國

立

交

通

大

學

外國文學與語言學研究所文學組

碩

士

論

文

吳天章作品中的詭態美學

The Spectacle of Grotesque: The trilogy of Wu Tien-chang’s Works

研 究 生:周世航

指導教授:張靄珠 教授

劉瑞琪 教授

The Spectacle of Grotesque: The trilogy of Wu Tien-chang’s Works

研究生:

周世航 Student: Shih-hang Chou

指導教授:

張靄珠 博士

劉瑞琪 博士

Advisor:

Dr. I-chu Cang

Dr. Jui-chi Liu

國立交通大學

外國文學與語言學研究所文學組

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics College of Humanities and Sciences

National Chiao Tung University in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Master

in

Foreign Literatures and Linquistics August 2007

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

學生:周世航 指導教授:張靄珠博士

劉瑞琪博士

國立交通大學外國文學與語言學研究所文學組碩士班

中文摘要

本論文將吳天章歷年的作品分成三期,以傅柯(Michel Foucault)在《不

正常的人》中所討論的政治詭態和羅素(Mary Russo)提出的兩種詭態

(Carnival and the Uncanny)來探討其作品在不同時期所表現的詭態樣貌。

本論文由影像分析一方面試圖找出各時期的主題,另一方面也企圖從這些

主題中了解其作品的寓意。

吳天章第一時期(1990 年-1991 年)作品裡的政治領袖肖像呈現了他對

政治議題和社會變遷的關心。第二時期(1993 年-1997 年)的主題轉向了個

人慾望和在地文化,他用俗麗的裝飾和攝影的概念塑造出了獨特的女性詭

態影像。第三時期(2002 年-至今)的作品運用了電腦科技,模擬複製出各種

怪胎或是肉體,並配合文字來挑戰對於因果輪迴和宗教勸世的傳統價值

觀。吳天章的作品由政治強人、個人肖像至近期的嘉年華式眾生相,都利

用詭態的驚世駭俗來吸引觀者的目光。他的作品能和同期藝術之作有所區

別之處就在於他極具後現代特色的拼貼和恣仿風格造成的吳式幽默。

關鍵字:吳天章、詭態、嘉年華、傅柯、巴赫汀、幽默、後現代主義

iStudent: Shih-hang Chou Advisors: Dr. I-chu Cheng

Dr. Jui-chi Liu

Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

National Chiao Tung University

ABSTRACT

In this thesis, Wu Tien-chang’s works are divided into three periods and are

investigated with Foucault’s grotesque of political monsters in Abnormal (2003)

and the two kinds of grotesques by Russo – the carnival grotesque and the

uncanny grotesque (1995: 7). By analyzing the images, I define a theme for each

period and show the allergy of each period through the themes.

During the first period (1990-1991), Wu manipulates the images of four

Chinese political leaders (Chiang Kai-shek, Chiang Ching-kuo, Mao Tse-tung

and Deng Hsiao-ping) to express his concerns about the political issues and the

social transition. During the second period (1993-1997), he uses feminized

figures in a way of photography to represent the uncanny grotesque with garish

decorations in order to show his concern about personal desires and the local

culture. During the third period (2002- present), Wu applies digital techniques in

his pictures to generate and reproduce all kinds of freaks and bodies. He also

uses religious texts to challenge the traditional values about reincarnation and

the religious dissuasion. Wu uses the features of postmodernism – pastiche and

collage – to achieve “Wu’s humor” which distinguishes him as a unique artist in

Taiwan. From the political leaders to common people, and even to the carnival

of all flesh, Wu’s grotesque images always draw our attention.

Keyword: Wu Tien-chang, Grotesque, Carnival, the Uncanny, Michel

Foucault, Mikhail Bakhtin, Humor, Postmodernism

I would like to express my gratitude to my parents who have been

supporting me all the time.

Also, I am deeply indebted to my advisors, Prof. Jui-chi Liu and Prof.

I-chu Chang, and my committee member, Prof. Juey-fu Hsiao, for their

patience and instruction. In addition, I sincerely want to thank for my

classmates who have helped me during the preparation of this thesis.

Although I did not have enough time to be with my friends in

Taipei, especially the one in America, they kept encouraging me through

e-mail or phone in these years. They always help me without demanding

any repayment. I am very grateful to have you! I can never finish my

thesis without their support.

Chinese Abstract ……… i

English Abstract

……… ii

Acknowledgment

……… iii

Contents

……… iv

Illustrations

……… v

Chapter One

Introduction……… 1

1.1

Three Periods of Wu’s Works………

4

1.2

Literature Review………

6

1.3

The Organization of Chapters………

13

Chapter Two

The Monstrosity of Wu’s Political Iconology………

17

2.1

The Grotesque in Foucault’s Abnormal……… 18

2.2

The Theme of Four Eras Series………

20

2.3

Iconographic Study of Wu’s Icon works of Political

Strongmen………

26

Chapter Three

The Uncanny Grotesque in Wu’s Works from 1993 to

1996………

30

3.1

Theory of Uncanny Grotesque………

30

3.2

The Themes of Wu’s Works during the Second Period

33

3.3

The Gaze behind the Mask………

37

Chapter Four

The Carnival of Grotesque in Wu’s Works from 2002

up to now………

42

4.1

Theory of Carnivalesque Grotesque………

43

4.2

The Theme of Wu’s Series after the Year 2000……… 45

4.3

The Carnival of Wu’s Grotesque Images……… 48

4.4

Questions on Wu’s Grotesque Images………

51

Chapter Five

Conclusion……… 57

5.1

The Style of Wu’s Art Works……… 57

5.2

The Humor of Wu’s Grotesque Style……… 59

5.3

The Significance of Wu’s Grotesque Images………… 60

Works Cited

………

63

Figures

……… 68

List of Figures

Fig. 1 Wu Tien-chang. Sayonara, Mixed Media, 120 x 80 cm, 1994.

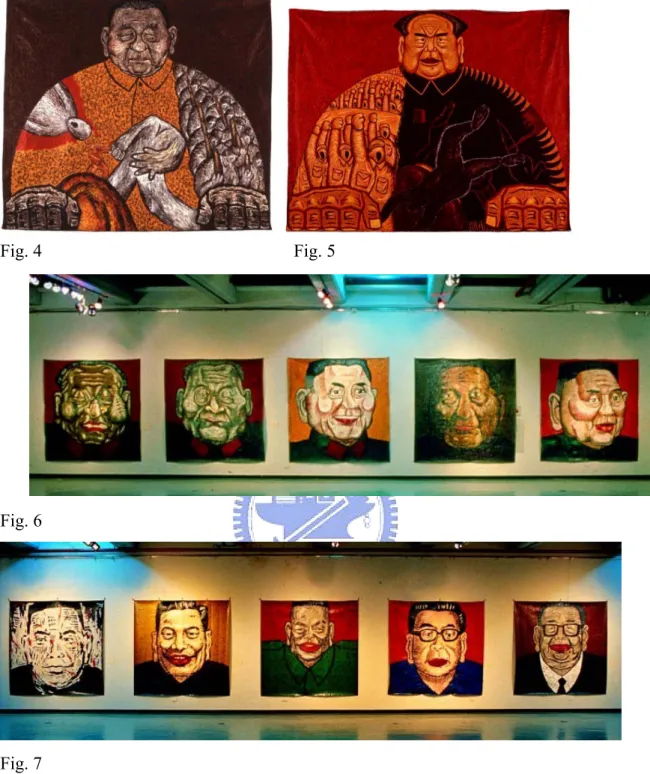

Fig. 2 Wu Tien-chang. The Rule of Chiang Kai-shek, Oil and Canvas, 310 x 340 cm, 1990. Fig. 3 Wu Tien-chang. The Rule of Chiang Ching-kuo, Oil and Canvas, 310 x360 cm, 1990. Fig. 4 Wu Tien-chang.The Rule of Mao Tse-tung, Oil and Canvas, 310 x 400 cm, 1990.

Fig. 5 Wu Tien-chang. The Rule of Deng Hsiao-ping, Oil and Canvas, 310 x 360 cm, 1990. Fig. 6 Wu Tien-chang. Four Eras, (Part of Deng Hsiao-ping), Mixed Media, 1991.

Fig. 7 Wu Tien-chang.Four Eras, (Part of Chiang Ching-kuo), Mixed Media, 1991. Fig. 8 Wu Tien-chang.Four Eras, (Part of Mao Tse-tung), Mixed Media, 1991. Fig. 9 Wu Tien-chang. Four Eras, (Part of Chiang Kai-shek), Mixed Media, 1991.

Fig.10 Mei Dean-E. Three Principles of People Reunify China, Mixed Media, 157 x 122 cm, 1991.

Fig.11 Mei Dean-E.Taiwan Loves Japan/ Japan Loves Taiwan, Digital Print, 159 x 113 cm, 1998.

Fig.12 Guo, Jen-Chang. 95’-96’ Chronicles: President and Vice President, Acryl and Canvas, 390 x 200 cm 1996.

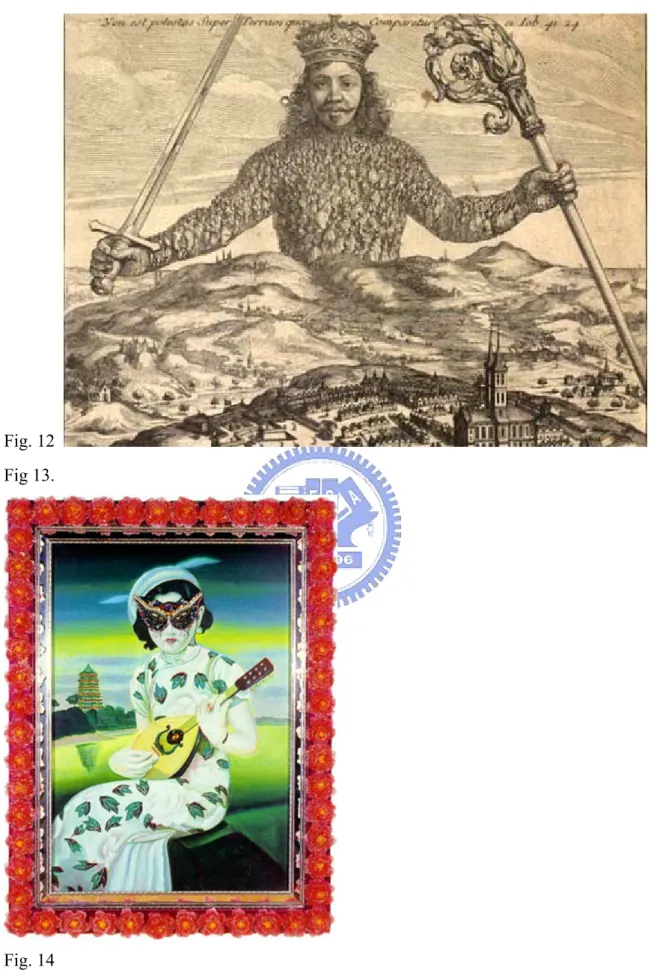

Fig.13 Abraham Bosse. Frontispiece of Leviathan, Etching, 1651.

Fig. 14 Wu Tien-chang.Dreams of Past Era I, Mixed Media, 120 x 80 cm, 1994. Fig.15 Wu Tien-chang.Dreams of Past Era II, Mixed Media, 220 x 180 cm, 1995. Fig.16 Wu Tien-chang.Dreams of Past Era III, Mixed Media, 120 x 80 cm, 1996. Fig. 17 Wu Tien-chang. Dreams of Past Era IV, Mixed Media, 210 x 168 cm, 1997. Fig. 18 Wu Tien-chang. Dreams of Past Era V, Mixed Media, 170 x 130 cm, 1997.

Fig. 19 Wu Tien-chang. Endless Love in Temporal World, Mixed Media, 218 x 206 cm, 1997. Fig. 20 Li Shin-chiao. On the Market, Oil and Canvas, 149x 148 cm, 1945.

cm, 1993.

Fig. 22 Wu Tien-chang. United in Our Effect, Digital Print, 219 x 164 cm, 2002.

Fig. 23 Wu Tien-chang.Work Together toward Same Goal, Digital Print, 180 x 228 cm, 2002. Fig. 24 Wu Tien-chang.Dreaming of Golden Millet, Digital Print, 180 x 228 cm, 2003. Fig. 25 Wu Tien-chang.Spirit Dreaming Conjuration, Digital Print, 2004.

Fig. 26 Wu Tien-chang.Spell to Shift Mountains and Overturn Seas, Digital Print, 2005. Fig. 27 Wu Tien-chang. Part of Spirit Dreaming Conjuration, Digital Print, 2004.

Fig. 28 Wu Tien-chang.Central part of Spirit Dreaming Conjuration, Digital Print, 2004. Fig. 29 Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. “Monstrosités.” 1837.

Fig. 30 Wu Tien-chang.English Text of Spirit Dreaming Conjuration. 2004. Fig. 31 Wu Tien-chang.Chinese Text of United in Our Effect. 2002.

Chapter One Introduction

Taiwan underwent drastic socio-political transition from the 1980s to the 1990s. Before the lifting of martial law in 1987, people had been prohibited from freely expressing

themselves under the rule of the authoritarian regime. After the lifting of martial law, the society is more tolerant of diverse voices. Radical artists in Taiwan who witnessed the rapid socio-political changes started to breathe into their art pieces with free spirits, experimental art forms, and socio-political critiques. Wu Tien-chang (吳天章), who is one of the leading radical artists, has been well aware of the critical power of arts and has imbued his art works with critiques even before the lifting of martial law. Before he became famous, together with Lu Yi-chung (盧怡仲), Yang Mao-lin (楊茂林) and other artists, they found “101 Modern Art Group” (101 現代藝術群) in 1982. Their paintings are in a style of Neo-Expressionism, which is defined in Contemporary art in Taiwan (2002):

[…] the appropriation of accomplished images, techniques or styles stimulate the audience’s imagination and also convey ethnic or native cultural fables, ideological symbols, myths or imagined world. The appropriation [by means of] the adoption of accomplished images contains the history of art, myths, legends, primitive totems […] etc.. The style and techniques are not rational but more emotional, and they are not constrained by specific methods.”1 (Hsieh 95)

While his colleagues, such as Lu Yi-chung, only used folk legendary stories to softly present

1 「挪用已有圖案、技法或風格,企圖喚起觀眾的想像,表達民族或本土文化的寓言、意識型態象徵、神

話或想像世界。已有的圖像、計法或風格的挪用,指得是[…]取自現成圖像。現成圖像的範圍包括美術史、 神話傳說、原始圖騰[…] 等等。[…] 風格、技法指得是已有的風格或技法,並無特定方式,但屬於情緒 化而非理性的形式。」(謝東山 95)

their ideas, Wu expressed himself in a more straightforward and violent way. He chose to challenge political totems, taboos, and political issues as a way to express himself. As a result, he became distinct from the other artists in his group. By the time martial law was lifted, he was clearer about his critical perspective. In his series of About the X Color’s Hurt (《關於 X 色的傷害》) (1986) and A Symptom of the “Syndromes of the World Injury” (《傷害世界症 候群》) (1986-87), he unreservedly displayed the social problems and the damages caused by the political incidents. These works were published when martial law was about to be lifted, but the penetrating critiques can already be seen. The concrete images in his post-martial law art works astonished the viewers. It was a visual impact that the viewers would never have a chance to see during the period of martial law.

The exhibition of Four Eras (《四個時代》) (1991) made Wu famous in the 1990s. His original and forceful political “big heads” are mirror images of four political strongmen. He used them to present his parody and criticism of the political authority. He paints the images in a comic way and exaggerates the size of their bodies. Wu is very responsive to the changes of the socio-political climate. In the mid-1990s, his interests went from political issues to personal memoirs not only because of the ebbing of the political waves, but also because of a personal reason: his grandmother’s death in 1992. According to my interview with him, after she passed away, he started to think about the meaning of life. Although the flowers and the decorations in his grandmother’s funeral are very rough and fake, they never wither. People are eager for an eternal life; therefore, the flowers may convey the desire for it. As a result, Wu became fascinated with the fake world. The paradox inspires him to think about the unique culture in Taiwan, where his ideas come from. The pictures in the series of Dream of

The retro-style2 setting confuses the viewers’ sense of time and space. This style is different from his previous ones and indicates the shift of his interest from political events and figures to daily life and ordinary people.

The time he begins to create works using mixed media is after the millennium year. With the approaching of the digital era, Wu keeps up with the technologies. Rather than submitting to the control of the technology, he utilizes them to draw the outlines of his reflections and introspections. His creating technique is called “‘technical revivalism’ [which] uses the latest computer technologies to create artworks, and at the same time adopts a Chinese way of thinking to understand and interpret the functions of computers to establish a common

ground”3 (Pan 138). “To establish a common ground” indicates that the Western and Chinese cultures can work together and share some basic concepts. The digital world implies that there may be one “truth” beyond our being. It is a world composed of 0 and 1, just like mathematics formulas. No matter how the world is changing, the formulas are always self-evident. Wu associates it with the Chinese philosophy that there is always someone controlling our fate-- someone we will never know. Therefore, we take it as the god’s or the fate’s manipulation. His integration and association of Chinese and Western cultures produce a third hybrid culture.

In Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), Fredric Jameson notes that “everything in the [nostalgia] film […] conspires to blur its official

contemporaneity and make it possible for the viewer to receive the narrative as though it were […] beyond real historical time” (Jameson 1991: 21). Wu has been using elements of

reminiscence to create a sense that is beyond time and space. In addition, he has employed collage and pastiche, which are important features in postmodernism, in his art works.

2 In Wu’s series, the retro style suggests the aesthetics represented in the early days of Taiwanese agriculture

society.

3 「所謂科技復古(technical revivalism),是一方面利用最新的電腦技術創作,另一方面用中國的思考模式

Inspired by vintage salon pictures, calendar posters, and New Year pictures, he produces works that are full of reminiscence as well as creativity. Take the series of Dream of Past Era for example, although it looks like that the work is made of reminiscent pictures, it is not necessarily the case; the work projects images that seem to be beyond time and space. Jameson considers this approach “by way of the art language of the simulacrum, or of the pastiche of the stereotypical past, endows present reality and the openness of present history with the spell and distance of a glossy mirage” (21).

1.1 Three Periods of Wu’s Works

According to the styles and the issues mentioned above, Wu’s works can be divided into three periods. In his earlier works, the issue is mainly on authoritative political icons and social events. The painting of the four strongmen and the works before this series clearly show his concern about the oppression and resistance at that time. His works in his early career are famous for rebelling against the authority. The work On the Damage of “Spring

and Autumn” (《再會吧!春秋閣》) in 1993 opens up Wu’s creativity to another subject —

the feminine image. Not only his subjects, but also his style is changing: from comic-like leaders to creepy figures. In the similar series, Dream of Past Era (《春宵夢》), the female bodies attract the viewers. Underneath the female bodies and the feminized images, there are ghosts among them. The living, the dead, and something between them set up his unique carnival, which is taken as a good art piece of his grotesque aesthetics succeeding his previous work. The motif of gender issues and sexual identity shows not only Wu’s aesthetics of

grotesque, but also his concern about identities. In Wu’s interview on Emancipation of Arts with Public Television Service, he claims that he places sexual issue over political issue in his works in the 1990s. Recently, he uses mixed materials with digital technologies to represent the traditional concept of “reincarnation” in his recent works after 2000. The combination of

the latest techniques and the ancient beliefs produces abnormal images. The transformation of Wu’s works, however, does not impair his sharp observations. On the contrary, it actually unfolds his critical thinking.

The focus of my project is his breakthroughs after the year martial law is lifted. After sketching the outline of his works in the previous paragraphs, I would like to divide his art career into three periods according to chronology and artistic styles. My chronological classification will also be explained in the following sections. Here are the three periods I have come up with:

1. 1990- 1991: Four Eras (《四個時代》) (1991) and The Rule of Chiang Kai-shek (《關 於蔣介石的統治》) (1990), The Rule of Chiang Ching-kuo (《關於蔣經國的統治》) (1990), The Rule of Mao Tse-tung (《關於毛澤東的統治》) (1990), and The Rule of Deng

Hsiao-ping (《關於鄧小平的統治》) (1990).

2. 1993 - 1997: On the Damage of Spring and Autumn (《再見吧春秋閣》) (1993),

Dreams of Past Era I-V (《春宵夢 I-V》) and Endless Love in Temporal World (《紅塵

不了情》)(1997).

3. 2002 - present: United in Our Effort (《永協同心》) (2002), Work Together toward

Same Goal (《同舟共濟》)(2002), Dreaming of Golden Millet (《黃粱夢》)(2003), Spirit Dreaming Conjuration (《夢魂術》) (2004), and Spell to Shift Mountains and Overturn Seas (《移山倒海術》)(2005).

These three periods are also agreed by Wu4. Although I have divided them into three periods, I do not mean to separate them into isolated classifications. In fact, there are continuous

relations among them. The themes may be different, but there are some concepts or certain styles that remain the same, which I will illustrate later. This is why I regard them as a trilogy of his works.

1.2 Literature Review

Most of the critics comment that the main themes of Wu’s works during his early period are political issues. After he made a transition into topics of desires by using feminized images, the reviews focus on the gender problem and the nostalgia style. In his latest works, the criticism of his digital images is about his philosophy inspired by technology. Overall, it is Wang Chia-chi’s (王嘉驥) review that inspires me to think more thoroughly about the

“aesthetics of the grotesque” (Wang 66), and it is also the start point of my thesis. Most literatures regarding Wu and his works are reviews and interviews distributed in exhibition catalogs and journals. There are only a few academic journals for me to consult with.

However, I will still try to analyze them with literary theories to produce my discourse about Wu’s works. I will present literary reviews according to the three periods. Dividing his works into three parts not only makes his transformation in artistic style more noticeable, but also addresses the variation of the grotesque in the works.

The most difficult part is the first period because the literature is insufficient. There is only one special column on Four Eras where I can learn Wu’s creating motive. It is based on an interview5 between Lu Yi-chung (盧怡仲) and Wu in 1990. The interview has become an important reference. In that, Wu declares that he became more concerned about political issues as he started to investigate the history. Affected by many historical events, such as Sino-Japanese Wars and Tien-an Men Square Massacre, he realizes the tragedy and the people affected by ideological struggles (159). In the interview, he elucidates how he uses the fusion

5 Chiang Yao, “Tumbling in the Wave of History: The Four Eras of Wu Tien Chang’s Iconology,” Lion Art 235

of physiognomy and masks in Chinese operas to create his iconography. Wu clarifies that his iconography is different from Andy Warhol’s, but the information is not strong and evident enough for the viewers to see. (In my next chapter, I will have a further discussion about these two types of iconography.) Chen Hsiang-Chun (陳香君) points out a problem that the viewers may not be able to see the critical issues, such as the conflicts between different ethnic groups and ideologies which profoundly come from the autocrats’ images in Wu’s paintings (Chen 112). Hsueh Haui-chi (薛懷琦) talks very little about Wu’s works of the first period in her thesis, “The Meanings of Femininity of Wu Tien-chang’s Work in 1990s” (《一九九○年代吳 天章作品中的女性寓意》). Because the topic of her thesis emphasizes the feminized features and the meanings derived from them, the male figures are not the main subject for her

discussion. And the works in the first period are all male. She approves that Wu utilizes the grotesque appearances to deconstruct the authority which used to be represented in noble and serious forms. However, Hsueh indicates that these political icons are only representing the frustration toward the political reality6. In the dialectical discussion on the portraits of the four political strongmen, she thinks that Wu uses caricatures to wear down their prominent images. She concludes that in Wu’s works the male representation of the political icons is much weaker than the female one in the series of Dreams of Past Era (Hsueh 57). Although I agree with Hsueh on the positive power of Wu’s female images in his works in the 1990s, I believe this conclusion is partial. She ignores the social-political contexts that Wu intends to address and it is not enough to talk only about the sexuality and gender issues. In my view, the power of Wu’s grotesque images primarily does not come from the gender issues, but actually from the folk humor. For example, Wu’s political icons actually are influenced by Chinese opera masks and editorial comics. Also, the portraits and photos of the ladies are decorated with the artificial flowers used in Chinese funerals. These characteristics will not be recognized if the

6 Huai-chi Hsueh, “The Meanings of Femininity of Wu Tien-chang’s Work in 1990s,” MA thesis, Cheng Kung

viewers are not aware of or do not know the culture Wu refers to. However, they all come from our life. They are the exclusive humor for the folk of the particular culture.

During the second period, the grotesque images are not limited to the political images which are predestined to criticize the contemporary society. It can be seen that during this period, the political leaders are replaced by the ladies and the sissies in a photo studio. Due to the gestures of the female images in the frames, most of the discussions lead to the topic of desires. This topic in Wu’s works is a starting point for my project. In Huang Hai-ming’s (黃 海鳴) review, he attempts to investigate the desires in Wu’s works. He states “his works may be ‘the constantly transformed reappearance of the repressed things’” which “include

gaudiness, desire, memory and corrosion”7 (Huang 9). According to Huang, “the holes” (e.g. eyes and mouth) are the secret paths to reveal the desires. Instead of being exposed through the holes, the desires are detoured and disguised. The eyes which have a “function […] as an object from within which seeps, flows, or grows; desire and ugly things frequently” do “not look outwards, or secretly reveal what one is thinking”8 (11). Huang describes these holes as the damp and rotten images, and they are erotic (11). Cheng also emphasizes his points on desire. He regards the desire from Wu’s work as the one about voyeurism. “When walking into Wu’s exhibition place, we were like sneaking into the chamber for adventure. It is full of ‘desire’ and waiting for an exit”9 (Cheng 315). He describes the whole visual impact as “obscure and smells like Formalin”10 (315). The sense of sight is associated with the sense of smell. The smelling is internalized to Wu’s series of Taiwanese women. “Memories […] filled with the strange odor of rotten food”11 (316) corresponds to Huang’s interpretation of 7 「『被壓抑物』包括了:艷麗、慾望、記憶及腐臭。」(黃海鳴 6) 8 「吳天章作品中的眼睛並不往外看,或只是偷偷的露一點眼神,它主要的是把眼睛(心靈)內部的,常常 是欲望的、醜陋的東西滲出來、流出來、長出來。」(黃海鳴 7) 9 「走進吳天章個展的現場,就好像少年時候偷偷摸摸到茶室去探險一樣,有一種滿『慾』等待著去找到 出口」(鄭乃銘) 10 「隱晦而瀰漫著福馬林衝鼻味。」(鄭 315) 11 「記憶 (...)充滿著如食物腐敗的奇異味道。」(鄭 316)

Wu’s desire. The So Long Venice series does not have a review as good as the Dream of Past

Era series although they are both depictions of human desire and the meretricious style.

Cheng considers that Wu’s presentation of “memory” is a hollow corpse which is constructed by flamboyant decorations and lighting. The series of So Long Venice does not have strong motif, and it is created for commercial factor12. For this reason, Wu does not value the series of So Long Venice as well.

In Cheng Hui-mei’s (鄭惠美) review, she is inclined to interpreting it as sexual desire which is also the main claim of the succeeding critics. The sissy soldier in On the Damage to

“Spring and Autumn” (《再見吧!春秋閣》) explicates her idea. The contradictory elements of

the masculine and feminine are shown in this piece. Cheng’s comment indicates that the purpose of putting the contradictory elements together serves for the “repressed and primal”13 (Cheng 252) desire, implying homosexual desire. The reading from the perspective of gender began from the review “Love Estranged: On the Maidens’ Obsession of Grief & Woe in Wu Tien-Chang’s Fantasy of Romantic Rendezvous” (〈春宵夢斷─吳天章《春宵夢》裡的閨怨 情結〉) given by Yang Chih (楊墀). It is based on psychoanalysis, and has some pellucid illustrations on this series. Yang thinks the series of Dream of Past Era symbolizes anxiety resulting from the oppression of patriarchy (Yang 75). Each woman in the series falls to be a materialized object and can only wait for the creative artists to give her infinite meanings (76). Women and men are contraries in this description. Although Yang appreciates Wu’s idea, the figures are still “on the maidens’ obsession of grief and woe”14 (75) in his implication.

Wu Wen-hsun (吳文薰) points out “[Wu’s works] are still controversial from the past issues of ‘the national identity’ to current one of ‘the gender identity’”15 (Wu 64). Again, the

12 Shih-hang Chou, personal interview, 1 Nov. 2006. 13 「被壓抑的原始慾望。」(鄭惠美 252) 14 「閨怨情結」(楊墀 75)

feminized figures challenge the moral standards and successfully draw the audience’s attention like the previous works do. The problem of national identity is a precise point, but the personal cares and the desire in the private field are equally important in Wu’s productions. As Hsueh Haui-chi applies psychoanalysis and feminism to interpret the female body and the national identity in her thesis, she indicates that the female images have an ambiguous relation to the male gaze. The object covering the female’s eyes in Sayonara (1994; fig 1) is like scarlet lip, which is associated with the pudendum16 (Hsueh 22). Either lips or pudendum does not belong to the part of eyes. It seems like it is cut from the original place and displayed to the viewers (22). Therefore, it implies the castration and arouses the fear of castration from the viewer’s sight17 (23). In Hsueh’s project, the feminist viewpoint and the psychoanalysis establish her argument. She thinks the feminized images do not diminish the power of resistance. On the contrary, they form an alternative way for national identity. Hsueh points out that the series of Dream of Past Era shows that Wu, as a Taiwanese artist, indeed uses local culture truly to represent the subjectivity of Taiwan (65). The empowerment comes from the strategy of performance, such as the drag queens and the campy boys. In the contrast, the male bodies in Wu’s works do not have autonomy. She thinks they are just figures without dignity controlled by Wu since he paints them in the grotesque and comical style (57). When the male images of the political icons are exhibited, the martial law is already lifted. Hence, the authority Wu wants to criticize is gone (56). She concludes that the problem of the gender consciousness reveals the political narrative and ideology of the nation (17). Hsueh takes Wu’s sissy sailor of On the Damage of “Spring and Autumn” as the example. The image of the sissy sailor in the navy refuses to submit the stereotype that a sailor should be masculine in order to protect the country. Therefore, when this work is displayed in the international

16 Huai-chi Hsueh, “The Meanings of Femininity of Wu Tien-chang’s Work in 1990s,” MA thesis, Cheng Kung

U, 2002, 22.

17 Huai-chi Hsueh, “The Meanings of Femininity of Wu Tien-chang’s Work in 1990s,” MA thesis, Cheng Kung

exhibition, it presents the image of Taiwan. In her argument, Hsueh remarks that the sailor’s gender consciousness presented in Wu’s work in fact is an allegory for the strong and confident identity of Taiwan (99) because the sissy boy represents the courage of Taiwanese to show their identity. It is also because of the artificiality and mannerism, such as the patent leather framing in On the Damage to “Spring and Autumn” which brings up the sense of fakeness. Wu tries to present the feminized figures with humor by ridiculing them. For example, the sailor in the pseudo-salon photo gives the viewers nothing but a comical feeling because of the contradictory stereotype between the virile army man and the sissy boy. It is a point that I focus on, and it is also the point that has not been treated seriously in the existing literatures.

Based on Huang’s writing on Wu’s style of “the rotten”, Wang Chia-chi goes further in his review. He concludes that the ghostly projection and the drag queen in Endless Love in

Temporal World (《紅塵不了情》)(1997) compose a work of “extremely stylization” (「極為

風格化」) (Wang 66). The moving images from the projector begin from a modern female in oil panting, but when she starts to dance, “she” becomes a drag queen. He names Wu’s style as the “aesthetics of the grotesque” (「怪誕美學」) within the “visual spectacle” (「視覺奇觀」) (66). However, it is a pity that he does not define and explain it any further. Can we support Wang’s analysis on Wu’s grotesque visual effects with effective theories? His statement inspires me to go further to investigate the “ugly” images of Wu’s works after 2000. I consider that the grotesque images penetrate through Wu’s creating career, but the third period is most remarkable for the grotesque style and the theory of the grotesque.

After Wu’s new art works in the third period are presented to the public, the critics start to notice his transition. First of all, it is the impact of computer technologies on the traditional values and the view of the world. The review of Li Wei-ching (李維菁) sums up the

associates Wu s with the progress of reincarnation (Li 250). Everything in a computer can be deleted by “format” without leaving any trace. “Undo”, a function of going back to the previous state, is like Meng-po soup (孟婆湯) in the folktales. After drinking it, people will lose their memory and never remember what has happened before. It may be a convenient function when we are using computers. Yet, it scares Wu because it seems to be able to change the truth and the memory (Lo 46). These functions used to be impossible in a

traditional way of thinking. Technologies frighten people, and they arouse the imagination of a matter of life and death. The technology of photography is another remarkable technology which reveals Wu’s ideas. According to Lo’s interview, Wu consciously applies Barthes’ concept of photography to his works. It symbolizes each moment’s existence as well as witnesses its death at the same time (Yao 75). Just like what Wu says, “[Barthes has talked about that] photography is a behavior of past tense”18 (Lo 44). The moment is dead as soon as we press the shutter button. When viewers look at pictures, they can sense the indescribable sadness which is what Wu calls “the nostalgia for the living world” (Pan 139). Yang

Ming-eh’s (楊明鍔) “Behind the Glory of a Halo-Vanity Fair of Wu Tien-chang” (〈光環的背 後─吳天章展演浮世虛華〉) also has a convincing point on Wu’s works after 2000. He claims that the figures in Spirit Dreaming Conjuration (《夢魂術》) are in a state of unconsciousness (Yang 30). Yang points out the feature of consciousness, but there is no further discussion about it. In addition, he regards Work Together toward Same Goal (《同舟共 濟》) as a “home party” where “the human being with dignity degenerate into grotesque ghosts and goblins”19 (31). He originally compares Wu’s figures in the series of Former and Current

Life to Chinese zombies in Hong Kong films. Yang believes that abnormal figures indeed can

attract our attention just like beauty figures (31). The ugliness in the works now has a more

18 「攝影是一種過去式的行為」(羅寶珠 44)。

powerful and positive interpretation. Nevertheless, one may ask why these distinctive and different bodies draw our attention. There is no literature on it yet; however, the grotesque images will be the kernel of my discussion.

Wu’s protagonists are never in a complete shape or normal size. The creepy atmosphere and the grotesque bodies are all over the place in his art works. I have been compelled by his aesthetics as well as by learning the symptom of the society implied in his works. Here, I would like to elaborate my ideas by using Foucault’s or Russo’s the concept of “grotesque”. Primarily, the theoretical applications in my analysis will be Freudian concept of “the

uncanny,” and Bakhtinan idea of “the carnival.” These theories and concepts can be applied to Wu’s art pieces and even the social and cultural contexts in them. In Mary Russo’s The

Female Grotesque: Risk, Excess and Modernity (1995), she generalizes two kinds of

grotesque mainly from the theories of Freud and Bakhtin: the carnivalesque grotesque and the uncanny grotesque. “The grotesque of carnival” is about social bodies and is related to class formation. “The grotesque of the uncanny” is about “the inner state” which is demanded by subjectivity (Russo 8-9). She also puts lots of effort to discuss about the body as an important type to present the grotesque. Her practical classification clarifies Wu’s grotesque world. Also, in the introduction, Russo states that “[the category of grotesque] emerged […] only in

relation to the norms which it exceed” (3). It points out the relation between the grotesque and the norms. The norm is one of the important terms what Foucault has emphasized in

Abnormal. Therefore, in this paper, I would elaborate on Foucauldian grotesque in relation to

Wu’s works as well.

1.3 The Organization of Chapters

The chapters in my thesis are developed in accordance with my division of Wu’s works. In Chapter Two, I will have an introduction to Wu’s works and the background of Taiwanese

contemporary art. The first period of Wu’s series reflects the transformation of the social, cultural and political situation. The transformation is a time for people to do self-reflection and self-examination (Liu 35). It is a foreshadowing for the coming current which

corresponds to the changes of the social order and the environment. Also, during the first period, there is normally only one figure in each piece of his oil painting. When there are multiple figures in the works, they are always presented in 2-dimension only. There will be an iconographic study of his icon works, and Four Eras will be the main series to be talked about. This period is also the starting point for him to create grotesque images.

In Chapter Three, I will examine the grotesque images during the second period.

Regardless of the type of works, such as oil painting and photographs, Wu’s feminized figures never look like normal people. Unlike the portraits during the previous period, the figures start to pose, but with covered eyes. Their grotesque gestures and looks construct a haunted atmosphere for the audience. It is also the phase that the technique of photography brings his works into a new era. In addition, Wu uses set-up photography in his works. It is a kind of performance that everything is well designed beforehand in front of the camera. The effects of set-up photography are added and they strengthen the images of the monstrous individuals in his works. Wu Wen-hsun notes that the author is so smart that he utilizes the traits of

photography. It indicates “the contradictions of death, which is absurd and insurmountable in our life”20 (Wu 64). I would like to use Barthes’ interpretation of phenomenology on the denotation of photography to analyze Wu’s works. It does not mean that all the works are made in a form of photography; it is the concept of photography that I want to apply to Wu’s works. Wu’s thoughts about life can be accentuated because of the techniques he uses. I believe that the illustrations foreshadow the coming of the grotesque as carnival.

As to the third period, Wu’s style is changing in techniques to reflect different mentalities.

His works during this period contain no more than just monologues; they now look like circuses or carnivals that are full of freaks and disabled people. They are the representations of the contemporary society. They have an allegorical function to show that the society is transforming from monophony to polyphony where people can fearlessly express all their desires through various manners. Wu does not choose to present them in the negative way. He painstakingly sets up his photogenic as a spectacle. It is a carnival where the minorities can talk and all the disaffection can be released. This positive side of the grotesque may also be derived from Bakhtin’s definition of “grotesque realism” that “[d]egradation here means coming down to earth, the contact with the earth as an element that swallows up and gives birth at the same time”(Bakhtin 21). Wu’s works embody the ideal Bakhtin’s carnival and the grotesque bodies. In this spectacle, he uses his unique black humor to smooth out the horror stories and make the images acceptable to the audiences at the first sight. However, after that, the impact of warnings and concerns comes along. Therefore, in Chapter Four, I will focus on the carnivals held by Wu’s grotesque images during this period. There is a dialectical thinking inherent in his art pieces after 2000. I intent to prove that Wu creates an allegory like

Bakhtin’s carnival for the grotesque bodies.

Last but not least, I will have a summary of Wu’s grotesque images during these three periods in Chapter Five. The common features that can be seen in Wu’s grotesque images are: they all have abnormal looks and defamiliarize what the viewers are familiar with. His

grotesque images are so ambiguous that they arouse the viewers’ anxiety. I believe that the grotesque presentation of his figures is not just for the visual effects. It also has a function to stimulate the introspection of the viewers. Through the “abnormal and weird” appearances of the artistic works, Wu successfully adds the folk humor as well as his serious introspection into his works. I attempt to apply literary theories to support my interpretation of Wu’s works during three different periods. Besides literary viewpoints, I will take social contexts and

Wu’s situation into account. It is my goal to provide an interdisciplinary perspective to the analysis of Wu’s works in the world of Taiwanese contemporary art.

Chapter Two

The Monstrosity of Wu’s Political Iconology

From 1990 to 1992, Wu Tien-chang created a series of oil-paintings closely related to the political issues. He gained the reputation from his groundbreaking creative works. The

comic-strip of these four political figures with the huge historical portraits, Wu’s The Rule of

Chiang Kai-shek (《關於蔣介石的統治》) (1990; fig. 2), The Rule of Chiang Ching-kuo (《關

於蔣經國的統治》) (1990; fig. 3), The Rule of Mao Tse-tung (《關於毛澤東的統治》) (1990; fig. 4), and The Rule of Deng Hsiao-ping (《關於鄧小平的統治》) (1990; fig. 5) are composed for the exhibition of Four Eras in Taipei Fine Art Museum in 1990. However, some critics suspected that his success might not be resulted from the innovation. They thought it was because Wu knew the climate of the society was changing and the people were expecting everything with an open attitude. For this reason, his series of the political portraits became the hit at that time when they are presented to the public. The historical background is that three years after martial law had been lifted, it was expected that Taiwanese contemporary arts needed to change the climate of the society. Therefore, numerous artists started to create critical art pieces to imply or signify the political issues. They used their art works or performances to challenge the authority. Wu was famous for painting the political figures directly. The impact was immediate and direct for the viewers when they faced these huge portraits. However, his authoritative icons did not cause the viewers profound respect for the political leaders. Portraits which used to be realistic and were supposed to strengthen our memory of the great men are changed to unrealistic and exaggerated forms. In this chapter, I would demonstrate how the authoritative icons are related to the images of the grotesque through the Foucauldian reading.

2.1 The Grotesque in Foucault’s Abnormal

In the course context of Abnormal, Valerio Marchetti and Antonella Salomoni consider that the “group of abnormal individuals” (331) originates from three types of people: the

monster, the undisciplined, and the onanist. Although each type emerges at different times, all

of them are against the laws. Foucault focuses on the monsters in the beginning chapters of his work. The reason why the monsters are grouped as abnormal is not because of their biological mutation or disability. They contravene the law because they are the judicial exceptions, which goad them into the group separated from the normal people. The

undisciplined can be tracked back to the17th and the 18th century. With the rise of capitalism, each individual is expected for contribution to the growth of the economy. Those who refuse to obey the law or disturb the social order may cause a loss to the society because it is against the principles of economics. Therefore, the undisciplined are categorized into the group of the abnormal. The onanists (masturbators), in the 18th century, were not a problem of morality but instead a problem of biology and medical science. That is to say, their behavior was

considered “somatization and pathologization of masturbation” (237) rather than just a moralization. Foucault looked at it as an intervention about juvenile sex. The intervention is the scheme and system of the power. The idea of “the abnormal” is the assemblage of the three types of people in 19th century. Besides, it is a medium to control the smallest unit of the society—the individual. The idea of the abnormal is a category produced by the power

relation. Foucault wants to highlight the power mechanism, and he tries to criticize the knowledge system which controls the social classification. Also, the abnormal is taken as the object under the knowledge of the power techniques which will be discussed further in the fourth chapter. In the following analysis of Wu’s works in this chapter, my main argument will be based on his analysis of the monsters, especially the moral monsters. To analyze the

disagreement with regard to the different social and cultural contexts.

Foucault has an archaeological discussion on moral monsters which are the type of the abnormal individuals in the 19th century. In his works, he puts the word “grotesque” in the context of power relation, which can be found in his first part of discussion about the monsters. It is involved with an authoritative mechanism, and “a discourse or an individual can have effects of power that their intrinsic qualities should disqualify them from having” (Foucault 11) as well. He attempts to clarify the grotesque figures coming from the

convergence of the judicial proofs and psychiatry. The convergence refers to the “discourses of truth and discourses that make one laugh” (1). Since the judicial truth and medico-legal opinions in the end of 18th century to 19th century depend a lot on psychiatry, there were some inappropriate or even ridiculous discourses. It is what produces the discourse of the grotesque. In his lecture in 1975 at the College de France, Foucault indicates that the grotesque is not only an essential process of arbitrary sovereign, but also “a possibility for the bureaucracy” (12). He cites an example of Dostoyevsky and Kafka in whose works the readers can find out the visionary perception of administrative grotesque. Foucault looks back to the grotesque power mechanism which can be found in Roman history where an emperor is “a mode of domination: a discourse qualification that ensured that the person who possessed maiestas” (12). Power is bound with the image provided by itself. “As a clown or a buffoon,” when Foucault talks about the functional feature of power, he thinks “[it] provided itself with an image in which power derived from someone who was theatrically got up and depicted” (13). The description of the sovereign or the bureaucracy can be the possible annotation for Wu’s

Four Eras that I presume the reflection at that time.

Foucault shows in his lecture on January 29th that “monstrosity as the natural

manifestation of the unnatural brought with it an indication of criminality” (81) in the 17th and the 18th century, but when it came to the beginning of the 19th century, there was a revered

relation between the monstrosity and the criminality. Monstrosity is “systematically suspected of being behind all criminality” (81). A crime means to endanger others, and what else is that a crime is also an offense against the sovereign in classic law. The punishment is the revenge of the sovereign, and it is a ritual that never achieves a balance. It is always “a sort of rivalry” and “a kind of surplus,” which reaches the “terrorizing character” (83). Paradoxically, the crime is shown again in the punishment because of its terrorizing character. The first moral monster is political monster, a criminal who breaks the social contract. Against the pact is “a kind of abuse of power”, which enables the criminal to become “a little despot who at his own level advances his personal interest like the despot” (93).

The visualization of Wu’s art pieces does not totally correspond to Foucault’s discourse. There is a discrepancy between Chinese history and Western history, especially Foucault stresses the one of Europe. However, Wu’s Four Eras embodies the concept of the moral monsters and transforms it into a very Chinese style (during this period, he has not soundly shown his locality yet), which will be demonstrated in the following paragraph. Also, with the help of comic effects, Wu contributes his own definition to the grotesque style during this period. His four political giants are the embodiment of the grotesque that they present the excess and the enormity of the enormous power.

2.2 The Theme of Four Eras Series

In the exhibition of Four Eras (《四個時代》), the portraits of the four political figures are displayed. Only a half body and the facial close-up are shown in each portrait. The

reputations of the four political leaders are diverse in different times and places. In their heydays, they had significant contributions to the society. However, it is unavoidable that they are under criticism. The four political figures, Mao Tse-tung, Deng Hsiao-ping, Chiang

contemporary history21. Mao Tse-tung, whose icon is considered a sacred image in China, is the founding father of People’s Republic of China. Mao’s and Deng’s portraits can be seen everywhere in China. The phenomenon unfolds the new age when portraits are not only to serve the purpose of sacredness. The political icons actually replace sacred images at this time while the religious icons are forbidden in Cultural Revolution. Chiang Kai-shek built up his own orthodox and wanted to consolidate the legitimacy of Republic of China in Taiwan. The icons of Chiang’s family, including him and his son Chiang Ching-kuo, are the products of the grand narrative22. Both father and son’s portraits are hung in all official buildings and public schools.

These four figures became a popular subject for criticism for Chinese contemporary artists to challenge the ideology of deification after the late 80s. The new sacred images they created bring forth a dialogue between the old and the new. The images also give the viewers a critical distance to think about the differences between each figure. In addition to Wu’s Four

Eras, some artists during the same period also make political figures for the purpose of

criticism. Take Mei Dean-E’s23 (梅丁衍) Three Principles of People Unite One China (《三民 主義統一中國》)(1990) (Fig.10) for example. Mei selects the founding fathers, Mao Tse-tung

21 Mao Tse-tung established People’s Republic of China, which resulted in KMT’s retreat to Taiwan. Guarding

against the Communist Party of China, Chiang Kai-shek took over Taiwan in 1949. Chiang claimed his

government as the only legitimation of Chinese political entity. However, the society was conservative under his authoritarian regime. Especially during the period of martial law, people were restrained from freedom of speech, publication, and organization of parties. In 1966, Mao started Cultural Revolution, which also silenced the people. Their successors, Deng Hsiao-ping in china and Chiang Ching-kuo in Taiwan were different from them. There were many economic reforms under Deng’s leadership. However, the protest in Tien-an Men Square in 1989 caused unknown number of dead. On the other part, Chiang Ching-kuo led an impetus to the major construction projects in Taiwan and accelerated the progress of economic growth. In 1979, the Formosa Incident happened during his period shocked the masses. But martial law is lifted in 1987 during his period as well.

22 “In Taiwan, the grand narrative is legitimated and rationalized through a temporal (historical) association to

the theory of orthodox of Chinese culture. Replying to an inquiry about the origin of his philosophy from Ma Lin, who had joined the organization Third International, Sun Yat-sen used the southern Song Neo-Confucian scholar Zhu Xi’s system of orthodoxy and explained that he succeeded the five thousand years of orthodoxy starting from the legendary rulers Yao, Shun and Yu, to historical personages Tang, King Wen, King Wu, Zhougong, and Confucius. The statement became crucial to Chiang Kai-shek and his government in their effort toward

consolidation and legitimation both Taiwan and in the international arena. […] In Taiwan [Chiang Kai-shek] was the ‘the hero of knowledge,’ the vehicle that rationalized and legitimated this orthodoxy on the island- he was worshipped as the savior of Chinese people” (Pan, 2005: 49).

and Sun Yat-sen24 to make fun of the orthodoxy constructed in Taiwan. By placing Mao’s face in the center of Sun’s, Mei tries to imply that the ROC has already been replaced by the PRC. Hence, the slogan “Three Principles of People unite China” trumpeted in Chiang’s periods becomes ironic and infeasible25. When Li Teng-hui26 (李登輝), the first president elected by the people of Republic of China in Taiwan, resumed his presidency, Mei makes a portrait of Li with Japanese samurai hairdo and use the Japanese Fuji Mountain as the

background in order to produce an image of Li’s personal experience of Japanese colonization (Fig. 11). Li has the experience of living under the Japanese colonial rule for more than 20 years. For him, China being the mother land of Taiwan is an unacceptable concept before Taiwan restoration27. His image in the portrait, though, is not deformed. All the original features of his are kept and the portrait looks just like him.

There are dissimilarities between Mei’s portraits and Wu’s portraits when they are dealing with the political icons. Unlike Mei’s figures that are symbolically deformable, Wu’s grotesque portraits are expressionistically deformable. After Wu’s reproduction, Mao, Deng and the Chiangs look different from what they are in the photos. Moreover, Mei produces his pictures based on the real photos. Although Li looks just like what he is in the portrait, there are supportive decorations or texts in the portrait (Fig. 11) to assist Mei to present his ideas. In contrast, Wu completes his series of the political icons all by the method of traditional

oil-painting. Despite their differences in style and political ideas, their works combine both “national heroes” and “public enemies” to “indicate[s] that the authoritarian era had collapsed, and it was inevitable that the mystique and cult of personality surrounding such leaders would

24 Generally speaking, Dr. Sun Yat-Sen is esteemed to be the founding father of Republic of China before the

split.

25, Tai-sung Chen, “Mei Dean-E’s Political Iconography,” Displacement: Mei Dean-E Solo Exhibition (Taipei:

Museum of Contemporary Art. 2003) 42.

26 Li has his education under Japanese colonial rule, and experiences the restoration of Taiwan after WWII. 27 Pan An-yi, “A Moving Memory: A Special Exhibition of Contemporary Taiwanese Art,” on-line post, 2006,

The Fine Line in the Between: Humanities and Sciences in the 21st Century Conf., 18 Jul. 2007, <http://mingching.sinica.edu.tw/text/amovingmemory_english.pdf >.

be challenged” (Pan, 2004; 89). Their breakthrough in art works “can be regarded as an omen signifying the ending of the period of ‘grand-narrative’ period, and can be seen in artistic attempts to de-deify, de-mystify, and humanize the so-called Great Men” (Pan, 2005; 44). There is another example which is Guo Jen-Chang’s (郭振昌) painting of the president and the vice president (Fig. 12). It is much later published than the works of Wu’s and Mei’s works, but it is more like the make-up of the masks in Chinese opera that Wu’s Four Eras is also referred to. Guo shares the same idea with Wu to mix the sacred images with the folk elements. However, his works are not as grotesque as Wu’s. The Chinese opera masks worn by Guo’s figures almost cover the whole faces. The viewers can not recognize which

president or vice president the icon is in Guo’s work (Fig. 12). Although he intends to satirize the political situation in Taiwan, he does not show any comical or ridiculous elements to make his works good example of the grotesque images. The mask-covered faces are referring to the “Taiwanese politicians who ‘speak human language to people and devil’s language to ghosts’” (Pan 117). This is different from the grotesque countenances of the politician in Wu’s works that show the changes and the subjective comments from the artist. Guo puts on the masks to cover the faces of the figures (Fig. 12), but Wu unfolds the masks. According to many

previous and my own interviews, Wu claims that the way he paints these figures is following to their behavior and characteristics. Therefore, the audience can tell the inherent personality from their looks. Among the Taiwanese artists who are dealing with the political issues, Wu is more forthright in his art works which directly display the figures with deformation. In

addition, the grotesque images are nicely presented in Wu’s works that they deconstruct the majesty of the contemporary giants.

The images of political giants are one part of Wu’s exhibition. The frontispiece of

Leviathan (Hobbes, 1651), which is named after the monster in Bible, would be the prototype

according to Hobbes’ inputs. The "politische illustration” (Using illustrations to demonstrate the political situation, in English.) about Leviathan embodies Hobbes’ idea that a nation should be like a giant composed of innumerable people28. It is supported by the absolute power and the social contract, which may correspond to Foucault’s elaboration of the moral monsters, especially of the political monsters—the sovereign. Wu’s series about the rules of the four political leaders is also an example for the political giants. With reference to the half-body portraits, the size of each painting is larger than 250 cm square. However, each figure of in such a huge size has an unbalanced upper body. Everyone has a small head and a huge body which reminds me of the figure Foucault cited. It is the “Ubu-esque” (Foucault 11) which “describes someone who, by his grotesque, absurd, or ludicrous nature, recalls the figure of [Ubu], the play by Alfred Jarry” (28). In the four giant paintings, the social events are clearly inscribed in the body part. The social events inscribed in the body part of the portraits represent the terror which is like what Foucault talks about in the lecture of the moral monsters. To quell a riot, the policemen always exceed the rioters in armed might. It has to be a kind of surplus, so it accomplishes the end to consolidate the power of the authoritarian. Hence, Wu creates his figures with huge bodies, which represent the overwhelming power of the authority and inscribes anonymous crowd in the bodies to recur the events. In each figure’s body part, there are many small army-like people or distorted bodies. Unlike the distinct facial features of these four political icons, the small people painted in the body part are faceless. The countless people shown in Leviathan, the giant, are also faceless. They are the embodiment for Hobbes’ political philosophy, but not the subject for him to discuss the ill treatment they may face. Different from the faceless crowd in Hobbes’ Leviathan, Wu’s faceless people in the portrait of Chiang Kai-shek, or in Tien-an Men Square Event in the portrait of Mao Tse-tung connote how the people suffer in White Terror era. During such

chaotic periods, there are so many victims that the authorities are not willing to release the number of casualties to the public. The contrast between the head and the body part reinforces the traumatic effects of the political oppression through these grotesque images. The viewers perceive the incongruity between the comic form, the warm-color tone and the cureless suppression. As Foucault’s response to the ethnologists’ analyzes about the power shown in the rites and ceremonies, I consider that Wu’s figures “to whom power is given is at the same time ridiculed or made abject or shown in an unfavorable light” do not present “power to be abject, despicable, Ubu-esque or simply ridiculous” (13). To make the authority ridiculous or Ubu-esque is not to “limit the effects of power in archaic or primitive society [,]” but to “[give] a striking form of expression to the unavoidability of power” (13). The works during Wu’s first period respond to Foucault interpretation of power, especially to the power of the

sovereignty. It is the unavoidable power that Wu shows in his portraits, including the portraits of Chinese patriarchal tradition or the icons of the facial close-up. In addition to the huge size of the canvases, the high-contrast color tone and the rough contour in these series reinforce the grotesque of his unusual portraits.

This series discloses the disgrace of the absolute power. The monstrous feature is displayed in the authoritative icons as visualization of the power relations. The leaders’ images have to be despiteful or they can not be presented. Prior to the lifting of the martial law in 1987, tons of great men statues and portraits had been made. The “great men” are restricted to Chiang’s family at that time. Their portraits are hung in every public organization and school. Wu thinks this is the one of the functions of portraits—making viewers feel being monitored. The four sets of political strongmen displayed to the viewers remind people of patriarchal relationships in a family. They replace the traditional patriarchal figures and serve the purpose of surveillance. All these constructs a unique “great-men culture” in Taiwan. The political leaders are molded into national idols or national liberators. People should respect

and worship them as if they were Gods. To challenge and question this kind of value, Wu makes fun of them by distorting their former representations and reconstructs them in grotesque style so that they become his own “great-men portrait.” Wu questions Taiwanese viewers on the concept of democracy by juxtaposing the leaders in Taiwan (Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo) with the ones in China (Deng Hsiao-ping and Mao Tse-tung). As in Foucault’s discussion of the moral monsters, Wu’s works during this period also parody the moral monsters into Taiwanese context.

2.3 Iconographic Study of Wu’s Icon works of Political Strongmen

Another characteristics developed during this period is Wu’s comic-strip style. It is similar to the tradition of caricatures that have facial sketches and the deformation in bold and black lines. They both attempt to use the same sense of humor to provoke the viewers and further manifest the absurdity of political situation (Dong 62). Wu’s iconography is like a “graphic commentary” without any presupposed any political positions. It speaks for most of the people. He considers his own images maladroit compared to the editorial cartoon which aims at ingenious appearance29. He not only makes caricature of the political figures, but also designs his painting carefully. Take the face of each political figure for example. He mixes the personality with his facial features to produce his own political icons which are not just simple cartoon sketches. The faces of the figures in his works do not look the same as the models. Therefore, it gives viewers an impression that the identity of his figures oscillate. As such, Wu claims that the figures in his painting are in a style of his own realism where he creates the figures only by his arbitrariness. The similarity that his works share with the editorial cartoon is that they both comment on social issues and political figures, government official in particular. In addition, their images have a common feature that they are easy for

the readers or viewers to understand. The funny subjects shown in the caricatures are

constituted by the ridiculous, asymmetrical and disproportional drawing, which is one of the sources of Wu’s grotesque images.

In the huge-size facial close-up portraits in the exhibition of Four Eras (Fig.6-9), he does not paint realistically, but exaggeratedly. Overstating the details of each face in order to focus on the facial expressions of the four political leaders, he tries to record the transformation of them in four pictures. However, some critics associate him with the Pop Art icon of Andy Warhol. Wu comments that he is not satisfied with it. Andy Warhol indeed gives him some inspiration, but the conceptions are different30. Warhol’s famous block-print works of celebrities, such as Marilyn Monroe, are aiming at reflecting the consumer society. It is the commodified object that he wants to show. Another important point that differs Wu from Warhol is that his icons have a profound relation with the Chinese literary tradition. Wu stated that he tried to borrow the method of the biographical writing in history to exhibit the

exaggerated facial expressions. The grotesques of these works are connected with ancient physiognomy. What the political strongmen look like results from what they are thinking and how their behaviors are. Wu calls it “Biographic Realism”(「傳記繪畫寫實主義」) (Pan 88). Despite the idea from the Chinese literary tradition, Wu also shows his icon with the types of facial makeup in Chinese opera, which enhances the visual impact. In the tradition of the facial makeup in Chinese opera, the colors and the lines on each face are clear-cut and full of meanings. The most representative of the red color on the mask is Kuan Yu (關羽) during the period of the Three Kingdoms (A.D. 220-280), and it stands for the royalty and bravery. White color indicates scheming and treacherousness; for instance, Tsau Tsau (曹操) during the period of the Three Kingdoms and Chin Kuai (秦檜) in Sung Dynasty (A.D. 960- 1279). Black mask in Chinese opera symbolizes the character of fierceness or impartialness which

30 Yi-chung Lu, “Tumbling in the Wave of History: The Four Eras of Wu Tien-chang’s Iconology,” Lion Art

can be found in Chang Fei (張飛) during the same period. Therefore, the intention of Wu’s icon is getting obvious. These three colors, red, white and black, are the main tones for the political icons. Wu grasps the meaning of these colors to make allegoric evaluations of the four “great-men,” and it is his intention to criticize their merits and demerits. Besides,

different from Andy Warhol’s celebrity icons, it is evidential that Wu utilizes the techniques of caricature to convert the authoritative figures into the easy ones to access. Wu does not keep the outlines of the photographs; instead he reconstructs the portraits as caricatures. Even so, Wu’s conception about political icons still strikes the viewers because their faith constructed by the authority is reconstructed again. Now the viewers can be aware of the myth that there is no God-given or god-like leader as before.

Wu’s iconoclastic paintings during the period when martial law is being lifted in Taiwan are the necessary steps to start contemporary arts in Taiwan. I consider his grotesque icon a successful device to express his critical vision about the contemporary social conditions in Taiwan. Four Eras is a series of four pictures as each represents a leader’s attitude toward a specific social event. The leaders may not be the brilliant heroes we know of from the

textbooks or some official propaganda; in some special social events, the political leaders are just like the abnormal people or the moral monsters that only care about themselves. Wu’s grotesque images attempt to eliminate the sacred elements from political portraits and also form a force against the elite and upper-class culture and art. He provides an opportunity for the audience to touch upon the political issues which used to be brought up only in a very serious way. During this period, Wu builds up his unique style by making the four leaders shown in grotesque appearances. Although he cares about the social issues so much that he creates this series to speak for the people, he does not have any work about the folk during

this period; he has only used grotesque to recapture the political figures. Wu uses the grotesque images of the leaders as the overture of his grotesque carnival series. The images successfully depict the four leaders; however, there is nothing about the transgression power of the civilians shown during this period. It was not until the second period that the grotesque images of the civilians can be seen. In the next chapter, I will analyze the images and adopt supportive theories to distinguish their differences.