The Pragmatics of Focus in Tsou and Seediq

*Shuanfan Huang

National Taiwan UniversityThe discourse pragmatics of the focus systems of Seediq and Tsou, two Formosan languages spoken in the central highlands of Taiwan, which belong to two different primary branches of the Austronesian family, are investigated within the framework of quantitative discourse analysis. It is shown that although both Tsou and Seediq share a Philippine-style focus system, the ways their respective focus systems are deployed in discourse contexts are radically different. While the pragmatics of the focus system in Tsou behaves much more like what is known about Tagalog and other languages of the Philippines, the discourse properties of focus in Seediq show considerable difference, with the conversational data in particular showing even greater divergence from the ‘expected’ behavior. Specifically, it is shown that no pragmatic difference appears to underlie the choice between agent focus and non-agent focus clauses in the language. Neither discourse transitivity nor grounding can be shown to be a significant determinant for the choice of focus. Furthermore, the deployment of NAF in Seediq correlates with neither referential distance nor topic persistence. These and other results in the literature suggest that the focus systems in Western Austronesian languages may be seen to form a continuum and that the notion of focus contains no category-wide properties and must be best understood as a term with family resemblance properties. Finally, a plausible scenario of the diachronic development from a transitivity-dominated language like Tsou or Tagalog to a thematicity-dominated language like Modern Malay or Sasak is suggested.

Key words: discourse pragmatics, focus, grounding, transitivity-dominated, thematicity-dominated

1. Introduction

Focus in Austronesian linguistics has long constituted a ‘problem’ for a theory of voice in general linguistics. With recent expansion of interest in language universals, the

* Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the First International Symposium on Discourse

and Syntax in Chinese and Formosan Languages at National Taiwan University on June 14-15,1997, the Seventh Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association at Free University in Amsterdam on May 11-13, 1999, and at the Symposium on Selected NSC Projects in General Linguistics at National Taiwan University on June 9-10, 2001. I wish to thank the audiences at

666

problematic implications have only been heightened. The sharpness with which the focus system stands opposed to the more familiar voice system poses a challenge to the view that all languages are built on one universal archetype. Researchers have of course long wondered at the function of the structural focus in Austronesian languages. Why does such a system exist at all? What motivates its genesis? What discourse-pragmatic functions does it serve? How are these functions distinguished from the more familiar voice functions? The term ‘focus’ is surely indicative of a preliminary explanation. The idea has been, at least until recently, that the focused NP in Austronesian languages not only functions as syntactic pivot for relativization and verb serialization, but also has the pragmatic effect of highlighting it as the center of attention in a clause. We now know that, based on recent research, this much is an inaccurate characterization of focus.

The focus problems, then, have thus sat unresolved at the center of Austronesian linguistics for the past thirty years. Part of the problem lies in the fact that the pragmatics of focus in the Formosan languages has not been sufficiently researched. The present paper is an attempt to investigate the pragmatics of focus in two Formosan languages, Seediq and Tsou, from the perspective of the current discourse-theoretic framework. I will show that while the deployment of the focus system in Tsou shows striking similarities to that of Tagalog and other languages of the Philippines, the pragmatics of focus in Seediq does not correlate with either transitivity or topicality and thus shows interesting similarities to Standard Jarkata Indonesian or Sasak (Wouk l999). Although both Tsou and Seediq share a Philippine-style focus system, the ways their respective focus systems are deployed in discourse contexts are radically different.

Both Tsou and Seediq have a Philippine-style focus system, a system of verbal affixation which allows the different arguments to be placed in “subject” position, thereby marking them as identifiable and which signals the presence of a particular semantic role associated with the subject. The focus system has also been referred to in the literature as a voice system or a trigger system (cf. Shibatani 1988, Cumming et al. 1987, Wouk 1996). The term ‘trigger’ is used by some researchers to eschew a possible incorrect identification of the focused NP in the Austronesian languages with a constituent that represents the center of attention in the usage of non-Austronesianists and is thus meant to suggest that it is different semantic roles of the NPs (in Austronesian

these conferences for their comments. I have also benefited from helpful discussions with Susanna Cumming, Nicholas Himmelmann, Lily Su and Sandy Thompson on a number of points addressed in the paper. The final version of the paper, in particular, has been significantly improved, thanks to extremely valuable comments by two anonymous reviewers. I am also very grateful to the Seediq and Tsou speakers who so generously shared their expertise: Dakis Pawan and Temi Nawi (Seediq), Mo’o ‘e Peongsi, Tibusungu ‘e Peongsi, Pasuya ‘e Noacachiana, and Pasuya ‘e Naeavaina (Tsou).

667

languages) that trigger the choice of different morphology on the verb. In this paper, however, in deference to the tradition of Formosan linguistics, I will continue to use the term focus, as long as the above caveat is kept in mind.

Of the two languages investigated in this paper, Seediq is the more conservative in focus morphology—it reflects the reconstructed PAN affixes (AF m-, -m-, PF -un, LF -an, IF/BF si-) preserved also in many other Formosan Languages. Non-Agent focus affixes in Tsou are PF -a, LF -i, IF/BF -(n)eni, which are believed to have derived from the forms of the Proto-Austronesian atemporals (Ross l995). Although Tsou and Seediq are both focus languages, my study suggests that the pragmatics of focus in Seediq and Tsou shows considerable differences between the two, and that it is in fact Tsou that is the more conservative in this regard since it has retained more of the discourse features common to both Formosan and Philippine-type languages with respect to their focus systems.

2. Data and methodology

This study is based on a corpus of narratives and conversations by speakers of Tsou and Seediq. Narrative data are based on retellings of the Pear film and other folktales and conversational data come from conversations between friends or family members in natural settings.

The Seediq corpus comprises six Pear narratives and three conversations, plus elicitation notes, collected over a two-year period between November 1996 and June 1998. The dialect described here is Paran. The total Seediq population is about 26,000, while the Paran dialect has only about 2,500 speakers. The Paran dialect region where I did my field work consists of a string of villages located in a valley surrounded on the north and south sides by steep rolling hills, part of the rugged, powerful Central Mountain Range that dominates the landscape. From this area, known as Gluban, the nearest town, Puli, is ten miles to the east, which the villagers can get to by car, bus, or motorcycle.

The Tsou corpus consists of three Pear narratives, two folktales, and two conversations, plus elicitation work, collected between October l998 and December 2000. There are about 5,000 speakers of Tsou distributed among three major dialects and the dialect described here is the Tfuya dialect. In both Tsou and Seediq, only main, declarative clauses were used for the various calculations done in this study.

The genetic classification of Tsou and Seediq in the Austronesian family is shown below (Blust 1999; but see Li (l999), Dyen (1990), Starosta (1995) for dissenting views):

668

Malayo-Polynesian

Paiwanic

Puyuma

Eastern Formosan TapangU

Proto-Austronesian Rukaic Tsou Tfuya

Tsouic Luhtu

Bunun Southern Tsou

Western Plains

Northwest Formosan

Atayal

Atayalic

Seediq

The organization of this paper is as follows. First, the basic structural differences between Tsou and Seediq in case marking, word order, and relative clause formation are introduced in Sections 2 through 4. Sections 5, 6, 7, and 8 take up the nature of focus in the two languages as it relates to lexical transitivity, discourse transitivity, grounding and aspect and mood respectively. Section 9, the core of the paper, is an extended examination of the discourse-pragmatics of focus in syntactic coding, referential distance and topic persistence. Section 10 is the conclusion.

3. Case marking

Seediq has just two case markers: the nominative ka and the genitive na, which marks the agent in NAF clauses. There is reason to believe that Seediq is getting rid of its nominative case marker. Although it is true that in narratives ka-marking makes a strong presence, the preferred strategy in Seediq conversation is to leave the “subject” unmarked with ka. (In AF clauses, 98% of the sentences are unmarked, and in NAF clauses, the percentage stand at 87%), and the appearance of ka is strongly associated with marked pragmatic functions. Further research might reveal that ka occurs mostly with a semantically constrained set of predicates and that the low frequency of ka suggests that most of the time, inferring the relationship between the NP and the predicate is not problematic. I therefore interpret this finding as calling into question the usual practice of taking ka as a nominative marker. Rather, ka may best be viewed as a marker of pragmatic functions rather than a nominative marker.

Tsou, on the other hand, has a complex and vibrant system of case marking, with a set of nominative markers indicating “subject” and another set of oblique markers indicating non-subjects and genitive NPs and the language can be given a straightforward analysis as a morphologically ergative language; see Huang (to appear) for details.

669

4. Word order and relative clause

Both Seediq and Tsou are strongly verb-initial, with some pragmatically conditioned variation. In Seediq, word order and focus are interdependent and mutually predictive. Transitive AF clauses are predominantly VOA (more so in narratives than in conversations). They are VAO only if the agent is a clitic pronoun. NAF clauses are predominantly VAO in both narratives and conversations. In NAF, when both A and O are pronouns, the VOA order is also possible, though it was not attested in the present data. There is a strong propensity for negators or auxiliaries to attract pronominal arguments to preverbal position.

In Tsou, the most frequent word order for transitive AF clauses is either Aux VOA or A Aux VO; for NAF clauses, Aux VAO. If there are pronominal arguments, they must be cliticized to aux as enclitics. (This is a rule, not a tendency).

In both Seediq and Tsou, pronominal attraction or cliticization is an important processing strategy, since the pronominal arguments that are attracted to preverbal position or cliticized to the utterance-initial auxiliaries are generally agents, and agents are known to be the central participants in discourse and tend to be maintained as topics in successive clauses. As such, it makes an eminent processing sense for them to gravitate toward sentence-initial position.

An analysis of the patterns of pause and repair behavior in the Tsou corpus data shows that most of the planning difficulty in Tsou centers around two syntactic positions: constituents following the AUX (i.e., the TAM markers) and those following the case markers. There appears to be no significant difference in the level of planning difficulty between the nominative and the oblique case markers. These results are to be expected, since TAM markers and case markers in the language have been highly routinized (grammaticized), freeing the consciousness of the speaker from dwelling on those decisions that are made the most often, to focus on the production of more novel aspects of the message. On the other hand, it is these highly grammaticized forms that present the most challenge to the second language learner.

Word order types in AF and NAF clauses in Seediq are given below. Table 1: Word order types in Seediq (Aux ignored)

2-argument l-argument Pred. Only

VOA: 49 VO: 95 V: 12 AF VAO: 12 VA: 26 VAO: 29 VA: 28 V: 9 NAF VO: 21

670

Table 1 shows that, while in AF over half of the agents are regularly omitted (107 out of l94 agents or 55.l%), in NAF only 34.4% of the agents (30 out of 87) are omitted, suggesting that agents in AF are more topical than those in NAF, a point we shall return to in Section 9 below.

Word order types in AF clauses in Tsou are given below.

Table 2: Word order types in AF clauses in Tsou (Aux ignored)

Two argument clause One argument clause Pred. Only

VOA: 8 AVO: 11 VO: 53 VA: 2 VS: 71 SV: 15 OV: 1 V: 43

Table 2 shows that in transitive AF clauses 69.6% (48/69) of the agents are anaphorically omitted, compared with only 2.9% (2/69) of the objects; this suggests that agents are more likely than patients to be topics. This is in sharp contrast with the situation in NAF clauses where just 12.1% (17/141) of the agents are omitted, compared with 31.9% (45/141) of the patients. This is not surprising since patients in NAF clauses in Tsou are significantly more topical than those in AF clauses. (See Section 9 for further discussion). Word order types in NAF clauses are shown below:

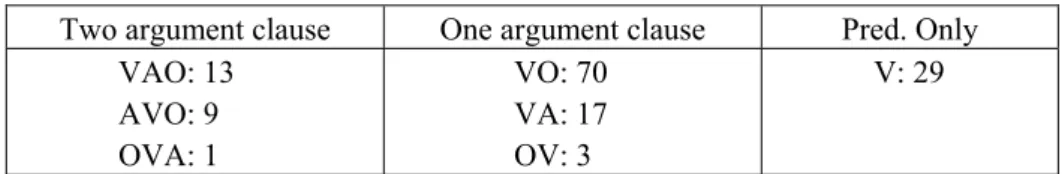

Table 3: Word order types in NAF clauses (Tsou)

Two argument clause One argument clause Pred. Only

VAO: 13 AVO: 9 OVA: 1 VO: 70 VA: 17 OV: 3 V: 29

It is important to observe that word order patterns shown above for both Seediq and Tsou, like those in Philippine-type languages, must be said to show only limited pragmatically conditioned variation, and more so in Seediq than in Tsou. They are strongly verb-initial and the few instances of fronted nominal constructions in Tsou are pragmatically conditioned contrastive focus or referent introductions at episode boundaries. This situation of limited pragmatic variation is in clear contrast with what is found in the Indonesian-type languages where, according to Wouk (1999), patient focus typically allows two main orders, one patient-initial, and the other patient-final, each with known pragmatic effects.

671

Relative clauses in Seediq must follow the head noun they modify. Moreover, only ‘subjects’ can be relativized.1 Thus, if the relative clause is an AF sentence, it is possible

to relativize on the agent, but not the patient. Tsou, on the other hand, behaves very differently. Relative clauses in Tsou may occur to the right or left of their head noun, although there is a decided preference, by a factor of 10 to 1, for right-headed relative clauses. The most common grammatical role of the head noun is as O (object of a transitive clause) in the main clause, and as S (the sole argument of an intransitive clause) in the relative clause.2 Particularly noteworthy is the finding that either a focused NP, marked with a nominative case marker, or an unfocused NP, marked with an oblique case marker, may serve as the head noun of a relative clause, as illustrated below.

(1) ho aUlU eupte’lU to mo cihi ci mo hmUhmUskU ci mamespingi and happen meet OBL AF one Rel AF similar Rel girl

“(he) happened to run into a girl who was similar to him.”

The focus systems in both Seediq and Tsou appear to be fully grammaticized in certain types of dependent clauses. For example, the second verb in a serial verb construction appears in Seediq only in AF as default focus, unless the second verb is one of those verbs that must appear in NAF form (e.g., lmNeluN ‘to think’):

(2) meyah mekan bunga ka qolic. AF:come AF:eat potato SM rat “The rat will come to eat sweet potatoes.”

1 The term ‘subject’ is being put in scare quotes to underscore the now fairly well understood

point that NPs marked with the nominative case marker in Formosan and other Austronesian languages generally are not functionally equivalent to the subjects of languages like English. Unlike subjects, nominative NPs in these languages are not necessarily the most topical elments of their clauses. Indeed, in NAF clauses in Seediq and Tsou, it is usually the agents, marked with a genitive case marker, that are significanly more topical than patients, marked with a nominative case marker.

2 Relative clause constructions in English and Chinese have been shown, based on an analysis in

terms of the grounding of information flow, to exhibit fairly clear-cut preferred structural choices. For non-human referents, for instance, subject heads in these two languages tend strongly to occur with object-relatives, while object heads tend to occur with object-relatives (in Chinese) or to show no clear preferences (in English). For human referents, on the other hand, subject heads tend to occur with subject-relatives and object heads with object-relatives in both languages. A future study of the Seediq and Tsou data along these lines should hopefully yield comparable results.

672

(3) meyah lunlungan daha ‘dyago ta’ mesa. AF:come LF:think they help we AF:say “They were thinking, ‘Let us help (them).’”

Similarly, aspectual and modal verbs in Tsou take no complementizers and must be followed by verbs in AF form.

(4) a. te-to cu ahoi bonU ta naveu.

Fut-1P perf start eat Obl rice “We will start to eat rice.”

b. mi’o mici oengUtu.

AF-1st want sleep

“I’m going to sleep.”

c. mit-ta smeecU’no bonU to eoskU ‘e Voyu. AF-3rd dare eat Obl fish Nom

“Voyu dares to eat fish.”

The use of focus in Seediq is sometimes semantically conditioned in independent clauses in non-preterite aspects. In the future tense/aspect category, the difference between AF and NAF in (5) can be characterized as the difference between a statement of possibility (AF) and an avowed intention (NAF):

(5) a. maha ku hori. AF:go 1SN Puli “I am going to Puli.”

b. haun mu bale ka hori.

PF:go 1SG truly SM Puli “I intend to go to Puli.”

In clauses with a stative verb, the difference between AF and NAF is generally perceived by native speakers to be non-existent:

(6) a. ini ku kela heya NEG 1SN AF:know 3SA “I do not know him/her.”

b. ini mu klai ka heya NEG 1SG PF:know SM 3SN “I do not know him/her.”

673

The functional difference between AF and NAF in the preterite category is the focus of the following sections. Suffice it to say at this point that agents in AF and PF clauses have differing degrees of topicality and continuity and that agents in AF clauses consistently evoke high continuity values, whereas patients consistently evoke low continuity values. Moreover, in the PF clauses, agents are not downplayed. These and other results will be further elaborated below.

5. Focus and lexical transitivity

Since it is not always obvious whether we are dealing with a transitive or intransitive verb when working with Austronesian languages, an explicit definition of ‘lexically transitive’ based on the behavior of verbs in various morphosyntactic environments is therefore necessary. For purposes of this study, a lexically transitive verb in Seediq is one that can occur with the patient focus form -un or the locative focus form -an. For example, the verb stem ha- ‘go, head toward’ is lexically transitive in (7b) since it allows -un with no additional transitivizing morphology:

(7) a. maha ku hori.

AF-go 1SN Puli “I will go to Puli.” b. haun mu ka hori.

PF-go 1SG SM Puli “I will go to Puli.”

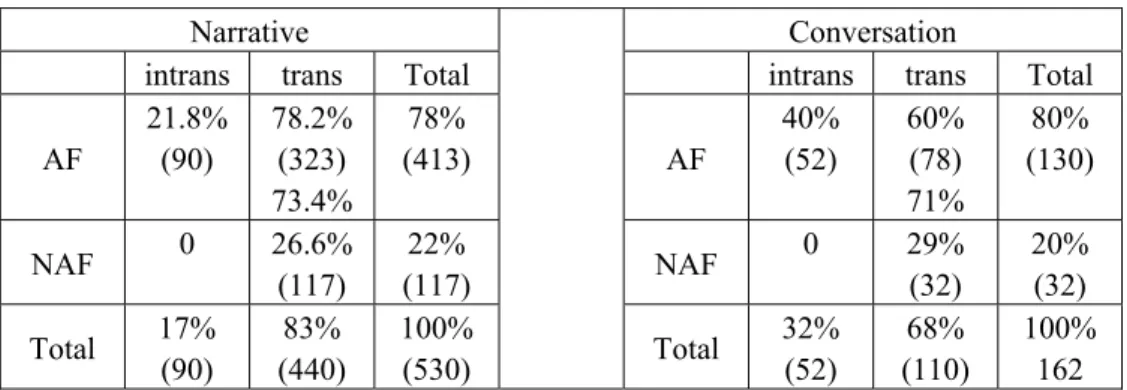

Clause types are distributed differently in the two languages. In Seediq, in either the narrative or the conversational data, AF forms occur predominantly in transitive sentences and transitive verbs occur in AF and NAF forms in unequal proportions. Both of these results are not in accord with our understanding of Austronesian languages, specifically with the findings reported in Shibatani (l988) and Payne (l994) for Cebuano, a Philippine language. It is now stale news that in Austronesian languages, reflexes of PAN *mu-/-um- typically mark a verb as intransitive. Significantly, unlike Cebuano and other WAN languages, there is in Seediq simply no association between lexical intransitivity and AF form. Furthermore, the noted similarity in distribution between AF and NAF clauses in the two types of corpus data (narrative and conversation) suggests that AF and NAF clauses have fairly stable discourse functions, whatever they are, and are possibly quite independent of discourse type. This means that if AF clauses are more accessible in conversations, they are also more accessible in narratives. These data are presented in Table 4.

674

Table 4: Distribution of focus forms in Seediq

Narrative Conversation

intrans trans Total intrans trans Total

AF 21.8% (90) 78.2% (323) 73.4% 78% (413) AF 40% (52) 60% (78) 71% 80% (130) NAF 0 26.6% (117) 22% (117) NAF 0 29% (32) 20% (32) Total 17% (90) 83% (440) 100% (530) Total 32% (52) 68% (110) 100% 162 Tsou is an altogether different story. As in other WAN languages, there is a strong association between lexical intransitivity and AF clauses, especially in conversation, and between lexical transitivity and NAF clauses. As in Tagalog, NAF clauses in conversation account for nearly 75% of the transitive clauses. These data are presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Distribution of focus forms in Tsou

Narratives Conversation

intrans trans Total intrans trans Total

AF 65% (129) 35% (69) 33% 58.4% 198 AF 81% (90) 19% (21) 26% 65% (111) NAF 0 65% (141) 67% 41.6% (141) NAF 0 60 74% 35% (60) Total 129 210 339 Total 90 81 171

6. Focus and discourse transitivity

Focus systems in Austronesian languages have been discussed within two discourse frameworks, that of discourse transitivity (Hopper and Thompson 1980) and discourse ergativity (Hopper 1982, 1986) and that of topicality (Givón 1983).3 In this section I consider whether or not the use of focus in my data is consistent with an analysis of

675

Seediq or Tsou as discourse ergative in the sense of Hopper (l982, l986). A language is considered discourse ergative if its PF clauses are the more frequent focus form, correlate with high levels of discourse transitivity and are found mainly in the foreground portions of the texts, while AF clauses correlate with lower discourse transitivity and are found in the background portions of the texts. Since individuation of patients is a key component in Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) discourse transitivity hypothesis, patients in the Seediq database are classified according to three levels of individuation as +referential and +definite, +referential but -definite and -referential. Results of the analyses are given in Table 6.

Table 6: Focus and referential status of lexical patients (Seediq) Narrative&

Conversation AF NAF Total

+Referential +Definite 189 (66.8%) 60 (68.9%) 249 +Referential -Definite 70 (24.7%) 25 (28.7%) 95 -Referential 24 (8.5%) 2 (2.3%) 26 Total 283 (100%) 87 (100%) 370 (χ2=4.081, p>.05)

Table 6 shows that although in Seediq some AF clauses take non-referential patients, lexical patients in NAF are not significantly more referential and/or definite than those in AF clauses. Unlike Tagalog (Wouk l986), then, neither AF nor NAF can be said to correlate with high discourse transitivity. These results both contradict Holmer’s (l999:425) assertion that a Seediq PF clause displays a high discourse transitivity and presents an interesting, yet puzzling exception to Hopper’s hypothesis.

7. Focus and grounding

The choice of focus forms may be determined by grounding. Classical Malay is just such a language. Cumming (l995:254) suggests that in classical Malay transitive event-line clauses are all marked with patient focus forms and that agent focus clauses occur only in a background clause. We have shown above that NAF clauses in Seediq are not associated with higher discourse transitivity. One would then predict, given Hopper’s (1982, 1986) hypothesis, that these clauses would not be associated with foregrounded portions of the texts. The prediction is borne out, as Table 7 shows.

676

Table 7: Focus and grounding (Seediq)

Narrative AF NAF Total

Foregrounded 271 (70%) 97 (68%) 368 (70%)

Backgrounded 115 (30%) 45 (32%) 160 (30%)

Total 386 (100%) 142 (100%) 528 (100%)

(χ2=0.177, p>.05)

Chi-square tests show that unlike Classical Malay, grounding is hardly a significant factor in the choice of Seediq focus. Since Hopper’s definition of discourse ergativity depends, among other things, on a correlation of NAF with foregrounding, Seediq NAF clauses cannot be considered ergative constructions and the language cannot be considered ergative at the discourse level in the sense of Hopper.

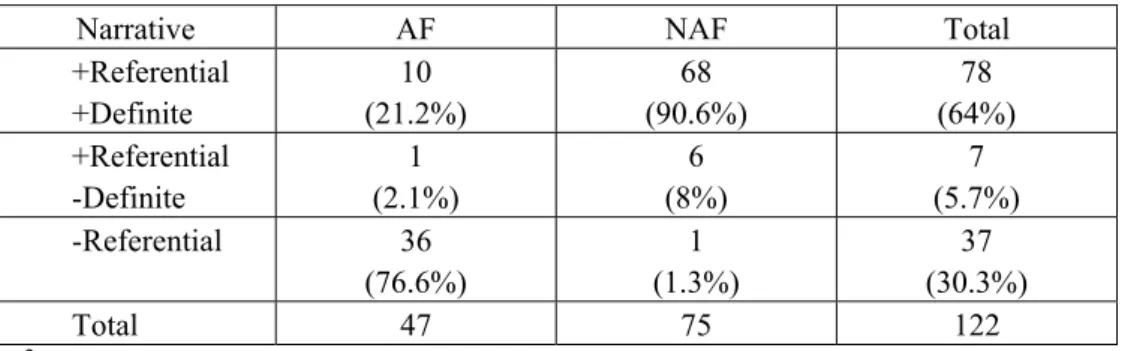

Once again Tsou behaves very differently from Seediq in terms of either individuation of patients or grounding. Unlike Seediq, there is a strong association in Tsou between NAF clauses and identifiability of patients. This means that the grammatical function of the focus system in Tsou is in part to distinguish low transitive AF from high transitive NAF clauses. The system is then used in discourse to signal the greater salience of the NAF patient relative to the AF patient (see further below). These results are given in Tables 8 and 9.

Table 8: Focus and referential status of lexical patients (Tsou)

Narrative AF NAF Total +Referential +Definite 10 (21.2%) 68 (90.6%) 78 (64%) +Referential -Definite 1 (2.1%) 6 (8%) 7 (5.7%) -Referential 36 (76.6%) 1 (1.3%) 37 (30.3%) Total 47 75 122 (χ2=65.72, p<.001)

677

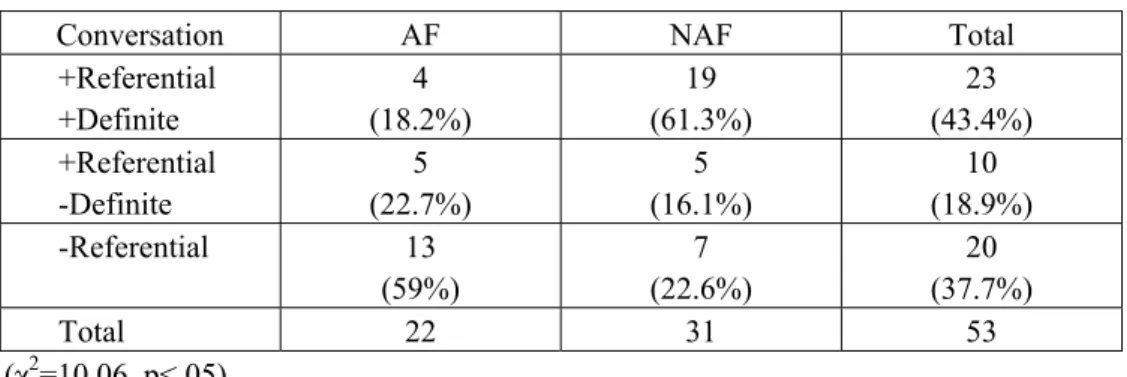

Table 9: Focus and referential status of lexical patients (Tsou)

Conversation AF NAF Total

+Referential +Definite 4 (18.2%) 19 (61.3%) 23 (43.4%) +Referential -Definite 5 (22.7%) 5 (16.1%) 10 (18.9%) -Referential 13 (59%) 7 (22.6%) 20 (37.7%) Total 22 31 53 (χ2=10.06, p<.05)

High transitivity NAF clauses would be predictably associated with the foreground of a narrative. The prediction is not confirmed, however, as seen in Table 9. Paradoxically, a higher proportion of NAF clauses occur in the background, contradicting Hopper’s (1982, 1986) one criterion for discourse ergativity. This is a puzzling result and raises the troubling question of the status of grounding as a criterion for discourse ergativity.

Table 10: Focus and grounding (Tsou)

Narrative only AF NAF Total

Foregrounded 112 (42.7%) 66 (36.3%) 178 (40%)

Backgrounded 150 (57.3%) 116 (63.7%) 266 (60%)

Total 262 182 444

(χ2=1.89, p>.05)

8. Focus, aspect and mood

Hopper and Thompson’s (l980) discourse transitivity hypothesis would predict that low transitivity correlates with imperfective aspect and high transitivity with perfective. Since all aspect and mood distinctions in Tsou have been taken over by the auxiliary system, and since aspect is not an obligatory grammatical category, but merely one component of the complex realis/irrealis auxiliary system that covers a wide range of assertive/non-assertive modal meanings, it is not possible to examine directly the correlation between focus and aspect. There are, however, two perfective particles cu and

c’u in the language and they appear fairly frequently in the texts. As Table 11 shows these

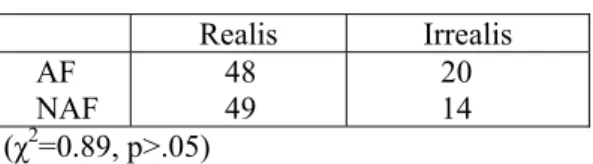

two perfective markers do not correlate with focus form, since cu and c’u are approximately evenly distributed between AF and NAF clauses.

678

Table 11: Focus and perfective markers (Tsou)

Realis Irrealis AF NAF 48 49 20 14 (χ2=0.89, p>.05)

Table 11 says that there are 48 AF clauses occurring with realis auxiliary forms in which the perfective particle cu or c’u appears and there are 20 AF clauses occurring with irrealis auxiliary forms where cu or c’u appears and so on. Chi-square tests show that there is no significant correlation between perfective particle and focus form. Similarly, the Tsou data also show no significant correlation between focus form and modality (realis/irrealis distinction). As shown in Table 12, NAF clauses account for nearly half (46.8%) of the realis, but also nearly half (41.9%) of the irrealis clauses. Again, these results are unsettling since NAF clauses in Tsou have been shown to correlate with higher transitivity values (Tables 5, 8 and 9). Given these results, one would then predict them to show a stronger tendency to occur with realis auxiliaries. Preliminary results of an on-going study of the behavior of various clause types in Tsou show that, while in the

ho-conditional there is a strong association between the use of realis/irreallis aux in the

protasis, but that in the apodosis there is no such association whatsoever in the hoci- or

honci- marked conditional construction. Apparently a much more complex interpenetration

is going on between the various transitivity parameters and reality status than we currently understand and further research is clearly warranted.

Table 12: Focus and modality (Tsou)

Realis Irrealis AF NAF 116 (53.2%) 102 (46.8%) 68 (58.1%) 49 (41.9%)

9. Focus and topicality

Focus systems in Austronesian languages have also been discussed within the framework of topicality. Cooreman et al. (l984) show that in morphologically ergative languages, clauses with ergative case marking are used when the agent is more topical (defined in terms of three measures of referential distance, persistence and syntactic coding) and the patient is of moderate topicality. They therefore propose that the discourse function of ergativity is to express that particular topicality relationship. Cooreman et al. further suggest that in a language where there is no morphological evidence for ergativity, if the passive is more frequent in texts than the active, and is used

679

when the agent is topical and the patient only moderately topical, the language can be considered ergative at a discourse level and the passive can be considered ergative. If this proposal is correct, we should expect that in any language which is discourse ergative, there will be a high correlation between passive clauses and a combination of high topical agent and moderately topical patient, and between non-passive clauses and non-topical patients (Wouk 1996:364). Although the status of Seediq as a morphologically ergative language is moot, Tsou is clearly ergative (cf. Starosta 1988, 1997), and so it would be appropriate to investigate whether they are ergative at the discourse level in this sense (cf. Cumming and Wouk l987).

Various clause types of a discourse ergative language have been characterized, in terms of the pragmatic notion of relative topicality of the agent and patient arguments of the clause, as follows (Cooreman et al. 1984, Givón 1994):

1) Clause type relative topicality of agent and patient

Antipassive agent >> patient patient non-topical and freq. omitted Ergative(active) agent > patient patient topical, but agent more so Passive agent << patient agent non-topical and frequently omitted (Inverse agent < patient ) agent topical, but patient more so

The double arrow-head indicates a greater degree of outranking than the single arrow-head. The essential assertions are: (1) in antipassive clauses the patient is non-topical and the agent highly topical; (2) in ergative clauses, the agent is topical and the patient moderately topical; (3) in passives, the agent is downplayed. Givón (l994) suggests that these four clause types typically occur at different frequencies: antipassives are in the 10-15% range; ergatives are generally much more frequent, at 60-70%; passives are at 5-10% and inverses at 15-20%.

In the present study, however, only two clause types have been distinguished, namely AF and NAF clauses. Word order without being accompanied by morphological differences is not used as a criterion for distinguishing clause types. Moreover, as shown above, both Seediq and Tsou are strongly verb-initial and show only very limited word order variation. In these respects, Seediq and Tsou differ in a significant way from either Chamorro or Tagalog whose data form the basis of Cooreman et al.’s (l984) study.

In this and the following sections topicality is assessed through three discourse measures: syntactic coding, referential distance, and topic persistence. Syntactic coding is relevant to an understanding of the discourse deployment of focus. Since more topical arguments are generally coded with high continuity devices (zero anaphora, clitics, pronouns) rather than medium (lexical nouns or noun phrases) or low continuity devices (modified nouns), if agents and patients in AF or NAF clauses differ in topicality, we would expect a strong association between focus form and syntactic coding.

680

9.1 Focus and syntactic coding

Results of the analysis show that as far as this metric goes, both Seediq and Tsou show the expected strong association between focus form and syntactic coding. In Seediq narratives, agents in AF or NAF are significantly more continuous than patients and the overall difference between AF and NAF is also significant. These results are given in Table 13.

Table 13: Focus and syntactic coding in Seediq (narratives)

Focus AF NAF

Agent Patient Agent Patient

High 105 (71%) 32 (21.6%) 69 (95.8%) 30 (41.6%) Med (15.5%) 23 (50%) 74 (2.8%) 2 (23.6%) 17 Low (13.5%) 20 (28.4%) 42 (1.4%) 1 (34.7%) 25 Total 148 148 72 72 (In AF, χ2=73.4, p<.001; in NAF, χ2=49.2, p<.001.

AF* NAF: χ2=18.06 for A, p<.001; χ2=15.01 for P, p<.001)

Conversational data in Seediq yield basically the same results. As shown in Table 14, agents are significantly more continuous than patients in AF or NAF, although there is no significant difference in topicality between agents in AF and those in NAF or between patients in AF and NAF clauses, as shown in Table 14.

Table 14: Focus and syntactic coding in Seediq (conversation)

Focus AF NAF

Agent Patient Agent Patient

High (88.5%) 46 (53.8%) 28 (95.6%) 22 (60.8%) 14

Med (11.5%) 6 (36.5%) 19 (4.4%) 1 (34.8%) 8

Low 0 5 (9.6%) 0 1 (4.4%)

Total 52 52 23 23 (AF: χ2=16.14, p<.05; NAF: χ2=8.22, p<.05.

AF* NAF: χ2=1.05 for A, p>.05; χ2=0.86 for P, p>.05)

681

data are still significantly more continuous than patients, there is considerable narrowing of the difference in continuity between the two types of nominal arguments. There is also no significant overall difference in topicality between agents in AF clauses and those in NAF clauses or between patients in AF and those in NAF clauses. These results are entirely to be expected. Conversation between family members or friends is known to have a lower information pressure, in the sense of Du Bois (1987), since participants tend to refer to each other with first and second personal pronouns and their objects of talk are often mutual friends rather than new entities that must be coded with low or medium continuity devices. An inspection of Tables 13 and 14 shows that about 20% of the agents and patients in the narrative data were coded with low continuity devices as opposed to just 4% for the conversational data, a consequence of the nature of conversation.4 For basically the same reason, Table 14 also shows that there is no significant overall difference in topicality between agents in AF clauses and those in NAF clauses or between patients in AF and those in NAF clauses.

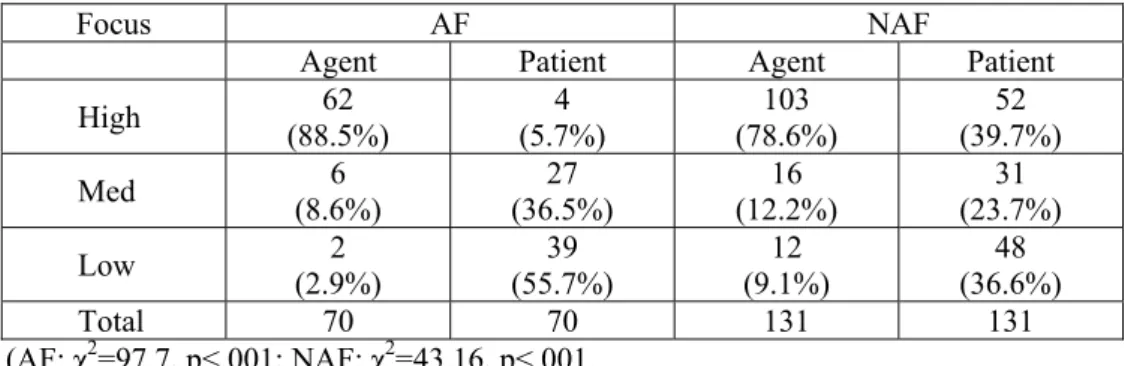

The same methodology was applied to Tsou narrative data and the results of the analysis are given in Table 15:

Table 15: Focus and syntactic coding in Tsou (narratives)

Focus AF NAF

Agent Patient Agent Patient

High (88.5%) 62 (5.7%) 4 (78.6%) 103 (39.7%) 52

Med (8.6%) 6 (36.5%) 27 (12.2%) 16 (23.7%) 31

Low (2.9%) 2 (55.7%) 39 (9.1%) 12 (36.6%) 48

Total 70 70 131 131 (AF: χ2=97.7, p<.001; NAF: χ2=43.16, p<.001.

AF* NAF: χ2=4.06 for A, p>.05; χ2=27.76 for P, p<.001)

Table 15 shows that as expected, agents in AF or NAF are significantly more continuous than patients, especially in AF clauses. While there is no significant difference in topicality between agents in AF and those in NAF clauses, patients in NAF are significantly more topical than those in AF.

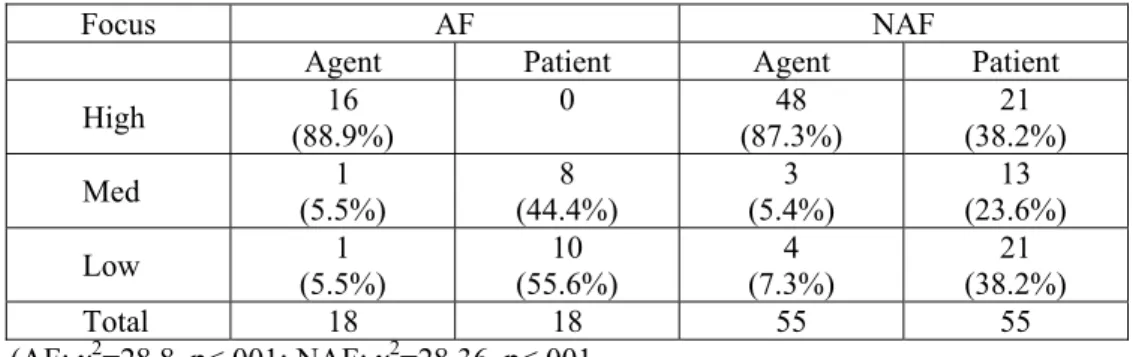

The corresponding results for Tsou conversational data are given in Table 16. Again, agents in AF and NAF are significantly more topical than patients, with patients in NAF

4 This is done by summing all of the numerical values of the agents and patients coded with low

682

showing the expected high degree of topicality. Again as in the narrative data, while there is no significant difference in topicality between agents in AF and those in NAF, patients in NAF are significantly more topical than those in AF.

Table 16: Focus and syntactic coding in Tsou (conversation)

Focus AF NAF

Agent Patient Agent Patient

High (88.9%) 16 0 48 (87.3%) (38.2%) 21

Med (5.5%) 1 (44.4%) 8 (5.4%) 3 (23.6%) 13

Low (5.5%) 1 (55.6%) 10 (7.3%) 4 (38.2%) 21

Total 18 18 55 55 (AF: χ2=28.8, p<.001; NAF: χ2=28.36, p<.001.

AF* NAF: χ2=0.04 for A, p>.05; χ2=9.9 for P, p<.05)

9.2 Focus and referential distance in Seediq

Referential distance (RD) is calculated by counting back to the nearest prior mention of a referent, including zero anaphora. A referent is highly topical if its previous mention is in the previous clause, moderately topical if its previous mention is two or more clauses back, low in topicality if more than three clauses back (Givón 1994). More continuous, important or topical participants exhibit smaller RD values, with the highest topic continuity value being one. In the following tabulation, no distinction was made between new mentions and reintroductions (cf. Wouk 1999). Results of the analysis for RD in the Seediq narrative and conversational data are given in Tables 17 and 18.

Table 17: Focus and referential distance (narratives)

Focus AF NAF Total

A/S O A/S O N % N % N % N % N % High (RD<2) 259 69 61 39 92 70 53 52 465 61 Med (RD=2~10) 93 25 66 42 33 25 32 31 224 29 Low (RD>10) 21 6 29 19 6 5 17 17 73 10 Total 373 100 156 100 131 100 102 100 762 100 (AF: χ2=47.32, p<.001; NAF: χ2=12.35, p<.01.

683

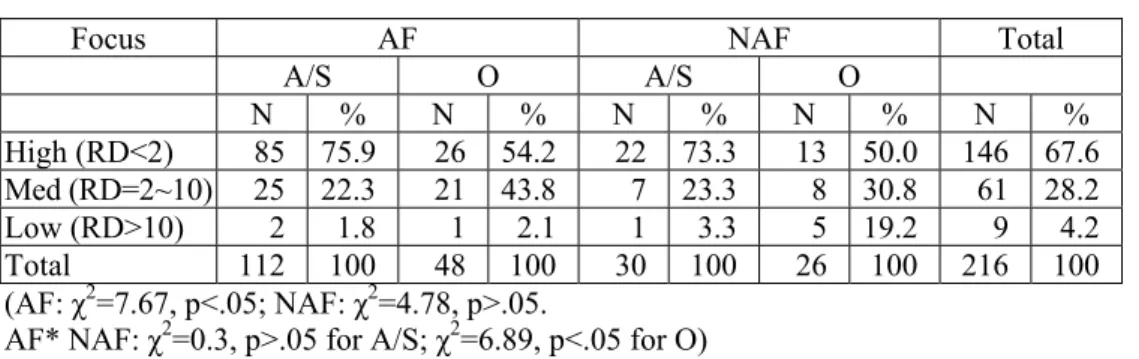

Table 18: Focus and referential distance (conversations)

Focus AF NAF Total

A/S O A/S O N % N % N % N % N % High (RD<2) 85 75.9 26 54.2 22 73.3 13 50.0 146 67.6 Med (RD=2~10) 25 22.3 21 43.8 7 23.3 8 30.8 61 28.2 Low (RD>10) 2 1.8 1 2.1 1 3.3 5 19.2 9 4.2 Total 112 100 48 100 30 100 26 100 216 100 (AF: χ2=7.67, p<.05; NAF: χ2=4.78, p>.05.

AF* NAF: χ2=0.3, p>.05 for A/S; χ2=6.89, p<.05 for O)

The results shown in Tables 16 and 17 for RD are at best ambiguous, since although there was a high correlation between NAF clauses and a combination of high topical agent and moderately topical patient for the narrative data, there was an absence of such a correlation in conversation, where the difference between agent and patient in RD is statistically insignificant, χ2 value being only 4.78. Paradoxically, patients in AF appear to be either indistinguishable in topicality from patients in NAF (in narrative) or even more topical than patients in NAF clauses (in conversation). But this is perhaps to be expected, since it was shown in Table 6 that lexical patients in NAF in Seediq are not significantly more referential and/or definite than those in AF clauses. Again it is the narrative data rather than the conversational data that is more consistent with the prediction of Cooreman et al. (l984), which was based on narrative data.

Combining the results in Tables 17 and 18, we see that the overall difference in RD between AF and NAF is not statistically significant, as shown in Table 19.

Table 19: Focus and referential distance (Seediq)

Agent Focus Non-Agent Focus Total

Narrative &

Conversation A/S O A/S O

N % N % N % N % N % High (RD<2) 344 70.9 87 42.6 114 70.8 66 51.6 611 62.5 Med (RD=2~10) 118 24.3 87 42.6 40 24.8 40 31.3 285 29.1 Low (RD>10) 23 4.7 30 14.7 7 4.3 22 17.2 82 8.4 Total 485 100 204 100 161 100 128 100 978 100 (AF: χ2=53.08, p<.0l; NAF: χ2=17.01, p<.01.

AF* NAF: χ2=.054, p>.05 for A/S; χ2=4.34, p>.05 for O)

9.3 Focus and topic persistence in Seediq

684

ten clauses following the present occurrence. More continuous or topical participants exhibit larger persistence values, with the lowest value being 0. The results for persistence in the Seediq data are given in Tables 20 and 21.

Table 20: Focus and persistence (narratives)

Focus AF NAF Total

A/S O A/S O N % N % N % N % N % High (RD>=3) 71 46 29 19 23 32 14 22 137 31 Med (RD=2) 30 19 29 19 9 13 15 23 83 19 Low (RD<=1) 55 35 97 62 39 55 36 55 227 50 Total 156 100 155 100 71 100 65 100 447 100 (AF: χ2=29.26, p<.001; NAF: χ2=3.55, p>.05.

AF* NAF: χ2=7.81, p<.05 for A/S; χ2=1.02, p>.05 for O)

Table 21: Focus and persistence (conversation)

Focus AF NAF Total

A/S O A/S O N % N % N % N % N % High (RD>=3) 19 40.4 6 10.3 3 12.0 2 7.4 30 19.1 Med (RD=2) 9 19.2 11 19.0 7 28.0 6 22.2 33 21.0 Low (RD<=1) 19 40.4 41 70.7 15 60.0 19 70.4 94 59.9 Total 47 100 58 100 25 100 27 100 157 100 (AF: χ2=14.03, p<.001; NAF: χ2=0.67, p>.05.

AF* NAF: χ2=6.21, p<.05 for A/S; χ2=0.27, p>.05 for O)

In both sets of Seediq data, agents in NAF clauses are not significantly different from patients in persistence, consistent with the results for referential distance given above. The overall difference between AF patients and NAF patients is also not significant. Again these results contradict Cooreman et al.’s (l984) prediction.

Summarizing the findings on Seediq presented in the preceding sections, it is true that topic continuity values of agents and patients in NAF clauses are not always precisely in the same direction: while in three of the six counts presented (two each for each of the three metrics), agents are significantly more continuous than patients, in the other three counts, patients are just as continuous as agents. We therefore conclude that the choice of NAF in Seediq is not determined by topicality measures. Moreover, agents in AF are in general more continuous than those in NAF, while patients in NAF are not more continuous than those in AF clauses.The topicality values for agent and patient in AF and NAF clauses can thus be ranked as follows:

685

2) A(AF) > A(NAF) > P(NAF) = P(AF)

These results suggest the following division of clause type:

3) AF: agent >> patient agent much more topical and often omitted; patient non-topical and rarely omitted NAF: agent > patient agent frequently more topical and frequently omitted; patient occasionally as topical as agent and rarely omitted

Seediq is thus an unusual language in having two broadly similar clause types in which agent and patient perform basically similar pragmatic functions. The NAF clause in Seediq cannot be straightforwardly identified with the ergative (active) clause type of a discourse ergative language presented in (l) since, as shown in Table 4, there is no association between NAF clauses and lexical transitivity and, furthermore, NAF clauses are far outnumbered by AF clauses, by a factor of 1 to 4. Furthermore, the AF clauses in Seediq cannot be identified with the antipassive either, since patients in these clauses are rarely omitted.

9.4 Focus and referential distance in Tsou

The same methodology was applied to the Tsou data and the results of the analyses for RD are given below in Table 22.

Table 22: Focus and referential distance in Tsou (narratives)

Focus AF NAF Total

A/S O A O N % N % N % N % N % High (RD<2) 52 78.8 2 11.8 49 89.1 23 52.2 126 69.2 Med (RD=2~10) 13 19.7 8 47.0 6 10.9 13 29.5 40 21.9 Low (RD>10) 1 1.5 7 41.1 0 0.0 8 18.2 16 8.9 Total 66 100 17 100 55 100 44 100 182 100 (AF: χ2=35.4, p<.001; NAF: χ2=18.98, p<.001.

AF* NAF: χ2=2.69, p>.05 for A/S; χ2=8.64, p<.05 for O)

The results for RD in the Tsou data in Table 22 show that in both AF and NAF clauses, agents are significantly more continuous than patients and that NAF patients are significantly more continuous than AF patients. These results are consistent with the prediction of Cooreman et al. (l984).

686

9.5 Focus and topic persistence in Tsou

The results for topic persistence in the Tsou data are given in Table 23. Table 23: Focus and persistence (narratives)

Focus AF NAF Total

A/S O A/S O N % N % N % N % N % High (RD>=3) 30 45.4 2 11.7 33 60.1 14 31.8 79 43.4 Med (RD=2) 13 19.7 4 23.5 13 23.6 14 31.8 47 25.8 Low (RD<=1) 23 34.8 11 64.7 9 16.3 16 36.3 56 30.7 Total 66 100 17 100 55 100 44 100 182 100 (AF: χ2=7.19, p<.05; NAF: χ2=8.83, p<.05.

AF* NAF: χ2=4.34; p>.05 for A/S; χ2=4.51, p>.05 for O)

Table 23 shows that the results for persistence are consistent with Cooreman et al.’s prediction: AF agents are significantly more topical than patients; NAF agents are highly topical and patients are moderately topical. The overall differences between AF patients and NAF patients are not significant, however.

At this point, it is convenient to provide a summary of the pragmatic functions of agents and patients in AF and NAF clauses in Tsou as presented in the preceding sections. Unlike in Seediq, the choice of NAF in Tsou is conditioned by topicality measures in that agents in NAF are consistently significantly more continuous than patients, as determined through the three topicality metrics. There is in addition no significant difference in continuity between agents in AF and those in NAF. The topicality values for agent and patient in these clauses can be ranked as follows.

4) A(AF) = A(NAF) >> P(NAF) > P(AF) These results suggest the following clause types:

5) AF: agent >> patient agent highly topical and often omitted; patient non- topical and rarely omitted

NAF: agent >> patient agent highly topical and rarely omitted; patient moderately topical and frequently omitted

What distinguishes Seediq from Tsou, then, is the behavior of their NAF clauses in discourse pragmatics. Recall that, as shown in Sections 5 through 7, there is a strong association between lexical transitivity and NAF clauses and between lexical

687

intransitivity and AF clauses in Tsou. Unlike in Seediq, there is also a strong association in Tsou between NAF clauses and identifiability of patients. Finally, as in Tagalog, NAF clauses in Tsou account for nearly 75% of the transitive clauses in the language, while they make up less than 30% of the transitive clauses in Seediq.

10. Conclusion

We have shown, based on a careful analysis of both narrative and conversational data, that the pragmatics of focus systems in Seediq and Tsou show considerable difference from each other, with the conversational data in Seediq in particular showing even greater divergence from the ‘expected’ behavior. It is clear that in many ways it is Tsou that has remained more ‘conservative’ and behaves much more like what is known about the Philippine languages (Wouk 1996, Starosta et al. 1982). No pragmatic difference appears to underlie the choice between AF and NAF clauses in Seediq, there being more no’s than yes’s in Table 24 under Seediq. Neither discourse transitivity nor grounding can be shown to be a significant factor in the deployment of focus forms. Furthermore, the choice of NAF correlates with neither referential distance nor topic persistence. These results show that the intuitions regarding the relative pragmatic statuses of the core arguments in the clause, which form the very foundation of the ‘focus’ terminology, have been mistaken, at least as far as Seediq is concerned.

Table 24 summarizes the results we have presented thus far in the preceding sections, incorporating from other WAN languages in order to understand the pragmatics of focus in these two languages from a wider comparative perspective. Single question marks indicate non-availability of the relevant statistics; a double question mark in Seediq indicates ambiguity in interpretation, since the RD metric for narrative and conversational data has been shown to yield conflicting results.

688

Table 24: Pragmatics of focus in Seediq, Tsou and some WAN languages Features Seediq Tsou Indones (Wouk 1999)Philippine&W. (Wouk 1999) Sasak Transitivity

(AF Low/NAF High) (1) Foreground (2) Individuation of Patient (3) Aspect/modality no no no no yes no yes yes yes no yes no Topicality

(4) NAF more frequent (5) Syntactic coding (AF: A>>P) (NAF: A>P) (6) Referential distance (AF: A>>P) (NAF: A>P) (7) Topic persistence (AF: A>>P) (NAF: A>P) no yes yes yes ?? yes no yes yes yes yes yes yes ? yes yes no ? no no no

Based on the preceding discussions and those reported in the literature, the pragmatics of focus characteristics of various WAN languages may be seen to form a continuum, with PAN at the top of Table 25 below representing a discourse-transitivity dominated language and English at the bottom representing a thematicity-dominated language, and all the WAN languages falling somewhere in-between the two points. Research into the discourse deployment of voice in Rukai, the only known active-passive language in Formosa, or in the Sulawesi languages, known to have lost their PF morphology (conjugated PF), has yet to be undertaken. Discourse grammarians interested in Austronesian languages are waiting with baited breath for news about these languages. Still, it is of considerable theoretical interest to note that Standard Jakarta Indonesian (SJI) is located roughly at the midpoint between the two ends of the continuum, since functionally its focus system is intermediate between Tagalog and English (Wouk l996) in that: (a) it has an agentless passive construction with high textural frequency; and (b) although its PF clauses continue to show correlation with high discourse transitivity, there is a strong correlation between focus choice and the relative salience of the argument NPs. AF clauses in SJI are used when agents are more thematic than patients and PF clauses used when patients are more thematic than agents.

689

Table 25: Pragmatics of focus in WAN languages5 *PAN

* Toba Batak, Tagalog (Wouk 1986), early modern Malay (Hopper 1986), Karao (Brainard 1994): transitivity, esp. individuation of patient the most important focus determinant

*Classical Malay (Cumming 1995:254): grounding is primary determinant for focus *Tsou: shows innovations in focus morphology; functionally PF far more common, highly topical and is determined by discourse transitivity and topicality metrics. *Cebuano (Payne1994): Topicality metrics condition choice of AF/NAF; some PF clauses have topicality pattern typically associated with passive (P>>A). *Seediq: formal focus morphology still kept, but functionally the use of PF not determined by transitivity or topicality

*Standard Jakarta Indonesian (Wouk 1996): (1) much of focus morphology is lost;

(2) functionally, focus system is intermediate between Tagalog and English in that (a) PF clauses are fairly frequent;

(b) It has agentless passives with high textual frequency

(c) PF clauses continue to show strong but incomplete correlation with high discourse transitivity (in punctuality, mode, and individuation of patient, but not in other parameters);

(d) But there is strong correlation between focus choice and the relative salience of the argument NPs (more salient patients correlate with PF; more salient agents correlate with AF)

*Sasak (Wouk 1999) (1) loss of PF morphology (conjugated PF)

(2) in oral clauses (PF) the patient generally much more topical than the agent

(3) focus system weakly determined by certain dimensions of transitivity, not topicality.

*Modern Malay (Cumming 1995): focus functions akin to English style voice system *Rukai: complete loss of focus morphology; active-passive system (Li 1997)

*English: transitivity not a factor in determining clause structures.

5 The placement of the various Austronesian languages on the continuum relative to one another is

motivated strictly in terms of their discourse pragmatics. Placing Toba Batak, Tagalog and Classical Malay rather than Tsou closer to PAN, for example, in no ways implies their genetic relationships, nor their chronological development in relation to PAN.

690

These and other findings suggest the following scenario of diachronic development from a transitivity-dominated language like Tagalog to a more thematicity-dominated language like Modern Malay or English. First, NAF clauses would have to show a weakening correlation with discourse transitivity or topicality, initially in just some of the parameters, but subsequently in more and more of the parameters, to the point where functionally the use of NAF is not determined by transitivity, as seen in Seediq and SJI. Secondly, as the correlation between NAF and transitivity weakens, an increasingly strong association between the choice of NAF and thematicity of the patient would develop, resulting in the formation of a construction in which the patient is generally more topical than the agent, as seen in Sasak. Finally, with the function of NAF now largely replaced by the (agented or agentless) passive, the NAF morphology would be finally lost and the transition to a thematicity-dominated language would then ensue, again as seen in Sasak.6 And of course the path of development would be reversed for a thematicity-dominated language to change into a transitivity-dominated language.

To conclude, then, Seediq and Tsou, two primary-branch, Austronesian languages spoken in the central highlands of Taiwan, represent interesting case studies whose focus systems differ considerably from one another, on the one hand, and from other Western Austronesian languages, on the other, when the pragmatic functions of their focus forms are studied within the framework of quantitative discourse analysis, using naturally occurring interactional data. Indeed, an inspection of Table 25 should convince us that each of the languages given there exhibits unique discourse properties with respect to its focus system and that these properties at best form a family resemblance relationship among themselves. One can talk intelligibly about the nature of a ‘focus language’ only by making considerable simplifying assumptions. Since the linkage between language use and grammar is to be found in interaction, this process needs to be better understood and taken into account as it applies to the study of the discourse pragmatics of Formosan and other Austronesian languages. Hopefully, as discourse functions of the focus systems in other primary branch Formosan languages are investigated in comparable depth, we will be in a much better position to speculate on the nature of the focus system in the ancestor language and the diachronic break-up of the system into its present-day daughter languages.

691

References

Baldi, Philip (ed.). 1990. Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Brainard, Sherri. 1994. Voice and ergativity in Karao. Voice and Inversion, ed. by Talmy Givón, 365-402. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Blust, Robert. 1999. Subgrouping, circularity and extinction: Some issues in Austronesian comparative linguistics. Selected Papers from the Eighth

International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, ed. by E. Zeitoun and Paul

Li, 31-94. Taipei: Institute of Linguistics (Preparatory Office), Academia Sinica. Cooreman, Ann. 1982. Topicality, ergativity and transitivity in narrative discourse:

Evidence from Chamorro. Studies in Language 6:343-374.

Cooreman, Ann. 1987. Transitivity and Discourse Continuity in Chamorro Narratives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Cooreman, Ann, Barbara Fox, and Talmy Givón. 1984. The discourse definition of ergativity. Studies in Language 8:1-34.

Cumming, Susanna. 1988. Syntactic Function and Constituent Order Change in Malay. Los Angeles: UCLA dissertation.

Cumming, Susanna. 1995. Multifunctionality and the realization problem in modelling discourse production. Discourse, Grammar and Typology: Papers in Honor of John

Verhaar, ed. by W. Abraham, T. Givón and S. Thompson, 247-273. Amsterdam:

John Benjamins.

Cumming, Susanna, and Fay Wouk. l987. Is there ‘discourse transitivity’ in Austronesian languages? Lingua 71:271-296.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1995. Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Du Bois, John. 1987. The discourse basis of ergativity. Language 63:805-855.

Dyen, Isidore. 1990. Homomeric lexical classification. Linguistic Change and

Reconstruction Methodology, ed. by Philip Baldi, 211-270. Berlin: Mouton de

Gruyter.

Givón, Talmy. 1983. Topicality in Discourse: A Quantitative Cross-linguistic Study. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Givón, Talmy. 1992. The grammar of referential coherence as mental processing instructions. Linguistics 30:5-55.

Givón, Talmy. 1994. The pragmatics of de-transitive voice: Functional and typological aspects of inversion. Voice and Inversion, ed. by Talmy Givón, 3-45. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Givón, Talmy (ed.). 1994. Voice and Inversion. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

692

Holmer, Arthur. 1999. Structural implications of the function of instrumental focus in Seediq. Selected Papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian

Linguistics, ed. by E. Zeitoun and Paul Li, 423-453. Taipei: Institute of Linguistics

(Preparatory Office), Academia Sinica.

Hopper, Paul. 1979. Aspect and foregrounding in discourse. Discourse and Syntax, ed. by Talmy Givón. New York: Academic Press.

Hopper, Paul. 1982. Aspect between discourse and grammar. Tense-aspect: Between

Semantics and Pragmatics, ed. by P. Hopper, 3-18. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hopper, Paul. 1986. How ergative is Malay? Studies in Austronesian Linguistics, ed. by Richard McGinn, 441-454. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Hopper, Paul, and Sandy Thompson. 1980. Transitivity in grammar and discourse.

Language 56:251-299.

Huang, Lillian M. 1993. A Study of Atayal Syntax. Taipei: The Crane Publishing Co. Huang, Lillian M. 1995. A Study of Mayrinax Syntax. Taipei: The Crane Publishing Co.. Huang, Shuanfan. (In preparation). A Functional Grammar of Tsou.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei, Cheng-hwa Tsang, Ying-kuei Huang, Dah-an Ho, and Chiu-yu Tseng (eds.). 1995. Austronesian Studies Relating to Taiwan. Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1997. A syntactic typology of Formosan languages—Case markers on nouns and pronouns. Chinese Languages and Linguistics IV: Typological Studies of

Languages in China, ed. by Chiu-yu Tseng, 343-378. Taipei: Institute of History

and Philology, Academia Sinica.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1999. The Linguistic History of Formosan Aborigines. Nantou: The Historical Research Commission of Taiwan Province. (in Chinese)

Payne, Thomas. 1994. The pragmatics of voice in a Philippine language: Actor-focus and goal-focus in Cebuano narrative. Voice and Inversion, ed. by Talmy Givón. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ross, Malcolm. 1995. Proto-Austronesian verbal morphology. Austronesian Studies

Relating to Taiwan, ed. by Li et al., 729-765. Taipei: Institute of History and

Philology, Academia Sinica.

Shibatani, Masayoshi. 1988. Passive and Voice. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Starosta, Stanley. 1988. A grammatical typology of Formosan languages. Bulletin of the

Institute of History and Philology 59:541-576.

Starosta, Stanley. 1995. A grammatical subgrouping of Formosan languages.

Austronesian Studies Relating to Taiwan, ed. by Li et al., 683-726. Taipei: Institute

of History and Philology, Academia Sinica.

Starosta, Stanley. 1997. Formosan clause structure: Transitivity, ergativity and case marking. Chinese Languages and Linguistics IV: Typological Studies of Languages

693

in China, ed. by Chiu-yu Tseng, 125-154. Taipei: Institute of History and Philology,

Academia Sinica.

Starosta, Stanley, Andrew Pawley, and Lawrence Reid. 1982. The evolution of focus.

Papers from the Third International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, vol. 2: Tracking the Travelers, ed. by A. Halim et al., 145-170. Canberra: Pacific

Linguistics.

Tseng, Chiu-yu (ed.). 1997. Chinese Languages and Linguistics IV: Typological Studies

of Languages in China. Symposium Series of the Institute of History and Philology,

Academia Sinica, No.2. Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica.

Wouk, Fay. 1986. Transitivity in Toba Batak and Tagalog. Studies in Language 10:391-424.

Wouk, Fay. 1996. Voice in Indonesian discourse and its implications for theories of the development of ergativity. Studies in Language 20:361-410.

Wouk, Fay. 1999. Sasak is different: A discourse perspective in voice. Oceanic

Linguistics 38:91-114.

[Received 7 November 2001; revised 31 March 2002; accepted 15 April 2002] Graduate Institute of Linguistics

National Taiwan University 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Road Taipei 106, Taiwan sfhuang@ms.cc.ntu.edu.tw

694