台灣華語聲調習得 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Tone Acquisition in Taiwan Mandarin. By. 立. 政 治 大 Han-chieh Yang. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Institute of Linguistics in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. June 2013.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. Copyright © 2013 Han-chieh Yang All Rights Reserved. iii. v.

(4) 致謝詞 我曾經試著想要算算看這本論文大概花了多少小時才完成,但是發現這個數字龐 大到無法計算,光是每個禮拜舟車勞頓收集小朋友語料長達一年多,就大概超過 100 小時,加上之後譯寫錄音檔案和整理也大概花了 100 多個小時,研讀文獻少 說 80 小時,分析和寫作的時間大概也有 200 小時,整本論文要完整呈現必須要 花將近 500 小時呢!真的是一個非常大的工程!殊不知我第一次跟老師 meeting 時,老師才花 10 分鐘就把我腦中兩個很籠統的方向整理出一個完整的架構!讓 我至今還是敬佩不已。 三年前剛進來語言所時,我就是跟著萬依萍老師做助理。從前我是一個行動力頗 弱的人,做事慢、也容易猶豫不決,但是因為老師是 10-minutes person,解決問 題是以 10 分鐘為單位,所以長久下來,我也學習到老師處理事情的超高效率。 一天內 to-do list 有 10 件事情也能分批解決!這本論文可以順利催生也是在萬老 師高效率的指導下才能完成。之前時常因為趕論文而焦慮,老師的鼓勵和安慰都 讓我覺得倍感窩心。真的非常非常感謝老師一路上的提攜!. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. 也非常感謝研究所每位老師的栽培和指導。謝謝開朗愛搞笑的蕭宇超老師、風度 翩翩愛立領的何萬順老師、如仙女下凡的黃瓊之老師、上課嚴肅下課慈祥的徐嘉 慧老師、總是以學生為重的賴惠玲老師、從大一看著我長大的張郇慧老師、笑容 會煞到一推女學生的林祐瑜老師。特別感謝黃瓊之老師和林祐瑜老師來擔任我的 口試委員,能得到你們的肯定真的非常非常開心,我之後一定會繼續加油的!. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 在這三年間,剛好經歷萬老師的可愛女兒─ Vickie 的誕生,因此我才能有機會跟 著老師一起開始兒語習得的研究。為了做長期觀察研究,我們常常必須揹著攝影 機到處去受試兒童家裡錄音。錄音的過程雖然辛苦,但是能陪著小朋友一起成長, 每次去拜訪都聽到小朋友有新的詞彙出現,真的很有成就感!其中最最特別的就 是我第一個錄的小寶寶─甯甯,害羞怕生的甯甯竟然很喜歡我,每次去錄音都是 瘋狂大笑、跑跳、還有講一堆小大人口吻的話。最好笑的是她都直接叫我「涵絜」。 有一次她還問媽媽:「涵絜什麼時候回來?」是用「回來」喔!親愛的甯甯,你 不知道涵絜姊姊有多感動~也謝謝甯甯媽媽在我最後一次去錄音時還頒發了獎 狀和禮物給我!我會一輩子好好珍藏這些回憶的。. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 研究生涯的大部分時間都是待在萬老師的語音暨心理綜合實驗室裡工作,那裡就 像我在政大的另一個家。學長姐、學弟妹都像家人一樣,幾乎天天見面、經常分 享生活大小事~我在趕論文時,幸虧有溫柔體貼的心怡、超高效率的冠霆、語言 學大師明哲、開心果彥棻、配合度超高的佳琳、認真負責的家正、可愛乖巧的翊 倫,若不是你們絕佳的工作能力,我也無法專心寫作,真誠的感謝你們!也特別 iv.

(5) 要感謝在統計上給予我超即時幫助的曹維軒,若沒有你半夜幫我趕跑 SPSS,我 的論文後半部一定會完蛋。祝福你們未來都能畢業順利、工作順利! 回想起剛上研究所時,雖然環境很熟悉,但是人事已非,很多以前大學要好的朋 友都畢業離開學校了。幸虧我們班的同學都非常友善,也很好相處。特別是我們 的四人團體─DHA 花。謝謝空中英語教室老師 David,我們從碩一就常常同一組但 是彼此都不記得實在很好笑;謝謝美食玩樂總監兼姊妹淘芃芃 Angela,除了每次 都要靠你安排行程,也只有你能夠分享所有心情(我也會永遠懷念我們的新加坡 天堂之旅);也要鄭重感謝對這篇論文貢獻良多的音韻小神童亨亨 Henry,每次 論文只要卡卡,去找你講完之後都會像吃了X藥一樣通暢!哈哈哈!還有每次一 聊起來總是沒完沒了,話題辛辣度都不輸康熙,好愛那段天天都演內心小劇場、 天天鼓吹你吃宵夜的日子啊~和 DHA 花住在大公寓的日子大概是我這輩子最棒 的外宿經驗了~. 政 治 大 碩三這一年,我除了做助理工作、寫論文,還要準備聽語所的入學考試。三種壓 立 力同時壓在肩上讓我常常焦慮不安,甚至想放棄考試。每當我撐不下去時,感謝 ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 你總是適時的發現我的不對勁,在我身邊聽我訴苦;謝謝你因為捨不得我太操勞, 給了我很多退路讓我不至於把自己逼瘋;謝謝你總是認真幫我分析問題,又還是 能支持我做的每一個決定;謝謝你懂得趕論文的難處,總是能紓解我容易緊張的 心情。沒有你的陪伴和支持,就不會有這麼豐碩的成果。獻給何韋辰:Thanks for. sit. y. Nat. coming into my life, and thanks for loving me.. n. al. er. io. 最後感謝爺爺、奶奶、爸爸、媽媽多年來的栽培,給我強大的後盾,讓我沒有後 顧之憂可以全力在學業上打拚。尤其是奶奶不間斷的關心和期望,給了我很多信 心。也很謝謝大姑姑的啟蒙,帶我進入語言學的領域,一路上給我建議,讓我能 夠順利完成這個里程碑。感謝楊家大家族源源不絕的愛,培育我樂觀正向的力量。 另外還要感謝所有透過 Facebook 陪伴我、幫我加油打氣的家人、朋友,感謝你 們幫我在通過論文口試的 PO 文上按讚、留言,有你們真好!. Ch. engchi. 我畢業了!耶~. 2013/6/19. v. i n U. v.

(6) Table of content Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................1 1.1 Children’s phonological acquisition ...............................................................................1 1.2 Mandarin tone...................................................................................................................2 1.3 Research gap .....................................................................................................................3 1.4 Research Questions ..........................................................................................................5 1.5 The framework of the thesis .............................................................................................6 Chapter 2 Literature review ....................................................................................................9 2.1 Language universals in first language acquisition ............................................................9 2.1.1 Syllable ....................................................................................................................10 2.1.2 Suprasegmentals ......................................................................................................12. 治 政 大 2.1.2 2 Stress ......................................................................................................... 12 立 2.1.3 Reduplication of motherese ...................................................................................13 2.1.2.1 Intonation ..................................................................................................12. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2 Introduction to Mandarin tonal system ...........................................................................15 2.2.1 The tonal representation systems of Standard Mandarin.........................................15. ‧. 2.2.1.1 Chao (1968).................................................................................................15. sit. y. Nat. 2.2.1.2 Yip (2002) ...................................................................................................16. io. er. 2.2.1.3 Lin (2007) ...................................................................................................17 2.2.2 The tonal representation systems of Taiwan Mandarin ...........................................19. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. 2.2.2.1 Shih (1988)..................................................................................................19. engchi. 2.2.2.2 Fon (1997) ...................................................................................................20 2.2.3 Summary ...............................................................................................................21 2.3 Theory of markedness of tone ......................................................................................22 2.4 Tonal acquisition studies in East Asia ............................................................................23 2.4.1 Thai (Tuaycharoen 1977) ........................................................................................24 2.4.2 Cantonese (Tse 1978; So & Dodd 1995) .................................................................25 2.4.3 Taiwanese (Tsay 2000) ...........................................................................................27 2.4.4 Overview of the cross-linguistic studies ................................................................29 2.5 Tone acquisition on Mandarin ........................................................................................31 2.5.1 Chao (1951) .............................................................................................................31 vi.

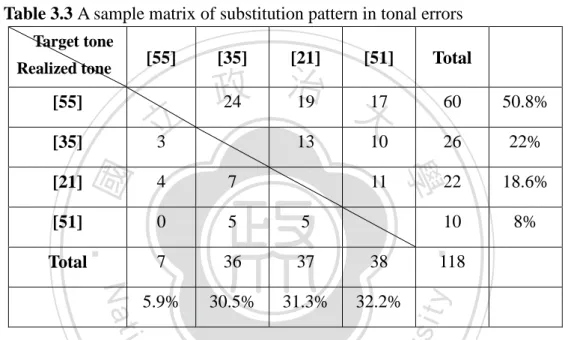

(7) 2.5.2 Li & Thompson (1977)............................................................................................31 2.5.3 Zhu (2002) ...............................................................................................................33 2.5.4 Summary .................................................................................................................33 Chapter 3 Methodology .........................................................................................................35 3.1 Data collection ..............................................................................................................35 3.1.1 Recruitment .............................................................................................................36 3.1.2 Subject .....................................................................................................................36 3.1.3 Observational procedures ........................................................................................37 3.1.4 Recording equipments .............................................................................................38 3.2 Data analysis...................................................................................................................39 3.2.1 Transcription and coding .........................................................................................39 3.2.2 Tone emergence ordering ......................................................................................43. 政 治 大 3.2.4 Substitution pattern立 in tonal errors ..........................................................................46. 3.2.3 Frequency and accuracy rate of tones .....................................................................44. ‧ 國. 學. Chapter 4 Results and analysis .............................................................................................49 4.1 Overall analysis ............................................................................................................50. ‧. 4.1.1 Tone emergence ordering ......................................................................................52 4.1.2 Frequency and Accuracy rate ................................................................................55. y. Nat. sit. 4.2 Subgroup analyses in monosyllabic and disyllabic tokens ...........................................59. er. io. 4.2.1 Monosyllabic tokens ..............................................................................................60. al. v i n C h in the reduplicationUof motherese .........................66 4.2.3 The tone combination [21-35] engchi 4.2.4 Reanalysis in disyllabic tokens ..............................................................................70 n. 4.2.2 Disyllabic tokens ...................................................................................................63. 4.2.5 Reanalysis in overall data ......................................................................................73 4.3 Substitution pattern in tonal errors ...............................................................................77 4.4 The age of acquisition of tones .....................................................................................79 Chapter 5 Discussion ..............................................................................................................81 5.1 Summary of the findings ..............................................................................................81 5.2 Comparison with tonal acquisition studies in Mandarin ..............................................84 5.2.1 Age of acquisition .................................................................................................84 5.2.2 Order of tonal acquisition ......................................................................................85 5.2.3 The tonal combination of reduplication in Taiwan Mandarin ...............................86 vii.

(8) 5.3 Cross-linguistic comparison .........................................................................................87 5.4 Concluding remarks ......................................................................................................90 References .............................................................................................................................91. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i n U. v.

(9) List of Tables Table 2.1 The examples of children’s simplified form in English and French ................11 Table 2.2 The two intonation patterns produced by an English-speaking children Table 2.3 Chao’s (1968) tonal representation system of SC. .......13. ...........................................16. Table 2.4 Lin’s (2007) tonal feature and pitch value .........................................................16 Table 2.5 Lin’s (2007) tonal representation system of SC ................................................17 Table 2.6 Pitch values of the neutral tone ...........................................................................17 Table 2.7 Yip’s (2001) tonal representation system of SC. .................................................18. ............................................19 治 政 Table 2.9 Shih’s (1997) tonal representation system of TM 大.............................................20 立 Table 2.10 The tonal representation adopted in this thesis ................................................22. Table 2.8 Fon’s (1997) tonal representation system of TM. ‧ 國. 學. Table 2.11 Thai tonal system ...............................................................................................24 Table 2.12 Cantonese tonal system .....................................................................................26. ‧. Table 2.13 Taiwanese tonal system ....................................................................................28. y. Nat. Table 2.14 The average error rate of each tone in juncture position .................................28. io. sit. Table 2.15 The acquisition ordering in Thai, Cantonese, and Taiwanese ........................29. n. al. er. Table 3.1 The data collecting information on subjects and recordings ............................37. i n U. v. Table 3.2 The sample of coding ............................................................................................42. Ch. engchi. Table 3.3 A sample matrix of substitution pattern in tonal errors .....................................47 Table 4.1 Subject information .............................................................................................50 Table 4.2 Number of tokens in subcategories ....................................................................51 Table 4.3 Age of emergence of tone ...................................................................................53 Table 4.4 Number of tokens and frequencies of tones in all syllabic tokens ........................56 Table 4.5 Number of tokens and accuracy rates of tones in all syllabic tokens ....................58 Table 4.6 Number of tokens of each syllable in monosyllabic and disyllabic tokens ..........60 Table 4.7 Number of tokens and frequencies of tones in monosyllabic tokens ....................61 Table 4.8 Number of tokens and accuracy rates of tones in monosyllabic tokens ...............62 Table 4.9 Number of tokens and frequencies of tones in disyllabic words at separate syllable positions ...............................................................................................................64 ix.

(10) Table 4.10 Number of tokens and accuracy rates of tones in disyllabic words at separate syllable positions ..................................................................................................65. Table 4.11 Tone combinations of motherese in common nouns and kinship terms .............67 Table 4.12 Modified number of tokens and frequencies of tones in disyllabic words at separate syllable positions ....................................................................................71. Table 4.13 Modified number of tokens and accuracy rates of tones in disyllabic words at separate syllable positions ....................................................................................72. Table 4.14 Modified number of tokens and frequencies of tones in all syllabic tokens .......74 Table 4.15 Modified number of tokens and accuracy rates of tones in all syllabic tokens ...75 Table 4.16 The matrix of substitution patterns of tonal errors in disyllabic words ..............77 Table 4.17 Age of emergence and stabilization of each tone ...............................................79. 政 治 大...............................................81. Table 5.1 Tone acquisition orderings in different measures. 立. Table 5.2 Tone acquisition orderings of cross-linguistic studies ..........................................87. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. x. i n U. v.

(11) List of Figures Figure 4.1 Frequencies of tones in all syllabic tokens ...........................................................57 Figure 4.2 Accuracy rates of tones in all syllabic tokens ......................................................58 Figure 4.3 Frequencies of tones in monosyllabic tokens .......................................................61 Figure 4.4 Accuracy rates of tones in monosyllabic tokens ..................................................62 Figure 4.5 Frequencies of tones in disyllabic words at separate syllable positions ...............64 Figure 4.6 Accuracy rates of disyllabic words in separate syllable positions .......................65 Figure 4.7 Number of tokens in all combinations in disyllabic tokens. ...............................69. Figure 4.8 Modified tone frequency of disyllabic words in separate syllable positions ........71. 政 治 大. Figure 4.9 Modified accuracy rates of disyllabic words in separate syllable positions .........72. 立. Figure 4.10 Modified frequencies in overall data ..................................................................74. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 4.11 Modified accuracy rates in overall data .............................................................75 Figure 4.12 Percentage of the realized tone in tonal errors ...................................................78. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xi. i n U. v.

(12) 國立政治大學研究所碩士論文提要 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:台灣華語聲調習得 指導教授:萬依萍. 博士. 研究生:楊涵絜. 政 治 大 本篇論文是針對六位以台灣華語為母語的嬰幼兒,採長期觀察的方式,研究 立 華語聲調的習得,並詳細描述單音節詞和雙音節詞之中聲調出現順序、頻率、正 論文提要內容:(共一冊,19,799 字,分五章). ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 確率、以及代換模式。本研究同時要用 Yip (2002)的標記理論來檢驗各種不同聲 調語言中的共通性。 本研究一共觀察了有六位年齡在十個月至一歲一個月的嬰幼兒長達八個月。 以兩個禮拜一次的頻率收集嬰幼兒和母親或照顧者之間的自然對話。並利用錄製 回來的高規格影音檔做譯寫和分析。 結果顯示[55]最早出現,也是頻率最高、正確率最高的聲調。而[51]在聲調 出現順序、頻率、及正確率都是排在第二。[35]和[21]就比較晚出現,和前面兩 個聲調相比,頻率及正確率都較低。輕聲不管是出現順序、頻率、或正確率都排 在最後。 本研究結果還發現台灣華語中有一特殊的聲調組合[21-35]。在台灣華語中, 媽媽對幼兒說話時所使用的「媽媽語」很常把這個聲調組合套用在重疊詞中。而 這個聲調組合也被幼兒高度模仿使用。因此本研究認為幼兒發出的這個高頻的聲 調組合[21-35]有可能是受到照顧者的影響,並且也認為幼兒並非分開習得此兩個 聲調,而是把此兩聲調當作一個整體來習得。 最後,將所有跨語言的分析結果拿來檢驗 Yip (2002)的標記理論後,我們發 現幾乎所有語言都支持平調比曲折調早習得、降調比升調早習得。但是除了泰文 之外,沒有語言能支持 Yip (2002)提出的低調比高調早習得。因此,語言習得的 證據能證明平調、降調、高調比曲折調、升調、低調還普遍。. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 關鍵詞:兒童語言發展、聲調習得、出現順序、頻率、正確率、代換模式、台灣 華語. xii.

(13) Abstract The purpose of this study is to describe children’s tonal development by analyzing the tone emergence, frequency, accuracy rate, and substitution pattern, based on observing monosyllabic and disyllabic utterances in six Mandarin-speaking children in Taipei, Taiwan. This study also aims to examine several cross-linguistic data the theory of markedness presented by Yip (2002). Six subjects are investigated with the age range from 0;10 to 1;6. The data collection is conducted fortnightly by the author and the research team. Based on video and sound files, a set of coding are employed for data analysis. The results showed that the high-level tone [55] emerged the first, and it also ranked as the most frequent and stable tone. Falling tones [51] were consistently ranked in the second place within tone emergence, frequency, and accuracy rate. Rising tones [35] and low-level tones [21] appeared late, and were also less frequent and stabilized later than [55] and [51]. The neutral tone was emerged and stabilized the last appeared and last acquired tone. This study also found the dominated tone combination [21-35] applied particularly in the reduplications of motherese in Taiwan Mandarin. The tone combination [21-35] was proposed to be influenced by motherese, and was acquired as a prosodic whole. The results of this study and all the cross-linguistic data are examined in Yip’s theory of markedness. The first two constraints obtained more evidence that the features of level and falling in tones were suggested to be the unmarked features in tonal languages. Regarding the third constraint, because most of the tone acquisition data indicated that high tones were acquired earlier than low tones, the more unmarked tone feature should be level, falling, and high.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Keywords: phonological development, tone acquisition, tone emergence, frequency and accuracy rate, substitution pattern, Taiwan Mandarin. xiii.

(14) Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Children’s phonological acquisition The purpose of this thesis is to discuss issues involving in tone acquisition from. 政 治 大. Mandarin-speaking children in Taiwan. By observing the tone acquisition for children in. 立. early developmental stages, this research aims to add literature on cross-linguistic studies. ‧ 國. 學. and to test a number of questions raised in the former phonological acquisition theories.. ‧. Children’s phonological development proceeds rapidly. In their early developmental. Nat. io. sit. y. stage, infants are sensitive to prosodic cues. Lenneberg (1967) pointed out that at the age. er. of 0;8, children could distinguish rising or falling pitch contours. Many researchers also. al. n. v i n proved that the suprasegmentalCfeatures, as intonation and stress, were acquired h e n gsuch chi U. earlier and better than segments (consonants and vowels) (Lenneberg, 1967; Kaplan, 1970; Demuth, 1996). The earliest age for the mastery of a tonal language system was at 1;4 in Thai-speaking children (Tuaycharoen, 1977). Other studies also presented that children have mastered their tonal systems with little errors after the age of 2;0 (Li & Thompson, 1977; Tse, 1978; So & Dodd, 1995). It is reported that by the age of five, children could fully acquire all the phonemes in their native languages (Cantwell & Baker, 1.

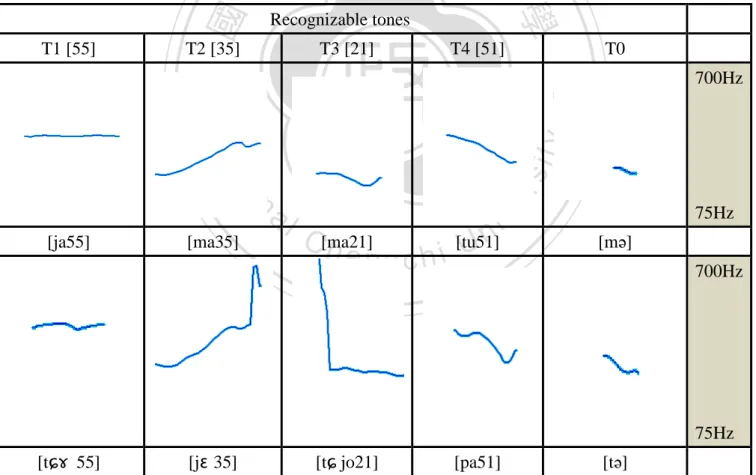

(15) 1987). Linguists are highly interested in children’s acquisition on suprasegmental features. To investigate the area of tone acquisition, there are three essential issues needed to be discussed in children’s development of tone productions. They are: (1) the tone emergence ordering, (2) the frequency and accuracy rate, and (3) the substitution pattern in tonal errors. 1.2 Mandarin tone. 政 治 大. Mandarin is the most widely spoken tone language, and it is the official language in. 立. both China and Taiwan. Tone is defined to be one kind of the suprasegmentals. It is a. ‧ 國. 學. physical signal involving frequency (Hz). The change of frequency could result in pitch. ‧. change, and tones would be produced by certain pitch register or contour. People. Nat. io. sit. y. speaking tonal languages use tones to distinguish lexical meanings. Standard Mandarin. er. has four lexical tones, high, rising, low-falling-rising, falling, and one neutral tone. Chao. al. n. v i n C hto specify the toneUvalues in Standard Mandarin (1930) have provided a 5-point scale engchi. where 1 represented low, 3 was mid, and 5 was high. According to this tonal representation, the tone letters of the four tones were [55], [35], [214], and [51]. Besides the four lexical tones, Lin (2007) mentioned that the neutral tone which only appears in the non-initial position was a low tone underlyingly, but its tone value would change depending on the preceding citation tone.. 2.

(16) 1.3 Research gap By age-tracking children’s speech tokens in early stages, researchers could provide evidence to see whether tones are acquired in a universal ordering. However, studies focusing on tonal acquisition were still few, and there were questions have not been answered. First, the orderings of tone acquisition in cross-linguistic tonal studies were inconsistent. Several researchers found that high tones and falling tones were acquired. 政 治 大. earlier than low tones and rising tones regardless of Mandarin, Cantonese, or Taiwanese. 立. (Li & Thompson, 1977 and Zhu, 2002 for Mandarin; Tse, 1978 and So & Dodd, 1995 for. ‧ 國. 學. Cantonese; Tsay, 2001 for Taiwanese). However, evidence from the Thai data showed that. ‧. the Thai-speaking children acquired the rising tone [224] earlier than the falling tone [51]. Nat. io. sit. y. (Tuaycharoen, 1977). Due to the inconsistent results, the conclusion of tone acquisition. er. ordering could still not be made.. al. n. v i n C h research specifying Besides, there was no sufficient e n g c h i U the frequency and accuracy rate. on immature tones. Before children fully master the tonal system, there would be an unstable period that a number of tonal errors would occur. The frequency and accuracy rate provide a good way to measure the preference and the degree of stabilization of tones. From the studies concerning tone acquisition in Mandarin, though Li and Thompson (1977) indicated that [35] and [21] were making tonal errors during two- and three-word stage, they did not provide specific accuracy rate in these two tones. Without the accuracy 3.

(17) rate, it would be dangerous to determine a tone is “acquired” or not. The degree of development of tones was more specific in Zhu’s (2002) study. She applied a criterion (66.7% of accuracy rate) for determining the stabilization of tones, and found that [55] and [51] were stabilized earlier than [35] and [21], while the neutral tone was stabilized the last. Nevertheless, Zhu did not calculate the frequency in each tone, and the subjects recruited in her study were children who grew up in Beijing. It was reported that the. 政 治 大. Mandarin in Taiwan had many phonological differences from that in Beijing (Kubler,. 立. 1985; Duanmu, 2000). Due to different language environment, it is necessary for the. ‧ 國. 學. current study to conduct the tonal acquisition study again in Taiwan Mandarin.. ‧. There were also few researchers analyzing monosyllabic and disyllabic tokens. Nat. io. sit. y. separately, and few studies compared the differences between these two types of speech. er. tokens. When talking to young children, adults would shift the way of normal speech to a. al. n. v i n high frequency, reduplicated, and C simplified called "motherese" (Carroll, 2008). h e n gway chi U Regarding the motherese in Mandarin, care-takers also like to use reduplicated form in most lexicon, and the most preferred tone combination was a low-falling tone [21] followed by a rising tone [35] (Yang, 2012). For instance, standard form of the word 'shoes' is pronounced as [ɕje35], but it is commonly used as [ɕje21-ɕje35] in the reduplicative form of motherese; some kinship terms such as [pa51-pa] ‘dad’ and [je35-je] ‘grandfather’ would also transform into [21-35] tone combination and become 4.

(18) [pa21-pa35] ‘daddy’ and [je21-ye35] ‘grandpa’ in motherese. Thus, there would be a tremendous amount of tokens produced in the [21-35] combination. This would result in a bias in the whole number of occurrences. To deal with this problem, this study would manage to separate the disyllabic words from monosyllables, analyze the two types of tokens separately, and cope with the particular tone combination [21-35] separately. Based on the research gap mentioned above, including the inconsistency on. 政 治 大. chronological orderings in different languages, the unspecific measurement on immature. 立. tones, and the unnoticed tone combination in motherese, it is worthwhile to discuss more. ‧ 國. 學. on these issues and provide answers to the following research questions.. ‧. 1.4 Research Questions. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. below:. y. The research questions would be analyzed and discussed by following the sequence. Ch. engchi. (1) Regarding the issue of tone emergence ordering:. i n U. v. Which tone appears first? What is the chronological ordering of the emergence among all tones? At what age does the first tone appear? At what age would all the Mandarin tones be applied to children’s meaningful utterances? Do children show similar tone emergence ordering cross-linguistically? Would the ordering reflect the degree of ease of articulation? (2) Regarding the issues of frequency and accuracy rate (stabilization): 5.

(19) What is the most frequent tone produced by subjects? What is the ordering of frequency in the four tones, including the neutral tone? What is the ordering of accuracy rate in all the Mandarin tones? Do easier produced tones present higher accuracy rate? Do higher frequency tones also have higher accuracy rate? Do tones that appeared earlier have a higher frequency and accuracy rate in the occurrences? Would there be universal ordering of stabilization among different Asian tone acquisition studies?. 政 治 大. (3) Regarding the issue of substitution pattern in tonal errors:. 立. What kind of strategy would children use to replace the un-mastered tones? Would they. ‧ 國. 學. replace the un-mastered tone with more frequent tones or more accurate tones? Which. ‧. tone is more unstable and is replaced by other tones more frequently? Which tone is more. Nat. io. sit. y. likely to replace the unstable tones? Are there obvious individual differences among. n. al. er. children's substitution strategies?. 1.5 The framework of the thesis. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In chapter 1, I provided a brief introduction to indicate what kind of issues are going to be discussed in the whole thesis, and what is the motivation for dealing with these issues; the four main research questions were also addressed. In Chapter 2, firstly I will mention the language universals in first-language acquisition in 2.1, and the Mandarin tonal system representations will be introduced in 2.2. Section 2.3 and 2.4 include studies specifically on tone acquisition. The comparison among tone acquisition studies of Asian 6.

(20) languages is in 2.3; the foundation of tone acquisition studies in Mandarin is in 2.4. The last section 2.5 will introduce the tone acquisition theories. Chapter 3 contains the methodology which can be viewed in two separate parts. Section 3.1 is the data collection method describing how I obtained the speech tokens, and section 3.2 is the data analysis method explaining how the data were arranged. Chapter 4 will display the results and analysis in tables and graphs. Section 4.1 shows the overall results in all data. Section 4.2. 政 治 大. applies different measure to analyze the monosyllabic and disyllabic tokens separately. In. 立. section 4.3, the substitution patterns in tonal errors are offered, and in section 4.4, the. ‧ 國. 學. ages of emergence and stabilization in all subjects are summarized. The discussion and. ‧. explanation are provided in chapter 5. Section 5.1 summarizes the findings in chapter 4.. Nat. io. sit. y. Section 5.2 and 5.3 are the comparison among different studies in Mandarin and different. n. al. er. cross-linguistic studies. Section 5.4 is the concluding remarks and the suggestion for further research.. Ch. engchi. 7. i n U. v.

(21) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 8. i n U. v.

(22) Chapter 2 Literature review This chapter consists of three sections. Firstly, I will review studies with universals in children’s phonological acquisition in section 2.1. Secondly, the various representations. 政 治 大. of Mandarin tonal system will be introduced in 2.2. Section 2.3 consists of a theory of. 立. tonal markedness. Later on, the important studies related to children’s tone acquisition in. ‧ 國. 學. Asian tone languages will be presented in 2.4. Lastly, the most related references focusing. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.1 Language universals in first language acquisition. ‧. on Mandarin tonal acquisition will be shown in 2.5.. er. Many researchers proposed that there were chronological stages in children’s early. al. n. v i n vocalization, which means that C children the world acquired languages by following h e nacross gchi U similar steps. (Lenneberg 1967; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1971). The four stages of children’s early vocalization divided by Kaplan & Kaplan (1971) are presented below: Stage 1: Crying (0;0-0;6)-The cries are identified by parents as angry or physical pain.. Stage 2: Pseudocry and Noncry vocalization (0;4-0;5)- Begin to use the articulatory organs, and the utterances become different from crying. 9.

(23) Stage 3: Babbling and Intonated vocalization (0;5-0;8)- The vocalization becomes speech-like. Vowel-like and consonant-like sounds are combined into reduplicated syllable structure. Infants begin to imitate adults’ intonation pattern. Stage 4: Patterned Speech (0;9-0;12)- A large number of sounds appear, and child’s first word begins to appear.. 政 治 大. Although there were some overlapping among each stages and not all researchers agreed. 立. the division of the stages, the chronology of these development still gained consensus.. ‧ 國. 學. The reason why the chronology is proved universally may be attributed to the. ‧. biological maturation of brain and motor control. Neurologists and psychologists. Nat. io. sit. y. proposed that babbling occurs automatically when the relevant structures in the brain. er. have reached a critical level of maturation (Preyer, 1882). Before the maturation of the. al. n. v i n C h found that children brain and motor control, Oller (1974) e n g c h i U would simplify the speech. sound they perceived and construct a simplified sound system to ease the burden on their short-term memories and motor coordination. 2.1.1 Syllables It was observed that children’s early syllable structures in the babbling stage were simplified and would go through a regular progression: V, CV, and CVCV (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1971; Kies 1995). 10.

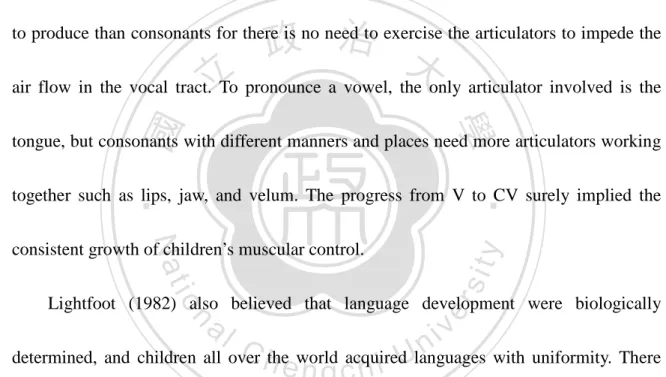

(24) 1. V (The vocalic sounds are like aaa, eee, and uuu.) 2. CV (Children combine consonants and vowels into open syllables, such as ta and ma.) 3. CVCV (There are reduplications repeating frequently. The consonants and vowels are in ABAB form, such as papa, nene, and tata.) The syllable structures began from simply vowels without consonants. Vowels are easier. 政 治 大. to produce than consonants for there is no need to exercise the articulators to impede the. 立. air flow in the vocal tract. To pronounce a vowel, the only articulator involved is the. ‧ 國. 學. tongue, but consonants with different manners and places need more articulators working. ‧. together such as lips, jaw, and velum. The progress from V to CV surely implied the. Nat. io. sit. y. consistent growth of children’s muscular control.. er. Lightfoot (1982) also believed that language development were biologically. al. n. v i n C hthe world acquiredUlanguages with uniformity. There determined, and children all over engchi were several examples extracted from Demuth (2010) for how children in different languages used similar rules to truncate adults’ target forms. Table 2.1 The examples of children’s simplified form in English and French Adults’ form English [spәˈk ɛ ti] French [paˈtat]. Children’s form. Meaning. Age. [ˈk ɛ ti] [pәˈtæ:]. ‘spaghetti’ ‘potato’. 1;2 1;4. In Table 2.1, an English-speaking child imitated adult’s [spәˈ kɛ ti] as [ˈ kɛ ti], and a French-speaking child produced [paˈtat]. as [pәˈtæ:] . Both children used the same 11.

(25) phonological rule to simplify adults’ trisyllabic words into disyllables, which were the CVCV structure in the study of Kaplan and Kaplan (1971) mentioned above. Children’s immature muscular control unables them to produce consonant clusters like [sp] or close syllable like [tat]. Thus, children naturally simplified or truncated consonants when producing syllables more complicated than open syllables. 2.1.2 Suprasegmentals. 政 治 大. Regarding the stages Kaplan & Kaplan (1971) presented above, they mentioned that. 立. in the third stage, infants began to imitate adults’ intonation pattern. This finding. ‧ 國. 學. suggested that children’s suprasegmental acquisition, such as stress, intonation, pitch, and. ‧. tone, started very early in the developmental process. Many studies proved that these. Nat. io. sit. y. suprasegmental characteristics were acquired very early and even earlier than segments. er. (Lenneberg, 1967; Kaplan, 1970; Demuth, 1996). Crystal (1970) also cited that children. al. n. v i n Cexercise at ages as young as 0;7 to 0;10 could suprasegmental characters much stably and heng chi U readily than segmental characters. 2.1.2.1 Intonation For English-speaking children, it was found that infants could distinguish and produce falling and rising intonation contours at 0;8 (Kaplan 1970). When infants were in their late babbling stage, they could well imitate adults’ intonation patterns despite with immature segments (Kies 1995). Kies provided an example to prove that an 12.

(26) English-speaking child could uttered two different intonation patterns at the age of 0;8. Table 2.2 The two intonation patterns produced by an English-speaking child. (1). o. tu. i. ba ba ma. (Declaratives). ba (2). (Interrogatives). dow ga. m-mu. 政 治 大 he had already developed the rising and falling in declarative and interrogative intonation 立 In these two sentences, although most of the syllables were simplified to V or CV forms,. ‧ 國. 學. patterns which refer to different meanings in English.. ‧. 2.1.2.2 Stress. sit. y. Nat. What’s more, linguists also noticed that English-speaking children used stress to. n. al. er. io. distinguish meanings as early as they uttered their first words (Kies 1995). Engel (1973). Ch. i n U. v. reported that one child used [‘mama] to call his mother but [ma’ma] to his father at 0;10.. engchi. The only difference of these two utterances laid on the stress position that ‘mother’ was stressed on the first syllable and ‘father’ was stressed on the second syllable. These examples could clarify that children do acquire prosodic features in their early phonological development. 2.1.3 Reduplication of motherese Motherese, also named child-directed speech (CDS), refers to the speech form used. 13.

(27) by adults in talking to young children. Adults would naturally shift the way of normal speech to a high pitched, slow, reduplicated, and simplified way when talking to children (Carroll, 2008). There was a study pointing out that infants paid more attention to repetitive form than regular conversation, and the use of child-directed speech facilitated children to in language learning (Matychuk, 2005). The use of reduplication in motherese facilitated children's language development in several aspects: Phonologically, children. 政 治 大. could perceive the same syllable twice because the consonants and vowels in. 立. reduplications are identical in the first and second syllables. Morphologically, the. ‧ 國. 學. syllables are simplified to CVCV forms, and the consonants and vowels are replaced to. ‧. earlier acquired phonemes. Therefore, children better repeated syllables that were. io. sit. y. Nat. reduplicated.. er. Reduplication was the most common form applied in children’s early production. al. n. v i n C h in the study of U (Grunwell, 1982). As mentioned above e n g c h i Kaplan and Kaplan (1971), the. CVCV structure were repeated frequently by children, and the consonants and vowels were in ABAB form, such as papa, mama, and tata. In the reduplication of motherese in Mandarin, Yang (2012) found that in Taiwan, most care-takers would produce reduplications in a particular tone combination which is a low-falling followed by a rising tone, such as [njow21-njow35] ‘a cow’ and [y21-y35] ‘a fish.’ Children also uttered most reduplications in [21-35] combination. It was obvious that children’s preference of tone 14.

(28) combination was identical to that of adults’ reduplication in motherese. Whether children’s form was affected by adults’ input needs more specific methods to examine, but the examination would not be conducted in this current study. 2.2 Introduction to Mandarin tonal system Mandarin tones has been classified and transcribed into several different systems. In this section, I will introduce tonal representations both in Standard Mandarin and Taiwan. 政 治 大. Mandarin in 2.2.1 and 2.2.2. A summary and the adopted tonal representation will be. 立. provided in 2.2.3.. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2.1 The tonal representation systems of Standard Mandarin. ‧. The Standard Mandarin (henceforth SC) is the official language in China. The. Nat. io. sit. y. standard pronunciation of SC is based on Beijing dialect, but it absorbed many other. er. Chinese dialects in different regions (Duanmu 2000). Despite the variance, the tonal. al. n. v i n C h here are the descriptive representation systems of SC reviewed view of Mandarin. engchi U 2.2.1.1 Chao (1968). Chao (1968), also known as a musician, established the five-point scale to transcribe the pitch of tones in Standard Mandarin (henceforth SC). He proposed that the tone classification in Mandarin could be realized as pitch differences, and the pitch register was shown in a range numbered 1 to 5. The bigger the number was, the higher the pitch register would be. 15.

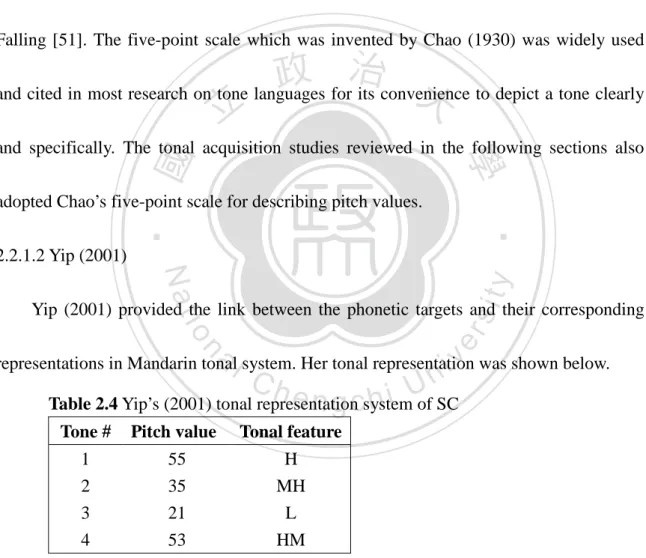

(29) Table 2.3 Chao’s (1968) tonal representation system of SC Tone # 1 2 3 4. Chinese Name. Tonal feature. Yinping Yangping Shangsheng Qusheng. High Level High Rising Low Falling-Rising High Falling. Pitch value 55 35 214 51. In Table 2.3, the four tones named yinping, yangping, shangsheng, qusheng were described as High Level [55], High Rising [35], Low Falling-Rising [214], and High Falling [51]. The five-point scale which was invented by Chao (1930) was widely used. 治 政 大 to depict a tone clearly and cited in most research on tone languages for its convenience 立 ‧ 國. 學. and specifically. The tonal acquisition studies reviewed in the following sections also adopted Chao’s five-point scale for describing pitch values.. ‧. 2.2.1.2 Yip (2001). sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Yip (2001) provided the link between the phonetic targets and their corresponding. i n U. v. representations in Mandarin tonal system. Her tonal representation was shown below.. Ch. engchi. Table 2.4 Yip’s (2001) tonal representation system of SC Tone #. Pitch value. Tonal feature. 1 2 3 4. 55 35 21 53. H MH L HM. In this tonal system, tones were considered to have a head and a contour in the following. The capital H and L in Tone 1 and Tone 3 represented level tones, and MH and HM in Tone 2 and Tone 4 were contour tones. With regard to the pitch values, the representation of Tone 1 and Tone 2 agreed with those in Chao (1968), but Tone 3 was presented as [21] 16.

(30) without the final rising and Tone 4 was presented as [53] with partial falling from high to mid. 2.2.1.2 Lin (2007) The system Lin (2007) adopted in her studies concerning SC was presented both with tone features and pitch values. She mentioned that most analyses of SC used only high and low distinction, but it was not specific enough. There were three distinctions of. 政 治 大. register in Lin’s system, which were high, mid, and low, and they would be presented in. 立. Table 2.5 Lin’s (2007) tonal feature and pitch value H (high) M (mid) L (low). er. io. sit. y. 4 or 5 3 1 or 2. ‧. Tonal feature. Nat. Pitch value. 學. ‧ 國. capital letters (H, M, and L).. In Table 2.5, it defined the corresponding tonal features of the pitch values respectively.. al. n. v i n C The highest two numbers, 4 and 5,hwere in H; number 3 which referred to a e ncategorized gchi U middle pitch sound fitted in M; the lowest two digits, 1 and 2, had the low pitch feature, so were sorted in L. The tonal features could be used to transcribe into the digital system. Table 2.6 Lin’s (2007) tonal representation system of SC Tone # 1 2 3 4. Tonal feature. Pitch value. HH MH LH (in phrase final syllable) LL (before another tone) HL (in phrase final syllable) HM (before another tone) 17. 55 35 214 21 51 53.

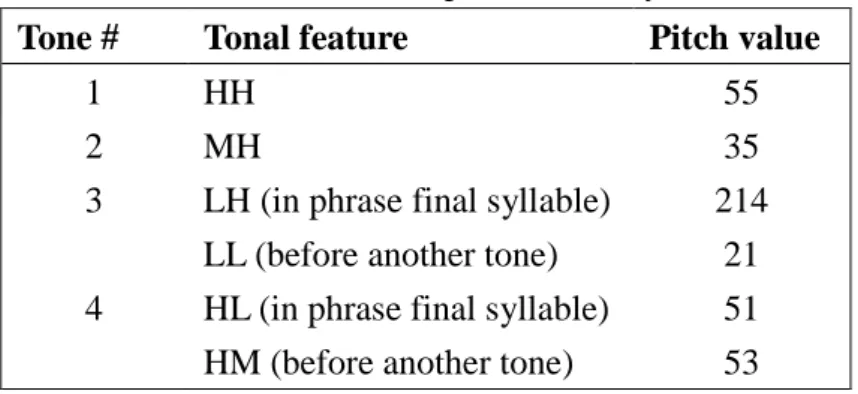

(31) The four tones in Table 2.6 were transcribed into pitch register features. For Tone 1, the high level [55] pitch value mapped with HH in this system; Tone 2 which with [35] pitch value was presented by MH. There were respectively two representations in Tone 3 and Tone 4 for a more detail distinction regarding different syllable positions. The basic forms of these two tones were shown in LH for Tone 3 and HL for Tone 4. Yet, it was believed that final part of Tone 3 and Tone 4 would be reduced when followed by another tone.. 政 治 大. When these two tones were not in syllable-final position, the rising part of Tone 3 would. 立. be missing and presented as LL; the falling part would become [53] and be presented as. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. HM.. The neutral tones which usually appear in grammatical particles or the second. Nat. io. sit. y. syllable of reduplicated kinship terms were precisely depicted in Lin’s (2007) book.. er. Phonologically, a neutral tone was unstressed and was a low tone underlyingly. However,. al. n. v i n C h when followingUdifferent stressed tones. the pitch values were found to be different engchi Table 2.7 Pitch values of the neutral tone Tone #. Tone feature. T1 + T0 T2 + T0 T3 + T0 T4 + T0. 55 + 2 35 + 3 21 + 4 53 + 1. Example [ma55 ma2] [lai35 lə3] [tɕ je21 tɕ je4] [khan53 lə1]. ‘mother’ ‘came’ ‘older sister’ ‘saw’. The Table 2.7 showed the pitch values after each tone. The tone values remained low when following T1 and T4, but when following T2 and T3, the values would rise to [3] and [4]. The examples in the right column showed where the neutral tone could appear 18.

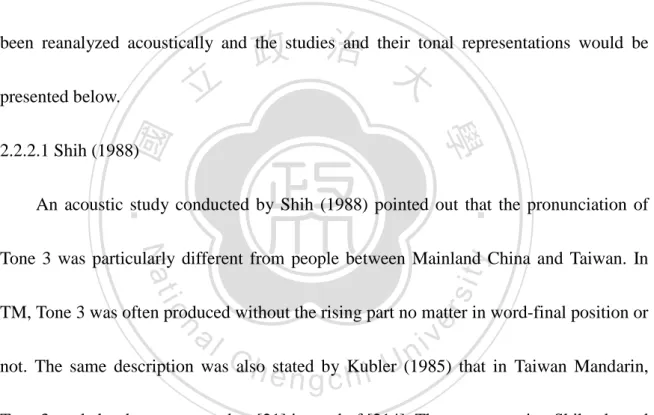

(32) and which pitch value would be surfaced respectively. 2.2.2 The tonal representation systems of Taiwan Mandarin (TM) Many linguists observed that the Mandarin in Taiwan (henceforth TM) was distinct from SC which spoken in Mainland China (Kubler, 1985; Fon, 1997; Fon & Chiang 1999; Duanmu, 2000; Lin, 2007). The tone change in TM may result from the influence of Taiwanese, the dialect widely spoken in Taiwan. The specific tone values of TM have. 政 治 大. been reanalyzed acoustically and the studies and their tonal representations would be. 立. presented below.. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2.2.1 Shih (1988). ‧. An acoustic study conducted by Shih (1988) pointed out that the pronunciation of. Nat. io. sit. y. Tone 3 was particularly different from people between Mainland China and Taiwan. In. er. TM, Tone 3 was often produced without the rising part no matter in word-final position or. al. n. v i n not. The same description wasC also Kubler h estated i U(1985) that in Taiwan Mandarin, n gbyc h Tone 3 tended to be pronounced as [21] instead of [214]. The representation Shih adopted was presented below. Table 2.8 Shih’s (1988) tonal representation system of TM Tone #. Tonal feature. 1 2 3 4. HH MH LL HL. In Table 2.8, Shih used HH to represent the high-level tone, and MH to represent the 19.

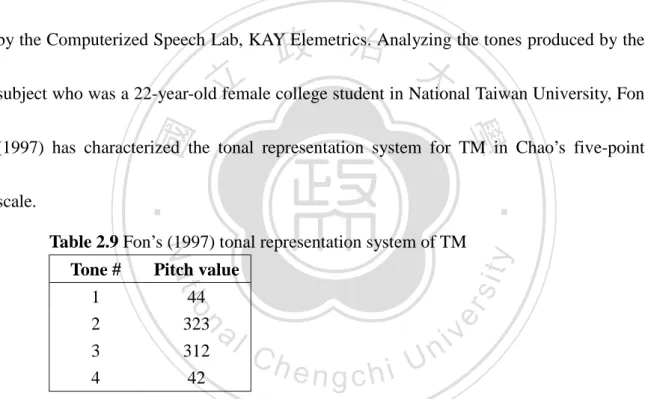

(33) rising tone. Tone 4 was presented in HL which was considered a complete falling. Due to the dialectical variance mentioned by Kubler (1985) and Shih (1988), Tone 3 which often produced without the rising part was showed to be LL in Shih’s Taiwan Mandarin tonal system. 2.2.2.2 Fon (1997) Fon (1997) measured the pitch height, duration, and slope steepness of the four tones. 政 治 大. by the Computerized Speech Lab, KAY Elemetrics. Analyzing the tones produced by the. 立. subject who was a 22-year-old female college student in National Taiwan University, Fon. ‧ 國. 學. (1997) has characterized the tonal representation system for TM in Chao’s five-point. 1 2 3 4. 44 323 312 42. n. al. er. Pitch value. io. Tone #. sit. Nat. Table 2.9 Fon’s (1997) tonal representation system of TM. y. ‧. scale.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The pitch values of the four tones presented in Table 2.9 were totally different from the system invented by Chao (1968) which has been shown in Table 2.3. Fon (1997) argued that the system she proposed has acoustic fact, and the subject enrolled was born in Taiwan. Thus, the result of the tonal representation would be so distinct from that in Chao’s (1968) study. In fact, the two main distinctions between SM and TM lied in the pitch range and the contour changes of Tone 2 and Tone 3. The pitch range narrowed to a 20.

(34) four-point scale. The height in Tone 1 lowered from [55] to [44], and the pitch range for Tone 4 also narrowed from [51] to [42]. On the other hand, Fon presented Tone 2 as a dipping tone whose contour was [323], and the contour was similar to the pitch value in Tone 3 presented as [312]. A further perceptual study conducted by Fon and Chiang (2004) illustrated that Tone 2 and Tone 3 had crucial differences between duration, steepness, and height. The. 政 治 大. duration in Tone 2 was longer than Tone 3, and the slope of Tone 2 was not steeper than. 立. Tone 3. The higher pitch of Tone 2 in the ending point was a cue for distinguishing Tone 2. ‧ 國. ‧. 2.2.3 Summary. 學. and Tone 3.. Nat. io. sit. y. While there were several different tonal representation provided by phonologists and. er. phoneticians in Standard Mandarin and Taiwan Mandarin, how to determine which tonal. al. n. v i n system is the most suitable one?CDuanmu suggested that it was allowed to slightly h e n (2000) gchi U modify the transcription of the tonal representation if only if the modified form does not cause meaning contrast in Mandarin. For example, the [21] and [11] in Mandarin do not distinguish meanings, so it does not matter whether we call Tone 3 as a low falling or a low level. In this thesis, I will mainly adopt the five-point scale invented by Chao (1968) because it is the basic system adopted by most of the phonetic studies. To accommodate 21.

(35) the change of tone in Taiwan Mandarin which proposed by Shih (1988) and Kubler (1985), Tone 3 would be modified to [21] for the dialect variation in TM. Table 2.10 The tonal representation adopted in this thesis Tone. Pitch value. Tonal feature. Tone 1 Tone 2 Tone 3 Tone 4 Neutral. 55 35 21 51 neut. high-level rising low-level falling neutral. Table 2.10 showed the pitch value and tonal features which will be adopted in this study.. 治 政 大be [55], [35], [21], and [51]. The transcription used for the four tones respectively would 立 ‧ 國. 學. The corresponding tonal features of the tones would be high-level, rising, low-level, and falling. The neutral tone would be transcribed in the abbreviation ‘neut.’. ‧. 2.3 Theory of markedness of tone. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Yip (2001) presented a theory of tonal markedness to distinguished marked features. i n U. v. and unmarked feature in tone. The tonal markedness theory was derived from three types. Ch. engchi. of data. The first type of data was from Hashimoto’s (1987) survey on tone sandhi in 83 dialects of Chinese. Second, she provided data from Cheng’s (1973) quantitative study of Chinese tones in which the tonal inventories of 73 dialects were studied. The third type of evidence was from the acquisition studies conducted by Clumeck (1980) and Li and Thompson (1978). The evidences could be generalized into three rules, and Yip stated that the markedness rules was used “to minimize articulatory effort.”. 22.

(36) Minimize articulatory effort a. contour tones are more marked than level tones b. rising tones are more marked than falling tones c. high tones are more marked than low tones Yip summarized Hashimoto’s (1987) study that contour tones were more likely to be leveled in tone sandhi, and similar results were also found in children’s acquisition data. 政 治 大. (Li & Thompson,1978; Clumeck, 1980). In numerous tonal inventories which presented. 立. by Cheng (1973), it was more likely to have falling tones in the tonal system than rising. ‧ 國. 學. tones. The third constraint focused on comparing level tones. She found that high level. ‧. tones were more marked because it needed more strength and could not “minimize. Nat. io. sit. y. articulatory effort.” From this point of view and the evidences from numerous dialects,. er. she concluded that low level tones were more unmarked. The three tonal markedness. al. n. v i n rules could be examined by the C acquisition from cross-linguistic studies to determine h e n gdata chi U the universal features of tones. 2.4 Tone acquisition studies in East Asia In this section, I will review several tone acquisition studies cross-linguistically, including Thai, Cantonese, and Taiwanese. Linguists are interested in whether there are language universals in first language acquisition. The tone acquisition studies reviewed here will be compared to the results of the current study in the discussion section. In this 23.

(37) section, a Thai study focusing on phonetic and phonological development in early speech will be presented in 2.4.1. Two longitudinally conducted researches on Cantonese tone acquisition will be described in 2.4.2. A Taiwanese study, which was also conducted longitudinally, would be reviewed in 2.4.3. Then, there will be an overview of the cross-linguistic tonal acquisition studies in section 2.4.4. 2.4.1 Thai. 政 治 大. Thai is the official language used in a southern Asian nation, Thailand. There are five. 立. tones in Thai’s tonal system. There are three level tones, including High, Mid, and Low;. ‧ 國. 學. and the other two tones are contour tones, which are the Rising tone and the Falling tone.. ‧. Examples of contrastive meanings for the same syllable are presented in Table 2.11.. 1 2 3 4 5. Mid Low Falling High Rising. 33 11 51 45 224. n. al. Ch. Examples khaa33 khaa11 khaa51 khaa45 khaa224. engchi. y. Pitch value. sit. Tone feature. io. Tone. ‘a grass’ ‘galangal’ ‘to kill’ ‘to engage in trade ‘leg’. er. Nat. Table 2.11 Thai tonal system. i n U. v. Tuaycharoen (1977) observed the tone acquiring order and age from her son between the age of 0;3 to 1;6. The data collection was done by the author at home about twice a week. The recording collected the natural interaction between the child and his parents and grandparents whose mainly used language was Bangkok Thai. The finding revealed that [33] and [11] were first acquired at the first-word stage aged 0;11, and the next 24.

(38) acquired tone was the rising tone [224] which was learned by 1;2. The high tone [45] and falling tone [51] appeared unstably at 1;3 to 1;6. To sum up, the order of the tone acquisition on Thai in this particular study was presented to be: [33], [11]> [224]> [45], [51]. 2.4.2 Cantonese Cantonese is a Chinese dialect spoken by people in Hong Kong and Macau in. 政 治 大. southern China. The tonal system is categorized into six contrastive tones, including four. 立. level tones and two rising tones. There are three extra-short tones (entering) which are. ‧ 國. 學. allotones of three level tones and occur only on syllables which are closed by plosives.. ‧. The four level tones are [55], [33], [22] and [11] and Tse (1978) categorized them into. Nat. io. sit. y. Upper Even, Upper Going, Lower Going, and Lower Even. The two contour tones are. er. different from pitch height that the Upper Rising [25] starts from mid to high, and the. al. n. v i n C hto mid. The three entering Lower Rising [13] starts from low e n g c h i U tones are not included in the tone acquisition studies below.. 25.

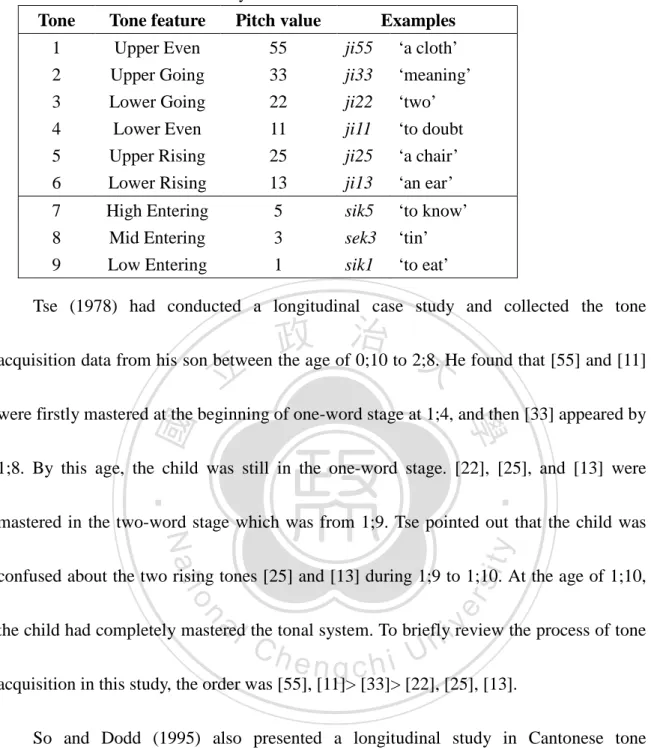

(39) Table 2.12 Cantonese tonal system Tone. Tone feature. Pitch value. Examples. 1 2 3 4 5 6. Upper Even Upper Going Lower Going Lower Even Upper Rising Lower Rising. 55 33 22 11 25 13. ji55 ji33 ji22 ji11 ji25 ji13. ‘a cloth’ ‘meaning’ ‘two’ ‘to doubt ‘a chair’ ‘an ear’. 7 8 9. High Entering Mid Entering Low Entering. 5 3 1. sik5 sek3 sik1. ‘to know’ ‘tin’ ‘to eat’. Tse (1978) had conducted a longitudinal case study and collected the tone. 治 政 大He found that [55] and [11] acquisition data from his son between the age of 0;10 to 2;8. 立 ‧ 國. 學. were firstly mastered at the beginning of one-word stage at 1;4, and then [33] appeared by 1;8. By this age, the child was still in the one-word stage. [22], [25], and [13] were. ‧. mastered in the two-word stage which was from 1;9. Tse pointed out that the child was. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. confused about the two rising tones [25] and [13] during 1;9 to 1;10. At the age of 1;10,. i n U. v. the child had completely mastered the tonal system. To briefly review the process of tone. Ch. engchi. acquisition in this study, the order was [55], [11]> [33]> [22], [25], [13]. So and Dodd (1995) also presented a longitudinal study in Cantonese tone acquisition by observing four children from 1;2 to 2;0. The results showed some discrepancies comparing to Tse‘s (1978) study. The data showed that the first mastered tones were [55] and [33] at 1;4, and the [25] appeared second at 1;6. The four children’s orderings remained the same before this age. After 1;8, individual differences were found. Two children acquired the Lower Going tone [22] first, one acquired [11] and [13] first, 26.

(40) and the other one had not acquired any additional tones by the age of 1;10. At the age of 2;0, it is reported that all the four children had mastered the six tones in Cantonese. Because there were individual differences in this study, the conclusion could only be made in the following order: [55], [33]> [25]> [11], [13], [22]. 2.4.3 Taiwanese Taiwanese is a dialect of Southern Min Chinese spoken in Taiwan. There are seven. 政 治 大. lexical tones in this language, but each of it has two tone values. When syllables are in the. 立. “juncture positions,” they are pronounced in the original tones; when they appear in the. ‧ 國. 學. “context positions,” the tone sandhi rule would be applied and they would be pronounced. ‧. in different tones. There are three level tones with different pitch height, which are High,. Nat. io. sit. y. Mid, and Low tones. The contour tones are the High Falling tone and the Low Rising tone.. er. The last two short tones are ‘Rusheng’ tones and were not discussed in the following tone. al. n. v i n C inh both juncture andUcontext positions are shown below acquisition study. The tone values engchi in Table 2.13.. 27.

(41) Table 2.13 Taiwanese tonal system Juncture Tone feature Pitch value. Examples. 1 2 3 4 5. High Level Low Rising High Falling Low Level Mid Level. 55 13 53 11 33. si55 si13 si53 si11 si33. ‘a poem’ ‘time’ ‘death’ ‘four’ ‘a temple’. 6. Mid Ru. 3. sik3. ‘color’. 7. High Ru. 5. sik5. ripe. Tone. Context Tone feature. Pitch value. Mid level Mid level High level High falling Low level. 33 33 55 53 11. High ru/ High falling Low ru/ Low level. 5/53 1/11. 政 治 大. Tsay (2001) had conducted a longitudinal and big-scale research to observe a total of. 立. fourteen Taiwanese-speaking children aged 1;2 to 3;11 in southern Taiwan. The big-scale. ‧ 國. 學. observation persisted for three years and recorded a total of 330 hours data. In the tonal. ‧. acquisition analysis, Tsay focused on seven children (3 girls and 4 boys) aged 2;1 to 2;3. y. Nat. er. io. sit. whose MLU were longer than two words and could produce utterances longer enough to apply tone sandhi in context position. The seven children’s average error rates in each. n. al. Ch. tone were calculated in the following.. engchi. i n U. v. Table 2.14 The average error rate of each tone in juncture position Tone Error rate. [55] 4%. [53] 6%. [33] 6%. [13] 8%. [11] 18%. In Table 2.14, it indicated that the errors on [55] tone were the fewest. The errors on [55] accounted for 4% of the total error tokens. The error rates on [53] and [33] were also few, accounting for 6 % respectively. There were 8% of errors on [13], and the most unstable tone was [11]. From the tone error rates in juncture position, Tsay pointed out that tones 28.

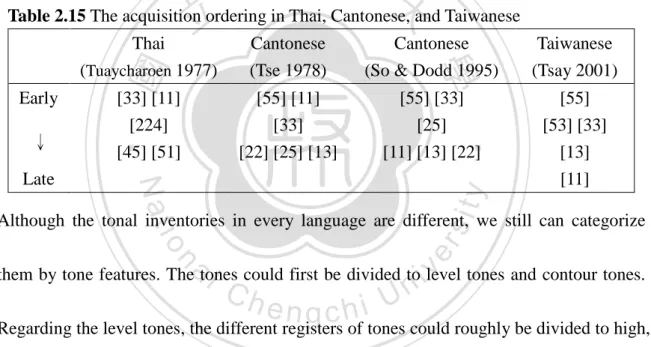

(42) in high pitch such as [55] and [53] acquired more stable than those in low pitch, including [13] and [11]. In addition, the results also showed that the falling tone [53] had fewer errors than the rising tone [13]. To sum up, the tone acquisition order in Taiwanese children was [55]> [53], [33]> [13]> [11]. 2.4.4 Overview of the cross-linguistic studies After reviewing the three tonal systems in East Asia and the relevant tone acquisition. 政 治 大 Table 2.15 The acquisition ordering in Thai, Cantonese, and Taiwanese 立 Cantonese Thai Cantonese (Tse 1978). (So & Dodd 1995). [33] [11] [224] [45] [51]. [55] [11] [33] [22] [25] [13]. [55] [33] [25] [11] [13] [22]. Taiwanese (Tsay 2001) [55] [53] [33] [13] [11]. sit. y. Nat. Late. (Tuaycharoen 1977). ‧. ↓. 學. Early. ‧ 國. studies above, we would like to compare the acquisition ordering cross-linguistically.. io. n. al. er. Although the tonal inventories in every language are different, we still can categorize. i n U. v. them by tone features. The tones could first be divided to level tones and contour tones.. Ch. engchi. Regarding the level tones, the different registers of tones could roughly be divided to high, mid, and low tones. Lin (2007) defined that the digit number of 5 and 4 in pitch value were high tones, 3 was mid, and 2 and 1 were low tones. With regard to contour tones, there are mainly two types which are falling and rising tone. Tones that end at a higher pitch than the starting pitch are considered rising tones; tones which end at a lower pitch than the starting pitch are viewed as falling tones. From the cross-linguistic studies above, the common ground was that the level tones 29.

(43) were acquired earlier than contour tones among all studies. The earliest acquired tones in these three languages, including the [33] and [11] in Thai, the [55], [33] and [11] in Cantonese, and the [55] in Taiwanese, were all level tones. There was also language-specific phenomenon. It seemed that falling tones were mastered earlier than rising tones in Taiwanese, but Thai had the opposite ordering. In Taiwanese, the falling tone [53] was produced more stable than the rising tone [13], but in Thai, the rising tone. 政 治 大. [224] seemed to be acquired earlier than the falling tone [51]. Regarding the ordering of. 立. level tones in different registers, the high-level tones tended to be acquired earlier than. ‧ 國. 學. low-level tones. In Taiwanese, the orders showed sequential ranking from high-level. ‧. tones to low-level tones that the [55] tone was acquired earlier than [33], and [33] was. Nat. io. sit. y. followed by [11]. Also, the Cantonese study conducted by So and Dodd (1995) found that. er. [55] and [33] were acquired earlier than [22] and [11]. However, the Cantonese study. al. n. v i n C h[55] and [11] wereUacquired at the time same, [33] presented by Tse (1978) indicated that engchi was acquired later, and [22] the last. The sequence of high tones and low tones also. showed variations in Thai. Tuaycharoen (1977) suggested that [33] and [11] were acquired earlier than [45], which was the only HH tone in Thai. To sum up, level tones were acquired earlier than contour tones universally; falling tones were acquired more stable than rising tones cross-linguistically except for Thai; high-level tones seemed to acquired the earliest except for Thai, but it was uncertain whether the mid tones were 30.

(44) acquired earlier than low tones. 2.5 Tone acquisition in Mandarin 2.5.1 Chao (1951) When observing the process of tone acquisition, early studies were focusing on the age and ordering of the development of tones. A pioneering observation on Mandarin tone acquisition was resented by Chao (1951) who collected speech data from his. 政 治 大. 28-month-old grand-daughter. Chao found that his grand-daughter could have already. 立. distinguished the rising tone [35] and the low-falling tone [214], and could produce tones. ‧ 國. 學. correctly in isolated words. Though she could distinguish the rising tone [35] and the. ‧. low-falling tone [214], Chao noticed that she tended to replace the low-falling tone [214]. Nat. io. sit. y. with the rising tone [35]. However, Chao’s description was based on only one child, and. er. he did not exactly present the whole picture of tone acquisition in this study, the value of. al. n. v i n the results may be limit to a firstCglance in the tone acquisition field in Mandarin Chinese. hen gchi U 2.5.2 Li & Thompson (1977). After Chao’s (1951) contribution in Mandarin tone acquisition, Li and Thompson (1977) conducted a larger and systematic research focusing on Mandarin speaking children in Taiwan. They use four stages to sketch the tone acquisition process: Stage I: The child’s vocabulary is small. High and falling tones predominate irrespective of the tone of the adult form. 31.

(45) Stage II: The child is still at the one-word stage, but he has a larger vocabulary. The correct 4-way adult tone contrast has appeared, but sometimes there is confusion between rising and dipping tone words. Stage III: The child is at the 2/3-word stage. Some rising and dipping tone errors remain. TS is beginning to be acquired. Stage IV: Longer sentences are being produced. Rising and dipping tone errors are practically non-existent.. 立. 政 治 大. The four divided stages on tonal development presented the chronological ordering and. ‧ 國. 學. the corresponding word length children uttered. The important findings in Li and. ‧. Thompson (1977) were that the high-level tone [55] was the first acquired tone, and then. Nat. io. sit. y. the high-falling tone [51] was the second. The rising tone [35] and the low-falling-rising. er. tone [214] were acquired the last. By the stages when children have not mastered all tones. al. n. v i n C h persisted throughout yet, the switch between [35] and [214] e n g c h i U stage II and stage III. This. report provided a more complete understanding of the age and ordering in Mandarin tone acquisition. They also provided two children’s substitution strategies in tonal errors. One child replaced all [35] and [214] with [55] and [51], and the other child had constant substitution between [35] and [214]. Although Li and Thompson did the first systematic tone acquisition study in Taiwan Mandarin and sketched the stages of development, the number of utterances or error rates of tones were not documented specifically, so the 32.

(46) degree of development in the process of tone acquisition was not documented. 2.5.3 Zhu (2002) A more recent work related to the tone acquisition in Mandarin set more specific criterion on stabilization of the acquired tones. Zhu (2002) conducted a longitudinal study in Beijing on four Mandarin-speaking children aged 0;10 to 1;2 in the beginning and 1;8 to 2;0 at the end. She provided the age of tone emergence and age of stabilization in each. 政 治 大. subject. The order of tone emergence was similar to that in tone stabilization. The. 立. criterion for deciding the tone emergence and stabilization was clearly cited in this study,. ‧ 國. 學. and the tonal error patterns were presented in specific number of frequencies. The results. ‧. showed that the high-level tone [55] was firstly emerged and stabilized. The second one. Nat. io. sit. y. was the falling tone [51], and rising [35] and falling-rising tones [214] were the last.. er. When tonal errors occurred, the most frequent tone that realized to replace the error was. al. n. v i n C htone seemed to beUreplaced by the falling tone when the high-level tone, and high-level engchi produced wrongly. However, the subjects Zhu studied were from Beijing, and the Mandarin was different from that in Taiwan. It is valuable to see whether the development of tones would be different in children exposed to dialects in Taiwan. 2.5.4 Summary Based on the three studies reviewed above, researchers agreed that the high-level [55] and falling [51] acquired earlier than the falling-rising [214] and the rising tone [35]. But 33.

(47) the substitution pattern for whether [35] was easier to replace [214] or vice versa did not gain consensus. There was also no precise document describing the tonal acquisition process in developmental stages. Thus, the topic is worth for further research.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 34. i n U. v.

(48) Chapter 3 Methodology The methodology would include two parts: one is the data collection, and the other is the data analysis. The data were collected by the author and the research team in the. 政 治 大. Phonetics and Psycholinguistics Lab at National Chengchi University under the NSC. 立. project, “Consonant Acquisition in Taiwan Mandarin,” investigated by Professor Wan. ‧ 國. 學. I-Ping (NSC 100-2410-H-004-187-).. ‧. For data collection in section 3.1, I will introduce how I recruited the participated. Nat. io. sit. y. families in 3.1.1, what my subjects’ backgrounds were in 3.1.2, how the observation. er. proceeded in 3.1.3, and what recording equipments were used in 3.1.4. For the data. al. n. v i n C h how I transcribed analysis in section 3.2, I will illustrate e n g c h i U the data in 3.2.1. From 3.2.2 to. 3.2.4, I will show how I arranged the data in order to obtain the result of the tone emergence ordering, frequency, accuracy rate, and the substitution pattern in tonal errors. 3.1 Data collection This section contains the process of recruitment in 3.1.1, the background information of the informants in 3.1.2, the observational procedures in 3.1.3, and the recording equipments in 3.1.4. 35.

(49) 3.1.1 Recruitment The participated families were recruited through an advertisement on a popular parent forum called Babyhome (http://www.babyhome.com.tw/), on the behalf of the NSC project investigated by Professor Wan I-Ping (NSC 100-2410-H-004-187-). In the non-profit advertisement forum, an article was pasted to declare the academic research purpose, and to ask for recruiting children aged from 0;8 to 1;0 who was at the beginning. 政 治 大. stage of their language development. Parents who wanted to join the research could sign. 立. up by filling out the online registration form designed by the “Google doc spread sheet,”. ‧ 國. 學. which could be customized by users. There were totally 16 families enrolled in the NSC. ‧. project, but only 6 children fit in this study.. io. sit. y. Nat. 3.1.2 Subject. er. The six children were all from middle class families in Taipei City or New Taipei. al. n. v i n C h that the children City. These families were all core families e n g c h i U only lived with their parents, and the informants were all taken cared by their mothers for the whole day. All Mothers used Mandarin Chinese to communicate with their children, so these children’s first language was determined to be Mandarin. Among the 6 subjects, three of them were males and three were females. From the beginning of the observation, their ages were between 0;10 to 1;1 (mean age= 0;11.67, SD= 0.8 months). The observation continued for eight months. At the end of the 36.

數據

相關文件

The first row shows the eyespot with white inner ring, black middle ring, and yellow outer ring in Bicyclus anynana.. The second row provides the eyespot with black inner ring

11[] If a and b are fixed numbers, find parametric equations for the curve that consists of all possible positions of the point P in the figure, using the angle (J as the

2.28 With the full implementation of the all-graduate teaching force policy, all teachers, including those in the basic rank, could have opportunities to take

Robinson Crusoe is an Englishman from the 1) t_______ of York in the seventeenth century, the youngest son of a merchant of German origin. This trip is financially successful,

fostering independent application of reading strategies Strategy 7: Provide opportunities for students to track, reflect on, and share their learning progress (destination). •

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

If the students are very bright and if the teachers want to help prepare these students for the English medium in 81, teachers can find out from the 81 curriculum

According to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, if the observed region has size L, an estimate of an individual Fourier mode with wavevector q will be a weighted average of

![Table 2.14 The average error rate of each tone in juncture position Tone [55] [53] [33] [13] [11]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/8306357.174334/41.892.99.794.123.917/table-average-error-rate-tone-juncture-position-tone.webp)