Original Article

Terminal Cancer Patients’ Wishes

and Influencing Factors Toward

the Provision of Artificial Nutrition

and Hydration in Taiwan

Tai-Yuan Chiu, MD, MHSci, Wen-Yu Hu, RN, MSN, Rong-Bin Chuang, MD, MPH, Yih-Ru Cheng, MS, Ching-Yu Chen, MD, and Susumu Wakai, MD, PhD Departments of Family Medicine (T.-Y.C., Y.-R.C., C.-Y.C.) and Social Medicine (T.-Y.C.), and School of Nursing (W.-Y. H.), College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University; and Department of Family Medicine (R.-B.C.), Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, and Department of International Community Health (T.-Y.C., S.W.), Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

Abstract

Identifying the concerns of terminal cancer patients and respecting their wishes is important in clinical decision-making concerning the provision of artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH). The aim of this study was to discover terminal cancer patients’ wishes and determine influencing factors toward the provision of ANH. One hundred and ninety-seven patients with terminal cancer, admitted to a palliative care unit in Taiwan over a two-year period, completed a questionnaire interview, which included demographic characteristics, knowledge and attitudes on ANH, the health locus of control, subjective norms, and the wishes to use ANH. One hundred and fifty-four patients (78.2%) used ANH in the past month. A knowledge test on issues related to ANH showed the rates of accurate responses were ranked as: peripheral intravenous route can only provide hydration (48.7%), excessive artificial nutrition may increase the proliferation of cancer cells (32%), ANH can prolong life expectancy for all patients (17.3%), and ANH can prevent all patients from starving to death (5.6%). The strongest attitude of patients toward the potential benefit of ANH was “it can provide the body need with nutrition and hydration when inability to eat or drink occurs.” Otherwise, the strongest attitude toward the potential burdens of ANH was “gastrostomy makes the illness worse.” One hundred and twenty-two of 197 patients (62.9%) expressed their wishes to have ANH. The results of logistic regression analysis showed that the experience of using a nasogastric tube and intravenous fluids, and subjective norms were the most significant variables related to the wishes of patients to use ANH (odds ratio [OR]⫽ 11.11, 95% confidence interval [CI] ⫽ 3.20–38.64;

OR⫽ 2.51, 95% CI ⫽ 1.22–5.15, OR ⫽ 1.30, 95% CI ⫽ 1.05–-1.60, respectively). However, the use of artificial nutrition was negatively affected by the knowledge of ANH (OR⫽ 0.53, 95% CI ⫽ 0.37–0.84). In conclusion, Taiwanese patients with terminal cancer have insufficient knowledge about AHN and still believe in the benefits of ANH,

Address reprint requests to: Tai-Yuan Chiu, MD, No. 7, Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan

Accepted for publication: July 6, 2003.

쑖2004 U.S. Cancer Pain Relief Committee 0885-3924/04/$–see front matter

especially in avoiding dehydration or starvation. The findings of this study indicate the importance of medical professional training and decision-making in the initial

consideration of using ANH. By improving the knowledge about ANH among patients, more appropriate decisions can be achieved. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;27:206–214.

쑖

2004 U.S. Cancer Pain Relief Committee. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Key WordsWishes, nutrition, hydration, terminal cancer

Introduction

Decisions about the provision of artificial nu-trition and hydration (ANH) in the final days of a patient’s life should consider not only the physiological aspects and physical value of nu-trition and hydration, but also the symbolic nature and cultural significances of food and fluids. Clinical ethics in the decision to use ANH require the respect for both the needs of a patient’s body and the choice of the patient’s mind, especially the informed decision of the patient.1

Previous studies have suggested that excessive supply with fluid and nutrition may increase body loading and result in discomfort for the terminal patient.1–5 Otherwise, aggressive nu-tritional therapy has no benefit on tumor re-sponse or survival.6,7 Moreover, aggressive nutritional therapy was reported in an animal study to significantly increase tumor growth.8 Unfortunately, there is also currently no evi-dence that suggests that aggressive nutrition therapy can improve the quality of life, which is recognized to be the most important outcome for terminal patients.9–12However, psychologi-cal distress may result if deterioration in cog-nition prevents a patient from expressing his or her wishes. Some studies suggested that dehy-dration may contribute to an agitated delirium or terminal restlessness that could be eased by gentle hydration.1,10

Several articles have also emphasized the im-portance of the symbolic nature of food in rela-tion to the provision of nutrirela-tion and hydrarela-tion in terminal illness.13 According to Scanlon et al., food has symbolic meaning that transcends the physical benefits it provides.14Beauchamp et al. observed that denying food and water to anyone for any reason seems the antithesis of expressing care and compassion.15Meilaender stresses that food and drink are the sort of care

that all human beings owe to each other.16 Oth-erwise, Green highlights “what could be any more inextricably bound to life itself than offer-ing hungry persons food and thirsty persons water?”17Connelly notes that survival itself may depend on the cultivation of basic emotions that is reinforced by giving food and drink to those in need.18

Besides the symbolic nature of food, some influencing factors such as demographics, prior experiences in using ANH, and the knowledge and attitudes toward ANH may influence the use of nutrition and hydration in terminal ill-ness and are worthy of exploration.19–21 In Taiwan, the decision to use or forego artificial nutrition and hydration remains a perplexing and emotional issue in the care of terminal cancer patients. A previous study in Taiwan showed that about one-quarter of palliative care patients has encountered the ethical conflicts of using nutrition and hydration during hospi-talization.22 To provide better education and communication for appropriate support for nu-trition and hydration, exploring the relating factors toward the wishes of using ANH in these terminally ill patients will be valuable. The aims of this study were to discover the wishes of termi-nal cancer patients and determine the influenc-ing factors toward the use of ANH.

Methods

Patients

All consecutive cancer patients, admitted to the hospice and palliative care unit of the Na-tional Taiwan University Hospital between August 2000 and July 2002, were enrolled in the study. Patients whose cancers were not respon-sive to curative treatment were identified in an initial assessment performed by members of the admissions committee. Eligibility criteria

for the patients in this study were: (1) the patient was not severely cognitively impaired and can communicate, (2) the patient gave in-formed consent or verbally agreed to partici-pate, and (3) the patient was well enough to be interviewed. The patients’ physicians and the primary nurses determined eligibility. Pa-tients chose whether to complete the question-naires without assistance or by having the questions read aloud by the interviewers or caregivers. The selection of patients and the design of this study were approved both by the National Science Council in Taiwan and the ethics committee of the hospital. By the end of the study period, 197 patients had completed the questionnaire interviews.

Measurement

A structured questionnaire consisting of six parts was used for the interview of all of the subjects. The six parts of the questionnaire in-cluded questions on demographic characteris-tics, knowledge and attitudes on ANH, the health locus of control, subjective norms, and the wishes to use ANH. The entire six-part ques-tionnaire was tested for content validity by a panel composed of two physicians, two nurses, one dietitian, one psychologist, and one social worker, all of whom were experienced in the care of the terminally ill. Each item in the ques-tionnaire was appraised from “very inappropri-ate and not relevant (1)” to “very appropriinappropri-ate and relevant (5).” A “content validity index” (CVI) was used to determine the validity of the structured questionnaire and yielded a CVI of 0.930. In addition, 10 patients filled out the questionnaire to confirm the questionnaire’s face validity and ease of application.

Demographic characteristics assessed by the questionnaire included gender, age, education, primary tumor sites, and experiences in the use of ANH (including hydration, nutrition, naso-gastric (NG) tube, and gastrostomy). The other five parts included:

1. Knowledge of ANH. This measure assessed the knowledge about the use of ANH (9 items). This 9-item measure was designed with careful scrutiny of the literature in this area. All of the items were also grounded on the basis of real life experi-ences of the investigators involved in pal-liative care. The scoring system of this

scale was “true (1)” and “false/unknown (0).” A Kuder-Richardson formula 20 (KR-20) was used to assess internal consistency of this knowledge measure and showed a coefficient of 0.71 for the final 7 items. 2. Attitude (belief and evaluation) about ANH.

Designed with careful scrutiny of the avail-able literature, this part included the per-ception of the threats, the benefits, and the barriers in the provision of ANH. The measure was 19 items using 5-point Likert scales – from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (5).” Bartlett’s test (BT) of sphericity and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test were used to determine whether belief data were suitable for exploratory factor analysis. In this measure, the value of the BT was 852.94, significant value was 0.00, and the KMO value was 0.708. Therefore, the measure was suitable for exploratory factor analysis. The draft items were ana-lyzed using principal component factor analysis followed by orthogonal varimax rotation. The number of principal compo-nents to be extracted was determined by examining the eigenvalues (⬎1) and Cat-tell’s Scree test. Meanwhile, the cut point of factor loading was set at 0.3. Items with low factor loading (⬍0.3) were deleted from each subscale. Finally, the beliefs measure was constructed using the benefits and bur-dens, perceived from the terminal patients in using ANH, after deleting two items. In-ternal consistency was demonstrated, with the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient range of 0.69 to 0.78, in the subscales of beliefs. The importance of each item was also evaluated by the patients.

3. Health Locus of Control. This measure re-ferred to the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control scale (MHLC) original-ly designed by Wallston and Devellis in 1978.23This has been used in Taiwan in the past23,24,25and modified in this study based on care experiences. It is an 18-item measure using a Likert scale, from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (6).” Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test were used to determine whether the study data of the health locus of control were suitable for exploratory factor analysis. The value of

the BT for the data was 952.19, significant value was 0.00, and the KMO value was 0.711. Therefore, the scale was also suit-able for exploratory factor analysis. The same procedure of exploratory factor analysis used in the belief on ANH was used. Finally, six items were deleted and the sub-domains were reconstructed to two factors and named “Chance external” and “Internal and powerful others” health locus of control factors. The internal consistency was demonstrated with Cron-bach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.68 to 0.81 in the subscales of this measure. 4. Subjective Norms. This part is composed of

both “perceived beliefs of significant others’ opinions” and “the motivation to comply with significant others’ opinions” to use ANH. The measure has 7 items, including the influences by physicians, nurses, spouses, sons, daughters, friends, or others, on a 5-point Likert scale: from “strongly unaffected (1)” to “strongly af-fected (5).”

5. Wishes. This identified the terminal pa-tients’ wishes for using ANH, including the use of intravenous hydration and nutrition (including electrolytes).

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using the SPSS 11.0 statistical software. A frequency distribution was used to describe the demographic data and the distribution of each variable. Mean values and standard deviations were used to analyze the degree of each variable in the knowledge of ANH, beliefs and evaluations on the use of ANH, health locus of control, and subjective norm measures. Each item of the above measures was entered into the model as independent variables and the wishes to use ANH as the dependent variable. Univariate analysis was per-formed between the wishes and possible wish-related variables by Chi-square test, one-way ANOVA, Scheffe’s test, independent sample t-test, and Pearson correlation coefficient. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered signifi-cant. Afterward, backward stepwise logistic re-gression analysis was carried out to determine the relative values of the variables related to

the wishes. Calibration of the models was as-sessed using the Hosmer and Lemeshow Good-ness-of-Fit test. It evaluated the degree of correspondence between the probabilities of wishes and the actual wishes.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

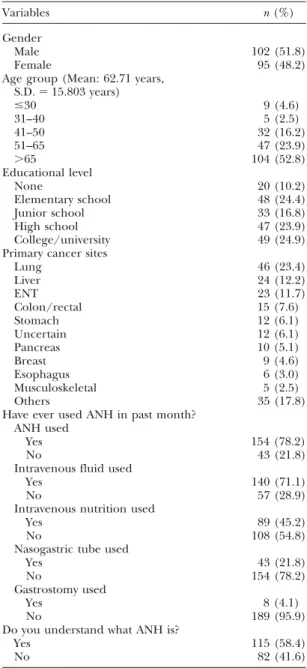

Table 1shows the demographic characteris-tics of the 197 patients. Patients were mainly

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics (n⫽ 197) Variables n (%) Gender Male 102 (51.8) Female 95 (48.2)

Age group (Mean: 62.71 years, S.D.⫽ 15.803 years) ⱕ30 9 (4.6) 31–40 5 (2.5) 41–50 32 (16.2) 51–65 47 (23.9) ⬎65 104 (52.8) Educational level None 20 (10.2) Elementary school 48 (24.4) Junior school 33 (16.8) High school 47 (23.9) College/university 49 (24.9)

Primary cancer sites

Lung 46 (23.4) Liver 24 (12.2) ENT 23 (11.7) Colon/rectal 15 (7.6) Stomach 12 (6.1) Uncertain 12 (6.1) Pancreas 10 (5.1) Breast 9 (4.6) Esophagus 6 (3.0) Musculoskeletal 5 (2.5) Others 35 (17.8)

Have ever used ANH in past month? ANH used

Yes 154 (78.2)

No 43 (21.8)

Intravenous fluid used

Yes 140 (71.1)

No 57 (28.9)

Intravenous nutrition used

Yes 89 (45.2)

No 108 (54.8)

Nasogastric tube used

Yes 43 (21.8)

No 154 (78.2)

Gastrostomy used

Yes 8 (4.1)

No 189 (95.9)

Do you understand what ANH is?

Yes 115 (58.4)

above 65 years old (52.8%) with a mean age of 62.7 years (SD⫽ ⫹15.8 years). The formal education of half of the respondents was junior high school or below (51.4%). The primary sites of cancer in the patients were lung (23.4%), liver (12.2%), head/neck (11.7%), and colo-rectal (7.6%). More than three quarters of the patients (78.2%) used ANH in the past month. With regard to the details of ANH used, the percentages of using intravenous hydration, in-travenous nutrition, nasogastric tube, and gas-trostomy were 71.1%, 45.5%, 21.8%, and 4.1%, respectively. Meanwhile, 115 of the 197 patients (58.4%) said they understood what ANH is.

Knowledge of ANH

With regard to ANH knowledge, the mean percentage of accurate responses was only 24.4%. The accurate answers to the knowledge of ANH was ranked as “peripheral intrave-nous fluids can only provide hydration” (48.7%), “excessive artificial nutrition may increase the proliferation of cancer cells” (32.0%), “ANH symbolizes the care of families” (26.4%), “ANH will be helpful to all patients in any dis-ease stage” (24.9%), “ANH can prolong life ex-pectancy” (17.2%), “ANH can increase physical strength for all patients” (16.3%), and “ANH can prevent all patients from starving to death” (5.6%) (Table 2).

Variables Related to the Wish to Use ANH

Table 3shows that the possible factors related to one’s wishes include beliefs on ANH, the health locus of control, and the prevailing sub-jective norms. The mean score of beliefs toward ANH was 2.90 (SD⫽ 0.34, range 1–5). The two sub-concepts of beliefs were: the perception of “benefit” of using ANH and “burdens” of using ANH. Their mean scores were 3.81 and 2.38,

Table 2

Knowledge of Artificial Nutrition and Hydration (n⫽ 197)

Variables Correct response n (%) Wrong response n (%) Not clear n (%)

Peripheral intravenous route can only provide hydration 96 (48.7) 14 (7.1) 87 (44.2)

Excessive ANH may increase 63 (32.0) 29 (14.7) 105 (53.3)

the proliferation of cancer cells

ANH symbolizes the care of families 52 (26.4) 120 (60.9) 5 (12.7)

ANH is helpful to all patients at any stage of disease 49 (24.9) 117 (59.4) 31 (15.7)

ANH can prolong life for all patients 34 (17.2) 130 (66.0) 33 (16.8)

ANH can increase physical strength for all patients 32 (16.3) 136 (69.0) 29 (14.7)

ANH can prevent all patients from starving to death 11 (5.6) 175 (88.8) 11 (5.6)

respectively. These indicate positive beliefs to-wards using ANH. The items with high scores in terms of perceived benefits about ANH include: “ANH can meet the body’s needs for nutrition and fluid, when the inability to eat or drink occurs” (4.17), “need to use ANH when vom-iting or anorexic” (4.15), “able to prevent dehy-dration” (4.09), and “able to increase physical strength” (3.64). Concerning the importance evaluated by patients, “ANH can meet the body’s needs of nutrition and fluid, when inabil-ity to eat or drink occurs” (4.04) is recognized to be the most important benefit.

The items with high scores in terms of the perceived burdens about using ANH are: “gas-trostomy will make the illness worse” (2.73), “make blood vessels harder” (2.49), “unneces-sary to use ANH if it is not helpful in the control of illness” (2.49), and “using NG tube to make a bad image” (2.47). Concerning the importance evaluated by patients, “unnecessary to use ANH if it is not helpful in the control of illness” (3.66) and “NG tube makes me uncomfortable” (3.64) were the two important concerns that burden patients.

The mean scores of the two subscales of Health Locus of Control, “Chance external” and “Internal and powerful others” were 2.85 and 3.86, respectively. These indicate that the pa-tients in the study were inclined to believe in overcoming everything either by themselves or by support from the medical staff and their families.

Subjective norms to the use of ANH came from the influences of the terminal cancer pa-tients’ significant others. The physician and nurse was the most often cited “significant other” (mean 3.70 and 3.66, respectively). The total mean of subjective norms was 3.62 (range 1–5), which shows that the terminal pa-tients were moderately influenced by subjective norms, especially from the medical staff.

Table 3

Variables Related to Wishes of Terminal Cancer Patients to Use ANH (n⫽ 197)

Variables Mean (⫾SD) Range

Beliefs: perception of using ANH 2.90⫾ 0.34 1–5 Factor I: perception of benefit 3.81⫾ 0.52 1–5 Factor II: perception of threats 2.38⫾ 0.45 1–5 Health locus of control 3.35⫾ 0.46 1–6 Factor I: chance external 2.85⫾ 0.63 1–6

Factor II: internal 3.86⫾ 0.56 1–6

and powerful others

Subjective norms 3.62⫾ 0.81 1–5

for the use of ANH

Knowledge of ANH 0.27⫾ 0.19 0–1

The Wish and Its Important Influencing

Factors Toward the Use of ANH

More than sixty percent (62.9%) of terminal cancer patients expressed their wishes to use ANH, leaving 23.9% and 13.2% in the unwished and unclear groups, respectively (Table 4). The majority of those belonging to these unwished and unclear groups were willing to receive hydration and nutrition (75.8% and 91.1%, respectively).

The results of stepwise logistic regression analysis inTable 5reveal that, when other vari-ables remain unchanged, the higher the score for “have ever used NG tube and IV fluids in recent one month” and “subjective norms,” the higher the probability of wishing to receive ANH (OR⫽ 11.11, 95% CI ⫽ 3.20–38.64, P ⬍ 0.001; OR⫽ 2.51, 95% CI ⫽ 1.22–5.15, P ⬍ 0.05; OR⫽ 1.30, 95% CI ⫽ 1.05–1.60, P ⬍ 0.05), re-spectively. For the fitness of the model, the P-value of the Hosmer and Lemeshow Good-ness-of-Fit test was 0.303. However, regarding

Table 4

Subjective Wishes to Use ANH (n⫽ 197)

Wishes to use ANH % (n)

Yes 62.9 (124)

No 23.9 (47)

Unclear 13.2 (26)

Details of ANH wish to use (n⫽ 124) Hydration Yes 75.8 (94) No 24.2 (30) Nutrition Yes 91.1 (113) No 8.9 (11) Electrolyte Yes 37.9 (47) No 62.1 (77)

the sub-models, the wish for using artificial nu-trition (including electrolyte) was negatively af-fected by the knowledge of ANH (OR⫽ 0.53, 95% CI⫽ 0.37–0.84, P ⬍ 0.01). For the fitness of the model, the P-value of the Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test was 0.990. These findings indicate that, when other variables remain unchanged, the higher the score for “the knowledge of ANH,” the lower the proba-bility of wishing to receive artificial nutrition. Otherwise, concerning the wish for using artifi-cial hydration, it is not suitable to perform step-wise logistic regression analysis because only one variable has a significant difference in the uni-variate analysis.

Discussion

Patient autonomy should be respected and this has been emphasized in hospice and pallia-tive care. Autonomy requires the respect for the patient’s right to self-determination that will allow each to judge what is best, weighing the benefits and harm, in the patient’s own case.26 However, there have been relatively few stud-ies that deal with the concerns of terminal pa-tients, and this is the first one to investigate the issues regarding ANH from the patient’s per-spective. This study not only identified the terminal cancer patients’ wishes to use ANH, but also determined the influencing factors in their wishes. Thus, the results of the study would be helpful in providing efficient education and communication among patients, families, and medical professionals for reaching a more appropriate decision.

It is interesting in the study that although 154 study patients (78.2%) used ANH in the past month, only 115 of these (58.4%) said they understand what ANH is. These results indi-cate an ethical concern. Despite medical staff endeavors to provide adequate nutrition or hy-dration in the principle of beneficence, inap-propriate hydration and nutrition may further increase the terminal patient’s distress, vio-lating the principle of non-maleficence. With regard to foregoing or giving assisted nutrition and hydration, it will be a moral responsibility to explain the causes of impairment to eating or drinking and the potential benefits and bur-dens in the use of ANH to the patients and to their families, although some evidence of these

Table 5

Models for Significant Influencing Variables Toward the Wish to Use ANH and Artificial Nutrition by Logistic Regression Analysis

Use of ANH Wishes/No wish

Significant variables β S.E. OR 95% CI of OR P-value

Have ever used NG tube in past month 2.408 0.636 11.114 (3.196–38.646) 0.000

Have ever used IV fluids in past month 0.919 0.367 2.507 (1.221–5.148) 0.012

Subjective norms 0.262 0.107 1.300 (1.054–1.603) 0.014

Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test P-value 0.303

Use of artificial nutrition Wishes/No wish

Significant variable β S.E. OR 95% CI of OR P-value

Knowledge of ANH ⫺0.642 0.229 0.526 (0.336–0.842) 0.005

Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test P-value 0.990

benefits or burdens remains inconclusive. Moreover, legally, ANH has been recognized as a medical treatment, which can be refused by a competent adult or a surrogate decision-maker appointed through an advance directive in the principle of autonomy.11

As to the knowledge of ANH, the low per-centage of accurate responses indicates that knowledge about AHN is insufficient among terminal cancer patients. This is also believed to occur commonly in medical professionals.27,28 “ANH can prolong life for all patients,” “ANH can increase physical strength for all pa-tients,” and “to prevent all patients from starv-ing to death” are the items with the lowest percentage of accurate answers, which corre-spond with the local cultural significance. Diffi-culty in eating or drinking often leads to anxiety in the patient’s loved ones, who worry that the terminal patient will starve to death, becoming a “starving soul” after death. Such concerns in Taiwan drive families to requests for food or fluids that might cause greater discomfort for patients and make necessary their stay in the hospital rather than at home.7

Some studies also show the use ANH has no significant influence on survival, which could be explained with reference to the “terminal common pathway” in cancer patients and which may validate the ethical nature of withholding ANH.6,7The ethical training of medical profes-sionals and the process of communication with patients or families should re-focus on empha-sizing the fact that the inability to eat or drink in terminal cancer patients is always due to the natural course of the disease and the outcome of death will be due to the deterioration of sys-temic organs rather than starvation. Otherwise,

only 63 patients (32.0%) recognized that exces-sive ANH might increase the proliferation of cancer cells, which is also an important edu-cational need for better communication and decision-making.

In our clinical practice, continuing explana-tion of the reasons for foregoing ANH could often be accepted by families. However if con-flicts arise, when people disagree about whether to withhold or withdraw ANH, a defined thera-peutic trial of ANH for a set period of time (two or three days) is used. We encourage family and caregivers together to observe for the desired change. If the goals are not met by the end of the therapeutic trial, ANH can be stopped. This solution process is similar to the guidelines pro-posed by Jenkins and Bruera.29 Furthermore, since the majority of Taiwanese are Buddhists, they usually believe that a “good death” can only be achieved in a Buddhist care model, especially in the very terminal stage. The staff in the study hospice always gently explained that in Buddhism, excessive nutrition or hydra-tion is inappropriate to enlightenment and in-spiration, both of which are helpful in achieving a better afterlife. Families usually understand and accept this explanation, and it relieves their anxieties to some extent.7 However, it is worthwhile to mention that in Oriental cul-ture, it is actually common practice not to dis-close the truth of illness, especially to a terminal cancer patient, on the basis of non-maleficence. This mutual pretense prevails and increases the barriers of communication with patients about the details of using ANH.21

Approximately three-quarters of study pa-tients recognized that ANH could symbolize the care of families (accurate response rate: 26.4%).

Although this item is somewhat related to atti-tudes, the finding may have some important implications. First, many patients may be able to take more food or water by mouth after im-proved oral hygiene, a change in food type, or assistance with family-patient interaction. Use of ANH too early may replace the family’s delicate care and make the relationship between the patient and family more aloof. Im-proving quality of life by encouraging more interaction between patient and family is an essential part of palliative care. Second, it may imply and aggravate the potential worries of patients of being abandoned by the family.

As to the beliefs concerning NH, patients tended to believe the benefits of ANH (benefit vs. burden: 3.81 vs. 2.38). ANH was believed to be a better method to meet the body’s needs for nutrition and fluid according to the findings of our belief survey. However, they believed ANH can only avoid malnutrition or dehydration, rather than the effects of ANH can improve the control of illness, or increase energy or physical power. Despite that, the worry about becoming a “starving soul” still drives patients and families to request the use of ANH. Concerning the burdens of ANH, patients strongly perceived that “gastrostomy will make illness worse (2.73),” “make blood vessels harder (2.49),” and “unnecessary to use ANH if it is not helpful in the control of illness (2.49).” However, the most important concern evaluated by patients was “unnecessary to use ANH if it is not helpful in the control of illness.” These findings indi-cate that patients will become concerned about burdens, especially if ANH is unhelpful to the improvement of illness. Hence, it is ethically necessary for medical professionals to assess the benefit/burden of ANH and inform patients more correctly, which will be helpful for pa-tients to make an appropriate judgment.

In the study, the experiences of using NG tube and IV fluids, and subjective norms were found to be predicting or explained variables for patients’ wishes of using ANH. Among these variables, the experience of using NG tube was the most powerful predictor, with an odds ratio of 11.11. However, the use of an NG tube was also evaluated to be the important burden by our patients. The reasons of this finding may be related to the actual need due to the disease pat-terns or patients’ demographic characteristics.

In the study, all of the head/neck cancer pa-tients with experience with NG tubes expressed their wishes to use ANH. Furthermore, as a significant variable, the experiences of using ANH may also indicate the importance of initial decision-making in considering the use of ANH. With regard to subjective norm, which is a significant variable for using ANH, medical pro-fessionals, including physicians and nurses, are the most influential persons. This reveals the important role of medical professionals in the process of decision-making for the use of ANH, although the families’ concerns are recog-nized to be the major barriers in deciding the use of ANH in the context of local cultural background.

Further analysis of the use of artificial nutri-tion reveals that the knowledge of ANH, or lack of it, was the significant negative predicting variable for wishing to use artificial nutrition. From an educational point of view, we found that more evidence and good teaching materi-als on ANH might be helpful in promoting the knowledge of patients and further improving communication.

Certain caveats should be mentioned in rela-tion to this study. First, some variables were not included in the study, such as symptom distress, religion, and health insurance. These could be influential. Second, the study was conducted in one unit. Even though these patients in the study hospital came from different areas in Taiwan, the generalizability of the findings is still of concern.

In conclusion, Taiwanese patients with termi-nal cancer have insufficient ANH knowledge even though they still believe in the benefits of ANH, especially to avoid dehydration or to prevent them from starving to death. Past experi-ences in using IV fluids and NG tubes, and the medical staffs’ opinions, were the significant influencing factors in the patients’ wishes con-cerning ANH, implying the importance of the professional training and initial decision-making in the consideration of using ANH. Otherwise, by increasing knowledge about ANH among patients, we can improve commu-nication and make it easier to reach a more appropriate decision in the use of artificial nutrition.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Council in Taiwan (NSC 90-2314-B-002-241). The authors are indebted to the faculty

members of the Department of Family Medi-cine, National Taiwan University Hospital, for their full support in conducting this study. The authors also express their gratitude to Ms. Y.Y. Pan and Ms. Y.P. Pan for their assistance in preparing this manuscript. They especially ac-knowledge Professor W.C. Lee of the National Taiwan University for his highly valuable com-ments on the statistical methods.

References

1. MacDonald N, Fainsinger R. Indications and ethi-cal considerations in the hydration of patients with advanced cancer. In: Bruera E, Higginson I, eds. Cachexia-anorexia syndrome in cancer patients. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

2. Musgrave CF. Terminal dehydration. To give or not to give intravenous fluids? Cancer Nursing 1990; 13:62–66.

3. Zerwekh JV. The dehydration question. Nurs-ing 1983;83:47–51.

4. Schmitz P, O’Brien M. Observations on nutrition and hydration in dying cancer patients. In: Lynn J, ed. By no extraordinary means: the choice to forgo life-sustaining food and water. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1986:29–38.

5. White KS, Hall JC. Ethical dilemmas in artificial nutrition and hydration: decision-making. Nursing Case Manag 1999;4:152–157.

6. Evans WK, Nixon DW, Daly JM, et al. A random-ized study of oral nutritional support versus ad lib nutritional intake during chemotherapy for ad-vanced colorectal and non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1987;5:113–124.

7. Chiu TY, Hu WT, Chang RB, et al. Nutrition and hydration for terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:630–636.

8. Torosian MH, Daly JM. Nutritional support in the cancer-bearing host. Effects on host and tumor. Cancer 1986;58:1915–1929.

9. Huang ZB, Ahronheim JC. Nutrition and hydra-tion in terminally ill patients: an update. Clin Geriatr Med 2000;16:313–325.

10. Fainsinger RL, Bruera E. When to treat dehydra-tion in a terminally ill patient? Support Care Cancer 1997;5:205–211.

11. McCann RM, Hall WJ, Groth-Tuncker A. Com-fort care for terminally ill patients. The appropriate use of nutrition and hydration. JAMA 1994;272: 1263–1266.

12. Zerwekh JV. Do dying patients really need i.v. fluids? Am J Nurs 1997;97:26–30.

13. McInerney F. Provision of food and fluids in terminal cancer: a sociological analysis. Soc Sci Med 1992;34:1271–1276.

14. Scanlon C, Fleming C. Ethical issues in caring for the patient with advanced cancer. Nursing Clin N Am 1989;24:977–986.

15. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of bio-medical ethics, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

16. Meilaender G. Caring for the permanently un-conscious patient. In: Lynn J, ed. By no extraordi-nary means: the choice to forgo life-sustaining food and water. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1986:195–201.

17. Green W. Setting boundaries for artificial feed-ing. Hastings Center Report 1984;8–10.

18. Connelly RJ. The sentiment argument for artifi-cial feeding of the dying. Omega 1989;20:229–237. 19. Andrews MR, Levine AM. Dehydration in the terminally ill patient: perception of hospice nurses. Am J Hospice Care 1989;6:31–34.

20. Sutcliffe J. Dehydration: burden or benefit to the dying patient? J Adv Nurs 1994;19:71–76. 21. Parkash R, Burge F. The family’s perspective on issues of hydration in terminal care. J Palliat Care 1997;13:23–27.

22. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Cheng SY, et al. Ethical dilem-mas in palliative care: a study in Taiwan. J Med Ethics 2000;26:353–357.

23. Wallston KA, Stein MJ, Smith CA. Form C of the MHLC scales: a condition-specific measure of locus of control. J Pers Assess 1994;63:534–553.

24. Cheng YR, Wu EC, Lue BH. The outcome evalua-tion of biopsychosocial stress assessment and stress management [In Chinese, English abstract]. Re-search in Applied Psychology 1999;3:191–217. 25. Hu WY, Chiu TY, Dai YT, et al. Nurses’ willingness and the predictors of willingness to provide pallia-tive care in rural communities of Taiwan. J Pain Symp-tom Manage 2003;26:760–768.

26. The Hastings Center. Guidelines on the termi-nation of life-sustaining treatment and the care of the dying. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1987.

27. Burge FI, King DB, Willison D. Intravenous fluids and the hospitalized dying: a medical last rite? Can Fam Phys 1990;36:883–886.

28. Musgrave CF, Bartal N, Opstad J. Intravenous hydration for terminal patients: what are the atti-tudes of Israeli terminal patients, their families, and their health professionals? J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12:47–51.

29. Jenkins C, Bruera E. Assessment and manage-ment of medically ill patients who refuse life-pro-longing treatments: two case reports and proposed guidelines. J Palliat Care 1998;14:18–24.