CHAPTER 6 DISCUSSION

6.1 The Leveling of Taiwan Mandarin

The results reported in Chapter 5 indicated that an ethnic gap of tonal range between Waishengren and Benshengren remained in the 1951-1960 group, while this gap had been leveled in the following generation, i.e., the 1981-1990 group. Except the Ethnicity x Gender interaction effect on vowel, the ethnicity factor did not perform significant effects on the linguistic performances in other examined variables, including neutral tone, vowel, and nasal ending. In other words, the mechanism of phonological leveling between the Mandarin of Waishengren and Benshengren has started as early as in the generation of 1951-1960; tonal range, among all examined variables, is the last phonological variable to be leveled in Taiwan Mandarin.

Trudgill (2004) referred to the situation where “there is no prior existing

population speaking the language in question” as “tabula rasa” situation (p.26). In the

exploration of dialect contact, tabula rasa situations should be distinguished from

areas where there have already been speakers of some forms of the language in situ or

in neighboring areas, such as new town. This is because the mechanism of geographical diffusion of linguistic forms can involve in the formation of a new dialect. Southern Hemisphere Englishes, including Australian English, New Zealand English, and South African English, can be considered the results of tabula rasa type of dialect contacts – the contacts of various varieties of English brought into these new settlements by the immigrants from Britain.

The formation of Taiwan Mandarin is to certain degrees comparable to those of Southern Hemisphere Englishes. Taiwan can be considered a tabula rasa area in terms of Mandarin, as there had been nearly no Mandarin domains in Taiwan at the time when the large-scaled immigration from China occurred in the period between 1945 and 1949, peaking in 1949.

Trudgill (1986, Ch.3) suggested that the formation of a new dialect in H Oyanger,

a Norwegian new town, entailed three stages, roughly corresponding to three

successive generations of speakers. The three-generation/ three-stage notion was also

adopted in Trudgill et al. (2000) in the formation of New Zealand English. It is

noteworthy that, in spite of the fact that both took three generations to form,

H Oyanger dialect is a new town dialect while New Zealand English is a tabula rasa

type of dialect. The generation lines may be ambiguous in determining the formation

of a new dialect. Based on the findings in ONZE (Origins of New Zealand English)

project and a study by Bauer (1997) which suggested that by 1890 New-Zealand born Europeans in the country had outnumbered the immigrants (p.386), Trudgill (2004) further specifically proposed that the formation of a new dialect out of a dialect mixture situation took fifty years (p.23).

It was not until 1840 did English language arrive as a significant force in New Zealand with large groups of immigrants. Trudgill (2004) thus adopted 1840 as the first year of the crucial period of the formation of New Zealand English and inferred that New Zealand English was formed between 1840 and 1890; the first adolescent speakers of New Zealand English were expected in about 1905. Trudgill (2004), supported by various investigation results of previous studies, also applied parallel assumptions of the formation periods and the expected years of the appearances of the first adolescent speakers to other Southern Hemisphere Englishes, including Australian English and South African English.

If we follow the pattern of these Southern Hemisphere Englishes and adopt 1949,

the peak year of the large-scaled migration from China to Taiwan, as the onset year of

the crucial period of the formation of Taiwan Mandarin, Taiwan Mandarin should

have been formed between 1949 and 1999; the first adolescent speakers of Taiwan

Mandarin were expected to appear in the year 2014. However, apparently, the

formation of Taiwan Mandarin was faster than Southern Hemisphere Englishes.

According to Trudgill (2004), stable New Zealand English features were not observed in the first generation of New Zealand-born Anglophones. Unlike New Zealand English, the results of the current study indicated that many features of Taiwan Mandarin, such as diphthong weakening and syllable-final nasal convergence s, have already rather stably existed in the Mandarin of the first Taiwan-born Waishengren generation. Instead of fifty years as Trudgill (2004) suggested for New Zealand English, the formation of Taiwan Mandarin took only approximately thirty years; a rather complete phonological leveling was observed in the 1981-1990 generation.

6.1.1 Possible factors of the rapid leveling

As New Zealand English, Taiwan Mandarin is also a language formed in tabula rasa settlement. The question now is “why could Taiwan Mandarin be formed in a rather brief period?”. Possible factors may be numerous and various; the current study suggests three. The first is the intensiveness of Waishengren migration to Taiwan. The second is the exclusive Mandarin-only language policy. The third is the already-established social order in Taiwan when the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist, hereafter KMT) government started its rule in Taiwan in 1945.

6.1.1.1 Waishengren migration to Taiwan- an event; British migration to New Zealand- a tendency

The migration from Britain to these Southern Hemisphere new settlements

appeared as a “trend”, while the migration from China to Taiwan could be considered as an “event”. If we compare the course of history to a line, a trend occupies a portion of the line, while an event merely occupies a point. The linguistic impact of English to New Zealand carried by the migration was thus moderate and chronic while its Mandarin counterpart to Taiwan was intensive.

In 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed and New Zealand became a British colony, thus commenced immigration waves. In the early years of the colonization, there were three main flows of migration from Britain and Ireland. The first was the gold boom in 1860s; the government-assisted migration from 1871 further hit two peaks of inflow of British people (source: www.nzhistory.net.nz). Migration history is, of course, not the main interest of this study. This brief description of migration history is to highlight the slow flow of British migration to New Zealand.

Waishengren migration to Taiwan, on the other hand, took place as a boom. Simply speaking, this forced mass migration was an intensive and brief event; the process of its beginning, peak, and end was completed in less than five years.

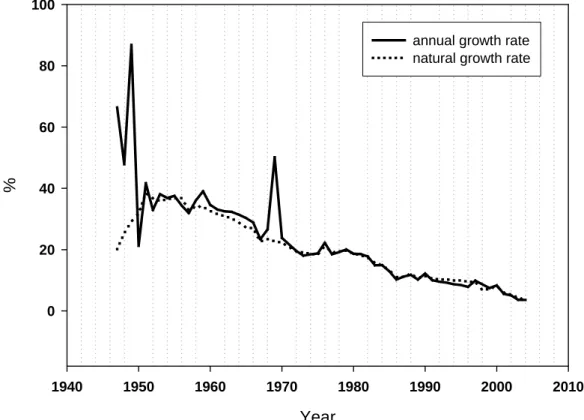

The government of Taiwan started official demographic statistics in 1947; the

annual growth rates and the natural growth rates of each year since 1947 are

illustrated in Figure 6-1. In this figure, salient gaps between annual growth rates and

natural growth rates in the years 1947, 1948, and 1949 are observed, indicating the

existence of a large-scaled migration in these three years. Lin (2004) also suggested that among the 640 thousands Waishengren population indicated in the first official

Year

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

%

0 20 40 60 80 100

annual growth rate natural growth rate

Figure 6-1 The annual growth rate and natural growth rate of the population of Taiwan

16 (Source: Department of Population, Ministry of Interior, Republic of China (Taiwan), www.ris.gov.tw/ch4/static/st20-1)census of Taiwan held in 1956, 550 thousands migrated to Taiwan before the year 1950. Lin (2004) also mentioned that Waishengren accounted for less than 1% of the Taiwan population before 1945. In fact, the gaps of annual growth rates in the years

from 1947 to 1949 should have been wider because a large number of soldiers

16 The figure was created by the author according to the official statistical data.

migrated with the government were registered in the military system and thus were not included in any official demographic surveys until 1969 when a household registration reformation was administered to de-militarize the household system.

6.1.1.2 the exclusive Mandarin-only language policy

In addition to the different migration patterns between Southern Hemisphere settlements and Taiwan, it is likely that the long-term exclusive Mandarin only policy in Taiwan has accelerated the diffusion and leveling of Mandarin in Taiwan. On the one hand, this language policy actively pushed the children to learn and speak Mandarin only. On the other hand, this language policy created a rather simple linguistic environment for children , i.e., Standard Mandarin as the only model to follow and pursue. Children might thus be able to avoid the confusion caused by the high degrees of linguistic heterogeneity in an immigrant society.

Soon after KMT government started its rule in Taiwan, the Mandarin movement

began to be promoted as the only official language. Mandarin had been the only

language allowed in the education system and official occasions, including the

majority of the media. As a result, Mandarin has penetrated into nearly all domains of

Taiwan (for details, see Huang 1993 and Tsao 2000). Even Benshengren adults who

originally had no Mandarin capabilities or experiences must acquire this language for

their careers or just for daily life. The entire community in Taiwan thus has undergone

a “group second language acquisition” (Winford 2003, p.231) of Taiwan Mandarin.

As described in subsection 4.2.2, the current study does not investigate the phonological features of Taiwanese Mandarin. This is not only because such stigmatized features mainly remain in the speeches of old Benshengren and are rapidly disappearing, but also due to the insights suggested by previous studies that young children played a pivotal role in the new-dialect formation process (e.g.

Trudgill 2004, p.27; Bernard 1981, p.19), particularly in tabula rasa dialect contact situations.

Some previous sociolinguistic studies suggested that eight or younger was the age at which children could acquire new languages or dialects to a rather perfect degree (e.g. Labov 1972, Payne 1980, Trudgill, 1986). Trudgill (2004) believed that unless salient social factors, such as prestige, were involved, linguistic changes could be explained simply in terms of patterns of interactions. He thus asserted that colonial dialect mixture situations “will eventually and inevitably lead to the production of a new, unitary dialect.” (p.27) because people, as Keller (1994) suggested, “talk like the others talk” (p.100) .

In the formation of New Zealand English, children’s pivotal role was indeed observed in the process of linguistic homogenization from highly heterogeneity.

However, this process took two generations— stable New Zealand English was not

observed among the first generation of New Zealand born English speakers (Trudgill 2004, p.23). While in Taiwan, as discussed previously, phonological leveling began in as early as the first generation Taiwan born Waishengren and their Benshengren peers.

Trudgill (2004) attributed the rather long process of New Zealand English to the highly heterogeneous linguistic environment that the first generation New Zealand born Anglophones faced. In this situation, there were “very many of the ‘others’ speak differently from one another” (p.28) It thus took longer for the speakers in New Zealand to speak like others. Comparing to the heterogeneous linguistic environment to New Zealand children in early days, the long-term Mandarin-only movement in Taiwan, though controversial, provided a simple, and more salient target for children to model after. In addition to the presentation of the target Standard Mandarin, this Mandarin movement has further actively, through assorted methods, pushed children to speak Standard Mandarin.

6.1.1.3 the established social order

The established social order may as well has participated in the rapid diffusion of

Mandarin. At the time when the KMT government started its rule in Taiwan, Taiwan

had already been colonized by Japan for five decades; fundamental social order and

infrastructures had been established. In other words, physically, Taiwan was by no

means a new settlement as New Zealand was. Via the established and even mature

social order and governmental system, including education system, Mandarin could be more efficiently promoted.

6.2 Taiwan Mandarin Neutral Tone as The Fifth Tone

As reported in previous studies and easily observed in this study, the number of neutral tone is largely reduced in Taiwan Mandarin. In addition, the acoustic analyses of the current study further observed that the “neutral tone” in Taiwan Mandarin is, strictly speaking, not neutral.

Conventionally, neutral tone syllables in Mandarin are considered weakly stressed syllables, the tones of which depend on the tones of the preceding syllables-- half-low after T1, mid pith after T2, half-high after T3, and low after T4 (Chao 1968, p.36). In addition, weak syllables are short in duration and have a reduced tonal range.

Some studies even pointed out that using the term “neutral tone” to refer to the tone of weakly stressed syllables was misleading because weakly stressed syllable could not be pronounced in isolation; while the term “neutral tone” might imply that such syllables were realized in a kind of “fifth tone” (Norman 1988, p.148).

However, none of the “typical” features of neutral tone, or the tone of weakly stressed syllables –short duration, reduced tonal range, and the dependence on the tone of the preceding syllable – was observed in the current study.

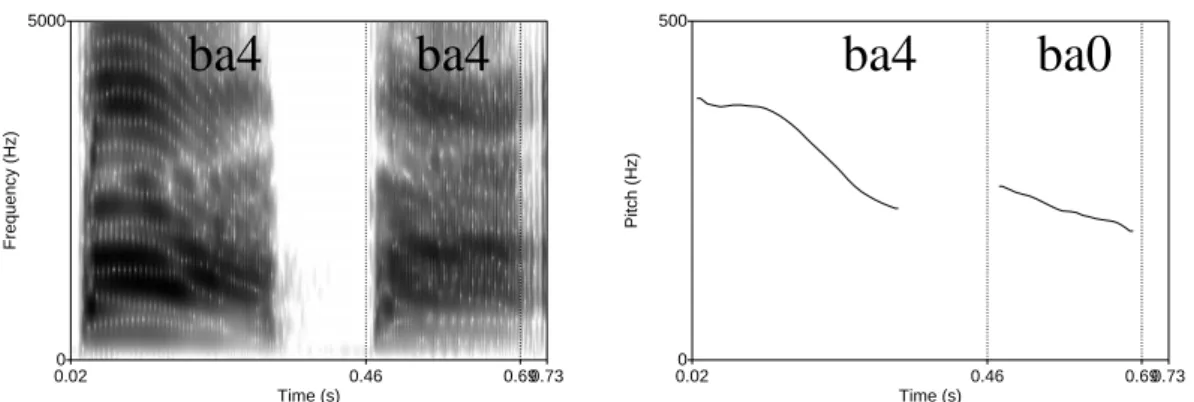

The durations of the neutralized syllables in the current study were not largely

shortened as in conventional neutralized tones. Figure 6-2 and Figure 6-3 present a contrast of the spectrograms and tonal contours of the term ba4ba0 (“father”) in Putonghua and Taiwan Mandarin respectively; both of the second syllables are neutralized. In Figure 6-2, the duration of the neutralized second syllable is 40% of its segmentally identical preceding syllable, while its counterpart in Figure 6-3, i.e.

Taiwan Mandarin, is 88%.

Time (s)

0.020 0.6

5000

Frequency (Hz)

Time (s)

0.03 0.6

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

0.43 0.55

ba0 ba4

0.55 0.43

ba4 ba0

Figure 6-2 An example of the spectrogram and the tonal contour of the term ba4ba0 (“father”) in Putonghua

Time (s)

0.020 0.73

5000

Frequency (Hz)

Time (s)

0.02 0.73

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

0.46 0.69

ba0 ba4

ba4 ba4

0.69 0.46

Figure 6-3 An example of the spectrogram and the tonal contour of the term ba4ba0

(“father”) in Taiwan Mandarin

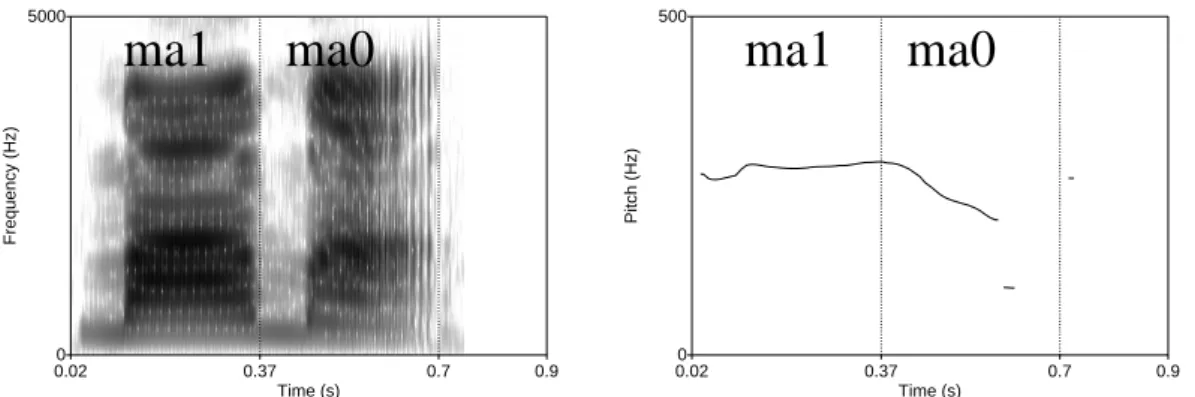

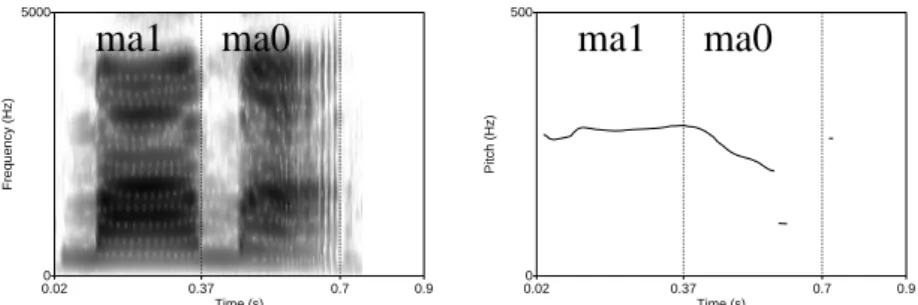

Another contrast can be observed in Figure 6-4 and Figure 6-5. In Figure 6-4, the duration of the neutralized second syllable is 60% of its segmentally identical preceding syllable, while its Taiwan Mandarin counterpart is 98%.

Time (s)

0 0.81

0 5000

Frequency (Hz)

Time (s)

0 0.81

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

0.71 0.46

ma0 ma1

0.46 0.71

ma1 ma0

Figure 6-4 An example of the spectrogram and the tonal contour of the term ma1ma0 (“mother”) in Putonghua

Time (s)

0.020 0.9

5000

Frequency (Hz)

Time (s)

0.02 0.9

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

0.7 0.37

ma0 ma1

ma1 ma0

0.37 0.7

Figure 6-5 An example of the spectrogram and the tonal contour of the term

ma1ma0 (“mother”) in Taiwan Mandarin

Furthermore, as described above, previous studies, such as Chao (1968), suggested that the tone of a neutralized Mandarin syllable depended on its preceding syllable. However, such dependence of tone was not observed in the current study of Taiwan Mandarin.

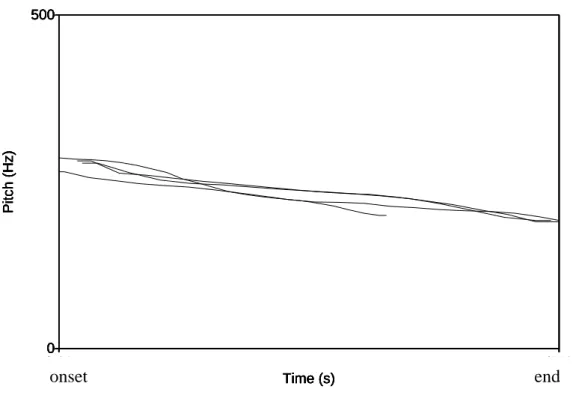

Figure 6-6 to Figure 6-9

17demonstrate the spectrograms and the tonal contours of four examples of Taiwan Mandarin reduplicated kinship terms. The second syllables of these terms were all “neutralized”, and the first syllables were realized in four different tones respectively, from tone1 to tone4. It appears that these first syllables do not perform salient effects on the tones of their syllables. In other words, these “neutralized” second syllables were in general opaque to their preceding syllables. All these “neutral tones” were realized as a kind of falling tone.

Figure 6-10 overlaps the contours of the four “neutral tones” in Figure 6-6 to

Figure 6-9. It is shown that these four neutral tones were all performed similarly in

terms of its contour, and tonal range; the different preceding tones did not carry over

salient tonal effects either. Simply speaking, “neutral tone” in Taiwan Mandarin,

though appearing infrequently, displays certain stable features that could “rectify” its

status as a “genuine” tone.

Time (s)

0.02 0.9

0 5000

Frequency (Hz)

Time (s)

0.02 0.9

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

0.7 0.37

ma0 ma1

ma1 ma0

0.37 0.7

Figure 6-6 An example of the spectrogram and the tonal contour of the term ma1ma0 (“mother”) in Taiwan Mandarin

Time (s)

0.54 1.48

0 5000

Frequency (Hz)

Time (s)

0.54 1.48

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

1.04 1.4

po0

po2 po2 po0

1.4 1.04

Figure 6-7 An example of the spectrogram and the tonal contour of the term po2po0 (“mother-in-law”) in Taiwan Mandarin

Time (s)

0.02 0.9

0 5000

Frequency (Hz)

Time (s)

0.02 0.9

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

0.76 0.48

jie0

jie3 jie3 jie0

0.48 0.76

Figure 6-8 An example of the spectrogram and the tonal contour of the term jie3jie0 (“older sister”) in Taiwan Mandarin

Time (s)

0.02 0.73

0 5000

Frequency (Hz)

Time (s)

0.02 0.73

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

0.46 0.69

ba0 ba4

ba4 ba4

0.69 0.46

Figure 6-9 An example of the spectrogram and the tonal contour of the term ba4ba0

(“father”) in Taiwan Mandarin

This finding of neutral tone of Taiwan Mandarin as a genuine tone mostly agrees with one result of Tseng (1999) in that neutral tone in Taiwan Mandarin behaves more like the fifth tone with the prosodic property of low pitch. In addition, Tseng(1999) further claimed that Taiwan Mandarin neutral tone was similar to an entering tone of Southern Min, implying the effects of language contact on the unique prosodic properties of Taiwan Mandarin neutral tone.

Time (s)

0.37 0.7

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

Time (s)

1.04 1.4

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

Time (s)

0.56 0.72

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

Time (s)

0.54 0.72

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

Time (s)

0.47 0.67

Pitch (Hz)

0 500

Figure 6-10 The tonal contours of the four neutral tones in Figure 6-6 to Figure 6-9

6.3 A Longtime Confusion – Syllable-final Nasals

The convergence or variation of syllable-final nasals has attracted Mandarin end

onset

researchers’ attentions. Kubler (1985) reported that Mandarin [- iN] and [-´N] were often replaced in Taiwan Mandarin by [- in] and [-´n]. In other words, the distinctions between the [- in] and [-iN] as well as between [´n] and [´N] being

neutralized. (p.94) Tse (1992), as described in subsection 4.2.2.2, also reported a tendency of the convergence of [ N] to [n] at syllable-final positions.

The issue of syllable-final nasal convergence continued to play a role in the current study. However, the current study showed a different result on the convergence of [- in] and [-iN]. It was observed in the current study that the variables [iN] and [ ´N] performed in different manners in terms of their merging directions. In the [iN] variable, [ N] outnumbered [n]. In other words, the convergence of [in] to [ iN] occurred more frequently than the other way around. On the other hand, in [´N]

variable, [ n] outnumbered [N], i.e., [´N] to [´n] occurred more frequently. Chen

(1991a) analyzed the speech data of 60 Taiwan Mandarin speakers with nearly equal

number of Waishengren and Benshengren, aging from 19 to 49. The results of

syllable-final nasal convergence s agreed with the current study that [ ´N] to [´n] and

[ in] to [iN] were the two predominant syllable-final nasal convergence s in Taiwan

Mandarin. However, in Chen’s study, the latter occurred more frequently than the

former in all age groups (Figure 6-11), while the data of the current study indicated an

opposite result. (Figure 6-12).

To summarize the results of syllable-final nasal convergence s in previous studies and the current study, it is observed that syllable-final nasal convergence in Taiwan Mandarin is not only a longtime confusion but also a volatile convergence . As mentioned previously, linguists have studied the issue of syllable-final convergence s in Taiwan Mandarin for decades. However, the results of previous studies and the current study, to various degrees, disagree with each other. For instance, Chen (1991a) and the current study

Informant's Age in 1987

19-22 25-29 32-36 38-39 40-49

%

30 40 50 60 70 80 90

[eng] to [en]

[in] to [ing]

Figure 6-11 Percentage of the convergences [ ´N] to [´n] and [in] to [iN] in each age group in Chen (1991a)

18,1918 Due to the functional limit of the graphics software, the IPA symbol [´] cannot be shown in the figures. In Figure 6-11 and Figure 6-12, [e] is used as a substitute of [´].

observed different results from Kubler (1985) and Tse(1992) in the convergence direction of [iN]. Both Kubler and Tse reported a convergence from [ iN] to [in], while Chen (1991a) and the current study observed [ in] to [iN]. However, although both Chen (1991a) and the current study agreed that [ ´N] to [´n] and [in] to [iN]

were the two predominant syllable-final nasal convergence s in Taiwan Mandarin, there was no agreement on which is likely the first to lose its distinction. In Chen (1991a), [ in] to [iN] was ahead, while in the current study it was [´N] to [´n] that was in the leading position.

1951-1960 1981-1990

%

25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65

[eng] --> [en]

[in] --> [ing]

Figure 6-12 Percentage of the convergence s [ ´N] to [´n] and [in] to [iN] in the two age groups in this study

(age 44-53) (age 14-23)

In fact, not only in real speech, the instability of Chinese syllable-final nasal also exists in rime books and dictionaries. Chen (1991b) pointed out that syllable-final nasal convergence was one of the two major trends of the developments in Mandarin dialects (p.140)

20. Chen (1991b) further analyzed the nasal endings of modern Beijing

21Mandarin in three representative systems, they were

(1) the 1932 ‘Standard National Pronunciation’ (as recorded in Guoyu Cidian, 1947, and Chongbian Guoyu Cidian, 1979), which is a revised version of the

‘New National Pronunciation’ of 1924; (2) the 1963 revision known as the

‘Preliminary Draft for the General Table of Standard Pronunciation of Words with Variant Sounds’; and (3) the 1985 revision known as ‘ The Table of Standard Pronunciation of Words with Variant Sounds in the Common Speech (p.140).

Dictionaries and rime books are usually slow in recognizing sound change, while the dictionaries and rime books studied in Chen(1991b) still indicated the instability of syllable-final nasals. For instance, the syllable-final [in] in min3 (dishes), and xin1 (fragrance), split into both [ in] and [iN] readings in the 1932 system but were both later officially recognized as ending in [ in]; [´n] in both zhen1 (loyalty) and gen4 (long-lasting) were the results of a change from [ ´N]. The pronunciation of bin1 (betel)

20 The other trend studied in Chen (1991b) is the convergence of retroflex and dental obstruents.

had gone through a [ in]/ [iN] two-reading stage in the 1932 system and had later changed into [ iN] ending in the 1963-85 system. It is noteworthy that these written records of sound change also agreed with previous studies that the pairs [ in] / [iN]

and [ ´N]/ [´n] were the most unstable ones .

6.4 The Koineization of Taiwan Mandarin

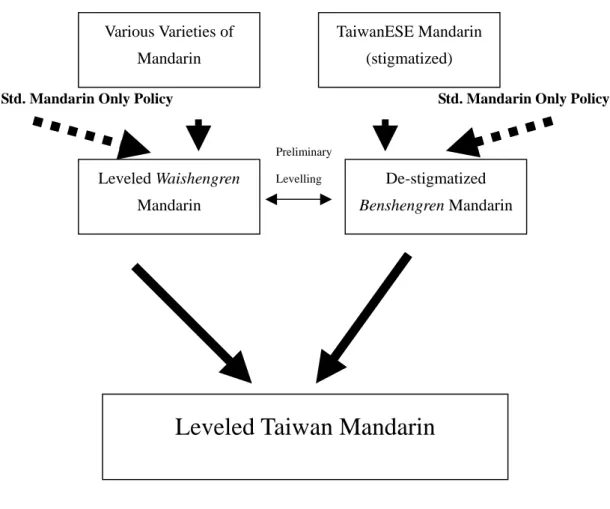

As Figure 6-13 indicates, Taiwan Mandarin is the result of the contacts and mixtures of various varieties of Mandarin, including the stigmatized Taiwanese Mandarin, which, though, is an acquired variety of Mandarin. Some previous studies applied the concepts of pidgin and creole on Taiwanese Mandarin and Taiwan Mandarin. For instance, Teng (2002) argued that Taiwan Mandarin was a mixture of both pidgin and creole as it performed as a mixture of “bit of both and not entirely either” (p.233) Not distinguishing the stigmatized Taiwanese Mandarin and the stabilized Taiwan Mandarin, Teng (2002) further proposed a continuum of “Taiwanese Mandarin”

22, with the stigmatized Taiwanese Mandarin and the stabilized Taiwan Mandarin at both extremes. Tseng (2003), on the other hand, proposed that Taiwanese Mandarin was a pidgin and Taiwan Mandarin was a creole. The current study suggests that neither the notion of pidgin nor the notion of creole can authentically reflect the

22 Teng (2002) broadly referred to the Mandarin spoken in Taiwan as “Taiwanese Mandarin”.

formation and status of Taiwan Mandarin. Unlike Teng (2002) and Tseng (2003), the current study argues that the stabilized Taiwan Mandarin is better categorized as a koine, or at least in the process of koineization.

Figure 6-13 The formation of Taiwan Mandarin

Preliminary Levelling

Std. Mandarin Only Policy Std. Mandarin Only Policy

Various Varieties of Mandarin

TaiwanESE Mandarin (stigmatized)

Leveled Waishengren Mandarin

De-stigmatized Benshengren Mandarin

![Figure 6-11 Percentage of the convergences [ ´N] to [´n] and [in] to [iN] in each age group in Chen (1991a) 18,19](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7259399.67483/17.892.151.676.539.930/figure-percentage-convergences-n-n-age-group-chen.webp)

![Figure 6-12 Percentage of the convergence s [ ´N] to [´n] and [in] to [iN] in the two age groups in this study](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7259399.67483/18.892.140.611.599.960/figure-percentage-convergence-s-n-age-groups-study.webp)