Kaohsiung, Taiwan

An exploratory study of the role of corporate accounts in business travelers’

choice of hotels: A case of Kaohsiung, Taiwan

1Lichang Lee2 I-Ang Wang3 Gary Howat4

Abstract

This study examined the role of corporate accounts as an intermediary for business travelers in choosing hotels. From a relationship marketing perspective, it is argued that the hotel’s relationships with these companies are a major factor. Data were collected from the key person of companies with substantial hotel room nights demand in Southern Taiwan. The findings show that the company background characteristics (location, nationality, booking channels, etc.) and some characteristics of the respondents influence the role of relationships in choosing hotels. The results suggest that when a close relationship is possible to be formed and when the company’s background characteristics allow for relationships to be developed with the hotels, relationships become important. When relationships are difficult to be nurtured, instead of focusing on relationship marketing, hotels should focus on marketing strategies such as brand name recognition and image. The evidence, however, requires further investigation.

Keywords: business travelers, hotel choice, relationship marketing, role of corporate accounts

1 The authors wish to thank National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences for research grant, NKUAS-93-TM-001, for supporting this project.

2 Assistant professor, Department of Tourism, National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences.

lichang@cc.kuas.edu.tw .

3 Previously Manager for Sales Department, and currently Manager for Front Desk, Grand Hi-Lai Hotel, Kaohsiung.

4 Associate professor, Department of Sports and Recreation Management, University of South Australia, Australia.

1. Introduction

Customer satisfaction with hotels and how it affects business travelers’ choice of hotels has been widely studied (e.g., Getty and Thomson, 1994; Gundeersen et al., 1996; Oh and Parks, 1997). Research has identified factors that lead to customer satisfaction and hotel choice intention such as: staff service quality (Choi and Chu, 2001; Verma et al., 2002), guest rooms, general amenities, dining options, hotel management and operations, architecture and design (Siguaw and Enz, 1999a, 1999b), and incentives (Moskowitz and Krieger, 2002), value (Rushmore and Goldhoff, 1997), security (Graham and Roberts, 2000), and even availability of smoking rooms (Field, 1999), among others.

Although customer satisfaction and each of the above mentioned factors are all important, satisfaction does not necessarily lead to loyalty (Bowen and Shoemaker, 1998). There are ‘satisfied switchers’ and ‘unsatisfied stayers’, and business travelers

were ‘the least satisfied, least loyal, and least involved of the guest segments’

(Skogland and Siguaw, 2004). Skogland and Siguaw also indicated that “…even the most satisfied and loyal customers might still switch for reasons beyond the control of the firm and even of the customer…,” (2004:6) and thus suggested that efforts for retention and loyalty should be targeted to customers other than business travelers.

The questions remain: How to target business travelers for retention and whom should be targeted? What might be the factors that are beyond the control of the firm and of the customers? The purpose of this study is to examine the factors that influence how corporate accounts choose or not choose a hotel. We argue that corporate accounts are an essential intermediary of business travelers for hotels, and that relationships between hotels and the

corporate accounts play an important role in business travelers’ choice of hotels. More specifically, this study aims to

Kaohsiung, Taiwan

on business travelers’ hotel choosing process: how the background variables of the corporate accounts and the

demographic variables of the key person influence factors such as service, price, and location of the hotels;

2. examine how relationships between the company officials (e.g. secretaries responsible for travel arrangements of staff) and the hotels affect the choice of hotels;

3. outline possible differences between how business travelers and how corporate accounts choose hotels.

2. Literature review

2.1. Corporate accounts and business travelers

In the research literature on hotel choice, the role of corporate accounts has been missing. Studies have reported the importance of ‘intermediaries’, – such as

travel agents and meeting planners, and have pointed out the important role of these intermediaries (Dubé and Renaghan, 2000; Medina-Muñoz and García-Falcón, 2000). Another intermediary, arguably as or even more important for many hotels, corporate accounts, is rarely mentioned in the hotel research literature. By corporate accounts, we refer to “the companies with which the business travelers are associated or

affiliated.” According to Ojasalo, proper management of the relationships with these key accounts (KAM), which is a

business-to-business marketing approach, “… provides an effective, practical and rather simple method for companies

interested in increasing their profits by right customer and relationship management.” (2002:269) These key accounts also make up effective word-of-mouth networks, which are especially important for the hospitality industry seeking long-term customer relationships (Storbacka et al., 1994). Moreover, it is also much more feasible for the ‘personalization of services’ (Kokko and

Moilanen, 1997) with proper management of corporate accounts than trying to build direct relationships with each and every business traveler. The importance of corporate accounts for hotels cannot be overstated.

The definition of ‘business travelers’ is also ambiguous. Business travelers are more than just travelers who do businesses. Business travelers may include the company employees, patrons, the buyers, the

franchisees, and any stakeholder of the company. Business travelers are a very complicated cluster of customers, have very different backgrounds and preferences (Fisher, 1998; Withiam, 1998; McGuire, 1999; McCleary et al., 1994), and also expectations (Moskowitz and Krieger, 2002; Foster and Botterill, 1995). While business travelers are very diversified people, the companies with which they are associated or affiliated are often directly responsible for these business travelers’ hotel reservations. The way different companies arrange the hotel reservations for their business travelers

tends to vary. Many larger companies and almost all multi-national enterprises have designated personnel responsible for travel related matters. Some even have their own travel agency. Therefore, even if these corporate accounts can be treated as customers and hence their satisfaction and preferences do matter, the behavior patterns of these corporate accounts at the

organizational level should still be of interest and of importance to researchers of hotel choice determinants. Thus, while our interest is also in business travelers, our focus and research population is the corporate accounts or their delegates.

2.2. Relationship marketing

The sales and marketing staff for many hotels, chains or independents, city or resort, large or small, tend to devote a significant portion of their efforts to working and maintaining a close relationship with

corporate accounts. For many such staff this is their major work. Fournier et al. (2001)

Kaohsiung, Taiwan

have indicated that while relationship marketing has been advocated, few research efforts appear to have investigated the link between relationship marketing and business travelers’ choice of hotels. Bowen and Shoemaker’s (1998) discussions on the importance of relationships, with ‘benefit’ and ‘trust’ as the most important antecedents to customer commitment, is limited to the relationship between hotels and business travelers, without mentioning corporate accounts.

A definition of relationship marketing relevant for this research is: “A long-term marketing strategy which aims at

developing and enhancing continuous and enduring customer relationships…” (Grönroos, 1990:144) A related concept, ‘customer relationship management’ (CRM), is often discussed with relationship

marketing. However, while the former usually refers to the use of information technology in assisting customer data management, the latter conceptually refers to building long-term interactions and

cooperation. Therefore, the concept of relationship marketing is more relevant in the current study.

Hotels belong to the services industry, and therefore also depend on intensive interpersonal interactions as one of its

industry characteristics (Lovelock and Wirtz, 2006). Staff service quality is a long-term process, requiring lasting efforts (Lovelock, 2001). Interactions and relationships

between the hotel staff and their customers broadly conceived are themselves an important part of the hotels’ service quality. Thus, relationship marketing for hotels is important. The different levels of

relationship marketing include: firm to firm, person to person, and person to firm

(Iacobucci and Ostrom, 1995). While there are ‘transient’ travelers (this is usually how business travelers are considered), the relationship between corporate accounts and hotels tend to be relatively more stable. Corporate accounts, especially those with high room night demand, often negotiate reservations for their employees directly

with a limited number of designated hotels for their employees to stay, thus ensuring price and service stability and certainty (Ford, 1980). On the hotel’s side, and for any industry indeed, repeat travelers are the most efficient, stable, and important source of business. It cannot be overestimated how important the relationships with the

corporate accounts are to the hotels, and actually to any industry (Reichheld, 1993).

Imrie et al. (2002), by using a

Taiwanese sample, have demonstrated that the SERVQUAL model, which was initially developed using North American samples, appears to be subject to the cultural

influences of Taiwanese society: “An examination of our results … lends support to the contention that cultural values do indeed endow consumers with rules that guide service quality evaluation.” (2002:17). Such an argument is that, while service quality (and hence satisfaction) is important, how people of different cultures interpret

and perceive service quality may be different. The SERVQUAL model as

an instrument to measure service quality fails to address “…the integral nature of inter-personal relationships to Taiwanese life and business…” (p.13). In cultures such as that of Taiwan, or Japan, or any other East Asia countries, the significant nature of relationships is highlighted by Imrie et al. (2002:14): “… Notably the supporting behavioral aspects of interpersonal relations and trustworthy and honesty feature as important signals of the integrity of service personnel…” (p.14) Such a statement about cultural differences in evaluating staff service quality has important implications for relationship marketing. Accordingly, ‘relationship’ marketing may indeed be defined differently from culture to culture. In particular, relationships tend to be stressed more in Eastern society than in Western society, however defined. This may be even more so for Japanese compared to Chinese, as Japanese people are considered to have the most

Kaohsiung, Taiwan

sophisticated interpersonal

relationships in the world (Triandis, 1995). Japanese people are renowned for using rapport building as a

legitimate means for doing businesses. While this may also be true for some Western cultures, rapport or

relationships often have negative connotations or are deemed less important than other factors such as such as cost considerations. Thus, while relationship marketing has become an increasingly important topic in the marketing literature, it can be claimed that in a culture such as Taiwan, interpersonal relationships are deemed more important and more heavily stressed than in Western cultures. Such interpersonal

relationships are especially important for strengthening business

opportunities. The importance of relationships to Japanese and

Taiwanese people is relevant to this study, as most international business travelers in

Kaohsiung, Taiwan, are from Japan. While we have cited Skogland and Siguaw (2004) as noting that there are satisfied switchers and dissatisfied stayers, Ganesh et al. (2000) have reported that dissatisfied switchers are more loyal to the new companies. They have also reported ‘individual dimensions of service’ as the most important source for customer satisfaction. Relationships between the hotels and the corporate accounts, as argued above, are important indicators for customer satisfaction, and also for the understanding of the corporate accounts’ switching behavior.

3. Methodology

3.1. The sample

This study is based on data from the major hotels in Kaohsiung, the second largest port city in Taiwan. A study of hotels in a city like Kaohsiung is particularly

illustrative of how long-term and stable relationship marketing is important for hotels. There are no international hotel chains in this city, the majority of

reservations are made through local offices or branches of multi-national corporations,, and Japanese travelers are the major

international customers for almost all local hotels. Since the central reservation system does not play a significant role, the

relationships between the local offices and the hotels are very important in the

decision-making process in respect to hotel reservations.

The data were collected from

questionnaires distributed to key persons of corporate accounts, which regularly use hotels in the Kaohsiung area. These data were obtained from the sales department of the three major local participating hotels, which are usually seen as among the most important and confidential information of any hotel. Most included companies have 100 annual room nights demand or more in the Kaohsiung area, some have thousands.

Of the 573 questionnaires distributed (with return postage paid), only 172 valid questionnaires were returned, for a response rate of 30%. Such a response rate is not unusual for mail surveys (see e.g., Singleton, Jr. et al., 2004). However, efforts to increase the return rate included follow-up phone calls, and a second copy of the

questionnaires being sent when the original could not be located for those who

expressed their willingness to reply. During this process, ‘relationship’ demonstrated its power - for those with whom the second author has direct connections, the return rate was higher. Otherwise it was relatively low, especially for respondents in Taipei, at the other end of the island (22 out of 180). While the low return rate limits the generalizability of the findings, those who did return questionnaires were companies that have substantial business with

Kaohsiung hotels, and are actually much sought after by local hotels.

Kaohsiung, Taiwan

The questionnaire consisted of three major sections. The first section was designed to capture demographic

information (gender, age and seniority of the respondents) and background information about the companies and their relationships with the hotels in Kaohsiung (eg who from the company books the hotel

accommodation, average annual room nights of accommodation used by the company, company budgets for

accommodation, location of the company headquarters, whether a Japanese company or not, and number of hotels with which the company has signed contracts). The lack of previous research linking these factors related to corporate accounts and their officials means that the research reported in this study is exploratory in nature.

The importance of Japanese companies in this study is two fold. First, Japanese make up a significant proportion of foreign travelers to Kaohsiung. Second, while Japanese tend to be difficult to initially gain

as a customer, their strong relationship orientation often results in their becoming loyal repeat customers.

The second section of the questionnaire consisted of, ‘emphasis of relationship’ scales, which are the core focus of this study. Since no such previous scale or index was available, we constructed the scale with 17 items aimed to cover the major components of relationships between the company and the hotel. These items were based on the first two authors’ professional experiences in interacting with corporate accounts.1 The scale for this section of the questionnaire was a seven-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree (1)’ to ‘strongly disagree (7). Reliability tests on 17 relationship items yielded Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.72. With the stepwise deletion of items D, M, L, (less relevant) O, and Q (ambiguous), the α eventually increased to a robust 0.89. The final scale is the remaining 12 items (Appendix 1).

1 Lewin and Johnston (1997) have discussed the dimensions of ‘relationship marketing,’ which usually include ‘relationship dependence,’ ‘trust,’ ‘commitment,’ ‘communication,’ ‘cooperation,’ and ‘equity.’ Our scale is based on the first two authors’ professional experiences interacting with corporate accounts key persons. A factor analysis of the 17 items in our scale does not show any significant dimensionality. This issue shall be further explored in future studies.

The third section of the questionnaire consisted of ‘choice’ items which included the reasons why the respondents choose or did not choose a hotel, including factors discussed earlier in this paper, such as services, guest room design, facilities, functional services, restaurants, quality, location, price, bathroom, etc. (Dubé e.g., Dube et al., 1999). The scale for this section of the questionnaire was a seven-point Likert scale ranging from ‘very important (7)’ to ‘not important at all (1)’.

3.3. Data analysis

The company background information and the respondents’ demographic information were mainly used as

independent variables, with the dependent

variables being the relationship variables and the choice variables. A list of

relationship variables can be found in Appendix 1. The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software.

4. Results

4.1. Background information for the corporate accounts, and demographic information for the respondents

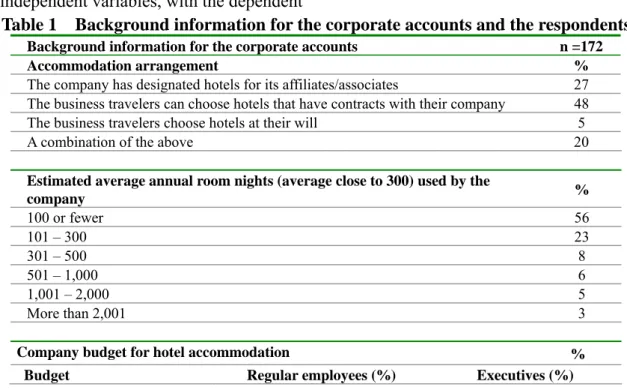

The descriptive statistics for the variables, including background, demographic,

and ‘choice’ variables are shown in Tables 1 and 2:

Table 1 Background information for the corporate accounts and the respondents

Background information for the corporate accounts n =172

Accommodation arrangement %

The company has designated hotels for its affiliates/associates 27 The business travelers can choose hotels that have contracts with their company 48 The business travelers choose hotels at their will 5

A combination of the above 20

Estimated average annual room nights (average close to 300) used by the

company % 100 or fewer 56 101 – 300 23 301 – 500 8 501 – 1,000 6 1,001 – 2,000 5 More than 2,001 3

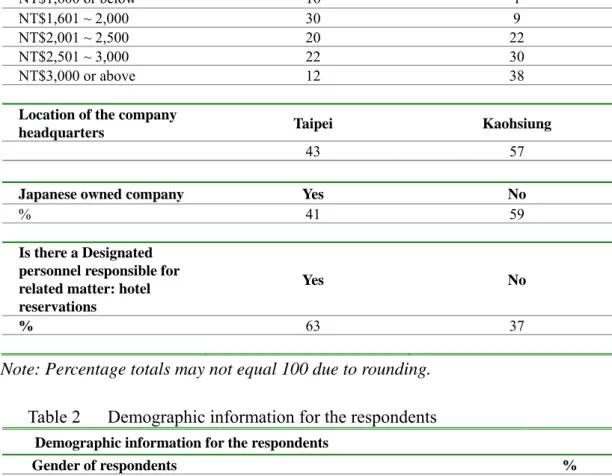

Kaohsiung, Taiwan NT$1,600 or below 16 1 NT$1,601 ~ 2,000 30 9 NT$2,001 ~ 2,500 20 22 NT$2,501 ~ 3,000 22 30 NT$3,000 or above 12 38

Location of the company

headquarters Taipei Kaohsiung

43 57

Japanese owned company Yes No

% 41 59

Is there a Designated personnel responsible for related matter: hotel reservations

Yes No

% 63 37

Note: Percentage totals may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Table 2 Demographic information for the respondents Demographic information for the respondents

Gender of respondents % Female 78% Male 22% Age (years) S.D. 38.55 (8.99) Seniority (years) S.D. 11 (8)

Number of hotels having signed contracts #

Average Number of contracts signed with hotels 7.32

Actual number of hotels regularly used 2.94

Note: Percentage totals may not equal 100 due to rounding. 4.2. Corporate accounts’ influence on

business travelers’ hotel choosing process:

the influence of the company

background variables and the demographic variables of the key person on factors

such as service, price, and location of the hotels can be discussed and illustrated as the following figures:

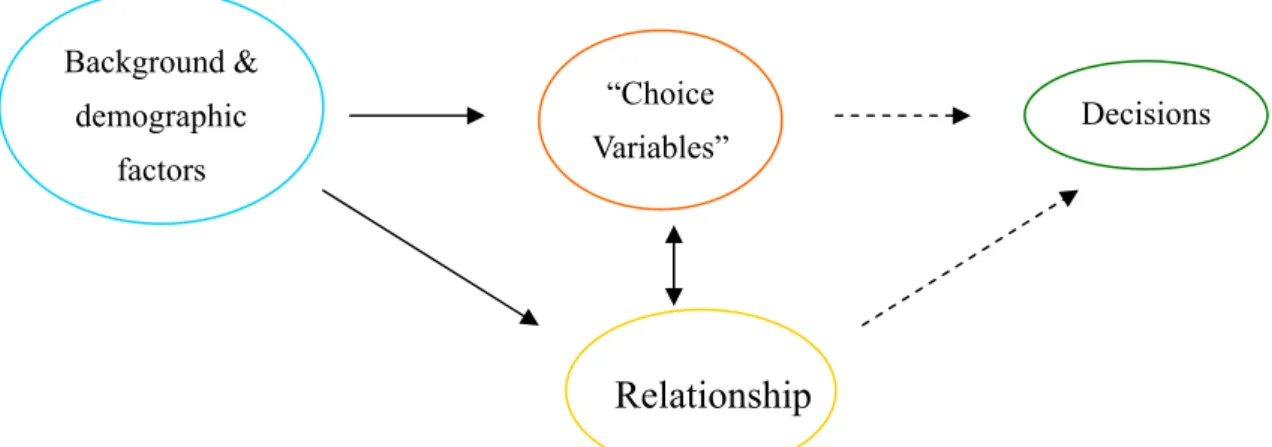

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual basis of this section:

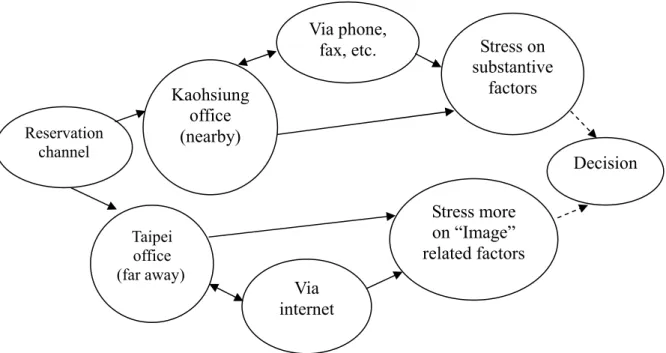

Figure 1: Influences of background & demographic factors on “choice variables” Additionally, there are some interesting

patterns that influence on hotel choice. As illustrated in Figure 2, two apparently

different patterns between those who reserve through the Kaohsiung office and those who reserve through the Taipei office, emerge when considering the following correlations: “reservation made mainly by the Kaohsiung

office” tend to reserve by phone or fax (r = 0.245*), while “reservation mainly by Taipei office” tend to reserve via internet (r = 0.256*), and “reservation mainly by the traveler themselves” tend to be made by package (r = 0.304*), hotel website (r = 0.366**), and other website (r = 0.311*).

Figure 2: The paths through which different reservation channels influence tools of reserving

Background & demographic factors “Choice Variables” Decisions Reservation channel Kaohsiung office (nearby) Taipei office (far away) Via phone,

fax, etc. Stress on substantive factors Via internet Stress more on “Image” related factors Decision

Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Table 3 Correlations between ‘choice’ variables” and ‘background’ variables

Factors that influence hotel choice Reservations made

by Kaohsiung office Price consideration 0.219* Management quality 0.214* Facilities 0.175* Bathroom 0.190* Guest room 0.214* Dining options 0.242* Internet access 0.164* Business functions 0.211* Cleanliness 0.174* Quietness 0.207* Service quality 0.266* Service attitude 0.197*

Factors that influence hotel choice Reservation by phone, fax,

or e-mail Service quality 0.165* Management quality 0.185* Facilities 0.156* Guest room 0.157* Dining options 0.197* Internet access 0.184* Cleanliness 0.240* Security 0.182* Quietness 0.181* Service efficiency 0.239* Service attitude 0.189*

Factors that influence hotel choice Reservation by package

(hotel + flight ticket)

Chains 0.271* Brand/name 0.184* Fitness facilities 0.176* Swimming pool 0.249* Traffic inconvenience 0.239* Bad service 0.174* Insufficient facilities 0.188*

Factors that influence hotel choice Reservations via hotel

website Chains 0.241* Fitness facilities 0.192* Swimming pool 0.307** Location 0.203* Poor service 0.180* Facilities 0.214* Unfamiliarity 0.184*

Factors that influence hotel choice Reservations via other website Chains 0.268* Fitness facilities 0.200* Swimming pool 0.274* Location 0.247* Poor service 0.221* Insufficient facilities 0.208* Unfamiliarity 0.272* **Significant at p<.001 *Significant at p<.05

The correlations in Table 3 indicate that those who make reservations via the internet place more emphasis on factors such as chains, brand names, and interestingly fitness facilities and swimming pools. We speculate that these factors are more related to ‘image’ conceptually. This is probably due to distance, therefore name recognition and image become important factors in choosing hotels. When local offices control

reservations, however, the emphasis is on more tangible factors, such as services. Such a pattern of consumer behavior has

implications for the hotel marketing department, which will be discussed later.

There are other significant correlations, such those between age and seniority (length of time employed in the company) and ‘choice’ variables as shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Correlations between ‘choice’ variables and demographic variables

Factors that influence hotel choice Age

Service Quality 0.169* Brand/Name Recognition 0.203* Management Quality 0.165* Luxuriousness 0.261* Fitness Facilities 0.166* Price 0.198* Location 0.278*

Factors that influence hotel choice Seniority

Service Quality 0.165* Brand/Name Recognition 0.248* Luxuriousness 0.229* Bathroom 0.208* Fitness Facilities 0.167* Swimming Pool 0.197* Relationship Building 0.159* Management Quality 0.216* **Significant at p<.001 *Significant at p<.05

Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Age and seniority are significantly correlated with many other variables, and most of the reasons are yet to be explored. Are older people more discerning or careful, or what? Also, the popular belief that

females tend to emphasize relationships more than males, is not confirmed by our data.

From the above tables and figures, we can tentatively conclude that both of the choice variables on the hotel side and

background/demographic variables on the company side have an impact on hotel choice. The situation is often contingent in that it depends on who are the two parties engaged in the interactions. Different hotels should find their own niche, and understand that different types of businesses may have a certain pattern in choosing hotels. Thus there is some evidence for the first research question, although the conclusion is far away from definitive. It is clear, however, that both the hotels and the companies have their patterns of choosing hotels. It would be to the hotels’ benefit for further research to

be conducted in this area.

4.3. How relationships between the company officials (e.g. secretaries responsible for travel arrangements of staff) and the hotels affect the choice of hotels

While we do not have sufficient measures to test whether relationship-building is constructive for hotel-choosing, our relationship variables do show their relevance to background information and thus demonstrate how they are related to variables that have an impact on

hotel-choosing, as illustrated in Tables 5 to 7. It appears that relationships are especially important for some types of companies more so than for others. Relationships appear to be more important for: Japanese companies, those companies that choose hotels for their employees, those companies with a higher room night demand, those companies that who reserve via the local office, and those companies with their main office in

Kaohsiung. Figure 3 portrays the

relationship between the three major groups

of variables.

Figure: A Conceptual framework for the relationship between the three major groups of variables

Table 5 T-test for relationship-related constructs for two independent means

Japanese company Yes No t Relations 74.11 70.60 2.061* Travelers make reservation by themselves 5.6 4.04 4.162** Emphasis on relationship with sales 2.72 3.54 -2.713*

Company choose hotel

Yes No Relations 74.27 70.93 1.917 (0.057) Relationships with the hotel 1.93 2.29 -1.926 (0.056) Reserve via Kaohsiung office 1.33 2.08 -3.343*

Reserve hotel + air

ticket package 5.04 4.01 3.044* **Significant at p<.001 *Significant at p<.05

Relationship

Background & demographic factors “Choice Variables” DecisionsKaohsiung, Taiwan

Table 6 Correlations between relationship-related constructs and annual room nights

Relationship-related iItems Annual room nights

Importance of Interaction With Hotel in Considering Hotels 0.207* Relationship with Hotel in Making Decision 0.161*

Not Choose a Hotel for Bad Management 0.201*

Hotel Reward Programs -0.196*

Department Stores -0.198*

Reserve via Kaohsiung office

“Relations” scale 0.225**

**Significant at p<.001 *Significant at p<.05

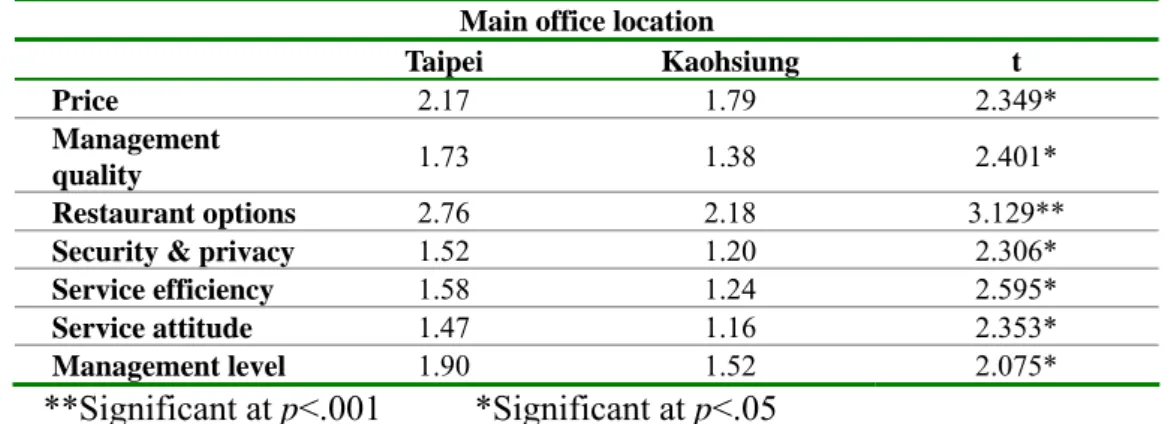

Table 7 T-test on ‘choice’ variables” by background/demographic factors for two independent means

Main office location

Taipei Kaohsiung t

Price 2.17 1.79 2.349*

Management

quality 1.73 1.38 2.401*

Restaurant options 2.76 2.18 3.129**

Security & privacy 1.52 1.20 2.306*

Service efficiency 1.58 1.24 2.595*

Service attitude 1.47 1.16 2.353*

Management level 1.90 1.52 2.075*

**Significant at p<.001 *Significant at p<.05

Smaller number means higher concern

4.4. Differences between how business

travelers and how corporate accounts choose hotels

While research on corporate accounts is rare, research on business travelers is more prevalent. By comparing our findings for corporate accounts with that for business travelers, we may be able to yield some preliminary results that warrant further investigation. Dubé et al. (1999) has shown that business travelers rank the following items as important factors in choosing hotels by order:

1. Service / Interpersonal Interaction 2. Guest Room Design/ Amenities 3. Building (Outlook and Public Area) 4. Functional Service/Facilities

5. Restaurant related Facilities 6. Quality Standard

7. Location 8. Price

9. Bathroom Furniture and Amenities Similar as well as different findings about corporate accounts can be found in our study.

Compared to Dubé et al. (1999) the pattern of responses in our study was more

complicated. We had five groups of questions asking the respondents to rate their priority in choosing hotels. These five groups of questions and their ranking by the respondents are as follow: ‘Importance of

factors in choosing hotels – general issues’

(1. staff service quality, 2. management quality, 3. location, 4. price, 5. facilities, 6. relations, 7. request by traveler, 8. brand name, 9. reward program, and 10. chains), ‘

Importance of factors in choosing hotels – facilities’ (1. guest room, 2.

business function, 3. internet access, 4. bathroom, 5. dining option, 6. luxuriousness, 7. fitness center, 8. swimming pool),

Importance of qualities in choosing hotels – software’ (1. cleanliness, 2.

quietness, 3. service attitude, 4. security & privacy, 5. service efficiency, 6.

management, 7. rapport), ‘Reasons for not

choosing a hotel’ (1. service, 2. location, 3.

management problem, 4. facilities, 5. price, 6. unfamiliarity), and ‘Reasons for

recommending a hotel’ (1. familiarity, 2.

location, 3. price, 4. department stores, 5. relations, 6. reward program).

In our results staff service quality tends to be a high priority, which is consistent with Dubé et al.’s findings. Guest room is ranked top on the ‘hardware’ (facilities) group. Location and price are ranked relatively low by Dubé et al., but not so much in ours. The reasons may be due to sample differences. There is an important difference between the

literature (Gundeersen et al., 1996) and our research. The subjects of our research

were company key persons, not business travelers. They are the company persons

responsible for the business travelers’ hotel reservation, and very often, they make decisions for business travelers.

It is also interesting to note, that while the relationship variable ranked fifth and sixth in our research, ‘interpersonal’ ranks on the top for the Dubé et al. (1999) research. There are three possible reasons for this. First, those respondents in the cited work were business travelers who actually stayed at the hotels, and accordingly interpersonal relationships tend to be more important for them. Second, relationships may also be considered as included in the ‘service/social’ variables. Third, while our respondents were almost all Taiwanese, the respondents in the Dubé et al. (1999) research were mostly Americans. The interpersonal/social variable may convey different cultural implications. The most intriguing is that, while

‘unfamiliarity’ is ranked bottom for ‘Reasons for not choosing a hotel,’

‘familiarity’ is ranked top for ‘Reasons for recommending a hotel.’ Familiarity can be considered as a requisite of relationships, thus we speculate that relationships are crucial in selecting hotels. The most likely explanation then, is that relationships usually convey a positive interaction between the two parties. Finally, it may be

Kaohsiung, Taiwan

worth noting that business functions and internet access are ranked high in the

facilities list. These are non-traditional items for hotels, and are relatively less studied until recently.

5. Discussions and conclusions

While further research is needed to make more definitive and more generalizable conclusions, tentative conclusions can be drawn from the above results and

discussions. As seen from the above analyses, structural factors have important and different impacts on how corporate accounts choose hotels and how

relationships matter, and in what way. Bendapudi and Berry (1997) have reported that customers have different motivations for maintaining relationships with service providers, as either by constraints or by dedications. Our findings have shown variables such as age and seniority of the respondents, annual room nights demand of the corporate accounts who choose the hotel (company or traveler), where the main offices of corporate accounts are located, and whether or not the company is Japanese owned, do make a difference. These

findings tend to be mainly structural, and thus are more of constraints than dedications.

However, on the one hand, our measure of relationships can be considered a substitute measure of dedications, and on the other hand, the two motivations (constraints and dedications) as mentioned by Bendapudi and Berry often happen together and indeed intertwine with each other.

Therefore, in studying the issues of hotel choice, these structural factors should not be overlooked. However, a study in Kaohsiung may be different from one in New York, or Hong Kong. As well, other factors such as the gender of sales representatives and the interaction with gender of the customers, as suggested by Fischer et al. (1997), might also make a difference. However, the gender of the key persons representing the

corporate accounts in our study did not make a difference. Other limitations of this study include possible sampling bias due to the low return rate. Another point to note is that service has been ranked high in all our responses, and because service has a direct influence on customer satisfaction

(McDougall and Levesque, 2000), this may indicate that customer satisfaction remains a legitimate priority in choosing hotels.

Lastly, while our study focuses on the consumers’ attitudes and behaviors, the findings also have implications for hotels’ marketing approaches. Our findings have shown that relationships are important in the

way that they can be developed and nurtured. In our analyses, seniority, annual room

nights demand, who chooses the hotels, Japanese companies or not, and whether the reservation is made through the Kaohsiung office, are all significantly related to the relationship variables. These results imply that, when it is possible to build a

relationship (or rapport) and when the organizational culture is suitable for developing long-term relationships, relationships become important. When relationships are difficult to develop due to distance or lack of knowledge, or the

variability of the customer base (Fyall et al., 2003), instead of focusing on relationship marketing, hotels should focus on marketing approaches such as brand name recognition and image.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank National

Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences, for its research grant NKUAS-93-TM-001. They also wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers.

References

Armstrong, R.W., Mok, C., Go. F.M., & Chan, A. (1997). The importance of cross-cultural expectations in the measurement of service quality perceptions in the hotel industry.

International Journal of Hospitality Management 16 (2), 181-190.

Bowen, J.T. & Shoemaker, S., (1998). Loyalty: A strategic commitment. Cornell

Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 39 (1), 12-25.

Bendapudi, N. & Berry, L.L. (1997). Customers’ motivations for maintaining relationships with service providers.

Journal of Retailing 73 (1), 15-37.

Choi, T.Y. & Chu, R. (2001). Determinants of hotel guests’ satisfaction and repeat patronage in the Hong Kong hotel industry. International Journal of

Hospitality Management 20 (3), 277-279.

Dubé, L., Enz, C.A., Renaghan, L.M., & Siguaw, J. (1999). Best practices in the U.S. lodging industry: overview, methods, and champions. Cornell Hotel and

Restaurant Administration Quarterly 40

(4), 14-27.

Dubé, L. & Renaghan, L.M. (2000). Marketing your hotel to and through intermediaries: an overlooked best practice. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant

Administration Quarterly 41(1), 73-83.

Field, A. (1999). Clear air at night. Cornell

Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 40(1), 60-67.

Fisher, C. (1998). Business on the road.

American Demographics 20 (6), 44-54

Fischer, E., Gainer, B., & Bristor, J. (1997). The sex of the service provider: does it influence perceptions of service quality?

Journal of Retailing 73 (3), 361-382.

Ford, D. (1980). The development of buyers-sellers relationships in industrial Markets. European Journal of Marketing

14, 339-354.

Foster, N., Botterill, D., 1995. Hotels and the businesswoman: A supply-side analysis of consumer dissatisfaction. Tourism Management 16 (5), 389-397.

Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Fournier, S., Dobscha, S., & Mick, D.G. (2001). Preventing the premature death of relationship marketing. Harvard Business

Review on Customer Relationship Management. Harvard Business School

Press, Boston, MA.

Fyall, A., Callod, C., & Edwards, B. (2003). Relationship marketing: the challenge for destinations. Annals of Tourism Research

30 (3), 644-659.

Ganesh, J., Arnold, M.J., & Reynolds, K.E. (2000). Understanding the customer base of service providers: an examination of the differences between switchers and stayers. Journal of Marketing 64 (3), 65-87.

Getty, M.J. & Thomson, N.K. (1994). The relationship between quality, satisfaction, recommending behavior in lodging decisions. Journal of Hospitality &

Leisure Marketing 2 (3), 8.

Graham, T.L. & Roberts, D.J. (2000). Qualitative overview of some important factors affecting the egress of people in hotel fires. International Journal of

Hospitality Management 19 (1), 79-87.

Grönroos, C. (1990). Service Management

and Marketing: Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition.

Lexington Books, New York, NY. Gundeersen, G.M., Heide, M., & Olsson,

H.U. (1996). Hotel guest satisfaction among business travelers. Cornell Hotel

and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 37 (2), 72-91.

Iacobucci, D. & Ostrom, A. (1996). Commercial and interpersonal relationships: using the structure of interpersonal relationships to understand individual-to-individual,

individual-to-firm, firm-to-firm

relationships in commerce. International

Journal of Research in Marketing 13,

53-72.

Imrie, B.C., Cadogan, J.W., & McNaughton, R. (2002). The service quality construct on a global stage. Managing Service

Quality 12 (1), 10-18.

Kokko, T. & Moilanen, T. (1997).

Personalization of services as a tool for more developed buyer-seller interactions.

International Journal of Hospitality Management 16 (3), 297-304.

Levine, J.E. & Johnston, W.J. (1997).

Relationship marketing theory in practice: A case study. Journal of Business

Research 39, 23-31.

Lovelock, C.A. (2001). A retrospective commentary on the article ‘New tools for achieving service quality. Cornell Hotel

and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 42 (4), 39-46.

Lovelock, C.A. & Wirtz, J. (2006). Services

Marketing: People, Technology, Strategy,

Prentice Hall International Editions. McCleary, K.W., Weaver, P.A., & Lan, L.

(1994). Gender-Based Differences In Business Travelers' Lodging Preferences.

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant

Administration Quarterly 35 (2), 51-58.

McDougall, G.H., & Levesque, T. (2000). Customer satisfaction with service: Putting perceived value into the equation.

Journal of Services Marketing 14(5),

392-410.

McGuire, T. (1999). A pleasure doing

business. American Demographics 21 (1), 18.

Medina-Muñoz, D. & García-Falcón, J.M. (2000). Successful relationships between hotels and Agencies. Annals of Tourism

Moskowitz, H. & Krieger, B. (2002). Consumer requirements for a mid-priced business hotel: Insight from analysis of current messaging by hotels. Tourism and

Hospitality Research 4 (3), 268-288.

Oh, H. & Parks, C.S. (1997). Customer satisfaction and service quality: a critical review of the literature and research implications for the hospitality industry.

Hospitality Research Journal 20 (3),

36-64.

Ojasalo, J. (2002). Key account

management in information-intensive services. Journal of Retailing and

Consumer Services 9, 269-276.

Petrof, J.V. (1997). Relationship marketing: the wheel reinvented? Business Horizons

40 (6),26-31.

Reichheld, F.F. (1993). Loyalty-Based Management. Harvard Business Review

71, 64-73.

Rushmore, S. & Goldhoff, G. (1997). Hotel value trends: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant

Administration Quarterly 38 (5), 18-29.

Siguaw, J.A.& Enz, C.A. (1999a). Best Practices in Hotel Operations. Cornell

Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 40 (4), 42-53.

Siguaw, J.A. & Enz, C.A. (1999b). Best Practices in Hotel Architecture. Cornell

Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 40 (5), 45-49.

Singleton, Jr., R.A. & Straits, B.C. (2004).

Approaches to Social Research. Oxford

University Press, New York, NY. Skogland, I. & Siguaw, J.A. (2004).

Understanding Switchers and Stayers in the Lodging Industry. CPR Report,

School of Hotel Administration, Cornell

University 4 (1).

Storbacka, K., Strandvik, T., & Grönroos, C. (1994). Managing customer relationships for profits: the dynamics of relationship quality. International Journal of Service

Industry Management 5 (5), 21-38.

Triandis, H.C. (1995). Individualism &

Collectivism. Westview Press, Boulder,

Colorado.

Verma, R., Plaschka, G., & Louviere, J.J. (2002). Understanding customer choices: a key to successful management of hospitality services. The Cornell Hotel

and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 43 (6), 15-24.

Withiam, G. (1998). Studying women business travelers. Cornell Hotel and

Restaurant Administration Quarterly 39

Kaohsiung, Taiwan