ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES AND BREAST CANCER RISK IN TAIWAN,

A COUNTRY OF LOW INCIDENCE OF BREAST CANCER

AND LOW USE OF ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

Wei-Chu CHIE1*, Chung-Yi LI2, Chiun-Sheng HUANG3, King-Jen CHANG3, Men-Luh YEN4and Ruey-Shiung LIN5 1School of Public Health, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

2Department of Public Health, Catholic Fu-Jen University, Taipei, Taiwan 3Department of Surgery, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan 5Institute of Epidemiology, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

One hundred and seventy four (81% of all) pathologically confirmed new incident cases of female breast cancer identi-fied from a medical center in Taipei from February, 1993 to June, 1994 were selected as the case group. Four hundred and fifty three inpatient controls who were without obstetric-gynecological, breast, or malignant diseases were individually matched for each case by age and date of admission. Informa-tion was obtained through direct interview and review of medical records. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate the effects of each risk factor. After adjusting for education level, body mass index, age at menarche and first full-term pregnancy, parity, menopausal status and age at menopause, lifetime lactation, use of lactation inhibition hormones, and family history of breast cancer, breast cancer risk significantly elevated in use of OC before 25 years old and before 1971. In stratified analysis, significantly higher risk were found in OC use before 25 years old and in duration of use less than one year among post-menopausal subjects. Our results support the notion that OC use in early life for younger women and in early calendar years increase breast cancer risk. Int. J. Cancer 77:219–223, 1998.

r

1998 Wiley-Liss, Inc.The effects of oral contraceptives (OC) on the risk of developing breast cancer have been widely studied in Caucasian women but the results are inconclusive (Malone et al., 1993; Brinton and Shairer, 1993). In the review of Malone et al. (1993) there is no evidence of an increased risk of breast cancer in women who have ever used OC, except for the use in young age and long duration. In a meta-analysis, recency was the most important predictor (Collabo-rative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, 1996). Results of single studies on Caucasian women have been reported from the United States (Wingo et al., 1993) Canada (Rosensberg et al., 1992), South America (Gomes et al., 1995) and Europe (Lipworth

et al., 1995; Tavani et al., 1993; Rookus and van Leeuwen, 1994;

Chilvers et al., 1994). For Asian countries, a worldwide review of epidemiologic studies (Thomas, 1991) and reports of the WHO Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives (1990), and Stalsberg et al. (1989) have detected a small increase in risk of breast cancer in OC users in Asian low-incidence countries, as well as a trend of increasing risk along with longer duration of use and shorter recency. There have been very limited reports from single Asian countries. A case-control in Shanghai (Yuan et al., 1988) showed an elevated risk for longer duration and older age of use. Another case-control study in Indonesia (Bustan et al., 1993) found an elevated risk of breast cancer in ever users, especially for longer and recent use, as well as use in younger age.

Taiwan has had a very successful experience of birth control. The social and economic development further accelerated the declining of birth rate. The total fertility declined from 6.5 children per woman during the mid-1950s to 2 during the mid-1980s (Feeney, 1994). Contraception rate has been around 80% for more than 10 years since 1983 (Department of Health, 1993). Contracep-tive methods were introduced first by non-government organiza-tions, then supplied and promoted by the government with strong

political commitment and policy supports since 1965. However, unlike Western countries, the use of OC was much lower than other contraceptive methods. The aim of our study was thus to assess the effects of OC use on the risk of breast cancer in a country of both low incidence of breast cancer and low use of OC. We report here the results of a hospital-based case-control study conducted in Taipei.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The ‘‘cases’’ in our study constituted a total of 174 (81% of all according to the Cancer Registry) consecutive pathologically confirmed new incident cases of female breast cancer in a teaching hospital (National Taiwan University Hospital) from February 1993 to June 1994. Pathological reports and medical records of these subjects were reviewed to rule out misclassification. Of the 19% cases not included, most were due to a random information delay after admission. Only 2 eligible cases refused the interview. For each case, we selected 1 to 3 female inpatients from medical, surgical, orthopedic, urological, ophthalmic, ENT and dentistry wards, as the ‘‘controls’’ who were free from obstetric-gynecologi-cal, breast, or malignant diseases according to the daily computer record of the Division of Admission of the same hospital. The controls were aged-matched (within 3 years) and time-matched (within 1 week admission) to the case. If more than 3 were eligible, the 3 with closest matching conditions were chosen as controls. A total of 453 controls were selected. Medical records were reviewed to ensure the eligibility of control status. All cases and controls were interviewed at hospital, using a pre-designed questionnaire by trained interviewers under the permission of the subjects them-selves and their surgeons or physicians. Periodical meeting, medical record checking and telephone re-interview were used to improved the quality of data. Health education pamphlets were kept from the study subjects until the end of the interview. The interviewers were instructed not to read news and articles about breast cancer risk before all data were collected. Medical records were reviewed to verify the medical history, height and weight of the subjects.

Risk factors studied were OC use, including age and calendar year at first use, temporal relation of OC use and age at first full-term pregnancy, total duration of OC use. Recency of OC use was not studied because we only included the time of first use and duration of use but not the time of last use and the pattern of use.

Grant sponsor: the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan; Grant number: DOH-83-HP-10-4M3.

*Correspondence to: Room 209, Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, 19, Hsuchow Road, Taipei, 10020, Taiwan. Fax: (886)-2-2392-0456. E-mail: weichu@episerv.cph.ntu.edu.tw

Received 25 November 1997; Revised 19 January 1998

Int. J. Cancer: 77, 219–223 (1998)

Education level, body mass index, age at menarche, age at first full-term pregnancy, parity, menopausal status and age at meno-pause (defined as the age of last menstruation after 1 year free of menstrual cycles), duration of life-time lactation, family history of breast cancer, use of female sex hormones other than OC and lactation suppression hormones, found in our previous studies (Chie et al., 1996a,b, 1997a,b, 1998), were considered as potential confounders for the effect of OC use. Alcohol was not adjusted for since women in Taiwan seldom drink alcohol to the same extent as Western women. Neither was history of benign breast disease because it might be an intermediate variable. Conditional multiple logistic regression (proc phreg of the SAS package, SAS Institute, 1991) was used to estimate the effects of all risk factors with all potential confounders being adjusted. In further stratification into pre- and post-menopausal groups, only risk sets in which both the case and at least one control belonged to the same group, were analyzed.

RESULTS

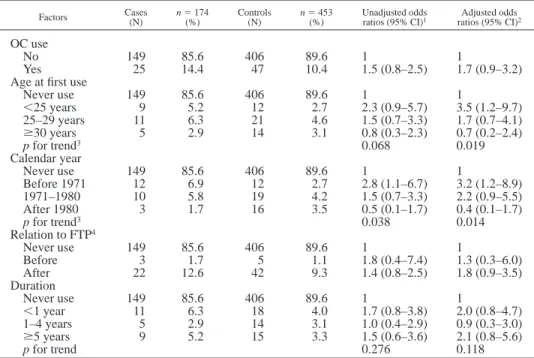

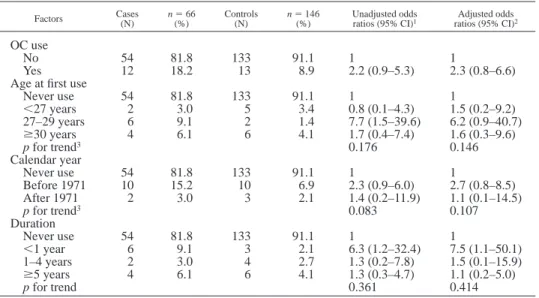

Cases and controls are comparable in age. Means and standard deviations of the 2 groups are 47.76 10.4 years vs. 47.5 6 10.4 years. Table I shows the distribution of education level and major reproductive risk factors of cases and controls. Table II presents the effect of OC use for all subjects. After adjusting for education level, body mass index, ages at menarche and first full-term pregnancy, parity, menopausal status and age at menopause, lifetime lactation, family history of breast cancer, use of female sex hormones other than OC and lactation suppression hormones, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for OC use was 1.7 (95% CI5 0.9–3.2). The adjusted OR for OC use before 25 years old vs. never use was 3.4 (95% CI5 1.2–9.7); p for trend was 0.019. The adjusted OR for OC use before 1971 vs. never use was 3.2 (95% CI5 1.2–8.9); p for trend was 0.014. Table III presents the effects of OC use on breast cancer risk in pre-menopausal subjects. The adjusted OR for age at first use,25 years vs. never use was 5.8 (95% CI 5 1.5–22.1); p for trend5 0.04, for duration $5 years vs. never use was 3.5 (95% CI5 0.9–14.3). Table IV presents the effect of OC use for post-menopausal subjects. The adjusted OR of duration less than one year vs. never use was 7.5 (95% CI5 1.1–50.1). We also examined the relation between calendar year at first use, age at first use, duration, and relation to age at first full-term pregnancy by cross tabulation and chi-square test. The calendar year at first use was not related to age at first use, and duration. More subjects who used OC later in calendar year started OC use before age at first full-term pregnancy. (Table V).

DISCUSSION

We have found a moderate but not statistically significant increased risk of breast cancer in OC users. Previous studies conducted elsewhere in Asia (Thomas, 1991; WHO Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives, 1990; Stalsberg et

al., 1989; Bustan et al., 1993), Brazil (Gomes et al., 1995), and

Italy (Tavani et al., 1993) but not those in Greece (Lipworth et al., 1995) and China (Yuan et al., 1988) also found a moderately elevated risk. Explanation by Stalsberg et al. (1989) that OC may release a latent growth potential of lobular cells not previously influenced by nutrition or other factors may be applicable in Taiwan, since its pattern of breast cancer (Department of Health, 1994) is similar to those of other low-risk countries. Laboratory experiments, however, did not find elevated cell proliferation (Going et al., 1988) or estrogen conversion (Soderqvist et al., 1994) in OC users.

The elevated risk for of early life and longer use especially in young (pre-menopausal in our study) subjects are consistent with the present conclusions (Malone et al., 1993; Brinton and Shairer,

1993; Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, 1996) and recent studies in the United States (Wingo et al., 1993), Canada (Rosenberg et al., 1992), The Netherlands (Rookus and van Leeuwen, 1994), and the United Kingdom (Chilvers et al., 1994), but not with several other studies conducted in China (Yuan et al., 1988) and southern Europe (Lipworth et al., 1995; Tavani et al., 1993; Primic-Zabelj et al., 1995). The negative result of the temporal relation with age at first full-term pregnancy was different from that of a study in Italy (Tavani et al., 1993). Age of exposure is more critical than the temporal relation with important reproduc-tive events in breast cancer risk in Taiwan. Only one study performed in Greece (Lipworth et al., 1995) exhibited finding similar to ours of an increased risk with very short duration of OC use in the post-menopausal group. Other previous studies showed an increased (Rookus and van Leeuwen, 1994) or no change (Wingo et al., 1993) of risk for longer duration of use in older ages. The explanation is unclear. It is possible that the post-menopausal subjects who had a very short duration of OC use might have had health conditions which caused both a stop of use and an elevation of risk of breast cancer.

The most interesting and unique finding of our study is the elevated breast cancer risk in users of earlier calendar years (before 1971). This has never been reported in previous studies either in Western or Asian countries. The use of OC is not common in Taiwan. Women in Taiwan seldom know the brand, content and dosage of OC they are using. However, because almost all the OC were provided by the Provincial Institute of Family Planning and Centers of Family Planning of Taipei and Kaoshiung, and the dose of estrogen and progestin decreased by calendar years, we can use calendar year as a surrogate of dosage. This result suggested that earlier brands of higher dosage of estrogen and progestin may increase breast cancer risk. Since calendar year of first use was not

TABLE I – EDUCATION LEVEL AND MAJOR REPRODUCTIVE RISK FACTORS FOR BREAST CANCER IN ALL SUBJECTS

Factors Cases(N) n5 174(%) Controls(N) n5 453(%)

Education level Illiterate 19 10.9 72 15.9 Elementary school 52 29.9 155 34.2 High school 57 32.8 131 28.9 College 46 26.4 96 21.2 Age at menarche #12 23 13.2 36 7.9 13–14 68 39.1 176 38.9 15–16 58 33.3 178 39.3 $17 25 14.4 61 13.5 Unknown 0 0.0 2 0.4 Age at menopause Not yet 103 59.2 267 58.9 Before 50 years 26 14.9 94 20.8 After 50 years 40 23.0 84 18.5 Age unknown 5 2.8 8 1.8 Parity 0 17 9.7 37 8.2 1 24 14.0 37 8.2 2 50 28.7 111 24.5 3 45 25.9 115 25.4 4 22 12.6 77 17.0 $5 16 9.2 76 16.8 Age at first FTP1 ,20 years 9 5.2 51 11.3 20–24 years 65 37.4 187 41.3 25–29 years 60 34.5 147 32.5 30–34 years 16 9.2 28 6.2 $35 years 7 4.0 3 0.6 Nulliparous 17 9.8 37 8.2 1FTP: full-term pregnancy.

associated with age of first use and duration of use, their effects on breast cancer could not be explained by the effects of each other.

We did not assess the effect of latency or recency because of lack of data for the time of last use and the pattern of use (continuing or intermittent). If we take the time of first use plus duration of use as

the time of last use, since the duration of use of most subjects was relatively short (only 3.5% of the controls used OC over 5 years), the recency might be close to the true time of last use, but its effect will be confounded by the calendar year of first use and thus not be able to offer correct information for risk assessment.

TABLE II – ODDS RATIOS FOR ORAL CONTRACEPTIVE USE FOR BREAST CANCER RISK IN ALL SUBJECTS Factors Cases(N) n5 174(%) Controls(N) n5 453(%) Unadjusted oddsratios (95% CI)1 ratios (95% CI)Adjusted odds2

OC use

No 149 85.6 406 89.6 1 1

Yes 25 14.4 47 10.4 1.5 (0.8–2.5) 1.7 (0.9–3.2)

Age at first use

Never use 149 85.6 406 89.6 1 1 ,25 years 9 5.2 12 2.7 2.3 (0.9–5.7) 3.5 (1.2–9.7) 25–29 years 11 6.3 21 4.6 1.5 (0.7–3.3) 1.7 (0.7–4.1) $30 years 5 2.9 14 3.1 0.8 (0.3–2.3) 0.7 (0.2–2.4) p for trend3 0.068 0.019 Calendar year Never use 149 85.6 406 89.6 1 1 Before 1971 12 6.9 12 2.7 2.8 (1.1–6.7) 3.2 (1.2–8.9) 1971–1980 10 5.8 19 4.2 1.5 (0.7–3.3) 2.2 (0.9–5.5) After 1980 3 1.7 16 3.5 0.5 (0.1–1.7) 0.4 (0.1–1.7) p for trend3 0.038 0.014 Relation to FTP4 Never use 149 85.6 406 89.6 1 1 Before 3 1.7 5 1.1 1.8 (0.4–7.4) 1.3 (0.3–6.0) After 22 12.6 42 9.3 1.4 (0.8–2.5) 1.8 (0.9–3.5) Duration Never use 149 85.6 406 89.6 1 1 ,1 year 11 6.3 18 4.0 1.7 (0.8–3.8) 2.0 (0.8–4.7) 1–4 years 5 2.9 14 3.1 1.0 (0.4–2.9) 0.9 (0.3–3.0) $5 years 9 5.2 15 3.3 1.5 (0.6–3.6) 2.1 (0.8–5.6) p for trend 0.276 0.118

1CI, confidence interval.–2Adjusted for education level, body mass index, ages at menarche and first full-term

pregnancy, parity, menopausal status and age at menopause, lifetime lactation, and family history of breast cancer,

hormone use other than OC, and lactation suppression hormones.–3Reversed trend.–4Full-term pregnancy.

TABLE III – ODDS RATIOS FOR ORAL CONTRACEPTIVE, FOR BREAST CANCER RISK IN PREMENOPAUSAL SUBJECTS

Factors Cases(N) n(%)5 97 Controls(N) n5 237(%) Unadjusted oddsratios (95% CI)1 ratios (95% CI)Adjusted odds2

OC use

No 84 86.6 211 89.0 1 1

Yes 13 13.4 26 11.0 1.3 (0.6–2.7) 1.6 (0.7–3.8)

Age at first use

Never use 84 86.6 211 89.0 1 1 ,25 years 8 8.3 7 3.0 3.3 (1.1–10.5) 5.8 (1.5–22.1) 25–27 years 2 2.1 8 3.4 0.8 (0.2–3.6) 1.0 (0.2–5.7) $27 years 3 3.1 11 4.6 0.5 (0.1–2.4) 0.4 (0.06–2.5) p for trend3 0.140 0.040 Calendar year Never use 84 86.6 211 89.0 1 1 Before 1971 2 2.1 1 0.4 3.7 (0.3–43.9) 6.4 (0.4–104.6) 1971–1980 8 8.3 11 4.6 1.9 (0.7–4.9) 3.5 (1.1–11.1) After 1980 3 3.1 14 5.9 0.6 (0.1–2.2) 0.4 (0.09–1.9) p for trend3 0.220 0.064 Relation to FTP4 Never use 84 86.6 211 89.0 1 1 Before 3 3.1 5 2.1 1.7 (0.4–7.3) 1.1 (0.2–5.5) After 10 10.3 21 8.9 1.2 (0.5–2.8) 1.8 (0.7–5.1) Duration Never use 84 86.6 211 89.0 1 1 ,1 year 5 5.2 12 5.1 1.0 (0.3–3.0) 1.0 (0.3–4.1) 1–4 years 3 3.1 8 3.4 1.0 (0.2–3.8) 1.0 (0.2–4.9) $5 years 5 5.2 6 2.5 2.3 (0.7–8.3) 3.5 (0.9–14.3) p for trend 0.313 0.145

1CI, confidence interval.–2Adjusted for education level, body mass index, ages at menarche and first

full-term pregnancy, parity, lifetime lactation, and family history of breast cancer, the use of female sex

Our study involves a small sample size and has a limited power of test especially in further stratification into pre- and post-menopausal groups. It is a common limitation of single studies in low-incidence countries. Moreover, most of the trends were not significant. Without a dose-response relationship, we should interpret our isolated elevation of risk with caution. Regarding selection bias, although we used hospital controls, the study might not be affected too much by selection bias. The major reason is that both the use of OC and the contra-indications for OC use such as cardiovascular diseases, are low in Taiwan as compared with Western countries. In the past, most OC were supplied by health stations without physician evaluation and prescription with a strict concern of contra-indications. In addition, women in Taiwan seldom perform breast self-examination or undergo mammography (Chie et al., 1993; Chie and Chang, 1994). Physicians might not be able to know patients’ detailed OC history, either. Screening bias might be unlikely to happen. Therefore, controls (even hospital controls) in Taiwan might be more representative of the population at risk, while those of Western countries are over-selected as a lower risk group because of their previous knowledge of breast cancer and contra-indications of OC use. Since women in Taiwan were not given clear information about OC and risk of breast

cancer, information bias is less likely to have happened. Regarding confounding, we had adjusted all possible potential confounders and their effects should not be a problem.

In conclusion, the risk of breast cancer appears moderately elevated in OC users starting use before 25 years of age, especially in the pre-menopausal group, and early calendar years (before 1971), as well as very short duration (#1 year) in the post-menopausal group, in a population of low incidence of breast cancer and low OC use.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Yih-Jian Tsai, Provincial Institute of Family Planning, for providing brand names and content of OC ever used in Taiwan, to research assistants Misses Lan-Shin Hung, Wu-Mei Feng and Yi-Ying Chiang for data management, to interviewers Misses Shi-Lai Lee, Lai-Yan Cheung, and Kwok Kwan for data collection, Miss Yu-Wen Dai for height and weight checking, Drs. Kin-Wei A. Chan and Wen-Chung Lee for their helpful comments, as well as to the participants interviewed. We acknowledge the administrative support from National Taiwan University Hospital.

TABLE IV – ODDS RATIOS FOR ORAL CONTRACEPTIVE USE, FOR BREAST CANCER RISK IN POSTMENOPAUSAL SUBJECTS

Factors Cases(N) n(%)5 66 Controls(N) n5 146(%) Unadjusted oddsratios (95% CI)1 ratios (95% CI)Adjusted odds2

OC use

No 54 81.8 133 91.1 1 1

Yes 12 18.2 13 8.9 2.2 (0.9–5.3) 2.3 (0.8–6.6)

Age at first use

Never use 54 81.8 133 91.1 1 1 ,27 years 2 3.0 5 3.4 0.8 (0.1–4.3) 1.5 (0.2–9.2) 27–29 years 6 9.1 2 1.4 7.7 (1.5–39.6) 6.2 (0.9–40.7) $30 years 4 6.1 6 4.1 1.7 (0.4–7.4) 1.6 (0.3–9.6) p for trend3 0.176 0.146 Calendar year Never use 54 81.8 133 91.1 1 1 Before 1971 10 15.2 10 6.9 2.3 (0.9–6.0) 2.7 (0.8–8.5) After 1971 2 3.0 3 2.1 1.4 (0.2–11.9) 1.1 (0.1–14.5) p for trend3 0.083 0.107 Duration Never use 54 81.8 133 91.1 1 1 ,1 year 6 9.1 3 2.1 6.3 (1.2–32.4) 7.5 (1.1–50.1) 1–4 years 2 3.0 4 2.7 1.3 (0.2–7.8) 1.5 (0.1–15.9) $5 years 4 6.1 6 4.1 1.3 (0.3–4.7) 1.1 (0.2–5.0) p for trend 0.361 0.414

1CI, confidence interval.–2Adjusted for education level, body mass index, ages at menarche and first

full-term pregnancy, parity, age at menopause, lifetime lactation, and family history of breast cancer, the

use of female sex hormones other OC, and lactation suppression hormone.–3Reverse trend.

TABLE V – CROSS TABLE OF CALENDAR YEAR OF FIRST USE, AGE AT FIRST USE, DURATION, AND RELATION TO FIRST FTP OF OC USERS (n5 72)

Before 1971 1971–1980 After 1980 Chi-square

and p

N % N % N %

Age at first use

,25 years 7 29.7 10 34.5 4 21.1 x25 1.32 25–29 years 11 45.8 11 37.9 10 52.6 p5 0.86 $30 years 6 25.0 8 27.6 8 26.3 (d.f.15 4) Duration ,1 year 11 45.8 10 34.5 8 42.1 x25 0.80 1–4 years 6 25.0 8 27.6 5 26.3 p5 0.94 $5 years 7 29.2 11 37.9 6 31.6 (d.f.15 4) Relation to FTP3 Before 0 0.0 3 4.2 5 26.3 x25 7.472 After 24 100.0 26 89.7 14 73.7 p5 0.02 (d.f.15 2)

1Degree of freedom.–2Should be interpreted with caution because no subjects used OC before 1971 and

REFERENCES BRINTON, L.A. and SHAIRER, C., Estrogen replacement therapy and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev., 15, 66–79 (1993).

BUSTAN, M.N., COKER, A.L., ADDY, C.L., MACERA, C.A., GREENE, F. and SAMPOERNO, D., Oral contraceptive use and breast cancer in Indonesia. Contraception, 47, 241–249 (1993).

CHIE, W.C. and CHANG, K.J., Factors related to tumor size of breast cancer at treatment in Taiwan. Prev. Med., 23, 91–97 (1994).

CHIE, W.C., CHEN, C.F., LEE, W.C. and CHEN, C.J., Body size and risk of pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer in Taiwan. Anticancer Res., 16, 3129–3132 (1996a).

CHIE, W.C., CHEN, C.F., LEE, W.C. and CHEN, C.J., Socioeconomic status, lactation and breast cancer risk of parous women in Taiwan. Oncol. Rep., 3, 497–501 (1996b).

CHIE, W.C., CHENG, K.W., FU, C.H., and YEN, L.L., A study on women’s practice of breast self-examination in Taiwan. Prev. Med., 22, 316–324 (1993).

CHIE, W.C., FU, C.M., LEE, W.C., LI, C.Y., HUANG, C.S., CHANG, K.J. and LIN, R.S., Ages at different reproductive events, numbers of menstrual cycles in between and breast cancer risk. Oncol. Rep., 4, 1039–1043 (1997b).

CHIE, W.C., LEE, W.C., LI, C.Y., HUANG, C.S., CHANG, K.J., YEN, M.L. and LIN, R.S., Lactation, lactation suppression hormones and breast cancer: a hospital-based case-control study for parous women in Taiwan. Oncol. Rep., 4, 319–326 (1997a).

CHIE, W.C., LI, C.Y., HUANG, C.S., CHANG, K.J. and LIN, R.S., Body size as a factor in different ages and breast cancer risk in Taiwan. Anticancer Res., 18, 565–570 (1998).

CHILVERS, C.E.D., SMITH, S.J. and MEMBERS OF THE UK NATIONAL CASE-CONTROLSTUDYGROUP, The patterns of oral contraceptive use on breast cancer risk in young women. Brit. J. Cancer, 67, 922–923 (1994). COLLABORATIVE GROUP ON HORMONAL FACTORS IN BREAST CANCERS, Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet, 347, 1713–1727 (1996).

DEPARTMENT OFHEALTH, EXECUTIVEYUAN, TAIPEI, TAIWAN, Health White Paper, 23–30 (1993).

DEPARTMENT OFHEALTH, EXECUTIVEYUAN, TAIPEI, TAIWAN, Cancer Regis-try Annual Report (1994).

FEENEY, G., Fertility decline in East Asia. Science, 266, 1518–1523 (1994). GOING, J.J., ANDERSON, T.J., BATTERSBY, S. and MACINTYRE, C.C.A., Proliferative and secretory activity in human breast during natural and artificial menstrual cycles. Amer. J. Pathol., 130, 193–204 (1988).

GOMES, A.L.R.R., GUIMARAES, M.D.C., GOMES, C.C., CHAVES, I.G., GOBBI, H. and CAMARGO, A.F., A case-control study of risk factor for breast cancer in Brazil, 1978–1987. Int. J. Epidemiol., 24, 292–299 (1995).

LIPWORTH, L., KATSOUYANNI, K., STUVER, S., SAMOLI, E., HANKNINSON, S.E. and TRICHOPOULOS, D., Oral contraceptives, menopausal estrogens, and the risk of breast cancer: a case-control study in Greece. Int. J. Cancer, 62, 548–551 (1995).

MALONE, K.E., DALING, J.D. and WEISS, N.S., Oral contraceptives in relation to breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev., 15, 80–97 (1993).

PRIMIC-ZAKELJ, M., EVSTIFEEVA, T., RAVNIHAR, B. and BOYLE, P., Breast cancer risk and oral contraceptive use in Slovenian women aged 25 to 54. Int. J. Cancer, 62, 414–420 (1995).

ROOKUS, M.A. andVAN LEEUWEN, F.E., Oral contraceptives and risk of breast cancer in women aged 20–54 years. Lancet, 344, 844–851 (1994). ROSENBERG, L., PALMER, J., CLARKE, E.A. and SHAPIRO, S., A case-control study of the risk of breast cancer in relation to oral contraceptive use. Amer. J. Epidemiol., 136, 1427–1444 (1992).

SAS INSTITUTEINC., SAS Technical Report P-217 SAS/STAT Software: The PHREG Procedure, Version 6, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC (1991). SODERQVIST, G., OLSSON, H., WILKING, N.,VONSCHOULTZ, B. and CARL -STROM, K., Metabolism of estrone sulfate by normal breast tissue: influence of menopausal status and oral contraceptives. J. Steroid Biochem. mol. Biol., 48, 221–224 (1994).

STALSBERG, H., THOMAS, D.B., NOONAN, E.A. andTHEWHO COLLABORA -TIVESTUDY OFNEOPLASIA ANDSTEROIDCONTRACEPTIVES, Histologic types of breast carcinoma in relation to international variation and breast risk factors. Int. J. Cancer, 44, 399–409 (1989).

TAVANI, A., NEGRI, E., FRANCESCHI, S., PARASSINI, F. and LAVECCHIA, C., Oral contraceptives and breast cancer in Northern Italy. Final report from a case-control study. Brit. J. Cancer, 68, 568–571 (1993).

THOMAS, D.B., Oral contraceptives and breast cancer: review of the epidemiologic literature. Contraception, 43, 597–642 (1991).

WHO COLLABORATIVESTUDY OFNEOPLASIA ANDSTEROIDCONTRACEPTIVES, Breast cancer and combined oral contraceptives: results from a multina-tional study. Brit. J. Cancer, 61, 110–119 (1990).

WINGO, P.A., LEE, N.C., ORY, H.W., BERAL, V., PETERSON, H.B. and RHODES, P., Age-specific differences in the relationship between oral contraceptive use and breast cancer. Cancer, 71, 1506–1517 (1993). YUAN, J.-M., YU, M.C., ROSS, R.K., GAO, Y.-T. and HENDERSON, B.E., Risk factors for breast cancer in Chinese women in Shanghai. Cancer Res., 48, 1949–1953 (1988).