Payment and emergency medical service in central Taiwan

全文

(2) 100. Payment and ED in Central Taiwan. struggle to support the high cost of the emergency department while trying to control expenditures. A recent report by Tsai et al found that the reimbursements for emergency department care are declining [3]. In Taiwan, the national health insurance (NHI) system was established in 1995. NHI expenditure was about 5.3% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2001, less than half that of other developed countries [4-6]. However, as in other industrialized nations, increasing health care costs are a major issue in Taiwan. Financial pressures in the NHI system may play a major role in molding the future development of emergency medicine. This change will have a considerable negative impact on medical services as well as on the emergency medical service system. Hospital managers tend to modify their strategy of services to fit the changes in reimbursement. However, for hospital administrators, the task of developing a strategy for emergency medical services is very difficult because of the high cost, high staff turnover rate and decreasing revenue. Hospital managers urgently need to reevaluate existing strategies for managing costs in the ED. The financial constraints placed on medical providers will have serious consequences. The aim of this study was to analyze the current management strategies of EDs and to provide cost-based information about emergency medicial services (EMS) for the purpose of making betterinformed decisions in ED management in Taiwan. MATERIALS AND METHODS. A convenience sampling of ED services in central Taiwan was performed in 2002. The hospitals were located in an urban township, a suburban township (21districts) and a rural township (13 districts). Data of ED services included number of visitors, distribution of patients' triage, number of transfers, and the contribution of hospital admission. Physicians' salaries (both full-time and part-time) were collected by ED managers. A full-time emergency department physician was defined as a physician working at an ED without providing inpatient services. Emergency physicians working less than. full-time were defined as part-time physicians. The number of payments made by patients in the ED were obtained from reference data provided by the Taiwan National Health Research Institution. Patients with life-threatening or potentially life-threatening conditions in need of immediate treatment were classified in category I. Patients with obvious discomfort but normal vital signs who required treatment within 10 minutes of arrival were classified in category II. Patients with less obvious discomfort who could be treated within 30 minutes of arrival were classified into category III. Patients who were referred to ambulatory care were classified into category IV. Emergency cases in this study were defined as patients triage classified in category I. Urgent patients were defined as patients classified in category II. Hospitals were categorized into three different levels according to the number of hospital beds; level A hospitals were medical centers with more than 500 beds, level B were composed of regional hospitals with 200 to 499 beds and level C comprised local hospitals with less than 200 beds. The number of visits to EDs in the same district were added together. Data on population density in 2001 were provided by the Ministry of the Interior. The ratio of the New Taiwan dollar to the US dollar was 34.575 to 1 (annual average) in 2001 [7]. The reletionship between ED visits and population density was analyzed by linear regression. The statistical method used was one way ANOVA. RESULTS. Seventy-seven hospitals provided emergency medical services in the three townships. Emergency departments with a small number of visits, those without 24-hour services and hospitals with less than 50 beds were excluded. The remaining 60 hospitals were investigated. Data from 18 of 20 urban EDs (response rate = 90%), 28 of 38 suburban EDs (response rate = 74%) and 12 rural EDs (response rate = 100%) were collected. Of these, complete.

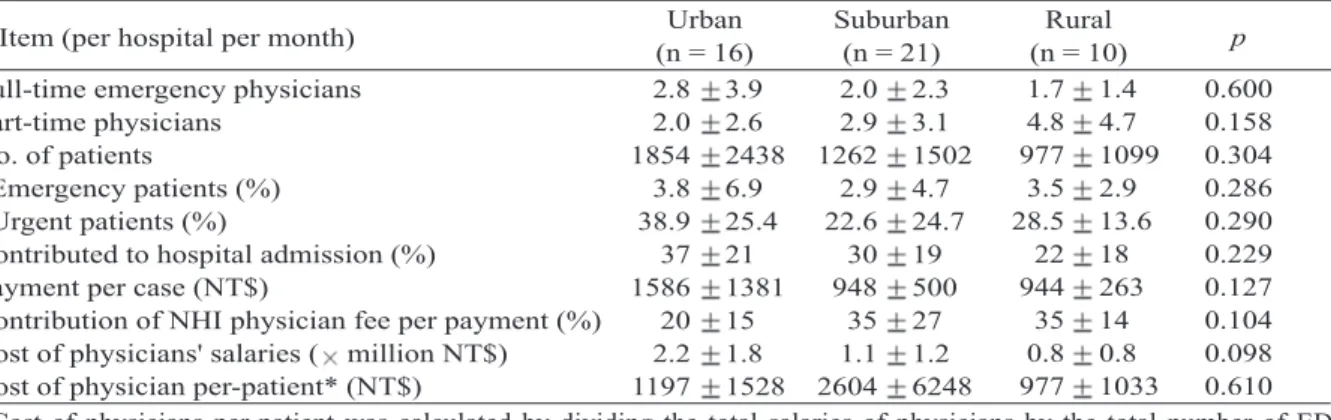

(3) Wei-Kung Chen, et al.. 101. Table 1. Basic data of hospitals and emergency departments in urban, suburban and rural townships of central Taiwan Township Urban (%) Suburban (%) Rural (%) 18 (100) 28 (100) 12 (100) No. of hospitals 3 (17) 0 0 Level A (hospital beds > 500) 2 (11) 7 (25) 0 Level B (hospital beds 200 500) 13 (72) 21 (75) 12 (100) Level C (hospital beds < 200) No. of patients (per month) 10 (56) 16 (57) 6 (50) ≤ 500 2 (11) 7 (25) 4 (33) 501 2000 2 (11) 4 (14) 2 (17) 2001 4000 3 (17) 1 (4) 0 4001 6000 1 (5) 0 > 6000. Table 2. Comparison of emergency departments in urban, suburban and rural townships Suburban Rural Urban p Item (per hospital per month) (n = 21) (n = 10) (n = 16) 0.600 1.7 1.4 Full-time emergency physicians 2.8 3.9 2.0 2.3 0.158 4.8 4.7 Part-time physicians 2.0 2.6 2.9 3.1 0.304 977 1099 No. of patients 1854 2438 1262 1502 0.286 3.5 2.9 Emergency patients (%) 3.8 6.9 2.9 4.7 0.290 28.5 13.6 Urgent patients (%) 38.9 25.4 22.6 24.7 0.229 22 18 Contributed to hospital admission (%) 37 21 30 19 0.127 944 263 Payment per case (NT$) 1586 1381 948 500 0.104 35 14 Contribution of NHI physician fee per payment (%) 20 15 35 27 0.098 0.8 0.8 Cost of physicians' salaries ( million NT$) 2.2 1.8 1.1 1.2 0.610 977 1033 Cost of physician per-patient* (NT$) 1197 1528 2604 6248 *Cost of physicians per-patient was calculated by dividing the total salaries of physicians by the total number of ED patients.. Figure. The relationship between emergency department visits and population density in different townships.. data (including physician cost data) were obtained from 16 of 20 urban EDs, 21 of 38 suburban EDs and 10 of 12 rural EDs. Table 1 shows the basic data of hospitals in the three different townships. The patient number per month was equal to or less than 500 (6000. patients yearly) in half of the hospitals. Patient numbers exceeding 4000 per month (48,000 patients yearly) were mostly in urban EDs. The correlation between ED visits per month and population density in suburban and rural districts are shown in Figure. The number of patient visits in the same district equaled 1348 + 0. 62 population density (R2 = 0.266, p < 0.05). Comparisons of EDs in different townships are shown in Table 2. The characteristics of physician manpower, the number of visits, the cost of physicians' salaries and reimbursement from the NHI did not differ significantly among urban, suburban and rural townships. Table 3 compares EDs in different levels of hospital. There were more full-time emergency room physicians in level A hospitals than in level B or C hospitals. In contrast, the number of part-time emergency room physicians was higher in level C than in level A or B hospitals. The percentage of emergency and urgent patients and the percentage.

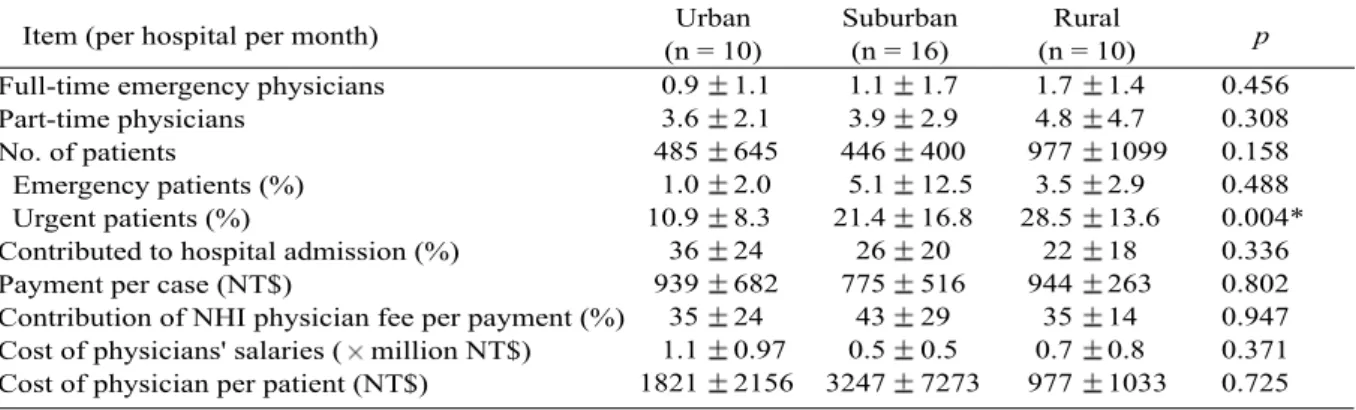

(4) 102. Payment and ED in Central Taiwan. Table 3. Comparison of emergency departments in different hospital levels Level A Level B Item (per hospital per month) (n = 3) (n = 8) 9.0 3.6 3.2 2.4 Full-time emergency physicians 0 0 1.4 2.9 Part-time physicians 5900 2424 3010 1330 No. of patients 5.1 3.2 2.5 2.7 Emergency patients (%) 47.3 5.8 38.6 12.5 Urgent patients (%) 313 185 82 61 Referred cases (%) 36 10 41 18 Contributed to hospital admission (%) 1947 738 1049 472 Payment per case (NT$) 17 7 31 16 Contribution of NHI physician fee per payment (%) 2.9 2.1 2.2 1.3 Cost of physicians' salaries ( million NT$) 573 134 835 430 Cost of physician per patient (NT$). Level C (n = 36) 1.2 1.5 4.1 3.4 611 770 3.5 6.5 21.9 20.8 7 10 28 20 860 513 38 24 0.64 0.67 1160 1171. p 0.001 0.048 0.001 0.001 0.006 0.001 0.142 0.001 0.021 0.001 0.747. Table 4. Comparison of emergency departments in level C hospitals in urban, suburban and rural townships Suburban Rural Urban p Item (per hospital per month) (n = 16) (n = 10) (n = 10) 0.456 0.9 1.1 1.1 1.7 1.7 1.4 Full-time emergency physicians 0.308 3.6 2.1 3.9 2.9 4.8 4.7 Part-time physicians 0.158 485 645 446 400 977 1099 No. of patients 0.488 1.0 2.0 5.1 12.5 3.5 2.9 Emergency patients (%) 0.004* 10.9 8.3 21.4 16.8 28.5 13.6 Urgent patients (%) 0.336 36 24 26 20 22 18 Contributed to hospital admission (%) 0.802 939 682 775 516 944 263 Payment per case (NT$) 0.947 35 24 43 29 35 14 Contribution of NHI physician fee per payment (%) 0.371 1.1 0.97 0.5 0.5 0.7 0.8 Cost of physicians' salaries ( million NT$) 0.725 1821 2156 3247 7273 977 1033 Cost of physician per patient (NT$). * The percentage of urgent patients in urban EDs was significantly lower than those in suburban and rural townships.. of patients referred from other hospitals were higher in level A hospitals than in level B or C hospitals. There were no significant differences in the number of hospital admissions between different hospital levels. The payment per case and physicians' salaries were highest in level A hospitals, but the cost of physicians per patient did not differ significantly between hospital levels. Level C EDs in urban, suburban and rural townships are compared in Table 4. There was no difference in hospital level in regards to location. However, the percentage of urgent patients in urban EDs was significantly lower than those in suburban and rural townships. DISCUSSION Urban EDs with low patient numbers are hard to maintain. As our data show, the capacity of EDs in urban, suburban and rural townships varied considerably. Half of the EDs in each township. had a small number of patients (< 500 per month). In urban townships, most patients visit large hospitals for treatment because larger hospitals are perceived to offer better emergency management and to provide superior medical facilities and overall care. In addition, medical resources in urban townships can be easily accessed. Hence, small EDs in urban townships play a lesser role in EMS and, of course, EDs with relatively limited functions are far less effective. Some hospital managers of EDs in urban townships over-emphasize the importance of admission resources and profit from the ED [8]. However, the cost efficiency of urban EDs is reduced by the small number of patients. As expenditure controls reduce payments by the NHI, EDs with a small number of visitors and high maintenance costs will inevitably struggle due to reduced profit, wasting of emergency physician manpower and problems maintaining adequate quality of care. Decreased funding in.

(5) Wei-Kung Chen, et al.. less competitive hospitals with small reserves may precipitate closure of these hospitals [9]. Some EDs should consider integrating with other EDs. There was a large difference between suburban and rural townships in the number of ED visits to hospitals of the same level. Many of the townships surveyed, especially suburban ones, had more than 2 EDs in the same township with few ED visits. Our data show that the number of patients who visited EDs was significantly related to population density. An analysis of the relationship between number of ED visits and population density may give an indication of how many EDs can be reasonably sustained in these districts. For example, as our data show, if the number of visits to an ED were to exceed 2000 per month, the population density of the district would need to be higher than 1100/Km2. This analysis can also be used to calculate the minimum number of emergency physicians required in a given district where expenditures are being controlled. EDs and emergency physicians in the same district need to consider the consequences of a fixed number of patients in a district with a relatively even population density, especially in suburban and rural districts. Sharing the small number of ED visits will lead to financial imbalance and less cost-efficient manpower utilization because of the high costs required to maintain these EDs. Because of the low population density and low number of patient visits, rural emergency departments may be unable to keep several full-time emergency physicians. Therefore, if functional EDs are to be maintained as part of the EMS in rural townships, government subsidy should be considered. Low payment will hurt emergency care. Our data also revealed that the cost of physicians was higher than the NHI payment for physicians' fees. This finding was more obvious in rural EDs than in urban EDs, where even part-time physicians, who cost less for hospitals, comprised the majority of the manpower. Regarding payment methods based on triage categories and fixed grants, lower disease severity. 103. and higher transfer rates decreased the amount the NHI reimbursed hospitals in rural townships. The distribution of payment per patient from the NHI to the physician was lower in urban townships than in rural townships. Compared with Williams' finding that physicians' fees accounted for about 31% of the cost of each patient, the contribution of physicians' fees in the present study was less reasonable than in the United States [10]. The distribution of what is considered reasonable payment varies around the world and reflects the value a country places on emergency physicians in its health care system. ED services represent a major source of inpatient hospital revenue, so policymakers have considered including "benefit sharing" in the payment to the ED from admission profit. However, hospital managers are not legally required to implement the plan. The recognition of the ED's potential in a township may be lost if income generated from patients admitted through the ED is credited to traditional hospital-based services. Policy failure will hurt the development of emergency medical services, resulting in an incomplete medical safety net [11-13]. EDs need a reasonable payment system. The conflict between managed care and emergency medical services is a controversial topic [14]. Any process which aims to contain costs may result in reduced resources allocated to the emergency care system because of the limitation of payment. Inadequate payment is clearly threatening the emergency care system in Taiwan [15,16]. Emergency medical services play a vital role in the public health system but the current insurance appears to be limiting the availability of emergency medicine to patients. Some policymakers have claimed that the low payment of ED is due to the inadequate use of emergency services [17,18]. Lambe S et al reported that critical visits per ED increased by 59% and non-urgent visits per ED decreased by 8% in California's EDs from 1990 to 1999 [2]. More importantly, delay in care of patients with emergency conditions may result in increased morbidity and mortality [12]. The 24-hour availability and concentration of resources may.

(6) 104. be the most cost-effective way to deliver acute care, regardless of the type of health care delivery system [19]. In addition, the true costs of nonurgent care in the ED are relatively low [20]. The copayment of EDs which have higher ambulatory care is a method to control the overuse of EDs. Hence, the NHI would not be able to use low payment to restrict non-urgent visits or "punish" emergency departments which receive large numbers of patients requiring critical and emergency care. In addition, for hospitals with small reserves, this payment decrease may precipitate closure of EDs and compromise the medical safety net in their region. There were some limitations in our study. First, the total costs of EDs were difficult to assess and calculate, so we only focused on the cost of physicians' salaries. Second, for some districts, not all of the EDs were included in the analyses; however, only a few EDs did not respond to our study and most of these were small EDs with a small number of ED visits. Finally, physicians' salaries and physician manpower were dynamic so data on physician cost comprised average values. The twin goals of health care reform, providing universal coverage and limiting health care costs, may have contradictory effects on the future demand for emergency physicians [17]. With greater expenditure control, EDs need to convey more assertively to policymakers the importance of availability of emergency services, which is after all a public good. Without adequate manpower or skilled staff, it is difficult to provide high quality emergency care. Low and unreasonable payment will inevitably affect the quality of care. It is clear that the payment system has a considerable impact on the development of emergency medical services. Consequently, EDs need to remodel their management strategies according to hospital level. Emergency departments in urban townships with a small number of visitors have less demand for services, so EDs in the same district need to integrate according to the population density in order to reduce costs and resolve the problem of having an inadequate number of ED physicians.. Payment and ED in Central Taiwan REFERENCES. 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in hospital emergency department utilization: United States, 1992-99. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 13, Number 150; November, 2001. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_13/sr13_150. pdf. Accessed March 29, 2003. 2. Lambe S, Washington DL, Fink A, et al. Trends in the use and capacity of California's emergency departments, 1990-1999. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39: 389-96. 3. Tsai AC, Tamayo-Sarver JH, Cydulka RK, et al. Declining payments for emergency department care, 1996-1998. Ann Emerg Med 2003;41:299-308. 4. Expenditures on GNP. Available at: http://www.dgbas. gov.tw/dgbas03/bs5/quarter/table5.xls. Accessed March 29, 2003. 5. National statistics: Available at: http://www.dgbas. gov.tw/dgbas03/bs4/table/table.xls. Accessed March 29, 2003. 6. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Growth of expenditure on health, total expenditure on health. Available at: http://www.oecd. org/dataoecd/1/31/2957323.xls. Accessed March 29, 2003. 7. Exchange rates of the New Taiwan (N.T.) dollar against the U.S. dollar (interbank spot market closing rates). Available at: http://www.cbc.gov.tw/EngHome/ eforeign/statistics/Eyearly.htm. Accessed February 3, 2003. 8. Sacchetti A, Harris RH, Warden T, et al. Contribution of ED admissions to inpatient hospital revenue. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:30-1. 9. Williams JM, Ehrlich PF, Prescott JE. Emergency medical care in rural America. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38:323-7. 10. Derlet RW, Young GP. Managed care and emergency medicine: conflicts, federal law, and California legislation. Ann Emerg Med 1997:30;292-300. 11. Williams RM. Distribution of emergency department costs. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28:671-6. 12. Young GP, Sklar D. Health care reform and emergency medicine. [Review] Ann Emerg Med 1995:25:666-74. 13. Derlet RW. Overcrowding in emergency departments: increased demand and decreased capacity. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:430-2. 14. Derlet R, Richards J, Kravitz R. Frequent overcrowding in US emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:151-5. 15. Gore L. Two major hospitals slated to close in Los.

(7) Wei-Kung Chen, et al.. Angeles; will reduce access to emergency care for all. Available at: http://www.acep.org/3,32249,0.html. Accessed Jan. 2003. 16. Fath JJ, Ammon AA, Cohen MM. Urban trauma care is threatened by inadequate reimbursement. Am J Surg 1999;177:371-4. 17. Shesser R, Kirsch T, Smith J, et al. An analysis of emergency department use by patients with minor illness. Ann Emerg Med 1991;20:743-8.. 105. 18. Kellermann AL. Nonurgent emergency department visits. Meeting an unmet need. JAMA 1994;271:19534. 19. Williams RM. Single-payer and all-payer systems: implications for emergency medicine in the United States. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:337-9. 20.Williams RM. The costs of visits to emergency departments. N Engl J Med 1996:334;642-6..

(8) 106. (. 1348. p < 0.05). 2005;10:99-106. 404. 2. 2004. 8. 5. 2005. 3. 15. 2005. 2. 18. 0.62.

(9)

數據

相關文件

In addition, based on the information available, to meet the demand for school places in Central Allocation of POA 2022, the provisional number of students allocated to each class

Holographic dual to a chiral 2D CFT, with the same left central charge as in warped AdS/CFT, and non-vanishing left- and right-moving temperatures.. Provide another novel support to

According to Ho (2003), Canto Pop “has developed since the early 1970s with a demand from Hong Kong audiences for popular music in their own dialect, Cantonese. Cantonese is one

b) Less pressure on prevention and reduction measures c) No need to be anxious about the possible loss.. Those risks that have not been identified and taken care of in the

The school practises small class teaching with the number of school places for allocation being basically 25 students per class. Subject to the actual need at the Central

In addition, based on the information available, to meet the demand for school places in Central Allocation of POA 2022, the provisional number of students allocated to each class

To enhance availability of composite services, we propose a discovery-based service com- position framework to better integrate component services in both static and dynamic

The Peunayong Downtown area is in need of rejuvenation because this area considered as the Central Business District (CBD) of Banda Aceh city which in turn supports