DOI 10.1007/s00595-007-3619-0

Reprint requests to: W.-J. Lee (address 1)

Received: October 13, 2006 / Accepted: May 27, 2007

Laparoscopic Antirefl ux Surgery for the Elderly: A Surgical and Quality-of-Life Study

WEU WANG1, MING-TE HUANG1, PO-LI WEI1, and WEI-JEI LEE1,2

1 Department of Surgery and Minimal Invasive Center, Taipei Medical University Hospital, 252 Wu Hsing Street, Taipei, Taiwan

2 Department of Surgery, Min-Sheng Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Abstract

Purpose. Laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery (LARS) has long been introduced as an alternative method for the treatment of gastroesophageal refl ux disease (GERD) in young adults. However, the safety of this procedure and the associated improvement in the quality of life for the elderly are rarely discussed. This study compared the results between young and elderly patients who underwent laparoscopic fundoplication for the treat- ment of GERD.

Methods. From January 1999 to January 2006, there were 231 adult patients who underwent LARS for GERD at a single institute. Among all patients, 33 patients were older than 70 years old (14.3%, 73.0 ± 1.9, range 70–76), 198 patients were younger than 70 years old (85.7%, 46.6 ± 11.5, range 20–69). The clinical char- acteristics, operation time, postoperative hospital stay, surgical complications, and quality of life were retro- spectively analyzed.

Results. The mean operation time had no signifi cant difference between the younger group and the elderly group. The mean postoperative hospital stay in the elderly group was slightly longer than the younger group (4.1 ± 2.5 days vs 3.4 ± 1.3 days, P = 0.19). There were no mortalities and no major complications found in each group. No patients required conversion to an open procedure. Four patients had minor complications (three in the elderly group, rate: 9.0%; one in the younger group, rate: 0.5%, P < 0.05). There were two patients in the nonelderly group who had recurrence. A com- parison of the preoperative and postoperative Gastro- Intestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) scores showed signifi cant improvements (99.3 ± 19.2 points, and 110.2

± 20.6 points, respectively, P < 0.05) with no signifi cant difference between the two groups.

Conclusion. Laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery thus appears to provide an equivalent degree of safety and symptomatic relief for elderly patients with GERD as that observed in young patients.

Key words Refl ux esophagitis · Laparoscopy · Fundopli- cation · Old age

Introduction

Gastroesophageal refl ux disease (GERD) is a common clinical problem that results in high medical care expenses. The surveys indicate that almost 45% of American adults experience heartburn, the cardiac symptom of GERD, at least once a month and 7% are reported to have such symptoms on a daily basis. The incidence of GERD in Taiwan has grown steadily in the past years and it is therefore considered to be underes- timated clinically. According to endoscopic surveillance, the rate of erosive esophagitis in Taiwan increased from 2.4% in 1979 to 14.5% in 1997.1,2

Management for GERD includes lifestyle and diet modifi cation, drugs that inhibit gastric acid output, and surgery. The fi rst laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery was reported in 1991.3,4 Since then a laparoscopic approach has proven to be as effective as the open method, while also reducing the morbidity rate and hospital stay.5–12

As life expectancy increases, the number of elderly patients presenting with surgical correctable GERD has increased as well. However, with underlying chronic dis- eases more prevalent in the elderly, they could increase the operative risks for elderly patients. Old age had been regarded as a relative contraindication for laparo- scopic surgery. Several studies have reported that lapa- roscopic antirefl ux procedures can be safe and effective in the elderly,13–19 but no supporting data are currently available from oriental countries.

We started to perform laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery for the treatment of gastroesophageal refl ux disease in 1998.20 One of our previous studies reported that lapa- roscopic antirefl ux surgery is as safe and effective as open procedures in treating GERD in Taiwanese patients.21 Whether it can be as safe and effective in the elderly patients as in younger patients in Taiwan has still not yet been well studied. The objectives of this study are to retrospectively compare patients receiving lapa- roscopic antirefl ux surgery who are older than 70 years of age to those younger than 70 years of age, and to assess their surgical outcomes and improvements in the gastrointestinal quality of life index.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Between January 1999 to January 2006, 231 consecutive patients who received laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery in our hospital under the diagnosis of GERD were included in this study. Thirty-three patients were older than 70 years of age, with a mean age of 73.0 ± 1.9 years (range:

70–76 years), and 198 patients were younger than 70 years of age, with a mean age of 46.7 ± 11.5 years (range:

20–69 years). The pre-operative work-up included endoscopy, barium swallow, esophageal manometry, and 24-h pH studies. All patients received laparoscopic antirefl ux procedures (including Nissen and Toupet fundoplication) after demonstrating a failure of 2-year medication control.

Surgical Techniques

All operations were performed laparoscopically using the fi ve-trocar approach. The gastric fundus was widely mobilized by dividing the short gastric vessels using the harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH). The hiatal hernia was documented by preopera- tive esophagograms, and endoscopic and intraoperative fi ndings. Patients who had a hiatal hernia received a reduction of herniated stomach and the hernia sac was removed. The esophageal hiatus was reconstructed when necessary. The Nissen fundoplication was 2.5–

3.0 cm long, secured with three to four nonabsorbable stitches (according to the size of the hernia), and fl oppy.

An endoscope was placed in the esophagus for calibra- tion. In patients who received the Toupet technique, the posterior wrap was fi xed to the right crus and afterwards to the right side of esophagus. The corresponding part of the fundus was then fi xed to the left side of the esophagus. In the fi rst 33 patients, laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication was the choice of treatment. However, we changed our methodology to Nissen fundoplication

afterwards, and the Toupet procedure was applied only to patients with an impaired esophageal motility on a manometric study, and 10 patients received this proce- dure afterwards. The surgical outcome including the operation time, postoperative hospital stay, mortality, and complications were collected by retrospective chart reviews.

Quality of Life Assessment

The Gastro-Intestinal Quality-of-Life Index (GIQLI) was utilized to evaluate the improvement of symptoms for our patients in the study. GIQLI is a 36-item- questionnaire divided into fi ve domains: core symptoms (10 items), physical status (7 items), psychological emo- tions (6 items), social functioning (3 items), and disease- specifi c symptoms (10 items). Each item is evaluated from 0 to 4 (0 being the worst and 4 being the best). The maximum score is 144. The patients were asked to fi ll out a life quality questionnaire evaluation before surgery and 3 months after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

The results were reported as the mean ± standard devia- tion. Values of P < 0.05 were regarded as statistically signifi cant. All data were recorded on standardized data collection forms, which were then transferred into a commercially-available electronic database system for personal computers and analyzed by the SPSS statistical software program 10.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

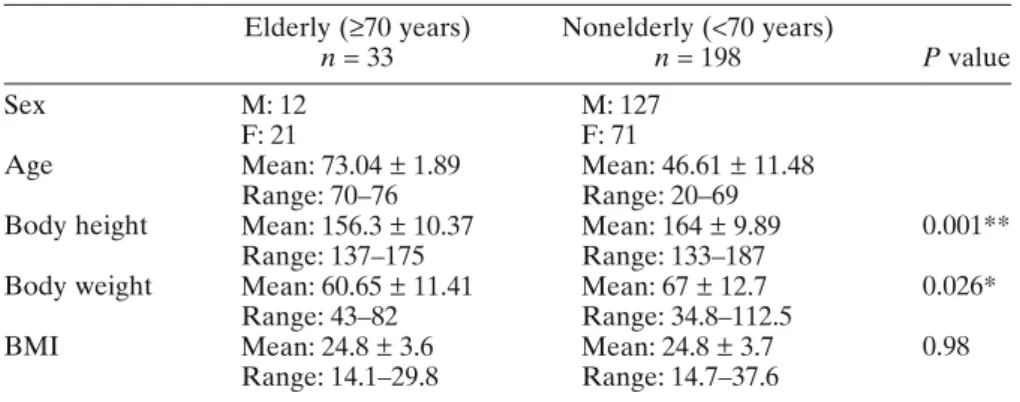

The demographic and preoperative features of the two groups of patients are shown in Table 1. Differences between the two groups were seen in their averaged height and body weight (P = 0.001 and 0.026, respec- tively), but the mean BMI had no signifi cant difference (P = 0.98). Forty-three patients received laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication with 9 patients in elderly and 34 patients in the nonelderly group, and the other 188 patients had Nissen fundoplication with 24 in the elderly and 164 patients in the nonelderly group. The mean follow-up was 30.01 months. The operative and preop- erative results for the two groups are given in Table 2.

There was no signifi cant difference in the operative time (P = 0.79) with the elderly group averaging 130.4 ± 37.4 min (range: 75–265 min), whereas the mean opera- tive time in the younger group was 132.7 ± 38.5 min (range: 65–295 min). Regarding hospital stay, the length of postoperative hospital stay in the elderly was 4.1 ± 2.5 days (range: 2–13 days) in comparison to the 3.4 ±

1.3 days (range: 1–9 days) surveyed in the younger group. Hence, the two groups demonstrated no signifi - cant difference in postoperative hospital stay (P = 0.19) either.

There was no mortality in our series and no patients required conversion to open procedures. There were no severe complications such as splenic injury, postopera- tive bleeding, and perforation of alimentary tract. Only four patients had minor complications (three in the elderly group, rate: 9.0%; one in the younger group, rate:

0.5%). Two of these four patients experienced pneumo- nia postoperatively but they were successfully controlled by antibiotics. Another complication occurred in a 76- year-old woman, who experienced prolonged dysphagia and vomiting after the surgery. Her condition improved by diet modifi cation. The only complication found in the younger group was subcutaneous emphysema which required no further treatment. Out of all the patients studied, only two were found to have recurrence. Both of them were in the younger group. One patient received the Toupet procedure, and revision surgery showed a disruption of the previous suture. Another patient had slippage of stomach through fundoplication.

Quality of Life

There were 82 (35.5%) patients who fi lled out the preoperative GIQLI questionnaire (71 in the younger group, rate: 35.9%; 11 in the elderly group, rate: 33.3%).

In addition, 89 patients completed the GIQLI question- naire 3 months after the laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery (LARS) (74 in the younger group, rate: 37.4%; 15 in the elderly group, rate: 45.5%). The comparison of preop- erative and postoperative GIQLI score of all patients is shown in Table 3. Preoperatively, the mean general score of GIQLI for all patients was 99.3 ± 19.2 points. The mean scores for the fi ve domains were: core symptoms, 22.9 ± 5.9 points; emotional status, 12.1 ± 5.0 points;

physical functions, 18.4 ± 5.7 points; social functions, 14.8

± 4.0 points; and disease-special items, 31.1 ± 5.5 points.

Three months after LARS, the mean general score improved signifi cantly to 110.2 ± 20.6 points (P < 0.05).

The mean scores for the fi ve domains were: 24.8 ± 6.0 points in core symptoms, 15.1 ± 4.3 points in emotional status, 20.9 ± 5.4 points in physical functions, 16.3 ± 3.9 points in social functions, and 33.0 ± 4.7 points in disease- special items.

Table 1. Demographics of the patients Elderly (≥70 years)

n = 33 Nonelderly (<70 years)

n = 198 P value

Sex M: 12 M: 127

F: 21 F: 71

Age Mean: 73.04 ± 1.89 Mean: 46.61 ± 11.48

Range: 70–76 Range: 20–69

Body height Mean: 156.3 ± 10.37 Mean: 164 ± 9.89 0.001**

Range: 137–175 Range: 133–187

Body weight Mean: 60.65 ± 11.41 Mean: 67 ± 12.7 0.026*

Range: 43–82 Range: 34.8–112.5

BMI Mean: 24.8 ± 3.6 Mean: 24.8 ± 3.7 0.98

Range: 14.1–29.8 Range: 14.7–37.6 BMI, body mass index

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

Table 2. Surgical outcomes and complications Elderly (≥70 years)

n = 33 Nonelderly (<70 years)

n = 198 P value

Hospital stay (days) Mean: 4.1 ± 2.5 Mean: 3.4 ± 1.3 0.19

Range: 2–13 Range: 1–9

Operation time (min) Mean: 130.4 ± 37.4 Mean: 132.7 ± 38.5 0.79 Range: 75–265 Range: 65–295

Complication <0.01

Minor 9.0% (3) 0.5% (1)

Major 0 0

Mortality 0 0

Comparisons of the preoperative and postoperative GIQLI scores in the two age groups were made. The preoperative general score was 98.8 ± 18.6 points in the younger group and 102.4 ± 25.0 points in the elderly group. There was no signifi cant difference between the two age groups regarding the preoperative GIQLI scores. Similar results were also revealed in a compari- son of the postoperative GIQLI scores. The postopera- tive general score was 109.1 ± 20.5 points in the younger group and 115.4 ± 20.9 points in the elderly group.

Discussion

Gastroesophageal refl ux disease is commonly found among adults, with 10%–20% of the Western popula- tion having daily symptoms. Although GERD affects all age groups including the elderly, it has not been studied extensively in older individuals. However, as life expec- tancy increases, the prevalence of elderly patients with GERD will rise as well. Several studies have suggested that elderly patients with GERD are likely to have Table 3. Comparison of the preoperative and postoperative Gastro-Intestinal Quality of Life Index scores

Item

Preoperative

<70 years old Preoperative

>70 years old Postoperative

<70 years old Postoperative

>70 years old Symptoms

Abdominal pain 2.8 3.2 3.2 3.5

Abdominal fullness 2.2 2.2 2.8 2.9

Abdominal bloating 2.1 2.5 2.4 3.0

Flatulence 2.6 2.4 1.8 2.4

Belching 2.7 3.0 3.0 3.3

Abdominal noises 3.0 3.4 3.0 3.7**

Bowel frequency 3.1 3.6 3.4** 3.9*

Enjoyed eating 1.8 1.8 1.9 2.0

Restricted eating 2.0 2.1 2.7 2.7

Regurgitation 2.9 2.4 3.5* 3.0*

Dysphagia 3.2 3.3 2.7* 2.9

Eating speed 3.0 2.9 2.6 2.5*

Nausea 2.9 2.8 3.5 3.5

Diarrhea 3.0 3.3 3.2 3.6

Bowel urgency 3.3 3.4 3.4 3.7

Constipation 3.3 3.0 3.2 2.6

Blood in stool 3.8 3.7 3.8 4.0

Heartburn 2.3 2.6 3.3** 3.5*

Incontinence 3.8 3.6 3.9 3.5

Emotional status

Coping with stress 2.1 2.2 2.5 2.8

Sadness 2.1 2.7 2.9 3.4

Nervousness 2.4 2.8 3.1 3.6

Frustration 2.6 2.8 3.2 3.5

Happiness 2.4 3.0 3.0** 3.7*

Physical functions

Fatigue 2.7 2.8 2.8 3.1

Feeling unwell 2.0 2.2 2.8 2.9

Wake-up at night 2.5 2.6 2.9 3.2

Appearance 3.3 3.7 3.5 3.9

Physical strength 2.7 2.9 2.8 3.0

Endurance 2.4 2.5 2.9 2.9

Feeling unfi t 2.6 2.6 3.0 2.9

Social functions

Daily activities 3.0 3.0 3.2 3.4

Leisure activities 2.9 3.0 3.2 3.1

Bothered by treatment 2.4 2.6 3.0 3.3

Personal relationship 3.3 3.6 3.5 3.7

Sexual life 3.2 2.7 3.4 3.1

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01; signifi cant in comparison to the preoperative data

more severe esophageal mucosal disease than younger group does,22,23 thus it is of relevant importance to evalu- ate the treatment of GERD in elderly patients.

Despite the good response rate of modern antisecre- tory therapy, GERD can only be cured by surgery. Since the 1990s, LARS has become an effective and safe option for the treatment of patients with severe or com- plicated GERD. Several studies have shown excellent surgical outcomes with a healing rate of 85%–100%, and a low percentage of morbidity and mortality.5–8,24,25 However, few such studies have discussed their experi- ences with elderly patients. Do the underlying chronic diseases, which are more prevalent in the elderly, pose an increase in the elderly patients’ operative risk?

Whether LARS can be performed safely and effectively in elderly patients as in younger patients has not yet been well discussed in existing studies.

With the few studies that brought up the discussion on the effect and safety of LARS in the elderly patients with GERD, all of them reported similar surgical results between the elderly group and nonelderly group includ- ing similar operation time, postoperative hospital stay, and low morbidity and mortality.13,14,19,26

Our study also demonstrated similar results with a mean operation time and postoperative hospital stay showing no signifi - cant difference between the two groups. There was no mortality or major operative complications in our study either. The results in our studies are similar to those of reports form Western countries.24,25 Although in our study the minor complication rate was signifi cantly higher in the elderly group than in the nonelderly group (8.7% vs 0.7%), it was because the complication rate in the nonelderly group was low in our study. The compli- cation rate in the elderly group of our study was com- parable to other series (5.6%–16.7%).19,26 There are two procedures performed in our study. In the beginning of our practice, we chose Toupet fundoplication as choice of treatment.28 However, we changed to Nissen fundo- plication as fi rst choice of treatment, unless an impair- ment of esophageal motility was seen in the patients, after the fi rst 33 cases. Comparisons between two pro- cedures are therefore not made because the indications for the choice of operation differ depending on the time when the fi rst choice of surgical procedure is changed to Nissen fundoplication.

In evaluating the quality of life of the GERD patients, scales such as SF36, well-being score, and GIQLI are amongst the common tools used. The GIQLI, fi rst pub- lished in the German version in 1993 and English version in 1995,29 is the only validated tool to assess specifi c quality of life in patients with various gastrointestinal diseases.30,31 For our study, we used GIQLI to evaluate the life quality improvement of the patients. It is well established, validated, and has been recommended by the European Study Group for Antirefl ux Surgery. In

our study, both groups demonstrated signifi cant improve- ments after LARS. In addition, there were no statistical differences between the elderly and the nonelderly postoperatively regarding the GIQLI score. The elderly patients even presented greater improvements in the aspects of abdominal noises (3.7 vs 3.0; P < 0.01), bowel frequency (3.9 vs 3.4; P < 0.01), blood in stool (4.0 vs 3.8;

P < 0.001), and happiness (3.7 vs 3.0; P < 0.05).

Our study demonstrates that good functional results also can be obtained in elderly patients undergo- ing antirefl ux surgery using a laparoscopic approach.

Therefore, patients older than 70 years old should not be a contraindication to laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery in properly selected patients. It should thus be widely adopted if the expertise in the area of laparoscopic surgery is available for this group of patients. Further studies should be carried out to evaluate the long-term outcome, cost-effectiveness and quality of life in these patients.

References

1. Chen PC, Wu CS, Chang-Chien SC, Liaw YF. Comparison of Olympus GIF-P2 and GIF-K panendoscopy J. Formos Med Assoc 1979;78:136–40.

2. Yeh C, Hsu CT, Ho AS, Sampliner RE, Fass R. Erosive esopha- gitis and Barrett’s esophagus in Taiwan: a higher frequency than expected. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:702–6.

3. Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, Markiewicz S, Lombard R.

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1991;1:138–43.

4. Geagea T. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report on ten cases. Surg Endosc 1991;5:170–173.

5. Arnavd JP, Pessaux P, Ghavami B, Flamont JB, Trebuchet G, Meyer C, et al. Laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal refl ux: multicenter study of 1 470 cases. Chirurgie 1999;124:

516–22.

6. Terry M, Smith CD, Branum GD, Galloway K, Waring JP, Hunter JG. Outcomes of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastro- esophageal refl ux disease and paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc 2001;15:691–9.

7. Hinder RA, Filipi CJ, Wetscher G, Neary P, DeMeester TR. Lapa- roscopic Nissen fundoplication is an effective treatment for gas- troesophageal refl ux disease. Ann Surg 1994;220:472–83.

8. Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, Waring JP, Wood WL. A physi- ologic approach to laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesopha- geal refl ux disease. Ann Surg 1996;223:673–87.

9. Swanstrom L, Wayne R. Spectrum of gastrointestinal symptoms after laparoscopic fundoplication. Am J Surg 1994;167:538–41.

10. Eshraghi N, Farahmand M, Soot SJ, Rand-Luby L, Deveney DW, Sheppard BC. Comparison of outcomes of open versus laparo- scopic Nissen fundoplication performed in a single practice. Am J Surg 1998;175:371–4.

11. European Association for Endoscopic Surgery Consensus Devel- poment Conference. Laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery for gastro- esophagealrefl ux disease (GERD). Surg Endosc 1997;11:413–26.

12. Laine S, Rantala A, Gullichsen R, Ovaska J. Laparoscopic vs con- ventional Nissen fundoplication: a prospective randomized study.

Surg Endosc 1997;11:441–4.

13. Trus TL, Laycock WS, Wo JM, Waring JP, Branum GD. Laparo- scopic antirefl ux surgery in the elderly. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:351–3.

14. Kamolz T, Granderath FA, Bammer T, Pasiut M, Pointner P. Failed antirefl ux surgery: surgical outcome of laparoscopic refundoplica- tion in the elderly. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2002;49:865–8.

15. Weber DM. Laparoscopic Surgery: an excellent approach in the elderly. Arch Surg 2003;138:1083–8.

16. Lopez CB, Cid JA, Poves I, Bottonica C, Villegas L, Memon MA.

Laparoscopic surgery in the elderly patient. Surg Endosc 2003;

17:333–7.

17. Bammers T, Hinder RA, Klaus A, Libbey JS, Napoliello DA, Rodriquez JA. Safety and long-term outcome of laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery in patients in their eighties and older. Surg Endosc 2002;16:40–2.

18. Khajanchee YS, Urbach DR, Butler N, Hansen PD, Swanstrom LL. Laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery in the elderly: surgical outcome and effect on quality of life. Surg Endosc 2002;16:

25–30.

19. Brunt LM, Quasebarth MA, Dunnegan DL, Soper NJ. Is laparo- scopic antirefl ux surgery for gastroesophageal refl ux disease in the elderly safe and effective. Surg Endosc 1999;13:838–42.

20. Huang MT, Lai IR, Wei PL, Wu CC, Lee WJ. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for refl ux esophagitis: the initial experience.

Formos J Surg 2000;33:66–71.

21. Lai IR, Lee YC, Lee WJ, Yuan RH. Comparison of open and laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery for the treatment of gastroesopha- geal refl ux disease in Taiwanese. J Formos Med Assoc 2002;101:

547–51.

22. Collen MJ, Abdulian JD, Chen YK. Gastroesophageal refl ux disease in the elderly: more severe disease that requires aggressive therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:1053–7.

23. Mold JW, Reed LE, Davis AB, Allen ML, Decktor DL, Robinson M. Prevalence of gastroesophageal refl ux disease in elderly

patients in a primary care setting. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:

965–70.

24. Zhu H, Pace F, Sangaletti O, Porro BG. Features of symptomatic gastroesophageal refl ux in elderly patients. Scan J Gastroenterol 1993;28:235–8.

25. Fuchs KH, Feussener H, Bonavina L, Collard JM, Coosemans W.

Current status and trends in laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery:

results of a consensus meeting. Endoscopy 1997;29:298–

308.

26. Kamolz T, Bammer T, Granderath FA, Pasiut M, Pointner R.

Quality of life and surgical outcome after laparoscopic antirefl ux surgery in the elderly gastroesophageal refl ux disease patient.

Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;2:116–20.

27. Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jeahes C, Markiewicz S. Results of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Hepatogastroenterol 1998;45:

1338–43.

28. Gadenstatter M, Klingler A, Prommegger R, Hinder RA, Wetscher GJ. Laparoscopic partial posterior fundoplication provides excel- lent intermediate results in GERD patients with impaired esoph- ageal peristalsis. Surgery 1999;126:548–52.

29. Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM. Schmulling C. Neugebauer E, et al. Gastrointestinal quality of life index:

development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 1995;82:216–22.

30. Jentschura D,Winkler M, Strohmeier N, Rumstadt B. Hagmuller E. Quality of life after curative surgery for gastric cancer: A com- parison between total gastrectomy and subtotal gastric resection.

Hepatogastroenterology 1997;44:1137–42.

31. Slim K, Bousquet J, Kwiatkowski F, Lescure G. Pezet D. Chipponi J. Quality of life before and after laparoscopic fundoplication. Am J Surg 2001;180:41–5.