Chapter Four Results and Discussion

In this chapter, the results are reported to demonstrate the differences between

the pretest and posttest after the application of the story-mapping instruction. The

main findings include the quantitative results on word count, writing performance,

story grammar units, writing apprehension and students’ response to the

story-mapping instruction. The qualitative results on students’ opinions toward

story-mapping instruction are also presented. Besides, the discussion of the results is

included.

4.1 Comparison of Word Count between the Pretest and the Posttest

The first research question addressed in the present study focuses on the content

length of the stories in the pretest and the posttest. The main concern is if the

participants could write more after receiving the instruction.

●

Results

Table 7 summarizes the average length of the stories in the pretest and posttest.

In Table 7, the result shows that the participants did write a longer story after the story

mapping instruction. The mean score of the students’ word count significantly

increased by 105.19 words (Pretest: 77.89; Posttest: 183.08). Before the

story-mapping instruction, the participants typically produced relatively short and

incomplete stories of poor quality. The average length of their stories was only

77.89-word long, which was relatively short for senior high school students. After

learning the story-mapping writing strategy, all the participants wrote stories almost

two times longer.

Table 7

A T-test of Mean Scores on Word Count in the Pretest and Posttest (N=76)

M SD t-value

Pretest Posttest

77.89 183.08

26.49

73.89 13.69**

Note. * p<.05, ** p<.01, M=Mean, SD=Standard Deviation

●

Discussion

The results showed that the participants wrote longer stories after the

story-mapping instruction, with 105.19 words longer. The similar results could also be

found in Saddler, et al. (2004). In their study, the students’ stories were 2.5 to 7 times

longer after learning the story mapping strategy. However, their study focused on the

effects of the story-mapping on the students with learning disabilities. The results here

demonstrated that the instruction had the same positive effects on the average EFL

students. Noyce & Christie (1980) indicate that the prior knowledge of a story, that is,

the story schema, serves as the source of the content of writing. With the framework

of a story, writers would have more to write about. The statistical results showed that

the knowledge of the story structure helped the participants compose longer stories

with more details.

4.2 Comparison of Writing Performance between the Pretest and the Posttest

The second research question addressed in the present study centers on the

improvement of the content and organization of the participants’ writing performance

between the pretest and the posttest.

●

Results

The results shown in Table 8 indicate that there was significant difference of the

participants’ writing score between the pretest and posttest. The mean score of overall

writing performance increased (Pretest: 6.34; Posttest: 11.17). The increase of mean

scores in overall writing performance and five measured components were significant

(t=11.226**, 11.025**, 11.630**, 10.220**, 7.751**, 6.885**, respectively, p<.01).

Additionally, the increase of mean score change for “Organization” (+1.35) was most

remarkable, followed by “Content” (+1.23), “Vocabulary” (+1.07), “Grammar”

(+0.86), and “Mechanism” (+0.44).

Table 8

A T-test of Mean Scores on Writing Performance in the Pretest and Posttest N=76

Pretest Posttest t-value

M SD M SD

Content 1.86 .73 3.09 .94 11.03**

Organization 1.45 .72 2.80 .98 11.63**

Vocabulary 1.32 .62 2.39 .90 10.22**

Grammar 1.09 .77 1.95 .82 7.75**

Mechanism 0.51 .50 0.95 .32 6.89**

Overall Writing Proficiency 6.34 3.08 11.17 3.5 11.23**

Note. * p<.05, ** p<.01, M=Mean, SD=Standard Deviation

●

Discussion

The results demonstrate that after the story mapping instruction, the students did

make improvement in organization and content in their compositions. The results

positively answer the second research question: Do the participants have better

content and organization in their compositions after story-mapping instruction?

They confirm the first research hypothesis: The learners who undergo the

story-mapping instruction improve significantly in the content and organization of

their writing. One may argue that it was the maturation effect that made the students

improve their writing performance. However, this line of reasoning cannot fully

explain why organization is the most remarkable among all the categories of writing

performance. In fact, such improvement follows naturally from the proposal that the

story-mapping instruction assists the students in writing performance. After receiving

the concept of story schema and having the story structure in mind, the students

constructed and organized the story map before they wrote, which helped compose a

story with better organization. The improvement of organization indicates that the

improvement of writing performance was not totally influenced by the maturation

effect. The finding is supported by other studies, including Brown (1988), Fitzgerald

& Teasley (1986), and Hsu (2001). In their studies, the participants also made

improvements in content and organization in their compositions after the

story-mapping instruction. The similarity of the results of the related research shows

that story mapping, an organized, schematic writing strategy, helps students generate

stories with better organization and richer content.

It is worth noting that the participants made significant improvement not only in

“Content” and “Organization,” but also in “Vocabulary,” “Grammar,” and

“Mechanism.” One may wonder why the students also made progress significantly in

these three aspects. This may be explained from the qualitative results. In the

interview, when asked why they could write with richer vocabulary, more correct

grammar, and better mechanism, the participants said that they learned a lot from the

selected articles. Besides, they became more sensitive to the way that writers

described a story. For example, they used more adjectives and rhetorical devices to

describe a main character instead of just giving it a name. Through the story-mapping

instruction, the students not only learned the structure of a story, but also became

aware of word usage and grammar.

4.3 Comparison of the Number of the Story Grammar Units between the Pretest

and the Posttest

The main concern of the third research question is whether the participants

significantly write more story elements in their stories after receiving the story

mapping instruction.

●

Results

In Table 9, the mean score of the number of the story grammar units increased

(Pretest: 5.05; Posttest: 7.33). The increase of mean score was significant (t=13.621**,

p<.01). In the present study, a well-constructed story included eight story grammar units. Before the story-mapping instruction, the participants could write a story with

5.05 story grammar units. After the instruction, the stories that the participants

composed contained 7.33 story grammar units, which was a significant improvement.

Table 9

A T-test of Mean Scores on SG Number in the Pretest and Posttest (N=76)

M SD t-value

Pretest Posttest

5.05 7.33

1.58

.87 13.62**

Note. * p<.05, ** p<.01, M=Mean, SD=Standard Deviation

●

Discussion

The results of the comparison of the number of story grammar units between the

pre-test writing and the post-test writing support the findings reported in the previous

research (Harris & Graham, 1992; Vallecorsa & deBettencourt, 1997; Graham &

Harris, 2004). In their studies, the students made improvement in the number of the

story elements included in their stories. One might wonder why the participants could

write a story with 5.05 story grammar units before the instruction. According to

Noyce & Christie (1989), most stories share the same, predictable basic structure or

pattern of events that create the properties of a story. Most children possess this

organizational similarity consciously or unconsciously. This can be explained why the

participants could write a story of some basic story grammar units without the

story-mapping instruction. Despite the fact that some participants could write a

roughly-constructed story, many of them failed to write a story with all story elements.

After receiving the story-mapping instruction, the participants made significant

improvement in writing more story elements. These positive results indicated that the

story schema instruction benefited the story writing. Foley (2000) indicates that while

writing stories, writers retrieve the information from the story schema. Given the

explicit instruction of the prior knowledge of a story, inexperienced writers can

generate stories with more story grammar units, which may lead to better-constructed

stories.

4.4 Comparison of Story Grammar Units between the Pretest and the Posttest

The main concern of the fourth research question is whether the participants can

write more well-constructed stories after receiving the story mapping instruction. To

be more specific, we would like to know if the participants can get significantly

higher score of the story grammar in their stories.

●

Results

In Table 10, the mean score of the overall story grammar unit increased (Pretest:

5.50; Posttest: 10.29). The increase of mean score in overall story grammar units was

significant (t=17.715**, p<.01). Besides, the participants made the most progress in

the “Action” (+0.99), followed by “Character” (+0.85), “Goal” (+0.71), “Reaction”

(+0.65), “Starter” (+0.56), “Locale” (+0.45), “Time” (+0.42), and “Ending” (+0.15).

All story grammar units reached a significant level (p<.01). Among the 8 story

grammar units, the students preformed best in the “Action” and “Character.”

Table 10

A T-test of Mean Scores on Story Grammar Units in the Pretest and Posttest N=76

Pretest Posttest t-value

M SD M SD

Character 1.03 .28 1.88 .54 13.35 **

Locale 0.54 .50 0.99 .31 7.08 **

Time 0.57 .50 0.99 .26 7.02 **

Starter 0.86 .35 1.42 .55 7.98 **

Goal 0.54 1.21 1.25 .44 4.75 **

Action 1.18 .48 2.17 .82 10.05 **

Ending 0.82 .42 0.97 .61 2.10 **

Reaction 0.13 .34 0.78 .74 7.07 **

Overall SG 5.50 1.89 10.29 2.53 17.72 **

Note. * p<.05, ** p<.01, M=Mean, SD=Standard Deviation

●

Discussion

The results of the comparison of story grammar units between the pre-test

writing and the post-test writing support the findings reported in the previous research

(e.g., Fine, 1991). Fine indicates that providing the students with the direct instruction

of story grammar helps them improve each of their story grammar units. The positive

results shown in the present study demonstrate that with the assistance of story

mapping strategy, the students have better knowledge of story structure and have the

ability to compose stories with more improved story elements and details. The

researcher found that the participants had the ability to write more actions and create

more episodes in their stories after receiving the story-mapping instruction. That was

a significant improvement because the stories written in the posttest appeared to have

more creative and coherent actions. Furthermore, the participants described the main

characters in greater detail with respect to the characters’ physical appearance,

characteristics and feelings after receiving the explicit story mapping instruction. The

results positively answer the fourth research question: Do the participants write more

well-constructed stories after the story-mapping instruction? The results also support

Gambrell and Chasen (1993), who advocated that explicit story instruction could

improve the student’s narrative writing. It is shown that when the students are

provided with instruction which offered them a distinct organizational structure, they

are more likely to internalize this structure for use in the writing development of

narrative stories. The results also echo Hagood’s (1997) finding that when learners

were provided with detailed, explicit, and repetitive experiences in analyzing and

manipulating story grammar, they could internalize a simple story structure.

4.5 Results of the Most Difficult and Easiest Story Grammar Units

The concern of the fifth research question is to find out which story element is

the most difficult for the participants to manipulate in the pretest and the posttest and

which one is the easiest to them.

●

Results

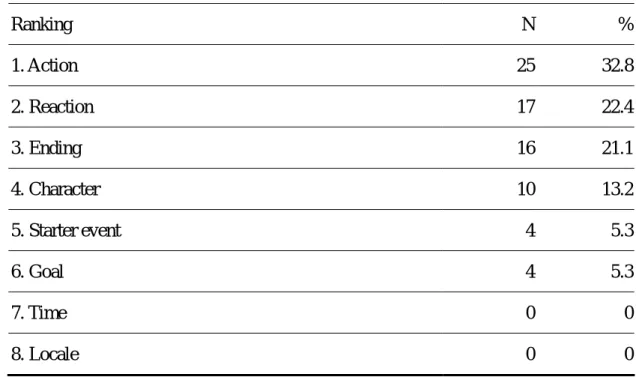

Table 11 shows the results of the most difficult story element to students based

on the questionnaire. 32.8% (N= 25) of the students reported that they had problems

with “Actions,” 22.4% (N= 17) “Reaction,” and 21.1% (N= 16) “Ending.”

Table 12 shows the results of the easiest story element to students based on the

questionnaire. The majority of the participants (81.6%) thought the setting of a story

was relatively easier to them in comparison with other story grammar units. To be

more specific, 39.5% (N= 30) of the participants regarded “Characters “as the easiest

story element to manipulate, 22.4% (N= 17) “Time” and 19.7% (N= 15) “Locale.”

Table 11

The Number and Percentage of Story Grammar Units Which the Students Thought to Be the Most Difficult to Them (N=76)

Which story grammar unit is the most difficult to you?

Ranking N %

1. Action 25 32.8

2. Reaction 17 22.4

3. Ending 16 21.1

4. Character 10 13.2

5. Starter event 4 5.3

6. Goal 4 5.3

7. Time 0 0

8. Locale 0 0

Table 12

The Number and Percentage of Story Grammar Units Which the Students Thought to Be the Easiest to Them (N=76)

Which story grammar unit is the easiest to you?

Ranking N %

1. Character 30 39.5

2. Time 17 22.4

3. Locale 15 19.7

4. Action 12 15.8

5. Starter event 1 1.3

6. Goal 1 1.3

7. Ending 0 0

8. Reaction 0 0

●

Discussion

After the direct story-mapping instruction, the students made improvement in all

story grammar units. However, “Reaction” and “Ending” appeared to be difficult for

some students to manipulate. Based on the results of the interview, the researcher

summarizes two possible answers to account for why the students could not master

“Reaction” and “Ending.”; that is, picture aid and time constraint. The students who

found “Ending” difficult said that “Ending” was relatively hard to them because they

had to work out the ending of a story without the help of the picture. They said that

they could write based on the given pictures, but it was hard for them to come up with

the ending and reaction without the assistance of pictures. The results echo the finding

of Chiang (2003). Chiang indicates that pictures can be used as a powerful tool to

move students from visual images to the written language and thus enable them to

write more about the topic. The other reason to explain why they could not finish their

“Ending” and “Reaction” with ease was the time constraint. Many of the students

could not manage time well. They spent too much time on the story map and did not

leave enough time to make a well-developed “Ending” and “Reaction”. According to

the interview, some students noticed the problem of time management. They said they

spent 20-30 minutes making the story map and wrote their stories hurriedly. They

expressed that the experience taught them a lesson; that is, they should limit the time

of prewriting activity to 5 to 15 minutes.

Before the instruction, although most participants could manipulate “Character”

and “Action”, the character in their stories was only a name without detailed

description. The “Actions” in most students’ stories were few and lacked coherence.

After the instruction, most students could create characters with vivid description and

actions with rich content and coherence. Fine (1991) reported the similar result. In her

study, the participants also better understood and could manipulate “Character”,

“Setting”, and “Plot” after direct instruction of story grammar.

Although most students could manipulate “Action” in the stories of the posttest,

25 students reported they had difficulty with “Actions” in open-ended question of the

questionnaire. They found it challenging to come up with a creative and logical plot.

They were worried that their plot might be too “ordinary”; therefore, they tried hard to

make their stories as imaginative as possible. That was why they found the “Action”

hard. That was an interesting finding. Some of the teenagers were unwilling to follow

the instruction to write a logical and reasonable plot and ending; instead, they liked to

“impress” the readers by creating special “Actions” and a surprising “Ending.” The

majority of the participants could not write a logical or reasonable ending. Because

they would like their stories to be special, they tended to write a “surprising” ending.

However, the surprising endings they made were always nonsense or ridiculous. The

Chinese teacher of the participants indicated that she also noticed the same problem,

that is, students nowadays do not have the habit of extensive reading. Since the

students read too little, they lack the ability to compose a well-organized story with a

reasonable ending. Besides, the subculture of the teenagers makes the students

consider a “surprising ending” cool and impressive.

The other concern of the fifth research question is : what is the easiest story

element to students? Based on the results of the questionnaire, the majority of the

participants (81.6%) thought the setting of a story, including “Characters”, “Locale”,

and “Time”, was relatively easier to them in comparison with other story grammar

units. The students pointed out that the three story elements were relatively more

concrete ideas to them than the rest. Also, they found the given pictures provided

them with the idea of the setting.

4.6 Correlation of Score of Story Grammar, Writing Performance and Word

Count

The main concern of the section is to find out if there were any correlation

between the story mapping strategy and writing performance, that is, if there were any

correlation among the score of the story grammar, writing performance and word

count in the students’ picture writing.

●

Results

Research on the story-mapping instruction seldom reported the correlation

between the story mapping strategy and writing performance. In the present study, the

researcher made an investigation of the correlation among the story grammar units,

writing performance and word count. Table 13 shows a strong correlation among the

score of story grammar, that of the writing score and number of the word count. The

correlation between the score of story grammar and that of the writing proficiency

is .833**; the correlation between the score of story grammar and word count

is .675**; the correlation between the score of writing proficiency and that of the

word count is .569**. The results all reached a statistically significant level set at p

< .01.

Table 13

A Correlation-test of Mean Scores on Story Grammar Units, Writing Performance and Word Count (N=76)

SG Writing Performance Word count

SG 1 .83(**) .68(**)

Writing Performance .83(**) 1 .57(**)

Word count .68(**) .57(**) 1

** Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed).

●

Discussion

Based on the results of the correlations test, the story-mapping instruction did

significantly have a strong correlation with students’ writing performance and the

length of their stories. In addition, the correlation was positive rather than negative

since the statistic results of word count, story grammar units and writing performance

showed improvement in the participants’ writing. The results showed that after the

participants were taught the story-mapping strategy, the basic story elements in their

stories increased, their writing performance improved, and their compositions became

longer.

4.7 Comparison of Writing Apprehension between the Pretest and the Posttest

The sixth research question addressed in the present study focuses on the writing

apprehension. The main concern is whether or not the participants can reduce their

writing anxiety after receiving the instruction.

●

Results

In Table 14, there was a statistically significant difference in the participants’

response to SLWAT between pre-test and post-test. The mean score of the overall

writing apprehension decreased (Pretest: 80.76; Posttest: 71.17). The change reached

a significant level (t=7.376**). Among 26 items, only 7 items (Item 3, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15,

19) failed to make a significant change. Among the total 26 items, the participants

made significant difference in 7 of the 13 items written in a positive statement and 12

of the 13 items written in a negative statement. The details are as follows.

●

Positive items that reached a significant level:

Item 2. I have no fear of my English writing’s being evaluated.

Item 6. Handing an English composition makes me feel good.

Item 11. I feel confident in my ability to express my ideas clearly in English writing.

Item 12. I like to have my friends read what I have written in English.

Item 17. English writing is a lot of fun.

Item 20. Discussing my English writing with others is enjoyable.

Item 23. It’s easy for me to write good English compositions.

●

Negative items that reached a significant level:

Item 1. I avoid writing in English.

Item 4. I am afraid of writing English essay when I know they will be evaluated.

Item 5. Taking an English composition course is a very frightening experience.

Item 7. My mind seems to go blank when I start to work on my English composition.

Item 13. I am nervous about English writing.

Item 16. I never seem to be able to write down my ideas clearly in English.

Item 18.I expect to do poorly in English composition classes even before I enter them.

Item 21. I have a terrible time organizing my ideas in an English composition course.

Item 22. When I hand in an English composition, I know I am going to do poorly.

Item 24. I don’t think I write English composition as well as most other people.

Item 25. I don’t like my English compositions to be evaluated.

Item 26. I’m not good at English writing.

Table 14

A T-test of Mean Scores on Writing Apprehension in the Pretest and Posttest N=76

Pretest Posttest t-value Items

M SD M SD

1. I avoid writing in English. 3.25 .79 2.82 .98 3.48*

2. I have no fear of my English writing’s being evaluated

2.74 .93 2.38 1.01 2.69*

3. I look forward to writing down my ideas in English.

2.58 .85 2.43 1.02 1.13

4. I am afraid of writing English essay when I know they will be evaluated.

3.01 1.05 2.46 .92 4.825*

5. Taking an English composition course is a very frightening experience.

2.68 .97 2.21 .88 4.131**

6. Handing an English composition makes me feel good.

2.96 .74 2.18 .91 6.851**

7. My mind seems to go blank when I start to work on my English

composition.

3.16 1.12 2.51 1.01 4.009**

8. Expressing ideas through writing in English seems to be a waste of time.

2.37 .81 2.30 .90 .638

9. I would enjoy submitting my English writing to magazine for evaluation and publication.

3.45 .89 3.61 2.37 .552

10. I like to write down my ideas in English.

3.18 .69 2.99 1.03 1.687

11. I feel confident in my ability to express my ideas clearly in English writing.

3.68 .84 3.39 1.06 2.390*

12. I like to have my friends read what I have written in English.

3.21 .85 2.71 1.02 3.833**

13. I am nervous about English writing. 3.25 1.03 2.57 .10 4.747**

14. People seem to enjoy what I write in English.

3.36 .73 3.25 .85 .929

15. I enjoy English writing. 3.09 .80 3.03 1.01 .672 16. I never seem to be able to write down

my ideas clearly in English.

3.28 1.05 2.00 1.06 2.161*

17. English writing is a lot of fun. 2.64 .80 2.33 .87 3.018*

18. I expect to do poorly in English composition classes even before I enter them

3.28 .97 2.58 1.11 4.727**

19. I like seeing my thought on paper in English.

2.82 .81 2.75 .93 .583

20. Discussing my English writing with others is enjoyable.

2.80 .90 2.50 .81 2.620*

21. I have a terrible time organizing my ideas in an English composition course.

3.08 .99 2.64 .92 3.650**

22. When I hand in an English

composition, I know I am going to do poorly.

3.21 .94 2.61 1.05 5.535**

23. It’s easy for me to write good English compositions.

3.74 .79 3.20 1.12 4.138**

24. I don’t think I write English composition as well as most other people.

3.41 .91 3.03 1.02 2.508*

25. I don’t like my English compositions to be evaluated.

2.80 .86 2.28 .83 5.090**

26. I’m not good at English writing. 3.78 .90 3.32 1.01 3.647**

Overall WA Performance 80.76 12.80 71.17 14.22 7.376**

Note. * p<.05, ** p<.01, M=Mean, SD=Standard Deviation

●

Discussion

The results positively answer the sixth research question: Do participants reduce

their writing apprehension after receiving the story-mapping instruction? They also

verify the third hypothesis: The learners who undergo the story-mapping instruction

will write with less anxiety and with more confidence. The students made positive

change significantly in 21 of the 26 items.

As mention in sections 2.1.1 and 2.3.2.3, the results of Becker’s (1991),

Schweiker-Marra & Marra’s (2000), and Huang’s (2003) also showed that the

students could write with less apprehension when provided with prewriting activities.

Harris and Graham (1992) also indicated that after receiving the story-mapping

instruction, most of the students felt comfortable with writing. The results in the

present study demonstrated that if the instructor provided the beginning EFL writers

with the concept of writing process, appropriate prewriting activities, and the schema

of the genre, the young writers could decrease the writing apprehension, the negative

impact on students’ writing performance and attitude toward language learning.

Although the overall writing apprehension of the students decreased, the students

still expressed their fear in writing English in 7 items, which needed to be further

discussed. First, the participants still felt reluctant to submit their writing to the

magazine for the evaluation and publication (Item 9) and were not certain if others

like their English writing (Item 14). However, they would like to share their writing

with their friends (Item 12). That means teenagers feel more comfortable to discuss

their English writing with their peers than with others they are not familiar with.

Second, the students reduced their writing apprehension after receiving the instruction,

they did not have a very positive attitude toward expressing themselves in English.

(Item 3, 10, 15, 19).

There are two findings that seem to be concerned with the design of the

questionnaire. One is that the participants appeared to answer negatively when the

items were written in a positive statement. The results showed that the participants

made more significant change in items written in a negative statement than in a

positive statement. Wang (2000) reported similar finding. She points out that the

phenomenon might result from the fact that Chinese students are conservative and are

taught to be humble.

The other finding is that most students seemed to choose the “neutral” answer

most in each of the 26 items. From the interview, the students said that they were not

accustomed to strongly expressing their likes or dislikes. Therefore, only some

students circled the square “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree.” As Wang (2000)

suggested, it is necessary for other researchers to adapt the SLWAT to meet the needs

of Taiwanese population. To eliminate the middle uncertain position, the SLWAT can

be slightly adapted for ESL population using a 6-point scale, with “neutral” being

changed into “agree somewhat” and “disagree somewhat” (Wang, 2000).

Based the results of the writing apprehension test, the overall writing

apprehension of the participants did make a significant positive change after the

story-mapping instruction. This prewriting activity did help the participants reduce the

writing anxiety and increase their confidence in writing.

4.8 Results of the Students’ Response to the Story-Mapping Instruction

The seventh research question focuses on the students’ attitudes towards the

story-mapping instruction. The results of the questionnaire are presented below in

percentage form. The students’ responses to the story-mapping instruction are based

on the questionnaire and the interview.

●

Results

Table 15 displayed the results of the questionnaire on the story mapping

instruction. The results revealed that the majority of the students strongly liked or

liked the story mapping instruction (Item 1, 86.8 %). They also reported that

story-mapping instruction helped them understand story structure (Item 2, 97.3 %),

provided them with more ideas to write about (Item 7, 93.4 %), and improved their

English story writing (Item 3, 94.8 %) and writing performance (Item 4, 92.1 %). The

results on writing apprehension were also satisfying. The majority students agreed

that story mapping helped enhance their confidence in writing (Item 5, 81.6 %) and

reduced their writing apprehension (Item 6, 73.7 %). Additionally, the students also

thought the story mapping instruction enhanced their reading comprehension (Item 8

& 9, 82.9 % and 92.3 % respectively) because it provided them with the knowledge of

story structure, which helped them predict the development of stories and have a

better reading comprehension.

Table 15

The Percentage of Items on the Response to the Story Mapping Instruction N=76

Item Strongly

disagree &

disagree

No comments

Strongly agree &

agree

N % N % N %

1. I like story mapping instruction. 5 6.6 5 6.6 66 86.8 2. Story mapping instruction helps me

understand the story structure.

1 1.3 1 1.3 74 97.3

3. Story mapping instruction helps me with English story writing.

1 1.3 3 3.9 72 94.8

4. Story mapping instruction helps me with English writing.

4 5.3 2 2.6 70 92.1

5. Story mapping instruction lets me have confidence in English story writing.

10 13.1 4 5.3 62 81.6

6. Story mapping instruction reduces my writing apprehension.

15 19.7 5 6.6 56 73.7

7. Story mapping instruction lets me have more ideas to write about.

2 2.6 3 3.9 71 93.4

8. Story mapping instruction helps predict the development of stories and improve my reading ability.

5 6.6 8 10.5 63 82.9

9. Story mapping instruction helps me comprehend stories better and improve my reading ability.

6 7.9 9 11.8 61 90.3

Based on the questionnaire, the researcher interviewed the students to elicit

more responses. When interviewed, most students said that they enjoyed reading,

analyzing, and creating stories during the 6 weeks of instruction. They considered the

story-mapping instruction a systematic learning strategy that offered them the schema

of the story structure. With the story schema, they comprehended and composed

stories more easily and confidently. The three positive responses to the story-mapping

instruction are summarized as follows.

●

Most students recognize the story mapping instruction a non-threatening,

enjoyable activity.

S402: I used to be afraid of English writing because I totally didn’t know what to write about when I faced the topic. The concept of story grammar helps me realize story writing could be an unproblematic task.

S411: I agree with you. After the story mapping instruction, I find story writing an enjoyable task. I can create my story step by step, which makes me have more confidence in my ability.

S306: I like the feeling of get everything set and done as planned. I find that once the story structure is planned, writing stories becomes a relatively unproblematic and easy

task for me.

●

The story-mapping instruction is a useful prewriting activity, which helps

students organize their stories.

S328: Before the instruction, I didn’t plan in advance of writing. Now, I would make a

story map before I write my story. I think the map helps a lot because I find I have

better organization in my story. I really make improvement in story writing.

S316: Now, I am accustomed to making a plan before I write. I would spend about 5 to

10 minutes writing down the story outline to have a general framework of the story

and then write my story down in details. The instruction helps me work out an

outline of a story efficiently and makes me feel more confident.

●

The story-mapping instruction helps with reading and writing

S422: I have more to write about with the help of story maps. Besides, I think I write

with better organization and coherence instead of writing whatever come to my

mind.

S441: I agree. I could write more after the instruction. When writing based on the story

maps, I could generate more ideas and compose longer and imaginative stories.

S433: I enjoy analyzing stories. The story grammar helps me comprehend stories more

easily. Now when I read stories, I would try to find out the characters, time, actions,

ending, etc. I also try to predict what might happen next. I think it is an excellent

training for us.

S311: It also helps me in analyzing Chinese stories. I try to apply the concept of the story

grammar to Chinese stories and I find it works. I find it very interesting to analyze

stories this way. I think I might try to write Chinese stories with a story map.

●

Discussion

The positive responses were in accordance with the findings in Brown (1988);

that is, the story-mapping instruction benefits not only reading but also story writing.

In the present study, the students expressed they liked the story-mapping instruction

since it helped increase their writing performance and confidence. The positive

responses of the students argued against the maturation effects playing a crucial role

in the improvement of the students’ writing performance. The quantitative results of

writing organization and qualitative results of students’ responses confirmed the

proposal that the story-mapping instruction helped the students organize their stories.

The students’ responses supported the concept of schema, metacognition and

reduction. Once the students were familiar with the concept of the story schema, they

could use the story schema to generate their stories with ease. Advocates of

metacognition believe that learners can learn better and with ease if they are aware of

what they are doing and know what to do next step by step. Furthermore, the

reduction theory, which holds that breaking the complex process down to easy pieces

makes a task easy, is in agreement with the students’ responses.

Although the present study focuses on writing, the majority of the students

applied the knowledge of story grammar to reading stories, both in English and

Chinese. The participants This phenomenon of applying the knowledge of story

structure to Chinese reading and writing was beyond the teacher’s expectation and has

not yet been mentioned in the previous studies. The participants also expressed that

they enjoyed analyzing stories, trying to find out the story grammar units in stories

they read. Furthermore, they indicated that knowing the story-mapping strategy

helped them comprehend stories better. The concept of story grammar even helped

them predict what might happen next in the stories they read.

To be brief, the story-mapping instruction helped the students with their reading

comprehension. The result showed that reading and writing are strongly connected.

Only when the students read extensively can they write compositions with rich

content.

4.9 Results of the Six Open-ended Questions and Interviews

The main concern of the open-ended questions and interviews is to elicit more

responses from the students regarding the story-mapping instruction and story writing.

The items of the questionnaire are presented below with the result in percentage form.

The students are required to answer each question with one single answer, which

means that they can not answer each item with more than two or more answers.

Question 1: Which part of the story mapping instruction do you like most? Why?

The first item in the questionnaire is to determine which part of the

story-mapping instruction the participants liked best.

●

Results

As shown in Table 16, 34.2% of the students enjoyed writing the story based on

the story map, 21.1% enjoyed receiving the teacher’s comments on the story, another

21.1% enjoyed analyzing the story structure of the selected articles, 14.5% enjoyed

making the story map based on the given pictures, and 9.2% enjoyed sharing the story

map and stories with others.

Table 16

The Number and Percentage of the Part of the Instruction the Students Like Best N=76

1. Which part of the story-mapping instruction do you like best?

N %

Writing the story based on the story map 26 34.2%

Analyzing the story structure of the selected articles 16 21.1%

Receiving the teacher’s comments on the story 16 21.1%

Making the story map based on the given pictures 11 14.5%

Sharing the story map and compositions with others 7 9.2%

●

Discussion

There were 26 students that indicated that they loved the process when they did

their own stories based on the story maps. They pointed out that the story map helped

them generate more ideas and be more creative in writing stories and feel more secure

about their writing. For example, some students said that they liked to use their

imagination to compose their own stories based on the story map. It was cool and

interesting (S437, S402, S436, S316, S324). S302 remarked, “ I like the story map

because it can help me construct my story step by step, which makes me feel more

secure. I learn to think about the plot of a story after receiving the instruction.” The

responses support the Metacognition theory as proposed by Lytle & Botel (1988).

When the students became consciously aware of what they were doing and the

process of the task, and took strategic control over it, they would have more

confidence in the task.

Furthermore, 16 students reported that they enjoyed the process of analyzing

the stories with the teacher because they could have a better picture of the story

structure, which they considered beneficial to their reading and writing. For example,

S304 said that she enjoyed the story analysis because she learned about what should

be included in a story and how the story map could help the story composing.

Additionally, 16 students pointed out that they were excited when receiving the

teacher’s comments on their stories. They said they were eager to know the teachers’

comments on their stories because the comments helped them know how they could

improve their stories and the teacher’s encouragement made them feel confident. In

addition, they liked to share their stories with others because they could learn a lot

from others’ composition and creativity. S411 indicated that she enjoyed the

comments that the teacher gave her and that she could make revision based on the

teachers’ suggestion. Given such feedback from the students, it is suggested that the

EFL writing instructor give positive and constructive advice on writing instead of the

grammar correction. Peer evaluation is also recommended.

Question 2: Which part of the story mapping instruction do you dislike most?

Why?

The second item in the questionnaire is to determine which part of the

story-mapping instruction the participants dislike most.

●

Results

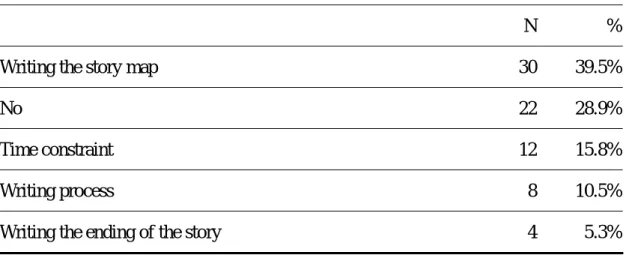

Table 17 showed the four aspects of the story-mapping instruction that the

participants disliked most, including writing the story map (39.5%, N= 30), writing

process (15.8%, N= 12), time constraint (10.5%, N= 8) and writing the end of the

stories (5.3%, N= 4). 28.9% of the students did not report dislikes of any specific

aspect of the instruction.

Table 17

The Number and Percentage of the Part of the Instruction the Students Dislike Most (N=76)

2. Which part of the story-mapping instruction do you dislike most?

N %

Writing the story map 30 39.5%

No 22 28.9%

Time constraint 12 15.8%

Writing process 8 10.5%

Writing the ending of the story 4 5.3%

●

Discussion

It is striking that 39.5% of the students disliked writing the story map although

they considered the map helpful to them. The reason why they disliked the story maps

was that it was trivial, time-consuming and boring to finish the story map. The

following is the summary of why they considered the map difficult based on the

interview.

●

There are too many story grammar units.

S305: I think there are too many story grammar units. They are too trivial and it is hard to

memorize them all. Too me, it is a heavy load to keep those story grammar units in

mind and write them down in details.

S416: I think it will be better if there are only “setting”, “problem”, and “solution.” I always

spend a lot of time recalling what all the story grammar units are, which makes me

frustrated and a little bit angry.

●

The activity is time-consuming and boring.

S412: I don’t like the story mapping instruction because it involves too muck work. I find it

time-consuming to finish the story map and then write down my story according to the

map. It will be easier for me to write whatever I like.

S433: I agree. I don’t like to do so many things during a writing class. To write a story based

on a map is boring and takes too much time. I always feel nervous because I am

worried that I can’t finish my map and story on time.

Ellis (2003) got the similar result in her research. She indicated that some of her

students felt it impossible to finish the story map and the composition during the

writing class. Under the pressure of time constraint, the participants considered doing

the map time-consuming since they had to finish the story in a limited time. The

researcher found that the students still lacked the ability to manage time well when

they wrote. They spent too much time on the prewriting stage, which left not enough

time for them to write a well-organized story with a reasonable ending. In the

interview, 5 students pointed out that there was not enough time for them to finish the

story map and compose their stories, which would make them a little bit nervous. That

is one of the reasons why some students still felt writing anxiety when they wrote.

As to the writing process, 8 participants said that they liked analyzing the reading

passage more than writing their own stories. The reluctance to write reflected that

some students still regard the writing as a tiring and challenging task.

The participants also indicated that they disliked writing the ending of their story.

Based on the responses and interview, it is found that students had difficulty writing

the ending without the help of picture of “Ending.” This finding shows the importance

of pictures, which can turn visual image into words.

Question 5: What is your problem when you write?

The fifth item in the questionnaire is to explore the writing problems of the

participants.

●

Results

The wiring problems of the participants could be summarized into four

categories, which are shown in Table 18. They are poor English, writers’ block, time

management and creativity. A majority of the students had problem with vocabulary

and grammar (78.9%, N=60). Eight students had difficulty finishing writing in the due

time. Five students did not know what to write when they got the pictures. They had

the problem of the writer’s block. Two students said that they lacked creativity.

Table 18

The Number and Percentage of the Students’ Writing Problem (N=76)

5. What is your problem when you write?

N %

Limited vocabulary, poor grammar, Chinese English 60 78.9%

Time management 8 10.5%

Writer’s block 5 6.6%

Lacking creativity 2 2.6%

No 1 1.3%

●

Discussion

Based on the results, it is found that only five students had the problem of

writer’s block after the story-mapping instruction, which means that story mapping,

an organized and schematic strategy, helps students come up with ideas to write about.

After the instruction, most students would not feel shocked or go blank when they did

the picture writing. The majority of the students had the same problem of EFL

beginning writers. The students reported they felt frustrated when they could not

express themselves clearly in English. They tend to think in the Chinese style and

tried to translate what they wanted to say in English. However, they just could not

find appropriate vocabulary to express their ideas and thoughts. Besides, they were

worried about the grammar, which would block their thinking sometimes. Still, some

reported that they could not manage time well. S305 said, “I spent too much time on

planning, which led to loose actions and a poor ending of my story.” Furthermore, the

time constraint made them nervous, which blocked their thought. Last but not the

least, the students found it challenging and frustrating to come up with creative and

brilliant ideas to compose a good story. They worried that their stories were too

“ordinary” or not so “ attractive” and “imaginative.” These problems seem common

to EFL beginning writers. The researcher suggests that the EFL writing instructors ask

their students to read extensively and pay attention to the collocation, rhetorical

devices and writing convention of English writing to improve the students’ writing

performance.

Question 6: What are your suggestions on the story mapping instruction?

The sixth item in the questionnaire is to elicit the participants’ suggestions on the

story-mapping instruction.

●

Result

Table 19 shows the results of Question 6. The students’ suggestions are

summarized as follows.

First, 39.5% of the participants (N=30) thought that there was room for

improvement of pictures because they found some pictures were not interesting or

inspiring. Some of them also suggested that a single picture might be more flexible

and give them more opportunity to create their stories than fixed sequential pictures.

The researcher suggests that future research can investigate different effects of picture

writing with one single picture and that with multiple pictures.

Second, 30.3% of the students (N=23) suggested that the story map include

fewer story grammar units. They expressed that too many story grammar units made

them confused and took too much time to complete them all.

Third, 13.2% of the participants (N=10) suggested they be given more time to

finish their stories. They said that the story map provided them with inspiration and

that they had a lot to write about. Fourth, 6.6% of the students (N=5) thought it would

be better if the teacher could give more examples of well-organized stories because

they would like to know more about the structure of stories and other genres. They

thought the analysis of reading was beneficial to their reading comprehension and

composing.

One student offered an interesting suggestion. She suggested that the skill of

story telling based on the story mapping be taught. She said, “It would be cool and

challenging to tell a story based on a story map. I think the knowledge of story

grammar would surely help me with my story telling. I would love to participate in

the training program if there is one.”

Table 19

The Number and Percentage of the Students’ Suggestion toward the Instruction N=76

6. What are your suggestions toward the story mapping instruction?

N %

Providing more interesting pictures 30 39.5%

Simplifying the story grammar units 23 30.3%

Giving more time to complete the story 10 13.2%

No 7 9.2%

Giving more examples of story structure analysis 5 6.6%

Applying the instruction to storytelling 1 1.3%

●