國 立 交 通 大 學

資訊管理研究所

博 士 論 文

企業導入企業資源規劃系統對供應鏈管理能力之影響

The Relationship between Benefits of ERP Systems Implementation

and Its impacts on Firm Performance of SCM

研

究 生: 蘇宜芬

指導教授:

楊 千 博士

i

企業導入企業資源規劃系統對供應鏈管理能力之影響

學生:蘇宜芬 指導教授:楊 千

國立交通大學資訊管理研究所博士班

摘要

企業所面臨的環境更複雜競爭更劇烈,已不能以單打獨鬥方式面對客戶多變的需 求。因此供應鏈設計成為企業重要的核心能力。為提升供應鏈管理能力,企業必須借重 資訊系統。因而以企業流成為導向設計的企業資源規劃系統(Enterprise resource planning, ERP) 橫掃產業界。許多組織不惜耗費巨額資金以導入企業資源規劃系統, 而企業資源規劃系統也被視為提升供應鏈管理效能不可或缺的要素。然而,導入 ERP 系 統既昂貴,也可能具風險。因此資訊經理人必須審慎評估,以有限的資源投資在正確的 資訊系統上。是否 ERP 對供應鏈管理能力的提升具有正面的影響力?我們的研究焦點因 而置於此。 本研究首先著眼於近年來相關的供應鏈管理與企業資源規劃議題:第一,對供應鏈管理 與企業資源規劃做定義;第二,回顧過去的相關文獻,提出概念性架構以闡明企業資源 規劃的效益與供應鏈管理能力,並檢視前者對後者的影響;第三,資料的蒐集以台灣資 訊科技產業為主,並透過專家深入訪談與問卷方式取得資料。架構模型以結構方程模型 作分析。研究結果得到五大企業資源規劃效益中的三大效益 – 營運、管理、與策略效 益對供應鏈管理能力具正面影響。而資訊科技與組織效益不具顯著影響效力。同時,超 過百分之八十的受訪者認為企業應該先行導入企業資源規劃系統,作為企業資訊的骨幹, 再行考量部署其他資訊系統 – 如供應鏈管理系統,較能彰顯效益。 關鍵字:企業資源規劃、供應鏈管理、企業系統、結構方程模型、調查。ii

The Relationship between Benefits of ERP Systems

Implementation and Its impacts on Firm Performance of SCM

Student: Yi-fen Su Advisor: Chyan Yang

Institute of Information Management

National Chiao Tung University

ABSTRACT

Supply chain design is becoming a core competency. The Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system is expected to be an integral component of Supply Chain Management (SCM). Installing an ERP system is, however, expensive and risky. IT managers must decide how to use their limited resources and invest in the right product. Can an ERP system directly im-prove SCM competency? Our research is therefore focusing on the relationship between ERP and SCM.

First, definitions of SCM and definitions of ERP are provided. Second, a review of past research on ERP and SCM is presented to illustrate the ERP benefits and supply chain com-petencies. A conceptual framework was proposed. The framework is featuring the ERP bene-fits and supply chain competences, and examines the impacts of the former on the latter. Third, the data collected from Taiwanese IT firms through experts interviewing and survey. The framework was evaluated using a structural equation analysis. The results confirm the opera-tional, managerial, and strategic benefits of ERP for the SCM competency, but not the IT in-frastructure and organizational benefits as significant predictors of them. Moreover, more than 80% of respondents think it necessary to first adopt an ERP system as the backbone of com-pany operations before deploying other enterprise systems (ES), such as the SCM system. Keywords: Enterprise resource planning (ERP), Supply chain management (SCM), Enter-prise system (ES), Structural equation model (SEM), Survey.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to acknowledge my thanks to all the individuals who assisted me during the process of conducting this research. Without their guidance and support this research would not be possible.

Words cannot express the gratitude I have for my advisor Prof. Chyan Yang for his tire-less support. His wisdom and guidance was greatly appreciated.

I would also like to extend my gratitude to my dissertation committee: Prof. Wei-Tzen Yang, Prof. Gwo-Hshiung Tzeng, Prof. Chi-Chun Lo, and Prof. Duen-Ren Liu. They provided me advice, guidance, and expertise, as well as kind support, until I completed this dissertation. The influences they have had on me are too great to enumerate here.

I also want to thank Professors: Prof. Po-Lung Yu and Prof. Han-Lin Li who encour-aged and advised me during my doctoral studies.

Particularly, I am thankful to my special friends Dr. Tzu-Chang Yeh and Dr. Jia-Jane Shuai for their invaluable and timely help during various stages of this dissertation.

Lastly, my deep appreciation is extended to my parents, husband, and son – for being a constant source of inspiration, comfort and love, for years of encouragement and acceptance of gender-free responsibilities at home, and for sharing my tears, sweat, laughter, and joys during the long year of doctoral study.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

摘要………i Abstract ...ii Acknowledgements ………. iii Table of Contents ……… ivList of Tables ………...vii

List of Figures ………viii

Chapter 1 Introduction ……….1

1.1 Research Background and Problems ……….…..2

1.2 Research Objectives and Defining the Problem Area ……….….5

1.3 Overview of the Research Process ……….…..7

1.4 Outline of the Dissertation ………..….8

Chapter 2 Literature Review ………..12

2.1 Supply Chain Management ………12

2.2 Competencies of SCM ………16

2.3 Enterprise Resource Planning ……….18

2.4 ERP Benefits ………...19

2.5 The Impact of ERP on SCM ………...22

Chapter 3 Research Model and Hypothesis Development ………24

3.1 Research Model ………...24

3.1.1 The constructs of SCM competencies ………..25

3.1.1.1 Operational process integration competencies of SCM ………..25

3.1.1.2 Planning and control process integration competencies of SCM ……26

3.1.1.3 Behavioral process competencies of SCM ………..27

v

3.1.2.1 The operational benefits of ERP ……….28

3.1.2.2 The managerial and organizational benefits of ERP ………...29

3.1.2.3 The strategic and IT infrastructure benefits of ERP ………30

3.2 Research Hypotheses ………...33

3.2.1 ERP benefits and the operational process of SCM ...33

3.2.2 ERP benefits and the planning and control process of SCM ………34

3.2.3 ERP benefits and the behavioral process of SCM ………36

Chapter 4 Research Instrument Development and Content Validity ………38

4.1 Stage 1 Scale Development ……….….38

4.1.1 Construct domain specification ……….38

4.1.2 Item generation and structured interview ………..39

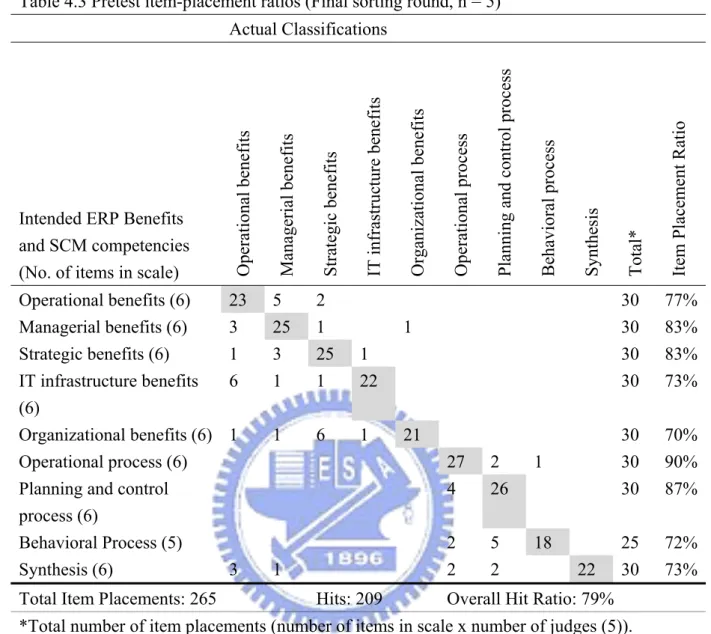

4.1.3 Measure purification ……….….41

4.1.4 Results of item purification sorting process ………..42

4.2 Stage 2 Empirical Scale Refinement and Validation ………52

4.2.1 Content validity analysis ………....52

4.2.2 Unidimensionality analysis ………52

4.2.3 Survey methods ………..53

4.2.4 The background of data collection ……….56

Chapter 5 Analysis and Results ……….59

5.1 The Measurement Model ……….….59

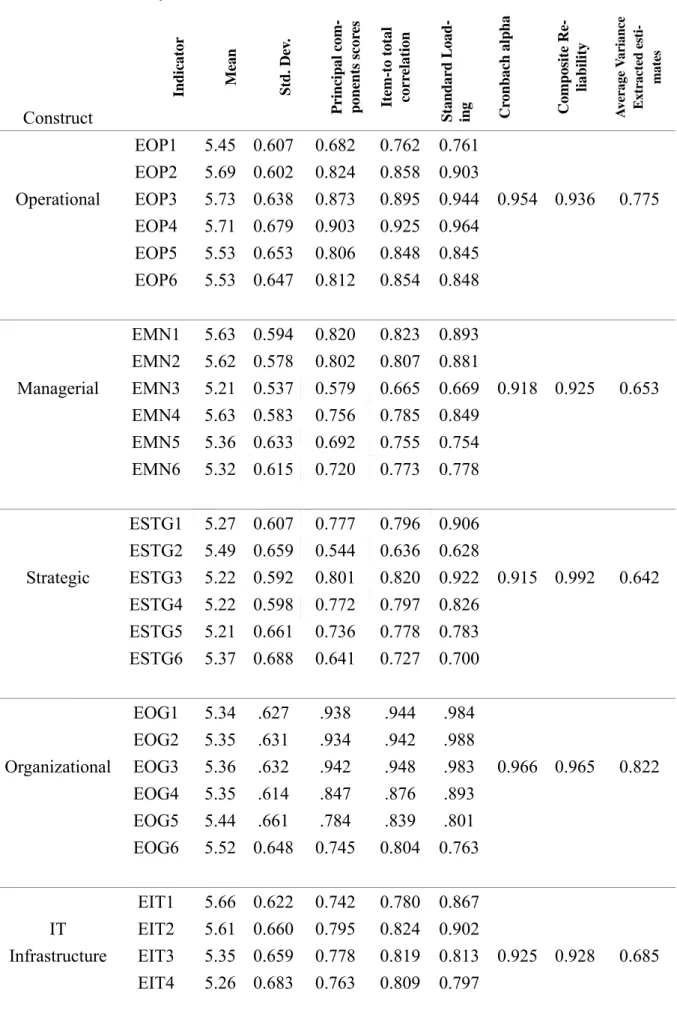

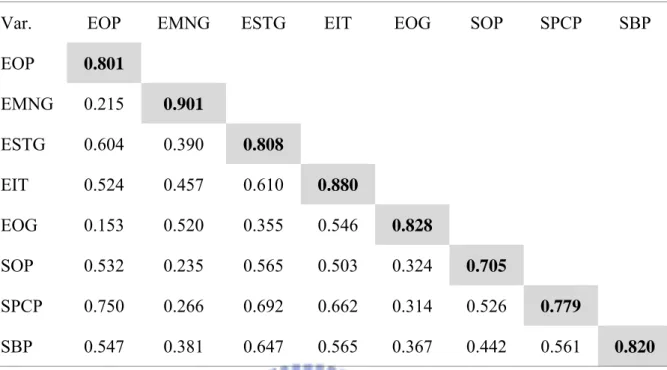

5.2 Instrument Reliability and Validity ………...65

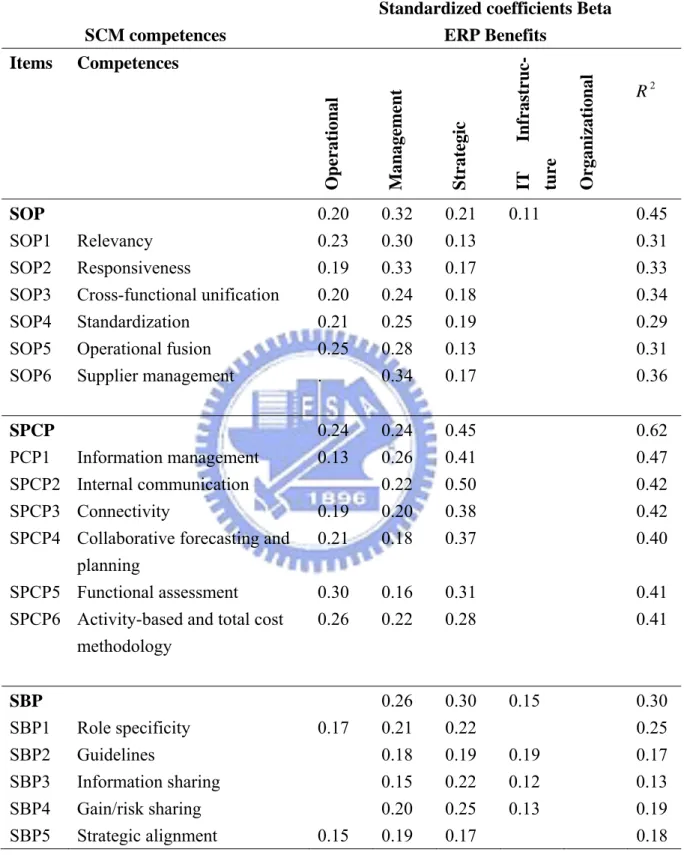

5.3 Results of Multiple Regression Analysis ……….….69

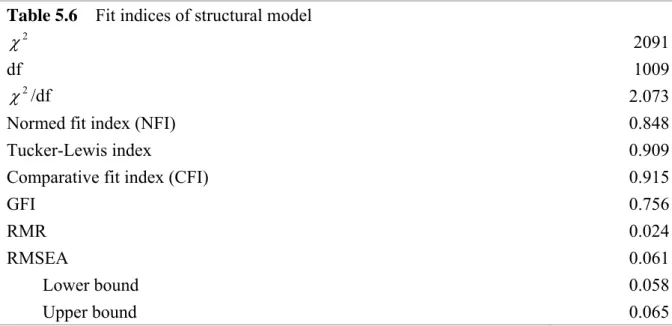

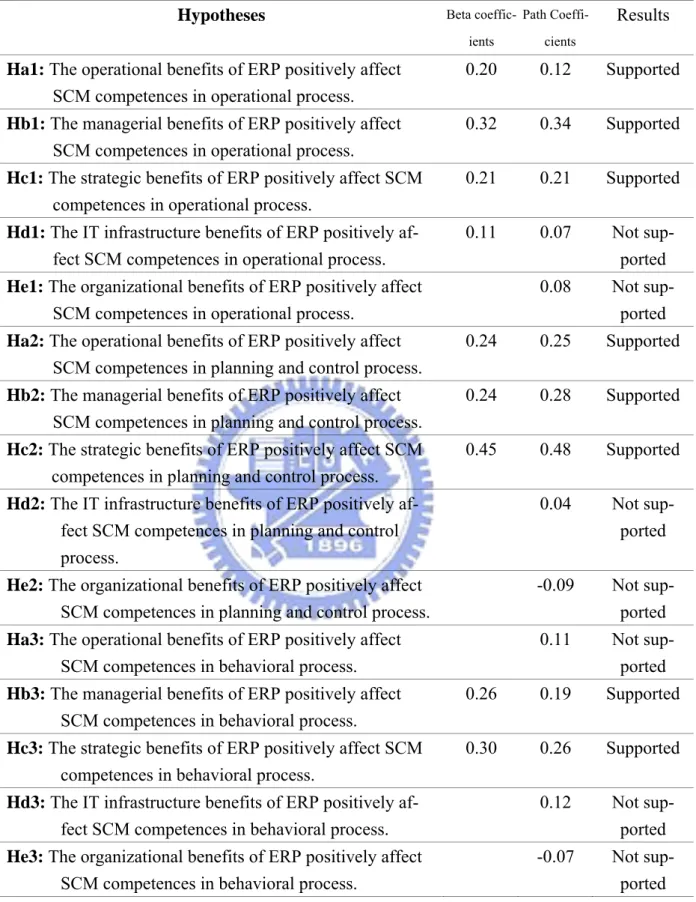

5.4 Results of the Structural Model Analysis ………..71

Chapter 6 Discussions and Implications ………...75

6.1 The Impact on the Operational Process ………75

vi

6.3 The Impact on the Behavioral Process ………76 Chapter 7 Conclusions and Remarks ………77 7.1 Conclusions ………...77 7.1.1 The operational, managerial, and strategic benefits are significant predictors for the SCM ………77 7.1.2 The IT infrastructural and organizational benefits are not significant

predic-tors of SCM ……….80 7.2 Major contributions to the academic community and its implications for practi-tioners ………..84 7.3 Limitations of the Research and Recommendations for Future Research ……..85 References ………..87 Appendix Questionnaire ……….102 Publication List ………107

vii

LIST OF TABLES

3.1 Definitions and constructs in the model ……….32

4.1 Original and final measurement scales and items: Standardized path loadings from CFA ………45

4.2 SCM competences and ERP benefits definitions ………48

4.3 Pretest item-placement ratios ………..51

4.4 Demographic characteristics of the respondents ……….55

5.1 Exploratory factor analysis loading ………62

5.2 Summary of the measurement model ……….63

5.3 Loadings of the measures ………67

5.4 Comparison of AVE and squared roots correlations ………...68

5.5 Multiple regression results ………..70

5.6 Fit indices of structural model ………72

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

1.1 Conceptual Model – Influence of ERP systems implementation on firm competencies Of SCM ………9 1.2 Dissertation process overview ………10 1.3 The domain definitions of linking ERP benefits and firm competencies of SCM ……..11

2.1 21st Century Supply chain framework ………18

3.1 The proposed conceptual model and research hypotheses ……….31 5.1 Structural Model Results ………73

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

The globalization of competition means that apart from ensuring their own successful operation, firms that hope to survive must establish highly responsive supply chains, with up-, mid-, and downstream partners. How to best improve corporate SCM capabilities in order to improve overall supply chain performance has therefore become an important issue in corpo-rate management (Fine, 1998; Park et al., 2005; Whit et al., 2005). As Kuei et al. (2002) have pointed out, SCM is a network of autonomous or semi-autonomous business entities collec-tively responsible for procurement, manufacturing and distribution activities associated with one or more families of related products. Enterprises in the supply chain are likely to increase control over their suppliers and enhance their SCM competencies by gaining power from in-formation. To meet these new challenges and the need for a competent supply chain, compa-nies around the world have invested heavily in Information Technology (IT), and take advan-tage of IT systems to radically alter the conduct of business in both domestic and global mar-kets. In particular, many firms have implemented company-wide systems called ERP systems, which are designed to integrate and optimize various business processes, such as order entry and production planning, across the entire firm (Mabert et al., 2001). This investment has also made possible the sharing of large amounts of information along the supply chain, and has enabled real-time collaboration between supply chain partners, providing organizations with forward visibility, thus improving inventory management and distribution. ERP, which allows for the transmission and processing of information necessary for synchronous decision mak-ing, can be viewed as an essential enabler of SCM activities (Akkermans et al., 2003; Hsu et al., 2007; Sanders, 2007).

2

1.1 Research Background and Problems

Early ERP systems, however, did not have the improvement of supply chain manage-ment as their objective. Their initial focus was executing and integrating internally-oriented applications that support finance, accounting, manufacturing, order entry, and human re-sources. Satisfaction of internal requirements for information integration and for solutions that will improve SCM competencies, while obviously desirable, is insufficient, and firms expect new information systems to also enable them to swiftly respond to the varied needs of their customers, to share appropriate real-time information, and to establish excellent relationships with supply chain partners. Consequently, many organizations have also addressed supply chain issues with their ERP system, in addition to implementing an integrated version of it internally (Davenport and Brooks, 2004).

When ERP systems are fully realized in a business organization, they can be expected to yield many benefits, such as reduction of cycle time, faster transactions, better financial management, the laying of the groundwork for e-commerce, linking the entire organization together seamlessly, providing instantaneous information, and making tacit knowledge expli-cit (Mabert et al., 2001; Davenport and Brooks, 2004; Shang and Seddon, 2000; Murphy and Simon, 2002; Al-Mashari et al., 2003). ERP can provide the digital nervous system and the backbone in an organization to respond swiftly to customers and suppliers (Cox et al., 2000; Mabert et al., 2001). As reported in Akkermans et al. (2003), ERP systems are widely believed to contribute to SCM in technical areas such as standardization, transparency and globaliza-tion. ERP systems are a leading tool for this purpose, and are always expected to be an integral component of SCM (Sawy et al., 1999; Nah et al., 2001; Themistocleous et al., 2002). The potential benefits of an integrated ERP system are such that many organizations are will-ing to undertake the difficult process of conversion.

3

performance, and some academic research is much more suspicious of its benefits. First of all, implementing an ERP system is costly and risky; it requires a large amount of capital, and its inflexibility makes it often difficult to implement across all departments within a large corpo-ration (Mabert et al., 2001). Some businesses have invested enormous sums of money in ERP or IT without positive results (Gupta and Kohli, 2006; Ehie and Madsen, 2005; Roach, 1991; Pentland, 1989; Strassman, 1990).

Hitt et al. (2002), on the other hand, produced multiyear, multi-firm ERP implementa-tion and financial data that shows evidence of short-run gain during implementaimplementa-tion, but a lack of post-implementation data at the time they conducted their study meant they were una-ble to estimate the long-run impact. Gattiker and Goodhue (2004) argued that high interde-pendence among organizational sub-units contributes to positive ERP-related effects because of ERPs ability to coordinate activities and facilitate information flows. When differentiation among sub-units is high, however, organizations may incur ERP-related compromise or de-sign costs. A survey by Mabert et al. (2003a) found some improvements in managers’ percep-tions of performance, but that few firms had reduced direct operational costs. In addition, Hendricks et al. (2007) observed improvements only in profitability, not in stock returns. Data for improvements in profitability is also stronger in the case of early adopters of ERP systems. Although their results are not uniformly positive across the different enterprise systems (ES, including ERP, SCM, and CRM systems), they are encouraging in the sense that despite the high implementation costs, they do not find persistent evidence of negative performance asso-ciated with ES investments.

More recent evidence has, on the contrary, demonstrated large benefits and uncovered significant productivity gains from IT investments: for example, as reported in McAfee (2002), an in-depth case study of an ERP implementation and its effects on performance at a single firm. This longitudinal research presents initial evidence of a causal link between IT adoption and subsequent improvement in operational performance measures, as well as

evi-4

dence of the timescale for these benefits. Hunton et al. (2002) experimentally tested the rela-tionship between ERP and performance by presenting 63 certified analysts at a financial ser-vices firm with the hypothetical case of a company, and comparing these analysts’ initial earning forecasts with their forecasts after they are told that the hypothetical firm has com-mitted to invest in an ERP system. The results show that the revision in earnings is positive, thereby providing supports for the hypothesis that implementation of ERP systems has a posi-tive effect on performance. Huang et al. (2007) proposed an integrated theoretical model that demonstrated that the company’s implementation of ERP has a positive effect on the process capital of its Intellectual Capital (IC); the process capital then affects the customer capital, which ultimately translates into business performance.

Many academic researchers have contributed by confirming the relationship between SCM and firm performance (Du, 2007; Hong and Jeong, 2006; Closs and Mollenkopf, 2004; Narasimhan and Kim, 2002; Byrd and Davidson, 2003; Gunasekaran et al., 2004) or by con-firming the relationship between ERP implementation and firm performance (Hendricks et al., 2007; Mabert et al., 2001, 2003a; McAfee, 2002; Hitt et al., 2002; Gupta and Kohli, 2006; Ehie and Madsen, 2005; Laframboise and Reyes, 2005; Kumar and Harms, 2004; Kalling, 2003). Moreover, determining how to integrate various ERP modules into SCM, for planning, control and execution of materials, resources and operations has recently become important (Koh et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Samaranayake and Toncich, 2007; Ho, 2007). Research focusing on the relationship between ERP benefits and SCM competencies is limited and in-conclusive (Hsu et al., 2007). Accordingly, the current research addresses this gap in the lite-rature by analyzing the ERP benefits and SCM competencies. The evidence that the Taiwa-nese IT industry has had a highly successful growth experience with SCM competencies shows that it can be documented, and lessons can be learned. This dissertation proposes a conceptual framework featuring the ERP benefits and SCM competencies, and examines the impacts of the former on the latter. It adds to our cumulative understanding of the relationship

5

of ERP systems and SCM competencies and it guides current and future efforts at decision making on selection of enterprise systems and on improvement of SCM competencies.

This dissertation presents a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to analyze the rela-tionship between ERP benefits and SCM competencies. Hypotheses derived from the key benefits of adopting ERP system and related SCM practices presented by previous authors. An empirical survey was conducted to collect data from Taiwanese IT companies listed in the Taiwan Stock Exchanges on several aspects of firm competencies and supply chain perfor-mance that adopted ERP systems and/or SCM systems. Results from the model are analyzed and implications for the model are discussed.

1.2 Research Objectives and Defining the Problem Area

Business organizations today are facing a more complex and competitive environment than ever before. Business success is no longer a matter of analyzing only the individual firm, but rather the chain of delivering and supplying organizations. Managing multiparty collabo-ration in a supply chain is a very difficult task because there are so many parties involved in the supply chain operation, each with its own resources and objectives. Member enterprises in the chain need to cooperate with their business partners in order to satisy customers’ needs and to maximize their profit. There is no single authority over all the chain members. Cooper-ation is through negotiCooper-ation rather than central management and control. The interdependence of multistage processes also requires real-time cooperation in operation and decision-making across different tasks, functional areas, and organizational boundaries in order to deal with problems and uncertainties (Jain, 2008; Whit et al., 2005). As a result, to remain successful and to be competitive, managers of organizations must use technology to improve firm and supply chain performance.

6

competitive strategy of many businesses. This strategic emphasis has made it possible for mangers to integrate information and communications technologies throughout the organiza-tion and link all business units together. Currently, a popular approach to the development of an integrated enterprise-wide system, the adoption of enterprise resource planning (ERP), is sweeping across industry (Akkermans et al., 2003). Successful implementation of ERP has been publicized by such software vendors as SAP, J. D. Edward, Baan, and Oracle. Consi-dered more broadly, an ERP system is an example of enterprise systems, other fast-growing developments – supply chain management software and e-commerce – also have intra- or in-ter-organizational integration at their core. Two research questions follow from these consid-erations:

1. Can an ERP system directly improve SCM competencies?

2. Is it necessary to first adopt an ERP system as the backbone of company operations before deploying other enterprise systems (ES), such as the SCM system?

The definition of ERP used in the present research is as stated by Wallace and Kremzar (2001): “An enterprise-wide set of management tools that balances demand and supply, con-taining the ability to link customers and suppliers into a complete supply chain, employing proven business processes for decision making, and providing high degrees of cross-functional integration among sales, marketing, manufacturing, operations, logistics, purchasing, finance, new product development, and human resources, thereby enabling people to run their business with high levels of customer service and productivity, and simultaneous-ly lower costs and inventories; and providing the foundation for effective e-commerce.”

The term “supply chain” is used in the present research in the spirit of the value chain concept. A supply chain is a dynamic process and involves the constant flow of information, materials, and funds across multiple functional areas both within and between chain members (Jain et al., 2008). Such a holistic approach is consistent with the integrated way today’s glob-al business managers are planning and controlling the flow of goods and services to the

mar-7

ketplace.

1.3 Overview of the Research Process

Figure 1.1 shows the conceptual model based on the discussion in this chapter. The model encompasses and relies on two areas: benefits of ERP systems implementation as re-ferred to in the classification of ERP benefits, and SCM competencies.

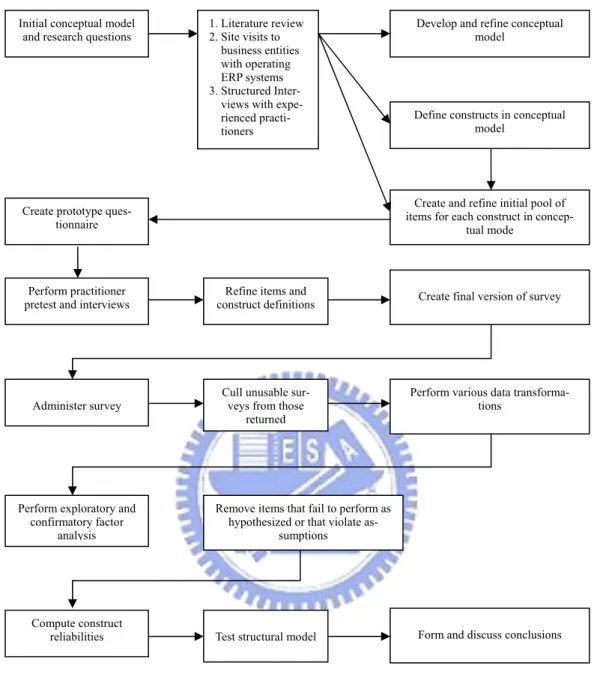

Figure 1.2 presents an overview of the research process. The researcher’s ultimate ob-jective was testing hypotheses based on the model (Figure 1.1). Furthermore, the investigator undertook several site visits to business entities with operating ERP systems.

Based on the site visits to business entities with operating ERP systems, structured in-terviews with experienced practitioners and a review of the relevant literature, the researcher elaborated on the model in Figure 1.1 and Figure 1.3, eventually producing the model pre-sented in Chapter 3. Conceptual definitions of the variables in the model were developed based on the literature and the interviewing of experts. Based on this model, the researcher developed specific, testable hypotheses.

Next, the domain of the relevant construct is initially specified, and the items are sub-sequently developed based on the conceptual definition. Based on the constructs, we develop a questionnaire draft. The preliminary instrument is pilot tested and reviewed by IT managers from five Taiwanese IT firms, doctoral students and EMBA students. The items are modified following a pre-test of the survey instrument with a sample of five experts, using the same data collection methods, following procedures recommended by Churchill (1997). The pre-tests indicate that the questionnaire is deemed appropriate to examine the relationship between ERP and SCM in Taiwanese IT firms.

Although the plant is the unit of analysis in the model, the survey respondents are the selected chief information officers, IT personnel, or operating managers who have

imple-8

mented ERP systems or have been responsible for SCM. Since the research questions involve understanding the effects of ERP systems, the domain is restricted to plants that are actually running ERP systems. In order to elicit completed questionnaires from individuals meeting these criteria, the researcher administered the questionnaire using one of two forms: e-mail or regular mail. Survey data is collected from a sample of Taiwanese IT companies listed in the Taiwan Stock Exchanges (TSE), mainly on electronics manufacturers (including: PC systems, peripherals, communications, consumer electronics, and computer components) and semi-conductors-related manufacturers (including: foundry, IC design, packaging and testing, mask, and equipment/material provider), and screened according to whether they have operational ERP systems.

After administering the survey, the researcher evaluated the measurement properties of the instrument. The researcher performed exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, checked for violations of certain assumptions and calculated construct reliabilities. Based on these analyses the investigator purified the instrument by deleting problematic items and making other changes to the measurement model. Finally, the researcher used the survey data to evaluate the propositions in the research model.

1.4 Outline of the Dissertation

Chapter 1 defined and described ERP and SCM. It described the problem area; and it presented the research questions, an overview of the research process and the importance of the research. Chapter 2 presents relevant literature on ERP benefits and firm competencies of SCM and other important concepts. Chapter 3 presents the model, defines the constructs, dis-cusses their operationalizations and states the hypotheses. Chapter 4 uses the data to establish the instrument’s measurement validity. Chapter 5 analyses the model measurement. Chapter 6 discusses the findings and implications. Chapter 7 makes conclusions and remarks. It also

9

presents the major contributions to the academic community and its implications practitioners and the limitations of the work and suggested future research directions.

Benefits of ERP imple-mentation Competencies of SCM Improved firm performance on

Figure 1.1 Conceptual Model – Influence of ERP systems im-plementation on firm competencies of SCM

10

Initial conceptual model and research questions

1. Literature review 2. Site visits to business entities with operating ERP systems 3. Structured

Inter-views with expe-rienced practi-tioners

Develop and refine conceptual model

Define constructs in conceptual model

Create and refine initial pool of items for each construct in

concep-tual mode

Create final version of survey Create prototype

ques-tionnaire

Perform practitioner

pretest and interviews construct definitions Refine items and

Cull unusable sur-veys from those

returned

Test structural model Administer survey

Perform exploratory and confirmatory factor

analysis

Compute construct reliabilities

Remove items that fail to perform as hypothesized or that violate

as-sumptions

Form and discuss conclusions Perform various data

transforma-tions

11

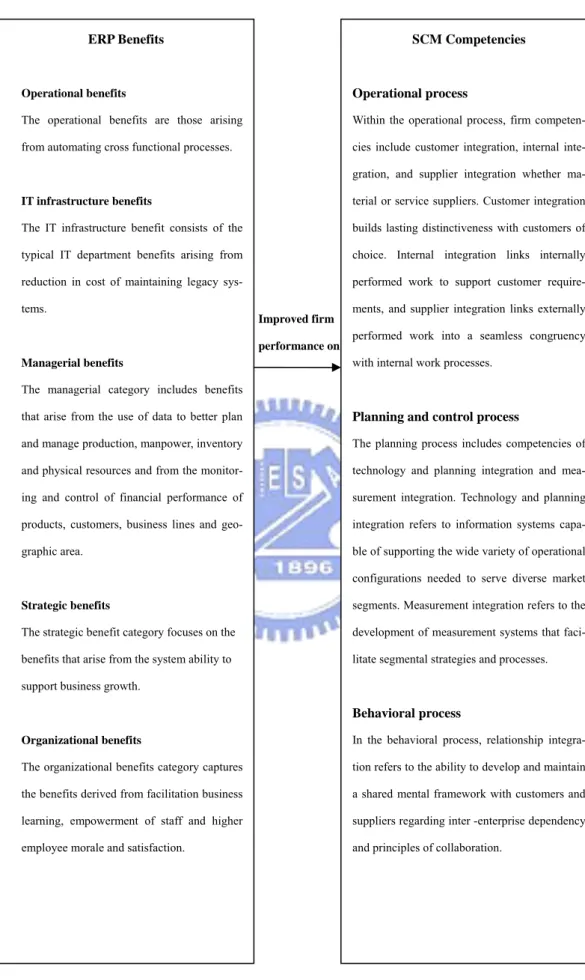

Figure 1.3 The domain definitions of linking ERP benefits and firm competencies of SCM.

ERP Benefits

Operational benefits

The operational benefits are those arising from automating cross functional processes.

IT infrastructure benefits

The IT infrastructure benefit consists of the

typical IT department benefits arising from reduction in cost of maintaining legacy sys-tems.

Managerial benefits

The managerial category includes benefits

that arise from the use of data to better plan and manage production, manpower, inventory and physical resources and from the monitor-ing and control of financial performance of products, customers, business lines and geo-graphic area.

Strategic benefits

The strategic benefit category focuses on the

benefits that arise from the system ability to support business growth.

Organizational benefits

The organizational benefits category captures

the benefits derived from facilitation business learning, empowerment of staff and higher employee morale and satisfaction.

SCM Competencies

Operational process

Within the operational process, firm competen-cies include customer integration, internal inte-gration, and supplier integration whether ma-terial or service suppliers. Customer integration builds lasting distinctiveness with customers of choice. Internal integration links internally performed work to support customer require-ments, and supplier integration links externally performed work into a seamless congruency with internal work processes.

Planning and control process

The planning process includes competencies of technology and planning integration and mea-surement integration. Technology and planning integration refers to information systems capa-ble of supporting the wide variety of operational configurations needed to serve diverse market segments. Measurement integration refers to the development of measurement systems that faci-litate segmental strategies and processes.

Behavioral process

In the behavioral process, relationship integra-tion refers to the ability to develop and maintain a shared mental framework with customers and suppliers regarding inter -enterprise dependency and principles of collaboration.

Improved firm performance on

12

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

Research into the relationships among ERP, SCM and firm performance has increa-singly applied theories and concepts from the strategic literature. The resource based view (RBV) of the firm is a particularly appropriate theoretical framework for studying the perfor-mance implications of SCM and ERP (Zsidisin et al., 2003; Sinkovics and Roath, 2004; Kal-ling, 2003; Tarafdar and Gordon, 2007). It complements traditional industrial organizational theory by recognizing the competitive value of resources/capabilities/competencies, and how they combine with and influence strategies pursued by a firm. Within a supply chain, re-sources and strategies include those that reflect inter-firm activity. We therefore suggest that ERP benefits play an important role in enhancing SCM competencies. Once a firm has adopted its ERP system and infrastructure, it is in a position to leverage relationships within the supply chain (Kovacs and Paganelli, 2003; Davenport and Brooks, 2004; Akyuz and Re-han, 2008). It follows that how a firm adopts an ERP system should be considered simulta-neously with consideration of enhancing its SCM competencies. Drawing from the literature, we posit that the benefits of adopting an ERP system include that it is an enabler and antece-dent of creating SCM competencies of enterprise. The related literature and conceptual framework underlying the study are presented next.

2.1 Supply Chain Management

Supply chain management (SCM) is a 21st century paradigm of IT infrastructure. It fo-cuses on globalization and information management tools that integrate procurement, opera-tions, and logistics from raw materials to customer satisfaction. Further, it increases

manufac-13

turing flexibility, transportation speed, and information availability, as well as management complexity. In recognition of this potential, practicing managers and academic researchers have realized that SCM has been a major component of competitive strategy to enhance orga-nizational productivity and profitability (Kovacs and Paganelli, 2003; Themistocleous et al., 2004; Akyuz and Rehan, 2008).

Not everyone, however, means the same thing by the term “supply chain management.” SCM has evolved from the field of logistics. Its development was initially along the lines of physical distribution and transportation (Lamming, 1996). The term “supply chain manage-ment” first appeared in 1982. Around 1990, academics first described SCM from a theoretical point of view to clarify the difference from more traditional approaches and names, to man-aging material flow and the associated information flow (Cooper et al., 1997). Cooper et al. (1997) provide a valuable review of 13 early SCM definitions: a solid argument that SCM and logistics are not identical. The term supply chain management has grown in popularity over the past two decades, with much research being done on the topic.

The Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) (2004) (formerly The council of Logistics Management (CLM)), a leading professional organization promoting SCM practice, education, and development, defines SCM as: “SCM encompasses the plan-ning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion, and all logistics management activities, including coordination and collaboration with suppliers, intermediaries, third-party service providers, and customers”. In essence, supply chain man-agement integrates supply and demand manman-agement within and across companies. CSCMP emphasizes that SCM encompasses the management of supply and demand, sourcing of raw materials and parts, manufacturing and assembly, warehousing and inventory tracking, order entry and order management, and distribution and delivery to the customer.

Several authors have defined supply chain management. Christopher (1998) and Sim-chi-Levi et al. (2000) define supply chain management as “the integration of key business

14

processes among a network of interdependent suppliers, manufacturers, distribution centers, and retailers in order to improve the flow of goods, services, and information from original suppliers to final customers, with the objectives of reducing system-wide costs while main-taining required service levels” (as cited in Stapleton et al., 2006, p. 108). The Global Supply Chain Forum (GSCF) defines supply chain management as “the integration of key business processes from end user through original suppliers, that provides products, services, and in-formation that adds value for customers and other stakeholders” (as cited in Lambert et al., 1998, p.1).

SCM concerns the integrated and process-oriented approach to the design, management and control of the supply chain, with the aim of producing value for the end customer, by both improving customer service and lowering cost (Bowersox and Closs, 1996; Giannoccaro and Pontrandolfo, 2002).

According to Li et al. (2006) the dual purpose of SCM is to improve the performance of an individual organization as well as that of the entire supply chain. CLM definitions clearly establish that SCM is more broadly conceived than merely “logistics outside the firm” (Lam-bert, 2004; Lambert et al., 1998). Recent research supports this conception, portraying SCM as a strategic level concept (Stank et al., 2005). Mentzer et al. (2001) consider SCM as a sys-temic, strategic coordination of business functions within an organization and between organ-izations within the supply chain, for improving the long-term performance of individual companies and the supply chain as a whole. The emphasis of each of these definitions is on the objective of SCM to create a distinctive advantage by maximizing the total value of prod-ucts and services (Stank et al., 2005).

Furthermore, Lummus and Vokurka (1999) add that SCM links all the departments within an organization as well as all its trading partners. There is mutual collaboration and companies work together to make the whole supply chain competitive. Information technolo-gy is widely used to share information and generate demand forecasts. The underlying idea in

15

SCM is that the entire process must be viewed as a single system. The core competencies of individual organizations are determined and are cashed on, to create enhanced competitive advantage for the supply chain.

By the 1990s, firms recognized the necessity of collaboration with suppliers and cus-tomers in order to create superior customer value. This movement titled supply chain man-agement or value chain manman-agement shifted a company’s focus from within an enterprise to managing across firm boundaries.

Deloitte Consulting survey reported that only 2% of North American manufacturers ranked their supply chains as world class although 91% of them ranked SCM as important to their firms’s success (Thomas, 1999). Thus, while it is clear that SCM is important to organi-zations, effective management of the supply chain does not appear to have been realized.

Bowersox and Closs (1996) argued that to be full effective in today’s competitive envi-ronment, firms must expand their integrated behavior to incorporate customers and suppliers. This extension of integrated behaviors, through external integration, is referred to by Bower-sox and Closs (1996) as supply chain management. In this contex, the philosophy of SCM turns into the implementation of supply chain management: a set of activities that carries out the philosophy.

SCM has been receiving increased attention from all fronts, namely academicians, consultants, and business managers (Tan et al., 2002; Croom et al., 2000; Van Hoek, 1998) since the early 1990s. Organizations have recognized that SCM is the key to building sus-tainable competitive edge (Jones, 1998) in the 21st century. SCM has been widely talked about in prior literature from various viewpoints (Croom et al., 2000) such as purchasing, logis-tics/distribution/transportation, operations and manufacturing management, organizational behavior, and management information systems. Industrial organization and transaction cost analysis (Ellram, 1990; Williamson, 1975), resourced based and resource-dependency theory (Rungtusanatham et al., 2003), competitive strategy (Porter, 1985), and social-political

pers-16

pective (Stern and Reve, 1980) are some of the aspects of SCM that have been discussed in past literature.

Generally, SCM has three levels. Some have restricted its meaning to apply to only the “relational” activities between a buyer and seller (Ellram, 1991). A second use includes all “upstream” suppliers of a firm. Yet a third takes a “value chain” approach, in which all activi-ties required to bring a product to the marketplace are considered part of the supply chain. Manufacturing and distribution functions are thus included as part of the flow of goods and services in the chain (Davenport and Brooks, 2004; Kovacs and Paganelli, 2003; Dobler and Burt, 1996; Lee and Billington, 1993).

The term “supply chain” is used in the present research in the spirit of the value chain concept. A supply chain is a dynamic process and involves the constant flow of information, materials, and funds across multiple functional areas both within and between chain members (Jain et al., 2008). Such a holistic approach is consistent with the integrated way today’s glob-al business managers are planning and controlling the flow of goods and services to the mar-ketplace.

2.2 Competencies of SCM

The literature on SCM is quite vast and dispersed across many areas, such as purchas-ing and supply, logistics and transportation, marketpurchas-ing, organizational dynamics, information management, strategic management, and operations management. In recent years, supply chain design and its competencies and performance have received much attention from re-searchers and practitioners. To properly conduct research into constructing the SCM compe-tencies, we need to survey the literature on the subject of competency itself, and on SCM competencies and on SCM measures.

17

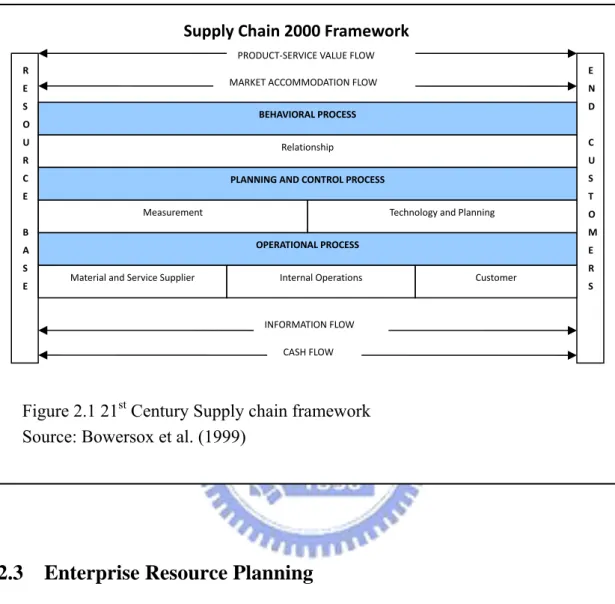

on certain capabilities consistent with its strategy, and the firm’s most important capabilities are called competencies (Barney, 1991). Accordingly, competencies emphasize technological and production expertise at a specific point along the value chain (Stalk and Shulman, 1992; Vickery et al., 1993; Cleveland et al., 1989). Bowersox et al. (1999) identified that a compe-tency reflects the synthesis of selected logistical capabilities into a logically coherent and manageable set of circumstances sufficient to gain and maintain supply chain collaborations. Closs and Mollenkopf (2004) proposed a framework that identifies six firm competencies critical for SCM and is based on the work of Bowersox et al. in 1999. Each competency is composed of multiple underlying capabilities, which guide philosophies and processes to complete specific logistics and supply chain activities and to overcome obstacles that under-mine both internal and external integration of value-added supply chain operations. The com-petencies leading to high supply chain performance can be grouped into: customer integration, internal integration, material and service supplier integration, technology and planning inte-gration, measurement inteinte-gration, and relationship integration (see Figure 1). Furthermore, Closs and Mollenkopf (2004) developed a measurement model that considers both firm and supply chain performance using 13 logistics and supply chain variables representing five key performance areas, including: customer service, cost management, quality, productivity, and asset management. Gunasekaran et al. (2004) suggested a framework for measuring the per-formance of a supply chain that consisted of three levels: strategic, tactical, and operational. Park et al. (2005) proposed a framework for the balanced supply chain scorecard (BSCS) that considers the literature on the BSC and SCM, SCM solutions, and product characteristics. The framework shows the objectives in four perspectives of the BSCS: financial perspective, cus-tomer perspective, business process perspective, and learning and growth perspective.

In the literature survey we identified the SCM competencies and, referring mainly to the framework of Bowersox et al. (1999) (see Figure 2.1), we analyzed the impact of ERP benefits on the SCM competency, and grouped the items into three constructs; and from that

18

literature we selected 20 items that are proposed as the content of SCM competencies (see Ta-ble 1). These constructs are: operational, planning and control, and behavioral process.

2.3 Enterprise Resource Planning

Different researchers have suggested different ways of defining ERP: that is, from a business, technical or functional perspective. One way of looking at ERP is as a combination of business processes and information technology. Davenport and Brooks (2004) proposed that implementing ERP systems brings many benefits to the organization, including reduction of cycle time, improving information flow, rapid generation of financial information, promo-tion of E-business, and assistance in development of new organizapromo-tional strategies. From a technical perspective, ERP was designed to overcome the operational problems that compa-nies experienced with earlier information systems. Bendoly and Schoenherr (2005) maintains

R E S O U R C E B A S E E N D C U S T O M E R S INFORMATION FLOW

Material and Service Supplier Internal Operations Customer OPERATIONAL PROCESS Measurement Technology and Planning Relationship PLANNING AND CONTROL PROCESS MARKET ACCOMMODATION FLOW BEHAVIORAL PROCESS CASH FLOW PRODUCT‐SERVICE VALUE FLOW Supply Chain 2000 Framework

Figure 2.1 21st Century Supply chain framework Source: Bowersox et al. (1999)

19

that ERP systems should not be looked at simply as tools that have a fixed and measurable output, but rather as comprising a technological infrastructure designed to support the capa-bility of all other tools and processes used by a firm. Functionally, an ERP system primarily supports the management and administration of the deployment of resources within a single organization. One significant feature of an ERP system is that core corporate activities, such as manufacturing, human resources, finance, and supply chain management, are automated, and are improved considerably by incorporating best practices, so as to facilitate greater ma-nagerial control, speedy decision making and huge reduction of business operational cost. The definition of ERP used in the present research is as stated by Wallace and Kremzar (2001): “An enterprise-wide set of management tools that balances demand and supply, con-taining the ability to link customers and suppliers into a complete supply chain, employing proven business processes for decision making, and providing high degrees of cross-functional integration among sales, marketing, manufacturing, operations, logistics, purchasing, finance, new product development, and human resources, thereby enabling people to run their business with high levels of customer service and productivity, and simultaneous-ly lower costs and inventories; and providing the foundation for effective e-commerce.”

2.4 ERP Benefits

Many firms install ERP systems to improve the flow of information across sub-units (Kalling, 2003). Data standards eliminate the burden of reconciling or translating information that is inconsistently defined across two or more sub-units. Data standards also do away with the potential for translation or reconciliation errors as well as ambiguity about a field’s true meaning (Wade and Hulland, 2004). The integration provided by ERP also reduces the ad-ministrative costs of sharing information, since many manual activities involved with keying and translating information from one system to another are eliminated. Finally, since the

sin-20

gle database makes data universally available as it is updated, ERP improves the timeliness of information. Enhancing this flow enables the centralization of administrative activities, such as payroll and accounting. Furthermore, it allows better operational coordination, such as im-proving material flows among plants or information flows from sales offices to plants. ERP can also enhance centralized decision-making at the divisional or corporate level as informa-tion from various sub-units is centralized and standardized in a timely fashion (Davenport and Brooks, 2004). Because it allows better coordination, ERP is sometimes credited with foster-ing an inter-functional process approach to business, rather than a functionally oriented one. Many firms also install ERP systems to replace existing IT infrastructure as well as to reduce maintenance costs and the costs of future IT improvements. With ERP systems the vendor develops and maintains the software and thus spreads the costs of doing so among numerous customers.

For years organizations have striven to realize the benefits of ERP, ES and IT invest-ments. Integrated ERP systems affect all aspects of a business (Kalling, 2003; Hong and Kim, 2002). Dhillon (2005) claimed that real benefits reside not within the IT domain but, rather, in the changes in the organizational activities that the IT system has enabled.

Several researchers have classified the types of ERP benefits, and have indicated that some approaches may be appropriate techniques for evaluating the performance or benefits of ERP systems. Irani and Love (2001) proposed a framework for meeting the challenges asso-ciated with categorizing benefits that is based on the work of Harris (1996). In a case study of an MRPII investment, it was observed that as one moves from strategically oriented IS projects through tactical to operationally oriented projects, the benefits accrued go from those that are generally intangible and non-quantitative in nature to more tangible and quantitative ones for strategic, tactical and operational benefits. The benefits of ERP systems include streamlined business processes, improved planning, improved decision making, and reduction of inventories.

21

Mabert et al. (2000) surveyed about 500 business executives, and revealed the follow-ing performance outcomes of ERP: quickened response time, increased interaction across the enterprise, improved order management, improved customer interaction, improved on-time delivery, improved supplier interaction, lowered inventory levels, improved cash management, and reduced direct operating costs. Stratman and Roth (2002), using 36 measures, defined eight theoretical ERP competency constructs. They posited a portfolio of managerial, technic-al and organizationtechnic-al skills and expertise as necessary antecedents to improving business function once an ERP system has become operational and functionally stable. They argued that a firm’s ERP competency must be used effectively in order to truly harness the capabili-ties of an ERP system for competitive advantage. Vemuri and Shailendra (2006) developed a set of initial measurement items for each ERP competency. Shang and Seddon (2000) classi-fied the different types of ERP benefits into five groups as follows: IT infrastructure, opera-tional, managerial, strategic and organizational benefits. The IT infrastructure category con-sists of the typical IT department benefits arising from reduction in cost of maintaining legacy systems. It is an indication of an organization’s competency in matching IT capabilities with the changing, cross-functional business requirements of the enterprise. The operational bene-fits are those that arise from automating cross-functional processes. They encompass both ef-ficiency-based and effectiveness-based performance improvements in order to capture the en-terprise-wide business benefits. The managerial category includes benefits that arise from the use of data to better plan and manage production, manpower, inventory and physical re-sources and from the monitoring and control of the financial performance of products, cus-tomers, business lines and the geographic area. The strategic benefit category focuses on the benefits that arise from the system’s ability to support business growth. Rapidly changing business needs may require operations strategy planners to continually evaluate cross-functional business goals, and redefine the information systems’ capabilities. The stra-tegic benefits of ERP can support these goals. The organizational benefits category captures

22

the benefits derived from facilitating business learning, empowerment of staff and higher em-ployee morale and satisfaction. Those studies have addressed the classification and content of ERP benefits. On the basis of the literature review presented above, we finally developed a framework consisting of five constructs and 32 measures.

In summary, as seen from the previous literature review of the different classification of ERP benefits, they revolve around business process, IT infrastructure or technical items, and strategic perspective. Stratman and Roth (2002) conceptual model of ERP competence can serve as a useful framework for evaluating the benefits of ERP systems. However, this framework does not link the competence to managerial and IT infrastructure competence as recommended by Harris (1996) and Shang and Seddon (2000). Both B’urca et al. (2005) and Biehl (2005) benefits categories also discussed less about strategic. Davenport and Brooks (2004) that there are different types of benefits from ERP system and some are likely to arise earlier than others. However, this research is interested in the relationship between benefits of ERP systems implementation and its impacts on firm competencies of SCM. We believe that to integrate the categories of benefits from Harris (1996) and Shang and Seddon (2000) might be the most appropriate technique for evaluating the benefits of ERP system. Since they em-phasized the importance of gathering information from all employment levels to evaluate the benefits gained from ERP systems. This integrated classification of benefits may help to ex-amine the relationship with firm competencies of SCM. It is mainly based on the model of Shang and Seddon (2000) and Harris (1996), and merges the benefits and measures we have proposed.

2.5 The Impact of ERP on SCM

In the past decade, nearly all literature on ERP has focused on reasons for implementa-tion and on the challenges of the implementaimplementa-tion project itself. Several distinct research

23

streams on ERP are observed in the recent literature. Several studies have demonstrated a re-lationship between ERP benefits and SCM: for example, Akkermans et al. (2003). Although the initial focus of ERP was “within the organization,” many organizations have addressed supply chain challenges with their ERP systems (Davenport and Brooks, 2004).

Although there is no analytical framework for measuring the impacts of ERP systems on SCM competencies, Byrd and Davidson (2003) have examined how the antecedents, IT department technical quality, IT plan utilization, and top management of IT positively affected IT impact on the supply chain. Wade and Hulland (2004) provide an overview of the literature on IT-related resources and their impact on firm strategy and performance, where IT covers all of the information systems, including ERP systems. Akkermans et al. (2003) studied the fu-ture impact of ERP systems on SCM. Their panel experts saw only a modest role for ERP in improving future supply chain effectiveness, and a clear risk of ERP actually limiting progress in SCM. Moreover, they identified key limitations of current ERP systems in providing effec-tive SCM support. The problem is that the first generation of ERP products has been designed to integrate the various operations of an individual firm, whereas in modern SCM, the unit of analysis has become a network of organizations, making these ERP products inadequate in the new economy. There is a new generation of ERP, however. ERP II extends business processes, opens application architectures, provides vertical-specific functionality, and is capable of supporting global enterprise processing requirements (Zrimsek, 2003). On the basis of the li-terature review presented above, we believe that the relationship between ERP and SCM sug-gested by the above-mentioned authors may be useful in the development of our research model and hypotheses.

24

CHAPTER 3

RESEARCH MODEL AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

When understanding the phenomenon of an ERP system adoption and SCM, it is help-ful to have a framework within which to work and from which testable hypotheses can be drawn. A theoretical framework enables predictions to be made about the likely outcome of the relationship between ERP adoption and SCM competencies. It enables observed business behavior to be evaluated and therefore provides better explanations of the motivations form the implementation of ERP systems and its impact on firm competencies of SCM.

3.1 Research Model

The research model is shown in Figure 3.1. The definitions of various constructs in it are summarized in Table 3.1. In this study, the authors base the research model on selected literature on ERP and on SCM. As discussed earlier, although some researchers have given their attention to the contribution of ERP systems to supply chain coordination, the goal of this research is to examine in more detail ERP benefits’ impact on SCM competency. Thus, this research model encompasses and relies on two areas: ERP benefits as referred to in the classification of ERP benefits, in Shang and Seddon (2000), and SCM competencies, based on the 21st Century Logistics framework as extended by Bowersox et al. (1999). The model in-cludes five constructs for ERP benefits, namely: operational, managerial, strategic, IT infra-structure, and organizational benefits, and three constructs for SCM competencies, namely: operational, planning and control, and behavioral processes. Based on Shang and Seddon’s (2000) classification of ERP benefits, Stratman and Roth’s (2002) competencies of ERP, and Vemuri and Shailendra’s (2006) measurement items, we conclude and hypothesize that ERP

25

benefits are antecedents to improving SCM competencies after an ERP system is operational and functionally stable. Therefore, this model investigates the relationships between the bene-fits of ERP adoption and SCM competencies. A more detailed description of SCM competen-cies and ERP benefits follows.

3.1.1 The constructs of SCM competencies

To improve firm performance, a firm needs to enhance its competences in SCM. The 21st Century Logistics framework identifies three categories of firm competences as critical for logistics and supply chain management (Figure 2.1). Each competence is composed of multiple underlying capabilities, which guide philosophies and processes to complete specific logistics and supply chain activities. Based on this framework and suggestions from experts who have recently gone or are currently going through ERP systems implementations or being responsible for SCM in Taiwanese IT industry, we identify the firm competences that may be impacted by ERP benefits and may lead to high supply chain performance and group them into three constructs. These are operational process integration, planning and control process integration, and behavioral process integration.

3.1.1.1 Operational process integration competencies of SCM

As Bowersox et al. (1999) and Closs and Mollenkopf (2004) defined in the 21st Century Logistics framework, operations involve the processes that facilitate order fulfillment and replenishment across the supply chain. In the operational context, integration is essential in-ternally as well as with customers and suppliers. Customer integration builds on the philoso-phies and activities that develop customer intimacy and is the competency that builds lasting competitive advantage. Internal integration focuses on the joint activities and processes within a firm that coordinates functions related to procurement, manufacturer, and customer distribu-tion. Supplier integration also focuses on activities that create close ties with material and

ser-26

vice providing supply chain partners. Competency in this area links externally performed ac-tivities into a seamless flow with internal work processes. Firms that desire to excel must blend their operating processes into those of supply partners in order to meet increasingly broad and demanding customer expectation. Nowadays, the IT industry is shifting from push methods driven by anticipated sales to pull methods that focus on delivering value to custom-ers through rapid response to demand. To do this profitably, firms must strip redundancy and duplication of materials and effort from supply chain operations. The task is all the more challenging because it is not limited to internal activities. It requires linking internal work processes with those of material and service providers. Thus, an important integration deci-sion is how many material and service suppliers to include in synchronized operations. That is, integrating operations with material and service suppliers to form a seamless flow of internal and external work overcomes the financial barriers of vertical ownership while retaining many of the benefits. A successful SCM of operational process integration, cross-functional unification, standardization, simplification, compliance, structural adaptation, operational fu-sion, and supplier management capabilities must be developed.

3.1.1.2 Planning and control process integration competencies of SCM

The planning and control process includes competences of technology and planning in-tegration refers to information systems capable of supporting the wide variety of operational configuration needed and to the development of measurement systems that facilitate segmen-tal strategies and processes to serve diverse market segments (Bowersox et al., 1999). Across the supply chain, information technology and measurement systems must facilitate planning and control of integrated operations. As Bowersox et al. (1999) explain in the 21st Century Logistics framework, success of technology and planning integration rests upon six capabili-ties: information management, internal communications, connectivity, collaborative forecast-ing and plannforecast-ing, and activity-based and total cost management. Information management

27

focuses on supply chain resource allocation through seamless transactions across the total or-der-to-delivery cycle. Internal communication uses technological systems to exchange infor-mation across functional boundaries in a timely, responsive, and usable format. Connectivity extends internal communications capability to supply chain partners. Collaborative forecast-ing and plannforecast-ing involves customers and suppliers developforecast-ing a shared vision supported by a mutual commitment to jointly generated action plans. Activity-based and total cost

manage-ment uses activity-based costing, budgeting, and measurement to obtain a comprehensive

picture of the cost/revenue contribution of a specific customer or product. Operational excel-lence must be supplemented and supported by integrated planning and measurement compe-tences. This process involves joining technologies to monitor, control, and facilitated overall supply chain performance.

3.1.1.3 Behavioral process competencies of SCM

The behavioral process rests on the quality of the basic business relationship between partners. In a competitive environment, single enterprises acting alone cannot fully achieve all management goals. The problem is that different firms typically operate under different man-agement philosophies and pursue divergent goals. Relationship integration refers to the ability to develop and maintain a shared mental framework with customers and suppliers regarding inter-enterprise dependency and principles of collaboration (Bowersox et al., 1999). Quality relationships can improve trust among a firm’s members, and further promote their attitude to and intentions of knowledge sharing in an organization (Yang and Chen, 2007). The relation-ship integration category is a competence that enables firms to build lasting distinctiveness with customers of choice and to share a mentality with customers and suppliers regarding in-terdependency and principles of collaboration. Role specificity is the capability to clarify lea-dership processes and establish shared, as contrasted with individual, enterprise responsibility. Information sharing involves the willingness to exchange key technical, financial, operational

28

and strategic information with others in the supply chain. Any firm seeking supply chain per-formance must demonstrate strong commitment to the customization required for effective customer and relationship integration. Bowersox et al. (1999) suggested, in the Supply Chain 2000 framework and assessment process, that the best way to start the search for integration gaps is by reviewing how a firm coordinates with customers and relationships. Thus, it is clear that consistent success ultimately depends on a firm’s competence to create value for custom-ers by providing products and services at prices that cover total cost and provide a profit to meet customers’ needs.

3.1.2 The constructs of ERP benefits

Markus and Tanis (2000) and Markus et al. (2000) identify various reasons that moti-vate organizations to implement ERP systems. They also suggest that there should be a con-nection between the reasons for adoption of ERP systems and the benefits. Shang and Seddon (2000) compiled an ERP benefits list from ERP vendor success stories published on the World Wide Web. Follow-up interviews and analysis led Shang and Seddon (2000) to classify the different types of ERP benefits into five categories. Stratman and Roth (2002) identified eight theoretically important ERP competences and Vemuri and Shailendra (2006) developed a set of initial measurement items for each competences of ERP. Based on Shang and Seddon’s classification of ERP benefits, Stratman and Roth’s competences of ERP, we must also heed the suggestions of experts who have recently been or are currently going through ERP or SCM systems implementations in Taiwanese IT industry. We conclude that ERP benefits may improve firm competences in SCM.

3.1.2.1 The operational benefits of ERP

Shang and Seddon (2000) determined that the operational benefits of an ERP system arise from automating cross functional process. They encompass both efficiency-based and

29

effectiveness-based performance improvements in order to capture the enterprise-wide busi-ness benefits. Those benefits are expected to improve day-to-day operations (short-term im-pact), which include improved inventory control, improved cash management, and reduction in operating costs (Stratman and Roth, 2002). They will also lead to improvements in produc-tion, information and customer service quality. Today’s ERP solutions offer even more bene-fits. Many vendors have begun to enhance their offerings with extended supply chain applica-tions in an effort to create a seamless, integrated information flow, from suppliers through manufacturing and distribution. ERP is a suite of application modules that can link back-office operations to front-office operations, as well as internal and external supply chains (Verville and Halingten, 2003). Latamore (1999) has argued that a core ERP system for operational function must include applications for forecasting, production scheduling, materi-al planning, inventory control, warehouse management, etc.

3.1.2.2 The managerial and organizational benefits of ERP

The managerial benefits arise from the use of databases to plan better and for better management of production, manpower, inventory and physical resources. Also, firms are get-ting benefits from monitoring and controlling of financial performance in the contexts of products, customers, business lines and geographic area (Shang and Seddon, 2000). Since ERP systems can automate business processes and enable process changes, one would expect them to offer all of the above types of benefits. Also, since process knowledge is dynamic, organizations may derive benefits from procedures and practices that continuously allow fun-damental business processes to be improved in a systematic fashion (Roth et al., 1994). That is, managerial benefits are expected to improve the day-to-day business process (long-term impact) which reflects long-term benefits. Those benefits include improving customer res-ponsiveness, customer satisfaction, on-time delivery, and decision making. They are provided by centralizing the database and built-in data analysis capabilities. Furthermore, ERP systems

30

provide information benefits to process and resources management (Stratman and Roth, 2002; King and Teo, 1996; Guha et al., 1997). Furthermore, firms are likely to increase control over their suppliers by gaining power from information (Cox et al., 2000; Nah et al., 2001), and ERP applications, or similar integration solutions, are a leading tool for this purpose (Sawy et al.,1999; Themistocleous et al., 2002). When an ERP system is implemented, the advantage of business process skills is demonstrated by understanding of how the business operates, and the ability to predict the impact of a particular decision or action on the rest of the enterprise. At the same time, those benefits, such as production orders, capability planning, resource al-location, production tracking and reporting, inventory management, waste/reject tracking, etc., also meet the competences needs of supply chains (Latamore , 1999).

3.1.2.3 The strategic and IT infrastructure benefits of ERP

The strategic benefits of ERP are a consequence of the system’s ability to support busi-ness growth, reduce the cost of maintaining legacy systems, and capture the benefits derived from facilitation business learning, empowerment of staff and higher levels of employee mo-rale and satisfaction (Shang and Seddon, 2000). IT infrastructure benefit of ERP is an indica-tion of an organizaindica-tion’s competence in matching IT capabilities with the changing, cross-functional business requirements of the enterprise. Several studies suggest that it is crit-ical that a firm’s information technology systems support the strategic goals of the firm (Sampler, 1998). Strategic and IT infrastructure benefit help to ensure that IT development goals are aligned with the needs of the organization (Segars et al., 1998). Dynamically changing business needs may require operations strategy planners to continually evaluate cross-functional business goals and define the information systems capabilities that are re-quired to support these goals. Thus, a formal strategic benefit and IT infrastructure benefit is posited to contribute to the quality of this ongoing activity, especially activity that can leve-rage supply chain processes to enhance performance need in each particular operating arena.

31

Figure 3.1 The proposed conceptual model and research hypotheses

Ha1 Ha2 Ha3 Hb1 Hb2 Hb3 Hc1 Hc2 Hc3 Operational Process Behavioral Process Planning and Control Process SCM Competences Operational ERP Benefits IT Infrastructure Organizational Managerial Strategic Hd3 He1 He2 He3 Hd2 Hd1