Title:

Pegylated-interferon Alpha therapy for Treatment-experienced Chronic Hepatitis B Patients

Authors:

Ming-Lun Yeh1,3*,Cheng-Yuan Peng2*, Chia-Yen Dai1,3,4, Hsueh-Chou Lai2, Chung-Feng Huang1,4,5,8, Ming-Yen Hsieh1,7, Jee-Fu Huang1,4,6, Shinn-Cherng Chen1,4, Zu-Yau Lin1,4,Ming-Lung Yu1,4,8**, Wan-Long Chuang1,4**

Affiliation:

1 Division ofHepatobiliary, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

2Division of Hepatogastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

3 Graduate Institute of Medicine, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

4 Faculty of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

5 Department of Occupational Medicine, Kaohsiung Municipal Ta-Tung Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

6Departmentof Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Municipal Hsiao-Kang Hospital,Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

7Departmentof Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Municipal Ta-Tung Hospital,Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

8 Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

*Equal contribution

**Correspondence, equal contribution:

Dr. Ming-Lung Yu: Hepatobiliary Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, No.100, Tzyou 1st Road, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan (fish6069@gmail.com)

Dr. Wan-Long Chuang: Hepatobiliary Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, No.100, Tzyou 1st Road, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan (waloch@kmu.edu.tw)

CONTRIBUTIONS OF AUTHORS

Conception and design:LunYeh, Cheng-Yuan Peng, Chia-Yen Dai,

Ming-21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40

Lung Yu, Wan-Long Chuang.

Acquisition of data: Ming-Lun Yeh, Cheng-Yuan Peng, Chia-Yen Dai, Hsueh-Chou

Lai, Chung-Feng Huang, Ming-Yen Hsieh, Jee-Fu Huang, Shinn-Cherng ChenZu-Yau Lin,Ming-Lung Yu,Wan-Long Chuang.

Data analysis and interpretation:Ming-Lun Yeh, Cheng-Yuan Peng, Chia-Yen Dai,

Hsueh-Chou Lai, Chung-Feng Huang, Ming-Yen Hsieh, Jee-Fu Huang, Shinn-Cherng ChenZu-Yau Lin,Ming-Lung Yu,Wan-Long Chuang.

Manuscript drafting and critical revising: Ming-LunYeh, Cheng-Yuan Peng, Wan-Long Chuang, Ming-Lung Yu.

Word count: Abstract: 271

Text: 2683 Figures: 4

Tables: 3

Key words: chronic hepatitis B, retreatment, pegylated interferon α-2a, HBeAg

seroconversion, HBsAg loss

Abbreviations: Peg-IFN, pegylated interferon; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HCC,

hepatocellular carcinoma; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

antigen; NUC, nucleos(t)ide analogue; ETV, entecavir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ULN, upper limit of normal; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Abstract:

Background: There were limited studies on pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN) therapy

for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients who failed or relapsed to previous antiviral therapy.

Objectives: We aimed to investigate the effect of Peg-IFN therapy in

treatment-experienced CHB patients. 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82

Study design: A total of 57 treatment-experienced CHB patients at two medical

centers were enrolled. All patients were treated with Peg-IFN α-2a 180 μg weekly for 24 or 48 weeks. Hepatitis B serological markers and viral loads were tested every3 months till 1 year after stopping Peg-IFN therapy. The endpoints were HBV DNA <2000IU/mL, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion, and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss at 12 months posttreatment.

Results: In HBeAg-positive patients, 25.0%, 29.2%, and 12.5% of patients achieved

HBeAgseroconversion, HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL and the combined response at 12 months posttreatment. Prior IFN therapy, baseline high ALT level, low creatinine level ,undetectable HBV DNA at 12 weeks and decline in HBV DNA >2 log10 IU/mL at 12 weeks of therapy were factors associated with treatment response. In HBeAg-negative patients, 9.1%, 15.2%, and 6.1% of patients achieved undetectable HBV DNA, HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL, and HBsAg loss at 12 months post-treatment, respectively. There was no factor significantly associated with treatment response in HBeAg-negative patients. The median HBsAg level declined from 3.3 to 2.5 log10 IU/mL in all patients and the 5-year cumulative rate of HBsAg loss was 9.8% in HBeAg-negative patients. Overall, none of the patients prematurely discontinued Peg-IFN therapy.

Conclusions: Peg-IFN re-treatment is effective for a number of HBeAg-positive

83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101

treatment-experienced patients, but has limited efficacy for HBeAg-negative

treatment-experienced patients. Nevertheless, Peg-IFN might facilitate HBsAg loss in HBeAg-negative treatment-experienced patients.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a global health problem, with an estimated 350 million people being chronically infected.[1]CHB is also the most common cause of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Asia.[2]Approximately 15-40% of CHB patients will eventually develop cirrhosis, hepatic failure and HCC. Reduced risk of hepatic decompensation and HCC and reversion of hepatic fibrosis by long-term anti-HBV therapy have been recently demonstrated.[3,4,5,6]

The current recommended first-line antiviral therapies for CHB include pegylated-102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122

interferon (Peg-IFN) α-2a, entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). Compared with nucleos(t)ide analogue (NUC) therapy, Peg-IFN therapy has the advantages of finite duration, absence of resistance and higher rates of anti-HBe seroconversion with 12 months of therapy. Nonetheless, Peg-IFN therapy has the disadvantages of moderate antiviral effect, inferior tolerability and risk of adverse events. Although Peg-IFN therapy has higher rates of anti-HBe seroconversion with 12 months of therapy, the efficacy is still unsatisfactory. For Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients, one year of Peg-IFN therapy achieved only 22-27% of HBeAg seroconversion rate at the end of treatment, which increased to 35% at 1-2 years after stopping treatment.[7] For HBeAg-negative patients, one year of Peg-IFN therapy achieved 63% of undetectable HBV DNA rate; nonetheless, the rate rapidly dropped to 15% at 1 year after stopping treatment.[8]

Although NUC therapy has the advantage of potent antiviral effect, poor durability of effectiveness after stopping NUCs is encountered in the majority of patients. In a previous study by Reijnders J.G. et al., over 40% and 50% of HBeAg-positive

patients experienced HBeAg seroreversion and recurrent viremia 4 years after HBeAg seroconversion, respectively.[9] One-year and 3-year relapse rates of 44% and 52% were also reported in HBeAg-negative patients after stopping lamivudine therapy.[10] Another recent study investigating off-therapy durability of ETV in HBeAg-negative 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141

CHB patients showed that 45.3% of the 95 patients had clinical relapse within 1-year after stopping ETV therapy.[11]

Thus, re-treatment of CHB is an unmet issue in a substantial proportion of patients after antiviral therapy. Moreover, limited studies have been reported on Peg-IFN treatment for patients who failed or relapsed to previous antiviral therapy. Herein, we aimed to investigate the efficacy of Peg-IFN therapy in treatment-experienced CHB patients and the factors associated with treatment efficacy.

PATIENTS and METHODS

A total of57 treatment-experienced CHB patients who failed or relapsed to previous antiviral therapy at 2 medical centers were enrolled into the present study. The

inclusion criteria included HBV DNA >20,000 IU/mL and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels between 1–10 fold upper limit of normal (ULN) for HBeAg-positive patients and HBV DNA >2000 IU/mL and ALT levels between 1–10x ULN for HBeAg-negative patients. Exclusion criteria included HBV antiviral therapy within 6 months of enrollment; hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus

co-infection; decompensated liver disease ( Child–Pugh score ≥ 7) ; pregnant or breast-feeding women; cytopenia (white blood count <1500 cells/m3, hemoglobin <12 mg/dL; platelet <90,000 cells/m3); evidence of alcoholism or drug abuse; any other 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160

known disease that was not suitable for Peg-IFN therapy. All HBeAg-positive patients received Peg-IFN α-2a 180 μg weekly for 24 (as per reimbursement of the National Health Insurance of Taiwan) or 48 weeks (as per patients’ willing) and HBeAg-negative patients for 48 weeks.

Liver biochemistry, HBV serological markers, HBV DNA, and HBsAg levels were tested before treatment and then every3 months till 1 year after stopping Peg-IFN treatment. HBeAg was detected using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA). Serum HBV DNA levels were determined using the CobasAmpliPrep/CobasTaqMan HBV assay(CAP/CTM version 2.0, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA; dynamic range 20 IU/mL – 1.7x108IU/mL). HBV genotype was determined using a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method as described earlier.[12] Serum HBsAg levels were quantified using the Architect HBsAg QT assay (Abbott Diagnostic, Germany). The sensitivity of Architect assay ranged from 0.05 to 250 IU/mL. Samples with HBsAg level higher than 250 IU/mL were further diluted at1:500 and 1:1000 to obtain the reading within the range of the calibration curve.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of Good Clinical Practice and was approved by the ethic committee of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179

from all patients.

The primary efficacy parameters were combined response, defined as HBeAg seroconversion plus HBV DNA <2000IU/mL 12 months post-treatment, in HBeAg-positive patients and virological response, defined as HBV DNA <2000IU/mL 12 months post-treatment, in HBeAg-negative patients. Secondary efficacy parameters included HBeAg seroconversion, HBVDNA <2000 IU/mL and HBsAg loss12 months post-treatment in HBeAg-positive patients; undetectable HBV DNA and HBsAg loss12 months post-treatment in HBeAg-negative patients.

Factors associated with primary treatment response including baseline biochemistry, baseline and on-treatment HBV DNA level, HBsAg level were also analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. These included median, 25th, and 75th percentiles for continuous variables. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were estimated. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing continuous variables. The chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for comparing categorical variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify the independent associated factors. All tests were two-sided, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS 17.0 statistical package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199

RESULTS

The baseline demographics of all and HBeAg-positive, -negative

treatment-experienced CHB patients are shown in Table 1. Most of the patients were male with a median age of 40 years. Prior therapy with interferon (IFN) in around 30% of patients. Of the 40 patients with prior NUC experience, all received lamivudine and three patients developed lamivudine resistant YMDD mutations. The treatment responses of the first course included non-responder(defined as no HBeAg loss for HBeAg-positive and HBV DNA >2000 IU/mL for HBeAg-negative patients at end of treatment), partial responder (defined as HBeAg loss without HBeAg seroconversion for HBeAg-positive and detectable HBV DNA for HBeAg-negative patients at end of treatment) and relapser (definition as HBeAg seroconversion for HBeAg-positive and undetectable HBV DNA for HBeAg-negative patients at end of treatment) in 22 (38.6%), 4 (7.0%) and 31 (54.4%) of patients. Genotype was determined in 55

patients and around 60% of patients were genotype B. Most of the patients (70%) had ALT level of greater than 2 fold ULN. Baseline HBV DNA levels were 6.6, 7.6, and 6.1 log10 IU/mL and baseline HBsAg levels were 3.4, 3.8, and 3.2 log10 IU/mL in all, HBeAg-positive, and -negative patients, respectively.

Efficacy of Peg-IFN α-2a in treatment experienced HBeAg-positive CHB patients

200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218

HBe Agseroconversion

The rates of HBeAg loss were 33.3% (8/24), 33.3% (8/24), and 33.3% (8/24) at the end of therapy, 6 months and 12 months post-treatment, respectively. The treatment responses of Peg-IFN therapy in HBeAg-positive patients were shown in Figure 1A. HBeAg seroconversion rates were 20.8%(5/24), 20.8%(5/24), and 25.0%(6/24) at the end of therapy, 6 months and 12 months post-treatment, respectively. Baseline high ALT level was the only significant factor associated with HBeAg seroconversion at 12 months off therapy (median [25th, 75th percentile]: 177.5 [148-268] U/L vs.88.5 [70.3-144.4] U/L, p = 0.009). Four of the 8 patients (50%) with prior IFN therapy achieved HBeAg seroconversion at 12 months off therapy compared to only 2 of 16 patients (12.5%) with prior NUC therapy (p = 0.129).

HBV virological response

The rates of achieving HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL were 41.7%(10/24), 33.3%(8/24), and 29.2%(7/24) at the end of therapy, 6 months, and 12 months post-treatment, respectively. Three of the 10 HBeAg-positive patients who had HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at end of therapy happened virological relapse (HBV DNA >2000 IU/mL) and 1 of the 3 patients had clinical relapse (HBV DNA >2000 IU/mL + ALT >2x ULN) after discontinuation of Peg-IFN therapy. Prior IFN therapy (62.5%[5/8]in prior IFN vs. 12.5%[2/16] in prior NUC, p = 0.021), baseline ALT level greater than 5 fold 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237

ULN(100.0% [3/3] vs. 19.0% [4/21], p = 0.017), and undetectable HBV DNA at week 12 of therapy (100.0% [3/3] vs. 19.0% [4/21], p = 0.017) were significant factors associated with HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at 12 months off therapy.

Combined response

There were 16.7% (4/24), 12.5% (3/24), and 12.5% (3/24) of patients who achieved HBeAg seroconversion plus HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at the end of therapy, 6

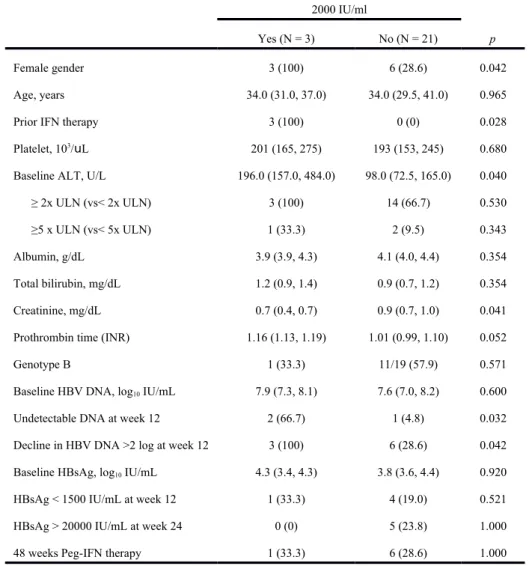

months, and 12 months post-treatment, respectively. Female, prior IFN therapy, baseline high ALT level, low creatinine level ,undetectable HBV DNA at 12 weeks and decline in HBV DNA >2 log10 IU/mL at 12 weeks of therapy were significant factors associated with HBeAg seroconversion plus HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at 12 months post-treatment (p = 0.042, 0.028, 0.040, 0.041, 0.032 and 0.042, respectively) (Table 2.).

Efficacy of Peg-IFN α-2a in treatment experienced HBeAg-negative CHB patients

At the end of therapy, 69.7% (23/33) and 93.9% (31/33)of HBeAg-negative

patients achieved HBV DNA undetectable and HBV DNA<2000 IU/mL, respectively. (Figure 1B) However, the rates dramatically decreased to 6.1% (2/33)and 24.2% (8/33), respectively, at 6 months post-treatment, and to 9.1% (3/33) and 15.2% (5/33), respectively, at 12 months post-treatment. For HBeAg-negative patients, 26 of 31 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257

patients who had HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at end of therapy happened virological relapse and 4 of the 26 patients had clinical relapse after discontinuation of Peg-IFN therapy. There was no factor significantly associated with HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at 12 months off therapy. (Table 3) Undetectable HBV DNA at week 12 of therapy tended to be associated with undetectable HBV DNA at 12 months post-treatment (p = 0.067) and none of the 19 patients with detectable HBV DNA at week 12 of therapy achieved undetectable HBV DNA at 12 months post-treatment.

On-treatment HBsAg level decline and off-treatment HBsAg seroclearance

The median HBsAg level from baseline to 12 months post-treatment declined from 3.4 to 2.6 log10 IU/mL in all patients, from 3.8 to 2.7 log10 IU/mL in HBeAg-positive patients, and from 3.2 to 2.5 log10 IU/mL in HBeAg-negative patients. (Figure 2) There was no difference in HBsAg decline between HBeAg-positive patients with and without HBeAg seroconversion. HBeAg-negative patients who achieved HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at 12 months post-treatment showed continued HBsAg decline after stopping Peg-IFN. In contrast, a rebound in HBsAg level after stopping Peg-IFN was found in HBeAg-negative patients who did not achieve HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at 12 months post-treatment. (Figure 3)

HBsAg seroclearance was achieved in 1 (3.0%), 2 (6.1%), and 2 (6.1%) patients 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276

at the end of therapy, 6 months, and 12 months post-treatment, respectively. (Figure 1B) One of the patients with HBsAg seroclearance had seroconverted to anti-HBsAb. One patient who achieved HBsAg seroclearance at 6 months post-treatment suffered HBsAg reversion at 12 months post-treatment. Another patient had HBsAg

seroclearance at 2 years post-treatment. For HBeAg-negative patients with long-term follow-up of median 36 months (25th , 75 th percentiles: 18, 48 months) , the 5-year cumulative rate of HBsAg seroclearance was 9.8%. (Figure 4)

Safety

Overall, none of the patients prematurely discontinued Peg-IFN α-2a therapy and none of the patients had dose modification. Fifty-four patients (94.7%) completed 12 months of post-treatment follow-up. Three patients (5.3%) did not complete follow-up because of liver decompensation related to hepatitis B flare at 2, 6, and 7 months post-treatment. All the three patients started NUC therapy immediately with subsequent normalization of liver function.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated that Peg-IFN therapy for treatment-experienced CHB was effective for HBeAg-positive patients in terms of HBeAg seroconversion (25%) and virological response (29%). By contrast, Peg-IFN retreatment was unsatisfactory 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296

for combined serological and virological responses (12.5%) in HBeAg-positive patients and for virological response (15%) in HBeAg-negative patients.

Nevertheless, Peg-IFN therapy was well tolerated in treatment-experienced CHB and might facilitate HBsAg loss in HBeAg-negative CHB patients.

The registration trial of Peg-IFN α-2a for HBeAg-positive CHB demonstrated that 32% and 14% of patients achieved HBeAg seroconversion and HBV DNA <400 copies/mL 6 months post-treatment, respectively.[7] A recent randomized control trial, NEPTUNE study, further confirmed that 48 weeks of Peg-IFN α-2a at 180 μg/week is the most appropriate regimen with the highest rates of HBeAg

seroconversion, DNA suppression and combined response.[13] However, there were limited data about Peg-IFN therapy in treatment-experienced CHB in the literature. We demonstrated that only 20.8%, 33.3% and 12.5% of treatment-experienced HBeAg-positive CHB patients achieved HBeAg seroconversion, DNA <2000 IU/mL, and combined response 6 months off Peg-IFN retreatment, respectively. In the

NEPTUNE study, 22.9% and 11.4% of patients achieved HBeAg seroconversion and HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL, respectively, at 6 months off 24 weeks of Peg-IFN therapy, whereas these rates increased to 36.2% and 30%, respectively, with 48 weeks of therapy.[13] A large proportion of patients (71%) in our study received only 24 weeks of Peg-IFN due to financial constraint, which might be partly related to the lower 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315

response rates. Nonetheless, the duration of therapy appeared not related to treatment response in our study, although small number of cases might limit statistical analysis. One interesting finding was that the poor response was mainly found in patients with prior NUC therapy. In patients with prior IFN therapy, re-treatment with Peg-IFN achieved equal or better response than naïve patients. The reason why a relatively poor response was found in patients with prior NUC therapy needs further

investigation.

Marcellin P. et al. reported the initial phase III study of Peg-IFN therapy in patients with HBeAg-negative CHB and demonstrated that 48 weeks of Peg-IFN Alfa-2a mono therapy achieved HBV DNA<400 and<20,000 copies/mL 24 weeks post-treatment in 19% and 43% of patients, respectively.[8] Of the Peg-IFN mono therapy group, 10% of patients had prior lamivudine (4%) or IFN alfa (6%) use. A long-term follow-up study showed that 31% and 5% of patients achieved HBV DNA ≤2000 IU/mL and HBsAg clearance at 1 year post-treatment, respectively.[14] Our study showed an even lower rate of HBV DNA ≤2000 IU/mL (15.2%) but a similar HBsAg clearance rate (6.1%) in treatment-experienced patients. The rapid re-appearance of HBV DNA after stopping Peg-IFN for HBeAg-negative patients was also observed in our study. The results suggest the need for a more stringent selection of treatment-experienced patients for retreatment with Peg-IFN and closer monitoring after 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334

stopping Peg-IFN.

Serum HBsAg levels have been associated with treatment response to Peg-IFN therapy. On-treatment declines in HBsAg level could predict treatment response or failure in HBeAg-positive patients.[15,16] Further studies identified the positive predictive role of HBsAg level <1500 IU/mL at week 12 and negative predictive role of HBsAg level >20,000 IU/mL at week 24.[13,17,18,19] ForHBeAg-negative patients, on-treatment HBsAg decline of <0.5 log at week 12,<10% at week 24, and absence of any decline in HBsAg level with <2 log decline in HBV DNA level at week 12 were reported as negative predictors of HBV DNA suppression and/or HBsAg loss after stopping Peg-IFN therapy.[19,20,21] Our recent study demonstrated that a serum HBsAg cut-off of 150 IU/mL at week 12 strongly predicts sustained response with HBV DNA <312 copies/mL at 24 weeks off Peg-IFN therapy in HBeAg-negative CHB patients infected with genotype B or C.[22] However, the same predictive effect of HBsAg level was not shown in the present study although with the same genotype distribution and racial population. It could be due to the small number of patients. The role of HBsAg level in the prediction of response to Peg-IFN therapy in treatment-experienced CHB patients remains to be studied.

In patients who failed to Peg-IFN therapy might be more prone to develop HCC in the next years. Although, none of our patients either successful treatment or failure 335 336 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353

developed HCC during the follow up period. We still need pay attention to these patients and should have a strict follow up of these patients.

One limitation of this study was its relative small sample size. Whether our results could be extrapolated to treatment-experienced patients in general remains to be studied. Another limitation of this study was that a major proportion of HBeAg-positive patients received only 24 weeks of Peg-IFN therapy, which might have an impact on the response rate. A prospective study with a larger cohort of patients treated with 48 weeks of Peg-IFN is warranted.

In conclusion, retreatment of CHB with Peg-IFN was effective for HBeAg-positive patients in terms of HBeAg seroconversion and virological response, especially for those with prior IFN treatment experience. Although with unsatisfied virological response in the re-treatment of HBeAg-negative patients, Peg-IFN might facilitate HBsAg loss in the clinical setting.

354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 370 371 372 373

Acknowledgements: The authors thank secretary, serum processing helps from

Taiwan Liver Research Foundation (TLRF). They had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Besides, this does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

No current funding sources for this study as detailed online in “PLOS ONE” guide

for authors. The authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394

Reference

1. Dienstag JL (2008) Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med359: 1486-1500. 2. Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, et al. (2006) A comparison

of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 354: 1001-1010.

3. Singal AK, Salameh H, Kuo YF, Fontana RJ (2013) Meta-analysis: the impact of oral anti-viral agents on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther38: 98-106.

4. Wong GL, Chan HL, Mak CW, Lee SK, Ip ZM, et al. (2013) Entecavir treatment reduces hepatic events and deaths in chronic hepatitis B patients With liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 58: 1537-47.

5. Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, et al. (2013) Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 58: 98-107.

6. Lin SM, Yu ML, Lee CM, Chien RN, Sheen IS, et al. (2007) Interferon therapy in HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis reduces progression to cirrhosis and

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 46: 45-52.

7. Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, Marcellin P, Thongsawat S, et al. (2005)

Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 352: 2682-2695.

8. Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, Farci P, Hadziyannis S, et al. (2004) Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 351: 1206-1217.

9. Reijnders JG, Perquin MJ, Zhang N, Hansen BE, Janssen HL (2010) Nucleos(t)ide analogues only induce temporary hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion in most patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 139: 491-498.

395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426

10. Liu F, Wang L, Li XY, Liu YD, Wang JB, et al. (2011) Poor durability of lamivudine effectiveness despite stringent cessation criteria: a prospective clinical study in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 26: 456-460.

11. Jeng WJ, Sheen IS, Chen YC, Hsu CW, Chien RN, et al. (2013) Off-therapy durability of response to entecavir therapy in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatology 58: 1888-96.

12. Mizokami M, Nakano T, Orito E, Tanaka Y, Sakugawa H, et al. (1999) Hepatitis B virus genotype assignment using restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns. FEBS Lett 450: 66-71.

13. Liaw YF, Jia JD, Chan HL, Han KH, Tanwandee T, et al. (2011) Shorter durations and lower doses of peginterferon alfa-2a are associated with inferior hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion rates in hepatitis B virus genotypes B or C. Hepatology 54: 1591-1599.

14. Marcellin P, Bonino F, Yurdaydin C, Hadziyannis S, Moucari R, et al. (2013) Hepatitis B surface antigen levels: association with 5-year response to

peginterferon alfa-2a in hepatitis B e-antigen-negative patients. Hepatol Int 7: 88-97.

15. Chan HL, Wong VW, Chim AM, Chan HY, Wong GL, et al. (2010) Serum HBsAg quantification to predict response to peginterferon therapy of e antigen positive chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 32: 1323-1331.

16. Sonneveld MJ, Rijckborst V, Boucher CA, Hansen BE, Janssen HL (2010) Prediction of sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2b for hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B using on-treatment hepatitis B surface antigen decline. Hepatology 52: 1251-1257.

17. Ma H, Yang RF, Wei L (2010) Quantitative serum HBsAg and HBeAg are strong predictors of sustained HBeAg seroconversion to pegylated interferon alfa-2b in HBeAg-positive patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25: 1498-1506.

18. Piratvisuth T, Marcellin P, Popescu M, Kapprell HP, Rothe V, et al. (2011) Hepatitis B surface antigen: association with sustained response to

peginterferon alfa-2a in hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients. Hepatol Int Jun 24.

19. Chan HL, Thompson A, Martinot-Peignoux M, Piratvisuth T, Cornberg M, et al. (2011) Hepatitis B surface antigen quantification: why and how to use it in 2011 - a core group report. J Hepatol 55: 1121-1131.

20. Moucari R, Mackiewicz V, Lada O, Ripault MP, Castelnau C, et al. (2009) Early serum HBsAg drop: a strong predictor of sustained virological response to pegylated interferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative patients. Hepatology 49: 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464

1151-1157.

21. Brunetto MR, Moriconi F, Bonino F, Lau GK, Farci P, et al. (2009) Hepatitis B virus surface antigen levels: a guide to sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 49: 1141-1150. 22. Peng CY, Lai HC, Li YF, Su WP, Chuang PH, et al. (2012) Early serum HBsAg

level as a strong predictor of sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 35: 458-468. 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474

Figure legends:

Figure 1. Response rates in HBeAg-positive and -negative patients.

Figure 2. HBsAg kinetics during and after Peg-IFN therapy.

The median HBsAg level from baseline to 12 months post-treatment declined from 3.4 to 2.6 log10 IU/mL in all patients, from 3.8 to 2.7 log10 IU/mL in HBeAg-positive patients, and from 3.2 to 2.5 log10 IU/mL in HBeAg-negative patients.

Figure 3. HBsAgkineticsduring and after Peg-IFN therapy according to treatment response.

There was no difference in HBsAg decline between HBeAg-positive patients with and without HBeAg seroconversion. HBeAg-negative patients who achieved HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at 12 months post-treatment showed continued HBsAg decline after stopping Peg-IFN. In contrast, a rebound in HBsAg level after stopping Peg-IFN was found in HBeAg-negative patients who did not achieve HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL at 12 months treatment. (VR means HBV DNA <2000IU/mL 12 months post-treatment)

Figure 4. Cumulative rates of HBsAg seroclearance in HBeAg-negative patients.

475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494

For HBeAg-negative patients with long-term follow-up, the 5-year cumulative rate of HBsAg seroclearance was 9.8%.

Table 1. Demographic data and baseline characteristics of all treatment-experienced CHB patients Total (N = 57) HBeAg-positive (N = 24) HBeAg-negative (N = 33) 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512 513 514

Male gender 45 (78.9) 15 (62.5) 30 (90.9) Age, years 40.0 (31.5, 47.0) 34.0 (30.3, 40.5) 45.0 (38.5, 50.0) Prior therapy IFN NUC 17 (29.8) 40 (70.2) 8 (33.3) 16 (66.7) 9 (27.3) 24 (72.7) Liver cirrhosis 3 (5.3) 0 (0) 3 (9.1) Platelet, 103/uL 180 (150, 208) 197 (157, 248) 174 (145, 197) ALT, U/L 103.0 (71.5, 163.5) 112.0 (74.3, 171.3) 96.0 (66.0, 142.0) ALT 1-≤2x ULN 2 - 5x ULN > 5x ULN 17 (29.8) 35 (61.4) 5 (8.8) 7 (29.2) 14 (58.3) 3 (12.5) 10 (30.3) 21 (63.6) 2 (6.1) Albumin, g/dL 4.2 (4.1, 4.4) 4.1 (4.0, 4.3) 4.3 (4.2, 4.4) Total bilirubin, mg/dL 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) 0.9 (0.8, 1.2) 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) Creatinine, mg/dL 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) 0.9 (0.7, 0.9) 1.0 (0.8, 1.0)

Prothrombin time (INR) 1.04 (1.00, 1.12) 1.04 (1.00, 1.13) 1.04 (1.00, 1.10)

Genotype B C 34/55 (61.8) 21/55 (38.2) 12/22 (54.5) 10/22 (45.5) 22 (66.7) 11 (33.3)

HBV DNA, log10 IU/mL 6.6 (5.8, 7.8) 7.6 (7.1, 8.1) 6.1 (5.0, 6.8)

HBsAg, log10 IU/mL 3.4 (2.9, 3.9) 3.8 (3.6, 4.4) 3.2 (2.3, 3.6)

Continuous variables: median (25th, 75th percentiles); categorical variables:numbers(percentages) Missing data: genotype – 2

IFN: interferon; NUC: nucleos(t)ide analogue; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ULN: upper limit of normal; HBeAg: hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

Table 2. Factors associated with HBeAg seroconversion plus HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL 12 months post-treatment in treatment experienced HBeAg-positive CHB patients. 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525

HBeAg seroconversion plus HBV DNA < 2000 IU/ml

Yes (N = 3) No (N = 21) p

Female gender 3 (100) 6 (28.6) 0.042

Age, years 34.0 (31.0, 37.0) 34.0 (29.5, 41.0) 0.965

Prior IFN therapy 3 (100) 0 (0) 0.028

Platelet, 103/uL 201 (165, 275) 193 (153, 245) 0.680

Baseline ALT, U/L 196.0 (157.0, 484.0) 98.0 (72.5, 165.0) 0.040

≥ 2x ULN (vs< 2x ULN) 3 (100) 14 (66.7) 0.530

≥5 x ULN (vs< 5x ULN) 1 (33.3) 2 (9.5) 0.343

Albumin, g/dL 3.9 (3.9, 4.3) 4.1 (4.0, 4.4) 0.354

Total bilirubin, mg/dL 1.2 (0.9, 1.4) 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) 0.354

Creatinine, mg/dL 0.7 (0.4, 0.7) 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) 0.041

Prothrombin time (INR) 1.16 (1.13, 1.19) 1.01 (0.99, 1.10) 0.052

Genotype B 1 (33.3) 11/19 (57.9) 0.571

Baseline HBV DNA, log10 IU/mL 7.9 (7.3, 8.1) 7.6 (7.0, 8.2) 0.600

Undetectable DNA at week 12 2 (66.7) 1 (4.8) 0.032

Decline in HBV DNA >2 log at week 12 3 (100) 6 (28.6) 0.042

Baseline HBsAg, log10 IU/mL 4.3 (3.4, 4.3) 3.8 (3.6, 4.4) 0.920

HBsAg < 1500 IU/mL at week 12 1 (33.3) 4 (19.0) 0.521

HBsAg > 20000 IU/mL at week 24 0 (0) 5 (23.8) 1.000

48 weeks Peg-IFN therapy 1 (33.3) 6 (28.6) 1.000

Continuous variables: median (25th, 75th percentiles); categorical variables: numbers (percentages)

IFN: interferon; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ULN: upper limit of normal; HBeAg: hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

Table 3. Factors associated with HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL 12 months posttreatment in treatment experienced HBeAg-negative CHB patients.

HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL 526 527 528 529 530 531 532 533 534 535

Yes (N = 5) No (N = 28) p

Female gender 0 (0) 3 (10.7) 1.000

Age, years 40.0 (27.5, 48.0) 46.0 (39.0, 51.3) 0.200

Prior IFN therapy 1 (20) 8 (28.6) 1.000

Liver cirrhosis 1 (20) 2 (7.1) 0.400

Platelet, 103/uL 174 (144, 204) 174 (144, 196) 0.802

Baseline ALT, U/L 107.0 (78.0, 217.0) 93.5 (64.5, 140.3) 0.393

≥ 2x ULN (vs< 2x ULN) 4 (80) 19 (67.9) 1.000

≥5 x ULN (vs< 5x ULN) 1 (20) 1 (3.6) 0.284

Albumin, g/dL 4.3 (4.0, 4.5) 4.3 (4.2, 4.4) 0.899

Total bilirubin, mg/dL 1.3 (0.8, 1.4) 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) 0.436

Creatinine, mg/dL 0.9 (0.9, 1.0) 1.0 (0.8, 1.1) 0.821

Prothrombin time (INR) 1.02 (0.97, 1.16) 1.05 (1.00, 1.10) 0.920

Genotype B 4 (80) 18 (64.3) 0.643

Baseline HBV DNA, log10 IU/mL 5.7 (5.0, 6.9) 6.1 (5.0, 6.9) 0.763

Undetectable DNA at week 12 4 (80) 10 (35.7) 0.138

Decline in HBV DNA >2 log at week 12 4 (80) 18 (64.3) 0.643

Undetectable DNA at week 24 4 (80) 9 (32.1) 0.066

Baseline HBsAg, log10 IU/mL 2.6 (2.3, 4.1) 3.2 (2.1, 3.6) 0.814

No HBsAg decline or HBV DNA decline < 2 log at week 12

2 (40) 10 (35.7) 1.000

HBsAg < 150 IU/mL at week 12 2 (40) 6 (21.4) 0.574

Decline in HBsAg ≥ 10% at week 24 5 (100) 19 (67.9) 0.290

Continuous variables: median (25th, 75th percentiles); categorical variables: numbers (percentages)

IFN: interferon; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ULN: upper limit of normal; HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

536 537 538 539