global advertising, has been researched by Alm (2003), Baumgardner (2008), Bhatia (1992, 2000, 2001, 2006), Bhatia and Ritchie (2006), Chen (2006), Dimova (2012), Gao (2005), Gerritsen, Korzilius, Van Meurs, and Gijsbers (2000), Gerritsen et al. (2007a, 2007b), Hamdan and Abu Hatab (2009), Hilgendorf (2010), Lee (2006), Martin (1998, 2002, 2007, 2008), Petery (2011), Ustinova (2006), and many others. However, most of these studies employ discourse analysis as the major approach to describe the use of English in non-Anglophone advertising. Research in this area based on copywriters’ interviews is relatively rare, for instance, Martin (1998) and Alm (2003).

Martin (1998) observes that in the area of research on advertising, linguists seldom check with advertising professionals in analyzing their data. Hence, most linguistic research on advertising is “limited to surface features of the advertisements themselves, without addressing with any significant amount of detail the creative processes involved in designing an advertising campaign” (p. 307). Therefore, in investigating English mixing in advertising, Martin (2002) advocates the approach of interviewing marketing specialists because it reveals these specialists’ “motivations for using code-mixed copy and the effectiveness of this particular approach to advertising” (p. 400). Martin (1998) interviewed a team of advertising specialists in an advertising agency in Paris—including four copywriters, a creative director, an account manager, and a legal consultant—to understand how these experts collaborated in the creative process of advertising copywriting in France. Martin examined such issues as the symbolic meaning of English for French consumers and the role of English in global advertising campaigns. These interviews show that for French advertisers, English is often regarded as an

international language, a high-tech language employed frequently in the sciences and computer industry, and the language of the business world.

Alm (2003) conducted a questionnaire survey of twenty-five advertising experts in twenty-five different advertising agencies in Quito, Ecuador’s capital, in 2002. These experts were surveyed on “what parts of the advertisement” (p. 144) in which English occurred most frequently and the reasons for using English in advertising copy. The survey indicates that the most frequent categories of English mixing are cliché words and expressions, followed by brand names and logos. The main reasons for using English in advertising copy include attention-getting, using short English words with multiple meanings for word play, maintaining the original English slogan without providing any translation, using English technical and vogue words, and using English at the request of clients of multinational companies and brands.

The present study attempts to explore the underlying factors involved in copywriters’ strategies in the development of Chinese-English code-mixed advertising discourse in Taiwan by examining the following issues: the socio-psychological effects of English mixing in advertising, the criteria that determine the linguistic forms copywriters employ in mixing English, and the significance of intelligibility to consumers when English is employed in advertising copy.

Methodology

Following Kachru’s (1990) definition, English mixing is broadly defined in this paper as the transfer of English words, phrases, and sentences into Chinese at intersentential and intrasentential levels. The corpus of data of this study was drawn from seventeen hours of taped interviews conducted from September 2002 to August 2007 with a total of nine copywriters, including seven executive creative directors, from a variety of prestigious local and internationally based advertising agencies, such as J. Walter Thompson, Ogilvy & Mather Advertising, Leo Burnett, and Lowe. All these companies deal with the advertising of general commodities as opposed to residential

real estate properties. For a discussion of interviews with real estate copywriters, see Hsu (2012)1 In this research project, each copywriter was interviewed from one and half hours to two hours. Some copywriters were interviewed more than once for follow-ups.

Following Martin (1998), the following interview questions were formulated, with the first and the third questions adapted from Martin’s research (p. 309).

1. What are the socio-psychological effects copywriters intend to convey to consumers via English mixing in ads?

2. What are the criteria that determine the extent of English used by copywriters and the linguistic forms they employ in mixing English? 3. How important is it for the code-mixed text to be intelligible to consumers when copywriters mix English?

Other than interviews, a second source of data consisted of seventeen TV commercials and three print advertisements provided by six of the copywriters interviewed. Three of the nine copywriters interviewed did not offer the researcher any advertisements for reference after the interviews. Five of them submitted TV commercials, which will be used to illustrate how copywriters in Taiwan use English to create a variety of socio-psychological effects on the target audience. Qualitative analysis was performed on the transcribed data of the copywriters’ interviews, TV commercials, and print advertisements. The content of this paper is entirely based on the transcriptions of the tape-recorded interviews with copywriters and of the commercials and print ads they provided. Because of the limited number of ads provided by the copywriters, certain product types are studied more than others; for example, a large proportion of the commercials used for illustration in this paper pertain to automobiles.

Results

Based on the interviews, all the copywriters agree that their top priority in advertising agencies is to provide Chinese copywriting rather than English copywriting. English copywriting is commissioned to native speakers of English. At the beginning of the advertisement creation process, copywriters who are commissioned to create an advertising campaign are not concerned about what language to use, unless the projects they work on involve standardization in the promotion of an international super brand such as Nike. The idea of utilizing English emerges during the process of brainstorming among the copywriters when they attempt to explore the concepts of advertised products.

Depending on the development of the concepts and marketing goals, including product type, target audience, and requests made by clients, a variety of advertising strategies of mixing English are employed to convey various socio-psychological effects: internationalism, premium quality, authenticity, a metropolitan orientation, urban experiences, middle-class lifestyle, and the trendy taste of the younger generation. All the copywriters interviewed agreed that the two most distinguishing socio-psychological features of English are internationalism and its appeal to the younger generation. I will examine how English is used to convey these two major features in the following three situations.

First, to generate a sense of internationalism for imported products, clients request either a globalization or glocalization marketing strategy to emphasize the international brand image and the premium quality of the advertised products. For globalization, monolingual English copy or slogans are used; for glocalization, Chinese-English code-mixed copy or monolingual Chinese copy is employed.

Second, when local brands intend to market their products internationally or to project an international brand image in their advertised products domestically, English is used in the naming of these brands or their products. Sometimes, bilingual mix TV commercials with Chinese subtitles are produced.

Third, to appeal to the younger generation and cope with their cultural trend of “mix and match” online language behavior, intrasentential English lexical mixing or English slogans are frequently used.

Overall, English is most likely to be employed for international brands’ products; high-tech products, such as computers and automobiles (English is used for the names of almost all automobiles); fashionable products; and products targeting the middle-class, urban audience, and younger generation. This paper is organized according to the manner in which copywriters use English to convey the two major features, a sense of internationalism and appeal to the younger generation, and such other features as authenticity, premium quality, and a metropolitan orientation. The analytical framework provided by Sinha (2004, 2007) is adopted in the discussion of internationalism in sections Globalization and Glocalization.

Using English to Feature Internationalism in Advertised Products

Products of international brands. To feature internationalism in imported products or international brand products, either of the two strategies may be employed: globalization vs. glocalization.

Globalization. According to Dumitrescu and Vinerean (2010),

globalization is defined as “the tendency toward an international integration of goods, technology, information, labor, capital, or the process of making this integration” (p. 151). When it comes to advertising, globalization involves global execution, namely, standardization, so that a global brand maintains its global image and runs the same advertisement for the brand across all regions, usually in the same language—English (Sinha, 2007).2 In other words, this marketing strategy is “Think global, act global.”

In such global advertising campaigns, local dealers import entire monolingual English commercials, including English slogans, directly from abroad without any local adaptation for the “financial reason” that it is “less expensive” to use standardized English words and slogans than to provide adapted translated versions in different countries (De Mooij, 1994; Jain, 1993, quoted in Hornikx & Starren, 2006, p. 126). In addition, English is used for

“the image reason,” namely, “to create an international image for the brand and the company” (Gerritsen et al., 2000; Alm, 2003; Piller 2001, 2003, quoted in Hornikx & Starren, 2006, p. 127). That is, English is used “to position [the company] as a global player in the world economy . . . to give the company an international and contemporary orientation” (Hornikx & Starren, 2006, p. 127). In other words, the exclusive use of English signals globalization (Piller, 2003, p. 176). Instruments such as the brand name, logo, and slogan are used to create such a global image (Hornikx, Van Meurs, & Boer, 2010, p. 170). Nike’s slogan “Just do it” provides a typical example, in which sportsmanship is a global insight of all sportsmen.3

Glocalization. Glocalization combines features of globalization and localization (Bhatia, 2000, quoted in Piller, 2003, p. 176). In advertising, according to Sinha (2007), glocalization involves glocal execution, which means that “the same idea is translated for the local culture—it is based on the same insight, but the models, locations and language used are local, for greater empathy.” Such ads are intended to convince the users that using the advertised brand will make them members of an international community. Two tactics are employed based on clients’ requests and marketing goals: local customization and local execution.

Local customization. Local customization refers to a situation in which a

global brand is customized or glocalized to tap into the local language and culture. In most cases, the source is directly imported from abroad, so all the voice-overs, subtitles, and slogans of monolingual English television commercials and the body copy of print ads are in English. The first task encountered by clients and local copywriters is how to adapt and provide Chinese translations of these directly imported ads or commercials to suit the local market. During the process of local adaptation, copywriters have to retain the original meaning of the English copy in their Chinese translations, a process that Hornikx and Starren (2006) refer to as “translatability” (p. 127), and also exercise their own local creativity. Although some advertising companies in other countries, such as the ones in Holland interviewed by Gerritsen et al. (2000), may consider providing adapted translations too

expensive, copywriters in the internationally based agencies in Taiwan concur that when they are commissioned to an advertising campaign involving TV commercials imported from abroad, most clients request that commercials be localized and Chinese translated versions be provided instead.

According to one of the copywriters interviewed, the vice president of an internationally based company, the more internationalized a brand is, the more localized it wishes its advertising campaign to be. To illustrate, for some international brands, it is more efficient to prepare a single Chinese translated version of an ad or a TV commercial that can be used across the board in all such Chinese-speaking areas as China, Singapore, and Taiwan. Sometimes, clients also request English-Chinese bilingual copies of commercials.

For example, two Heineken’s TV commercials were provided by interviewed copywriters, one bilingual and the other monolingual. The bilingual copy features a magic show in which the magician tries to take a Heineken beer from a male viewer in the audience. Though the magician hypnotizes the male viewer and believes that he will succeed in getting the beer, the male viewer does not release the beer. What follows is a battle to see who will win the Heineken. This commercial starts with a warning in Chinese, “hejiu bukaiche, anquan youbaozhang (喝酒不開車,安全有保障)” [No drunk driving is allowed so that one’s safety is guaranteed], a warning made by the government of Taiwan, which shows up in all alcohol advertisements. While the magician and the audience are wrestling for the beer, both the English super, “win hands down,” and its Chinese translation, “shengquan

zaiwo (勝券在握)” appear line by line on the screen.4 In the end, the English slogan, “It could only be Heineken” and its Chinese translation, “jiushiyao

hainigen (就是要海尼根)” appear line by line in the super. The translated

slogan is also narrated in Chinese.

In the monolingual Chinese commercial, Jennifer Aniston plays a female supermarket customer who is trying to reach two bottles of Heineken at the top of a shelf. While she is unsuccessfully making this attempt, a man who seems to be attracted to her approaches her, and the Chinese super “meili

nandang (魅力難擋)” [an irresistible charm] shows up on the screen. While

Aniston believes that she can charm the man to do her the favor of grabbing the beer for her, the man suddenly takes the beer away for himself. At the end, the Chinese translation of the brand slogan, “It’s all about Heineken,” “jiushiyao hainigen (就是要海尼根)” appears both in the super and in the voice-over.5 The above instances indicate how copywriters convey the same type of information, such as the brand slogan of Heineken, in both bilingual and monolingual Chinese advertising copy when they customize commercials directly imported from abroad.

Local execution. Local execution is used in glocalization “when the consumer needs, motivations and cultural context are unique to that market” (Sinha, 2007). In Taiwan, when international brand products are to be advertised or an international brand is introduced in the Taiwan market, local copywriters are commissioned to create TV commercials that meet the needs of local consumers. However, to retain the international image of the brand, Caucasians are recruited as actors and actresses, and Chinese-English bilingual copy with bilingual voice-overs and supers is used in these commercials.

A series of TV commercials produced by the locally based Ford Motor Company exemplify how copywriters use English mixing to create the socio-psychological effects intended for local consumers. According to the copywriters who provided these commercials, back in the 1990s, Chinese was the only language used in advertising Ford sedans, for example, Lazer sedan, for which the Chinese product name was “jinquanleida (金全壘打)” [golden home run]. In the commercial promoting this product, the fashionable design and elegant style of the sedan were emphasized. However, since the commercials were all spoken in Chinese, including the brand name, “fute (福特)”, the transliteration of Ford, the advertised products were considered too localized and low end by the market. Accordingly, Ford Motor Company decided to upgrade and internationalize its brand image. It changed its advertising tactics in commercials and started to use only English to express its brand and product names, such as Metro Star, Tiera, and Lotus.6

The following series of TV commercials produced by Ford shows how English was employed to upgrade the image of the brand and its products and thereby boosted the sales of Ford products.

The first commercial features a prototype concept of a blind man who cannot see but who knows which brand of vehicle is the best owing to his exquisite taste. Nevertheless, in creating such a character, a Chinese blind man cannot serve as the prototype character because most blind people in Taiwan work as masseurs. Such a prototype image would be too low-scale. Consequently, to highlight the good taste of the blind character, the copywriter designing this commercial copied Al Pacino’s image from the Hollywood movie Scent of a Woman in which Al Pacino starred as the well-cultivated Lieutenant Colonel Frank Slade.

In this commercial, a Western blind man with flawless taste, strolls in a park, accompanied by a friend who can see. This blind man is able to identify in English the brand name of the perfume used by a woman passer-by as “Chanel” and the brand name of the camera used by another passer-by as “Leica.” His perfect guesses amaze his friend. However, when a Ford Metrostar parks by his side, he mistakes this Ford vehicle for a Mercedes-Benz, saying “Benz, nice car.” At this moment, a Chinese-English code-mixed super appears and a voice-over states, “Ford Metrostar quanxin

shangshi ( 全 新 上 市 )” [new in the market]. Then the Chinese

super ”huanying lilin shangche (歡迎蒞臨賞車)” [You are welcome to visit our car dealers] appears on the screen. The commercial concludes with the voice-over saying the brand name, Ford, in English.

In this commercial, according to the copywriter who made it, the English voice-over of the blind man’s monologue, the product name, and the brand name, are used to convey a sense of internationalism, premium quality, and exquisite taste in the advertised product. As Piller (2001) observes, in German advertising, the voice of authority explicitly occurs in the form of a voice-over in TV commercials and also when a switch is made from German into English, thereby “vesting English with the meaning of authority, authenticity, and truth” (p. 159). As in German advertising, Taiwanese

copywriters also mix English in commercials to convey a sense of authority and authenticity.

However, to ensure that the local audience has no difficulty understanding the main message of the commercial and the essential marketing information about the advertised product, the copywriter provides Chinese subtitles of the blind man’s English monologue and uses Chinese supers to convey important marketing information about the advertised product, such as the new vehicle being introduced to the market and customers being welcome to visit local car dealers. This bilingual code-mixing strategy—to use English to highlight the internationalism and premium quality of the advertised products and to use Chinese to deliver the informative part of the ads—is witnessed repeatedly in other commercials featuring internationalism in advertised products, as will be discussed in the next section Products of domestic brands. Due to the success of Ford’s change in advertising tactics, since this commercial was shown on TV, sales of Ford automobiles have increased tremendously.

The next commercial, also produced by the local Ford Company, promotes the European image of Ford sedans. Ford automobiles were originally produced in the U.S.A. Many Taiwanese consumers did not appreciate American automobiles, since they looked heavy, seemed to be fuel-inefficient, and lacked good design and quality. After Ford moved its design center and production lines to Europe, it created a new European image of Ford sedans. This was the image Ford intended to create in Taiwan, suggesting that Ford was a premium brand in Germany and Europe. The following TV commercial illustrates how English was used to create this new image.

This commercial implies that Germans design their cars to meet the challenges imposed by the Autobahn. To show authenticity, the storyline was set in Germany, but actually the commercial was shot in Taiwan and Caucasians were recruited as actors. The commercial begins with an English voice-over, accompanied by Chinese subtitles, stating that the German Autobahn, a highway with no speed limit, challenges the capability of both

drivers and cars. It continues by stating that although Formula One World Driver’s Champion Schumacher is German, not all Germans are Schumacher; therefore, on the Autobahn, Germans do not rely on driving skills but engineering. After this English narration finishes, Chinese super appears on the screen, “yideguo Autobahn yanke biaozhun dazao, xingneng, pinzhi,

anquan (依德國 Autobahn 嚴苛標準打造性能,品質,安全)” [the criteria of

performance, quality, and safety of Ford sedans are based on the rigid standards set by Autobahn.] Then the voice-over and the super of the product name, 07 All New Focus, and the brand name show up in English. Though this commercial tells the story of German car design, English rather than German is used as the advertising language, since very few people in Taiwan can understand German. The overall message conveyed in this commercial is that Ford sedans perform as well as any European sedans, such as BMW, Benz, and Audi, in meeting the challenges imposed by the Autobahn.

According to the copywriters creating these four commercials, the use of English brand names rather than Chinese brand names not only suggests that advertised products are of superior quality, but also distinguishes the urban, cosmopolitan lifestyle from the rural lifestyle. Generally speaking, since 2000, in northern Taiwan, which is more cosmopolitan, English has been extensively and directly employed in automobile advertisements, as shown in the previously discussed sections. In contrast, in southern Taiwan, which is less cosmopolitan and where English is not as common, Chinese translation of English brand names or product names has been offered by local car dealers. For instance, Corona is transliterated as “kelena (可樂娜)”. The difference in the use of English in automobile ads in southern and northern Taiwan indicates an important effect of English mixing in advertising—to feature the metropolitan and urban lifestyle.

In addition to automobiles, English is also utilized to market international financial institutions and beauty bath products in order to generate an image of internationalism and high quality.

When J. P. Morgan Asset Management first started to do an advertising campaign in Taiwan, the company name was not known by local people. To

deliver an international, professional, and reliable image of J. P. Morgan Asset Management, which was an internationally renowned financial services and investment institution, the client requested that an international setting and Caucasian actors were to be used in its TV commercials.

One of the commercials used here as an illustration is divided into two parts: the first part consists of an English dialogue, accompanied by Chinese subtitles; the second part comprises a Chinese super and voice-over of the main message of the ad. The shot starts with several male travelers attacked, trapped, and stranded by a sand storm in a dessert, crying “Help!” in English. One man answers “Get down. Don’t worry.” After the sand storm is gone, while most of the travelers are still in shock, crying “What’s going on here?” and worrying about the amount of water left for survival, the man who previously calms everyone else down, uses water to get sand off his face, saying “Don’t worry.” Then rain starts to pour down. At this moment, the Chinese super and the voice-over appear simultaneously, “yinwei yanguang

jingzhun, cai neng zaoyibu dongcha quanju, quanqiu jijin zhuanjia, mogenfuminglin, yongyuan biqushi zaoyibu (因為眼光精準,才能早一步洞

察 全 局 , 全 球 基 金 專 家 摩 根 富 明 林 , 永 遠 比 趨 勢 早 一 步 )”, which is translated literally as “because J. P. Morgan Asset Management has such good investment insight, it can always help its clients to make proper investments before any new trend of development occurs.”

In this ad, the Chinese brand name, mogenfuminglin (摩根富明林), is partly a Chinese transliteration of the English brand name. By capitalizing on an English dialogue with the Chinese translation in subtitles, this commercial conveys an image that J. P. Morgan Asset Management is an authoritative international financial institution that provides good vision in making investments. Due to the success of this commercial, other internationally based financial services companies, such as American-based Prudential Financial and German-based Allianz Group, started to adopt the style of this ad in their own TV commercials.

The next instance concerns an international beauty bath brand, Lux. Before 2002, Lux clients recruited Hong Kong superstars such as Maggie

Cheung(張曼玉)and Karen Mok (莫文蔚)to endorse its beauty bath products. Chinese was the language used to communicate to the target audience in Taiwan. However, as other beauty bath brands also recruited Hong Kong celebrities to endorse their products, since 2002, Taiwanese copywriters recruited Hollywood superstars such as Liv Taylor and Charlize Theron to endorse Lux products in commercials and thereby distance Lux from other brands. These commercials were shot in the US to create a sense of internationalism and authenticity. Because this was the first time that Hollywood movie stars were invited to endorse Lux products, the clients had to choose between English and Chinese as the language used in the commercials.

At first, the clients were worried that, with a sudden shift from Hong Kong Chinese movie stars to American Hollywood stars and a shift of the advertising language from Chinese to English, consumers might not accept the new way of communication. In contrast to the situation in Singapore or Hong Kong, English was not that common in Taiwan. Therefore, the clients requested that Liv Taylor’s script should be dubbed in Chinese. Later, many viewers who previewed this commercial responded that they found it odd and incompatible to have an American superstar speak standard Mandarin Chinese. In response to the viewers’ feedback, the clients accepted the English version of the commercial, which was subsequently well received by the market.

Therefore, in 2003, when Charlize Theron endorsed the Lux product, she spoke English, but Chinese subtitles appeared on the screen. The copywriter who created this series of commercials said that although English might not be as common in Taiwan as in Hong Kong or Singapore, having a Hollywood super star speak English delivered a supreme sense of internationalism for the advertised product. Because these commercials targeted a well-educated audience who were familiar with English, the English language barrier which might exist for parts of the population was not a concern for this copywriter.

have used a similar language formula in creating all four of these commercials. This language formula is analyzed in the next section.

Products of domestic brands. English is used in advertising not only international brands but also local brands to create an aura of internationalism for advertised products. In the promotion of local brands, English is used differently for products marketed internationally than for those only marketed domestically. When a local brand attempts to market its products internationally and to create an international image domestically, copywriters first create an English brand name. For example, Acer (personal computers) and Travel Fox (sports shoes) are local brands known both internationally and locally by their English names. They were first introduced into the local market with their English names, but later these names were translated into Chinese as hongji (宏碁) and lűhu (旅狐). Therefore, domestic consumers tend to think that these brands are international.

While discussing this phenomenon, a copywriter commented that Taiwanese people idolize foreign commodities. Hence, some local brands are first given English names to make them appear to be foreign imports. Such idolatry of foreign imports packaged in English is not unique to Taiwan; in fact, it is widespread. For example, a salesman in Mexico answered, “ I would sell only half, if I did not use English” when responding to why “half” Spanish and “half” English were used in an advertisement (quoted in Bhatia & Ritchie, 2006, p. 517). In Ecuador, a copywriter commented about marketing, “people still think that what comes from abroad is better, and if it’s in English—it’s even better” (Alm, 2003, p. 152). All the above comments and quotes suggest how English, as the unprecedented global marketing language, has cast its glamour on consumers across different languages and cultures.

The next example concerns a local tea product, chaliwang (茶裏王). The literal meaning of its Chinese product name is “the king of all the teas.” When it was exported to Thailand and Singapore, an English product name, Chaliwang, a transliteration of the Chinese product name, was created, but the meaning of the Chinese product name, the king of all the teas, was not

translated and was not shown with its English product name. However, because Chaliwang sounds like the English name of a Chinese man named Charley Wang, it catches people’s attention and is easy to remember.

English is also used to foster a sense of internationalism in domestic brands even when a local brand only targets local consumers in order to make them believe that it is part of an international community. Take the local fitness center Jiazi(佳姿)as an example.7 Its customers were mainly local middle-aged housewives. Around 2000, to recreate its corporate image, Jiazi introduced its customers to Pilates, a new physical fitness system that encourages the use of the mind to control the muscles. To convey a sense of authenticity and internationalism in the advertised product, a commercial was shot with two foreign instructors of Pilates, one American and one German, doing Pilates and having a conversation in English about how doing Pilates makes them happy. The dialogue starts with “Are you happy? Yes, I am happy,” continues with a discussion of the benefits of practicing Pilates, and ends with the voice-over of the English product name “Pilates,” which, transliterated as “pilatizi (皮拉提茲)”, simultaneously appears in a Chinese super. Although this commercial featured an English dialogue and the citing of the English product name, the client was not concerned that the audience might have difficulty understanding what the advertised product was about since Chinese subtitles for the English dialogue and a Chinese super of the English product name were provided to convey the informative part of the ad to the local audience.

Because this commercial was shot at a time when Pilates was popular with upper-class women in New York City, the copywriter stressed the idea that if one practiced Pilates at a Jiazi Fitness Center, one was also keeping pace with international popular culture. By using the English dialogue and the English product name, the local fitness center Jiazi created an image of authenticity, internationalism, and fashion.

A review of the strategies of various copywriters’ using English to convey an effect of internationalism in advertised products shows that no matter whether they are international brands or local brands, they all follow a

similar language formula in producing TV commercials. In narrating the storyline, monolingual English narration or dialogue is used. Brand names and product names are uttered in English. Caucasians are recruited to play the roles. All these tactics are used to create a sense of internationalism, authenticity, authority, and premium quality in advertised products. On the other hand, to disseminate essential marketing information without creating any language barrier (Hsu, 2012, p. 202) and to ensure that the informative part of these commercials is clearly understood by the local audience, the factual information is delivered in Chinese in the form of subtitles, supers, and voice-overs. This bilingual strategy is also observed globally.

Ray, Ryder, and Scott (1991) note that the purposes of advertisements are to attract consumers’ attention and inform them of product characteristics. In a bilingual copy of European advertisements, the important information is carried in the native language, while English words and phrases are employed for attention-getting and creating “a receptive mood” (p. 90) rather than for their informative content.

According to Hsu (2012), real estate advertising in Taiwan uses Chinese to deliver the important information about advertised property, such as the product characteristics, whereas English is mixed to “enhance the attractiveness and authoritativeness of the advertisements” (p. 202).

In German advertising, Piller (2001) observes that “the authority of the English voice is usually reinforced by . . . male voices and co-occurrence in the spoken and written mode in TV commercials” (p. 163). By contrast, German is used for the body copy and all the factual information, such as outlet and contact details, signaling “doubt about the bilingual proficiency of the audience.”

Baumgardner (2008) asserts that in Mexican advertisements, when English is used as language display, whether a reader understands it or not does not matter, because it does not appear in an ad “for informational purposes” (p. 38).

By the same token, in Japanese advertisements, texts and expressions of foreign languages used are not meant for the ordinary Japanese audience to

understand. Although they might understand individual lexical items, the primary portion of the text is “simply used to create an image and attach prestige value to the products being advertised” (Blair, 1997, quoted in Baumgardner, 2008, p. 38).

In sum, all the observations made above indicate that English plays a universal role in global advertising, one that serves as “not only as an attention-getter but also a brand image reinforcer, mood enhancer” (Martin, 1998, p. 336).

Using English to Appeal to the Trendy Taste of the Younger Generation All the copywriters concur that besides internationalism, another major purpose of English mixing in advertising copy is to appeal to the younger generation, to accommodate their cultural preference for “mix and match,” to create a sense of being trendy and having fun with the advertised products. This appeal is based on two grounds. First of all, Taiwan as an island is easily influenced by foreign cultures because of its colonial history. Second, in their advertising copy, copywriters utilize young people’s new web language, in which they freely mix and match English, Southern Min Dialect and Mandarin Chinese in typing online messages. The English used online is popular and simple. Therefore, copywriters employ simple English to promote products such as cell phones and young people’s drinks, in order to provide a sense of familiarity and trendiness in the advertising copy. The results of the interviews indicate that copywriters use three main types of advertising copy to appeal to the younger audience: intrasentential English lexical mixing copy, English slogans, and bilingual mix copy of commercials.

Intrasentential English lexical mixing copy. Mixing simple English words as puns intrasententially is common in print advertisement in Taiwan, for example, “kaixinFUNshujia (開心 FUN 暑假)” [to have a summer vacation happily]. In the code-mixed expression, “Fun” is used to serve two meanings. On the one hand, “Fun” is a near-homophone of the Chinese word “fang (放)” [take]. “Fangshujia (放暑假)” means to take a summer vacation. On the other hand, “Fun” means that taking a summer vacation can be fun.

Another example of English word play occurs in a print advertisement of mod’s hair, a Paris-based chain of beauty salons. In this advertisement, a Chinese-English mixed slogan “youGozhi (有 Go 直)” [sufficiently straight] is created to refer to hair straightened by the advertised product. “Go” is a homophone of the Chinese word “gou (夠)” [enough]. If the Chinese word “gou ( 夠 )” were used, the slogan would not be as graphically attention-getting. By using the English “Go” instead of the Chinese “gou (夠)”, two purposes are achieved. “Go” not only conveys the Chinese meaning of “enough”, but also connotes a dynamic sense of energy.

A third example displays the effect of word play by mixing intrasentential English vocabulary to create a sense of trendiness and fun in a bank commercial that targets young consumers in debt. In recent years, young Taiwanese have become major users of credit cards, but many of them are unable to repay their credit card debt. In the commercial, a young man tries to dye a dog to make it look like a wanted missing dog, so he can be rewarded for returning the dog and thus afford to repay his debt. The Chinese super shown on the screen “Are you too much in debt?” implies that the young man does not need to resort to such drastic measure to repay his debt. In the end, a Chinese-English mixed financial service name “dai me more (貸 me more)” from Hi Bank appears as the final solution to the problem of young people’s debt. In this code-mixed slogan, the Chinese word “dai (貸)” means “loan”. Therefore, “dai me more (貸 me more)” means “loan me more.” Furthermore, “dai me more (貸 me more)” also sounds like the transliterated name of the Hollywood movie star Demi Moore. English word puns are employed by copywriters to create a sense of fun and humor to attract the attention of young people. This device is also witnessed in Ecuadorian advertisements where many short English words with multiple meanings are used for word play (Alm, 2003, p. 150).

According to several copywriters, although intrasentential lexical mixed copy involving simple English vocabulary appeals to the young audience, it is not preferred by international-based advertising companies because such

advertising copy does not help to upgrade the brand image of advertised products.

English slogans. In addition to using intrasentential English lexical mixing in advertising copy, local copywriters also create slogans to accompany the brand name in advertising campaigns to promote the products of both domestic and international brands. According to Piller (2001), slogans are used to “encapsulate the identity or philosophy of a brand” (p.160); consequently, the language employed in an advertisement’s slogan becomes “the language of the advertisement’s ‘master voice,’ the voice that expresses authority and expertise” (p.160). In Taiwan, English represents authority and expertise; therefore, English slogans are frequently utilized as the master voice in advertising campaigns. However, to get around the problem of the readers’ language barrier, the English used in these slogans is simple and easy to read. For example, Fareastone, a local cell phone company, uses simple English in its brand slogan “Just call me, be happy,” to accommodate the general public’s relatively low English proficiency. The copywriter who created this slogan stressed that he needed to consider whether the general public could understand the English words used in the slogan in order to avoid producing a language barrier. In consequence, he employed very simple English words, so that this slogan would be well received in the market.

In addition to local cell phone companies, local banks also employ English slogans to communicate with their customers, especially young customers. For example, ZhangHua Bank uses “Touch us” as its slogan. China Trust’s slogan is “We are family.” According to one copywriter, this English slogan yields a greater sense of quality than its Chinese semantic counterpart, “women doushi yijiaren (我們都是一家人)” [we are all family], which only suggests familiarity and neighborliness in Chinese. The following example illustrates how a local bank uses an English slogan in a TV commercial to communicate effectively with young Taiwanese.

This English slogan “We Share” was created in promoting a new service product marketed by China Insurance Company to achieve the following

three goals.8 First, the name of the company, China, was so geographically limited and old-fashioned that it did not appeal to the younger generation. In order to create a new brand image of this long-established insurance company, the copywriters created the English slogan “We Share” to attract the attention of the younger generation. Secondly, since the product advertised was a participating insurance policy, the slogan emphasized that the company would share its profits or gains with the policy buyers. Thirdly, since the company was recruiting new sales associates, the slogan suggested that they would be like family members of the insurance policy holders and share all their joy and suffering.

Before deciding on using “We Share” as the final choice, copywriters thought of an alternative expression “We share with you.” However, this expression was longer than “We Share.” Moreover, the copywriters believed that Taiwanese people’s English proficiency was not very good, but as long as the audience could understand the key word “share,” the goals of the advertising campaign would be fulfilled. In order not to alienate any of the audience, the copywriters picked “We Share” as the simplest and most easy-to-read of the twenty proposed slogans.

In one of the TV commercials used for this advertising campaign, a basketball game is going on. For most people, the purpose of ball games is to win, but in this commercial, one young player hands the ball to a player on the other team because his father works in China Insurance Company, where the concept of sharing is highly valued. The commercial closes with the English slogan “We Share.”

Therefore, by creating the new English slogan “We Share,” the brand image of the old insurance company was repackaged, attracting the attention of the younger generationand boosting the brand recognition by ten percent. Furthermore, the slogan represents the concept of the insurance business and the corporate spirit and image of the insurance company.

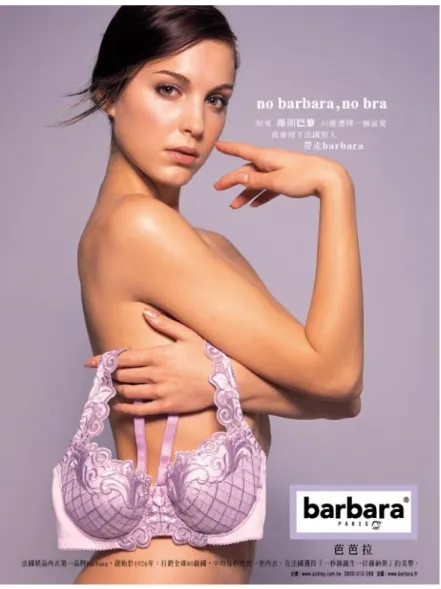

Figure 1. Rhyming and alliterative English slogan.

Source: Supplied by copywriter.

In advertising products of imported brands, rhyming and alliterative English slogans such as “no barbara, no bra” are employed to attract young Taiwanese women’s attention. In the advertisement (see Figure 1), the Chinese wording in the body copy reads: ruguo likai bali, zhineng xuanze

擇一個最愛,我會離開法國男人,帶走 barbara) [If I leave Paris with only one thing I cherish most, I will leave French men alone and take barbara.] In this print advertisement, the copywriter intends to use the rhyming and alliterative effect “no barbara, no bra” to convince consumers that if they love famous brands, barbara is the only brand of brassiere that they should wear. Hence, copywriters use the English rhyming slogan to deliver the above message to the intended audience, as well as convey the effect of authenticity in the advertised product, which is imported from Paris. The copywriter specifically said that if the Chinese transliteration of the English brand name barbara, babala (芭芭拉), was used in the slogan, it would sound unattractive and awkward. Therefore, the English slogan and the English brand name barbara, together with the word “Paris” shown in the signature line, are used to suggest authenticity in the advertised product.9

Bilingual mix copy of commercials. To attract the attention of young consumers, copywriters sometimes use code-mixed or monolingual English copy in TV commercials of international brands, to convey a sense of international youth culture, as in the following two examples.

The first example is a TV commercial shot by McDonald’s. Since the year of 2000, McDonald’s has been accused of providing junk food in the American market. To recreate its global image, McDonald’s has invited famous athletes to endorse its products in commercials implying that athletes who eat at McDonald’s are strong and healthy. The commercial provided by the copywriter portrays the daily activities of Taiwan’s 2004 Olympic gold medalist of taekwondo, Mr. Zhu, Mu-Yan, beginning with an English super “Gold medalist of 2004 Olympic Game” and the English voice-over “good morning.” Then a Chinese voice-over states that all of Mr. Zhu’s energy for what he does comes from what he eats, namely, healthy breakfasts of McDonald’s, such as ham and eggs, cheese burgers, and freshly baked bagels. While the Chinese narration continues, the English voice-over and the super “what I eat, what I do” are inserted twice. The whole shot closes with the English voice-over and the super “I’m loving it.” In this commercial, copywriters use the simple English expression “good morning”; the global

concept of McDonald’s advertising campaign “what I eat, what I do”; and McDonald’s global slogan “I’m loving it,” to attract the attention of the younger generation and recreate the global brand image of McDonald’s. On the other hand, they use the Chinese voice-over to convey Mr. Zhu’s product endorsement and testimonial to disseminate the main message of the TV commercial to the young audience.

The next TV commercial promotes a shampoo product of the Paris-based brand, mod’s hair. When mod’s hair was first introduced to Taiwan, copywriters used a variety of advertising copy in different media. For print advertisements, as discussed earlier in section Intrasentential

English lexical mixing copy, a code-mixed slogan, “youGozhi” (有 Go 直),

was created. For television commercials, copywriters wanted to give consumers an impression that the advertised product was purely an international brand imported from abroad, although it was manufactured in Taiwan. Therefore, in the promotional campaign of mod’s hair, unlike other international shampoo brands that had Chinese transliterated names, such as

lishi (麗仕) for Lux and duofen (多芬) for Dove, copywriters used only its

English brand name, without providing any Chinese name. In addition, to appeal to young people’s cultural taste for “mix and match,” models of mixed blood were recruited to pose for a runway show in the commercial. The commercial is narrated in monolingual English with Chinese subtitles. The copywriter creating this commercial asserted that by using the English brand name and the English voice-over, he intended to enhance the international image of the brand and make the young target audience feel that this brand was dynamic and lively.

All the examples presented in section Using English to Appeal to the

Trendy Taste of the Younger Generation illustrate how copywriters in Taiwan

use various types of English mixing in advertising copy to appeal to the younger generation. The resulting socio-psychological effect of English in advertising is also observed globally. In German advertising, Piller (2003) notes that “English is portrayed as the language of . . . the young, cosmopolitan business elite” (p. 176). In French advertising, Martin (1998)

observes that the younger audience, between seventeen and forty-five, is the primary target of advertisements using English, because they “are more likely to understand English” (p. 319). In Hungarian advertising, Anglicisms are considered to convey the notions of “cosmopolitanism” and “youthfulness” (Petery, 2011, p. 39).

Conclusion

The interviews conducted with copywriters indicate that English mixing in advertising in Taiwan is mainly used to feature a sense of internationalism and the trendy taste of the younger generation, accompanied by the effects of premium quality, authenticity, authority, and a metropolitan orientation, in products being advertised. In Ecuador, a copywriter makes a similar observation.

[English] . . . can give a sense of internationalism; something that is accepted abroad . . . a sense of being foreign . . . a sense of quality because we usually relate English with North American and European and, therefore, with quality, with well-made, with technology, with research, with design, with something that is good. (English translation quoted in Alm, 2003, p. 151)

Depending on product type, target audience, and requests made by clients, copywriters in Taiwan utilize various strategies of English mixing in print advertisements and TV commercials.

In highlighting internationalism in products of international brands, copywriters use different types of advertising copy, depending on whether clients request globalization or glocalization. Globalization requires the standardized use of monolingual English copy or slogans while glocalization involves local customization by means of either monolingual Chinese copy or Chinese-English code-mixed copy. The same observation is made in Russia, where English or a bilingual mix copy is used in advertising all products imported from abroad or manufactured by Western companies or

multinational companies located in Russia (Ustinova, 2006, p. 274).

To appeal to the younger generation, copywriters frequently mimic young people’s online language by using intrasentential lexical mixing and English slogans that convey a message of trendiness and fun. Piller (2001) observes that “fun orientation” (p. 163) is also one of the characteristics of the function of English in bilingual copy in German advertising.

While using English in bilingual advertising copy serves as “a brand image reinforcer, mood enhancer… ” (Martin, 1998, p. 336), copywriters develop two strategies to ensure that Chinese-English code-mixed advertising copy can be fully understood by the target audience. In promoting products featuring internationalism, English narration or dialogue is almost always accompanied by Chinese subtitles. In addition, Chinese supers and voice-overs are added to convey the factual information of the advertised products. In promoting products appealing to the younger generation, simple English vocabulary is used in slogans or intrasentential lexical mixing.

In conclusion, this paper, by means of interviews with copywriters, shows the rationale Taiwanese advertisers use to promote English-based bilingualism, including showing the reasons for the overwhelming choice in the non-Anglophone world to use English to name both products and companies (Bhatia, 2006, p. 606).

It is suggested that more investigation involving copywriters can be administered to explore the role of English in the underlying process of creating advertising copy by copywriters in various cultures.

In sum, though interviewing copywriters entails great difficulties, such interviews offer firsthand information as regards the motivations behind various copywriting styles during the advertisement creation process in Taiwan, which reveals the contemporary development of the influence of English in Taiwan.

Notes

1. According to Hsu (2012), in the discourse analysis of 1265 Chinese-English code-mixed advertisements, among the ten discourse

domains in which products are advertised most frequently in English mixing, residential real estate business is the only one localized in nature while all the others involve imports, fashion, or advanced technology. Therefore, real estate copywriters were singled out for interviews to probe their motivation in using English mixing in a localized business. 2. According to Sinha (2007), execution refers to “the physical form of an

idea—implemented as a TV or radio commercial, print advertisement, billboard, direct mailer or website”.

3. An insight, based on Sinha’s definition (2007), “connects different sets of associations that lead to a thought or solution that was not apparent before. It is about grasping the inner nature of things or actions, intuitively. Ads are intended to… create [consumers’] needs. The images, text, sounds that make up an ad are a reflection of what people dream of, what they want their lives to be like. They are projections of self. Most ads also have an overt message… this brand is good for you”.

4. According to Glossary of Cable Advertising Terms on Viamedia (http://cms.viamediatv.com/tabid/111/Default.aspx#S, September 30, 2012), super refers to “a method of super-imposing copy over the TV picture… usually include logos, store names, dates, prices, and other information important to an advertiser”.

5. Based on the definition given by Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (October 8th, 2012), voice-over refers to “the voice of an unseen narrator speaking (as in a motion picture or television commercial)”.

6. Ford used to provide bilingual names for its products. Since the change of its advertising strategy, products have only been named in English. 7. Jiazi Fitness Center went bankrupt and went out of business in 2006.

This local fitness center is cited in this paper only as an example of how a local brand uses English to foster internationalism in its advertised products.

8. As of October 10, 2012, this slogan has been extended to “We share, We link”.

phrase appearing in relatively small print immediately following the company name and logo (typically in the corner of an ad)” (p. 237).

Acknowledgement

This paper as part of a research project was funded by National Science Council of Republic of China (NSC90-2411-H-002-044). Acknowledgments are also extended to the following copywriters who have provided the content of the interviews and some of the data in this paper: Michael Dee, Executive Creative Director, J. Walter Thompson; Jian-Zhi Zhong, General Manager, MIT Seeds Plant; Murphy Chou, Executive Creative Director, Ogilvy & Mather Advertising; Minguay Yeh, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy & Mather Advertising; Vivian Chang, Executive Creative Director, United Advertising; Jin Yang, Creative Director, Leo Burnett Company Ltd.; Rae Wang, Executive Creative Director, Lowe; Jenny Kuo, Creative Director, Target Group Worldwide Partners Co., Ltd.; Rich Shiue, Executive Creative Director, JWT Taiwan.

References

Alm, C. O. (2003). English in the Ecuadorian commercial context. World

Englishes, 22(2), 143-158.

Baumgardner, R. J. (2008). The use of English in advertising in Mexican print media. Journal of Creative Communications, 3(1), 23-48.

Bhatia, T. K. (1992). Discourse functions and pragmatics of mixing: Advertising across cultures. World Englishes, 11(2), 195-215.

Bhatia, T. K. (2000). Advertising in rural India: Language, marketing

communication, and consumerism. Tokyo: Institute for the Study of

Languages and Cultures of Asia & Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. Bhatia, T. K. (2001). Language mixing in global advertising. In E. Thumboo

(Ed.), The three circles of English: Language specialists talk about the

English language (pp. 241-256). Singapore: UniPress.

Bhatia, T. K. (2006). World Englishes in gobal advertising. In B. B. Kachru, Y. Kachru, and C. Nelson (Eds.), The handbook of World Englishes (pp.

601-619). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Bhatia, T. K., & Ritchie, W. C. (2006). Bilingualism in the global media and advertising. In T. K. Bhatia and W. C. Ritchie (Eds.), The handbook of

bilingualism (pp. 512-546). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Blair, R. J. (1997). The role of English and other foreign languages in Japanese society. The Faculty Journal of Aichi Gakuin Junior College, 5, 74-86.

Bokamba, E. G. (1989). Are there syntactic constraints on code-mixing?

World Englishes, 8(3), 277-292.

Chen, W. Y. (2006). The mixing of English in magazine advertisements in Taiwan. World Englishes, 25(3/4), 467-478.

Dimova, S. (2012). English in Macedonian television commercials. World

Englishes, 31(1), 15-29.

Dumitrescu, L., & Vinerean, S. (2010). The glocal strategy of global brands.

Studies in Business and Economics, 5(3), 147-155.

Gao, L. (2005). Bilingual’s creativity in the use of English in China’s advertising. In J. Cohen, K. T. McAlister, K. Rolstad and J. MacSwan (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th international symposium on bilingualism

(pp. 827-837). Somervilee, MA: Casadilla Press.

Gerritsen, M., Korzilius, H., Van Meurs, F., & Gijsbers, I. (2000). English in Dutch commercials: Not understood and not appreciated. Journal of

Advertising Research, 40(4), 17-31.

Gerritsen, M., Nickerson, C., Van den Brandt, C., Crijns, R., Dominguez, N., & Van Meurs, F. (2007a). English in print advertising in Germany, Spain and the Netherlands: Frequency of occurrence, comprehensibility and the effect on corporate image. In G. Garzone and C. Ilie (Eds.), The role

of English in institutional and business settings: An intercultrual perspective (pp. 79-98). Berlin: Peter Lang.

Gerritsen, M., Nickerson, C., Van Hooft, A., Van Meurs, F., Nederstigt, U., Starren, M., & Crijns, R. (2007b). English in product advertisements in Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain. World Englishes,

Hamdan, J. M., & Abu Hatab, W. A. (2009). English in the Jordanian context.

World Englishes, 28(3), 394-405.

Hilgendorf, S. (2010). English and the global market: The language’s impact in the German business domain. In H. Kelly-Holmes and G. Mautner (Eds.), Language and the market. In S. Wright and H. Kelly-Holmes (Eds.), Language and globalization series. Palgrave-Macmillan.

Ho, J. W. Y. (2007). Code-mixing: Linguistic form and socio-cultural meaning. The International Journal of Language Society and Culture,

21.

Hornikx, J., & Starren, M. (2006). The relationship between the appreciation and the comprehension of French in Dutch advertisements. In R. Crijns & C. Burgers (Eds.), Werbestrategien in Theorie und Praxis:

Sprachliche Aspekte von deutschen und niederländischen Unternehmensdarstellungen und Werbekampagnen (pp. 129-145).

Tostedt: Attikon Verlag.

Hornikx, J., Van Meurs, F., & Boer, A. (2010). English or a local language in advertising. Journal of Business Communication, 47(2), 169-188. Hsu, J. L. (2008). Glocalization and English mixing in advertising in Taiwan:

Its discourse domains, linguistic patterns, cultural constraints, localized creativity, and socio-psychological effects. Journal of Creative

Communications, 3(2), 155-183. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, and

Singapore: Sage Publications.

Hsu, J. L. (2012). English mixing in residential real estate advertising in Taiwan: Socio-psychological effects and consumers’ attitudes. In J. S. Lee and A. Moody (Eds.), English in Asian popular culture (pp. 199-229). Hong Kong University Press.

Jain, S. C. (1989). Standardization of international marketing strategies: some research hypotheses. Journal of Marketing, 553, 10-79.

Jain, S. C. (1993). International marketing management. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Kachru, B. B. (1990). The alchemy of English: The spread, function, and

Krishna, A., & Ahluwalia, R. (2008). Language choice in advertising to bilinguals: Asymmetric effects for multinationals versus local firms.

Journal of Consumer Research, 35, 692-705.

Lee, J. S. (2006). Linguistic constructions of modernity: English mixing in Korean television commercials. Language in Society, 35, 59-91.

Leung, C. H. (2009). An empirical study on code mixing in print advertisements in Hong Kong. Asian Journal of Marketing, 1-13. Martin, E. (1998). Code-mixing and imaging of America in France: The

genre of advertising. Doctoral dissertation, Department of French,

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL., U.S.A.

Martin, E. (2002). Mixing English in French advertising. World Englishes,

21(3), 375-401.

Martin, E. (2007). “Frenglish” for sale: Multilingual discourses for addressing today’s global consumer. World Englishes, 26(2), 170-188. Martin, E. (2008). Language-mixing in French print advertising. Journal of

Creative Communications, 3(1), 49-76.

Mooij, M. de. (1994). Advertising worldwide. (2nd ed.). New York: Prentice Hall.

Muysken, P. (2000). Bilingual speech: A typology of code-mixing. Cambridge University Press.

Petery, D. (2011). English in Hungarian advertising. World Englishes, 30(1), 21-40.

Piller, I. (2001). Identity constructions in multilingual advertising. Language

in Society, 30(2), 153-186.

Piller, I. (2003). Advertising as a site of language contact. Annual Review of

Applied Linguistics, 23, 170-83.

Planken, B., Van Meurs, F., & Radlinska, A. (2010). The effects of the use of English in Polish product advertisements: Implications for English for business purposes. English for Specific Purposes, 29, 225-242.

Puntoni, S., Langhe, B. de., & Van Osselaer, S. M. J. (2008). Bilingualism and the emotional intensity of advertising language. Journal of

Ray N. M., Ryder, M. E., & Scott, S. V. (1991). Toward an understanding of the use of foreign words in print advertising. Journal of International

Consumer Marketing, 3(4), 69-98.

Sinha, K. (2004, July). Globalization and identity: Inferences from advertisements. Paper presented at the 10th World Englishes Conference,

Syracuse, U.S.A.

Sinha, K. (2007). Personal e-mail correspondence. September 28, 2007. Ustinova, P. I. (2006). English and emerging advertising in Russia. World

Englishes, 25(2), 267-277.

About the Author

Jia-Ling Hsu is an Associate Professor at Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at National Taiwan University. Her research interests are Sociolinguistics and TESL. For further information and discussion, please contact the author at jlhsu@ntu.edu.tw.