Comparison of the Monetary Reward Decision

of Taiwan and U.S. Managers:

Allocation Context as a Moderator

Hsiu-Hua Hu Kuo-Long Huang

Ming-Chuan University Shih Chien University

R.O.C. R.O.C.

Shu-Cheng Chi Chen-Ming Chu

National Taiwan University Chung Yuan Christian University

R.O.C. R.O.C.

Abstract

This study examines the effects of the affect, loyalty, and contribution factors of the manager-subordinate exchange relationship on the monetary reward decision. It also an-alyzes the moderated effects of nations (Taiwan and the U.S.) and the reward allocation context (private and public) on these three factors and the monetary reward decision. The study uses a 2 × 2 × 2 scenario experiment design to examine the effects of perspective. Total valid samples were received from 224 Taiwan and 152 U.S. managers regarding their reward allocation choices under a simulated situation involving eight types of employee. The results indicate that, regardless of a public or private context, Taiwan managers allocate more monetary rewards to subordinates with a closer affective relationship, whereas U.S. managers place more emphasis on their subordinates’ work contribution. The limitations of the research are discussed and suggestions for further research proposed.

Keywords: Affect, Loyalty, Contribution, Monetary Reward Decision, Allocation Con-text.

1. Introduction

Reward allocation is an important managerial issue, in particular the manager’s role in deciding a subordinate’s level of salary adjustment, bonus distribution, and other human resource related activities (Chen and Chang (1996), Chen and Pai (1997) and Rousseau (1997)). Numerous factors influence the reward allocation decision and are largely subject

Received August 2005; Revised January 2006; Accepted June 2006. Supported by ours.

to the attitude of the manager (reward distributor). Based on the principle of fairness, research has shown that the reward distributor will focus on the relationship between the input and output of the subordinate (reward recipient), which in turn is based on the individual’s competence, efforts, or performance (Carrell and Dittrich (1978), Chen and Chang (1996), Hu, Hsu and Cheng (2004), Kiker and Motowidlo (1999) and Walster, Berscheid and Walster (1973)). Other influential factors include friendship, social dis-tance (Shapiro (1975)), attitude similarity (Baskett (1973)), the interactive relationship between reward distributor and recipient (Zhou and Martocchio (2001)), and the antic-ipation of both parties’ future social interaction (Shapiro (1975) and von Grumbkow, Deen, Steensma and Wilke (1976)).

The Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory suggests that managers treat subordi-nates in different ways. In other words, managers establish different exchange relation-ships with different subordinates (Graen (1976) and Graen and Cashman (1975)). Such an exchange relationship is based on emotional support and exchange resources (Graen and Scandura (1987)). One of the key resources that influence the exchange relationship is rewards. This means that, given time and effort constraints, managers differentiate subordinates into in-group and out-group members, and reward subordinates differen-tially (Graen and Cashman (1975)).

Dienesch and Liden (1986) developed a three dimensional conceptualization of the exchange relationship between supervisors and subordinates, based on the definition of ‘mutuality’ that underpins social exchange theory, and concluded that three factors −affect, loyalty, and the perceived contribution to the exchange−are used by managers to categorize their subordinates and the ways in which they interact with different types of subordinates. The three factors are defined as follows (Dienesch and Liden (1986, p624-625)):

“Affect−the mutual affection members of the dyad have for each other based primarily on interpersonal attraction rather than work or professional values; Loyalty −the expression of public support for the goals and the personal charac-ter of the other member of the LMX dyad; and; Perceived contribution to the exchange−perception of the amount, direction, and quality of work-oriented activity each member puts forth toward the mutual goals (explicit or implicit) of the dyad.”

Increasing corporate globalization has also prompted much research on the comparison of national culture and managerial decision-making traits (Chen (1995), Earley (1989, 1994), Hofstede (1993), Kim, Park and Suzuki (1990), Leung and Bond (1984) and Zhou and Martocchio (2001)), and on differences in management style between Chinese and Western organizations (Cheng (1993, 1995), Redding (1990), Yang (1995) and Westwood (1997)).

Research has found that reward allocation decision will vary for different national cultures characterized by collectivism and individualism (Bond, Leung and Wan (1982), Hui, Triandis and Yee (1991), Kim, Park and Suzuki (1990) and Leung and d Bond (1984)). Chinese society (Taiwan for the purpose of this study) is characterized by a high degree of collectivism, while Western society (the U.S. for the purpose of this study) is characterized by high degree of individualism (Earley (1993), Ho (1976), Hsu (1971), Hui, Triandis and Yee (1991), Suh, Diener, Oishi and Triandis (1998) and Triandis (1989)).

This study will examine whether there are any significant differences between Taiwan and U.S. corporate managers regarding the influence of the affect, loyalty and contribu-tion variables on the reward allocacontribu-tion decision, and also study the interaccontribu-tion of these three factors and the allocation context (private vs. public) for a more full understanding of allocation behavior in different nations.

2. Chinese and Western Cultural Values

Zhou and Martocchio (2001) pointed to the significance of the quality of the rela-tionship between the manager and subordinate in the reward allocation process. Prior research has generally assumed that Western society is characterized by individualism, whereas Chinese society is characterized by collectivism and places more emphasis on the value of maintaining a good relationship with the manager (Hofstede and Bond (1988), Redding and Wong (1986) and Zhou and Martocchio (2001)).

In a society characterized by collectivism, the manager is more concerned about close interpersonal relationship and interactive effects, whereas in a society characterized by individualism, the manager tends to focus on the subordinate’s contribution to the orga-nization (Bond, Leung and Wan (1982), Hui, Triandis and Yee (1991) and Kim, Park and Suzuki (1990)). Subordinates in Taiwan companies, which for the purpose of this study represent Chinese cultural values and possess collectivist characteristics, are expected to maintain good interactive relationships with their manager. Hence, subordinates with a

good affect can be expected to obtain more rewards (Redding and Wong (1986)). On the other hand, subordinates in U.S. companies, which represent Western cultural val-ues and possess individualistic characteristics, are considered independent individuals whose achievement and uniqueness are the key focus of the reward allocation decision. Therefore, this study assumes that:

H 1: There is a significant difference between Taiwan and U.S. managers re-garding the effect of the affect variable on the monetary reward (salary in-crease and bonus distribution) allocation decision: Taiwan managers will allo-cate more rewards to subordinates with close affect than U.S. managers.

The interpretation of “loyalty” differs between the East and West and. In terms of national culture, Western society places more emphasis on identification and internaliza-tion (O’Reilly and Chatman (1986)), which is defined by Dienesch and Liden (1986) as “the expression of public support for the goals and the personal character of the other member of the LMX dyad” (p.625). Chinese research has shown that loyalty to the manager not only means identification and internalization, but also sacrifice and devo-tion to the manager, business support, absolute obedience, and aggressive cooperadevo-tion (Cheng and Jiang (2001)). In a highly individualistic society such as the U.S., individual achievements, innovation and independence are more highly valued (Chang (2003)), such that a subordinate possessing high competence will have a better chance of earning a higher reward.

Zhou and Martocchio (2001) viewed the interactive relationship between manager and subordinate as the most important criteria for the Chinese manager in the reward allo-cation decision. The interactive relationship includes affect and role obligation, which is mainly characterized by loyalty in terms of the subordinate’s concurrence with the manager and his willingness to stand up in public and support the manager’s working concept (Dienesch and Liden (1986)) or actively take responsibility for the manager’s mistakes. Furthermore, Silin (1976) and Redding (1990) also pointed out that the Chi-nese companies possess a unique business operational mode and cultural background, where loyalty is deemed a very important value norm.

For organizations possessing individualistic characteristics, the subordinate will pur-sue and protect his self-interest and benefits. In this case, the manager places emphasis on the subordinates’ self-efficiency, performance and contribution to the organization as

the key criteria for reward allocation (Gomez-Mejia and Welbourne (1991)). For orga-nizations possessing collectivist characteristics, the manager considesr the subordinates’ loyalty more important than work efficiency (Adler (1990) and Muna (1980)). In other words, if the manager holds the reward resources and controls the allocation process, the Taiwan manager is more concerned about the subordinate’s loyalty than the U.S. manager. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H 2: There is a significant difference between Taiwan and U.S. managers re-garding the effect of the loyalty variable on the monetary reward (salary in-crease and bonus distribution) allocation decision: Taiwan managers will allo-cate more rewards to subordinates with high loyalty than U.S. managers.

A subordinate’s performance and work contribution also have a positive influence on the reward allocation decision (Deshpande and Schoderbek (1993), Fossum and Fitch (1985), Sherer, Schwab and d Heneman (1987) and Zhou and Martocchio (2001)). Zhou and Martocchio (2001) showed that U.S. managers, unlike their Chinese counterpart, place more emphasis on a subordinate’s performance when setting their reward allocation policy. In a collectivist society, the importance of intra-group harmony and cooperation is emphasized; implying that Chinese managers believe organizational success is based on overall teamwork, and hence pay less attention to individual performance. In an individualistic society, the manager holding reward resources is more likely to focus on a subordinate’s performance and contribution to the organization. Therefore, this study assumes that:

H 3: There is a significant difference between Taiwan and U.S. managers re-garding the effect of the contribution variable on the monetary reward (salary increases and bonus distribution) allocation decision: U.S. managers will al-locate more rewards to subordinates with high contribution than Taiwan man-agers.

3. Exchange Relationship, Allocation Contexts and Reward Decisions

The issue of fairness and social justice is another consideration in the reward alloca-tion decision. Prior research on human distributive behavior showed that such allocaalloca-tions are associated with distributive justice (Adams (1965), Leventhal and Michaeles (1969) and Walster, Berscheid and Walster (1973)). For managers, the key point of the reward

allocation decision is “to reward whomever deserves it” in order to motivate their sub-ordinates’ work behavior. From the viewpoint of employee categorization, the manager dictates the subordinate’s ranking and reward share. After the allocation, the manager has to face potential questions from subordinates about the fairness of the decision. Eq-uity theory assumed that cognition of the fairness of an individual’s reward is generated through comparison of one’s efforts and outputs with those of others (Adams (1965)).

There are two types of reward in the organizational context: monetary (salary in-creases and bonus distribution) and non-monetary (job promotion, important task as-signments, participation in decision-making, and public recognition). Monetary reward are generally made under a confidential pay policy (private context) and non-monetary rewards under a non-confidential policy (public context). The monetary reward alloca-tion may be done privately (i.e., subordinates do not know the reward amounts allo-cated to their colleagues) or publicly (i.e., subordinates are unlikely to know the reward amounts allocated to their colleagues, but may possibly know the upper reward limit). It follows that if the monetary reward is allocated publicly, then the subordinates have a comparative benchmark and so questions of fairness and social justice may arise.

Research on private reward allocations showed that secrecy will affect the subordi-nate’s awareness of the reward allocated to other colleagues, and also affect his percep-tion of justice and satisfacpercep-tion regarding his compensapercep-tion (Kidder, Bellettirie and Cohen (1977) and Leventhal, Michaeles and Sanford (1972) and Reis and Gruzen (1976)). In-deed, the reward distributor is unlikely to follow the norms of justice and may be more discrimanory in allocating rewards, especially under a confidential pay policy. But for a public reward allocation, the reward distributor is more likely to fairly allocate the reward based on the recipient’s work performance (Freedman and Montanari (1980) and Leung and Bond (1984)).

Hu, Hsu and Cheng (2004) found that subordinates with a close relationship to the allocator, high loyalty, or high competence were rewarded more. Significant two-way interaction effects indicated that relationship, loyalty, and competence influenced the reward allocation decisions of Chinese managers. In addition, the moderating effects of allocation context on these three factors were also found to be significant. This means that an interactive relationship exists between the allocation context and the manager’s employee categorization criteria. In other words, if the allocation context is public, the manager is unlikely to favor certain subordinates−insiders who are close, loyal, or competent, and have a high employee categorization ranking−because of fairness and

social justice concerns. As a result, managers need to consider the issue of fairness in the reward allocation decision, even though it is primarily his interaction with the subordinate that dictates the final decision. Therefore, this study assumes that:

H 4: The effects of affect, loyalty or contribution will be moderated by the allocation context. The effects of affect, loyalty or contribution on the mon-etary reward (salary increases and bonus distribution) allocation decision will be greater in a private context than in a public context.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research participants

The sample for this study consists of Taiwan and U.S. managers who are responsible for and have experience of making reward allocation decisions in banking, high-tech, consumer products, petrochemical and chemical, and pharmaceutical industries. The demographical backgrounds of the Taiwan and U.S. subjects (such as gender, education, and work tenure) were made as comparable as possible.

The Taiwan sample includes 224 professional managers of small and medium-size enterprises island-wide. By gender, 42% were male and 58% female. Respondents ranged in age from 35 to 55 years, and 45% were over than 41 years old. In terms of education, 63% had at least a bachelor’s degree. As regards tenure, 52% had over seven years’ work experience.

The U.S. sample (which excludes U.S.-born Chinese people) includes 152 managers of small- and mid-size companies in Silicon Valley, San Jose, as well as EMBA working students from California State University, Fresno and Pace University, New York. By gender, 57% were male and 43% female. Respondents ranged in age from 31 to 60 years and 74% were over 41 years old. In terms of education, 81% held at least a bachelor’s degree. As regards the tenure, 43% had over seven years work experience.

4.2. Research design and process

This study used a scenario experiment design, derived from Hammond’s (1955) “policy capturing approach”, which allowed the survey subjects to demonstrate whether or not the three exchange relationship factors of affect, loyalty and contribution influence the reward allocation decision. Before designing the research, four experienced managers from Taiwan and the U.S. were interviewed to identify the predominant types of monetary

reward allocation, namely salary adjustment and bonus distribution, and the factors influencing reward decisions.

The methodology of Van de Vijver and Leung (1997) was used for cross-national comparisons, in which questionnaires are developed in different languages. The original script and reward questions were developed in Chinese and then translated into English, with a native English speaker, who also understood Chinese, editing the grammar and checking the content, and then back translating to Chinese (Brislin (1970)).

After the pilot interviews, a scenario script and reward questionnaire were developed and given to ten Taiwan and U.S. managers to check whether all the manipulations were realistic and whether all subjects understood the instructions and the purpose of the study. The questionnaires were mailed to 700 managers, who did not participate in the initial interviews and pilot tests, asking them to complete an anonymous survey regarding reward allocation decisions. A total of 376 valid questionnaires were returned, i.e., a 53.7% response rate.

The scenario script described the role (the reward distributor) of a department man-ager in a company with eight subordinates (see Appendix). A script was designed for each subordinate based a combination of the affect (close vs. distant), loyalty (high vs. low), and contribution (high vs. low) factors as derived from Dienesch and Liden (1986). Chang and Lin (1985) showed that the eight different types of subordinates do exist in an actual working environment, except for a subordinate with a distant relationship, low loyalty, and poor competency.

An experimental design, including both within-subjects and between-subjects compo-nents, was used. For the convenience of the survey subject, there was only one script per page, including questions on the monetary reward allocation decision and one allocation context (private or public). The order of the eight profiles was randomly arranged, as were the public and private allocation contexts in order to minimize any ordering effect. A total of sixteen scripts were designed for the two reward allocation contexts.

To investigate the manipulation validity of the scenario script, three checkpoints−based on the LMX measurement scales of Graen, Novak and Summerkamp (1982) and Liden and Maslyn (1998)−were added to check for manipulation by affect (“You are able to share your feelings with the subordinate.”), loyalty (“The subordinate will work for you and express business support in public.”), and contribution (“There is no doubt about the subordinate’s execution ability based on hisnate’s previous performance,.”). The survey subjects answered using a Likert 6 point scale (1 =strongly disagree; 6 =strongly agree).

To investigate the validity of cross-national differences between Taiwan and U.S. managers, “independent self-construal” and “interdependent self-construal” sacles− developed by Singelis and Sharkey (1995), and Gudykunst et al (1996)−were used. Ten items were posed and measured on Likert 6-point scales (1 =strongly disagree; 6 =strongly agree).

Potential managers were visited to briefly explain the purpose of the study and to as-sure them about the data confidentiality. A questionnaire was issued to managers willing to answer questions (see below) about the reward allocation decision (including salary adjustment and bonus distribution) for eight types of subordinates under a simulated context (public or private). The respondent, in the role of the manager, also answered questions about the “independent self-construal” and “interdependent self-construal” scales, and filled out their personal background information. The questionnaires were directly collected from the manager after completion.

Annual Salary Adjustment Question: “Your department proceeds to increase staff salaries, with an individual upper limit of 10% and a different adjustment rate for each subordinate. Each subordinate knows (or does not know) the upper limit, does not know the final result of the other subordinate’s increase amount. How much percentage increase would you give the subordinate?” (The survey subject could only make one choice from: 0% to 10%.)

Bonus Distribution Question: “Your department proceeds to distribute staff bonuses, with an individual upper limit of 10% of base salary and a different distribution rate for each subordinate. Each subordinate knows (or does not know) the upper limit, does not know the final result of the other subordinate’s bonus. How much percentage distribution of a bonus do you give the subordinate?” (The survey subject could only make one choice from: 0% to 10%.)

5. Results

5.1. Validity of manipulation checks

T-test was used to check the manipulation validity of the scenario scripts for the Taiwan and U.S. samples. First, the results showed a significant difference for the Taiwan and U.S. samples regarding close affect and distant affect, respectively (Taiwan: t = 78.79, p < .001, Mclose = 19.24, SD = 1.81; Mdistant = 7.21, SD = 1.51; U.S.: t = 62.55,

p < .001, Mclose = 19.28, SD = 1.87; Mdistant = 7.33, SD = 1.53). Second, the results

showed a significant difference for the Taiwan and U.S. samples regarding high loyalty and low loyalty, respectively (Taiwanese: t = 91.31, p < .001, Mhigh= 19.79, SD = 1.34;

Mlow = 7.11, SD = 1.43; U.S.: t = 63.02, p < .001, Mhigh = 19.80, SD = 1.38;

Mlow = 7.57, SD = 1.81). Third, the results showed a significant for the Taiwan and

U.S. samples regarding high contribution and low contribution, respectively (Taiwanese: t = 118.43, p < .001, Mhigh = 21.44, SD = 1.47; Mlow == 7.44, SD = 1.18; U.S.:

t= 99.66, p < .001, Mhigh= 21.38, SD = 1.43; Mlow = 7.43, SD = 1.21).

5.2. Validity of Cross-Cultural differentiation checks

To examine for cross-national differences between the Taiwan and U.S. samples, in-dependent self-construal and interin-dependent self-construal scales were used. After factor analysis, one factor was extracted from the independent self-construal scale, accounting for 61.6% of the total variance and a reliability coefficient of 0.84. One factor was also extracted from the interdependent self-construal scale, accounting for 43.4% of the total variance and a reliability coefficient of 0.69. The difference between the independent self-construal scores (t = −46.43, p < .001, Taiwanese: Mindependent= 16.88, SD = 1.14;

U.S.: Mindependent = 24.54, SD = 2.04), with the U.S. sample score significantly higher

than the Taiwan score. The difference between the interdependent self-construal scores of the Taiwan and U.S. samples was also significant (t = 25.13, p < .001, Taiwanese: Minterdependent = 25.34, SD = 1.38; U.S.: Minterdependent = 21.13, SD = 1.87), with

the Taiwan score significantly higher than the U.S. score. In sum, these results indicated significant differences between the Taiwan and the U.S. samples, which can be attributed in part to national cultural differentiation.

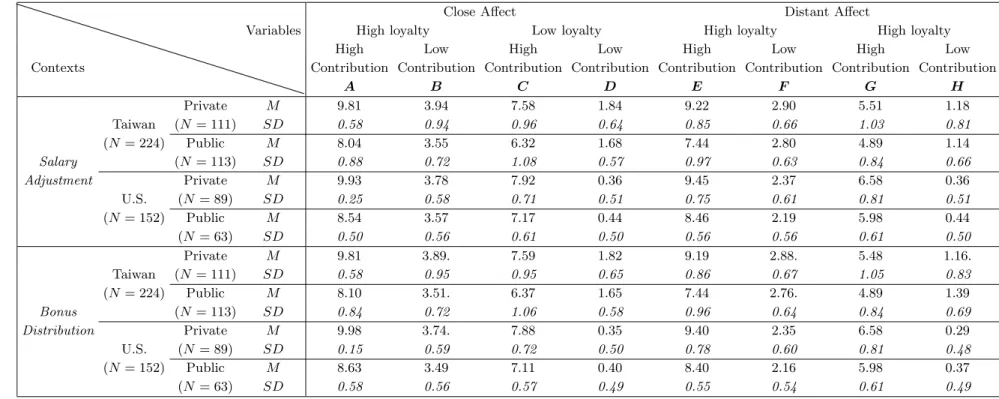

5.3. Effects of exchange relationship on monetary reward decisions

The means and standard deviations for the monetary reward (salary adjustment and bonus distribution) allocation decision for each of the eight subordinates in the two allocation contexts for the Taiwan and U.S. samples are shown in Table 1. The results show that the order of the monetary reward allocation decision was: A > E > C > G > B > F > D > H. The means presented in Table 1 also show that the effect of the contribution variable on the manager’s monetary reward allocation decision is consistent. In other words, subordinates who made a higher contribution received a larger annual salary adjustment rate than the midpoint (i.e., 5%, with the lowest rate 0% and the

C o m p a ri so n o f th e M o n e ta ry R e w a rd D e c is io n o f T a iw a n a n d U .S . M a n a g e rs

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of exchange relationship, allocation context, and Nation.

Close Affect Distant Affect

Variables High loyalty Low loyalty High loyalty High loyalty

High Low High Low High Low High Low

Contexts Contribution Contribution Contribution Contribution Contribution Contribution Contribution Contribution

A B C D E F G H Private M 9.81 3.94 7.58 1.84 9.22 2.90 5.51 1.18 Taiwan (N = 111) SD 0.58 0.94 0.96 0.64 0.85 0.66 1.03 0.81 (N = 224) Public M 8.04 3.55 6.32 1.68 7.44 2.80 4.89 1.14 Salary (N = 113) SD 0.88 0.72 1.08 0.57 0.97 0.63 0.84 0.66 Adjustment Private M 9.93 3.78 7.92 0.36 9.45 2.37 6.58 0.36 U.S. (N = 89) SD 0.25 0.58 0.71 0.51 0.75 0.61 0.81 0.51 (N = 152) Public M 8.54 3.57 7.17 0.44 8.46 2.19 5.98 0.44 (N = 63) SD 0.50 0.56 0.61 0.50 0.56 0.56 0.61 0.50 Private M 9.81 3.89. 7.59 1.82 9.19 2.88. 5.48 1.16. Taiwan (N = 111) SD 0.58 0.95 0.95 0.65 0.86 0.67 1.05 0.83 (N = 224) Public M 8.10 3.51. 6.37 1.65 7.44 2.76. 4.89 1.39 Bonus (N = 113) SD 0.84 0.72 1.06 0.58 0.96 0.64 0.84 0.69 Distribution Private M 9.98 3.74. 7.88 0.35 9.40 2.35 6.58 0.29 U.S. (N = 89) SD 0.15 0.59 0.72 0.50 0.78 0.60 0.81 0.48 (N = 152) Public M 8.63 3.49 7.11 0.40 8.40 2.16 5.98 0.37 (N = 63) SD 0.58 0.56 0.57 0.49 0.55 0.54 0.61 0.49

highest 10%) and a higher bonus distribution rate than the midpoint (i.e., 5%, with the lowest rate 0% and the highest 10%), regardless of the level of their affect and loyalty with the manager. On the other hand, subordinates who made a smaller contribution received a lower annual salary adjustment rate than the midpoint (i.e., 5%) and a lower bonus distribution rate than the midpoint (i.e., 5%).

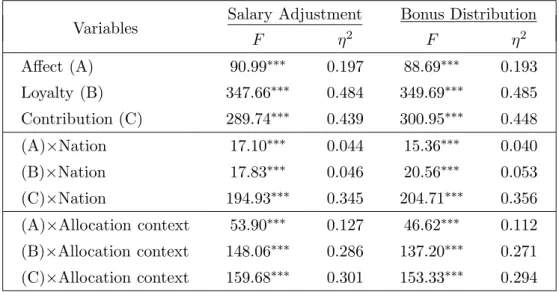

As this study used a three-factor complete within-subjects design, GLM with repeated measures ANCOVA was used to test the study’s four hypotheses, using the individual’s gender, age, tenure, and educational level as control variables. The results presented in Table 2 show that the main effects of the affect, loyalty and contribution variables on the monetary reward the monetary reward allocation decision were also found to be significant.

Table 2. Results of repeated measure of GLM of affect, loyalty, contribution, allocation context, and nation.

Salary Adjustment Bonus Distribution Variables F η2 F η2 Affect (A) 90.99∗∗∗ 0.197 88.69∗∗∗ 0.193 Loyalty (B) 347.66∗∗∗ 0.484 349.69∗∗∗ 0.485 Contribution (C) 289.74∗∗∗ 0.439 300.95∗∗∗ 0.448 (A)×Nation 17.10∗∗∗ 0.044 15.36∗∗∗ 0.040 (B)×Nation 17.83∗∗∗ 0.046 20.56∗∗∗ 0.053 (C)×Nation 194.93∗∗∗ 0.345 204.71∗∗∗ 0.356 (A)×Allocation context 53.90∗∗∗ 0.127 46.62∗∗∗ 0.112 (B)×Allocation context 148.06∗∗∗ 0.286 137.20∗∗∗ 0.271 (C)×Allocation context 159.68∗∗∗ 0.301 153.33∗∗∗ 0.294

Note: η2 meant effect size;∗ p <0.05; ∗∗ p <0.01; ∗∗∗ p <0.001.

5.4. Effects of nation on exchange relationship and reward decisions

Table 2 shows that the interaction effects between the affect factor and national cul-ture were statistically significant for monetary rewards. There were significant differences between Taiwan and U.S. managers when deciding annual salary adjustments and bonus distributions based on their view of the subordinate’s level of affect. The gap between the Taiwan manager’s salary adjustment for a close affect subordinate and a distant affect subordinate was larger than for the U.S. manager (0.92 for the Taiwan manager and 0.74

for the U.S. manager), and the gap between the Taiwan manager’s bonus allocation for a close affect subordinate and a distant affect subordinate was larger than for the U.S. manager (0.94 for the Taiwan manager and 0.77 for the U.S. manager). Therefore, H1 was supported.

The interaction effects between the loyalty factor and national culture were statisti-cally significant for monetary rewards. Thee were significant differences between Taiwan and U.S. managers when deciding annual salary adjustments and bonus distributions based on their view of the subordinate’s level of loyalty. The gap between the U.S. man-ager’s salary adjustment for a high loyalty subordinate and a low loyalty subordinate was larger than for the Taiwan manager (2.42 for the U.S. manager and 2.16 for the Tai-wan manager), and the gap between U.S. manager’s bonus allocation for a high loyalty subordinate and a low loyalty subordinate was larger than for the Taiwan manager (2.43 for the U.S. manager and 2.16 for the Taiwan manager). The result contradicted H2 and so the hypothesis was not supported.

The simple interaction effects between the contribution factor and national culture were statistically significant for monetary rewards. There were significant differences between Taiwan and U.S. managers when deciding annual salary adjustments and bonus distributions based on their view of subordinate’s level of contribution. The gap between the U.S. managers’ salary adjustment for a high contribution subordinate and a low contribution subordinate was larger than for the Taiwan manager (6.40 for the U.S. manager and 4.92 for the Taiwan manager, and the gap between the U.S. managers’ bonus allocation for a high contribution subordinate and a low contribution subordinate was larger than for the Taiwan manager (as 6.43 for the U.S. manager and 4.97 for the Taiwanese manager). Therefore, H3 was supported.

5.5. Effects of allocation contexts on exchange relationship and reward deci-sions

Regarding annual salary adjustment decision, Table 2 shows that the interactive ef-fects were significant for the relationship between the two reward allocation contexts and the three exchange relationship factors. There were significant differences between the private and public allocation contexts when the manager decides the annual salary ad-justment based on their view of the subordinate’s level of affect, loyalty and contribution. In terms of of affect, the gap between the manager’s salary adjustment for a close affect subordinate and a distant affect subordinate was larger under the private context

compared with the public context (0.96 under the private context and 0.73 under the public context). In terms of loyalty, the gap between the manager’s salary adjustment for a high loyalty subordinate and a low loyalty subordinate was larger under the private context compared with the public context (2.50 under the private context and 1.99 under the public context). In terms of contribution, the gap between the manager’s salary adjustment for a high contribution subordinate and a low contribution subordinate was larger under the private context compared with the public context (6.09 under the private context and 4.87 under the public context). These results indicate that when deciding about salary adjustments, the allocator is more influenced by the affect variable under the private context than under the public context, and likewise for the loyalty and contribution variables.

Regarding the bonus allocation decision, the interactive effects were significant be-tween the reward allocation context and the three exchange relationship factors. There were were significant differences between the private and public contexts when the man-ager made the bonus allocation based on their view of the subordinate’s affect, loyalty and contribution characteristics.

In terms of affect, the gap between the manager’s bonus allocation for a close affect subordinate and a distant affect subordinate was larger under the private context com-pared with the public context (0.98 under the private context and 0.76 under the public context). In terms of loyalty, the gap between the manager’s bonus allocation for a high loyalty subordinate and a low loyalty subordinate was larger under the private context compared with the public context (2.50 under the private context and 1.96 under the public context). In terms of contribution, the gap between the manager’s bonus alloca-tion for a high contribualloca-tion subordinate and a low contribualloca-tion subordinate was larger under the private context compared the public context (6.11 under the private context and 4.93 under the public context). These results indicate when deciding about bonus distributions, the allocator was more influenced by the affect variable under the private context than under the public context, and likewise for the loyalty and contribution vari-ables. Overall, the results show that the reward allocation decision is more influenced by the affect, loyalty and contribution variables in the private context than in the public context. Therefore, H4 was completely supported.

6. Discussion

This study is based on LMX theory and explores how managers are influenced by the exchange relationship factors of affect, loyalty and contribution, and how they allocate rewards to subordinates. The results supported the hypotheses presented, implying that managers allocate different rewards to different subordinates because of their degree of affect with the subordinate, the level of loyalty that the subordinate displays to the manager, and the contribution that the subordinate makes to the group. In other words, managers treat those subordinates with close affect, high loyalty and contribution as an insider, and provide them with more support and attention. Iin terms of monetary reward, managers typically offer “insiders” a higher rate of annual salary adjustment and a higher amount of bonus. This preferential treatment is a typical social exchange and is consistent with the LMX theory, which emphasizes that insiders with a high quality exchange relationship obtain more official and non-official rewards (Dienesch and Liden (1986)). Where fairness is of utmost importance in the reward allocation decision, then a subordinate’s contribution, based on his competency or performance, is the manager’s first priority (Hu, Hsu and Cheng, (2004) and Kiker and Motowidlo (1999)).

The results also revealed that among the three exchange relationship factors, the effect of contribution on reward allocation was significant and consistent. No matter whether the subordinate has a close or distant affect, or high or low loyalty, as long as he possesses a high level of contribution, the reward allocated was higher than the overall mean. The results also showed that the effect size of loyalty was the highest among the three exchange relationship factors, meaning that the manager’s employee categorization is more concerned about loyalty.

6.1. The role of national cultures on the exchange relationship and reward decisions

This study supported Hofstede’s proposition of differences among national cultures (Hofstede (1980)). In terms of affect, Taiwan managers allocate more monetary rewards to subordinates with a closer affect, which is in sharp contrast to U.S. managers. But for subordinates with low loyalty and contribution, U.S. managers allocate less mone-tary rewards than to the subordinates with high loyalty and contribution, which is sharp contrast to Taiwan managers. The results also confirmed the differences between the

Chinese and Western national cultural values and their influence on the reward allo-cation decision, and also corroborated prior research that indicted Chinese culture was characterized by collectivism and more focused on the interpersonal relationship and quality of the relationship (Zhou and Martocchio (2001)). Therefore, Chinese cultural values are more concerned about affect, whereas Western society places more emphasis on individualism and work performance, and so contribution is the more influential factor in the reward allocation decision.

For organizations with individualistic characteristics, Gomez-Mejia and Welbourne (1991) indicated that managers placed emphasis on self-efficiency, and that the reward was allocated based on the subordinates’ performance and contribution. For organiza-tions with collectivist characteristics, Adler (1991) and Muna (1980) indicated that man-agers regarded a subordinate’s loyalty as more important than work efficiency. However, this study found that U.S. managers were more concerned than their Taiwan counter-parts about their subordinates’ public support for to the manager’s work concepts. As to whether this conclusion suggests that U.S. managers place emphasis on the value of “loyalty” is worthy of future research.

6.2. The role of allocation contexts on the exchange relationship and reward decisions

The type of reward allocation policy can influence a subordinate’s cognition of other people’s rewards, as well their own sense of justice and satisfaction (Kidder, Bellettririe and Cohen (1977) and Reis and Gruzen (1976)). Therefore, if the reward allocation is conducted in public, managers are likely to follow the norms of social justice and allocate fairly based on the subordinate’s work performance. But if the allocation is conducted in private, managers are more likely to act in a preferential manner (Freedman and Montanari (1980), Hu, Hsu and Cheng (2004) and Leung and Bond (1984)). The study results showed that for rewards allocated in a public context, managers were less inclined to make a preferential allocation, and so the influence of affect, loyalty and contribution was weaker. In contrast, for rewards allocated in a private context, managers were more likely to act in a preferential manner toward favored subordinates or insiders. The study results also implied that the manager’s differential is intuitively based on cognition and consideration of management efficiency, talent utilization and job achievement.

Sampson (1975) indicated that the principle of justice is not a common rule held by all humans, but one that is influenced by history, politics and culture. In terms of multi-culture comparative studies, Hsu (1970) found that the Chinese are more sensitive to the issue of social justice than in the West. This study showed that Taiwan managers were more obvious than their U.S. counterparts in making preferential reward allocations in a private or public context to subordinates with close affect than those with less affect. On the other hand, U.S. managers were more obvious than their Taiwan counterparts in making preferential reward allocations in a private or public context to subordinates making more contributions. The study’s results suggest that managers make a reward allocation decision, no matter whether under a private or public context, based on the degree of their affect with the subordinate or the amount of the subordinate’s contribu-tion. Taiwan managers are more concerned about the interactive relationship of affect, whereas U.S. managers place more emphasis on the subordinates’ individual performance and level of contribution.

7. Research Contribution and Limitations

Prior sociological research on reward allocation has tended to focus more on the dis-tributive justice aspect when examining an individual’s performance, or the influence of the relationship between the reward distributor and the reward recipient (Chen (1995)). However, this study explored how three factors (affect, loyalty and contribution) influ-ence the exchange relationship between the manager and subordinate in order to clarify the complexity of the managerial behavior in the reward allocation decision. Secondly, some researchers have claimed that allocation context is a very important issue for reward allocation (Mikula (1980)), but very few studies have examined its effects. This study represents an attempt to examine the joint effects of allocation context and exchange relationship on reward allocation decisions in Chinese and Western cultures.

Although this study identified significant cognitive differences in the monetary reward decision based on different national cultural values, there are several limitations in such cross-national comparative studies. First, this study was designed as simulated scenario experiment, and requested subjects to use their imagination to carry out the experiment beyond their organizations. Thus the survey subjects did not physically interact with the subordinates described in the scenario experiment, and so a deviation between the experimental context and real life can be expected. Another limitation of this study is

the manipulation of the affect, loyalty and contribution variables on two levels–“close affect” vs. “distant affect”, “high loyalty” vs. “low loyalty”, and “high contribution” vs. “low contribution”. However, this manipulation does not whether Chinese and U.S. managers attach similar meanings to ”high ” and ”low” loyalty. Moreover, in real life managers may have to deal with more than two types of contribution. Moreover the demand characteristic as a result of the within-subject design might pose a threat to the validity of the results, because the subjects could possibly figure out the purpose and trait of the research, and provide assumed answers rather than apply their real judgment. Finally, as in most cross-national studies, we did not have completely matched samples from two countries. Although the Taiwan and U.S. samples possessed a certain degree of geographic representation, the research could not confidently claim that the sample corporate managers were truly representative of both countries.

Aside from these limitations, the study points to some areas worthy of r future re-search. First, whether corporate managers themselves care more about the affect, loyalty or contribution. If different managers have different preferences, then what is the other factor influencing the manager’s reward allocation preference outside the three factors? This research used LMX as a base to investigate how the three factors (affect, loyalty and contribution) influence the exchange relationship and the reward allocation decision. Under the LMX theory, affect, loyalty and contribution are treated as antecedent influ-encing the exchange relationship, so it’s worthwhile to further examine if there any other inner motives or factors (e.g., trust) that might stand out as an intermediary factor in the reward allocation decision.

As this research was a horizontal-type design, and could not present the corporate managers’ inner process for the formation of affect, loyalty and contribution with their subordinates, and could not express the dynamic change of the exchange relationship between the manager and subordinate. Therefore, the future research can endeavor by utilizing the longitudinal observation or follow-up research method to examine the formation processed by the managers for their degree of affect, loyalty and contribution with their subordinates and the dynamic change of employee categorization.

Finally, it can be discussed in the future research that whether it is consistent be-tween the managers’ categorization and subordinate’s recognition themselves as insider or outsider. Also, it needs to further investigate that after the managers categorizing the subordinates and provide them with differential treatment, what type of effect may be

caused with in the organization and the effect to the organizational justice and the team cohesion.

Appendix

A possesses a strong competency in his work and can always fulfill your assignments ahead of time. He contributes greatly to the department’s overall performance. He agrees with your work concept and methodology in public. He will actively take responsibility for your mistakes. You have a very good emotional relationship with him, and you can tell him everything.

B possesses a poor competency in his work and can never fulfill your assignments in time. He contributes little to the department’s overall performance. He agrees with your work concept and methodology in public. He will actively take responsibility for your mistakes. You have a very good emotional relationship with him, and you can tell him everything.

C possesses a strong competency in his work and can always fulfill your assignments ahead of time. He contributes greatly to the department’s overall performance. He disagrees with your work concept and methodology in public, and will not actively take responsibility for your mistakes. You have a very good emotional relationship with him, and you can tell him everything.

D possesses a poor competency in his work and can never fulfill your assignments in time. He contributes little to the department’s overall performance. He disagrees with your work concept and methodology in public, and will not actively take re-sponsibility for your mistakes. You have a very good emotional relationship with him, and you can tell him everything.

E possesses a strong competency in his work and can always fulfill your assignments ahead of time. He contributes greatly to the department’s overall performance. He agrees with your work concept and methodology in public. He will actively take responsibility for your mistakes. You do not have a very good emotional relationship with him, and you tell him everything infrequently.

F possesses a poor competency in his work and can never fulfill your assignments in time. He contributes little to the department’s overall performance. He agrees with your work concept and methodology in public. He will actively take responsibility

for your mistakes. You do not have a very good emotional relationship with him, and you tell him everything infrequently.

G possesses a strong competency in his work and can always fulfill your assignments ahead of time. He contributes greatly to the department’s overall performance. He disagrees with your work concept and methodology in public. He will not actively take responsibility for your mistakes. You do not have a very good emotional relationship with him, and you tell him everything infrequently.

H possesses a poor competency in his work and can never fulfill your assignments in time. He contributes little to the department’s overall performance. He disagrees with your work concept and methodology in public. He will not actively take respon-sibility for your mistakes. You do not have a very good emotional relationship with him, and you tell him everything infrequently.

References

[1] Adams, J. S., Inequity in social exchanges. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, pp.267-300, 1965. NY: Academic Press.

[2] Adler, N. J., International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, PWS-Kent, Boston, MA, 1991. [3] Baskett, G. D., Interview decision as determined by competency and attitude similarity, Journal of

Applied Psychology, Vol.57, pp.343-345, 1973.

[4] Bond, M. H., Leung, K. and Wan, K. C., How does cultural collectivism operate: The impact of task and maintenance contribution on reward distribution, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol.13, pp.186-200, 1982.

[5] Brislin, R., Back-translation for cross-cultural research, Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, Vol.1, pp.185-216, 1970.

[6] Carrell, M. R. and Dittrich, J. E., Equity theory: The recent literature, methodological considerations, and new directions, Academy of Management Review, Vol.3, pp.202-210, 1978.

[7] Chang, L. C., An examination of cross-cultural negotiation: Using Hofstede framework, Journal of U.S. Academy of Busines, Vol.2, No.2, pp.567-570, 2003.

[8] Chen, C. C., New trends in rewards allocation preferences: A Sino-U.S. comparison, Academy of Management Journal, Vol.32, pp.408-428, 1995.

[9] Chen, M. S. and Chang, C. T., The optimal pricing and compensation strategies for heterogeneous salesforce, International Journal of Information and Management Sciences, Vol.7, No.4, pp.15-25, 1996.

[10] Chen, M. S. and Pai, T. C., The decision of compensation plan for inducing a monopolist to modify his solution, International Journal of Information and Management Sciences, Vol.8, No.1, pp.19-24, 1997.

[11] Cheng, B. S. and Jiang, D. Y., Supervisory loyalty in Chinese business enterprises: The relative effects of emic and imposed-etic constructs on employee effectiveness, Indigenous Psychological Re-search in Chinese Societies, Vol.14, pp.65-113, 2001. (In Chinese)

[12] Cheng, B. S., Paternalistic Authority and Leadership, Technical Report Prepared for National Sci-ence Council, Taiwan, 1993. (In Chinese)

[13] Cheng, B. S., Hierarchical structure and Chinese organizational behavior, Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, Vol.3, pp.142-219, 1995. (In Chinese)

[14] Deshpande, S. P. and Schoderbek, P. P., Pay-allocations by managers: A policy- capturing approach, Human Relations, Vol.46, pp.465-479, 1993.

[15] Dienesch, R. M. and Liden, R. C., Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development, Academy of Management Review, Vol.11, pp.618-634, 1986.

[16] Earley, P. C., Social loafing and collectivism: A comparison of the United States and the People’s Republic of China, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol.34, pp.565-581, 1989.

[17] Earley, P. C., East meets west meets mideast: Further explorations of collectivistic and individualistic work groups, Academy of Management Journal, Vol.36, pp.319-348, 1993.

[18] Earley, P. C., Self or group? Cultural effects of training on self-efficacy and performance, Adminis-trative Science Quarterly, ol.39, pp.89-117, 1994.

[19] Fossum, J. A. and Fitch, M. I. C., The effects of individual and contextual attributes on the sizes of recommended salary increase, Personnel Psychology, Vol.38, pp.587-602, 1985.

[20] Freedman, S. M. and Montanari, J. R., An integrative model of managerial reward allocation, Academy of Management Review, Vol.5, No.3, pp.381-390, 1980.

[21] Gomez-Mejia, L. R. and Welbourne, T., Compensation strategies in a global context, Human Resource Planning, Vol.14, pp.29-41, 1991.

[22] Graen, G. and Cashman, J., A role-making model of leadership in formal organizations: A devel-opment approach. In J. G. Hunt and L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership Frontiers, Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1975.

[23] Graen, G. and Scandura, T. A., Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing, Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol.9, pp.175-208, 1987.

[24] Graen, G., Role making processes within complex organizations. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook in Industrial and Organizational Psychology, pp.1201-1245, 1976. Chicago: Rand McNally.

[25] Graen, G., Novak, M. A. and Sommerkamp, P., The effects of leader-member exchange and job design on productivity and job satisfaction: Testing a dual attachment model, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, Vol.30, pp.109-131, 1982.

[26] Gudykunst, W. B., Matsumoto, Y., Ting-Toomey, S., Nishida, T., Kim. K. and Heyman, S., The influence of cultural individualism-collectivism, self construals, and individual values on communi-cation styles across cultures, Human Communicommuni-cation Research, Vol.22, No.4, pp.510-543, 1996. [27] Hammond, K. R., Representativeness vs. systematic design in clinical psychology, Psychological

Bulletin, Vol.51, pp.150-159, 1955.

[28] Ho, D. Y. F., On the concept of face, U.S. Journal of Sociology, Vol.81, pp.867-884, 1976.

[29] Hofstede, G. and Bond, M. H., The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth, Organizational Dynamics, Vol.16, pp.5-21, 1988.

[30] Hofstede, G., Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1980.

[31] Hofstede, G., Cultural constraints in management theories, Academy of Management Executive, Vol.7, pp.81-94, 1993.

[32] Hsu, F. L. K., U.S. and Chinese, New York: Natural History Press, 1970.

[33] Hsu, F. L. K., Psychological homeostasis and jen: Conceptual tools for advancing psychological anthropology, U.S. Anthropologic, Vol.73, pp.23-44, 1971.

[34] Hu, H. H., Hsu, W. L. and Cheng, B. S., The reward allocation decision of the Chinese manager: Influences of employee categorization and allocation situation, Asian Journal of Social Psychology, Vol.7, pp.221-232, 2004.

[35] Hui, C. H., Triandis, H. C. and Yee, C., Cultural differences in reward allocation: Is collectivism the explanation? British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol.30, pp.145-157, 1991.

[36] Kidder, L. H., Bellettirie, G. and Cohn, E. S., Secret ambitions and public performances: The effects of anonymity on reward allocations make by men and women, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol.13, pp.70-80, 1977.

[37] Kiker, D. S. and Motowidlo, S. J., Main and interaction effects of task and contextual performance on supervisory reward decisions, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol.84, No.4, pp.602-609, 1999. [38] Kim, K. I., Park, H. and Suzuki, N., Reward allocations in the United States, Japan, and Korea: A

comparison of individualistic and collectivistic cultures, Academy of Management Journal, Vol.33, pp.188-198, 1990.

[39] Leung, K. and Bond, M. H., The impact of cultural collectivism on reward allocation, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol.47, No.4, pp.793-804, 1984.

[40] Leventhal, G. S. and Michaeles, J. W., Self-depriving behavior as a response to unprofitable inequity, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol.5, pp.153-171, 1969.

[41] Leventhal, G. S., Michaeles, J. W. and Sanford, C., Inequity and interpersonal conflict: Reward allocation and secrecy about reward as method of preventing conflict, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol.23, pp.88-102, 1972.

[42] Liden, R. C. and Maslyn, J. M., Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale redevelopment, Journal of Management, Vol.24, pp.43-72, 1998.

[43] Mikula, G., Justice and Social Interaction. NY: Springer-Verlag, 1980. [44] Muna, F. A., The Arab Executive. McMillan, New York, 1980.

[45] O’Reilly, C. and Chatman, J., Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior, Journal of Applied Psychol-ogy, Vol.71, No.3, pp.492-499, 1986.

[46] Redding, S. G. and Wong, G. Y. Y., The psychology of Chinese organizational behavior. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The Psychology of the Chinese People, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1986. [47] Redding, S. G., The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1990.

[48] Reis, H. T. and Gruzen, J., On mediating equity, equality, and self-interest: the role of self-presentation in social exchange, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol.12, pp.487-503, 1976.

[49] Rousseau, D. M., Organizational behavior in the new organizational era, Annual Review of Psychol-ogy, Vol.30, pp.243-281, 1997.

[50] Sampson, E. E., On justice as equality, Journal of Social Issues, Vol.31, pp.45-64, 1975.

[51] Shapiro, E. G., Effects of expectation of future interaction on reward allocations in dyads: equity or equality, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol.31, pp.873-880, 1975.

[52] Sherer, P. D., Schwab, D. P. and Hememan, H. C., Managerial salary-raise decisions: A policy-capturing approach, Personnel Psychology, Vol.40, pp.27-38, 1987.

[53] Silin, R. H., Leadership and Value: The Organization of Large-scale Taiwanese Enterprises, Cam-bridge. MA: Harvard University, East Asian Research Cen ter, 1976.

[54] Singelis, T. M. and Sharkey, W. F., Culture, self-construal, and embarrassability, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol.26, No.6, pp.622-644, 1995.

[55] Suh, E., Diener, E., Oishi, S. and Triandis, H. C., The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol.74, pp.482-493, 1998.

[56] Triandis, H., Cross-cultural studies of individualism and collectivism. In J. J. Berman (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, Vol.37, pp.41-133, 1989. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [57] Vn de Vijver, F. and Leung, K., Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research, SAGE

Publications, 1997.

[58] von Grumbkow, J., Deen, E., Steensma, H. and Wilke, H., The effect of future interaction on the distribution of rewards, European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol.6, pp.119-123, 1976.

[59] Walster, E., Berscheid, E. and Walster, G. W., New directions in equity research, Journal of Person-ality and Social Psychology, Vol.25, pp.151-176, 1973.

[60] Westwood, R., Harmony and patriarchy: The cultural basis for “paternalistic headship” among the overseas Chinese, Organization Studies, Vol.18, pp.445-480, 1997.

[61] Yang, K. S., Chinese social orientation: An integrative analysis. In T. Y. Lin, W. S. Tseng, and E. K. Yeh (Eds.), Chinese Societies and Mental Health, pp.19-39, 1995.

[62] Zhou, J. and Martocchio, J. J., Chinese and U.S. Managers’ managers’ compensation award decision: A comparative policy-capturing study, Personnel Psychology, Vol.54, pp.115-145, 2001.

Authors’ Information

Hsiu-Hua Hu is currently an assistant professor in the Graduate School & Department of International Business, Ming Chuan University, Taiwan. She received her PhD in business administration from the National Taiwan University. She is a particularly specialized in field of compensation, performance management, competency & talents development, etc. Her research interest is in reward allocation decision of cross-culture studies.

The Graduate School & Department of International Business, Ming-Chuan University, Taipei 111, Tai-wan, R.O.C.

E-mail: shhu@tpts4.seed.net.tw TEL : +886-2-2579-0080

Kuo-Long Huang is currently a professor in Shih Chien University, Taiwan. He puts in his all efforts on the studies including human resource management and organizational behavior; especially on the issues of corporate networking, innovation, reward allocation, knowledge sharing, trust and conflict management. Shih Chien University, Taipei, Taiwan 104, R.O.C.

E-mail: klhuang@mail.kh.usc.edu.tw TEL : +886-7-667-8888 ext.4230

Shu-Cheng Chi is currently a professor in National Taiwan University. His research areas focus on the fields of organizational behavior, especially on the issues of leadership, cultural integration and conflict management.

National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan 10617, R.O.C. E-mail: n136@mba.ntu.edu.tw TEL : +886-2-3366-1049

Chen-Ming Chu is a professor in the Department of Business Administration, Chung Yuan Christian University, Taiwan. His research areas include human resource management and organizational behav-ior, especially on the issues of compensation, performance appraisal and international human resource management.

Chung Yuan Christian University, Chung Li, Taiwan 32023, R.O.C.