The

International

Journal of Tuberculosis

and Lung Disease

PROOF READING INSTRUCTIONS FOR AUTHORS

E

NCLOSED ARE PAGE PROOFSof your article which is to appear in The

International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease.

Please check the proofs word by word and line by line, making only essential

corrections. Do not add new material, split existing paragraphs or alter

punctuation, as corrections at this stage are expensive. If there are extensive

corrections authors may be asked to contribute towards the cost; corrections are

inserted at the discretion of the editor.

Use the proof-reader’s marks attached as your guide for making additions and

corrections. Write corrections in the margin, with corresponding marks in the

text. When marking the page proof, note (PE) for printer’s error, (EA) for

editor’s error or (AA) for author’s alteration.

Please correct the paper promptly and return it within 72 hours by fax to:

The Editorial Office, 68 boulevard Saint Michel, 75006 Paris - FRANCE.

Fax: (+ 33 1) 53 10 85 54

Please remember that failure to return proofs within 72 hours may delay the

publication of your article

The

International

Journal of Tuberculosis

and Lung Disease

OFFPRINT ORDER FORM

OFFPRINTS can be ordered by completing the form below. EVEN IF YOU DO NOT WISH TO ORDER OFFPRINTS,

PLEASE RETURN THIS ORDER FORM WITH YOUR PROOFS.

Number of printed pages

Number __________________________________________________________________

of copies 1-4 5-8 9-12 13-16 17-20

100 $125 $140 $195 $255 $310

200 $170 $215 $310 $395 $495

Add’l 100s $50 $80 $120 $140 $190

Postal / Freight charges are additional*

Mail/Fax to:

The Editorial Office, IJTLD, 68 boulevard Saint Michel, 75006 Paris, FRANCE. Fax: (+33 1) 43 29 90 83. Article title:__________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ First author: ______________________________________ Length of article (pages): _____________________

I wish to order _________ offprints I do not wish to purchase offprints

A purchase order will follow on invoice/is attached. (Purchase orders must indicate that postage will be paid as indicated on the invoice)

Credit Card payment Card Number _____________________________________________

American Express Carte Bleue/Visa Mastercard/Eurocard

Expirydate ________ / _________ Signature : ________________________________

Delivery address (please write clearly): Invoice address (if different):

Name: _____________________________________ Name: __________________________________

Street address: _______________________________ Postal address: ___________________________

_______________________________________________ ____________________________________________ _______________________________________________ ____________________________________________ _______________________________________________ ____________________________________________

Tel no: (+_____) ________________________________ e-mail: _____________________________________

e-mail: ________________________________________

*Please note: For all transactions other than credit card from outside France (i.e., cheques and transfers), bank charges of US$20 should be added to the total for payment in $US, and of 20€ for payments made in

PROOF CORRECTION MARKS

Instruction to printer

Text mark

Margin mark

Delete

Delete and close up

Delete and leave space

Substitute

Leave as printed

Insert new matter

Change to capitals

Change to small capitals

Change to lower case

Change to bold

Change to italics

Underline

Change to roman

Wrong font

Transpose

Move right

Move left

Begin new paragraph

No new paragraph

Insert punctuation mark

indicated

Insert hyphen

Insert single quotes

The typesetter works line by line when correcting proofs, looking down the margins. You should therefore make your corrections in the margin—not in the line of type—nearest the mistake, and level with it. If more than one mistake occurs in a line of text the margin corrections should be written from left to right in the same order as the mistakes occur in the line.

INT J TUBERC LUNG DIS 14(11):1–6 © 2010 The Union

Latent tuberculosis infection among close contacts of

multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in central Taiwan

Y-W. Huang,* G-H. Shen,† J-J. Lee,‡ W-T. Yang§

*Department of Tuberculosis, Changhua Hospital, Taiwan Department of Health, Changhua City, † Pulmonary and

Critical Care Medicine Section, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, ‡ Department of Internal Medicine,

Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital, Hualien, and Tzu Chi University, Hualien, § Department of Tuberculosis, Taichung

Hospital, Taiwan Department of Health, Taichung, Taiwan 0 7 1 8

Correspondence to Yi-Wen Huang, No 80, Sec 2, Zhongzheng Road, Puxin Town, Changhua County, Taiwan. Tel: (+61) 4 829 8686, 8960. Fax: (+61) 4 828 3275. hiwen@mail.chhw.doh.gov.tw

Article submitted 25 February 2010. Final version accepted 22 April 2010.

S E T T I N G : Both the tuberculin skin test (TST) and the

QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT) may

be used to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. A positive reaction to either test can indicate latent tuber-culosis infection (LTBI). These tests can be used to study the rate of infection in contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) patients.

O B J E C T I V E : To evaluate the transmission status of

MDR-TB patients in Taiwan by examining their close contacts and to compare the effi ciency of TST and QFT-GIT.

D E S I G N : Chest radiographs, TST and QFT-GIT were

performed in household contacts of confi rmed MDR-TB patients to determine their infection status.

R E S U LT S : A total of 78 close contacts of confi rmed

MDR-TB patients were included in the study. The ma-jority of the MDR-TB patients were parents of the close contacts and lived in the same building; 46% of the sub-jects were TST-positive and 19% were positive to QFT-GIT, indicating LTBI which was likely to develop into active MDR-TB. There was a lack of consistency be-tween TST and QFT-GIT results in subjects with previ-ous bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination.

C O N C L U S I O N : Household contacts of MDR-TB patients

are likely to develop LTBI; thus, follow-up and monitor-ing are mandatory to provide treatment and reduce the occurrence of active infection.

K E Y W O R D S : latent tuberculosis; multidrug-resistant;

QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube; tuberculin skin test

THE STOP TB PARTNERSHIP enhances interna-tional co-operation in TB control through its Global Plan to Stop TB. According to the World Health Or-ganization, the control of multidrug-resistant tuber-culosis (MDR-TB, defi ned as resistance to at least isoniazid [INH] and rifampicin [RMP]) is not as effi -cient as it had been hoped,1 and it therefore remains

a major threat.

Tuberculosis (TB) is an airborne transmitted infec-tion. Close contacts of MDR-TB patients may de-velop MDR-TB. It is thus important to identify in-fected individuals, closely monitor their infection status and provide treatment to prevent the develop-ment of drug resistance.

Latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) occurs when an individual is infected with Mycobacterium tuber-culosis,2 but does not present with active TB disease.

Such patients nevertheless possess a 10% chance of developing TB in the future.1 The possibility of

devel-oping TB is reduced when preventive measures are implemented.

Until recently, the tuberculin skin test (TST) was the only test available for the detection of M. tuber-culosis infection.2 TST can lead to false-positive

reac-tions in bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccinated populations and in those with non-tuberculous myco-bacteria (NTM) infections.2,3 The recent development

of the QuantiFERON®-TB test (Cellestis, Carnegie,

VIC, Australia) provides better screening in many in-stances. The QuantiFERON-TB test is based on the human body’s ability to produce adaptive immunity after infection with M. tuberculosis.4 The third

gen-eration of the QuantiFERON-TB test, the Quanti-FERON®-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT), uses early

secreted antigenic target 6 (ESAT-6), culture fi ltrate protein 10 (CFP-10) and TB 7.7 as antigens to stim-ulate whole-blood production of the C-mode inter-feron.5–7 As the antigen consists of the characteristic

TB strain, the host is stimulated to release cytokines, particularly interferon-gamma (IFN-γ),8–10 which can

be used for the detection of latent infection and active disease.11 TB infection is confi rmed by the production

of IFN-γ.12

According to the guidelines of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), LTBI can be defi ned as either TST or QFT-GIT posi-tivity; both detect M. tuberculosis infection and ex-isting TB infection.2,3 S U M M A R Y clarify: is ‡ one af fi liation or two?

→

2 The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the transmission status of MDR-TB patients in Taiwan by examining contacts of confi rmed MDR-TB patients using TST and QFT-GIT tests. The results of the two tests were also compared to determine their effi ciency. METHODS

Study population

All close household contacts of notifi ed MDR-TB cases at Changhua Hospital from 1 June 2005 to 30 De-cember 2007 were screened for LTBI. Seventy-eight close contacts were selected from a source of 19 in-dex cases. The study was approved by the ethics com-mittee of the Changhua Hospital and the Department of Health in Taiwan. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. Subjects were informed about the aims and procedures of the study and in-formed of the test results at the end of the study.

Demographic information including sex, age, BCG scar, residence, medical history, history of TB contact was collected from the subjects. Chest X-ray, QFT-GIT and TST were performed for each subject. Defi nition of close contacts and index cases

Close household contacts were living in the same house as an index case. MDR-TB patients had shared the same kitchen with the contacts for at least 3 months before treatment.

Nineteen MDR-TB index cases were identifi ed under the DOTS-plus programme at the Department of Health of Changhua Hospital: 17 were men (90%) and two were women (10%), with a mean age of 61.9 years (range 28–82). Nine patients were sputum culture negative and 10 were positive. The duration of exposure was calculated as the period from the onset of active TB symptoms in the index case to the end of the LTBI evaluation. The average duration of exposure for the culture-negative (n = 9) and culture-positive patients (n = 10) was respectively 13 and 34 months. Of the 19 MDR-TB patients, six had com-pleted treatment, with an average treatment duration of 26.5 months; the average treatment time for the remaining 13 patients was 43.7 months. The percent-age of resistance to different drugs in the index cases were as follows: RMP 94.7% (18/19), INH 84.2% (16/19), ethambutol (EMB) 36.8% (7/19) and strepto-mycin (SM) 26.3% (5/19).

Sample collection and measurement

The QFT-GIT test was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.4 Whole blood was

collected into 1) a nil negative control tube (i.e., 1 ml whole blood without antigen or mitogen), 2) a TB an-tigen tube (i.e., 1 ml whole blood containing ESAT-6, CFP-10 and TB 7.7) and 3) a mitogen-positive con-trol tube (i.e., 1 ml whole blood stimulated with mi-togen) for each subject. The tubes were incubated at

37°C for 16–24 h. After centrifuging for 15 min, the harvested plasma was stabilised and refrigerated for at least 4 weeks. The conjugate was then added with plasma samples and standards to an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate and incubated for 120 min at room temperature. The resultant sample was washed and substrate was added. The absorbance was read and interpreted after 30 min.

The results were calculated using QFT-GIT soft-ware. A positive result was interpreted as an IFN-γ level in the sample, after stimulation with ESAT-6 and CFP-10, of ⩾0.35 international units (IU)/ml; a negative result was defi ned as a value of <0.35 IU/ml or the mitogen tube minus Nil value ⩾0.5 IU/ml; the result was indeterminate when the mitogen value minus Nil value was <0.5 IU/ml or when the Nil value was >8.0 IU/ml.

The TST (purifi ed protein derivative [PPD] skin test) was carried out 2 weeks after blood collection for QFT-GIT, and two-step testing (4 weeks between the fi rst and second PPD tests) was performed to pre-vent an anamnestic response (i.e., the booster effect). PPD RT23 with 2 tuberculin units (TU)/0.1 ml Man-toux test was used. The diameter of the induration was read and recorded 48–72 h after intradermal injec-tion. Technicians trained in the BCG vaccination pro-gramme carried out the TSTs and read and recorded the results. A 10-mm TST response was used as the cut-off. An induration of ⩾10 mm was recorded as a positive result.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and chest X-ray were used to de-termine the prevalence of TB infection. QFT-GIT and TST results and the results for BCG-vaccinated and non-BCG-vaccinated subjects were compared. Kappa (κ) statistics were used to measure the level of consis-tency of QFT-GIT and TST. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to assess the difference between the two tests. Risk factors were analysed using the χ2 test.

RESULTS

Of a total of 78 subjects, 38 were men (49%) and 40 were women (51%), with a mean age of 35.6 years. Most of the 78 subjects had been BCG vaccinated (69/78, 89%). The majority of the index cases were parents of the contacts (38/78, 49%). Forty contacts (51%) had lived with the index case for 10–20 years, and 51 (65%) lived in the same building as the index case. Of the 78 subjects, 27 (35%) had an abnormal chest X-ray but none presented with active TB, and sputum examinations were therefore not performed. Nine subjects had lung fi brosis, and 23 had other lung diseases. Of the 78 subjects, 3 had diabetes, 5 had chronic hepatitis, 2 had hypertension and 1 had an-other chronic disease.

Close contacts of MDR-TB patients 3

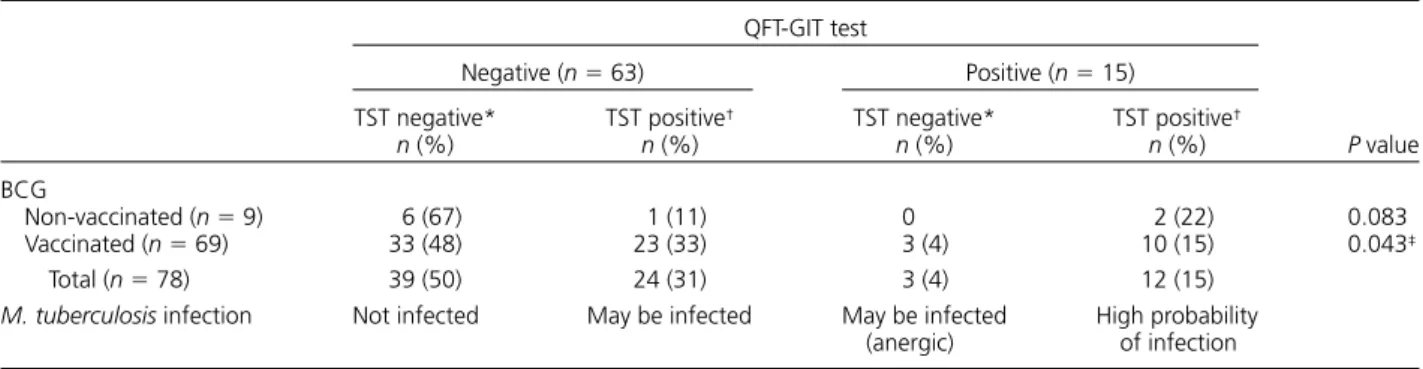

negative, while 15 (15/78, 19%) were positive; 42 (42/ 78, 54%) were TST-negative and 36 (36/78, 46%) were TST-positive. Of the 36 TST-positive subjects, 33 had been BCG-vaccinated and 3 had not (Table 1).

Thirty-nine subjects were both QFT-GIT and TST negative; 24 were TST-positive but QFT-negative; three were TST-negative but QFT-positive; and 12 were positive for both tests (Table 2). On comparing the QFT-GIT and TST results, the consistency of the two tests in nine non-vaccinated subjects was 89% (κ = 0.73, P < 0.05), while a 62% correlation between the two tests was found in those who were vaccinated (κ = 0.23, P < 0.02; Table 3). Statistical analysis, however, showed signifi cant correlation between the two tests (P < 0.05).

QFT-GIT-positive subjects were found to have sig-nifi cantly higher TST results than QFT-GIT-negative subjects despite their vaccination status (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001; Table 4).

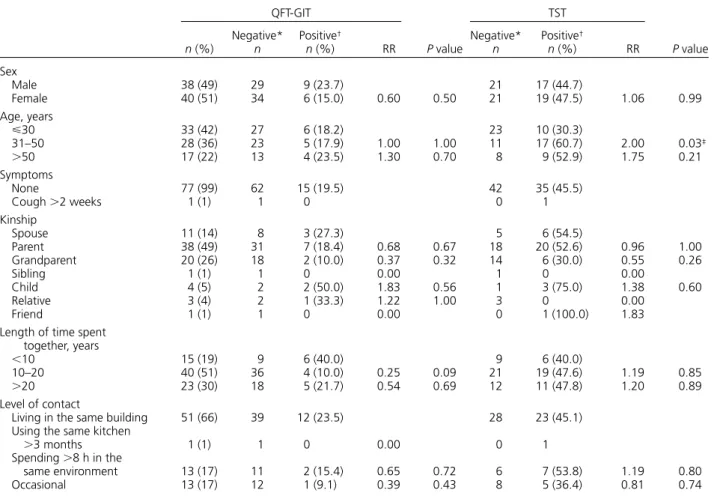

None of the factors investigated, including kinship, length of time spent together and level of contact with an index case, were seen to affect QFT-GIT results and relatively high relative risk values (Table 5). The Table 1 QFT-GIT test and TST results in the study group

BCG Total n (%) Non-vaccinated (n = 9) n (%) Vaccinated (n = 69) n (%) QFT-GIT Negative 7 (78) 56 (81) 63 (81) Positive 2 (22) 13 (19) 15 (19) TST Negative* 6 (67) 36 (52) 42 (54) Positive† 3 (33) 33 (48) 36 (46) *TST <10 mm. † TST ⩾10 mm.

QFT-GIT = QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube; TST = tuberculin skin test; BCG =

bacille Calmette-Guérin.

Table 2 QFT-GIT and TST results vs. BCG vaccination status in the study group

QFT-GIT test P value Negative (n = 63) Positive (n = 15) TST negative* n (%) TST positive† n (%) TST negative* n (%) TST positive† n (%) BCG Non-vaccinated (n = 9) 6 (67) 1 (11) 0 2 (22) 0.083 Vaccinated (n = 69) 33 (48) 23 (33) 3 (4) 10 (15) 0.043‡ Total (n = 78) 39 (50) 24 (31) 3 (4) 12 (15)

M. tuberculosis infection Not infected May be infected May be infected

(anergic) High probability of infection *TST <10 mm. † TST ⩾10 mm. ‡ P < 0.05.

QFT-GIT = QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube; TST = tuberculin skin test; BCG = bacille Calmette-Guérin.

Table 3 Consistency of QFT-GIT and TST

TST/QFT-GIT test Kappa P value Agreement % −∕− −∕+ +∕− +/+ BCG Non-vaccinated (n = 9) 6 0 1 2 0.73 0.023* 89 Vaccinated (n = 69) 33 3 23 10 0.23 0.020* 62 *P < 0.05.

QFT-GIT = QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube; TST = tuberculin skin test; BCG = bacille Calmette-Guérin.

Table 4 Comparison of QFT-GIT test and TST results (Mann-Whitney U-test)

QFT-GIT test

TST

P value

n Mean,* mm SD Minimum Maximum

BCG Non-vaccinated (n = 9) Negative 7 3.14 5.43 0 14 Positive 2 12.50 0.71 12 13 Vaccinated (n = 69) Negative 56 7.79 5.30 0 20 0.001* Positive 13 14.69 6.17 0 24 *P < 0.05.

4 The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease

majority of the demographic factors failed to show any signifi cant effect on TST results. The 31–50 year age group was the only factor to have a statistically signifi cant effect on TST results.

DISCUSSION

We found that previous BCG vaccination signifi cantly affected QFT-GIT and TST results. In the nine non-BCG-vaccinated subjects, the percentage of positive results for the two tests was similar (QFT-GIT 2/9, 22% vs. TST 3/9, 33%). However, in the 69 BCG vac-cinated subjects, the difference between the two tests was greater: 13/69 (19%) were QFT-GIT-positive and 33/69 (48%) were TST-positive. This indicated that the PPD antigen used in TST led to false-positive results in BCG-vaccinated subjects and in those with NTM infection. Overall, 36 subjects (46%) were TST-positive, and 15 (19%) were QFT-GIT-positive. There seemed to be an inconsistency in the results of the two tests. Nevertheless, similar fi ndings were reported in a study carried out in Melbourne, Australia, where there were fewer positive QFT-GIT results (6.7%) than TST results (33%).13

As both TST and QFT measure the presence of M. tuberculosis, our results could be interpreted as follows:

1 Absence of mycobacterial infection: 39 subjects in our study were not infected, as both TST and QFT were negative.

2 Possible mycobacterial infection: a positive TST result with a negative QFT reaction may be due to previous exposure to NTM or history of BCG vaccination for which an organism closely related to the tubercle bacillus, M. bovis, is used as an an-tigen. Either could have led to a false-positive reaction.14

3 Anergy: negative TST but positive QFT may indi-cate that the subject has TB infection, but that the TST is false-negative. This could occur espe-cially in the case of immunosuppression or natural waning of immunity, or due to the effect of NTM such as M. kansasii, M. marinum or M. szulgai14

on QFT.

4 A high probability of infection: both tests indi-cated the presence of M. tuberculosis, and there-fore the 12 subjects with positive results to both tests from our study needed close follow-up. Table 5 Relationship between demographic data and QFT-GIT and TST results

QFT-GIT P value TST P value n (%) Negative* n Positive† n (%) RR Negative* n Positive† n (%) RR Sex Male 38 (49) 29 9 (23.7) 21 17 (44.7) Female 40 (51) 34 6 (15.0) 0.60 0.50 21 19 (47.5) 1.06 0.99 Age, years ⩽30 33 (42) 27 6 (18.2) 23 10 (30.3) 31–50 28 (36) 23 5 (17.9) 1.00 1.00 11 17 (60.7) 2.00 0.03‡ >50 17 (22) 13 4 (23.5) 1.30 0.70 8 9 (52.9) 1.75 0.21 Symptoms None 77 (99) 62 15 (19.5) 42 35 (45.5) Cough >2 weeks 1 (1) 1 0 0 1 Kinship Spouse 11 (14) 8 3 (27.3) 5 6 (54.5) Parent 38 (49) 31 7 (18.4) 0.68 0.67 18 20 (52.6) 0.96 1.00 Grandparent 20 (26) 18 2 (10.0) 0.37 0.32 14 6 (30.0) 0.55 0.26 Sibling 1 (1) 1 0 0.00 1 0 0.00 Child 4 (5) 2 2 (50.0) 1.83 0.56 1 3 (75.0) 1.38 0.60 Relative 3 (4) 2 1 (33.3) 1.22 1.00 3 0 0.00 Friend 1 (1) 1 0 0.00 0 1 (100.0) 1.83

Length of time spent together, years

<10 15 (19) 9 6 (40.0) 9 6 (40.0)

10–20 40 (51) 36 4 (10.0) 0.25 0.09 21 19 (47.6) 1.19 0.85

>20 23 (30) 18 5 (21.7) 0.54 0.69 12 11 (47.8) 1.20 0.89

Level of contact

Living in the same building 51 (66) 39 12 (23.5) 28 23 (45.1)

Using the same kitchen

>3 months 1 (1) 1 0 0.00 0 1 Spending >8 h in the same environment 13 (17) 11 2 (15.4) 0.65 0.72 6 7 (53.8) 1.19 0.80 Occasional 13 (17) 12 1 (9.1) 0.39 0.43 8 5 (36.4) 0.81 0.74 *<10 mm. † ⩾10 mm. ‡ P < 0.05.

Close contacts of MDR-TB patients 5

Similar results were noted in a study conducted by Mahomed et al. in 2006, who compared the TST with the three generations of QuantiFERON tests.6

They also reported a lack of consistency between the TST and QFT results and between the different gen-erations of QuantiFERON tests. The rates of positiv-ity for the different tests varied from 81% for the TST (10 mm as cut-off point), 60% for QFT, 38% for QFT-G to 56% for QFT-GIT. These results sug-gested that the extra M. tuberculosis-specifi c antigen used in the QFT-GIT method (TB antigen 7.7), or the immediate incubation of whole blood at 37°C after collection had increased the sensitivity of the QFT-GIT test as compared to the other generations. The correlation of the tests for BCG-vaccinated individu-als in the study by Mahomed et al. was 69% (κ = 0.32), comparable to our result of 62% (κ = 0.23). A Korean study also found that the sensitivity of QFT-GIT in the diagnosis of LTBI infection was higher than that of TST in immunocompromised patients.10

Both TST and QFT have advantages and disadvan-tages. The drawbacks of TST include the need for pa-tients to return for test reading, a frequent reading bias, variability in test application, booster effect, false-negative results due to intercurrent immunosuppres-sion, and low specifi city in previously BCG-vaccinated subjects. The QFT test performs better in these as-pects, but requires blood collection, processing within 12 h of collection, and it lacks sensitivity to previous infections. In addition, QFT is relatively more expen-sive and requires technicians with specifi c laboratory skills and experience;14 as a result, increased costs are

involved for screening large numbers of close con-tacts of confi rmed MDR-TB patients.

The US CDC recommends a 6–9 month LTBI regi-men with INH for high-risk subjects, such as those with human immunodefi ciency virus infection or or-gan transplant recipients with positive QFT or TST results.2,3 The German Central Committee Against

Tu-berculosis, however, recommends confi rming positive TST results using an interferon-gamma release assay (QFT or T-SPOT.TB) before offering LTBI treatment.15

In our study, no treatment was given to any of our subjects, as our research involved close contacts of MDR-TB patients and second-line drugs are gener-ally more toxic. After reviewing their symptoms, risk assessment, radiography and other medical and diag-nostic evaluations, it was decided that more precise verifi cation was needed to confi rm active TB infec-tion. Treatment was therefore not indicated at this stage. However, regular chest X-rays and follow-up of these subjects were undertaken, and to date no ac-tive TB has been reported.

The Taiwanese Center for Disease Control imple-mented the DOTS-Plus programme in May 2007, and it was hoped that with this active treatment pro-gramme and strict supervision of MDR-TB patients, patients could be treated early and the risk for

dis-ease transmission reduced. Contacts who are already infected should be closely monitored and treated as soon as possible. In terms of prevention, it is still dif-fi cult to determine suitable treatment due to the like-lihood of a drug-resistant strain presenting in con-tacts of MDR-TB patients.

CONCLUSION

In a total of 78 patients, 46% were TST-positive and 19% were QFT-GIT-positive. Twelve (15%) were positive with both tests. Both TST and QFT-GIT can be used to detect TB disease or LTBI. As they do not measure the same components of the immunological response, they are not interchangeable. Both tests should be used in conjunction with risk assessment, radiography and other medical and diagnostic eval-uations. The QFT-GIT test can be especially useful, and more specifi c than TST, in detecting LTBI in coun-tries such as Taiwan, which has high BCG vaccina-tion coverage.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the staff of Chan-ghua Hospital and the local health departments for their time and effort in helping with the data collection. They also thank the Tai-wan Department of Health for their fi nancial support of this study.

References

1 World Health Organization. Drug and multidrug-resistant tu-berculosis (MDR-TB). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2009. http:// www.who.int/tb/challenges/mdr/en/index.html Accessed De-cember 2009.

2 Mazurek G H, Villarino M E. Guidelines for using the Quanti-FERON®-TB test for diagnosing latent Mycobacterium

tuber-culosis infection. Centers for disease control and prevention. MMWR 2003; 52 (RR02): 15–18.

3 Mazurek G H, Jereb J, LoBue P, Iademarco M F, Metchock B, Vernon A. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR 2005; 54 (RR15): 49–55.

4 Cellestis. QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube method and tech-nical information. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Cellestis, 2009. http://www.cellestis.com/IRM/Content/aust/qtfproducts_tbgold intube_techinfo.html Accessed December 2009.

5 Pollock J M, McNair J, Bassett H, et al. Specifi c delayed-type hypersensitivity responses to ESAT-6 identify tuberculosis-i nfected cattle. J Cltuberculosis-in Mtuberculosis-icrobtuberculosis-iol 2003; 41: 1856–1860. 6 Mahomed H, Hughes E J, Hawkridge T, et al. Comparison of

Mantoux skin test with three generations of a whole blood IFN-γ assay for tuberculosis infection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006; 10: 310–316.

7 Brock I, Munk M E, Kok-Jensen A, Andersen P. Performance of whole blood IFN-γ test for tuberculosis diagnosis based on PPD or the specifi c antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001; 5: 462–467.

8 Vordermeier H M, Chambers M A, Cockle P J, Whelan A O, Simmons J, Hewinson R G. Correlation of ESAT-6-specifi c gamma interferon production with pathology in cattle follow-ing Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination against experimen-tal bovine tuberculosis. Infect Immun 2002; 70: 3026–3032.

6 The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease

9 Teixeira L, Perkins M D, Johnson J L, et al. Infection and dis-ease among household contacts of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001; 5: 321–328. 10 Kim E Y, Lim J E, Jung J Y, et al. Performance of the tuberculin

skin test and interferon-γ release assay for detection of tuber-culosis infection in immunocompromised patients in a BCG-vaccinated population. BMC Infect Dis 2009; 9: 207. 11 Katial R K, Hershey J, Purohit-Seth T, et al. Cell-mediated

im-mune response to tuberculosis antigens: comparison of skin testing and measurement of in vitro gamma interferon produc-tion in whole-blood culture. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001; 8: 339–345.

12 Kobashi Y, Obase Y, Fukuda M, Yoshida K, Miyashita N, Oka M. Clinical reevaluation of the QuantiFERON TB-2G test as a diagnostic method for differentiating active tuberculosis from

non-tuberculous mycobacteriosis. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43: 1540–1546.

13 Vinton P, Mihrshahi S, Johnson P, et al. Comparison of Quanti-FERON-TB Gold In-Tube test and tuberculin skin test for identifi cation of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in healthcare staff and association between positive test results and known risk factors for infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30: 215–221.

14 Kunst H. Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: the poten-tial role of new technologies. Respir Med 2006; 100: 2098– 2106.

15 Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Meywald-Walter K, et al. Compara-tive performance of tuberculin skin test, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube Assay, and T-SPOT.TB test in contact investiga-tions for tuberculosis. Chest 2009; 135: 1010–1018.

R É S U M É

C O N T E X T E : Pour la détection de l’infection par

Myco-bacterium tuberculosis, on peut utiliser à la fois le test

cu-tané tuberculinique (TST) et le test QuantiFERON®-TB

Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT). Une réaction positive à l’un ou l’autre de ces tests correspond à une infection tuber-culeuse latente (LTBI). Ces tests peuvent être utilisés pour investiguer le taux d’infection chez les contacts de patients atteints de tuberculose à germes multirésistants (TB-MDR).

O B J E C T I F : Evaluer à Taiwan le statut de transmission

des patients TB-MDR en examinant leurs contacts étroits, et comparer l’effi cacité des TST et QFT-GIT.

S C H É M A : On a réalisé des clichés thoraciques, des TST

et des QFT-GIT chez les sujets en contact au domicile avec des patients atteints de TB-MDR confi rmée afi n de connaître leur statut en matière d’infection.

R É S U LTAT S : On a inclus au total 78 contacts étroits de

patients atteints de TB-MDR. La majorité des patients TB-MDR étaient des parents des contacts étroits et vi-vaient dans le même bâtiment. Le TST a été positif chez 56% des sujets et le test QFT-GIT chez 19%. Ceux-ci étaient atteints de LTBI et susceptibles de développer ul-térieurement une TB-MDR active. Il existe un manque de cohérence entre les résultats du TST et ceux du QFIT chez les sujets vaccinés antérieurement par le bacille Calmette-Guérin.

C O N C L U S I O N : Comme les contacts au domicile des

pa-tients TB-MDR sont susceptibles de développer la LTBI, un suivi et une surveillance sont indispensables pour leur fournir un traitement et réduire l’apparition d’une infection active.

R E S U M E N

M A R C O D E R E F E R E N C I A : La prueba cutánea de la

tu-berculina (TST) y la prueba QuantiFERON®-TB Gold

En Tubo (QFT-GIT) se pueden utilizar en la detección de la infección por Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Una reacción positiva a alguna de estas pruebas refl eja una infección tuberculosa latente (LTBI). Estos ensayos se pueden usar con el propósito de investigar la tasa de in-fección en los contactos de los pacientes con tuberculo-sis multidrogorretuberculo-sistente (TB-MDR).

O B J E T I V O : Se buscó evaluar la situación de la

transmi-sión en los pacientes con MDR-TB en Taiwán, al exami-nar sus contactos cercanos y comparar la efi cacia diag-nóstica de la TST y las pruebas QFT.

M É T O D O : Con el propósito de defi nir el estado de

con-tagiosidad, se practicaron la radiografía de tórax, la TST y la prueba QFT a los contactos domiciliarios de los pa-cientes con TB-MDR confi rmada.

R E S U LTA D O S : Participaron en el estudio 78 contactos

cercanos de pacientes con TB-MDR confi rmada. La ma-yoría de los pacientes con TB-MDR eran familiares de sus contactos cercanos y residían en el mismo edifi cio. El cuarenta y seis por ciento de las personas tuvo una reacción TST positiva y el 19% resultados positivos en la prueba QFT. Estas personas presentaban una LTBI y existía la posibilidad de que evolucionaran hacia una TB-MDR activa. Se observó incongruencia entre los re-sultados de ambas pruebas en las personas con ante-cedente de vacunación antituberculosa.

C O N C L U S I Ó N : Los contactos domiciliarios de pacientes

con TB-MDR pueden contraer una LTBI, por lo cual es obligatorio practicar el seguimiento y la vigilancia de estas personas, con el propósito de suministrar el trata-miento necesario y disminuir la transmisión activa de la enfermedad.