ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Accident

Analysis

and

Prevention

jo u r n al ho me p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / a a p

Attention

allocation

patterns

in

naturalistic

driving

Jinn-Tsai

Wong

1,

Shih-Hsuan

Huang

∗InstituteofTrafficandTransportation,NationalChiao-TungUniversity,4F,118,Sec.1,ChungHsiaoWestRoad,Taipei10044,Taiwan,ROC

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:Received19July2012

Receivedinrevisedform18April2013 Accepted27April2013 Keywords: Renewalcycle Attention Visualtransition Distraction Naturalisticdriving

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Thekeytosafedrivingistheadequatedistributionofthedriver’sattentiontotheforwardareaand toothernon-forwardfocalpoints.However,thusfar,currentmethodsarenotabletowellquantifythe entireprocessofadriver’sattentionallocation.Therefore,thisstudyproposedanovelconceptofrenewal cyclesforrepresentingandanalyzingdriverattentionallocation.Usingthe100-carnaturalisticglance data,thisstudyfoundthat90.74%ofdrivers’attentionallocationswere2-glancerenewalcycles.The findingssuggestthatthesampledriversusuallyseparatedtheirlapsesofattentionfromtheforward directionintoseveralsequencesbydirectingtheirvisionbacktotheforwarddirectionaftereachvisual shiftawayfromit.Inaddition,althoughamarkedlysmallernumberofcyclesweremorethan3-glances (2.09%renewalcycles),driverswerecertainlylessawareofthefrontalareaandatahigherriskofhaving anaccidentduringsuchcycles.Thisfindingmighthavestrikingimplicationsforaccidentprevention. Thisareaofstudydeservesfurtherattention.Amongthegeneratedrenewalcycles,lotsofthemrepeated frequently,especiallycyclesrelatedtoinvehicledistractions.Toanalyzethedifferentcharacteristics amongvariousattributes,distributionofthecommonrenewalcyclesunderdifferentconditionswas examined.Asexpected,driversdisplayeddifferentrenewalcyclesundervariousroadconditionsand withvariousdriverintentions.Althoughthesesampledriverswerenotrepresentative,thepreliminary researchresultswerepromisingandfruitfulforpotentialapplications,particularlyeducatingnovice drivers.

© 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Exploringthecausesofmotor vehiclecrasheshasbecome a pressingissue.Themajorityofcrashesareconsideredpreventable, providedthatthesurroundingareais properlyobservedbythe driverandadequatemaneuversaresuccessfullyexecuted(Wong etal.,2010).Presumably,misallocatingattentionisoneofthemost criticalcontributingfactorsincrashes(Brownetal.,2000;Mcknight andMcknight,2003;Underwoodetal.,2003;Underwood,2007;Di Stasietal.,2009;Olsonetal.,2009;Chanetal.,2010).Itinhibitsthe driver’sabilitytoperceiveinformationadequatelyandincreases thelikelihoodofacrash.Thus,understandingthepatternsof atten-tionallocation is crucial toanalyzing the relationshipbetween crashesandwaystomaintainsituationalawarenessthroughvisual transition.

Safedrivingrequiresthedrivertopaycontinuedattentionto variousareasandtoconstantlyupdateawarenessofthedriving environment.Locationsorobjectsdonotattractdrivers’attention

∗ Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+886223494995;fax:+886223494953. E-mailaddresses:jtwong@mail.nctu.edu.tw(J.-T.Wong),

andyhuang.tt96g@nctu.edu.tw,andyhuang1983@gmail.com(S.-H.Huang). 1 Tel.:+886223494959;fax:+886223494953.

randomly;specificpatterns drawadriver’s visualfield. In gen-eral,beforeimplementingmaneuveringintentions,driverstendto lookinthedirectionoffuturevehicletrajectories,i.e.,wherethey expectthegreatestnumberofthreatstooccur(SalvucciandLiu, 2002;Underwoodetal.,2002,2003;Nabatilan,2007;Underwood, 2007;Levinetal.,2009).Forinstance,movingforwardconstitutes amajordrivingactivity.Hence,thefrontalareaattractsthemost attentioninalmostalldrivingconditions(Underwoodetal.,2003; Nabatilan,2007;Underwood,2007;Levinetal.,2009).Changing lanesrequiresheightenedattentiontobeinvestedintheadjacent lane(SalvucciandLiu,2002;Underwoodetal.,2003).Enteringan intersectioncompelsdriverstolooktobothsidesoftheintersected roads(Summalaetal.,1996).Inadditiontotheattentionrequired forspecificintendedmaneuvers,driversallocateattentionto sur-roundingareastomaintainawarenessoftrafficconditionsandto preventpossibleconflictscausedbyothervehicles(Crundalletal., 2006).

In otherwords, thekey tosafedriving is theadequate dis-tributionof thedriver’s attentionbothtotheforwardareaand toothernon-forward focalpoints.Shiftingattentionawayfrom the frontal area invites a possible lack of awareness of traffic conditionsaheadandincreasestheunawarenessofsafety consider-ations(Brownetal.,2000).Klaueretal.(2006)statedthatshifting visionawayfromtheforwardarealongerthan2sincreasesthe 0001-4575/$–seefrontmatter © 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

crash/near-crash risk by at least twofold. By contrast, focusing only on the frontal area limits the driver’s awareness of the surroundingtrafficandthetimetoreacttosuddendangers. Knowl-edge of the patterns in which drivers allocate visualattention betweenfrontalandsurroundingareasprovidesinsightintothe information-seeking behavior of drivers and its relationship to safety.Toinvestigatetheseattentionallocationpatterns,weposed thefollowingfourquestions:(1)Howshouldthepatternsbe rep-resented?(2)Dopatternsdriverscommonlyadoptoccur?(3)Ifso, whatarethepatterns?(4)Whatfactorscontributetothepatterns? Beforeanalyzingthecontributionofspecificattributesto atten-tionallocation,anappropriatemethodforrepresentingattention allocationmustbeidentified.Therefore,thisstudyinvestigated(1) methodsforrepresentingattentionallocationpatterns,and(2)the occurrenceofactualrepresentativepatternsoftheavailablesample ofdriversfromthe100-careventdatabase.

2. Methodsforanalyzingattentionallocation

2.1. Currentpracticedmethods

Driverattentionis nota manifest variablethatcan be mea-sureddirectly.Thus,developinganappropriaterepresentationof attentionallocationischallenging.Nevertheless,various represen-tationshavebeenprovidedtoanalyzeseveralaspectsofattention allocation.

Onemethodentailsrepresentingattentionallocationbyusinga singlefocalpoint.Thedurationandfrequencyofdriverstransiting theirvisualfieldstoaspecificdirectionhavebeenintensively stud-ied.Theresultshaveshownthattheportionoftimethatdrivers spendlookingatparticularobjectsorareasisusuallyrelatedto theimportanceoftheareas(Underwoodetal.,2003;Nabatilan, 2007;Levinetal.,2009;Borowskyetal.,2010;Konstantopoulos etal.,2010).Longerglancesaremorelikelydirectedtotheareas ofadriver’shighestsafetyinterest.Inaddition,frequentsaccades usually occurwhena driver quicklygathersinformation under mentallydemandingconditions.

Becausepresentingtheprocessofdriverstransitingvisualfields amongvariousfocalpointsisnotpracticalbyemployingthe single-pointapproach,somestudieshaveusedscanpathstorepresent attentionallocation(Underwoodetal.,2003;Wongand Huang, 2011).Thescanpathmethodexaminesmultipleand sequential focal points to which drivers divert their glance. This method exploresthedetailedbehaviorofdriversshiftingattentionfrom onefocalpointtoanother.Byextractingthescanpath,itprovides additionalinformationondrivers’sequentialprocessesofattention allocationformaintainingsituationalawareness.

However,resultsfromtheaggregatedscanpathshavecontained onlytwoorthreesequentialpointsandhaveshownthatthemost commonpathswereheadingtoward orshiftingawayfromthe frontalarea.Theforwardarea,asthemostattractivefocalpoint, dominatestheprocessofattentionallocation.Usingtheaggregated scanpathmethodmayobscurethecharacteristicsofother non-forwardfocalpoints.Also,thescanpathmethoddoesnotaccount forglancedurations.Driverscantransittheirvisionalongan iden-ticalpathateitherasloworarapidpace.Forexample,anidentical pathofshiftingattentionfromtheforwarddirectiontothe rear-viewmirrorcanbederivedeitherfromalengthyglanceateach focalpointorfromrepeatedlyandrapidlytransitingvisionbetween thetwo. Thesimilarityinscanpathsdoesnotimply equivalent attention-allocationpatternsorstrategies.

In addition,connecting therelated scan pathstogethermay offerrigorousmeaningsthatcorrelate totheassociateddriving activities.Examiningthedeepercharacteristicsofsuchpaths facili-tatesunderstandingofthebehavioralpatternsofdriversallocating

attentioninvariousconditions.Therefore, toanalyzethewhole processofattentionallocation,anewmethodisneeded.

2.2. Theproposedrenewalcycleapproach

Todescribethecompleteprocessofattentionallocationmore clearly,thisstudyexpandedtheconceptofthescanpathtoanalyze attentionallocationusingrenewalcycles.Arenewalcyclerepresents theprocessofshiftingvisionfromareferencepoint,transitingto otherpoints,thenshiftingbacktothereferencepoint. Identify-ingarenewalcyclerequiresdeterminingitsbeginningandending points.Movingforwardis amajoractivityofdriving; thus,this studyregardedtheforwardareaasthefocalpointatwhichdrivers looknaturallyandcomfortably.Theforwardareaisalsothepoint towhich driverseventually return theirattentionaftershifting itaway.Therefore,using“forward”astheinitialreferencepoint, thisstudydefinedarenewalcycleasthedriverdirecting hisor herattentionforward,transitingtootherfocalpoints,andthen returningthegazeagaintotheforwardarea.

Thisapproachnotonlydistinguisheson-andoff-roadglances butalsorepresentsacompletechain processofthedriver shif-tingattentionfromonepointtoanotherandtransitingtheirvision backtothefront.Usingtherenewalcycleasthebasiccomponent ofattentionallocationfacilitatesin-depthexplorationofdrivers’ visualtransitioncharacteristicsamongfocalpoints,especiallythe transition among non-forward focal points. In addition to the extractedpathstransitingtowardorfromtheforwardarea,this methodenablestheinclusionofadditionalserialfocalpointsas apattern toreflect theentireprocessofdriversallocatingtheir attentionduringcertaintasksorevents.Analyzingrenewalcycles canhelpclarifytheinteractionsbetweenforwardandnon-forward glances. For instance, drivers employing different strategies of attentionallocationbyvaryingthedurationsofforwardand non-forwardglancesinonerenewalcyclemayindicatetheirvarious waysofsearchinginformation.

2.3. Theresearchframework

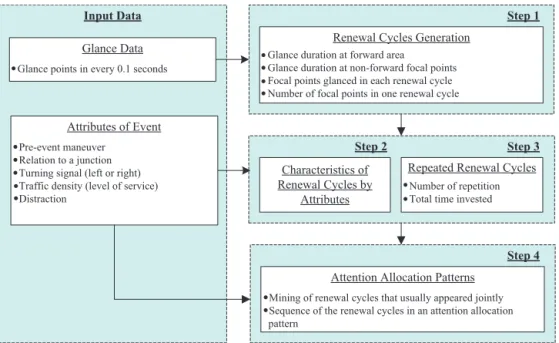

Fig.1shows theresearchframework foranalyzing attention allocationfromarenewalcycleperspective.

Wefirstprocessedtheglancedatathatrecordedevery0.1sinto glancesforeachspecificfocalpoint.Thentheglancesweregrouped intorenewalcyclesanchoredbyforwardglances.Thepurposeof generatingrenewalcycleswastogeneratethebasiccomponent oftheattentionallocationpatterns.However,notallofthecycles wereequallyimportant.Weevaluatedtheimportanceofeachcycle toidentifytheminimumnumberofcommonlyusedrenewalcycles that explain themajority ofattention allocation processes.The indicatorofimportanceadoptedwastherecurringfrequencyof arenewalcycle.Ifaspecifictypeofrenewalcycleoccurredmore frequentlythanothers,itwasconsideredacrucialcycletypically employedby drivers.Then, characteristicsof renewalcyclesby attributeswereanalyzed.

Amongthegenerated renewalcycles,severalidenticalcycles wereundertakenbydriversrepeatedlybeforebeginninganother renewalcycle.Thisrepetitiousbehavioris probablyintendedto preventtheriskcausedbylongglancesawayfromtheforwardarea bytransitingvisionbackandforthbetweentheroadaheadandthe non-forwardfocalpoint.Repeatedrenewalcycleslikelyresultfrom theintentiontocompleteanactivityorcontinualmonitoringof potentialdangerousthreats.Togaindeepinsight,theserepetitious behaviorsarebundledasarepeatedrenewalcycle.

Furthergroupingoftherenewalcycleshelpselucidatethe asso-ciateddrivingactivities.Afterthecommonrenewalcycleswere identified,thisstudychartedtheregularpatternsofattention allo-cationbycombiningtherenewalcyclesthatusuallyoccurjointly.

Glancepointsinevery0.1seconds GlanceData

Glancedurationatforwardarea

Glancedurationatnon-forwardfocalpoints Focalpointsglancedineachrenewalcycle Numberoffocalpointsinonerenewalcycle

RenewalCyclesGeneration

Miningofrenewalcyclesthatusuallyappearedjointly Sequenceoftherenewalcyclesinanattentionallocation pattern

AttentionAllocationPatterns AttributesofEvent

Pre-eventmaneuver Relation to a junction Turningsignal(leftorright) Traffic density (level of service) Distraction

Characteristicsof RenewalCyclesby

Attributes

InputData Step1

Step3

Step 4 Step2

Numberofrepetition Totaltimeinvested RepeatedRenewalCycles

Fig.1.Researchframeworkforattention-allocationanalysis.

Thetechniqueofsequentialassociationrulemininghaslongbeen effectivelyappliedtoexaminefactorscontributingtocrash occur-rence(Geurtsetal.,2005;PandeandAbdel-Aty,2009;Montella, 2011;Montellaetal.,2012).Thus,thisstudyadoptedthismethod tominethepatternsofattentionallocationcomposedofsetsof jointlyoccurringrenewalcycles.Basedontheaprioriprinciple, thesequentialassociationruleminingmethodgeneratespatterns (rules)byrepeatedlyaddingnewrenewalcyclestoexisting pat-terns.Themodel’sperformanceisevaluatedaftereachaddition, andpatternsshowing poorperformance arepruned. A detailed descriptionof themethodcanbefoundin,Introduction toData Mining,byTanetal.(2006).

3. Data

Thisstudyusedthe100-carnaturalisticglancedatacollectedby theVirginiaTechTransportationInstitute(VTTI)(Nealeetal.,2002; Dingusetal.,2006;Klaueretal.,2006).Thereleasedonlinedata includedabaselinedatabaseandaneventdatabase.Thebaseline databasecontainedonly6sofglancedataineachrecord,whichis insufficientforthisanalysis.Therefore,thisstudyadoptedtheevent database,whichcontains68crashesand760near-crashincidents (VTTI,2012).

The100-careventdatabaserecordeddrivers’visualglancesand relatedattributesforthe30sbeforecrashornear-crashincidents. The30-sdurationwasdividedintotwopartsaccordingtothe pre-cipitatingeventsthatwere determinedas causing thecrashor near-crashincidents.Datacollectedaftertheprecipitatingevents wererelated toemergency evasionand crashprevention.Such actionsdonotrepresenttypicaldriverbehavior.Bycontrast,data collectedbeforeprecipitatingeventscouldbeassumedtocontain thetimeperiodthatdriversweredrivingwithoutbeingconsciously affectedbydangersandshouldbesimilartothesampledrivers’ habitual behavior. Therefore, the data before the precipitating event(onaverage25s)wereappliedfortheanalyses.Thedrivers inthe100-careventdatabaseultimatelyexperiencedcrashesor near-crashes.Theresultsderivedinthisstudyonlyrepresentthe commonpatternsofalimitedsampleofdrivers’behavior,which mightincludepotentiallyriskybehaviors.

Table1showstheattributesofthe100-careventdatabaseused inthisstudy.Threetypesofattributeswereused:roadwayand

traffic,drivingtasks,andeye-glancedata.Theroadwayand traffic-relatedattributesdescribed theexternalconditions thatdrivers encountered.Thedrivingtasksincludedthedrivers’distractions, maneuvers,andturningsignals.

Thedrivers’ glancelocations,includingForward (F),Left For-ward(LF),RightForward(RF),LeftWindow(LW),LeftMirror(LM), RightWindow (RW),Right Mirror (RM), Rear-view Mirror (ReM), andIn-vehicleDistractions(InvD),wererecordedevery0.1s.The periodofcontinualglancestothesamefocalpointisconsidered theglanceduration.Amongthesefocalpoints,InvDreferstoall glances inside thevehicles, includingthe center stack, interior objects,cellphone,passengers,andinstrumentcluster.Eachfocal pointreceivedvaryingdegreesofattentionfromdifferentdrivers.

Table1

Attributesof100-careventdatabase.

Attributes Category Roadwayandtraffic

Relationtojunction Non-junction,Intersections(Intersection, Intersection-related,Driveway,alleyaccess), Other(Entrance/exitramp,Railgradecrossing, InterchangeArea,Parkinglot)

Trafficdensity Levelofservice(LOS)AtoF Drivingtasks

Pre-eventmaneuver Drivingstraight(Goingstraightinconstant speed,accelerating,butwithunintentional “drifting”withinlaneoracrosslanes, Deceleratingintrafficlane,Startingintraffic laneorStoppedintrafficlane),LaneChange (Passingorovertakinganothervehicle, ChanginglanesorMerging),Turningleftand Turningright

Distraction(timeseries data)

Cognitive,cellphone,in-vehicledevices, externalclutter,activity

Turningsignal(timeseries data)

Recordedwhenturningsignal(left,rightand both)wereon.

Eye-glancedata Focalpoint(timeseries data)

Forward,Leftforward,Rightforward,Rearview mirror,Leftwindow,Leftmirror,Right window,Rightmirror,In-vehicledistractions (InstrumentClutter,Centerstack,Interior Object,Passenger,CellPhone)

Durationofglancingat forwardandotherfocal points

Tosimplifytheanalysis,thisstudyfirstanalyzedonlytheareas wheredriversglance,i.e.,theInvD.Detailedcharacteristic differ-encesamongmultiplelocationsorobjectsinsidethevehicleswere notconsidered.

Thisstudyexcludedthefirstandfinalglancesofeacheventin theglancedatabecausewecouldnotbesurewhethertheywere completeglances.Anyeventswithaglancedarearecordedas“eyes closed”or“novideo”werealsoexcluded.

4. Results

4.1. Generatedrenewalcycles

Intotal,2256renewalcycleswith91typesweregenerated.The shortestrenewalcyclescontainedonlytwoglances:oneforward andonenon-forwardfocalpoint.Thelongestcyclecontained12 glances.

AsshowninTable2,themostfrequentrenewalcycleswere 2-glancecycles,with90.74%ofthedatafallingintothiscategory.A markedlysmallernumberofcycleswere3-glance,at7.18%;and 4-glancecyclesaccountedforonly1.24%.Renewalcycleswith5or moreglancesaccountedfor0.85%ofthedata.Thisfindingsuggests that,ratherthanlookingsequentiallyatvariousfocalpointswithin asinglerenewalcycle,thesampledriversusuallyseparatedtheir lapsesfromtheforwarddirectionintoseveralsequences,directing theirvisionbacktotheforwarddirectionaftereachvisualshift.

The mean glance duration revealed that the sample drivers spend 3–4s glancing forward and 1s looking elsewhere. An increased number of non-forward glances per renewal cycle resultedin a longercycle duration but a concomitantdecrease intime spentlookingforward, i.e.,decreased mean,maximum, and standard deviation for forward-glance. The mean duration ofeachglanceatnon-forwardfocalpointsdidnotvary substan-tiallyacrossrenewalcycleswithvaryingnumberofglancepoints. However,thetotaltimethatdriversspentglancingoff-road dra-maticallyincreasedfrom0.96sin2-glancerenewalcyclesto3.00s in4-glancerenewalcycles.Thisresultindicatesthatahigher pro-portionofattentionspentonmultiplenon-forwardfocalpointsin arenewalcyclewasnotcompensatedforbyshortercycleduration. Nevertheless,there is a decreasein maximum and standard deviationofdurationonbothforwardandnon-forwardfocalpoints in3-and4-glancerenewalcycles.Thissuggeststhatthesedrivers triedtoavoidabnormalrenewalcyclesthatinvolveddangerously longglances.Thefindingsmightillustratethedriver’suneasiness whenadditionalfocalpointswereglancedatinarenewalcycle.The driverswhoshowedmoreglancesinarenewalcyclewerecertainly lessawareofthefrontalareaandincurredahigherriskofan acci-dent.Thus,the2.09%renewalcyclesthatshowedmorethanthree glancesmighthavestrikingimplicationsforaccidentprevention. Thisareaofstudydeservesfurtherattention.

4.2. Characteristicsofrenewalcyclesbyattributes

Table3showsthedistributionofthecommonrenewalcycles undervariousattributes.Thereweretentypesofrenewalcycles with more than a 1% frequency share, whereas eight types of 2-glancerenewalcyclesaccountedfor 90.74%of thefrequency. Amongthe2-glancerenewalcycles,thoseinvolvingin-vehicle dis-tractionsandrear-viewmirrorglancesaccountedforalmosthalfof thegeneratedrenewalcycles.

To analyze the characteristic differences among various attributes,thedistributionofthesecommonrenewalcyclesunder differentconditionswasexamined.Therecordedmaneuversand theirrelationtoajunctionwerereferredtothefinalpronounced actionandassociatedlocationbeforeaprecipitatingevent.Such

attributes did not necessarily exist throughout the entire 30-s dataperiod.Certainly,thegeneratedrenewalcyclesmightoccur before or during the maneuvering. Thus, it seems that a mis-matchoftimeexistsbetweeneye-glancedataandcertaindriving circumstances.Nevertheless, beforeimplementing maneuvering intentions,drivers tendtolookinthedirectionsoffuture vehi-cletrajectories.Thatis,theentiremaneuverincludessearchingfor information,decision-making,andthefinalaction.Analyzingonly theexactperiodof themaneuverdoesnotrepresenttheentire attentionallocationprocess.Thus,fromthisviewpoint,the mis-matchproblemisignored.

Theattributesofarelationtoajunctionandmaneuverwere important for determining a driver’s expectations of potential threats.Inthesecases,arelationtoajunction,roadsegmentsand intersections werethe two main elementsin thedriving envi-ronment.Whenthedriversencounteredintersectionswithin30s, morerenewalcyclesofRFandRWwouldoccur,probablybecause oftheassociatedpossibilityofincreasedconflictsfromthe inter-sectedroadway.Simultaneously,theyallocatedlessattentionto therearsidethroughtheLM,RM,andReM.

Lanechangingandturningwerethetwoprimarymaneuvers that naturally directed the drivers’ attentionto directions crit-ical for preventing conflicts. Meanwhile, drivers decreased the attentioninvestedinnon-safetyrelatedareas,suchasInvD.The percentage oftherenewalcyclesinwhich thedriverstransited attentiontoInvDdecreasedfrom26.4%whendrivingstraightto 12.4%whenchanginglanes,andto17.4%whenturningleftorright. Whilechanginglanes,thesampledriversincreasedtheirattention totheReMandLMtoobservethetrafficconditionsbehindthem.

Inparticular,thedriverstransitedtheirvisionmorefrequently totheleftside(LWandLM)whenchangingtotheleftlane,andto therightside(RFandRW)whenchangingtotherightlane.Themain differencebetweenchangingtoleftorrightlaneswastheuseofthe sidemirrors.TheRMwasseldomusedwhenchangingtotheright lane.Onereasonmightbethefasterdrivingspeedintheinner(left) lane.Vehicleslocatedintherightrearareawereusuallytraveling relativelyslowly.Oncethedrivershadsuccessfullypassedthose vehicles,theyhadgoodinformationforwherethevehiclewasand couldeasilybeginchanginglanestotherightsidewithoutglancing attheRM.Bycontrast,vehiclesintheleftlaneusuallytraveledmore rapidlyandrequireddrivers’closeattentiontoensureasafemargin forchanginglanestotheleft.

Turningatintersectionswasindicatedtohaveanincreasedrisk ofcrashingwithtrafficfromanintersectingroadwayinfrontofthe subjectvehicles.Anincreasednumberofrenewalcyclesinvolving LF,RF,andLWglanceswerefound.Formaneuveringaleftturn, theLW,LF,andRFwerethemostcommonfocalpointsfor check-ingthepotentialthreatscomingfromoppositetraffic.Glancingat thosefocalpointsimpliedthatthreatswereexpectedfromthe traf-ficpassingthroughintersections.Anotheruniquecharacteristicof turningleftwasthehighpercentageofthepathfromForwardto InvD(F-InvD).Turningwasusuallyassociatedwithcomplextasks andfewchancesofshiftingone’sattentiontoInvD.However,the driversweremorelikelytostopandwaitattheintersectionwhen turningleftthanwhenturningrightandchanging lanes.In the absenceofimmediatecrashrisks,driversmaybeinclinedtouse in-vehicledevicesorinteractwithpassengerswhilewaiting.Fora rightturn,morepotentialconflictswererelatedtothetrafficfrom theintersectedroadway,pedestriansonthecrosswalk,andcars followingbehind.Thus,thesampledriverspaidgreaterattention tomonitoringtheReM,LW,andRW.

Traffic density determined interactions with other vehicles. WhentrafficdensityincreasesfromLevelofService(LOS)AtoD,the sampledriversallocatedmoreattentiontotherear-viewandleft mirrors,probablycheckingtrafficfrombehindorforlanechanging. Moreover,thenecessityforfrequentspeedadjustmentsandthe

Table2

Numberofglancesinrenewalcycles.

Numberofglances

2 3 4 5ormore Total

Frequency(%) 2047(90.74%) 162(7.18%) 28(1.24%) 13(0.85%) 2256(100%) Durationofforwardglance(s)

Mean 4.01 3.52 3.04 3.16 3.95

Standarddeviation 4.91 5.04 4.19 3.15 4.89

Maximum 29.2 23.4 17.7 11.6 29.2

Durationofeachnon-forwardglance(s)

Mean 0.96 0.96 1.00 0.98 0.96

Standarddeviation 0.93 0.71 0.48 0.70 0.91

Maximum 10.50 5.20 2.40 2.50 10.50

Meandurationofarenewalcycle(s) 4.96 5.43 6.04 8.25 5.05

shorteravailablereactiontimeassociatedwithheavytraffic dis-couragesdriversfromengaginginnon-driving-relatedtasks,such astransitingtheirvisionfromtheforwardareastotheroadside areas(LW,RW,and RF)orattending toInvD.Whentraffic den-sityincreasedtoLOSE,thesampledriverswereunabletooperate theirvehiclesfreelybutwereforcedtoremaininthetrafficstream. Undersuchconditions,drivershadampleopportunitiestouse in-vehicledevices becauseoftheslowtravelingspeedand limited gapsavailabletomergewithothervehicles.Thus,thepercentage ofInvDclimbedsharplyfrom19.0%underLOSDto29.9%underLOS E.

Amongthecommoncycles,InvDwerethemainfocalpointson whichthedriversspentalargeportionoftheirnon-forward atten-tiontime.AsshowninTable3,whendistractionswerepresent, F-InvDcontributed45.3%oftheextractedrenewalcycles.However, intheabsenceofdistractingactivities,16.8%oftherenewalcycles werestillrelatedtoF-InvD.Thesefindingssuggestthatengagingin distractingactivitywasnottheonlyreasonthatthedrivers tran-sitionedtheirvisiontoin-vehiclefocal points.Attimes,drivers transitedvisioninsidetheirvehicles,despitedoingnothingwith in-vehicledevices.Becausethesampledriversrepresentedbythis dataseteventuallyexperiencedcrashesornearcrashes,itis rea-sonabletopresumethatdefectivebehaviormighthaveoccurredin theirdailydrivingoperations.

4.3. Repeatedrenewalcycles

Occurrenceofrepeatedrenewalcyclescouldbeconsideredan intentiontocompleteasingletaskofobtaininginformationfrom specificfocalpoints,continuallycheckingtheareaofinterest,or reconfirmingtrafficsituationsbeforemaneuvers.Thus,thetimes ofrepetitionandtotaldurationprovidemeaningfulmeasuresthat representthedifferentapproaches ofdrivers inallocating their attention.Table4showsthedurationofeachnon-forwardglancein commonlyfound2-glancerenewalcycles,forbothindividualand repeatedrenewalcycles.

The focal point showingthe highest percentage of repeated renewalcycleswasInvD,of which 79.15% occurredrepeatedly. Among therepeatedsamples, onaverage, drivers repeatedthe renewalcycles3.58times. Forthetotal duration ofglancing at InvD,the sample driversspent 2.68sonaverage. BecauseInvD representedallglances insidethevehicle,therepeatedrenewal cyclemaycontain differenttypesof distractions.Consequently, accurateinterpretationcouldbedifficult.Fortunately,only94out of429repeatedrenewalcyclesofInvDmixed withothertypes ofdistraction.Thesefindingssuggestthat InvDtendtobe rule-andknowledge-basedactivitiesthatconsumesubstantialattention resourcestocompletecertainnon-drivingrelatedactivities,such asmakingaphonecall.

Table3

Distributionofrenewalcyclesbyattributes.

Attributes Samplesize Distributionofrenewalcycles(%)

F-InvD F-ReM F-LW F-LM F-RF F-RW F-LF F-RM F-LM-LW F-RF-RW Others Pre-eventmaneuver

Drivingstraight 1827 26.4 22.3 13.5 9.6 8.1 6.2 3.9 1.4 1.0 0.8 6.8 Changinglanes 306 12.4 29.1 10.5 16.3 7.2 6.5 2.9 2.0 2.6 2.6 7.8 Turningleftorright 116 17.2 19.8 22.4 0.9 16.4 2.0 6.0 0.9 0.0 0.9 10.3 Others 7 28.6 42.9 0.0 0.0 14.3 0.0 14.3 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Turningsignal

Changingtoleftlane 44 2.3 20.5 15.9 38.6 2.3 0.0 6.8 0.0 9.1 0.0 4.5 Changingtorightlane 43 7.0 23.3 4.7 7.0 9.3 18.6 0.0 4.7 4.7 7.0 14.0 Turningleft 24 25.0 4.2 25.0 0.0 12.5 4.2 16.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 12.5 Turningright 21 0.0 23.8 23.8 0.0 19.0 9.5 4.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 19.0 Relationtoajunction Roadsegment 1336 26.5 25.1 12.7 10.5 6.2 5.6 3.7 1.6 1.3 0.8 5.9 Intersection 582 24.2 20.1 13.9 6.5 12.5 7.2 4.0 1.2 0.3 1.5 8.4 Others 338 13.9 20.4 15.7 14.5 10.1 6.8 5.0 1.5 1.8 0.9 9.5 Trafficdensity Levelofservice:A 599 27.7 19.5 16.5 5.3 8.8 6.7 4.0 0.8 0.8 0.8 8.8 Levelofservice:B 822 22.7 22.3 14.8 8.9 9.7 6.1 4.0 1.1 1.5 1.6 7.3 Levelofservice:C 536 23.3 25.9 10.8 14.0 8.0 6.7 3.2 2.2 0.7 0.2 4.9 Levelofservice:D 232 19.0 26.3 9.1 16.4 5.2 5.6 6.0 2.6 1.3 1.7 6.9 Levelofservice:E 67 29.9 32.8 6.0 13.4 3.0 1.5 1.5 1.5 3.0 0.0 7.5 Levelofservice:F 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Distraction

Drivingwithdistraction 572 45.3 16.1 9.1 6.6 5.9 4.4 1.6 1.2 1.4 0.3 7.0 Drivingwithoutdistraction 1684 16.8 22.5 15.0 11.2 9.3 6.8 4.4 1.5 1.1 1.2 7.1 Total 2256 24.0 23.1 13.5 10.1 8.4 6.2 4.0 1.5 1.2 1.0 7.1

Table4

Glancedurationfornon-forwardfocalpoints.

Focalpoint Durationandfrequencyofeachglance Timesofrepetitiona Averagetotalduration(s)b

Individualrenewalcycle Repeatedrenewalcycle

Frequency Duration(s)mean/std. Frequency(%) Duration(s)mean/std.

InvD 542 1.14/1.04 429(79.15%) 1.19/1.10 3.58 2.68 ReM 522 0.64/1.03 312(59.77%) 0.66/0.54 2.90 1.05 LM 227 0.85/1.02 134(59.03%) 0.86/0.64 2.91 1.37 RM 33 0.82/0.38 14(42.42%) 0.84/0.38 2.80 1.13 LW 304 1.00/0.50 156(51.31%) 0.96/1.04 2.59 1.50 RF 190 1.08/0.68 69(36.32%) 1.01/0.98 2.48 1.37 RW 140 1.10/1.00 50(35.71%) 1.12/0.88 2.27 1.39 LF 89 1.16/0.95 26(29.21%) 0.97/0.79 2.36 1.44

aThecalculationofrepeatedtimesincludedonlytherepeatedrenewalcycles. bBothindividualandrepeatedrenewalcyclesareincluded.

InvDwerefollowedbyReM,LM,andRMglances,which respec-tivelyshowed59.77%,59.03%,and42.42% oftherenewalcycles beingrepeated,witheachrepeatingapproximately2.8–2.9times. Theserepeatedrenewalcyclesrelatingtomirrorsshowedalmost identicalmeandurations,butlessvariancewhencomparedtothe mean durations of theindividual renewalcycles. These results suggestthatdriverswereawareoftheriskofpayinginadequate attentionto theforwarddirection byrepeatedly searching and reconfirmingactivities.However,thestableduration of glances impliedarequiredminimumtimeforthedriverstotransittheir visionandprocessinformation.Consequently,whenfacingtasks that pose a high information load,drivers might beunable to decreasethedurationofeachglancebyincreasingtheirsampling rates.

Thesampledriversalsofrequentlyrepeatedtherenewalcycles fortheLW,RF,RW,andLF,andspentapproximately1.4sto com-pletethesearchactivity.Amongthesefourfocalpoints,theLW andtheRFfield,representingtheroadsideareas,showedalarger standarddeviationforglancedurationinrepeatedrenewalcycles thanthatforindividualones.Thisphenomenonmightbe associ-atedwiththedrivers’reactiontothedifferenttargetsalongthe roadside.Theymightglanceatthoseareaslongerandrepeatmore frequentlyifinterestingobjectsontheroadsideattracttheir atten-tions.Intheabsenceofinterestingobjects,driverstendedtotransit theirvisiontotheroadsideareasbriefly.

ThesampledriversglancedattheRWforshorterintervalsand repeatedlessfrequentlythantheglancestotheLW.Differences betweenglancestothesetwowindowswereprobablyrelatedto thelocationofthedriver’sseat.DriverssitbesidetheLWandcan easilyandcomfortablytransittheirattentiontoenjoyscenicviews throughthiswindow.Thus,theLWfocalpointshowedanincreased numberofrepeatedrenewalcyclesandlongerglancedurations whencomparedtothatoftheRW.Finally,unliketheRFview,the LFfieldcouldbelargelycoveredbythedriver’speripheralvision offorwardglances.Consequently,thepercentageofrenewalcycles fortheLFfieldwasthelowestamongallfocalpointsandshowed theleastrepetition.

In addition to gathering/confirming identical information, repeatedrenewalcyclesmightalsorepresentthetaskof contin-uedobservationofanareafornewcircumstances.Insuchcases, therenewalcyclesthat occurredrepeatedlymightbeunrelated andsimplyreflectacommonmannerofdriving.Thequestionis howtotelltheunrelatedonesfromtherelatedones.The inter-glanceintervals ofthenon-forward focal point inthe repeated renewalcyclescouldbegoodforjudgment.Resultsofthe inter-glanceintervalsshowedthatabigportionoftherepeatedrenewal cyclesrelatedtoInvD,RW,RM,andLMhadrelativelyshort inter-glanceintervals(3.2–3.5s)andweremorelikelyforcollectingand reconfirminginformationfromthesametarget.Ontheotherhand,

someoftherepeatedrenewalcyclesrelatedtotheReMhad rela-tivelylonginter-glanceintervals(4.5s),suggestingprobablyjusta commonmannerofdriving.

4.4. Attentionallocationpatterns

One might ask whether the generated renewal cycles were interrelatedornot.Toanswerthisquestion,theSequential Associ-ationRuleMiningpackageinSASEnterpriseMiner6.2wasusedto minethesequentialassociationbetweenrenewalcyclesand com-binerelatedcyclesintopatternsofattentionallocation,wherethe minimumsupportinthisstudywassetat5%andtheminimum con-fidenceat10%.Asstated,driversdisplayeddifferentrenewalcycles undervariousroadconditionsandwithvariousdriverintentions. Hence,drivingstraightonasegment,passingthroughan intersec-tion,andchanginglanesonasegmentwereseparatedtominethe respectivesequentialassociationrules.Othertypesofmaneuvers werenotincludedbecauseofthesmallsamplesize.Table5shows thederivedattentionallocationrulesofthesampledriversforthe threemaneuverintentions.

TherenewalcyclesthatincludedtheReMoccurredinalmost allextractedpatternsofattentionallocation.Thisfindingsuggests thatpayingattentiontothefrontandrearareasofthevehiclewere thetwomostcrucialcomponentsforobservingthesurrounding trafficandmaintainingsituationalawareness.Thesampledrivers usuallytransitedtheirvisiontothesetwoareasimmediatelybefore oraftershiftingtheirattentionelsewhere.

Drivingstraightonaroadsegmentisrelativelysimpleandhasa lightinformationload.Inadditiontothementionedcrucialrenewal cycles,thedriverstravelingstraightonaroadsegmentdisplayed thepatternrelatedtoInvDandLWglances.Thesecycles contain-ingnon-drivingrelatedinformationand,whencombinedwiththe above-mentionedcrucialcycles, formedtheattentionallocation patternfordrivingstraightonaroadsegment.Suchanattention allocationpatterncanbedescribedasdriverscomfortablyfocusing onthefrontandrearareas,butintermittentlyandcasuallydirecting theirattentiontodistractionsontheroadsideorinsidethe vehi-cles.Thedriversalsodisplayedthecautiousbehavioroftransiting theirvisionfromtheLMtotheReMtomaintaintheirsituational awarenessofthereararea,probablytomonitortheblindzoneon theleftside.

For the maneuver intentionof passing through an intersec-tion,thedriversexperiencedarelativelyheavytaskloadbecause ofpossiblethreatsarisingfromtheintersectingtraffic.Compared withdrivingstraightonaroadsegment,fewernotablepatternsof renewalcycleswereevidentbecausethedriversweremore cau-tiousandconcentratedonafewcriticalfocalpointswhenpassing throughanintersection.Apartfromconcentratingonforwardand backwardareas, therenewalcyclepattern F-RF→F-LW showed

Table5

Attentionallocationpatternsofvariousmaneuverintentions.

Patternsofrenewalcycles Drivingstraightonasegment Passingthroughanintersection Changinglanesonsegment Supporta Confidencea Supporta Confidencea Supporta Confidencea

F-InvD→F-ReM 9.23 24.51 5.97 18.18 9.09 42.86 F-ReM→F-InvD 8.49 16.43 8.21 23.4 – – F-LW→F-ReM 5.54 18.75 – – – – F-ReM→F-LW 5.54 10.71 – – 10.61 20.59 F-LM→F-ReM 6.64 29.51 – – 9.09 27.27 F-ReM→F-LM – – – – 9.09 17.65 F-ReM→F-RF – – – – 6.06 11.7 F-RF→F-ReM – – – – 7.58 35.71 F-RF→F-LW – – 5.22 20.59 – –

Numberofcrashesornearcrashes 271 134 66

–:nopatternfound.

aTheconfidenceandsupportvaluesareexpressedaspercentages.

thatthedriversdidnottransittheirvisionfarfromonesideofthe vehicletotheotherside,i.e.,renewalcycleF-RF-LW.An intermedi-ateglanceattheforwardsidewasadopted.Thesampledrivers usually looked to RF field initially, where conflicts with right-turningtrafficwouldoccur.Afterwardtheyturnedtheirvisionto theLWtocheckforpossibletrafficemergingfromtheintersected road.

Whenchanginglanes,driversmayencounterthreatsfrom mul-tiple directions and must expend heightened effort toprevent possibleconflicts,particularlyconflictsfromtheadjacentlanes. Undertheseintensecircumstances,thesampledrivers’InvDwere minimizedandattentiontotherearandsideareaswas strength-ened.ThisfindingsuggeststhattheReMwasusedinanauxiliary mannertoenhancethedrivers’situationalawarenessoftherear area,andthattheLMwasusedtomonitortheblindzone.Compared withtheintentionsofdrivingstraightonasegmentandpassing throughanintersection,thedriversevidentlyconsideredchanging lanestobeamorementallydemandingtask.Thus,afterarenewal cycleforInvD,arelativelyhighproportion(42.86%)ofthedrivers immediatelytransitedtheirvisiontotheReMtogaininformation ofthereararearelevanttochanginglanes.

5. Conclusion

Thisstudyproposestheconceptoftherenewalcycleto ana-lyzetheentireprocessofdriverattentionallocationtounderstand themannerinwhichvisionistransitedamongvariousfocalpoints. Analysesofrenewalcyclesenabledidentificationofthe character-isticsassociatedwitheachfocalpointandtheattentionpatterns thatoccurmostfrequently.Althoughthesesampledriverswere notrepresentative,theresultswerepromisingandmanyofour findingsofferpotentialforpracticalapplication.

5.1. Usingrenewalcyclestoexploreattentionallocation

Insteadoftreatingallfocalpointsindividually,therenewalcycle conceptallowsexaminationofthechainprocessandinteraction amongforwardandnon-forwardglances.Morethan90%ofthe renewalcyclesidentifiedinthisstudycontainedonlyoneglance awayfromtheforwarddirection.Alargeproportionofthesecycles occurredsuccessivelyandrepeatedly;thatis,thedriversmight sep-aratealongglanceatonefocalpoint,particularlyInvD,intoseveral repeatedshortrenewalcycles.Thisfindingsupportsthe hypoth-esisthatshiftingattentionawayfromtheforwardareadecreases thedriver’sawarenessofthetrafficahead.Thus,thesampledrivers generallyavoidedlookingawayfromtheforwardareaforlengthy durations.

Thedurationofrepeatedrenewalcyclesmayindicatethe invest-mentofmentalresourcesinaninformationsource.Becausedrivers

separate lengthy glances on a focal point into several shorter successiverenewalcycles, thetraditionalmethodsforanalyzing theduration of each glancemayunderestimatethe total effort expended on certain focal points. Analyzing the total duration of glances over repeated renewal cycles provides vital insight intothemannerinwhichdriversmanageinformationperception and/orreconfirmationoftrafficconditions.Anotheradvantageof therenewalcycleapproachoverthatofthescanpathisthatit pro-videsaclearerunderstandingofthevisualtransitionsamongfocal points.Inthetraditionalscanpathapproach,themostsignificant pathcomprisesvisualtransitionstoorfromthefrontalarea,the mostdominantfocalpoint.Thismethodcannotthoroughlyreflect allvisualtransitsaroundthevehicle.Byusingrenewalcyclesas thebasiccomponentofattentionallocation,twoseemingly dis-tinctscanpathscanbecombinedinanattentionallocationpattern thatillustratesthechainprocessesofdriversglancingatsequential focalpoints.

Asexpected, maneuvers that entaildifferenttask loads cre-atedistinctpatternsofattentionallocation.Moreover,thedrivers exhibited patterns of transiting vision to the roadside or to in-vehicledevicestogainnon-drivingrelatedinformationless fre-quentlywhentheywerebusyperformingmaneuverswithhigher taskloads.Thisfindingsuggeststheexistenceof compensatory behaviortopreventcrashesbyallocatingincreasedattentionto wheretheriskisincreased(LiuandLee,2005;TörnrosandBolling, 2006).Nevertheless,insomeriskysituations,suchasdrivingunder LOSD/E,InvDwerefoundtooccurmostfrequentlyamongall non-forwardfocalpoints.Driverswhooverestimated theirabilityto handlebothdistractionactivitiesanddrivingtasksplaced them-selvesatincreasedriskofhavingacrash,especially underpoor drivingconditions.Hence,managingdistractionisclearlyvitalfor improvingdrivingsafety.Detailedanalysisofdistractedbehaviors andtheirimplicationsfordesigningeffectiveinformationsystems warrantfurtherresearch.

5.2. Policyimplications

Thedriversinthe100-careventdatabaseusedinthisstudy experiencedcrashesornear-crashes.Thisimpliesthatthesedrivers mighthaveperformedinadequatedrivingbehaviors.Theresultsof sampledrivers’attentionallocationfromarenewalcycle perspec-tiveinvolvecertainimplicationsforpreventingcrashes.

Thecontentofinformationofferedtodriversandthemanner inwhichtheinformationisusedareextremelyrelevanttosafety improvement.Thenegativeeffectsofusingin-vehicledevices,such ascellphonesornavigators,havebeenwidelydiscussed(Patten etal.,2004;Horreyetal.,2006;Mcevoyetal.,2007;Cairdetal., 2008;Kassetal.,2010;Thompsonetal.,2012).Thelongeradriver transitsvisionawayfromtheroadwaytogainextrainformation,

thegreaterthedangeroflosingfullawarenessofthetraffic sit-uationahead.Toevaluatetheeffectofaninformation system,a thresholdforinformation-processing,suchastheruleof2-s off-roadglanceproposedbyKlaueretal.(2006),shouldbeconsidered. Inthisstudy,alargeportionofrenewalcyclesthatcontainedmore thanonenon-forwardglancewereevidentlyoverthesafety thresh-old.Theinformation loadand mannerof obtaininginformation haveclearimplicationsfortrafficsafety.Rememberthattheright messageisrequiredtochangedrivers’behavior.Thepossibleside effectsofdistractingadriver’sattentionmustbeconsideredwhen designinganintelligentsafetyinformationsystem.Safety perfor-manceofaninformationsystemshouldbeanalyzedbasedonthe dimensionsofminimizingrepetition,totalduration,andduration ofeachglancewhendriversseekinformation.

Attentionallocationwasregarded asa criticalindicatorthat distinguishedexperienceddriversfromnovices,andsafedrivers fromunsafeones(Konstantopoulosetal.,2010).Thekeyconcern ofinformationseekingisthemannerinwhichdriverstransitvision among various information sources. The drivers’vision transit-ingawayfromforwardformorethantwoglancesmightindicate thattheydidnotallocatetheirattentionresourcesproperlyand efficiently.Inthisstudy,inadditiontothe10typesof representa-tiverenewalcycles,wefoundanadditional81typesofirregular renewalcycles,which contributedtotheremaining10% of fre-quency.Inotherwords,asubstantialproportionofrenewalcycles maybeatypical.Althoughthisstudydidnotfocusonthe character-isticsofatypicalorirregularrenewalcyclesanddidnotdistinguish experienceddriversfromnovices,futureresearchshould inves-tigatetheproblemoflongglances awayfromtheforwardarea. Suchprospectiveresearchcouldbefruitfulforeducatingdrivers, particularlynovicedrivers.

Finally,thisstudycontributestotheknowledgeofbothessential andnonessentialfocalpointsintermsofsafety.Thesefindingscan beapreliminarystepforfutureresearchtoevaluatetherisk asso-ciatedwithdriversshiftingattentionawayfromforwardareas,and toidentifythesafetythresholdforattentiondistractionrequiredto reducetrafficcrashes.Bymonitoringdrivers’eyemovementsand comparingthepatternswithregularattention-allocationpatterns ofsafedriving,abnormalbehaviorcouldpotentiallybedetected. Safetyinformation systemsmight beabletoalert thedriverto lapsesinattentionorperhapsprovideautomaticcontrolattimes tohelppreventcrashes.

Acknowledgments

Theauthorswouldliketothankthereviewersfortheir insight-fulcommentsandtheNationalScienceCouncil,Taiwan,Republic ofChinaforfinanciallysupportingthisresearch(NSC 100-2221-E-009-120-MY3).

References

Borowsky,A.,Shinar,D.,Oron-Gilad,T.,2010. Age,skill,andhazardperceptionin driving.AccidentAnalysisandPrevention42(4),1240–1249.

Brown,T.,Lee,J.,Mcgehee,D.,2000.Attention-basedmodelofdriverperformancein rear-endcollisions.TransportationResearchRecord:Journalofthe Transporta-tionResearchBoard1724,14–20.

Caird,J.K.,Willness,C.R.,Steel,P.,Scialfa,C.,2008. Ameta-analysisoftheeffects ofcellphonesondriverperformance.AccidentAnalysisandPrevention40(4), 1282–1293.

Chan,E.,Pradhan,A.K.,Pollatsek,A.,Knodler,M.A.,Fisher,D.L.,2010.Aredriving sim-ulatorseffectivetoolsforevaluatingnovicedrivers’hazardanticipation,speed management,andattentionmaintenanceskills?TransportationResearchPart F:TrafficPsychologyandBehaviour13(5),343–353.

Crundall,D.,VanLoon,E.,Underwood,G.,2006.Attractionanddistractionof atten-tionwithroadsideadvertisements.AccidentAnalysisandPrevention38(4), 671–677.

DiStasi,L.L.,lvarez-Valbuena,V.,Ca ˜nas,J.J.,Maldonado,A.,Catena,A.,Antolí,A., Can-dido,A.,2009. Riskbehaviourandmentalworkload:multimodalassessment

techniquesappliedtomotorbikeridingsimulation.TransportationResearch PartF:TrafficPsychologyandBehaviour12(5),361–370.

Dingus,T.A.,Klauer,S.G.,Neale,V.L.,Petersen,A.,Lee,S.E.,Sudweeks,J.,Perez,M.A., Hankey,J.,Ramsey,D.,Gupta,S.,Bucher,C.,Doerzaph,Z.R.,Jermeland,J., Kni-pling,R.R.,2006. The100-CarNaturalisticDrivingStudy,PhaseII–Resultsof The100-CarFieldExperiment.NationalHighwayTrafficSafetyAdministration, DC,DOT-HS-810-593.

Geurts,K.,Thomas,I.,Wets,G.,2005.Understandingspatialconcentrationsofroad accidentsusingfrequentitemsets.AccidentAnalysisandPrevention37(4), 787–799.

Horrey,W.J.,Wickens,C.D.,Consalus,K.P.,2006.Modelingdrivers’visualattention allocationwhileinteractingwithin-vehicletechnoligies.Journalof Experimen-talPsychological:Applied12(2),67–78.

Kass,S.J.,Beede,K.E.,Vodanovich,S.J.,2010.Self-reportmeasuresofdistractibilityas correlatesofsimulateddrivingperformance.AccidentAnalysisandPrevention 42(3),874–880.

Klauer,S.G.,Dingus,T.A.,Neale,V.L.,Sudweeks,J.D.,Ramsey,D.J.,2006.TheImpact ofDriverInattentiononNear-Crash/CrashRisk:AnAnalysisUsingThe100-Car NaturalisticDrivingStudyData.NationalHighwayTrafficSafetyAdministration, DC,DOT-HS-810-594.

Konstantopoulos,P.,Chapman,P.,Crundall,D.,2010. Driver’svisualattentionasa functionofdrivingexperienceandvisibility.Usingadrivingsimulatortoexplore drivers’eyemovementsinday,nightandraindriving.AccidentAnalysisand Prevention42(3),827–834.

Levin,L.D.,Henriksson,T.,Mårdh,P.,Sagberg,S.F.,2009.OlderCarDriversinNorway andSweden–StudiesofAccidentInvolvement,VisualSearchBehaviour, Atten-tionandHazardPerception.VTI,Norway,VTIrapport656A.

Liu,B.-S.,Lee,Y.-H.,2005.Effectsofcar-phoneuseandaggressivedispositionduring criticaldrivingmaneuvers.TransportationResearchPartF:TrafficPsychology andBehaviour8(4/5),369–382.

Mcevoy,S.P.,Stevenson,M.R.,Woodward,M.,2007. Thecontributionof passen-gersversusmobilephoneusetomotorvehiclecrashesresultinginhospital attendancebythedriver.AccidentAnalysisandPrevention39(6),1170–1176. Mcknight,A.J.,Mcknight,A.S.,2003. Youngnovicedrivers:carelessorclueless?

AccidentAnalysisandPrevention35(6),921–925.

Montella,A.,2011.Identifyingcrashcontributoryfactorsaturbanroundaboutsand usingassociationrulestoexploretheirrelationshipstodifferentcrashtypes. AccidentAnalysisandPrevention43(4),1451–1463.

Montella,A.,Aria,M.,D’ambrosio,A.,Mauriello,F.,2012.Analysisofpowered two-wheelercrashesinitalybyclassificationtreesandrulesdiscovery.Accident AnalysisandPrevention49(0),58–72.

Nabatilan,L.B.,2007. FactorsthatInfluenceVisualAttentionandtheirEffectson SafetyinDriving:AnEyeMovementTrackingApproach.TheLouisianaState University,USA.

Neale,V.L.,Klauer,S.G.,Knipling,R.R.,Dingus,T.A.,Holbrook,G.T.,Petersen,A.,2002. The100CarNaturalisticDrivingStudy,Phase1–ExperimentalDesign.National HighwayTrafficSafetyAdministration,DC,DOTHS809536.

Olson,R.L.,Hanowski,R.J.,Hickman,J.S.,Bocanegra,J.,2009. DriverDistractionin CommercialOperationsVehicle.FederalMotorCarrierSafetyAdministration, DC,FMCSA-RRR-09-042.

Pande,A.,Abdel-Aty,M.,2009. Marketbasketanalysisofcrashdatafromlarge jurisdictionsanditspotentialasadecisionsupporttool.SafetyScience47(1), 145–154.

Patten,C.J.D.,Kircher,A.,stlund,J.,Nilsson,L.,2004. Usingmobiletelephones: cognitiveworkloadandattentionresourceallocation.AccidentAnalysisand Prevention36(3),341–350.

Salvucci,D.D.,Liu,A.,2002. Thetimecourseofalanechange:drivercontroland eye-movementbehavior.TransportationResearchPartF:TrafficPsychologyand Behaviour5(2),123–132.

Summala,H.,Pasanen,E.,Rasanen,M.,Sievanen,J.,1996. Bicycleaccidentsand drivers’visualsearchatleftandrightturns.AccidentAnalysisandPrevention 28(2),147–153.

Törnros,J.,Bolling,A.,2006.Mobilephoneuse–effectsofconversationonmental workloadanddrivingspeedinruralandurbanenvironments.Transportation ResearchPartF:TrafficPsychologyandBehaviour9(4),298–306.

Tan,P.-N.,Steinbach,M.,Kumar,V.,2006. IntroductiontoDataMining.Pearson, Boston.

Thompson,K.R.,Johnson,A.M.,Emerson,J.L.,Dawson,J.D.,Boer,E.R.,Rizzo,M.,2012. Distracteddrivinginelderlyandmiddle-ageddrivers.AccidentAnalysisand Prevention45(0),711–717.

Underwood,G.,2007. Visualattentionandthetransitionfromnovicetoadvanced driver.Ergonomics50(8),1235–1249.

Underwood,G.,Chapman,P.,Brocklehurst,N.,Underwood,J.,Crundall,D.,2003. Visualattentionwhiledriving:sequencesofeyefixationsmadebyexperienced andnovicedrivers.Ergonomics46(6),629–646.

Underwood,G.,Crundall,D.,Chapman,P.,2002.Selectivesearchingwhiledriving: theroleofexperienceinhazarddetectionandgeneralsurveillance.Ergonomics 45(1),1–12.

VTTI, 2012. 100-Car Data, http://forums.vtti.vt.edu/index.php?/files/category/3-100-car-data/(accessed16.11.11).

Wong,J.-T,Chung,Y.-S.,Huang,S.-H.,2010. Determinantsbehindyoung motor-cyclists’ risky riding behavior. Accident Analysis and Prevention 42 (1), 275–281.

Wong,J.-T.,Huang,S.-H.,2011. Amicroscopicdriverattentionallocationmodel. AdvancesinTransportationStudiesanInternationalJournal,53–64(Special Issue).