Chapter Two Literature Review

This chapter is divided into three sections. The first section presents the

classification of conjunctive adverbials (2.1). The second section reviews corpora and language teaching, including the characteristics of a modern corpus (2.2.1), the types of corpora (2.2.2), and the convergence between language teaching and corpora (2.2.3). The third section reviews empirical research on the use of conjunctive

adverbials by native speakers of both Asian languages (2.3.1) and European languages (2.3.2).

2.1 Classification of Conjunctive Adverbials

Most grammarians and researchers have tried to classify the semantic meanings of conjunctive adverbials. Halliday and Hason (1976), for instance, classified the conjunctive type of cohesive devices into four semantic roles, namely, additive, adversative, causal and temporal. Quirk et al. (1985) distinguished seven conjunctive

roles: (a) listing (b) summative (c) appositional (d) resultive (e) inferential (f) contrastive (g) transitional. Biber et al. (1999) classified conjunctive adverbials into

six categories, namely, enumeration and addition, summation, apposition, result/inference, contrast/concession, and transition. Biber et al.’s (1999) list has

much in common with Quirk et al.’s (1985), except renaming Quirk et al.’s (1985) listing as enumeration and addition, and contrastive as contrast/concession and

combing resultive and inferential into result/inference.

A number of empirical studies, such as Altenberg and Tsang (1998) and Tankó (2004), are based on Quirk et al.’s classification scheme to examine learners’

discourse-functional use of conjunctive adverbials. Lee (2004), however, adopted Biber et al.’s (1999) semantic role classification to study Korean natives’ use of conjunctive adverbials in English writing. In order for the present study to be

reduplicable, we decided to adopt Biber et al.’s scheme since their corpus-based approaches to language investigation were similar to our study.

Biber et al.’s semantic classification scheme will be later modified to suit the needs of our research. We will divide their first category, enumeration and addition, into two separate categories because the enumeratives and additives have different functions in discourse. We will also add other two categories, Corroboration and Others. The Corroboration category will be added because the corroborative type of

adverbials, such as of course and in fact, are commonly used in academic writing to emphasize a new point or give a new turn to the argument (Altenberg & Tapper, 1998;

Granger & Tyson,1996; Tankó, 2004). Finally, Others, will be added because the two conjunctive adverbials, on the one hand and on the other hand can be placed under more than one category. They can be either contrastive and additive or enumerative.

This multi-functionality may cause discrepancy between native speakers and learners, so they were singled out in the Others category. In total, nine semantic roles will be identified in our semantic classification scheme. They are: (1) Enumeration (2) Addition (3) Summation (4) Apposition (5) Result/Inference (6) Contrast/Concession (7) Transition (8) Corroboration (9) Others. An account of each of the semantic roles is outlined below (Quirk et al., 1987; Biber et al., 1999).

(1) Enumeratives not only assign numerical labels but also connote relative priority to the items listed. They endow the list with an integral structure, having a beginning and an end. This type of conjunctive adverbials include ordinal numbers, such as first and second, and adverbs such as finally and lastly, as well as other structures such as

prepositional phrases. Usually the order of enumeration follows real-life or time sequence orders but this is not always so.

(2) Additives mark the next unit of discourse as being added to the previous one.

Similar to enumeration, it endows the list with an integral structure, having a

beginning and an end. Additive conjunctive adverbials can be divided into two subtypes, equative and reinforcing, depending on the force they can add to a

preceding item. Equatives, such as similarly, indicate an item has a similar force to a preceding one; the reinforcing additives, such as furthermore, assess an item as adding greater weight to a preceding one.

(3) Summatives, like in sum, introduce an item that embraces the preceding texts and they are intended to conclude or sum up the information in the preceding discourse.

(4) Adverbials marking apposition, in other words, for example are concerned with the expression of the preceding text in other terms. The part following the adverbial is treated either as an example, which presents information that is in some sense

included in the previous text, or as an equivalent of the preceding text.

(5) Resultives/inferentials mark the second part of the discourse as the result or consequence of the preceding discourse.

(6) The contrast adverbials in the contrast/concession category are used to show

incompatibility between information in different units of discourse to denote contrasts, alternatives or differences and the concessive adverbials signal concessive

relationships, indicating the subsequent discourse expresses some reservation about the idea in the preceding one. The conjunctive adverbial, besides, have both additive (Halliday & Hason, 1976) and contrastive (Biber et al., 1999; Quirk et al., 1985) functions. In this research, we focus on its contrastive function and place it in this category.

(7) Adverbials in the transition category, such as now, serve to shift attention to another topic that does not follow directly from the preceding event. The subsequent discourse may not be incompatible with its preceding content but can be loosely connected or unconnected.

(8) Adverbials in the corroboration category, such as of course and in fact, are often

referred to as disjuncts in the grammar. They were included for they serve clear cohesive links to express attitudes and strengthens the argument as emphasizers.

(9) Others (on the one hand, on the other hand) in this research serve more than one semantic function. They can be used to list items similar to enumeratives and also to mark contrast in different discourse units, similar to the contrastives/concessives.

2.2 Corpora and Language Teaching

The word ‘corpus’ has its root in the Latin word, ‘corpus,’ which means ‘body’,

‘body of a person’ or ‘collection of facts or things’ (Harper, 2001; McEnery & Wilson,

1996). In linguistics and lexicography, ‘corpus’ is often defined as “a collection of linguistic data, either written texts or a transcription of recorded speech, which can be used as a starting point of linguistic description or as a means of verifying hypotheses about a language (Cyrstal, 2000, p.95).” Such a definition on corpus will probably make a number of language teachers feel that ‘corpora’ are remote from their lives. In fact, every language teacher possesses at least one corpus though they are likely to be unaware of it. Imagine a pile of students’ written assignments or a stack of audio cassettes that recorded learners’ speech mounting on your desk. These language productions are in reality a kind of a corpus and from the language productions language teachers can locate and list particular problems learners have. This example demonstrates that language corpora are not beyond reach from language teachers.

Rather, corpora are closely related to language instructors and a better understanding of the constituents of a corpus and how to make the most out of this tool to enhance language teaching is essential to every language teacher.

2.2.1 Characteristics of a Modern Corpus

Although there are a few corpora available in book forms or in other forms of

media such as video recordings (the ELISA2 corpus, a video-based interview with native speakers, for example), most modern corpora are in ‘machine-readable’

(McEnery & Wilson, 1996, p.197) format. A machine-readable corpus can free the mind of researchers, including all those involved in the search of language data (such as language teachers). Once they key in a search word or phrases, the machine will automatically or semi-automatically do the search work to locate the specific language phenomenon the researchers request and allow them to concentrate on the analysis of intended language patterns. A machine-readable corpus not only can be searched and manipulated at speed. It can also be easily enriched with extra information such as annotations.

A modern corpus, if it is to be of substantial meanings to users, either to

researchers (including teachers) or readers, should be of substantial size and the data it collects should be less-biased. Such a corpus will be representative of the language or the varieties of the language it represents and will help to validate the generalizability of the corpus findings. In other words, the corpus findings will not be limited to a sheer reflection of the language phenomenon produced by a specific group of learners or in specific geographical and social contexts.

2.2.2 Types of Corpora

Corpora come in many shapes and sizes, because they are built to serve different purposes. There are two philosophies behind corpus design, leading to the distinction between reference and monitor corpora. Reference corpora imply bodies of texts of finite size; that is, the number of words they contain are determined, usually at the beginning of a corpus-building project. Monitor corpora, on the other hand, are expandable. In other words, language data are added constantly to the corpus and its

2 ELISA (English Language Interview Corpus as a Second-Language Application): see at http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/elisa/html/elisa_index.html

size is on a constant increase annually, monthly or even daily (Gabrielatos, 2005;

Hunston, 2002; McEnery & Wilson, 1996)

In terms of content, corpora can be either general, that is, aiming to reflect a specific language or a specific variety of language in all its contexts of use, or specialized, that is, attempting to be representative of the particular type of language

in specific contexts. Corpora may also contain language produced by native or non-native speakers (usually learners, e.g. the International Corpus of Learner

English). Finally, corpora can be monolingual, containing texts of a single language, or multilingual. Multilingual corpora are of two types: they can contain the same text types in different languages, or they can contain texts translated into different

languages and this type of corpora is also known as parallel corpus, e.g. COMPARA, a Portuguese-English translation corpus and TOTALrecall, a Chinese-English

translation corpus constructed under the CANDLE project3 (Gabrielatos, 2005;

Hunston, 2002; Kennedy, 1998; McEnery & Wilson, 1996; Meyer, 2002).

2.2.3 Corpora and Language Pedagogy: A Convergence

Corpus linguistics is a linguistic methodology, which aims to base accounts of language on corpora, as opposed to examples obtained by introspection, by judgments of grammarians or by haphazard observations (Matthews, 1997). The corpus-based approach to linguistics and language education has gained prominence since the mid-1980’s. Leech (1997) observed that a convergence between language teaching and corpora was apparent and the convergence had three focuses: the direct use of corpora in language teaching (i.e. teaching corpus as an academic subject, teaching learners methods to exploit corpora, and using corpus-based approaches to teaching

3 For reference of the CANDLE project see at http://candle.cs.nthu.edu.tw/candle/

For TOTALrecall translation corpus see at:

http://candle.cs.nthu.edu.tw/totalRecall/totalRecall/totalRecall.aspx

language and linguistics courses), the indirect use of corpora in teaching (syllabus design, reference publishing and language testing), and further teaching-oriented corpus development (i.e. LSP corpora, L1 developmental corpora and L2 learner corpora).

McEnery & Gabrielatos (2005), in the study of the interconnection between corpora and language teaching, suggested that from a pedagogical perspective corpora can be classified into three types: native speaker corpora, learner corpora and corpora of coursebooks. In the following, these three types of corpora will be explicated and the native speaker corpora will be examined first.

L1 corpus-based linguistic research has provided evidence of discrepancies between actual language use and traditional introspection-based views on language (Sinclair, 1997, p.32-34). Corpus-based research has also revealed the inadequacy of many of the rules that still dominate ELT materials.

As early as the sixties, George (1963, cited in Kennedy 1998, p.283), for example, studied a corpus of English made in Hyderabad that was based on written texts and found that the highest frequency of occurrence of the simple present is not to indicate habitual or iterative actions, such as ‘I go to school by bus every day.’ (5%), but rather the actual present, such as ‘ I agree with you.’ (57.7%) or neutral time, such as ‘My name is Mary.’ (33.5%). His findings converge with a more recent grammar of English complied by Mindt (2000) based on corpora totaling 240 million words of spoken and written English. Mindt found that the three prototypes which make up the majority of all cases of the present forms of verbs are the extended present, the actual present and the timeless present. This is contrary to the emphasis given to the habitual present in most ESL and EFL textbooks as the major function of the simple present.

The analysis of native speaker language enables a more accurate language description, which feeds into the development of pedagogical materials and curricula

and the compilation of dictionaries and grammar references (Hunston & Francis, 1998, 1999; Kennedy, 1992; Meyer, 1991; Owen, 1993). Insights derived from native

speaker corpora can also contribute to the construction and evaluation of language tests.

In addition to the L1 corpus, a learner corpus can make a substantial contribution to language instruction. Using language corpora allows teachers to be much more precise in examining learner performance and identifying needs rather than just forming an overall impression because corpus use enables teachers to examine particular areas in detail and to spot specific errors.

Linguistic exploration of learner corpora usually involves one of the two methodological approaches: contrastive interlanguage analysis and computer-aided analysis (Granger, 1998; Granger, 2002; Lee, 2004).

Contrastive interlanguage analysis (CIA) involves two types of comparison:

Native speakers (NS) vs. Non-native speakers (NNS) and Non-native speakers (NNS) vs. Non-native speakers (NNS). NS/NNS comparisons can throw light on non-native characteristics through a detailed quantitative and qualitative comparison of linguistic features in native and non-native corpora. The results of the comparisons are not necessarily restricted to an indication of learner errors but a realization of

non-nativeness, showing instances of overrepresentation and underrepresentation of learner usage. On the other hand, NNS/NNS comparisons can strengthen researchers’

knowledge on interlanguage. By comparing learners of different L1 backgrounds, in particular, researchers can clarify whether learners’ linguistic features are

developmental or peculiar to one group and possibly L1 induced.

Various linguistic features, such as adjective intensification (Lornez, 1998), modal and reporting verbs (Neff, Dafouz, Herrera, Martínez, Rica, Díez, Prieto

& Sancho, 2003), multiword units (De Cock, 1998), conjunctions (Leung, 2005),

adverbial markers and tone (Hinkel, 2003), marked themes (Green, Christopher, Lam,

& Mei, 2000), progressive (Axelsson & Hahn, 2001), cleft and information structure (Aronsson, 2003) and conjunctions (Carrie, 2005), were investigated in this line of CIA research. Carrie (2005), for example, is an instance of NS vs. NNS comparison.

Carrie (2005) investigated Hong Kong university students’ use of English

conjunctions (coordinate conjunctions) and connectives (conjunctive adverbials we refer to in this research), and focused on three conjunctions, and, or and but,

comparing their frequencies in functions and positions with native speakers’ use. The result indicated that Chinese EFL learners in general used fewer conjunctions and more connectives in comparison with native speakers while both native and

non-native speakers tended to place conjunctions in clause-initial positions. Chinese EFL learners displayed to a large extent a good understanding in the usage of major conjunctions. Nevertheless, some differences and grammatical mistakes can still be found. The deviant use of conjunctions, in Carrie’s view, are attributable to factors such as syntactic transfer from L1 to L2, the shortcomings of instruction learners received at school as well as learners’ carelessness in drafting and writing.

In addition to the CIA approach, the computer-aided analysis is also employed in the linguistic exploration of learner corpora. This approach is further divided into two sub-methods in the manipulation of learner errors. The first is to select an error-prone linguistic item and use concordancing software tools to retrieve all instances of the linguistic item from the corpus. Then the instances retrieved are examined manually or semi-manually for any misuse. The second method consists in devising a

standardized system of error tags and tagging all the errors in a learner corpus

(Granger, 1998; Granger, 2002). Once a learner corpus is finished with error-tagging, researchers devise studies on various aspects of the characteristics of learner language and retrieve relevant data from the fully error-tagged corpus.

In Taiwan, researchers tend to adopt the computer-aided approach to examine linguistic features, such as If-conditionals (Ke, 2004), Verb-Noun collocations (Liu, 2002), Be-omission (Lin, 2002), subordinators (Chang, 2003), and Bare-singular errors (Kao, 2003). Liu (2002), for instance, extracted learner data from the

EnglishTLC ( English Taiwan Learner Corpus) to investigate Taiwanese learners’ V-N miscollocations. She searched for the error tags provided by different writing

instructors as written feedback to their students in the integrated IWill online writing platform, and adopted a bootstrapping strategy to uncover 233 instances of V-N miscollocations from the corpus. By observing learners’ miscollocations, Liu discovered a tendency pattern, suggesting that learners’ V-N miscollations were not arbitrary. She also claimed that “the probability of learners misusing a verb collocate over a noun collocate is 93% (217 out of 231 cases), and the percentage of verb miscollocates where the wrong verb happens to be either a synonym, hypernym or hyponym of the correct verb collocate is 56% (131 out of 233).” She concluded that learners’ L1 played a significant role in their decision of lexical choice.

The two methodological approaches in learner corpus linguistics highlight the different functions between native speaker and learner corpora. Learner corpora have greater potentials in Second/Foreign Language pedagogy while native speaker corpora in recent years have been widely used in language material design, esp. in English Language Teaching (ELT), to describe what linguistic features are typical in the target language. It empowers researchers to investigate what is difficult for learners in general and for specific groups of learners, which had been a challenging task in the field of SLA research for the absence of learner output but now is realized with the computer-aided learner corpus.

The analysis of learner language sheds light on learner language phenomenon and traces whether a language use is consistent among learners of various

backgrounds, i.e., a developmental pattern, or existent among particular groups of learners, such as Chinese learners of English. Insights derived from learner corpora can also facilitate the development of ‘more efficient language learning tasks, syllabuses, and curricula’ (Granger et al., 2002, p.6).

Finally, corpora of coursebooks represent the collection of the language teaching coursebooks learners use in classroom settings. The corpora enables the examination of the language to which learners are exposed and the results can be compared to L1 corpora. Insights derived from the comparison can be used to improve pedagogical materials.

2.3 Empirical Research on Conjunctive Adverbials

In this section, research on EFL/ESL language learners’ use of conjunctive adverbials will be reviewed. The research all share the feature that they only investigate learners of monolinguistic backgrounds. In other words, subjects in a single research are homogenous and speak the same native language. Most of the research has centered on native speakers of Asian and European languages.4 In our review we will cover major research targeting at these two groups (i.e. Asians and Europeans), who are learning English as a second/foreign language in their domestic countries. Research aiming at learners in the same geographical region, Asia or Europe, are inter-related. If we chronologicalize the studies on Asian language backgrounds, we find the methodologies of later research are mostly the revisions of earlier ones. The European studies are done more recently, completed less than ten years from now. Three out of the four studies to be interviewed adopt a standardized

4 Here we adopted the categorization of languages of the world proposed by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). MIT based on geographical zones classified world languages into six categories:

African, Asian, Austro-Pacific, North-American, South-American, European. For further information about the categorizations of world languages, see at http://zh.wikipedia.org (an online encyclopedia resource:Wikipedia)

methodological approach to the construction of learner corpora and they all extracted English native data from the same pool of native speakers. Results of the European studies, therefore, are worth comparison and a cross linguistic comparison can shed light on whether learners’ particular language phenomenon is language specific or general disregarding learners’ language backgrounds.

Due to the interrelatedness among Asian researches and the relationship among European researches, we decide to classify our review on empirical research into two categories: Asian speakers’ us and European speakers’ use of conjunctive adverbials.

In the following, we will begin our review on studies of Asian language speakers.

2.3.1 Asian Language Speakers’ Use of Conjunctive Adverbials

As early as 1990, researchers, such as Crewe (1990), Field and Yip (1992), and Milton and Tsang (1993), had initiated discussion on Asian learners’ use of

conjunctive adverbials. Most studies examined students from Hong Kong, but Hung (2003) studied Taiwanese senior high and Lee’s (2004) subjects are Korean college students.

Crewe (1990) was one of the earlier researchers starting a discussion on the use of conjunctive adverbials. He used the term logical connectives in his report and classified logical connectives, based on Halliday and Hason’s (1976) conjunction classification scheme, into four semantic categories, namely, additives, adversatives, causals and temporals. Crewe’s (1990) discussion could not be treated as an empirical

study but only an account of his observation on Hong Kong ESL undergraduates’

writing. He found that learners had a tendency to overuse connectives and that they misused on the contrary for however and on the other hand. He attributed learners’

overuse and misuse problems to two possible sources. The misuse problem, in his view, was due to the inadequate advice and exercises in English textbooks and grammar books for they treated connectives indiscriminately. They merely classified

connectives into broad semantic functions and leave learners the impression that an alternate use of one connective under the same semantic categorization will add stylistic variation. The overuse problem, for another, resulted from failure of the English instruction as learners in general have the impression that the more connectives they use in their writing, the better the writing will be. And therefore learners tend to disguise their poor writing by adding more connectives.

Following Crewe (1990), Field and Yip (1992), also based on Halliday and Hasan’s (1976) cohesion theory, investigated the internal conjunctive cohesive devices (ICCD) (that is, the conjunctive adverbials for this present research) and the positioning of ICCD in the English argumentative essays written by three groups of Cantonese high school students and one native speaker group from a high school in Sydney.

Each instance of ICCD in every script was manually highlighted and recorded and a t-test on the number of ICCDs by each writer was performed. The results suggested that L2 writers tended to use more devices than L1 writers and the

difference between the L1 and L2 groups was significant. Overall, L2 writers used a wider range of devices. They also relied more on initial paragraph/sentence position devices, in contrast with L1 writers’ preference for non-initial position devices.

Field and Yip further noted learners’ particular problems in the use of the connectors on the other hand, actually, moreover and besides. They stated that learners’ use of on the other hand to add a point without meaning to imply contrast was a first language transfer feature. The overuse of actually can be traced back to the classroom language of their English native teachers. Learners’ overuse of also and moreover is explained to be the by-product of textbook influence because there was a high count of the two devices in the textbook’s model answers.

Compared with previous research, Field and Yip (1992) provided statistical

evidence to show differences in the number and the type of ICCDs between English natives and non-English natives. However, it has its limitations. First, the data of learners and English natives are still small in size and can hardly claim

generalizability. Also, as Field and Yip manually recorded writers’ use of cohesive devices, the cohesive devices identified were not presented in their research and therefore we could not make any comparison between groups of writers in the types of conjunctive adverbial they employed.

Milton and Tsang (1993), distinct from previous smaller scale research on Hong Kong students’ use of conjunctive adverbials, attempted to investigate quantitatively the conjunctive adverbials (termed ‘logical connectives’ in their research) in the English writing of Chinese undergraduates and English native speakers. They drew on a 4,084,000 word learner corpus to compare with three existing large-scale corpora, namely the American Brown Corpus, British LOB corpus, and HKUST corpus. 25 logical connectives were examined and classified adopting the classification scheme in Celece-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman’s Grammar Book (1999, p.323-334).

Despite the discrepancies in the frequency ranking of several logical connectors in the three NS corpora, Milton and Tsang claimed that half the connectors appeared significantly more frequently in the learner corpus. They attributed learners’ erroneous use of moreover and therefore to redundant use and misuse respectively. The

redundant additive use, as Milton and Tsang explained, may be the result of learners’

uncertainty to connect ideas, and the causal misuse is learners’ difficulties in distinguishing facts and opinions. Again, like prior researchers, Milton and Tsang attributed the origin of learners’ deviant use to the out-of-context grammar instruction and the pitfall in the presentation of connective meanings under broad functional classification.

In contrast to earlier researches, Milton and Tsang’s (1993) enlargement of

learner corpus and a focused examination on a limited number of logical connectors enhanced the overall quality of the quantitative result and offered readers a better picture of the total number of each connector use. This investigation in its scope, however, is restricted in two perspectives: for one, as they have mentioned in the research design, none of the NS corpora is comparable to their learner data in terms of genre or circumstance. This decreases the efficiency in the process of comparison and the result obtained is less convincing than one evaluated with a comparable corpus. In addition, Milton and Tsang (1993) did not explain the ground in their selection of the connectives for study, simply stating that “we selected 25 single-word logical

connectors for concordancing (p.223).”

Bolton et al. (2002) re-examined the methodological issue of corpus sizes and the standardization of cross-corpora comparison and modeled a new research to investigate Hong Kong students’ connector/connective (i.e. conjunctive adverbial) use in writing. Both the learner and native speaker data were from the same corpus, the International Corpus of English (ICE). The learner data with a total of 2,755 sentences (46,460 words) were from the ICE Hong Kong component and the English native data were extracted from the ICE British component, consisting of 2471 sentences and 42,587 words.

Bolton et al. (2002) clearly defined academic writings as those already published in international English-language academic journals and generated a list of common academically-used connectors from a sample of academic writing. The top 54 frequently occurring connectives were used as a benchmark in the analysis of Hong Kong and British students’ writing and the ‘sentence’ instead of ‘word’ was used as the basic unit of analysis in calculating the ‘ratio of occurrence’ of connectors.

The result showed no evidence of significant underuse, but both groups of students overused a wide range of connectors. It was concluded that the overuse of

connectives was not confined to non-native speakers and that both non-native and native students use a considerably smaller number of connector types in their writing than professional academics.

Bolton et al’s (2002) study contributed much to the study of conjunctive adverbials in two perspectives. First, it shed light on the constituents of academic conjunctive adverbials and the top 54 occurring academic connectives can function as a reference list in the instruction or learning of English academic writing. In addition, Bolton et al.’s (2002) study highlighted the fact that the problem of inadequate selection of connectives is not limited to L2. In fact, both L1 and L2 learners’

insufficient knowledge about a particular genre can lead to the same problem. Bolton et al’s (2002) investigation, however, is not left without criticism as it is purely quantitative in character. If combined with a qualitative examination, it could bring insights on L1 and L2 learners’ differences in the selection of connectives and possible causes for the different selection.

The researches stated above are targeted at EFL learners in Hong Kong. In contrast, Hung (2003) examined Taiwanese senior high school students’ use of conjunctions (i.e. intersentential cohesive devices, namely conjunctive adverbials) in writing. Unlike previous investigation, Hung (2003) had a qualitative examination, narrowing her study to four English connectives, i.e., besides ,however, on the contrary, and on the other hand. She assumed that Chinese learners are likely to use

the four English connectives erroneously provided that their equivalent Chinese translations bear different semantic meanings. 192 compositions written by 96 senior high school students were collected and the misuse of the four conjunctive adverbials were spotted. In addition, a questionnaire with 15 fill-in-the blank conjunction

questions was distributed to the same pool of subjects to further examine learners’

performance in using the four conjunctions.

The result confirmed Hung’s assumption that the four English conjunctions could create difficulties for Taiwanese learners because their equivalent Chinese translations carry different semantic meanings. Learners’ unawareness of the semantic differences would entail risks of misuse.

Hung’s (2003) investigation differed from the researches mentioned earlier in that it targeted at Taiwanese learners of English. Its methodological approach is of value to our present research as it described data in a qualitative manner, which intended to uncover sources of learners’ misuse. Hung successfully unveiled how the learners’ first language can cause interference in the acquisition of the four English conjunctive adverbials. Her study, however, still leaves space for further investigation.

Future studies, for instance, can set their subjects at different ages or language proficiency groups and also increase the number of conjunctive adverbials or the amount of data for examination.

Finally, the most recent research on conjunctive adverbials was completed by Lee (2004) and she adopted a corpus-based approach to investigate the use of conjunctive adverbials by Korean college students. Lee (2004), with reference to earlier research, devised a list of conjunctive adverbials and classified them into seven discourse-functional categories based on Quirk et al.’s classification scheme. A

214,363-word learner corpus was compiled and then compared to 150 English natives’ essays (192,190 words), extracted from Brown 1 corpus, a subcomponent of the Brown corpus.

The overall frequency result demonstrated that Korean learners significantly overused conjunctive adverbials. They also used fewer types of conjunctive adverbials. In terms of discourse functions, Korean learners manifested a higher frequency in use of all types of conjunctive adverbials except for the summative and transitional markers. The analysis of individual conjunctive adverbials revealed both

overuse and underuse in Korean learner corpus. Lee explained that the phenomenon might be due to learners’ insensitivity to registers by mixing formal written

conjunctive adverbials (e.g. moreover) with informal ones (e.g. so)

The syntactic position analysis indicated that Korean learners had an evident tendency for the preference of sentence initial adverbials in all seven categories while in contrast native speakers showed a tendency to employ the conjunctive adverbials in the non-initial position except for enumeration and summation categories.

Lee’s (2004) study has its strength and weakness. Lee’s (2004)

semantic-functional classification of all the occurrences of conjunctive adverbials in the learner data shed light on how student writers arrange ideas functionally with conjunctive adverbials and what semantic functions are the foci in their information arrangement. The way a writer arranges a discourse is rooted in his understanding of a specific genre. Lornez (1990), for instance, has mentioned that the use of causal links is a feature in English argumentative writing because the cause-effect relationship is important to organize arguments in English. With an understanding of how learners apply conjunctive adverbials to express functional relations, we will see differences in ways how the natives and non-natives treat the same genre. And this is what Lee (2004) did in the study and she stated that Korean learners employed conjunctive adverbials in order “to list, contrast, and emphasize a point rather than change the direction of the argument or summarize a point.”

On the other hand, the limit of Lee’s (2004) research lies in the sheer quantitative analysis. Although a quantitative study like this one can claim a good generalizability, we may be obliged to sacrifice its pedagogical value for the lack of knowledge about the underlying meanings of statistical figures. It is particularly true that an analysis of the use of conjunctive adverbials is based on a list to extract adverbials. We may lose sight of the adverbials not on the list or other syntactic realizations of connectors.

Only a combination of qualitative examination can make up the loss and this proposal should be taken into account for further research.

From our review of Asian research on conjunctive adverbials, we realize that studies have been targeting at Chinese learners, particularly Hong Kong

undergraduates. However, little is known about learners in Taiwan at different levels of proficiencies.

These Asian studies also indicated a pattern of development improvement on the issue of methodological designs. The data under investigation was originally limited to a number of written work (see, for example, Crewe, 1990) and gradually expanded to include more than ten thousand words (such as Bolton et al., 2002). Moreover, the comparability between the native and non-native data was improving and finally moved on to compare corpora based on similar standardization criteria (see, for example, Bolton et al., 2002).

Though later Asian research has attempted to reexamine previous

methodological issues, there is still room for improvement. These corpus-based studies have informed us the similarities and discrepancies between the use of

conjunctive adverbials by native speakers and non-native speakers. However, what is rooted in the differences has not been fully accounted for and this leads to an

impending need of a combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis. The quantitative analysis increases the generalizability of a study and the qualitative analysis helps uncover the underlying causes that result in the differences.

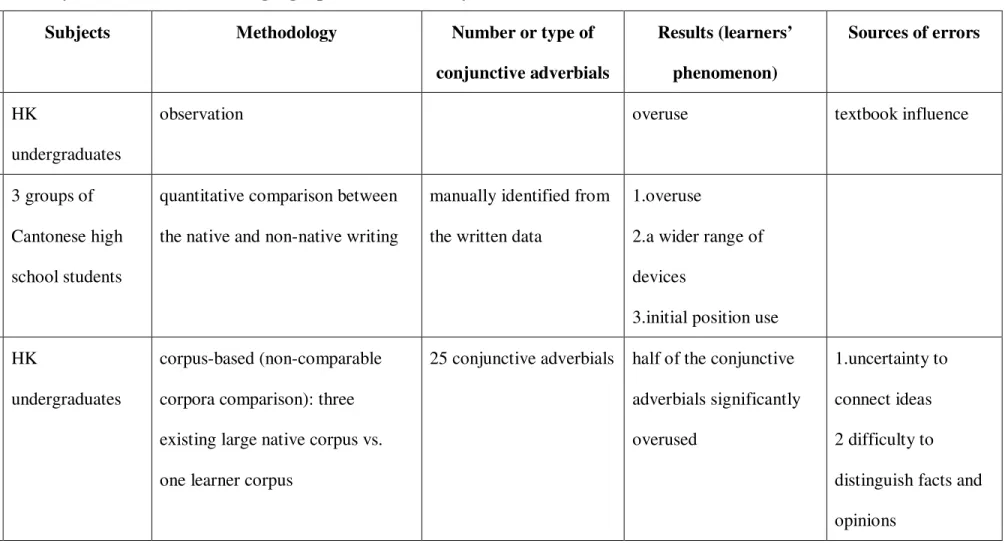

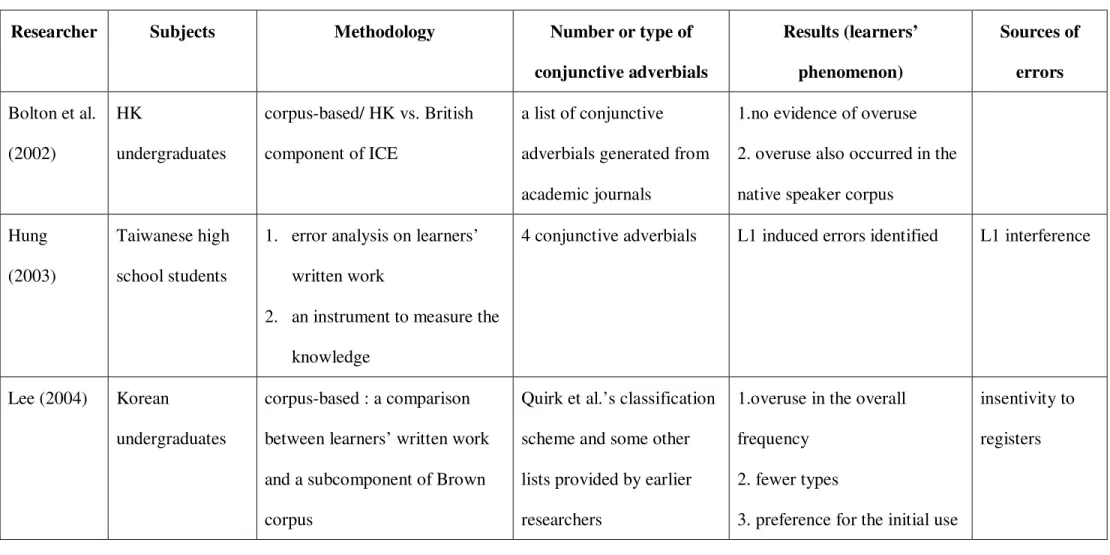

Findings of the research on Asian language speakers’ use of conjunctive adverbials are summarized in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Summary of research on Asian language speakers’ use of conjunctive adverbials

Researcher Subjects Methodology Number or type of

conjunctive adverbials

Results (learners’

phenomenon)

Sources of errors

Crewe (1990)

HK

undergraduates

observation overuse textbook influence

Field & Yip (1992)

3 groups of Cantonese high school students

quantitative comparison between the native and non-native writing

manually identified from the written data

1.overuse

2.a wider range of devices

3.initial position use Milton &

Tsang (1993)

HK

undergraduates

corpus-based (non-comparable corpora comparison): three existing large native corpus vs.

one learner corpus

25 conjunctive adverbials half of the conjunctive adverbials significantly overused

1.uncertainty to connect ideas 2 difficulty to distinguish facts and opinions

Table 2.1 continued

Researcher Subjects Methodology Number or type of

conjunctive adverbials

Results (learners’

phenomenon)

Sources of errors Bolton et al.

(2002)

HK

undergraduates

corpus-based/ HK vs. British component of ICE

a list of conjunctive adverbials generated from academic journals

1.no evidence of overuse 2. overuse also occurred in the native speaker corpus

Hung (2003)

Taiwanese high school students

1. error analysis on learners’

written work

2. an instrument to measure the knowledge

4 conjunctive adverbials L1 induced errors identified L1 interference

Lee (2004) Korean

undergraduates

corpus-based : a comparison between learners’ written work and a subcomponent of Brown corpus

Quirk et al.’s classification scheme and some other lists provided by earlier researchers

1.overuse in the overall frequency

2. fewer types

3. preference for the initial use

insentivity to registers

2.3.2 European Language Speakers’ Use of Conjunctive Adverbials

In this section, four empirical researches on European language speakers’ use of conjunctive adverbials will be reviewed: Lornez (1999), Granger and Tyson (1996), Altenberg and Tapper (1998), and Tankó (2004).

Lorenz (1999) made a quasi-development comparison of causal connective uses in argumentative essays by German learners of English and English natives. The contrastive corpora comprised one sample of 142, 131-word Juvenile German learners’ writing, one sample of 71, 881-word German undergraduates’ writing, one sample of 106, 730-word Juvenile British writers’ writing, and one sample of 94, 962-word British undergraduates’ writing. Causal links studied consisted of causal conjunctions, causal adverbs (that is, causal conjunctive adverbials), causal

prepositions, lexical causal patterns and nominal realization of causal relations.

The result showed that the use of causal links by native speakers indicated an increasing text-type differentiation, viz. a graduation toward a formal style of writing by applying links that tend to occur in formal register, for example, the causal adverbs therefore and hence. Learners’ use of causal links, on the other hand, did not show a

consistent gain as they grew in age and had more exposure to the target language.

German learners, moving from juvenile to undergraduate level, seemed to have an increase in the use of some types of causal links, which is parallel to the phenomenon in native speakers; however, with a closer look at learners’ individual link usage, a number of non-native patterns revealed. German learners exhibited a preference to place either some grammaticalized causal links (e.g. so and because) or lexicalized causal items (e.g. one reason is…) in initial position, especially sentence-initial position, or in theme position. Moreover, the frequency of these causal links revealed an increase with age when the two German learner groups were compared.

Learners’ overuse of some causal links also demonstrated their difficulties in the

control of registers and lexical semantic prosodies. They mixed the spoken register with formal written register and overextend words’ semantic meanings.

Granger and Tyson (1996) drew on subcomponents of the International Corpus of Learner English (ICLE) to investigate the use of connectors (i.e. conjunctive adverbials) by advanced French learners of English and to test the hypothesis that French learners would overuse connectors. The choice of connectors for the study was based on Quirk et al.’s (1985) list of connectors, excluding temporal connectors and adding certain attitudinal disjuncts and some emphasizers.

The result showed that the overuse hypothesis was invalid. Learners both overused and underused some connectors. The overused connectors were corroborative connectors (indeed, of course, in fact), appositive connectors (for instance, namely) and one additive connector (moreover). On the other hand,

connectors underused were the resultive type (therefore, thus, then). Learners’ overuse and misuse problems, except for the appositives, were L1 induced. Learners had preference for the initial position of connectors and this phenomenon was not language specific. Finally, Granger and Tyson (1996) claimed that learners mixed formal and informal registers in writing and it was the result of style insensitivity, which was due to the falsity of language instruction and EFL materials.

Altenberg and Tapper (1998) examined the use of adverbial connectors (that is, conjunctive adverbials) in advanced Swedish learners’ written English (extracted from the Swedish component of the International Corpus of Learner English) and compared it with the use in comparable types of native Swedish and native English writing.

They also compared the Swedish learner’s usage with that of advanced French learners of English in Granger and Tyson (1996).

The result showed that Swedish learners had an overall tendency to use fewer adverbial connectors in writing than both the native English students and Swedish

natives in their native language writing. Swedish learners also significantly underused resultive and contrastive adverbial connectors. They preferred to place connectives in sentence/clause initial position and such a preference was even stronger than the English students. Altenberg and Tapper (1998) stated that these deviations from the English native norm were not signs of L1 transfer and instead they may be due to the task in which learners had to express themselves in a foreign language.

Altenberg and Tapper (1998) also compared their study with Granger and Tyson’s (1996) study on French learners. The comparative results indicated that the Swedish learners underused adverbial connectors to a much larger extent than the French learners. Altenberg and Tapper cautiously stated that it might be connected with differences in the educational background of the two learner groups. Moreover, the result revealed a surprising similarity on the overuse and underuse of connectives.

They ruled out L1-induced transfer as an explanation for the over-/underuse of most of these adverbial connectors. Both groups of students underused resultive and contrastive connectors.

Finally, Tankó (2004) studied the use of adverbial connectors (that is,

conjunctive adverbials) in argumentative essays by Hungarian advanced learners of English (English major undergraduates). The result indicated that Hungarian students used slightly fewer adverbial connectors than the native writers. The most common type of semantic relationships expressed by the Hungarians is the listing function, followed by the resultive and contrastive functions. Hungarian students have a

tendency to arrange a highly structured contrastive set of ideas cumulatively and then emphasize a conclusion. Such a tendency is in contrast to that of English natives who tend to emphasize the cause-effect relations with the overt use of significantly more resultive connecting items. The results also showed that learners had an adequate awareness of the positions of adverbial connectors and they were aware of the register

characteristics of those adverbial connectors as their use of adverbial connectors in majority were formal.

From the review of the European studies on the use of conjunctive adverbials, two aspects of insightful information can be derived from their methodological

designs and the information should be taken into consideration in our research design.

The first is on the selection of data for investigation. Both the learner and native data in these studies were not only large in quantity but also comparable in terms of genre (mostly argumentative) and participant’s backgrounds (for example, native and non-native speakers were undergraduates). The other issue is the incorporation of a semantic classification scheme in the analysis of the types of conjunctive adverbials.

That is, three out of the four analyses adopted the same semantic scheme in Quirk et al.’s (1985) A Comprehensive Grammar of English. A semantic classification scheme like that enables us to look into how writers use conjunctive adverbials to mark semantic relations in discourse in addition to an overall frequency analysis.

Meanwhile, Lornez’s (1999) study on the use of causal links by German learners highlights that writers may revert to different syntactic structures to express the same semantic relations (that is, the causal relation in Lornez’s (1999) research). This reminds us to interpret the overuse or underuse of any semantic type of conjunctive adverbials with caution. For instance, the underuse of one semantic type of

conjunctive adverbials may be due to the writers’ preference for another syntactic means, such as lexical nouns, to express the same semantic relation, and is not because writers seldom indicate that type of semantic relation in discourse.

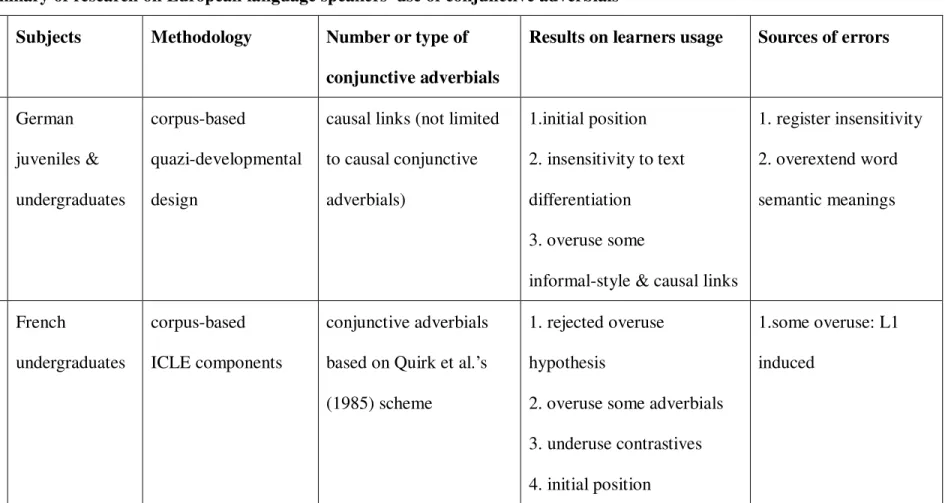

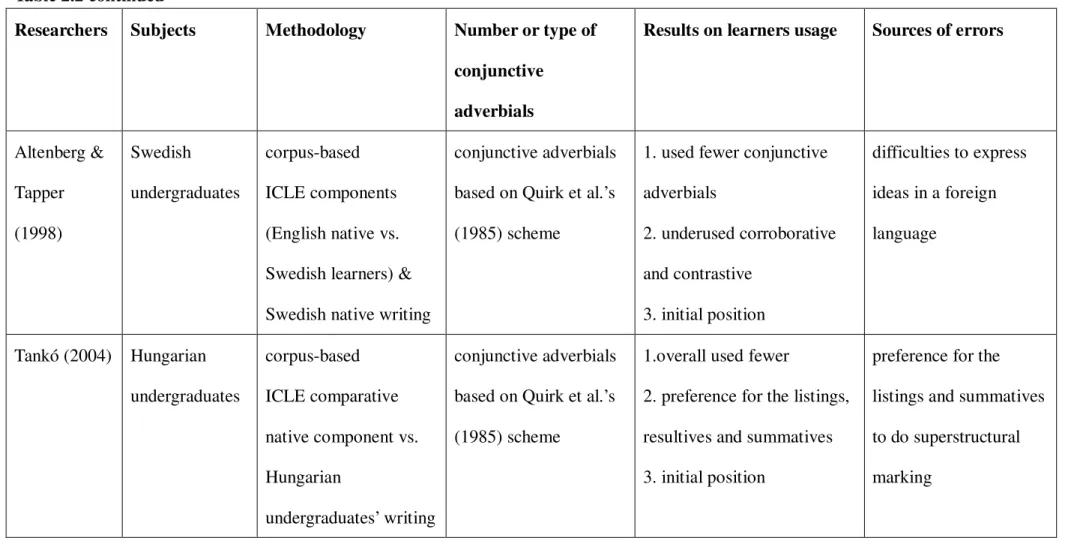

A summary of the European empirical studies on conjunctive adverbials is provided in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2 Summary of research on European language speakers’ use of conjunctive adverbials Researchers Subjects Methodology Number or type of

conjunctive adverbials

Results on learners usage Sources of errors

Lornez (1999)

German juveniles &

undergraduates

corpus-based

quazi-developmental design

causal links (not limited to causal conjunctive adverbials)

1.initial position 2. insensitivity to text differentiation

3. overuse some

informal-style & causal links

1. register insensitivity 2. overextend word semantic meanings

Granger &

Tyson (1996)

French

undergraduates

corpus-based ICLE components

conjunctive adverbials based on Quirk et al.’s (1985) scheme

1. rejected overuse hypothesis

2. overuse some adverbials 3. underuse contrastives 4. initial position

1.some overuse: L1 induced

Table 2.2 continued

Researchers Subjects Methodology Number or type of conjunctive

adverbials

Results on learners usage Sources of errors

Altenberg &

Tapper (1998)

Swedish undergraduates

corpus-based ICLE components (English native vs.

Swedish learners) &

Swedish native writing

conjunctive adverbials based on Quirk et al.’s (1985) scheme

1. used fewer conjunctive adverbials

2. underused corroborative and contrastive

3. initial position

difficulties to express ideas in a foreign language

Tankó (2004) Hungarian undergraduates

corpus-based ICLE comparative native component vs.

Hungarian

undergraduates’ writing

conjunctive adverbials based on Quirk et al.’s (1985) scheme

1.overall used fewer

2. preference for the listings, resultives and summatives 3. initial position

preference for the listings and summatives to do superstructural marking