0 2 7

Introduction

In total there are six million caregivers across the UK, of whom around one million are looking after somebody for more than 50 hours each week (The Princess Royal Trust for Caregivers Centre, 2001). A caregiver is someone who, without payment, provides help and support to a friend, neighbor or relative who could not manage otherwise because of frailty, illness or disability (The Princess Royal Trust for Caregivers Centre, 2001). They are sometimes known

as ‘informal’ caregivers (The Princess Royal Trust VOCAL Caregivers Centre, 2001). Scottish Census (2001) indicated that more than 16,310 Chinese people lived in Scotland. The Chinese population has continued to increase since that time. Therefore, the Chinese community has gradually drawn researchers’

interest in general but more particularly that of the present author given her own background of coming to Edinburgh from Taiwan to study.

A comparison of the burdens and coping strategies of the primary caregivers of elderly patients in Scottish and Chinese communities: a

pilot study

Assistant Professor, Cardinal Tien College of Healthcare & Management

◎Mei-Chun Lin

Abstract

The overall aim of this study was to investigate the burdens and coping strategies of the primary caregivers of elderly patients in Scottish and Chinese communities in Edinburgh. The design of study was carried out by a cross-sectional survey.

The total sample consisted of twenty-two participants that included 10 Scottish and 12 Chinese. Data were collected using questionnaires. These collected demographic data as well as a 15-item Caregiver Burden Scale and a 29-item Coping Scale.

Three types of burden, namely general, which included physical and financial aspects, emotional, and isolation burden, and the frequency of use of each type of coping strategy. These were emotive, evasive, optimistic, supportant, and confrontive coping strategies. Findings indicated that Scottish caregivers had higher burden scores (especially isolation burden) than those in the Chinese group. Both groups preferred to use optimistic coping strategies more often and evasive coping was least used.

Generally, Scottish caregivers had higher frequency of use each coping strategy than the Chinese did.

Corresponding author:Mei-Chun Lin

No.112, Min-Zu Rd., Sin-Dian City,Taipei 23143,Taiwan

The overall purpose of this study is to investigate the caregivers’ burdens and their coping strategies.

Professional nursing care is supposed to be focused on the patient, but this involves the wider context in which the patient lives. Since there is little literature that looks specifically at this area, particularly when it is applied to those of different cultural backgrounds, the study will contribute to the identity of the needs of such caregivers. This interest is shown for example, by the City of Edinburgh Council authorities issuing minority ethnic community care plans following their undertaking a project which looked at ethnic minorities (City of Edinburgh Council, 1997). The care plans covered issues for most of the resident minority ethnic groups in the City. These included older people, demonstrating that the authority was attempting to develop their work in this area, continuing the commitment of the old regional authorities.

Literature review

1. Cultural differences between the Scottish and Chinese communities

These two communities have radically different cultures. The ways, in which these cultures affect burden and coping strategies, are as follows:

(1) Scottish community

In the United Kingdom, Green (1988) found that around 6 million caregivers were looking after frail older people, younger people with physical disabilities, people with learning disabilities, and people with a mental illness. Martin et al. (1988) also indicated that 4 million informal caregivers were caring for people with significant disabilities. The discrepancy between these two figures might due to

different populations. The population of former survey included older people and younger people while the latter one only focused on elderly people. Thus, the total numbers in their samples were uneven. Caring is usually defined as a woman’s role, an expansion of the traditional responsibilities of a wife or daughter in Western societies (Chafetz & Barnes, 1989). Qureshi and Walker (1989) found that daughters and daughter- in-law contributed the largest group of caregivers in the United Kingdom. In this connection when considering the Scottish literature this is not seen as having a particularly negative consequence.

(2) Chinese community

Most Chinese families today adhere to traditional notions of filial piety. Chinese women have culturally- defined gender roles which strongly impact on their caring practices. The Chinese culture has preserved the longstanding Chinese tradition that the wife, adult daughter and daughter-in-law, particularly the wife of the eldest son, are expected to be the primary caregivers (Liu, 1995). The negative consequences of caring in the Chinese culture have been documented.

These include the deterioration of the caregivers’

physical and mental health; the restriction of their free time and freedom; economic strains including loss or curtailment of employment; and there are detrimental effects on the caregivers’ marital, family, and social relationships (Tang, 1991). Changes in family composition are very influential on the provision of care given to dependents. It is also reasonable to assume that the family composition will in turn be influenced by culture (Wang, 1994).

2. Burden

Caregiver burden encompasses day-to-day adjustment, change and it can prevent caregivers from attending to their own needs (Graham et al. 1997).

0 2 9

‘Caregiver burden’ was first defined in research in the 1960s. George and Gwyther (1986) expanded that definition as being;

“…the physical psychological, or emotional, social, and financial problems all related to caregiver burden by family members caring for impaired older adults” (p.253).

Chou (2000) proposes a further conceptualization of caregiver burden, identifying the caregiver’s subjective perception of interaction between care demand and care provision, and further relating dynamic change and overload to multidimensional phenomena (the bio-eco-psycho-social continuum).

Hamilton and Hoenig (1966) were the first researchers to make a distinction between objective and subjective dimensions of burden. The distinction has been used with some consistency to this day.

Objective burden refers to the negative effects of the illness on the household and the caring demands placed on family members. For examples, negative consequences such as physical problems, financial difficulties, and household tension (Dobson &

Middleton, 1998; Read, 2000; Blacher, 2001; Brannan

& Heflinger, 2001). On the other hand, subjective burden refers to the caregivers’ or family member’

s personal appraisal of the situation and the extent to which individuals perceive they are carrying a heavy load which include emotional distress caused by disturbing behaviors, feelings of loss, fear, anxiety, and embarrassment (Braithwaite, 1992; Borycki, 2001; Brannan & Heflinger, 2001).

(1) Gender of caregivers associated with caregiver burden

Primary caring is usually seen to be a woman’

s work (Penrod et al., 1995). Gender differences are believed to influence the amount and type of care

provided, access to social resources that may alleviate caregiver burdens, and appraisal of the caring experience (Miller, 1990). It has been documented that the majority of caregivers are women (Hogan, 1992).

Miller and Cafasso (1992) indicated that female caregivers were more likely to carry out personal care and household tasks and more likely to report greater burden. The amount of burden experienced by female caregivers of older adults depends on the availability of resources, family support, the type of illness of the care recipient, and living arrangements (Wykle, 1994). Female caregivers of people with dementia reported higher levels of caregiver burden than male caregivers (Moriz et al., 1989; Lutzky & Knight, 1994; Penrod et al., 1995; Chiu et al., 1996; Dennis et al., 1998; Yee & Schultz, 2000; Adams et al., 2002;

Scharlach et al., 2006).

(2) Age of caregivers associated with caregiver burden

Some studies have evaluated the relationships between caregivers’ age and burden. The younger the age of caregivers, the increased stigma and fear for their own as well as the ill relatives’ safety would be (Pickett et al., 1995; Greenberg et al., 1997).

Caregivers at the other end of the age range expressed interestingly similar feelings. Weng (1998), Liu et al. (1998) and Cain and Wicks (2000) indicated that the caregivers had much more burdens if they were over 60 years old. However, these findings were not necessarily consistent since there were three studies that found no consistent relationships between caregivers’ age and burden (Liu, 1992; Reinhard, 1994; Zhong, 1998; Croog et al., 2006).

3. Coping strategy

Coping has been defined as constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific

demands that tax or exceed a person’s resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1995). They identified two functions of coping: problem-focused and emotion- focused. Problem-focused coping strategies are similar to problem-solving tactics, which include defining the problem, finding the solutions, and carrying out the change (i.e. to alter or manage the situation in an active and constructive way). It implies an objective, analytic process that is focused primarily on the environment; problem-focused coping also includes strategies that are directed inward. A number of cross-sectional quantitative studies focus on the effectiveness of coping strategies of caregivers of persons with dementia and found that the use of problem-focused coping is related to less psychological distress (Haley et al., 1987; Vitaliano et al., 1987; Pruchno & Resch, 1989; Almberg et al., 1997; Kramer, 1997; O’Rourke & Wenaus, 1998). On the other hand, emotion-focused coping strategies are directed toward decreasing emotional distress (i.e. to relieve the emotional impact of the stressful situation by using thoughts and indirect actions). It should be more commonly used when events or situations are not changeable (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Some quantitative cross-sectional studies found that using emotion-focused coping was related to greater depression (Pruchno & Resch, 1989; Haley et al., 1996) and high levels of stress (Knight et al., 2000) among caregivers of persons with dementia.

(1) Gender of caregivers associated with their coping strategies

Several research reports have been done to compare the gender differences in the coping responses. Noelker and Wallace (1985) indicated that women were more involved in personal care as compared with men. Furthermore, women tended to

use maladaptive avoidance coping (Billings & Moos, 1981) and less effective coping methods (Pearlin

& Schooler, 1978). On the other hand, men were considered as more active copers and they had greater internal locus of control (Siegler & George, 1988).

Moreover, men used a more active mastery in their coping efforts (Billings & Moos, 1981).

(2) Age of caregivers associated with their coping strategies

Halstead and Fernalen (1994) found that older caregivers easily adopted the emotion-focused coping strategies, but young caregivers adopted the problem-focused coping strategies such as looking for social resources. Picot (1995) conversely found that the older caregivers used less emotion-focused coping strategies such as avoiding problems and self-blaming. In addition, other studies found no relationship between the age of caregiver and their coping strategies (Billings & Moos, 1981; Oumei, 1993; McConaghy & Caltabiano, 2005).

(3) Education of caregivers associated with their coping strategies

Billings and Moos (1981), and Oumei (1993) found that Taiwanese caregivers who received higher education tended to adopt problem-focused coping strategies. Luo (1992) found that the caregivers with lower education level adopted emotion-focused coping strategies. However, Lin (1996) found that there was no relationship between them. de Vegt and collengues (2004) found that caregiver’s education level was associated with their coping strategies in managing caregiving situation. They also reported that caregivers who had a high education level tended to use a supportive approach.

Methods

0 3 1

This study focused on investigating the burdens and coping strategies of the primary caregiver of outpatients in a Scottish and Chinese community. The specific research questions as following 5 specific questions:

(1) What are the burdens of primary caregivers in the two communities?

(2) What are the differences of burdens in the two communities?

(3) What are the coping strategies of primary caregivers in the two communities?

(4) Do the patient demographics influence their caregivers’ burden and coping strategies?

(5) Do the caregiver demographics influence their burdens and coping strategies?

The questionnaires were compiled to collect data for the pilot study. The self-reporting questionnaires were designed in three parts. The first part gathered demographic data; the second and third parts comprised a Caregiving Burden Scale (CBS), and the Coping Scale (CS). Internal consistency coefficients of CBS were range from .80 to .96. The Cronbach alpha reliability of CS was from .88 to .94. Content validity of CBS and CS were established by external experts.

The CBS, which has three parts, the topics investigated are the general burden (8 items, including physical and finance burden), the emotional burden (3 items), and the isolation burden (4 items). These items of the general burden investigate caregivers’ feeling of chronic fatigue, how they adapt their physical health, and the family finances related with caregivers’

burden. The emotional burden items are designed to investigate caregivers’ positive and negative feelings during caring their relatives. The isolation burden items are to investigate caregivers’ social condition.

These have been designed after comparing several other scales (Gerritsen & Van Der Ende, 1994; Weng, 1998; Goldstein et al., 2000). The technique employed to measure CBS is by the use of a Likert scale which is rated on a four-point scale showing how much they thought they knew about a specific theme (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Respondents are asked to indicate the degree to which they agree or disagree with the opinion expressed by the statement. The key component questions are including posed in different ways which positive and negative statements.

The CS is designed to assess coping mechanisms with numerous physical, emotional, and social stressors. This scale has 29 items, which include cognitive and behavioral coping strategies: emotive, confrontational, evasive, optimistic, fatalistic, and supportant coping strategies. The technique of measuring CS is also by use of a Likert scale which is rated on a four-point scale (never to always).

All the items offer different ways to caregivers that investigate their coping strategies to deal with burdens. This has been designed after comparing several other scales (Jalowiec et al., 1984; Folkman &

Lazarus, 1988; Lin, 2000).

The process of data collection was the researcher participated in caregivers’ meetings to introduce herself and to explain what their involvement in the research project would be. Both the Scottish and Chinese communities used the same questionnaire to collect data, but in different languages. However, for the Chinese community, it was found that face to face interview was necessary since most of Chinese participants were illiterate.

Sample

The total number of caregivers of these elderly patients in both samples was 15 women (68%) and

7 men (32%). The Scottish Group consisted of 10 (7 women and 3 men) while there were 12 (8 women and 4 men) in the Chinese group. In the Chinese group the mean age of the caregivers was 70 years (ranged from 45 to 78 years). This is not a surprising finding given that they were predominately related to these elderly people. Interestingly the Scottish group was lower by some ten years (60 mean) years because there were far more sons and daughters looking after Scots than in the Chinese group. The relationships of the primary caregivers and elderly patients were 4 wives, 1 husbands (50 % spouses), 3 daughters, and 2 sons in the Scottish group while there were 6 wives, 4 husbands (83% spouses), and 2 daughters in the Chinese group. This result showed that mostly caregivers were spouses in both of two groups. The education levels of the caregiver were 30% (n=3) with college or university degree, 10% (n=1) standard grades, 60 % (n=6) no qualifications in the Scottish group which there were 25% (n=3) with college or university degree, 17% (n=2) standard grades, 58

% (n=7) no qualifications in the Chinese group. The average year of being a caregiver was 7.8 years in the Scottish group while it was 8.83 years in the Chinese group. The Chi-Square test for homogeneity of these two groups of sample showed there was no significant different as a normal distribution.

Ethical considerations

The consent form and information sheets were developed for participants who were to be involved in the research project. These two documents clearly described the purpose of this study, the techniques of collecting data, and what information was needed and their rights such as protecting their privacy, data and freedom to withdraw at any stage. All respondents have given written consent.

Results

1. Description of caregiver burden in two communities

This section will address the experiences of caregiver burden as described by all the caregivers.

It will use three general headings that have been identified in the literature (Gerritsen & Van Der Ende, 1994; Weng, 1998; Goldstein et al., 2000). In the combined group (n=22) 32%, had high burden scores but there was a predominance of the Scottish group (n=5). Therefore, this means that generally the Scottish group has higher burden scores than the Chinese.

Three kinds of burden were investigated in this study, namely general, emotional and isolation.

The items, which measured these, were separated out and mean scores were computed for each. The mean burden score is 3.14 in each type of burden for both groups. These findings show that the isolation burden of the Scottish was the highest. When the two groups were separated out it also demonstrated that the Scottish caregivers suffered a higher score than the Chinese. These findings may have been influenced by the fact that the Chinese participants were interviewed, because of their lack of English, and they were therefore less likely to give extreme answers than the Scottish group who returned postal questionnaires.

Figure 1 shows the different genders of caregivers in relationship to the burden scales in both groups (the left: Scottish group, the right: Chinese group). The important finding is that in the Scottish Group male caregivers suffer higher levels of burden than the women do. This can be explained by the fact

0 3 3

that the male caregivers who responded gave extreme responses to the appropriate items. However, amongst the Chinese there is a different picture, which reveals

that female caregivers have higher scores than the men but then there are more of them in the sample.

2. Coping Strategies adopted by caregivers

The Coping Scale in a Likert Scale format has 29 items, which includes cognitive and behavioral coping strategies: emotive, confrontive, evasive, optimistic, and supportant coping strategies (Jalowiec et al., 1984; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Lin, 2000). The items relating to each of the strategies were separated out and a score was computed for the total group.

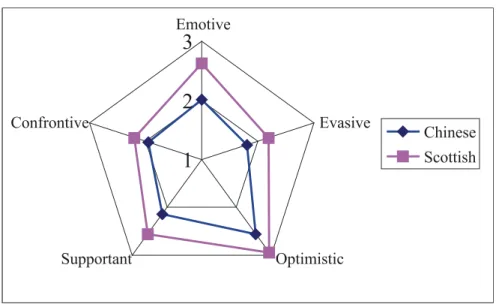

In Figure 2, score 1 means sometimes using the strategy, 2 usually, and 3 means always using coping

strategies. This Figure then shows that both groups of caregivers preferred to use optimistic coping strategy, by which they meant that all would eventually would be well and least likely to use evasive strategies, which means that they did not want to face the problems. Since these are two sides of the same coin this is not surprising. The Scots had higher scores in coping strategy, again a possible result of how the data were collected.

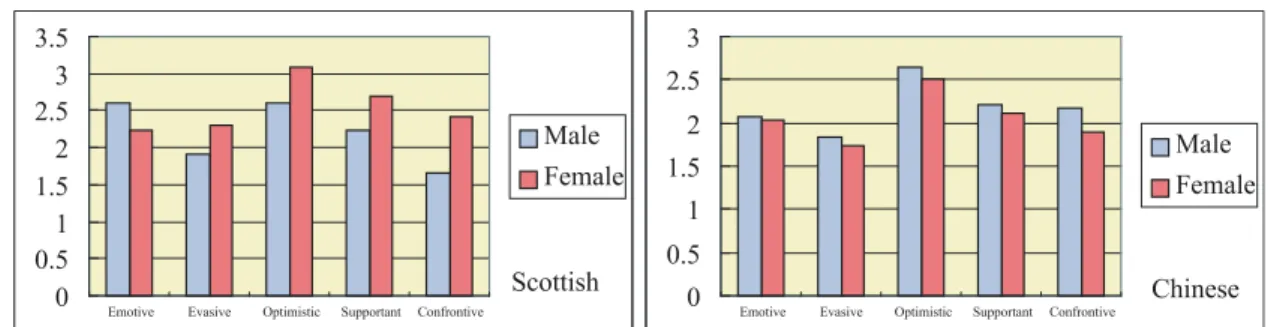

Figure 3 shows the frequency of the use of each type coping strategy by the men and women respectively in the two groups (the left: Scottish

group, the right: Chinese group). It demonstrates that female Scottish caregivers as well as the Chinese male caregivers prefer using optimistic coping strategies.

Figure 1: Different gender of caregivers on burden scores in two groups

Figure 2: The distribution of coping strategies in two groups

3. Demographic characteristics of caregivers associated with caregiver burden in two communities

The relationships between caregivers’ gender and their burden were discussed in the pervious section.

Moreover, the relationship between caregivers’

education levels and their burden. Interestingly, the Scottish caregivers with high education had more burden then others with no educational qualification.

It might be that caregivers with high education think too much and profoundly to influence the burden. On the other hand, there were equal burden scores on the different educational levels in the Chinese group.

The data were manipulated by running a comparison of caregivers’ age, education levels, and the length of caring related to their burden using an

Independent T-test (two-tailed), Pearson Correlation, and Spearman Correlation. Those findings show that there were no significant differences.

4. Demographic characteristics of caregivers associated with caregiver coping strategies in two communities

The data were manipulated by running a comparison of caregivers’ gender, age related to their coping strategies using an Independent T-test (two- tailed), Pearson Correlation, and showed that there were no significant differences. Moreover, there was a correlation between the education levels of caregivers and their coping strategy scores, which was significant to the level of 0.01 using a Spearman Correlation (Table 1).

Table 1: Spearman Correlation between caregivers’ education and their coping strategies

Variables Education Coping

Education 1 0.757**

Coping 1

** Correlation is significant at the .01 level; N=22.

Discussion

1. Demographic characteristics of caregivers related to caregiver burden in two groups

Several factors have been showed that there were significant differences between the burdens

of caregivers when related to their demographic characteristics such as gender, age, education, and living with the relative for whom they care. Another dependent variables such as caregivers’ self-health condition, financial problem, supporting resources, and impacted family function were important Figure 3: The frequency of using each type coping strategy on different gender of caregivers

0 3 5

predictors for caregivers’ burden (Liu et al., 1998).

70% (n=7) of Scottish caregivers suffered diseases while 67% (n=4) of Chinese caregivers had the problem. The major disease that the caregivers suffered was arthritis. Needless to say, the caregiver’s health conditions were directly related to their burden since the arthritis was one of the chronic diseases.

Generally, the Scottish group had higher burden scores than the Chinese. It should be noted that 70%

(n=7) Scottish caregivers had financial problems resulting from their providing care. Especially, the Scottish male caregivers had higher scores in each type of burdens than the women. Similar results have been reported by Goldstein et al. (2000) and Samele and Manning (2000). It is an interesting finding that only three Scottish male caregivers (relationship with patient: one spouse and two sons) participated in this study and they all had suffered high levels of burden.

It is possibly because men had the responsibility of earning money to support their own families as well as their parents. Besides, men more commonly conceal their emotions. This aspect of their personalities may have inherently increased the burden.

Another aspect of burden relates to the physical nature of caring. The predominant Chinese patients’

condition that required increased care was arthritis.

This inevitably means that sufferers experience pain, immobility, and problems of sleeping as well as emotional problems. All of these are very demanding on the abilities and physical strain for caregivers. On would expect that such conditions would be related to increased burden scores. The demands, which faced the Scottish caregivers’ group in the main, related to mental health problems. These are very demanding emotionally especially in instances where the patient is not aware of their surroundings or who is caring

for them as well as increased problems of security.

Therefore when one considered the realities which these caregivers faced one is not surprised that their levels of burden though expressed differently were high.

The highest scores of the isolation burden were those achieved by Scottish male caregivers while the Chinese male caregivers had the lowest scores.

Given the patterns of how care is provided this is not a surprising finding. Caring for patients inevitably limits the caregivers’ social activities. Caregivers will be less able to go anywhere that they might wish or to enjoy their holidays since they would have to make complicated or expensive arrangements to provide continuity of care. There is also the likelihood of their being worried about the patient when they are far away. Besides, they will be less able to invite their friends’ home during the period of caring for the patient. Therefore, this could also increase their sense of isolation as well as their emotional and general burden. The low Chinese scores are interesting because these caregivers are part of a very close knit community in a foreign country. Therefore, they did not share feelings of isolation, however it might be noted that there were no Chinese sons in the sample and so some of the explanations for the sense of isolation experienced by the Scots would not hold true for the Chinese.

On the other hand, it is important to note that Chinese female caregivers suffered a heavier burden than male ones. This finding is similar to those reported by Miller and Cafasso (1992), Penrod et al.

(1995), Chiu et al. (1996), and Dennis et al. (1998).

This is because the women do absolutely all of the caring duties including shopping, cooking, and laundry as well as physical and emotional care for

elderly patient whereas the males have some help with at least some of these activities.

Moreover, the Chinese female caregivers showed the highest scores of emotional burden. The outward signs or evidence for this were activities such as becoming angry easily, feeling nervous or depression, and concerning worrying about the health of their relatives. This is not surprising since it is generally believed that women are more sensitive and emotional than men. Thus, this personality trait of women might increase caregivers’ burden.

The relationship between the caregiver’s educational levels and their burden was discussed by previous studies (Yang, 1990; Liu, 1992; Liu et al., 1998). In the current work, the Scottish caregivers with high education had more burden than others and vice versa. This finding is interesting in that caregivers with high education might think too much to cause their burden and be able to work out the consequences. It should be noted that most of Chinese caregivers could not speak and read English. It makes them more difficult to live and to care for a patient in a foreign country. However, Chinese caregivers’

group showed that despite differences in levels of education all shared equal burden scores. This may well result from differences of culture since the Chinese tend to want to say only good things and do not want to be seen to be having problems. Therefore, it is possible that they do in fact experience a sense of burden but they simply do not express it, even to a researcher.

The age of caregivers was not related to their burden scores in both cultural groups and caregivers’

burden had no relationship with receiving helps from others. These were investigated by using an Independent T-test (two-tailed) and showed that there

were no significant difference. The relationships between length of caring and caregivers’ burden were showed no significant difference by using a Pearson Correlation. It might be due to the small numbers in the samples and the involvement of the interviewer with the Chinese group during the data collection.

The results of current study were different from pervious studies (Halstead & Fernsler, 1986, Shin

& Tam, 1996; Weng, 1998; Liu et al., 1998; Cain

& Wicks, 2000) which they found that the age of caregivers’ was associated with their burden and the help supports would affect caregivers’ burden. The small samples of population in the current study resulted in the difference and made it difficult to investigate in this subject.

2. Demographic characteristics of caregivers related to caregivers’ coping strategies in two groups

There are many factors associated with caregivers’ coping strategies. Five types of coping strategy have been defined in this study, arising from the literature that were emotive, evasive, optimistic, supportant, and confrontive coping strategies (Jalowiec et al., 1984; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Lin, 2000). Generally, Scottish caregivers made more use of each of the coping strategies than the Chinese.

All of caregivers preferred to use optimistic coping strategy when dealing with their burden. This finding showed they had a positive attitude towards facing their problems. In addition, the evasive coping strategy was the least frequently used mechanism by both groups. Since they have a sense of duty and therefore they feel that they cannot run away there is inevitably a resistance to the notion that they will evade dealing with their burden. As we have already noted this is particularly striking in the way that the

0 3 7

Chinese are brought up.

The only exception to this was a correlation between the education levels of caregivers and their coping strategy scores which was significant to the level of 0.01 using a Spearman Correlation. Similar results have been reported by Bollings and Moos (1981), Oumei (1993), and Luo (1992). Different education levels of caregivers would influence their coping strategies dealing with the burdens.

However, the relationships between the gender and age of caregivers and their coping strategies showed no significant correlations by using an Independent T-test (two-tailed). These findings were different from pervious studies (Lutzy & Knight, 1994; Picot, 1995; Lindqvist et al., 2000) which the caregivers’ gender, age, and their coping strategies were related to each other. Again it is possible that the reason for the lack of correlations arises from the fact that the total sample is too small.

Conclusions

In this pilot study, it was found that all the caregivers were predominantly female and most patients were looked after by their spouses and given their ages this means that the burden experienced was harder to cope with. The main different demographic characteristics of the two sample groups were the age and the education level. The caregivers and patients in the Chinese community were found older and less well educated than those in Scottish community.

As to burden, generally, the Scottish group had higher burden scores than the Chinese group, but this may have been influenced by their almost universal financial problems. Scottish caregivers suffered isolation burden while Chinese caregivers suffered emotional aspect of burden as a result of providing care. In addition, The Scottish male

caregivers suffered more burden than the females.

Despite the differences of burdens they suffered, most of caregivers were found that they preferred to use optimistic coping strategies instead of evasive coping strategies in both two groups.

By using the statistic method of a Spearman Correlation, the relationship between caregiver’s education level and their coping strategies was the only one that showed significant correlation. It was also important to realize that the Chinese caregivers’

education level was directly related to their ability to receive information, especially in a foreign country.

It suggested that the social support system would be incomplete without the consideration of minority group.

Limitations of the research

As for the sampling, the fact that the researcher did not have access to NHS patients or their caregivers meant that more time had to be taken to set any project up. The samples were found in the caregiver centre which supports and provides some services such as advice, social welfare, group meeting or discussion, and some information for caring patients. Moreover, a cross-sectional study does not always manage to capture the changing nature of the burdens and coping strategies.

References

Adams, B., Aranda, M. P., Kemp, B., & Takagi, K.

(2002). Ethic and gender differences in distress among Anglo American, African American, Japanese American, and Mexican American spousal caregivers of persons with dementia.

Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 8(4), 279-

301.

Almberg, B., Grafstom, M., & Winblad, B. (1997).

Major strain and coping strategies as reported by family members who care for aged demented relatives. Journal of Advanced of Nursing, 26, 683-691.

Almberg, B., Jansson, W., Grafstom, M., & Winblad, B. (1998). Differences between and within genders in caregiving strain: a comparison between caregivers of demented and non- caregivers of non-demented elderly people.

Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(4), 849-858.

Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1981). The role of coping responds and social resources in Attenusting the stress of life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(2), 139-157.

Blacher, J. (2001). Transition to adulthood: mental retardation, families, and culture. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 106(2), 173-

188.

Borycki, E. (2001). Understanding caregiver burden:

issues and considerations Perspective, 25 (2), 6-13.

Braithwaite, V. (1992). Caregiving burden: making the concept scientifically useful and policy relevant. Research in Aging, 14(1), 3-27.

Brannan, A. M., & Heflinger, C. A. (2001).

D i s t i n g u i s h i n g c a r e g i v e r s t r a i n f r o m psychological distress: modeling the relationship between child, family and caregiver variables.

Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10(4), 405-418.

Cain, C. J., & Wicks, M. N. (2000). Caregiver attributes as correlates of burden in family caregivers coping with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Family Nursing, 6(1), 46-68.

Chafetz, L., & Barnes, L. (1989). Issues in psychiatric caregiving. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 3, 61-68.

Chiu, L., Pai, L., Tang, K. Y., & Wang, S. P. (1996).

Family caregivers´ burdens and perceived need for home care services in the Taipei metropolitan area. Journal of Public Health, 15(4): 289-301.

(In Chinese)

Chou, K. R. (2000). Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 15(6), 398-407.

City of Edinburgh. (1997). Community Care Plan for the City of Edinburgh 1997-2000. Edinburgh:

City of Edinburgh Council.

Croog, S. H., Burleson, J. A., Sudilovsky, A., &

Baume, R. M. (2006). Spouse caregivers if Alzheimer patients: problem responses to caregiver burden. Aging & Mental Health, 10(2), 87-100.

de Vugt, M. E., Stevens, F., Aalten, P., Lousberg, R., Jaspers, N., Winkens, I., Jolles, J., & Verhey, F. R.

J. (2004). Do caregiver management strategies influence patient behaviour in dementia?

International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19, 85-92.

Dennis, M., O´Roruke, S., Lewis, S., Sharpe, M., &

Warlow, C. (1998). A quantitative study of the emotional outcome of people caring for stroke survivors. Stroke, 29, 1867-1872.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Manual for

0 3 9

the ways of coping questionnaire. California:

Consulting Psychologists Press.

George, L. K., & Gwyther, L. P. (1986). Caregiver well-being: a multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults.

Gerontologist, 26, 253-259.

Gerritsen, J., & Van Der Ende, P. (1994). The development of a care-giving burden scale. Age and Ageing, 23 (6), 483-491.

Goldstein, L. H., Adamson, M., Teresa, B., Down, K., & Leigh, P. N. (2000). Attributions, strain and depression in carers of partners with MND: a preliminary investigation. Journal of Neurological Sciences, 180, 101-106.

Graham, C., Ballard, C., & Sham, P. (1997). Carer´

s knowledge of Dementia, their coping strategies and morbidity. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12, 931-936.

Green, H. (1988). Informal carers: general household survey. London: OPCS Social Survey Division.

Greenberg, J. S., Kim, H. W., & Greenley, J. R. (1997).

Factors associated with subjective burden in siblings of adults with severe mental illness.

American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67, 231-

241.

Haley, W. E., Levine, E. G., Brown, S. L., &

Bartolucci, A. A. (1987). Stress, appraisal, coping, and social support as predictors of adaptational outcome among dementia caregivers. Psychology and Aging, 2(4), 323-

330.

Haley, W. E., Roth, D. L., Coleton, M. I., Ford, G.

R., West, C. A., Collins, R. P., & Isobe, T. L.

(1996). Appraisal, coping and social support as mediators of well being in black and white family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer´

s disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 64(1), 121-129.

Halstead, M. T., & Fernsler, J. I. (1994). Coping strategies of long-term cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 17(2), 99-100.

Hamilton, M., & Hoenig, J. (1966). The schizophrenic patient in the community and his effect on the household. International of Social Psychiatry, 12, 165-176.

Hogan, S. (1992). Care for the caregiver social policies to ease their burden. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 16(5), 12-16.

Jalowiec, A., Murphy, S. P., & Powers, M. J. (1984).

Psychometric assessment of the Jalowiec.

Coping Scale Nursing Research, 33(3), 157-

161.

Knight, B. G., Sliverstein, M., McCallum, T. J., &

Fox, L. S. (2000). A sociocultural stress and coping model for mental health outcomes among African American caregivers in southern California. Journals of Gerontology Series B:

Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55(3), P142-P150.

Kramer, B. J. (1997). Gain in the caregiving experience: where are we? What are we? What next? Gerontologist, 37(2), 218-232.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York:

Springer.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1995). Psychological stress and the coping process (2nd ed). New York: Springer.

Lin, K. C. (1996). Work values, coping strategies and work adjustment. Master Dissertation in Behavior Science. Taiwan: Gao-Xiong Medical School. (In Chinese)

Lin, J. C. (2000). Discussion of the burden and social services of family caregivers with demented

patients. Master Dissertation in Behavior Science. Taiwan: Gao-Xiong Medical School. (In Chinese)

Lindqvist, R., Carlsson, M., & Sjoden, P. (2000).

Coping strategies and Health-related quality of life among spouses of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, haemodialysis, and transplant patients. Journal of Advanced of Nursing, 31(6), 1398-1408.

Liu, X. E. (1992). Evaluate the conceptual of caring their relatives. Journal of Nursing, 39(3), 19-

23. (In Chinese)

Liu, Z. D. (1995). Female caregiver. Chinese Research in Gynecology, 9, 2-7. (In Chinese) Liu, C. N., Hwu, Y. J., & Lee, M. J. (1998). The

burden of primary caregivers´ of stroke patients at hospital and its related factors. Public Health, 25(3), 197-209. (In Chinese)

Luo, J. X. (1992). The discussion of the caregivers’

stress and coping strategies. Unpublished Master Dissertation in Social Worker. Taiwan: Don- Hawi University. (In Chinese)

Lutzky, S. M., & Knight, B. G. (1994). Explaining gender differences in caregiver distress: the roles of emotional attentiveness and coping styles.

Psychological Aging, 9(4), 513-519.

Martin, J., Meltzer, H., & Elliot, D. (1988). The prevalence of disability among adults. Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Disability Surveys. London: HMSO

McConaghy, R., & Caltabiano, M. L. (2005).

Caring for a person with dementia: exploring relationships between perceived burden, depression, coping and well-being. Nursing and Health Sciences, 7(2), 81-91.

Miller, B. (1990). Gender differences in spouse caregiver strain: socialization and role

explanations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 311-322.

Miller, B. M., & Cafasso, L. (1992). Gender differences in caregiving: fact or artifact.

Gerontologist, 32, 498-507.

Moriz, D. J., Kasl, S. V., & Berkman, L. F. (1989).

The health impact of living with a cognitively impaired elderly spouse: depressive symptoms and social functioning. Journal of Gerontology, 44, S17-27.

Nieswiadomy, R. M. (1998). Foundations of nursing research. California: Appleton and Lange.

Noelker, L. S., & Wallace, R. W. (1985). The organization of family care for impaired elderly.

Journal of Family, 6, 23-44.

O´Rourke, N., & Wenaus, C. (1998). Marital aggrandizement as a mediator of burden among spouses of suspected dementia patients.

Canadian Journal on Aging, 17, 384-400.

Oumei, K. (1993). The evaluation of the stress, coping strategies and mental conditions in stork patients’ female spouse. Unpublished Master Dissertation in Nursing. Taiwan: Kow-Fan University. (In Chinese)

Pearlin, L., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 19, 2-21.

Penrod, J. D., Kane, R. A., Kane, R. L., & Finch, M. D. (1995). Who cares? The size, scope, and composition of the caregiver support system.

Gerontologist, 34(4), 489-497.

Pickett, S. A., Greenley, J. R., & Greenberg, J.

S. (1995). Off-timedness as a contributor to subjective burdens for parents of offspring with severe mental illness. Family Relations, 44, 195-201.

Picot, S. J. (1995). Rewards, costs, and coping of

0 4 1

African American caregivers. Nursing Research, 44(3), 147-152.

Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Hungler, B. P. (2001).

Essentials of nursing research: methods, appraisal, and utilization. (5th ed.) Philadelphia:

Lippincott.

Pruchno, R. A., & Resch, N. L. (1989). Mental health of caregiving spouses: coping as mediator, moderator or main effect? Psychology and Aging, 4 (4), pp.454-463.

Qureshi, H., & Walker, A. (1989). The caring relationship elderly people and their families.

London: Macmillan

Reinhard, S. C. (1994). Living with mental illness:

effects of professional support and personal control on caregiver burden. Research in Nursing and Health, 17, 79-88.

Read, J. (2000). Disability, the family society listening to mothers. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Samele, C., & Manning, N. (2000). Level of caregiver burden among relatives of the mentally ill in South Verona. European Psychiatry, 15(3), 196-204.

Scharlach, A., Li, W., & Dalvi, T. B. (2006). Family conflict as a mediator of caregiver strain. Family Relations, 55(5), 625-635.

Scottish Census (2001). Scottish census Scotland.

Edinburgh: Scottish Office.

Shin, S. N., & Tam, O. K. (1996). Factors related to family function and stressors for caregivers caring the elderly with serious disease. Rong- Zong Nursing, 13(2), 138-147. (In Chinese) Siegler, I. C., & George, L. K. (1988). The normal

psychology of the aging male: sex differences in coping and perceptions of life events. Journal of Psychiatry, 16, 187-209.

Tang, L. Y. (1991). An exploratory study of burden

and related factors on caring for demented elders. Unpublished Master Dissertation in Nursing. Taiwan: National Taiwan University. (In Chinese)

The Princess Royal Trust for Carers Centre. (2001).

A carer guide. Edinburgh: The Princess Royal Trust for Carers Centre.

The Princess Royal Trust VOCAL Carers Centre.

(2001). What is a carer? Edinburgh: The Princess Royal Trust VOCAL Carers Centre.

Vitaliano, P. P., Maiuro, R. D., Russo, J., & Becker, J. (1987). Raw versus relative scores in the assessment of coping strategies. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 10 (1), 1-18.

Wang, H. H. (1994). The impact of caregiving role on women nursing implications. Journal of Nursing, 41(3), 18-23. (In Chinese)

Weng, Y. N. (1998). Burden of primary caregivers in home health care. Unpublished Master Dissertation in Nursing. Taiwan: National Taiwan University. (In Chinese)

Wykle, M. L. (1994). The physical and mental health of women caregivers of older adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 20, 48-49

Yang, P. J. (1990). The discussion of caregivers’

burden and needs with elderly dementia patients.

Unpublished Dissertation in Social Worker.

Taiwan: Don-Hawi University. (In Chinese) Yee, J. L., & Schultz, R. (2000). Gender differences in

psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers:

a review and analysis. Gerontologist, 40 (2), 147-164.

Zhong, J. Z. (1998). The discussion of primary caregiver needs and other related to factors with cancer patient. Unpublished Master Dissertation in Nursing. Taiwan: Yen-Man University. (In Chinese)