國立交通大學

英語教學研究所碩士論文

A Master Thesis Presented to Institute of TESOL, National Chiao Tung University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Master of Arts

一探國際演講協會成員之參加動機、自我評估學習成效、與

心得感知

An Exploration Study of Toastmasters Clubs in Taiwan: Members’

Motivation, Self-Perceived Improvement, and Overall Perception

研究生: 韓佩真

Graduate: Pei-Chen Han

指導教授: 孫于智 博士

Advisor: Dr. Yu-Chih Sun

中華民國 一百 年 七 月

論文名稱:一探國際演講協會成員之參加動機、自我評估學習成效、與心得感知 校所組別:交通大學英語教學研究所 畢業時間:九十九學年度第二學期 指導教授:孫于智博士 研究生:韓佩真

中文摘要

在台灣使用英文的需求近年來趨於普遍化,英語口說也被視為象徵個人能力 的一項專業(Darling and Dannels, 2003)。由於團體形式的學習最有助於達成學習 成效(Wenger, 1998),本研究探索以培訓成員公眾演說以及領導能力的國際演講 協會(Toastmasters Club)。研究對象為國際演講協會在台灣的兩個分會中成員, 一個為地區性分會,另一個為校園社團型分會,共五十六名。成員自發性加入的 動機、自我評估加入協會後的學習成效、以及全盤性的參與心得感知為本研究的 三大重點。本研究採用 Kruidenier 和 Cle´ment 在 1986 年提出的知識導向、工具 導向、旅遊導向、以及人際導向的動機以了解成員自發性加入的動機。學習成效 分為口說能力之構成要素(Shumin, 2008)和國際演講協會統一訂定的學習目標。自 信、自發性學習、歸屬感、和學習收穫用以探索協會成員加入後的心得感知。研 究者採用敘述性統計和多變量變異數分析來分析量性資料。質性資料則透過內容 分析法加以分析討論。 本研究結果發現國際演講協會是一個有效的學習團體。成員加入國際演講協 會主要為了學習英文以及英文演說,培養人際關係也為一項重要因素。成員在國 際演講協會當中感受到愉悅、溫暖的學習環境、以及對協會感到歸屬感,本研究 也發現加入較久的成員自我評估的學習成效較為顯著,英文的進步較為明顯。此 外,加入較久的成員也表示參加國際演講協會助於自信的提昇,和擁有較高的自 發性學習能力。 關鍵字:國際演講協會、學習社群、自主學習ABSTRACT

In recent years, the need to use English has become prevalent in Taiwan, and there has been a growing interest in English speaking because it has been considered as an important skill to represent in one’s level of professional resume (Darling and Dannels, 2003). It has been advocated that learning can be best achieved in the form of a community. The present study focuses on a specific learning community – Toastmasters (TM) Club in Taiwan that was created to help people to improve both public speaking ability and to develop leadership.

This study surveyed 56 participants from one regional TM club and one campus TM club. In order to investigate reasons which bring Taiwanese people to the club on a voluntary basis, Kruidenier and Cle´ment’s (1986) four orientations (knowledge, instrument, travel, and friendship) were used to understand TM members’ motivation to attend the club. The members also needed to self perceive their improvements after participating in TM meetings; the areas of improvements were categorized by

Shnmin’s (2008) components of speaking proficiency and the goals set up by

Toastmasters International (2010). Last, TM members’ overall perception of the value of the TM club were explored in regard to self-confidence, learning autonomy, sense of belonging, and perceived learning benefits. The quantitative data were interpreted by descriptive statistics and MANOVA, while the qualitative data were analyzed by content analysis.

The findings revealed that TM members essentially joined the club for knowledge-oriented motivation to learn English and public speaking;

friendship-oriented motivation was the second important factor for the development of interpersonal relationship. Also, a longer membership of TM was found beneficial to self-perceived improvement growth. Members who devote their time to regularly

participate in TM meetings believe that they gain greater improvements in English. Finally, the members can feel a pleasant learning environment and sense of belonging to TM, which showed that the TM club is an advantageous learning community. In addition, self-confidence and learning autonomy were found to be developed after a longer term of TM membership; however, there is no guarantee.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This thesis could not have been completed without many people’s help and encouragement.

First of all, I am grateful to have Dr. Yu-Chih Sun as my advisor, and I would like to thank her for the continuous support and guidance throughout the whole process of my thesis writing. Her penetrating and incisive opinions always help me to notice mistakes that I should not have made in the thesis and guide me to the real research field which is not like doing mini studies in any graduate courses. Also, I would like to thank her for her trust in me, which plays a very important role to push me to complete the thesis.

I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Shiou-Wen Yeh and Dr. Yu-Jung Chang for their valuable suggestions and advice to assist me in improving the quality and the coherence of my thesis.

I am also thankful for all the participants in this study including the TM members who helped me fill in the questionnaire and who took part in the interview session. Without their participation, this study could not have been done.

I would like to thank my cousins, Mujou Hsiao and Anny Hsiao’s proofreading, Michael Nicholas’ writing consultation, and Ant Lin’s statistics consultation. Their professional help undoubtedly accelerated my graduation. I would also like to thank my dear friend, Moe Wu, and my fake sister, Josy Yang, for their honest and joyful company and encouragement in the long way of my thesis writing.

Finally, I owe my deepest thanks to my dearest parents, sister, and brother for their never ending love and support. They are the most important people in my life, and to them I dedicate this thesis.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

中文摘要 ... i ABSTRACT... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ... ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ... iv LIST OF FIGURES... v LIST OF TABLES ... vCHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION ... 1

Overview of Toastmasters (TM) Club... 1

Communication Track and Leadership Track in TM Club... 4

Background of the Study ... 7

Purpose of the Study... 7

Significance of the Study ... 8

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW... 10

Situated Learning... 10

What is Situated Learning? ... 10

The Application of Situated Learning ... 11

Learning Community... 12

Psychological Sense of Community ... 12

Definition of Learning Community ... 13

Advantages and Disadvantages of Learning Community ... 14

Autonomous Learning ... 15

Definition of Autonomous Learning... 15

Components of Autonomy... 16

Motivation in Learning Autonomy... 19

Public Speaking ... 21

Public Speaking Needs in Class and in Workplace ... 21

Factors Affecting Public Speaking ... 22

Components of Public Speaking ... 23

CHAPTER THREE METHOD ... 25

Participants... 25 Data Collection... 26 Instrumentation... 27 The Questionnaire... 27 The Interview ... 30 Data Analysis ... 31

Qualitative Data Analysis ... 32

CHAPTER FOUR RESULTS & DISCUSSION... 33

RQ1: What is the participant’s motivation for attending the Toastmasters club?33 RQ2: What is the participant’s self-perceived improvement after attending the TM club? ... 40

RQ3: What is the participant’s overall perception of the value of Toastmasters club?... 50

CHAPTER FIVE CONCLUSION ... 70

Summary of Findings ... 70

Situated Learning and TM Member’s Motivation ... 70

PSOC and TM Members’ Self-Perceived Improvements ... 71

Autonomous Learning and Continuous TM Membership ... 72

Pedagogical Implications ... 72

Limitations of the Study and Future Research Recommendations ... 74

REFERENCES... 76

APPENDIXES ... 82

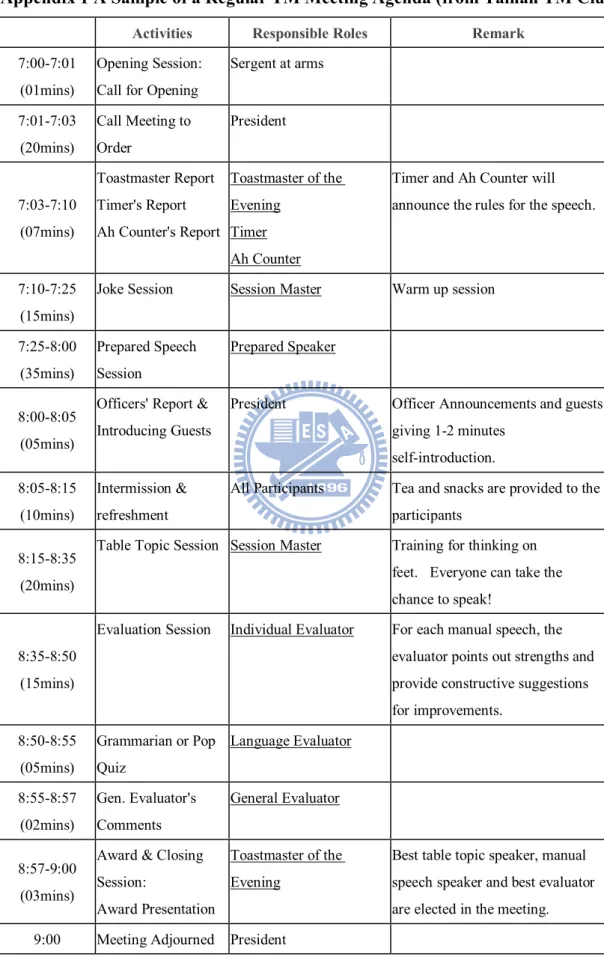

Appendix 1 A Sample of a Regular TM Meeting Agenda ... 82

Appendix 2 Duty Descriptions of Each TM Club Meeting Role ... 83

Appendix 3 The Competent Leader Manual ... 84

Appendix 4 Questionnaire (English version) ... 86

Appendix 5 Questionnaire (Chinese version) ... 91

Appendix 6 Interview Questions (English version) ... 95

Appendix 7 Interview Questions (Chinese version)... 96

Appendix 8 Interview Consent Form... 97

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 The Procedure to be a Distinguished Toastmaster In a TM Club (Toastmasters International, 2010) ... 4Figure 2 Littlewood’s (1996) Model of Components and Domains of Autonomy in Foreign Language Learning ... 17

Figure 3 Littlewood’s (1996) Framework for Developing Autonomy In and Through Foreign Language Learning ... 18

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 The Distribution of the Worldwide TM Club Members ... 2

Table 2 Ten Speech Projects in Competent Communicator (CC) Speeches ... 5

Table 3 Fifteen Manuals in Advanced Communicator (AC) Speeches ... 6

Table 4 The Relationship between Motivation and the Orientations ... 20

Table 5 Demographic Information of Participants... 26

Table 6 Background Information of the Interviewees... 30

Table 7 Themes for Interview Questions... 31

Table 8 The Distributed Relation of Research Questions and Research Instrument ... 31

Table 9 Descriptive Statistics for Motivation ... 33

Table 10 Descriptive Statistics for Motivation for Various TM Related Variables. 35 Table 11 Significant Levels for Motivation... 37

Table 12 Descriptive Statistics for Areas of Self-perceived Improvement ... 41

Table 13 Descriptive Statistics for Areas of Self-perceived Improvement for TM Related Variables ... 43

Table 14 Significant Levels for Areas of Self-perceived Improvement... 44

Table 15 Descriptive Statistics for Perceived Value of TM ... 52

Table 16 Descriptive Statistics for Perceived Value of TM According to Variables ... 53

Table 17 Significant Levels for Perceived Value of TM... 54

Table 18 Descriptive Statistics for Perceived Enjoyment and Perceived Usefulness of TM Meeting Sessions... 58

Table 19 Descriptive Statistics and Significant Levels for Perceived Enjoyment of TM Meeting Sessions for Regional and Campus TM Club Members... 59

Table 20 Correlation Analyses of Perceived Enjoyment and Perceived Usefulness of TM Meeting Sessions for Regional and Campus TM Club Members... 63

Table 21 Descriptive Statistics for Perceived Enjoyment and Perceived Usefulness of TM Meeting Roles ... 64

Table 22 Rank Order of Perceived Enjoyment and Perceived Usefulness of TM Meeting Roles ... 65

Table 23 Descriptive Statistics and Significant Levels for Perceived Enjoyment of TM Meeting Roles for Regional and Campus TM Club Members ... 67

Table 24 Correlation Analyses of Perceived Enjoyment and Perceived Usefulness of TM Meeting Roles for Regional and Campus TM Club Members ... 69

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

English is seen as a global language or “lingual franca” meaning a working language; it is used for people who speak different languages to communicate, and that’s why for the past centuries, English is known as an international language (Crystal, 2003). The need to use English has become prevalent in Taiwan, and an increasing number of people are eagerly seeking opportunities to practice English; these people either attend English institutes or go abroad. It has been advocated that learning can be best achieved in the form of a community (Wenger, 1998). Also, recently, there has been a growing interest in English speaking because it has been considered as an important skill to represent in one’s level of professional resume (Darling and Dannels, 2003). The present study focuses on a specific learning community – Toastmasters (TM) Club in Taiwan. Toastmasters (TM) Club was created to help people to improve both public speaking ability and to develop leadership. In order to investigate reasons which bring Taiwanese people to the club on a voluntary basis, TM members’ motivation, their self perception of improvement after participating in TM meetings, and their overall perception of the Toastmasters (TM) Club all are explored in the present study.

Overview of Toastmasters (TM) Club

Toastmasters (TM) Club is a non-profit educational organization established for people to develop and improve public speaking and leadership skills. It was first held by Dr. Ralph C. Smedley in 1932, in California with the aim of fostering members’ self-confidence as well as personal growth. The members were commonly native speakers of English; however, club membership now exceeds 260,000 members around the world in over 12,500 clubs in 113 countries. Among them, 15.5% of the

members are from Asia, and Table 1 shows the whole distribution of the worldwide membership (Toastmasters International, 2010).

Table 1

The Distribution of the Worldwide TM Club Members

Geographical Region Percentage

North America 72.00% (includes United States 59.6%.)

United States 59.60%

Asia 15.50%

Australia (includes Oceania) 6.50%

Europe 4.50%

Africa 1.25%

South America Less than 1.00%

In 1958, Taiwan had its first TM club in Taipei. To date, the organization in Taiwan has branched out 152 clubs in the country with more than 2, 000 memberships (Toastmasters International, 2010). TM clubs have been growing rapidly in Taiwan during the past 52 years providing an immersed English learning environment in the EFL context of Taiwan for the participants to devote leisure time to attend regular meetings. There are two types of TM clubs: regional clubs and campus clubs; regional TM clubs are localized for people including students, employees, and unemployed adults to join whereas campus TM clubs acts as extracurricular clubs in universities, and most members are students from the specific school.

Each TM club follows a formal pattern to hold a meeting including seven sessions:

(1) Introduction Session: it functions as an icebreaker at the beginning of a regular meeting and welcomes participants.

(2) Variety (Joke) Session: this session provides the audience with warm-up activities before Prepared Speech Session. Some of the activities include joke telling, idea sharing, and little games etc.

(3) Prepared Speech Session: in this session, speeches are prepared in advance in order to help the audience enhance their English listening ability and acquire various kinds of knowledge.

(4) Table Topic Session: it provides a good opportunity to deliver an impromptu English speech. A Table Topic Speech can be derived from questions, opinions, or ideas. For example, it could be answering question such as ‘what’s your most memorable travel experience?’ or ‘what’s your opinion on global warming’.

(5) General Evaluation Session: this session provides a chance for members to make general comments and evaluations of the meeting overall.

(6) Speech Evaluation Session: speech evaluators comment on individual prepared speeches. Speech evaluators offer advice to the prepared speakers for improvements to make on their future speeches; they also remind the audience of what to be aware when delivering speeches.

(7) Language Evaluation Session/Grammarian Report: speakers’ and individual evaluators’ common mistakes in speaking English are reported during this session. English speaking errors from aspects of grammar, pronunciation, and so on are noted.

A sample of a regular TM club meeting agenda is provided in Appendix 1. Also, roles in each meeting are assigned to different members in advance to take

responsibilities for holding a meeting, and an overview of each role’s duty is described in Appendix 2.

Communication Track and Leadership Track in TM Club

According to Toastmasters International (2001), the procedure for a new member of TM clubs to be trained as a distinguished toastmaster is shown in Figure 1. Two tracks represent the two goals in TM clubs. In the communication track, a new member entering the TM club has to accomplish a series of prepared speeches to advance from Competent Communicator (CC) speeches to Advanced Communicator (AC) speeches. On the other hand, in the leadership track, a new member moves from being a Competent Leader (CL) to an Advanced Leader (AL).

Figure 1 The Procedure to be a Distinguished Toastmaster In a TM Club (Toastmasters International, 2010)

In Competent Communicator speeches, dominated C1 to C10 (see Table 2) to be completed, and each speech generally lasts five to seven minutes. In Advanced

Competent Communicator Advanced Communicator Bronze Advanced Communicator Gold Advanced Communicator Silver New Member Competent Leader Advanced Leader Bronze Advanced Leader Silver Distinguished Toastmaster L ea de rs hi p T ra ck C om m uni ca tion T ra ck

Communicator speeches, there are three different levels: AC-Bronze (A1~A11), AC-Silver (A11~A20), and AC-Gold (A21~30). Each level also contains ten speeches, and in general, each speech lasts ten to fifteen minutes. According to personal

preferences and needs, members in the level of an Advanced Communicator can choose topics from the fifteen manuals (see Table 3) to give speeches.

Table 2

Ten Speech Projects in Competent Communicator (CC) Speeches (Dlugan, 2008) CC Speech Project Overview

C1 The Ice Breaker The first speech of the Toastmasters program is about

introducing yourself to your peers, providing a benchmark for your current skill level, and standing and speaking without falling over.

C2 Organize Your Speech

Introduces the basic concepts of organizing a speech around a speech outline.

C3 Get to The Point Clearly state your speech goal, and make sure that every element of your speech focuses on that goal.

C4 How to Say It Examines word choice, sentence structure, and rhetorical devices.

C5 Your Body Speaks

Shows how to complement words with posture, stance, gestures, facial expressions, and eye contact.

C6 Vocal Variety Guides you to add life to your voice with variations in pitch, pace, power, and pauses.

C7 Research Your Topic

Addresses the importance of backing up your arguments with evidence, and touches on the types of evidence to use.

C8 Visual Aids Examines the use of slides, transparencies, flip charts, whiteboards, or props.

C9 Persuade with Power

Discusses audience analysis and the different forms of persuasion available to a speaker.

C10 Inspire

Your Audience

The last of ten speeches, this project challenges the speaker to draw all their skills together to deliver a powerful inspirational message.

Table 3

Fifteen Manuals in Advanced Communicator (AC) Speeches (Toastmasters International, 2010)

No. 15 Manuals in AC Speeches 1 The Entertaining Speaker 2 Speaking to Inform 3 Public Relations

4 The Discussion Leader 5 Specialty Speeches 6 Speeches By Management 7 Professional Speaker 8 Technical Presentations 9 Persuasive Speaking 10 Communicating On Television 11 Storytelling 12 Interpretive Reading 13 Interpersonal Communication 14 Special Occasion Speeches 15 Humorous Speeches

In the leadership track, ten projects have to be done in order for a club member to become a Competent Leader (see Appendix 3). A new member usually starts taking easier jobs such as “Ah counter,” “timer,” and so forth to more important jobs such as evaluators and Toastmaster of the Evening (TME). After completing Competent Leader, Advanced Leader comprises two levels: Advanced Leader Bronze (ALB) and Advanced Leader Silver (ALS). To be an ALB, one is required to spend at least 6-month as a club officer such as president, vice president, and so forth. To move on to an ALS, one must take a job as a district officer such as district governor, public relation officer, and so forth. Finally, after achieving Advanced Communicator Gold award and Advanced Leader Silver award, one becomes a distinguished Toastmaster (DTM).

Background of the Study

As mentioned that TM clubs serve the purposes of training people’s public speaking ability and developing leadership, in Taiwan, the clubs have a growing number in its branches. Taiwanese people can gain extra opportunities to practice speaking English in the club, especially to train presentation skills and public speaking ability. TM clubs have two primary goals of speaking practices and

leadership development, and both appeal to a wide variety of people in different fields with various learning objectives.

According to Warriner (2010), “adult language learners might access

membership by taking on certain practices, acquire the knowledge and skills valued by insiders, and demonstrate competence by enacting particular ways of being, thinking, believing, acting, and talking” (p. 22). Moreover, the importance of

community building and the sense of belonging to a community have positive impacts on adult ESL learning (Larrotta, 2009). Therefore, a learning community is believed to serve as a facilitative way to enhance one’s language proficiency.

In addition, “lifelong learning” is an ideal goal for people to gain knowledge and practices to meet the needs at work and in society (Koper et al., 2005). Lifelong learning commonly takes place in a form of a learning community in which the atmosphere is learner-centered and every participant can take the role as a teacher to facilitate each other’s learning process (Koper et al., 2005). Members with similar goals in the community are autonomous and willing to share knowledge with each other (Koper et al., 2005).

Purpose of the Study

The importance of building up learning communities has been highlighted to investigate the effects on language acquisition in a curriculum-based situation

(Shapiro and Levine, 1999; Levine and Shapiro, 2000). However, most research paid attention to in class learning, and little research has focused on English learning

communities outside a classroom setting. In addition, some research (Chou, 2003; Sun, 2007; Kuo, 2010) has integrated the “Toastmasters Approach” to language classrooms to investigate the learning effects. They adopted the pattern of regular meetings in TM clubs in the classroom to train students’ English speaking ability. The studies showed beneficial results of applying the “Toastmasters Approach” into classroom learning, and the students appreciated the extraordinary learning experiences compared with learning in traditional teacher-centered classrooms. Thus, the “Toastmasters Approach” has been upheld to be practically applicable to any language learning.

However, few studies have specifically focused on understanding the TM club itself in Taiwan. The purpose of the present study is to explore the effectiveness of the TM clubs, specifically with regard to English learning on a voluntary basis. The participants’ motivation to attend the TM club, their self-perceived learning outcomes, and their overall perception of the TM club are the three main focuses to be

investigated in the present study. The major research questions are addressed as follows:

1. What is the participant’s motivation for attending the Toastmasters club? 2. What is the participant’s self-perceived improvement after attending the

Toastmasters club?

3. What is the participant’s overall perception of the value of Toastmasters club?

Significance of the Study

Ideally, it is hoped that, with the exploration of TM members, this study can help deepen the understanding of the TM club learning community and find better ways to

enhance the effectiveness of language learning, even to sustain a life long learning process. Lifelong learning requires building up an amicable learning environment which can help constituents of that community develop corporative learning skills, useful strategies, and a variety of learning methods (Chang, 2010). Moreover, this study may be able to provide further pedagogical implications and uncover beneficial methodology to facilitate language teaching and learning in the EFL context. Related literature is reviewed in the next chapter.

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

In this chapter, literature related to the present study is reviewed, and is categorized into four themes: situated learning, learning community, autonomous learning, and public speaking. First, situated learning is illustrated, and the application of situated learning is described. Second, psychological sense of community is

introduced to be related to learning community, and the definition of learning community is provided. Also, advantages and disadvantages of learning community are discussed. Third, the definition of autonomous learning as well as components of autonomy are given and discussed. Moreover, two main components of autonomy – motivation and self-confidence are described specifically in that they play influential roles in this study. Finally, public speaking is introduced because it is the primary goal in TM clubs. Thus, public speaking needs, factors affecting public speaking, and components of public speaking are illustrated.

Situated Learning

What is Situated Learning?

It has been argued that learning does not happen spontaneously because

“knowledge is situated” (Brown, Collins, and Duguld, 1989). Learning is a process in which “activity,” “concept,” and “culture” are interwoven triangularly, and situated cognition is critically summoned in the learning process (Brown, Collins, and Duguld, 1989). Situated cognition refers to one’s cognition which can be situative in different environments, and the environments include social, cultural, and physical contexts in which people are learning (Brown, Collins, and Duguld, 1989). Lave and Wenger (1991) first proposed that situated learning happens in a specific context, and this type

of learning should be regarded as a social process instead of individual work. That is, situated learning strengthens a community of practice so that people involved in the context can interact and cooperate with others to co-construct “meanings” or

“knowledge” (Lave and Wenger, 1991). Thus, situated learning is a “peer-based” approach rather than the involvement of a “teacher-student relationship” (Lunce, 2006). Also, situated learning can be of assistance in meeting a goal in the “real world” (Henning, 1998; Lunce, 2006) because the goal can be hidden in creating a situated activity.

The Application of Situated Learning

Situated learning can function as a form of learning strategy (Lave and Wenger, 1991), so, situated activities have been integrated into pedagogy. Situated learning comprises two ideas: cooperation and cognitive apprenticeship (Brown, Collins, and Duguld, 1989). They are widespread in situated activities. People co-construct their learning to fulfill certain objectives in the activities which can then be applied to a broader goal beyond the activity (Lunce, 2006). On the other hand, cognitive apprenticeship is the theory that an expert imparts knowledge or skills to novice learners (Hennessy, 1993). Moreover, the expert consciously supports and helps the novice learners in the process of observation and practice (Hennessy, 1993). When situated learning is applied to activities, they can be in the form of workshops, role plays, job training, field trips, sports or music practice, or any kind of practice (Lunce, 2006). However, the application of situated learning is not without limitations. For example, the process of its development is time-consuming, full active involvement is difficult to reach, and the efficiency is inadequate (Lunce, 2006).

As stated, situated learning involves cooperation and cognitive apprenticeship, the creation of communities of practice is a suggested way to arouse situated learning (Wenger, 1998). In the next section, the theme of learning community is covered.

Learning Community

Psychological Sense of Community

In recent research, community has been more related to the issues of learners’ identity and affection (Fendler, 2006). In order to explore in depth what a community can bring to enhance learning, the psychological sense of community (PSOC) needs to be covered for the present study. Sarason (1947) provided a definition of PSOC, which is "interdependent with others, a willingness to maintain this interdependence by giving to or doing for others what one expects from them, the feeling that one is part of a larger dependable and stable structure" (p. 157). Yasuda (2009) explained the definition of PSOC that the word “community” has been replaced by interdependence and dependable and stable structure to represent the characteristics of PSOC. Also, PSOC can be applied geographically and functionally, so, neighborhoods, schools,

and workplaces are all possible candidates for PSOC contexts (Yasuda, 2009). Membership, influence, integration and fulfillment of needs, and shared

emotional connection are the factors intertwined in PSOC (McMillan and Chavis, 1986). That is, PSOC refers to "a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members' needs will be met though their commitment to be together" (McMillan and Chavis, 1986, p. 9).

Definition of Learning Community

The concept of learning community was first introduced for the purpose of curriculum in Meiklejohn’s Experimental College at the University of Wisconsin, Madison (Meiklejohn, 1932; Nelson, 2001). Students meet their academic needs in a classroom where they devote engagement and involvement with each other to create a learning community (Tinto, 1997). In the 1980s, it has been stated that learning community strengthens student engagement in and out of the classroom (Zhao and Kuh, 2004). Moreover, the statement has been approved that students’ participation in a learning community correlates positively with their educational performance (Zhao and Kuh’s, 2004).

Astin (1985) provided a broader definition that “such communities can be organized along curricular lines, common career interests, vocational interests,

residential living areas, and so on. These can be used to build a sense of group identity, cohesiveness, and uniqueness; to encourage continuity and the integration of diverse curricular and co-curricular experiences; and to counteract the isolation that many students feel” (p. 161). Later on, Shapiro and Levine (1999) defined learning community as a concept that students are capable of interacting with not only the classroom material but also their peers and faculty members within the curricular system.

The “student-type learning community” is especially designed to help

“academically underprepared students, historically underrepresented students, honors students, students with disabilities, or students with similar academic interests” (Zhao and Kuh’s, 2004, p.116). Smith (2010) stresses one of the main purposes of learning communities proposed by Shapiro and Levine (1999) as providing students with the opportunity to make connections between the content they learn and people they make contact with in the classroom setting. To fulfill the purpose, relevant faculty members

in the learning community applied methods (e.g., team-teaching, collaborative

learning strategies, problem-based learning, and service learning) to help the learning environment to be cohesive for the students so that a learning community is ideally formed (Smith, 2010). In addition, social and collaborative activities are prevalent in class in order to increase interaction and cooperation (Zhao and Kuh, 2004).

Advantages and Disadvantages of Learning Community

In the formation of a learning community, a positive, encouraging learning environment has to be guaranteed (Zhao and Kuh, 2004; Engstrom, 2008; Smith, 2010). Faculty members can help to build an advantageous learning community from four perspectives: “active learning pedagogies”, “faculty collaboration and an

integrative curriculum”, “development of learning strategies”, and “faculty validation” (Engstrom, 2008, p. 9). These can be explained further: first, dynamic ways of learning, instead of a teacher-centered traditional method, assist learners in building trust to assure desirable participation in the process of learning. Second, relevant member collaboration is helpful in designing learning content so that time can be saved and learners’ previous experiences can be recalled to integrate with the new-learnt information (Cross, 1998). Third, learning strategies can include forming study groups, accessing tutoring services, and seeking out academic support offices. Fourth, faculty validation fortifies the learners’ sense of belonging to the community and acknowledges each other’s contribution in the community; therefore, the learning ability is enhanced.

Competitive advantages which are easily found in a learning community result in the development of the members’ capabilities (Liedtka, 2000). Cross (1998) asserted that a learning community can serve the functions of “training people effectively for the workplace” and “educating them for good citizenship” (p. 10). Moreover,

“leadership” can be built and developed among the community members (Fendler, 2006), which is also one of the major goals in TM clubs (Toastmasters International, 2010).

Although learning communities have been advocated for many years (Zhao and Kuh, 2004; Larrotta, 2006; Engstrom, 2008; Smith, 2010), they may still be

unfavorable because of the effects of “assimilation” and “homogeneity” (Fendler, 2006). That is, learning communities may exclude individual differences, and this can be problematic in that expectations toward learning outcomes can be extremely different from person to person.

Much research (Zhao and Kuh, 2004; Larrotta, 2006; Engstrom, 2008; Smith, 2010) related to learning community is limited in the classroom setting with the concern about students’ academic activities and performances. Thus, learning

community is generally defined as an enhancement of the curriculum. However, few studies had specifically focused on any “out-of-class” learning communities. With the possibility that “out-of-class” learning communities can be as helpful as in-class learning communities to facilitate the process of learning, it would thus be of interest to learn how the TM club can act as one of “out-of-class” learning communities. TM clubs are in a similar way to any curriculum-based learning communities because of the common purposes of giving the participants a supportive environment and enhancing their learning outcome. In order to gain more insights about people to join the TM club on a volunteer basis, next, autonomous learning is introduced.

Autonomous Learning

Definition of Autonomous Learning

According to Feist (1999), “in many ways autonomy is a trait that clusters around other special dispositions: introversion, internal locus of control, intrinsic

motivation, self-confidence/arrogance … These traits are social because they each concern one’s consistent and unique patterns of interacting with others” (p. 160). If a learner possesses the trait of autonomy, generally, the learner can make connections between what to learn and what role to play in the learning process (Little, 1994). To be more specific to second/foreign language learning, autonomous learners can be near-fully conscious about the language they are learning, and to integrate the language to life (Little, 1994). That is, autonomous language learners are easier to become good L2 communicators who have higher level of independence, self-reliance, and self-confidence to be capable of understanding social, psychological, and

discourse situations they encounter (Little, 1994).

Five characteristics of autonomous learners are described as follows (Dickinson, 1993). First, autonomous learners can understand the importance of the curriculum objectives and what has been taught. Second, autonomous learners can collaborate with the teacher to achieve the learning objectives they set up for themselves. Third, autonomous learners can apply useful strategies in the process of learning. Fourth, autonomous learners can actively monitor their learning process and be aware of their learning situation. Last, autonomous learners can feel confident in solving problems they encounter in learning. Therefore, autonomous learners are easier to be good at critical reflection and decision making (Dickinson, 1995). To have an in-depth understanding of autonomous learning, components of autonomy are explored as follows.

Components of Autonomy

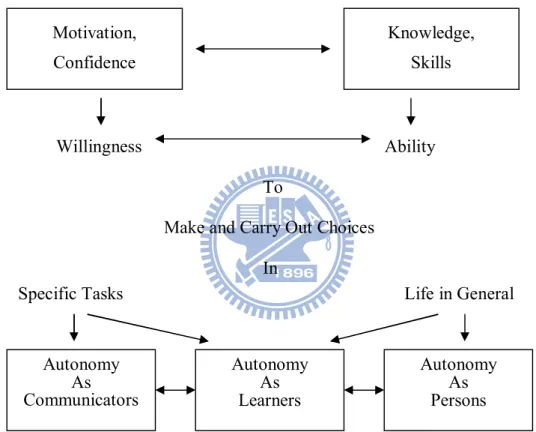

Littlewood (1996) proposed that ability and willingness are two main

components of autonomy. Ability refers to one’s knowledge of doing a specific task and skills to accomplish the task. On the other hand, willingness requires one’s

motivation and confidence to take responsibility to do the task. He stated that all these four sub-components are closely linked to each other (see Figure 2). For instance, “the more knowledge and skills the students possess, the more confident they are likely to feel when asked to perform independently; the more confident they feel, the more they are likely to be able to mobilize their knowledge and skills in order to perform effectively” (p.428).

Willingness Ability To

Make and Carry Out Choices In

Figure 2 Littlewood’s (1996) Model of Components and Domains of Autonomy in Foreign Language Learning

Littlewood (1996) further depicted a framework of the relation between learner autonomy development and foreign language learning (see Figure 3). Autonomy can be obtained by the target language learners in playing three different roles:

communicators, learners, and persons. The three roles all require motivation, knowledge, confidence, and skills. As the role of communicators, autonomous ones

Motivation, Confidence Knowledge, Skills Life in General Specific Tasks Autonomy As Communicators Autonomy As Learners Autonomy As Persons

can integrate their language ability with communication strategies and linguistic creativity. Since linguistic creativity influences how one expresses thoughts in the target language, so it forms autonomy as a person. On the other hand, as the role of learners, autonomous ones can adopt learning strategies and complete work

individually. That is, autonomous learners can do independent work, and they know how to create a suitable learning context for themselves. Personal learning contexts can be a group formed by native speakers of the target language, books or newspapers written in the target language, and so forth. Therefore, the role of autonomous persons can create personal language learning environments, and express in the target

language clearly in communicating with others.

Figure 3 Littlewood’s (1996) Framework for Developing Autonomy In and Through Foreign Language Learning

Autonomy as a Communicator Autonomy as a Learner Autonomy as a Person Motivation Confidence Knowledge Skills Communication Strategies Learning Strategies Linguistic Creativity Independent Work Creation of Personal Learning Contexts Expression of Personal Meanings

Motivation in Learning Autonomy

Links have been found between autonomy and motivation with regard to the efficacy of learning (Dickinson, 1995). In the previous literature (Dickinson, 1995), both autonomy and motivation connect the three key concepts: learner independence, learner responsibility, and learner choice.

In terms of the two different types of motivation: extrinsic and intrinsic motivation (Ryan and Deci, 1985), learner autonomy positively correlates one’s intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation refers to “do something because it is

inherently interesting or enjoyable” (Ryan and Deci, 2000, p. 55). On the other hand, extrinsic motivation “refers to doing something because it leads to a separable outcome” (Ryan and Deci, 2000, p. 55).

More specifically, intrinsic motivation (IM) is related to three aspects: knowledge, accomplishment, and stimulation. IM-knowledge is the motivation of doing something for obtaining knowledge or information from it; IM-accomplishment is the motivation of doing something for sensing satisfactory after completing it; IM-stimulation is the motivation of doing something for feeling excited or being appreciated (Noel, Pelletier, Clement, and Vallerand, 2000). Extrinsic motivation (EM) is related to external regulation, introjected regulation, and identified regulation

(Vallerand, 1997). External regulation refers to the motivation of doing a certain task for external sources, e.g. awards or any kinds of benefits; introjected regulation relates to “self-concept” so that one does certain things because of the feeling to confirm self-value or not to be disdained; identified regulation refers to the motivation of doing a certain task that is considered important and valuable.

In addition, four ‘orientations’ for second language learning are proposed to be crucial to learners’ motivation (Kruidenier and Cle´ment, 1986). The four orientations include instrument, knowledge, travel, and friendship (Kruidenier and Cle´ment,

1986). Instrument represents exterior sources such as certificates or diplomas; knowledge represents interior sources such as ideas or information. Travel refers to opportunities to go overseas for any reasons; friendship refers to human relations, e.g. to make more friends (Kruidenier and Cle´ment, 1986). According to Noel, Pelletier, Clement, and Vallerand’s study (2000), friendship, travel, and knowledge orientations are found to be related to intrinsic motivation and identified regulation; instrumental orientation is found to be related to external regulation. Thus, the four orientations can imply both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (see Table 4).

Table 4

The Relationship between Motivation and the Orientations

Knowledge Travel Instrument Friendship Knowledge Accomplishment IM Simulation ˇ ˇ ˇ External regulation ˇ Introjected regulation EM Identified regulation ˇ ˇ ˇ

IM = Intrinsic Motivation; EM = Extrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation generates self-determination and also initiates autonomous learning (Dickinson, 1995), thus, it is highly encouraged in the language learning process (Scharle, 2001). Moreover, learners’ intrinsic motivation is intertwined with the willingness to take the required responsibilities of language acquisition; and one reinforces the other (Scharle, 2001). That is, a learner who possesses high intrinsic motivation understands the goals of learning in greater depth; therefore he or she will be more willing to take the required responsibility. As a result, the intrinsically motivated learner becomes more independent towards learning (Scharle, 2001).

As mentioned earlier, self-confidence is one of the key components of autonomy so that it plays a vital role in autonomous learning (Littlewood, 1996; Scharle, 2001). In particular, it can be more successfully to lead to well manipulation of responsibility to accomplish the goal of learning. Therefore, one who possesses high level of

self-confidence is more willing to take actions spontaneously, so self-confidence and action taken can be the essential factors that contribute to self-efficacy (Brown, 2007).

Finally, as public speaking is the main goal in the TM clubs, needs for public speaking, factors which affect public speaking, and components of public speaking are discussed in the next section.

Public Speaking

Public Speaking Needs in Class and in Workplace

Public speaking is a form of oral communication, and it has been viewed as an important ability for people in life academically and occupationally. According to the Ministry of Education (MOE), all the English majors in Taiwan have to take English speech courses to practice public speaking skills for at least two semesters (Katchen, 1989). Moreover, oral communication has recently become a necessity for not only English majors but also students from other disciplines (Darling and Dannels, 2003).

Oral performance now acts as a useful tool to represent one’s profession (Darling and Dannels, 2003). In class, students are always asked to make oral presentations and give oral reports of class content and assignments. In addition, many instructors prefer to let students have debate sessions on certain topics to train their public speaking and critical thinking ability (Smith, 1986). Therefore, learners’ public speaking skill is trainable (Fawcett and Miller, 1975), and there are a lot of courses designed specifically to train students’ public speaking and presentation skills. As for

employees’ public speaking ability. The reasons are that employees in different job fields have many opportunities to go for business trips, encounter foreign customers, give English presentations of job reports, project proposals, or product benefits (Gergory, 1996). In order to perform better in workplace, employees would like to seek further education on language courses to improve their English speaking skills.

Factors Affecting Public Speaking

Many factors can affect public speaking, and culture is one of the factors (Jaffe, 2004). Taiwan, an EFL setting is unlike ESL context in which English learners can directly contact with native speaking culture. In fact, many EFL learners understand the importance of good English speaking ability; however, how to succeed can be a difficult task (Liu, 2005). Most of the Taiwanese students feel uneasy to communicate with others in English in a language class, and this situation relates to the indirect exposure of English speaking culture and the traditional value in Chinese culture (Liu, 2005). That is, compared with students in western countries, Chinese students prefer to be listeners instead of being speakers who are easily to be regarded as an authority in a communication.

Culture can affect public speaking in many ways because it can give different definitions to public speaking (Jaffe, 2004). For example, culture can be divided into expressive and non-expressive cultures (Jaffe, 2004). In expressive cultures,

“members are encouraged to give their opinions, speak their minds, and let their feelings show” (Jaffe, 2004, p. 11). On the other hand, members in non-expressive cultures “value privacy and encourage people to keep their emotions and ideas to themselves rather than to express them publicly” (Jaffe, 2004, p. 12). Therefore, the differentiation between expressive and non-expressive culture may influence one’s public speaking ability.

There are still other factors which can affect EFL learners’ speaking ability. Age, English listening ability, socio-cultural factors, and affective factors all play important roles to an EFL learner’s speaking ability (Shumin, 2008). Learners’ affective domain has been a very crucial factor to influence foreign language learning in that the

learning process is essentially related to the learner’s emotion, self-esteem, empathy, anxiety, attitude, and motivation (Brown, 2007; Shumin, 2008). In speaking,

especially, communication apprehension and anxiety may be easily provoked to affect the accuracy and fluency in a talk (Jaffe, 2004; Shumin, 2008).

Components of Public Speaking

In public speaking, it is the speaker’s responsibility to know “who’s the audience,” “what’s the topic,” and “what’s the medium of the speech” (Zarefsky, 2002). Also, communication competence represents one’s language proficiency which is rooted in public speaking (Shumin, 2008). According to Canale and Swain (1980), communication competence comprises sociolinguistic competence, grammatical competence, discourse competence, and strategic competence. Shumin (2008)

proposed components of effective speaking using Canale and Swain’s components of communication competence (see Figure 4). That is, in speaking, grammatical

competence refers to knowledge of vocabulary, morphology and syntax, as well as pronunciation of words, intonation, and stress. Discourse competence refers to the speaker’s management of cohesion and coherence of a speech. Sociolinguistic competence refers to “appropriateness” of the language use so that the speaker has to understand the “norm” socially and culturally. Strategic competence refers to both verbal and nonverbal actions that serve as tools in delivering a speech (Shumin, 2008).

Figure 4 Shumin’s (2008) Components Underlying Speaking Effectiveness

Based on the literature reviewed, the present study aims to investigate the components of learning autonomy in TM within a situated context to explore the learning community of TM clubs. The TM club members’ motivation

(knowledge-oriented, instrument-oriented, travel/business-oriented, and

friendship-oriented motivation), knowledge, skills (self-perceived improvements), and self-confidence were analyzed to help understand how these components of learning autonomy are related to the process of learning. Also, the members’ perceptions were probed in all aspects. In the next chapter, the method of the present study is described in detail. Speaking Proficiency Sociolinguistic Competence Grammatical Competence Discourse Competence Strategic Competence

CHAPTER THREE

METHOD

The main purpose of the present study is to explore reasons for people to attend the learning community of Toastmasters Club in Taiwan. In particular, this study aims to understand the club members’ learning effects after attending the TM club. Thus, the participant’s motivation of joining the TM club, the self-perceived improvements, and overall perception of the value of TM club were probed. The research method was a mixed-approach to collect both quantitative and qualitative data, adopting a questionnaire with close-ended and open-ended questions and conducting interview sessions. It is hoped that this present study could provide an encompassing

understanding of TM clubs in Taiwan. This chapter introduces the participants, the instruments, the research procedures, and data analysis.

Participants

As mentioned, there are two types of TM clubs in Taiwan: regional clubs and campus clubs. This study chose one unit from each type of TM clubs in Taiwan. Table 5 shows the demographic information of the participants in the present study.

Thirty-four participants were from a regional TM club in which participants come from a city in Northern Taiwan. The number of regular attenders in every meeting is about 40. One specialty of the TM club is that many members work in a science park as any kinds of engineers in the local city, and there are also college students, graduate students, teachers, a few foreigners. So, this TM club is more similar to a small society with people studying and working in various fields.

Twenty-two participants were from a campus club which is a student-oriented organization in a university in Northern Taiwan, and the majority of the members are

university students, both undergraduates and graduate students, studying in different departments. In each meeting, there are nearly 30 participants, including more than 20 official members.

Table 5

Demographic Information of Participants

N Type of TM Regional 34 Campus 22 Occupation Student 26 Employee 29 Gender Male 32 Female 24

Role Club officer 24

Non club officer 29

Age Below 20 7

20 to 30 33

Above 30 12

Less than 1 year 29

Duration of

membership 1 to 2 years 5

2 to 3 years 4

More than 3 years 4

Data Collection

A mixed-method (quantitative and qualitative) design was implemented in the present study. Quantitative data were elicited from the questionnaire, and it was distributed to all the participants of the two TM clubs. The questionnaire items were designed by the researcher based on relevant literature. Qualitative data were from the participant’s response to the six open-ended questions in the questionnaire and a semi-structured interview. After the questionnaire was completed, the participant was asked if they are willing to participate in the interview. Six participants chosen from

the volunteers in each TM club will participate in the interview session. The interview questions were designed to answer the research questions to validate the quantitative data in the present study. The researcher of the present study was also an observer of both TM clubs to participate in the TM meetings and take field notes or record incidents happening in the club. The reason for this mixed-method design is that both general and more detailed information can be collected and analyzed in order to provide more generalized and adequate results and discussions.

Instrumentation

The Questionnaire

The questionnaire was divided into five sections, including (1) demographic information, (2) motivation, attitude, self-perceived improvements of attending the TM club, (3) self-perception of enjoyment and helpfulness of the TM club, and (4) open-ended questions (see Appendix 4 & 5).

Section (1) was demographic information which requires the participant to fill out background information such as age, gender, career, college major, English proficiency level and certificate, duration of TM membership, and current speech level in the TM club.

Section (2) contained the questionnaire items of motivation, attitude, and self-perceived improvements of attending the TM club based on a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = totally agree). There were eight items (1 to 8) used to investigate the participant’s motivation of attending the TM club to answer Research Question 1 “What is the participant’s motivation for attending the Toastmasters club?”

The questionnaire items (1 to 8) of motivation were based on Kruidenier and Cle´ment’s (1986) four orientations in order to focus more comprehensively on

socio-affective factors. Items 1 and 2 were used to understand the knowledge scale; Items 3 and 4 were used to understand the travel scale; Items 5 and 6 were used to understand the instrument scale; Items 7 and 8 were used to understand the friendship scale.

Items 19 to 33 in Section (1) were created to answer Research Question 2 “What is the participant’s self-perceived improvement after attending the Toastmasters club?” It included 15 items to understand the participant’s self-perceived

improvements on English learning and other aspects. The participant completed this section based on the learning outcome or self-perceived progress. The majority of the items (19 to 26) specifically focused on different aspects in English learning such as four language skills, vocabulary capacity, pronunciation, and grammar. The other items (27 to 33) were designed to evaluate participant’s other improvements which cater to the missions in the TM club. Therefore, the participant needed to examine whether his or her communication skill, presentation skill, public speaking ability, confidence in using English and leadership abilities have been cultivated.

The items (9 to 18) in Section (2) and all items in Section (3) aimed to understand the participant’s perception of attending the TM club. One’s perceived self-confidence, level of autonomous learning, sense of belonging to TM, perceived learning benefits, enjoyment, and helpfulness were the major themes in knowing the participant’s overall perception of attending the TM club. The ten items (9 to 18) in Section (2) were used to understand participants’ perceived self-efficacy. Items 9 and 10 were created for knowing the participant’s confidence; Items 11 to 13 were created for knowing the participant’s perceived level of autonomous learning. Items 14 and 15 were used to understand the member’s sense of belonging to the TM club. Items 16 to 18 were asked to investigate whether the member has gained learning benefits from the club.

Section (3) was also a five-point Likert scale of perceived enjoyment and perceived helpfulness towards different meeting sessions and different meeting roles in the TM club. This section contained two separated parts. The top half of the section was to ask the participant’s point of view as an audience in participating in different meeting sessions in the TM club. The bottom half was to ask the participant’s perceived enjoyment and perceived helpfulness in playing different meeting roles in the TM club. This section can help elicit information to answer the Research Question 3 “What is the participant’s overall perception of the value of the Toastmasters club?”

Finally, the participant was asked to complete six open-ended questions in Section (4). The questions were:

1. What is the most attractive reason for people to attend the Toastmasters club? 2. What is the motivation for you to attend the Toastmasters club?

3. As an audience, what session in the Toastmasters club do you think is the most useful towards English learning?

4. What roles in the Toastmasters club do you think is the most useful towards English learning?

5. What’s your most salient improvement (both on English learning and personal development) after attending the Toastmasters club?

6. Write down suggestions or comments for the Toastmasters club if you have.

In fact, most of the open-ended questions were repeated as in the questionnaire items. However, open-ended questions can elicit specific answers more

comprehensively so that the researcher can gain more insights in answering the research questions and to make the results and discussions more detailed.

The Interview

Three members from each TM club participated in the interview, and their demographic information is shown in Table 6. The six interviewees were chosen from volunteers based on the duration of their TM membership. They were two who have participated in TM for less than a year, two for one to two years, and two for more than two years respectively and all signed consent forms (see Appendix 8). Each interview session lasted about forty minutes and was conducted face-to-face

individually in the native language of Chinese. Moreover, all of the interview sessions were audio recorded for transcription and future analysis. The interview was

semi-structured because the researcher used a guide of eighteen questions (see Appendix 6 & 7), and the interviewees had freedom to state opinions on their

experience with the TM club. The themes entailed in the interview questions are listed in Table 7.

Table 6

Background Information of the Interviewees *Code Age Gender Occupation Club

officer Current speech Duration of membership Date of the interview

R1 32 F Employee No C3 9 months April 28th, 2011

R2 33 M Employee Yes C3 2 years April 27th, 2011

R3 23 M Student Yes A10 5 years and

9 months

April 26th, 2011

C1 20 M Student Yes C5 1 year and

2 months

April 29th, 2011

C2 21 F Student Yes C6 2 years April 29th, 2011

C3 19 F Student Yes A12 4 years April 29th, 2011

Table 7

Themes for Interview Questions Interview Question Theme

1 knowledge-oriented, travel/business-oriented, instrument-orientated, and friendship-oriented motivation

6 – 8, 12 – 13 self-perceived improvements in English ability, speaking

proficiency, public speaking, communication, confidence in using English, and leadership development

2 – 5, 9 – 11, 14 - 20 situated learning, learning community, autonomous learning, sense of belonging, perceived learning benefits, and other perceptions

Data Analysis

Both quantitative data and qualitative data contributed to the present study. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was applied to deal with data in the questionnaire. On the other hand, qualitative data from open-ended questions and interview sessions were analyzed by content analysis. More specifically, the distributed relation between the research questions and the research instruments is shown in Table 8.

Table 8

The Distributed Relation of Research Questions and Research Instruments

Research Question Questionnaire Section Interview Question

1. Motivation (2) 1 – 8 1 (4) 1 – 2 2. Self-perceived improvement (2) 19 – 33 6 – 8 (4) 5 12 – 13 3. Overall perception (2) 9 – 18 2 – 5 (3) All 9 – 11 (4) 3 – 4, 6 14 - 20

Quantitative Data Analysis

The numerical data from Section (2) and (3) in the questionnaire were

transformed to statistical data and were later analyzed by the SPSS. The descriptive statistics of the totals, percentages, means and standard deviations of each

questionnaire items in different sections were applied and interpreted to answer the research questions. In addition, there were some variables (type of TM, occupation, gender, role, age, and TM membership duration) that were influential in this study. To have more specific analyses, MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis Of Variance) was used to see if there were any significant differences among the variables or whether the two types of TM clubs were significantly different from one another for the researcher to explore.

Qualitative Data Analysis

The six open-ended questions in the questionnaire plus twenty interview

questions provided qualitative data for the present study. All responses written for the open-ended questions and the transcriptions of the voice files from the interview sessions were compiled and analyzed. The method of content analysis provided the researcher more insights to interpret and validate the quantitative data to help strengthen the results to contribute more details to answer the three research questions.

CHAPTER FOUR

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

RQ1: What is the participant’s motivation for attending the Toastmasters club?

To investigate the participants’ motivation to join the Toastmasters club, eight questionnaire items were asked (see Table 9). The participants needed to complete a questionnaire on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree) to answer each questionnaire item. Also, the qualitative results from the interview session were excerpted to support the

quantitative results.

Table 9

Descriptive Statistics for Motivation

Item description M SD R

Knowledge-oriented motivation (English, public speaking) 4.44 0.61 1 I join the TM club because I want to learn English. 4.47 0.63 I join the TM club because I want to learn English public speaking. 4.41 0.70 Travel/Business-oriented motivation (Travel/Business English) 3.96 0.85 3

I join the TM club because it may be beneficial for me if I have opportunities to travel overseas for pleasure.

4.02 0.89 I join the TM club because it may be beneficial for me if I have

opportunities to go overseas for business trips.

3.90 0.93 Instrument-oriented motivation (better education, job, salary) 3.96 0.77 3

I join the TM club because it can help me perform better at work. 4.02 0.86 I join the TM club because I can pursue a higher level of diploma, a

better job or get higher salary.

3.90 0.93 Friendship-oriented motivation (interpersonal relationship) 3.99 0.67 2

I join the TM club because it can help me make acquaintances with more foreigners.

3.71 0.88 I join the TM club because it can help me make more friends. 4.26 0.79 R=Ranking

As shown in Table 9, each type of motivation received group means near or greater than 4.0 on the five-point Likert scale. Knowledge-oriented motivation ranked first (M = 4.44, SD = 0.61) in the participants’ responses. Friendship-oriented

motivation received the second highest group score (M = 3.99, SD = 0.67);

travel/business-oriented (M = 3.96, SD = 0.85) and instrument-oriented (M = 3.96, SD = 0.77) motivation both ranked third.

Knowledge-oriented motivation

As presented in Table 10, among all variables (type of TM, occupation, gender, role, age, and TM membership duration), knowledge-oriented motivation ranked first of the four types of motivation, and the mean scores received higher than 4.31 on the five-point Likert scale. The results indicate that knowledge-oriented motivation plays a primary role for members when deciding to join Toastmasters clubs.

I love English, and I want to practice English speaking. TM clubs provide the environment for people to speak English. (R3)

I think I have two motivators. One is to practice English ability such as listening, speaking, reading, and writing. The other is to train English public speaking because I believe practicing public speaking can enhance my English communication ability. Although I don’t need to deliver speeches when working, I need to speak a lot of English to communicate with oversea colleagues. (R2)

When I was a senior student, I participated in the Asian Science Camp. Everyone needed to speak English to talk to each other there, but I found my English ability was insufficient. Also, I didn’t want my English to go down hill after I entered college. So, I joined the Toastmasters club when I was a freshman. (C3)

Table 10

Descriptive Statistics for Motivation for Various TM Related Variables Knowledge -oriented Travel/Business -oriented Instrument -oriented Friendship -oriented Variable N M SD R M SD R M SD R M SD R Type of TM Regional 34 4.34 0.65 1 4.04 0.74 3 4.02 0.80 4 4.10 0.67 2 Campus 22 4.64 0.49 1 3.86 1.03 3 3.89 0.74 2 3.82 0.67 4 Occupation Student 26 4.48 0.61 1 3.82 0.95 3 3.98 0.78 2 3.82 0.65 3 Employee 29 4.37 0.64 1 4.18 0.71 3 3.95 0.80 4 4.26 0.70 2 Gender Male 32 4.56 0.55 1 4.22 0.73 2 3.94 0.75 4 4.09 0.64 3 Female 24 4.31 0.66 1 3.65 0.93 4 4.00 0.82 2 3.85 0.71 3 Role Club officer 24 4.58 0.55 1 3.98 0.88 4 4.00 0.77 2 4.00 0.61 2 Non club officer 29 4.48 0.53 1 4.00 0.90 3 3.90 0.76 4 4.05 0.72 2 Age < 20 7 4.14 0.90 1 3.86 0.63 3 4.07 0.93 2 3.36 0.48 4 20 to 30 33 4.61 0.48 1 4.00 0.95 3 3.97 0.76 4 4.08 0.70 2 > 30 12 4.33 0.72 1 3.96 0.92 3 3.88 0.80 4 4.08 0.67 2 Membership duration < 1 yr 29 4.52 0.49 1 3.81 0.96 4 3.90 0.72 2 3.90 0.69 2 1 to 2 yrs 5 4.30 0.84 2 4.10 0.74 3 3.50 0.87 4 4.40 0.42 1 2 to 3 yrs 4 4.63 0.48 1 3.63 1.11 4 4.13 1.03 2 4.00 0.41 3 > 3 yrs 4 4.75 0.50 1 4.75 0.50 1 4.50 0.58 2 4.25 0.87 4 R=Ranking

The participants reported a greater need to improve English, especially on speaking and listening skills. Also, the development of better public speaking ability including presentation and communication skills is the participants’ major motivation to join TM. In sum, the members’ desire to learn English along with their

commitment to develop their public speaking skills is what brings everyone together in TM.

Friendship-oriented motivation

As for friendship-oriented motivation, it ranked second amongst the variables. The regional TM members and members who are employees valued

friendship-oriented motivation as the second most important form of motivation (M = 4.10, SD = 0.67 for the regional TM member, M = 4.26, SD = 0.70 for the employee members), following knowledge-oriented motivation. The results show that, in addition to learning English and public speaking, the development of interpersonal relationships plays a significant role as well.

In fact, the reason for me to join TM was that I was a college freshman at that time and I just wanted to join a campus club. I wanted to make friends because I didn’t participate in any campus clubs when studying in the senior high school. (R3)

I wanted to make more friends. In TM, people don’t treat new members as outsiders; instead, everyone is passionate to welcome each other. That’s why I joined TM. (C2)

Moreover, as the results of the MANOVA shown in Table 11, the emphasis of friendship-oriented motivation for the employee participants (M = 4.26, SD = 0.70) was found significantly higher than that for the student participants (M = 3.82, SD = 0.65) in TM (p < 0.05). More employees reported that making friends is an influential reason for them to join TM whereas the campus TM members who were students and those under 20 years old ranked friendship-oriented motivation as the least important (M = 3.82, SD = 0.67). These results confirm that for student members and those who