National Taichung University of Education,

Graduate Institute of Educational Information and Measurement

Doctoral Dissertation

Supervisor: Professor Bor-Chen Kuo, Ph.D

Professor Chen-Huei Liao, Ph.D.

Relationship between the cognitive component and

reading ability in Thai for fourth-grade Thai students:

A cross-lagged panel study

Graduate: Exkarach Deenang

I

Acknowledgments

My ability to complete this work was only possible because of the encouragement and support of so many individuals as well as the blessings I have received throughout this journey.

First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Bor-Chen Kuo and Professor Chen-Huei Liao, for all the encouragement and support they have given me over the past several years. Their insight and wisdom have been invaluable. They really gone above and beyond the call of duty and without them, the dissertation would have undoubtedly never been undertaken.

I would like to thank my dissertation committee, Professor Shu-Chuan Shih, Professor Huey-Min Wu and Professor Cheng Chien-Ming Thank you all for your willingness to serve on my committee and to share your knowledge and experience with me. I am especially grateful to Professor Magdalena Mo Ching Mok who served as a chair of my dissertation committee. She offered to share her wonderful knowledge in my dissertation. It has been an honor to learn from you during the whole process of writing this dissertation. She also inspired me to pursue doctoral study and further, they have been solid guides in this long journey.

I would like to thank Institute of Educational Information and Measurement for providing me with resources to complete a graduate career. I want to express my warm thanks to the faculty members Professor Cheng-Hsuan Li and Professor Chih-Wie Yang. I want to thank all my fellow friends of the K-Lab office, in particular Xiao-Bai, Te-Hung Lee, Chun-Yen, Dr. Hsiao-Chien Tseng (Vivi), and my friend Muslem Daud and Phan Thi Thu Nguyet. I would like to thank Minn-Shyan Wang, who gave me support all required administration work from the first time I came here until I graduated, thanks for you all.

II

I would like to thank Dr. Nattitep Pitaksanurat, the President of Udon Thani Rajabhat University for giving me a great and wonderful support to study here.

Finally, my deep and sincere gratitude to my family for their continuous and

unparalleled love, help and support. I am forever indebted to my father (Mr. Somchai), my mother (Mrs. Banjong) and my sister (Mrs. Kulaya) for giving me the opportunities and experiences that have made me who I am. I am grateful to my wife (Mrs. Sunisa) and my son (Master Thinn) for their motivation, trust, love, and for feeling so close despite being so far. They selflessly encouraged me to explore new directions in life and seek my own destiny. This journey would not have been possible if not for them, and I dedicate this milestone to them. Thank you.

III

Abstract

This study examined the relationship between cognitive component and reading ability to determine whether evidence can be provided to support the specific directionality of the reciprocal influence of these two factors. The study assessed a sample of 357 fourth-grade students from Thailand by cross-lagged panel analysis to determine across-time reciprocal influence. Data were collected in two times: January–February 2014 (first time) and November 2014–January 2015 (second time). Tests on phoneme isolation, rapid colour naming, rapid number naming, rapid word segmentation, morphological structure and morphological production, reading comprehension and word recognition were developed on the basis of the cognitive of reading theories used to explain reading processes. Construct validity was assessed by an expert panel. The reliability of the eight tests ranged from 0.656 to 0.981. To achieve the study goals, two-wave cross-lagged structural equation modelling was applied to elucidate the direction of the relationship between cognitive component and reading ability over time (one-year follow up).

Results show that in both times of data collection, cognitive component was significantly related to reading ability. The cognitive component and reading ability were associated at both time 1 and time 2. Additionally, the cognitive component in time 1 significantly predicted the reading ability in time 2, whilst the reading ability in time 1 significantly predicted the cognitive component in time 2. Cognitive component and reading ability exhibited a two-way relationship, indicating that the interactive view of reading can represent reading development in the context of the Thai language.

I

Table of Content

Acknowledgments ………. I

Abstract ... III Table of Content ... IV List of Table ... VII List of Figures ... VIII

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1

1.1 Background ……….. 1

1.2 Statement of the Problem ………. 4

1.3 Purpose of the Study ……… 5

1.4 Significance of the Study ………. 5

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 6 2.1 Reading Models... 6

2.1.1 Simple view of reading... 7

2.1.2 The traditional bottom-up view... 7

2.1.3 The top-down processing... 9

2.1.4 Interactive view... 10 2.2 Reading ability ………. 13 2.2.1 Reading comprehension…... 12 2.2.2 Word Recognition…... 13 2.3 Cognitive component ………... 15 2.3.1 Decoding-related skills …... 16

II

2.3.2 Rapid Automatized Naming …... 17

2.3.3 Morphological awareness …... 18

2.4 Development of cognitive components and reading abilities of reading development over time …... 19

2.5 Thai: A transparent orthography language …... 20

2.6 Summary of literature review …... 22

2.7 Research Questions ……….. 22

2.8 Hypotheses ………... 23

CHAPTER THREE: METHOD 25 3.1 Operational Definitions of Terms... 25

3.2 Participants... 27 3.3 Research design... 30 3.4 Measurement development ... 33 3.4.1 Planning... 33 3.4.2 Construction... 34 3.4.3 Validation ... 35 3.5 Measurements... 39

3.5.1 Cognitive component tests... 39

3.5.2 Reading ability tests... 43

3.6 Data collection... 46

3.7 Data analysis... 46

3.7.1 Cross-lagged panel analysis... 47

III CHAPTER FOUR: RESULT

4.1 Measurement development ... 50

4.1.1 Item mean-square statistics and item difficulty... 50

4.1.2 Reliability... 50

4.2 Preliminary results... 53

4.2.1 Descriptive statistics... 53

4.2.2 Bivariate correlations... 55

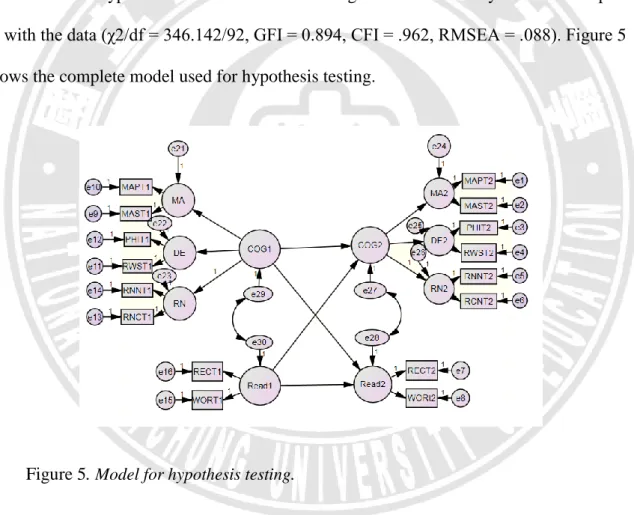

4.3 Structural model: Cross-lagged modelling ... 58

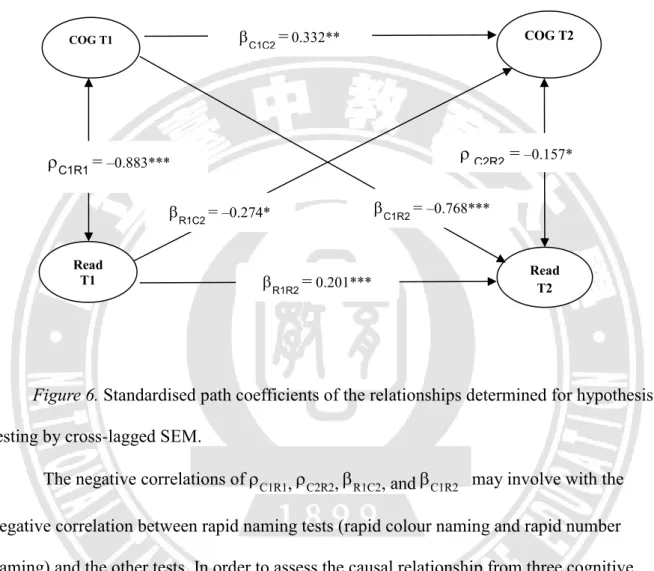

4.4 Hypothesis testing ……….... 59

CHAPTER FIVE: DISCUSSION 66 5.1 Summary ……….. 66

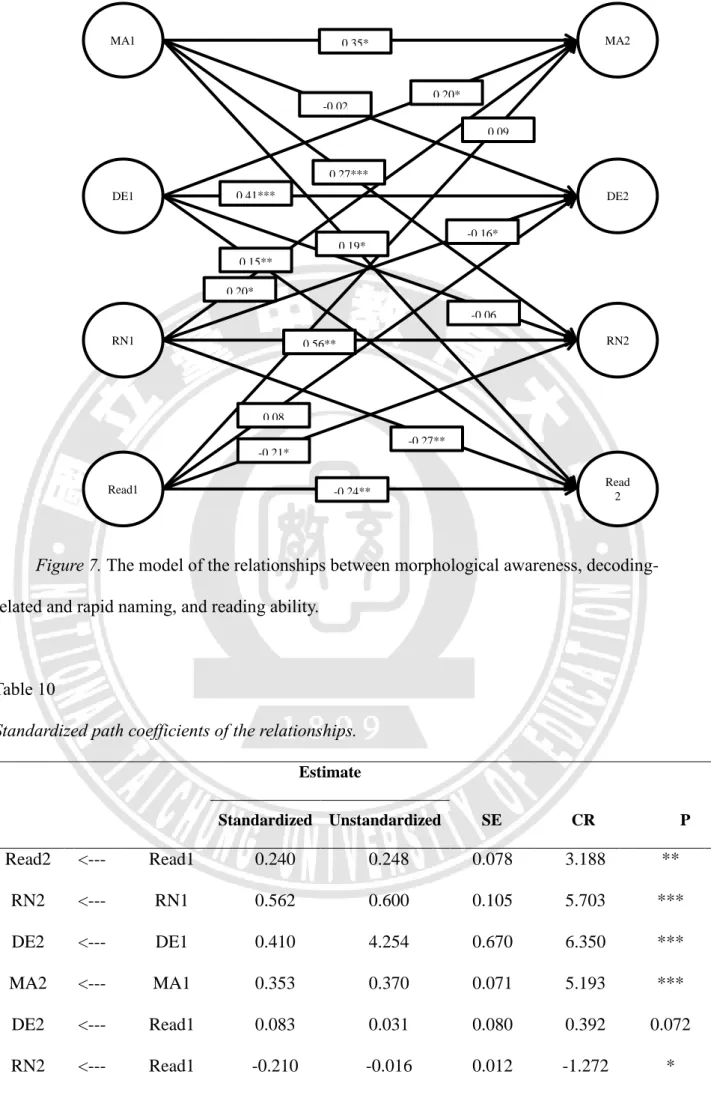

5.2 Major findings and discussion ………. 67

5.3 Conclusion ………... 74

5.4 Limitations and future research ………... 74

IV

List of Table

Table 1: Study sample ……… 28

Table 2: Scale Development Procedure ………. 32

Table 3: Measurements ……….. 33

Table 4: Validation of each test ………. 37

Table 5: Example of a word recognition test ………. 43

Table 6: Item fit with MNSQ item difficulty and reliability ………. 49

Table 7: Descriptive statistics for cognitive component and reading ability …... 51

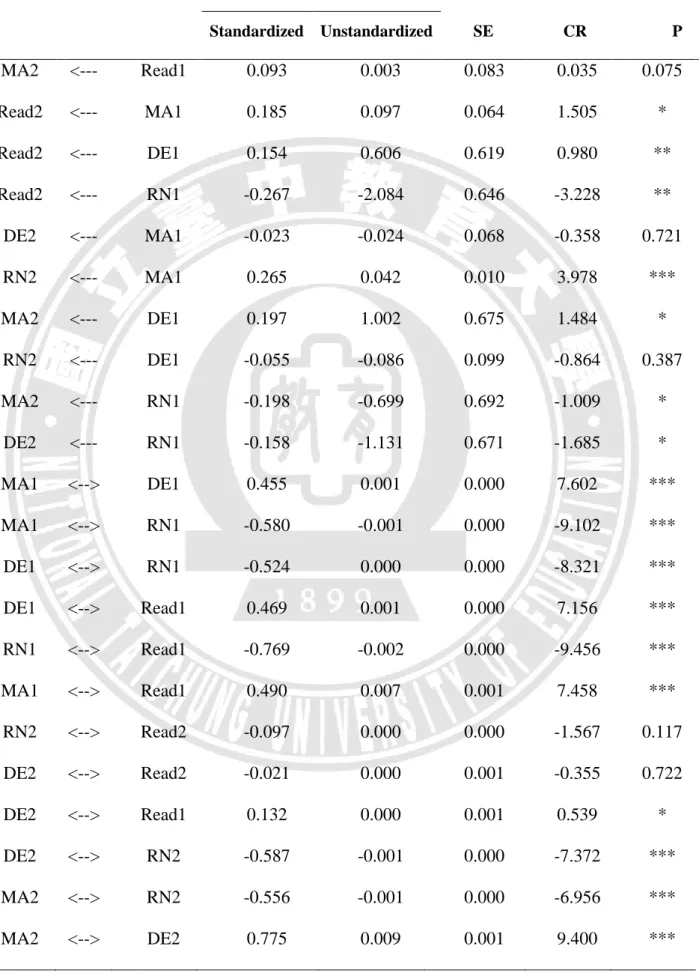

Table 8: Bivariate correlations amongst the cognitive and reading ability tests… 55 Table 9: Standardized path coefficients of the relationships ………. 58

Table 10: Standardized path coefficients of the relationships ……… 62

V

List of Figures

Figure 1: Interactive view of top-down and bottom-up processes for reading ….. 11 Figure 2: An example of Thai text ………. 18 Figure 3: The hypotheses and framework of this study ………. 23 Figure 4: A cross-lagged panel design using two variables measured over two

time points ………... 31

Figure 5: Model for hypothesis testing ……… 54 Figure 6: Standardised path coefficients of the relationships determined for

hypothesis testing by cross-lagged SEM ……… 60 Figure 7: The model of the relationships between morphological awareness,

decoding-related and rapid naming, and reading

ability.……….. 62

1

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

Overview

This chapter begins with a review of the background relevant to the topic of this study including the importance of reading, reading theory and characteristics of Thai language. Next, statements of the problem, the purpose of the study, research questions and the significance of the study are described.

1.1 Background

Reading is the most fundamental skill in modern societies and, as a consequence, acquiring the ability to read is one of the most important goals in early education. In our society, reading is essential to success as well as to social and economic advancement (Snow, Burns & Griffin, 1998). The ability to read facilitates successful participation in a variety of environments such as home, work, school and social settings. It helps individuals to reach academic excellence in all subjects, whereas a weakness in this ability is an obstacle to educational achievement (Graves, Juel, Graves, & Dewitz, 2010). (Please add at least one reference here).

Models of the reading process generally describe the relations among the components of reading in skilled readers. In these models, the relations between bottom-up word

recognition processes (lower-order processes) and top-down comprehension processes (higher-order processes) are typically described. According to Shankweiler (1989), children with problems in reading comprehension cannot build or contain the phonological

2

containing and processing this information in verbal working memory. Shankweiler (1989) believed that comprehension failure is a symptom of a low-level processing problem or phonological processing difficulties. In contrast, some studies show that reading experiences can facilitate the development of phonological awareness (Perfetti, Beck, Bell, & Hughes, 1987; Ellis & Large, 1988). Oakhill, Cain, and Bryant (2003) pointed out that comprehension failure can occur when low-level language processing is intact, but higher-level cognitive processing is insufficient. And they found that higher-level skills such as inference making can improve the reading comprehension of children who have a problem with reading.

However, research evidence makes it clear that neither purely bottom-up nor purely top-down models can fully explain the reading process (Rayner & Pollatsek, 1989; Stanovich, 2000). An interactive model of ongoing top-down and bottom-up processes is therefore needed to imply both graphic and contextual information to grasp the meaning of text for the reader (Perfetti, Landi, & Oakhill, 2005; Verhoeven & Perfetti, 2008). Moreover, one important model came from Gough and Tunmer (1986), the Simple View of Reading (SVR). The SVR model explains reading comprehension as the product of two main components, namely, decoding skills and language comprehension.

In the process of learning to read, children must hear and be able to recognize the sounds that are spoken and determine the differences between the sounds. This is often referred to as auditory perception and auditory processing, and involves the need to recognize the different sizes, shapes, position and form of letters and then learn to apply these with greater accuracy and speed. Word recognition subsequently becomes increasingly automatized by direct recognition of multi-letter units and whole words (Reitsma, 1983; Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). Automatic word recognition enables children to devote their mental resources to the meaning of text rather than to recognizing words, allowing them to use reading as a tool to acquire new concepts and information (Perfetti, 1998; Samuels &

3

Flor, 1997). According to the SVR model (Hoover & Gough, 1990), reading comprehension refers to the product of decoding skill and language comprehension. It is claimed that the reading ability involved in the comprehension of oral language strongly constrain the process of reading comprehension and word recognition.

From the cognitive perspective, decoding skill is an important factor related to reading achievement. Decoding skills consist of establishing the link between orthographic units or letters of written words and phonemes of speech sound. To acquire decoding skills, children must understand the patterns to integrate speech sound (Kendeou, Papadopoulos, &

Kotzapoulou, 2013). In addition, rapid automatized naming (RAN) is one aspect of the cognitive skill of reading development. Research previously found that RAN speed, defined as how quickly children can name continuously presented and highly-familiar visual stimuli, such as letters, digits, colours and objects, is a strong concurrent and longitudinal predictor of reading development for second and fourth grade (Liao, Georgiou, & Parrila, 2008).

Moreover, morphological awareness, the sensitivity to morphemes in words, is an important cognitive skill during the acquisition of reading. According to Carlisle (1995, p. 194), morphological awareness refers to the 'conscious awareness of the morphemic structure of words and ability to reflect on and manipulate that structure'. Kuo and Anderson (2006) further suggest that morphological awareness does not only involve the ability to encode or decode morphemes but it also pertains to a set of high-order abilities called

grapho-morphological awareness, which coordinates orthographic, phonological and semantic awareness.

Reading draws upon multiple cognitive components and reading ability in complex ways. Because the consistency degree of orthography varies in different writing systems, it has been questioned whether models of reading can be applied across orthographies. This study focused on the transparent orthography of the Thai language. Thai has its own unique

4

orthography for which, similar to Greek, Italian and Spanish, spelling and sound relationship is consistent. The unique characteristics of Thai include complex graphemic expressions, nonlinear vowel mixtures and expressions of tone, and complex combinations of vowels and diacritics (Winskel & Iemwanthong, 2010). The complexity of Thai language should involve quite distinct abilities, yet, there are surprisingly only few empirical studies investigating the influence that the cognitive component (decoding skills, rapid automatized naming and morphological awareness) and reading ability (reading comprehension and word recognition) have on reading development.

In this study, the cognitive and reading ability and their relationship to reading development in Thai are explicitly examined. Based on previous evidence, this study gives insights to the generation of theoretical models of reading development. Evidence of specific directionality in the relationships between the two domains found in this study resulted in implications that could guide the development of integrated curricula incorporating cognitive and linguistics instruction, which is a new finding in Thai language.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

The relationship between cognitive component and reading ability in English and non-transparent orthography has been studied for several decades (Coltheart, 1985; Frith, 1985). According to a thorough review of the existing literature, the relationship between cognitive component and reading ability in Thai of primary school students in their native country had never been investigated. Because of this major gap in the existing research, in this study, the researcher wanted to investigate the relationship between these components in Thai of fourth-grade students in their native country, along with the relationship across time.

5 1.3 Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study was to investigate the relationship between cognitive component and reading ability of reading development in Thai of students in fourth grade. First, the researcher wanted to determine whether there is a relationship between the

cognitive component and reading ability of reading overtime. Second, the researcher wanted to investigate the direction of this relationship over time.

1.4 Significance of the Study

The findings from this study will define the relationship between the cognitive

component and reading ability of reading development context in Thailand. It will also lead to the development of an assessment battery for Thai-speaking students and contribute to the proper design of an effective special instrument to measure Thai students’ reading

achievement. This study provides insights for the generation of theoretical models of reading in typically developing children in context of Thai language. Evidence of specific

directionality in the relationships between the two domains found in this study resulted in implications that could guide the development of integrated curricula that incorporates cognitive component and reading ability instruction which are appropriate for students in fourth grade.

6

CHAPTER TWO

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Overview

This chapter presents the literature which are relevant to the research goal that was presented in chapter one. This chapter is made up of five major sections: reading models, the reading abilities, the cognitive components of reading, the development of cognitive

component and reading ability of reading development over time for children, and Thai: the transparent orthography language. After the literature review, the research question and the hypothesis of this study will be presented in the final section of the chapter.

2.1 Reading Models

Previous research involving the development of reading models has shown various relationships among cognitive variables in different ways.. However, it is difficult to understand how theories that have evolved in the context of one language or script can be applied to other writing systems. So far, four main theories have been developed to help explain the nature of learning to read. First, the SVR (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) explains the relationship between decoding skills and language comprehension that affects individuals’ reading comprehension. Second, the traditional theory (Carrell, 1988; Gray & Rogers, 1956; Samuel, 1994; Samuel, 2004), or bottom-up processing, is focused on the printed form of a text. Third, the cognitive view (Ausubel, 1956), or top-down processing, enhances the role of background knowledge in addition to what appears on the printed page. Finally, the

interactive view (Rumelhart, 1990), in which the reader used both bottom-up processing and top-down processing strategies simultaneously or alternately to comprehend the text.

7

2.1.1 Simple View of Reading (SVR). General reading models have attempted to provide a core description of the overall relationship between reading and broader language knowledge. As noted previously, one important model came from Gough and Tunmer (1986): the SVR model. It postulates that reading comprehension (R) is the product of decoding skill (D) and language comprehension (C) in the following equation: R = D x C. This equation shows that the relationship of decoding skill and language comprehension on reading comprehension. If either skill (decoding or language comprehension) is a zero in the

equation, the product will produce with a value of zero in reading comprehension. As we look at the equation, two components are clearly important for reading comprehension. This model shows the central nature of reading comprehension. The first component refers to decoding skills (D), which relate to word recognition. Moreover, some researchers use the term decoding as a synonym for phonics (Chall, 1967, in Hoover & Tunmer, 1993), others describe the correspondence between letters and sounds (Hoover & Tunmer, 1993), and for Gough and Tunmer (1986) word recognition is accomplished through phonological coding. The second component of the SVR is language comprehension (C), which is the ability to take lexical information (Hoover & Tunmer, 1993) to understand the meaning of concepts and words heard or read. In the SVR equation, the reader must develop effective listening comprehension in order to make meaning of the words that they decode. Comprehension involves knowledge of concepts and vocabulary. This can be viewed as a broad language skill that develops through interaction with the environment from birth through childhood.

2.1.2 The traditional bottom-up view. The bottom-up view is the first approach used by researchers to explain the reading process, which can be said to be a traditional view of the reading process. In this processing, the reader starts from the smaller units of text to the larger units to comprehend the text (Carrell, 1988). According to the bottom-up approach, reading is a linear process by which the reader decodes a text word by word, and links the words into

8

phrases and then sentences (Gray & Rogers, 1956). Samuel (1994; 2004) suggested that at the first stage of learning to read, the printed word must be decoded and then the decoded words must be comprehended. This implies that the more automatic the decoding process becomes, the more cognitive resources are available for comprehension. According to Samuels and Kamil (1988, p. 25), the emphasis of the bottom-up view is a behaviourism perspective, which treated reading as a word-recognition response to the stimuli of printed words, and where “little attempt was made to explain what went on within the recesses of the mind that allowed the human to make sense of the printed page”. In other words, textual comprehension involves adding the meanings of words to get the meanings of clauses. These lower-level skills are connected to the visual stimulus, or print, and are consequently

concerned with recognizing and recalling. Like the audio-lingual teaching method, the phonics approach emphasises repetition and drills using the sounds that comprise words. Information is received and processed starting with the smallest sound units, and proceeding to letter blends, words, phrases and sentences. Thus, novice readers acquire a set of

hierarchically ordered sub-skills that sequentially build toward comprehension ability. Having mastered these skills, readers are viewed as experts who comprehend what they read. The bottom-up model describes an information flow as a series of stages that transforms the input and passes it to the next stage without any feedback or possibility of later stages of the process influencing earlier stages (Stanovich, 1980). In other words, language is viewed as a code, and the reader’s main task is to identify graphemes and convert them into phonemes. Consequently, readers are regarded as passive recipients of textual information in the bottom-up model of reading. Meaning resides in the text, and the reader has to reproduce it.

According to Rayner and Pollatsek (1989) also support the bottom-up approach to reading, they pointed out that a word shouldtake longer to recognize than a single letter, therefore learning to read should start from the small unit. Nevertheless, Kolers (1969) have

9

argued that the higher level information is being used in wordrecognition, which may

conflict with the direction of the bottom-up model. Thus, thebottom-up model was criticized because its view of reading comprehension is in achallenging. Several researchers also argued that reading involves more than word perceptions (Coady, 1979; Goodman, 1970). Lynch andHudson (1991) pointed out that this model slows the readers down in away that they cannot comprehend larger language units. Therefore, a model thatemphasized a process from higher-level comprehension came in.

2.1.3 The top-down processing. The report by Ausubel (1956) has showed that an important distinction between meaningful learning and rote learning should be made. Rote learning is the memorization of information based on repetition, where the information becomes temporary and subject to loss, whereas meaningful learning occurs when new information is presented in a relevant context and is related to what the learner already knows, so that it can be easily integrated into the learner’s existing cognitive structure. Learning that is not meaningful will not become permanent. This emphasis on meaning eventually informed the top-down approach to learning new words which the reader has never met before, and in the 1960s and 1970s there was an explosion of teaching methods and activities that strongly considered the experience and knowledge of the learner (Goodman, 1967; Smith, 1971, 1979). These new cognitive and top-down processing approaches revolutionized the conception of the way students learn to read (Smith, 1971, 1994). In this view, reading is not just extracting the meaning from a text, but it is also a process of connecting information in the text with the knowledge the reader brings to the act of reading. In this sense, reading is a dialogue between the reader and the text that involves an active cognitive process in which the reader’s background knowledge plays a key role in the creation of meaning (Tierney & Pearson, 1994). Reading is not a passive mechanical activity, but purposeful and rational, and dependent on the prior knowledge and expectations

10

of the reader. It is not merely a matter of decoding print to sound, but is also a matter of making sense of the written language (Smith, 1994). In short, reading is a psycholinguistic guessing game, a process in which readers sample the text, make hypotheses, confirm or reject them, make new hypotheses and so forth.

According to Hosenfeld (1984), he claimed that the good reader is a good guesser. Nevertheless, there was criticism concerning the claim that good readers guess more, and use the context more than poorer readers. The study by Nicholson (1993) showed that the poor and average readers who may benefit from contexts not the older and better ones. In other word, not only the previous experience or background knowledge were involved in reading process, but at least at the level of word recognition and lexical access, some form of bottom-up process is followed also. Carrell and Eisterhold (1983), and Eskey (1986) also challenged the views that reading comprehension involves either bottom-up or top-down processing. They pointed out that the model of the reading comprehension process should involves both bottom-up and top-down models, and then proposed that in comprehending a text, the two models are employed interactively and simultaneously.

2.1.4 Interactive view. Unlike bottom-up and top-down views of reading, interactive models portray reading as a nonlinear process and as bidirectional. Rumelhart (1990) explains that skilled readers use sensory, syntactic, semantic and pragmatic information to read, and these information sources (also known as knowledge sources) interact and depend on each other during the process of reading comprehension. Rumelhart’s interactive model (1990) consists of a visual information store (VIS); graphemic input goes into the VIS. This information then goes into a feature extraction device where critical features from the VIS are extracted. The features then go into a pattern synthesizer. The pattern synthesizer uses all knowledge sources, sensory and non-sensory, to produce a “most probable interpretation” (Rumelhart, 1990; p. 1163) of the graphemic input; all the knowledge sources come together

11

in one place, and “the reading process is the simultaneous joint application of all the knowledge sources” (p. 1164). Top-down and bottom-up processes are being applied at the same time. It is also important to note that hypotheses (or propositions) can be made at any level (feature, letter, letter cluster, lexical and syntactic levels). If a hypothesis has to be rejected, then another level of processing takes over (higher or lower) until the right

hypothesis is made. One can surmise that if hypotheses are constantly being rejected at any level, reading fluency and ultimately reading comprehension can be affected.

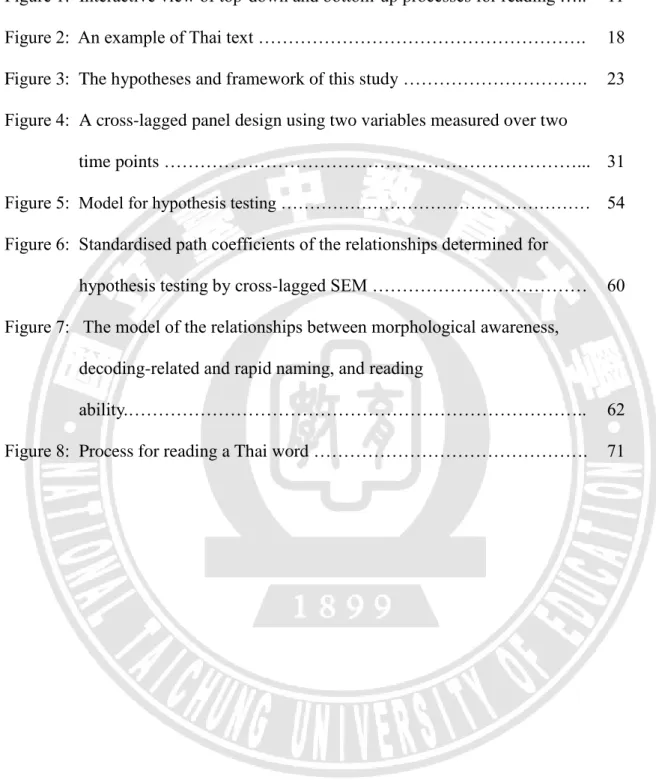

In addition, Allington (2006) stated that fluency breaks down for a variety of reasons. For example, the degree of familiarity with the topic being presented may impact word pronunciations as well as the ability to understand the word meanings. Fluency difficulties may also stem from poorly organized information. On the other hand, he explained that some children exhibit non-fluent reading behaviours even when reading about a familiar topic, and when word familiarity and pronunciation are adequate. From the interactive perspective, a good decoder who has knowledge of the text subject but is still reading non-fluently may have issues with syntactic and/or semantic processes as well as language deficits. As mentioned earlier, it is important to note that syntactic processes allow for the prediction of upcoming words as well as meaning making. Presented in Figure 1 (taken from Edwards, 2007, p. 40), is the interaction process between the top-down and bottom up theories. Under the listening conditions (without the speech and hearing problem), hearing, listening,

comprehending and reacting proceed predominantly with a bottom-up or “signal based processing” (Edwards, 2007, p. 40). In contrast, a listener may have to rely to a greater extent on top-down or “knowledge based processing” as a compensation strategy to understand the meaning of an unclear message (Wingfield & Tun, 2007). Based on interactive theories of reading, syntactic and semantic processes occur together and rely on each other when the reader is trying to make sense of a text. Furthermore, syntactic awareness may enable readers

12

to monitor their comprehension process more effectively, and this awareness can also help children acquire word recognition skills (Tunmer, Herriman, & Nesdale, 1988).

Figure 1. Interactive view of top-down and bottom-up processes for reading.

(Source: Edwards, 2007, p. 40)

Research regarding reading is extensive, and this summary of reading theories is by no means exhaustive. However, with a basic understanding of the theoretical basis of the SVR model, top-down or bottom-up processing, and interactive view of reading, what is important to bear in mind is that relying too much on these models may cause problems for beginning readers. Consequently, in developing reading abilities, these approaches should be

13 2.2 Reading ability

The process of reading can be conceptualised as comprising two sub-processes: decoding skills and language comprehension (Gough & Tunmer, 1986; Hoover & Gough, 1990). Decoding refers to the word recognition process and is the technical aspect of reading that transforms written words into their corresponding sounds. However, the general purpose of reading is to gain meaning of what is written, and this is the role of the second component known as reading comprehension. The process of understanding is an activity on a higher cognitive level where the reader uses personal experience, makes interpretations and draws conclusions. This study was used the word recognition variable and reading comprehension variable to measure reading abilities in context of Thai language.

2.2.1 Reading comprehension. Reading comprehension is “the process of

simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language” (RAND Reading Study Group, 2002, p. 11). This process of

interaction and involvement with a text is a function of both the reader and the text variables that takes place within a larger social context (Goldman, Saul, & Coté, 1995; McNamara & Magliano, 2009; RAND Reading Study Group, 2002). When successful, the product of reading comprehension is a coherent mental representation of the meaning of a piece of text that is integrated with the reader’s prior knowledge. This product is often referred to as a

mental model (Johnson-Laird, 1983) or a situation model (Kintsch, 1998; Kintsch, & van

Dijk, 1978), and is considered the basis for learning from a text. The nature of the model, that is, the ideas and the links connecting those ideas, defines what has been learned. Reading comprehension is a complex skill, it requires the successful development and orchestration of a variety of lower- and higher-level processes and skills (Balota, Flores d’Arcais, & Rayner, 1990). As a consequence, there are a number of sources for potential comprehension failure, and these sources can vary depending on the skill level and age of the reader (Keenan,

14

Betjeman, & Olson, 2008). At early grade levels (below fourth grade) mastering word recognition and fluency do contribute mightily to grade level reading comprehension (Duke & Pearson, 2002). Children at these ages cannot yet read the text, and therefore it is not possible to assess their reading comprehension skills by using text comprehension test. Theories and models of reading comprehension are necessary to make sense of this complexity. In current study, the reading comprehension skill was measure by reading comprehension test which is appropriate for grade four students.

2.2.2 Word recognition. Word recognition can be defined as the identification of a written word, i.e. the pronunciation of a word encountered in print or writing. Word recognition is assumed to be one of the basic skills to be developed by beginning readers (Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). Although the majority of researchers would agree with this definition of word recognition, they differ in their view on the learning processes behind this skill. Two types of models are defended: first, there are the stage models of beginning reading; second, there are the non-stage models (Chall, 1999). Many models of beginning reading development have argued strongly in favour of a sequence of rather uniform stages in reading development (Chall, 1983; Ehri, 1987; Gough & Hillinger, 1980). Although these models differ in the details of their description, in their use of labels and in their precise identification of sub-stages, they all propose more or less a first stage of direct word recognition on the basis of either visual or context-bound cues, a second stage of indirect-mediated word recognition through the use of graphic instead of visual cues (grapheme-phoneme correspondences), and a third stage of direct word recognition again, now based on automatisation of the indirect form of word recognition. Typical for this paradigm is the notion that, although both the first and third stages demonstrate direct word recognition, there is a qualitative difference between both types of word reading, the third being alphabetical in root, while the first is not (Ehri, 1991). Thus far, most of these stage models of beginning

15

reading are based on research with young children during the first year of formal reading instruction. Since the first studies on stages in reading appeared, subsequent studies revealed that the occurrence of the different stages and the speed of moving into the next stage is dependent on the shallowness of the specific orthography at hand and the consistency of the orthography (Seymour, Aro, & Erskine, 2003; Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). The levels of orthographies transparency are distinguished by the grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules (GPCRs) across languages. Transparent orthographies (e.g., German, Korean, Spanish, Greek, and Portuguese) are characterised by a close, grapheme-phoneme relationship, whereas in opaque or nontransparent orthographies, it is inconsistent and unpredictable. In transparent orthography such as German for example, Pillunat and Adone (2009) suggest that word recognition was strong predictor for oral reading fluency among German grade four students. Thai language in this study is a transparent orthography similar to German. To measure word recognition skill in current study, the word recognition test was used.

2.3 Cognitive component of reading

Research literatures on three cognitive components of reading related to this study are presented in this section. They are: Decoding-related skills; Rapid automatized naming (RAM), and Morphological awareness. Cognitive abilities for reading defined as the information processing theorywhich is conceptualizes children’s mental processes through the metaphor of a computer processing, encoding, storing, and decoding data (Radach, Kennedy, & Rayner, 2004). Information processing theory is hypothesized to be one of the core cognitive skills associated with automatic reading skills and reading fluency.

Information processing refers to the efficiency of processing simple cognitive or perceptual information (Palmer, 2008).Cognitive model of reading mostly developed from research in non-transparent orthographies such as English (Coltheart, 1985; Frith, 1985). Nevertheless, recent cross-linguistics studies indicated that the level of orthographic transparency of

16

language may influence the cognitive component model of reading. The levels of

orthographies transparency are distinguished by the grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules (GPCRs) across languages. Transparent orthographies (e.g., Korean, Spanish, Greek,

Portuguese and Italian) are characterised by a close, grapheme-phoneme relationship, whereas for opaque or nontransparent orthographies, the grapheme-phoneme relationship is inconsistent and unpredictable.The GPCRs rules indicated that the difference level in GPCRs may involve different skills or abilities to explain the cognitive model of reading. For

instance, Wang, Ko, and Choi (2009) found that morphological awareness explained unique variance in word reading and reading comprehension among Korean students between grade two and grade four after controlling for phonological awareness and oral vocabulary. Wang et al. (2009) suggest that morphological awareness is important to reading in transparent

orthographies, such as Korean. Georgiou, Parrila, Cui, and Papadopoulos (2013) found that rapid automatized naming significantly predicted oral reading fluency and silent reading fluency among Greek-speaking Cypriot children between grade two and grade six. Moreover, Kendeou, Papadopoulos, and Kotzapoulou (2013) used the simple view of reading (SVR) model to explain the correspondence between phonological and orthographic representations and found that these two variables were significant predictors of decoding skills in the SVR model for transparent orthography in Greek. According to Gough and Tunmer (1986), SVR suggests that reading comprehension can affect both decoding skills and language

comprehension.

2.3.1 Decoding-related skills. Studies provided evidence in favor of the SVR model which elucidated the relationship between decoding skills, language comprehensionand reading (Grainger, Muneaux, Farioli, & Ziegler, 2005; Hino, 2011; Share, Jorm, Maclean, & Matthews, 1984). Decoding skills refer to the correspondence between orthographic unit and phoneme of speed sound, in order to achieve this skill the readers need to understand the

17

patterns of integration between the those two variables. For example,Savage and Stuart (2006) examined the contributions of phoneme awareness and grapheme use in early reading development, and reported that the understanding of vowel pattern of student at age 6 was a unique and longitudinal predictor of reading at age 8. Therefore, students who have

developed adequate decoding skills will be able to apply them when new words or unfamiliar words are encountered. Beforea word is recognized, readers should first map sound to letters, blend the corresponding sounds, and finally pronounce the entire word. Following the

concept of SVR (Gough & Tunmer, 1986), decoding skills should include the abilities to decipher letters to the corresponding sound, to match phonemes or sound to orthographic units, and to segment words quickly and accurately to achieve reading success

2.3.2 Rapid automatized naming (RAN). Previous studies indicated rapid automatized naming (RAN) speed is a strong predictor of reading abilities (e.g., Kirby, Parrila, & Pfeiffer, 2003; Moll, Ramus, Bartling, Schulte-Korne, & Landerl, 2014; Poulsen, Juul, & Elbro, 2015; Tobia & Marzocchi, 2014; Wijayathilake & Parrila, 2014). Commonly defined as the ability to quickly name highly familiar objects, such as alphanumeric (naming letters or digits) or nonalphanumeric (colours or objects) stimuli (Wolf & Bowers, 1999), RAN explained unique variance in reading, even after verbal and nonverbal cognitive

abilities (Cornwall, 1992) phonological awareness (Kirby et al., 2003) were controlled. Liao, Georgiou, and Parrila (2008) report the independent contribution of RAN to reading, and suggest that RAN could be a good tool in identifying children with Chinese character

recognition difficulties. Moreover, Bowers and Wolf (1993) claimed that based on the double deficit hypothesis (DDH), RAN is a unique variable and is independent from phonological processing in reading skill. Thus, it can be assumed that RAN is an important factor related to reading abilities. With respect to the current study, both alphanumeric (naming letters) and

18

nonalphanumeric (naming colours) RAN tests were used to examine the model of the cognitive components of reading in Thai.

2.3.3 Morphological awareness. Morphological awareness, or the sensitivity to morphemes in words, is an important cognitive skill during the acquisition of reading (Bar-Kochva & Breznitz, 2014; Good, Lance, & Rainey, 2015; Sparks & Deacon, 2015; Zhang, 2015). According to Carlisle (1995, p. 194), morphological awareness refers to the

“conscious awareness of the morphemic structure of words and ability to reflect on and manipulate that structure”. Multimorphemic words (e.g., blackboard) can be broken down into two or more morphemes (e.g., black and board). Morpheme units can also stand alone as free morphemes (e.g., help and hope) and chain morphemes (e.g., helpful and hopeless). Morphological awareness predicts reading abilities in both alphabetic (Sparks & Deacon, 2015; Wang et al., 2009) and nonalphabetic (McBride-Chang, Wat, & Wagner, 2003; Zhang, 2015) languages. A nonalphabetic language, Chinese, for example, morphological structure test and morpheme identification test were strong and unique factors in predicting Chinese character recognition (McBride-Chang et al., 2003). Kuo and Anderson (2006) further suggest that morphological awareness does not only involve the ability to encode or decode morphemes but it also pertains to a set of high-order abilities called grapho-morphological awareness, which coordinates orthographic, phonological and semantic awareness.

Previous studies reviewed above lead to the conclusion that morphological awareness, decoding and RAN are important factor of cognitive abilities, which affect reading

development. In this study, three variables of cognitive skills including morphological awareness, decoding-related and RAN were used to measure cognitive skill.

19

2.4 Development of cognitive components and reading abilities of reading development over time

Previous longitudinal studies have identified relationships between the cognitive components and reading ability factors in reading development (Wang, Ko, & Choi, 2009; Georgiou, Parrila, Cui, & Papadopoulos, 2013; Protopapas, Simos, Sideridis, & Mouzaki, 2012; Yeung, Ho, Chan, Chung, & Wong, 2013). In particular, the study by Wang et al. (2009) aimed to compare the role of morphological awareness in transparent orthography such as Korean and opaque orthography system such as English. Participants were followed across a period of three years from grade 2 to grade 4. Wang et al. (2009) found that

morphological awareness explained unique variance in word reading and reading comprehension among Korean grade two to grade four students after controlling for phonological awareness and oral vocabulary. Wang et al. (2009) suggested that

morphological awareness is important not only in an opaque orthography but also in a transparent orthography. In additional, Georgiou et al. (2013) found that rapid automatized naming significantly predicted oral reading fluency and silent reading fluency among Greek-speaking Cypriot children between grade two and grade six. In addition, the longitudinal study by Protopapas, et al. (2012) which adopted the SVR model to examine reading

comprehension in Greek and in which participants were followed across a period of two years from grade 3 to grade 5, found that decoding, the print-dependent components, and oral language, and the print-independent component predicted reading comprehension in Greek. Furthermore, the study of reading model in Chinese language by Yeung et al. (2013)indicated that rapid automatized naming (RAN) and morphological awareness significantly predicted reading comprehension by using word reading as a mediator factor among Chinese grade 4 student in Hong Kong. Word reading in Yeung et al.’s (2013) study referred to abilities related to word recognition skill in the Chinese language. Longitudinal studies reviewed

20

above indicated that both cognitive components and reading abilities are important to reading development. Grounded on the above review, this study included both cognitive components and reading abilities in exploring Thai language development of grade 4 students in Thailand.

2.5 Thai: A transparent orthography language

Thai is the standard language spoken officially and nationally by almost sixty million people throughout every part of Thailand. It is also spoken from northern India (Assam) through northern Burma, southern China (Yunnan province and Guangxi Region), Vietnam (in the north), Laos and Thailand. Linguists have classified Thai as belonging to a Chinese-Thai branch of the Sino-Tibetan family (Kapur-Fic, 1998; Winskel, 2010). It is a tonal language, uninflected and predominantly monosyllabic like Chinese. As was noted by the renowned Thai linguist and writer Phaya Anuman Rajadhon in his 1961 paper, The Nature

and Development of the Thai Language, there are hundreds of similar words in Thai and

Chinese. Many of these words may be cultural borrowings, largely by the Thais, after long and continual contact with the Chinese. On the other hand, there are certain classes of words that obviously were derived from common sources in ancient times. More importantly, beyond the similarities of single words, spoken Thai and spoken Chinese are structured in much the same way, though when written the two languages are completely different in appearance (retrieved on August 19, 2004, from www.thaioregon.com/thailanguage.htm). Most polysyllabic words in the Thai lexicon have been borrowed, mainly from Khmer, Paliand Sanskrit (Winskel & Iemwanthong, 2010).

In Thai, spaces are used only for delimiting sentences and, rarely, for emphasizing words. Note that sometimes the lack of spacing may lead to ambiguity, for example when the same string of characters may be parsed into words in different ways, which may result in different meanings. To distinguish the meaning of those words, Thai readers may have to read

21

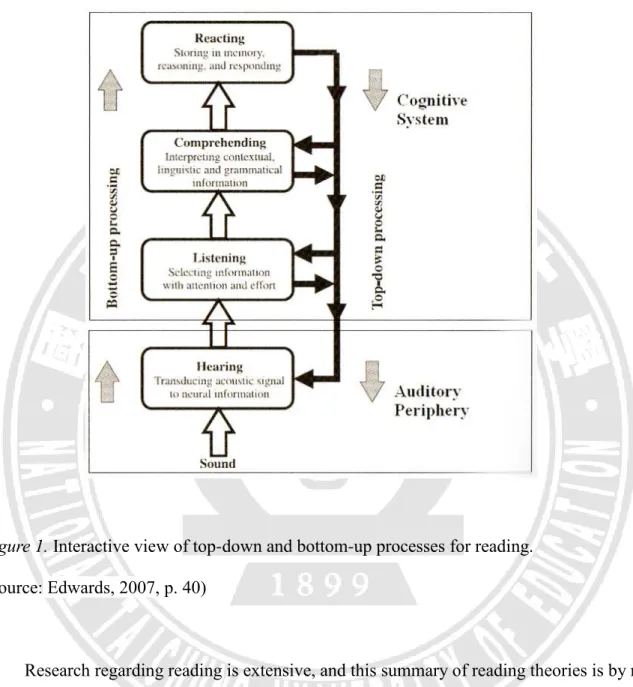

ชาวบ้านในแถบจังหวัดกระบี่มีความเชื่อว่า การเดินทางในช่วงเวลาที่พระอาทิตย์ใกล้จะตก

ดินอาจถูกภูตผีปีศาจท าร้าย เพราะชาวกระบี่มีความเชื่อว่าเวลาดังกล่าวเป็นเวลาที่ยักษ์ตาย

ห้ามเดินทาง และการเดินทางสมัยก่อนต้องผ่านป่าเขาที่ทุรกันดาร เมื่อใกล้เวลาที่พระ

อาทิตย์จะตกดินให้หยุดพักรอจนกว่าจะมืด จึงค่อยออกเดินทางต่อ

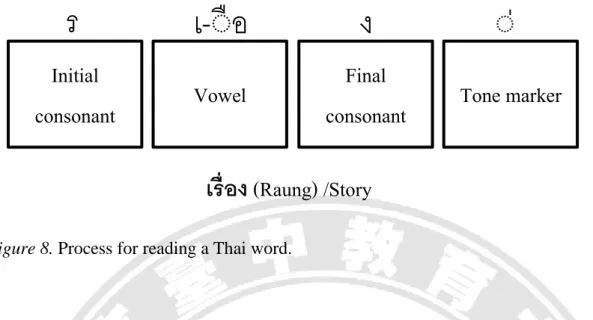

all along the sentence until they find out what those words really mean. In general, no punctuation mark is used in Thai. (See Figure 2 for an example of Thai text).

Note. This passage describes about the belief of people in the Southern of Thai for journeys during the sun set.

Figure 2. An example of Thai text.

The written Thai language, read horizontally from left to right, as is English, consists of 22 consonants and 22 vowels that combine to formulate syllabic sounds. The sounds are combined with five different tones — middle (or called normal or even tone), high, low, rising and falling to produce a melodious, lyrical language (Winskel & Iemwanthong, 2010).

Learning to spell and read in Thai is different from learning to write. When children start learning to spell Thai words, they need to follow the rule of spelling, which means they must pronounce the initial consonant first, followed by vowels and the final consonant, respectively. No matter what the writing structure would be, they have to follow this rule. For example, the writing structure of the word ‘แมว’/‘meow’ is V(แ)/C(ม)/C(ว), but when we asked children to spell this word, they would pronounce it as C(ม)/V(แ)/C(ว), this is the important rule of Thai word reading that is unlike other languages. The Thai language has been traditionally described as a rigid subject-verb-object (SVO) language (Singnoi, 2000), like Chinese and English. It differs from Japanese, which is subject-object-verb (SOV).

22 2.6 Summary of literature review

Several models of the reading have been put forward to explain the reading-related variable in complex ways. The SVR model explains the relationship between decoding skills and language comprehension which is a key element in explaining reading model. Moreover, the top-down processing model explains reading in terms of the amount the brain already knows and this knowledge affects the perception of what is being read. This model was initially thought to be in contrast to the bottom-up processing model which explains reading as a linear progression from small unit to comprehension. From all of the models mentioned above, two important sets of variables were used to explain reading development, namely, the cognitive components and the reading ability variables. In this study, reading ability and cognitive components were used to explain reading development in the context of Thai language. The reading ability variables included in this study were reading comprehension and word recognition. The cognitive variables included in this study were morphological awareness, decoding related skill and rapid automatized naming.

2.7 Research Questions

1. What is the relationship between the cognitive component and reading ability at time-1 of Grade 4 students?

2. What is the relationship between the cognitive component and reading ability at time-2 of Grade 4 students?

3. What is the effect of Grade 4 students’ reading ability at time-1 on the students’ reading ability at time-2 (one year later)?

4. What is the effect of Grade 4 students’ cognitive component in reading at time-1 on the students’ cognitive component in reading at time-2 (one year later)?

23

5. What is the relationship between the reading ability at time-1 and cognitive component at time-2 of Grade 4 students (one year later)?

6. What is the relationship between the cognitive component at time-1 and reading ability at time-2 of Grade 4 students (one year later)?

2.8 Hypotheses

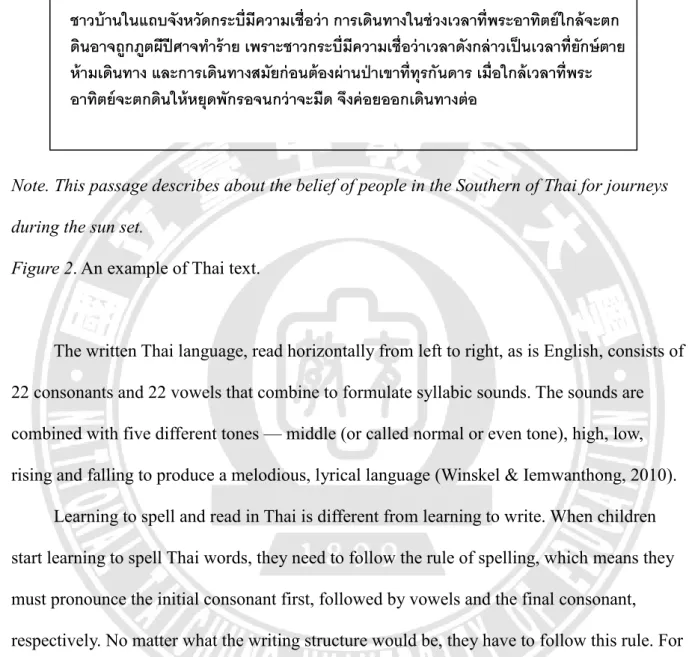

In order to answer the research questions, the hypothesis framework depicted in Figure 3 is used. The conceptual model includes the cognitive and reading ability variables at two time points. As Figure 3 shows, there are several paths. First, the relationship between cognitive component and reading ability at time 1 will be analysed (hypothesis 1), and then the relationship between cognitive component and reading ability at time 2 will be analysed (hypothesis 2). Next, separate auto-lagged relationships of cognitive component and reading ability between times 1 and 2 will be analysed (hypotheses 3 and 4). Finally, the cross-lagged relationship between the cognitive component at time 1 and the reading ability at time 2 will be analysed (hypothesis 5), and the cross-lagged relationship between the reading ability at time 1 and the cognitive component at time 2 will be analysed (hypothesis 6). There are 6 Statistical hypotheses as follow;

1. The relationship between cognitive component and reading ability at time 1 H0: ρC1R1 = 0

H1: ρC1R1 ≠ 0

2. The relationship between cognitive component and reading ability at time 2 H0: ρC2R2 = 0

H1: ρC2R2 ≠ 0

3. The separate auto-regressive relationships of cognitive component between times-1 and time-2.

24 Cognitive Component (C1) Cognitive Component (C2) Reading ability (R1) Reading ability (R2) Time 1 Time 2 H0: C1C2 = 0 H1: C1C2 0

4. The separate auto-regressive relationships of reading ability between times-1 and time-2.

H0: R1R2 = 0

H1: R1R2 0

5. The cross-lagged relationship between the cognitive component at time 1 and the reading ability at time 2

H0: R1C2 = 0

H1: R1C2 0

6. The cross-lagged relationship between the cognitive component at time 1 and the reading ability at time 2

H0: C1R2 = 0

H1: C1R2 0

Figure 3. The hypotheses and framework of this study.

𝐻4 𝐻6 𝐻5 𝐻2 𝐻1 𝐻3

25

CHAPTER THREE

METHOD

Overview

The present study employed a two-wave cross-lagged panel design to determine the reciprocal relationship over time of cognitive component and reading ability in reading development in Thai of grade 4 children. For chapter three the operational definitions of terms will be presented first. These definitions were based on the literature reviews presented in chapter two. Next, to answer the research questions, the methodology was organized according to six steps comprising research setting and participant, research design,

measurement development, measurements, data collection, and data analysis. The details of each step were described below.

3.1 Operational Definitions of Terms

The following terms were defined within the context of the current studies and based on the literature review in chapter two. The definitions are presented to provide additional clarity throughout the dissertation.

3.1.1 Reading: The process of acquiring the basic skills necessary for learning to read, which is based upon two important competencies. One is the reading ability, which is the ability to construct meaning or comprehend from written representations of language. In this study, reading ability was measured by two instruments comprising a reading comprehension test and a word recognition skills test. Second is the cognitive component, which is the ability to process and connect information in text with the knowledge the reader brings to the act of reading. In this study, the cognitive component was measured by three instruments,

26

comprising a decoding test, a morphological awareness test, and a rapid automatized naming test.

3.1.2 Cognitive component: Cognitive component are involved the efficiency of the brain's processes applied to the information, associated with automatic reading skills. In this study, the cognitive component consists of three sub-components: decoding skill,

morphological awareness skill and rapid automatized naming skills.

3.1.2.1 Decoding skill. Refers to abilities to recognize and analyze an orthographic

units or letters of written words to connect it to the phonemes of speech sound. These skills include the ability to recognize the corresponding sound to match phonemes or sound to orthographic units, and to segment words quickly and accurately. The decoding skills in this study were measured by a phoneme isolation test and a rapid word segmentation test.

3.1.2.2 Morphological awareness skill. The ability to have conscious awareness of the

morphemic structure of words, and the ability to reflect on and manipulate that structure. The morphological awareness skills in this study were measured by a morphological structure test and a morphological production test.

3.1.2.3 Rapid automatized naming skill. The ability to quickly name a number of highly

familiar visual stimuli, such as alphanumeric (digits) or non-alphanumeric (colours) stimuli. The rapid automatized naming skills in this study were measured by rapid number naming and rapid colours naming tests.

3.1.3 Reading ability. Reading ability refers to the ability to construct meaning from written representations of language. The reading ability in this study consists of two sub-components: reading comprehension skill and word recognition skill.

3.1.3.1 Reading comprehension skill. The process of simultaneously extracting and

27

reading comprehension skill in this study was measure by the Thai reading comprehension test.

3.1.3.2 Word recognition skill. The ability to determine the identification of a written

word, i.e., the pronunciation of a word encountered in print or writing. The word recognition skill in this study was measure by a word recognition test.

3.2 Participants

Thai is the standard language spoken officially and nationally by almost sixty-five million people, throughout every part of Thailand. The Bureau of Academic Affairs and Educational Standards (under the Office of the Prime Minister of Thailand) requires that fourth-grade students should have the ability to read words, rhyming words and short passages correctly and fluently. Therefore, this study recruited fourth-grade students.

The participants were 357 fourth-grade students (47.34% boys, 52.66% girls), with a mean age of 10.12 years (9.0–11.5 age range). They were recruited from nine public schools in Loei Province in north-eastern Thailand. This study applied a two-stage sampling

technique (Fraenkel & Wallen, 2006). In loei Province, there are 419 schools, 5499 grade 4 students (50.95% boys, 49.05% girls). The schools under Loei province was divided into three Primary Educational Service Areas (PESAs) based on the Geographical areas, and all the PESAs in Loei adopt the same educational curriculum. Therefore, the first stage, cluster sampling was selected according to the PESAs, and one of the three PESAs was chosen for the study. The schools in the chosen PESA were divided into three strata, based on the number of students in their school, which made the demographic distribution of students in schools within the same strata similar and conversely, different among the strata. Therefore, the stratified sampling technique was used in the second stage. The schools in each PESA were stratified into large, medium and small. Schools were then selected randomly from each

28

of these three strata, and all fourth-grade students in each selected school were tested. The table 1 shows the sample in this study. The initial sampling procedure resulted in 453 students recruited from 9 schools, however, during data collection, sample attrition occurred due to missing data, therefore, 96 students (21.19%) dropped out of the study and the final sample consisted of 357 participants (148 students from 2 large schools, 168 students from 5 medium schools and 41 students from 2 small schools). All students were native Thai speakers and had no known sensory or learning disabilities.

29 Table 1

Study sample.

School Room Boy Girl Total Time 1 Time 2

Drop out (%) Boy Girl Total Drop out (%) Boy Girl Total Phanokao community 1 12 13 25 0.00 12 13 25 28.00 8 10 18 Phukradung community 2 29 49 78 4.00 27 48 75 21.79 22 39 61 Nhong-hin community 2 18 41 59 1.72 17 41 58 16.95 14 35 49 Na-go 1 18 15 33 3.13 18 14 32 21.21 14 12 26 Huy-Som 1 20 13 33 0.00 20 13 33 15.15 17 11 28 Nhongtana 2 29 16 45 9.76 26 15 41 28.89 18 14 32 Phakaw 1 16 14 30 0.00 16 14 30 23.33 12 11 23 Nhongkan community 2 18 23 41 5.13 18 21 39 19.51 15 18 33 Arawan 3 61 48 109 3.81 60 45 105 20.18 49 38 87 Total 15 221 232 453 3.42 214 224 438 21.19 169 188 357

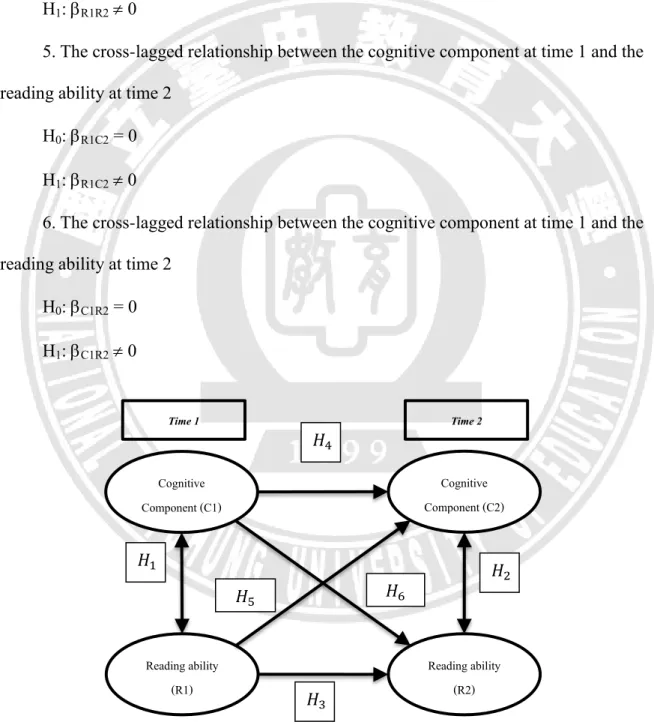

30 3.3 Research Design

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between cognitive component and reading ability of grade 4 students in their reading development over time. To achieve this aim, a two-wave cross-lagged panel design was applied to assess possible causal directions using empirical data. This design was a method of dealing with longitudinal correlations between two variables to determine whether “the history of one variable (X) can predict the other variable (Y) after accounting for the history of (Y)” (Kenny & Harackiewicz, 1979). This type of design allows for the examination of a causal association between two variables measured simultaneously over several time points. Each of the two variables in cross-lagged panel designs is regressed on itself at earlier time points (the auto regression effect) and also regressed on the second variable to test the influence of one variable on another over time. This type of design is helpful in determining the directionality of the relationship between two variables.

The choice of time between observations for a cross-lagged panel model is important. The associations between variables change over time, any autoregressive or cross-lagged effect from the model is specific to the chosen lag. Thus the analyst assumes that a reasonable lag was used, meaning the time to collected data in cross-lagged panel design was not too long or too short and the time was appropriate to see the effect emerge (Selig, 2012). For cross-lagged panel technique, the analysis of three or more waves does have advantages, but when properly specified and using the most appropriate methods, analysis of two-wave data can still provide us with valid inferences about the effects of variable transitions on individual outcomes (Johnson, 2005). Of note is a previous study by Harlaar, Deater-Deckard,

Thompson, De Thorne, and Petrill (2011), which aimed to examine reading achievement and independent reading using two-wave cross-lagged panel design in one year with student age range from 10 to 11 years. The result of study found that reading achievement at age 10

31

significantly predicted independent reading at age 11. Finding of their study indicate that one-year and two-wave of cross-lagged panel design is sufficient to see the effect of reading development.

In the present study, the conceptual model of a cross-lagged panel design using two variables with measurement taken over two times point is presented in Figure 4. In Figure 4, the cognitive component and reading ability scores of students in fourth grade were measured at two times point. This design enabled the researcher to examine whether or not cognitive achievement at the first time point determines reading ability at the later time point. Represented in Figure 4 are three types of relationships:

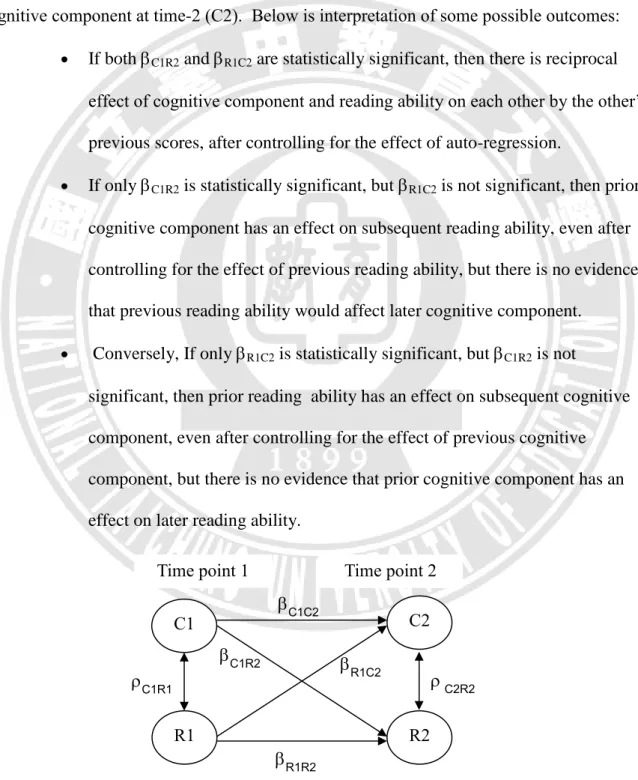

(1) Synchronous correlations between the two variables: These include the

unconditional zero order correlation (C1R1) between the cognitive component (C1) and the

reading ability (R1), both at time-1, and the zero order correlation (C2R2) between the

cognitive component (C2) and the reading ability (R2), both at time-2 after controlling for the other effects in the model. Below is interpretation of some possible outcomes:

If C1R1 is statistically significant, indicated the cross-sectional relationship between cognitive component at time-1 and reading ability at time-1.

If C2R2 is statistically significant, indicated the cross-sectional relationship between cognitive component at time-2 and reading ability at time-2.

(2) Auto-regressive effects of the two variables: These include the effect (C1C2) of the

cognitive component at time-1 (C1) on the cognitive component at time-2 (C2), and the effect (R1R2) of the reading ability at time-1 (R1) on the reading ability at time-2 (R2). Below is

interpretation of some possible outcomes:

If C1C2 is statistically significant, then prior cognitive component at time-1

32

If R1R2 is statistically significant, then prior reading ability at time-1 has an

effect on subsequent reading ability at time-2.

(3) Reciprocal effects between the two variables over time: These include the effect (represented by path coefficient C1R2 in Figure 4) of the cognitive component at time-1 (C1)

on reading ability at time-2 (R2), and the effect (R1C2) of reading ability at time-1 (R1) on

cognitive component at time-2 (C2). Below is interpretation of some possible outcomes:

If both C1R2 and R1C2 are statistically significant, then there is reciprocal

effect of cognitive component and reading ability on each other by the other’s previous scores, after controlling for the effect of auto-regression.

If only C1R2 is statistically significant, but R1C2 is not significant, then prior

cognitive component has an effect on subsequent reading ability, even after controlling for the effect of previous reading ability, but there is no evidence that previous reading ability would affect later cognitive component.

Conversely, If only R1C2 is statistically significant, but C1R2 is not

significant, then prior reading ability has an effect on subsequent cognitive component, even after controlling for the effect of previous cognitive component, but there is no evidence that prior cognitive component has an effect on later reading ability.

Figure 4. A cross-lagged panel design using two variables measured over two time points

C1

R2 R1

C2 Time point 1 Time point 2

C1R1 C2R2

C1C2

R1R2

C1R2

33 3.4 Measurement Development

Measurement development of this study focused attention on the development of a valid measure of each of the underlying constructs. Table 2 provides the measurement

development procedure for the cognitive and reading ability measurement of reading in Thai.

Table 2

Scale Development Procedure.

Development Phase Scale Development Steps

Planning - Conducted a literature review of the competing theories of reading.

Construction - Determined and defined domains of various theories related to reading components.

- Create test items that are distinguishable by domain.

- Conducted expert reviews of all items for content and agreeability validation.

- Fix some items based on feedback from the expert reviews. Validation - Assessed the reliability of the tests.

3.4.1 Planning. Based on the theoretical principles of subscales for reading reviewed in Chapter Two, the researcher identified two domains of reading include cognitive components (morphological awareness, decoding skills and rapid automatized naming) and reading abilities (reading comprehension and word recognition) and then created the items test for each component (see on Table 2).

34

3.4.2 Construction. Three experts reviewed all eight tests consist morphological structure test, morphological production test, phoneme isolation test, rapid word segmentation test, rapid colour naming test, rapid number naming test, reading comprehension and word recognition test to assess their content validity. The experts included two University lecturers with expertise in level Thai and one primary-school Thai language teacher. The objects of the test were given to the panel to evaluate for appropriateness of content, language and clarity of instructions. Table 3 shows the number of items and the total score of each test of reading ability and cognitive component which improve the content validity by expert judgment.

Table 3

Measurements.

Tests Number of items Scoring Total score

Cognitive components Morphological awareness test

- Morphological structure test 15 0/1 15

- Morphological production test 10 0/1 20

Decoding skills

- Phoneme isolation test 15 0/1 15

- Rapid word segmentation test 32 NS 142

RAN

- Rapid colour naming 50 RT -

35 Table 3 (Continued)

Measurements.

Tests Number of items Scoring Total score

Reading abilities

- Reading comprehension 35 0/1 35

- Word recognition 150 0/1 150

Note. 0/1 = incorrect response is scored as 0, correct response is scored as 1; RT = Response time; NS= number of words that were correctly separated.

3.4.3 Validation. In order to develop a scale for cognitive components and reading ability in this study, the log-transformed (Boscardin, Muthén, & Francis, 2008) and

Unidimensional Item Response Theory (UIRT) were applied to get proficiency estimates for each test.

For the morphological structure test, morphological production test, phoneme isolation test, reading comprehension and word recognition scale, instead of using the raw total scores of the ability scale of each test, this study used UIRT measure based on estimates of each person’s latent trait to represent those abilities with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. UIRT models have a strong assumption that each test item is designed to measure some facet of the same underlying ability or a unique latent trait. It is necessary that a test intending to measure one certain trait should not be affected by other traits, especially when only the overall test scores are reported and used as an assessment criterion for various ability levels. For unidimensional constructs, the Rasch model (or one-parameter logistic model: 1PLM) and the two-parameter logistic model (2PLM) are commonly used (Embretson & Reise, 2000). According to Thissen and Steinberg’s (1986) taxonomy classifies some IRT models designed to analyze such test items as “Binary Models”. The 1PLM and 2PLM belong to this