Title: Perinatal Risk Factors for Suicide in Young Adults in Taiwan

Authors: Ying-Yeh Chen1,2, David Gunnell3, Chin-Li Lu4, Shu-Sen Chang5, Tsung-Hsueh Lu4, Chung-Yi Li4*

1 Taipei City Psychiatric Center, Taipei City Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

2 Institute of Public Health and Department of Public Health, National Yang-Ming University,

Taipei, Taiwan

3School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

4 Department of Public Health, College of Medicine, National Cheng-Kung University, Tainan,

Taiwan

5 Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, The University of Hong

Kong, Hong Kong

Correspondence to Professor Chung-Yi Li

Graduate Institute and Department of Public Health National Cheng Kung University School of Medicine

#1, University Road, Tainan 70101, Taiwan

Tel: +886-6-2353535 Fax: +886-6-2359033

Conflict of interest: non-declared

Acknowledgements: Y-YC was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan (grant

number 101-2314-B-532-005-MY2) and the National Health Research Institute, Taiwan (grant

number NHRI-EX100-10024PC). DG is an NIHR senior investigator. S-SC was supported by

the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (HKU 784012M and HKU 784210M) and a grant from

The University of Hong Kong (Project Code 201203159017). The funding agency has no role in

Abstract word count:237 Text word count:3324 Reference word count:836 Abstract

Background:

We investigated the association of early life social factors, such as young maternal age, single

motherhood, lower socioeconomic position, and higher birth order with future risk of suicide in

Taiwan.

Method:

A nested case-control design, using linked data from Taiwan Birth Registry (1978-1993) and

Taiwan Death Registry (1993-2008), identified 3,984 suicides aged 15-30. For each suicide 30

age and sex matched controls were randomly selected, using density sampling technique.

Conditional logistic regression models were estimated to assess the association of early life risk

factors with suicide.

Results:

Younger maternal age (<25), single motherhood, lower paternal educational level and higher

birth order were independently associated with increased risk of suicide. Stratified analyses

suggest that lower paternal educational level was associated with male, but not female suicide

risk (P (interaction) =0.02). Single motherhood was a stronger risk factor for suicide in female

than in male offspring (OR [95% Confidence Interval (CI)] = 2.30 [1.47, 3.58] vs. OR [95%CI]

sibship size (>=4 siblings), the excess in suicide risk was greater among later born daughters

compared to later born sons (P (interaction) = 0.05).

Conclusions:

Our findings provide support for the influence of early life social circumstances on future risk

of suicide in an Asian context. Cultural specific factors, such as a preference for male offspring,

Introduction

Previous studies in European populations have shown that social circumstances around the

time of birth, such as young maternal age, lower socioeconomic position (SEP), single

motherhood and higher birth order are associated with an increased risk of suicide.1-5 Single

motherhood, lower SEP and young maternal age are indicators of a potentially adverse childhood

environment; these adverse early life experiences may lead to increased susceptibility to

substance abuse, alcohol misuse, mental disorders and suicide.4,6 Higher birth order (i.e. having

older siblings) is an indicator of large family size and hence increased competition for resources

and parental attention.4,7 It is theorized that compared to children of higher birth order, first born

have their parents’ undivided attention at least in the first year of life this may help them develop

greater resilience to stressful events in adulthood.8 Additionally, higher birth order may be

related to increased maternal stress during pregnancy due to childcare responsibilities and the

economic consequences of having a large family, which may subsequently elevate the risk of

maternal depression, a known risk factor for offspring suicide.3,6

Evidence of the impact of perinatal psychosocial circumstances and risk of suicide has

generally come from European studies. To the best of our knowledge, no studies from

non-Western countries have investigated this issue. It is well known that the epidemiology of suicide

as well as its common risk and protective factors differ in Eastern and Western countries.9 The

stronger intergenerational ties in Asian people may lead to different patterns of childcare practice

compared to the West.10 In addition, the Confucianism cultural attitude of preferring sons to

daughters and hierarchical family relations may result in differential family resources and roles

prescribed to children according to their gender and birth order.11,12 Hence, the set of perinatal

context. Analysis of the relationship between perinatal circumstances and suicide within Asian

populations may provide new insights into the nature of these associations.

We used linked Taiwanese national birth and death registry data to conduct a population based

nested case-control study to investigate the associations of perinatal circumstances with suicide

risk in Taiwan.

Methods:

Source of data

This study is based on linkage of the Taiwan Birth Registry (1978-1993) with the Taiwan Death

Registry (1993-2008) using National Identification Numbers. In Taiwan, it is a legal requirement

that all live births and deaths be registered within 10 days. Various birth characteristics including

gender, birth weight, gestational age, single/multiple birth, birth order, parental ages, education

and mother’s marital status are available for each live birth in the Taiwan Birth Registry. Data

quality for both the Taiwan Birth Registry and Taiwan Death Registry have been evaluated and

they are considered valid and complete.13,14 Access to the birth and death registries was approved

by the Department of Health.

Nested case-control design

This study was based on a cohort consisting of all 5,654,833 live births registered in Taiwan

between 1978 and 1993. By the end of 2008, we identified 3,984 suicides aged 15 years or above

during 1993-2008. For each case, we randomly selected 30 controls using the density sampling

alive at the date of suicide. By doing so, an individual could be selected as a control before

he/she became a suicide case. Besides, an individual could serve as a control for multiple cases.

The density sampling finally ended up with a total of 119,520 controls.

Outcome variable:

The outcome variable was suicide. Deaths certified as undetermined intent, accidental

poisoning by pesticide or accidental suffocation were also included because previous research

indicates that many deaths included in these categories are likely to be missed suicides.16 A total

of 3,984 young adults who died from suicide (International Classification of Diseases, ninth

revision [ICD-9] codes E950-E959) (N=3217), undetermined intent (E980-E989) (N=708),

accidental poisoning by pesticide (E863) (N=40) or accidental suffocation (E913) (N=19) were

identified between 1993 and 2008. We carried out sensitivity analyses based on data for certified

suicides only to investigate the impact of including these possible missed suicides and results

were generally unchanged.

Risk factors investigated:

Independent variables included single motherhood, parental SEP, maternal age and birth

order. If the registered maternal marital status at birth was recorded as single, divorced or

widowed, this was used as a proxy for ‘single motherhood’. In keeping with previous studies,

parental educational attainment was used to indicate SEP, which was categorized into elementary

or less (≦6 years education), junior high (7-9 years), senior high (10-12 years) and college or more (>12 years); maternal and paternal educational attainment were analyzed separately.

Maternal age was grouped into five categories: <20, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34 and >=35 years.

We first described the distribution of risk factors in cases and controls. We then analyzed data

using conditional logistic regression models and estimated odds ratios and their 95% confidence

intervals. Crude odds ratios were estimated from simple conditional logistic regression that takes

into account the matching variables including age, gender, and date of suicide in the analysis. We

then adjusted for all the risk factors investigated in the conditional logistic regression model.

Further adjustment for biological factors -- birth weight, gestational age and place of birth

(metropolitan areas, small cities/town and rural areas) were also conducted as these factors may

be related to suicide as well as the perinatal risk factors. We investigated if the association of

perinatal psychosocial risk factors differed in males and females by fitting appropriate interaction

terms. Gender stratified analyses were subsequently conducted since we found evidence for

gender differences.

The effect of birth order may be related to sibship size, i.e. the adverse effect of higher birth

order reflects higher parental care burden or greater competition for resources in larger families,

rather than the disadvantage of higher birth order per se. To disentangle the role of birth order vs.

family size, we developed a subset of the data by excluding mothers who had a further child

during 1994-2003. Since the age difference between two siblings in Taiwan is rarely over 10

years, after excluding these mothers, we were able to estimate sibship size using the birth order

of the last child born to a mother. In other words, we assumed that if a mother did not give birth

to any children in the 10 year period (1994-2003) the likelihood that she had more children

afterwards was very small. Using this data subset, we stratified families into different sibship

size to estimate the effect of birth order.

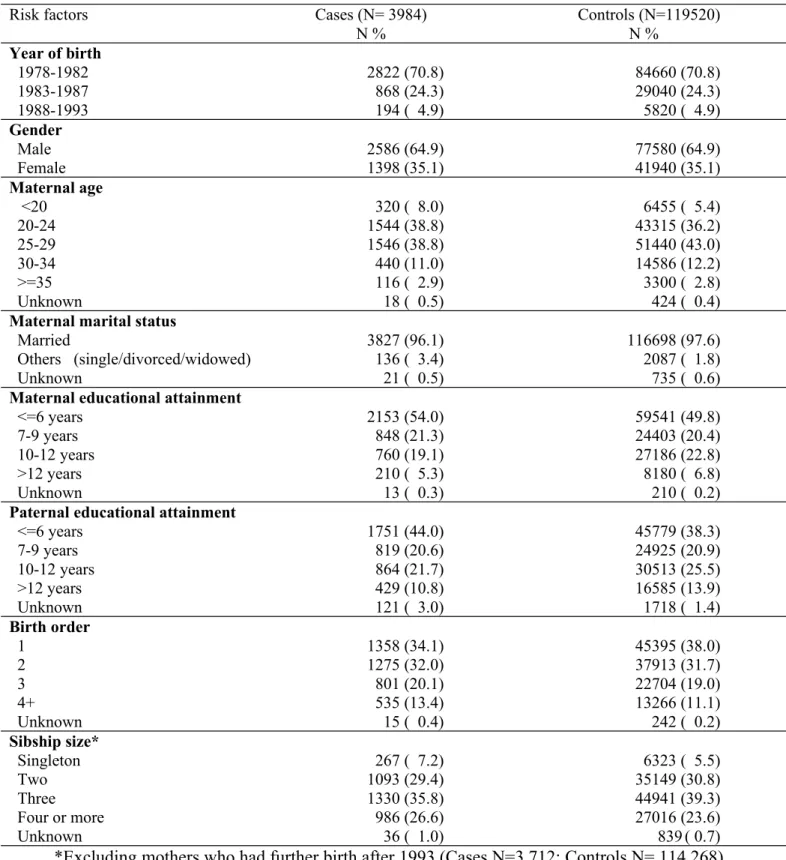

The distributions of the sociodemographic variables in 3984 suicide cases (2586 males and

1398 females) and 119,520 controls (77580 males and 41940 females) are presented in table 1.

Compared to controls, cases tended to have higher proportions of young maternal age (<20

years), not married (an indicator of single motherhood), lower parental educational attainment. In

addition, the proportion of being the first born children was also lower among cases. Complete

risk factor data were available for >95% of the sample, we conducted the analyses based on all

the available data.

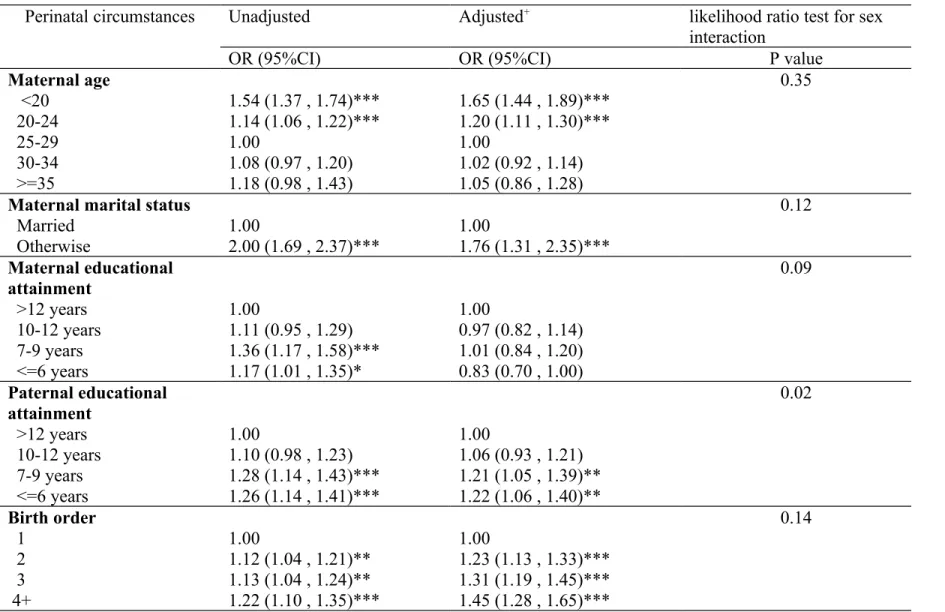

The risks of suicide in relation to perinatal factors are shown in table 2. Univariable analyses

revealed that children born to younger mothers, mothers who were not married at the time of

delivery, mothers or fathers whose educational attainment was less than 10 years and children of

higher birth order were at increased risk of suicide by the age of 30 years. The adjusted model

included all perinatal risk factors in the model. Compared to children born to mothers who were

25-29 years, children born to mothers younger than 20 years of age were 1.65 times more likely

to die by suicide (95% confidence interval [CI]= 1.44, 1.89). The effect of maternal marital

status somewhat weakened in the adjusted model. After adjusting for other risk factors, we

observe a significant and graded relationship between lower paternal educational level and

increased risk of offspring suicide (trend test P<.0001); associations with maternal educational

attainment however, disappeared in the adjusted model. Later born children were at increased

risk of suicide when compared to their first born siblings. The relationship between birth order

and suicide was graded, the higher the birth order, the greater the risk of suicide (trend test P < .

0001). We further assessed the effect of the relationship between perinatal circumstances and

suicide, controlling additional variables including birth weight, gestational age and place of birth;

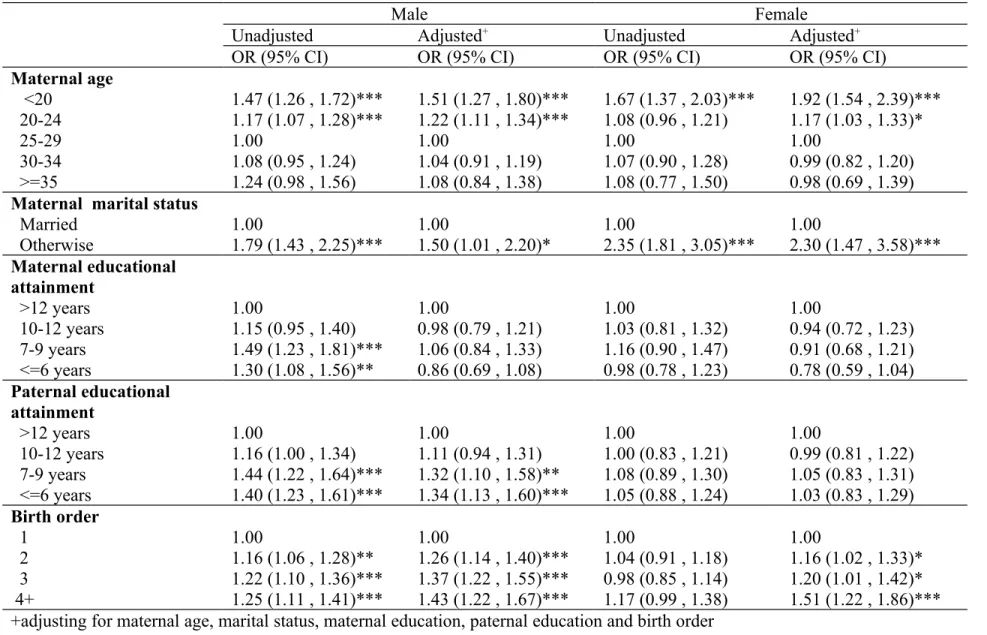

There was some evidence of gender differences in associations with perinatal risk factors and

suicide (p (interaction) values ranged between 0.02-0.35) (Table 2). Stratified analyses by gender

showed that single motherhood was associated with greater increased risk of suicide in daughters

(adjusted OR [95% CI] = 2.30 [1.47, 3.58]) than in sons (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 1.50 [1.01,

2.20]) (Table 3). Paternal educational level of 6 years or less was associated with increased risk

of suicide in sons (adjusted OR [95% CI] =1.34 [1.13, 1.60]) but not in daughters (adjusted OR

[95% CI] =1.03 [0.83, 1.29]). Maternal education was not related to son’s or daughter’s suicide

when other risk factors were controlled for. The beneficial effect of being a first born child was

observed in both genders. Regardless of gender, a graded effect of increasing risk of suicide in

children of higher birth order was observed (trend test, male P<.0001, female P=0.0096)

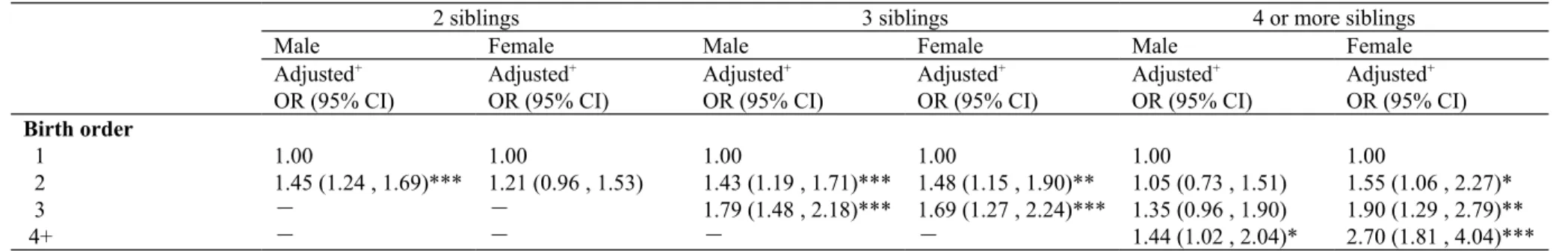

The subset data analysis (i.e. excluding mothers who had further child after 1993) stratified

by gender and number of siblings in a household is shown in Table 4. The results still revealed a

graded association between birth order and suicide risk in families, regardless of sibship size.

Although gender interactions were not significant for sibship size stratified models (p

(interaction) = 0.22, 0.88 and 0.20 respectively for sibship size of 2, 3 and 4 or more), there was

some evidence suggesting a greater increased risk of suicide in later born daughters (birth order 4

or higher) in families of larger sibship size (4 or more) (OR [95% CI] = 2.70 [1.81, 4.04]),

compared to their male counterparts (OR [95% CI]= 1.44 [1.02, 2.04]); P (interaction) = 0.05).

Discussion

In this large nested case control study we found early perinatal risk factors for suicide in an

Asian population of young adults are similar to previous reports from Western countries. Young

maternal age, single motherhood, lower paternal SEP at the time of delivery and higher birth

order were associated with increased risk. In gender stratified analysis, as in previous reports,

males appear to be more sensitive to the adverse effects of low SEP than females.17,18 Unlike

patterns of risk seen in Western countries, we found some evidence that that single motherhood

was a stronger risk factor of suicide in female than in male offspring. Furthermore, in families

with large sibship size (4 siblings or more), there was evidence that later born daughters had a

higher risk of suicide, whereas the excess risk of suicide for later born sons was not as prominent

as their female counterparts. However, this later association should be interpreted with caution as

it is a subgroup finding and no evidence of such an association in families with sibship size of 2

or 3.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study in a non-Western context to explore early life risk factors for suicide. The

use of a large (N=3,984 suicide) and representative sample over a long follow up period (15-30

years) yielding valuable information on early life course determinants of future suicide risk in a

setting where no such study has been conducted before.

Our results should be interpreted in light of the limitation that only register-based data were

available. We were not able to assess possible underlying mechanisms, such as mental illness

and adult SEP. Also we had to use available variables as proxies for some of the social factors

we investigated. For example, not married at delivery was used to indicate single motherhood

birth registry data did not contain a family identifier, sibship size was estimated by the birth

order of a woman’s last born child, changes in sibship size due to divorce, re-marriage or

widowhood were not considered in our analysis. Lastly our analysis is restricted to suicides

occurring in the first 30 years of life, findings may not be generalisable to suicide occurring later

in the life course.

Interpretations

Our results suggest that an individual’s risk of suicide may be influenced by factors operating

early in the life course. There are several possible mechanisms underlying these associations.

First, early adversities as indicated by young maternal age, single motherhood, low SEP and

higher birth order, are associated with increased level of stress in pregnant mothers. Maternal

stress may affect fetal brain development through alterations in central corticotrophin hormone

(CRH) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene methylation;19 these epigenetic changes may then

lead to sustained neurobiological alterations of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which may

have long term influence on mental health and psychosocial development of the children.20,21

Second, the perinatal psychosocial disadvantage may also result in inadequate nutritional supply

on the developing brain, children born to teenage mothers, high-parity mothers, or families of

lower SEP may be particularly susceptible to malnutrition. Evidence regarding the link between

prenatal malnutrition and mental disorders is accumulating.22 Overall, environmental adversities

in pre- and early postnatal life may have life-long psychological consequences; the fetal brain

may be ‘programmed’ by these socio-environmental disadvantages.23 Third, perinatal

disadvantages usually do not only occur at one point in time; early exposure to adverse

suicide.24,25 For example, children born to teenage single mothers who had very limited skills and

educational attainment may experience low quality parenting, frequent residential mobility and

inadequate access to social and human capital; these may lead to greater exposure to frustration,

less resources and limited coping skills to deal with them.26

The set of perinatal risk factors for future risk of suicide found in the Asian population in

Taiwan are consistent with those identified in studies from the West. However, some of the

gender stratified analyses suggested that cultural factors may shape these associations. The

finding that the excess risk of suicide was greater among girls than boys born to single mothers is

somewhat different from observations in the West. Studies from the West tend to suggest that

girls seemed to fare better than boys growing up with a single mother in terms of outcomes

related to conduct problems, social relations and academic performance.27,28 For suicide

outcomes, studies comparing the gender-specific risk in offspring born to a single mother are

scarce. One Northern Finland cohort showed that single parent families were associated with

increased risk of suicide attempt in male offspring (OR [95% CI] = 5.46 [2.64, 11.29]) but not in

female (OR [95%CI]=0.42 [0.58, 3.05]); in this cohort however, there was no gender differences

in the association between single parent family and future risk of suicide.29 Possible explanations

for the adverse outcomes found in boys born to a single mother include the absence of male role

model and inadequate parental supervision (which may be more needed in boys than in girls).28

In the Asian context, although offspring of single mothers were at increased suicide risk in both

genders, girls were at greater risk than boys. It is possible that the cultural attitude of favoring

male offspring may somewhat attenuate risk in boys, as the birth father or his family are more

willing to provide support for a son born out of wedlock whereas a daughter born out of wedlock

birth out of wedlock in Taiwanese context - less than 2% of our control subjects were born to

unmarried mothers; corresponding figures were 20% in one Swedish cohort,31 33% in a Danish

cohort6 and 15% in a Norwegian cohort5. Although this speaks to a more stable family structure

in Taiwan, this may also indicate greater level of stigmatization towards single mothers. The

effect estimates for the impact of single motherhood on offspring suicide risk compared to

European cohorts were somewhat greater in our study; the estimated OR was 1.76 (95% CI:

1.31, 2.35) in our sample, the equivalent figures were 1.30 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.72) in Denmark6 and

1.32 (95% CI: 0.66-2.66) in Sweden31. The socially unacceptable role of being a single mother

may make the role modeling process extremely difficult for a daughter born out of wedlock in

Taiwan.

The findings that later born girls in a large sibship family were at particular risk of suicide

may also be related to the culture system of favoring male offspring in East Asia. The norms

prescribed for children in East Asia Confucianism culture are based on both their seniority and

gender.12 Specifically, the ultimate authority within the Confucianism family is supposed to be

passed from the father to the eldest son. The cultural practice of ancestor worship was

strenuously promoted as a means of strengthening the transmission of patrilineality.11,32 It is

believed that only sons can be responsible for worshiping/paying the respects to their ancestors,

in doing this, they bring good fortune to the family. Although economic development,

modernization and the rise of women’s status has gradually transformed the Confucianism

patriarchal social system in Taiwan, families with larger sibship size tended to be the ones who

deeply believed and practiced the cultural system of patrilineality.11,32 They either wanted a son

observed risk difference for later born daughters and sons in large sibship families in Taiwan

may be related to these cultural factors.

Despite the cultural system of favoring male offspring, first born daughters still benefit from

their birth order. A recent study in Taiwan found that educational outcomes were related to

sibship size and birth order; given the same family SEP, the educational attainment for first born

boys tended to be higher compared to other siblings, but the beneficial effect was not found in

firstborn daughters.12 In other words, firstborn daughters did not as benefit as much as firstborn

sons in terms of competing for familial educational resources in Taiwan. It is possible that the

family system of gender and birth order interaction is outcome dependent. Some outcomes (such

as suicide) may be related to very early environmental advantages /disadvantages (e.g. getting

undivided parental attention); some outcomes (such as education) may be associated with

parental investment during adolescent periods. However, we should be cautious in interpreting

the results derived from the stratified analyses, as they were based on small sample sizes.

The findings that lower paternal SEP affected suicide risk in male offspring but not female

offspring were in line with previous findings that the strength of association between SEP and

suicide risk was stronger in men than in women.17,18,33 As men are still considered as the main

economic providers in our society, economic hardships may impose greater stress on men than

on women.

Conclusion

Our results provide support for the impact of early life adversities on risk of suicide by age of

30 years in an Asian context where no such type of study has been conducted before. The

in a large size family provide evidence to the culture influences in shaping suicide risk. The

results suggest the need to embrace a life-course perspective in preventing suicide.

References:

1. Gravseth HM, Mehlum L, Bjerkedal T, Kristensen P. Suicide in young Norwegians in a life

course perspective: population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health

2010;64:407-12.

2. Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Rasmussen F, Wasserman D. Restricted fetal growth and adverse

maternal psychosocial and socioeconomic conditions as risk factors for suicidal behaviour

of offspring: a cohort study. Lancet 2004;364:1135-40.

3. Riordan DV, Selvaraj S, Stark C, Gilbert JS. Perinatal circumstances and risk of offspring

suicide. Birth cohort study. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:502-7.

4. Riordan DV, Morris C, Hattie J, Stark C. Family size and perinatal circumstances, as mental

health risk factors in a Scottish birth cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol

2012;47:975-83.

5. Bjørngaard JH, Bjerkeset O, Vatten L, Janszky I, Gunnell D, Romundstad P. Maternal age

at child birth, birth order and suicide at a young age – a sibling comparison. Am J

Epidemiol 2012. (in press)

6. Agerbo E, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Familial, psychiatric, and socioeconomic risk

factors for suicide in young people: nested case-control study. BMJ 2002;325:74.

7. Lawson DW, Mace R. Sibling configuration and childhood growth in contemporary British

families. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:1408-21.

8. Lutha SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social

policies. Dev Psychopathol 2000;12:857-85.

9. Chen YY, Wu KCC, Yousuf S, Yip PSF. Suicide in Asia: opportunities and challenges.

10. Chen F, Liu G, Mair CA. Intergenerational ties in context: grandparents caring for

grandchildren in China. Social Force 2011;90:571-94.

11. Chung W, Gupta MD. The decline of son preference in South Korea: the roles of

development and public policy. Popul Dev Rev 2007;33:757-83.

12. Yu WH, Su KH. Gender, sibship structure, and educational inequality in Taiwan: son

preference revisited. J Marriage Fam 2006;68:1057-68.

13. Lin CM, Lee PC, Teng SW, Lu TH, Mao IF, Li CY. Validation of the Taiwan Birth

Registry using obstetric records. J Formos Med Assoc 2004;103:297-301.

14. Lu TH, Lee MC, Chou MC. Accuracy of cause-of-death coding in Taiwan: types of

miscoding and effects on mortality statistics. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:336-43.

15. Greenland S, Thomas DC. On the need for the rare disease assumption in case-control

studies. Am J Epidemiol 1982;116:547-53.

16. Chang SS, Sterne JA, Lu TH, Gunnell D. 'Hidden' suicides amongst deaths certified as

undetermined intent, accident by pesticide poisoning and accident by suffocation in Taiwan.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:143-52.

17. Andres AR, Collings S, Qin P. Sex-specific impact of socio-economic factors on suicide

risk: a population-based case-control study in Denmark. Eur J Public Health

2010;20:265-70.

18. Koskinen S, Martelin T. Why are socioeconomic mortality differences smaller among

women than among men? Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1385-96.

19. Turecki G, Ernst C, Jollant F, Labonte B, Mechawar N. The neurodevelopmental origins of

20. O'Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Beveridge M, Glover V. Maternal antenatal anxiety and

children's behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Report from the Avon Longitudinal

Study of Parents and Children. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:502-8.

21. Gitau R, Cameron A, Fisk NM, Glover V. Fetal exposure to maternal cortisol. Lancet

1998;352:707-8.

22. Neugebauer R. Accumulating evidence for prenatal nutritional origins of mental disorders.

JAMA 2005;294:621-3.

23. Raikkonen K, Pesonen AK, Roseboom TJ, Eriksson JG. Early determinants of mental

health. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;26:599-611.

24. Power C, Manor O, Matthews S. The duration and timing of exposure: effects of

socioeconomic environment on adult health. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1059-65.

25. Gunnell D, Lewis G. Studying suicide from the life course perspective: implications for

prevention. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187:206-8.

26. Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne BJ et al. Association between children's experience of

socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: a life-course study. Lancet 2002;360:1640-5.

27. Amato PR. Children of divorce in the 1990s: an update of the Amato and Keith (1991)

meta-analysis. J Fam Psychol 2001;15:355-70.

28. Krein SF, Beller AH. Educational attainment of children from single-parent families:

differences by exposure, gender, and race. Demography 1988;25:221-34.

29. Alaraisanen A, Miettunen J, Pouta A, Isohanni M, Rasanen P, Maki P. Ante- and perinatal

circumstances and risk of attempted suicides and suicides in offspring: the Northern Finland

birth cohort 1966 study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012;47:1783-94.

functioning, social support and life adjustment problems among single-parent adolescents

from an ecological perspective. Taipei, Taiwan, National Science Council, 1993. Available

at:http://nccur.lib.nccu.edu.tw/bitstream/140.119/4923/1/912412H004011SSS.pdf

(Accessed 01 December, 2012)

31. Danziger PD, Silverwood R, Koupil I. Fetal growth, early life circumstances, and risk of

suicide in late adulthood. Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26:571-81.

32. Deuchler M. The Confucian Transformation of Korea: A Study of Society and Ideology.

Cambridge, MA, Council on East Asia Studies, Harvard University (Harvard-Yenching

Institute Monograph Series 36), 1992.

33. Page A, Morrell S, Taylor R. Suicide differentials in Australian males and females by

various measures of socio-economic status, 1994-98. Aust N Z J Public Health

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the suicide cases and controls

Risk factors Cases (N= 3984)

N % Controls (N=119520) N % Year of birth 1978-1982 1983-1987 1988-1993 2822 (70.8) 868 (24.3) 194 ( 4.9) 84660 (70.8) 29040 (24.3) 5820 ( 4.9) Gender Male Female 2586 (64.9) 1398 (35.1) 77580 (64.9) 41940 (35.1) Maternal age <20 20-24 25-29 30-34 >=35 Unknown 320 ( 8.0) 1544 (38.8) 1546 (38.8) 440 (11.0) 116 ( 2.9) 18 ( 0.5) 6455 ( 5.4) 43315 (36.2) 51440 (43.0) 14586 (12.2) 3300 ( 2.8) 424 ( 0.4)

Maternal marital status

Married Others (single/divorced/widowed) Unknown 3827 (96.1) 136 ( 3.4) 21 ( 0.5) 116698 (97.6) 2087 ( 1.8) 735 ( 0.6)

Maternal educational attainment

<=6 years 7-9 years 10-12 years >12 years Unknown 2153 (54.0) 848 (21.3) 760 (19.1) 210 ( 5.3) 13 ( 0.3) 59541 (49.8) 24403 (20.4) 27186 (22.8) 8180 ( 6.8) 210 ( 0.2)

Paternal educational attainment

<=6 years 7-9 years 10-12 years >12 years Unknown 1751 (44.0) 819 (20.6) 864 (21.7) 429 (10.8) 121 ( 3.0) 45779 (38.3) 24925 (20.9) 30513 (25.5) 16585 (13.9) 1718 ( 1.4) Birth order 1 2 3 4+ Unknown 1358 (34.1) 1275 (32.0) 801 (20.1) 535 (13.4) 15 ( 0.4) 45395 (38.0) 37913 (31.7) 22704 (19.0) 13266 (11.1) 242 ( 0.2) Sibship size* Singleton Two Three Four or more Unknown 267 ( 7.2) 1093 (29.4) 1330 (35.8) 986 (26.6) 36 ( 1.0) 6323 ( 5.5) 35149 (30.8) 44941 (39.3) 27016 (23.6) 839 ( 0.7) *Excluding mothers who had further birth after 1993 (Cases N=3,712; Controls N= 114,268)

Table 2: Association between perinatal circumstances and risk of suicide

Perinatal circumstances Unadjusted Adjusted+ likelihood ratio test for sex

interaction

OR (95%CI) OR (95%CI) P value

Maternal age <20 20-24 25-29 30-34 >=35 1.54 (1.37 , 1.74)*** 1.14 (1.06 , 1.22)*** 1.00 1.08 (0.97 , 1.20) 1.18 (0.98 , 1.43) 1.65 (1.44 , 1.89)*** 1.20 (1.11 , 1.30)*** 1.00 1.02 (0.92 , 1.14) 1.05 (0.86 , 1.28) 0.35

Maternal marital status

Married Otherwise 1.00 2.00 (1.69 , 2.37)*** 1.00 1.76 (1.31 , 2.35)*** 0.12 Maternal educational attainment >12 years 10-12 years 7-9 years <=6 years 1.00 1.11 (0.95 , 1.29) 1.36 (1.17 , 1.58)*** 1.17 (1.01 , 1.35)* 1.00 0.97 (0.82 , 1.14) 1.01 (0.84 , 1.20) 0.83 (0.70 , 1.00) 0.09 Paternal educational attainment >12 years 10-12 years 7-9 years <=6 years 1.00 1.10 (0.98 , 1.23) 1.28 (1.14 , 1.43)*** 1.26 (1.14 , 1.41)*** 1.00 1.06 (0.93 , 1.21) 1.21 (1.05 , 1.39)** 1.22 (1.06 , 1.40)** 0.02 Birth order 1 2 3 4+ 1.00 1.12 (1.04 , 1.21)** 1.13 (1.04 , 1.24)** 1.22 (1.10 , 1.35)*** 1.00 1.23 (1.13 , 1.33)*** 1.31 (1.19 , 1.45)*** 1.45 (1.28 , 1.65)*** 0.14

Table 3: Sex-stratified analysis for the association between perinatal circumstances and risk of suicide

Male Female

Unadjusted Adjusted+ Unadjusted Adjusted+

OR (95% CI) OR (95% CI) OR (95% CI) OR (95% CI)

Maternal age <20 20-24 25-29 30-34 >=35 1.47 (1.26 , 1.72)*** 1.17 (1.07 , 1.28)*** 1.00 1.08 (0.95 , 1.24) 1.24 (0.98 , 1.56) 1.51 (1.27 , 1.80)*** 1.22 (1.11 , 1.34)*** 1.00 1.04 (0.91 , 1.19) 1.08 (0.84 , 1.38) 1.67 (1.37 , 2.03)*** 1.08 (0.96 , 1.21) 1.00 1.07 (0.90 , 1.28) 1.08 (0.77 , 1.50) 1.92 (1.54 , 2.39)*** 1.17 (1.03 , 1.33)* 1.00 0.99 (0.82 , 1.20) 0.98 (0.69 , 1.39)

Maternal marital status

Married Otherwise 1.001.79 (1.43 , 2.25)*** 1.001.50 (1.01 , 2.20)* 1.002.35 (1.81 , 3.05)*** 1.002.30 (1.47 , 3.58)*** Maternal educational attainment >12 years 10-12 years 7-9 years <=6 years 1.00 1.15 (0.95 , 1.40) 1.49 (1.23 , 1.81)*** 1.30 (1.08 , 1.56)** 1.00 0.98 (0.79 , 1.21) 1.06 (0.84 , 1.33) 0.86 (0.69 , 1.08) 1.00 1.03 (0.81 , 1.32) 1.16 (0.90 , 1.47) 0.98 (0.78 , 1.23) 1.00 0.94 (0.72 , 1.23) 0.91 (0.68 , 1.21) 0.78 (0.59 , 1.04) Paternal educational attainment >12 years 10-12 years 7-9 years <=6 years 1.00 1.16 (1.00 , 1.34) 1.44 (1.22 , 1.64)*** 1.40 (1.23 , 1.61)*** 1.00 1.11 (0.94 , 1.31) 1.32 (1.10 , 1.58)** 1.34 (1.13 , 1.60)*** 1.00 1.00 (0.83 , 1.21) 1.08 (0.89 , 1.30) 1.05 (0.88 , 1.24) 1.00 0.99 (0.81 , 1.22) 1.05 (0.83 , 1.31) 1.03 (0.83 , 1.29) Birth order 1 2 3 4+ 1.00 1.16 (1.06 , 1.28)** 1.22 (1.10 , 1.36)*** 1.25 (1.11 , 1.41)*** 1.00 1.26 (1.14 , 1.40)*** 1.37 (1.22 , 1.55)*** 1.43 (1.22 , 1.67)*** 1.00 1.04 (0.91 , 1.18) 0.98 (0.85 , 1.14) 1.17 (0.99 , 1.38) 1.00 1.16 (1.02 , 1.33)* 1.20 (1.01 , 1.42)* 1.51 (1.22 , 1.86)*** +adjusting for maternal age, marital status, maternal education, paternal education and birth order

OR: Odds Ratio, * p<.05, ** p<.01, ***p<.001

Table 4: Associations between birth order and risk of suicide stratifying by sex and sibship size

2 siblings 3 siblings 4 or more siblings

Male Female Male Female Male Female

Adjusted+ OR (95% CI) Adjusted+ OR (95% CI) Adjusted+ OR (95% CI) Adjusted+ OR (95% CI) Adjusted+ OR (95% CI) Adjusted+ OR (95% CI) Birth order 1 2 3 4+ 1.00 1.45 (1.24 , 1.69)*** - - 1.00 1.21 (0.96 , 1.53) - - 1.00 1.43 (1.19 , 1.71)*** 1.79 (1.48 , 2.18)*** - 1.00 1.48 (1.15 , 1.90)** 1.69 (1.27 , 2.24)*** - 1.00 1.05 (0.73 , 1.51) 1.35 (0.96 , 1.90) 1.44 (1.02 , 2.04)* 1.00 1.55 (1.06 , 2.27)* 1.90 (1.29 , 2.79)** 2.70 (1.81 , 4.04)*** +adjusting for maternal age, maternal marital status, maternal and paternal educational attainment