Brief Communication

Quality of life in patients of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Validation of the

Taiwan Chinese version of the EORTC C30and the EORTC

QLQ-H&N35

W.-C. Chie1, R.-L. Hong2, C.-C. Lai1, L.-L. Ting3& M.-M. Hsu4

1

School of Public Health and Graduate Institute of Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University(E-mail: weichu@episerv.cph.ntu.edu.tw); 2Department of Oncology; 3Department of Radiotherapy;4Department of Otorhinol-aryngology, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan

Accepted in revised form 29 May 2002

Abstract

The authors followed the guidelines of translation and pilot testing of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC-QLQ-H&N35 questionnaires. The questionnaires were given to 50 nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients under active treatment and 50 under follow-up at our institution from November 2000 to June 2001. A retest was conducted 2 weeks after the first interview/form completion for the follow-up group. The intraclass correlation coefficients ofthe two questionnaires were moderate to high in the follow-up group. Cronbach’s a coefficients ofall scales ofthe two questionnaires were P0.70 except that ofcognitive functioning. Correlation of scales measuring similar dimensions of the QLQ-C30 and the SF-36 were moderate to high, while that ofthe QLQ-H&N35 and the QLQ-C30 and the SF-36 were moderate to low. Patients in the active treatment group had more serious acute problems due to disease and chemotherapy. Patients in the follow-up group had more serious chronic problems due to radiation therapy. We concluded that the Taiwan Chinese version ofthe EORTC QLQ-C30 and the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 had moderate to high test–retest reliability, high internal consistency in most scales, and could show the expected differences between patients in active treatment and follow-up group.

Key words: The EORTC QLQ-H&N35, The EORTC QLQ-C30, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Quality oflife

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a special type ofhead and neck cancer very common to south-east Asian and southern Chinese populations [1]. According to the Cancer Registry, the age-ad-justed incidence ofNPC in Taiwan in 1997 was 7.90 per 100,000 population in men and 2.96 per 100,000 population in women. The 5-year survival ofearly-stage disease with radiotherapy is around 70% and that ofadvanced stage with combination ofchemotherapy and radiotherapy is approaching 50% [2, 3]. The relatively high cure rate and long survival implied that health-related quality oflife should be an important issue in the treatment and follow-up of this disease.

The European Organization for Research and Treatment ofCancer (EORTC) developed both cancer specific and site-specific questionnaires for the measurement ofquality oflife ofcancer pa-tients. The EORTC QLQ-C30 contains 30 ques-tions belonging to five functional scales, nine symptom scales, financial difficulty, and one global health status (quality oflife) scale. Previous studies showed good reliability and validity for different cancer diagnoses [4–8]. The EORTC QLQ-H&N35 was designed as a supplement to the EORTC QLQ-C30 for the use in head and neck cancer clinical trials. Previous studies also showed good reliability and validity among patients with head and neck cancers in different countries [9–11]. However, NPC was not studied separately from

other head and neck cancers [9, 11], and only 21 NPC patients were included in the 12-country study [10].

The EORTC version 3 has not been translated to Chinese. The only available Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 before this study was the Cantonese translation ofversion 2 in Hong Kong [12], which was different from the language in Taiwan. Though the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 has been validated in Europe, its translation has not been validated on patients speaking non-European languages, nor on NPC which is highly region-specific.

The aims ofthis study were to translate the EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3 and H&N35 to a language commonly used in Taiwan (Traditional Chinese) and conduct a cross-validation ofon NPC patients.

Patients and methods

Translation and pilot testing of the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-H&N35

We followed the guidelines for translation and pilot testing ofthe EORTC [13]. Although there are three major sub-linguistic groups in Taiwan, the questionnaires were translated to Mandarin because only Mandarin has a unified written form. The translation ofthe C30 and the QLQ-H&N were performed in July and January 1998, and approved by the EORTC in August 1999 and May 1999. Compared with the symptoms and treatment side effects ofNPC [3], the question-naires cover most ofthe problems ofNPC patients except some nasal, ear and cranial nerve symptoms (that usually do not affect the QoL ofpatients). Questionnaire used as a comparison instrument The Taiwan Standard version 1.0 [14] ofthe SF-36 [15] was used as a generic comparison instrument, which has been proved to have good reliability and validity [16–19].

Patients and questionnaire completion/interview The full program for NPC treatment included 13 weeks oftreatment and follow-ups once every 3

months in the first 3 years, once every 6 months in the fourth and the fifth years, and once a year thereafter. Each NPC patient enrolled in the treatment plan received mitomycin, epirubicin, and cisplatin on weeks 1 and 4, 5-fluorouracil/ leucovorin on weeks 2 and 8, and radiation ther-apy from week 7 to week 13, with cisplatin on weeks 7, 10, 13 as a part ofconcurrent chemora-diotherapy. We defined patients receiving active treatment (on week 5) and being followed-up at the Department ofOncology ofNational Taiwan University Hospital as two known groups. The choice ofgroups was based on the hypothesis that patients in the active treatment group could have more symptoms and acute side effects ofchemo-therapy, while patients in the follow-up group could have more chronic side effects ofradiother-apy. All patients in the two categories were ap-proached separately between November 2000 and June 2001. Patients whose clinic appointment was outside the assistants’ working time (scheduled by clinic computer and unrelated to QoL) or refused (about 10%) were excluded. The recruitment stopped when the patient numbers for both groups reached 50. A written introduction ofthe study was sent to, and a written consent was obtained from each patient.

Data collection

Patients filled out the questionnaires primarily by themselves. One author (C.C. Lai) and one trained assistant helped those who had difficulties in reading and answering the questions (four pa-tients, two for each group). Both interviewers were fluent in both Mandarin and Taiwanese. Answers were checked immediately by the interviewers if the patients completed the questionnaires by themselves. For patients in the follow-up group, the retests were conducted by self-administration, telephone interview (13 patients), or mailed ques-tionnaire (1 patient) 2 weeks after the first contact. The time interval was based on the recommen-dation ofStreiner and Norman [20].

Data analysis

Answers to the three questionnaires were scored according to the instructions and computer pro-grams provided [21]. Intraclass correlation

coeffi-cient and j coefficoeffi-cient were used to examine the test–retest reliability ofscales and single items with four or two choices, respectively. Pearson’s lation coefficient was used to examine the corre-lation between similar dimensions ofthe different questionnaires. Cronbach’s a coefficient was used to evaluate the internal consistency ofeach di-mension. Wilcoxon’s rank sum test, Cochran Mantel–Haenszel test, and v2 test were used to examine the difference between the two groups of patients on each dimension.

Results

Most patients were male, aged 40–49 years, had an education ofor above senior high school, and spoke Mandarin or Taiwanese (Table 1). Patients oftwo major sub-groups other than Mandarin could read and understand the questions well. Each patient required about 30 min to complete all three questionnaires, regardless ofmode of administration. Halfofthe time was spent on the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35. Patients for whom the retest was conducted by phone reported more serious problems ofteeth and opening mouth than those who was interviewed or completed the questionnaire by mail.

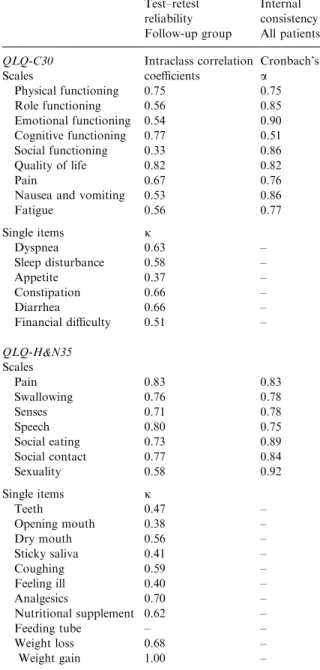

Only the test–retest reliability ofthe follow-up group was examined. The intraclass correlations of

the multi-item scales varied from 0.33 (social functioning) to 0.82 (global health status/quality of life) for the QLQ-C30 and from 0.71 (senses) to 0.80 (speech) for the QLQ-H&N35. The j coeffi-cients ofsingle items varied from 0.37 (appetite loss) to 0.66 (constipation and diarrhea) for the QLQ-C30 and from 0.38 (open mouth) to 1 (weight gain) for the QLQ-H&N35. All of the

Table 1. Basic characteristics ofpatients

Characteristics Active treatment Follow-up

N (%) N (%) Gender Male 39 (78.0%) 37 (74.0%) Female 11 (22.0%) 13 (26.0%) Age (years) <40 13 (26.0%) 14 (28.0%) 40–49 25 (50.0%) 21 (42.0%) P50 12 (24.0%) 15 (30.0%) Education Primary 10 (20.0%) 10 (20.0%)

Junior high school 9 (18.0%) 5 (1.0%)

Senior high school 11 (22.0%) 17 (34.0%)

College or above 16 (32.0%) 16 (32.0%)

Major language

Mandarin 35 (70.0%) 38 (76.0%)

Taiwanese 33 (66.0%) 32 (64.0%)

Hakka 4 (8.0%) 3 (6.0%)

Table 2. Test–retest reliability and internal consistency ofthe EORTC QLQ-C30 and the EORTC QLQ-H&N35

Test–retest reliability

Internal consistency

Follow-up group All patients

QLQ-C30 Scales Intraclass correlation coefficients Cronbach’s a Physical functioning 0.75 0.75 Role functioning 0.56 0.85 Emotional functioning 0.54 0.90 Cognitive functioning 0.77 0.51 Social functioning 0.33 0.86 Quality oflife 0.82 0.82 Pain 0.67 0.76

Nausea and vomiting 0.53 0.86

Fatigue 0.56 0.77 Single items j Dyspnea 0.63 – Sleep disturbance 0.58 – Appetite 0.37 – Constipation 0.66 – Diarrhea 0.66 – Financial difficulty 0.51 – QLQ-H&N35 Scales Pain 0.83 0.83 Swallowing 0.76 0.78 Senses 0.71 0.78 Speech 0.80 0.75 Social eating 0.73 0.89 Social contact 0.77 0.84 Sexuality 0.58 0.92 Single items j Teeth 0.47 – Opening mouth 0.38 – Dry mouth 0.56 – Sticky saliva 0.41 – Coughing 0.59 – Feeling ill 0.40 – Analgesics 0.70 – Nutritional supplement 0.62 – Feeding tube – – Weight loss 0.68 – Weight gain 1.00 –

Cronbach’s a coefficients for scales of the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-H&N35 were P0:70 except for cognitive functioning (0.51) (Table 2).

Most scales ofthe QLQ-C30 were highly or moderately correlated with the scales measuring similar dimensions in the SF-36 (|r|¼ 0:47–0:74). Scales ofthe QLQ-H&N35 were only moderately correlated with similar scales ofthe QLQ-C30 and the SF-36 (|r| = 0.40–0.49).

Patients in the follow-up group had better scores than those in the active treatment group for role functioning, global status/quality of life, nausea and vomiting, appetite loss, and constipation (Table 3). More patients in the active treatment group used analgesics and had weight loss, while patients in the follow-up group had more serious problems in swallowing, speech, ofteeth problem, opening mouth, dry mouth, and sticky saliva (Table 4).

Discussion

Lower test–retest correlations for scores in some scales/single items ofthe QLQ-C30 (most were below 0.70) was found in this study than in the study ofHjermstad et al. [5]. Four days [5] might be too short for patients to wash out memories in

the first interview. It is also possible that some ofthe patients’ conditions changed in 2 weeks although we had assumed that their conditions should be stable across time.

The internal consistency coefficients ofmost scales ofthe QLQ-C30 were satisfactory except that ofcognitive functioning, consistent with the findings ofprevious studies [4, 7, 8, 11, 13]. The internal consistency coefficients ofall scales in the QLQ-H&N35 were also satisfactory, consis-tent with previous studies [9–11].

The Taiwan Standard version 1.0 ofSF-36 has been proven to have good reliability and validity [16–19]. Therefore, the moderate to high correla-tion between scales measuring similar scales ofthe QLQ-C30 and the SF-36 implied that the validity ofthe QLQ-C30 is also satisfactory. The moderate correlation between scales ofthe QLQ-H&N35 with similar dimensions with the QLQ-C30 was consistent with previous studies, and implied that these scales measure different problems [9–11].

The scores ofmost scales ofthe QLQ-C30 ofthe follow-up group were similar to the reference val-ues ofall head and neck cancers, stage III/IV, and pharynx cancer [22], the disease-free patients in the 12-country study [9] but better than the scores ofthe American study [11]. However, the social functioning scale scores of the QLQ-C30 and most

Table 3. Comparison ofquality oflife scores in the EORTC QLQ-C30 among two groups ofpatients

Active treatment Follow-up p-Value

Mean ± SD Mean ± SD

Scales Wilcoxon’s rank sum test

Physical functioning 82.6 ± 14.3 88.5 ± 10.3 0.0658 Role functioning 71.7 ± 25.0 88.0 ± 14.7 0.0003* Emotional functioning 76.0 ± 20.7 78.0 ± 19.3 0.7650 Cognitive functioning 81.3 ± 18.0 81.3 ± 17.4 0.9138 Social functioning 66.3 ± 23.2 69.7 ± 21.7 0.7082 Quality oflife 60.0 ± 18.7 71.5 ± 18.6 0.0022* Fatiguea 37.3 ± 19.1 28.0 ± 14.2 0.0030* Nausea/vomitinga 43.3 ± 25.0 6.0 ± 11.5 0.0001* Paina 23.3 ± 22.1 18.7 ± 17.7 0.3371

Single items Cochran Mantel–Haenszel test

Dyspneaa 11.3 ± 17.3 7.3 ± 13.9 0.205 Sleep disturbancea 24.7 ± 26.8 22.7 ± 20.7 0.675 Appetite lossa 42.7 ± 27.8 14.7 ± 25.3 0.001* Constipationa 22.0 ± 22.9 12.0 ± 19.9 0.023* Diarrheaa 14.7 ± 16.7 8.7 ± 16.2 0.072 Financial difficultya 22.7 ± 28.1 27.3 ± 32.8 0.444 * p < 0:05.

scales ofthe QLQ-H&N35 ofthe follow-up group ofthis study indicated more serious problems compared with previous studies [9–11]. It is pos-sible that NPC patients have more chronic or late complications ofradiation. Like known group comparison in other studies [8–11], we observed significant differences between the two groups for most scales/single items ofthe two questionnaires. In the active treatment group, the major problems were symptoms ofdisease and acute toxic effects of chemotherapy, while in the follow-up group, the late effect ofradiation appeared gradually. These findings are consistent with our hypothesis for known group selection.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a research grant of the National Science Council, Taiwan, no. NSC89-2314-B002-469 and no. NSC89-2320-B-002-096. The authors ofthis study are grateful to Ms Karen West ofthe EORTC for helps in translation re-view, Drs Chih-Hsin Yang and Chiun Hsu, Mr

Wei-Hua Tan and Mr Jui-Ming Shih for transla-tion, Professor Jen-Pei Liu for statistical consul-tation, and Mr Ming-Jer Chang for data collection.

References

1. Cheng YJ, Hildesheim A, Hsu MM, et al. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and risk ofnasopharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer Causes Control 1999; 10: 201–207.

2. Department ofHealth, the Executive Yuan. Cancer Reg-istry Annual Report, Republic ofChina, 1997. Taipei: Department ofHealth. 2000; 20–21.

3. Division ofCancer Research, National Health Research Institutes and Taiwan Cooperative Organization ofCancer. Consensus ofDiagnosis and Treatment ofNasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Taipei: National Health Research Institutes, 2000.

4. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai A, Berman B, et al. The Euro-pean Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in interna-tional clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85: 365–376.

5. Hjermstad MJ, Fossa SD, Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Test/retest study ofthe European Organization for Research and Table 4. Comparison ofquality oflife scores in the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 among two groups ofpatients

Active treatment Follow-up p-Value

Mean ± SD Mean ± SD

Scalesa Wilcoxon’s rank sum test

Pain 13.5 ± 16.2 17.3 ± 17.7 0.1487 Swallowing 9.3 ± 12.2 25.0 ± 18.3 0.0001* Senses 20.3 ± 18.5 24.0 ± 25.7 0.7481 Speech 10.4 ± 11.8 18.7 ± 21.9 0.0368* Social eating 25.5 ± 20.6 22.8 ± 22.8 0.1936 Social contact 17.5 ± 17.1 13.9 ± 16.8 0.1974 Sexuality 31.3 ± 26.9 25.0 ± 30.4 0.0968

Single itemsa Cochran Mantel–Haenszel test

Teeth 24.0 ± 25.2 38.0 ± 26.1 0.008* Opening mouth 12.0 ± 22.1 31.3 ± 27.3 0.001* Dry mouth 27.3 ± 18.7 63.3 ± 28.8 0.001* Sticky saliva 22.7 ± 18.4 59.3 ± 28.8 0.001* Coughing 23.3 ± 19.3 24.7 ± 22.1 0.747 Feeling ill 32.0 ± 22.3 26.0 ± 23.6 0.193

Binary items Present (%) Present (%) v2test

Analgesics 17 (34.0%) 8 (16.0%) 0.038*

Nutritional supp. 24 (48.0%) 16 (32.0%) 0.102

Feeding tube 0 ( 0.0%) 2 ( 4.0%) –

Weight loss 28 (56.0%) 18 (36.0%) 0.045*

Weight gain 17 (34.0%) 26 (52.0%) 0.069

Treatment ofCancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 1249–1254.

6. Groenvold M, Klee MC, Sprangers MAG, Aaronson NK. Validation ofthe EORTC QLQ-C30 quality oflife ques-tionnaire through combined qualitative and quantitative assessment ofpatient-observer agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50: 441–450.

7. Kobayashi K, Takeda F, Teramukai S, et al. A cross-vali-dation ofthe European Organization for Research and

Treatment ofCancer QLQ-C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) for

Japanese with lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34: 810–815. 8. Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Psychometric validation ofthe EORTC Core Quality ofLife Questionnaire, 30-item ver-sion and a diagnosis-specific module for head and neck cancer patients. Acta Oncol 1992; 31: 311–321.

9. Bjordal K, Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, et al. Quality oflife in head and neck cancer patients: Validation ofthe European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality ofLife Questionnaire-H&N35. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 1008–1019.

10. Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers PM, et al. A 12 country field study ofthe EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. Eur J Cancer 2000; 36: 1796–1807. 11. Sherman AC, Simonton S, Adams DC, Vural E, Owens B, Hanna E. Assessing quality oflife in patients with head and neck cancer, cross-validation ofthe European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality ofLife Head and Neck Module (QLQ-H&N35). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000; 126: 459–467. 12. EORTC quality of Life Study Group. Questionnaire for the

Department ofObstetric and gynecology, Hong Kong University (Chinese Translation ofthe EORTC QLQ-C30 version 2.0). Brussels: Quality ofLife Unit, EORTC Data Center, 1997.

13. Cull A, Sprangers M, Bjordal K, et al. EORTC Quality ofLife Study Group Translation Procedure. Brussels: EORTC Quality ofLife Study Group, 1998.

14. New England Medical Center Hospital. IQOLA SF-36 Taiwan Standard Version 1.0. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1996.

15. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1994. 16. Chie WC, Huang CS, Chen JH, Chang KJ. Measurement ofthe quality oflife during different clinical phases of breast cancer. J Formos Med Assoc 1999; 98: 254–260. 17. Fuh JL, Wang SJ, Lu SR, Juang KD, Lee SJ. Psychometric

evaluation ofa Chinese (Taiwanese) Version ofthe SF-36 Health Survey amongst middle-aged women from a rural community. Qual Life Res 2000; 9: 675–683.

18. Chiu HC, Chern JY, Shi HY, Chen SH, Chang JK. Phy-sical functioning and health-related quality of life: Before and after total hip replacement. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2000; 16: 285–292.

19. Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Juang KD. Quality oflife differs among headache diagnoses: Analysis ofSF-36 survey in 901 headache patients. Pain 2001; 89: 285–292.

20. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Reliability, in Streiner DL, Norman GR (eds): Health Measurement Scales. A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. Oxford: Oxford Medical, 1994; 79–96.

21. Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, Curran D, Groenvold M: EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 2nd ed. Brussels: EORTC Quality ofLife Study Group, 1999.

22. Fayers P, Weeden S, Curran D. EORTC QLQ-C30 Ref-erence Values. Brussels: EORTC Quality ofLife Study Group, 1998.

Address for correspondence: Wei-Chu Chie, School ofPublic Health and Graduate Institute ofPreventive Medicine, College ofPublic Health, National Taiwan University, Room 209, 19 Hsuchow Road, Taipei 10020, Taiwan

Phone: +886-2-23920460; Fax: +886-2-23920456 E-mail: weichu@episerv.cph.ntu.edu.tw