Do companies target their webs toward the cultural

background of their customers?

Heng-Li Yang∗ and Michelle Lin∗∗

(received December 2002, revision received August 2003, accepted October 2003)

It is logical to deduce that organizations will customize their web sites to the cultural preferences of their target audience. This research aims to investigate whether organizations in reality do conform to this assumption. This research surveyed the websites of five companies that have both an English site targeted at customers in the U.S., and a Chinese site targeted at customers in Taiwan. It is evident from the survey that the sample websites tend to adopt a neutral stance when facing audience of diverse culture backgrounds. Cultural guidance might serve a better list of “Don’ts” rather than “Do’s.

Keywords: Cultural difference; Web design; Culture.

1. Introduction

As a well-known idiom goes: “when in Rome, do as the Romans do.” This saying is more important than ever in today’s global village. Many org- anizations, no matter big or small, are extending their territories to a multi- national level. When an organization attempts to reach its local audience, the local culture and custom become a crucial factor that cannot be neglected in the organization’s communication strategy.

Information technology has various applications in organizations now- adays [3,14,16]. The Internet has made the technical aspect of cross-conti- nental communication much easier. Many enterprises have web sites that target customers of various nationalities. An U.S. corporation might have web sites designed specifically for not only its U.S. customers, but also cus- tomers in Taiwan, Germany, or Korea. While today’s technology allows an organization to reach its audience in different parts of the world with its web sites, technology in itself does not guarantee the effectiveness of the web sites, which is heavily influenced by the design of the sites.

Since the emergence of the Internet, there has been vigorous discussion about how website designs may influence user perceptions [19,20]. For

∗

Corresponding author. Professor, National Cheng-Chi University, 64 Section 2, Chihnan Road, Mucha Dist., 116, Taipei, Taiwan, e-mail: yanh@mis.nccu.edu.tw

organizations with multiple sites geared towards audiences of different countries, their challenges are more than ensuring user-friendliness. For ex- ample, Ein-Dor et al. [7] reported on the importance of the economic factors in international information systems. Besides, audience of different countries has different cultural background (and therefore, mind-set) and often, pol- itical stance [1,12]. These factors are essential in the effectiveness of comm.- unication [13]. As the ultimate goal of web sites is to achieve effective com- munication, it is logical to deduce that organizations will customize their web sites to the cultural preferences of their target audience. It is the ob- jective of this research to investigate whether organizations in reality do conform to this assumption.

2. Literature Review

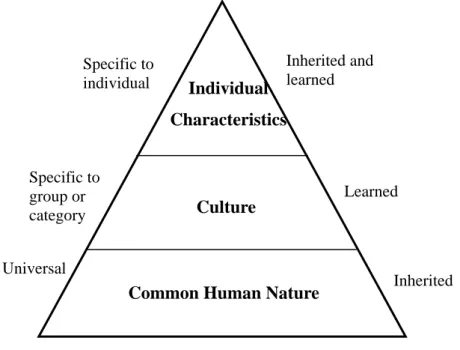

Human perceptions determine what we feel about the world around us. Similarly, user-friendliness of a web site is determined by the perceptions of the user. A person’s perceptions are subjective, personal, and mainly influ- enced by the characteristics of the specific person. As Hofstede [10] pointed out, humans’ characteristics can be classified into three major categories and each is acquired from different sources (See Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Sources of Human Characteristics

Common Human Nature

Culture

Individual

Characteristics

Specific to individual Specific to group or category Universal Inherited and learned Learned InheritedCommon human nature is at the foundation of the Figure 1. It includes universal and inherited behavioral traits [11]. Built upon the common human nature are the traits conditioned by one’s culture, namely environment. Cult- ure is a set of values, guiding beliefs, understandings, and ways of thinking that is shared by members of a group [5]. Culture is specific to a group or category. It could be defined geographically, such as a national culture, or by association, such as a group of players of Internet games or a group of elite golfers. Unique to each individual are the personal characteristics at the top of the pyramid. They are both inherited and learned from a person’s life experience. As shown by Hofstede’s research, “both cultural and individual factors could have significant influence in intercultural and international bu- siness exchanges.” [18]

Table 1 Six Cultural Dimensions and Their Associated Representative Countries

Cultural Dimension Countries with:

Large PD Malaysia and Indonesia Power Distance (PD)

Small PD U.S., Great Britain, Sweden, and Denmark Individualist U.S. and Sweden Collectivism versus

Individualism Collectivist Asian, Latin American,

Arabic-speaking countries

Masculine Japan, Austria, U.S.,

Venezuela Masculinity Versus

Femininity

Feminine Denmark, Netherlands

Strong Germany, Japan

Uncertainty Avoidance

Weak U.S., Great Britain,

Sweden, Denmark

Long-term China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Brazil

Long-Term Versus Short-Term Orientation

Short-term Germany, U.S., Britain, Pakistan

Polychronic Mediterranean, Latin

American, Arabic, and Asian nations

Polychronic Versus Monochronic Time Orientation

Monochronic North American and

European countries Sources: This study adapted the ideas from Zahedi, et al. [18].

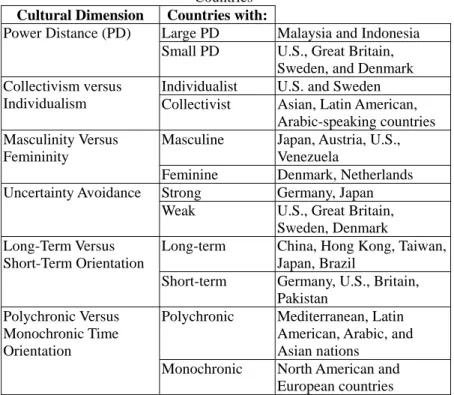

Hofstede [10] proposed five cultural dimensions that can serve as a diff- erentiation mechanism among various cultures. These cultural dimensions have been applied in organizational and, more recently, in information sy-

stem research. For example, Straub [15] applied Hofstede’s concept of un- certainty avoidance negatively affects email usage among Japanese know- ledge workers. Together with the time dimension suggested by Hall [9], there are six cultural dimensions. Zahedi, et al. [18] demonstrated each dim- ension with representative examples that are based on a national classific- ation scheme, as shown in Table 1. They further discussed the implications of the six dimensions for web design, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 Implications for Web Design Based on Cultural Dimensions

Cultural Dimension

Definition Implications for web design

Power Distance Power distance is the extent to which the less powerful members of a group or organization accept and expect the fact that power is distributed unequally.

When designing web for audi- ence of large power distance background, communication will be more effective if entities with higher power status, such as authority and expertise, are referenced. Collectivism

versus Individualism

In societies where individualism prevails, the personal ties between individuals are loose. In the collectivist societies, people, for their lifetime, are integrated into strong and cohesive groups, which protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. Consequ-ently, collectivist culture values group harmony, trust, strong extended family ties, and "we" relationships.

Communication to audience of collectivist culture would be more effective if a sense of group harmony is expressed.

Masculinity versus Femininity

The terms "masculinity" and "femininity" refer to relative terms that describe cultural character-istics that affect both individual men and women within a given culture. Masculine culture tends to have distinct social gender roles. In feminine societies, social gen-der roles overlap.

Communication with audience of masculine cultures would be more effective if masculine trait, such as success, winning, strength, assertiveness, are em- phasized.

Uncertainty Avoidance

Uncertainty voidance is the "extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by uncert-ain or unknown situations" ([10], p.113).

When communicating with people with high uncertainty avoidance, it is better to provide precise and detailed information, supported by rules and regulation; and not to

focus on novelty that deviate from the norm.

Long-Term versus Short-term Orientation

A culture with long-term orientation displays the following traits: being thrifty and sparing of resources, persevering toward slow results, respecting the dem-ands of virtue, willing subordinat-ion to a purpose, respecting social and status obligations within lim-its, adapting tradition to modern perspectives, being patient and cautious. On the other hand, cult-ures with short-term orientation tend to have the following feat-ures: expecting quick results, saving face, possessing the truth, respecting tradition, social stand-ing, and status, regardless of cost, "keeping up with the Joneses," even if it means overspending.

Web designed for users from cultures with long-term orient- ation will be more effective if they emphasize perseverance, future orientation, resources for conservation, respect for the demands of virtue, and de-emphasize truth and falsity as a strictly binary, black-and- white relationship.

Polychronic versus Monochronic Time Orientation

People of polychronic cultures like to do multiple things at a time and stress completion of tasks rather than adherence to sched-ules. In contrast, people of mono-chronic cultures do one thing at a time.

Communication to audience of polychronic orientation would be more effective if it offers high-context personal inform- ation and involves personal relationships. As well, web should focus more on a “personal touch” (as opposed to tasks or achievements for monochronic cultures). Sources: This study adapted the ideas from Zahedi, et al. [18].

From Table 2, one may think that when a company creates sites to tar- get customers in different countries, the website design should naturally abide by the rules of culture preferences. However, culture preferences, though sometimes generalizable, remain an elusive task to handle. Therefore, what some web designers do is to avoid culturally sensitive designs or ex- pressions rather than to exploit the potential benefits of culturally geared design, as the risk of offending the audience with poor culture understanding is not unlikely.

As an example, when Taiwan’s MIC (Market Intelligence Center) Re- search was building a multilingual site for Chinese and English visitors, the strategy used to cope with cultural differences was to minimize culturally

sensitive expression and be as neutral as possible [4].

Another possible reason we may not see obvious cultural differences among sites for audience of different countries is that the Internet commun- ity has formed a “cyber culture” by itself. Johnston and Johal [8] pointed out the possibility that the Internet forms a “virtual cultural region”. As one’s cultural background is shaped by the environment, the Internet has no less influence on one’s beliefs and values than the physical environment. Cyber culture is particularly evident in Internet communities where members usual- ly share not only the same interests, but also the same beliefs and values [2]. As a communication mechanism, the Internet holds great power in influenc- ing our way of thinking and, thus, cultural background. After all, a signific- ant part of our cultural understanding is gained through communication. In web sites where a unique cyber culture reigns, it is then doubtful that we will see much national cultures (as discussed previously) come into play.

The above discussion focuses on culturally geared “expression” of words. In some situations, web sites (for audience of different countries) of the same organization are not the direct translated version of one another. Yli-Jokipii [17] has conducted an investigation to the culturally geared stra- tegies of the Finnish and English websites of a Finnish company. They found that the two websites were different based on business strategies, and thus the purpose of the sites, rather than cultural variations. The Finnish website was meant for local Finnish individual buyers, so it contained detailed and itemized information and portrayed a retail-oriented strategy. On the other hand, the English website portrayed an investor-oriented strategy with the inclusion of general company profile, history, mission statement, branches abroad, etc. As illustrated, when websites of the same company target diff- erent business strategies, the goals of the websites differ and so do the subjects presented. Under such circumstances, cultural comparison is more difficult since direct comparison of language usage for the same subject mat- ter is non-existent.

3. Conceptual Framework

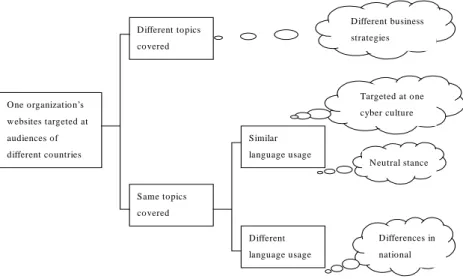

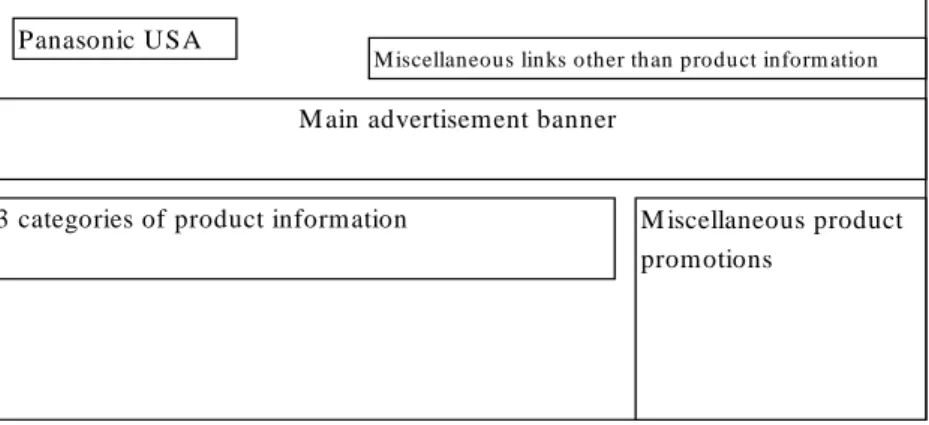

There are three major components in any web design: content, layout, and structure. Content is the usage of language and words; layout is design of a website’s appearance; and structure stands for the navigational structure of a site, represented by site map and navigational aids. When designing a culturally customized web site, the designer needs to consider all three di- mensions. In this study, the web content dimension is the main focus. However, other two dimensions may be also mentioned in order to provide

overall visual content hints. But, we will not discuss the detailed layout characteristics, such as color, font, etc. Figure 2 shows the investigation framework.

A company that has multiple web sites targeted toward audiences of different culture backgrounds may enhance the site’s effectiveness by cult- urally customize the site. However, when websites cover different topics, it is difficult to be objective in evaluating which content is culturally geared. Therefore, this framework assumes that when topics covered differ between the websites, it may be due to different business strategies the websites aim to achieve and, as a result, we will not pursue further down the “culture” path of investigation.

However, when websites cover the same/similar topics, there is room for the investigation of culture adaptation. In other words, under the variable of “content”, there are two sub-variables: “topics covered” and “language usage/way of expression”. Since the purpose of this research is to explore culturally geared language usage, the variable “topics covered” should be held constant when analyzing language usage in order to enhance objectivity.

Figure 2: Web Design from a Cultural Perspective

When language usage is similar among the websites, there are two pos- sible reasons: (1) the audience targeted by the websites belong to the same cyber culture, regardless of their nationality; (2) the organization wants to

One organization’s websites targeted at audiences of different countries Different topics covered Same topics covered Similar language usage Different language usage Targeted at one cyber culture Neutral stance Differences in national Different business strategies

avoid the prickly task of culture customization, and therefore minimizes the usage of culturally sensitive expression.

When language usage is different among the websites, this study will attempt to explain the differences using the six culture dimensions proposed by Zahedi et al. Note that this classification scheme is based on national cultures.

In sum, there are three basic culturally geared strategies for web design: customizing based on national cultures, cyber culture, or remaining at neut- ral stance by minimizing culturally sensitive expressions.

4. Survey Design

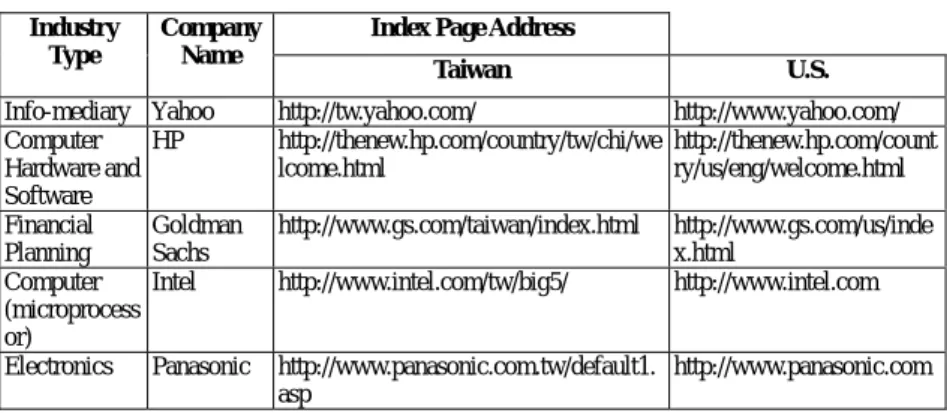

This research surveyed the websites of five companies that have both an English site targeted at customers in the U.S., and a Chinese site targeted at customers in Taiwan. Only two websites, one for U.S. and one for Taiwan, were be surveyed per company. In other words, if the company has more websites for other countries, they were not included in the study. These five websites were chosen to cover different industry products: digital products, computer hardware and software, traditional electronics, and financial prod- ucts. The survey were conducted during summer 2002.

The framework presented above will be the basis of this survey. The goal is to discover whether there are other culturally geared strategies out- side this framework.

It is possible that a website does not have a consistent “culture custom- ization” across all web pages in a site, especially when web pages are creat- ed by different designers. Therefore, only the introductory web pages (i.e., index pages) of each website were surveyed. To ensure language clarity, the term “child website” will be used to refer to the U.S. or Taiwan website of the same company.

5. Survey Results

5.1 Yahoo!

It is difficult to observe the type of language usage on two Yahoo! Web sites (U.S. and Taiwan). Because of their “portal” nature, they use mostly single-terms (e.g. Shop, Find, Science, etc.), or at best very short sentences (e.g. “your guide to health and wellness”), both of which offer little hints on culturally geared language usage.

Table 3 The Surveyed Companies

However, it can be observed that content covered on Yahoo’s child web sites (U.S. and Taiwan) are very localized. In other words, they deliver only the content that is relevant to local audience. This trait is unique among the websites surveyed because other sets of child websites share a much greater similarity in content delivered. One possible reason is the nature of their “product”. For the other four companies (HP, Intel, Panasonic, Goldman Sachs), the products they sell are very similar in U.S. and Taiwan; the “product features” stay the same. To them, the websites are meant to pro- mote their products, which are the same whether they sell to the U.S. or Taiwan. However, Yahoo’s websites are the products in themselves. They sell information, and the information needs of the U.S. and Taiwan audience are very different, hence the localization of web content.

Nonetheless, the topics (i.e. categories of information) between the U.S. and Taiwan websites are very similar. For example, under “Web Sites Direct- ory” and “Yahoo! 奇摩分類”

,

the categories are the same except that the U.S. site has “Social Science” and “Reference”, whereas the Taiwanese site has “休閒” and “生活”. Furthermore, it is evident that both site use the same template with minor modifications at each site.5.2 HP

The HP child websites are the most identical set among the five pairs surveyed. Not only do they use the same layout template, the contents are almost direct translation of one another. For example, the five main cate- gories of links are “solutions for/解決方案”, “products & services/產品資 訊”, “drivers/驅動程式”, “support/支援服務”, “buy/購買”, and “news/焦點

Index Page Address Industry

Type

Company Name

Taiwan U.S. Info-mediary Yahoo http://tw.yahoo.com/ http://www.yahoo.com/ Computer Hardware and Software HP http://thenew.hp.com/country/tw/chi/we lcome.html http://thenew.hp.com/count ry/us/eng/welcome.html Financial Planning Goldman Sachs http://www.gs.com/taiwan/index.html http://www.gs.com/us/inde x.html Computer (microprocess or)

Intel http://www.intel.com/tw/big5/ http://www.intel.com

Electronics Panasonic http://www.panasonic.com.tw/default1. asp

新聞”. Even the main advertisement is of the same theme with different graphics. On the U.S. website, the banner shows “Invention2 – a look at the combined strengths of HP Labs and Compaq Research”, whereas the Taiwanese website displays “整合完成,向前邁進 – 請按這裡,看看幕後 的成功推手”. Both are about the merge between HP and Compaq

.

The only difference between the two sites is the content in the news sections. It is evident that the content is geared toward local audience, espec- ially the Taiwanese website. For instance, one the news is a repudiation on a recent bogus promotion in the name of HP: “台灣惠普科技鄭重聲明未舉 辦 ‘SIM 卡抽獎活動,消費者切勿上當’”.

It is found that the HP websites adopt a neutral stance in terms of cult- urally designed content. Language usage is straightforward and of neutral tone. Most sentences are statements that do not attempt to provoke personal sentiments with culturally geared languages.

5.3 Goldman Sachs

What is unique about Goldman Sachs’s child websites is that the Taiw- anese website is in English. The Taiwanese websites for the other four com- panies are all in Chinese.

In terms of content, there is a high degree of similarity between these two sites. The topics covered are all the same, except that the Taiwanese web site has one additional news headline “Goldman Sachs voted best investment bank in Asia survey.” Compared with other four Taiwanese websites, this phenomenon of such a high degree of similarity in content is rare. Most websites would contain localized information in the news sections. Incident- ally, the structure of the Goldman Sachs website is centralized. Every Gold- man Sachs website is under the international parent root address of “www.gs. com”. The address for the Taiwanese site is “www.gs.com/taiwan/index. html” and the U.S. site is “www.gs.com/us/index.html”. Such structure makes one speculate whether the websites are developed centrally with little room for local customization.

5.4 Intel

Compared with the websites of HP and Goldman Sachs, the Intel web sites enjoy a greater degree of flexibility in creating localized content. The Table 4 summarizes the content not shared by both websites. Except for the items below, all other contents can be found on both websites.

Table 4 Topics Unique to the Taiwanese and the U.S. Intel Websites

Unique to Taiwanese website Unique to the U.S. website

“看看可在哪裡購買以 Intel 處理 器為基礎的個人電腦”

“Configure or build your perfect PC” All items under “焦點新聞” All items under “Other Intel

Highlights”

The category “Ads & Events Center” “Research products designed for business”

“Keep up with the latest technology trends”

A trace of masculinity can be found on both websites of Intel. For ex- ample, the Taiwanese website emphasizes “革新” while the U.S. websites focuses on “promises that Intel really can make a difference in business and your life” Both are associated with the image of masculine traits such as suc- cess and assertiveness. Instead of showing the influence of local cultures (i.e. Taiwan and the U.S.), the Intel websites display a consistent corporate cult- ure of aggressiveness and focus on success. From this example we can ob- serve a possibility that corporate culture can be so influential that, regardless of the nationality of the web designers, websites of the same organization show a consistent corporate culture, which is heavily influenced by the nat- ionality of the headquarter.

5.5 Panasonic

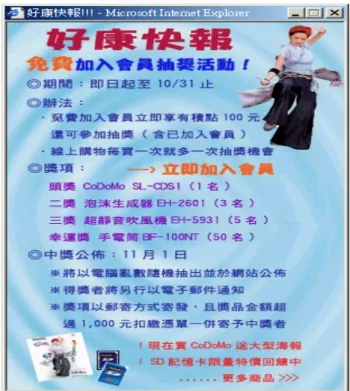

One could easily notice that the Panasonic child websites are distinctly different in terms of the general layout and structure. The difference in the general appearance is so large that they seem like websites of two unrelated companies. The content is also organized differently. Content on the U.S. website are neatly organized into different “areas” (see Figure 3). However, content on the Taiwanese website is less clearly segmented into areas (see Figure 4). As both index pages use limited amount of words, it is difficult to comment on the language usage of the sites.

Another unique feature of the Taiwanese website is the pop-up window that appears before the index page (see Figure 5). Although the pop-up page looks very “Taiwanese” at first glance, the authors would argue that the con- tent design (i.e. language usage) appeals not only to Taiwanese audience, but to universal human nature as well (see Figure 1). In other words, it uses

rewards to encourage membership application. This strategy appeals to com- mon human nature and, thus, is not a culture specific language usage.

As the Panasonic websites are so distinctive, one would be intrigued to discover the rationale behind such significant difference in design. While the other four companies in this survey are all U.S.-based, Panasonic is a Japan- ese corporation. Could it be corporate culture (which is influenced by the national culture where the company was founded)? However, there are also other variables such as industry, product, business strategy, market features, and so on. The rationale behind each web content design strategy opens the door for future investigation.

Figure 3 Content Segmentation on Panasonic USA Website

Figure 4: Panasonic Taiwanese Website

M iscellaneous links other than product inform ation

M ain advertisement banner

3 categories of product information M iscellaneous product promotions

Figure 5: Pop-up Window of the Panasonic Taiwanese Website

6. Conclusions

It is evident from the survey that the sample websites tend to adopt a neutral stance when facing audience of diverse culture backgrounds. How- ever, the fact that all websites surveyed are commercial could affect the res- ult. As the ultimate goal of businesses is profit, companies could not care less as long as they are making money. As “culture” is an elusive entity with no clear-cut definition, it might be easier to offend than to please when it comes to culturally designed content. Therefore, companies might find a list of “What not to do” more useful than a list of “What to do”. It is the spec- ulation of the authors that, because of the reason state previously, businesses rather remain neutral when communicating with audience of diverse cultural backgrounds, since they do not want to take the chance of offending any customers with badly designed cultural content. However, the conclusion might be different when we survey non-commercial websites, especially web sites for religion, literature, or cultural promotion.

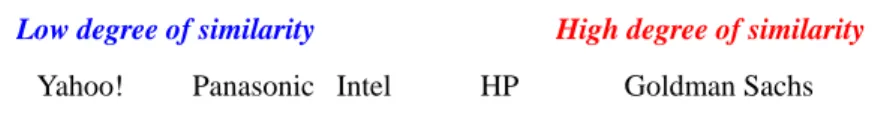

Figure 6 displays the degree of similarity between companies’ two web sites. Notice although Panasonic websites “look” most distinctive, such diff- erence is largely attributed to appearance. In terms of content, Yahoo! offers the most local information.

Yahoo! Panasonic Intel HP Goldman Sachs Figure 6 Degree of Content Similarity Between Companies’ Two Websites

There could be numerous variables behind the degree of similarity bet- ween the two sites. For example:

1. Corporate culture: the degree of freedom headquarter gives each nat- ional office in designing their own web page. Corporate culture is in- fluenced by the culture at headquarter, which is in turn influenced by the national culture where headquarter is located. In this survey, Pana- sonic happens to be the only Japanese (and non-US) company among the five companies.

2. Industry: financial services are renowned for its tight corporate con- trol. Goldman Sachs, a financial services company, has almost identical Taiwanese and U.S. websites.

3. Product: when products of the two national offices (Taiwan and the U.S.) are identical, there is little need for drastic different web design. Yahoo! sells web content, and the information needs of the U.S. and Taiwanese audiences are different. Thus, its web content is geared toward local needs. However, the products of the other four companies are not web content, and are more identical for both Taiwanese and U.S. customers, so a higher degree of similarity is observed in web content.

7. Suggestions

Culture preferences as a generalization does not cover specifics or ex- ceptions. It is like a regression line that represents the trend but may not even cross one single point on the chart. Therefore, cultural guidance might serve a better list of “Don’ts” rather than “Do’s.

The survey results indicate that a few modifications are required on the original conceptual framework proposed. First, the two branches “Different topics covered” and “Same topics covered” should be treated as a continuum

instead of two distinct choices, as every set of index pages has “some” topics in common and others different. Hence, a ratio variable (instead of the original nominal variable) should be used to represent the degree of similarity between two web pages.

Second, the ending nodes “Targeted at one cyber culture” and “Neutral stance” are not mutually exclusive. It is possible that a web site could be designed with both tactics embedded.

References

[1]. Boni, M.D., M. Prigmore. 2003. Cultural aspects of internet privacy, http://citeseer.nj.nec.com/583540.html.

[2]. Chen, L.L. 1997. Modeling the Internet as CyberOrganism: A Living Systems Framework and Investigative Methodologies for Virtual Co- operative Interaction, Ph.D. Dissertation, U. of Calgary, Alberta, Can-

ada.

[3]. Chen, C.J., B.W. Lin. 2001. A resource-based view of IT outsourcing: Knowledge sharing, communication, and coupling quality. Asia Paci-

fic Management Review 6(2) 149-173.

[4]. Chu, S.W. 1999. Challenges and strategies of developing a Chinese/ English bilingual web site. Technical Communication.

[5]. Daft, R.L. 2001. Organization Theory and Design, 7th ed. U.S.A.: Thomson Learning, 2001.

[6]. Das, T.K. 1999. The impact of net culture on mainstream societies: A global analysis, http://citeseer.nj.nec.com/205489.html.

[7]. Ein-Dor, P., E. Segev, M. Orgad. 1993. The effect of national culture on IS: Implications for international information systems. Journal of

Global Information Management 1(1) 33-43.

[8]. Johnston, K., P. Johal. 1999. The internet as a virtual cultural region: Are extant cultural classification schemes appropriate? Internet Resea-

rch: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy 9(3) 178- 186.

[9]. Hall, E.T. 1983. The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time.

Garden City, NY: Anchor.

[10]. Hofstede, G. 1997. Cultures and organizations: Software of the Mind. 2nd ed. London, U.K.: McGraw-Hill.

[11]. Lewis, R.D. 1996. When Culture Collide, London, U.K.: Nicholas Brealey.

[12]. Moon, S.B. 2003. Integrating human factors into designing user interface for digital libraries, http://citeseer.nj.nec.com/487793.html. [13]. Morris, M. 1998. Marketing in internet culture,

http://www.sun.com/960101/columns/marry-morris.960101.html. [14]. Othman, R. 2001. Antecedents and outcome of IT use: How does

HRM fit in? Asia Pacific Management Review 6(1) 91-103.

[15]. Straub, W. 1994. The effect of culture on IT diffusion: E-mail and fax in Japan and the U.S. Information Systems Research 5(1) 23-47. [16]. Yijun Li Y., R. Cao. 2001. The new development on NSS. Asia Pacific

Management Review 6(2) 197-215.

[17]. Yli-Jokipii, H. 2001. The local and the global: An exploration into the Finnish and English websites of a Finnish company. IEEE Transact-

ions on Professional Communication 44(2).

[18]. Zahedi, F.M., W.V. Van Pelt, J. Song. 2001. A conceptual framework for international web design. IEEE Transactions on Professional Com-

munication 44(2).

[19]. Zhang, P., R.V. Small, G. Von Dran, S. Barcellos. 1999. Websites that satisfy users: A theoretical framework for web user interface design and evaluation. Proceedings of the 32nd Hawaii International Confer-

ence on System Sciences.

[20]. ______, G. Von Dran, P. Blake, V. Pipithsuksunt. 2000. A comparison of the most important website features in different domains: An emp- irical study of user perceptions. Proceedings of Americas Conference