Contents lists available atScienceDirect

International Business Review

journal homepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/ibusrevAddressing the cross-boundary missing link between corporate political

activities and

firm competencies: The mediating role of institutional capital

Yu Gao

a, Zhuoer Yang

b,⁎, Kuo-Feng Huang

c, Shanxing Gao

d, Wei Yang

eaSchool of Economics and Finance, Xi’an Jiaotong University, 74 West Yanta Road, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710061, China bSchool of Management, Xi’an Jiaotong University, 28 West Xianning Road, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710049, China

cDepartment of Business Administration, National Chengchi University, No. 64, Sec. 2, Zhi-Nan Road, Wenshan, Taipei, 116, Taiwan dSchool of Management, Xi’an Jiaotong University, 28 West Xianning Road, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710049, China

eSchool of Automobile, Chang’an University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710049, China

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Corporate political activity Institutional capital Internal capability

A B S T R A C T

This study examines the mediating effect of institutional capital on the relationship between corporate political activities (CPA) andfirm competencies. By adopting an institutional perspective, we identify the influence of a firm’s relational CPA and participation CPA, and its two types of institutional capitals, formal institutional ca-pital (FIC) and informal institutional caca-pital (IIC), on thefirm’s competencies. Based on survey data from multi-informants in 303 Chinesefirms, our results suggest that firms’ institutional capital (IIC/FIC) partially/fully mediates the relationship between CPA andfirm competencies. The findings provide the evidence that how nonmarket strategy, such as corporate political activities, affects a firm’s institutional capital and then its competencies.

1. Introduction

To survive and thrive amid intense global competition, the way a firm utilises its political resources to achieve economic outcomes (Lawton, McGuire, & Rajwani, 2013, Lawton, Rajwani, & Doh, 2013; Rajwani & Liedong, 2015), known as corporate political activity (here-after CPA), is as important as its competencies in the market arena (Lux, Crook, & Woehr, 2011; Rajwani & Liedong, 2015). Previous research from multiple disciplines (e.g., political science and management) in-vestigates the conceptions (e.g.,Bonardi, Hillman, & Keim, 2005), the antecedents (e.g.,Lawton, McGuire et al., 2013; Lawton, Rajwani et al., 2013), and the outcomes (e.g., Huber & Kirchler, 2013) of CPA. No-tably, institutional contexts considerably influence firms’ selection of their political strategies and functional mechanisms (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015), and such influences become more salient in developing countries. With the ongoing transitioning processes in the emerging economies (e.g., China), the traditional conceptualisation and function mechanism of CPA in the Western markets would be modified due to the deviated local institutional contexts (Hoskisson, Shi, Yi, & Jin, 2013), while to date there are few studies‘explain the chan-ging nonmarket context within which companies operate (Sun, Mellahi, & Thun, 2010)’.

First, the validness, properness, and effectiveness of political

activity would be shaped by local political systems (Sun et al., 2010). In the Western markets, among the broad range of political resources (i.e., legitimacy resources (rights of participating in political and social af-fairs, public image, and social reputation), relational resources (re-lationships with government officials), financial resources (Bonardi et al., 2005; Hillman & Hitt, 1999; Hillman, Keim, & Schuler, 2004; Luo & Junkunc, 2008; Keim & Zeithaml, 1986)), extant literature fo-cuses exclusively on financial CPA (e.g., putting financial resources toward campaign contributions and/or lobbying activities (De Figueiredo & Silverman, 2006)) to answer the “what” questions re-garding the outcomes of CPA, but rarely considers other types of CPA and their differentiated outcomes (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015). Despite the long-have-been recognised free-riding (Lenway & Rehbein, 1991) and ethicality (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015) issues of financial CPA, China’s ‘complex and fluid’ institutional environment with unstable factor markets and an intricate legal framework (Peng, Sun, Pinkham, & Chen, 2009;Shu, Zhou, Xiao, & Gao, 2014) would greatly prohibit the usage of a certain type of CPA while escalate the im-portance of others. In particular, the national constitution prohibits the practice offinancial CPA whereas underdeveloped regulatory institu-tions and persistent traditional social norms increase the prevalence of participation CPA (i.e., using legitimacy resources to participate in political and public affairs (hereafter PCPA) (Deng, Tian, & Abrar, 2010;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.07.006

Received 21 June 2016; Received in revised form 7 June 2017; Accepted 26 July 2017

⁎Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses:joseph-gao@hotmail.com(Y. Gao),imyangzhuoer@hotmail.com(Z. Yang),kfhuang@nccu.edu.tw(K.-F. Huang),gaozn@mail.xjtu.edu.cn(S. Gao),

yw0725@126.com(W. Yang).

0969-5931/ © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Lawton, McGuire et al., 2013; Lawton, Rajwani et al., 2013; Luo & Junkunc, 2008; Oliver & Holzinger, 2008)) and relational CPA (i.e., using relational resources to cultivate and utilise political net-works (hereafter RCPA) (Deng et al., 2010; Luo & Junkunc, 2008; Peng & Luo 2000; Rajwani & Liedong, 2015).

Second, transitioning institutions and underdeveloped factor mar-kets also open the gate for addressing the missing link between afirm’s CPA in the non-market domain and afirm’s competency improvement in the market arena. Previously, the extant literature focuses primarily on how CPA directly affects firm performance (Lux et al., 2011; Rajwani & Liedong, 2015), treating the mechanisms involved in this relationship as a black box. Based on the institutional perspective, in-stitutional environments place constraints upon and offer opportunities forfirms (Oliver & Holzinger, 2008). Firms’ behaviours and strategies are largely restricted and shaped by the formal and informal institu-tional rules in their embedded instituinstitu-tional environment (North, 1990), andfirms who can conform to those institutional rules may be rewarded with benefits from the formal (e.g., government support) and the in-formal (e.g., relational network resources) actors in their embedded institutional environments (Gao, Gao, Zhou, & Huang, 2015;Shu et al., 2014). In China’s mid-range economy, firms are normally lacking the necessary resources (Shu et al., 2014) and access to the proper channels to acquire them (Gao et al., 2015). In this essence, CPA, as afirm’s activities to communicate with (Guo, Xu, & Jacobs, 2014) and bargain against (Oliver & Holzinger, 2008) regulators, and to participate in political (Luo & Junkunc, 2008) and social (Deng et al., 2010) affairs, are conceived to enablefirms to cope with and draw benefits from their institutional environments to maintain and create values (Baron, 1995; Bonardi et al., 2005; Oliver & Holzinger, 2008). This implies a potential mediating role offirms’ drawing benefits from their institutional sur-roundings (Gao et al., 2015; Shu et al., 2014) that bridges CPA (the conforming to and shaping of institutional rules (Lux et al., 2011)) with firm competencies in the market battlefield (Lu, Zhou, Bruton, & Li, 2010), which has yet been validated.

To address these research gaps, we apply institutional theory to interpret the mediating mechanism of institutional capital (Gao et al., 2015) in links between CPA (RCPA and PCPA) in the political domain andfirm competencies in the market arena in China. We focus on two types of institutional capital, namely, informal institutional capital (hereafter IIC), defined as a firm’s acquired resources, technical knowledge, market information, and managerial intelligence via rela-tional network with other business members (Gao et al., 2015), and formal institutional capital (hereafter FIC), defined as a firm’s obtained technical information, infrastructure and equipment, and tax conces-sions and subsidies from the government (Gao et al., 2015).

In today’s globalized economy, firms are facing with ever intensified market competitions. Past research has argued that firms’ skills and abilities to deploy and utilise various resources and know-how to de-velop innovative product (Afuah, 2002; Zhou & Wu, 2010), andfirms’ commercialization of proprietary innovations (Nevens, Summe, & Uttal, 1990;Li, Guo, Liu, & Li, 2008;Zahra & Nielsen, 2002) are the important competencies that enablefirms to successfully develop and launch new products, and establishing a competitive advantage (Nevens et al., 1990; Zahra & Nielsen, 2002). These competencies would be particu-larly important in China’s transitional economy where the ongoing in-stitutional transition and fast economic developments have left firms with vast underexplored market regime to conquer (Gao et al., 2015;Yi, Liu, He, & Li, 2012). In this consideration, we examine two types offirm competencies in the market place: technology capability (hereafter TC) is a firm’s ability to utilise various technologies (Afuah, 2002; Zhou & Wu, 2010), and technology commercialisation capability (hereafter TCC) is afirm’s technology transfer and value creation cap-ability in technological innovation (Li et al., 2008).

This research makes the following contributions. First, our discus-sions on RCPA and PCPA reveal the effective political activities in si-tuations where the political system, the economic infrastructure and

societal norms are drastically deviated from the traditional paradigm. The identification of the valid CPA types in China’s political environ-ment would add nuance to the CPA research about not only the ty-pology of CPA per se, but also the co-evolution of the CPA tyty-pology and the political environments (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015), which in turn, complete the map of the International Business (IB) (e.g.,Boubakri, Guehami, Mishra, & Saffar, 2012; De Villa, Rajwani, & Lawton, 2015; Hassan, Hassan, Mohamad, & Min, 2012;Puck, Rogers, & Mohr, 2013). More importantly, their differential effects on institutional capital (FIC and IIC) and firms’ different capabilities (TC and TCC) identify the ‘input of political resource—institutional/market outputs’ process with the norms of‘reciprocity’ and ‘legitimacy’ as the key drivers (Sun et al., 2010).

Second, we offer a possible interpretation (firms’ interaction with and benefit drawn from their institutional surroundings) regarding the black box betweenfirms’ political strategy in the political arena and firms’ competencies in the market battlefield. In this way, we join the discussions of institutional research and IB community in terms of teraction of the market and non-market power in a certain type of in-stitutional context which involved in a certain stage of inin-stitutional transition (De Villa et al., 2015;Shirodkar & Mohr, 2015).

Third, though the cross-sectional data we used may only reveal the ‘how firms acquire, integrate and sustain political and social resource (Frynas, Mellahi, & Pigman, 2006; Sun et al., 2010)’ in a short time window, their comparisons with the traditional paradigms in the de-veloped economies may also add to the exploration regard‘how non-market strategies evolve over the long term (Sun et al., 2010)’ in the process of institutional transition and thus contribute to the historian research in nonmarket research (e.g.Evans, 1997; Weiss 2000).

In addition, using China as the empirical setting, ourfindings about the valid types of political activities, and the causal links betweenfirms’ CPA in the non-market area and firms’ competencies in the market arena offer insights for the local firms to compete China’s market and non-market arena, for the foreignfirms that intend to enter Chinese market to learn China’s political environment and formulate their po-litical strategies, and for Chinese government to properly popo-litical system design in order to guidefirms and foster economic growth.

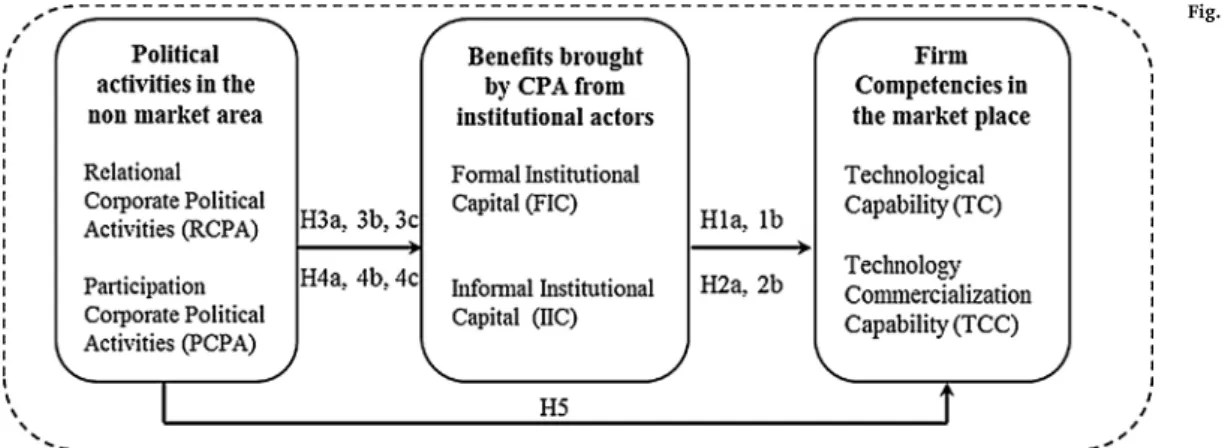

Overall, our study contributes to the interpretation offirms’ “‘in-tegrated’ strategy [political and market] that can confer sustained competitive advantage” (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015; p. 273), and bridges the CPA research in the non-market (e.g., political science, political economies) and market (e.g., resource based view)fields.Fig. 1shows our conceptual framework.

2. Theory and hypotheses development

2.1. Firm institutional capital andfirm competencies

Given China’s objective of becoming an “innovation-orientated so-ciety” by 2020, the central government has endeavored to prompt firms’ innovative activities (Gao et al., 2015). Along with the fast eco-nomic development pace,firms in China are facing with increasingly intensified market competition (Zhou & Wu, 2010), because of which firms’ capabilities to build and leverage different resources and tech-nologies to develop innovative product and launch them in the market better and faster than their competitors, namely their TC and TCC, are vital forfirms’ survive and thrive in facing with intensified market competition (Li et al., 2008; Zhou & Wu, 2010), and have yield in-creasingly strategic importance (Afuah, 2002; Nevens et al., 1990; Zahra & Nielsen, 2002). Specifically, TCC enables firms to explore consumer needs (Kollmer & Dowling, 2004) and acquire ideas with complementary knowledge, and realise their value by developing and manufacturing saleable products and selling them in a market (Mitchell & Singh, 1996). It thus increases afirm’s marketing compe-tency by improving speed and cost-efficiency of new product in-troduction (Chen, 2009; Zahra & Nielsen, 2002). TC enablesfirms to

understand (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) and utilise (Afuah, 2002) their knowledge stock in an effective manner and thus improve their tech-nological competencies in markets. Therefore, firms need to nurture their TC and TCC to achieve better market performance. TC relies on a firm’s stocked or acquired knowledge, experience, and resources for design, manufacturing, and technology development (Zhou & Wu, 2010), whereas TCC is a function of afirm’s marketing expertise and skills (Davenport, 2013), tangible resources such asfinancial resources and physical assets (Hill, Jones, Galvin, & Haidar, 2007), and intangible resources such as image, reputation, and legitimacy (Grant, 2002). It is a challenge for an individual firm to obtain all of the necessary re-sources to develop these two capabilities (Markman, Siegel, & Wright, 2008), which in turn necessitates resource acquisition from the external environment (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

According to institutional theory, a firm’s embedded institutional environment determines effective channels for its external resource, knowledge, and information acquisition (North, 1990;Oliver, 1997). In China’s transitional economy with considerable institutional voids (Peng, Wang, & Jiang, 2008), as suggested by Gao et al. (2015), un-derdeveloped formal institutions give rise to the complementary role of relational networks as one possible resource-renewing channel, while the considerable powers (e.g., resource control and allocation) that the government holds requirefirms to actively solicit resources, knowledge, and information from the government as another possible resource-re-newing channel. In this way, FIC and IIC, as the outcomes of these two channels for resource renewing, are vital for firms to nurture their competencies in markets.

As for TC, IIC offers firms the complementary knowledge and assets, such as technical know-how and expertise, and best current industry practices (Park & Luo, 2001) from the same or similar industries, and increases firms’ knowledge bank and technological expertise (Peng & Luo, 2000;Sheng, Zhou, & Li, 2011). FIC, on the other hand, provides firms with financial support and favorable policies (Li & Atuahene-Gima, 2001; Lu et al., 2010) to buffer pressures from market competition (Luo, 2003) and facilitate investment in R & D (Gao et al., 2015). Moreover, technological devices, scientific knowledge, and experiences from public research institutions derived from FIC also improvefirms’ current knowledge stocks (Gao et al., 2015).

As for TCC, IIC providesfirms with information about changes in their customers’ needs, advancements in technologies, and competitor movements (Park & Luo, 2001), which helpfirms get acquainted with market conditions and introduce new products to address the market demands (Peng & Luo, 2000; Sheng et al., 2011). FIC, on the other hand, provides firms with information about upcoming policies and regulations (Lu et al., 2010), which enables firms to sense coming changes in the macro- and industrial environments (Chen & Wu, 2011). As a result, FIC can helpfirms achieve better recognition and proper reaction to the market opportunities that are embedded in the transi-tions of institutional environments (Teece, 2007), which in turn

enhancesfirms’ TCC. Thus:

Hypothesis 1a. IIC has a positive effect on TC. Hypothesis 1b. FIC has a positive effect on TC. Hypothesis 2a. IIC has a positive effect on TCC. Hypothesis 2b. FIC has a positive effect on TCC. 2.2. CPA andfirm institutional capital

The accessibility of FIC and IIC is unevenly distributed acrossfirms with different institutional positions (Luo & Junkunc, 2008). Only those firms recognised as legitimised or powerful members by their institu-tional surroundings have the privilege to acquire FIC and IIC (Guo et al., 2012; Suchman, 1995; Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002). For instance, asDixit (1998) indicates, the government is not necessarily socially efficient, but rather serves the interests of powerful institutional actors andfirms that are more likely to comply with, shape or create institu-tional rules, and are thus viewed as desirable recipients of government grants.Park and Luo (2001)further add that major business players may be more inclined to conduct business with those who are capable of “getting things done” (p. 460). Thus, firms’ compliance with (Deephouse & Carter, 2005) and shaping of (Guo et al., 2012) the reg-ulatory rules and social norms are vital to prove their legitimacy (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015; Shu et al., 2014). In this situation, RCPA and PCPA may signal compliance with institutional norms or the influential power to alter the regulatory institutions, and thus acquire FIC and IIC for the following reasons.

With respect to RCPA, through relational communication with governmental officials, firms are able to get information on, under-stand, and manage ongoing or approaching regulations (Peng & Luo, 2000), which improves compliance with regulatory institutions and increases firms’ chances of being viewed as the preferred targets of government backing (Guo et al., 2012). Second, government officials are inclined to grant favors to their friends rather than strangers (Shi, Markóczy, & Stan, 2013), which means that political networking may facilitatefirms’ access to resources that are controlled by people they know in government (Peng & Luo, 2000).

As for IIC, RCPA signalsfirms’ conformity to relational norms in informal institutions (Tost, 2011; Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002), which leads other members infirms’ embedded institutional environment to perceivefirms as legitimised actors (Tost, 2011), and to recognise and approve firms’ positions in their embedded relational networks (Park & Luo, 2001). Firms thus enjoy better communication with and benefits from them. Second, a firm’s RCPA empowers it to “get things done” (Park & Luo, 2001). For instance,firms can persuade the gov-ernment to sustain current regulations to protect their current market interests or block the use of substitute resources to raise rivals’ costs ((Oliver & Holzinger, 2008), and provide new entry permissions for

firms entering the underdeveloped market (Peng & Luo, 2000). Such influence is recognised by peripheral firms’ institutional surroundings, appeals to the cooperative intention of benefit sharing (Park & Luo, 2001) or bridging (Burt, 1990) means, and compels them to yield to demands of thefirms (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015).

Though RCPA have the potential to facilitatefirms to acquire both FIC and IIC (Shirodkar & Mohr, 2015), due to the relational approach it takes, the individual effects of RCPA on FIC and IIC differ. Being con-ducted via the relational approach, RCPA denotes firms’ compliance with relational norms, which are in accordance with prevailing norms of informal institutions (i.e., social norms) while deviating from rules of formal institutions (i.e., regulations, laws). In this situation, politicians may be conservative in grantingfirms due to cognitive conflicts (rules of formal institutions vs. norms of informal institutions) and ethical concerns (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015), whereas members of a firm’s business network would be more inclined to provide benefits to the firm due to 1) the“right” norms that the firm follows (Tost, 2011) and 2) the “benefit sharing” and “bridging” intentions that compel them to yield to the demands of politically connectedfirms (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015). Therefore, IIC may be more explicitly facilitated by RCPA than FIC. Hypothesis 3a. RCPA has a positive effect on FIC.

Hypothesis 3b. RCPA has a positive effect on IIC.

Hypothesis 3c. The positive effect of RCPA on IIC is greater than its effect on FIC.

PCPA is afirm’s participation in the political, public, and industrial policy-amending process, and the consequent building and enhancing of its social reputation and image (Deng et al., 2010; Luo & Junkunc, 2008; Oliver & Holzinger, 2008). Thus, it enablesfirms to express their opinions in the policy-amending process to acquire individual or col-lective benefits and increase their control and autonomy (Getz, 1991) by stopping unwanted regulations (Wöcke & Moodley, 2015; Yoffie, 1987). In this way, PCPA signals the power offirms to shape regulatory institutions, which make it easier for them to be recognised and eval-uated as powerful actors by government officials and business actors, and consequently obtain FIC and IIC. Second, PCPA increases afirm’s social exposure to advance its public presence (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) and social reputation (Deng et al., 2010). Therefore,firms that practice PCPA will gain more recognition from government officials and business actors, and thus more opportunities to obtain FIC and IIC. For government officials, a firm’s social reputation signals its appropriate-ness for regulatory support (Deng et al., 2010; Luo & Junkunc, 2008). For business actors, their increasing recognition and awareness of the firm may trigger improved communication and cooperation intentions with thefirm (Burt, 1990).

Because PCPA is conducted by following a formal procedure, its individual effects on FIC and IIC differ. PCPA denotes a firm’s com-pliance with the regulatory rules of formal institutions, which is in accordance with prevailing norms in the political system embedded by government officials, and is transparent and does not cause ethnical concerns. Thus, government officials would be more inclined to re-cognise and value the focalfirms and grant support to them. Moreover, although it is the case that the desirable institutional position and in-fluence that PCPA signals to business actors may attract their co-operation and communication intentions, such merits also give rise to 1) competitive intentions of other firms toward the focal firms and cognitive conflicts (rules of formal institutions vs. norms of informal institutions) that constrain the relational benefits they may provide, and 2) selection constraints and costs forfirms because they must be careful in selecting relational partners and business contacts to main-tain their social reputation, which may reduce the degree of freedom to seek IIC and increase cooperation costs. Thus, PCPA may have a more explicit significance on the acquisition of FIC than IIC.

Hypothesis 4a. PCPA has a positive effect on FIC.

Hypothesis 4b. PCPA has a positive effect on IIC.

Hypothesis 4c. The positive effect of PCPA on FIC is greater than on IIC.

2.3. Firm CPA,firm institutional capital, and firm competencies

Institutional environment defines the channel through which firms can acquire resources from external environments (Gao et al., 2015) while the accessibility to this channel depends on the extent to which firms can take an advantageous institutional position by conforming to institutional norms and rules (Suchman, 1995). However, in China’s transitional economy with considerable institutional voids (Gao et al., 2015),firms lack the legitimacy to obtain such privilege (Guo et al., 2012), as underdeveloped and transitioning institutions make it more difficult for firms to understand their institutional environments (Guo et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2009) and comply with the complex andfluid institutional rules and norms (Peng et al., 2009). Therefore,firms have tofind effective ways to learn the institutional rules and strengthen their institutional positions (Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002).

In this situation, RCPA comprisesfirms’ activities in communicating with (Guo et al., 2012) and bargaining against (Oliver & Holzinger, 2008) the politicians who are empowered to formulate policies via the relational approach (Peng & Luo, 2000). It thus signals firms’ com-pliance with relational norms of informal institutions (Connelly, Certo, Ireland, & Reutzel, 2011;Tost, 2011), while its outcomes (e.g., in flu-ence on the political actors) signalfirms’ power over regulatory actors (Shi et al., 2013). PCPA comprisesfirms’ activities in participating in the policy-amending process (Luo & Junkunc, 2008) and social affairs (Deng et al., 2010) by following formal rules that are legitimised by the regulatory institution. The formal procedure thus signalsfirms’ com-pliance with the regulatory norms of formal institutions (Connelly, Certo, Ireland, & Reutzel, 2011;Tost, 2011), while its outcomes (e.g., policy shaping (Weidenbaum, 1980)) signalfirms’ power to alter the regulatory environment. In this way, RCPA and PCPA may enable the focalfirm to be recognised by other members (e.g., government and business actors) as a legitimised or powerful actor in the institutional environment (Tost, 2011). As a result,firms are entitled as legitimised or powerful actors (Guo et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2013; Tost, 2011), and thus have more opportunities in the institutional environment (Oliver & Holzinger, 2008) to acquire institutional capital through re-lational (Guo et al., 2010) and regulatory (Lu et al., 2010) means to improve their competencies in market places.

Hypothesis 5. Afirm’s institutional capital (FIC and IIC) mediates the relationships between its utilisation of its political resources (RCPA and PCPA) and its competencies in the market (TC and TCC).

3. Method

3.1. Sampling and data collection

As suggested byRajwani and Liedong (2015),‘surveys are used less in CPA empirical studies.… Future researchers could use more of these survey techniques in ways that allow for novel constructs to be devel-oped at a multi-level (p.281)’. Thus, following the empirical research of CPA in China that suggested byRajwani and Liedong (2015), we used a firm-level data that was collected through a survey conducted in China. We used the translation and back-translation method to create Chinese versions of the measures and maintain cross-cultural equivalence. To ensure the content and face validity of the measures and clarity in the Chinese context, we conducted a pilot test via personal interviews with senior managers from 10 firms. In particular, we asked these re-spondents not only to answer all the questionnaire items but also to provide feedbacks about the design, wording, clarity, and appro-priateness of the survey. Based on the results of the pilot test, we further

refined and finalised the questionnaire.

As China has several geographical segments that involved in dif-ferent stages of economic developments, we used a stratified sampling procedure. First, we divided all 31 provinces and municipalities in mainland China into three isometric groups (i.e., the eastern and costal region, the middle region, and the western region) according to their geographic locations and marketisation rankings (Shu et al., 2014) to reflect the entire landscape of China and decrease the potential for economic development bias. For each group, we randomly selected 500 firms that conduct innovation activities from industry directories or official statistics to form our sampling frame, making totally 1500 firms being selected. Thefirm list and contact information were provided by local governments and administrative bureaus. Second, we employed professional interviewers to make appointments (via phone calls) with firm executives, and informed them about the academic research pur-pose and confidentiality. We offered a token gift (a pen bearing the logo of the university) and a summary report in return for their participa-tion. Third, in 2011, two identical questionnaires (in paper format or electronic format) were distributed to eachfirm, for a total 1500 pairs distributed. Specifically, we sent the professional interviewers to firms to conduct face-to-face interviews with firm executives using the structured questionnaire, and offered respondents the opportunity to ask for clarifications of the questions about the questionnaire. For those respondents who agreed to participate but prefer to complete the questionnaires in the electronic format, we provided assistances via phone calls if they have any questions about the questionnaire. Using this method in research on emerging economies is more likely to gen-erate valid information (Zhou, Yim, & Tse, 2005). The sampledfirms were mainly in machinery manufacturing, chemicals, automobile, electronics and information technology, and other industries that have intense involvements in R & D and innovation activities, and covered various ownership structures (e.g., SOEs, POEs, joint ventures, Sino-foreign joint ventures, and FIEs).

A total of 490 pairs of questionnaires (286 paper questionnaires and 204 electronic ones (for those respondents who agree to participate but prefer to complete the electronic questionnaires)) were collected. After eliminating those responses with excessive missing data, we were left with 303 pairs of questionnaires (191 paper questionnaires and 112 electronic ones). The response rate was 20.2% (303/1500). For each firm, we collected two questionnaires: questionnaire A was from chief executive officers/top management teams (TMTs), and questionnaire B was from at least middle-level managers (including TMTs and depart-ment heads). Respondents of questionnaire A averaged 8.31 years of tenure and respondents of questionnaire B averaged 7.29 years of te-nure, exceeding thefive-year time frame for measuring the dependent, mediation, and independent variables, which ensured that respondents were knowledgeable and did possess accurate information concerning theirfirms’ innovation related- and CPA practices. An interrater relia-bility check indicated that the two questionnaires revealed similar views on the key descriptions (e.g., firm competitive position). Moreover, we compared the responses of these two sets of participants with the variables used in this study, and the t-tests yield no significant differences. Among the respondents, 9.41% were CEOs/chairmen, 37.95% were from top management teams, 38.45% were middle managers, and other 14.19% of respondent are the ones that were po-sitioned as at least middle-level managers, but didn’t provide answers for the questions about their job positions. Overall, the final sample covered 303firms in 23 provinces in China, among which 21.10% were large firms (with more than 2000 employees), 29.10% middle-sized firms (with between 300 and 2000 employees), and 39.80% small firms (with under 300 employees); 38.61% were state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and the rest were non-SOEs.

Thefinal dataset was selected in the way that: we randomly selected 150 samplefirms in which the independent variables (IVs) and med-iators were measured using data from questionnaire A, and the de-pendent variables (DVs) were measured via data from questionnaire B.

In the other 153firms the IVs and mediators were measured according to data from questionnaire B and the DVs were measured with data from questionnaire A to minimise common method variances (CMV) (Van Bruggen, Lilien, & Kacker, 2002).

To test the non-response bias in stage one and stage two, we con-ducted t-tests to compare participatingfirms versus non-participating firms in terms of firm age, firm size, and sales growth (Armstrong & Overton, 1977). The results of the tests indicated that there were no statistically significant differences among the firms (p < 0.05), suggesting that there was no non-response bias in our study.

3.2. Measures

The constructs were measured using multi-item scales. Each of the items used a Likert-scale response format ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”) as presented inAppendix A. 3.2.1. Independent variables (IV)

The measure of RCPA was adopted from previous studies (Guo et al., 2012; Peng & Luo, 2000; Rajwani & Liedong, 2015). A three-item con-struct was used to capture the extent to whichfirms cultivate and utilise their interpersonal relationships with government officials and bu-reaucratic officials. The construct of PCPA was measured based on a firm’s participation in political and social affairs, and its social re-putation and image building activities (Deng et al., 2010; Luo & Junkunc, 2008).

3.2.2. Mediator variables

We followed previous studies in measuring FIC (Gao et al., 2015; Li & Atuahene-Gima, 2001; Lu et al., 2010) with items evaluating technical knowledge and information,financial support and favorable policies, and licenses and equipment formally granted by the govern-ment. We measured IIC by evaluating the resources and knowledge that the samplefirms acquired via their relational business networks (Gao, Xu, & Yang, 2008;Gao et al., 2015;Xu, Huang, & Gao, 2012). 3.2.3. Dependent variables (DV)

We measured afirm’s technology capability (TC) with four items that assessed afirm’s ability to use various technologies (Zhou & Wu, 2010). We measured a firm’s technology commercialisation capability (TCC) based on the suggestions ofLi et al. (2008)with a four-item measure to reflect a firm’s technology transfer and value creation process in tech-nological innovation.

4. Analysis and results

We used SEM for the empirical test. We followed the two-stage procedure (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). In thefirst step, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the validity of the mea-surement model and the discriminant validity of individual constructs. Based on these valid measures, in the second step, structural models were used to estimate the path coefficients and to test the relationships between constructs, and to determine whether the model represented the bestfit between hypothesised relationships.Table 1summarises the descriptive statistics, correlations, and average variance extracted (AVE) values for each latent variable in this study. We followed Fornell and Larcker (1981) to compare the variance shared between the con-structs with the AVE. The square roots of the AVE of these variables were greater than each of the off-diagonal elements in the corre-sponding rows and columns, indicated adequate discriminant validity of our measures. Furthermore, as shown inTable 1, the mean values of our focal constructs all exceed the average level (3.5), indicated the generalizability and intensiveness offirms’ involvements in corporate political activities and technology-related activities, and their accu-mulation of institutional capital.

4.1. Construct validity and reliability

Wefirst conducted a CFA to determine the unidimensionality, dand convergent validity of the variables (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993). We examined a six-factor model in which the indicators of the six variables were loaded distinctively according to their hypothesised relationships (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). This measurement model revealed an adequate fit with the data (χ2 = 399.5, df = 223, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.910, CFI = 0.968, RMR = 0.067, RMSEA = 0.051, AIC = 603.538, see Table 2). In the six-factor model, our measures possessed convergent validity because all of the items were significantly loaded on their respective latent variables (the smallest critical value is 5.194 with p-value = 0.000). The construct reliability (Cronbach’s alpha exceeded 0.860 (seeAppendix A)) suggested that these measures had good internal consistency.

For the common method variance (CMV), we adopted the multi-informant procedural method to mitigate the potential influences of CMV, and also used three other techniques to mitigate and assess it. First, we examined the effects of adding one latent CMV variable to our hypothesised six-factor measurement model (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). The results indicated a betterfit compared to the six-factor model, and variance extracted by the CMV variable was 0.132, with below the cut-off value of 0.500, suggesting that the pre-sence of a latent factor represented the manifest indicator (Hair et al., 1998). Second, we conducted the Harman’s single-factor test using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) without rotation (Podsakoff et al.,

2003) to check the factor structure of the variables. The results revealed that six factors emerged with eigenvalues greater than 1 and the total variance explained by these six factors was 75.97%. Hence, no over-whelming factor occurred. Third, we applied the marker variable (MV) method by including a marker variable within the model (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). We took respondents’ position as the marker variable. The marker variable was not significantly related to most of the variables, and the hypothesised significant correlations between the constructs remained significant with control of the marker variable effect. On the whole, CMV was not a serious concern in our research. 4.2. Hypotheses testing and results

We tested the structural model including all hypothetical paths connecting the IVs, mediator variables, and DVs (Model 2). We also tested structural models that estimated the relationships between the IVs and DVs (Model 3), the IVs and mediator variables (Model 4), the mediator variables and DVs (Model 5) as shown inTable 2. We used the results of the structural models in Model 2 (other model results as ad-ditional supports) to test our hypotheses (seeTable 3).

As shown inTable 3, the significant paths (IIC to TC (β = 0.474, p < 0.001), FIC to TC (β = 0.160, p < 0.05), IIC to TCC (β = 0.239, p < 0.001), FIC to TCC (β = 0.181, p < 0.001)) (Model 2) support H1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b. The significant paths (RCPA to FIC (β= 0.150, p < 0.01), RCPA to IIC (β = 0.430, p < 0.001), PCPA to FIC (β = 0.505, p < 0.001), RCPA to IIC (β = 0.224, p < 0.001)) (Model 2) support H3a, 3b, 4a, and 4b.

For H3c and H4c, we used a structural model comparison to assess whether RCPA and PCPA influence FIC and IIC differently by setting the coefficients (RCPA-IIC and RCPA-FIC; PCPA-IIC and PCPA-FIC) to be equal and then conducting chi-square difference test. The coefficients between RCPA and IIC, PCPA and FIC were significantly higher than the ones between RCPA and FIC, PCPA and IIC (p < 0.001). Therefore, H1c and 2c are supported.

We followed the procedure inBaron and Kenny (1986)to examine the mediation effects in H5: 1). The IV should have a significant effect on DV (see Model 3); 2). The IV should have a significant effect on the mediator (see Model 4); 3). The mediator should have a significant effect on DV (see Model 5); and 4) when the mediator enters the step 1 model, partial mediation is supported if the significance level of the effect from the IV on DV decreases substantially; while full mediation requires the originally significant influence of the IV on DV to become insignificant (see Model 2). Together, the results from these four models show the indirect effects of RCPA and PCPA via FIC and IIC on TC and TCC. First, the results from Model 3, Model 4, and Model 5 satisfied condition 1, 2, and 3 of Baron and Kenny’s procedure. Second, the re-sults from Model 5 showed that when the effects of two mediators (FIC and IIC) were considered in the structural model, the originally nificant relationships between RCPA and TC/TCC became less sig-nificant (β = 0.433, p < 0.001 to β = 0.189, p < 0.01; β = 0.254, p < 0.001 to β = 0.125, p < 0.05), and the originally significant relationships between PCPA and TC/TCC became non-significant (β=0.166, p < 0.01 to β = 0.001, p > 0.1; β = 0.156, p < 0.001 toβ = 0.004, p > 0.1). We also used a series of Sobel’s tests to further test the significance of the above mediation effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The significant mediation paths consisted of a parsimonious structural model (Model 1) that fitted the data well (see Table 2). Specifically, the IIC and FIC fully mediated the relationships between PCPA and TC and TCC, and partially mediated the relationships be-tween RCPA and TC and TCC.

5. Discussion

This study examines whether and how RCPA and PCPA in the non-market domain can indirectly affect firm competencies in the market arena through FIC and IIC as the consequence offirms’ interaction with Table 1

Correlations, Means, Standard Deviations, and Average Variance Extracted.

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1. RCPA 0.917 0.364** 0.382** 0.519** 0.446** 0.393** 0.007 2. PCPA 0.368** 0.810 0.547** 0.402** 0.240** 0.316** 0.112 3. FIC 0.386** 0.550** 0.880 0.427** 0.336** 0.381** 0.081 4. IIC 0.522** 0.406** 0.431** 0.852 0.548** 0.489** 0.085 5. TC 0.450** 0.245** 0.341** 0.551** 0.882 0.566** 0.117* 6. TCC 0.397** 0.321** 0.385** 0.493** 0.569** 0.864 0.021 7. MV M 5.324 4.361 4.653 4.830 4.878 4.808 4.337 SD 0.945 1.339 1.162 0.928 0.390 0.850 0.813 Notes: N = 303.

Diagonal elements (in bold) are square roots of the AVE (average variance extracted) values.

Off-diagonal elements are the correlations of the variables; the adjusted correlations for potential common method variance (Lindell & Whitney 2001) are above the diagonal.

* p < 0.050. ** p < 0.010.

Table 2

Measurement and Structural Models.

Models χ2 df GFI CFI RMR RMSEA AIC

Measurement models One-factor model 1838.5 238 0.665 0.543 0.152 0.149 2012.501 Six-factor model (Saturated model) 399.5 223 0.910 0.968 0.067 0.051 603.538

Six-factor with one common variable model 310.6 198 0.929 0.980 0.050 0.043 564.574 Structural models Fully mediated model (Model2) 387.8 220 0.914 0.970 0.068 0.050 597.835 Parsimonious structural model (Model 1) 387.8 222 0.913 0.970 0.068 0.050 593.841 IV→ DV (Model 3) 164.3 78 0.939 0.974 0.068 0.061 280.285 IV→ M (Model 4) 173.7 93 0.940 0.978 0.074 0.054 293.732 M→ DV (Model 5) 192.4 92 0.936 0.973 0.187 0.060 314.416

their institutional environments. The results provide strong support for our predictions and generate important theoretical and managerial implications.

5.1. Theoretical contributions

AsOliver and Holzinger (2008)proposed, CPA is afirm’s source of competitive advantage, in that it enablesfirms to cope with and draw benefits from their institutional environments to maintain and create values. Studies adopting resource-based logic depict how CPA, as afirm’s use of their political resources to obtain political outcomes (e.g., votes, favorable policies, government purchase), may lead to positive firm performance (e.g., market share, profitability) (e.g., Dahan, 2005; Oliver & Holzinger, 2008), but fails to consider how a firm’s institu-tional contexts are intertwined with this advantage generating process (Lawton et al., 2012; Rajwani & Liedong, 2015). Studies from the in-stitutional perspective delineate howfirms utilise their political resources to cope with the constraints from their institutional environments, especially the regulatory political system (e.g.,Baron, 1995; Hillman & Hitt, 1999; Hillman, Zardkoohi, & Bierman, 1999), but neglects to address how CPA enablesfirms to draw benefits from such activities. Just asRajwani and Liedong (2015)indicated, previous research “is biased about an-swering the ‘what’ but not the ‘how’ questions with respect to the outcomes of CPA” (p. 280).

In this consideration, our primary contribution is to offer a rela-tively interpretive framework to address the link between CPA in the non-market domain andfirm competencies in the market battlefield. In particular, institutional environments place constraints upon and offer opportunities forfirms, thereby firms’ CPA becomes the source of their competitive advantage that enablesfirms to deal with the institutional constraints and to benefit from the institutional opportunities. Therefore, our integrative framework offers a more comprehensive understanding of CPA in terms of its legitimacy-gaining functions (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015), and provides a possible way to bridgefirms’ political activities with market competencies. Based on our primary contribution, this study further adds knowledge to institutional theory and complements the current understanding in the CPA literature.

First, based on the political resources utilised by firms, we cate-gorise the various types of CPA in practice. In particular, our in-vestigation of RCPA and PCPA explains the possible political activities, in addition tofinancial CPA, in China’s mid-range economy, in which

political transparency is low andfinancial CPA is limited (e.g., in Asia and Africa) (Lawton et al., 2012) or prohibited (e.g., in China) and the reciprocity norms would function as the main logic in terms of the in-vest-and-payback logic in the political domain, and complete the map about the co-evolution of CPA typology and political environments in the IB community. More importantly, as shown inTable 3, RCPA has a greater effect on IIC while PCPA is more effective at increasing FIC. These results suggest the various effects of CPA on the different types of institutional capitals and support the notion that RCPA draws attention from the connectors in afirm’s business relational network, while PCPA is more easily acknowledged and valued in the context of formal reg-ulatory surroundings. Our examination of the differentiated effects of RCPA and PCPA on FIC and IIC thus sheds light on and draws attention to the exploration of heterogeneities of CPA in terms of its political resources and relative outcomes.

Second, considering thatfirms in China generally lack awareness of the importance and functions of their political activities (Deng et al., 2010), in contrast to previous studies in whichfirms’ CPA is roughly linked with financial or politic outcomes (Ahlstrom, Bruton, & Yeh, 2008;Bonardi et al., 2005; De Figueiredo & Silverman, 2006; Epstein, 1969), this research unravels the indirect effects of CPA on firm com-petencies in the market via the improvements of their institutional capital. In this way, we address the missing link between afirm’s CPA and a firm’s competency building via the mechanism of legitimacy gaining by using the relatively intermediate results as the outcome variables to address the missing link between CPA and the outcome variables, and to provide an interpretative explanation for the“how” question in the CPA literature by expounding the benefits of CPA rather than the direct political outcomes or distant performance outcomes. In illuminating the approaches through which RCPA and PCPA lead to competitive advantages forfirms, we shed light on the politically re-lated business practices in China, contribute to the contextual knowl-edge in CPA literature, and further join the discussions about the in-teraction of the political and market powers across different types of institutional environments in the institutional research and IBfiled.

As for institutional theory, we not only demonstrate the notion that “institutions matter,” but also explain “how institutions matter.” The formal regulatory institutions and informal relational institutions sup-port possible channels (e.g., IIC and FIC) forfirms to obtain resources from their institutional surroundings (North, 1990), and set the rules to define appropriate activities (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). By complying Table 3

Results for Hypotheses Testing.

Hypotheses Path Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Sobel tests Model comparisons Results Estimates Estimates Estimates Estimates Estimates

H3a RCPA→ FIC 0.150** 0.150** 0.161** Support

H3b RCPA→ IIC 0.430*** 0.430*** 0.419*** Support

H3c RCPA→ IIC > RCPA → FIC p < 0.001 (M1,M2,M4) Support

H4a PCPA→ FIC 0.505*** 0.505*** 0.498*** Support

H4b PCPA→ IIC 0.224*** 0.224*** 0.215*** Support

H4c PCPA→ FIC > PCPA → IIC p < 0.001 (M1,M2,M4) Support

H1a IIC→ TC 0.474*** 0.474*** 0.621*** Support

H1b FIC→ TC 0.160* 0.159* 0.162** Support

H2a IIC→ TCC 0.239*** 0.238*** 0.316*** Support

H2b FIC→ TCC 0.181*** 0.178** 0.188*** Support

RCPA→ TC 0.189** 0.189** 0.433***

RCPA→ TCC 0.125* 0.125* 0.254***

PCPA→ TC 0.001 0.166**

PCPA→ TCC 0.004 0.156***

H5 RCPA→ IIC → TC 4.671*** Support

RCPA→ IIC → TCC 3.682*** RCPA→ FIC → TC 1.783* RCPA→ FIC → TCC 2.143* PCPA→ IIC → TC 3.559*** PCPA→ IIC → TCC 3.059** PCPA→ FIC → TC 2.338** PCPA→ FIC → TCC 3.409***

with and shaping institutional rules (e.g., RCPA and PCPA),firms de-monstrate their legitimacy to be accepted by their institutional sur-roundings and obtain benefits to foster their competencies (e.g., TC and TCC). Thus, our theoretical arguments and empirical results help to interpret why “institutions matter” to firms by depicting both the constraints (the institutional rules) and the opportunities (the rewards whenfirms can cope with those rules) that the institutions may impose onfirms.

5.2. Managerial implications

Our study provides important implications for managers.

First, managers should not limit the scope of the benefits of CPA to the political domain. Our results suggest that besides the favorable policies in the politicalfield that CPA can create, firm competencies in the market can also be nurtured via such activities. Therefore, managers should alter their attitude of conducting CPA by viewing it as a way for the“combination of both market and political strategies … that can confer sustained competitive advantage” (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015; p. 273) and exploring the potential of their various political resources. This is particularly important for firms that operate in the emerging economies in whichfinancial CPA is prohibited due to the less-trans-parent political system (Rajwani & Liedong, 2015). RCPA and PCPA may enable firms to prove their legitimacy and power, and facilitate their resource-renewing potential. For instance, in China,firms can act as state-linked or behave with a strong sense of social responsibility (e.g., providing employment, introducing new technology) as expected by the government society (Ahlstrom et al., 2008; Tsang, 1998) for the sake of establishing a mutually beneficial relationship with the gov-ernment and social actors. Wahaha, a famous Chinese beverage pro-ducer, successfully took over and operated a major state-owned factory to echo the political and social call for acquisitions of ailing state-owned enterprises, through which the company has earned nationwide re-cognition and a considerable social reputation, in addition to significant institutional capital (Sull, 2005). The New Hope Group, a large private animal feed and food processor in China, also took over a number of troubled statefirms in poorer regions and received extensive favorable media coverage and built up its reputation with local governments and markets (Ahlstrom et al., 2008).

Second, managers should be aware of the differentiated effects of RCPA and PCPA. Our results suggest that RCPA is more suitable for enhancing firms’ institutional positions in their business relational networks as it facilitatesfirms’ acquisition of IIC, while PCPA would be more useful in improving their status among the regulatory actors, and fuel their chances of obtaining FIC. For instance, as for RCPA, in 1993, ZTE pioneered a new management team structure in which technical experts, professional managers, and local government officials coexist as outside directors. Based on this attempt, ZTE guarantees a close re-lationship with the government to earn the privilege to enjoy a priority in bidding for government procurement projects, and escalates its po-sition in the business community by participating in the formulation of the telecommunications industry standards. As for PCPA, Liu Yonghao

(the board chairman of New Hope) participated in symposiums on the development of privatefirms held by the Chinese prime minister in Sichuan province in August 2004. He made three proposals (an increase in government support, government consideration, and loans for pri-vatefirms) that were realised in the coming favorable policies from the central government.

Finally, we conducted additional analysis on the differences in the effects of different institutional capitals on their technology capability and technology commercialisation capability. Our results suggest that a firm’s technology capability, compared with its technology commer-cialisation capability, would benefit more from informal institutional capital (p < 0.001), whereas a firm’s formal institutional capital would improve these two capabilities by a relatively equal measure (p > 0.1). Therefore, managers may have to plan their CPA in terms of their resources and capabilities.

5.3. Limitations and future research

Despite its contributions, our research has several limitations. First, we theoretically illustrate the extent to which afirm’s RCPA and PCPA influence the perceptions of the firm’s institutional surroundings in terms of institutional legitimacy and power, and as such the argument is implicitly supported by the empirical results. However, future research is encouraged to demonstrate this notion by developing the scales that reflect how the institutional actors around a firm are influenced by the firm’s political activities. Second, we did not consider contingent vari-ables as suggested byPeng et al. (2009). Future research could examine the contingencies of the CPA-institutional capital-capability link in terms of afirm’s internal conditions, market conditions, and macro-institutional environment. Third, ourfindings are more salient in the context of China and other transitional economies that have similar political environments than in developed countries. Future research could examine the CPA-institutional capital-capability link across other transitional economies and developed economies to test the general-izability our research. In addition, measuringfirms’ practices in both the non-market and market areas is a challenging task, in that re-spondents that involved in various functional departments (e.g., mar-keting, R & D, strategic planning) and management positions (e.g., top managers, middle level managers) may be knowledgeable and possess accurate information in one area but may not be specialized in another area. Though we have compared the responses from various positions and functional department (i.e., technological managers v.s. non-tech-nological managers), and the results showed no significant difference, future research may consider collecting specific information from the specialized managers to increase the accuracy of empiricalfindings. Acknowledgement

Our thanks go to National Natural Science Foundation of China (71602157, 71672138, 71640014), and the Soft Science Research Program in Shaanxi Province (2017KRM066).

Appendix A. Measurement Items, Factor Loadings, and Internal Reliabilities

Item (Composite Reliability) Cronbach’s

alpha

Factor loadings To what extent do your agree with the following statements according to your company?

Relational corporate political activity (0.941) 0.905

(Adopted fromGuo et al., 2012; Peng & Luo, 2000; Li et al., 2011)

Ensuring good relationships with influential government officials 0.925

Having good relationship with multilevel government departments 0.929

Improving our relationships with government has been important to us. 0.896

(Adopted fromLuo & Junkunc, 2008; Deng et al., 2010)

Participate in government decision process to avoid adverse effect frequently. 0.857

Participate in government-organized and public social activities frequently 0.801

(e.g., charity, environment protection)

Protect corporate social image and status through public relation activities. 0.820

Participate in government decision process directly as NPC and CPPCC 0.746

Influence the formulation of public policy through different ways (e.g., lobbying) 0.821

Formal institutional capital (0.932) 0.901

(Adopted fromLi & Atuahene-Gima, 2001; Lu et al., 2010)

Please indicate the extent to which in the last three years governments and agencies have:

Provided needed technology information and technical support 0.858

Played a significant role in providing financial support 0.917

Helped in obtaining licenses and equipment 0.909

Provided directfinancial policies (e.g., tax reduction; subsidies). 0.834

Informal institutional capital (0.930) 0.905

(Adopted fromGao et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010)

Please indicate the extent to which in the last three years yourfirm has utilised the relational network to acquire:

Important information about market and customer needs; 0.808

Advanced managerial experience; 0.868

Externalfinancial support; 0.826

Advanced technology; 0.888

Professional talents. 0.868

Technology Capability (0.933) (Adopted fromZhou & Wu, (2010)) 0.904

Acquiring and utilizing important technology information 0.831

Responding to technology changes 0.894

Mastering the state-of-art technologies 0.896

Developing a series of innovations constantly 0.904

Technology commercialization capability (0.922)

(Adopted fromLi et al., 2008) 0.887

Ourfirm has efficiently use all the patents and know-how 0.843

Ourfirm develops a large number of products quickly 0.887

Ourfirm introduces a large number of products into market quickly 0.920

The new products developed by ourfirms have a bright market future 0.803

References

Afuah, A. (2002). Mapping technological capabilities into product markets and compe-titive advantage: The case of cholesterol drugs. Strategic Manage Journal, 23(2), 171–179.

Ahlstrom, D., Bruton, G. D., & Yeh, K. S. (2008). Privatefirms in China: Building legiti-macy in an emerging economy. Journal of World Business, 43(4), 385–399.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 396–402.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Baron, D. P. (1995). The nonmarket strategy system. Sloan Management Review, 37(1), 73.

Bonardi, J. P., Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2005). The attractiveness of political mar-kets: Implications forfirm strategy. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 397–413.

Boubakri, N., Guehami, O., Mishra, D., & Saffar, W. (2012). Political connections and the cost of equity capital. Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(3), 541–559.

Burt, R. S. (1990). Kinds of relations in American discussion networks. Structures of power and constraint, 411–451.

Chen, X., & Wu, J. (2011). Do different guanxi types affect capability building differently? A contingency view. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(4), 581–592.

Chen, C. J. (2009). Technology commercialization, incubator and venture capital, and new venture performance. Journal of Business Research, 62(1), 93–103.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 128–152.

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67.

Dahan, N. (2005). A contribution to the conceptualization of political resources utilized in corporate political action. Journal of Public Affairs, 5(1), 43–54.

Davenport, T. H. (2013). Process innovation: Reengineering work through information tech-nology. Harvard Business Press.

De Figueiredo, J. M., & Silverman, B. S. (2006). Academic earmarks and the returns to lobbying*. Journal of Law and Economics, 49(2), 597–625.

De Villa, M. A., Rajwani, T., & Lawton, T. (2015). Market entry modes in a multipolar world: Untangling the moderating effect of the political environment. International

Business Review, 24(3), 419–429.

Deephouse, D. L., & Carter, S. M. (2005). An examination of differences between orga-nizational legitimacy and orgaorga-nizational reputation*. Journal of Management Studies, 42(2), 329–360.

Deng, X., Tian, Z., & Abrar, M. (2010). The corporate political strategy and its integration with market strategy in transitional China. Journal of Public Affairs, 10(4), 372–382.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional iso-morphism and collective rationality in organizationalfields. American Sociological Association, 48(April (2)), 147–160.

Dixit, A. K. (1998). The making of economic policy: A transaction-cost politics perspective. MIT press.

Epstein, E. M. (1969). The corporation in American politics. Prentice Hall.

Evans, P. (1997). The eclipse of the state? Reflections on stateness in an era of globali-zation. World Politics, 50(01), 62–87.

Frynas, J. G., Mellahi, K., & Pigman, G. A. (2006). First mover advantages in international business andfirm_specific political resources. Strategic Management Journal, 27(4), 321–345.

Gao, S., Xu, K., & Yang, J. (2008). Managerial ties, absorptive capacity, and innovation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(3), 395–412.

Gao, Y., Gao, S., Zhou, Y., & Huang, K. F. (2015). Picturingfirms' institutional capital-based radical innovation under China's institutional voids. Journal of Business Research, 68(6), 1166–1175.

Getz, K. A. (1991). Selecting corporate political tactics. In academy of management pro-ceedings (Vol. 1991, No. 1, pp. 326–330) (August). Academy of Management.

Grant, R. M. (2002). Contemporary strategy analysis: Concepts, techniques, applications (4e). Blackwell.

Guo, H., Xu, E., & Jacobs, M. (2014). Managerial political ties andfirm performance during institutional transitions: An analysis of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Business Research, 67(2), 116–127.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, Tatham, R. L., & WC (1998). Multivariate analysis. Englewood: Prentice Hall International.

Hassan, T., Hassan, M. K., Mohamad, S., & Min, C. C. (2012). Political patronage andfirm performance: Further evidence from Malaysia. Thunderbird International Business Review, 54(3), 373–393.

Hill, C. W. L., Jones, G. R., Galvin, P., & Haidar, A. (2007). Strategic management: An integrated approach (2nd Australasian ed.). Milton, Australia: John Wiley & Sons.

Hillman, A. J., & Hitt, M. A. (1999). Corporate political strategy formulation: A model of approach, participation, and strategy decisions. Academy of Management Review,

24(4), 825–842.

Hillman, A. J., Zardkoohi, A., & Bierman, L. (1999). Corporate political strategies and firm performance: Indications of firm-specific benefits from personal service in the US government. Strategic Management Journal, 20(1), 67–81.

Hillman, A. J., Keim, G. D., & Schuler, D. (2004). Corporate political activity: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 30(6), 837–857.

Hoskisson, R. E., Shi, W., Yi, X., & Jin, J. (2013). The evolution and strategic positioning of private equityfirms. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(1), 22–38.

Huber, J., & Kirchler, M. (2013). Corporate campaign contributions and abnormal stock returns after presidential elections. Public Choice, 156(1–2), 285–307.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL VIII: User’s reference guide. Mooresville. IN: Scientific Software.

Keim, G. D., & Zeithaml, C. P. (1986). Corporate political strategy and legislative decision making: A review and contingency approach. Academy of Management Review, 11(4), 828–843.

Kollmer, H., & Dowling, M. (2004). Licensing as a commercialisation strategy for new technology-basedfirms. Research Policy, 33(8), 1141–1151.

Lawton, T., McGuire, S., & Rajwani, T. (2013). Corporate political activity: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(1), 86–105.

Lawton, T., Rajwani, T., & Doh, J. (2013). The antecedents of political capabilities: A study of ownership, cross-border activity and organization at legacy airlines in a deregulatory context. International Business Review, 22(1), 228–242.

Lenway, S. A., & Rehbein, K. (1991). Leaders, followers, and free riders: An empirical test of variation in corporate political involvement. Academy of Management Journal, 34(4), 893–905.

Li, H., & Atuahene-Gima, K. (2001). Product innovation strategy and the performance of new technology ventures in China. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1123–1134.

Li, Y., Guo, H., Liu, Y., & Li, M. (2008). Incentive mechanisms, entrepreneurial orienta-tion, and technology commercialization: Evidence from China's transitional economy*. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 25(1), 63–78.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114.

Lu, Y., Zhou, L., Bruton, G., & Li, W. (2010). Capabilities as a mediator linking resources and the international performance of entrepreneurialfirms in an emerging economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3), 419–436.

Luo, Y., & Junkunc, M. (2008). How private enterprises respond to government bu-reaucracy in emerging economies: The effects of entrepreneurial type and govern-ance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(2), 133–153.

Luo, Y. (2003). Industrial dynamics and managerial networking in an emerging market: The case of China. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1315–1327.

Lux, S., Crook, T. R., & Woehr, D. J. (2011). Mixing business with politics: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of corporate political activity. Journal of Management, 37(1), 223–247.

Markman, G. D., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2008). Research and technology commer-cialization. Journal of Management Studies, 45(8), 1401–1423.

Mitchell, W., & Singh, K. (1996). Survival of businesses using collaborative relationships to commercialize complex goods. Strategic Management Journal, 17(3), 169–195.

Nevens, T. M., Summe, G. L., & Uttal, B. (1990). Commercializing technology: What the best companies do? Harvard Business Review, 152–163.

North, D. C. (1990). A transaction cost theory of politics. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 2(4), 355–367.

Oliver, C., & Holzinger, I. (2008). The effectiveness of strategic political management: A dynamic capabilities framework. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 496–520.

Oliver, C. (1997). Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and re-source-based views. Strategic Management Journal, 18(9), 697–713.

Park, S. H., & Luo, Y. (2001). Guanxi and organizational dynamics: Organizational net-working in Chinesefirms. Strategic Management Journal, 22(5), 455–477.

Peng, M. W., & Luo, Y. (2000). Managerial ties andfirm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 486–501.

Peng, M. W., Wang, D. Y., & Jiang, Y. (2008). An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5), 920–936.

Peng, M. W., Sun, S. L., Pinkham, B., & Chen, H. (2009). The institution-based view as a third leg for a strategy tripod. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(3), 63–81.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods,

Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Puck, J. F., Rogers, H., & Mohr, A. T. (2013). Flying under the radar: Foreignfirm visi-bility and the efficacy of political strategies in emerging economies. International Business Review, 22(6), 1021–1033.

Rajwani, T., & Liedong, T. A. (2015). Political activity andfirm performance within nonmarket research: A review and international comparative assessment. Journal of World Business, 50(2), 273–283.

Sheng, S., Zhou, K. Z., & Li, J. J. (2011). The effects of business and political ties on firm performance: Evidence from China. Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 1–15.

Shi, W., Markóczy, L., & Stan, C. (2013). The continuing importance of political ties in china. Academy of Management Executive, 28(1), 57–75.

Shirodkar, V., & Mohr, A. T. (2015). Explaining foreignfirms' approaches to corporate political activity in emerging economies: The effects of resource criticality, product diversification, inter-subsidiary integration, and business ties. International Business Review, 24(4), 567–579.

Shu, C., Zhou, K. Z., Xiao, Y., & Gao, S. (2014). How green management influences product innovation in China: The role of institutional benefits. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–15.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

Sull, D. N. (2005). Made in China. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Sun, P., Mellahi, K., & Thun, E. (2010). The dynamic value of MNE political embedd-edness: The case of the Chinese automobile industry. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7), 1161–1182.

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350.

Tost, L. P. (2011). An integrative model of legitimacy judgments. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 686–710.

Tsang, E. W. (1998). Can guanxi be a source of sustained competitive advantage for doing business in China? The Academy of Management Executive, 12(2), 64–73.

Van Bruggen, G. H., Lilien, G. L., & Kacker, M. (2002). Informants in organizational marketing research: Why use multiple informants and how to aggregate responses. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(4), 469–478.

Wöcke, A., & Moodley, T. (2015). Corporate political strategy and liability of foreignness: Similarities and differences between local and foreign firms in the South African Health Sector. International Business Review, 24(4), 700–709.

Weidenbaum, M. L. (1980). The changing nature of government regulation of business. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 2(3), 345–357.

Weiss, L. (2000). Globalization and state power. Development and Society, 29(1), 1–15.

Xu, K., Huang, K. F., & Gao, S. (2012). The effect of institutional ties on knowledge ac-quisition in uncertain environments. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(2), 387–408.

Yi, Y., Liu, Y., He, H., & Li, Y. (2012). Environment, governance, controls, and radical innovation during institutional transitions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(3), 689–708.

Yoffie, D. B. (1987). Corporate strategies for political action: A rational model. Business Strategy and Public Policy, 43, 60.

Zahra, S. A., & Nielsen, A. P. (2002). Sources of capabilities, integration and technology commercialization. Strategic Management Journal, 23(5), 377–398.

Zhou, K. Z., & Wu, F. (2010). Technological capability, strategicflexibility, and product innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 31(5), 547–561.

Zhou, K. Z., Yim, C. K., & Tse, D. K. (2005). The effects of strategic orientations on technology-and market-based breakthrough innovations. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 42–60.

Zimmerman, M. A., & Zeitz, G. J. (2002). Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. Academy of Management Review, 27(3), 414–431.