CHAPTER FOUR

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

4.1. Results and Analysis

For data analysis, the researcher used the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, version 13.0) to analyze the collected data. Firstly, in order to determine the effects of the independent variables of topic familiarity and reading proficiency on the dependent variables of reading comprehension, vocabulary gain and retention,

Paired-Samples t-tests were conducted, testing the effects of categorical independent variables of reading proficiency and topic familiarity on the three continuous

variables of reading comprehension, vocabulary gain and retention. And also to compare the effect of reading proficiency across high and low groups on reading comprehension, vocabulary gain and retention, an Independent-Samples t-test was conducted. In addition, the relationships among participants’ vocabulary size, reading proficiency, reading comprehension vocabulary gain and retention was examined by the results of Pearson correlations analysis

4.1.1. Overall Results

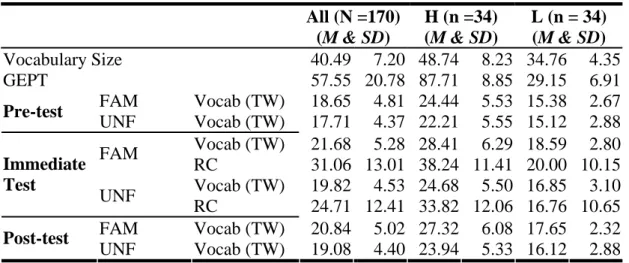

Table 4-1 is a summary table of overall results; the following findings can be drawn from the overall results in the Table 4-1.

1. Readers who read the more familiar text (Mean = 31.06) got higher scores in

reading comprehension than the less familiar text (Mean = 24.71). And the

difference showed significance, t(169) = 5.81, p = < .01; see Table 4-3.

2. For intermediate readers, they had higher reading comprehension scores of the more familiar text (Mean = 38.24) than of the less familiar text (Mean = 33.82), though the difference of reading comprehension scores across the two texts did not reach significance, t(33) = 1.71, p = > .05; see Table 4-3.

3. For elementary readers, they had higher reading comprehension scores of the more familiar text (Mean = 20.00) than of the less familiar text (Mean = 16.76), though the mean difference of reading comprehension scores across the two texts did not reach significance, t(33) = 2.00, p = > .05; see Table 4-3.

Table 4-1 A Summary Table of Overall Results All (N =170)

(M & SD)

H (n =34) (M & SD)

L (n = 34) (M & SD)

Vocabulary Size 40.49 7.20 48.74 8.23 34.76 4.35

GEPT 57.55 20.78 87.71 8.85 29.15 6.91

FAM Vocab (TW) 18.65 4.81 24.44 5.53 15.38 2.67 Pre-test

UNF Vocab (TW) 17.71 4.37 22.21 5.55 15.12 2.88 Vocab (TW) 21.68 5.28 28.41 6.29 18.59 2.80

FAM RC 31.06 13.01 38.24 11.41 20.00 10.15

Vocab (TW) 19.82 4.53 24.68 5.50 16.85 3.10 Immediate

Test

UNF RC 24.71 12.41 33.82 12.06 16.76 10.65

FAM Vocab (TW) 20.84 5.02 27.32 6.08 17.65 2.32 Post-test

UNF Vocab (TW) 19.08 4.40 23.94 5.33 16.12 2.88

Note. FAM = the familiar text; UNF = the unfamiliar text.

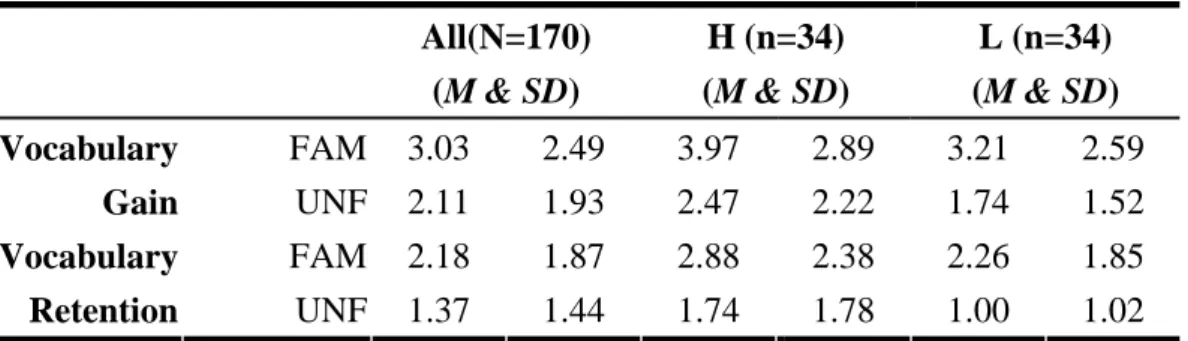

Table 4-2 is a summary table of vocabulary gain and retention. The following findings can be drawn from the overall results in Table 4-2:

4. Readers who read the more familiar text got significantly higher scores in

vocabulary gain (Mean = 3.03) and retention (Mean = 2.11) than the vocabulary

gain (Mean = 2.18) and retention (Mean= 1.37) in the less familiar text, but the

scores of vocabulary retention were weaker due to the attrition in vocabulary gain

over time, t(169) = 4.48, p < .01; t(169) = 5.05, p < .01; see Table 4-3.

5. For intermediate readers, they achieved higher vocabulary gain (Mean = 3.97) and retention (Mean = 2.88) in the more familiar text than in the less familiar text (Mean of gain = 2.47; Mean of retention = 1.74). And there were significant vocabulary gain and retention for H group in both texts. The scores of gain and retention while reading the more familiar text were significantly higher than those in the unfamiliar text, which meant their gain and retention disparity across the two texts reached significance, t(33) = 2.30, p < .05; t(33) = 2.17, p < .05; see Table 4-3.

6. For elementary readers, they also achieved higher vocabulary gain (Mean = 3.21) and retention (Mean = 2.26) both in the more familiar text and in the less familiar text (Mean of gain = 1.74; Mean of retention = 1.00). And there were significant gain and retention for L group in both texts. Noticeably, L group also had significant gain and retention in the less familiar text. The scores of gain and retention in the more familiar text were significantly higher than those in the unfamiliar text, which meant their gain and retention disparity across the two texts reached significance, t(33) = 3.91, p < .05; t(33) = 4.45, p < .05; see Table 4-3.

Table 4-2 A Summary Table of Vocabulary Gain and Retention All(N=170)

(M & SD)

H (n=34) (M & SD)

L (n=34) (M & SD)

FAM 3.03 2.49 3.97 2.89 3.21 2.59

Vocabulary

Gain UNF 2.11 1.93 2.47 2.22 1.74 1.52

FAM 2.18 1.87 2.88 2.38 2.26 1.85

Vocabulary

Retention UNF 1.37 1.44 1.74 1.78 1.00 1.02

Note. FAM = the familiar text; UNF = the unfamiliar text.

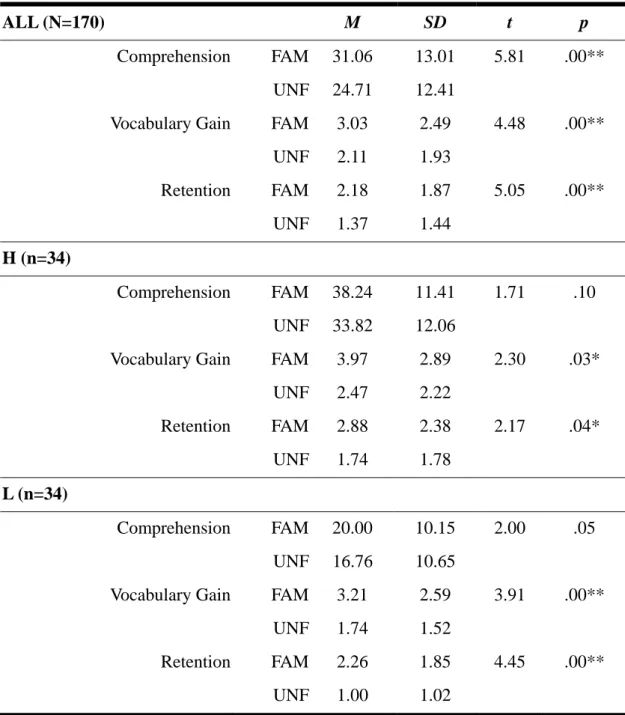

Table 4-3 A Summary Table of Paired-Samples t-tests

ALL (N=170) M SD t p

Comprehension FAM 31.06 13.01 5.81 .00**

UNF 24.71 12.41

Vocabulary Gain FAM 3.03 2.49 4.48 .00**

UNF 2.11 1.93

Retention FAM 2.18 1.87 5.05 .00**

UNF 1.37 1.44

H (n=34)

Comprehension FAM 38.24 11.41 1.71 .10

UNF 33.82 12.06

Vocabulary Gain FAM 3.97 2.89 2.30 .03*

UNF 2.47 2.22

Retention FAM 2.88 2.38 2.17 .04*

UNF 1.74 1.78

L (n=34)

Comprehension FAM 20.00 10.15 2.00 .05

UNF 16.76 10.65

Vocabulary Gain FAM 3.21 2.59 3.91 .00**

UNF 1.74 1.52

Retention FAM 2.26 1.85 4.45 .00**

UNF 1.00 1.02

Note. **p < .01, *p < .05; FAM = the familiar text; UNF = the unfamiliar text.

4.1.2. Comprehension of Different Topic Familiarity

Table 4-3 showed the descriptive statistics for reading comprehension of the

more and less familiar passages. The maximum and minimum of scores showed a

considerable range in proficiency across participants. The result showed that

participants have better reading comprehension score on the more familiar text. On

average, participants answered 62% (Mean = 31.1) of comprehension questions correctness of the familiar text, whereas participants answered 50% (Mean = 24.7) of correctness of the less familiar text. The total reading comprehension showed that most participants answer 55.77% (M = 55.77) correctness across the two texts.

The result of paired-samples t-test of reading comprehension of different topic familiarity (see Table 4-3) showed statistical significance, t(169) = 5.81, p = . < .01.

This result revealed that participants had higher reading comprehension of the more familiar text than of the less familiar text

4.1.3. Vocabulary Gain and Retention of Different Topic Familiarity Table 4-3 illustrated the descriptive statistics for the continuous dependent variable of vocabulary gain and retention. The mean score (Mean = 3.03) of vocabulary gain in the more familiar text was higher than that (Mean =2.11) in the less familiar text. This showed that participants achieved higher vocabulary gain in the more familiar text than in the less familiar text. And the differences between

vocabulary gain scores in the more and less familiar texts were statistically significant, t(169) = 4.48, p <.05; see Table 4-3). Also, the mean score of vocabulary retention

(Mean = 2.18) from the more familiar text was higher than that (Mean = 1.36) from the less familiar text. This showed that participants retained higher vocabulary gain in the more familiar text than in the less familiar text. And the differences between vocabulary retention scores in the more and less familiar texts were statistically significant, t(169) = 5.05, p <.05; see Table 4-3).

In short, the results above in Table 4-3 revealed that readers who read the

familiar text had higher and significant reading comprehension than the less familiar

text. Also, the results in Table 4-3 showed that readers who read the familiar text had

higher and significant vocabulary gain and retention than the less familiar text. These

findings conformed to the researcher’s expected outcome. Also as expected, the scores of vocabulary retention in both texts were lower due to the attrition in vocabulary gain over time.

4.1.4. Grouping by Reading Proficiency

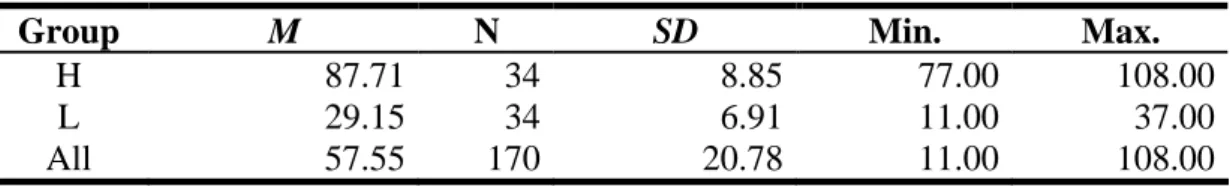

Table 4-4 provided descriptive statistics for the variable of English reading proficiency, revealing a considerable range in scores. The full mark for this GEPT reading proficiency was 120. The minimum score of participants was 11, and the maximum score was 108. Participants scoring over 80 can pass the GEPT reading proficiency test. Because the mean score was 57.6., it was clear averagely the scores of most participants are just at elementary level, in terms of reading ability.

Table 4-4 showed the grouping of high and low (H & L) groups categorized by scores of reading proficiency. The first and last 20% of participants (34 for each) were selected as high and low groups. The mean score of H was 87.71; the maximum score was 108, and the minimum was 77. The mean score of L was 29.15; the maximum score was 37, and the minimum was 11. On average, the high group passed 80 (elementary level) and were intermediate readers in this study; the low group got the score under 40, there were defined as elementary readers in this study.

Table 4-4 H and L Groups Divided by English Reading Proficiency

Group M N SD Min. Max.

H 87.71 34 8.85 77.00 108.00

L 29.15 34 6.91 11.00 37.00

All 57.55 170 20.78 11.00 108.00

Note. H Group (n = 34); L Group (n = 34); All = 170.

4.1.5. Paired-Samples t-tests on Reading Comprehension, Vocabulary Gain and Retention of Different Topic Familiarity

In order to determine the effect of the categorical independent variable of topic familiarity (familiar & unfamiliar texts) on the dependent variable of reading

comprehension, vocabulary gain and retention in the more and less familiar texts, Paired-Samples t-tests were conducted.

Table 4-3 revealed that H group achieved higher reading comprehension of the more familiar text than of the less familiar text (M

HF= 38.24 > M

HU= 33.82), though the mean difference did not reach significance, t(33) = 1.71, p >.05; see Table 4-3.

Similarly, Table 4-3 showed that L group achieved higher reading.

comprehension of the more familiar text than of the less familiar text (M

LF= 20.00 >

M

LU= 16.76), though the mean difference did not reach significance, t(33) = 2.00, p

> .05; see Table 4-3.

These results displayed that across both H & L groups, the scores of reading comprehension of the more familiar text were higher than of the less familiar text, though the difference between the two texts did not reach statistical significance.

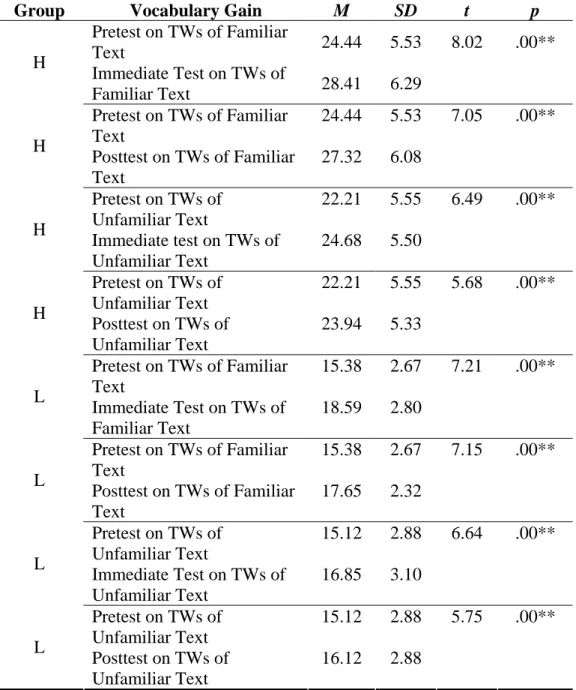

In another aspect, Paired-Samples t-tests were adopted to examine if there were significant vocabulary gain and retention in both texts across the H and L groups. In comparing the scores of the pretest on TWs of the familiar text to the scores of the immediate test, Table 4-5 showed that H group had significant vocabulary gain in the more familiar text, t(33) = 8.02, p < .01). And when comparing the scores of the pretest on TWs of the familiar text to the scores of the posttest, H group had

significant vocabulary retention in the more familiar text, t(33) = 7.05, p < .01. In the unfamiliar text, in comparing the scores of the pretest on TWs to the scores of the immediate test, H group had significant vocabulary gain in the less familiar text, t(33)

= 6.49, p < .01. And when comparing the scores of the pretest on TWs to the scores of

the posttest, H group had significant vocabulary retention in the less familiar text, , t(33) = 5.68, p < .01.

Table 4-5 Vocabulary Gain and Retention in Both Familiar and Unfamiliar Texts across H and L Groups (Paired-Samples t-test)

Group Vocabulary Gain M SD t p

Pretest on TWs of Familiar

Text 24.44 5.53 8.02 .00**

H Immediate Test on TWs of

Familiar Text 28.41 6.29

Pretest on TWs of Familiar Text

24.44 5.53 7.05 .00**

H Posttest on TWs of Familiar Text

27.32 6.08

Pretest on TWs of Unfamiliar Text

22.21 5.55 6.49 .00**

H Immediate test on TWs of Unfamiliar Text

24.68 5.50

Pretest on TWs of Unfamiliar Text

22.21 5.55 5.68 .00**

H Posttest on TWs of Unfamiliar Text

23.94 5.33

Pretest on TWs of Familiar Text

15.38 2.67 7.21 .00**

L Immediate Test on TWs of Familiar Text

18.59 2.80

Pretest on TWs of Familiar Text

15.38 2.67 7.15 .00**

L Posttest on TWs of Familiar Text

17.65 2.32

Pretest on TWs of Unfamiliar Text

15.12 2.88 6.64 .00**

L Immediate Test on TWs of Unfamiliar Text

16.85 3.10

Pretest on TWs of Unfamiliar Text

15.12 2.88 5.75 .00**

L Posttest on TWs of Unfamiliar Text

16.12 2.88

Note. **p < .01, *p < .05; H Group (n = 34); L Group (n = 34)

The same comparison was applied to the L group. In comparing the scores of the

pretest on TWs of the familiar text to the scores of the immediate test, Table 4-5

showed that L group had significant vocabulary gain in the more familiar text, t(33) =

7.21, p < .01. And when comparing the scores of the pretest on TWs of the familiar text to the scores of the posttest, L group had significant vocabulary retention in the more familiar text, t(33) = 7.15, p < .01. In the unfamiliar text, in comparing the scores of the pretest on TWs to the scores of the immediate test, L group had

significant vocabulary gain in the less familiar text, t(33) = 6.64, p < .01. And when comparing the scores of the pretest on TWs to the scores of the posttest, L group had significant vocabulary retention in the less familiar text, t(33) = 5.75, p < .01. From the results in Table 4-5, there were significant vocabulary gain and retention in both texts across the H and L groups.

To conclude to results of Table 4-3 and 4-5, these results showed that both H &

L groups achieved higher vocabulary gain in the familiar text than in the less familiar text. For H group participants, they had higher gain in the more familiar text (M

HF= 3.97 > M

HU= 2.47; see Table 4-2). Also, for L group, they had better gain in the more familiar text than in the less familiar text (M

LF= 3.21 > M

LU= 1.74; see Table 4-2). In comparing the gain difference between the two texts for H group, Table 4-3 showed that the vocabulary gain difference across two texts reached significance, t(33) = 2.30, p < .05, which meant that H group had significantly higher vocabulary gain while

reading the more familiar text than the less familiar text. In comparing the retention difference between the two texts for H group, Table 4-3 showed that the retention difference across two texts reached significance, t(33) = 2.17, p < .05, which meant that H group had significantly higher retention two weeks after reading the more familiar text than the less familiar text. In comparing the gain difference between the two texts for L group, Table 4-3 showed that the gain difference across two texts reached significance, t(33) = 3.91, p < .01, which meant that L group had significantly higher vocabulary gain while reading the more familiar text than the less familiar text.

In comparing the retention difference between the two texts for L group, Table 4-3

showed that the retention difference across two texts reached significance, t(33) = 4.45, p < .01, which meant that L group had significantly higher retention two weeks after reading the more familiar text than the less familiar text.

In sum, the results of Paired–Samples t-tests revealed several findings:

1. For intermediate readers (H group), they had higher reading comprehension scores of the more familiar text (Mean = 38.24) than the less familiar text (Mean = 33.82), though the difference of reading comprehension scores across the two texts did not reach significance.

2. Intermediate readers achieved higher vocabulary gain (Mean = 3.97) and retention (Mean = 2.88) in the more familiar text than in the less familiar text (Mean of gain

= 2.47; Mean of retention = 1.74). There were significant vocabulary gain and retention for intermediate readers in both texts. And the scores of gain and

retention while reading the more familiar text were significantly higher than those in the unfamiliar text, which meant their gain and retention disparity reached significance.

3. For elementary readers (L group), they had higher reading comprehension scores of the more familiar text (Mean = 20.00) than the less familiar text (Mean = 16.76), though the difference of reading comprehension scores across the two texts did not reach significance.

4. Similarly, elementary readers also achieved higher vocabulary gain (Mean = 3.21)

and retention (Mean = 2.26) both in the more familiar text and in the less familiar

text (Mean of gain = 1.74; Mean of retention = 1.00). And there were significant

gain and retention for elementary readers in both texts. Noticeably, elementary

readers also had significant gain and retention in the less familiar text. And the

scores of gain and retention in the more familiar text were significantly higher

than those in the unfamiliar text, which meant their disparity reached significance.

In general, the results in Table 4-3 revealed that topic familiarity facilitate vocabulary gain while reading and retention after reading.

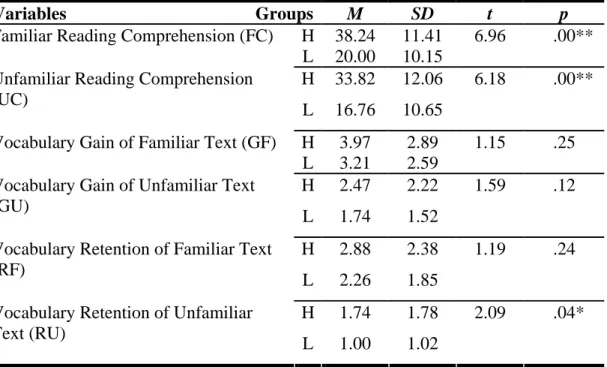

4.1.6. Independent-Samples t-tests on Reading Comprehension, Vocabulary Gain and Retention of Different Topic Familiarity across H and L Groups In order to determine the effect of the independent variable reading proficiency (H & L groups) on the dependent variable of reading comprehension, vocabulary gain and retention in the more and less familiar texts, an Independent-Samples t-test was conducted, testing the vocabulary gain and retention between H & L groups in texts of different topic familiarity.

The results revealed that across both two texts, H group achieved better reading comprehension than L group. Table 4-6 showed that H group achieved higher

comprehension than L group of both texts (M

HFC= 38.24 > M

LFC= 20.00; M

HUC= 33.82

> M

LUC= 16.76). Table 4-6 displayed that there was significant difference, t(66) = 6.96, p < .01, between the mean scores of comprehension between the two groups. These

results revealed that readers’ different reading proficiency level significantly affected reading comprehension while reading texts of different topic familiarity.

In addition, Table 4-6 showed that in both more familiar and less familiar texts, H group achieved higher vocabulary gain than L group. The vocabulary gain of H group in the familiar text is higher than that of L group (M

HGF= 3.97 > M

LGF= 3.21) though the gain difference showed no significance, t(66) = 1.15, p > .05. Next, the vocabulary gain of H group in the less familiar text is higher than that of L group (M

HGU= 2.47 > M

LGU= 1.74) though the gain difference showed no significance, t(66)

= 1.59, p > .05. The results revealed that readers’ different reading proficiency

affected vocabulary gain while reading both more and less familiar texts.

Similarly, Table 4-6 showed that in both more familiar and less familiar texts, H group achieved higher retention than L group. The retention of H group in the familiar text is higher than that of L group (M

HRF= 2.88 > M

LRF= 2.26) though the gain

difference showed no significance, t(66) = 1.19, p > .05; the retention of H group in the less familiar text is higher than that of L group in the less familiar text (M

HRU= 1.74 > M

LRU= 1.00) and noticeably the retention difference between H & L group in the less familiar text showed significance, t(66) = 2.09, p < .05.

Table 4-6 A Summary Table of Independent-Samples t-test: Reading

Comprehension, Vocabulary Gain and Retention between H and L Groups after Reading Familiar and Unfamiliar Texts

Variables Groups M SD t p H 38.24 11.41 6.96 .00**

Familiar Reading Comprehension (FC)

L 20.00 10.15

H 33.82 12.06 6.18 .00**

Unfamiliar Reading Comprehension (UC)

L 16.76 10.65

H 3.97 2.89 1.15 .25

Vocabulary Gain of Familiar Text (GF)

L 3.21 2.59

H 2.47 2.22 1.59 .12

Vocabulary Gain of Unfamiliar Text (GU)

L 1.74 1.52

H 2.88 2.38 1.19 .24

Vocabulary Retention of Familiar Text (RF)

L 2.26 1.85

H 1.74 1.78 2.09 .04*

Vocabulary Retention of Unfamiliar Text (RU)

L 1.00 1.02

Note. **p < .01, *p <.05.; n = 34 (H group); n =34 (L group)

In sum, these results showed that H group achieved higher vocabulary gain than L group in both texts, though the gain difference did not reach significance. Next, H group maintained higher retention than L group in both texts, and the retention difference reached significance while reading the less familiar text. The results

showed that readers’ different reading proficiency affected vocabulary retention while

reading more and less familiar texts. And while reading the unfamiliar text, the retention difference between H & L groups is higher than reading the more familiar text. The result revealed that L group participants performed significantly poorer in retention while reading the less familiar text. The finding corresponded with the findings of previous studies (Chern, 1993; Pulido, 2003) and also the researcher’s expected outcome.

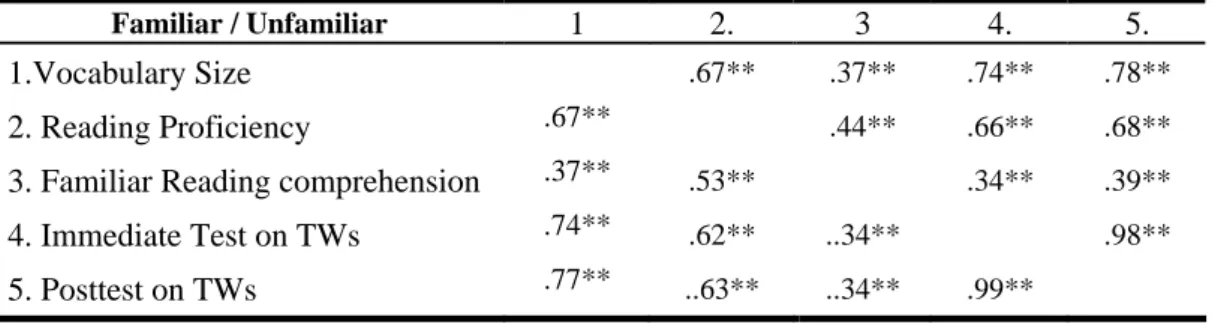

4.1.7. Pearson Correlations Analysis on Vocabulary Size, Reading Proficiency, Vocabulary Gain and Retention of Different Topic Familiarity

Table 4-7 presented the Pearson correlations among readers’ vocabulary size, English reading proficiency, reading comprehension, and the scores of immediate and retention VKS tests in the more familiar text. Firstly, there was moderate correlation (r=.44) between English reading proficiency and reading comprehension of the familiar text. This correlation showed that while reading familiar texts, as reading proficiency increases, so does the ability to comprehend the text. This result echoed the previous finding (Holmes,1983) of literature review that reading proficiency affects reading comprehension. Secondly, there was moderate correlation (r = .66) between reading proficiency and the scores of immediate VKS test on TWs in the familiar text. Next, there was moderate correlations (r = .68) between reading

proficiency and the scores of retention VKS test. The results revealed that as English reading proficiency increases, so does the ability to acquire and retain vocabulary in context while reading the familiar text. Furthermore, there was low correlation (r

=.34) between reading comprehension and the scores of immediate VKS test, and

between reading comprehension and the scores of retention VKS test (r = .39) on

TWs. This displayed that reading comprehension did correlate with vocabulary gain

and retention while reading familiar texts, though the correlation was low and there

may be other factors (e.g. reader’s vocabulary size) which affect the vocabulary gain and retention more.

Table 4-7 also presented the Pearson correlations among participants’ vocabulary size, English reading proficiency, reading comprehension, and the scores of

immediate and retention VKS test in the less familiar text. Firstly, there was moderate correlation (r=.53) between English reading proficiency and reading comprehension in the less familiar text. This correlation showed that even while reading less familiar texts, as reading proficiency increases, so does the ability to comprehend texts. The result also revealed the importance of reading proficiency in reading comprehension while reading less familiar texts. Secondly, there was also moderate significant correlation (r=.62) between reading proficiency and the scores of immediate and retention test (r = .63) on TWs in the less familiar text. And these correlations revealed that as English reading proficiency improves, so does the ability to acquire and retention vocabulary in context even while reading less familiar texts.

Furthermore, there was the low correlation (r=.34) between reading comprehension and the scores of immediate and retention (r = .34) VKS test on TWs. This displayed that reading comprehension did correlate vocabulary gain and retention while reading less familiar texts, as well as familiar texts, though the correlation was low.

The correlations between reading comprehension and vocabulary gain were low (r=.34) when participants read more and less familiar topics. The correlations revealed that whether participants’ topic familiarity slightly relate to their vocabulary gain. And because the reading comprehension score (Mean=31.06) of the more familiar topic is higher than that of the less familiar topic(Mean=24.71, see Table 4-1), it is reasonable that participants achieve higher vocabulary gain in the more familiar text (Mean=3.03) than in the less familiar text (Mean = 2.11, see Table 4-2).

But because the correlation between reading comprehension and vocabulary gain is

low (r = .34), it can be inferred that topic familiarity and reading comprehension cannot guarantee vocabulary gain. The correlations between vocabulary gain and other two variables, such as reading proficiency and vocabulary size, also showed their important correlations.

Table 4-7 Pearson Correlations of Vocabulary Size, Reading Proficiency, Reading Comprehension, Immediate VKS Score and Posttest VKS Score after Reading Both Texts

Familiar / Unfamiliar 1 2. 3 4. 5.

1.Vocabulary Size .67** .37** .74** .78**

2. Reading Proficiency .67** .44** .66** .68**

3. Familiar Reading comprehension .37** .53** .34** .39**

4. Immediate Test on TWs .74** .62** ..34** .98**

5. Posttest on TWs .77** ..63** ..34** .99**

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2 tailed).