行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 期末報告

企業特定的管理能力與環境變動(第 2 年)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 99-2410-H-004-012-MY2 執 行 期 間 : 100 年 08 月 01 日至 102 年 01 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學國際經營與貿易學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 譚丹琪 計畫參與人員: 碩士級-專任助理人員:張靜尹 碩士級-專任助理人員:張家榕 學士級-專任助理人員:劉盈孜 學士級-專任助理人員:莊佳樺 公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 102 年 05 月 03 日

中 文 摘 要 : 此為期兩年的計劃探討企業特定的管理能力在環境變動下的 角色。雖然資源基礎觀點視此管理能力為持續性競爭優勢的 來源,文獻中對企業特定管理能力是否有助企業因應環境變 動有不一致的看法,本計劃以食物加工業者在 1997 至 2001 年間對有機與天然食物的產業新趨勢的因應來探討這個課 題。實證結果發現企業特定管理經驗對因應產業外生變動有 不利的影響, 但當經理人有較多的國外工作經驗與業者本身 有較多的海外購併經驗時, 此不利影響會顯著削弱. 中文關鍵詞: 企業特定性, 管理能力, 環境變動

英 文 摘 要 : This two-year project explores the role of firm-specific managerial capability in changing environments. Although the resource-based view considers firm-specific managerial capability as a source of sustained competitive advantages,

researchers hold mixed views regarding the usefulness of firm-specific managerial capability in changing environments. We address this issue by examining the acquisition behaviors of food processing companies between 1997 and 2001 in which there was an emerging trend for organic and healthy food products in the food processing industries. We find that food processing companies with greater firm-specific managerial experience made fewer organic and healthy food acquisitions during the study period. However, the negative he negative impact of firm-specific managerial experience on organization changes is mitigated when managers develop their on-the-job learning in foreign markets or in firms that made more foreign acquisitions. This suggests that firm-specific managerial experience is more conducive in addressing dynamic environments when such experience is accumulated in a learning task environment with diverse and unfamiliar stimuli.

英文關鍵詞: Firm specificity, managerial capability, changing environment

1

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

期末報告

企業特定的管理能力與環境變動

計畫類別:個別型計畫

計畫編號:

NSC-99-2410-H-004-012-MY2

執行期間:99 年 8 月 1 日至 101 年 7 月 31 日(經申請延長到 102

年 1 月 31 日)

執行機構及系所:政大國貿

計畫主持人:譚丹琪

中 華 民 國 102 年 4 月 22 日

2 摘要 此為期兩年的計劃探討企業特定的管理能力在環境變動下的角色。雖然資源基礎觀點視此 管理能力為持續性競爭優勢的來源,文獻中對企業特定管理能力是否有助企業因應環境變 動有不一致的看法,本計劃以食物加工業者在1997 至 2001 年間對有機與天然食物的產業 新趨勢的因應來探討這個課題。實證結果發現企業特定管理經驗對因應產業外生變動有不 利的影響, 但當經理人有較多的國外工作經驗與業者本身有較多的海外購併經驗時, 此不 利影響會顯著削弱. 關鍵字: 企業特定性, 管理能力, 環境變動 Abstract

This two-year project explores the role of firm-specific managerial capability in changing environments. Although the resource-based view considers firm-specific managerial capability as a source of sustained competitive advantages, researchers hold mixed views regarding the usefulness of firm-specific managerial capability in changing environments. We address this issue by examining the acquisition behaviors of food processing companies between 1997 and 2001 in which there was an emerging trend for organic and healthy food products in the food processing industries. We find that food processing companies with greater firm-specific managerial experience made fewer organic and healthy food acquisitions during the study period. However, the negative impact of firm-specific managerial experience on organization changes is mitigated when managers develop their on-the-job learning in foreign markets or in firms that made more foreign acquisitions. This suggests that firm-specific managerial

3

experience is more conducive in addressing dynamic environments when such experience is accumulated in a learning task environment with diverse and unfamiliar stimuli.

4 Introduction

How firms respond to exogenous shifts in the environment is an important issue for strategic management scholars and practitioners (Kirzner, 1973; Penrose, 1959). The exogenous shifts include changes in technology, demand conditions, market trends and customer preferences, industry (de)regulation, and competition. The literature has noted that firms differ in their responsiveness to these exogenous shifts (Siggelkow, 2002). Some firms show more alertness in perceiving and noticing these shifts in the opportunity space (Teece, 2007) and act more swiftly to re-align with the modified customer needs, new competitive reality, and emerging technology trends (Benner and Tripsas, 2012; Danneels, 2011).

A key reason why firms differ in their responses to exogenous shifts in the environment is that these external shifts and emerging opportunities aren’t objective phenomena, and the optimal or appropriate type and level of response (or re-alignment) are not obvious (Danneels, 2005). These emerging opportunities (and threats) that arise from these shifts are highly subject to interpretation by managers and entrepreneurs. An exogenous change can have different meanings and consequences for each firm due to its unique capabilities and commitments and because of subjectivism in managerial perceptions, expectations, and preferences (Kor, Mahoney, and Michael, 2007). Differences in managerial alertness, judgment, and learning as part of the top management team (or entrepreneurial team) capacity impact the firm’s assessment on new internal and external information (Foss, Klein, Kor, and Mahoney, 2008).

5

Another reason for the differential responses to exogenous shifts is that managers differ in their capacity of implementing organizational changes to re-align with the new customer needs, competitive reality, and technology trends. The literature has shown critical factors that affect a firm’s willingness to changes, such as organizational inertia and managerial overcommitment to status quo and its capability of implementing organizational changes; specifically, its ability to obtaining external resources and competencies and to integrating them with its internal resources (Teece et al., 1997).

Given the key role of key role of management in shaping a firm’s strategic renewal, and that the skills and capabilities of management are embedded in their prior experience, this study focuses on how managerial experiences affect their firms’ response to exogenous shifts in the environment. We study a wave of acquisitions that took place in the food manufacturing industry between 1997 and 2002. 1997 marked the year when the Organics Food Product Act appeared in Federal register and 2002 was the year when this act was ultimately enacted. The organic and healthy food acquisitions took place in this period were considered as early responses by food companies to the emerging trend of consumer demand for healthy/natural food and organic-certified food in the U.S. We examine how a firm’s response may be associated with the firm’s managerial experience and its prior acquisition experience.

Our empirical evidence based on U.S. food manufacturing firms indicates that firm-specific managerial tenure has a negative relationship with the number of organic food and healthy food acquisitions made by their firms between 1997 and 2002. However, this negative

6

relationship is mitigated in terms of organic food acquisitions for firms that had substantial prior experience in acquiring diversified businesses and in acquiring foreign companies.

Theoretical Development

Managers accumulate firm-specific knowledge and relationships through their experience with the firms. The firm-specific managerial capabilities have been considered as the most important determinant of the growth of the firm (Penrose, 1959), and a major source of sustained competitive advantages (e.g., Coff, 1999; Mahoney and Pandian, 1992; Wang, He, and Mahoney, 2009).

However, the literature holds mixed views regarding the usefulness of firm-specific managerial capability in changing environments. On the one hand, research focusing on managers’ cognition and incentives typically sees firm specificity in managerial capabilities as one reason why firms fail to respond to environmental changes. According to this line of research, managerial tenure, an indicator of the level of firm specificity in managerial capability, elevates managerial entrenchment (e.g., Hill and Phan, 1991), and leads to the negligence of environmental changes and an overcommitment to the status quo (e.g., Hambrick, Geletkanycz, and Fredrickson, 1993; Miller, 1991). These are disruptive to a firm’s ability to adapt to changing environments.

7

managers’ firm-specific knowledge and relationships differently. This view suggests that a firm’s capability of responding to changing environments lies in its ability to integrate, build, and reconfiguring internal and external competencies. Firm-specific knowledge and relationship is a precondition for this capability because managers need intra-firm social capital in order to mobilize, integrate, and reconfigure resources and competences effectively (Adner and Helfat, 2003). Managers also need firm-specific capabilities to shape the economic incentives and organizational culture to enable firms to transit successfully to new environments (Taylor and Helfat, 2009).

The empirical evidence is mixed with indications that firm-specific managerial capital can be both valuable (e.g., Hatch and Dyer, 2004; Kor, 2003) and detrimental to strategic renewal (e.g., Finkenstein and Hambrick, 1990; Musteen, Barker, and Baeten, 2006). Specifically, empirical evidences show strong support to the positive performance effect of firm-specific managerial capability in stable environments, but do not reach consistent conclusions regarding the impact of this capability in changing environments. Recent refinements to this research showd that firm-specific managerial experience can be contingent on critical industry conditions such as dynamism (Henderson, Miller, and Hambrick, 2006) and is linked to organizational outcomes such as innovativeness in a curvilinear fashion (Wu, Levitas, and Priem, 2005). Thus, the contextual influences and moderators seem to really drive the net impact and meanings of managerial knowledge, experience, and skill sets with respect to their contributions to the renewal of the firms’ product portfolios and capability bundles.

8

Firm-specific managerial experience

Managers’ firm-specific experience enables managers to accumulate managerial knowledge and relationship specific to a firm. Such a managerial capability loses at least part of its value when redeploying outside the firm. According to Penrose (1959), firm-specific managerial capability is the key driver to the growth of the firm. She suggests that the very nature of a firm is an administrative organization, and thus planning and managing expansion projects requires that managers with experience internal to the firm “at least know and approve, even if they do not in detail control all aspects of, the plans and operations of the firm” (1959: 45). Therefore, firm-specific managerial capability is a crucial input for the growth of the firm. Firm-specific managerial capability also can be a source of sustained competitive advantages. First, managers make decisions about the exploitation and exploration of production factors (Penrose, 1959), and their capabilities explain the differences in designing and implementing corporate strategies between firms (Adner and Helfat, 2003). In addition, firm-specific managerial capability fosters the development and deployment of firm-specific competencies (Wang, He, and Mahoney, 2009), and these competencies resist imitation because they are valuable, scarce, and at the same time cannot be traded and re-deployed outside the firm (Dierickx and Cool, 1989; Mahoney and Pandian, 1992).

However, the literature holds mixed views regarding the impact of firm-specific managerial experiences/capabilities on a firm’s strategic renewal. According to the dynamic capability view (e.g., Teece, Pisano, and Shuen, 1997), firm-specific managerial capability is a prerequisite for a firm attempting to implement organizational changes. The dynamic capability view argues that

9

a firm’s capability of responding to changing environments lies in its ability to integrate, build, and reconfiguring internal and external resources and competencies. Management plays a key role in shaping this capability (Augier and Teece, 2009) because managers need intra-firm social capital in order to mobilize, integrate, and reconfigure resources and competences effectively (Adner and Helfat, 2003). Top managers also need firm-specific knowledge to motivate the middle management so that their firms can transit successfully to the new environment (Taylor and Helfat, 2009).

However, long managerial tenure is likely to hamper a firm’s ability to adapt to external environmental changes. First, managers with very long tenures at their firms may fail to detect environmental changes and are unable to recognize the need of their firms to respond the changes. Managers who enjoy long periods of tenure at their firms typically have good track records; otherwise they would be replaced (Pfeffer and Leblebici, 1973). Their past good performance may cause these managers to be independent and complacent (Miller, 1991), and to become convinced of the correctness of their firms’ current strategies (Hambrick, Geletkanycz, and Fredrickson, 1993). In addition, long managerial team experience may create intra-firm managerial networks that are over-embedded (Burt, 1992; Uzzi, 1997) that restrict information flows from outside (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1990) and thus promote groupthink (Kor, 2003).

In addition, long managerial tenure may result in managers’ overcommitment to status quo and consequently their resistance to organizational changes. Managers with long firm-specific

10

tenure have made substantial specific investment in their firms; since their skills are embedded in the current form of their firms, any organizational changes may reduce the values of the firm-specific skills of the managers (Shleifer and Vishny, 1989). In addition, organizational changes such as shifts in organizational structures or reallocation of resources may disturb internal political equilibrium in the current firm (Hennan and Freeman, 1977; Zald, 1970) and hence can be perceived a threat to the power of managers. Since managers often have more to lose than to gain from organizational changes, they tend to stay with the status quo (Hambrick, Geletkanycz, and Fredrickson, 1993). Miller and Friesen (1980) thus argue that long serving CEOs often show politically and emotionally motivated resistance to change.

Finally, a long managerial tenure can circumvent monitoring mechanisms within a firm and may cause managerial entrenchment (Hill and Phan, 1991). CEOs’ power typically increases with their tenures and thus long serving CEOs have greater influences over the selection of board members. CEOs also develop personal relationships with outside directors along the course of their tenures, and hence increase their influences on the directors. As a result, board independence often declines with CEO tenure (Hermalin and Weisbach, 1998).

In sum, the literature suggests opposing views on the impact of firm-specific managerial experience on the active response to external environmental changes. On the one hand, firm-specific experience improves a manager’s ability to effectively implement resource reconfiguration and orchestrate organizational changes. On the other hand, firm-specific tenure is likely to reduce the manager’s ability to detect external changes while increasing their

11

incentive to resist organizational changes. Thus we present a set of opposing hypotheses.

H1a: Firm-specific managerial experience has a positive relationship with a firm’s active response to exogenous shifts in its industry environment.

H1b: Firm-specific managerial experience has a negative relationship with a firm’s active response to exogenous shifts in its industry environment.

Managers accumulate their firm-specific capabilities and knowledge from a series of path-dependent learning experiences within their firm (Dierickx and Cool, 1989; Teece, et al., 1998). The task environment in which managers accumulate their on-the-job learning can affect the types of capabilities and knowledge that managers have gained over time and eventually how their firms sense and respond to external shifts in the environment. This is because managers acquire particular skills and lessons from handling particular managerial challenges and these particular skills become the basis of the routines of their firm (March and Simon, 1958; Nelson and Winter, 1982). These routines, while serving the purpose of economizing managerial attention, can exert a boundary of managerial search and managerial choice (March and Simon, 1958; Nelson and Winter, 1982).

Managers are likely to have greater and more dynamic sets of skills when they have worked for firms that provide more diverse learning-by-doing environments for their managers (Tan and Mahoney, 2007). Such environments expose managers to various stimuli that enlarge their managerial repertoires (Huber, 1991) and enable managers to develop a more dynamic set

12

of skills, which would become the basis of a more dynamic set of firm routines, that enable the firm to meet different environmental changes.

We propose that foreign environments represent a type of task environment that nurture the development of a more dynamic set of managerial skills and firm routines that are helpful in addressing external environmental changes. The cultural, economic, and institutional differences between home and foreign markets can create unprecedented managerial challenges that require a firm to often adapt its routines and even develop new ones (Luo and Peng, 1999; Lord and Ranft, 2000) and hence help train the firm and its managers to be responsive to new stimuli. On the individual level, foreign work experience can broaden their cognitive horizon (Carpenter and Fredrickson, 2001; Sambharya, 1996) and thus can cultivate their ability to recognize and assess new business opportunities in unfamiliar environments under which information is insufficient. In addition, managers with diverse work experience, within the same company or elsewhere, may have developed capabilities and personal networks that support the access of resources needed in entering new product or geographical markets (Athanassiou and Nigh, 1999; Holm, Eriksson and Johanson, 1996). We therefore expect that firm-specific managerial capabilities is more conducive to organizational change when managers have greater foreign work experience and when their firms have greater prior foreign acquisition experience.

H2: Firm-specific managerial experience has a more positive relationship with a firm’s active response to exogenous shifts in its industry environment when managers have greater foreign work experience.

13

H3: Firm-specific managerial experience has a more positive relationship with a firm’s active response to exogenous shifts in its industry environment in a firm with greater foreign acquisition experience.

Methodology

I originally planned to use Taiwanese listed firms to conduct empirical studies. After purchasing the top management team (firm tenure) data, I found that the data are not reliable in that some tenure data actually refer to position tenure while the other report firm tenure. Therefore, I decide to collaborate with Professor Yasemin Kor (University of South Carolina) to obtain a more reliable set of top management team (for US companies) data. We decide to track the response of US food companies to the healthy and organic food trends in the late 1990s and investigate how such a response can be affected by firm-specific managerial experience.

Research context

In the past two decades, there has been increased consumer awareness and interest in the consumption of natural and healthy products. This trend is observed in food, beverage, and personal care product industries although in this paper we focus on the food industry. There has also been an increased interest in the consumption of organic produce and food which is free of toxins, artificial additives and preservatives, and pesticides.

14

According to the Organic Trade Association’s 2007 Manufacturer Survey, the U.S. organic industry grew 21 percent and reached $17.7 billion in consumer sales in 2006. Organic foods and beverages are among the fastest growing food industry segments in the $598 billion food market. The organic category represented approximately 2.8% of total U.S. food sales in 2006. While this is a relatively small percentage of the total market, the strong growth trajectory suggests that this niche with heterogeneous consumer preferences is becoming an important segment. It is also known that healthy conscious consumers are willing to pay a higher price for the qualities of natural, healthy, and/or organic, which means higher profit margins for food and personal care companies.

At the beginning of the shift in consumer demand, there was no standard definition of what constitutes healthy or natural food product, which often creates confusion among consumers. There has been increasing tendency among food and personal care manufacturers to label products as natural and healthy which may or may not have any basis. However, new legislation was created in the United States to define what constitutes organic. Setting the stage for U.S. National organic standards, the U.S. Congress adopted the Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA) in 1990 as part of the 1990 Farm Bill. It took several years of public input and discussion before Organics Food Product Act appeared in Federal Register on December 16, 1997. National Organic Program final rule was published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in December 2000 and but it was ultimately enacted in October 2002. This legislation enabled the consumers to be able to distinguish between “genuine” organic products and those without the backing of organic practices. National

15

organic standards require that organic growers and handlers be certified by third-party state or private agencies or other organizations that are accredited by USDA (Organic Trade Association website). Consumers can look for the “USDA Organic” seal or other approved labeling. Products labeled “100% Organic” and carrying the “USDA Organic” seal have to contain all organically produced ingredients (Organic Trade Association).

This combination of increasing consumer interest, awareness, and organic certification and labeling process (as defined by law) sent a strong opportunity signal to food companies and entrepreneurs. The existing food manufacturers, in particular, started to acknowledge the importance of this emerging market segment. While some firms went on to develop their own organic products, many industry incumbents chose to do acquisitions in this space by acquiring small existing firms that have already developed brand awareness among health-conscious customers. 1997 marked the year when the Organics Food Product Act appeared in Federal register and 2002 was the year when this act was ultimately enacted. The organic and healthy food acquisitions took place in this period were considered as early responses by food companies to the emerging trend of consumer demand for healthy/natural food and organic-certified food in the U.S.

Data and measures

Our population consists of 105 firms in US food industry (SIC20). After excluding firms whose headquarters are located outside US and those whose primary product is not food processing, we are left with 50 food processing companies. Lack of historical data on firm and management

16

reduces our sample to 34 firms.

Our dependent variable is the food company’s active response to the emerging consumer awareness and interest in the consumption of natural and healthy products. As discussed above, we consider the organic and healthy food acquisitions that took place during 1997 and 2001, five years before the Organics Food Product Act was enacted, as early responses by food companies to the shifts in consumer demand for healthy/natural food and organic-certified food in the U.S. Thus, our dependent variable is the number of organic /healthy food acquisition that a food company made during this period. We obtained the acquisition data from the SDC database. We identified organic / healthy acquisitions through tracing historical news from the Lexis-Nexis database, Web search, and company websites.

Our key constructs focus on the attributes of top managers. The top managers defined in our paper include CEOs, COOs, all presidents and all senior managers with international positions. Firm-specific managerial experience is the average number of years that a firm’s top managers have been on the managerial positions. Managerial foreign work experience is the average number of years that a firm’s managers had been on international managerial assignments. Foreign acquisition experience is the number of foreign acquisitions made by a firm five years before our study period (i.e., 1992~1996).

We include a number of control variables. Prior Organic Food Acquisition is the number of organic food acquisitions made by the firm between 1992 and 1996. Prior Healthy Food

17

Acquisition is the number of healthy food acquisitions made by the firm between 1992 and 1996. A firm that has prior experience in acquiring organic or healthy food companies is likely to have already sensed the emerging trend for organic and healthy foods and have developed related routines to make further organic / healthy food acquisitions. Firm size is measured by the average number of employees of the firm between 1997 and 2001. Larger firms may have greater resources to conduct acquisitions. Marketing capabilities is the average selling intensity of a firm between 1992 and 1996. Firms with greater marketing capabilities are likely to be more able to spot the emerging demand for organic and healthy foods earlier. Profitability is the average return on assets of a firm between 1992 and 1996. Firms with greater profitability are likely to have greater financial and managerial resources to support new market entry.

Results and Discussion

Of 34 food firms in our sample, 7 made a total of 15 organic food acquisitions between 1997 and 2001, while 9 made a total of 16 healthy food acquisitions during the same period. 4 firms made both organic and healthy food acquisitions, while 22 of them made neither acquisitions. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables. The maximum number of organic food acquisitions made by one firm during this period is 5 (Hain Celestial Group); this number for healthy food acquisitions is 4 (Dean Foods).

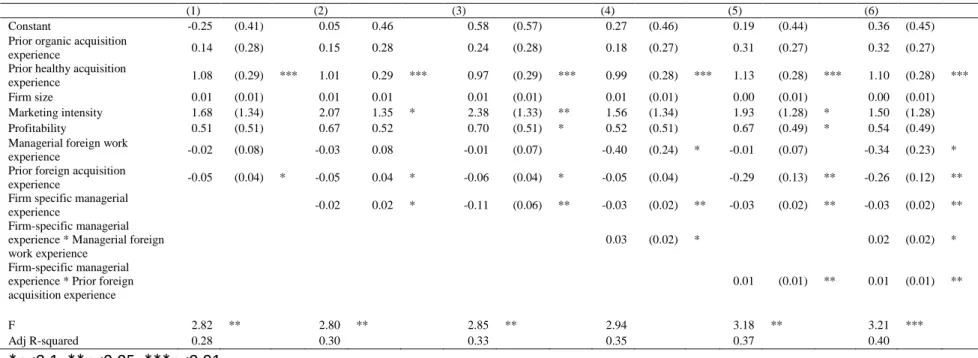

Table 2 reports the regression results for organic food acquisitions. All models are significant and have good fits. The first column includes control variables only. As expected,

18

prior organic and healthy food acquisitions were found to be positively associated with the number of organic food acquisitions made during this period. Firms with greater marketing capabilities are also found to have made more organic food acquisitions between 1997~2001. We also found that firms that made more foreign acquisitions in the earlier period tend to make fewer organic food acquisitions this period. Columns 2 – 5 include our explanatory variables separately and the last column includes all explanatory variables. The coefficient of firm-specific managerial experience is significantly negative, consistent with H1b. This supports the view that firm-specific managerial experience hampers a firm’s ability to aggressively respond to exogenous shifts in the environment. The coefficient of the interaction term between managerial firm-specific experience and managerial foreign work experience is positive and significant at the 0.1 level, showing that firm-specific managerial experience indeed has a weaker negative impact on the number of organic food acquisitions made between 1997~2001 when the managers have greater foreign work experience. H2 is supportive for organic food acquisitions. Finally, the coefficient of the interaction term between managerial firm-specific experience and the firm’s prior foreign acquisition experience is positive and significant at the 0.05 level, suggesting that a firm’s prior foreign acquisition experience indeed positively moderates the relationship between firm-specific managerial experience and organic food acquisition. In other words, the negative effect of firm-specific managerial experience on the firm’s expansion into the organic foods market is weakened for firms that have made more foreign acquisitions. H3 is supported.

19

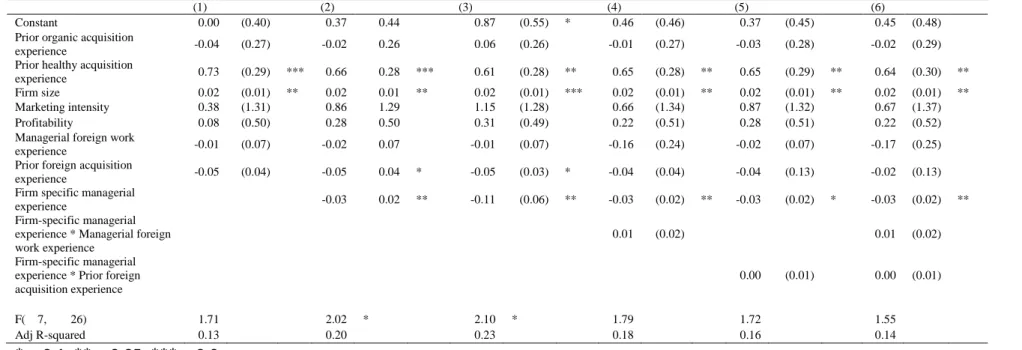

includes control variables only. Larger firms and firms with greater prior experience in making healthy food acquisitions are found to make more healthy food acquisitions between 1997-2001. Columns 2 – 5 include our explanatory variables separately and the last column includes all explanatory variables. The coefficient of firm-specific managerial experience is significantly negative. This supports the view that firms with greater firm-specific managerial experience have fewer more healthy food acquisitions early in the emerging trend of consumer demand for healthy/natural food and organic-certified food in the U.S. H1b is supported for healthy food acquisitions. Both the coefficient of the interaction term between managerial firm-specific experience and managerial foreign work experience and the coefficient of the interaction term between managerial firm-specific experience and prior foreign acquisition experience are not significant. Therefore, H2 and H3 are not supported for healthy food acquisitions.

Overall, our empirical testing provides support to our main argument. While firm-specific managerial capability fosters effective deployment of firm-specific competencies and could be a source of sustained competitive advantages in static environments, our findings indicate that firm-specific managerial experience is likely to delay a firm’s adaptive responses in dynamic environments. However, our finding also indicates that the negative impact of firm-specific managerial experience on organization changes is mitigated when managers develop their on-the-job learning in foreign markets or in firms that made more foreign acquisitions. This suggests that firm-specific managerial experience is more conducive in addressing dynamic environments when such experience is accumulated in a learning task environment with diverse and unfamiliar stimuli.

20

It should be noted that our explanatory variables provide better predictions for the firms’ decision to make organic food acquisitions than for their decision to make healthy food acquisitions. Organic food acquisitions and healthy food acquisitions likely present different types of challenges for managers and thus represents different types of firm responses to the emerging trend in the food industry. Organic production is based on a system of farming that maintains and replenishes soil fertility without the use of toxic and persistent pesticides and fertilizers. They must be produced without the use of antibiotics, synthetic hormones, genetic engineering and other excluded practices, sewage sludge, or irradiation. Organic food market entry is thus likely to a more “distant” business path than healthy food market entry for traditional food processing companies and its entry would require more fundamental and radical changes within organizations. In contrast, while the entry into healthy food markets may also require new product design and marketing campaign, healthy foods are likely to be based on the same production/processing technologies and can be promoted through similar distribution channels as a firm’s other food related products. Thus, healthy food market entry may be considered as a more adaptive and less aggressive response than organic food market entry to the new and emerging consumer demand. Future studies should further examine the determinants of a firm’s entry into healthy food industries.

Self Evaluation of the Project

21

attributes affect firm responses to exogenous shifts in the environment. A short paper (co-authored with Yasemin Kor) based on this project will be presented in the 29th EGOS (European Group for Organizational Studies) Colloquium held in Montréal, Canada between July 4–6, 2013. This report is taken from the short paper.

22

Table 1 Basic Statistics

Variables Mean SD Min Max Organic food acquisitions, 1997~2001 0.441 1.078 0 5 Healthy Food acquisitions, 1997~2001 0.471 0.961 0 4 Prior organic food acquisitions, 1992~1996 0.235 0.699 0 3 Prior healthy food acquisitions, 1992~1996 0.265 0.666 0 3 Firm size 17.282 30.196 0.048 142.7 Marketing intensity 0.257 0.160 .046 0.847 Profitability -0.023 0.404 -2.285 0.159 Managerial foreign work experience 0.735 2.151 0 10 Prior foreign acquisitions 2.441 7.382 0 37 Managerial firm-specific experience 16.853 9.557 1 42 Conclusions

23

Table 2 Regression Results for Organic Food Acquisition, 1997~2001

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Constant -0.25 (0.41) 0.05 0.46 0.58 (0.57) 0.27 (0.46) 0.19 (0.44) 0.36 (0.45) Prior organic acquisition

experience 0.14 (0.28) 0.15 0.28 0.24 (0.28) 0.18 (0.27) 0.31 (0.27) 0.32 (0.27) Prior healthy acquisition

experience 1.08 (0.29) *** 1.01 0.29 *** 0.97 (0.29) *** 0.99 (0.28) *** 1.13 (0.28) *** 1.10 (0.28) *** Firm size 0.01 (0.01) 0.01 0.01 0.01 (0.01) 0.01 (0.01) 0.00 (0.01) 0.00 (0.01) Marketing intensity 1.68 (1.34) 2.07 1.35 * 2.38 (1.33) ** 1.56 (1.34) 1.93 (1.28) * 1.50 (1.28) Profitability 0.51 (0.51) 0.67 0.52 0.70 (0.51) * 0.52 (0.51) 0.67 (0.49) * 0.54 (0.49) Managerial foreign work

experience -0.02 (0.08) -0.03 0.08 -0.01 (0.07) -0.40 (0.24) * -0.01 (0.07) -0.34 (0.23) * Prior foreign acquisition

experience -0.05 (0.04) * -0.05 0.04 * -0.06 (0.04) * -0.05 (0.04) -0.29 (0.13) ** -0.26 (0.12) ** Firm specific managerial

experience -0.02 0.02 * -0.11 (0.06) ** -0.03 (0.02) ** -0.03 (0.02) ** -0.03 (0.02) ** Firm-specific managerial

experience * Managerial foreign work experience

0.03 (0.02) * 0.02 (0.02) * Firm-specific managerial

experience * Prior foreign acquisition experience

0.01 (0.01) ** 0.01 (0.01) **

F 2.82 ** 2.80 ** 2.85 ** 2.94 3.18 ** 3.21 *** Adj R-squared 0.28 0.30 0.33 0.35 0.37 0.40

24

Table 3 Regression Results for Healthy Food Acquisitions, 1997~ 2001

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Constant 0.00 (0.40) 0.37 0.44 0.87 (0.55) * 0.46 (0.46) 0.37 (0.45) 0.45 (0.48) Prior organic acquisition

experience -0.04 (0.27) -0.02 0.26 0.06 (0.26) -0.01 (0.27) -0.03 (0.28) -0.02 (0.29) Prior healthy acquisition

experience 0.73 (0.29) *** 0.66 0.28 *** 0.61 (0.28) ** 0.65 (0.28) ** 0.65 (0.29) ** 0.64 (0.30) ** Firm size 0.02 (0.01) ** 0.02 0.01 ** 0.02 (0.01) *** 0.02 (0.01) ** 0.02 (0.01) ** 0.02 (0.01) ** Marketing intensity 0.38 (1.31) 0.86 1.29 1.15 (1.28) 0.66 (1.34) 0.87 (1.32) 0.67 (1.37) Profitability 0.08 (0.50) 0.28 0.50 0.31 (0.49) 0.22 (0.51) 0.28 (0.51) 0.22 (0.52) Managerial foreign work

experience -0.01 (0.07) -0.02 0.07 -0.01 (0.07) -0.16 (0.24) -0.02 (0.07) -0.17 (0.25) Prior foreign acquisition

experience -0.05 (0.04) -0.05 0.04 * -0.05 (0.03) * -0.04 (0.04) -0.04 (0.13) -0.02 (0.13) Firm specific managerial

experience -0.03 0.02 ** -0.11 (0.06) ** -0.03 (0.02) ** -0.03 (0.02) * -0.03 (0.02) ** Firm-specific managerial

experience * Managerial foreign work experience

0.01 (0.02) 0.01 (0.02) Firm-specific managerial

experience * Prior foreign acquisition experience

0.00 (0.01) 0.00 (0.01)

F( 7, 26) 1.71 2.02 * 2.10 * 1.79 1.72 1.55 Adj R-squared 0.13 0.20 0.23 0.18 0.16 0.14

25

References

Adner, R. and Helfat, C. 2003. Dynamic managerial capabilities and corporate effects. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10): 1011-1027.

Benner M, Tripsas M. 2012. The influence of prior industry affiliation on framing in nascent industries: The evolution of digital cameras. Strategic Management Journal, 33: 277-302.

Castanias RP, CE Helfat. 1991. Managerial resources and rents, Journal of Management, 17(1): 155-171.

Coff R. 1999. When competitive advantage doesn’t lead to performance: The Resource-based view and stakeholder bargaining power. Organization Science, 10(2): 119-133.

Danneels E. 2005. Tight-loose coupling with customers: The enactment of customer orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 24: 559-576.

Danneels E. 2011. Trying to become a different type of company: Dynamic capability at Smith Corona. Strategic Management Journal, 32(1): 1-31.

Foss NJ, Klein PG, Kor YY, Mahoney JT. 2008. Entrepreneurship, subjectivism, and the

resource-based view: Towards a new synthesis. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(1): 73-94. Hambrick, D. C., Geletkanycz, M.A., and Fredrickson, J.W. (1993). Top executive commitment to the status quo. Strategic Management Journal, 14: 401-418.

Hannan, M. T., and J. Freeman (1977). The population ecology of organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 82: 929-964.

Hannan, M. T., and J. Freeman (1984). Organizational Ecology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hermalin, B.E., and Weisbach, M.S. (1998). Endogenously chosen boards of directors and their monitoring of the CEO. American Economic Review, 96-118.

Hill, C.W.L., and Phan, P. 1991. CEO tenure as a determinant of CEO pay. Academy of Management Journal, 34: 707-717.

Huber, G. P. 1991. Organizational Learning: The Contributing Processes and the Literatures, Organization Science, 2 (1): 88-115.

26

Klein PG. 2007. The place of Austrian economics in entrepreneurship research. Working paper, McQuinn Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership, University of Missouri.

Kor YY, Mahoney JT, Michael S. 2007. Resources, capabilities, and entrepreneurial perceptions. Journal of Management Studies, 44(7): 1185-1210.

Miller, D. 1981. Stale in the saddle: CEO tenure and the match between organization and environment. Management Science, 37(1): 34-52.

Musteen, Barker and Baeten (2006). CEO attributes associated with attitude toward changes: the direct and moderating effects of CEO tenure. Journal of Business Research, 59: 604-612. Penrose, ET. 1959. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Blackwell, Oxford, UK.

Priem RL. 2007. A consumer perspective on value creation. Academy of Management Review, 32: 219-235.

Priem RL, Li S, Carr JC. 2012. Insights and new directions from demand-side approaches to technology innovation, entrepreneurship, and strategic management research. Journal of Management, 38: 346-374.

Shleifer, A., and R. W. Vishny (1989). Management entrenchment – The case of manager-specific investments. Journal of Financial Economics, 25:123-139.

Siggelkow N. 2002. Evolution toward fit. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(1): 125-150. Taylor, A., and Helfat, C.E. 2009. Organizational linkages for surviving technological change: Complementary assets, middle management, and ambidexterity. Organization Science, 20(4) 718-739.

Teece, D.J., Pisano, A. and Shuen, A. 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7): 537-533.

Teece DJ. 2007. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28: 1319-1350.

Uzzi, B. 1997. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: the paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42: 35-67.

Wang, H.C., He, J., and Mahoney, J. T. 2009. Firm-specific knowledge resources and competitive advantage: the roles of economic- and relationship-based employee governance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(12): 1265-1285.

27

國科會補助計畫衍生研發成果推廣資料表

日期:2013/04/24國科會補助計畫

計畫名稱: 企業特定的管理能力與環境變動 計畫主持人: 譚丹琪 計畫編號: 99-2410-H-004-012-MY2 學門領域: 國際企業無研發成果推廣資料

99 年度專題研究計畫研究成果彙整表

計畫主持人:譚丹琪 計畫編號:99-2410-H-004-012-MY2 計畫名稱:企業特定的管理能力與環境變動 量化 成果項目 實際已達成 數(被接受 或已發表) 預期總達成 數(含實際已 達成數) 本計畫實 際貢獻百 分比 單位 備 註 ( 質 化 說 明:如 數 個 計 畫 共 同 成 果、成 果 列 為 該 期 刊 之 封 面 故 事 ... 等) 期刊論文 0 0 100% 研究報告/技術報告 0 0 100% 研討會論文 0 0 100% 篇 論文著作 專書 0 0 100% 申請中件數 0 0 100% 專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件 件數 0 0 100% 件 技術移轉 權利金 0 0 100% 千元 碩士生 0 0 100% 博士生 0 0 100% 博士後研究員 0 0 100% 國內 參與計畫人力 (本國籍) 專任助理 1 1 100% 人次 期刊論文 1 0 30% 研究報告/技術報告 0 0 100% 研討會論文 2 1 100% 篇 論文著作 專書 0 0 100% 章/本 申請中件數 0 0 100% 專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件 件數 0 0 100% 件 技術移轉 權利金 0 0 100% 千元 碩士生 0 0 100% 博士生 0 0 100% 博士後研究員 0 0 100% 國外 參與計畫人力 (外國籍) 專任助理 0 0 100% 人次其他成果

(

無法以量化表達之成 果如辦理學術活動、獲 得獎項、重要國際合 作、研究成果國際影響 力及其他協助產業技 術發展之具體效益事 項等,請以文字敘述填 列。)Serve as a track chair for the 2013 Academy of International Business Annual Meeting.

Serve as a senior editor for 產業與管理論壇(TSSCI)

Invited to serve on the editorial board of Journal of International Business Studies (SSCI)

成果項目 量化 名稱或內容性質簡述 測驗工具(含質性與量性) 0 課程/模組 0 電腦及網路系統或工具 0 教材 0 舉辦之活動/競賽 0 研討會/工作坊 0 電子報、網站 0 科 教 處 計 畫 加 填 項 目 計畫成果推廣之參與(閱聽)人數 0

國科會補助專題研究計畫成果報告自評表

請就研究內容與原計畫相符程度、達成預期目標情況、研究成果之學術或應用價

值(簡要敘述成果所代表之意義、價值、影響或進一步發展之可能性)

、是否適

合在學術期刊發表或申請專利、主要發現或其他有關價值等,作一綜合評估。

1. 請就研究內容與原計畫相符程度、達成預期目標情況作一綜合評估

■達成目標

□未達成目標(請說明,以 100 字為限)

□實驗失敗

□因故實驗中斷

□其他原因

說明:

2. 研究成果在學術期刊發表或申請專利等情形:

論文:■已發表 □未發表之文稿 □撰寫中 □無

專利:□已獲得 □申請中 ■無

技轉:□已技轉 □洽談中 ■無

其他:(以 100 字為限)

A short paper (co-authored with Yasemin Kor) based on this project will be presented in the 29th EGOS (European Group for Organizational Studies) Colloquium held in Montré;al, Canada between July 4–6, 2013.

3. 請依學術成就、技術創新、社會影響等方面,評估研究成果之學術或應用價

值(簡要敘述成果所代表之意義、價值、影響或進一步發展之可能性)(以

500 字為限)

I think that the paper contributes to the research literature by improving the understanding of how managerial experience influences a firm's response to changing environments.