國 立 交 通 大 學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩 士 論 文

作為或不作為一個女人,這是個問題︰

以精神分析論瑪格麗特.艾特伍德之《可食的女人》

To Be or Not to Be a Woman, That is the Question:

Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman in the

Psychoanalytic Perspective

研 究 生:林秀宇

指導教授:林建國 博士

作為或不作為一個女人,這是個問題︰

以精神分析論瑪格麗特.艾特伍德之《可食的女人》

To Be or Not to Be a Woman, That is the Question:

Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman in the Psychoanalytic Perspective

研 究 生:林秀宇 Student:Hsiu-Yu Lin

指導教授:林建國 博士 Advisor:Dr. Kien Ket Lim

國 立 交 通 大 學

外 國 語 文 學 系 外 國 文 學 與 語 言 學 碩 士 班

碩 士 論 文

A Thesis

Submitted to Graduate Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

College of Humanities and Social Science

National Chiao Tung University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master of Arts

in

Literature

January 2010

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

作為或不作為一個女人,這是個問題︰

以精神分析論瑪格麗特.艾特伍德之《可食的女人》

學生:林秀宇 指導教授:林建國 博士

國立交通大學外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

摘 要

此論文採用精神分析的觀點來閱讀瑪格麗特.艾特伍德的小說《可食的女人》

。藉

由精神分析的架構來探討書中的女主角瑪麗安對自己身為女人的自覺,以及分析瑪麗

安作為一個歇斯底里女人的主體性。另外,此論文也將透過闡述到底作為一個女人會

面臨什麼樣問題的過程中,重新檢視瑪麗安和其他角色的關係,並提出有別於其他評

論者對女性氣質的定義。

全文共分成五個部分。第一章簡述此論文題目探討的重要性,以及對這本小說的

文獻回顧和方法論的應用。第二章探討瑪麗安的欲求,除了解釋何以歇斯底里患者的

身體為一充滿情欲的身體之外,也加以說明此欲望實為一未被滿足之欲望,進而探討

瑪麗安的厭食與母親之間的關係。第三章探討瑪麗安對己身性別的困惑和他身為女人

的自覺。在第四章中,我將提出瑪麗安和鄧肯之間的情感轉移是瑪麗安重新恢復健康

和「正常」生活的關鍵所在。最後,經過一連串的探討,我們了解到作為一個女人對

瑪麗安而言是什麼,並藉由精神分析的觀點重新定義女性氣質,因此在結論部分,我

將綜合以上的論點來揭露小說的書名《可食的女人》所要傳達的訊息。

關鍵詞:精神分析、女性氣質、主體性、認同過程、情感轉移、《可食的女人》。

To Be or Not to Be a Woman, That is the Question:

Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman in the Psychoanalytic Perspective

Student:Hsiu-Yu Lin Advisor:Dr. Kien Ket Lim

Graduate Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

National Chiao Tung University

ABSTRACT

This thesis adopts the psychoanalytic perspective to analyze Margaret Atwood’s novel, The Edible Woman. Under the framework of psychoanalysis, we discuss the protagonist’s, Marian’s, awareness of being a woman and also her subjectivity of being a hysteric woman. Besides, this thesis will re-examine the relationship between Marian and other characters via the problems confronted in a woman’s life and offer a new definition of femininity.

The thesis is divided into five parts. Chapter One describes the significance of the thesis topic, the literature review of the novel, and the methodology I will apply for in the following chapters. Chapter Two concerns what Marian desires. In addition to explaining why the hysteric’s body is an erotogenic body, I will further elucidate that Marian’s desire is actually an unsatisfied desire. In this chapter, I will also discuss the relationship between Marian’s anorexia nervosa and her mother. Chapter Three discusses Marian’s sexual confusion and what it is to be a woman for her. In Chapter Four, I want to prove that transference between Duncan and Marian is the key point for the restoration of Marian’s health and her “normal” life. Finally, after a series of discussions, we understand what it would be like to be a woman for Marian and redefine femininity in psychoanalytic perspective. Therefore, in my conclusion, I will combine the above theses to unveil the message hidden in the novel’s title, “The Edible Woman.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing a thesis is like setting out on a mysterious labyrinthine adventure. I have to try several paths which I never trod on or discovered to search the entry to a totally new world. The ways I chose are not always passable and smooth. While some ways lead me to obstacles and sufferings, some surprise me with unexpected treasures, which help me achieve the goal. On the way to accomplishing my thesis, I have obtained many people’s assistance and encouragement, without which I cannot finish my thesis and thus taste the fruit of success. Hence, I would like to take advantage of this acknowledgement to thank them.

My deepest gratitude goes first and foremost to Professor Kien Ket Lim, my advisor, for his consistent encouragement and patient guidance whenever I encounter difficulties or lapse into predicaments. At the beginning of writing the thesis, I felt so frustrated and anxious that I did not possess any courage or motive to write down sentences for my thesis. It is Professor Lim’s phone call, a turning-point ring, giving me enough strength to commence my thesis proposal and subsequent chapters followed up. Besides, although Professor Lim was busy on teaching and doing research, he still spared a great amount of time on meeting my partner, Grace, and me, resolving numerous problems raised by us. I have to admit that every time after talking to him, I feel more confident and peaceful, with which I can proceed further on my thesis and thus accomplish it step by step. The advice and suggestions given by him inspire the production of a large deal of new ideas and bring forward the birth of the thesis.

Besides my advisor, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee members: Professor

Hsin-Chun Tuan and Professor Ming-Min Yang, since they as well devote much time to read the novel and my thesis and do offer insightful comments and worth pondering questions on my thesis.

I am also heartily thankful to my friends, all of my classmates, staff, and professors at the Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics in NCTU: Elsa, Jason, Jade, Terence, Howard, Hung-Tao, Tuan-Jung, Pei-Hsin, Cindy, Ya-Ling, Lu-Ying, Professor I-Chu Chang, Professor Pin-Chia Feng, Professor Eric Kwan-Wai Yu, and Professor Chia-Yi Lee, just to mention a few. This thesis would not have been possible without their help and support intellectually and mentally. In particular, I would like to express my

gratitude to my partner and as well my best friend, Grace, whose encouragement, enlightenment,

consideration, and support from the initial to the final level have enabled me to develop one chapter after another. Moreover, the books she recommended to me are profitable enough to open a new door for my thesis. Also, I owe my deepest gratitude to Wen-Hung, who lent me his computer to assist me in

composing my thesis and usually took me to the gym to relieve my nerves.

My sincere thanks also go to the whole members of Tin Ka Ping Photonics Center, who have accompanied me on those unbearable thesis writing and IELTS preparation days, especially Roy,

Shiau-Shin, Ming-Hua, Bo-Siao, Jia-Yang, David, and Hsiao-An, all of whom have given me the most substantial favor and bring a lot of happiness to my boring life.

Last but not least, I am forever indebted to my family and many aunts who take care of me after my mother’s death. Their understanding, endless encouragement, and selfless love provide me the utmost

strength to confront the low tide of my life and pursue my dreams. I would like to dedicate my thesis especially to my father, who has made available his support in numerous ways and take the responsibility

for being both a competent father and mother through these years. Without his financial and spiritual support, I could not even have started writing this work!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page …..………..ii

Chinese Abstract ………...………….iii

English Abstract ……….………iv

Acknowledgments ……….……..v

Table of Contents ………..vii

Chapter One: Introduction……….………..…….1

Chapter Two: What does Marian Desire? ...22

Chapter Three: Marian’s Sexual Confusion ...52

Chapter Four: Transference and the Title “The Edible Woman” …...…………79

Chapter Five: Conclusion……….….…………102

Chapter One: Introduction

1.1. Margaret Atwood’s Writing Motive and Plot Summary

Margaret Atwood admits herself that during the process of writing The Edible Woman in 1965, she had “been speculating for some time about symbolic

cannibalism” (EW 7). As she is especially fascinated by “wedding cakes with sugar brides and grooms” (EW 7), the title of the novel, “The Edible Woman,” is more or less related to Atwood’s early experiences. As we shall see, the heroine, Marian McAlpin, is a twenty-four-year old rookie who has just graduated from the university and works at a marketing survey company. She lives on the top floor of a once

well-to-do noble house with her roommate, Ainsley, in Toronto. Ainsley is at the same age as Marian, though a few months older. For her, a woman can only fulfill her deepest femininity via the process of pregnancy. In light of this, she dresses herself up as a virginal schoolgirl and traps Len, Marian’s college friend who just comes back from England, to impregnate her. However, Ainsley’s decision of rejecting Len to be the father of the baby makes him become insane at the end of the novel. When Marian studies in college, she has another good friend, Clara, who still keeps in touch with Marian even though she is already married to Joe and is now a pregnant housewife and a mother of two. Marian also has a boyfriend, Peter, who will become her fiancé as the novel develops.

In the novel, it is evident that Marian has transformed from a “normal” woman into a hysterical one, who develops anorexia nervosa, eccentric behaviors, and unexplainable fantasies, and returns to her former state as if nothing has actually changed. As Atwood claims in the “Introduction,” “It’s noteworthy that my heroine’s choices remain much the same at the end of the book as they are at the beginning: a career going nowhere, or marriage as an exit from it” (EW 8).

After having several conversations with Duncan, who is a graduate student of English Literature and who runs into Marian at the laundry after their first meeting in a questionnaire interview, Marian not only has an affair with him but recovers from the eating disorder later on by devouring the cake-woman, which is baked by herself and is bestowed a symbolic meaning. Overall, the relationship between Marian, Duncan, and Peter is so complicated that I want to analyze it and offer a different point of view to look at the novel.

1.2. Main Argument and Significance of My Topic

At the moment when Atwood published her first novel, The Edible Woman, in 1969, it witnessed the significant rise of North American feminism. Although Atwood herself regards the novel “as protofeminist rather than feminist” since there was still “no women’s movement in sight” when she “was composing the book in 1965” (EW Introduction), many critics, including Lisa Jane Rutherford, Coral Ann Howells, and J. Brooks Bouson, read the novel in the feminist perspective since they respectively believe that The Edible Woman displays “the objectification, fragmentation, and consumption of female desire in contemporary Western society” (Rutherford iii), explores the “artifice and fantasy involved in representations of the female body” (Howells 38), and reveals Atwood’s “rejection of her own femininity” (Bouson 72).

What I find is that these critics share this common viewpoint: they want to know “what” a woman is, but they take a unilateral view to simply examine “what” a woman is under the gaze of men. The critics are so preoccupied with patriarchal mechanism without taking a closer look at the woman herself on how she may unconsciously think who she is. No doubts, their works are influential and important since they offer us a way to problematize the normalized relationship between men and women. Nevertheless, they neglect to problematize Marian herself, the

protagonist of The Edible Woman, whether she is a “woman” or not. In this way, I want to adopt the psychoanalytic perspective to analyze the novel because when most critics focus mainly on how Marian protests against the patriarchal context, they nonetheless ignore what Marian unconsciously desires and the fact that Marian confuses herself as a woman. In other words, while critics render Marian’s hysterical symptoms as a common phenomenon among Canadian women to express their dissatisfaction and rancor towards the patriarchal ideology, these critics overlook Marian’s individuality as a hysteric woman. What I mean is that although women are generally treated as an object of exchange by the phallocentric institution, they do not adopt an identical attitude and their reactions may vary. For example, some women can live undisturbedly as though patriarchy is part of their life, whereas some will rebel against the gender inequality in their daily life radically as if they represent the spokespersons of every oppressed woman. Still others may superficially coexist with the patriarchal system, but unconsciously they know something has gone wrong. So they fall prey to their hysterical symptoms at a specific moment. My thesis therefore intends to discuss those women who suddenly turn into hysterics without knowing why. Since so many critics have tackled the problems and the relationship between patriarchy and the persecuted women as some feminists used to hold, I attempt to offer a different view to analyze the inner struggle and the psychical predicament of the hysterics in the psychoanalytic perspective. To put it another way, I will employ psychoanalysis to analyze what it is to be a woman for hysterics and re-define what femininity is besides the feminist interpretations. Now, I intend to re-examine the present Margaret Atwood scholarship on The Edible Woman, pointing out their contribution and deficiency, to which I hope my thesis can offer its new findings.

Since my topic concerns what it is to be a woman and what femininity is, I will put an emphasis on the literature concerning femininity and psychoanalysis. As a result, I would like to divide my literature review into three main groups: the feminist reading, the comparison of Alice in Wonderland and The Edible Woman, and the psychoanalytic perspective. I include a literature review on the comparison of Alice in Wonderland and The Edible Woman not only because Alice in Wonderland is

mentioned in The Edible Woman but because both Alice and Marian are puzzled by the same questions of “what I am” and “what a woman is.” Besides, while Alice makes her journey, which causes her to doubt her identity, during her sleep, Marian also realizes what she is in a world between reality and fantasy.

Let me begin from the feminist literature review. Most feminists pay attention to how women are exploited and reduced to the objects of exchange, infantile status, and self-diminished conditions by the powerful patriarchal ideology. The feminist commentators thus define that femininity is a “mystique” and “inauthentic” product created by the male-centered society in order to control women’s behaviors and mind. For instance, in “‘Feminine, Female, Feminist’: From The Edible Woman to ‘The Female Body,’” Howells appropriates Betty Friedan’s view in The Feminine Mystique, which criticizes the feminine mystique as based upon domesticity and social

exploitation of the female body, to examine the two protagonists in Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman and her little fable “The Female Body” respectively. Howells contends that The Edible Woman, which prefigures the early 1990s postwar feminism in the history of North America, can be treated as a rebellion against the social myths of femininity in the contemporary society. Commenting on consumerism and the advertising campaign, Howells unveils the secret of the feminine mystique, in which women have actually lost their independence and subjectivity. Concealed by the image of pleasant domesticity, they are transformed into dependent objects in the

marrital relation as good housewives and mothers. Therefore, in her opinion, Marian’s eating disorder is a hysterical protest since “Marian’s body speaks its language of rebellion against the socialized feminine identity that she appears to have already accepted” (47) by resisting consumption and herself being consumed. I partially agree with her that patriarchal system indeed forms a “feminine mystique” of femininity, in the masculine constructions of which women are treated as an “other” such as a child-like doll image and an object of exchange, rather than a complete human being, since women are not only silent but silenced without having their own identities or voices to express their feelings and desires (57). However, I also doubt that patriarchy is the only reason to have caused Marian’s hysterical symptoms. Since Marian is not the only persecuted woman in this patriarchal society, why her but not others?

To sum up, for Howells, the current concepts of femininity are filled with

“mystification” and “inauthenticity” (40). She goes on: “In North American society of the late 1950s and 1960s […] ‘adjustment’ for a woman meant accepting a dependent ‘feminine’ role […]” (42). Accordingly, Howells keeps censuring the “cultural

definitions” of femininity since in her opinion femininity is a kind of product of patriarchy. No doubt the oppression of the patriarchal system is one of the reasons that has caused Marian to generate traumas and hysterical symptoms. But it is not

objective enough to blame all things on the patriarchal society alone. How about Marian herself? Is she always a victim? Are all of her unusual actions aroused by gender inequality and social oppression? Or, is it possible to decipher her abrupt and unreasonable conducts not only from outside but from within herself? Besides, except for the “mystification” and “inauthenticity” of femininity, are there no other

“clarification” and “true essence” of femininity, which can barely be detectible, are invisible but can exist as such?

Bouson suggests:

The Edible Woman dismantles and demystifies the marriage ideal by laying bare what has long been naturalized—and hence ignored—in the traditional romance scenario: the painful objectification and

self-diminishment of women in a male-dominated order. (91)

In other words, like Howells, Bouson also claims that femininity, which means the elimination of self-identity and the objectification of a woman, is granted by the patriarchal order as a masquerade. In her view, femininity for a woman is like transvestism for a transvestite, so “femininity is a role requiring make-up, costumes, and well-rehearsed lines . . . in order to be properly performed” (82). As Eleonora Rao contends, the red dress and the mask of make-up Marian wears for the party represent “the entry into femininity” (136). Rao continues that femininity is “a construct of male desire, and effectively portrays the process as a masquerade, as Luce Irigaray has called Freud’s notion of femininity.” Rao summarizes Freud’s words thus: “It is necessary, according to Freud, for the girl to make the painful transition, to ‘pass from her masculine phase to the feminine one’ in order to become a normal woman” (136). In light of this, we find that Rao believes that femininity is produced as a masquerade via the intention of patriarchal context. Nevertheless, she garbles Freud’s statement to claim that femininity should be always based on men’s desires. In my opinion, what Freud proclaims is that every child, including the little girl, thinks at first that he or she has a penis. However, one day as the girl finds that she is “castrated” as her mother, she must then identify with her father and develop “penis envy.” It is hard for a girl to accept the fact that it is as if she had already been “castrated.” As we shall see, as some girls cannot accept this seeming fact they become hysterics. Rao’s

misinterpretation of Freud’s words brings out her own interpretation of “feminine masquerade,” which accords with Irigaray’s viewpoints. Therefore, it is in this light

that Rao appropriates Irigaray’s words to say this on masquerade:

The masquerade represents the moment in which women try to

“recuperate some elements of desire, to participate in man’s desire, but at the price of renouncing their own. In the masquerade, they submit to the dominant economy of desire in an attempt to remain “‘on the market’ in spite of everything.” For a woman this movement signifies the “entry into a system of values which is not hers, and in which she can “appear” and circulate only when enveloped in the needs/desires/fantasies of others, namely, men.” (136)

In short, if accepting femininity means only objectifying oneself or performing a gender according to Howells, Bouson, and Rao, then the discussion remains stagnant since no matter what we say, femininity will come to the same conclusion that it is the product of patriarchy. Actually, it makes me ponder whether it is a rule that as long as women live in this patriarchal society, their subjectivity will first be deprived and have then to struggle and fight against the established patriarchal system so to recuperate their subjectivity. To break through the predicament and the limitation of the feminist reading, I attempt to use psychoanalysis to plumb something new. Therefore, since most of these critics note the importance of feminine masquerade, I would like to go back to Joan Riviere’s “Womanliness as a Masquerade” to offer a different perspective to understand why women perform “feminine masquerade” in front of men.

Unlike Rao’s interpretation of feminine masquerade as a way to accept femininity, Riviere declares an opposite statement that “women who wish for

masculinity may put on a mask of womanliness to avert anxiety and retribution feared from men” (91). A woman, especially an intellectual woman who displays excellent performance in her career in the public, will unconsciously disguise herself as a

castrated woman in front of those “potentially hostile father-figures, such as doctors, builders, and lawyers.” Being “castrated and reduced to nothingness, like the mother” in her fantasy, she is afraid of these father figures, who will castrate her in vengeance. As Riviere recounts, a woman’s successful exhibition of her competence in public is a way to signify “an exhibition of herself in possession of her father’s penis, having castrated him” (93). Therefore, womanliness is a protective mask, which hides the woman’s masculinity and averts the threat of castration and the expected reprisals. For fear that she might be found to possess the father’s “penis,” she placates and appeases the father figure by “showing him her ‘love’ and guiltlessness,” and many men will be seduced in this way and give her the reassurance she needs (99). In addition to

providing a different perspective to see what feminine masquerade is, I will also apply Riviere’s theory to analyze Marian’s roommate, Ainsley’s problematic way of

dressing up and expressions in front of men and women. Instead of regarding her “innocent” temperament as a “gender performitivity,” which is naturalized by the patriarchal system, I argue that her womanliness is rather a masquerade to hide her masculinity from the menace of castration and expected reprisals. The most important is that she even uses her womanliness as a weapon to get what she has longed for, the father figure’s “penis,” which for her is equal to having a child without the father. In other words, the child somewhat fulfills her wish of having her own “penis.” Likewise, Marian also wears her feminine masquerade to prevent herself from the danger of castration, and to become the phallus for Peter. I will enlarge this point in my subsequent chapters.

Also, many critics have compared The Edible Woman to Alice in Wonderland because both novels question the protagonists’ identities as a woman by introducing the magic power of food. While Marian in The Edible Woman understands what a woman is through the process of anorexia, Alice in Alice in Wonderland questions her

identity via eating magic food, which causes the size-changing in her female body. The food is not just food in both novels since it is granted a symbolic meaning to help the two protagonists find out what it is to be a woman. As the text reveals, Atwood herself has created a role, Fish, who is an English graduate student devoted to the study of symbols in literature, to give readers the premonition of the subsequent development of Marian’s anorexia. As Fish claims, Alice in Wonderland is a story about a little girl descending into the very suggestive rabbit-burrow, which symbolizes her pre-natal stage, trying to find “her role as a Woman” (194). To Gelnys Stow, both Atwood and Carroll use “nonsensical techniques and allusions” to comment on the traditional female role and the insane society she lives in. As a feminist, Stow remarks,

It is only when Marian rejects social expectations and takes responsibility for her own actions that she can begin to eat again; and the cake that she devours and destroys is of course a deliberate symbol of the artificial womanhood which her world has tried to impose on her. (90)

Also, in Barbara Hill Rigney’s account, Marian’s body is like Alice’s, which is subject to a sudden metamorphosis, such as transforming into a small figure or into a giant by eating specific drinks or food. Likewise, Marian’s mental state is symbolically

changed into different “sizes,” as in one of the examples in which she has gazed at her small silvery image reflected in the bowl of the spoon: “herself upside down with a huge torso narrowing to a pinhead at the handle end. She tilted the spoon and her forehead swelled, then receded” (EW 146). As we can observe, food possesses the power to control the size of the female body, and becomes one of the means for the protagonists to search for their identity as a “Woman.”

Finally, since the novel is regarded by most commentators as a feminist writing, I have found very few articles that read the novel in the psychoanalytic perspective.

The only exception is probably Sonia Mycak’s essay, “The Edible Woman: The Split Subject as Agent of Exogamous Exchange.” In this article, Mycak points out that the construction of an individual subjective position is closely linked with the dynamics of the symbolic society such as “dynamics of circulation, consumption, and

commodification, and relations of marriage, sex, and signification” (47). Nevertheless, while society and the subject are symbolic, “they are also divisive,” so Marian

disintegrates her sense of self and is unable to unify her multiple and fractured identity in the social commentary. In this way, Mycak wants to examine the issue of the split subject within its socio-symbolic milieu by combining “structural

anthropological and psychoanalytic ideas” (48).

Mycak further argues, “Marian’s self-imposed starvation becomes the symptom of an inability to circulate within exchange and a regression to the asymbolic” (50). She re-examines Marian’s subjective position in the Lacanian method and reconsiders the relationship between the subject and the object in light of “the Hegelian

master-slave dialectic” (63). She is concerned with how Marian returns to the

imaginary stage or the mirror stage proposed by Lacan from the “old” symbolic world, and then goes back again to a “new” symbolic world, via the process of anorexia. As we can detect, the thesis she wants to offer is more or less what it is to be a woman for Marian since what she discusses is Marian’s split subjectivity. However, what Mycak is most concerned with is still confined to the sphere of the relationship between the subject and the object, or the master and the slave. In other words, she still has not put the distinction of genders under scrutiny, but regards a man as Man and a woman as Woman. She puts emphasis on searching for Marian’s identity as a woman by positing her in a fixed position of Woman without detecting the hysteric’s general confusion of sexual difference. What I mean is that if she mentions that Marian returns to the imaginary stage, in which a young child still cannot discern what sexual difference is

but can differentiate the one with the phallus and the other without it, it is defective to simply discuss Marian’s identification with woman without mentioning her

identification with man. Nevertheless, although Mycak does not break her issue away from the limitation of gender problems, she pays more attention on Marian’s inward thinking than most feminists do, who concerns social exploitation of women rather than the predicament within Marian’s subjectivity. Thus, I want to offer some

suggestions to complement Mycak’s argument. In other words, while Mycak offers a different interpretation of Marian’s commodification “in terms of the individual subjective stance” rather than “in general terms of social exploitation” (49), I analyze Marian’s hysteria in respect of her childhood trauma and anxiety rather than simply in terms of her relationship with the patriarchal society.

Overall, instead of putting Marian in the position of the otherness, which is oppressed and objectified by the patriarchal society as many critics have pointed out, I view Marian as a hysterical case study, such as Dora’s case, to discuss her desires, her sexual confusion, and her transference towards Duncan. I want to decipher the codes behind Marian’s hysterical symptoms via the analytic method of psychoanalysis and to give the readers another perspective to read the novel not only from the feminist viewpoint but also from the psychoanalytic one.

1.4. Why is Marian a Hysteric?

Before we delve into the discussion of what it is to be a woman for Marian, some might raise the question: In what way is Marian a hysteric? Nowadays in the West, many insist that hysteria has already disappeared. We even hear more or less that hysteria is replaced by the term “femininity” (Mitchell 186) or feminine disease. According to Juliet Mitchell, the above comments are an incorrect impression of hysteria since hysteria still exists in our lives and is never the disease privileged to

women. She takes the examples of dreams and the slips of tongue or pen to denote that “women and men do not produce sexually differentiated symptoms” since there is no gender difference in the unconscious. We can only report that women are prone to develop the hysterical symptoms than men, but there is no such thing called “female” hysteria. To approve Mitchell’s view, I will enumerate Len’s case in the novel as a piece of evidence to affirm that men can also be attacked by hysteria.

I regard Marian as a hysteric for the following reasons. First, she is attacked by serious hallucination that she blends reality with her fantasy together without

distinguishing them. According to Josef Breuer, Anna O. often indulges in her hallucination “filled with terrifying figures, death’s heads and skeletons” (27). Likewise, when Marian immerses herself in her hallucinations, in which she cannot see herself but the dead rabbit, the terrible hunting images, and Peter’s isolated future, she is full of anxiety and horror as Anna O. is in her own hallucination. Next, Marian does not feel any pleasure or orgasm in sexual intercourse. According to Juan-David Nasio, a hysteric’s body “suffers from being an outsized, cumbersome phallus with a hole in it in the genital region,” so her genital parts cannot feel any jouissance; instead, her “erotogenic body” as a phallus is the place where she feels the unbearable

pleasure. Third, Marian expresses strong cravings for love, through which she

generates a serious eating disorder. As Breuer and Freud observe, some hysterics have eating problems, including Anna O., and Frau Emmy von N., not to mention Dora. Their eating disorder or anorexia nervosa is not simply the physical disease since their anorexia is usually accompanied more or less by phobia, which can be related to their traumas in the past or psychical problems they face now. For example, while Anna O. finds it impossible to drink because of the horrid dog she has once met (Breuer, 34), Emmy von N. shows her disgust at the meat because of her childhood trauma (Freud 1895d, 82). Moreover, the hysteric’s anorexia has a lot to do with the lack of love. As

we can see, while Emmy von N. loses her appetite right after her husband’s death, Marian’s first symptom of eating disorder appears after she consents to Peter’s proposal. Fourth, as Marian usually wants to involve others, she usually gives the surrounding people a hard time. As Mitchell mentions, the hysteric is unmanageable, for the reason that they have urgent need and ability “to involve the other, as Anna O involved Breuer” (196). Finally, Marian has sexual confusion as almost every hysteric may encounter. According to Mitchell, the hysterical girl cannot accept the fact that she is “already castrated” but instead “she identifies with her father to possess her mother, and with her mother to possess her father” (187). To put it another way, the hysteric will rather identify with a man’s desire and with a man than with a woman since except for the fact that she cannot break through the ordeal of castration, the hysteric is perplexed by the question of what it is to be a woman since women are always a mysterious enigma for her, and she believes that she can find an answer to it.

1.5. Proposal Summary and Methodology

In The Edible Woman, we observe that the protagonist, Marian, who possesses an excessively high morality and anxiety, has transformed from a “normal” woman to an anorexic, and then returned to her “normal” life again. By appearance, the novel describes the process of how an anorexic woman is cured abruptly without any doctor’s prescription or help. However, if we investigate the causes of Marian’s anorexia, the relationship between her and other characters, and the narrative

mechanism of the whole novel, we will discover that Marian’s “abnormal” behaviors and eating disorder are not so much simply physical changes as psychical rebellions. As we can observe, her hysterical symptoms such as her unexpected escape from people, her phobic anorexia, and her sudden paralysis, a result from the explosion of her long-time repressed affect, which is combined with many incompatible ideas and

has no way to find a discharge. Therefore, to untie the secret behind “the edible woman,” we should not regard food as simply nourishment, symptoms as physical pains, and most significantly, a woman as “woman.” To regard Marian as a hysteric woman in view of psychoanalysis, my thesis attempts to argue that what it is to be a woman for Marian and what the title, “The Edible Woman,” implies has to do with Marian’s desire, sexual confusion, and transference for Duncan.

In short, my thesis contains five chapters, including the introduction, three main body chapters of the former mentioned arguments, and the conclusion.

Chapter One is the introduction. In this chapter, I will show that the

contemporary critical conversation of what a woman “is” instead of what a woman “should be” makes my thesis title significant. Since Atwood writes this novel at the rise of North American postwar feminism in 1960s, I will re-examine what femininity is and what it is to be a woman in the psychoanalytic perspective, but not in the feminist point of view. In other words, differing from the feminist interpretation that femininity, as derived only from the patriarchal mechanism, is full of mystique and inveracity, the femininity I want to elucidate and decipher is an identification starting from the childhood and a task of castration. In this way, I will at first give a historical review of the scholarship, which focuses on discussing femininity and the issues of what a woman is in The Edible Woman. And then, applying the cases of Anna O., Emmy von N., and Dora and comparing them with Marian’s unusual demeanors, I will prove that Marian is in fact a hysteric. In light of this, Dora’s case and the dream of the butcher’s wife1 are helpful for us to understand Marian. In addition, since the methodology I am going to use is psychoanalysis, I will narrate why I adopt the

1

In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud takes the example of his female hysteric, the butcher’s wife’s dream, to prove his assertion that “all dreams are fulfillments of wishes” (146). By analyzing her dream, we also discover the nuance of identification between the hysteric and other women. Therefore, I intend to take the example of the butcher’s wife to interpret Marian.

viewpoints of Sigmund Freud, Joan Riviere, Jonathan Lear, and most importantly, Jacques Lacan. In order to explain the relation between the female body and the landscape in the novel, I will also borrow J. Douglas Porteous’s ideas.

Chapter Two concerns what Marian desires. As the text discloses, Marian herself neither figures out why she keeps giving others a hard time, nor comprehends what makes her act out those irregular behaviors. Therefore, I will first use André Green’s idea that “my knowledge is one of knowing not that I know” to elucidate that Marian resists to be treated as a consumed object by Peter, her colleagues, and the

exploitative male-centered society, so that her repressed affect is thus converted to her body, or more precisely, to her erotogenic body. To explain that the hysteric’s body is not an organic body, but an erotogenic body, I will use Monique David-Ménard’s view to illustrate that Marian’s weird conducts and anorexia are her ways to experience “pleasure,” which goes along with pain, all derived from her five-year-old childhood body. Next, I contend that what Marian desires is an unsatisfied desire. When Marian makes love with Peter, she remains absent from the lovemaking scene by imagining what reason it is that makes Peter make love with her each time and why Peter chooses the bathtub as the place to make love this time. Linking the bathtub to the drowned woman, Marian also develops the fleeting vision that she and Peter die accidentally in the bathtub, and the scene is later misinterpreted by the next apartment-renters as a suicide for love. Marian even observes the decoration and arrangement of Peter’s bathroom, recalling the first time she met Peter at a garden party following her graduation and the first time they make love. As a result, instead of indulging herself into the process of lovemaking and uttering erotic words to express her bliss, Marian feels only “rotten” even though she tells Peter that it is “marvelous” to make love with him. Here, I will use Nasio’s viewpoints to demonstrate that Marian does this on purpose to make herself never reach the

jouissance, since the hysteric lives the psychical life of fear and of persistent refusal to experience the utmost pleasure, a pleasure which she deems that once she reaches it, the wholeness of her being will be placed under the threat of full collapse and disappearance.

Secondly, Marian’s unusual behaviors which happened during the meeting with her friend, Len, such as her sudden weeping without proper reasons, the unexpected running away from her friends, and her slipping under Len’s bed, result from Marian’s overwhelming anxiety. She does not know how to deal with it but behaves in her own structured, idiosyncratic way to appease it. Here, I will use Jonathan Lear’s revision of Dora’s case in his chapter “Transference” to illustrate how Marian tackles her overflowing anxiety. Besides, that Marian escapes from others does not mean that she prefers to stay alone; on the contrary, she wants to involve and manipulate others by being the only “phallus” pursued by others. Nevertheless, since the chase is no longer a game but is transformed into a hunting movement in Marian’s imagination, Marian’s castration anxiety is also aroused since she imagines herself as a phallus. In short, what Marian wants is not only “being adjusted,” but also manipulating and grasping others’ attention by fantasizing herself as a phallus.

Finally, Marian’s anorexia, which is accompanied by phobia, reveals her eager craving for love from Peter and the rejection of her mother’s suffocating love. Even after a series of Marian’s eccentric behaviors, Peter proposes still to Marian. However, Marian develops eating disorder in return, for she thinks that Peter marries her

because she is suitable to be his wife, but not because Peter loves her as Marian. As Freud points out in “Mourning and Melancholia,” as mourning, melancholia “may be a reaction to the loss of a beloved object,” which “may not really have died” (205). Marian becomes gradually unable to eat because she mourns the loss of “former” Peter, who differs from the domineering Peter and whom she loves, so that she

“assimilates” the “dead” Peter and “destroys” both herself and him by rejecting the nourishment of food. Besides, since food is bestowed a symbolic meaning by patriarchal cultures in Kristeva’s view (Powers of Horror 75), Marian’s rejection of food can be regarded as a way of resisting her femininity since she refuses to be castrated and to enter the symbolic order. In addition, although there is no clear description of the relationship between Marian and her mother, we can observe that the mother-daughter bond between the landlady and her daughter is duplicated in the relationship between the landlady and Marian. In this way, in spite of the fact that the landlady never specifically forbids Marian and Ainsley to do anything, Marian feels that she is in fact “forbidden to do anything” (16) as the landlady’s infantalized daughter. Hence, the original trauma of Marian’s eating disorder should probably be traced back to the relationship between Marian and her mother, for Marian cannot bear and accept her mother’s “imperative” and “tyrannical” love any longer.

Chapter Three discusses Marian’s sexual confusion and what it is to be a woman for her. In this chapter, I would take the example of Dora’s case to discuss what a woman is in the Lacanian view rather than in the Freudian perspective since Freud has treated Dora roughly as a homosexual when she is confronted with Frau K.’s female body, Lacan on the contrary re-examines Dora’s identification from her childhood. In the novel, we cannot find any evidence to prove that Marian has homosexual

inclination, but we more or less sense the divergence between Marian’s identification and that of other women. Therefore, I decide to use Lacan’s viewpoints to manifest what it is to be a woman for Marian and to define what femininity is.

First, Marian wants to be the signifier, the phallus, for the Other’s desire, rather than to be simply the object of the Other’s desire. Instead of identifying with other women, she identifies with men and their desires. Here, the butcher’s wife’s dream can help us better understand the context of Marian’s identification. As we can

discover, Peter is Marian’s lover and the one she wants to marry, so Marian yearns to figure out what he desires and hankers for being the only signifier for his desire. Since Peter has once complimented Ainsley, Marian identifies with his desire and therefore identifies with Ainsley by changing her appearance and way of dressing up to accord with Peter’s sexual objects. In this part, I will appropriate Freud’s viewpoints to explain why men love prostitutes and why the penetration of virginity is a taboo. As for the question why women dress and behave as innocent girls, I will use Joan Riviere’s idea of “feminine masquerade” to expose that women would wear the mask of womanliness to conceal their wishes for masculinity and to evade the threat of castration since the father figures want to inflict punishment on them for seizing their fathers’ penises. Moreover, according to Riviere, as the man’s love will also give back the woman her self-esteem (95), the feminine masquerade is in this way an approach to obtain men’s reassurance. Nevertheless, to be only men’s sexual objects cannot satisfy Marian since in her fantasy, she should be the signifier, the phallus, for

everyone, especially for Peter, her former lover, and for Duncan, her subsequent lover. As we can see, Marian’s maternity is aroused by Duncan, who is depicted as Jesus Christ, and like Dora, Marian wants to be the Madonna, the virgin goddess who is desired but may not be acquired by men and who bears her own “phallus,” Jesus Christ, as the signifier. In light of this, I will explain that she becomes frozen in front of the camera because as a phallus, her castration anxiety is aroused. Finally, I will elaborate Marian’s identification with Clara, the pregnant woman, to explain Marian’s contradictory identification with her suffocating mother.

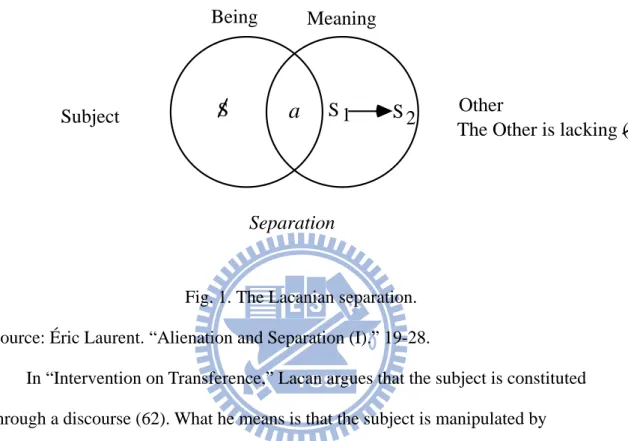

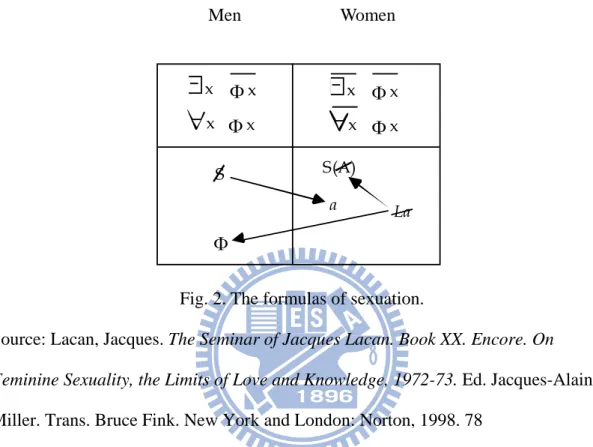

In the following section, I want to distinguish the nuance between “what I am” and “what I should be” by using the Lacanian mathemes of the subject and the being. I intend to discuss this because the novel has defined the difference between feminine role and core. Therefore, I want to use the Lacanian mathemes to re-define what has

been put on display in the novel. After discussing the issue of “what I am,” I will extend the subject further to the issue of “what it is to be a woman.” In this part, I will point out how Marian looks upon her own and other people’s female bodies and most significantly, what Marian thinks of being a woman.

In Chapter Four, I want to prove that transference between Duncan and Marian is the key point for the restoration of Marian’s health and her “normal” life. First, I will use Lear’s interpretation of transference between Dora and Freud to examine the relationship between Marian and Duncan. In other words, while Freud is ascribed to the “Herr K position” by Dora, Duncan is placed at the “Peter position” in Marian’s idiosyncratic way of tackling her anxiety. In addition, Duncan makes Marian

understand what a woman is by taking her to climb the mountains, by way of which, Marian experiences a “pregnancy fantasy.” Here, I will use J. Douglas Porteous’s viewpoint of “bodyscape,” the relation between female body and landscape, to show that the journey of mountain-climbing is actually the medium for Marian to

comprehend what it is to be a woman. As Porteous indicates, “The vision of a landscape as a female body is a common literary theme” (7). For instance, Stella Gibbon’s Cold Comfort Farm (1938) regards the earth as “a great, brown outstretched woman” and “the stem of a young sapling as phallus,” or “buds as nipples” (7). Therefore, when Marian climbs the hills, passing through bridges, she not only

re-examines the female body but also gives herself a new birth. Besides, since Duncan has claimed that he lives in “a world of fantasies” (263) as what Marian usually plunges in, their conversations are somewhat like the ones between the analyst and the five-year-old child of Marian’s erotogenic body. I will apply Freud’s The

Interpretation of Dreams to treat the whole process as a dream-work because according to Freud, daytime phantasies are like dreams (530). Besides, the talking cure between Marian and Duncan can more or less be seen as the act of

“chimney-sweeping” between Anna O. and Breuer, since what Duncan and Marian explore is a “female body,” which can also be regarded as Marian’s imaginary body.

Talking of “pregnancy fantasy,” the famous cake-woman scene is a way as well for Marian to experience what a woman is. This scene has been discussed by almost every critic as either a successful escape from, or as another enmeshment into, the field of patriarchal system or the exploitative capitalism. I want to lay aside the former concern of the relationship between Marian and the society; rather, I would focus on the question about what the cake may represent for Marian, or more

precisely, what kind of mood and status Marian possesses when she eats up the cake. Besides, while she devours the cake and terminates the aggravation of her anorexia, does it mean that she is ready to accept her femininity, or as Dora, she still presents a case of failure? In my opinion, as Marian makes the cake into a woman who satisfies Peter’s expectation, she makes it through the gaze of a man. And yet, when she presents the cake as a substitute of herself in front of Peter, he refuses it and flees away. Since the cake has been interpreted by many critics as femininity, Peter’s escape can be regarded as that his castration anxiety is aroused by Marian, and this time, he cannot confront it. Although Marian eats up the cake, which is equal to accepting both her castration and femininity, we still cannot assert that Marian is completely cured, for she might still identify with a man who tastes the cake-woman, and her sudden bulimia is actually another hysterical symptom. Therefore, I cannot stand on either side of whether the ending of the story presents a success or a failure for Marian. Nevertheless, as Nasio contends, everyone can be a hysteric. As in the example of Peter and Len, we can only suggest that Marian is temporarily “cured,” but we cannot be assured that she will not be attacked by hysteria again when she reenters another work place or falls in love with another man.

Marian’s desire, to her sexual confusion, and then to her rehabilitation, we understand what it is to be a woman for Marian and redefine femininity in psychoanalytic

perspective. Therefore, in my conclusion, I want to disclose what the title, “The Edible Woman,” means by combining my theses above. For me, the title reminds me first of the cake-woman. It is not only the task of castration existing in our daily life but also the condition in which we all might be enmeshed at a specific moment. We cannot avoid it. All we can do is live with this castration.

Chapter Two: What does Marian Desire?

It is evident that many critical debates have discussed the principal question of what and how Marian desires, but there is still something they ignore to detect, which remains thus unresolved. For instance, while Coral Ann Howells argues in ‘“Feminine, Female, Feminist”: From The Edible Woman to “The Female Body”’ that what Marian longs for is the liberation from the social myths of femininity and the feminine

mystique, both of which are naturalized and normalized by the restrictive social rules within the patriarchal culture, Jennifer Hobgood explores in “Anti-Edibles: Capitalism and Schizophrenia in Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman” how Marian desires by examining “the moment between the deterritorialization and reterritorialization of desire,” two terms which are Deleuze’s and Guattari’s terminology (Hobgood 148). Nevertheless, the “desires” the critics concern are confined in the interaction between Marian and the contemporary society. Thus, although in this chapter I attempt to expound what Marian desires, the perspective I provide differs from those of the previous reviewers, who put more emphasis on the relationship between an oppressed woman and the general social context than on Marian herself, the unrecognized unconscious desire of a hysterical woman in her. To unsettle the confusion of what Marian desires, which she herself does not know but which is latently implicated in the description of the novel, I divide this chapter into three parts: desiring an unsatisfied desire, wishing to manipulate others, and craving for love.

2.1. Desiring an Unsatisfied Desire

2.1.1. The Hysteric’s Erotogenic Body

Before I begin to explain what kind of unsatisfied desire Marian desires, I would first explain what it means by that Marian desires an unsatisfied desire: it is because she experiences jouissance through her desiring, hysterical body. What is the “hysterical body?” Is it a body we are familiar with or a body belonging to the hysteric only? Now, I am going to argue that the hysterical body is rather an erotogenic body than an organic one by following Nasio’s and David-Ménard’s elucidations. Nasio states, “the body of the hysteric is not his real one, but a body of pure sensation” (7). Similarly, according to David-Ménard, the hysteric has no body; instead, he has an omnipresent body. What does it mean? It means that because of the hysteric’s loss of jouissance in his genitals, he on the contrary attains jouissance from all over his body, including his legs, mouth, and even his hair, all of which are the erogenous zones since his

childhood. As we discover, when Marian tries to run away surreptitiously from the engagement party, she suddenly was attacked by an unknowing paralysis; she felt difficult to walk and her flesh felt numbed and compressed (EW 245). She does not get hurt but just cannot walk although one minute ago she can still do that. There is no problem in her organic function, but her legs simply cannot function properly. Why? Since the hysteric suffers, he suffers from the erotogenic body rather than the organic body. According to Nasio, atypical vomiting, enuresis, a crying fit, or a hysterical paralysis of the gait are the ways the hysteric experiences his infantile sexuality. In other words, the hysteric’s sexuality is the infantile sexuality, which remains under the surface of the seemingly “adult body.” In this way, we can say that the hysterical body is not a physical body, but an erotogenic body or a psychoanalytic body. As what Nasio reminds us, the hysteric will hystericize or erotize what is not sexual. That is, the hysteric sexualizes everything but his genitals.

Nasio also claims that the hysterical body, like the harlequin costume, can be disassociated into several parts, the image of which is called the unconscious

representation by him and which is referred to the trauma (15). Likewise, David- Ménard suggests that the omnipresent body of the hysteric is related to the patient’s erogenous zones instead of his organic body. In other words, the hysteric’s symptoms cannot be treated physiologically since the hysterical body is a psychoanalytic body, which is troubled by the surplus of affect dispersed by the ego, rather than an organic body, which can deal only with the organic measures. Comparing Nasio with

David-Ménard, we discover that they both share the idea that the external trauma alone is not the pathogenesis of hysterical symptoms; instead, it is the psychic trace, charged with the overloaded affect and under the tremendous force of repression, which makes the psychoanalytic body stand alone and causes the hysterical symptom to form. Both of them share the viewpoint that the hysteric does not have the organic body. Therefore, while David-Ménard contends that the hysteric has no physical body, Nasio on the other hand proclaims that the hysteric who suffers in the conversion symptom can get the equivalent excess of sexual affect as coming from infantile masturbatory gratification since the hysteric’s sexuality remains infantile (20). Accordingly, the hysteric’s absent body what David-Ménard supposes can also be regarded as an auto-erotic body, which can achieve orgasm through infantile

masturbation as Nasio mentions. However, Nasio gives us the example of a hysteric woman, who “actualizes in her body (as aphonia) the psychic imprint of the other’s body (the mother’s shouting),” to recount that the hysteric’s body can refer to other bodies, including that of the adult seducer and the witness to the scene (22). In this way, the hysteric’s omnipresent body cannot only be elucidated as an erotogenic body by David-Ménard but also be interpreted as a “multiple” body, which is constituted by not only the hysteric’s body but also the bodies other than his, as in Nasio. In brief, no matter the hysteric’s erotogenic body is interpreted as an omnipresent body or a multiple body, the hysterical body is definitely more than simply an organic body. I

will later on take the examples of Marian to clarify the hysteric’s erogenous body more lucidly.

2.1.2. Absent from Lovemaking with Peter

Next, Marian attempts not to attain jouissance when she makes love with Peter in order to dodge experiencing the utmost pleasure, which she regards as a danger and in her thought, which might make her whole being vanish or collapse. By making her subject absent from the reality, she keeps herself “safe” in her fantastic imagination. During the process of making love with Peter, Marian does not totally engage herself in it; instead, she pays her attention to the surrounding furniture and decoration of the bathroom, where she makes love with him. At first, she observes the style of Peter’s shower-curtain, which is not his taste at all since Marian claims in her mind that he bought it in a hurry without taking time to look at it properly because the water kept running over the floor every time when he takes a shower (59). And then, she

imagines a scene where there is a woman who is drowned in the bathtub, chaste as ice only because she is dead (60). Marian continues, “The bathtub as a coffin” (60). Here, we find that Marian does not enjoy the pleasure of making love; on the contrary, she relates the bathtub, where they make love, to a coffin. During the moment of

love-making, she would rather identify with the fantasy woman who is drowned in the bathtub but who would be “chaste” than identify with a real woman who experiences jouissance, the transient death of suffering from excessive sexual satisfaction.

Thinking of that, Marian catches a fleeting vision that she and Peter are killed accidentally in the bathtub (60). Shifting from the scene of fantasizing that they are killed accidentally, Marian recollects the past when she and Peter first meet at a garden party following her graduation, and how her “sexual mood” has been shattered by smashed glass (62).

The sexual intercourse ends up in her fantasy and memory of succession of unfortunate scenes. When Peter asks Marian how she feels, she replies “Marvelous” instead of “Rotten,” for she knows that even she gives him the latter answer, Peter wouldn’t believe her (62). According to Nasio, the hysteric lives the psychical life of fear and the persistent refusal to experience the utmost pleasure, a pleasure which he deems that once he reaches it, the wholeness of his being will be placed under the threat of full collapse and disappearance. Thus, without knowing that experiencing limitless pleasure will not menace the integrity of the entire being, and that there will be and must be only a loss of partial being in everyone because there is no object which can completely fill and match the lack made by castration, the hysteric would rather choose to remain in the state of dissatisfaction, that is, the unfulfilled pleasure. According to Nasio’s elucidation, the hysteric, who unconsciously renders herself as a phallus for a lack, the absence of the genitals, fears that the sexual penetration will tear and burst “her uterus, her vagina, and ultimately, her entire being” (46). To put it more simply, in the hysteric’s fantasy, a man’s penis is unconsciously equal to the “Mother-phallus,” which will arouse her anxiety, anxiety that the “Mother-phallus” can fill the lack of her phallus, lead her to the utmost pleasure, jouissance, and then threaten her “uterus-phallus” and lastly, the wholeness of her being.

In addition, Marian’s subjective position flees to other places in her fantasy to keep her desire unsatisfied so that she can ensure that she is not the cause of the Other’s jouissance. Marian imagines scene after scene without disposing her subject at the right place and time during the process of lovemaking, for she does not want to satisfy both herself and the desire of the Other. Perhaps we can say that it is Marian’s “being” which is making love with Peter, but her “subject” is somewhere in her fantasy playing the role she invents. According to Nasio, the hysteric “is intent on the unconscious desire for the non-realization of the act and hence on the desire to remain

unsatisfied” (8). In other words, Marian thinks of other things when making love with Peter because she can only get the unsatisfied desire by her non-realization of the sexual act. She is absent; the hysterical subject is not present (Soler 270). What Colette Soler means is that the hysteric makes herself indulge in her own thought. Via the process of keeping thinking, she is disposed into her own fantastic world, filling up “the lack with signifiers, with thoughts” (Soler 270). Here, we observe that Marian does not want to be an “object” of the Other’s desire, but the “signifier” of the Other’s lack. In other words, although Peter is penetrating her, he is not really “occupying” her. What he penetrates is just her physical body, whereas what he gets is simply an object but not the phallus, that is, no joissance but only orgasm. Besides, Marian does not utter any erotic words or perform any obscene behaviors as a way to divulge her enjoyment in the process of lovemaking since she does this on purpose to remain “absent” with her thought and make Peter dissatisfied, too. According to Nasio, the hysteric attaches himself to the state of being forever unsatisfied in order to keep away from the danger in front of him, the danger of attaining “the satisfaction of utmost pleasure” which will make him crazy or disappear (5). In other words, the hysteric is not chasing the happiness; rather, he persistently runs after the loss of pleasure. To sum up, even though being unsatisfied is a great pain for Marian, she would rather live in the vicious cycle of endless suffering than in the danger of being torn up via reaching the utmost pleasure from making love with Peter.

Actually, that Marian fantasizes herself as a phallus can also be considered as a way to identify with man, so when Marian makes love with Peter, she virtually regards him rather as a male fighter who attempts to “castrate” her than as her lover who just wants to make love with her. Now, I intend to elaborate why Marian becomes frigid during the process of making love with Peter by employing Freud’s ideas. As Freud avows, after performing the sexual intercourse, it is common for a

woman to embrace a man at the climax of satisfaction, but it is not the behavior for the woman who encounters the first occasion of intercourse. Instead, more frequently, the woman displays frigidity as a reaction to the loss of her virginity, for there is “only disappointment for the woman, who remains cold and unsatisfied, and it usually requires quite a long time and frequent repetition of the sexual act before she too begins to find satisfaction in it” (201). Therefore, Freud indicates that frigidity is women’s psychical impotence as the failure of full impotence is men’s, but what disturbs those frigid women is instead that they cannot untie “the connection between sexual activity and the prohibition” (186). Freud enumerates many explanations of the women’s frigidity established as a neurotic inhibition towards sexual intercourses as follows. One explanation is “the narcissistic injury which proceeds from the

destruction of an organ,” another is that “fulfillment cannot be in accordance with expectations,” and still another is “paradoxical reaction towards the man.” Here, I want to note Freud’s idea of “paradoxical reaction towards the man” to argue that Marian cannot completely enjoy the sexual intercourse with Peter not only because she fears that she might be torn up by the penetration of the penis since she fantasizes herself as a phallus without a lack but because she wishes to be masculine. As Freud suggests, “At first, in his [Ferenczi’s] opinion, copulation took place between two similar individuals, one of which, however, developed into the stronger and forced the weaker one to submit to sexual union. The feelings of bitterness arising from this subjection still persist in the present-day disposition of woman” (205-06). Although Marian does not divulge her real feeling of “Rotten” about the sexual intercourse to Peter, she nevertheless exposes her “masculine protest” indirectly by uttering no erotic words or voices to seduce Peter. Besides, after finishing the sexual act, Peter bit Marian’s shoulder, the signal of which is recognized by Marian for “irresponsible gaiety” since “Peter doesn’t usually bite,” and so Marian “bit his shoulder in return”

(63). Unlike the average couple who bite each other for arousing sexual interest, Marian’s behavior of biting Peter back on the shoulder is more like taking

“vengeance” for her defloration. Or perhaps we can as well regard it as a fair fight between a man and another one, for Marian does not want to “submit to sexual union” and be the weaker one, so she bit back.

2.2. Wishing to Manipulate Others

Secondly, instead of viewing Marian as a social victim under the exploitation and persecution of the patriarchal ideology, I want to argue that Marian’s “abnormally normal” conducts reveal her unconscious wish to manipulate others and the whole situation. Critics have regarded Marian’s “unusual” behaviors as something “abnormally normal” since they believe that her hysterical actions are rebellious counterattack against the patriarchal context, which forces so much feminine mystique and social constraint on the contemporary women. Thus, to some degree, Marian seems to be an undoubted victim as Dora is in the fourfold love relationship in various feminist perspectives since they both are treated as “objects of exchange” either by men or by women. For instance, when Marian and Dora feel oppressed and utilized by their lovers, Peter and Dora’s father respectively, they choose to bear the unjust treatment given by their intimate parties without divulging their real feeling or opinions even though they are actually free or encouraged to offer their requests and complaints. Abandoning the opportunity to tell the Other their real feeling, they play instead the role of victims to manipulate others by degrading their status. Both Marian and Dora might never recognize this idea of wanting to control others since they have placed themselves in the position of being exploited, constantly denying the fact that they are actually the persons who direct everything behind the scenes. I would like to

borrow André Green’s idea that truth does not appear or manifest itself at the moment when everything becomes rational (85). Rather, the real truth in Green’s interpretation is not only “a state of ‘knowledge of not knowing’” (85), but a more subtle, “‘[m]y knowledge is one of knowing not that I know’” (86). What Green expresses here is that actually we do know something, but our knowledge is so limited that we do not know that we know. From the examples given by the novel, we observe that Marian is perplexed by her irrational and unusual behaviors such as her sudden weeping in the restaurant without suitable reasons, followed by her unpredictable running on the street and later by her incomprehensible hiding under Len’s bed. Like the readers, she also asks herself the same question as to why she commits all these ridiculous things. Thus, I am going to dispel these puzzles by adopting Jonathan Lear’s viewpoint in rereading Dora’s case.

2.2.1. Marian’s Idiosyncratic Ways to Deal with Her Anxiety

Now, we are going to discuss how Marian’s anxieties are aroused and how she handles her overwhelming anxieties. At the beginning of the novel, we observe that Marian is an extremely self-repressed person who conceals her emotions cautiously and utters words with contemplation since she usually tries her best to accord with other people’s expectations and needs, no matter at work, or with her friends, or even in her love life. Let’s take one of the instances of her specific way about getting along with the landlady. Although the landlady does not plainly express her discomfort about Ainsley’s carelessness and sloppiness, Marian herself, however, conjectures that the landlady often keeps her watch in secret so that Marian sometimes glosses over Ainsley’s mistakes, fearing that the landlady might be irritated by some trivialities done by Ainsley:

violation of her shrine. She leaves deodorants and cleansers and brushes and sponges in conspicuous places, which has no effect on Ainsley but makes me feel uneasy. Sometimes I go downstairs after Ainsley has taken a bath and clean out the tub. (56)

Marian cares so much about other people’s opinions and judgment on her that she feels “uneasy” even when her roommate, Ainsley, has done something inappropriate that she believes that others might misunderstand what she was done. Besides, Marian also fears that her colleagues might detect her real thought, so she usually suffers from the overwhelming anxiety. For example, when her colleague, Lucy, asks Marian about whether going out with Peter or not, Marian replies with a short answer without offering volunteering information since her colleagues’ wistful curiosity makes her nervous (29). Another example is that attempting to exhort Ainsley to abandon the thought of rearing a child on her own without the presence of a father, Marian nonetheless is accused by Ainsley as a prude, the term which makes Marian secretly hurt since she thought that she “was being more understanding than most” (42). However, she does not let Ainsley know that she is hurt by her words; rather, she goes to bed without saying anything, but she feels “unsettled” (43). Instead of letting others, such as the landlady, her colleagues, her roommate, and so on, know what she

considers, Marian represses her feeling and thoughts again and again. As a result, she acts “abnormally” the first time after she represses her feeling and redraws her words again in the conversation with Peter. Eating frozen peas and smoked meat for dinner, Peter blames Marian for never cooking anything (63). His words seriously hurt Marian, but she does not act out; instead, she changes the topic to cover her real emotions:

I was hurt: I considered this unfair. I like to cook, but I had been