Transitional justice and indigenous land rights: the experience of indigenous peoples' struggle in Taiwan

全文

(2) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. 1. Transitional Justice and Indigenous People Transitional justice refers to a range of approaches, includes criminal prosecution, truth commission, reparation program, gender justice, security system reform, and memorialization effort, used to address past human rights violations ( Teitel 2000, ICTJ 2008). The framework of it was originally devised to facilitate reconciliation in countries undergoing transitions from authoritarianism to democracy. It is however increasingly used to respond to certain types of human rights violations against indigenous peoples (Jung 2009). The democratic transition in Taiwan appeared in 1980s, during which the KMT (KuoMingTang, the nationalist political party) government abolished the Martial Law, ended the prohibition against organizing of political parties, followed by the election of the congressional representatives in 1992 and the first general election of the president in 1996. The victory of DPP (Democratic Progress Party), the opposition party in the presidential election in 2000 was the landmarks in the transition from authoritarianism to the two-party democratic regime. Along with this transition, cultural pluralism emerged in Taiwan society. Meanwhile, the discourse of Taiwan as a multi-ethnic state rose to encounter the discourse of one Chinese nation. This is especially significant for the Austronesian language speaking people in Taiwan, because, as the “indigenous”, their “position” is changed from the peripheral “minority” in the Chinese Nation, to the core of the formation of multi-ethnic state. Engaging the historical moment of democratic transition, Taiwan indigenous peoples strived to address the injustice happened and continued after the colonial contact. The main objectives of indigenous movement in Taiwan include cultural self-representation, political participation, and the recognition of indigenous land rights. While the first two objectives gradually appeared to be achieved, a huge gap between the recognition of indigenous land rights and its implementation still exist. After introducing the indigenous and their lands in Taiwan, this paper will: 1) review the indigenous movement and its objectives, 2) examine the concept of indigenous traditional territory and how it was appropriated in the governmental discourse, 3) take the beech event happened in Tayal traditional territory as an example to illustrate the government’s mistranslation of indigenous knowledge, and show the importance of the openness to indigenous peoples’ knowledge to the lands as the premise of a real reconciliation and the achievement of transitional justice.. 2.

(3) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. 2. Indigenous Peoples and Their Lands in Taiwan Peoples speaking Austronesian languages lived independently and autonomously in Taiwan for thousands of years, until Dutch and Spanish, the earliest foreign forces, landed and built their colonies in the western plain area during the 17th century (Kang 1999)2.Both colonies started local fur business to trade with Japan, and engaged in trade with South East Asia and China. In 1662, the Jieng, a rebel army claiming itself as the successor of the Ming Dynasty defeated the Dutch and took over west plain area of Taiwan as a base to fight against the Ching Dynasty in China. After the rebel army surrendered in 1683, the Ching Dynasty controlled the western plain area of Taiwan for 212 years. In the late years of its control over the Western plain area of Taiwan, the Ching Dynasty tried to invade the lands in the mountain area but was repelled in highland battles. During its governance, the Ching Dynasty named the Austronesian language speaking peoples as “barbarian” and their living space, where the dynasty unable to exert its control, “barbarian land”. In 1894, the expanding Japanese Empire won the battle against the Chinese Navy over the East China Sea and China ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895. Even though the Ching Dynasty was never able to govern the central mountain area even for one day, under the Japanese imperial logic, this area and its peoples were ceded as imperial property. The Japanese General Government in Taiwan followed the terminology of “barbarian” and “barbarian land”. In 1945, when the R.O.C. (Republic of China) took over the governance of Taiwan after Japan surrendered to the Allies, the new government changed the official appellation of Austronesian languages speaking peoples from “barbarian” to “mountain compatriot”. In 1994, the appellation was changed to “indigenous people” during the National Assembly held for the revision of the Constitution. Through immigration the Han-Chinese people became the dominant population in Taiwan after a series of immigration waves. Even though there is no precise statistics of the Austronesian languages speaking population of every group under different governments in time, following data from diverse literatures illustrate a picture of the 2. The Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company) landed on the southern west coast in 1624 and built the Kasteel Zeelandia there. In 1626, the Spanish landed on the northern west coast and built the San Domingo Castle. The Dutch expanded their force to the north, defeated Spanish in 1642, and became the only western colonizer in Taiwan until 1662. Even though there were some contacts between the Dutch and the “barbarians” in eastern Taiwan under the Dutch’s exploration, the eastern Taiwan kept being a frontier and this situation continued in the Ching Dynasty. 3.

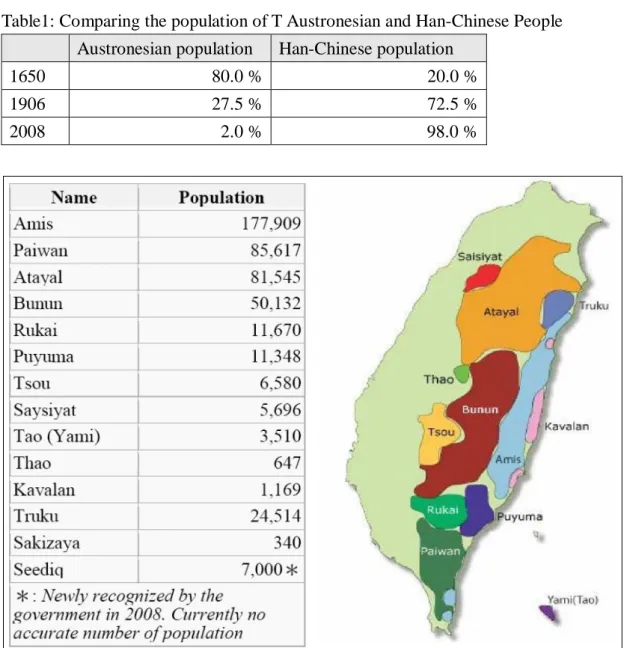

(4) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. demographic transition. According to the population estimation made by the Dutch colonial government in 1650, the population of Austronesian languages speaking peoples in the Taiwan plain area was about 60,000 (not including those in mountain area that the Dutch colonial government could not reach), and the population of Han-Chinese settlers was about 15,000 (Nakamura 2001). Following immigration in the Jieng and Ching Dynasty, the population of Han-Chinese increased to 2,900,000, and the population of “barbarian” was 110,000, according to Japanese colonial government’s census in 1905 (Chang 1979). By December 2008, the population of “indigenous people” in Taiwan was about 490,000, which is only about 2% of the total population in Taiwan3. Table1: Comparing the population of T Austronesian and Han-Chinese People Austronesian population. Han-Chinese population. 1650. 80.0 %. 20.0 %. 1906. 27.5 %. 72.5 %. 2008. 2.0 %. 98.0 %. Figure 1: The distribution of indigenous peoples and their population (Source: Kuan 2009) 3. Source of Information: Council of Indigenous Peoples (http://www.apc.gov.tw/main/) 4.

(5) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. As mentioned above, the plains in eastern Taiwan and central mountains, which are home to indigenous tribes, were not governed by foreign governments until 1895, which was the beginning of the Japanese colonial era. The Japanese colonial government implemented a land survey in 1898, and then in 1910 initiated a five-year military project to conquer indigenous peoples in Taiwan. The mountainous areas previously “owned” by different indigenous communities were then nationalized. In 1925, the National Forestry Survey Project confined indigenes to Reserved Lands, which were small and fragmentary land parcels in the mountains. At the same time, many communities were forced to migrate to low mountainous areas, and change from traditional hunting and gathering to agricultural production. In 1945, the KMT government replaced the Japanese colonial government in Taiwan and retained the Reserved Lands Policy. 3. The Indigenous Movement The Austronesian language speaking peoples in Taiwan has persisted in resisting colonial domination through different historical periods. Twenty years after the battles against colonial government’s “Five Year Militarily Pacification” during 1910s, a military “rebellion” happened in “Wu She” ( “Fog Village” in Chinese) of the Sediq people in central Taiwan in 1930. It led to about one thousand deaths and made the colonial government aware that, after all these year, the “barbarian” has not really submitted. After WW II, the “barbarian” intellectuals who had received colonial education began to express their wish for self-determination in the colonizer’s language. In 1947, Watan Losin, an Tayal physician who was the first “barbarian” person to receive western medical training during the colonial era, made a petition in the Provincial Legislative Assembly. With more than one hundred signatures from previous residents of the Topaq settlement who were relocated by the colonial government for their resistance to the march of colonial army, the petition stated (Wu 2007:7): “Since we have been liberated from colonialism, please return the land taken away by the colonizers to us. Otherwise, we can’t really feel the happiness of liberation. We urge to go back to the homeland for we have never stopped missing it for one day. ” When the government rejected their petition, the villagers’ anger almost caused a riot. The next year, villagers rejected the goods and materials provided in consolation by 5.

(6) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. the government (Wu 2005). In 1949, a group of Tayal high school students, who came from different villages in the northern Taiwan mountain area and studied in Taipei, organized the “Alliance of Formosa Youth Self-Liberating Struggle”. The alliance made a statement of “self-awareness”, “self-governance” and “self-defense”. The KMT government soon repressed these political expressions. Losin Watan and five other “mountain” intellectuals were arrested and executed in 1952. The Tayal youths were arrested and sent into jail. The terms of their imprisonment ranged from two to ten years. Under the new coercion, there was no political opposition recorded until early 1980s, even as Taiwan engaged in democratic reform. Demonstration and protests in the urban areas organized by different social movements rose to challenge the KMT government and its governance in 1980s, and the movement striving for indigenous people’s rights was one of them. As a result of the widening gap in economic incomes between mountain and plain area, indigenous labor gradually moved to urban areas in 1970s. They encountered diverse forms of discrimination because of their “Mountain Compatriot” identity, as well as their disadvantaged social-economic status. The indigenous movement in 1980s began with accusation of racial discrimination, inhuman exploitation of indigenous labor, and the human trafficking that enslaved indigenous adolescents in the sex industry. The core organizers were usually non-indigenous human rights activists, opposed political movement practitioners, indigenous clergy and college students in the urban area. For example, in 1985, indigenous protesters showed up in the inauguration of the renovated Wu-Fong temple, and accused the KMT government of continually adopting the fabricated Wu-Fong myth in textbooks of elementary schools to stigmatize indigenous people after it took over the colonial governance. In 1986, protesters held a parade in Taipei. In 1987, indigenous protesters went to the bronze statue in front of Chia-Yi train station, and they pulled down the statue with chain saws, ropes and trucks. The government finally deleted this story from textbooks later in the same year. In 1986, academics, writers and social workers issued a petition asking the government to give an special amnesty for Yin-Shen Tan, a Tso indigenous young man who dropped out from college, and went to work in a laundry shop, where he accidentally killed his employer after a long period overtime work, discrimination, and inability to quit his job because his employer illegally detained his ID card. This petition got much support but it failed to change Tan’s destiny of being executed. In 1987, a parade protesting the human trafficking marched to Hwa-Shi Street, a famous red-light district in Taipei, and called for urgent action against human right violation. According to informal statistics of an NGO, 40% of the sexual workers were 6.

(7) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. indigenous people then (Liao 1989). This number is much higher than the 2% indigenous population of the total population in Taiwan. Many of them were adolescents and victims of the human trafficking. The movement gradually turned to seek an institutional solution for the problems in late 1980s. Protests rose to strive for land rights and political autonomy. A series of “Return My Land” Protests were held in 1988, 1989, and 1993. During this five year period, the discourse of “Return My Land” moved from asking for more Reserved Land area and property rights to the claiming of indigenous sovereignty. A significant move during 1990s is that congress passed the official appellation of “indigenous people” in the Constitution in 1994. Furthermore, in 1997, the central government established the Council for Indigenous Peoples, a response to indigenous movement’s long-term request to promote the highest office in charge of indigenous affairs from previous local, provincial level to central, national level in the government. However, indigenous land rights were rarely discussed. The KMT’s policy toward indigenous peoples was largely devoid of recognition of indigenous rights; thus, discussing what “traditional territory” means is very difficult. However, in the 2000 presidential campaign, presidential candidate Mr. Chen Shui-Bian (president 2000~2008) announced a “New Partnership Policy” as his major indigenous policy. This policy, which committed the government to recognizing indigenous claims to traditional territories, was codified in legislation when Chen assumed the presidency. 4. The Indigenous Traditional Territory In Taiwan, the term “indigenous traditional territory” was originally used as a concept to claim indigenous peoples’ sovereignty in the context of the indigenous movement. However, when the government began to implement the indigenous traditional territory survey, it was changed to the concept of traditionally used land around individual settlements. Indigenous ecological knowledge is romanticized as the knowledge of the past in which indigenous people are supposed to live in harmony with nature. Ironically, this representation of indigenous people and their traditional territory persists from colonial to post-modern Taiwan. Since late 1990s, the indigenous movement in Taiwan turned to local and place-based issues. For instance, in 1996, the Rukai people in Hau-Cha organized and successfully resisted a governmental project that planned to build a reservoir downstream on the 7.

(8) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. Ai-Liao River that would require moving a Rukai village and submerge their heritage permanently. It is an example demonstrating that the focus of the indigenous movement has shifted from the reform of central government regime to peoples and the places in which they live(Kuan 2008; Lin, Icyeh et al. 2008). Along with this shift, “Bu-Luo” has become a popular term and appears in many discussions of issues related to indigenous peoples. “Bu-Luo”, initially a Mandarin term used by anthropologists, refers to “tribal settlement” in non-western and underdeveloped tribal societies. However, as the indigenous movement shifted its concerns, “Bu-Luo-ism”— regardless of its definition of tribalism in anthropology— was utilized by indigenous activists to highlight a new movement strategy that emphasizes grass-roots power and seeks local knowledge. In fact, the term “Bu-Luo” has become generally synonymous with the indigenous communities, even though the way in which a “community” is organized varies with different peoples and different regions (Kuan 2008; Lin, Icyeh et al. 2008). It also was adopted by the government in its indigenous policy. For example, the Council of Indigenous Peoples began its “Project for Indigenous Bu-Luo Sustainable Development” in 2002, under which a sub-project of “Typical Bu-Luo” provides financial support to selected indigenous communities on purpose to help them to develop their ecological and cultural resources. In the context of the indigenous movement in Taiwan, the term “traditional territory” was used as in sovereignty claims against the state. Dr. Ming-Hui Wang, for instance, a member of the Tsou people, was the first to map his own people’s traditional territory, which he used to write his master’s thesis (Wang 1989). With Dr. Wang’s involvement, the Tsou people created their own tribal council, the first among all peoples in Taiwan. Furthermore, Masa Towhuy, an Tayal elder who has devoted over 30 years to fighting for Tayal traditional territory, utilized official maps from different colonial powers to expose how much Tayal land had been stolen. He also utilized different maps to document the oral histories and historical evidences of Tayal territory, including those long since abandoned. In his persistent pursuit to identify Tayal traditional territory, he recorded rich oral histories from different villages. Additionally, he was also involved in a lawsuit and initiated a social movement to fight for traditional indigenous territories (Lin and Hsiao 2002; Lin, Icyeh et al. 2008). In the third “Return my land” Protest in 1993, indigenous people declared that “Indigenous people have the right of self-determination for our future over our territory” and requests the state to “sign the land treaty with indigenous people in a 8.

(9) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. mutually equal relation”. No matter which territory of which indigenous people, the traditional territory of Tsou people, or the traditional territory of Tayal people, they all clearly refer to the concept of sovereignty. The concept of sovereignty in the term “traditional territory” however was displaced and the survey of indigenous traditional territory was defined as a work to map out all the boundaries between individual settlements only when and where the state seems to willing to recognize it. In the 1999 presidential campaign, presidential candidate of the DDP, Mr. Chen Shui-Bian (president from 2000 to 2008) signed a “New Partnership Treaty”4 with indigenous tribal representatives, and adopted the fulfillment of this treaty as his major indigenous policy. This treaty, which committed the government to recognizing indigenous claims to traditional territories, was reaffirmed and partly codified in legislation after Chen assumed the presidency5. It marks a major difference between DPP government and KMT government’s indigenous policy, which was largely devoid of recognition of indigenous land rights (Kuan 2008; Lin, Icyeh et al. 2008). Aiming to fulfill its political commitment, the government launched a nationwide Indigenous Traditional Territory Survey (ITTS) in 2002. In this survey, community maps, community participation and computer-based GIS were integrated to identify the territories and traditional knowledge of indigenous communities. The Council of Indigenous Peoples (CIP) in the central government, which is the financial sponsor of this project, announced its goal of mapping all indigenous communities (more than 600 communities located in 55 indigenous Villages) over a three-year period. Through open tender, the CIP contracted a research team of mainly geographers from different universities to conduct surveys starting in 2002. In the first year of the survey, 30 indigenous communities were chosen as exemplary locations for the survey. In the second year, a larger team was organized and the survey area was extended to all 55 indigenous Villages. In the survey’s third year, a similar procedure was executed to 4. The Treaty includes seven articles. They promise that the government will: 1). recognize indigenous peoples’ inherent sovereignty; 2). promote indigenous self-governance; 3) sign a land treaty with indigenous peoples; 4) recognize the traditional names of indigenous settlements, mountains and rivers; the government will; 5) recognize indigenous peoples and settlements and the lands of their traditional territories; 6) recognize indigenous people’s use of traditional natural resources, and promote indigenous peoples’ autonomous development; 7) make sure each of the indigenous peoples has their representatives in congress. 5 The reaffirmation was made in 2002. In 2005, the congress passed the Indigenous Basic Law that codified the recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights over their traditional territories addressed in Article 5 of the New Partnership Treaty. On the other hand, the legal procedure for indigenous peoples to claim their traditional territories is still left unclear and awaiting to be decided in the passage of another law. 9.

(10) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. complete the survey (Chang 2004; Kuan 2008; Lin, Icyeh et al. 2008). By the end of the third year, approximately 464 indigenous communities belonging to 12 different tribes located in 55 Villages were mapped. About 3700 native place names in indigenous languages (translated into Mandarin) were recorded along with folk stories, myths and oral tales attached. Some communities have well-defined territory boundaries or boundaries of hunting/cultivating territories (Chang 2004). These maps resulted from the CIP’s financial investment as well as the mapping team’s devoted efforts. However, at the same time, this project illustrates that in the state’s concept the priority to define “territory’ is to delineate its geographical boundary and make it legibly incorporated into the system of management. The imagination of an undifferentiated national “homeland” which provides unified interest to every citizen in the state is problematic. People in the downstream plain area may have their urgent needs for water supply, but why it is always upstream indigenous communities that have to be sacrificed to keep the development in the plain area sustainable? It is a political issue rather than a technical one. However, by provoking the pubic interest and mainstream opinion, the state delineated an undifferentiated national space, and thus the issue of justice was reduced to the issue of “what is the most efficient method to manage the resource”. The imaged “wilderness” is continually incorporated into a national discourse of “natural” resource management, and subjected to the administrative spatial project. Furthermore, assigning traditional ecological knowledge to sustain the conservation works in indigenous communities, the “Homeland Recovery Project” assumes indigenous people’s traditional ecological knowledge as an instrument to protect nature. Such assumption that delineates indigenous people as “born guardian” of “nature” not only brought indigenous peoples onto the stage of eco-politics, but also “narrowly circumscribed the terms in which their appearance could be understood” (Braun 2002). Under such circumscription, “indigeneity” is constructed in the image of timeless ecological balance and ethical perfection. The transformation from “threat to nature” to “guardian of nature” continues the stereotyping of the ecological Other, rather than recognizes who indigenous people really are. Becoming “forest steward” for “eco-tourism” proposed by “Homeland Recovery Project” seems to be an ingenious design for indigenous people that can diminish conflicts between their economic and cultural demands and the regional role mountainous areas assigned by the state. However, it will also lead to a risk that indigenous communities will again be confined to a particular time and space within the order imposed by the state. 10.

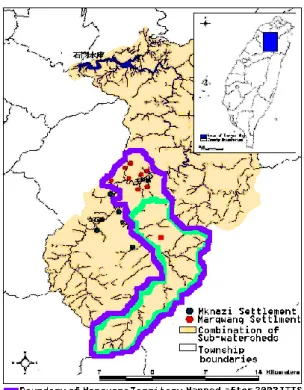

(11) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. The state’s concept of “territory” and assumption of instrumentalized “traditional ecological knowledge” led to conflicts the state did not expect when it attempted to make the first announcement of indigenous traditional territory in the Marqwang area, which I will discuss in following sections. 5. The beech event—the state’s logic of “fitting everything into its place” The “Beech Event” that happened in Smngus in 2006 led the government to announce existence of traditional territory. Such an announcement was the first attempt made after the five-year Indigenous Traditional Territory Survey. Form the governmental perspective, it is a progressive attempt to integrate indigenous ecological knowledge into the resource management regime. The announcement however caused further conflicts within the indigenous community and also between the community and the government. These conflicts challenge the state’s understanding of indigenous knowledge, and also show the state’s logic of fitting everything into its place for purpose of resource management. 5-1. Smangus and Marqwang Because the “Beech Event” began with a lawsuit caused by three Smangus young men’s violation of the Forest Law, I will spend some paragraphs to introduce the relation between Smangus and Marqwang group, and also the context of this event. In the Smangus is one of the thirteen existing settlements that belong to the identity group of Marqwang. According to the oral histories of many families in Marqwang group recording their migration paths, Smangus is the first settlement their ancestors built when they came into the Valley of Takazin River. Some relatives of their ancestors who came into this area at almost the same time built another settlement named Cinsibu on the other side of the Takazin River. Years later, when their relatives in Cinsibu extended to the Sakayazin River Valley, and built series of settlements that formed the knazi group, the ancestors of Marqwang moved forward to the another river valley, built settlements in the valley and formed the Marqwang group. 5-2. Smangus traditional territory in the context of Indigenous Traditional Territory Survey In the 2002 ITTS, Smangus was the only settlement selected as an exemplary site to conduct the mapping work in the Marqwang group. A map of Smangus traditional 11.

(12) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. territory was made and published in the annual report of ITTS. Soon after that, scholars and Marqwang settlement members drafted a Five-Year Conservation Project. Based on the Smangus traditional territory mapped out in the 2002 ITTS, Smangus settlement members committed to cease all hunting, fishing and logging activities in a certain area. This project covering “Smangus traditional territory” subsequently raised tensions between Smangus and other settlements of Marqwang group. Some members in these settlements were expelled while trying to hunt in the restricted area. Critism of Smangus and questioning of the traditional territory they claimed spread among the settlements quickly.. Figure 2: Sangus traditional territory in 2002 ITTS (Source of map: Kuan 2009) 5-3. The announcement of traditional territory In 2006, following a settlement meeting, three young men in Smangus settlement went to bring back a wind-fallen beech tree lying on the road to their village. Soon afterwards they were interrogated by the forest police and accused of stealing state property according to the Forest Law. Since then, these three young men have been coming and going between the village and the court in the city. Their story is not unique. This is just one of many cases that have happened since indigenous people have lost their rights over the land under state power after the colonial contact. However, what happened afterward was really beyond many people’s expectation. Unlike most of the cases in which indigenous people will eventually pay the penalty 12.

(13) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. to get their life back to normal, these three young men refused to admit their guilt in stealing state property, with strong support from whole Smangus settlement, Even though the judge intended to settle the case on the lenient side at the first trial, the three young men insisted in principle that it is the state stole our land. When the elders from neighboring settlements (both Marqwang and knazi), human rights groups, indigenous groups, and scholars jointly formed an alliance to defend these three young men and Smangus settlement’s assertion, the “Beech Event” gave rise to the social concerns on the issue of indigenous land rights under the current legal system. After series of protests and petitions from the alliance, the Executive Yuan in the central government eventually got involved to facilitate negotiations between the alliance and government departments in seeking common ground to settle the problem. During the negotiations, the CIP proposed to officially announce the traditional territory of Smangus, so that the three young men can be proven innocent according to indigenous rights over the traditional territory recognized in the Indigenous Basic Law passed in 2005. The Indigenous Basic Law that was passed in the congress in 2005 recognizes indigenous people’s rights over their traditional territory. It also requires the government to complete the legislation work for related acts, such as the Indigenous Land Act that is suppose to detail the legal procedure to delineate the area of indigenous traditional territory and the procedure to claim the land rights. However, none of the related acts assigned in the Indigenous Basic Law is legislated so far. CIP’s proposal meant to prove that it is indeed a traditional territory of Smangus where these three young men exercised their right to pick up the fallen timber. Some members of the alliance however argued that such right has been recognized by the Basic Law, and can not be repudiated because the government fails to meet the deadline for the legislative work on the Indigenous Land Act. What CIP intended to do will affirm that the right can only exist after the government can delineate the exact area of traditional territory; therefore disproving the assertion that the right already existed since the legislation of Indigenous Basic Law. Whether or not this proposal would actually prove these three young men’s plea of innocence on the basis indigenous people’s land rights over traditional territory have been recognized by the Indigenous Basic Law, it was soon noticed that the location of the wind-fallen beech was actually not inside the Smangus traditional territory mapped out in ITTS 2002 survey. In subsequent negotiations, the alliance began to argue that even though the location is not inside the Smangus Traditional Territory according to the ITTS 2002 survey, it is still inside the traditional territory of 13.

(14) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. Marqwang group. Further, a member of Marqwang community has a right to collect wood in this area according to traditional customs. This argument was discussed and confirmed by several meetings between the elders from different settlements in Marqwang group. In these meetings, the representatives from Smangus also made efforts to reconcile the conflicts caused by the Five-Year Conservation Project. They explained to the representatives from other Marqwang settlements that Smangus never meant to exclusively control the shared hunting areas. The expulsion of hunting was a misunderstanding caused by their over enthusiasm in taking care of the fields. After these meetings, the elders from Marqwang group attended a negotiation in July 2007 to testify Smangus’ rights in the traditional territory of Marqwang. The negotiation in July 2007 was a turning point for the government to rectify its decision. Even though the Forest Bureau tended to reject the proposal announcing Marqwang traditional territory, as it means the “opening” of much wider state-owned property to indigenous people than they can tolerate, the proposal was eventually made as resolution in the meeting. After all, the Presidential Election was coming next year and it was a chance for the ruling party to show its determination in realizing the New Partnership Policy.. Figure 3: Marqwang traditional territory to be announced after the negotiation in July 2007 (Source of map: Kuan 2009). 14.

(15) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. An event in the final stage of preparations to make the announcement however changed its decision again. In August 2007, the CIP held a hearing in the assembly hall of Jien-Shi Village Government. Elders from the seven villages in the Village were invited to attend this hearing. In its schedule, the CIP expected this hearing to result in a final confirmation of Marqwang Traditional Territory. Officers in the council had been planning a press conference for the Chair of Executive Yuan to announce the traditional territory of Marqwang. The meeting however broke out with fierce objection against the announcement of Marqwang traditional territory from a group of residents in Teyakang, a Mknazi settlement. One Teyakang resident questioned the elders of Smangus loudly and impolitely: “This morning, before I came to this meeting, my father told me that his hunting skill was taught by your grandfather in Smangus. How dare are you say that this area belongs to the Marqwang group alone”. Continued objections from Teyakang residents made the meeting chaotic. Both of the hosts, the Chair of the CIP and the Village governor failed to even control the meeting. With astonishment and embarrassment, the Chair of the CIP simply declared the meeting over. After the meeting, one officer in CIP could not help but complain to one of the scholars attending this meeting, one who is also an defender of the argument that the government should announce the traditional territory of Marqwang instead of the territory of Smangus, “Are you sure the boundary of Marqwang you guys mapped out is correct?” 5-4. The Mistranslation of Indigenous Knowledge Is the boundary mapped out correct? Which version is correct? The answer can be found in the translation of spatial knowledge from that of indigenous conceptions that are multiple and situational, to the fixed cartographies of the modern state. In Tayal language, different terms refer to various social-spatial relations that I will further explicate them in next chapter. But here I will introduce them to explain why the Tayal spatial knowledge was mistranslated. gaga, for instance, refers to a set of customs, rules and rituals driven from utux (the spirit) belief. Qalang refers to the residence of households, similar to the definition for “settlement” in English. Qyunan may be the Tayal term closest to the term “territory” in English. A group like Marqwang normally shares a Qyunan, which typically occupies a watershed for purposes of hunting, farming and fishing. Although easily deemed as “territory”, Qyunan somewhat differs from the “territory” the state conceived. 15.

(16) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. Smangus, for example, is a qalang sharing one qyunan with all other qalang in the Marqwang group. Inside the Qyunan of Marqwang group, each Qalang acknowledges its responsibility to malahang which, in Tayal language, refers to “taking care of” their Qyunan. However, In Tayal knowledge, the Qyunan base on watershed forms a mechanism to bring people to sharing relationships not as boundary to exclude them from it. Although even in pre-modern western societies “property” was closely linked with “propriety”, and therefore responsibility. The concept of malahang Qyunan in Tayal knowledge is different from the exclusive ownership over property that emerged in the modernization. It is a key point to understand why the Five-Year Conservation Project caused misunderstandings between Smangus and other settlements in the Marqwang village. At the 2002 ITTS, as the only settlement selected in the Marqwang group, Smangus members together with the mapping team mapped the area in the qyunan they have been hunting, gathering and taking care of. However, this area was interpreted as a “territory” that belongs to Smangus alone. This misinterpretation was further implemented in the Five-Year Conservation Project that gave authority to Smangus to decide the prohibition of hunting, gathering and other activities in this area. It is therefore also reasonable for some of the knazi members to get upset when CIP attempted to officially announce the Marqwang Traditional “Territory”, which will be followed by a new regulation allowing Marqwang people to gather certain woods in this area. The gathering activities have been stringently forbidden by the Forestry Bureau since Taiwan gained independence from Japan in 1945.The announcement of indigenous traditional territory will provide some access, although extremely limited, for the members of Marqwang to utilize the forest. However, for the members of knazi, designating this area as the traditional “territory” of Marqwang implies that knazi are officially excluded from legal access to this area. Fundamentally, it is not a problem of whether the boundary has been delineated correctly or which version of boundary is more correct. It is that, even though the state intends to incorporate indigenous knowledge into watershed management, the survey deemed the Tayal Qyunan and “territory” as the same entity without understanding the meaning of Tayal spatial knowledge. 6. Conclusion A total, exclusive authority over the territory is the characteristic of modern state that developed in long history of modernization. In the context of indigenous movement, the term “traditional territory” is illustrated as sovereignty claims against the state, 16.

(17) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. rather than as a well-defined geographical boundary of an individual community. However, on its purpose to fulfill the political promise of “New Partnership Policy”, the government’s intention to map out the concrete boundaries for every individual indigenous communities override the meaning of participatory in the mapping process. Map became an important exhibition to show the achievement in its official career. Map is a representation of spatial relations it also reflects the social relations within which the mapping is processed. The experience of Marqwang case reveals the limits of ITTS, as well as the lack of access for indigenous communities to discourse their own spatial knowledge. Methodologically, even though in the name of “indigenous community mapping”, the participation of indigenous community in ITTS mostly refers to the participation of human labors. A framework for the different knowledge to equally participate and dialogue in it is not yet established. Epistemologically, the Marqwang case shows the inadequacy of appropriating indigenous spatial knowledge into a modern cartographical representation without considering the context this knowledge is generated. It reminds that further involvement of ethno-historical and linguistic methods is in need. It also reminds a real reconciliation can only be achieved in the premise of the openness to indigenous peoples’ knowledge to the lands.. 17.

(18) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. Reference Braun, B. (2002). The Intemperate Rainforest: Nature, Culture, and Power on Canada's West Coast. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press. Chang, C.-Y. e. a. (2004). Report of Indigenous Traditional Territory Survey. Taipei, Council of Indigenous Affair. Chang, S.-J. and M.-L. Shu (1979). "Analyzing the Effectivity of the Check Dams in the Watershed of Shimen Reservoir." Journal of Geographical Science(10): 73-96. ICTJ (International Center for Transitional Justice) .2008. What is Transitional Justice? .International Center for Transitional Justice (http://www.ictj.org/en/tj/) Jung, Courtney (2009).Transitional Justice for Indigenous People in a Non-transitional Society. International Center for Transitional Justice (http://www.ictj.org/en/research/projects/research6/thematic-studies/3197.html) Kuan, D.-W. (2008). Lost in Translation: A Case Study of Community Mapping and Indigenous Traditional Territory Survey in Taiwan. The 19th Annual University of Hawaii at Mānoa School of Pacific & Asian Studies Graduate Student Conference. Honolulu, Hawaii. Kuan, D.-W. (2009).A River Runs Through it: Story of Resource Management, Place Identity and Indigenous Ecological Knowledge in Marqwang. PhD dissertation. Department of Geography, University of Hawaii at Manoa Liao, B.-Y. (1989). Tsai Hing Shan Zho Nien Ji Nien Jwan Ji (A Special Issue in the Third Anniversary of Rainbow Organization). Taipei, TzaiHong. Lin, Y. R. and H.-C. Hsiao (2002). Contesting Aboriginal Community Mapping: A Critical View from Local Aboriginal Participation in the Natural Resources Management of Taiwan. . Society for Conservation Biology 16th Annual Meeting, Cantebury, UK. Lin, Y.-R., L. Icyeh, et al. (2008). Indigenous Language Informed Participatory Policy in Taiwan: A Socio-Political Perspective. Documenting and Revitalizing Austronesian Languages. D. V. Rau and M. Florey. Honolulu, University of Hawai'i Press: 143-161. 18.

(19) Bilateral Conference (Taiwan and Austria) for Justice and Injustice Problems in Transitional Societies. Nakamura, T. (2001). He lan Shi Dai De Tai Wan Fan She Hu Ko Biao (The Households Registration of Barbarian Settlements During Dutch Colonial Era). He lan Shi Dai Tai Wan Shi Yien Jio (Study of Taiwan History During The Dutch Colonial Era). Taipei, Tao Shian Press. 2: 1-38. Teitel ,Ruti G. (2000). Transitional Justice. New York: Oxford University Press Wang, M.-H. (1989). The Spatial Organization of Traditional Tsao Society in A-Li Mountain. Department of Geography. Taipei, National Taiwan Normal University. Wu, R. R. (2005). Tai Wan Yuen Zhu Ming Ji Chi Ju Yi De Yi She Shin Tai Ken Yuen: The Ideological Origin of Taiwan Indigenous People's Self-Autonomy. State and Indigenous People: The Historical Studies of Ethnic Groups in Asian Academia Sinica.. Taipei,. Wu, R. R. (2007). Tai Wan Kau Shan Tzu Sha Ren Shi Jien (The Murdered Taiwan Indigenous People). Conference in Memorial of The 228 Event Academia Sinica, Taipei: 1-37.. 19.

(20)

數據

相關文件

Article 40 and Article 41 of “the Regulation on Permission and Administration of the Employment of Foreign Workers” required that employers shall assign supervisors and

Wang, Solving pseudomonotone variational inequalities and pseudocon- vex optimization problems using the projection neural network, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 17

Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive

Define instead the imaginary.. potential, magnetic field, lattice…) Dirac-BdG Hamiltonian:. with small, and matrix

Microphone and 600 ohm line conduits shall be mechanically and electrically connected to receptacle boxes and electrically grounded to the audio system ground point.. Lines in

The second question in this paper is raised from the first question – the relationship between constructing Fo Guang Pure Land and the perspective of management beginning

Through the classification and analysis of Zhu’s short treatise, this study seeks to understand the direction of his Pure Land teaching and theory, especially Pure Land,

Experiment a little with the Hello program. It will say that it has no clue what you mean by ouch. The exact wording of the error message is dependent on the compiler, but it might